The nosocomial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulates its virulence via a complex quorum sensing network, which, besides N-acylhomoserine lactones, includes the alkylquinolone signal molecules 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (Pseudomonas quinolone signal [PQS]) and 2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone (HHQ). Mycobacteroides abscessus subsp. abscessus, an emerging pathogen, is capable of degrading the PQS and also HHQ. Here, we show that although M. abscessus subsp.

KEYWORDS: Mycobacteroides abscessus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas quinolone signal, dioxygenase, lactonase, quorum quenching enzyme, quorum sensing

ABSTRACT

The nosocomial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa regulates its virulence via a complex quorum sensing network, which, besides N-acylhomoserine lactones, includes the alkylquinolone signal molecules 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (Pseudomonas quinolone signal [PQS]) and 2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone (HHQ). Mycobacteroides abscessus subsp. abscessus, an emerging pathogen, is capable of degrading the PQS and also HHQ. Here, we show that although M. abscessus subsp. abscessus reduced PQS levels in coculture with P. aeruginosa PAO1, this did not suffice for quenching the production of the virulence factors pyocyanin, pyoverdine, and rhamnolipids. However, the levels of these virulence factors were reduced in cocultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 with recombinant M. abscessus subsp. massiliense overexpressing the PQS dioxygenase gene aqdC of M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, corroborating the potential of AqdC as a quorum quenching enzyme. When added extracellularly to P. aeruginosa cultures, AqdC quenched alkylquinolone and pyocyanin production but induced an increase in elastase levels. When supplementing P. aeruginosa cultures with QsdA, an enzyme from Rhodococcus erythropolis which inactivates N-acylhomoserine lactone signals, rhamnolipid and elastase levels were quenched, but HHQ and pyocyanin synthesis was promoted. Thus, single quorum quenching enzymes, targeting individual circuits within a complex quorum sensing network, may also elicit undesirable regulatory effects. Supernatants of P. aeruginosa cultures grown in the presence of AqdC, QsdA, or both enzymes were less cytotoxic to human epithelial lung cells than supernatants of untreated cultures. Furthermore, the combination of both aqdC and qsdA in P. aeruginosa resulted in a decline of Caenorhabditis elegans mortality under P. aeruginosa exposure.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major opportunistic bacterial pathogen in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis (CF) and a frequent cause of nosocomial infections (1). Many of the virulence-associated traits of P. aeruginosa are regulated via a complex quorum sensing network incorporating the N-acylhomoserine lactone (AHL)-dependent systems las and rhl as well as the alkylquinolone (AQ)-dependent Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) system (2–4). The las system consists of the transcriptional activator LasR and the signal synthase LasI, which catalyzes the formation of N-(3-oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone (3oDHL). The rhl system comprises RhlR and the N-butyryl homoserine lactone (BHL) synthase RhlI. The PQS system, besides its major signal molecule 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (the PQS), also uses 2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone (HHQ), with both signal molecules acting as coinducing ligands of the transcriptional activator PqsR (MvfR). HHQ biosynthesis is encoded by the pqsABCDE genes, which are positively regulated by PQS- or HHQ-bound PqsR. The three quorum sensing systems in P. aeruginosa, all of which feature the characteristic autoinduction by their specific signal-receptor complexes, are interconnected (4, 5). The las system activates rhlI and rhlR and also activates the PQS system. The PQS system has an inducing effect on the rhl system but in turn is repressed by the rhl system. The PQS system is involved in the regulation of a variety of virulence factors, including the siderophore pyoverdine, rhamnolipid biosurfactants, and the redox-active pigment pyocyanin (3, 4, 6). In addition to its function as a signaling molecule, PQS has iron-trapping properties, induces membrane vesicle formation, and acts as a prooxidant (7–9). HHQ shows bacteriostatic activity, and both HHQ and PQS can repress motility in various bacteria (10). 2-Alkyl-4-hydroxyquinoline-N-oxides like HQNO (2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline-N-oxide), which also derive from the AQ biosynthetic pathway, act as antibiotics by inhibiting cytochrome bc1-dependent respiratory electron transfer and pyrimidine biosynthesis (11). Therefore, interference with the AQ system is a promising antivirulence strategy.

Many enzymes catalyzing the hydrolysis of AHLs have been described in the literature, but only few enzymes active toward PQS are known (12). The first enzyme described to cleave PQS was 1H-3-hydroxy-4-oxoquinaldine 2,4-dioxygenase (HodC) from Arthrobacter sp. strain Rue61a. Although its activity toward PQS is low and fortuitous, the addition of HodC to P. aeruginosa PAO1 ΔpqsA, supplemented with exogenous PQS, led to a reduction of virulence factors (13). The soil isolate Rhodococcus erythropolis BG43 was the first bacterium identified to be capable of specifically degrading HHQ and PQS (14). Two gene clusters, termed aqdA1B1C1 and aqdRA2B2C2, are involved in HHQ and PQS degradation, and PQS dioxygenase activity was shown for the purified AqdC1 enzyme (15). Remarkably, a gene cluster homologous to aqdRA2B2C2 is also present in the genome of Mycobacteroides (formerly Mycobacterium) abscessus subsp. abscessus, which indeed is able to rapidly degrade PQS and to convert HHQ to PQS (16). M. abscessus subsp. abscessus belongs to the rapidly growing mycobacterial species and is considered the major nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) infecting patients suffering from CF (17). Infections with M. abscessus subsp. abscessus are classified as a contraindication for lung transplantation in many cases (18), because of the fact that these bacteria are often impossible to eradicate despite prolonged and combined antibiotic therapies. P. aeruginosa is frequently coisolated in CF patients with NTM infections (19–21).

CF is a hereditary disease caused by mutations of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene, which encodes an ion channel located in the apical membrane of epithelial cells (22). The airways of CF patients are characterized by thickened mucus with an impairment of mucociliary clearance leading to chronic and recurrent infections of special CF-related pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus in early infancy and P. aeruginosa in more than 80% of adults (1, 22). Such infections are treated with regular antibiotic therapies, leading to better survival of patients, but the emergence of multiresistant strains and emerging pathogens such as M. abscessus subsp. abscessus represent a huge challenge (21, 23). In CF patients with pulmonary P. aeruginosa infection, AQs were detectable in the sputum and plasma (24).

Clinical isolates of M. abscessus from CF patients were identified and characterized, among others, by Rüger et al. (25). Among the 50 strains described in this study, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus strains harbored a chromosomal aqdRABC gene cluster, whereas isolates of M. abscessus subsp. massiliense lacked the aqd genes (16). The key enzyme for PQS inactivation is AqdC, a dioxygenase catalyzing quinolone ring cleavage (16). These findings raised the question of whether the presence of aqd genes is relevant in interactions of M. abscessus with P. aeruginosa. From a more application-oriented point of view, another interesting issue is whether mycobacterial AqdC can be used as a quorum quenching enzyme for reducing the virulence of P. aeruginosa.

In this study, we analyzed whether the ability of M. abscessus subsp. abscessus to degrade the P. aeruginosa quorum sensing signal molecules PQS and HHQ affects the levels of the signaling molecules and of extracellular virulence factors in a P. aeruginosa-M. abscessus coculture setting. Moreover, we investigated the effect of purified AqdC, also in combination with the rhodococcal lactonase QsdA, which inactivates a broad range of AHLs (26–28), on the levels of extracellular virulence factors of P. aeruginosa. The cytotoxicity of P. aeruginosa culture supernatants to human epithelial lung cells was assessed after incubation of the cultures with AqdC and QsdA, and the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa expressing aqdC and qsdA was analyzed in a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model.

RESULTS

M. abscessus subsp. abscessus in coculture with P. aeruginosa PAO1 is able to reduce PQS levels, but reduced virulence factor production is observed only in cocultures of PAO1 with an aqdC-overexpressing Mycobacterium strain.

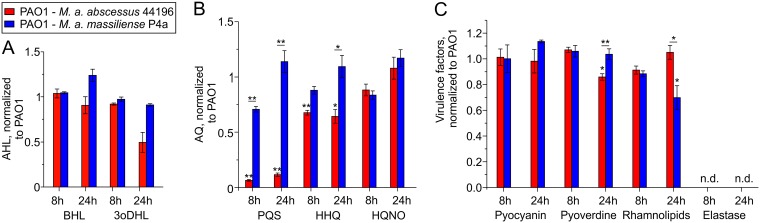

To test whether M. abscessus strains can affect the levels of P. aeruginosa signal molecules and virulence factors, we set up cocultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 with M. abscessus subsp. abscessus DSM44196, which, due to the presence of the aqdRABC gene cluster, is able to rapidly degrade PQS, and with M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a, which lacks the aqd genes but nevertheless very slowly converts PQS (16). The concentrations of the AHL signal molecules BHL and 3oDHL were not or were only slightly affected when cocultivating P. aeruginosa PAO1 with M. abscessus subsp. abscessus or M. abscessus subsp. massiliense (Fig. 1A). To verify PQS dioxygenase (AqdC) activity in M. abscessus subsp. abscessus DSM44196, we determined PQS conversion by cell extract supernatants. Extracts of cells induced with 20 μM PQS 2 h prior to harvesting showed AqdC activity of 9.3 mU (mg protein)−1 (9.3 × 10−3 μmol PQS [mg protein]−1 min−1). Consistent with the presence of an active PQS dioxygenase in M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, PQS concentrations were clearly reduced in the PAO1-M. abscessus subsp. abscessus coculture; however, HHQ was still present at almost the same levels as in the PAO1 solo culture (Fig. 1B). Thus, despite the reduced levels of PQS, which acts as the main coinducer of the AQ biosynthetic operon pqsABCDE, AQ biosynthesis was not noticeably quenched in this coculture, as also indicated by the high levels of HQNO (Fig. 1B). Pyocyanin, pyoverdine, and rhamnolipid production by P. aeruginosa likewise was largely unaffected by the presence of M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (Fig. 1C). The observed decrease in rhamnolipid levels in the PAO1-M. abscessus subsp. massiliense coculture after 24 h seems to be unrelated to quorum sensing signaling.

FIG 1.

AHLs (A), AQs (B), and virulence factor production (C) in cocultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 with M. abscessus subsp. abscessus DSM44196 or with M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a, normalized to solo cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1. CFU counts after 8 h were 2.87 × 108 ± 1.91 × 107 CFU/ml for PAO1 in solo culture; 2.26 × 108 ± 1.46 × 107 and 2.11 × 107 ± 5.85 × 106 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus DSM44196, respectively, in coculture; and 2.27 × 108 ± 1.20 × 107 and 4.9 × 107 ± 4.73 × 106 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a, respectively, in coculture. CFU counts after 24 h were 7.22 × 108 ± 4.01 × 107 CFU/ml for PAO1 in solo culture; 8.61 × 108 ± 1.12 × 107 and 3.68 × 104 ± 6.23 × 103 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus DSM44196, respectively, in coculture; and 6.67 × 108 ± 5.09 × 107 and 5.08 × 105 ± 6.43 × 106 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a, respectively, in coculture. Data represent means ± standard errors (SE) from three independent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was carried out using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or a Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test. P values assigned to individual bars refer to solo cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

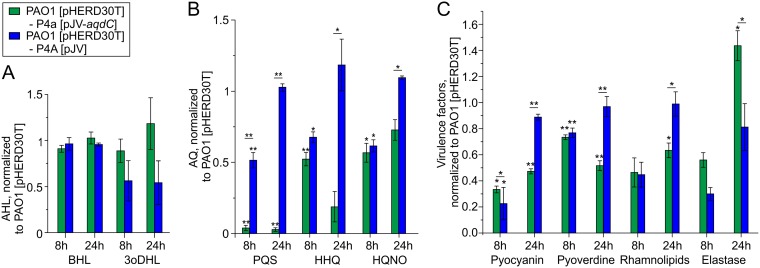

We also constructed a recombinant M. abscessus subsp. massiliense(pJV-aqdC) strain for comparing its effect on P. aeruginosa exoproduct formation with that of the M. abscessus subsp. massiliense wild-type strain. BHL levels were unaffected by the presence of the recombinant M. abscessus subsp. massiliense strains (Fig. 2A). The observed change in 3oDHL levels might be due to different growth dynamics of P. aeruginosa in the cocultures (see the legend to Fig. 2 for CFU data). Extracts of M. abscessus subsp. massiliense(pJV-aqdC) showed about 29-fold-higher AqdC activity (272 mU mg−1, or 0.272 μmol PQS [mg protein]−1 min−1) than PQS-induced cells of wild-type M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, indicative of aqdC overexpression from the gfp promoter of the pJV53 plasmid (29). Consistent with the high AqdC activity of the recombinant strain, PQS concentrations were drastically reduced in cocultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 with M. abscessus subsp. massiliense(pJV-aqdC). The depletion of PQS also led to decreases in HHQ and HQNO concentrations in the coculture with M. abscessus subsp. massiliense(pJV-aqdC) (after 8 h), presumably due to decreased induction of the pqsABCDE biosynthetic operon, as well as in reduced pyocyanin, pyoverdine, and rhamnolipid levels in the 24-h coculture (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG 2.

AHLs (A), AQs (B), and virulence factor production (C) in cocultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1(pHERD30T) with M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a(pJV-aqdC) or with M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a(pJV), normalized to solo cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1(pHERD30T). In panel A, AHL levels were normalized to the AHL concentrations in the PAO1 solo culture. CFU counts after 8 h were 4.44 × 107 ± 2.94 × 106 CFU/ml for PAO1 in solo culture; 2.77 × 107 ± 1.45 × 106 and 4.4 × 107 ± 2.2 × 106 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a(pJV-aqdC), respectively, in coculture; and 4.84 × 107 ± 1.39 × 106 and 2.37 × 107 ± 2.47 × 106 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a(pJV), respectively, in coculture. CFU counts after 24 h were 8.33 × 108 ± 1.07 × 108 CFU/ml for PAO1 in solo culture; 6.67 × 108 ± 3.33 × 107 and 2.43 × 105 ± 5.07 × 104 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a(pJV-aqdC), respectively, in coculture; and 1.07 × 109 ± 1.35 × 108 and 9.58 × 106 ± 8.92 × 104 CFU/ml for PAO1 and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a(pJV), respectively, in coculture. Data represent means ± SE from three independent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was carried out using ANOVA or a Tukey HSD test. P values assigned to individual bars refer to solo cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1(pHERD30T) (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Taken together, the data show that in the dual-species coculture setup, the reduction of PQS levels by wild-type M. abscessus subsp. abscessus was not sufficient for significant downregulation of AQ biosynthesis and for attenuating the production of diverse virulence factors by P. aeruginosa. However, overexpression of aqdC in M. abscessus subsp. massiliense clearly reduced the levels of P. aeruginosa AQ signals and some extracellular virulence factors in the cocultures, suggesting that the PQS dioxygenase AqdC, if present in a sufficient quantity, has the potential to quench P. aeruginosa virulence. Therefore, we analyzed its effect on the formation of P. aeruginosa exoproducts when added extracellularly to P. aeruginosa cultures.

Addition of the PQS dioxygenase AqdC to P. aeruginosa PAO1 cultures quenches AQ and pyocyanin production but increases elastase levels.

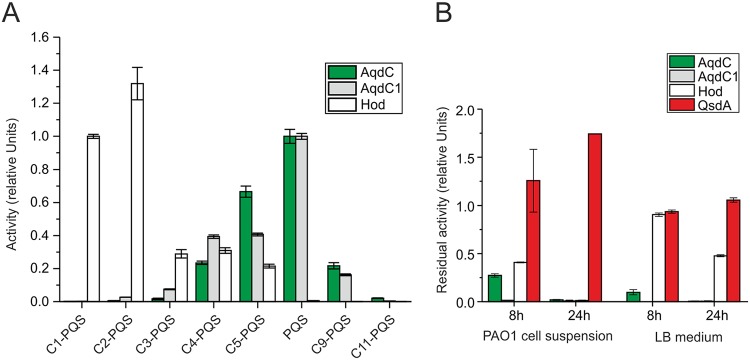

AqdC of M. abscessus subsp. abscessus as well as AqdC1 of R. erythropolis BG43 catalyze the cleavage of 2-alkyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolones with a clear preference for the C7 congener PQS, in contrast to HodC from Arthrobacter sp. Rue61a, which shows the highest activity toward the C2 and C1 congeners (Fig. 3A). Purified AqdC and AqdC1 have specific activities toward PQS of 53 U mg−1 (53 μmol min−1 mg−1) (16) and 15.3 U mg−1 (15), respectively, while HodC activity with PQS is about 0.2 U mg−1 (15). A major drawback of HodC for use as a quorum quenching enzyme, besides its low activity for PQS, is its degradation by extracellular proteases produced by P. aeruginosa (13, 30). Figure 3B illustrates that HodC is quite stable in pure LB medium at 37°C but rapidly loses activity when incubated in P. aeruginosa cell suspensions. Rhodococcal AqdC1 is completely inactivated after 8 h at 37°C (both in LB medium and in cell suspensions), while mycobacterial AqdC retained about 25% activity when incubated for 8 h at 37°C in PAO1 cell suspensions. However, AqdC loses activity when incubated in LB medium at 37°C, indicating thermal instability (Fig. 3B). Nevertheless, among the PQS-cleaving enzymes described so far (13, 15), AqdC is the most promising enzyme due to its high activity combined with a comparatively good persistence in P. aeruginosa cultures.

FIG 3.

Substrate specificity of AqdC, AqdC1, and Hod (A) and stability of the dioxygenases and the lactonase QsdA (B). (A) Activities of AqdC and AqdC1 were normalized to the activity toward PQS, whereas the activity of Hod was normalized to the activity of its natural substrate C1-PQS. (B) Residual activity of the quorum quenching enzymes after incubation for 8 and 24 h at 37°C in P. aeruginosa PAO1 cell suspensions or in LB medium, normalized to the values before incubation (set to 1). For determining QsdA activity in cell suspensions, the lactonase activity of untreated P. aeruginosa cell suspensions was subtracted from the total lactonase activity of QsdA-treated cell suspensions. Data represent means ± SE from three technical replicates.

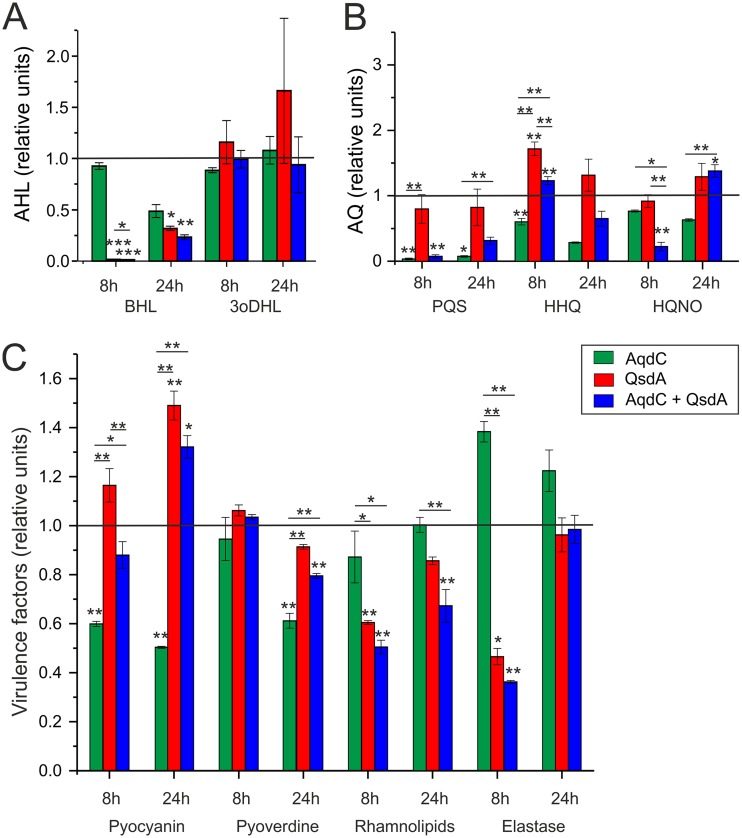

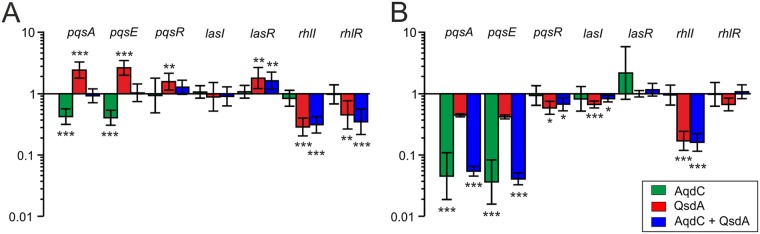

The addition of 5 U AqdC to a 15-ml culture of P. aeruginosa PAO1 resulted in decreased BHL levels (after 24 h) (Fig. 4A) and drastically decreased PQS levels (Fig. 4B). It also attenuated AQ biosynthesis, as indicated by the reduced HHQ and HQNO levels (Fig. 4B), probably due to a decrease in pqsABCDE expression in the absence of the coinducer PQS. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses confirmed that transcription of the pqsA and pqsE genes was reduced in cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 supplemented with AqdC, while transcription of pqsR (mvfR), which is controlled positively by LasR and negatively by RhlR (31), was not affected (Fig. 5). The pqs system is interconnected via feedback loops with the rhl and las systems (32, 33); however, interference with the pqs circuit by AqdC did not significantly influence rhl and las transcription under the conditions tested. Nevertheless, AqdC addition to PAO1 cultures quenched pyocyanin levels (at 8 h and 24 h) and also pyoverdine production (at 24 h). However, elastase production was increased in the presence of AqdC (Fig. 4C). In line with this finding, a somewhat increased elastase level was also observed in the P. aeruginosa PAO1-M. abscessus subsp. massiliense(pJV-aqdC) cocultures after 24 h (Fig. 2C).

FIG 4.

AHLs (A), AQ concentrations (B), and virulence factor production (C) in cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1 after addition of 0.3 U/ml (5.66 μg/ml) AqdC, 0.255 mg/ml QsdA, and the combination of both enzymes. Levels of virulence factors and signal molecules in P. aeruginosa PAO1 supplemented with buffer without any enzymes are set to 1 and are represented by the black lines. Data represent means ± SE from three independent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was carried out using ANOVA or a Tukey HSD test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

FIG 5.

Relative transcription levels of quorum sensing-associated genes in P. aeruginosa PAO1 cultures in the presence of quorum quenching enzymes. Shown are fold changes in gene expression in response to the addition of 0.3 U/ml (5.66 μg/ml) AqdC, 0.255 mg/ml QsdA, and the combination of both enzymes to LB cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO1, normalized to the transcription of the internal control gene rpoS after 8 h (A) and 24 h (B). Transcript amounts of PAO1 cultures in the absence of quorum quenching enzymes were set to 1. Data represent means ± standard deviations (SD) from three biological replicates measured in at least technical duplicates each. Statistical analysis was carried out using ANOVA or a Tukey HSD test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

The AHL lactonase QsdA quenches rhamnolipid and also elastase production but promotes HHQ and pyocyanin synthesis by P. aeruginosa.

QsdA of Rhodococcus erythropolis is a broad-spectrum AHL lactonase capable of hydrolyzing C4 to C14 AHLs with or without a hydroxyl or oxo substitution on C3 (26–28). This enzyme is remarkably stable in LB medium at 37°C and in PAO1 cultures (Fig. 3B). However, while incubation of P. aeruginosa cultures with QsdA significantly decreased BHL levels, it did not quench 3oDHL levels (Fig. 4A). RT-qPCRs revealed reduced transcription of the BHL synthase gene rhlI and also of rhlR (Fig. 5), presumably due to the attenuation of rhl autoinduction at low BHL concentrations. In line with the notion that a QsdA-mediated decrease in BHL signaling may reduce the RhlR-mediated repression of the pqsA promoter (31), cultures grown for 8 h in the presence of QsdA showed an enhanced expression of pqsA and pqsE (Fig. 5A) and increased HHQ levels (Fig. 4B). PqsE, besides its role in AQ biosynthesis, is essential for pyocyanin synthesis (33, 34). Indeed, pyocyanin levels were increased, while rhamnolipid and also elastase production (at 8 h) by P. aeruginosa was quenched by QsdA (Fig. 4C). Altogether, the data shown in Fig. 4 indicate that the use of a single quorum quenching enzyme may involve some undesirable effects, resulting in boosting rather than quenching of individual virulence factors.

Virulence factor production by P. aeruginosa PAO1 in the presence of a combination of AqdC and QsdA: a trade-off between quenching and boosting effects.

Simultaneous addition of both enzymes to PAO1 cultures strongly quenched BHL and PQS production, but 3oDHL as well as HHQ levels were still quite high (Fig. 4A and B). The transcription of pqsA, pqsE, as well as rhlI was decreased (at the 24-h time point), consistent with the quenching effects of AqdC and QsdA on pqs and rhl expression, respectively (Fig. 5). Pyocyanin levels were higher than those in the untreated culture after 24 h (Fig. 4C), presumably due to the strong quenching of the rhl system by QsdA. However, the enzyme combination was superior to single enzymes for retarding HQNO production (see the 8-h time point in Fig. 4B) and for quenching rhamnolipid production (8 and 24 h) and also elastase (at 8 h). The production of rhamnolipids is influenced by both the rhl and pqs circuits. Taken together, the levels of P. aeruginosa exoproducts in response to the combination of QsdA and AqdC seem to be the result of a trade-off between the quenching and boosting effects elicited by the individual enzymes.

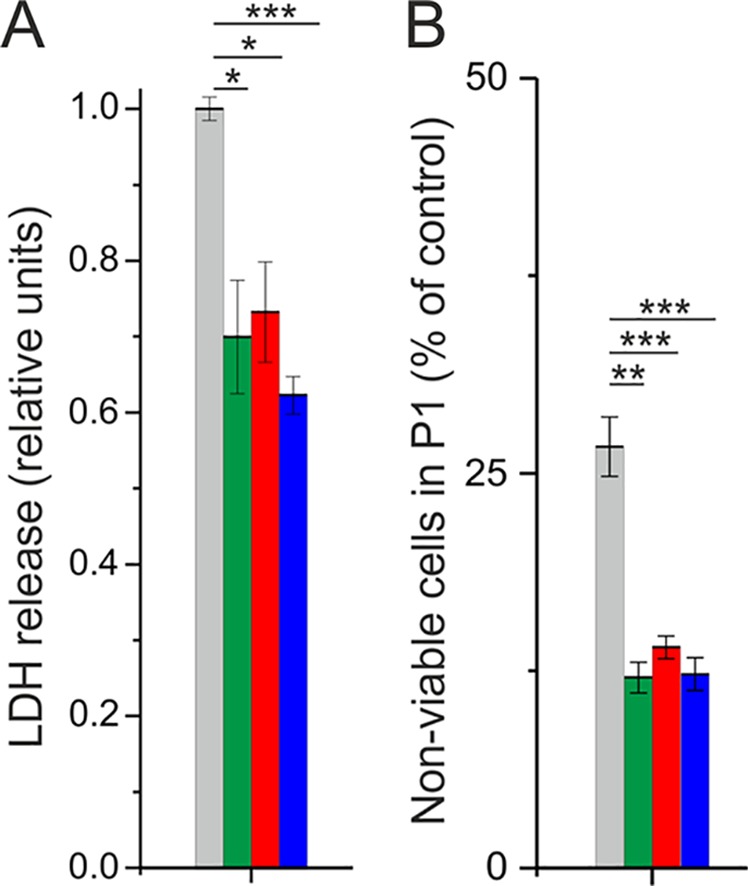

The supernatant of P. aeruginosa PAO1 cultures treated with AqdC and QsdA is less cytotoxic for human epithelial lung cells.

To test whether AqdC and QsdA reduce the overall cytotoxicity of P. aeruginosa exoproducts (which is multifactorial), we analyzed lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from A549 epithelial lung cells in response to the supernatants of PAO1 cultures that were untreated or treated with one or both enzymes. As shown in Fig. 6A, supernatants of PAO1 cultures incubated with AqdC, QsdA, or the enzyme combination were less cytotoxic to A549 cells than supernatants of cultures without enzyme treatment. About 27% of the A549 cells incubated with the supernatant from untreated PAO1 cultures were identified as nonviable by propidium iodide (PI) staining, while in the cell cultures incubated with supernatants of enzyme-treated PAO1 cultures, only about 12 to 13% were nonviable (Fig. 6B). Although the medium of the cell cultures contained high concentrations of human serum albumin (HSA), which might influence the mode of action of P. aeruginosa virulence factors, we detected differences in the cytotoxicity of supernatants from enzymatically treated or untreated PAO1 cultures. However, while treatment of P. aeruginosa cultures with AqdC, QsdA, or both reduced the cytotoxicity of the culture supernatant, an additive or synergistic effect of the two enzymes was not evident.

FIG 6.

Effect of P. aeruginosa PAO1 supernatants on A549 lung epithelial cells. (A) Relative LDH release of A549 cells after incubation with the supernatant of enzymatically treated or untreated PAO1 cultures. LDH release of cells incubated with the supernatant of untreated PAO1 cultures was set to 1. (B) Number of necrotic cells (stained with propidium iodide) counted within the FACS gate that was generated on the basis of untreated control cells (P1) as a percentage of cell numbers in treated compared to untreated control samples. Gray bars represent incubation of A549 cells with the supernatant of untreated PAO1 cultures, and green, red, and blue bars indicate incubation of A549 cells with the supernatant of PAO1 cultures treated with 0.5 U/ml (8.5 μg/ml) AqdC, 0.38 mg/ml QsdA, and a combination of both, respectively. Data represent means ± SE from three independent biological replicates. Statistical analysis was done using Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

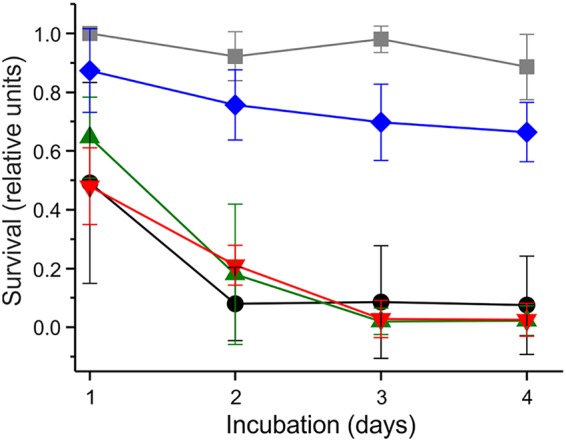

Expression of aqdC and qsdA reduces mortality of Caenorhabditis elegans under PAO1 exposure.

To test whether the expression of aqdC, qsdA, or the combination of both genes in P. aeruginosa PAO1 influences the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa, the mortality of C. elegans under exposure to the respective PAO1 strains was analyzed (Fig. 7). Cultures of PAO1 strains expressing either aqdC, qsdA, or both genes contained reduced levels of signal molecules (<30% PQS, <75% BHL, or a reduction of both signals, respectively), indicating that the enzymes are functional when heterologously produced in P. aeruginosa. Synchronized adult C. elegans hermaphrodites fed with PAO1(pME6032, pBBR1-MCS5), containing two empty plasmids, were killed almost completely after 4 days of incubation. The survival rate of worms under exposure to P. aeruginosa PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR1-MCS5) or P. aeruginosa PAO1(pME6032, pBBR::qsdA), expressing either the PQS dioxygenase or the AHL lactonase gene, did not differ from the survival rate after exposure to PAO1 containing empty plasmids. In contrast, expression of the combination of aqdC and qsdA in PAO1 significantly reduced the mortality of C. elegans. The survival rate of C. elegans exposed to this recombinant PAO1 decreased comparatively slowly, with 78% of worms still being alive after 4 days of incubation. Noting that the growth rate of recombinant PAO1 strains harboring pME-aqdC is 75% of that of strains not expressing the aqdC gene (see the legend to Fig. 7), we cannot exclude that differences in bacterial growth influence the mortality of infected C. elegans. However, if the increased survival upon infection with P. aeruginosa PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR::qsdA) was mainly the result of slower growth of the pathogen, we would have expected a similar survival curve for C. elegans infected with P. aeruginosa PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR-MCS5). Hence, the combination of the two enzymes in P. aeruginosa seemed to be the key to the increased survival of infected C. elegans.

FIG 7.

Expression of both aqdC and qsdA increases survival of C. elegans under PAO1 exposure. Young adult C. elegans hermaphrodites were transferred onto NGM plates containing P. aeruginosa PAO1 strains, and survival was scored for four consecutive days. Black, P. aeruginosa PAO1(pME6032, pBBR1-MCS5) (empty vectors); green, PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR1-MCS5); red, PAO1(pME6032, pBBR::qsdA); blue, PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR::qsdA). As a negative control, the survival of C. elegans on E. coli OP50(pME::aqdC, pBBR::qsdA) lawns is depicted (gray). Data represent means ± SD from five plates with 10 worms each. Experiments were repeated three times. The survival rate of worms on PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR::qsdA) lawns was significantly higher (P < 0.05 by two-way ANOVA) than on PAO1(pME6032, pBBR1-MCS5) lawns in each biological replicate. Growth rates [OD600(t2) − OD600(t1)/t2 − t1] of recombinant P. aeruginosa PAO1 strains in LB medium (with appropriate antibiotics) at 22°C were as follows: 0.20 h−1 for PAO1(pME6032, pBBR1-MCS5), 0.15 h−1 for PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR1-MCS5), 0.19 h−1 for PAO1(pME6032, pBBR::qsdA), and 0.15 h−1 for PAO1(pME::aqdC, pBBR::qsdA).

DISCUSSION

The physiological role of enzymes catalyzing the cleavage of quorum sensing signal molecules is in most instances unknown. Microorganisms may have evolved such enzymes in order to gain access to carbon and nitrogen and to detoxify secondary metabolites acting as both signals and antibiotics, and they may use these enzymes to modulate the behavior of competitors. The PQS dioxygenase AqdC of M. abscessus subsp. abscessus is part of a PQS-inducible pathway that converts HHQ via PQS to octanoate and anthranilic acid (16), which can be funneled into central metabolic pathways. Thus, AqdC, besides a possible role in AQ detoxification, apparently acts as a catabolic enzyme. Additional biological functions of AqdC in M. abscessus subsp. abscessus cannot be excluded. PQS cleavage may be advantageous under certain conditions because PQS, an iron chelator, decreases iron availability (7, 30). Further investigations on interspecies interactions are needed to unravel whether aqd genes confer a fitness advantage in natural habitats or in clinical settings.

Enzymes inactivating quorum sensing signal molecules have been discussed to hold potential for application as antivirulence therapeutics. With quorum quenching enzymes targeting extracellular signals, it should be possible to reduce the virulence of pathogens and avoid rapid development of resistant strains. Especially for the treatment of pathogens like P. aeruginosa, which are resistant to a variety of antibiotics, quorum quenching agents are promising tools. However, successful and effective use of enzymes in clinical therapies requires stable proteins delivered efficiently at their place of action. The AHL acylase PvdQ, for example, was successfully processed to a freeze-dried powder, which can be inhaled and directly applied in the lung of patients suffering from CF (35). In the case of AqdC, an important challenge is to increase its stability, e.g., by enzyme engineering (36, 37).

While the majority of studies on enzyme-mediated interference with P. aeruginosa virulence report the effects of a single quorum quenching enzyme (12), we analyzed the effect of an AHL lactonase and a PQS dioxygenase on the production of several extracellular virulence factors both individually and in combination. Our data indicate that single quorum quenching enzymes, targeting individual circuits within a complex interconnected quorum sensing network, besides the desired attenuation of virulence factor production, may also elicit undesirable regulatory effects resulting in the overproduction of certain factors. Combining quorum quenching enzymes may minimize such undesired effects and may expand the spectrum of virulence factors that are quenched. Although encompassing a limited set of extracellular factors, our study suggests that quorum sensing interference in pathogenic bacteria that regulate their virulence factor production by interwoven quorum sensing circuits requires a combination of enzymes or antagonists targeting different circuits. Our study also substantiates that assessment of a quorum quenching agent for potential use as an antivirulence therapeutic requires a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the response of the pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

PQS, HHQ, and HQNO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions were prepared in methanol.

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. For construction of pET28b(+)::his8-qsdA, the qsdA gene was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4 (isolated with a genomic DNA isolation kit [Analytik Jena], according to manufacturer’s instructions) and cloned via the restriction-free cloning method into the pET28b(+) vector, additionally introducing the sequence for an N-terminal His8 tag (38).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s) or use | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | E. coli strain for heterologous expression of proteins | 52 |

| E. coli MG1655(pSB536) | Reporter strain for luciferase-mediated detection of BHL | 43 |

| E. coli DH5α(pSB1075) | Reporter strain for luciferase-mediated detection of 3oDHL | 44 |

| E. coli OP50 | Food source for C. elegans | 49 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | Wild type; Nottingham strain | Holloway collection |

| M. abscessus subsp. abscessus DSM44196 | Mycobacterial strain harboring aqd genes | DSMZ |

| M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a | Clinical isolate; lacks aqd genes | 16, 25 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET23a-hodC | Expression of His6-hodC in E. coli BL21(DE3) | 30 |

| pET22b-aqdC1 | Expression of His6-aqdC1 in E. coli BL21(DE3) | 15 |

| pET28b(+)::his8-aqdCI | Expression of His8-aqdC in E. coli BL21(DE3) | 16 |

| pET28b(+)::his8-qsdA | Expression of His8-qsdA in E. coli BL21(DE3) | This study |

| pHERD30T | Empty vector; confers gentamicin resistance to PAO1 | 53 |

| pJV53-gfp | Template plasmid for construction of pJV53-aqdC | 29 |

| pJV | Empty vector; confers gentamicin resistance to M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a | This study |

| pJV-aqdC | Expression of aqdC in M. abscessus subsp. massiliense P4a | This study |

| pBBR1-MCS5 | Empty vector control for C. elegans killing assays | 54 |

| pBBR1::qsdA | Heterologous expression of qsdA in P. aeruginosa PAO1 | This study |

| pME6032 | Empty vector control for C. elegans killing assay | 55 |

| pME::aqdC | Heterologous expression of aqdC in P. aeruginosa PAO1 | This study |

For the construction of pJV-aqdC, the gfp gene in pJV53-gfp (29) was exchanged with aqdC by using the NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly cloning kit (New England Biolabs), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with overlaps of 10 bp. In the same step, Chec9c genes were exchanged with a gentamicin resistance cassette. The resulting plasmid, pJV-aqdC, was digested with SpeI and religated in order to form the empty vector control plasmid pJV. Restriction was carried out with Fast Digest enzymes (Thermo Scientific), and ligation was performed with T4 ligase (Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For PCR amplification, Q5 HiFi polymerase (New England Biolabs) was used. All plasmids were confirmed via sequencing (GATC Biotech AG).

Heterologous production and purification of quorum quenching enzymes.

AqdC and QsdA were isolated from Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)(pET28b(+)::his8-aqdCI) and E. coli BL21(DE3)(pET28b(+)::his8-qsdA) as described previously by Birmes et al. (16) for AqdC. Cells were grown at 37°C in Terrific broth, supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 kanamycin, to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Next, the temperature was decreased to 16°C, and expression was induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 8) containing 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole, and disrupted by sonication. The enzymes were purified to electrophoretic homogeneity by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography and stored in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 8) with 10% (vol/vol) glycerol at −80°C. Recombinant His-tagged HodC and AqdC1 were purified as described previously (15, 30).

Enzyme assays.

The catalytic activity of AqdC, AqdC1, and HodC was measured in a continuous spectrophotometric assay at 30°C, following consumption of PQS or other 2-alkyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolones at 337 nm (16). The assay buffer used in this study (50 mM Tris, 2 mM EDTA, 10% polyethylene glycol 1500 [PEG 1500], 4% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] [pH 8]) differs from the one reported by Müller et al. (15) and further improved PQS solubility. The extinction coefficient of PQS and its congeners in the assay buffer is 10,169 M−1 cm−1. For determination of the relative QsdA activity toward the artificial substrate γ-butyrolactone, a pH-sensitive colorimetric assay (39) based on the color change of cresol purple was used as described previously by Khersonsky and Tawfik (40).

Cultivation of P. aeruginosa PAO1 in the presence of quorum quenching enzymes.

A culture of P. aeruginosa PAO1 grown overnight in LB medium was diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in 15 ml fresh medium and incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking. After 2 h of incubation, AqdC, QsdA, or the equivalent volume of buffer was added to the growing culture. Samples were taken 8 h and 24 h after enzyme addition for determination of AHLs, AQs, and virulence factors. For the preparation of P. aeruginosa supernatants for use in cytotoxicity assays, 10-ml cultures in LB medium, supplemented at an OD600 of 0.05 with either the quorum quenching enzyme(s) or enzyme buffer, were grown for 24 h at 37°C and centrifuged for 7 min at 5,000 rpm at room temperature (RT). The supernatant was passed twice through a 0.2-μm filter.

Coculture of P. aeruginosa and M. abscessus.

M. abscessus strains were grown for 70 h, and P. aeruginosa was grown overnight in 50 ml 30% LB medium at 37°C at 140 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 10 min), and cell pellets were resuspended in 30% LB medium. Cocultures were set up in triplicate in 15 ml 30% LB medium in 100-ml Erlenmeyer flasks. For inoculation, the OD600s of P. aeruginosa and M. abscessus were set to 0.05 and 0.15, respectively (41). Cocultures were incubated at 37°C at 140 rpm. Samples were analyzed for CFU, AQ concentrations, and virulence factors.

Determination of CFU.

For determination of CFU, 20-μl coculture samples were diluted in a decimal series in 180 μl 30% LB medium. Ten microliters of the appropriate dilutions was dropped in triplicate onto agar plates (42). LB plates were used for P. aeruginosa PAO1 and incubated overnight at 37°C. For selection of M. abscessus, DSM219 agar complemented with Mycobacteria Selectatab (Kirchner) (MS24) (Mast Diagnostica GmbH, Germany) was used, and the agar plates were incubated for 3 days at 37°C.

Determination of AQ levels.

AQ levels in P. aeruginosa cultures and cocultures were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Five-hundred-microliter culture samples were extracted three times with 500 μl ethyl acetate (acidified with 1 ml liter−1 acetic acid), dried to completion, and redissolved in 100 to 200 μl methanol. HPLC was performed with an Agilent 1100 series system or a Hitachi EZChrom Elite HPLC system on a 250- by 4-mm Eurospher II RP-18 column at 35°C, using a linear gradient (within 40 min) from 60% methanol in water with 0.1% (wt/vol) citric acid to 100% methanol with 0.1% (wt/vol) citric acid at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. Light absorption spectra of eluted compounds were recorded with a diode array detector (model G1315B [Agilent] or L-2450 LaChrome Elite [Merck Hitachi]). For calibration, PQS, HHQ, and HQNO were used as reference compounds.

Determination of AHL levels.

AHL levels in P. aeruginosa cultures and cocultures were determined using E. coli(pSB536) and E. coli(pSB1075) as reporter strains for BHL and 3oDHL, respectively (43, 44). To this end, 100-μl samples taken from the P. aeruginosa cultures or cocultures were centrifuged, and the supernatant was extracted twice with acidified ethyl acetate and dried to completion. E. coli bioreporter strains were grown overnight in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg ampicillin ml−1 at 37°C. Cells of the respective bioreporter strains were inoculated into fresh medium at an OD600 of 0.2, 175 μl of the cell suspension was pipetted into each well of a 96-well plate, and the reconstituted extract (25 μl) was added. The microtiter plates were incubated at 37°C under shaking in a Glomax luminometer (Promega), and the luminescence and OD600 were recorded after 2 h of incubation.

Quantification of virulence factors.

Pyoverdin contents in culture supernatants were determined by measuring the absorption at 405 nm (45). Pyocyanin levels were determined spectrophotometrically after extraction with chloroform (46). Rhamnolipids were detected by using the orcinol method (47). The activity of elastase in culture supernatants was analyzed with the elastin Congo red assay (48).

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-PCR.

For isolation of RNA, P. aeruginosa PAO1 was grown in the presence and absence of AqdC, QsdA, or both enzymes in LB medium at 37°C. After 8 and 24 h of incubation, cells were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Cells were resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8]) with 1 μl Ribolock RNase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific) and disrupted in a Micro-Dismembrator S instrument (Sartorius) at 3,000 rpm for 2 min in the presence of glass beads. RNA isolation was performed using the innuPREP RNA minikit (Analytik Jena) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Contaminating DNA was removed by treatment with DNase I (Thermo Scientific) for 3 h at 37°C. After renewed purification, the RNA was checked for residual DNA via PCR (GoTaq polymerase; Promega). RNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically with an N60 nanophotometer (Implen).

RT-qPCR was performed for relative quantification of transcription of single genes. Primers were designed to amplify regions of approximately 100 bp (for sequences, see Table 2). The Luna universal one-step RT-qPCR kit (New England Biolabs) was used on a StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), with each reaction mixture containing 1 μl 150 ng μl−1 RNA as the template. All measurements were carried out in three biological replicates, each in technical duplicates. Reverse transcription was performed at 50°C for 10 min, and initial denaturation and polymerase activation were carried out at 95°C for 1 min, followed by a two-step amplification (95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s, for 40 cycles) and a melting-curve analysis. For data evaluation, the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method was applied using StepOne software v2.0, and the relative transcript amount was normalized to the rpoS internal control gene.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for RT-qPCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Application |

|---|---|---|

| rpoS-for | CTCCCCGGGCAACTCCAAAAG | RT-qPCR of internal control gene rpoS |

| rpoS-rev | CGATCATCCGCTTCCGACCAG | |

| pqsA-for | GTTTCTGGTTCCTACCTGCC | RT-qPCR of pqsA |

| pqsA-rev | CAGCAGGATCTGGTTGTCGT | |

| pqsE-for | GGTTGAAGGAGGGATCAGCC | RT-qPCR of pqsE |

| pqsE-rev | AGTGGTCGTAGTGCTTGTGG | |

| pqsR-for | GATAGCCTGGCGACGATCAA | RT-qPCR of pqsR |

| pqsR-rev | CACTGGTTGAAGCGGGAGAT | |

| lasI-for | CAGAACGACATCCAGACGCT | RT-qPCR of lasI |

| lasI-rev | TCGATGCCGATCTTCAGGTG | |

| lasR-for | AGATCCTGTTCGGCCTGTTG | RT-qPCR of lasR |

| lasR-rev | GGGTAGTTGCCGACGATGAA | |

| rhlI-for | CAGTTCGACCATCCGCAAAC | RT-qPCR of rhlI |

| rhlI-rev | GACGTCCTTGAGCAGGTAGG | |

| rhlR-for | GTTTGCGTAGCGAGATGCAG | RT-qPCR of rhlR |

| rhlR-rev | GGCGTAGTAATCGAAGCCCA | |

LDH release from airway epithelial cells.

The cytotoxicity of P. aeruginosa culture supernatants was examined by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from a human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line, A549, using the CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega). Epithelial cells were cultured and maintained in flat culture flasks in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) containing fetal bovine serum (FBS) and NaHCO3 at 37°C with 5% CO2. For the assay, confluent cells were seeded in a 12-well tissue culture plate and incubated for 3 days. On the third day, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), covered with 500 μl RPMI 1640 containing NaHCO3 and 10 mg/ml human serum albumin (HSA), and supplemented with 500 μl of the P. aeruginosa supernatant. After 4 h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, 400 μl of the supernatant of each well was transferred to a tube and centrifuged for 5 min at 5,000 rpm at RT to remove cell debris. Fifty microliters of each sample was transferred into a 96-well plate, and LDH release was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacterial cultivation medium with additional enzyme buffer was used as negative control (live epithelial cells), and 0.9% Triton X-100 was used as a positive control (100% dead epithelial cells). Triton was added 30 min before ending the incubation. Each supernatant was tested in technical duplicates and biological triplicates.

Analysis of cell viability by propidium iodide staining.

To determine the cytotoxic effect of P. aeruginosa supernatants on human airway epithelial cells, a flow cytometric assay was additionally performed. A549 cells were cultured, seeded in a 12-well tissue culture plate, and covered with P. aeruginosa supernatants as described above for the LDH release assay. The same positive and negative controls were used. After 4 h of incubation with the bacterial supernatant, cell medium as well as PBS, used for washing, were transferred to a FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorter) tube. The remaining adhesive cells were detached with trypsin and transferred into the same FACS tube. After centrifugation at 1,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min, the supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl PBS supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 PI to stain the DNA of nonviable cells with damaged, permeable cell membranes. Subsequently, samples were analyzed with the BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer by counting a maximum of 5,000 events, applying a fast flow. Data were evaluated with BD Accuri C6 software. Each supernatant was tested in technical duplicates and at least as biological triplicates.

C. elegans killing assay.

C. elegans Bristol N2 worms were cultured under standard conditions on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates with E. coli OP50 as a food source (49). Synchronization of worms was performed by alkaline hypochlorite bleaching (40% sodium hypochlorite, 5% NaOH) as described previously by Lewis and Fleming (50). For C. elegans killing assays, P. aeruginosa strains and E. coli OP50(pME::aqdC, pBBR::qsdA) were cultivated in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin and 125 μg ml−1 tetracycline or 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin and 12.5 μg ml−1 tetracycline, respectively. Cultivation was carried out overnight at 37°C under vigorous shaking. Ten microliters of the cell suspension was dropped onto an agar plate (3.5-cm diameter) containing PGS medium (1% Bacto peptone, 1% NaCl, 1% glucose, 0.15 M sorbitol, 1.7% Bacto agar) supplemented with appropriate concentrations of gentamicin and tetracycline, as described previously by Tan et al. (51). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h to form a bacterial lawn. Ten C. elegans hermaphrodites were put on each plate and incubated further at room temperature (21°C to 23°C). Worm mortality was observed over time, and a worm was considered dead when it failed to respond to touch. Supply of nutrients was ensured during the incubation of the worms, as the bacterial lawn was not fully consumed after 4 days.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant no. FE 383/25-1 to S.F. and grant no. SFTR34/C7 to B.C.K.). F.S.B. thanks the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes for funding and support.

We gratefully acknowledge Yi-Cheng Sun (Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College) for providing pJV53-gfp, Almut Kappius for technical assistance, and Selene F. Hess for assistance with cloning of qsdA and virulence assays.

S.F. and F.S.B. conceived the study. R.S. performed coculture experiments. M.C.H. and J.T. determined cytotoxic effects on human epithelial lung cells. J.D. and F.S.B. conducted experiments with C. elegans. N.H.R. performed growth experiments. F.S.B., S.L.D., B.C.K., J.D., and E.L. analyzed data. S.L.D. performed statistics and designed figures. S.F. wrote the manuscript text. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. 2017. Annual data report 2016. Cystic fibrosis foundation patient registry. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuster M, Greenberg EP. 2006. A network of networks: quorum-sensing gene regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Med Microbiol 296:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huse H, Whiteley M. 2011. 4-Quinolones: smart phones of the microbial world. Chem Rev 111:152–159. doi: 10.1021/cr100063u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heeb S, Fletcher MP, Chhabra SR, Diggle SP, Williams P, Cámara M. 2011. Quinolones: from antibiotics to autoinducers. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35:247–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papenfort K, Bassler BL. 2016. Quorum sensing signal-response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:576–588. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Déziel E, Gopalan S, Tampakaki AP, Lépine F, Padfield KE, Saucier M, Xiao G, Rahme LG. 2005. The contribution of MvfR to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and quorum sensing circuitry regulation: multiple quorum sensing-regulated genes are modulated without affecting IasRI, rhIRI or the production of N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones. Mol Microbiol 55:998–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin J, Cheng J, Wang Y, Shen X. 2018. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS): not just for quorum sensing anymore. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:230. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mashburn LM, Whiteley M. 2005. Membrane vesicles traffic signals and facilitate group activities in a prokaryote. Nature 437:422–425. doi: 10.1038/nature03925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Häussler S, Becker T. 2008. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) balances life and death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000166. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reen FJ, Mooij MJ, Holcombe LJ, McSweeney CM, McGlacken GP, Morrissey JP, O’Gara F. 2011. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS), and its precursor HHQ, modulate interspecies and interkingdom behaviour. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 77:413–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Seyedsayamdost MR. 2017. Synergy and target promiscuity drive structural divergence in bacterial alkylquinolone biosynthesis. Cell Chem Biol 24:1437–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fetzner S. 2015. Quorum quenching enzymes. J Biotechnol 201:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pustelny C, Albers A, Büldt-Karentzopoulos K, Parschat K, Chhabra SR, Cámara M, Williams P, Fetzner S. 2009. Dioxygenase-mediated quenching of quinolone-dependent quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem Biol 16:1259–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller C, Birmes FS, Niewerth H, Fetzner S. 2014. Conversion of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quinolone signal and related alkylhydroxyquinolines by Rhodococcus sp. strain BG43. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:7266–7274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02342-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller C, Birmes FS, Rückert C, Kalinowski J, Fetzner S. 2015. Rhodococcus erythropolis BG43 genes mediating Pseudomonas aeruginosa quinolone signal degradation and virulence factor attenuation. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:7720–7729. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02145-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birmes FS, Wolf T, Kohl TA, Rüger K, Bange F, Kalinowski J, Fetzner S. 2017. Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus is capable of degrading Pseudomonas aeruginosa quinolone signals. Front Microbiol 8:339. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Rodriguez-Rincon D, Everall I, Brown KP, Moreno P, Verma D, Hill E, Drijkoningen J, Gilligan P, Esther CR, Noone PG, Giddings O, Bell SC, Thomson R, Wainwright CE, Coulter C, Pandey S, Wood ME, Stockwell RE, Ramsay KA, Sherrard LJ, Kidd TJ, Jabbour N, Johnson GR, Knibbs LD, Morawska L, Sly PD, Jones A, Bilton D, Laurenson I, Ruddy M, Bourke S, Bowler ICJW, Chapman SJ, Clayton A, Cullen M, Daniels T, Dempsey O, Denton M, Desai M, Drew RJ, Edenborough F, Evans J, Folb J, Humphrey H, Isalska B, Jensen-Fangel S, Jönsson B, Jones AM, et al. 2016. Emergence and spread of a human-transmissible multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacterium. Science 354:751–757. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor JL, Palmer SM. 2006. Mycobacterium abscessus chest wall and pulmonary infection in a cystic fibrosis lung transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant 25:985–988. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy I, Grisaru-Soen G, Lerner-Geva L, Kerem E, Blau H, Bentur L, Aviram M, Rivlin J, Picard E, Lavy A, Yahav Y, Rahav G. 2008. Multicenter cross-sectional study of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections among cystic fibrosis patients, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis 14:378–384. doi: 10.3201/eid1403.061405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binder AM, Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Prevots DR. 2013. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections and associated chronic macrolide use among persons with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:807–812. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1200OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viviani L, Harrison MJ, Zolin A, Haworth CS, Floto RA. 2016. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) amongst individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF). J Cyst Fibros 15:619–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. 2009. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 373:1891–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raidt L, Idelevich E, Dubbers A, Kuster P, Drevinek P, Peters G, Kahl B. 2015. Increased prevalence and resistance of important pathogens recovered from respiratory specimens of cystic fibrosis patients during a decade. Pediatr Infect Dis J 34:700–705. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barr HL, Halliday N, Cámara M, Barrett DA, Williams P, Forrester DL, Simms R, Smyth AR, Honeybourne D, Whitehouse JL, Nash EF, Dewar J, Clayton A, Knox AJ, Fogarty AW. 2015. Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing molecules correlate with clinical status in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 46:1046–1054. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00225214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rüger K, Hampel A, Billig S, Rücker N, Suerbaum S, Bange FC. 2014. Characterization of rough and smooth morphotypes of Mycobacterium abscessus isolates from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 52:244–250. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01249-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uroz S, Oger PM, Chapelle E, Adeline MT, Faure D, Dessaux Y. 2008. A Rhodococcus qsdA-encoded enzyme defines a novel class of large-spectrum quorum-quenching lactonases. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1357–1366. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02014-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afriat L, Roodveldt C, Manco G, Tawfik DS. 2006. The latent promiscuity of newly identified microbial lactonases is linked to a recently diverged phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry 45:13677–13686. doi: 10.1021/bi061268r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh HS, Kim SR, Cheong WS, Lee CH, Lee JK. 2013. Biofouling inhibition in MBR by Rhodococcus sp. BH4 isolated from real MBR plant. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:10223–10231. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4933-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao X-J, Yan M-Y, Zhu H, Guo X-P, Sun Y-C. 2016. Efficient and simple generation of multiple unmarked gene deletions in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Sci Rep 6:22922. doi: 10.1038/srep22922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tettmann B, Niewerth C, Kirschhöfer F, Neidig A, Dötsch A, Brenner-Weiss G, Fetzner S, Overhage J. 2016. Enzyme-mediated quenching of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) promotes biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by increasing iron availability. Front Microbiol 7:1978. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wade DS, Calfee MW, Rocha ER, Ling EA, Engstrom E, Coleman JP, Pesci EC. 2005. Regulation of Pseudomonas quinolone signal synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 187:4372–4380. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4372-4380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maura D, Hazan R, Kitao T, Ballok AE, Rahme LG. 2016. Evidence for direct control of virulence and defense gene circuits by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing regulator, MvfR. Sci Rep 6:34083. doi: 10.1038/srep34083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rampioni G, Pustelny C, Fletcher MP, Wright VJ, Bruce M, Rumbaugh KP, Heeb S, Camara M, Williams P. 2010. Transcriptomic analysis reveals a global alkyl-quinolone-independent regulatory role for PqsE in facilitating the environmental adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to plant and animal hosts. Environ Microbiol 12:1659–1673. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrow JM III, Sund ZM, Ellison ML, Wade DS, Coleman JP, Pesci EC. 2008. PqsE functions independently of PqsR-Pseudomonas quinolone signal and enhances the rhl quorum-sensing system. J Bacteriol 190:7043–7051. doi: 10.1128/JB.00753-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wahjudi M, Murugappan S, Van Merkerk R, Eissens AC, Visser MR, Hinrichs WLJ, Quax WJ. 2013. Development of a dry, stable and inhalable acyl-homoserine-lactone-acylase powder formulation for the treatment of pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Eur J Pharm Sci 48:637–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wijma HJ, Floor RJ, Jekel PA, Baker D, Marrink SJ, Janssen DB. 2014. Computationally designed libraries for rapid enzyme stabilization. Protein Eng Des Sel 27:49–58. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzt061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Floor RJ, Wijma HJ, Colpa DI, Ramos-Silva A, Jekel PA, Szymański W, Feringa BL, Marrink SJ, Janssen DB. 2014. Computational library design for increasing haloalkane dehalogenase stability. Chembiochem 15:1660–1672. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Den Ent F, Löwe J. 2006. RF cloning: a restriction-free method for inserting target genes into plasmids. J Biochem Biophys Methods 67:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman E, Wong CH. 2002. A pH sensitive colorometric assay for the high-throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors and substrates: a case study using kinases. Bioorg Med Chem 10:551–555. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(01)00306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS. 2005. Structure-reactivity studies of serum paraoxonase PON1 suggest that its native activity is lactonase. Biochemistry 44:6371–6382. doi: 10.1021/bi047440d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa KC, Bergkessel M, Saunders S, Korlach J, Newman DK. 2015. Enzymatic degradation of phenazines can generate energy and protect sensitive organisms from toxicity. mBio 6:e01520-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01520-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoben HJ, Somasegaran P. 1982. Comparison of the pour, spread, and drop plate methods for enumeration of Rhizobium spp. in inoculants made from presterilized peat. Appl Environ Microbiol 44:1246–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swift S, Karlyshev AV, Fish L, Durant EL, Winson MK, Chhabra SR, Williams P, Macintyre S, Stewart GSAB. 1997. Quorum sensing in Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas salmonicida: identification of the LuxRI homologs AhyRI and AsaRI and their cognate N-acylhomoserine lactone signal molecules. J Bacteriol 179:5271–5281. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5271-5281.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winson MK, Swift S, Fish L, Throup JP, Jørgensen F, Chhabra SR, Bycroft BW, Williams P, Stewart GSAB. 1998. Construction and analysis of luxCDABE-based plasmid sensors for investigating N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing. FEMS Microbiol Lett 163:185–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stintzi A, Cornelis P, Hohnadel D, Meyer JM, Dean C, Poole K, Kourambas S, Krishnapillai V. 1996. Novel pyoverdine biosynthesis gene(s) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Microbiology 142:1181–1190. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Essar DW, Eberly L, Hadero A, Crawford IP. 1990. Identification and characterization of genes for a 2nd anthranilate synthase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interchangeability of the 2 anthranilate synthases and evolutionary implications. J Bacteriol 172:884–900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.884-900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilhelm S, Gdynia A, Tielen P, Rosenau F, Jaeger KE. 2007. The autotransporter esterase EstA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is required for rhamnolipid production, cell motility, and biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 189:6695–6703. doi: 10.1128/JB.00023-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toder DS, Gambello MJ, Iglewski BH. 1991. Pseudomonas aeruginosa LasA: a second elastase under the transcriptional control of lasR. Mol Microbiol 5:2003–2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brenner S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis J, Fleming J. 1995. Basic culture methods. Methods Cell Biol 48:3–29. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61381-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan M-W, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM. 1999. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:715–720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Studier FW, Moffatt BA. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol 189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu D, Damron FH, Mima T, Schweizer HP, Yu HD. 2008. PBAD-based shuttle vectors for functional analysis of toxic and highly regulated genes in Pseudomonas and Burkholderia spp. and other bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7422–7426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01369-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad host range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heeb S, Itoh Y, Nishijyo T, Schnider U, Keel C, Wade J, Walsh U, O’Gara F, Haas D. 2000. Small, stable shuttle vectors based on the minimal pVS1 replicon for use in gram-negative, plant-associated bacteria. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:232–237. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]