Summary

Background

The off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) technique, which is used in order to avoid the side effects of cardiopulmonary bypass, is often questioned in terms of its efficacy and safety. Also, in this technique, surgeon experience plays a very important role. In this study, we share the results of our 606 OPCAB cases with an alternative retraction technique.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of OPCAB operations performed between January 2014 and December 2018. Patients were evaluated and operated on by a surgical team led by an experienced OPCAB surgeon with over 200 prior OPCAB surgeries.

Results

The study included 606 OPCAB cases, and 21.8% (132) were female and 78.2% (474) were male. Our mortality rate was 1.7% (n = 10) and only two patients suffered a cerebrovascular incident. A statistically significant difference was found between pre-operative and six-month postoperative left ventricular ejection fraction values (p < 0.01).

Conclusion

The OPCAB technique can be performed with similar results to on-pump surgery when conducted by an experienced surgeon, as in our study.

Keywords: on-pump coronary artery bypass, alternative method

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) is a treatment that improves survival in advanced coronary artery disease. The off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) technique, which is used in order to avoid the side effects of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), is often questioned in terms of its efficacy and safety. Although there are over 100 randomised controlled trials and 60 meta-analyses, the superiority of one technique over the other has not been clearly demonstrated.1 While some studies did not show any difference between the two techniques,2,3 one study showed that OPCAB resulted in decreased mortality and morbidity rates and hospitalisation time.4

In these studies, another important criterion in determining the effectiveness of OPCAB was the case volume of the institution and the surgeon. In a study by Benedetto et al.,5 five-year follow-up results of 1 260 OPCAB and 1 700 on-pump coronary artery bypass (ONCAB) operations were published. The experience of the surgeons who performed the cases was also evaluated. Surgeons performing sporadic (one to five cases) OPCAB operations had a high conversion rate, low graft count and high mortality rate. OPCAB results of high-volume surgeons were found to be similar to ONCAB surgery.

In our centre, CABG operations are routinely performed by a single team using the off-pump technique. In this study, we share the results of our 606 OPCAB cases and the alternative technique we used for retraction and positioning of the heart.

Methods

This descriptive study is a retrospective analysis of OPCAB operations performed between January 2014 and December 2018. For all patients the OPCAB technique was routinely chosen, and there were no exclusion criteria. Patients were evaluated and operated on by a surgical team led by an experienced OPCAB surgeon (over 200 prior OPCAB surgeries).

All patients were sedated with 2 mg IV midazolam and anaesthesia induction was done with fentanyl 10 μg/kg, midazolam 0.1 mg/kg and rocuronium 1 mg/kg. In order to prevent possible cardiac oedema during the positioning of the heart, 1 mg/kg methylprednisolone was routinely given to all of our patients as well as pheniramine IV in order to prevent possible reactions during protamine administration. Following 100–200 IU/kg heparinisation, the activated clotting time (ACT) was kept between 200 and 400 seconds. In order to benefit from its anti-arrhythmic effects, 1 mg/kg lidocaine 2.5% IV and 10 ml 15% magnesium sulfate were administered during internal thoracic artery harvest. Potassium levels were closely monitored and kept above 4.0 mEq/ml.

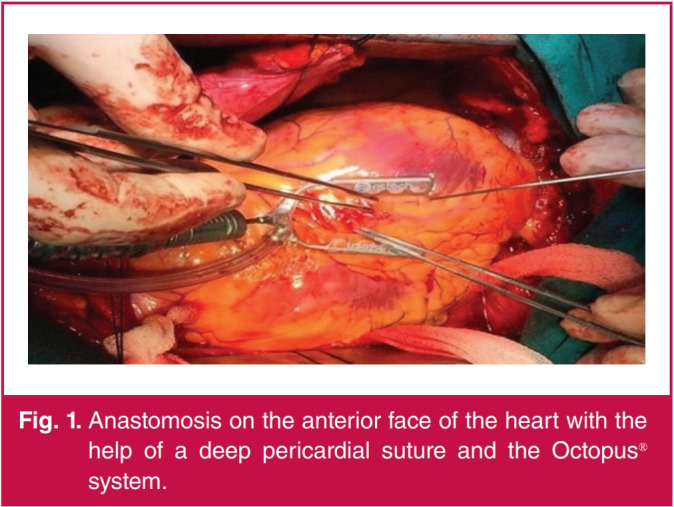

After left internal mammary artery (LIMA) harvesting, the pericardium was opened and a deep pericardial suture was placed to elevate the heart. The right pleura was opened in all patients if the circumflex (Cx) coronary artery and its branches were targeted for bypass, thereby preventing haemodynamic deterioration during retraction of the heart. In addition, moistened gauzes were placed through transfer and oblique sinuses. With the placement of these gauzes, the heart could be retracted more efficiently. The retraction gauzes were used to hold the heart until the anastomosis area was determined, as if the operation was done with CPB, and thereafter, the tissue stabilisation system (OctopusR Evolution, Medtronic) was used. During anastomosis of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery to the LIMA, the gauzes were loosened in order to avoid too much compression of the heart and further haemodynamic disturbances, but we still had enough tension to retract the heart and support the stabilisation system. Anastomoses were thus done with direct access and without excess manipulation of the heart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Anastomosis on the anterior face of the heart with the help of a deep pericardial suture and the Octopus® system.

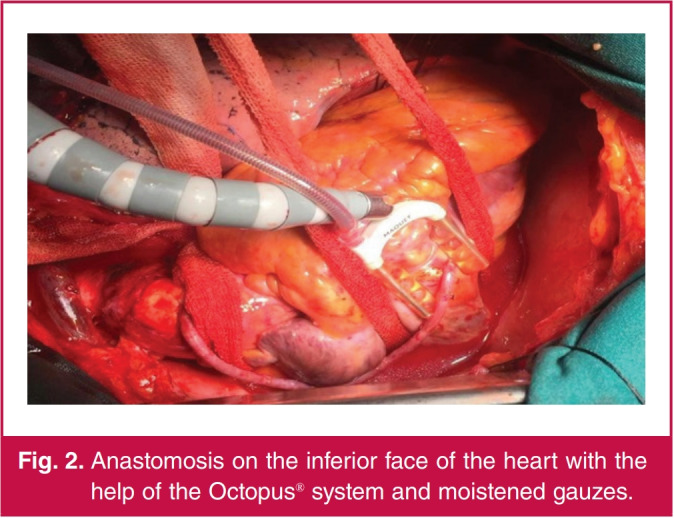

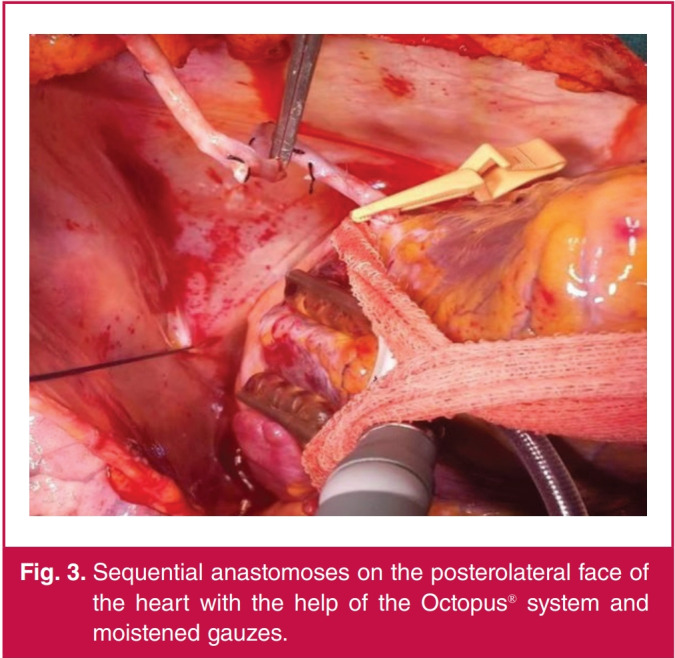

During right coronary artery (RCA) anastomosis, the operating table was positioned away from the surgeon and the anastomosis was perfomed with gauzes and the suction system was used to create a more stable state (Fig. 2). When doing bypasses to the circumflex branches [obtuse marginal (OM) or posterolateral (PL) arteries], the operating table was positioned at 20 degrees Trendelenburg and turned to the right side. No apical holder was used in any patient. During anastomosis on the posterolateral surface, the heart was retracted more firmly to the right side with gauzes and the suction system (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Anastomosis on the inferior face of the heart with the help of the Octopus® system and moistened gauzes.

Fig. 3.

Sequential anastomoses on the posterolateral face of the heart with the help of the Octopus® system and moistened gauzes.

All distal anastomoses were performed using intracoronary shunt, except for total occlusion. After completion of the anastomoses, 50–100 IU/kg protamine (half dose) was administered and the operation was terminated.

The patients were ventilated with high frequency and low tidal volume (350–400 ml) to prevent movement during anastomosis. Tidal volume was increased when there was a problem with saturation in the arterial blood gas values. No patient had an oxygenation problem during the operation.

The patients were monitored and followed closely in the intensive care unit. Low-molecular-weight heparin was given to all patients for four to six hours postoperatively.

In this study, haemodynamic instability, ventricular fibrillation and anastomotic difficulty were the main criteria for conversion to on-pump surgery.

Statistical analysis

SPSS statistics for Windows version 22.0 (SPSS Inc Chicago, IL, USA; released 2008) was used for statistical analysis. The pairedsamples t-test was used to compare repeated measurements. Since there was only one group of patients, descriptive studies were chosen; p-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The study included 606 OPCAB cases performed in a single centre between January 2014 and December 2018, and 21.8% (132) of our patients were female and 78.2% (474) were male. The mean age was 62.25 ± 9.47 (min–max 32–86 years) years. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of our patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Variables | n (%) or mean ± SD |

| Female | 132 (21.8) |

| Male | 474 (78.2) |

| Age (years) | 62.25 ± 9.47 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.58 ± 4.98 |

| Recent myocardial infarction | |

| Yes | 362 (59.7) |

| No | 244 (40.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Yes | 329 (54.3) |

| No | 277 (45.7) |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 323 (53.3) |

| No | 283 (46.7) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Yes | 398 (65.7) |

| No | 208 (34.3) |

| Smoking history | |

| Yes | 323 (53.3) |

| No | 283 (46.7) |

| Renal disease | |

| No renal disease | 580 (95.7) |

| Dialysis dependent | 6 (1) |

| Creatinine > 2.3 mg/dl | 20 (3.3) |

| Ejection fraction | |

| < 35% | 61 (10.1) |

| 35–50% | 285 (47.0) |

| > 50% | 260 (42.9) |

When cardiac function was examined, it was seen that 10.1% (n = 61) of our patients had low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). In these patients, excessive volume overload was avoided in the peri- and postoperative period. Postoperative findings are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Poscentererative findings.

| Variables | Mean (min–max) or n (%) |

| Intubation (hours) | 6.31 (1–240) |

| ICU stay (days) | 1.22 (0.04–18.75) |

| Hospital stay (days) | 5.62 (3–48) |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | |

| Yes | 29 (4.8) |

| No | 577 (95.2) |

| Inotropes | |

| None | 489 (80.7) |

| Dopamine | 84 (13.9) |

| Dopamine + noradrenaline | 33 (5.4) |

| Drainage (ml), mean | ± SD 683.58 ± 193.52 |

| Revision | |

| Yes | 5 (0.8) |

| No | 601 (99.2) |

| Poscentererative atrial fibrillation | |

| Yes | 36 (5.9) |

| No | 570 (94.1) |

| Cerebrovascular incident | |

| Yes | 2 (0.3) |

| No | 604 (99.7) |

In routine practice in our clinic, when starting inotropic support, dopamine and noradrenaline infusion are the first choice. More than two inotropic supports were not used in our study. The mortality rate was 1.7% (n = 10) in 606 cases and only two patients suffered a cerebrovascular incident (CVI). These patients recovered without neurological sequelae. Two patients (0.3%) were converted to on-pump surgery because of ECG changes (ST elevation) and were haemodynamically affected despite interventions. No additional morbidity and mortality was observed in these patients.

The number of distal anastomoses in our study is shown in Table 3. In Table 4, our six-month postoperative LVEF results can be seen. With 10 mortalities among our cases, we compared 596 patients. The paired-samples t-test was performed between these two groups and a statistically significant difference was found (p < 0.01).

Table 3. Number of distal anastomosis.

| Number of vessels | n (%) |

| 1 vessel | 48 (7.9) |

| 2 vessels | 232 (38.3) |

| 3 vessels | 223 (36.8) |

| 4 or more vessels | 103 (17.0) |

Table 4. Results of pre- and six-month poscentererative LVEF comparison.

| Paired-samples statistics | ||

| Variable | Mean (n) | SD |

| Pre-operative | 50.43 (593) | 9.36 |

| Poscentererative | 51.01 (593) | 8.67 |

*p < 0.01.

Discussion

In the treatment of coronary artery disease, which is one of the major causes of death worldwide, CABG surgery plays an important role. CABG surgeries are often performed with CPB and most of the time this technique is the major part of residency training.6 CPB provides great support to the surgeon during distal anastomoses and in the positioning of the heart. Performing an anastomosis on the beating heart is one of the biggest drawbacks in the OPCAB approach. However, OPCAB is an important surgical technique that can be used for prevention of the side effects of cannulation and CPB.7

Although there are more than 100 randomised studies and 60 meta-analyses in which comparison of these two techniques were made, there was no clear superiority of one technique over the other. However the experience of the surgeon was emphasised in all reports.1 When chosen routinely, OPCAB surgery can be as effective as on-pump bypass surgery.8 In meta-analyses of randomised studies, one to two years’ follow up of low-risk patients showed similar mortality rates, myocardial infarction and need for repeat revascularisation to on-pump surgery.9,10 Experience of the surgeons participating in the studies increased the success of OPCAB and no significant difference was found between the patients operated with on- and off-pump techniques.5,11 The impact of the surgeon’s experience in OPCAB success was most strikingly demonstrated in the ROOBY study.12 The five-year follow up of patients showed a clear superiority of ONCAB over OPCAB (operated on by a minimum of 20 experienced OPCAB surgeons). In the light of these studies and with our dedicated surgical team led by an experienced OPCAB surgeon, OPCAB surgery has became our routine choice for CABG operations.

In Table 2, the morbidities experienced in the postoperative period are shown. We compared our postoperative atrial fibrillation, intra-operative balloon pump (IABP) insertion, cerebrovascular events and postoperative revision numbers with those of the study by Taggart et al.13 with 618 patients in the OPCAB single mammary artery group, and those of the study by Benedetto et al.5 While the number of patients with IABP was similar, the number of cerebrovascular events and revisions was fewer in our study.

One of the major advantages of the OPCAB technique compared to ONCAB is the reduced manipulation of large vessels. During cannulation, embolisation of atheromatous plaque from the aorta, bleeding, iatrogenic dissection and end-organ malperfusion may develop. In addition, crossclamping can cause injury to the aorta, which can be avoided with the OPCAB technique. However, the risk of CVI is not reduced in OPCAB. The main reason for this is the side-clamp that is placed during proximal anastomosis. To avoid this, proximal anastomosis devices were developed, but the patency of these grafts was found to be decreased.7

The 2018 European Society of Cardiology guideline for myocardial revascularisation recommends OPCAB by experienced operators and preferably no-touch techniques on the ascending aorta.14 In our study, although we used lateral clamps during proximal anastomosis, CVI was seen in only two patients (0.3%).

We speculate that palpation of the aorta and avoiding any palpable plaques before clamp positioning contributed to this result. In their study, Mack et al.15 initially selected patients for OPCAB surgery who required three or fewer bypasses to the anterior surface of the heart. In the case of unstable patients, re-operations, and the need for bypass to the coronary arteries on the lateral side of the heart, the on-pump technique was preferred. However, as surgical experience increased and stabilisation techniques developed, OPCAB was preferred for all patients. Gauzes, sponges, traction sutures and stabilisation systems are combined to achieve good exploration of the target vessels.16-18 In our study, with high surgical experience and the support of an alternative retraction method, the anastomoses are performed in a more stable state without haemodynamic impairment. Thus anastomoses could easily be performed to the coronary arteries, especially on the posterior and posterolateral (Cx and RCA field) areas of the heart, and our success rate in revascularising the target vessels increased.

The LVEF, evaluated by two-dimensional echocardiography pre-operatively and at six months after surgery, was analysed in 596 patients and statistically analysed. These data show a statistically significant improvement in LVEF, particularly at six months after surgery. Capuani et al.19 showed a similar result with the comparison of pre- and postoperative LVEF.

In their study, Benedetto et al.5 showed conversion rates around 10%, and this outcome negatively affected five-year follow up. In the same study, the rate of conversion was 12.9% by OPCAB surgeons doing sporadic surgery (one to five cases) and 1.0% by experienced surgeons (> 60 cases). In their study, Angelini et al.20 emphasised that OPCAB results, performed by experienced surgeons who adopted all aspects of the OPCAB technique, were similar to on-pump surgery results. The low conversion rate in our study was attributed to the alternative method of retraction we used and the greater OPCAB experience of the surgeon. In addition, the conversion decision in these cases was done in a timely manner, therefore there was no morbidity or mortality in these patients (data not shown).

Although the ROOBY study showed that OPCAB was associated with increased mortality rates, many other studies do not mention increased mortality rates associated with OPCAB.7 Kowalewski et al.21 found a mortality rate of 2.04% with no significant difference between the two techniques. Our mortality rate was 1.7% (n = 10), which is similar to the mortality rates of OPCAB surgeries in the literature.

Since only the OPCAB technique is preferred in our centre, this study is presented as a descriptive one.

Conclusion

The OPCAB technique can be performed with similar results to on-pump surgery when performed by experienced surgeons, as in our study. The alternative retraction technique in conjunction with a stabiliser enables good exposure and stability in OPCAB surgery and contributes to the quality of coronary anastomoses, especially of the circumflex and right territory arteries.

References

- 1.Farina P, Gaudino M, Angelini GD. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: The long and winding road. Int J Cardiol. 2019;279:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parolari A, Alamanni F, Cannata A. et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass: Meta-analysis of currently available randomized trials. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afilalo J, Rasti M, Ohayon SM, Shimony A, Eisenberg MJ.. Off-pump vs. On-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: An updated meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2011;33(10):1257–1267. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reston JT, Tregear SJ, Turkelson CM.. Meta-analysis of short-term and mid-term outcomes following off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(5):1510–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedetto U, Altman DG, Gerry S. et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: Insights from the arterial revascularization trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155(4):1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.10.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murzi M, Caputo M, Aresu G, Duggan S, Angelini GD. Training residents in off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: A 14-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(6):1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaefi S, Mittel A, Loberman D, Ramakrishna H. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting – a systematic review and analysis of clinical outcomes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33(1):232–244. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel NN, Angelini GD. Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: For the many or the few? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140(5):951–953. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng Z-Z, Shi J, Zhao X-W, Xu Z-F. Meta-analysis of on-pump and off-pump coronary arterial revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(3):757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller CH, Penninga L, Wetterslev J, Steinbruchel DA, Gluud CJE. Clinical outcomes in randomized trials of off- vs. on-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: Systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(21):2601–2616. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamy A, Devereaux P, Prabhakaran D. et al. Five-year outcomes after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. New Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2359–2368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B. et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1827–1837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taggart DP, Altman DG, Gray AM. et al. Effects of on-pump and offpump surgery in the arterial revascularization trial. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2014;47(6):1059–1065. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A. et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2018;40(2):87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack M, Bachand D, Acuff T. et al. Improved outcomes in coronary artery bypass grafting with beating-heart techniques. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124(3):598–607. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.124884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watters MPR, Ascione R, Ryder IG, Ciulli F, Pitsis AA, Angelini GD. Haemodynamic changes during beating heart coronary surgery with the ‘Bristol technique’. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2001;19(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartier R, Brann S, Dagenais F, Martineau R, Couturier A. Systematic off-pump coronary artery revascularization in multivessel disease: Experience of three hundred cases . J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119(2):221–229. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergsland J, Schmid S, Yanulevich J, Hasnain S, Lajos T, Salerno T. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) without cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB): A strategy for improving results in surgical revascularization. Heart Surg Forum. 1998:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capuani A, Vanzara SV, Rath PK. et al. Off-pump complete myocardia revascularization in low ejection fraction patients (LVEF ≤ 35%): Surgical outlook and mid-term results of 762 consecutive patients. Chirurgie Thoracique Cardio-Vasculaire. 2008;12:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angelini GD. An old off-pump coronary artery bypass surgeon’s reflections: A retrospective. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;pii: S0022– 5223(18):32594–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalewski M, Pawliszak W, Malvindi PG. et al. Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting improves short-term outcomes in high-risk patients compared with on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: Meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(1):60–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]