Abstract

Cp*M-type half-sandwich dichalcogenolate complexes bearing either carborane or benzene moieties show diverse reactivity patterns toward two selected 2,6-disubstituted aryl azides under thermal or photolytic conditions. The chalcogen (S and Se) has little effect on the formation of final products. However, the effects of both the metal center and the ligand moiety of the metal precursor on the reactions were significant. Compared to iridium precursor Cp*IrS2C2B10H10 (1a), rhodium and cobalt analogues (1b: Cp*RhS2C2B10H10, 1c: Cp*CoS2C2B10H10) demonstrated no reactivity toward aryl azides. The reaction of Cp*IrSe2C2B10H10 (1d) with 2,6-Me2C6H3N3 led to the clean formation of complex 2 with C(sp3)–H activation of one methyl group of the Cp* ligand and loss of N2 along with the rearrangement of the benzene ring of the original azide ligand, whereas the treatment of Cp*IrS2C6H4 (1e) with 2,6-Me2C6H3N3 under the same reaction conditions gave a 16-electron half-sandwich complex 5 featuring C–N coupling on one methyl group from the Cp* ligand. When 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 was employed, the same reaction patterns for forming products (3 and 6) with the nitro group migrating to the para-position versus the original aryl azide were observed. In addition, the reaction with metal precursor 1d generated another product 4 featuring the exchange of nitro and azido groups, while the reaction with 1e afforded another complex 7 with the formation of the N–NO2 moiety. All new complexes were characterized by spectroscopy methods, and single-crystal X-ray analyses were performed for complexes 2 and 5–7. Furthermore, radical mechanisms for the formation of complexes 2–7 were proposed.

Introduction

Organic azides are widely used in synthesis of heterocyclic compounds via cycloaddition or insertion with organic unsaturated compounds.1 These species have been recognized as an efficient and convenient nitrogen sources for various types of nitrogen-containing molecules. Among their all possible applications, great emphasis has been devoted to the transition-metal-catalyzed amination of C–H bonds due to their ubiquity in almost all organic skeletons.2 During transition-metal-catalyzed amination, the interaction between metal and organic azide is involved which ultimately plays an important role in the catalysis. Thus, the reactivity of organic azides with transition-metal complexes has attracted considerable interests.3 Generally, organic azides reacting with transition-metal complexes give metal imido derivatives.4 Meanwhile, metal–imide complexes,5 tetra-azabutadiene complexes,6 isocyanate derivatives,5a,7 and triazenide complexes8 are already reported. But in some cases, the reactions of organic azides with transition metal complexes could lead to the formation of unprecedented products with unique structures. For example, dinickel(II) and dicopper(II) diketimide adducts could be obtained from the reaction of aryl azides ArN3 with their suitable precursors.9 And the reaction of the aryl azide 4-Ph-2,6-iPr2C6H3N3 (Ar4PhN3) with [iPr2NN]Cu(NCMe) afforded to the formation of the diazametallocyclobutene complex [iPr2NN]Cu(κ2-N,N-NC(Me)Ar4Ph).9a

We have a long-standing interest in the reactivity of 16-electron half-sandwich complexes Cp#M (Cp# = Cp, Cp*; M = Co, Rh, Ir) and (p-cymene)M (M = Ru, Os) bearing an o-carborane-1,2-dichalcogenolate ligand with small molecules, such as alkynes,10 diazo compounds,11 and organic azides.6a,11c,12 Notably, we reported that the thermal or photochemical reactions of Cp*IrS2C2B10H10 (1a) with 2,6-disubstituted aryl azides led to the C–C coupling and C–S bond formation via radical mechanisms in previous report.12c It was found that the orthosubstituted electron-withdrawing groups in aryl azides are easy to migrate to afford C–S bond products, while the electron-donating ones are inert to the migration and C–C coupling adduct was isolated in the case of 2,6-Me2C6H3N3. Later, we demonstrated also that the reaction of 1a with meta-substituted aryl azide afforded products involving C–C and C–S bond formation via C–H activation undergoing a radical mechanism.12d The unusual reactivity between this type of complexes and aryl azides prompted us to investigate its regularity and generality. It is well known that the carborane ligand is a typical three-dimension and electron-deficient moiety, which always results in different reactivities compared to other simple organic skeletons, such as a benzene moiety.13 Such difference is derived from not only the steric effect but also the electronic effect. Thus, we anticipate that the replacement of carborane with benzene in our studied metal precursors may lead to different product formation. In addition, it was reported that the changing of the metal center as well as the chalcogen binding to the metal center showed some different reaction behaviors towards alkynes.10a,10h,10j Herein, we present our efforts towards understanding the chemistry between Cp*M type half-sandwich complexes varied with a metal center, chalcogen as well as the ligand moiety and selected 2,6-disubstituted aryl azides. With the exception of similar products as we previously reported,12c two new types of products featuring the C–N or N–N bond were obtained. The results show that the reaction products are dependent not only upon the metal center but also the type of aryl azides and the organic moiety of the complexes.

Results and Discussion

In our previous report, 2,6-Me2C6H3N3 and 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 demonstrated totally different reactivity towards 1a, which led to the formation of C–C coupling product I and C–S coupling products II and III, respectively (Scheme 1).12c Thus, we selected these two 2,6-disubstituted aryl azides to investigate the effect of the variation of the metal center, chalcogen, and organic skeleton of the complexes. Initially, when rhodium was employed as a replacement to the iridium center, the rhodium species 1b demonstrated totally inert reactivity towards the selected aryl azides. For cobalt precursor 1c, the reaction with the selected aryl azides did not proceed under the same conditions. Further prolonging the reaction time or increasing reaction temperature resulted in the partial decomposition of complex 1c and trace products were difficult to purify and identify.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Complexes I–III and Metal Effect on the Reaction.

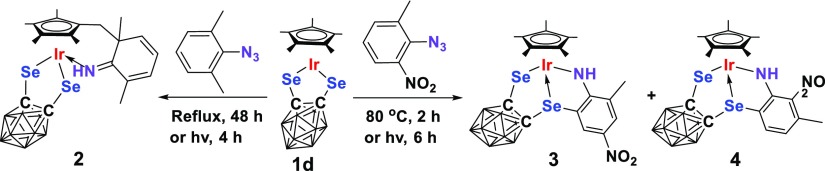

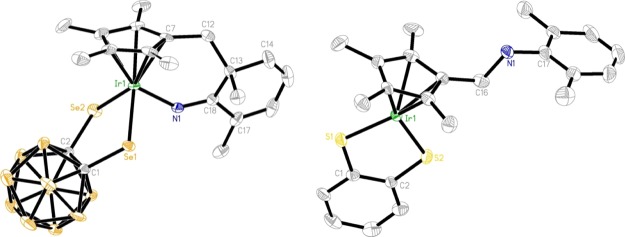

Next, we chose selenium analogue 1d to study the effect of the chalcogen on the reactivity. It was found that products 2–4 analogous to complexes I–III could be isolated in low to moderate yields from the reaction of 1d with 2,6-Me2C6H3N3 and 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3, respectively (Scheme 2). The only difference observed was that complex 1d appeared to be slightly more reactive than the sulfur analogue 1a because its thermal reaction with 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 could be finished within 90 min at 80 °C. This observation was in good agreement with the results concluded in the case of the reaction of 1a and 1d with alkynes.10h Complexes 2–4 were fully characterized by various spectroscopy techniques and elemental analyses. The 1H NMR spectrum of complex 2 gave rise to a typical broad singlet at 10.38 ppm attributable to the NH group, which was 0.2 ppm downfield shifted compared to that in complex I. In addition, resonances associated with the newly generated CH2 protons were observed at δ = 2.45 and 2.29 ppm with J = 15 Hz, and four sets of singlets in the ratio of the 3:3:3:3 intensity in the range of 1.50–1.90 ppm corresponding to the methyl groups in the original Cp* ring. The 13C NMR spectrum showed, in addition to a methylene carbon signal at 17.5 ppm and a signal at 52.4 ppm for a quaternary carbon, a signal at 175.9 ppm attributable to the C=N unit. The solid-state structure of complex 2 was further confirmed by single crystal X-ray analyses. As shown in Figure 1, the Ir atom is η5-bound to the functionalized Cp* ligand, σ-bound to an imino group from the side arm of the functionalized Cp* ligand and an o-carborane-1,2-dichalcogenolate ligand in a three-legged piano stool geometry with angles of 90.57(2)° (Se1–Ir1–Se2), 89.30(13)° (N1–Ir1–Se1) and 84.19(13)° (N1–Ir1–Se2). The Ir1–N1, Ir1–Se1, and Ir1–Se2 bond distances were found to be 2.050(5), 2.4639(7), and 2.4764(7) Å, respectively, which are comparable to those in similar metal carborane analogues.10a,12c,12d The N1–C18 (1.286(7) Å) length is about 0.02 Å shorter than that in the sulfur analogue,12c indicative of a double bond. Similar to those observed in sulfur analogues,12c,12d the broad singlets at 4.66 and 7.73 ppm in the 1H NMR spectra of complexes 3 and 4 are assigned to the characteristic −NH signals. More than the 3 ppm downfield shift of −NH resonance in complex 4 is probably due to the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond between −NH and −NO2 in the solution. In addition, two phenyl proton resonances, which displayed two singlets in 3 and two doublets in 4, are supportive of cyclometalation in these complexes.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Complexes 2–4.

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of 2 (left) and 5 (right) with 30% displacement ellipsoids (all H atoms are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 2: Ir1–N1 2.050(5), Ir1–Se1 2.4639(7), Ir1–Se2 2.4764(7), Se1–C1 1.943(5), Se2–C2 1.943(5), C2–C1 1.645(7), N1–C18 1.286(7), C12–C13 1.555(8), C13–C18 1.521(8); N1–Ir1–Se1 89.30(13), N1–Ir1–Se2 84.19(13), Se1–Ir1–Se2 90.57(2), C18–N1–Ir1 132.6(4), N1–C18–C13 120.5(5), C7–C12–C13 121.0(4), C18–C13–C12 117.0(5). For 5: Ir1–S1 2.236(2), Ir1–S2 2.243(2), C1–C2 1.384(12), C1–S1 1.759(9), C2–S2 1.760(9), C16–N1 1.502(11), C17–N1 1.421(11); S1–Ir1–S2 88.22(8), C2–C1–S1 120.0(7), C1–C2–S2 119.0(7), C17–N1–C16 113.9(7).

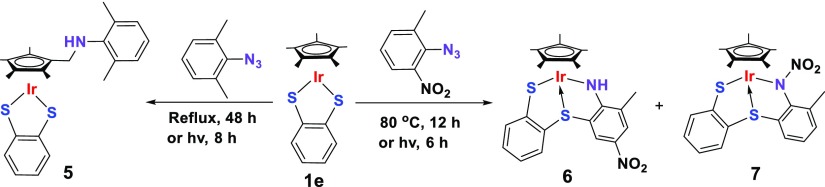

Finally, we employed Cp*Ir(bdt) (1e, bdt = benzene-1,2-dithiolate), based on benzene-1,2-dithiolato, a more readily available, easy to functionalize, and inexpensive ligand than carborane, to investigate its reactivity towards 2,6-Me2C6H3N3 and 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 (Scheme 3). Interestingly, a rather different reactivity was observed in the reaction of complex 1e with excess 2,6-Me2C6H3N3, which resulted in the formation of new complex 5 in moderate yield. Complex 5 was characterized by NMR spectroscopy, elemental analysis, and X-ray crystallography, which confirmed that 5 is an amine-substituted Cp* complex as shown in Scheme 3. Therefore, C(sp3)–H bond amination of the Cp* ligand occurs, which is different from the reaction between carborane adducts 1a, 1d, and 2,6-Me2C6H3N3, where the C–C coupling between one of the methyl group of Cp* and the benzene ring was observed. Complex 5 is a rare example featuring the activation of the C–H bond of the Cp* ligand and the formation of the C–N bond. A similar example was isolated in the reaction of 1a with benzoyl azide in our previous report.12a The 1H NMR spectrum of 5 revealed the presence of three sets of the singlet in a 6:6:6 intensity ratio at δ = 2.25, 2.20, and 2.15 ppm, respectively, corresponding to four methyl groups in the original Cp* ring and two methyl groups of initial aryl azides, along with a characteristic −NH peak at δ = 2.38 ppm. In addition, resonance associated with −CH2 protons was observed at δ = 3.81 ppm, whose corresponding 13C NMR signal appeared at δ = 42.5 ppm. Compound 5 crystallized in the triclinic crystal system with the P1̅ space group. The solid-state structure of 5 accompanied with selected bond parameters are shown in Figure 1. The structure revealed that the one methyl group of the Cp* ligand is bound to the nitrogen atom of the original aryl azide after the loss of N2 to generate a new C–N bond.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Complexes 5–7.

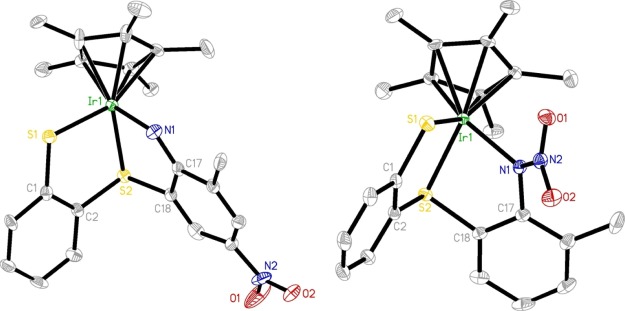

In contrast to the reactions of the iridium precursor-bearing carborane moiety (1a and 1d) with 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3, the interaction of 1e with 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 led to the generation of an analogous product 6 and a new species 7. The 1H NMR data of 6 was consistent with the generation of a secondary amine group and the migration of a nitro group from the orthoposition to the paraposition versus the original aryl azide, evidenced by the appearance of a broad singlet at δ = 4.59 ppm and two singlets at δ = 8.26 and 7.55 ppm. However, no −NH signal could be observed in complex 7. In addition, the resonances of three aryl protons from the original aryl azide in complex 7 indicated that its molecular structure is different from complexes III and 4. To confirm the spectroscopy assignments and to determine the solid-state structure of complexes 6 and 7, we undertook X-ray crystal-structure analysis. Their molecular structures are shown in Figure 2. Both the complexes containing two five-membered metallacyclic motifs (Ir–N–C–C–S and Ir–S–C–C–S) and sharing one Ir–S bond as seen here are similar to those observed in their carborane analogues.12b−12d The only difference between them is the position of the nitro group, which is located at the paraposition versus the original aryl azide in complex 6 and bind directly to the nitrogen atom from the original aryl azide after the loss of N2 in complex 7. This resulted in some deviation of bond and angle parameters with the Ir1–N1 bond in complex 6 (2.061(8) Å) being significantly shorter than that in complex 7 (2.114(3) Å), and consequently the C17–N1–Ir1 angle (122.2(8)°) being larger than the corresponding C17–N1–Ir1 angle (117.5(2)°). Additionally, different from a double bond of N1–C17 (1.306(14) Å) in complex 6, its bond distance (1.416(4) Å) is more than 0.1 Å longer than in complex 7, featuring a typical single bond. It is possible that the strong electron-withdrawing nature of the nitro group is responsible for such a difference. Surprisingly, any attempt to obtain the analogous adducts of complexes III and 4 from the reaction was unsuccessful. This implies that the difference in steric hindrance between the carborane and benzene moiety plays an important role in product formation,13b evidenced by the production of C–N coupling adducts III and 4 with the bulky carborane ligand and N–N coupling complex 7 with the small benzene ligand.

Figure 2.

Molecular structures of 6 (left) and 7 (right) with 30% displacement ellipsoids (all H atoms are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 6: Ir1–S1 2.343(3), Ir1–S2 2.304(3), Ir1–N1 2.061(8), C1–S1 1.751(12), C2–S2 1.785(11), C1–C2 1.370(16), S2–C18 1.784(11), N1–C17 1.306(14), C17–C18 1.437(15); N1–Ir1–S1 88.8(3), N1–Ir1–S2 81.7(3), S2–Ir1–S1 87.86(10), C1–S1–Ir1 104.1(4), C2–S2–Ir1 104.6(4), C18–S2–Ir1 99.5(4), C17–N1–Ir1 122.2(8). For 7: Ir1–S1 2.3547(9), Ir1–S2 2.3112(8), Ir1–N1 2.114(3), C1–S1 1.756(3), C2–S2 1.786(3), C1–C2 1.391(5), S2–C18 1.792(3), N1–C17 1.416(4), C17–C18 1.396(5); N1–Ir1–S2 80.99(8), N1–Ir1–S1 87.54(8), S2–Ir1–S1 87.43(3), C1–S1–Ir1 104.18(11), C2–S2–Ir1 105.97(12), C18–S2–Ir1 99.13(11), C17–N1–Ir1 117.5(2).

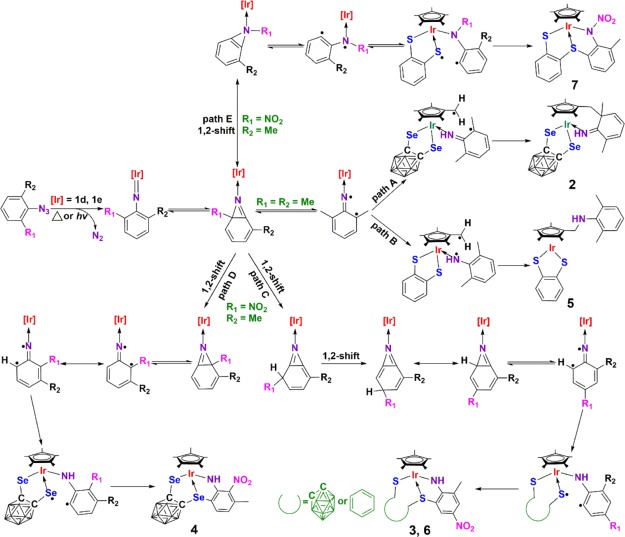

To investigate the possible mechanism for the product formation, photochemical reactions of 1d, 1e with the two selected aryl azides were performed. Similar to the results we previously reported,12c,12d the photolytic reactions could proceed with lower yields of expected compounds than that were isolated under thermal conditions. This fact indicated that the formation of these complexes may underwent a radical mechanism. The speculation was further supported by the EPR experiments, in which complicated radical signals were observed in the in situ photolytic reaction of 1e, 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 and the radical capture reagent, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (Figure S1). On the basis of these results and literature reports,12b−12d,14 the proposed reaction pathways for the formation of 2–7 are shown in Scheme 4. Initial coordination of the azide to the metal, followed by dinitrogen extrusion leads to the formation of the reactive iridium imido intermediate, which can transform into a bicyclic azepine intermediate and then further rearrange to several diradical adducts in five path routes (path A to path E) via the 1,2-shift of the nitro group, resonance and hydrogen abstraction according to the substituted group on aryl azides and the ligand moiety of metal precursors. When 2,6-Me2C6H3N3 was employed, hydrogen abstraction from a methyl group of the Cp* ligand occurred to generate a C–C diradical and a C–N diradical according to the carborane and benzene moiety of iridium precursors, which then formed complexes 2 and 5 via a intramolecular radical coupling, respectively. When 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 was selected, the nitro group could migrate to three orthopositions via the 1,2-shift via the paths from C to E to afford different diradical species. Similar to the analogous product in our previous report,12b−12d intramolecular radical coupling after further transformation of diradical species led to the formation of complexes 3 and 6, 4, and 7, respectively.

Scheme 4. Proposed Reaction Pathways for the Formation of 2–7.

Conclusions

In summary, we have studied the reactivity of Cp*M-type (M = Co, Rh, Ir) 16-electron half-sandwich complexes 1a–1e towards two selected 2,6-disubstituted aryl azides, leading to the isolation of five types of radical coupling products. The nature of the metal center plays a key role in the reactivity and only iridium precursors could undergo the reaction under thermal or photolytic conditions. The chalcogen, either S or Se, does not essentially affect the formation of the final products, whereas the ligand moiety of the metal precursor makes difference. In the case of 2,6-Me2C6H3N3, the metal precursor bearing carborane moiety resulted in the formation of C–C coupling complex 2 while the metal precursor with the benzene moiety afforded the generation of C–N coupling complex 5, both of which featured C(sp3)–H activation of one methyl group of the original Cp* ligand. When 2-Me-6-NO2C6H3N3 was employed, the products, which are complexes 3 and 6, 4, and 7, respectively, formed from nitro migration via the 1,2-shift in three pathways and further rearrangements were isolated. Notably, a N–NO2 moiety presenting in complex 7 is rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example wherein the N–NO2 moiety is formed via the 1,2-shift of the nitro group during the reaction, though the N–NO2 moiety always appears in energetic complexes.15 Compared to the steric hindrance of the bulky carborane ligand, the small steric hindrance of the benzene moiety in the metal precursor may be responsible for the formation of the complex 7 bearing N–NO2 moiety. The diverse reactivity and the modes of product formation shown in this paper support ongoing efforts to develop new metal-mediated stoichiometric and catalytic transformations that are relevant to the goal of small-molecule activation.

Experimental Section

Compounds were prepared and handled by standard Schlenk techniques. Toluene was predried over molecular sieves and distilled over CaH2 under nitrogen prior to use. Metal precursors 1a–1d,161e,17 and aryl azides18 were prepared by literature procedures. The NMR measurements were performed on a Bruker DRX 500 spectrometer. Chemical shifts were given with respect to CHCl3/CDCl3 (δ 1H = 7.24 ppm; δ 13C = 77.0 ppm) and external Et2O·BF3 (δ 11B = 0 ppm). The C, H, and N microanalyses were carried out with an Elementar Vario EL III elemental analyzer. Mass data were determined with a LCQ (ESI–MS, Thermo Finnigan) mass spectrometer. Photolysis experiments were conducted in an XPA-photochemical reactor (Xujiang Electromechanical Plant, Nanjing, China) equipped with a 500 W high-pressure mercury lamp (wavelength 365 nm) at 25 °C. EPR spectra were recorded at room temperature on a Bruker EMX-10/12 spectrometer operating at 9.7 GHz and a cavity equipped with a Bruker AquaX liquid sample cell. Crystallographic data of complexes were collected on a Bruker SMART Apex II CCD diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The crystal structures were solved using direct methods in the SHELXS program and refined by full-matrix least-squares routines, based on F2, using the SHELXL package.19

Typical procedure for thermal reaction: the mixture of complex 1d or 1e (0.2 mmol) and selected aryl azide (1.0 mmol) was heated at 80 °C or in refluxing toluene for 2–48 h. After the removal of the solvent, the crude product was purified by chromatography using silica gel to give the target compound and their characterization data are listed as follows.

2 (82.6 mg, 55.3%). Refluxing in toluene for 48 h. The product was obtained as a yellowish-brown solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 10.38 (s, 1H, NH), 6.37 (d, J = 5 Hz, 1H, C=CH), 6.05 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H, C=CH), 5.98 (dd, J1 = 10 Hz, J2 = 10 Hz, 1H, C=CH), 2.45 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H, CH2), 2.29 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H, CH2), 2.09 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.87 (s, 3H, CH3, Cp*), 1.86 (s, 3H, CH3, Cp*), 1.83 (s, 3H, CH3, Cp*), 1.52 (s, 3H, CH3, Cp*), 1.29 (s, 3H, CH3). 11B{1H} NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 1.8 (1B), −1.7 (2B), −3.6 (3B), −6.0 (4B). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 8.5 (CH3, Cp*), 8.9 (CH3, Cp*), 9.6 (CH3, Cp*), 10.3 (CH3, Cp*), 17.5 (CH2, Cp*), 26.2 (CH3), 27.4 (CH3), 52.4 (C(CH2)CH3), 66.6 (C, Cp*), 68.9 (C, Cp*), 82.4 (C, Cp*), 84.8 (carborane), 88.1 (C, Cp*), 92.8 (carborane), 102.3 (C, Cp*), 118.9 (C=CH), 128.7 (C=CH), 133.0 (C=CH), 141.8 (C=CH), 175.9 (C=N). ESI–MS (m/z): 746.50 (100%) [M]−. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C20H34B10NSe2Ir: C, 32.17; H, 4.59; N, 1.88. Found: C, 32.33; H, 4.85; N, 1.77.

3 (42.3 mg, 27.2%). Heating at 80 °C for 2 h. The product was obtained as a yellowish-brown solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 8.26 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.70 (s, 1H, ArH), 4.66 (s, 1H, NH), 2.19 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.86 (s, 15H, CH3, Cp*). 11B{1H} NMR (CDCl3, ppm): −0.8 (2B), −2.3 (2B), −3.6 (2B), −5.0 (2B), −7.7 (1B), −9.0 (1B). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 9.1 (CH3, Cp*), 18.3 (CH3), 92.6 (carborane), 92.7 (C, Cp*), 100.5 (carborane), 111.9 (C, Ph), 122.7 (C, Ph), 127.1 (CH, Ph), 131.0 (CH, Ph), 133.2 (C, Ph), 166.3 (C, Ph). ESI–MS (m/z): 777.50 (100%) [M]−, 779.33 (20%) [M + H+]+. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C19H31B10N2O2Se2Ir: C, 29.34; H, 4.02; N, 3.60. Found: C, 29.45; H, 4.29; N, 3.33.

4 (44.5 mg, 28.6%). Heating at 80 °C for 2 h. The product was obtained as a yellowish-brown solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 7.73 (s, 1H, NH), 7.32 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.14 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 2.59 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.87 (s, 15H, CH3, Cp*). 11B{1H} NMR (CDCl3, ppm): −0.9 (2B), −2.8 (3B), −5.1 (2B), −6.9 (1B), −7.8 (1B), −9.4 (1B). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 9.2 (CH3, Cp*), 23.1 (CH3), 92.7 (carborane), 95.4 (C, Cp*), 105.5 (carborane), 115.6 (CH, Ph), 118.8 (C, Ph), 128.3 (C, Ph), 131.0 (CH, Ph), 137.2 (C, Ph), 155.1 (C, Ph). ESI–MS (m/z): 777.42 (45%) [M]−, 778.42 (20%) [M]+. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C19H31B10N2O2Se2Ir: C, 29.34; H, 4.02; N, 3.60. Found: C, 29.53; H, 4.36; N, 3.39.

5 (63.7 mg, 54.3%). Refluxing in toluene for 48 h. The product was obtained as a brownish-red solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 8.07 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.05 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.99 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.88 (m, 1H, ArH), 3.81 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.38 (s, 1H, NH), 2.25 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 2.20 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 2.15 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 10.4 (2 × CH3, Cp*), 10.5 (2 × CH3, Cp*), 18.6 (2 × CH3), 42.5 (CH2), 92.0 (2 × C, Cp*), 93.4 (2 × C, Cp*), 123.1 (2 × CH, Ph), 123.3 (2 × C, Ph), 127.9 (CH, Ph), 128.9 (2 × CH, Ph), 129.6 (2 × CH, Ph), 130.8 (2 × C, Ph), 153.4 (C, Ph). ESI–MS (m/z): 588.08 (100%) [M + H]+. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C24H28NS2Ir: C, 49.12; H, 4.81; N, 2.39. Found: C, 49.41; H, 5.06; N, 2.27.

6 (38.4 mg, 31.1%). Heating at 80 °C for 12 h. The product was obtained as a brownish-red solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 8.26 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.62 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.55 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.54 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.91 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.80 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 4.59 (s, 1H, NH), 2.07 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.87 (s, 15H, CH3, Cp*). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 8.8 (CH3, Cp*), 17.9 (CH3), 91.8 (C, Cp*), 121.3 (C, Ph), 121.7 (C, Ph), 123.0 (CH, Ph), 126.0 (CH, Ph), 128.6 (CH, Ph), 128.7 (CH, Ph), 129.4 (CH, Ph), 131.2 (CH, Ph), 132.9 (C, Ph), 139.3 (C, Ph), 150.8 (C, Ph), 164.8 (C, Ph). ESI–MS (m/z): 617.17 (100%) [M]−, 641.17 (70%) [M + Na+]+, 619.25 (20%) [M + H+]+. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C23H25N2S2O2Ir: C, 44.71; H, 4.08; N, 4.53. Found: C, 44.89; H, 4.33; N, 4.18.

7 (32.8 mg, 26.5%). Heating at 80 °C for 12 h. The product was obtained as a brownish-red solid. 1H NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 7.68 (d, J = 5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.56 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.43 (d, J = 5 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.08 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.92 (t, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.85 (t, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.72 (t, J = 10 Hz, 1H, ArH), 2.52 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.88 (s, 15H, CH3, Cp*). 13C NMR (CDCl3, ppm): 9.4 (CH3, Cp*), 24.2 (CH3), 92.8 (C, Cp*), 122.1 (CH, Ph), 124.2 (CH, Ph), 128.3 (CH, Ph), 128.7 (CH, Ph), 129.4 (CH, Ph), 130.6 (CH, Ph), 132.0 (C, Ph), 132.5 (C, Ph), 134.6 (CH, Ph), 134.9 (C, Ph), 152.1 (C, Ph), 152.4 (C, Ph). ESI–MS (m/z): 617.17 (28%) [M]−. Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C23H25N2S2O2Ir: C, 44.71; H, 4.08; N, 4.53. Found: C, 44.96; H, 4.37; N, 4.32.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Project funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2017M621697) and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LY18B010007) for supporting this work.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b01364.

Accession Codes

CCDC 1913131–1913134 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Bräse S.; Gil C.; Knepper K.; Zimmermann V. Organic Azides: An Exploding Diversity of a Unique Class of Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5188–5240. 10.1002/anie.200400657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang D.; Yan G. Recent Advances in Reactions of Azides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 1600–1619. 10.1002/adsc.201700103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Intrieri D.; Zardi P.; Caselli A.; Gallo E. Organic azides: “energetic reagents” for the intermolecular amination of C–H bonds. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11440–11453. 10.1039/c4cc03016h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shin K.; Kim H.; Chang S. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed C-N Bond Forming Reactions Using Organic Azides as the Nitrogen Source: A Journey for the Mild and Versatile C-H Amination. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1040–1052. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Driver T. G. Recent advances in transition metal-catalyzed N-atom transfer reactions of azides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 3831–3846. 10.1039/c005219c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cenini S.; La Monica G. Organic azides and isocyanates as sources of nitrene species in organometallic chemistry. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1976, 18, 279–293. 10.1016/s0020-1693(00)95618-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cenini S.; Gallo E.; Caselli A.; Ragaini F.; Fantauzzi S.; Piangiolino C. Coordination chemistry of organic azides and amination reactions catalyzed by transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 1234–1253. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Jenkins D. M.; Betley T. A.; Peters J. C. Oxidative Group Transfer to Co(I) Affords a Terminal Co(III) Imido Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 11238–11239. 10.1021/ja026852b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Laskowski C. A.; Miller A. J. M.; Hillhouse G. L.; Cundari T. R. A Two-Coordinate Nickel Imido Complex That Effects C–H Amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 771–773. 10.1021/ja1101213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hu X.; Meyer K. Terminal Cobalt(III) Imido Complexes Supported by Tris(Carbene) Ligands: Imido Insertion into the Cobalt–Carbene Bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 16322–16323. 10.1021/ja044271b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Waterman R.; Hillhouse G. L. η2-Organoazide Complexes of Nickel and Their Conversion to Terminal Imido Complexes via Dinitrogen Extrusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12628–12629. 10.1021/ja805530z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Harrold N. D.; Waterman R.; Hillhouse G. L.; Cundari T. R. Group-Transfer Reactions of Nickel–Carbene and −Nitrene Complexes with Organoazides and Nitrous Oxide that Form New C=N, C=O, and N=N Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12872–12873. 10.1021/ja904370h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Iluc V. M.; Miller A. J. M.; Anderson J. S.; Monreal M. J.; Mehn M. P.; Hillhouse G. L. Synthesis and Characterization of Three-Coordinate Ni(III)-Imide Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 13055–13063. 10.1021/ja2024993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wu H.; Hall M. B. A New Mechanism for the Conversion of Transition Metal Azides to Imido Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16452–16453. 10.1021/ja805105q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Travia N. E.; Xu Z.; Keith J. M.; Ison E. A.; Fanwick P. E.; Hall M. B.; Abu-Omar M. M. Observation of Inductive Effects That Cause a Change in the Rate-Determining Step for the Conversion of Rhenium Azides to Imido Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 10505–10514. 10.1021/ic2017853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Geer A. M.; Tejel C.; López J. A.; Ciriano M. A. Terminal Imido Rhodium Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5614–5618. 10.1002/anie.201400023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Bellow J. A.; Yousif M.; Cabelof A. C.; Lord R. L.; Groysman S. Reactivity Modes of an Iron Bis(alkoxide) Complex with Aryl Azides: Catalytic Nitrene Coupling vs Formation of Iron(III) Imido Dimers. Organometallics 2015, 34, 2917–2923. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Liu Y.; Du J.; Deng L. Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of Low-Spin Cobalt(II) Imido Complexes [(Me3P)3Co(NAr)]. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8278–8286. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Brown S. D.; Betley T. A.; Peters J. C. A Low-Spin d5 Iron Imide: Nitrene Capture by Low-Coordinate Iron(I) Provides the 4-Coordinate Fe(III) Complex [PhB(CH2PPh2)3]Fe⋮N-p-tolyl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 322–323. 10.1021/ja028448i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Guillemot G.; Solari E.; Floriani C.; Rizzoli C. Nitrogen-to-Metal Multiple Bond Functionalities: The Reaction of Calix[4]arene–W(IV) with Azides and Diazoalkanes. Organometallics 2001, 20, 607–615. 10.1021/om000612s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Manßen M.; Weimer I.; Adler C.; Fischer M.; Schmidtmann M.; Beckhaus R. From Organic Azides through Titanium Triazenido Complexes to Titanium Imides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 131–136. 10.1002/ejic.201701273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Harman W. H.; Lichterman M. F.; Piro N. A.; Chang C. J. Well-Defined Vanadium Organoazide Complexes and Their Conversion to Terminal Vanadium Imides: Structural Snapshots and Evidence for a Nitrene Capture Mechanism. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 10037–10042. 10.1021/ic301673g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhong W.; Yang Q.; Shang Y.; Liu G.; Zhao H.; Li Y.; Yan H. Synthesis and Reactivity of the Imido-Bridged Metallothiocarboranes CpCo(S2C2B10H10)(NSO2R). Organometallics 2012, 31, 6658–6668. 10.1021/om300735d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Albertin G.; Antoniutti S.; Bacchi A.; Celebrin A.; Pelizzi G.; Zanardo G. Reactions of manganese and rhenium complexes with organic azides: preparation of tetraazabutadiene derivatives. Dalton Trans. 2007, 661–668. 10.1039/b613964g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Heyduk A. F.; Blackmore K. J.; Ketterer N. A.; Ziller J. W. Azide Addition To Give a Tetra-azazirconacycle Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 468–470. 10.1021/ic048560c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Meyer K. E.; Walsh P. J.; Bergman R. G. A Mechanistic Study of the Cycloaddition-Cycloreversion Reactions of Zirconium-Imido Complex Cp2Zr(N-t-Bu)(THF) with Organic Imines and Organic Azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 974–985. 10.1021/ja00108a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley R. E.; Eckert N. A.; Elhaïk J.; Holland P. L. Catalytic nitrene transfer from an imidoiron(III) complex to form carbodiimides and isocyanates. Chem. Commun. 2009, 1760–1762. 10.1039/b820620a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hillhouse G. L.; Haymore B. L. Syntheses and reactions of WH(CO)2(NO)(P(C6H5)3)2 and related tungsten nitrosyl complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1987, 26, 1876–1885. 10.1021/ic00259a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Camarena-Díaz J. P.; Iglesias A. L.; Chávez D.; Aguirre G.; Grotjahn D. B.; Rheingold A. L.; Parra-Hake M.; Miranda-Soto V. Rh(III)Cp* and Ir(III)Cp* Complexes of 1-[(4-Methyl)phenyl]-3-[(2-methyl-4′-R)imidazol-1-yl]triazenide (R = t-Bu or H): Synthesis, Structure, and Catalytic Activity. Organometallics 2019, 38, 844–851. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hillhouse G. L.; Bercaw J. E. Monosubstituted triazenido complexes as intermediates in the formation of amido complexes from hafnium hydrides and aryl azides. Organometallics 1982, 1, 1025–1029. 10.1021/om00068a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Bakhoda A. G.; Jiang Q.; Bertke J. A.; Cundari T. R.; Warren T. H. Elusive Terminal Copper Arylnitrene Intermediates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6426–6430. 10.1002/anie.201611275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bai G.; Stephan D. W. Formation of C–C and C–N Bonds in NiII Ketimide Complexes via Transient NiIII Aryl Imides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1856–1859. 10.1002/anie.200604547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Herberhold M.; Yan H.; Milius W.; Wrackmeyer B. Metal-induced B–H activation. Addition of phenylacetylene to Cp*Rh-, Cp*Ir-, (p-cymene)Ru- and (p-cymene)Os halfsandwich complexes containing a chelating 1,2-dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolate ligand. J. Organomet. Chem. 2000, 604, 170–177. 10.1016/s0022-328x(00)00221-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li Y.; Ye H.; Guoyiqibayi G.; Jiang Q.; Li Y.; Yan H. Reactions of a 16-electron Cp*Co half-sandwich complex containing a chelating 1,2-dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dithiolate ligand with alkynones HC≡C-C(O)R (R = OMe, Me, Ph). Sci. China: Chem. 2010, 53, 2129–2138. 10.1007/s11426-010-4103-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Ye H.-D.; Ding G.-Y.; Xie M.-S.; Li Y.-Z.; Yan H. Reactivity of the 16eCp*Co half-sandwich complex containing a chelating 1,2-dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dithiolate ligand towards alkynes. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 2306–2313. 10.1039/c0dt00933d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Xu B.-H.; Wu D.-H.; Li Y.-Z.; Yan H. Reactivity of CpCo 16e Half-Sandwich Complexes Containing a Chelating 1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolate Ligand toward Phenylacetylene. Organometallics 2007, 26, 4344–4349. 10.1021/om700454p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Xu B.-H.; Tao J.-C.; Li Y.-Z.; Li S.-H.; Yan H. Metal-Induced B–H Bond Activation: Addition of Methyl Acetylene Monocarboxylate to CpCo Half-Sandwich Complexes Containing a Chelating 1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolate Ligand. Organometallics 2008, 27, 334–340. 10.1021/om7009864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Xu B.-H.; Peng X.-Q.; Li Y.-Z.; Yan H. Reactions of 16e CpCo Half-Sandwich Complexes Containing a Chelating 1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolate Ligand with Ethynylferrocene and Dimethyl Acetylenedicarboxylate. Chem.—Eur. J. 2008, 14, 9347–9356. 10.1002/chem.200801136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Li Y.; Jiang Q.; Li Y.; Yan H.; Bregadze V. I. Cobalt-Mediated B–H Activation and Cyclopentadienyl-Participated Diels–Alder Addition in the Reaction of a 16e CpCo Complex Containing ano-Carborane-1,2-dithiolato Ligand with HC≡C–C(O)Ph. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 4–6. 10.1021/ic901970b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Herberhold M.; Yan H.; Milius W.; Wrackmeyer B. Metal-Induced B–H Activation: Addition of Acetylene, Propyne, or 3-Methoxypropyne to Rh(Cp*), Ir(Cp*), Ru(p-cymene), and Os(p-cymene) Half-Sandwich Complexes Containing a Chelating 1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolato Ligand. Chem.—Eur. J. 2002, 8, 388–395. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Herberhold M.; Yan H.; Milius W.; Wrackmeyer B. Selective stepwise carborane substitution in B(3,6) positions in Cp*Ir half-sandwich complexes containing a chelating 1,2-dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolato ligand. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001, 1782–1789. 10.1039/b100120p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Herberhold M.; Yan H.; Milius W.; Wrackmeyer B. Metal-Induced B–H Activation: Addition of Methyl Acetylene Carboxylates to Cp*Rh-, Cp*Ir-, (p-cymene)Ru-, and (p-cymene)Os Half-Sandwich Complexes Containing the Chelating 1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaborane- 1,2-dithiolate Ligand. Chem.—Eur. J. 2000, 6, 3026–3032. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Herberhold M.; Yan H.; Milius W.; Wrackmeyer B. Rhodium-Induced Selective B(3)/B(6)-Disubstitution of ortho-Carborane-1,2-dithiolate. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 3689–3691. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Liu G.; Yan H. Metal-Induced B–H Activation in Three-Component Reactions: 16-Electron Complex CpCo(S2C2B10H10), Ethyl Diazoacetate, and Alkynes. Organometallics 2015, 34, 591–598. 10.1021/om501016w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Liu G.; Hu J.; Wen J.; Dai H.; Li Y.; Yan H. Cobalt-Mediated Selective B–H Activation and Formation of a Co–B Bond in the Reaction of the 16-Electron CpCo Half-Sandwich Complex Containing ano-Carborane-1,2-dithiolate Ligand with Ethyl Diazoacetate. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 4187–4194. 10.1021/ic200333q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhong W.; Xie M.; Li Y.; Yan H. Investigation into the reactivity of 16-electron complexes Cp#Co(S2C2B10H10) (Cp# = Cp, Cp*) towards methyl diazoacetate and toluenesulphonyl azide. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 61799–61808. 10.1039/c4ra13017k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhong W.; Yan H.; Li Y.; Bregadze V. I. Reactivity of Cp*M (M = Co, Rh, Ir) half-sandwich complexes containing a chelating 1,2-dicarba-closo-dodecaborane-1,2-dichalcogenolato ligand with organic azides. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2014, 63, 953–962. 10.1007/s11172-014-0533-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhong W.; Yan H. Reactivity of Unsaturated 16e Half-Sandwich Complex Cp*Ir(S2C2B10H10) with ortho- and meta-Substituted Phenyl Azides. Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 31, 1305–1314. 10.11862/CJIC.2015.205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhong W.; Xie M.; Jiang Q.; Li Y.; Yan H. Unusual group migration and C(sp3)-H activation leading to stable metallacycles in the reactions of Cp*IrS2C2B10H10 and aryl azides. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2152–2154. 10.1039/c2cc16943f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhong W.; Jiang Q.; Zhang Q.; Shang Y.; Yan H.; Bregadze V. Radical coupling for directed C-C/C-S bond formation in the reaction of Cp*IrS2C2B10H10 with 1-azido-3-nitrobenzene. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 4962–4968. 10.1039/c3dt52308j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Han Y.-F.; Jin G.-X. Half-Sandwich Iridium- and Rhodium-based Organometallic Architectures: Rational Design, Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3571–3579. 10.1021/ar500335a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pitto-Barry A.; Lupan A.; Zegke M.; Swift T.; Attia A. A. A.; Lord R. M.; Barry N. P. E. Pseudo electron-deficient organometallics: limited reactivity towards electron-donating ligands. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 15676–15683. 10.1039/c7dt02827j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Schwier T.; Sromek A. W.; Yap D. M. L.; Chernyak D.; Gevorgyan V. Mechanistically Diverse Copper-, Silver-, and Gold-Catalyzed Acyloxy and Phosphatyloxy Migrations: Efficient Synthesis of Heterocycles via Cascade Migration/Cycloisomerization Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 9868–9878. 10.1021/ja072446m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yu J.-D.; Ding W.; Lian G.-Y.; Song K.-S.; Zhang D.-W.; Gao X.; Yang D. Selective Approach toward Multifunctionalized Lactams by Lewis Acid Promoted PhSe Group Transfer Radical Cyclization. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 3232–3239. 10.1021/jo100139u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Stokes B. J.; Liu S.; Driver T. G. Rh2(II)-Catalyzed Nitro-Group Migration Reactions: Selective Synthesis of 3-Nitroindoles from β-Nitro Styryl Azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4702–4705. 10.1021/ja111060q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hou Z.; Fujita A.; Koizumi T.-a.; Yamazaki H.; Wakatsuki Y. Transfer of Ketyls from Alkali Metals to Transition Metals. Formation and Diverse Reactivities of d-Block Transition-Metal Ketyls. Organometallics 1999, 18, 1979–1985. 10.1021/om981013c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Sun K.; Sachwani R.; Richert K. J.; Driver T. G. Intramolecular Ir(I)-Catalyzed Benzylic C–H Bond Amination ofortho-Substituted Aryl Azides. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3598–3601. 10.1021/ol901317j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Karney W. L.; Borden W. T. Why Doeso-Fluorine Substitution Raise the Barrier to Ring Expansion of Phenylnitrene?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 3347–3350. 10.1021/ja9644440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Johnson W. T. G.; Sullivan M. B.; Cramer C. J. meta and para substitution effects on the electronic state energies and ring-expansion reactivities of phenylnitrenes. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2001, 85, 492–508. 10.1002/qua.1518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Tsao M.-L.; Platz M. S. Photochemistry of Ortho, Ortho’ Dialkyl Phenyl Azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12014–12025. 10.1021/ja035833e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i van der Vlugt J. I. Radical-Type Reactivity and Catalysis by Single-Electron Transfer to or from Redox-Active Ligands. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 2651–2662. 10.1002/chem.201802606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Kuijpers P. F.; van der Vlugt J. I.; Schneider S.; de Bruin B. Nitrene Radical Intermediates in Catalytic Synthesis. Chem.—Eur. J. 2017, 23, 13819–13829. 10.1002/chem.201702537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Il’yasov S. G.; Lobanova A. A.; Popov N. I.; Kazantsev I. V.; Varand V. L.; Larionov S. V. Synthesis and properties of Fe(II), Ni(II), Co(II), and Zn(II) chelates with 4-nitrosemicarbazide. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2006, 76, 1719–1723. 10.1134/s1070363206110077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fischer N.; Joas M.; Klapötke T. M.; Stierstorfer J. Transition Metal Complexes of 3-Amino-1-nitroguanidine as Laser Ignitible Primary Explosives: Structures and Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 13791–13802. 10.1021/ic402038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J.-Y.; Park Y.-I.; Ko J.; Park K.-I.; Cho S.-I.; Ook Kang S. Synthesis, X-ray crystal structure, and reactivity of the monomeric dithio-o-carboranyl iridium complex [Ir(η5-C5Me5)(η2-S2C2B10H10)]. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1999, 289, 141–148. 10.1016/s0020-1693(99)00064-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nejman P. S.; Morton-Fernandez B.; Moulding D. J.; Athukorala Arachchige K. S.; Cordes D. B.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Kilian P.; Woollins J. D. Structural diversity of bimetallic rhodium and iridium half sandwich dithiolato complexes. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 16758–16766. 10.1039/c5dt02542g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall L. Pyrolysis of Aryl Azides. VII. Interpretation of Hammett Correlations of Rates of Pyrolysis of Substituted 2-Nitroazidobenzenes. Aust. J. Chem. 1986, 39, 89–101. 10.1071/ch9860089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. 10.1107/s0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.