Abstract

2-(Phosphonomethyl)-pentanedioic acid (2-PMPA) is a potent (IC50 = 300 pM) and selective inhibitor of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) with efficacy in multiple neurological and psychiatric disease preclinical models and more recently in models of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and cancer. 2-PMPA (1), however, has not been clinically developed due to its poor oral bioavailability (<1%) imparted by its four acidic functionalities (c Log P = −1.14). In an attempt to improve the oral bioavailability of 2-PMPA, we explored a prodrug approach using (5-methyl-2-oxo-1,3-dioxol-4-yl)methyl (ODOL), an FDA-approved promoiety, and systematically masked two (2), three (3), or all four (4) of its acidic groups. The prodrugs were evaluated for in vitro stability and in vivo pharmacokinetics in mice and dog. Prodrugs 2, 3, and 4 were found to be moderately stable at pH 7.4 in phosphate-buffered saline (57, 63, and 54% remaining at 1 h, respectively), but rapidly hydrolyzed in plasma and liver microsomes, across species. In vivo, in a single time-point screening study in mice, 10 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent doses of 2, 3, and 4 delivered significantly higher 2-PMPA plasma concentrations (3.65 ± 0.37, 3.56 ± 0.46, and 17.3 ± 5.03 nmol/mL, respectively) versus 2-PMPA (0.25 ± 0.02 nmol/mL). Given that prodrug 4 delivered the highest 2-PMPA levels, we next evaluated it in an extended time-course pharmacokinetic study in mice. 4 demonstrated an 80-fold enhancement in exposure versus oral 2-PMPA (AUC0−t: 52.1 ± 5.9 versus 0.65 ± 0.13 h*nmol/mL) with a calculated absolute oral bioavailability of 50%. In mouse brain, 4 showed similar exposures to that achieved with the IV route (1.2 ± 0.2 versus 1.6 ± 0.2 h*nmol/g). Further, in dogs, relative to orally administered 2-PMPA, 4 delivered a 44-fold enhanced 2-PMPA plasma exposure (AUC0−t for 4: 62.6 h*nmol/mL versus AUC0−t for 2-PMPA: 1.44 h*nmol/mL). These results suggest that ODOL promoieties can serve as a promising strategy for enhancing the oral bioavailability of multiply charged compounds, such as 2-PMPA, and enable its clinical translation.

Keywords: 2-PMPA, glutamate carboxypeptidase II, oral bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, prodrugs

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII), which is also known as prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), N-acetylated-α-linked acidic dipeptidase (NAALADase), N-acetylaspartyl-glutamate (NAAG) peptidase, and folate hydrolase (FOLH1), is a type II extracellular membrane zinc metallopeptidase that catalyzes synaptically released N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) to form N-acetylaspartate (NAA) and glutamate in the nervous system.1,2 Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system (CNS), which has a crucial role in a complex communication network established between all residential brain cells.3 An excess release of glutamate leads to the activation of ionotropic and metabotropic receptors, resulting in the accumulation of toxic cytoplasmic Ca2+ and neuronal cell death, as observed in multiple neurological disorders like neuropathic pain,4–8 stroke,9 diabetic neuropathy,10–12 schizophrenia,13 addiction,14–16 multiple sclerosis,17–19 and traumatic brain injury.20,21 We and others have recently shown that GCPII is implicated in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),22–25 as well as in the preclinical model of ovarian cancer.26 Thus, GCPII inhibition represents a promising therapeutic target to treat a wide array of disorders.

Multiple GCPII inhibitors have been discovered and evaluated in preclinical models of neurological disorders.9,25,27–32 Potent GCPII inhibitors require two function-alities, namely, a glutarate moiety that binds the C-terminal glutamate recognition site of GCPII, and a zinc-binding group to engage one or both of the zinc atoms at the active site. However, the inclusion of these functional groups increases the hydrophilicity of the compounds leading to poor oral bioavailability and tissue penetration.29,33,34 2-(Phosphonomethyl)-pentanedioic acid (2-PMPA) is one such potent GCPII inhibitor (IC50 = 300 pM) with good selectivity and no activity at 100 different transporters, enzymes, and receptors, including several glutamate targets.31 2-PMPA has been found to be effcacious in multiple neurological disease models,8,9,35–40 ovarian cancer,26 and IBD41,42 and providing nephroprotection in PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate cancer.43 However, most of these studies required 2-PMPA administration via systemic intravenous and intra-peritoneal routes due to its poor pharmacokinetic (F <1%; AUCbrain/AUCplasma ratio <2%)44 properties, thus impeding its clinical development.

In an attempt to improve the oral bioavailability of 2-PMPA, we previously synthesized and characterized multiple prodrugs with distinct chemical structures.29 This led to the discovery of compound 21b with the isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl (POC) promoiety (tris-POC-2-PMPA) that resulted in a 20-fold enhancement in 2-PMPA systemic availability versus orally administered 2-PMPA in mice.29 Although these initial data were encouraging and substantiated the feasibility of our 2-PMPA prodrug strategy, further chemical optimization was pursued, to enhance 2-PMPA bioavailability and enable its clinical translation. Herein, we employed (5-methyl-2-oxo-1,3-dioxol-4-yl)methyl (ODOL) groups that were shown to successfully enhance oral absorption of FDA-approved drugs such as olmesartan and azilsartan medoxomil.45–47 We systematically masked two (bis-), three, (tris-), or all four (tetra-) acidic functional groups of 2-PMPA with the ODOL promoieties and evaluated the resulting prodrugs for in vitro stability and in vivo pharmacokinetics. Our best prodrug showed an increase in 2-PMPA oral exposure of 80- and 44-fold in mice and dogs, respectively.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis of 2-PMPA Prodrugs.

2-PMPA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Reagents such as liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS)-grade acetonitrile and water with 0.1% formic acid were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL). All chemicals for synthesizing ODOL prodrugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, TCI, or Combi-Blocks and used without further purification. Commercially available solvents, catalysts, and reagent-grade materials were used for the synthesis of the compounds described. TLC was performed on silica gel 60 F254-coated aluminum sheets (Merck). Flash chromatography was performed on silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063 mm, Fluka). 1H NMR spectra and 13C NMR spectra were measured at 401.0 MHz and 100.8 MHz, respectively. For standardization of 1H NMR spectra, internal signal of tetramethylsilane (TMS) (δ 0.0, CDCl3) or residual signals of CDCl3 (δ 7.26) or d6-CD3COCD3 (δ 2.17) were used. For 13C NMR spectra (APT experiments), a residual signal of CDCl3 (δ 77.16) or d6-CD3COCD3 (δ 207.07, 30.92) was used. Chemical shifts are given in δ scale (point of symmetry for symmetrical signals; shift range for unsymmetrical signals) and coupling constants J as Hz. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were recorded using a ZQ micromass mass spectrometer (Waters) equipped with an ESCi multimode ion source and controlled by MassLynx software. Low-resolution ESI mass spectra were recorded using a quadrupole orthogonal acceleration time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (Q-Tof micro, Waters) and high-resolution ESI mass spectra using a hybrid FT mass spectrometer combining a linear ion trap MS and the Orbitrap mass analyzer (LTQ Orbitrap XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The conditions were optimized for suitable ionization in the ESI Orbitrap source (sheath gas flow rate 35 au, aux gas flow rate 10 au of nitrogen, source voltage 4.3 kV, capillary voltage 40 V, capillary temperature 275 °C, tube lens voltage 155 V). Samples were dissolved in methanol and analyzed by direct injection. Purity of all compounds subjected to biological testing was over 95%, unless otherwise noted.

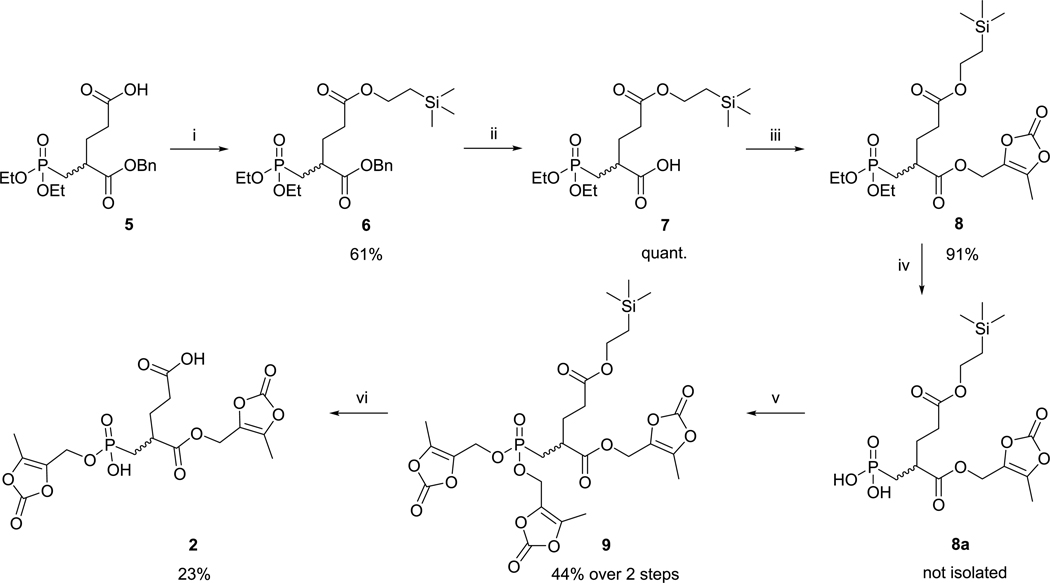

Prodrugs 2, 3, and 4 containing (5-methyl-2-oxo-1,3-dioxol-4-yl)methyl promoieties were prepared, as shown in (Schemes 1 and 2). Free carboxylate of the compound 529 was coupled with 2-trimethylsilylethanol using N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodii-mide (DCC) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP). Benzyl ester moiety of intermediate 6 was cleaved by catalytic hydrogenation to yield carboxylate 7. Reaction of 7 with 1-ethyl-3-(3dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and 4-(hydroxymethyl)-5-methyl-1,3-dioxol-2-one gave compound 8. Phosphonate diester of 8 was hydrolyzed by bromotrimethylsilane (TMSBr),48 and the free phosphonic acid 8a was converted to 9 by the Mitsunobu reaction49 with 4-(hydroxymethyl)-5-methyl-1,3-dioxol-2-one. Removal of TMSE-protecting group of 9 by trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was accompanied by the simultaneous loss of one of the two phosphonic ester functionalities yielding prodrug 2.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and Conditions: (i) DCC, DMAP, TMSE-OH, CH2Cl2, room temperature (rt); (ii) H2, Pd/C, tetrahydrofuran (THF), rt; (iii) ODOL-OH, EDC·HCl, HOBt, dimethylformamide (DMF), rt; (iv) TMSBr, MeCN, 0 °C, Then H2O; (v) ODOL-OH, PPh3, DIAD, THF, rt; and (vi) TFA, CH2Cl2, 0 °Ca

aTotal efficiency of the synthetic pathway for 2, 5.6% over six steps.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and Conditions: (vii) H2, Pd/C, THF, rt; (viii) ODOL-OH, EDC·HCl, HOBt, DMF, rt; (ix) TMSBr, MeCN, 0 °C, Then H2O; (x) ODOL-OH, PPh3, DIAD, THF, rt; (xi) LiN3, DMF, rta

aTotal effciency of the synthetic pathway for 4, 40% over four steps and for 3, 26% over five steps.

Compound 1050 was used as the starting material for the synthesis of prodrugs 3 and 4. We used similar procedures as for the conversion of 6 → 7 → 8 → 9: The benzyl esters in 10 were removed by catalytic hydrogenation. EDC-mediated esterification of the corresponding bis-carboxylate with 4-(hydroxymethyl)-5-methyl-1,3-dioxol-2-one gave compound 11. Both ethyl groups in phosphonate 11 were removed by TMSBr. Esterification of the phosphonic acid 11a with 4-(hydroxymethyl)-5-methyl-1,3-dioxol-2-one using Mitsunobu conditions resulted in prodrug 4. Partial hydrolysis of the phosphonate diester by lithium azide provided prodrug 3. Details of synthesis and characterization of the prodrugs and their intermediates are given in Supporting Information.

Chemical Stability Assessment.

Chemical stability of the prodrugs was assessed at physiological pH in a 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (final concentration: 20 μM). The mixture was vortex-mixed for 30 s and then incubated at room temperature. At specified time points (0 and 60 min), 50 μL of the mixture was removed and quenched with 200 μL of ice-cold acetonitrile containing internal standard (losartan, 0.5 μM). One hundred microliters of the supernatant was diluted with 100 μL of water, and the resulting solution was analyzed by LC–MS/MS. Briefly, prodrugs were analyzed on a Thermo Scientific Accela UPLC system coupled to an Accela open autosampler at ambient temperature with an Agilent Eclipse Plus column (100 × 2.1 mm i.d.) packed with a 1.8 μm C18 stationary phase. The autosampler was temperature-controlled and operated at 10 °C. The mobile phase used for the chromatographic separation was composed of acetonitrile/water containing 0.1% formic acid, and pumps were operated at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min for 4.5 min using gradient elution. The column effluent was monitored using a TSQ Vantage triple-quadrupole mass-spectrometric detector, equipped with an electrospray probe set in the positive ionization mode. Disappearance of prodrugs was measured from peak area ratios of the analyte to IS. Intact prodrug mass transitions can be found in Supporting Information.

In Vitro Metabolic Stability Assessment.

In vitro metabolic stability studies were performed using mouse (Corning Gentest), dog (Xenotech LLC), and human liver microsomes (Corning Gentest); mouse, dog, and human intestinal microsomes (Xenotech LLC); as well as naïve mouse, dog, and human plasma (Innovative Research Inc.). Liver and intestinal microsomal stability assays were performed in an incubation mixture consisting of a 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at a compound concentration of 1 μM. Reactions were initiated by the addition of liver and intestinal microsomes to the preheated incubation mixture (final concentration = 0.5 mg/mL microsomes). Plasma stability was determined by spiking (20 μM) prodrugs in 1 mL of plasma and incubating in an orbital shaker at 37 °C. All stability studies were conducted at predetermined time points (0 and 60 min), where 100 μL aliquots of the mixture in triplicate were removed and quenched by the addition of three volumes of ice-cold acetonitrile containing internal standard (losartan: 0.5 μM). The samples were vortex-mixed for 30 s and centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Fifty microliters of the supernatant was diluted with 50 μL water and transferred to a 250 μL polypropylene vial sealed with a Teflon cap. Prodrug disappearance was monitored over time using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) as described above in the chemical stability section.

In Vitro Metabolite Identification.

Metabolite identiffication was performed on samples from the intestinal metabolic stability study. Briefly, the analysis of prodrug intermediates was performed on a Dionex ultrahigh-performance LC system coupled with a Q Exactive Focus orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham MA). Separation was achieved using an Agilent Eclipse Plus column (100 × 2.1 mm i.d; maintained at 35 °C) packed with a 1.8 μm C18 stationary phase. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. Pumps were operated at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min for 7 min using gradient elution. The mass spectrometer controlled by Xcalibur software 4.0.27.13 (Thermo Scientific) was operated with a HESI ion source in positive ionization mode. Metabolites were identified in the full-scan mode (from m/z 50 to 1600) by comparing t = 0 samples with t = 60 min samples, and structures were proposed based on the accurate mass information.

Pharmacokinetic Study in Mice.

All pharmacokinetic studies in mice were conducted according to protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Johns Hopkins University. Male CD-1 mice between 25 and 30 g were obtained from Harlan and maintained on a 12 h light–dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. 2-PMPA was administered intravenously (IV) at a dose of 10 mg/kg in a 50 mM Hepes-buffered saline, pH adjusted to 7.4. Prodrugs 2 (19.9 mg/kg), 3 (24.9 mg/kg), and 4 (29.8 mg/kg) were formulated in 5% N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, 5% polysorbate 80, and 90% saline (v/v/v) and administered as a single peroral (PO) dose, equivalent to 10 mg/kg 2-PMPA. All of the formulations were freshly prepared prior to the dosing. The mice were sacrificed at specified time points (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h) post drug administration. For the collection of plasma and brain tissue, animals were euthanized with CO2, and blood samples were collected in heparinized microtubes by cardiac puncture. Brains were dissected and immediately flash-frozen (−80 °C). Blood samples were spun at 2000g for 15 min, and plasma was removed and stored at −80 °C until LC–MS/MS analysis. Prior to extraction, frozen samples were thawed on ice.

Pharmacokinetic Study in Beagle Dogs.

Dog pharmacokinetic studies were conducted in accordance with the guidelines recommended in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Absorption Systems (San Diego, CA) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 2-PMPA (n = 2) and 4 (n = 3) were administered to male beagle dogs as a single PO dose of 1 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent (2.98 mg/kg for 4). Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein (~1 mL) via direct vein puncture at specified time points (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h), placed into sodium heparin tubes, and maintained on wet ice until processing. Later, blood samples were centrifuged at 2000g for 15 min at 4 °C. Plasma samples were collected in tubes and stored at −80 °C until bioanalysis.

Bioanalysis of 2-PMPA.

Quantification of 2-PMPA in plasma and brain tissues was performed by LC–MS/MS analysis, as previously described.51 Briefly, standard curves were prepared in naïve plasma and brain tissues at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 50 μM. Plasma samples and calibration standards (25 μL) were extracted for 2-PMPA employing one-step protein precipitation technique, by the addition of 150 μL of methanol containing internal standard (2-phosphonomethyl succinic acid). Samples were vortex-mixed for 30 s and centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 min. The supernatant was then transferred and evaporated to dryness at 40 °C under a gentle stream of nitrogen. Brain samples were diluted 1:2 w/v with methanol, stored at −20 °C for 1 h, and then homogenized. Homogenized brain samples were vortex-mixed and centrifuged as above; 25 μL of the supernatant was mixed with 100 μL of internal standard in methanol and then evaporated to dryness.

2-PMPA samples and standards were derivatized using N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide with 1% tert-butyldimethylchlorosilane (MTBSTFA + 1% TBDMSCl), as described previously.51 Briefly, dried samples and standards were reconstituted in 75 μL acetonitrile, vortex-mixed, followed by the addition of 25 μL of MTBSTFA, and were set to react at 60 °C in a water bath for 30 min. Upon completion of the reaction, samples were centrifuged at 10 000g at 4 °C for 2 min. An aliquot of 70 μL of supernatant was transferred to 250 μL polypropylene autosampler vials sealed with Teflon caps and analyzed via LC–MS/MS. Separation of the analytes was achieved using a Waters X-terra, RP18 column (3.5 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm). The mobile phase was composed of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water with gradient elution. Chromatographic analysis was performed on Accela UPLC and TSQ vantage mass spectrometer. The selected reaction monitoring (SRM) transitions of derivatized 2-PMPA at m/z 683.0 → 551.4 and that of the internal standard at m/z 669.0 → 537.2 were monitored.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis of 2-PMPA.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of 2-PMPA were analyzed using noncompartmental analysis method as implemented in the computer software program Phoenix version 7.0 (Certara Inc., Princeton, NJ). The maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to Cmax (Tmax) were the observed values. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve value was calculated to the last quantifiable sample (AUClast) by use of the log-linear trapezoidal rule. The brain to plasma ratios were calculated as a ratio of mean AUCs (AUC0−t,brain/AUC0−t,plasma).

Statistical Analysis.

For the single time-point pharmacokinetic study, 2-PMPA concentrations from the prodrugs were statistically compared with 2-PMPA alone using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post hoc test. The apriori level of significance was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Prodrug Chemical and Metabolic Stabilities.

Prodrugs 2, 3, and 4 were synthesized and characterized by chemical and metabolic stabilities (Table 1). All prodrugs exhibited an increase in lipophilicity (c Log P = from 0.38 to 2.01) compared to that of 2-PMPA (c Log P = −1.14) (SwissADME, Lausanne, Switzerland).52 Calculated pKa (SciFinder, Ohio) was 2.18 and 2.20 for 2 and 3, respectively, suggesting that these two compounds would be predominantly ionized at pH range over 4.53 All of the three prodrugs exhibited moderate chemical stability (>50% remaining) at pH 7.4.

Table 1.

Lipophilicity and Chemical and Metabolic Stabilities of 2-PMPA ODOL Prodrugs

| Compound | Structure | cLogP | pKa | Chemical stability, pH 7.4 % remaining at 1 h | Plasma stability % remaining at 1 h | Liver microsomal stability % remaining at 1 h | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Dog | Human | Mice | Dog | Human | |||||

| 2-PMPA (1) |  |

−1.14 | 2.06 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 |  |

0.38 | 2.18 | 57 ±6 | 29 ±1 | 16 ±1 | 24 ±2 | 61 ±0 | 72 ± 1 | 60 ± 1 |

| 3 |  |

1.01 | 2.20 | 63 ±2 | 1 ±0 | 0 ± 0 | 0±0 | 12 ±0 | 53 ± 1 | 29 ±0 |

| 4 |  |

2.01 | - | 54 ±1 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

When tested for metabolic stability, all prodrugs were unstable in mice, dog, and human plasma with no intact prodrug remaining following 1 h incubation at 37 °C. In liver microsome across species, 4 was found to be the least stable with no intact prodrug remaining after 1 h incubation at 37 °C, whereas 3 was found to be moderately stable in dog liver microsomes, and 2 was found to be modestly stable in liver microsomes across all species tested with >50% remaining at 1 h. Mouse, dog, and human intestinal microsomal stability study for 4 did not show any intact prodrug level at the end of 1 h incubation (Figure S2). Metabolite identification studies in intestinal microsomes across species suggested the conversion of 4 to intermediate compounds tris- and bis-ODOL-2-PMPA at 1 h (Figure S2).

Prodrugs Showed Enhanced 2-PMPA Plasma Delivery in Mice.

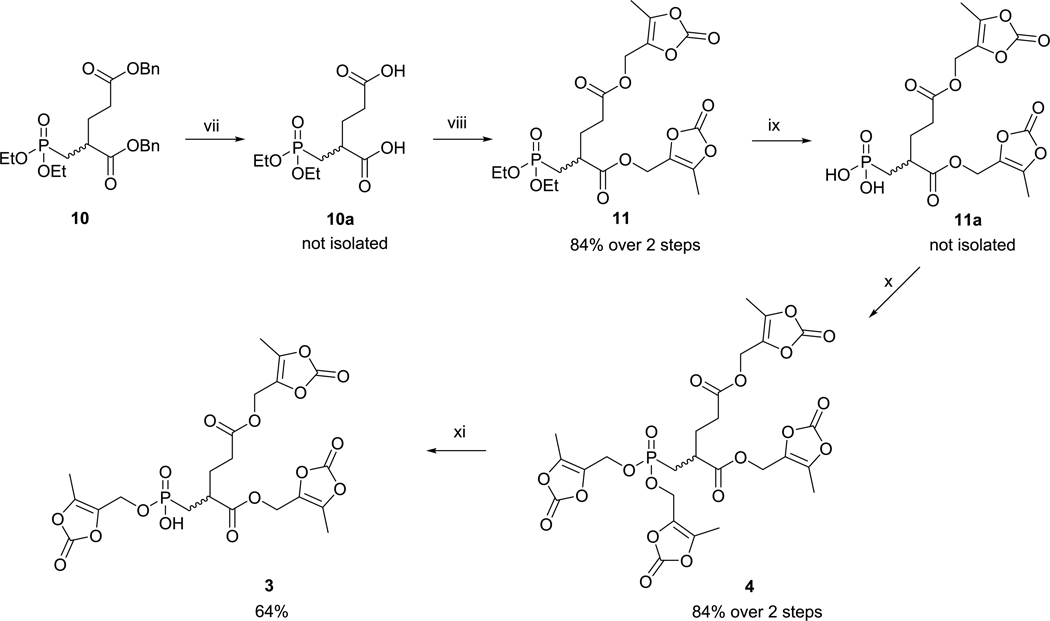

In an initial pharmacokinetic screening study, 2-PMPA and its prodrugs 2–4 were dosed PO to mice, and plasma was collected 30 min post administration. Relative to 2-PMPA, 4 at equivalent dose led to substantially higher concentrations of 2-PMPA in plasma (69-fold; 17.34 ± 5.03 versus 0.25 ± 0.02 nmol/mL) (Figure 1). 2 and 3 also resulted in an approximately 15-fold increase in 2-PMPA plasma concentrations (3.65 ± 0.37 and 3.56 ± 0.46 nmol/mL, respectively). Intact prodrug (2, 3, and 4) levels were undetectable in plasma, suggesting rapid and complete conversion to 2-PMPA in the process of absorption and upon systemic availability.

Figure 1.

2-PMPA plasma concentration at 30 min post oral administration of ODOL prodrugs of 2-PMPA (2–4) to male CD-1 mice as a single dose at 10 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent dose. Data expressed as a mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) (n = 3), with statistics quantified using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test: (**) p < 0.01 and (*) p < 0.05. Based on these results, 4 was prioritized for full pharmacokinetic evaluation in mice.

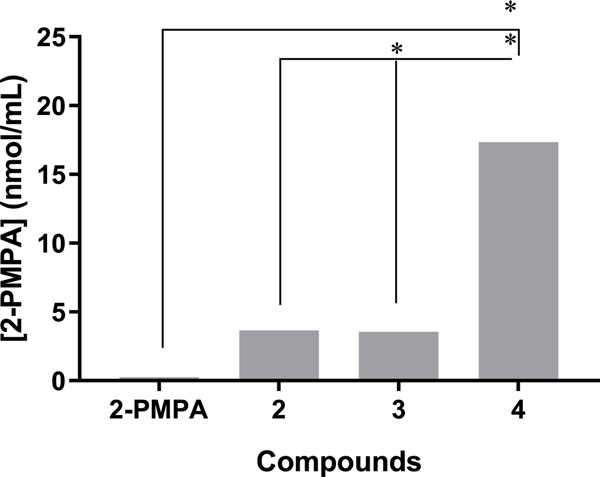

Prodrug 4 Exhibited 80-Fold Higher Exposures Following PO Administration in Mice as Compared to 2-PMPA.

Given the highest 2-PMPA levels from 4 in the single time-point pharmacokinetic screening study, the extended time-dependent pharmacokinetic evaluation was next conducted in mice. Concentration–time profile for 2-PMPA release in plasma and brain is shown in Figure 2A,B, respectively. Following oral administration, 4 (10 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent dose) delivered peak 2-PMPA plasma concentrations (Cmax) of 27.1 ± 11.7 nmol/mL at 15 min post dose (Tmax), with the total exposures (AUC0−t) of 52.1 ± 5.9 h*nmol/mL. The plasma Cmax and AUC0−t following IV administration of 2-PMPA were calculated to be 108.6 ± 9.5 nmol/mL and 104 ± 19 h*nmol/mL, respectively. Based on these results, the calculated oral bioavailability of 4 was 50%. Brain concentrations of 2-PMPA from 4 were also measured in tandem, giving a Cmax of 0.2 ± 0.1 nmol/g and AUC0−t of 1.2 ± 0.2 h*nmol/g. In contrast, 2-PMPA upon IV administration delivered 2-PMPA with a Cmax of 1.2 ± 0.1 nmol/g, but similar exposures to 4 with an AUC0−t of 1.6 ± 0.2 h*nmol/g. AUCbrain/plasma ratio of 2-PMPA following oral administration of 4 and 2-PMPA IV were low and calculated to be 2.3 and 1.5%, respectively (Figure 2C). These ratios were low and are in accordance with the previously described brain to plasma ratios for 2-PMPA.29,51

Figure 2.

Pharmacokinetic studies of 2-PMPA (IV) and 4 (PO) in mice at a dose of 10 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent showing the (A) plasma and (B) brain concentration versus time profile of 2-PMPA. Data expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3, per time point. Oral bioavailability of 2-PMPA from 4 was found to be 50%. (C) Mean ± SEM pharmacokinetic parameters of 2-PMPA in plasma and brain following 10 mg/kg equivalent oral administration of 4 and intravenous administration of 2-PMPA in mice. Brain to plasma ratios are calculated from mean total AUCbrain versus AUCplasma for each route. *Pharmacokinetic data of 2-PMPA in mice following oral administration is adopted from our previously published manuscript for the comparison of oral exposure with 4.

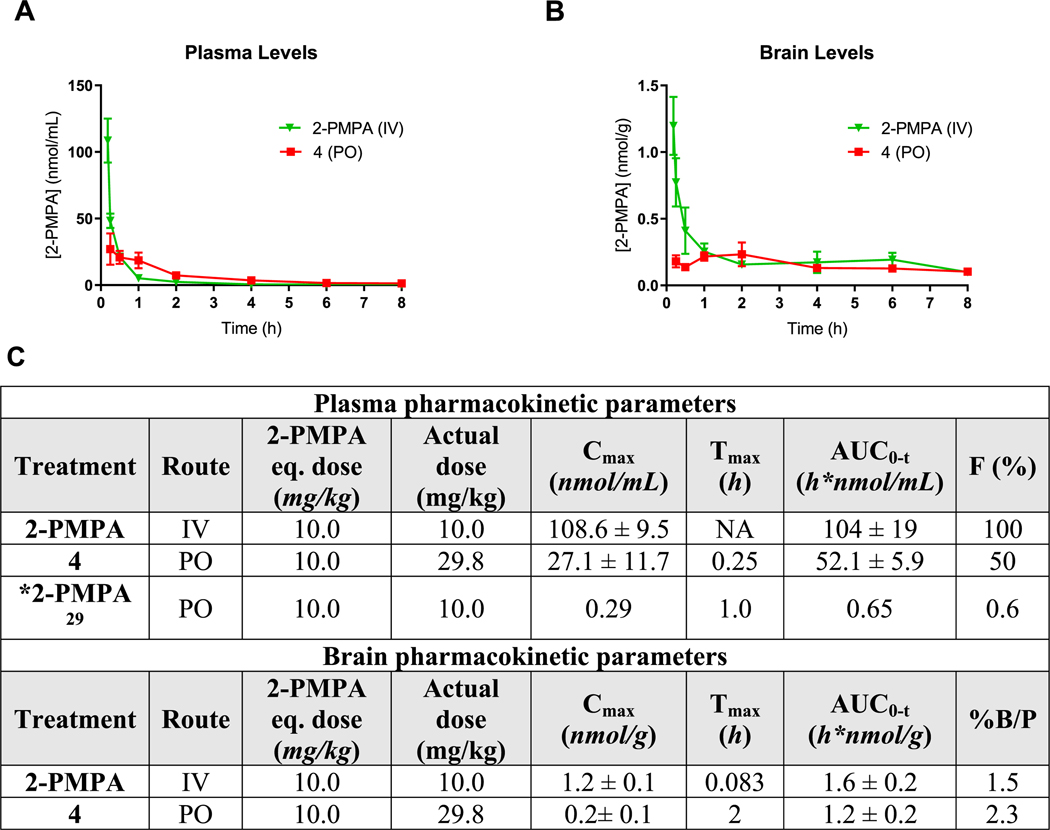

Prodrug 4 Showed 44-Fold High Plasma Exposure in Beagle Dogs Following PO Administration as Compared to 2-PMPA.

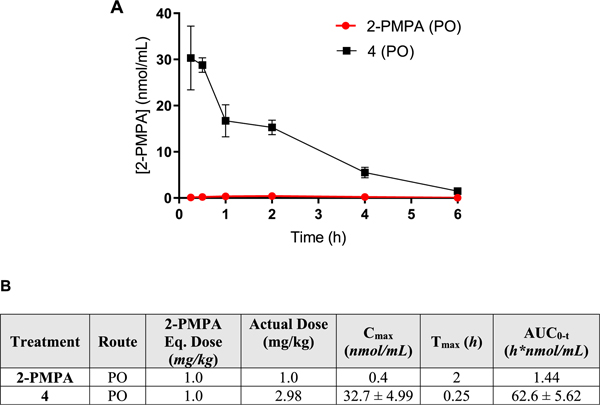

Oral administration of 4 (1 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent dose) in male beagle dogs also resulted in high 2-PMPA plasma exposures (Figure 3A). The absorption was rapid with a Cmax of 32.7 ± 4.99 nmol/mL at 15 min post dose, and AUC0−t was 62.6 ± 5.62 h*nmol/mL. Notably, following oral administration of 2-PMPA, the exposure was low with a Cmax of 0.4 nmol/mL achieved at 2 h post dose and AUC0−t of 1.44 h*nmol/mL (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Pharmacokinetic profile of 2-PMPA (n=2) and 4 (n =3) in male beagle dogs at a dose of 1 mg/kg 2-PMPA equivalent. Data expressed as mean for 2-PMPA and mean ± SEM for 4. (B) Mean ± SEM pharmacokinetic parameters of 2-PMPA in plasma following a 1 mg/kg equivalent oral administration of 2-PMPA and 4 in beagle dogs.

DISCUSSION

Oral delivery of GCPII inhibitors has been highly challenging due to their hydrophilic nature imparted by the pharmacophore needed for GCPII binding.29 Despite considerable chemistry efforts, no GCPII inhibitors (with the exception of thiol-based inhibitors whose development was hindered by thiol-based hypersensitivity reactions)33 have demonstrated effective oral delivery. While known GCPII inhibitors are potent (pM-nM), they typically have three to four acidic functionalities that are charged at physiological pH, leading to poor oral availability that have hampered their development as therapeutics.

One strategy often employed for improvement in oral bioavailability is masking a compound’s polar ionizable groups via a prodrug approach. The idea is that less polar prodrugs will have enhanced intestinal permeability, and upon absorption, they will be cleaved to the active drug via plasma or liver enzymes.54–56 Notably, prodrug strategies are common in drug development; about 10–12% of the approved worldwide drugs are prodrugs, and of these, most are primarily designed with an objective to enhance the permeability of the parent drug.57 Specifically, drugs containing carboxylates, phosphate, phosphonate, or phosphinate functional group encounter permeability challenges due to the anionic charge at nearly all physiological pH, making them highly polar and requiring their delivery as ester- or amide-based prodrugs.58,59 This strategy has been successfully implemented for the approved prodrugs such as adefovir dipivoxil [bis-(pivaloyloxymethyl) ester of adefovir] and tenofovir disoproxil [bis-(isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl) ester of tenofovir], where a 4- and 7-fold enhancement in oral bioavailability was observed, respectively.60–64

Several prodrug approaches have also been reported for the most potent and efficacious GCPII inhibitors.29,33,34,51 Pertinent to the studies described here, we previously synthesized and characterized multiple 2-PMPA prodrugs with distinct chemical structures. Iterative chemistry and pharmacokinetic evaluation led to the identification of 21b (tris-POC-2-PMPA), with isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl (POC) promoieties masking three of the four acidic groups of 2-PMPA. 21b exhibited enhanced 2-PMPA exposures in both mice (oral bioavailability increased from <1 to 11.5%) and dogs,29 although further improvement in pharmacokinetics was desired. Given the success of 21b, we attempted to mask the free γ-carboxylate with the fourth POC promoiety (tetra-POC-2-PMPA) to further enhance permeation and thus achieve higher oral bioavailability. However, this approach was not successful due to poor physicochemical properties including extremely poor solubility and high c Log P (c Log P of tetra-POC-2-PMPA: 3.74 versus c Log P of Tris-POC-2-PMPA: 2.27). Another limitation reported with the POC promoieties is the resulting carnitine depletion, as reported previously.65 Thus, further chemical optimization was pursued to identify 2-PMPA prodrugs with optimal physicochemical properties and enhanced oral exposure for clinical translation.

Herein, we demonstrated that the oral bioavailability of 2-PMPA can be improved by incorporating ODOL promoieties, which have been used in FDA-approved drugs.45–47 ODOL-based prodrugs were considered due to their ability to enhance the oral bioavailability of charged molecules;57 moreover, the liberated byproducts from ODOL, i.e diacetyl and carbon dioxide,66,67 are generally considered safe.67 Finally, prodrugs 2, 3, and 4 with multiple ODOL promoieties imparted optimal physicochemical properties such as optimal c Log P versus 2-PMPA for enhanced oral permeation and desirable metabolic stability to release active 2-PMPA.

Prodrugs 2, 3, and 4 exhibited modest chemical stability in neutral pH 7.4. This is in agreement with the previous reports where ester-based lipophilic prodrugs (spaced with oxomethylene spacers to facilitate hydrolysis) are often labile and prone to degradation at a physiological pH of 7.4.68 In vitro metabolic stability studies in mouse, dog, and human plasma, as well as liver microsomal stability studies, showed that 4 was the least stable, suggesting the likelihood of liberating 2-PMPA following oral administration. Further, metabolite identification studies of the in vitro intestinal stability samples confirmed the formation of 2 and 3 as intermediates of 4 (Figure S2), suggesting that prodrug 4 may undergo presystemic metabolism upon transit through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract across all species tested.

Single time-point oral pharmacokinetic studies in mice showed 69-fold higher 2-PMPA levels from 4 and 15-fold higher 2-PMPA levels from 2 and 3 when compared to 2-PMPA at equivalent doses. This suggests rapid presystemic conversion of 3 to 2 by the loss of one promoiety and its subsequent absorption to liberate similar levels of 2-PMPA. Interestingly, while 4 was the least stable of all of the prodrugs tested, its high lipophilicity presumably led to quick permeation and absorption through the GI tract, enabling the delivery of 69-fold higher 2-PMPA levels versus 2-PMPA, as well as ~4.5-fold higher levels versus prodrugs 2 and 3.

In an extended time-course pharmacokinetic study in mice, 4 delivered high plasma levels of 2-PMPA leading to an enhancement in its oral bioavailability from a negligible <1% to 50%. No metabolites, including 2 and 3, were detected in plasma from the administration of 4 (data not shown), suggesting rapid and complete conversion to 2-PMPA upon systemic absorption. Since 2-PMPA has shown to be efficacious in a variety of neurological disorders, brain levels were also measured in tandem. Interestingly, the brain exposure of 2-PMPA from 4 (1.2 ± 0.2 h*nmol/g) was similar to the IV-administered 2-PMPA (1.6 ± 0.2 h*nmol/g), a route that has shown to be efficacious in neurological diseases.6,9,35

One challenging aspect of prodrug development is the selection of an appropriate animal model, as it can be confounded by interspecies variation in metabolism.68–70 Thus, evaluating the pharmacokinetic behavior of the prodrugs in higher animal species is desirable for recapitulating human prodrug metabolism.71,72 Prodrug 4 showed similar in vitro metabolic stability in plasma, liver, and intestinal microsomes across species including mouse, dog, and human. Next, when tested in vivo, similar to mice, 4 exhibited a 44-fold improvement in 2-PMPA exposures versus oral 2-PMPA in dogs. Based on these results across two different species, it is highly likely that prodrug 4 will provide high systemic exposures of 2-PMPA in humans, if clinically translated.

Overall, the studies described here show the utility of a prodrug approach in enhancing the oral bioavailability of 2-PMPA, a multiply charged GCPII inhibitor with proven efficacy in diseases where GCPII is implicated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by an NIH R01CA161056 and P30MH075673-S1 and National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant (to B.S.S.) and the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic v.v.i. (RVO 61388963).

ABBREVIATIONS

- 2-PMPA

2-(phosphonomethyl)-pentanedioic acid

- AUC

area under the curve

- Cmax

maximum plasma concentration

- CNS

central nervous system

- GCPII

glutamate carboxypeptidase II

- IV

intravenous

- ODOL

(5-methyl-2-oxo-1,3-dioxol-4-yl)-methyl

- PO

peroral

- POC

isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharma-ceut.9b00637.

Additional data on the synthesis and characterization of the prodrugs and the intermediates; mass transitions for LC–MS/MS analysis of prodrugs; chemical structure of internal standards losartan and 2-phosphonomethyl succinic acid; and metabolite identification of prodrug 4 in mouse, dog, and human intestinal microsomes (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Slusher BS; Rojas C; Coyle JT Glutamate Carboxypeptidase II. In Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes; Elsevier, 2013; Vol. 2, pp 1620–1627. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Urazaev AK; Buttram J Jr,; Deen J; Gafurov BS; Slusher B; Grossfeld R; Lieberman E Mechanisms for clearance of released N-acetylaspartylglutamate in crayfish nerve fibers: implications for axon–glia signaling. Neuroscience 2001, 107, 697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lieberman EM; Achreja M; Urazaev AK Synthesis of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) in Axons and Glia of the Crayfish Medial Giant Nerve Fiber. In N-Acetylaspartate; Springer, 2006; pp 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Adedoyin MO; Vicini S; Neale JH Endogenous N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) inhibits synaptic plasticity/transmission in the amygdala in a mouse inflammatory pain model. Mol. Pain 2010, 6, No. 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kozikowski AP; Zhang J; Nan F; Petukhov PA; Grajkowska E; Wroblewski JT; Yamamoto T; Bzdega T; Wroblewska B; Neale JH Synthesis of urea-based inhibitors as active site probes of glutamate carboxypeptidase II: efficacy as analgesic agents. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 1729–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Nagel J; Belozertseva I; Greco S; Kashkin V; Malyshkin A; Jirgensons A; Shekunova E; Eilbacher B; Bespalov A; Danysz W Effects of NAAG peptidase inhibitor 2-PMPA in model chronic pain–relation to brain concentration. Neuropharmacology 2006, 51, 1163–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Yamamoto T; Hirasawa S; Wroblewska B; Grajkowska E; Zhou J; Kozikowski A; Wroblewski J; Neale JH Antinociceptive effects of N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) peptidase inhibitors ZJ-11, ZJ-17 and ZJ-43 in the rat formalin test and in the rat neuropathic pain model. Eur. J. Neurosci 2004, 20, 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yamamoto T; Nozaki-Taguchi N; Sakashita Y; Inagaki T Inhibition of spinal N-acetylated-α-linked acidic dipeptidase produces an antinociceptive effect in the rat formalin test. Neuroscience 2001, 102, 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Slusher BS; Vornov JJ; Thomas AG; Hurn PD; Harukuni I; Bhardwaj A; Traystman RJ; Robinson MB; Britton P; Lu X-CM Selective inhibition of NAALADase, which converts NAAG to glutamate, reduces ischemic brain injury. Nat. Med 1999, 5, No. 1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Carpenter KJ; Sen S; Matthews EA; Flatters SL; Wozniak KM; Slusher BS; Dickenson AH Effects of GCP-II inhibition on responses of dorsal horn neurones after inflammation and neuropathy: an electrophysiological study in the rat. Neuropeptides 2003, 37, 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhang W; Murakawa Y; Wozniak K; Slusher B; Sima A The preventive and therapeutic effects of GCPII (NAALADase) inhibition on painful and sensory diabetic neuropathy. J. Neurol. Sci 2006, 247, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhang W; Slusher B; Murakawa Y; Wozniak K; Tsukamoto T; Jackson P; Sima A GCPII (NAALADase) inhibition prevents long-term diabetic neuropathy in type 1 diabetic BB/Wor rats. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst 2002, 7, 211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Olszewski RT; Bzdega T; Neale JH mGluR3 and not mGluR2 receptors mediate the efficacy of NAAG peptidase inhibitor in validated model of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res 2012, 136, 160–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).McKinzie D; Li TK; McBride W; Slusher B NAALADase inhibition reduces alcohol consumption in the alcohol-preferring (P) line of rats. Addict. Biol 2000, 5, 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Shippenberg TS; Rea W; Slusher BS Modulation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine by NAALADase inhibition. Synapse 2000, 38, 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Xi Z-X; Kiyatkin M; Li X; Peng X-Q; Wiggins A; Spiller K; Li J; Gardner EL N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) inhibits intravenous cocaine self-administration and cocaine-enhanced brain-stimulation reward in rats. Neuropharmacology 2010, 58, 304–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ha D; Bing SJ; Ahn G; Kim J; Cho J; Kim A; Herath KH; Yu HS; Jo SA; Cho IH Blocking glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibits glutamate excitotoxicity and regulates immune responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3438–3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Rahn KA; Watkins CC; Alt J; Rais R; Stathis M; Grishkan I; Crainiceau CM; Pomper MG; Rojas C; Pletnikov MV Inhibition of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) activity as a treatment for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2012, 109, 20101–20106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hollinger KR; Alt J; Riehm AM; Slusher BS; Kaplin AI Dose-dependent inhibition of GCPII to prevent and treat cognitive impairment in the EAE model of multiple sclerosis. Brain Res. 2016, 1635, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Feng J.-f.; Gurkoff GG; Van KC; Song M; Lowe DA; Zhou J; Lyeth BG NAAG peptidase inhibitor reduces cellular damage in a model of TBI with secondary hypoxia. Brain Res. 2012, 1469, 144–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gao Y; Xu S; Cui Z; Zhang M; Lin Y; Cai L; Wang Z; Luo X; Zheng Y; Wang Y Mice lacking glutamate carboxypeptidase II develop normally, but are less susceptible to traumatic brain injury. J. Neurochem 2015, 134, 340–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ben-Shachar S; Yanai H; Baram L; Elad H; Meirovithz E; Ofer A; Brazowski E; Tulchinsky H; Pasmanik-Chor M; Dotan I Gene expression profiles of ileal inflammatory bowel disease correlate with disease phenotype and advance understanding of its immunopathogenesis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2013, 19, 2509–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Noble CL; Abbas AR; Lees CW; Cornelius J; Toy K; Modrusan Z; Clark HF; Arnott ID; Penman ID; Satsangi J; Diehl L Characterization of intestinal gene expression profiles in Crohn’s disease by genome-wide microarray analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2010, 16, 1717–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Zhang T; Song B; Zhu W; Xu X; Gong QQ; Morando C; Dassopoulos T; Newberry RD; Hunt SR; Li E An ileal Crohn’s disease gene signature based on whole human genome expression profiles of disease unaffected ileal mucosal biopsies. PLoS One 2012, 7, No. e37139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Novakova Z; Wozniak K; Jancarik A; Rais R; Wu Y; Pavlicek J; Ferraris D; Havlinova B; Ptacek J; Vavra J Unprecedented binding mode of hydroxamate-based inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II: structural characterization and biological activity. J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 4539–4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Nguyen T; Kirsch BJ; Asaka R; Nabi K; Quinones A; Tan J; Antonio MJ; Camelo F; Li T; Nguyen S; Hoang G; Nguyen K; Udupa S; Sazeides C; Shen YA; Elgogary A; Reyes J; Zhao L; Kleensang A; Chaichana KL; Hartung T; Betenbaugh MJ; Marie SK; Jung JG; Wang TL; Gabrielson E; Le A Uncovering the Role of N-Acetyl-Aspartyl-Glutamate as a Glutamate Reservoir in Cancer. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ferraris DV; Shukla K; Tsukamoto T Structure-activity relationships of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem 2012, 19, 1282–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wang H; Byun Y; Barinka C; Pullambhatla M; Hyo-eun CB; Fox JJ; Lubkowski J; Mease RC; Pomper MG Bioisosterism of urea-based GCPII inhibitors: synthesis and structure–activity relationship studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. dependence are inhibited by the selective glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCP II, NAALADase) inhibitor, 2-PMPA. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 457–467.12629525 [Google Scholar]

- (29).Majer P; Jancari k A; Krecmerova M.; Tichy T; Tenora L; Wozniak K; Wu Y; Pommier E; Ferraris D; Rais R Discovery of orally available prodrugs of the glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) inhibitor 2-phosphonomethylpentanedioic acid (2-PMPA). J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 2810–2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Vornov J; Hollinger K; Jackson P; Wozniak K; Farah M; Majer P; Rais R; Slusher B Still NAAG’ing after all These years: the Continuing Pursuit of GCPII Inhibitors. In Advances in Pharmacology; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 76, pp 215–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Barinka C; Rojas C; Slusher B; Pomper M Glutamate carboxypeptidase II in diagnosis and treatment of neurologic disorders and prostate cancer. Curr. Med. Chem 2012, 19, 856–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zhou J; Neale JH; Pomper MG; Kozikowski AP NAAG peptidase inhibitors and their potential for diagnosis and therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2005, 4, No. 1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ferraris DV; Majer P; Ni C; Slusher CE; Rais R; Wu Y; Wozniak KM; Alt J; Rojas C; Slusher BS; Tsukamoto T delta-Thiolactones as prodrugs of thiol-based glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 243–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Rais R; Vavra J; Tichy T; Dash RP; Gadiano AJ; Tenora L; Monincova L; Barinka C; Alt J; Zimmermann SC; Slusher CE; Wu Y; Wozniak K; Majer P; Tsukamoto T; Slusher BS Discovery of a para-acetoxy-benzyl ester prodrug of a hydroxamate-based glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibitor as oral therapy for neuropathic pain. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 7799–7809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chen SR; Wozniak KM; Slusher BS; Pan HL Effect of 2-(phosphono-methyl)-pentanedioic acid on allodynia and afferent ectopic discharges in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2002, 300, 662–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Luszczki JJ; Mohamed M; Czuczwar SJ 2-phosphonomethyl-pentanedioic acid (glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibitor) increases threshold for electroconvulsions and enhances the antiseizure action of valproate against maximal electroshock-induced seizures in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol 2006, 531, 66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Popik P; Kozela E; Wrobel M; Wozniak KM; Slusher BS Morphine tolerance and reward but not expression of morphine Sebastian, S.; Varma MS; Venkateswarlu G; Bhattacharya A; Reddy PP; Anand RVJSC Efficient synthesis of olmesartan medoxomil, an antihypertensive drug. Synth. Commun 2008, 39, [Google Scholar]

- (38).Tortella FC; Lin Y; Ved H; Slusher BS; Dave JR Neuroprotection produced by the NAALADase inhibitor 2-PMPA in rat cerebellar neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol 2000, 402, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Witkin JM; Gasior M; Schad C; Zapata A; Shippenberg T; Hartman T; Slusher BS NAALADase (GCP II) inhibition prevents cocaine-kindled seizures. Neuropharmacology 2002, 43, 348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wozniak KM; Rojas C; Wu Y; Slusher BS The role of glutamate signaling in pain processes and its regulation by GCP II inhibition. Curr. Med. Chem 2012, 19, 1323–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Rais R; Jiang W; Zhai H; Wozniak KM; Stathis M; Hollinger KR; Thomas AG; Rojas C; Vornov JJ; Marohn M; Li X; Slusher BS FOLH1/GCPII is elevated in IBD patients, and its inhibition ameliorates murine IBD abnormalities. JCI insight 2016, 1, No. 88634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Date AA; Rais R; Babu T; Ortiz J; Kanvinde P; Thomas AG; Zimmermann SC; Gadiano AJ; Halpert G; Slusher BS; Ensign LM Local enema treatment to inhibit FOLH1/GCPII as a novel therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. J. Controlled Release 2017, 263, 132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kratochwil C; Giesel FL; Leotta K; Eder M; Hoppe-Tich T; Youssoufian H; Kopka K; Babich JW; Haberkorn U PMPA for nephroprotection in PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy of prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med 2015, 56, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Nedelcovych M; Dash RP; Tenora L; Zimmermann SC; Gadiano AJ; Garrett C; Alt J; Hollinger KR; Pommier E; Jancǎrǐ′k A. Enhanced Brain Delivery of 2-(Phosphonomethyl) pentanedioic Acid Following Intranasal Administration of Its γ-Substituted Ester Prodrugs. Mol. Pharm 2017, 14, 3248–3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Babu KS; Reddy MS; Tagore AR; Reddy GS;Sebastian S; Varma MS; Venkateswarlu G; Bhattacharya A;Reddy PP; Anand RVJSC Efficient synthesis of olmesartan medoxomil, an antihypertensive drug. Synth. Commun 2008, 39, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Garaga S; Misra NC; Raghava Reddy AV; Prabahar KJ; Takshinamoorthy C; Sanasi PD; Babu KR Commercial synthesis of Azilsartan Kamedoxomil: An angiotensin II receptor blocker. Org. Process Res. Dev 2015, 19, 514–519. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Brousil JA; Burke JMJC Olmesartan medoxomil: an angiotensin II-receptor blocker. Clin. ther 2003, 25, 1041–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).McKenna CE; Higa MT; Cheung NH; McKenna M-C The facile dealkylation of phosphonic acid dialkyl esters by bromotrimethylsilane. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 18, 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Campbell DA The synthesis of phosphonate esters; an extension of the Mitsunobu reaction. J. Org. Chem 1992, 57, 6331–6335. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Harsańyi K.; Domańy G.; Greiner I; Forintos H; Keglevich G Synthesis of 2-phosphinoxidomethyl-and 2-phosphonomethyl glutaric acid derivatives. Heteroatom Chem. 2005, 16, 562–565. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Rais R; Wozniak K; Wu Y; Niwa M; Stathis M; Alt J; Giroux M; Sawa A; Rojas C; Slusher BS Selective CNS uptake of the GCP-II inhibitor 2-PMPA following intranasal administration. PLoS One 2015, 10, No. e0131861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Daina A; Michielin O; Zoete V SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, No. 42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Gabrielson SW SciFinder. J. Med. Libr. Assoc 2018, 106, No. 588. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Aungst BJ; Hussain MA Use of Prodrugs of 3-Hydroxymorphinans to Prevent Bitter Taste upon Buccal, Nasal or Sublingual Administration. U.S Patent US46736791987.

- (55).Hussain AA; AL-Bayatti AA; Dakkuri A; Okochi K; Hussain MA Testosterone 17β-N, N-dimethylglycinate hydro-chloride: A prodrug with a potential for nasal delivery of testosterone. J. Pharm. Sci 2002, 91, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Kao HD; Traboulsi A; Itoh S; Dittert L; Hussain A Enhancement of the systemic and CNS specific delivery of L-dopa by the nasal administration of its water soluble prodrugs. Pharm. Res 2000, 17, 978–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Rautio J; Meanwell NA; Di L; Hageman MJ The expanding role of prodrugs in contemporary drug design and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2018, No. 46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Krise JP; Stella VJ Prodrugs of phosphates, phosphonates, and phosphinates. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 1996, 19, 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Hecker SJ; Erion MD Prodrugs of phosphates and phosphonates. J. Med. Chem 2008, 51, 2328–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Dando TM; Plosker GL Adefovir dipivoxil. Drugs 2003, 63, 2215–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Noble S; Goa KL Adefovir dipivoxil. Drugs 1999, 58, 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Gallant JE; Deresinski S Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Clin. Infect. Dis 2003, 37, 944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Shaw J-P; Sueoka CM; Oliyai R; Lee WA; Arimilli MN; Kim CU; Cundy KC Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of novel oral prodrugs of 9-[(R)-2-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl] adenine (PMPA) in dogs. Pharm. Res 1997, 14, 1824–1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Chapman TM; McGavin JK; Noble S Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Drugs 2003, 63, 1597–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Naesens L; Bischofberger N; Augustijns P; Annaert P; Van den Mooter G; Arimilli MN; Kim CU; De Clercq E Antiretroviral efficacy and pharmacokinetics of oral bis (isopropyloxycarbonyloxymethyl) 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl) adenine in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1568–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Rautio J; Mannhold R; Kubinyl H; Folkers G Prodrugs and Targeted Delivery; Wiley VCH: Hoboken, 2010; p 97. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Assessment report of Edarbi; European Medicines Agency: United Kingdom, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Rautio J; Kumpulainen H; Heimbach T; Oliyai R; Oh D; vinen T; Savolainen J. Prodrugs: design and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, No. 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Fu J; Pacyniak E; Leed MGD; Sadgrove MP; Marson L; Jay M Interspecies differences in the metabolism of a multiester prodrug by carboxylesterases. J. Pharm. Sci 2016, 105, 989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Van Gelder J; Shafiee M; De Clercq E; Penninckx F; Van den Mooter G; Kinget R; Augustijns P Species-dependent and site-specific intestinal metabolism of ester prodrugs. Int. J. Pharm 2000, 205, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Nedelcovych MT; Tenora L; Kim BH; Kelschenbach J; Chao W; Hadas E; Jancarik A; Prchalova E; Zimmermann SC; Dash RP; Gadiano AJ; Garrett C; Furtmuller G; Oh B; Brandacher G; Alt J; Majer P; Volsky DJ; Rais R; Slusher BS N-(pivaloyloxy)alkoxy-carbonyl prodrugs of the glutamine antagonist 6-Diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) as a potential treatment for HIV associated neurocognitive disorders. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60, 7186–7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Zimmermann SC; Tichy T; Vavra J; Dash RP; Slusher CE; Gadiano AJ; Wu Y; Jancarik A; Tenora L; Monincova L; Prchalova E; Riggins GJ; Majer P; Slusher BS; Rais R N-substituted prodrugs of mebendazole provide improved aqueous solubility and oral bioavailability in mice and dogs. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61, 3918–3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.