Abstract

Sulfur is present in the amino acids cysteine and methionine and in a large range of essential coenzymes and cofactors and is therefore essential for all organisms. It is also a constituent of sulfate esters in proteins, carbohydrates, and numerous cellular metabolites. The sulfation and desulfation reactions modifying a variety of different substrates are commonly known as sulfation pathways. Although relatively little is known about the function of most sulfated metabolites, the synthesis of activated sulfate used in sulfation pathways is essential in both animal and plant kingdoms. In humans, mutations in the genes encoding the sulfation pathway enzymes underlie a number of developmental aberrations, and in flies and worms, their loss-of-function is fatal. In plants, a lower capacity for synthesizing activated sulfate for sulfation reactions results in dwarfism, and a complete loss of activated sulfate synthesis is also lethal. Here, we review the similarities and differences in sulfation pathways and associated processes in animals and plants, and we point out how they diverge from bacteria and yeast. We highlight the open questions concerning localization, regulation, and importance of sulfation pathways in both kingdoms and the ways in which findings from these “red” and “green” experimental systems may help reciprocally address questions specific to each of the systems.

Keywords: sulfotransferase, sulfur, Arabidopsis thaliana, steroid hormone, human, secondary metabolism, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) synthase, adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate kinase, ATP sulfurylase, glucosinolates, sulfate activation

Introduction

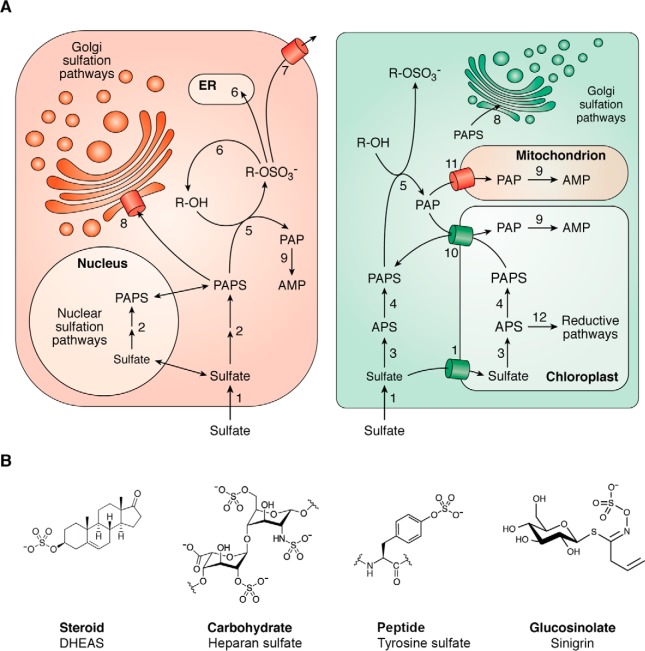

Sulfur (S) is an essential nutrient for all life forms. It is present in a plethora of metabolites of primary and secondary metabolism, most prominently in the amino acids cysteine and methionine, and cofactors such as iron–sulfur clusters, lipoic acid, and CoA. In the majority of these metabolites, sulfur is present in its reduced form of organic thiols; however, some compounds contain S in its oxidized form of sulfate (1, 2). Sulfate is transferred to suitable substrates onto hydroxyl or amino groups by sulfotransferases (3, 4). These biological sulfation reactions as well as desulfation catalyzed by sulfatases are often denoted as sulfation pathways (Fig. 1) (5, 6).

Figure 1.

Red and green sulfation pathways. A, sulfate is taken up by various sulfate transporters; in plants, some of them transport sulfate into the chloroplast (1). Sulfate activation occurs via animal bifunctional PAPS synthases (2) that shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus or plant ATP sulfurylase (3) and APS kinase (4) isoforms that are localized in cytoplasm and the chloroplast. PAPS serves as a substrate for cytoplasmic sulfation pathways (5), where PAP is produced. Sulfated compounds can then be de-sulfated by sulfatases (6), enzymes that are absent in plants, or they are secreted via OATPs (7). Two animal PAPS transporters (8) channel PAPS into the Golgi apparatus where many carbohydrate and protein sulfotransferases modify macromolecules for secretion. Although plant protein sulfotransferases are known that reside in the Golgi, an analogous transporter (8) has not yet been identified. Human PAP phosphatases (9) are in the Golgi and the cytoplasm; plant PAP phosphatases are, however, localized in the mitochondrion and the chloroplast. Dedicated PAP(S) transporter in the chloroplast (10) and the mitochondrion (11) deliver PAPS to the cytoplasm and play an important role in the degradation of PAP. In plants, APS represents a branching point where reductive biosynthetic pathways diverge (12). B, examples of structures of sulfated metabolites.

The activated sulfate for the sulfation pathways, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5-phosphosulfate (PAPS),3 is formed from sulfate by two ATP-dependent steps: adenylation, i.e. the transfer of the AMP moiety of ATP to sulfate to form adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS) by ATP sulfurylase (ATPS), and the phosphorylation of APS at its 3′-OH group by APS kinase. The two enzymes are either fused into a single enzyme PAPS synthase (PAPSS) in the animal kingdom or occur as independent proteins in the green lineage (7). The by-product of PAPS-dependent sulfation reactions, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5-phosphate (PAP), is finally dephosphorylated to AMP by 3′-nucleotidases. This reaction to remove PAP is important beyond the sulfation pathways, as PAP accumulation has many additional physiological effects (8, 9).

Sulfate activation to APS or PAPS is a prerequisite not only for sulfation pathways but also for primary sulfate assimilation in plants, algae, bacteria, and fungi (2). Particularly fungi and some bacteria require PAPS for sulfate reduction and synthesis of cysteine. In these organisms, the activated sulfate in PAPS is reduced to sulfite by PAPS reductase, and after further reduction to sulfide, it is incorporated into cysteine (10). The green lineage as well as a large number of bacterial taxa, however, use APS for sulfate reduction by APS reductase, whereas Metazoa do not possess the ability to reduce sulfate and are dependent on sulfur-containing amino acids in their diet (7). In sulfate-reducing organisms, sulfation pathways compete with the primary sulfate reduction for activated sulfate, and the two branches of sulfur metabolism must be well-coordinated (11). The ability to reduce sulfate is thus the major difference in sulfur metabolism between animals and plants and impacts on other metabolic branches, including sulfation pathways.

In plants, traditionally, studies of sulfur metabolism concentrated on reductive, primary sulfur metabolism. For the red kingdom, in his scholarly “Tribute to Sulfur,” Helmut Beinert (1) wrote that sulfate “is of limited use to higher organisms except for sulfation and detoxification reactions,” without any further discussion of the topic. Since then, things have dramatically changed with growing evidence of the importance of sulfation pathways in both kingdoms. In addition, convergent findings in the green (plant) and red (animal) biochemistry of sulfur, e.g. recognition of hydrogen sulfide as a gaseous signal (12, 13), revealed the value of comparative analysis of the same pathways in very different models. Here, we compare the mechanisms the two lineages, red and green, evolved to perform and control sulfation pathways. Given their importance for the metabolism of specific compounds and for the general sulfur metabolism, we extend the scope of our comparison to the enzymes providing the active sulfate and removing the by-product PAP. We aim to identify open questions common to both humans and plants as well as questions where knowledge from one lineage might be useful to inform research in the other.

Activation of sulfate to PAPS

The organification or activation of sulfate to PAPS by ATPS and APS kinase initiates sulfation pathways (14). The catalytic and substrate-binding sites of the ATP sulfurylases from plants and animals are highly conserved (15); however, subsequent reactions and the enzymatic blueprints vary greatly between different lineages (7). Also, the localization and regulation of ATP sulfurylase and APS kinase show lineage-specific differences.

Plant ATP sulfurylase and APS kinase

In plants, ATPS occurs as a homodimer, consisting of two 48-kDa monomers (16). Plants and algae have multiple ATPS isoforms localized in chloroplast and cytosol; the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana possesses four (17). In some plants, such as potato, distinct cytosolic and plastidic isoforms can be identified (18), whereas all four Arabidopsis isoforms possess N-terminal chloroplast-targeting peptides. Cytosolic activity is caused by alternative translation of the ATPS2 transcript, producing two different proteins: one with the target peptide transported into the chloroplast and one without the peptide located in the cytosol (19). The reason for the dual localization of the ATPS seems to be the need for both APS for sulfate reduction in plastids and PAPS for sulfotransferases in the cytosol (20). However, given the major role of plastids for synthesis of PAPS and the presence of PAPS transporters in plastid envelopes, the role of cytosolic ATPS is not obvious. Interestingly, both human PAPS synthases are also regulated on the level of cellular localization of the enzyme between the nucleus and cytosol, even though a function of PAPS in the nucleus is completely unknown (21).

Because of its position at the beginning of the pathway, ATPS is a good candidate for controlling sulfate assimilation. Indeed, early findings in Brassica napus showed that ATPS activity and transcript levels were down-regulated by downstream products of sulfate assimilation, cysteine and GSH, and were up-regulated by sulfate starvation (22). These findings played a key role in formulating the concept of demand-driven regulation of sulfur metabolism in plants (23, 24). However, the subsequent enzyme in the primary sulfate assimilation pathway in plants, the APS reductase, is regulated more strongly and was shown by metabolic flux control analysis to be the major control point of the pathway (25–27). Indeed, a recent modeling approach showed that the pattern of flux control is dynamic and not static (28); changes occur with differing environmental conditions, and control resides mostly at APS reductase or downstream sulfite reductase and not ATPS (28). ATPS, however, still contributes to the control of sulfate accumulation in Arabidopsis (29) and to the response to sulfate starvation as a target of microRNA miR395 (30). Arabidopsis ATPS1 and ATPS3 isoforms are part of the regulatory network of glucosinolate synthesis, and atps1 mutants show a lower concentration of these sulfated secondary compounds (29, 31). Glucosinolates are part of the plant immune response to pathogens and herbivores as well as plant natural products responsible for smell, taste, and health effects of cruciferous vegetables, but also anti-nutrients for animal feed (32).

Although essential and sufficient for sulfate reduction, ATPS has to be coupled with the APS kinase for sulfation pathways. This enzyme, ubiquitous in nature and highly conserved in structure and sequence, shows the same localization in plants as ATPS. Arabidopsis possesses four APS kinase genes, which encode three plastidic and one (APK3) cytosolic isoform (33). APS kinase phosphorylates APS produced by ATPS and thus competes with APS reductase for this substrate. The two enzymes represent entries into the two branches of sulfate assimilation: a primary reductive assimilation pathway and a secondary oxidized sulfur metabolism involving sulfation pathways (34). The secondary pathway has been rarely investigated, because PAPS production is not necessary for the primary sulfate reduction and synthesis of cysteine and GSH (34). However, even though APS kinase is part of the secondary sulfate assimilation pathway, it is vital for plant survival (33, 35). Interestingly, it is the loss of two plastidic APS kinase isoforms APK1 and APK2 that results in strongly reduced accumulation of sulfated metabolites, such as glucosinolates, and not the disruption of the cytosolic enzyme APK3 (33). This, on the one hand, again challenges the significance of cytosolic APS and PAPS synthesis; on the other hand, it shows the necessity of intracellular PAPS transport. Indeed, a PAPS transporter has been identified in chloroplast envelope membranes, part of the glucosinolate co-expression network, whose mutation shows a phenotype similar to apk1 apk2 mutants (see below and Ref. 36).

The apk1 apk2 double knockout turned out to be an excellent tool to dissect the importance of secondary sulfate assimilation (11, 33). The reduced synthesis of PAPS in apk1 apk2 results in a shift of sulfur flux from the secondary to the primary sulfur assimilation pathway, increased accumulation of reduced sulfur compounds, and highly-reduced glucosinolate levels (11, 33). Furthermore, all components of the glucosinolate synthesis pathway were coordinately up-regulated leading to substantial accumulation of the desulfo-precursors of glucosinolates (33). Although glucosinolates and other sulfated secondary metabolites seem not to be essential for Arabidopsis growth, the apk1 apk2 mutants are significantly smaller than the WT plants (33). When additional APS kinase genes, APK3 or APK4, are mutated, the semi-dwarf phenotype is even stronger (35). The generation of multiple mutations in APS kinase genes revealed that the enzyme is essential for Arabidopsis growth (35). Which acceptors of PAPS are essential remains to be determined, as neither the glucosinolates nor the sulfated peptide hormones (such as the phytosulfokines (37), root growth factors (38), or Casparian strip integrity factors (39)) discovered so far, seem to be crucial.

APS kinase is regulated on both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. The genes are part of the glucosinolate transcriptional network, under control by a family of six MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis and thus co-expressed with genes providing the main substrate for PAPS (31). In addition, according to the demand-driven concept, sulfate starvation represses APS kinase to channel the scarce sulfur to the primary sulfate assimilation. Excitingly, redox regulation of APS kinase enzyme activity through dimerization of the protein and formation of disulfide bridges has been revealed in a structural analysis (40). Reducing conditions leading to monomerization of the protein increase the catalytic efficiency, including alleviation of enzyme inhibition by its substrate APS (40). This is particularly interesting as it complements the redox regulation important for control of the reductive branch of sulfate assimilation (2). APS reductase is activated by oxidation, e.g. during abiotic stress, which leads to higher activity and synthesis of cysteine and GSH (41). Accordingly, recombinant APS reductase is inactivated by incubation with reductants (27). APS reductase and APS kinase occupy the opposite branches of sulfate assimilation from APS (11). Considering that APS reductase is activated by oxidation (41), the reciprocal activation of APS kinase by reduction indicates that this redox mechanism may control the distribution of sulfur fluxes between primary and secondary sulfur metabolism (15).

Bifunctional PAPS synthases in animals

In contrast to plants with separate proteins possessing ATPS and APS kinase activities, vertebrate and invertebrate genomes feature these activities in single polypeptides with a C-terminal ATPS domain and an N-terminal APS kinase domain (7, 42). These so-called PAPS synthases are strictly conserved within animal genomes with a single gene in invertebrates and a PAPSS1 and PAPSS2 gene pair in vertebrates (42). An additional PAPSS2 gene copy in teleost fish and mammalian-specific splice forms of PAPSS2 are minor extensions to this rule (42). It is interesting to ask why this second sulfate-activating complex has evolved and has been strictly maintained in animals. Possibly, this has been a requirement for the expansion of sulfation pathways in animals. Two PAPS synthase genes would allow us to selectively support different sulfation pathways, either via transcriptional co-regulation (43), transient protein interaction (44), or yet-to-be described regulatory mechanisms.

Such a subfunctionalization is also indicated by the fact that PAPS synthases 1 and 2 cannot complement each other. Genetic defects for PAPSS1 have never been reported so far. However, mutations in the gene coding for PAPSS2 are associated with bone and cartilage malformations as well as a steroid sulfation defect (45); this is discussed in detail below.

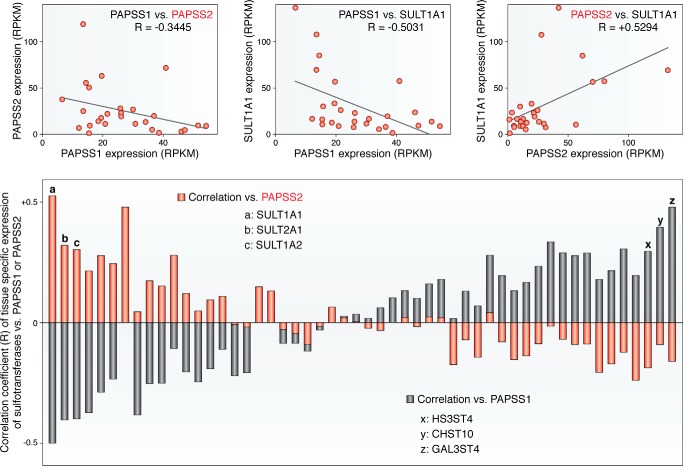

The mechanistic question is what makes the two PAPS synthase enzymes so different. Certainly, the two genes are differentially regulated to a certain extent, and transcriptional co-regulation with certain sulfotransferases has been reported (46, 47). However, correlations of transcript levels between PAPS synthases and sulfotransferases are only weak (Fig. 2), and both PAPS synthases are expressed at the same time in certain tissues (48). Different subcellular localization was believed to be of functional significance (49), but the conserved nuclear localization and export signals were identified both in PAPSS1 and PAPSS2 (21). Diverse catalytic activities were purported to explain the observed functional difference, based on only a 5-fold difference in kcat/Km values when treating bifunctional PAPS synthases as pseudo one-step Michaelis-Menten enzymes (50). This characteristic could not be reproduced when assaying APS kinase only, which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of overall PAPS biosynthesis (44, 51). A difference in protein stability of the two recombinant human PAPS synthases as described (42). PAPSS2 was less stable than PAPSS1 toward chemical or thermal unfolding (42). ATP sulfurylase and APS kinase activity assays, run after incubation at an elevated temperature, indicated that the sulfurylase domain is less stable than the APS kinase domain (42). This is probably due to ligand binding as the APS kinase may pull an ADP molecule from the bacterial host via several purification steps (6, 52). It will be interesting to see how these results translate into protein stability within the living cell (53). In light of these findings, the PAPSS gene fusion could also be thought of as a solubility anchor of a more stable domain for another less stable domain, among other factors.

Figure 2.

PAPS synthases and human sulfotransferases are weakly transcriptionally correlated. Expression profiles for PAPS synthases and sulfotransferases from 27 different human tissues were derived from Fagerberg et al. (48). PAPSS1 and PAPSS2 expression profiles were compared with each other and against different sulfotransferases. Top panel: PAPSS1 and PAPSS2 expression seem to be weakly anti-correlated. Comparing PAPSS1 or PAPSS2 with SULT1A1 shows a weak positive correlation between PAPSS2 and SULT1A1, but a negative correlation for PAPSS1 with SULT1A1. All units in these panels are in RPKM (reads per kb of transcript per million mapped reads). Bottom panel: to illustrate the positive or negative correlation of the tissue-specific expression, the correlation coefficient R is plotted for all 52 sulfotransferases versus PAPSS1 (black) or PAPSS2 (red). There is a tendency for PAPSS2 to be co-expressed with cytosolic sulfotransferases.

Benefit of being fused together

For bifunctional PAPS synthases, answering questions on whether and how the individual domains functionally interact with each other continue to drive our understanding in the field. Channeling of the APS intermediate between the two domains of human PAPS synthases was initially hypothesized but was subsequently ruled out based on kinetic (54, 55) and structural data (52). The crystal structure of full-length human PAPSS1 shows dimers of APS kinase and ATP sulfurylase each with large interacting surfaces but only a weak interaction between those sulfurylase and kinase domain dimers (52). The large dimer interface is conserved between PAPS synthase isoforms; hence, they can form high-affinity homo- and heterodimers (51). APS channeling was excluded as there was no channel visible in the structure (52); APS produced by the sulfurylase domain exchanges freely with bulk APS (54) and APS kinase and reverse sulfurylase assays can be run without problems starting from APS (44). Because no metabolic need for APS is known in animals, the PAPS synthases may represent a way for stoichiometric gene expression and protein localization of its two enzymatic components.

The formation of a bifunctional enzyme even without the added effect of substrate channeling can be an answer to the low-catalytic efficiency of the forward reaction of ATPS with a Keq of ∼10−8 (56). Therefore, the equilibrium can be shifted by the removal of the products, e.g. linking with inorganic pyrophosphatase to remove pyrophosphate or with enzymes utilizing APS. The animal PAPS synthase is clearly a mechanism for the latter, but not the only one in nature (7).

Another mechanism to increase the efficiency is employed by most bacteria, which possess a variant of ATPS that couples APS production with GTP hydrolysis (57), and the need for increased catalytic efficiency may have led to other gene fusions. In filamentous fungi, ATPS is also fused with APS kinase; however, the kinase domain of the fusion protein is at the C-terminal end and functions only as an activation domain to modulate activity of ATPS without having a kinase activity (58, 59). A number of gene fusions have been found in the eukaryotic microalgae, which as secondary or tertiary endosymbionts were likely more prone to genome rearrangements (7). ATPS in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana and other Protozoans is fused to both APS kinase and inorganic pyrophosphatase, whereas in the dinoflagellate Heterocapsa triquetra ATPS is fused with the other APS-utilizing enzyme, APS reductase (7). In addition to this diversity, at least three different ATP sulfurylase enzymes have evolved independently, the plant and animal enzyme, the bacterial GTPase-linked enzyme, and one mainly found in cyanobacteria and green algae (7, 60). The ATPS domains from the fusion proteins are phylogenetically related to the ATPS from plants/animals or green algae (7).

In plants, the need for APS for primary assimilation is greater that for the sulfation pathways, and therefore, a mechanism shifting the equilibrium from APS to PAPS is not advantageous. Another interesting evolutionary aspect of plant ATPS is that although it is largely a plastidic enzyme, it is in no way related to the ATPS in cyanobacteria, the precursors of plant plastids (7). Because chlorophyte ATPS is of cyanobacterial origin, it seems that the common precursor must have contained both forms, plastidic and Eukaryotic, and the sister lineages, plants and green algae, each retained a different one.

Core sulfation pathways

Sulfotransferases are the first enzymes of the core sulfation pathways. They transfer sulfate from PAPS to the hydroxyl or amino group of a wide variety of acceptors: carbohydrates, lipids, peptides, hormone precursors, xenobiotics, and other molecules (3, 61). There are also PAPS-independent aryl sulfotransferases from some bacteria, which use phenolic sulfates as donors (62). These aryl sulfotransferases display a different fold, but retain a similar spatial arrangement of the active-site residues, indicative of convergent evolution. They are covered in more detail elsewhere (62). The other components, sulfatases, are hydrolytic enzymes, part of the alkaline phosphatase superfamily, that cleave biological sulfate esters (63). A post-translational modification dramatically enhances the catalytic activity of sulfatase enzymes—a cysteine or serine residue within the catalytic center is converted to a formyl-glycine (64).

Lipmann (14) referred to sulfotransferases as sulfokinases, and a common evolutionary origin of sulfotransferases and kinases has been purported, with subsequent phylogenetic divergence of enzyme activity (65). There are four conserved regions of sulfotransferases used for the characterization of the enzymes (66), including a P-loop for catalysis (67, 68). This protein structure is highly conserved, except for plant tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase (69). Based on the conserved regions, sulfotransferases are found in all kingdoms of life (68). Different research communities abbreviate mammalian cytosolic sulfotransferases to SULT, plant enzymes to SOT (or SULT), and Golgi enzymes according to their main activity/substrate (e.g. HS6ST for heparan sulfate-6-O-sulfotransferase, and TPST for tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase). For consistency, we will keep the different abbreviations.

The main differences between animal and plant sulfation pathways are the number of genes with more than 50 genes for human SULTs and 21 SOT genes in Arabidopsis, whereas the 17 human sulfatases do not have counterparts in plant genomes.

Arabidopsis and the human sulfotransferase repertoire

Sulfotransferases are grouped into categories, such as soluble or membrane-bound, cytosolic or Golgi-located, substrate preference for low-molecular-weight substrates, or the larger carbohydrates, proteins, or proteoglycans (3).

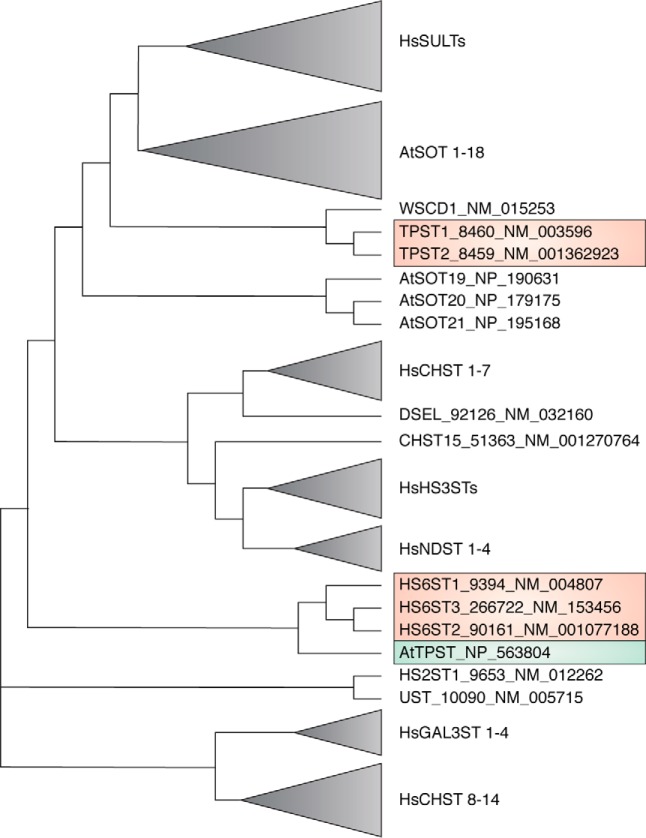

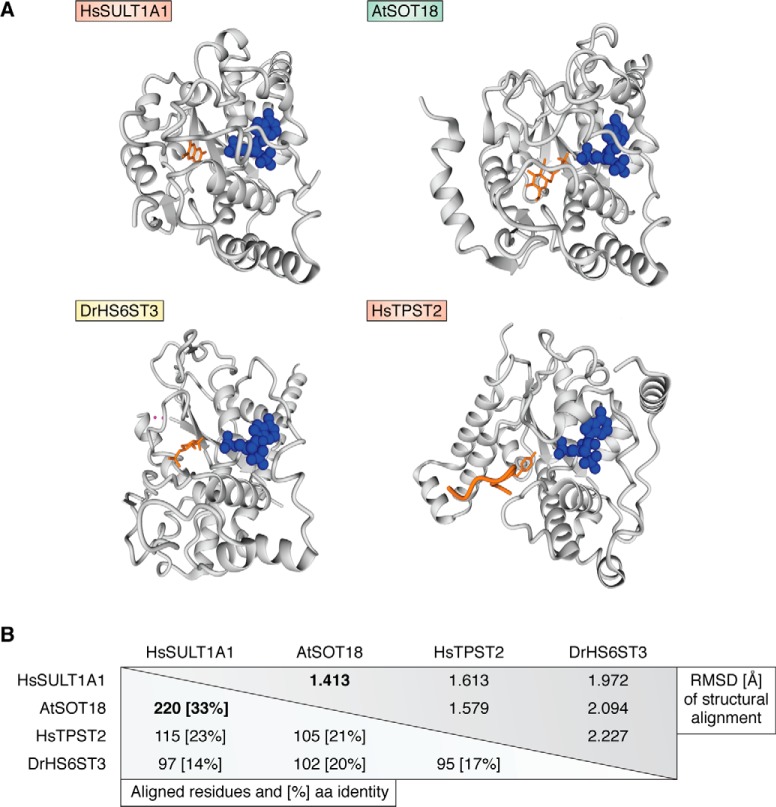

Langford et al. (70) listed 13 cytoplasmic and 37 Golgi-residing SULTs in the human genome. Ensembl lists several additional entries for the human genome (71), but most of them seem to be pseudogenes (5). The only proteins annotated having sulfotransferase activity at Ensembl that should append Langford's list are DSEL, a dermatan sulfate epimerase, and the WSCD1 protein (71). Hirschmann et al. (4) list 22 genes for sulfotransferases in Arabidopsis (but one of them is annotated as a pseudogene). Phylogenetic analysis of protein sequences from the final 21 and 52 genes representing the Arabidopsis and human sulfotransferase repertoires, respectively, reveals that Arabidopsis SOTs 1–18 share high-sequence similarity with human cytoplasmic SULTs. In fact, these two groups share a higher degree of similarity with each other than human Golgi and cytoplasmic SULTs (Fig. 3). This is illustrated by a structural overlay of AtSOT18 and human SULT1A1 (Fig. 4). Hence, any new insight on one class of these sulfotransferases may have direct applicability to the other (43).

Figure 3.

Alignment of sulfotransferases. Protein sequences from 52 human and 21 Arabidopsis sulfotransferases were derived from RefSeq entries from the nucleotide database at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. From multiple splice forms, the one selected was assigned the major isoform. These sequences were subjected to multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega and MAFFT (206). From the MAFFT tree, a neighbor-joining tree without distance corrections, a collapsed tree was manually curated. A striking finding was that AtTPST (RefSeq NP_563804) was not grouped with the human TPSTs but with heparan-6-O-sulfotransferases 1–3 (NCBI RefSeq NM_004807, NM_001077188, and NM_153456). The abbreviations used are as follows: SULT, cytosolic sulfotransferase; SOT, plant sulfotransferase; TPST, tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase; CHST, chondroitin sulfotransferase; HS(2/3/6)ST, heparan-(2/3/6)-O-sulfotransferase; NDST, N-deacetylase and N-sulfotransferase; Gal3ST, galactose-3-O-sulfotransferase.

Figure 4.

Structural representation of different sulfotransferases. A, all structures are shown in the same orientation with the bound PAP nucleotide shown in blue and a substrate in orange. Please note the central β-sheet in all structures and the PAP co-factor are bound exactly at the same position. Structures shown are human sulfotransferase SULT1A1 bound to PAP and 3-cyano-7-hydroxycoumarin (Protein Data Bank code 3U3M), A. thaliana SOT18 complexed to PAP and sinigrin (Protein Data Bank code 5MEX), Danio rerio heparan sulfate 6-O sulfotransferase HS6ST3 with PAP and part of its heptasaccharide displayed (Protein Data Bank code 5T0A), as well as human TPST2 with bound PAP and C4 peptide (Protein Data Bank code 3AP1). Structural visualizations were done using YASARA (207). B, these complexes were structurally aligned using MUSTANG (208). Root mean square deviation (RMSD) values for structural alignment, the number of aligned residues, and the percentage of amino acid identity are listed.

These insights mainly include discoveries of novel mechanisms of regulation (43). For example, the flexibility of the main substrate-binding loops—elucidated in part with new analytical and computational tools—is the molecular basis for the broad specificity of the sulfotransferase SULT1A1 (72), with possible implication also for AtSOT12 described below. This flexibility makes it difficult to search for pharmacologically useful and isoform-specific inhibitors of sulfotransferases using computational docking (73), except the flexibility is built into the structural models (74). Such inhibitors are useful because human sulfotransferases metabolize many drugs and may thus interfere with various pharmacological interventions. Another regulatory mechanism, allosteric regulation, has only recently been described in sulfation pathways (43). Recently, an allosteric site in human SULT1A3 was discovered that may be targeted for isoform-specific SULT1A3 allosteric inhibitors (75)

Dimers of human cytoplasmic SULTs are believed to form via an unusually small dimer interface containing the amino acids KTVE (76) that are conserved in cytoplasmic SULTs (77). Biochemical data and molecular dynamics simulation suggest that dimer formation is of functional significance as it modulates flexibility of the catalytic loop 3 (78). Recently, a crystal structure of the AtSOT18–sinigrin–PAP complex elucidated the functional domain and residues for the substrate-binding site of the enzyme (68). The structure demonstrated evolutionary conservation of the sulfotransferases between humans and plants (Fig. 4) and suggested a loop-gating mechanism as responsible for substrate specificity for the sulfotransferase in plants (68). Noteworthy, AtSOT18 and the other AtSOTs do not contain the KTVE motif, and dimer formation has not been reported for plant sulfotransferases.

Plant SOTs are still not completely characterized even in the model plant Arabidopsis (4). Some Arabidopsis SOTs have a broad substrate specificity, and some are very specific, such as AtSOT15 catalyzing only sulfation of 11- and 12-hydroxyl-jasmonate (79); however, the substrates for almost half of all SOTs are unknown (4). Most attention has been paid to three Arabidopsis SOTs, AtSOT16, AtSOT17, and AtSOT18, which transfer sulfate to desulfo-glucosinolate precursors as the final step in glucosinolate synthesis (80). This is due to the important role of glucosinolates in defense against biotic and abiotic stress and their anti-carcinogenic and neuroprotective properties in the human diet (32, 81). The three desulfo-glucosinolate SOTs have different affinities to various classes of the precursors, i.e. aliphatic and indolic, at least in vitro (82). Interestingly, it seems that SOTs from different natural Arabidopsis accessions possess different specificity to these precursors (83); however, whether these in vitro data are relevant in vivo needs to be confirmed.

Similar to the desulfo-glucosinolate SOTs, only in vitro substrate specificities are known for other SOTs. While AtSOT5, AtSOT8, and AtSOT13 transfer sulfate to flavonoids, AtSOT10 modifies the plant hormones, brassinosteroids (84, 85). In contrast to these SOTs with relatively narrow specificity, the AtSOT12 accepts a variety of substrates for the synthesis of sulfated flavonoids, salicylic acid and brassinosteroids (86). The activity with salicylic acid, a phytohormone involved in defense against pathogens, seems to be responsible for the increased pathogen susceptibility of sot12 mutants (86). The functions of other SOTs remain to be elucidated, particularly given the large variety of so far unknown sulfur-containing metabolites in Arabidopsis (87).

Protein sulfation by TPSTs

Tyrosine sulfation is a major post-translational regulation of secreted proteins and peptides in both animals and plants. However, this modification seems to be confined to multicellular Eukaryotes, as TPSTs have not been found in either bacteria or yeast (88). TPST catalyzes the transfer of sulfate from PAPS to the phenolic group of the amino acid tyrosine in the Golgi (69, 89, 90). It is estimated that one-third of all secreted human proteins are tyrosine-sulfated (91). Human TPST1 and TPST2 are type II transmembrane proteins with a C-terminal globular domain within the Golgi lumen (90). They share 67% amino acid identity with each other. As Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila only contain one TPST gene, a gene duplication may have occurred at the invertebrate–vertebrate transition.

Elucidating the biological roles of individual TPST isoforms through biochemical and structural studies of recombinant TPST proteins was a challenge for a long time. In 2013, Teramoto et al. (92) reported the crystal structure of human TPST2, followed by the structure of human TPST1 in 2017 (93). These structures are remarkable for two reasons. First, the core protein fold and the 5′-phosphosulfate–binding (5′-PSB) and the 3′-phosphate–binding (3′-PB) motifs involved in PAPS co-factor binding are structurally conserved even in these sulfotransferases only distantly related to their cytoplasmic counterparts (92, 93). Second, they explain the mechanism of substrate recognition. Protein substrates need to locally unfold to bind to TPSTs in a deep active-site cleft, a process similar to the one known for tyrosine kinases (92). Both human TPST enzymes target peptidic motifs with negatively charged residues around the acceptor tyrosine (89) with very similar or identical recognition mechanisms (93). This leaves open how the observed functional differences of the TPST isoforms (see below and Ref. 94) are caused on the protein level.

Indeed, despite structural and mechanistic similarities, the two TPST isoforms display notable functional differences. TPST1-knockout mice show reduced body weight and fewer litters due to increased fetal death in uterus, whereas male fertility is not affected (95). This suggests that TPST1 reaction products which would not be sulfated in the TPST1 knockout, have a role in females during development of embryos. TPST2-knockout mice, however, primarily show male infertility (96), due to compromised egg–sperm interaction (97). Taken together with the sulfated proteins from the blood-clotting cascade and the sulfated co-receptors on the host cells for HIV infections (89), the picture emerges that tyrosine sulfation acts as macromolecular glue to strengthen interactions of proteins with other proteins or other biopolymers. A recent biophysical study clearly illustrates this point. In the complex of an N-terminal sulfated part of the chemokine receptor CCR5 and its CCL5 ligand NMR revealed that high-affinity binding is attributed to sulfate-mediated twisting of the two N termini (98). Identifying more and more sulfated proteins is expected in the near future due to advances in MS that allow better recovery of sulfated peptides and unambiguous distinction from their isobaric phosphorylated counterparts (99).

The importance of tyrosine sulfation in plants has been known for a long time because of the number of sulfated growth-regulating peptides (37, 100). Despite the importance of the tyrosine sulfation, however, the corresponding sulfotransferase remained elusive in plants, as no homologous proteins to the animal enzyme could be found. AtTPST was identified in Arabidopsis after isolation of the enzyme from the microsomal fraction and proteomics analyses (69). AtTPST is a 62-kDa transmembrane protein located in the Golgi that lacks the characteristic cytosolic sulfotransferase domain (69). The importance of plant tyrosine sulfation is confirmed by the semi-dwarf phenotype of the Arabidopsis tpst1 mutant with early senescence, light green leaves, and diminutive roots (69).

Human sulfatase enzymes

The human genome contains 17 genes for sulfatases (70, 71), which hydrolyze a range of biological sulfate esters. They are all grouped into the alkaline phosphatase superfamily (63).

The activity of human (and bacterial or fungal) sulfatases depends on enzymatic oxidation of a cysteine to formylglycine (5). The corresponding enzyme is encoded by the sulfatase-modifying factor 1 (SUMF1) gene. This formylglycine is further hydrated to form the active site of sulfatase (101). The resulting geminal diol can be interpreted as activated water for the hydrolysis reaction (101). A recent crystal structure of the formylglycine-generating enzyme clearly shows its catalytic copper co-factor coordinated by two active-site cysteine residues, explaining its mechanism (102). As this oxidase creates an aldehyde, it has emerged as an enabling biotechnology tool for bio-conjugation reactions (103). There is also a SUMF2 gene in the human genome that encodes a protein devoid of the oxidase activity, but interacting and modulating the function of SUMF1 by forming inhibitory heterodimers (104).

Sulfatase genes encode proteins with a broad range of substrate specificity. The extracellular endoglucosamine 6-sulfatases, SULF-1 and SULF-2, target highly sulfated extracellular heparan sulfate domains, which are involved in growth factor signaling, tumor progression, and protein aggregation diseases (105). Some sulfatases (such as arylsulfatase A and B) are cytoplasmic, whereas others are membrane-bound (5). Noteworthy is the steroid sulfatase (STS), with a very rare and unusual membrane topology; its membrane stem is made up of two α-helices (106). STS has been described as an enzyme in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (101), but it was also detected in the Golgi apparatus (107).

From an endocrine point of view, STS is highly interesting as it renders steroid sulfation a reversible and dynamic process (5). STS is highly expressed in the placenta and forms, together with the fetal adrenal and fetal liver, the fetoplacental unit (108). This unit produces the placental estrogens, estradiol and estriol, from fetal adrenal androgens via fetal adrenal sulfation, fetal hepatic hydroxylation, and placental desulfation, further downstream conversion, and release into the maternal circulation (109). In adults, STS is also expressed in many other tissues allowing for the uptake of sulfated steroid precursors and their desulfation.

Plants do not seem to possess sulfatase activity. This poses an obvious question for the catabolism of sulfated secondary metabolites. Glucosinolates are an important pool of sulfur, which can be recycled during sulfur starvation. Glucosinolate degradation is part of their anti-herbivore activity, which is initiated by tissue damage, bringing the glucosinolates into contact with thioglucosidases (myrosinases). Removal of the sugar moiety leads to chemical rearrangement of the aglycones to form volatile isothiocyanates or nitriles and release of sulfate (110). Glucosinolates can, however, be degraded also without tissue damage by atypical PEN2 myrosinase as a part of innate immunity (111). Nothing is known about the catabolism of other sulfated compounds in plants.

Plants can also profit from microbial sulfatase activity in the rhizosphere. Soil contains a great portion of organic sulfur, up to 90%, which is not available to plants (112). Soil bacteria, however, can metabolize these compounds by sulfatases, releasing the sulfate, and thus improving plant sulfur nutrition. Hence, releasing sulfate via sulfatase activity is the mechanism of some plant growth-promoting bacteria (112). Attempts to engineer intracellular or excreted sulfatase in plants, to make the organic sulfate available to plants, failed so far, most likely because of the need for the post-translational activation by production of formylglycine.

PAP metabolism

The nucleotide PAP is produced during PAPS-dependent sulfation pathways. It is also formed during CoA-dependent fatty acid synthetase activation (113), although how or whether these two pathways interconnect is currently unclear. As a reaction product, PAP strongly inhibits sulfotransferase activity (114). With its two phosphate moieties, PAP may be regarded as the shortest possible RNA strand, and consequently, PAP interferes with RNA metabolism, inhibiting the XRN RNA-degrading exoribonucleases (115). To prevent the toxic effects of PAP, dedicated PAP phosphatases are found in all kingdoms of life. Most of the enzymes from higher Eukaryotes show multiple specificity toward PAP or PAPS, and they also impact inositol signaling by removing phosphate from inositol bis- and triphosphates (116, 117), all representing small and negatively charged substrates.

Lithium is known to influence many different proteins, and PAP phosphatases belong to the most sensitive targets for lithium inhibition. Mechanistically, lithium inhibition is well-understood for the PAP phosphatase CysQ from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lithium replaces one of a cluster of magnesium ions bound in the active site of the enzyme (118), due to the diagonal relationship between magnesium and lithium; these elements, diagonally adjacent in 2nd and 3rd periods of the periodic table, display a number of similar properties. As the negative amino acids in the catalytic center are highly conserved, it is highly likely that the same mechanism is in place in other PAP phosphatases.

In many microorganisms PAP phosphatases are strongly associated with sulfate assimilation, because accumulation of PAP also inhibits PAPS reductase, an essential enzyme in sulfate reduction. In yeast, loss of PAP phosphatase Met-22 leads to methionine auxotrophy (119). Defects in PAP catabolism result in severe growth inhibition; in animals they are mainly due to inhibition of sulfation-dependent processes (120, 121), and in plants the defects are much more complex, because of the involvement of PAP in additional signaling pathways (122, 123).

Plant PAP phosphatases and PAP-dependent stress signaling

Plant PAP phosphatase SAL1 belongs to the most pleiotropic plant genes. It was first identified in rice as a protein complementing an inability to grow on sulfate in cysQ mutants of E. coli and met22 yeast mutants (124). It was subsequently shown to catalyze conversion of PAPS to APS and PAP to AMP, and this function was speculated to regulate sulfur fluxes (125). A homologue from Arabidopsis was identified in a screen for genes improving salt sensitivity and was named SAL1 (116). Since then, SAL1 has been found in numerous genetic screens for a number of unrelated phenotypes and is therefore described under many different names. A common denomination, FIERY1 or FRY1, comes from a screen for mutants in abscisic acid and stress signaling, where its loss-of-function resulted in hyperinduction of the luciferase reporter gene driven by stress-responsible promoter (126). The phenotypes observed in the various alleles of sal1 mutants include cold and drought tolerance and signaling (122, 127), leaf shape and venation pattern (123), RNA silencing (115), increased jasmonate levels (128), glucosinolate and sulfur accumulation (9), lateral root formation (129), increasing circadian period (130), and many others. Initially it was believed that these phenotypes are caused by defects in inositol phosphate signaling (126), but current evidence points to PAP being the main factor (8, 9, 131, 132), thus linking sulfation pathways with a number of cellular processes.

In contrast to animal PAP phosphatases in the Golgi and the cytoplasm, the plant SAL1 enzyme in chloroplasts and mitochondria has a different localization than the sulfotransferases forming PAP (122). The number of phenotypes described in sal1 mutants resemble those of loss-of-function mutants in XRN exoribonucleases (133) and can be complemented by expression of SAL1 in the nucleus, implying that one mode of action of PAP is inhibition of XRNs (122). A model in which PAP acts as retrograde signal from chloroplast to nucleus during abiotic stress has been proposed (122) and corroborated by recent findings of redox regulation of SAL1 (134). Thus, oxidative stress leads to oxidation of a redox cysteine pair in SAL1 and strong inactivation of the enzyme. This in turn results in accumulation of PAP, its transport to the nucleus, and induction of expression of stress-response genes (134). Accordingly, PAP accumulation due to loss-of-function of SAL1 leads to stress tolerance, such as drought tolerance (8). In addition, the SAL1–PAP regulatory module has an intermediary role connecting hormonal signaling pathways, such as germination and stomatal closure (135).

It has to be noted that in Arabidopsis SAL1 is a member of a small gene family with seven members. SAL1 is, however, the only gene that has been found in the numerous genetic screens and that, when disrupted, causes the various phenotypes. Two additional isoforms, AHL and SAL2, were confirmed to function as PAP phosphatase (136), but only AHL is expressed at levels comparable with SAL1 (131). In contrast to SAL1, AHL does not seem to use inositol 1,4-bisphosphate as a substrate (136), and its overexpression complements the loss of SAL1 for at least some phenotypes (131). Although this is clear evidence for PAP being the causal metabolite for many phenotypes, the reason why in WT Arabidopsis AHL does not suffice to metabolize PAP remains to be elucidated. Another unsolved question is the physiological relevance of PAPS dephosphorylation.

The alteration in glucosinolate synthesis is the first direct metabolic link of SAL1 with sulfation pathways (9). In the fou8 allele of sal1 mutants, glucosinolate levels were lower than in WT Col-0 (9). This was caused by reduction in sulfation rate, as the mutants also accumulated the desulfo-glucosinolate precursors (9). The phenotype thus strongly resembled that of apk1 apk2 mutants with low provision of PAPS (33). Interestingly, combining the fou8 mutant with apk1 apk2 resulted in alleviation of many of the phenotypic alterations connected with loss of SAL1 function, strongly suggesting that PAP was the responsible metabolite (9). This observation forms a second direct link of SAL1 and sulfation pathways: the SAL1–PAP signaling depends on synthesis of PAPS and sulfation reactions, i.e. secondary sulfur metabolism (132). This is particularly important for plants, which do not synthesize glucosinolates or other major classes of sulfated secondary metabolites but still possess functional PAP signaling (137). Which sulfotransferase isoforms provide the majority of PAP for the stress signaling is, however, still unknown.

Human BPNT1 and Golgi PAP phosphatases

In humans, PAP is degraded at the sites of its production by a cytoplasmic and a Golgi PAP phosphatase. The human PAP phosphatase bisphosphate nucleotidase 1 (BPNT1) is a cytoplasmic enzyme (138), whereas the “Golgi PAP phosphatase” (gPAPP) is obviously located in the Golgi apparatus. For its side activity toward inositols, however, gPAPP is also known as inositol monophosphatase domain containing 1 (IMPAD1). The catalytic domain of this type II transmembrane protein is in the lumen of the Golgi (138). Its main substrate is PAP from Golgi-residing sulfotransferases (121).

Mice with an inactivated gPAPP/IMPAD1 gene show neonatal lethality, abnormalities in the lung, and bone and cartilage malformation (121). This may be due to under-sulfated chondroitin and perturbed formation of heparan sulfate due to the inhibition of the corresponding sulfotransferases by the accumulated PAP (121). The human gPAPP/IMPAD1 gene lies in the genomic region 8p11-p12 that is frequently amplified in breast cancer (139); however, a functional role in tumorigenesis remains to be established. Patients with truncation mutations in gPAPP/IMPAD1 are characterized by short stature, joint dislocations, brachydactyly, and cleft palate (120, 140). Some patients also had a homozygous missense mutation D77N (140). This mutation was recently introduced into mice, and the phenotype of homozygous gPAPP/Impad1 knockin animals overlaps with the lethal phenotype described previously in Impad1 knockout mice (141). The gPAPP phosphatase is only found in animals; hence, it may have co-evolved with the many Golgi sulfotransferases as a critical modulator of glycosaminoglycan and proteoglycan sulfation.

With an inhibition constant Ki of 157 μm, the only other human PAP phosphatase BPNT1 is an exceptionally lithium-sensitive enzyme (142). Hence, there was speculation whether BPNT1 is the actual target for lithium as a treatment for bipolar disorder. At least in C. elegans, lithium causes BPNT1-mediated selective toxicity to specific neurons and leads to behavior changes (143). A study in rats, however, questioned the role of PAP phosphatases for the therapeutic effect of lithium, as there was no PAP accumulation detected in the brain after prolonged lithium exposure (144). Additionally, the knockout of Bpnt1 in mice leads to an early aging phenotype (145). Bpnt1−/− mice do not show a skeletal phenotype, but develop liver pathologies, hypoalbuminemia, hepatocellular damage, and deadly whole-body edema by just 7 weeks of age (145). PAP accumulation is thought to interfere with RNA processing leading to defective ribosomes (145). A recent re-evaluation of the same mouse model linked the toxic accumulation of a BPNT1 substrate, such as PAP, directly or indirectly to changes in HIF-2α levels and iron homeostasis (146). Looking at the tissue distribution of the BPNT1 and enriched levels of PAP, Hudson and York (147) reported a mismatch between broad expression of BPNT1, but measurable PAP accumulation only in liver, duodenum, and kidneys.

Interesting questions about how BPNT1 is regulated in a tissue-specific manner, whether redox regulation plays a role, and what involvement this PAP phosphatase has in further regulatory pathways remain to be answered. In worms at least, a genetic interaction of BPNT1 and the exoribonuclease XRN2 in polycistronic gene regulation has recently been reported (148).

Subcellular localization and transporters in sulfation pathways

The products of sulfation pathways represent intracellular metabolites as well as external proteins/peptides and carbohydrates. Therefore, the sulfotransferase enzymes have to be located in at least two compartments of the cytosol and Golgi apparatus. However, animal sulfate activation occurs in the cytoplasm and the nucleus as PAPS synthases shuttle between these compartments (21). Conserved nuclear localization and export signals govern this subcellular distribution, including a nuclear localization signal at the very N terminus of the APK domain as well as an atypical nuclear export signal at the APK dimer interface (21).

Human soluble SULT enzymes are mainly cytoplasmic (3); however, they are sometimes also present in the nucleus (149). They receive the necessary PAPS co-factor from PAPS synthases via diffusion through the bulk medium; however, transient protein interactions might facilitate this process (44). Because of their very high expression in liver and some other tissues, cytoplasmic sulfotransferases may outnumber PAPS synthases and the co-factor itself (44, 150). Therefore, interactions between sulfotransferases and PAPS synthases may be a mechanism to overcome the substrate limitation and add an additional level of control (44).

The many Golgi sulfotransferases rely on the import of PAPS by the human PAPS transporters PAPST1 and PAPST2, also referred to as SLC35B2 and SLC35B3, respectively (151, 152). Both transporters belong to the group of nucleotide–sugar transporters but are specific for PAPS and only share 24% amino acid identity with each other (152). The PAPST1 homologue from Drosophila is essential for viability of the flies (152). In humans, the two transporters are expressed in different tissues and may impact different subsets of sulfation pathways (153).

A complementary mechanism to having enzymes in multiple compartments is that the substrates and/or sulfated products themselves can traffic around the cell. Many low-molecular-weight compounds such as steroids are believed to be membrane-permeable. Notably, however, a recent study challenges the dogma of freely membrane-permeable steroids (and maybe also other smaller compounds). Okamoto et al. (154) have reported that in Drosophila, steroid hormones require a protein transporter for passing through cellular membranes. Moreover, once steroids become sulfated, they are trapped within the cell (5). Release into the circulation and uptake into other cells depends on organic anion transporters, the OATPs (155). These individual transporters thus represent an additional layer of regulation (156).

Plants also require transporters for function of sulfation pathways. Although all the PAPS-dependent sulfotransferases are located outside of plastids, the majority of the APS kinase activity is located within the chloroplast (33). Hence, plant cytosolic sulfation pathways are dependent on export of PAPS from plastids and those in the Golgi additionally on import of cytosolic PAPS. The first plant PAPS transporter was identified through co-expression with genes for glucosinolate synthesis and transport assays in liposomes (36) and belongs to the ADP/ATP carriers of the mitochondrial carrier family. AtPAPST1 also transports PAP, which has to be imported to plastids for degradation by SAL1; therefore, the transporter most probably serves as a PAP/PAPS antiporter (36). The loss-of-function mutant papst1 accumulates desulfo-glucosinolate precursors and shows decreased glucosinolate levels similar to but to a lower extent than apk1 apk2, suggesting the existence of a second plastidic PAPS transporter. Indeed, AtPAPST2 was recently identified in Arabidopsis as a transporter located dually in membranes of chloroplasts and mitochondria (157). The AtPAPST2 gene is not co-expressed with glucosinolate genes, and its loss had only a minor effect on glucosinolate accumulation (157). Localization links AtPAPST2 to SAL1, which is also present in plastids and mitochondria. Thus, it seems that AtPAPST1 has a major role in exporting PAPS from chloroplast to cytosol for sulfation reactions and AtPAPST2 in importing PAP into the organelles for degradation by SAL1 (157). It also seems that the two transporters, AtPAPST1 and AtPAPST2, are not sufficient to explain all phenotypes connected to movement of PAPS and PAP between cytosol and the organelles, particularly the accumulation of glucosinolates and their desulfo-precursors. This metabolic phenotype can be expected to be found in mutants of the additional transporter gene(s) and enable their identification.

Natural genetic variation

The enzymes connected to sulfation pathways show a large variation between the different lineages and taxa. Many of them are found in several isoforms, further expanding their variation. However, the individual gene/enzyme isoforms also show variability within a single species, in different accessions and populations or even in individuals. Rare genetic mutations have been extremely informative in the study of many components of the sulfation pathways (16, 45, 158). Because of vastly increased sequencing capacities, such genetic variation is now studied on a population scale, both in plants and in humans.

Human genetic variation and clinical outcomes

Genetic defects in the gene for human PAPSS1 have not been reported so far. Gene defects in human PAPSS2, however, have been known to cause various forms of bone and cartilage malformation, due to an under-sulfation of the extracellular matrix (45, 158). A steroid sulfation defect was reported for the first time in a girl with the compound–heterozygous mutations T48R/R329* in PAPSS2 (159). A subsequent study with two brothers carrying the compound–heterozygous mutations G270D and the frameshift mutation W462Cfs*3, resulting in an early termination codon, in PAPSS2 confirmed disrupted sulfation of DHEA, the most abundant steroid in the human circulation (5), and increased androgen activation (45). These studies of individual patients (45, 159) established PAPSS2 as the main sulfate-activating complex to support abundant DHEA sulfation by the sulfotransferase SULT2A1. Why the other PAPS synthase PAPSS1 was not able to compensate PAPSS2 loss was a longstanding question in the field. A recently reported specific protein interaction between PAPSS2 and SULT2A1 may be an explanation for this directionality in steroid sulfation pathways (44).

Oostdijk et al. (45) list 43 individuals with different kinds of PAPSS2 mutations. Importantly, a clinical phenotype of the heterozygous carriers of major loss-of-function PAPSS2 alleles are known. The two mothers with WT/R329X and WT/W462Cfs*3 reported clinical features consistent with a phenotype of polycystic ovary syndrome, specifically chronic anovulation requiring ovulation induction (159). These alleles are far more common in the general population than the compound–heterozygous cases and may contribute significantly to the patient cohort with reduced sulfation capacity and associated health risks (160). Mutations in sulfotransferase genes additionally underlie a number of clinical conditions. Discussing genetic findings for all 52 human sulfotransferase genes is out of the scope of this review, but a few examples illustrate our understanding thus far. In one case, mutations in a Golgi-localized carbohydrate sulfotransferase 11 (CHST11) were shown to result in reduction in chondroitin sulfation and thus defects in cartilage formation and limb malformations (161). Mutations in the X-localized gene for the steroid STS cause a skin condition known as X-linked ichthyosis (5), due to a build-up of cholesterol sulfate in the stratum corneum of the skin and visible scaling. Androgen metabolism and steroid secretion had been studied recently in a cohort of male X-linked ichthyosis patients before and after puberty (162). Circulating DHEAS was increased in these patients, whereas serum DHEA and testosterone were decreased. Interestingly, a prepubertal surge in the serum DHEA to DHEAS ratio could be seen in healthy controls that was absent in patients with X-linked ichthyosis, indicative of physiologically up-regulated STS activity before puberty (162).

Inactivating mutations in SUMF1 cause multiple sulfatase deficiency (MSD), a rare and fatal autosomal recessive disorder with a rather complex phenotype, characterized by absent activity of all sulfatase enzymes (5). To date, there are about 30 mutations of the SUMF1 gene reported in patients with MSD. Clear genotype–phenotype correlations have been observed linked to the residual activity of SUMF1 (163) and protein stability (164) leading to manifestations with severe neonatal, late infantile, or rarer mild juvenile forms of MSD (165, 166).

Variation in sulfation pathways in plants

In plants, the origin and evolution of sulfation pathways are intriguing questions. Zhao et al. (167) compared the evolution of genes connected to retrograde signaling in the green lineage, including sulfation pathways because of PAP. Interestingly, although TPST genes are present in all basal plants, green and streptophyte algae, SOTs are present only in Gymnosperms and Angiosperms, with exception of some but not all chlorophytes (167). Therefore, maybe the hunt for the essential sulfated compound should concentrate on the moss Physcomitrella patens or the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha, which do not possess SOTs but only five or two TPST-like genes, respectively, and four or two APS kinases (167).

Most of our knowledge on plant sulfation pathways is derived from Arabidopsis, not only because it is a model species but also because as a member of the Brassicaceae it produces large quantities of glucosinolates. The following question thus arises. What is the importance of sulfation pathways in plants that do not produce glucosinolates and do not have a large flux through the secondary assimilation pathway? However, some of these species have SOT families with more isoforms than Arabidopsis, for example, cotton and eucalyptus possess 45 SOTs (167), although not a single sulfated compound is known in these species. Comparison of regulation of the sulfation pathways and their coordination with primary sulfur metabolism between Arabidopsis and species without many sulfated compounds would thus be very informative. But similarly interesting are comparisons with species that produce other sulfated metabolites. For example, the species of genus Flaveria, which are a model for evolution of C4 photosynthesis (168), produce a variety of sulfated flavonoids (169). The first plant SOTs have been characterized from Flaveria and were shown to be specific not only for a metabolite but also the position of the hydroxyl to be sulfated (66). Sulfated flavonoids represent a large pool of sulfur in Flaveria. Indeed, in Flaveria pringlei 4.6% of sulfur can be found in quercetine 3-sulfate, and therefore 4-fold more than in GSH (170). The regulation of synthesis of sulfated flavonoids is completely unknown. Particularly, comparison of the regulation by sulfur starvation between sulfated flavonoids and the glucosinolates would provide important insights into general and specific regulatory processes in plant-sulfated metabolome.

Arabidopsis ecotypes

Natural variation in plants has been extensively used to understand genetic control of various traits (171). Starting with a population of two-parent recombinant lines and genotyping of hundreds of DNA markers, the extensive genome sequencing and high throughput marker data are available for Arabidopsis ecotypes. Such data allow for the harnessing of variation within hundreds of genotypes with the depth of 100,000 markers. Some of these approaches have also been used to improve our knowledge of sulfation pathways (172, 173).

On the forefront of these efforts was the dissection of variation in glucosinolates. Crop varieties and Arabidopsis ecotypes show an enormous variation in qualitative and quantitative glucosinolate composition. Many biosynthetic genes were initially mapped as quantitative trait loci (172). The variation in glucosinolates was shown through genome-wide association mapping to be linked with variation in susceptibility to herbivores (173). In this respect, the variation in substrate specificity in Arabidopsis desulfo-glucosinolate SOTs (83) is particularly interesting, because it may contribute to the variation in glucosinolates but may also be a consequence of the different glucosinolate profiles.

The power of the natural variation approach was demonstrated by two studies showing the importance of the APR2 isoform of APS reductase for control of sulfate and sulfur accumulation (174, 175). APR2 is responsible for ∼75% of the total APS reductase activity in Arabidopsis. Several independent rare SNPs have been found which inactivate the enzyme and consequently reduce the flux through primary sulfate assimilation and lead to accumulation of the initial metabolite, sulfate (174, 175). One of the populations studied in these reports, the lines derived from a cross between Arabidopsis accessions Bay-0 and Shahdara, helped to find a similar link between the ATPS1 isoform of ATP sulfurylase and sulfate accumulation (29). Although the coding sequences of ATPS1 from the two accessions are identical, the genes differ by an insertion/deletion in an intron that is associated with significant enhancement of transcript levels. A similar deletion is found in a range of accessions, where it is also linked with lower ATPS1 transcript levels and higher sulfate content (29). Also for ATPS1, an accession was found in which a nonsynonymous SNP led to inactivation of the enzyme (16). The availability of genome sequences of more than a thousand Arabidopsis accessions makes further studies of a structure–function relationship possible (176).

Open questions

Sulfation pathway research at the systems level is, in essence, learning by analogy. The studies to understand sulfation pathways in plants and animals have come a long way in recent years, and repeatedly the findings in one-model systems have fostered studies and new findings in the other (177, 178). There are, however, still many questions waiting to be answered, and some of these are prompted by comparative pathway analysis.

Complete inventory of components

Despite the full genomic sequences of many plants and vertebrates, including humans, we cannot be sure that all components of sulfation pathways have been discovered. This is particularly true for plants, where clearly at least one gap exists; we still do not know how PAPS reaches the TPST located in Golgi. In addition, PAP seems not to be degraded in the Golgi as no SAL1 or gPAPP homologue was detected in this organelle. So, how is it turning back to its signaling role after PAPS is consumed in the Golgi? Also, the glucosinolate data from studies of Arabidopsis papst1 and papst2 mutants (36, 159) indicate that there might be another PAPS transporter in plant chloroplasts.

Another question is the peptide/protein sulfation. The number of plant-sulfated peptides discovered is growing as is the knowledge of their importance in cellular signaling (104, 179). As the Arabidopsis tpst knockout results only in a mild phenotype, are there other isoforms of this protein similar to humans? If so, where would they be localized? Finding new sulfotransferases is entirely possible for both plants and humans. AtTPST was discovered relatively recently as it did not show high-sequence similarity with other plant SOTs and the TPSTs from humans (69). Furthermore, gene numbers of vertebrate sulfotransferases vary considerably (5). Although the SULT2A1 gene has undergone a dramatic expansion in rodents, with eight genes in the mouse (71), it is the SULT1A gene that has undergone an expansion in primates, with four genes in humans (70) and with a gene-copy polymorphism between individuals (180). Moreover, the number of known Arabidopsis SOTs increased from 18 to 21 between 2004 and 2014 (4, 181).

In addition, no sulfatase gene has yet been identified in plants, and the catabolism of sulfated metabolites other than glucosinolates is not known. Therefore, there may be unknown enzymes to recycle the sulfate from such molecules by hydrolysis or another mechanism, or plant SOTs may catalyze the reverse reaction. Generating a complete inventory of components of sulfation pathways will be as challenging and interesting as defining a minimal functioning sulfation pathway.

Transient protein interactions and functional gene fusions

Human sulfotransferase SULT2A1 interacts with PAPSS2, most likely to boost the sulfation of the androgen precursor DHEA (44). The actual function of this complex of a PAPS-producing and a PAPS-utilizing enzyme remains to be determined on a molecular effect. With novel methodology of capturing weak and transient protein interactions (such as proximity ligation assays for in situ cross-linking (182)), it is possible that more such protein interactions within sulfation pathways will be discovered. Likely candidates are enzymes that are fused to a single polypeptide in some species but occur as separate proteins in others, such as plant APS kinase and ATPS (7). In primary sulfate assimilation, protein–protein interactions were indeed described for onion ATPS and APS reductase (183).

Moreover, the functionality of known, but little understood, fusion proteins is of interest. If these fusions lead to improved catalysis, it would be rewarding to study the ATPS–APS kinase gene fusion with pyrophosphatase found in the microalgae (7) as this might increase the rate of PAPS synthesis and biological sulfation pathways. Of particular interest is the ATPS–APS reductase fusion from the dinoflagellate H. triquetra (7). First, the protein is the only ATPS fusion with the cyanobacterial/chlorophyte form of ATPS; second, it may have a great influence on primary sulfate assimilation and synthesis of cysteine, methionine, and other important compounds; and third, it may better outcompete APS kinase and so reduce the provision of activated sulfate for sulfation pathways.

Redox regulation of sulfation pathways

Regulation of sulfation pathways by protein redox mechanisms is intriguing, particularly in context of the whole-sulfur metabolism (34). The reciprocal redox regulation of APS reductase and APS kinase in Arabidopsis (described above and in Refs. 40, 41) might serve as a mechanism to control the partitioning of sulfur into plant primary and secondary metabolism (11). Combined with the redox regulation of SAL1 (134) and of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, the key enzyme in GSH synthesis in primary assimilation (184), there is mounting suggestion of important redox regulatory control of sulfur fluxes in plants. However, the importance of the redox regulation of APS kinase remains to be demonstrated in vivo as well as an exact quantification of the effects of cellular redox potential on the sulfur fluxes.

The redox regulation of APS kinase and γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase is confined to plants and does not occur in related enzymes from cyanobacteria or proteobacteria (40, 185). Plant APS reductase and related bacterial APS and PAPS reductases use the same mechanism with active cysteine residue (10) and can therefore be expected to be affected by redox changes. The redox regulation of SAL1 is conserved between plants and yeast despite the yeast enzyme not possessing the same redox-active Cys pair as the plant line (134). In contrast, ATPS from the microalgae was shown to be redox-regulated (186), whereas no indication of such control was described for plants. The questions regarding when the redox regulation of sulfur metabolism have evolved, and whether this regulation is also conserved in Metazoa remain open. Since Lansdon et al. (54) showed that the recombinant PAPSS1 protein is activated by incubation in DTT, it seems indeed that redox regulation may contribute to the control of function of human PAPS synthases.

Function of promiscuous proteins versus function of sulfated metabolites

PAPS biosynthesis is essential for plants and animals, but why? The search for the specific essential metabolite(s) in plants or animals has not been successful so far. One reason for this is that there is only weak correlation between the function of a promiscuous sulfotransferase and one of its sulfated metabolites. The same holds true for PAP phosphatases. A phenotype obtained from a single-gene knockout of a SULT is not direct evidence for the biological function of one of its substrates. For example, the human estrogen sulfotransferase SULT1E1 is as efficient in DHEA sulfation as SULT2A1 (187). Two independent sulfation processes regulate development of a predatory nematode (188), but no sulfated metabolism is yet known. Bruce et al. (189) reported an intracellular PAPS-dependent step during HIV infection. The same group later reported an involvement of cytoplasmic sulfotransferase SULT1A1 (190), but again the actual sulfated metabolite that interacted with HIV infection is not yet known.

In plants, the number of phenotypes caused by loss of SAL1 has been ascribed first to defects in inositol signaling and then to PAP (8, 132); however, a thorough analysis by complementing the mutants with enzymes of single activity has not been described. Furthermore, dissection of amino acid residues important for reactions with the different substrates (inositol polyphosphates, PAP, and PAPS) has not been performed. Indeed, the importance of dephosphorylation of PAPS to APS has not been investigated. Another intriguing question concerning plant SAL1 is its mitochondrial localization (122), as mitochondria do not play a known role in sulfation pathways.

The function and substrate specificity of a number of plant SOTs is unknown. This corresponds to the discovery of a large number of unknown sulfur-containing metabolites in Arabidopsis (87). Identification of new sulfated metabolites and the mix and match with the SOT specificities will bring more clarity to the importance of plant sulfation pathways and allow the search for the essential sulfated metabolites.

Thought provokingly, what if in fact the sulfotransferase protein itself or a by-product of sulfation pathways is the actual essential agent? Human SULT4A1 is among the most conserved sulfotransferases within vertebrates (3). However, this protein lacks essential catalytic residues. Mouse studies suggest that SULT4A1 is not an actual sulfotransferase but is a neuronal protein required for normal brain function (191). Similarly, at least some parts of sulfation pathways may just run to generate sufficient quantities of PAP for the associated signaling.

Finally, activated sulfate in the form of PAPS could also be referred to as “sulfo-ATP.” Analogous to sulfo-ATP, one may ask what ATP is good for. Therefore, perhaps the question of which single sulfated metabolite is essential is not relevant.

Potential applications

Studying sulfation pathways in humans has the potential to reveal novel biomarkers and mechanisms of human disease. The field has the promise to advance by deep-phenotyping bodily samples from patients with rare genetic mutations in sulfation pathway genes. However, even more progress can be expected from exploring disease association of individuals showing hypo-sulfation such as the heterozygous PAPSS2+/− alleles described above.

A second field of possible application is the development of pharmacological interventions, including specific inhibitors, modulators, and stabilizers for sulfation pathway proteins. A stand-out sulfated metabolite is the sulfated carbohydrate heparin (192), which is known for its huge commercial market and the consistent attempts to make new and better heparins by understanding the control of its biosynthesis and sulfation (193). In addition, desulfation has a major impact for steroid-dependent cancer types (5). Hence, STS represents a central target for anti-cancer drug development. The STS inhibitor irosustat promisingly passed phase II clinical trials (5), and further drug development efforts are ongoing (194, 195).

Another compound with a commercial potential is an intermediate in sulfation pathways, the APS. APS is used in pyrosequencing where pyrophosphate, generated by incorporation of dNTP into a DNA strand, is joined by ATP sulfurylase with APS to form ATP, which is then detected by luciferase (196, 197). Pyrosequencing is limited by the costs of reagents, including APS. APS synthesis may thus be optimized by the ATPS fusion proteins either directly or through PAPS and nuclease-driven dephosphorylation (198), in turn reducing costs.

Glucosinolates, the best known sulfated metabolites from plants, are important for plant immunity (32) and have well-characterized positive health properties for human consumption (81). Increasing plant glucosinolate content is a promising strategy for both improving crop resistance to pathogens and nutritional quality. The latter has been demonstrated by increasing the synthesis of glucoraphanin in broccoli and improving its anti-carcinogenic property (199). Recent progress in synthetic biology has engineered glucosinolate synthesis into non-Brassicaceae plants normally unable to produce such metabolites (200), increasing potentially the range of crops for enhancement of nutritional quality. Interestingly, the production of glucosinolates was initially limited by the rate of PAPS synthesis (201), underlying the importance of basic research in sulfation pathways.

How to answer all these questions

In addition to investigations at the systems level, newly developed technologies will certainly provide the cutting edge in sulfation pathway research. On the one hand, these are analytical nature–advanced methods to detect, characterize, and quantitate various sulfo-conjugates such as peptides (99), steroids (202), or plant secondary metabolites (170). On the other hand, these also represent novel chemo-synthetic approaches to obtain good purity sulfated nucleotides (203), steroid reference material (204), or sugars (205). Comparative approaches between kingdoms on genomics or synthetic biology levels will also bring new insights. The so-far missing approach, which has a great potential to uncover new and unexpected regulatory mechanisms, is modeling, aimed at structures and metabolite docking as well as control flux analysis. The latter will have to consider the sulfation pathways within a full metabolic reconstruction, as limitation of flux analysis to sulfur fluxes does not provide unique solutions (28). Such study will be highly informative for understanding the links between sulfation pathways and regulation of metabolism of carbon acceptors.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under Germany's Excellence Strategy–EXC 2048/1, Project 390686111 (to the S. K. laboratory), DFG Project KO2065/13-1 (to S. G.), European Commission Marie Curie Fellowship SUPA-HD 625451, Wellcome Trust (ISSF Award), and the Medical Research Council UK (Proximity-to-Discovery) (to the J. W. M. laboratory). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PAPS

- 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate

- APS

- adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate

- ATPS

- ATP sulfurylase

- PAPSS

- PAPS synthase

- TPST

- tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase

- SOT

- sulfotransferase

- SULT

- SULT, cytosolic sulfotransferase

- DHEA

- dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHEAS

- dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- STS

- steroid sulfatase

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- PAP

- 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate

- gPAPP

- Golgi PAP phosphatase

- MSD

- multiple sulfatase deficiency

- OATP

- organic anion transporter

- SNP

- single-nucleotide polymorphism.

References

- 1. Beinert H. (2000) A tribute to sulfur. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5657–5664 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01637.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahashi H., Kopriva S., Giordano M., Saito K., and Hell R. (2011) Sulfur assimilation in photosynthetic organisms: molecular functions and regulations of transporters and assimilatory enzymes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 62, 157–184 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coughtrie M. W. H. (2016) Function and organization of the human cytosolic sulfotransferase (SULT) family. Chem. Biol. Interact. 259, 2–7 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hirschmann F., Krause F., and Papenbrock J. (2014) The multi-protein family of sulfotransferases in plants: composition, occurrence, substrate specificity, and functions. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 556 10.3389/fpls.2014.00556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mueller J. W., Gilligan L. C., Idkowiak J., Arlt W., and Foster P. A. (2015) The regulation of steroid action by sulfation and desulfation. Endocr. Rev. 36, 526–563 10.1210/er.2015-1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mueller J. W., and Shafqat N. (2013) Adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate–a multifaceted modulator of bifunctional 3′-phospho-adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate synthases and related enzymes. FEBS J. 280, 3050–3057 10.1111/febs.12252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patron N. J., Durnford D. G., and Kopriva S. (2008) Sulfate assimilation in eukaryotes: fusions, relocations and lateral transfers. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 39 10.1186/1471-2148-8-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]