Abstract

We have developed a dual-chambered bioreactor (DCB) that incorporates a membrane to study stratified 3D cell populations for skin tissue engineering. The DCB provides adjacent flow lines within a common chamber; the inclusion of the membrane regulates flow layering or mixing, which can be exploited to produce layers or gradients of cell populations in the scaffolds. Computational modeling and experimental assays were used to study the transport phenomena within the bioreactor. Molecular transport across the membrane was defined by a balance of convection and diffusion; the symmetry of the system was proven by its bulk convection stability, while the movement of molecules from one flow line to the other is governed by coupled convection-diffusion. This balance allowed the perfusion of two different fluids, with the membrane defining the mixing degree between the two. The bioreactor sustained two adjacent cell populations for 28 days, and was used to induce indirect adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells due to molecular cross-talk between the populations. We successfully developed a platform that can study the dermis-hypodermis complex to address limitations in skin tissue engineering. Furthermore, the DCB can be used for other multilayered tissues or the study of communication pathways between cell populations.

Keywords: bioreactor, membrane, cellular co-culture, stratified tissues, skin

Introduction

Skin is composed of multiple stratified layers that act as a protective barrier against external mechanical and biochemical factors (Arumugasaamy, Navarro, Kent Leach, Kim, & Fisher, 2018; Zhang & Michniak-Kohn, 2012). Mammalian skin layers include the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The outermost epidermis layer consists almost entirely of keratinocytes (~95%) (Böttcher-Haberzeth et al., 2010; Markeson et al., 2015). The dermis, which provides mechanical resistance, is mostly fibroblasts synthesizing collagen (mostly type I, and minor types IV and VII), elastin, and proteoglycans (Böttcher-Haberzeth et al., 2010; Kolarsick, Kolarsick, & Goodwin, 2011; Markeson et al., 2015; McLafferty, Hendry, & Farley, 2012). Lastly, the hypodermis consists of mature adipocytes that provide insulation (Böttcher-Haberzeth et al., 2010; McLafferty et al., 2012), and is an important source of stem cells (Kang, Gimble, & Kaplan, 2009; Zhang & Michniak-Kohn, 2012) and endocrine hormones and growth factors (Hebert et al., 2009; Jin, Xiao, Ge, Zhan, & Zhou, 2015; Kolarsick et al., 2011; Salathia, Shi, Zhang, & Glynne, 2013; Shibata et al., 2012; Wong, Geyer, Weninger, Guimberteau, & Wong, 2016) that have important roles in re-epithelization and angiogenesis processes of skin (Hamuy et al., 2013; Makino et al., 2010; Shook et al., 2016).

The interactions between layers allow for skin to be an efficient barrier and any damage to it causes immediate compromised thermoregulation, fluid shifts, and risk of sepsis (Arumugasaamy et al., 2018; Markeson et al., 2015; Peck, Molnar, & Swart, 2009). Also, blood vessels and nerves grow along the interfaces of these layers forming the vascular plexuses; a lack of synergistic development of the layers results in deficient vascularization and innervation which impairs skin function (Kolarsick et al., 2011; Markeson et al., 2015; McLafferty et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2016). Just as important as the layer-to-layer relation is for function in vivo, stratification could play a major role in healing and regeneration in vitro. By letting layer-specific factors diffuse into an adjacent layer it would be possible to study how communication drives regeneration, but it is imperative to have both layers growing together. But, hypodermis adipocytes and dermis fibroblasts are not cultured in vitro using the same media, nor are their progenitor stem cells. To produce a dermis-hypodermis complex that benefits from the synergistic development of both populations it is necessary to advance technologies for stratified co-culturing. Here we present a dual-chambered bioreactor (DCB) to study stratified 3D cell populations, working towards a dermis-hypodermis complex (Figures 1A–B).

Figure 1.

DCB design and 3D printing. A) Layered microstructure of human skin and our approach to the development of a simplified layered tissue engineering scaffold. B) Approach to the formation of strata and gradients in a DCB. i) When cultured independently, scaffolds have a single, homogeneous cell population; layering the scaffolds in vivo would result in poor integration and uncontrolled gradient interface. ii) The DCB allows two flow lines of media into a common chamber; without a barrier, the two flows would mix producing a gradient. iii) Inclusion of a membrane in the DCB would keep the flow lines separated producing a stratified construct; permeability of the membrane would regulate transport between the two sides. C) i) The DCB is composed of two equal master pieces that can be sealed together; ii) the master piece is composed of an inlet, an outlet, and an open centerpiece, as well as including guide channels for sealing gaskets; iii-iv) when combined, the cross-section reveals a common chamber that provides an interface for communication between the two flow lines. D-E) The master pieces and custom porous scaffolds for cell culturing were 3D printed on a Perfactory 4 DLP printer (EnvisionTEC) using EShell resin. F) The final DCB system assembled has been optimized to have maximum external dimensions of 64 × 40 × 23 mm (length, width, height), an effective internal volume of 3.8 ml (total volume as seen in Fig. Civ in green, shades distinguish the two halves that compose it), and inlet and outlet connections to standard 1/8” (3.175 mm) inner diameter tubing.

Perfusion bioreactors are used to culture cell populations with specific growth media (Nguyen, Ko, & Fisher, 2016; Yeatts & Fisher, 2011; Yeatts, Gordon, & Fisher, 2011). If different scaffolds are grown in separate bioreactors, they each develop a cell population with distinct characteristics. These scaffolds can be bound together in vitro or in vivo using a variety of layering techniques, usually crosslinking (Gleghorn, Lee, Cabodi, Stroock, & Bonassar, 2008; Gurkan et al., 2014; Harley et al., 2009; B. S. Kim et al., 2014; M. Kim & Kim, 2015; Levingstone et al., 2016; Pi et al., 2018; G. Yang, Lin, Rothrauff, Yu, & Tuan, 2016), sintering (Camarero-Espinosa, Rothen-Rutishauser, Weder, & Foster, 2016; Costa et al., 2014; Mosher, Spalazzi, & Lu, 2015; Spalazzi, Doty, Moffat, Levine, & Lu, 2006), or by inducing extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition (Asano, Shimoda, Okano, Matsusaki, & Akashi, 2017; Matsusaki et al., 2015; Matsuzawa, Matsusaki, & Akashi, 2015; Ng, Qi, Yeong, & Naing, 2018; Nishiguchi, Yoshida, Matsusaki, & Akashi, 2011; Papenburg et al., 2009), but it is difficult to predict the interface that will form (Figure 1Bi). In the DCB, two parallel flow inlets connect to a common chamber, followed by two flow outlets (Figure 1Bii). As it is, the flow lines gradually mix with each other in the common chamber. This mixing results in continuous gradients rather than a defined interface (Lin, Lozito, Alexander, Gottardi, & Tuan, 2014; Lozito et al., 2013). We hypothesized that introducing a permeable barrier in the DCB reduces mixing without altering the diffusion of small molecules from one side to the other (Figure 1Biii). This reduces cellular migration but allows communication between both sides by exchange of biomolecules coming from the cells or media. We used keratin-based membranes with varying permeability to regulate diffusion between the lines, aiming to control molecular cross-talk between cell populations.

We previously reported the development of keratin-based hydrogel membranes that can be fine-tuned to regulate transport across them (Navarro, Swayambunathan, Lerman, Santoro, & Fisher, 2019; Navarro, Swayambunathan, Santoro, & Fisher, 2018). Here we assessed the viability of our DCB for growing adjacent cell populations with the inclusion of a keratin membrane. To this end, the objectives of this work were to assess the viability of the DCB to: 1) perfuse adjacent layers with different media; 2) allow communication between layers via diffusion through a permeable barrier; 3) co-culture and sustain adjacent cell populations; and 4) allow for the assessment of the effects that one cell population can induce on an adjacent layer.

Methods

Bioreactor design and 3D printing

A computer-aided design (CAD) model file for the DCB was created in SolidWorks® (Dassault Systèmes SE, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France). As illustrated in Figures 1Ci–ii, the DCB is assembled using a master part twice. This part consists of an inlet and an outlet that feed into a chamber with an open wall (internal dimensions: 10 × 10 × 8 mm), and channels for silicone rubber sealing gaskets (custom-made, 50A durometer, 2 mm thick) (Figure 1Cii). The master parts were 3D printed out of EShell 300 resin on a stereolithography-based printer (Perfactory 4 DLP printer, EnvisionTEC Inc., Dearborn, MI). Stainless steel hardware (#10–24 0.5” screws and nuts) and the gaskets were used to close the DCB. When assembled, the cross-section reveals a common chamber (10 × 10 × 17.5 mm) with parallel inlet-outlet lines (Figures 1Ciii–iv). The inlet/outlet connections match 16-gauge pump tubing, which were connected to 1/8” ID platinum cured silicone tubing using 1/8”−1/8” Kynar connectors as needed (all Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL). Porous scaffolds (9.8 × 9.8 × 8 mm, with 800 μm3 pores) were 3D printed with EShell to fit into the chambers. For experiments involving cells, all EShell parts were sterilized using ethanol:phosphate buffered saline (PBS) serial washes (100:0, 75:25: 50:50, 25:75 and 0:100 for 20 min at each step under ultraviolet (UV) light) and stored in fresh sterile PBS at 4°C until use. All tubing, connectors, stainless steel hardware, and the silicone gaskets were autoclaved.

Computational modeling

The CAD files were used in SolidWorks® Flow Simulation to run computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations of transport in the DCB assembled with scaffolds and membrane. Gravity was set anti-parallel to flow, and the type of flow was modeled with the “Laminar and Turbulent” package option for thoroughness (Sobachkin & Dumnov, 2014). The water profile was copied and renamed to create identical Donor Fluid and Receiver Fluid. Boundary conditions defined outlets at environmental pressure (101325 Pa), and inlets to equal flow rates (at 1, 4, or 10 ml/min). At inlet one, the initial volume fraction of Donor Fluid was set to 100%, while Receiver Fluid was set to 0%. Likewise, at inlet two the initial volume fraction of Donor Fluid was set to 0% and Receiver Fluid to 100%. Initial mesh size was set at level 6 of 7 (~ 6×105 fluid cells, 6.27×10−3 mm3 fluid cell volume) to ensure that mesh fluid cells were smaller than the scaffold (0.512 mm3) or barrier pores (0.0554 mm3, described below) to provide adequate resolution. The results were used to map shear stress, velocity, and the volume fractions. The maximum shear stress on each scaffold and the final volume fraction of both fluids at each outlet were recorded and used to set up iterations modeling the DCB loops. The output volume fractions were used as the inlets volume fractions and ran again as the next iteration. This iteration process continued until the volume fraction of each fluid in each chamber was 50 ± 1%, after which the system was assumed equilibrated. Iteration runs were done for every flow rate with and without a solid porous barrier. The barrier, to model the membrane, was a solid plate with holes to match 55% (100 holes, 420 μm diameter) or 99% (4 μm thick wire mesh) porosity. The iteration count was normalized to flow rate to get time-comparative differences between groups, as chamber volumes are equal. The final data set described the changes in volume fraction of the donor and receiver over the iteration progression.

Preparation of keratin membranes

Keratin was extracted from oxidized human hair using a proprietary method by KeraNetics LLC (Winston-Salem, NC) (Placone et al., 2017; Tomblyn et al., 2016). Keratin-based photocrosslinkable resin was prepared as previously reported (Navarro et al., 2019; Placone et al., 2017). Briefly, keratin was dissolved in PBS (pH 7.4) at a 4% wt/vol concentration, and then mixed with a photosensitive solution at a 4:1 ratio. The photosensitive solution consisted of 1 mM riboflavin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), 200 mM sodium persulfate (SPS, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.001% wt/vol hydroquinone (Sigma-Aldrich). After thorough mixing the resin is curable under UV light by formation of dityrosine bonds. The resin was used in 3D printed molds to cast membranes (12 × 12 × 1.5 mm), exposing to UV at an intensity of 350 mW/dm2. Membranes were produced with 20% low and 59% high crosslinking degree (LCD and HCD) by regulating the amount of energy delivered to the sample during crosslinking (Navarro et al., 2019, 2018). Samples were thoroughly rinsed to remove unreacted components and stored in PBS at 4°C.

Membrane degradation assessment

LCD and HCD membranes were tested in the DCB as described next; after each test, membranes were recovered and qualitatively assessed according to the criteria outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Qualitative assessment of keratin-based membranes recovered from DCB runs

| Qualification | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Complete sample | Full membrane recovered in a single piece |

| Minor dissolution | Membrane recovered in a single piece, parts are missing or thinned out |

| Advanced dissolution | Membrane recovered in pieces, parts are missing or inside the scaffolds |

| Complete dissolution | No membrane left between or inside the scaffolds |

Diffusion in the DCB

DCBs were assembled and fitted with porous scaffolds. Sampling ports were opened on each side of the DCB and kept sealed with casted paraffin plugs. The DCB was filled with PBS (1.6 ml per side), after which all inlets and outlets were sealed, and the system was left to stabilize for 1 h. This setup was tested without a membrane, with LCD, or with HCD membranes (at least n=4). Next, 50 μl of green food dye (McCormick, Baltimore, MD) which is composed of tartrazine (FD&C Yellow 5, 534.4 Da) and brilliant blue FCF (FD&C Blue 1, 792.8 Da), was added to the donor chamber. A 5 μl sample was collected from the donor and receiver sides using the sampling ports and diluted with 95 μl of PBS. Sampling was done every 3 min for 1 h for the cases without membrane; the cases with membranes were sampled every 5 min for the first hour, then every 30 min for 8 h, and finally every 2 h during 10 h segments for up to 8 d. Samples were tested in triplicate for absorbance values of tartrazine and brilliant blue at 425 and 630 nm using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) alongside a concentration ladder. Concentration values were normalized to initial donor concentrations. Permeability was calculated assuming constant volume (volume loss was 5 to 11% per chamber), known initial donor and receiver concentrations, and that flux across the membrane quickly reaches steady state. As such, we used a pseudo-steady state model, in which the concentration profile across the membrane is assumed invariant, to calculate the permeability (P) of the molecules crossing the hydrogel membrane by plotting (Cussler, 2009):

| (1) |

Where Cd is donor concentration at time t; Cr is receiver concentration at time t; Cd0 is initial donor concentration; Cr0 is initial receiver concentration; t is time; A is membrane area; L is membrane thickness; Vd is donor volume; and Vr is receiver volume.

Bulk convection in the DCB

A multi-channel rotary pump (Masterflex L/S with 4- or 8-channel pump head) was used to run parallel DCBs. The DCB required two pump lines, each connected in sequence the pump, the chamber inlet, chamber outlet, a 3-way connector to a 1 ml syringe for sampling, a 50 ml reservoir, and back to the pump. The bioreactor loops were filled with PBS, removing all air from the lines and scaffolds, and equilibrated for 30 min at constant flow rate (1, 4, or 10 ml/min). The pumps were then stopped, and the initial volume of the reservoirs was recorded. Flow was restarted and ran undisturbed for 24 h, the point at which the final volume at the reservoirs was recorded. This setup was evaluated without a membrane, with LCD, or with HCD membranes for each flow rate (at least n=4). The change in volume in each line (named donor and receiver) over 24 h was calculated as the difference in the reservoir volume between 0 and 24 h, over the initial reservoir volume, and reported as a percentage.

Dynamic assessment of transport in the DCB (convection and diffusion)

DCB setups using the rotary pump (as described above) were used to quantify transport in the system under dynamic conditions. The bioreactor loops were filled with PBS, removing all air from the lines and scaffolds, and equilibrated for 30 min at constant flow rate (1, 4, or 10 ml/min) to have stable 40 ml volumes in the reservoirs. This setup was evaluated without a membrane, with a Parafilm® M (Bemis Co., Oshkosh, WI) impermeable barrier, with LCD, or with HCD membranes for each flow rate (at least n=4). After, 200 μl of green dye was added to the donor reservoir. A 300 μl sample was collected from the donor and receiver sides using the sampling syringe. Sampling was done every 30 min for two hours, then every hour for 8 h, and finally every 2 h to complete 24 h. Samples were tested in triplicate for absorbance of tartrazine molecules at 425 nm using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader alongside a concentration ladder. Concentration values were normalized to initial donor concentrations.

Cell seeding and viability in the DCB

Porous EShell scaffolds were coated with 3 μg/cm2 fibronectin (bovine plasma, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at 37°C for 12 h to facilitate cell attachment (Lembong, Lerman, Kingsbury, Civin, & Fisher, 2018). Complete coating of the 3D structure was assured by pipetting the fibronectin back and forth through the scaffold and rotating every 30 min. The coated scaffolds were seeded with mouse fibroblasts (L929s, ATCC, Manassas, VA) with 10000 cells/cm2 for 4 h. The scaffolds were then inserted into DCB chambers and into simplified closed setups using the rotary pump, that differ from the previous setups just in the removal of sampling syringes from the loop. This setup was evaluated without a membrane (n=4). Controls were cultured statically on 12-well plates (2D) and on coated scaffolds (3D), at the same density. Both lines (labeled A and B) of the bioreactor were filled with L929 growth media consisting of minimum essential medium (MEM, Life Technologies, Frederick, MD) supplemented with 10% horse serum (ATCC), and ran for 7 and 28 d at 4 ml/min. Fresh growth media was replaced in reservoirs A and B every 2 d. At the end-point, culture viability in the DCB was assessed by imaging scaffolds on a bright-field microscope (Axiovert 40CFL, Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) fitted with a digital camera (SPOT Insight 1120, Diagnostics Instr., Sterling Heights, MI) at 2x.

Adipogenic differentiation in the DCB across the keratin membrane

As before, 3D printed EShell scaffolds were coated with a 3 μg/cm2 fibronectin solution at 37°C for 12 h. The scaffolds were then seeded with human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs, Lonza, Walkersville, MD) with 5000 cells/cm2. Control hMSCs were cultured statically on 12-well plates (2D) and on coated scaffolds (3D), at the same density. The seeded scaffolds were loaded into DCB chambers and into simplified closed loop setups using the rotary pump at 4 ml/min. This setup was evaluated without a membrane, with LCD, or with HCD membranes (at least n=3). Both lines (labeled A and B) were filled with hMSC growth media (high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin 100 U/100 mg (P/S)). Fresh growth media was replaced in both reservoirs and the controls every 2 d. After 7 d, once the controls reached ≥90% confluence, the scaffolds in the DCB were assumed ready for differentiation. The media in line A was replaced with hMSC adipogenic media (DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% 100 U/100 mg P/S, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 μM dexamethasone, 10 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), and 200 μM indomethacin)(Wexler et al., 2003; Z. Yang, Schmitt, & Lee, 2011), while line B was filled with hMSC growth media. Media in both lines was refreshed every 2 d for 21 d. After, cells were lifted by continuously pipetting trypsin through the scaffolds, and re-seeded on white 96-well plates for 12 h; controls were also lifted and re-seeded. Adipogenic differentiation of hMSCs in DCBs and controls was assessed using fluorescent AdipoRedTM Assay Reagent (Lonza) to quantify intracellular lipid accumulation (n=5).

Statistics

ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple pairwise comparison (significance using p < 0.05) were used for multi-group comparisons in Minitab 18 (Minitab, Inc). Differences between individual groups and references were assessed with two-sample t-test for the mean (significance using p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.05 (*)). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results and Discussion

The goal of this work was to assess the viability of our DCB for co-culturing adjacent cell populations with the inclusion of a regulatory keratin membrane. As illustrated in Figure 1B, we hypothesized that including a membrane in the DCB’s common chamber can regulate flow profiles and the separation of cell populations without impeding molecular diffusion for intercellular communication. Simply, we aim to keep cell populations separated but able to communicate with each other. The DCB (Figure 1C) provides two parallel flow lines into and out of a common chamber. The inclusion of a membrane limits mixing and convective flow between lines, and regulates diffusive transport depending on its crosslinking degree (CD) (Navarro et al., 2019).

Bioreactors are used to stimulate tissue-specific constructs with mechanical cues such as cyclic compression (Démarteau et al., 2003), tensile strain (Toume, Gefen, & Weihs, 2016), or shear stress (Nakagawa et al., 2013; Scheper, 2009; Stoffel et al., 2017). Additionally, flow orientation has been used to form gradients of cells, oxygen, or biomolecules in these constructs (Giusti et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2014; Lozito et al., 2013; Spitters et al., 2013). Other bioreactors rely on transport between two compartments to induce oriented flow or specific shear stress profiles on cells (6607910 B1, 2003; Nakagawa et al., 2013). For our DCB, the two adjacent chambers were designed to harbor cells, and the setup was engineered to hold a membrane to regulate the flow profiles in the system. As we aim to keep cell populations separated but communicating, we have characterized the transport phenomena in the DCB to prove that the balance between convective and diffusive transport can be used to alter the exchange of biochemical molecules.

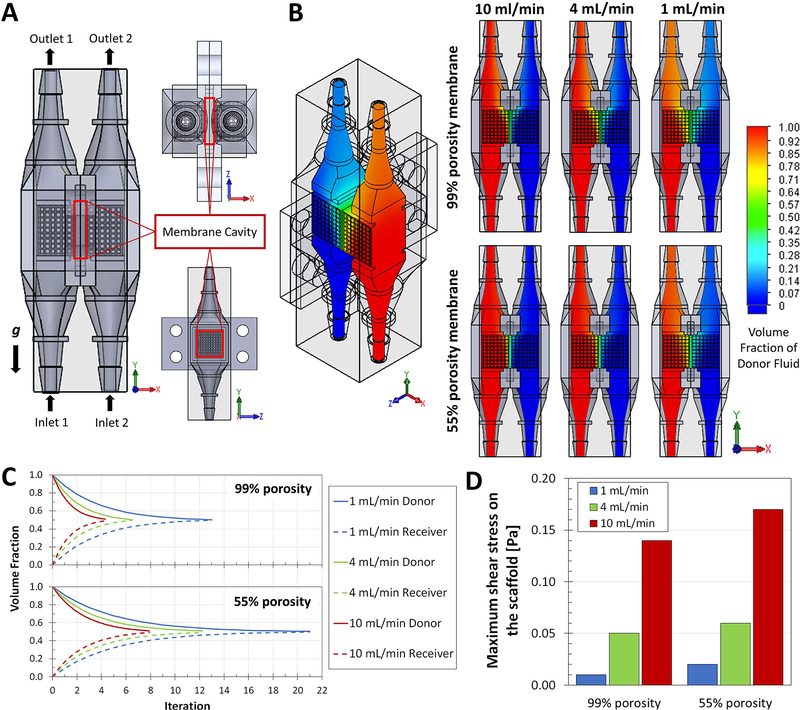

CFD modeling of the DCB membrane system

The CFD modeling sought to test if the convection and diffusion patterns hypothesized were possible in a DCB-membrane complex (Figure 2A). The simulations produced heat maps of the volume fraction of donor (red) and receiver (blue) fluids for different combinations of membrane porosity (55 or 99%) and inlet flow rate (1, 4, or 10 ml/min). Using the volume fraction, a quantification of the amount of a fluid in a mixture volume, it was possible to observe the mixing profiles of the donor and receiver fluids. The heat maps (Figure 2B) provide an idea of the mixing degree when the simulation reaches steady state. These qualitatively show that, independent to flow rate, the inclusion of a 55% porosity membrane reduces the mixing of the fluids when compared to a 99% porosity case (our model of a non-membrane case). To recapitulate the effects of looped flow, the outlet results were input back into the inlets until an equilibrated mixing state was reached (1:1 concentration of donor and receiver fluids in both chambers). As seen in Figure 2C, the mixing profiles show the iteration, proportional to time, when the DCB reaches concentration equilibrium, and show that as flow rate increases the system reaches this state faster. Including a membrane dilates the time required for the system to reach equilibrium, independent to flow rate. A 55% porosity membrane will increase the time required to reach equilibrium by 62% at 1 ml/min, 88% at 4 ml/min, and 84% at 10 ml/min. This indicates that mixing periods in the DCB can be tuned using flow rate and membrane porosity.

Figure 2.

CFD modeling of the DCB membrane system. A) CAD model for the proposed DCB system with porous scaffolds inserted in the line chambers, detailing the position of the inlets (1 and 2) and the outlets (1 and 2) and the orientation with respect to gravity; the membrane cavity houses the barrier between the two lines. B) Resulting heat maps of the volume fraction of Donor Fluid (red) and Receiver Fluid (blue), both with the identical properties of water, within the DCB for combinations of membrane porosity (55 or 99%) and inlet flow rate (1, 4, or 10 ml/min). Once stable, the simulations indicate different profiles of mixing at the interface of the two flow lines and the membrane. C) The volume fractions for Donor and Receiver Fluids at every normalized iteration point (proportional to time) were plotted to create mixing profiles as functions of porosity and flow rate; these profiles indicate the point in time, relative to the other cases, were the DCB systems reach concentration equilibrium (complete mixing defined as the point with 50±1% Donor Fluid and 50±1% Receiver Fluid). The inclusion of a membrane in the system dilates the time required for the looped system to reach equilibrium, at all follow rates simulated. D) CFD simulations were used to calculate the maximum shear stress on the surface of the scaffolds (local mesh); decreased porosity increases the resistance within the system and causes regions or points with higher shear stress as flow rate increases. These stress values allowed us to select adequate flow rates for subsequent experiments in the DCB that involve cells growing within the chambers.

The idea of using a membrane is comparable to other systems reported before. Giusti et al. (Giusti et al., 2014) proposed a similar two-chamber modular bioreactor with an intermediate cell-laden membrane to study intestinal epithelium and solute transport across the cell barrier. Here, time and flow determine the permeability degree of the growing cell barrier; in our DCB, time and flow determine the mixing degree between chambers. Multiple bioreactors have been designed to use flow to induce gradients and include membranes in some way; the Giusti (Giusti et al., 2014) and Nakagawa (Nakagawa et al., 2013) bioreactors use the membrane as the cell substrate to study, while the Dimitrijevich (6607910 B1, 2003) system can either use the membrane as the substrate or as a barrier to keep a cell-laden scaffold in place. In the DCB the role of the membrane is to determine the flow profile, aiming to balance convective and diffusive transport to regulate the biochemical cues stimulating the adjacent cell populations. It should be stated that any porous membrane could be used for this purpose in the DCB. Here, we chose to implement keratin hydrogels (Figure 3A) for this purpose because we have developed a method to alter its crosslinking degree by regulating the amount of energy delivered to the sample during crosslinking (Navarro et al., 2019, 2018). This gave us the possibility to study regulation of communication in the bioreactor by changing the properties of the membrane, properties that we ourselves could design, control, and manufacture as described in our previous studies.

Figure 3.

Assessment of diffusion in the DCB. A) UV-crosslinked keratin membranes casted in custom 3D printed molds. B) DCB master parts ready for assembly, highlighting the inclusion of the keratin membrane and the silicone sealing gaskets. C) For the assessment of diffusion in the DCB inlets and outlets were clamped shut, and sampling ports (red arrows) were opened on each side and sealed with casted paraffin plugs as needed. This system was used to quantify diffusion of model molecules tartrazine and brilliant blue from a donor chamber to a receiver chamber either without an intermediate membrane (D), with a LCD membrane, or with a HCD membrane (E-F) D) Without a membrane, diffusion quickly equilibrates the common chamber, with no significant difference between the concentration of the donor and the receiver chambers by 10 min, for both molecules tracked (n=4). E-F) The inclusion of the membrane significantly delays the equilibrium of the system; equilibrium for both tartrazine (534 Da) and brilliant blue (793 Da) takes at least 6105 min using a LCD membrane (n=4) and 4770 min using a HCD membrane (n=5). Tartrazine reaches equilibrium close to 0.5 (normalized concentration) between donor and receiver, but brilliant blue, which is 33% larger, is significantly and consistently stable around 0.8. G) The permeability of the system was around 2×10−4 cm2/s with no significant difference between the combinations of molecules and membrane CD. H-I) The keratin membranes recovered from the chambers showed differences between the low and high CD groups; LCD membranes were fully or partially dissolved, while the HCD samples were in considerable better state with some complete samples even after 8d. For all plots, statistical significance was determined as p<0.01 (**) or p<0.05 (*).

The CFD simulation results were also used to track shear stress in the DCB (Figure 2D). The maximum shear stress points were found at the inlets and outlets for all flow rates studied (Supplementary Figure S1). The outlets were also the points where the highest velocities were reported at all flow rates (Supplementary Figure S2). Decreasing the porosity of the membrane model (increasing the barrier effect) results in an increase in maximum shear stress values. We can assume that decrease in porosity slightly increases the resistance within the system and causes increments in shear stress as flow rate increases. These stress values allowed us to select adequate flow rates for subsequent experiments involving cells. Research on the effects of shear stress on hMSCs has reported that the threshold shear stress value for osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs is about 0.9 Pa (9 dynes/cm2) and the adhesion strength for MSCs is between 0.6 and 1.5 Pa (Dong et al., 2009; Hung, Babalola, & Bonassar, 2013; Yourek, McCormick, Mao, & Reilly, 2010). The average shear stress values in the DCB, including the porous scaffolds, are below 0.38 Pa (Supplementary Figure S1) and the maximum shear stress value registered on the scaffolds was 0.17 Pa. All cases simulated have adequate mixing profiles with and without the membrane in the DCB with scaffolds and are expected to provide a shear environment that sustains cell adhesion and development. It is worth noting that the CFD model implemented does not account for pulsatile flow, it is a unidirectional parallel flow simulation that does not include fluctuations in pressure. Our DCB system is perfused using a peristaltic multi-channel rotary pump (4 or 8-channel pump head), which inherently generates a pulsatile flow. The low scales of velocity, pressure, and shear stress that we used the DCB in allow us to neglect such pulsation effect in the bulk CFD simulation, although it should be noted as a potential limitation when directly comparing the computational and experimental data.

Assessment of diffusive and convective transport within the DCB

To understand and characterize the transport phenomena in the DCB, static and dynamic variations of the bioreactor were set up to quantify the role of diffusion, convection, and coupled convection-diffusion in the transport of small molecules. Diffusion was assessed without flow using a modified setup with sampling ports (Figure 3B–C) by tracking the concentration changes of model molecules tartrazine and brilliant blue in the donor and receiver chambers. For all the transport studies we defined reaching equilibrium as the point when there is no significant difference between the concentrations of the donor and the receiver (p<0.01 (**) or p<0.05 (*)). Without a membrane, diffusion equilibrates the concentration of both chambers, with no significant difference between the donor and receiver chambers by 10 min (Figure 3D). Yet, using LCD or HCD membranes significantly delays the equilibrium of the system (Figure 3E–F). Both tartrazine, with molecular weight of 534 Da, and brilliant blue, 793 Da, are diffused for at least 6100 min across LCD membranes before reaching equilibrium. The HCD membrane seemingly allows a higher rate of diffusion, equilibrating both molecules by 4800 min. Nevertheless, all combinations of molecules and membranes resulted in permeability close to 3.8×10−6 cm2/s, with no significant differences between the CD groups for both molecules (Figure 3G). The membranes recovered at the end of the diffusion assay showed LCD samples were either partially damaged or completely degraded after 8d. On the other hand, HCD samples appeared complete after initial examination; at worst, parts were broken and remained in the scaffold when they were lifted (Figure 3H–I).

The lack of difference in permeability between LCD and HCD membranes was not discouraging. We had previously characterized the keratin-based membranes in a Transwell model (Navarro et al., 2019). Then, our studies used fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (FITCd) with 10, 150, and 2000 kDa molecular weight (MW), and here we used molecules with 0.5 and 0.8 kDa MW. Previously we observed that as the size of the transported molecules decreased, the difference between transport across LCD or HCD membranes significantly disappeared. Then, for low MW molecules (10 kDa) higher amounts of solute were accumulated in the keratin gel, indicating that the smaller molecules could be chemically or electrostatically interacting with the crosslinked networks or were trapped within pores of the hydrogel(Navarro et al., 2019). The higher MW molecules had significantly different permeability when diffusing across LCD or HCD membranes, but there was no significant difference in permeability calculated for low MW FITCd across LCD (2.6×10−5 cm2/s) and HCD (3.3×10−5 cm2/s) membranes, respectively (Navarro et al., 2019). Here, our data with even smaller molecules compliments that trend, as there is no difference in the permeability of low MW tartrazine and brilliant blue across LCD or HCD membranes when implemented in the DCB.

Convection was assessed by characterizing the bulk flow downstream using the dynamic setup of the DCB (Figure 4A–B). The downstream reservoir volumes were tracked over 24 h and at all flow rates tested, independent of using no membrane, LCD, or HCD membranes, the volume of the donor and receiver reservoirs did not significantly change (not significantly different from 0% change). This consistency is indicative of either the convection transport in the two flow lines being independent and in steady state, or the system being symmetrical. The first option would state that the fluid in each line remains in its original line and does not change the volume of the loop over time. The symmetry option would indicate that even if one line is pulling flow from the other, the system pressures correct this and pull flow in the other direction so that the overall volume of the looped lines remains constant. From the CFD velocity trajectories in the DCB (Supplementary Figure S2) we can get a qualitative idea of how the flows remain fully developed across the common chamber and the porous scaffolds without crossing or interfering with the adjacent line when the intermediate membrane is included. But without a membrane (99% porosity equivalent) the flow lines mix at the interface and are hard to distinguish from each other. It is the membrane that restricts convection between the chambers. Still, as a symmetrical system the DCB that can be viable option to produce gradients, which require mixing, as hypothesized. Overall, our results indicate that convection in the system is not solely responsible for transport between chambers. To further elucidate on this, we proceeded to assess the coupled diffusive-convective transport of the main chamber under dynamic conditions.

Figure 4.

Dynamic assessment of convection and diffusion in the DCB system. A) The DCB flow system is composed of a multi-channel rotary pump (4 or 8-channel pump head) in sequence with the parallel chamber inlets, outlets, 3-way connectors to a 1 ml syringe for sampling, and 50 ml reservoirs. B) Flow and mixing profiles in the DCB can be observed by flowing green dye through one of the lines (donor side) and water through the other (receiver side); i) at the beginning the flow dynamics of the system keep the flows separated, then as time progresses ii) donor fluid can be seen moving to the adjacent receiver line. To understand and characterize this movement, this dynamic bioreactor setup was used to quantify the role of convection and coupled convection-diffusion in the transport of dye molecules from the donor to the receiver. C) The change in volume of the loops after 24h running was used to assess bulk convection; at all flow rates tested, and independent of the use of membranes, the volume of the donor and receiver reservoirs did not significantly change (not significantly different from 0% change) indicating that convection in the flow system is symmetrical and stable throughout the pump runs (at least n=4). D) Having studied diffusion and convection separately, concentration of green dye in the donor and receiver were measured thoroughly over 24 h runs to assess both transport phenomena coupled together, at 1, 4, and 10 ml/min. The first assessment was of an ideally impermeable barrier (ParafilmTM) setup, which indicated that the DCB flow lines remain completely independent from each other, as the concentration in the donor and receiver lines remain unchanged over time (donor not significantly different from 1.0 concentration, and receiver not significantly different from 0.0). For all plots, statistical significance was determined as p<0.01 (**) or p<0.05 (*).

The simultaneous effect of coupled convection and diffusion was assessed by tracking the changes in concentration of the donor and receiver chambers over 24 h in dynamic runs. With an impermeable Parafilm™ barrier between the chambers, the concentration in the donor and receiver lines remains constant; throughout the 24h, the donor is not significantly different from the 1.0 initial normalized concentration, and the receiver not significantly different from 0.0 (Figure 4D). This indicates, beyond statistical significance, that independent parallel flow lines can be produced in the DCB if needed. The opposite case involved running the DCB without a membrane, where equilibrium was reached within 24h at 4 ml/min (at 12h) and 10 ml/min (8h), but no ideal state of equilibrium was reached at 1 ml/min (Figure 5A). This is a significant change from considering diffusion only (Figure 3D), when equilibrium occurred within 10 min for all cases. When membranes are used, there are significant changes in the equilibrium time points. Using LCD membranes, equilibrium was reached within 24h only under 10 ml/min flow (at 8h) while no equilibrium was reached using 1 or 4 ml/min (Figure 5B). Using HCD membranes, the state of equilibrium was not reached at any flow rate within 24h (Figure 5C). In general, the inclusion of a membrane significantly delays the equilibrium of the system, which indicates that membranes can change mixing and transport dynamics between the chambers. All groups presented equilibrium of tartrazine at a concentration ratio close to 1:1 donor:receiver (0.5/0.5) or had trends that indicated eventual equilibrium at that ratio. We observed this behavior in the static diffusion assay as well, indicating that the diffusion equilibrium is conserved under dynamic conditions and dilated due to the convection component.

Figure 5.

Assessment of coupled convection-diffusion in the DCB system. As a continuation of Figure 4, the concentration of green dye in the donor and receiver were measured thoroughly over 24 h runs, studying the cases A) without a membrane, B) with LCD membranes, and C) with HCD membrane. From the concentration profiles it is possible to determine the points in time when the donor and receiver reach equilibrium (at least n=4). For the no-membrane cases, equilibrium was reached within 24h at 4 ml/min (at 12h) and 10 ml/min (8h), but no equilibrium was reached at 1 ml/min. The inclusion of the membrane significantly delays the equilibrium of the system; for the case with LCD membrane equilibrium within 24h only using 10 ml/min (8h), while no equilibrium was reached at 1 or 4 ml/min; last, with HCD membrane no state of equilibrium was reached for any rate within 24h. D) The state in which the membranes were recovered after these dynamic studies was determined by the CD; at all flow rates, the LCD membranes recovered were generally in further states of dissolution compared to the HCD samples. For all plots, statistical significance was determined as p<0.01 (**) or p<0.05 (*).

As compartmentalized in the diffusion-only and convection-only assessments, our coupled data indicate that convection in the system is not solely responsible for transport between the chambers, and the membrane and flow rates are the main regulators of this behavior. This observation is comparable to others reported in literature. Spitters et al. (Spitters et al., 2013) developed a bioreactor that provides cyclic compression to a two-compartment system divided with the tested sample (no membrane); the system forms gradients across the sample by regulating the concentration at each compartment, a fact also proven using CFD. The bioreactor creates glucose gradients due to diffusion across the samples and not only by convective flow from the main chambers. Our observations are similar to Spitters’ et al.; the transport between compartments does not involve convective flow forced from one chamber to another, but rather perpendicular diffusion stemming from the bulk convective transport. Other bioreactors that rely on transport between chambers have included membranes. Nakagawa et al. (Nakagawa et al., 2013) reported a two-chambered microfluidic device used to produce platelets from megakaryocytes, inducing shear stress on a cell-laden membrane by having one side flow parallel to the membrane plane (main flow) and the other providing 60° inflow across the membrane (pressure flow). Here, the direction of the pressure flow was used to induce convective flow across the barrier, a behavior we avoided in the DCB by maintaining the flow lines parallel. In a similar system by Dimitrijevich et al. (6607910 B1, 2003), the main direction of inlet flow is perpendicular to the membrane plane, but relies on the fluid following the membrane surface and flowing back parallel to the inlet. In this case the flow is first perpendicular and then parallel to the membrane, which the inventors use to induce shear stress and perfusion by convection and diffusion across a membrane to cells on the other side. Overall, the transport in our DCB is determined by the CD of the membrane, flow rates, and the orientation of flow but, as other bioreactors in literature prove, these factors can be changed and combined to induce different transport profiles as needed.

An important difference between the dynamic cases assessed used was the state of the hydrogel membranes recovered. At all flow rates, the LCD membranes recovered were generally in worse state compared to the HCD samples, presenting higher stages of dissolution (Figure 5D). This trend confirms (1) the observations in the diffusion-only cases, where HCD samples appeared complete after initial examination and only broke when the membranes were lifted from the scaffolds (Figure 3H–I), and (2) our previous observations on the faster degradation and loss of swelling capacity of LCD membranes (Navarro et al., 2019). Under coupled convection-diffusion transport of the DCB, HCD membranes will provide a more reliable barrier effect over prolonged periods of time. Overall, we have confirmed that the DCB membrane system allows transport of molecules from one chamber to another, and thus potential intercellular communication between adjacent cell populations, via diffusion through a permeable barrier, a phenomenon that can be further regulated over time by changing the CD of the membrane used.

Cell cultures, growth, and differentiation within the DCB

The DCB system was optimized for assembly under sterile conditions and for use inside an incubator for at least 28 d, using a 4 ml/min flow rate in all cases (Figure 6A–B). Seeding the fibronectin-coated scaffolds with cells, we were able to study, first, if the DCB sustains cell growth using a fast proliferating cell line such as L929 fibroblasts that could answer question in a shorter period of time, and, second, if we could induce changes on one population using transport of biomolecules from the adjacent line using a common hMSC population can be purposefuly differentiated using supplemented media. Using the same type of cells, L929 fibroblasts, and same type of growth media in both lines for 7 and 28d, microscopy imaging of the scaffolds revealed healthy colonies of cells on both chambers of the DCB (Figure 6C). As observed previously in literature, the preferential localization of cells in concave curvatures or negative curvature substrates (Lembong et al., 2018) is indicative of healthy populations within the bioreactor for at least 28d. As previously discussed, we had concerns about shear stress lifting adhered cells. Here we confirm cell attachment to the porous scaffolds in the DCB and further development under a 4 ml/min flow rate, which CFD modeling indicates causes maximum shear stress of 0.065 Pa with a 55% porosity barrier (Figure 2D).

Figure 6.

Cell cultures, growth, and differentiation within the DCB. A) The DCB system was simplified to reduce connections and ports that could lead to contamination; for cells studies that require incubation, the loops consist of the multi-channel rotary pump (4 or 8-channel pump head) in sequence with the parallel chamber inlets, outlets, and 50 ml reservoirs. B) Fibronectin-coated scaffolds were successfully seeded and proved to be manageable under sterile conditions for assembly into the DCB. C) L929 fibroblasts were cultured on both lines A and B for 7 and 28d; imaging of the scaffolds revealed that cells were healthy and growing, filling the concave curvatures of the pores, for at least 28d in the DCB (n=4). D) Fibronectincoated scaffolds were seeded with hMSCs and grown in the bioreactor using hMSC growth media. After 7d, line A was changed to hMSC adipogenic media, while line B was kept with hMSC growth media for up to 28d; notice the different shades of media in the two lines (red arrows). E) Adipogenic differentiation was possible in the DCB for all cases studied, quantified by the normalized amount of lipids deposited as compared to a 2D non-differentiated population. Without a membrane, line B did differentiate but to a significantly lower degree compared to the direct differentiation of line A, the same trend presented in the LCD case. For the HCD membrane case, both lines were able to deposit similar amounts of intracellular lipids. Comparisons were done using ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple pairwise comparison; samples that do not share the same letter are significantly different (p<0.05).

Next, by using to two different media on the same type of cells, hMCSs, we were able to confirm that the bioreactor system allows biomolecular diffusion between its chambers. Perfusing line A with adipogenic media and line B with regular growth media, we assessed diffusion of adipogenic factors by quantifying intracellular lipids deposited by hMSCs in both lines as compared to a 2D non-differentiated population (normalized lipid deposition of 1.0). Due to sustained diffusion between the chambers, the line without adipogenic media still received adipogenic factors and differentiated in all combinations studied. Without a membrane, hMSCs in line B did differentiate but to a significantly lower degree compared to the direct differentiation of cells in line A (different normalized lipid deposition of 13.8 ± 0.1 in line A vs. 8.15 ± 2.3 in line B, p<0.05). The same trend was observed when using LCD membranes (different normalized lipid deposition of 7.9 ± 1.0 in line A vs. 4.9 ± 0.6 in line B, p<0.05). Differently, for the HCD membrane cases, there was no significant difference in the amount of intracellular lipids deposit by both lines (normalized lipid deposition of 7.7 ± 1.2 in line A and 5.8 ± 0.8 in line B) (Figure 6E). We have confirmed that a keratin-based membrane in the DCB allows diffusion of, at least, adipogenic factors. Even though the DCB had less lipid deposition than control scaffolds, with the static 3D cultures having significantly higher lipid deposition than the studied groups (p<0.05), it is important to highlight that the 2D and 3D controls can only be sustained with a single type of media. The DCB was successful differentiating hMSC populations indirectly and under dynamic conditions. These results are encouraging, they indicate that the DCB approach allows co-culturing cells lines simultaneously without abandoning their specific growth or differentiating media, and we aim to extend this to other co-culture setups.

Our stratification approach using the DCB and membranes to separate populations while allowing transport communication will provide an interesting platform to study the development and relations of dermis-hypodermis layers. We are interested in studying the role of the hypodermis layer and its adipose-specific ECM (mostly collagen types I, III, IV, V, and VI (Kang et al., 2009)) and adipose-specific growth factors and hormones (Jin et al., 2015; Kolarsick et al., 2011; Salathia et al., 2013; Shibata et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2016) in skin healing processes. If the hypodermis is producing such factors in vivo, diffusion through the tissues and convection through the common deep vascular plexus is transporting them to the adjacent dermis layer. In order to implement our DCB, which only has two lines, we restrict our model to the dermis and hypodermis due to this interesting transport and communication potential between the two. Skin also includes the epidermis and future models should aim to study communication between the three layers. Here, the DCB system will allow us to replicate transport between hypodermis and dermis to prove the benefits of stratification and co-culturing in skin tissue engineering.

The study of gradients and stratification has been well documented for tissues like the muscle-ligament-bone complex (B. S. Kim et al., 2014; Lu, Subramony, Boushell, & Zhang, 2010; Merceron et al., 2015; G. Yang et al., 2016), osteochondral tissue (Camarero-Espinosa et al., 2016; Di Luca, Van Blitterswijk, & Moroni, 2015; Harley et al., 2009; Levingstone et al., 2016; Mosher et al., 2015; Spalazzi et al., 2006), or thin epithelial barriers such as the epidermis/dermis (Asano et al., 2017; Matsusaki et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2015), or gastrointestinal tissues (Nishiguchi et al., 2011; Pi et al., 2018). Most approaches are based on when and where cells are deposited on scaffolds to improve their chances of forming layers or gradients. Several gradient formation techniques rely on cell migration from one layer to the other, either following or leaving behind a gradient trail of ECM or growth factors (Harley et al., 2009; Merceron et al., 2015; Sant, Hancock, Donnelly, Iyer, & Khademhosseini, 2010). Multichambered bioreactors have studied intercellular communication between different types of cells with various results. Fisher and coworkers used a tubular perfusion system to grow stem cell-laden alginate beads (Yeatts & Fisher, 2011; Yeatts et al., 2011). This approach increased surface area exposure to nutrients and oxygen, and each bead could be loaded with different cells with the potential of spatial control, although limited by the use of a single type of media (Nguyen et al., 2016). Chang et al. (Chang, Lin, Lin, Chou, & Liu, 2004), and a similar setup by Berry et al. (0212071 A1, 2015), use double-chamber bioreactors consisting of two glass chambers separated by a silicone-rubber septum that held a single scaffold. This setup could supply two types of culture media to support different cell types on each half of the scaffold and transport of media factors across the scaffold created a gradient for the migration of cells. Similarly, the Tuan group (Lin et al., 2014; Lozito et al., 2013) developed a double chambered bioreactor that allowed constant communication across a bilayered scaffold (no membrane). In this case, each side of the bioreactor held a different scaffold, with substrate and cells specific to either bone or cartilage for osteochondral tissue engineering. The scaffolds remained homogeneously different, but diffusion and the gradient deposition of ECM bound them together developing a tidemark after 6 weeks in the bioreactor. Our DCB approach aims to regulate cell migration and communication with the inclusion of the membrane, allowing them when forming gradients or preventing them to create stratified layers.

Conclusions

Here we presented our dual-chambered bioreactor (DCB) design with the inclusion of degradable membranes for the stratification of cellular cultures. We have characterized the transport phenomena within the bioreactor to understand the effect of the design and the membranes in the potential formation of stratified layers or gradients. As detailed before, the DCB can provide adjacent flow lines within a common chamber; the inclusion of the membrane can regulate flow layering or mixing, which could be translated to stratification or gradients, respectively. The crosslinking degree of the membranes not only regulates the permeability properties of the network but can be used to change convection and diffusion in the bioreactor. Our data suggest that the DCB can perfuse two adjacent layers with different media, allowing communication between the layers via diffusion through the membrane. Furthermore, the bioreactor is viable for co-culture and sustaining of adjacent cell populations, indicating that cross-talk between the populations can be used to induce changes on one another.

Our overall approach to study the dermis-hypodermis complex in a bioreactor system aims to address current limitations in skin tissue engineering, but it can be used for other multilayered tissues such as blood vessels or gastrointestinal tissues. As a bioreactor it can be implemented to study 3D co-cultures and communication pathways between cell populations. We consider the system has applications in cellular biology, tissue engineering, or fluid dynamics research, as well as broader application in industry for cellular or bacterial co-cultures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration of KeraNetics, LLC, as the providers of raw keratin material used here. This research was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NIH) Center for Engineering Complex Tissues (P41 EB023833). The authors thank the Fulbright Scholars Program (Colciencias – Fulbright) (JN), as well as the Department of Bioengineering’s Fischell Fellowship in Biomedical Engineering (JN) and the SEEDS Undergraduate Research program (JS) at the University of Maryland.

Grant/Funding Information: NIBIB/NIH grant - P41 EB023833

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: JN, JS, MJ, MS, AM and JPF declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arumugasaamy N, Navarro J, Kent Leach J, Kim PCW, & Fisher JP (2018). In Vitro Models for Studying Transport Across Epithelial Tissue Barriers. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 10.1007/s10439-018-02124-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano Y, Shimoda H, Okano D, Matsusaki M, & Akashi M (2017). Transplantation of three-dimensional artificial human vascular tissues fabricated using an extracellular matrix nanofilm-based cell-accumulation technique. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 11(4), 1303–1307. 10.1002/term.2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JL, Wick TM, Murphy-Ullrich J, Penman AD, Cain AW, & Rixse A (2015). 0212071 A1. United States Patent.

- Böttcher-Haberzeth S, Biedermann T, Reichmann E, Bo S, Biedermann T, & Reichmann E (2010). Tissue engineering of skin. Burns, 36(4), 450–460. 10.1016/j.burns.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarero-Espinosa S, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Weder C, & Foster EJ (2016). Directed cell growth in multi-zonal scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials, 74, 42–52. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Lin FH, Lin CC, Chou CH, & Liu HC (2004). Cartilage tissue engineering on the surface of a novel gelatin-calcium- phosphate biphasic scaffold in a double-chamber bioreactor. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part B Applied Biomaterials, 71(2), 313–321. 10.1002/jbm.b.30090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PF, Vaquette C, Zhang Q, Reis RL, Ivanovski S, & Hutmacher DW (2014). Advanced tissue engineering scaffold design for regeneration of the complex hierarchical periodontal structure. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 41(3), 283–294. 10.1111/jcpe.12214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussler EL (2009). Diffusion, Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 10.1017/CBO9780511805134.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Démarteau O, Wendt D, Braccini a., Jakob M, Schäfer D, Heberer M, & Martin I (2003). Dynamic compression of cartilage constructs engineered from expanded human articular chondrocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 310(2), 580–588. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Luca A, Van Blitterswijk C, & Moroni L (2015). The osteochondral interface as a gradient tissue: From development to the fabrication of gradient scaffolds for regenerative medicine. Birth Defects Research Part C - Embryo Today: Reviews, 105(1), 34–52. 10.1002/bdrc.21092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevich D, Dodd CW, Anderson WJ, & Schwarz RP (2003). 6607910 B1. United States Patent.

- Dong J. De, Gu YQ, Li CM, Wang CR, Feng ZG, Qiu RX, … Zhang J (2009). Response of mesenchymal stem cells to shear stress in tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 30(5), 530–536. 10.1038/aps.2009.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti S, Sbrana T, La Marca M, Di Patria V, Martinucci V, Tirella A, … Ahluwalia A (2014). A novel dual-flow bioreactor simulates increased fluorescein permeability in epithelial tissue barriers. Biotechnology Journal, 9(9), 1175–1184. 10.1002/biot.201400004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleghorn JP, Lee CSD, Cabodi M, Stroock AD, & Bonassar LJ (2008). Adhesive properties of laminated alginate gels for tissue engineering of layered structures. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 85A(3), 611–618. 10.1002/jbm.a.31565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurkan UA, El Assal R, Yildiz SE, Sung Y, Trachtenberg AJ, Kuo WP, & Demirci U (2014). Engineering Anisotropic Biomimetic Fibrocartilage Microenvironment by Bioprinting Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Nanoliter Gel Droplets. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 11(7), 2151–2159. 10.1021/mp400573g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamuy R, Kinoshita N, Yoshimoto H, Hayashida K, Houbara S, Nakashima M, … Akita S (2013). One-stage, simultaneous skin grafting with artificial dermis and basic fibroblast growth factor successfully improves elasticity with maturation of scar formation. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 21(1), 141–154. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00864.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley BA, Lynn AK, Wissner-Gross Z, Bonfield W, Yannas IV, & Gibson LJ (2009). Design of a multiphase osteochondral scaffold III: Fabrication of layered scaffolds with continuous interfaces. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 9999A(3), NA–NA. 10.1002/jbm.a.32387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert TL, Wu X, Yu G, Goh BC, Halvorsen Y-DC, Wang Z, … Gimble JM (2009). Culture effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on cryopreserved human adipose-derived stromal/stem cell proliferation and adipogenesis. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 3(7), 553–561. 10.1002/term.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung BP, Babalola OM, & Bonassar LJ (2013). Quantitative characterization of mesenchymal stem cell adhesion to the articular cartilage surface. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part A, 101(12), 3592–3598. 10.1002/jbm.a.34647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin CE, Xiao L, Ge ZH, Zhan XB, & Zhou HX (2015). Role of adiponectin in adipose tissue wound healing. Genetics and Molecular Research, 14(3), 8883–8891. 10.4238/2015.August.3.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Gimble JM, & Kaplan DL (2009). In Vitro 3D Model for Human Vascularized Adipose Tissue. Tissue Engineering Part A, 15(8), 2227–2236. 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, Kim EJ, Choi JS, Jeong JH, Jo CH, & Cho YW (2014). Human collagen-based multilayer scaffolds for tendon-to-bone interface tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part A, 102(11), 4044–4054. 10.1002/jbm.a.35057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, & Kim GH (2015). 3D multi-layered fibrous cellulose structure using an electrohydrodynamic process for tissue engineering. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 457, 180–187. 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolarsick PAJ, Kolarsick MA, & Goodwin C (2011). Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin. Journal of the Dermatology Nurses’ Association, 3(4), 203–213. 10.1097/JDN.0b013e3182274a98 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lembong J, Lerman MJ, Kingsbury TJ, Civin CI, & Fisher JP (2018). A Fluidic Culture Platform for Spatially Patterned Cell Growth, Differentiation, and Cocultures. Tissue Engineering Part A, 24(23–24), 1715–1732. 10.1089/ten.tea.2018.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levingstone TJ, Ramesh A, Brady RT, Brama PAJ, Kearney C, Gleeson JP, & O’Brien FJ (2016). Cell-free multi-layered collagen-based scaffolds demonstrate layer specific regeneration of functional osteochondral tissue in caprine joints. Biomaterials, 87, 69–81. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Lozito TP, Alexander PG, Gottardi R, & Tuan RS (2014). Stem Cell-Based Microphysiological Osteochondral System to Model Tissue Response to Interleukin-1β. Molecular Pharmaceutics, 11(7), 2203–2212. 10.1021/mp500136b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozito TP, Alexander PG, Lin H, Gottardi R, Cheng A, & Tuan RS (2013). Three-dimensional osteochondral microtissue to model pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 4(Suppl 1), S6 10.1186/scrt367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HH, Subramony SD, Boushell MK, & Zhang X (2010). Tissue engineering strategies for the regeneration of orthopedic interfaces. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 38(6), 2142–2154. 10.1007/s10439-010-0046-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino T, Jinnin M, Muchemwa FC, Fukushima S, Kogushi-Nishi H, Moriya C, … Ihn H (2010). Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates the proliferation of human dermal fibroblasts via the ERK1/2 and JNK pathways. British Journal of Dermatology, 162(4), 717–723. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09581.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markeson D, Pleat JM, Sharpe JR, Harris AL, Seifalian AM, & Watt SM (2015). Scarring, stem cells, scaffolds and skin repair. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 9(6), 649–668. 10.1002/term.1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsusaki M, Fujimoto K, Shirakata Y, Hirakawa S, Hashimoto K, & Akashi M (2015). Development of full-thickness human skin equivalents with blood and lymph-like capillary networks by cell coating technology. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 103(10), 3386–3396. 10.1002/jbm.a.35473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa A, Matsusaki M, & Akashi M (2015). Construction of three-dimensional liver tissue models by cell accumulation technique and maintaining their metabolic functions for long-term culture without medium change. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part A, 103(4), 1554–1564. 10.1002/jbm.a.35292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty E, Hendry C, & Farley A (2012). The integumentary system: anatomy, physiology and function of skin. Nursing Standard, 27(3), 35–42. 10.7748/ns2012.09.27.3.35.c9299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merceron TK, Burt M, Seol Y-J, Kang H-W, Lee SJ, Yoo JJ, & Atala A (2015). A 3D bioprinted complex structure for engineering the muscle–tendon unit. Biofabrication, 7(3), 035003 10.1088/1758-5090/7/3/035003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CZ, Spalazzi JP, & Lu HH (2015). Stratified scaffold design for engineering composite tissues. Methods, 84, 99–102. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Nakamura S, Nakajima M, Endo H, Dohda T, Takayama N, … Eto K (2013). Two differential flows in a bioreactor promoted platelet generation from human pluripotent stem cell-derived megakaryocytes. Experimental Hematology, 41(8), 742–748. 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro J, Swayambunathan J, Lerman M, Santoro M, & Fisher JP (2019). Development of keratin-based membranes for potential use in skin repair. Acta Biomaterialia, 83, 177–188. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro J, Swayambunathan J, Santoro M, & Fisher J (2018). Assessment of the Effects of Energy Density in Crosslinking of Keratin-Based Photo-Sensitive Resin In 2018 IX International Seminar of Biomedical Engineering (SIB) (pp. 1–6). IEEE; 10.1109/SIB.2018.8467744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WL, Qi JTZ, Yeong WY, & Naing MW (2018). Proof-of-concept: 3D bioprinting of pigmented human skin constructs. Biofabrication. 10.1088/1758-5090/aa9e1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B-NB, Ko H, & Fisher JP (2016). Tunable osteogenic differentiation of hMPCs in tubular perfusion system bioreactor. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 113(8), 1805–1813. 10.1002/bit.25929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiguchi A, Yoshida H, Matsusaki M, & Akashi M (2011). Rapid construction of three-dimensional multilayered tissues with endothelial tube networks by the cell-accumulation technique. Advanced Materials, 23(31), 3506–3510. 10.1002/adma.201101787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papenburg BJ, Liu J, Higuera G. a., Barradas AMC, de Boer J, van Blitterswijk C. a., … Stamatialis D (2009). Development and analysis of multi-layer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials, 30(31), 6228–6239. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck M, Molnar J, & Swart D (2009). A global plan for burn prevention and care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(10), 802–803. 10.2471/BLT.08.059733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi Q, Maharjan S, Yan X, Liu X, Singh B, van Genderen AM, … Zhang YS (2018). Digitally Tunable Microfluidic Bioprinting of Multilayered Cannular Tissues. Advanced Materials, 30(43), 1–10. 10.1002/adma.201706913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placone JK, Navarro J, Laslo GW, Lerman MJ, Gabard AR, Herendeen GJ, … Fisher JP (2017). Development and Characterization of a 3D Printed, Keratin-Based Hydrogel. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 45(1), 237–248. 10.1007/s10439-016-1621-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salathia NS, Shi J, Zhang J, & Glynne RJ (2013). An in vivo screen of secreted proteins identifies adiponectin as a regulator of murine cutaneous wound healing. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 133(3), 812–821. 10.1038/jid.2012.374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant S, Hancock MJ, Donnelly JP, Iyer D, & Khademhosseini A (2010). Biomimetic gradient hydrogels for tissue engineering. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 88(6), 899–911. 10.1002/cjce.20411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper T (2009). Bioreactor Systems for Tissue Engineering. (Kasper C, van Griensven M, & Pörtner R, Eds.) (Vol. 112). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 10.1007/978-3-540-69357-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Tada Y, Asano Y, Hau CS, Kato T, Saeki H, … Sato S (2012). Adiponectin Regulates Cutaneous Wound Healing by Promoting Keratinocyte Proliferation and Migration via the ERK Signaling Pathway. The Journal of Immunology, 189(6), 3231–3241. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook B, Rivera Gonzalez G, Ebmeier S, Grisotti G, Zwick R, & Horsley V (2016). The Role of Adipocytes in Tissue Regeneration and Stem Cell Niches. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 32(1), 609–631. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-125426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobachkin A, & Dumnov G (2014). Numerical Basis of CAD-Embedded CFD. NAFEMS World Congress 2013, (February), 1–20. 10.1007/s10590-014-9157-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spalazzi JP, Doty SB, Moffat KL, Levine WN, & Lu HH (2006). Development of Controlled Matrix Heterogeneity on a Triphasic Scaffold for Orthopedic Interface Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering, 12(12), 061120052454001 10.1089/ten.2006.12.ft-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitters TWGM, Leijten JCH, Deus FD, Costa IBF, van Apeldoorn A. a, van Blitterswijk C. a, & Karperien M (2013). A Dual Flow Bioreactor with Controlled Mechanical Stimulation for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods, 19(10), 774–783. 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel M, Willenberg W, Azarnoosh M, Fuhrmann-Nelles N, Zhou B, & Markert B (2017). Towards bioreactor development with physiological motion control and its applications. Medical Engineering & Physics, 39, 106–112. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblyn S, Pettit Kneller EL, Walker SJ, Ellenburg MD, Kowalczewski CJ, Van Dyke M, … Saul JM (2016). Keratin hydrogel carrier system for simultaneous delivery of exogenous growth factors and muscle progenitor cells. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part B Applied Biomaterials, 104(5), 864–879. 10.1002/jbm.b.33438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toume S, Gefen A, & Weihs D (2016). Printable low-cost, sustained and dynamic cell stretching apparatus. Journal of Biomechanics, 49(8), 1336–1339. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Wang M, She Z, Fan K, Xu C, Chu B, … Tan R (2015). Collagen/chitosan based two-compartment and bi-functional dermal scaffolds for skin regeneration. Materials Science and Engineering C, 52, 155–162. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler SA, Donaldson C, Denning-Kendall P, Rice C, Bradley B, & Hows JM (2003). Adult bone marrow is a rich source of human mesenchymal “stem” cells but umbilical cord and mobilized adult blood are not. British Journal of Haematology, 121(2), 368–374. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R, Geyer S, Weninger W, Guimberteau JC, & Wong JK (2016). The dynamic anatomy and patterning of skin. Experimental Dermatology, 25(2), 92–98. 10.1111/exd.12832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Lin H, Rothrauff BB, Yu S, & Tuan RS (2016). Multilayered polycaprolactone/gelatin fiber-hydrogel composite for tendon tissue engineering. Acta Biomaterialia, 35, 68–76. 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Schmitt JF, & Lee EH (2011). Immunohistochemical Analysis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Differentiating into Chondrogenic, Osteogenic, and Adipogenic Lineages. In Methods (Vol. 698, pp. 353–366). 10.1007/978-1-60761-999-4_26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatts AB, & Fisher JP (2011). Tubular Perfusion System for the Long-Term Dynamic Culture of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods, 17(3), 337–348. 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatts AB, Gordon CN, & Fisher JP (2011). Formation of an Aggregated Alginate Construct in a Tubular Perfusion System. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods, 17(12), 1171–1178. 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yourek G, McCormick SM, Mao JJ, & Reilly GC (2010). Shear stress induces osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Regenerative Medicine, 5(5), 713–724. 10.2217/rme.10.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, & Michniak-Kohn BB (2012). Tissue engineered human skin equivalents. Pharmaceutics, 4(1), 26–41. 10.3390/pharmaceutics4010026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.