Abstract

Purpose

We examined whether multi-disciplinary stepped psychosocial care for cancer patients improves quality of care from the patient perspective.

Methods

In a university hospital, wards were randomly allocated to either stepped or standard care. Stepped care comprised screening for distress, consultation between doctor and patient, and the provision of psychosocial services. Quality of care was measured with the Quality of Care from the Patient Perspective questionnaire. The analysis employed mixed-effects multivariate regression, adjusting for age and gender.

Results

Thirteen wards were randomized, and 1012 patients participated (n = 570 in stepped care and n = 442 in standard care). Patients who were highly distressed at baseline had 2.3 times the odds of saying they had had the possibility to converse in private with doctors and/or psychologists/social workers when they were in stepped care compared to standard care, 1.3 times the odds of reporting having experienced shared decision-making, 1.1 times the odds of experiencing their doctors as empathic and personal, and 0.6 times the odds of experiencing the care at the ward to be patient oriented. There was no evidence for an effect of stepped care on perceived quality of care in patients with moderate or low distress.

Conclusions

Stepped care can improve some aspects of perceived quality of care in highly distressed patients.

Trial registration

Keywords: Cancer, Quality of care, Distress, Psychosocial care, Randomized trial

Background

In comprehensive cancer centers, multi-disciplinary care is intended to improve the quality of patient care. This involves the co-operation of surgical and medical departments, communication between health care providers, consideration of quality of life issues, and the provision of emotional support (Schiel et al. 2014; Weis and Giesler 2017). During their acute disease phase, about half of all cancer patients exhibit increased anxiety and depression (Brintzenhofe-Szoc et al. 2009; Mitchell et al. 2011; Singer et al. 2010) and/or they are in need of social or financial support (Büttner et al. 2019; Hisamura et al. 2018; Mosleh et al. 2018; Singer et al. 2011; Wheeler et al. 2018). Sometimes there is a debate within hospitals about who should provide the emotional support to the patients because resources are usually restricted. Patients say they want a team to care for them, whereby the doctors are the crucial persons in that process; more than 80% of the patients wanted to talk to them about their emotional problems (Singer et al. 2009a). Other relevant providers of professional emotional support from the patient perspective are nurses, psychologists, and social workers. Areas of care where improvements are most needed according to patients include participation in treatment decisions, clarity about who is responsible for personal care, access to other patients, and having the possibility of speaking in private with psycho-oncologists (Angerud et al. 2018; Singer et al. 2009a; Tzelepis et al. 2018).

We, therefore, developed a care model where we put the doctors in the center of the multi-disciplinary psychosocial care while at the same time enabling easier access to psycho-oncologists and social workers. This care model used a stepped care approach where (1) all patients with cancer were screened for emotional and social distress, (2) doctors were informed about these results; they then talked to those with increased distress and clarified whether specific support was needed and desired, and (3) if yes, psychosocial services were called for consultation. We evaluated this care model in a cluster-randomized trial (Singer et al. 2014) because the intervention was applied on the ward level.

Our research question was: Do cancer patients who are treated on wards with a structured multi-disciplinary psychosocial care model during their stay at the hospital perceive their quality of care better than patients on wards with care as usual?

Methods

Study design

We performed a cluster-randomized trial (Singer et al. 2014). Wards of a large cancer center were randomized to either the new care model (“stepped care”) or to care as usual (“standard care”). In standard care, psycho-oncologists and social workers could be phoned at the discretion of the doctors or nurses, but distress screening was not performed routinely; consequently, psychosocial care was not a regular topic in doctor–patient consultations in distressed patients. Wards were eligible for randomization if they treated cancer patients and if psycho-oncological care followed the standard model, i.e., a consultation psycho-oncologist was called if a doctor or nurse felt this was needed for a patient. The eligibility criterion for patients was age ≥ 18 years, sufficient command of German and written informed consent. Randomization was performed externally by the Centre for Clinical Trials (IZKS). The wards were concealed for the randomization using random numbers. Only the project manager knew which number belonged to which ward. The IZKS performed the randomization independently and the project manager then unsealed the ward numbers for each arm. Patients were blinded to the arm they were in. They completed questionnaires after their admission to the hospital (t1), before discharge (t2), 3 months after baseline (t3), and 6 months after baseline (t4). Ethical approval was granted by the University Medical Centre Leipzig (#210-12-02072012).

Intervention

The stepped care model used the following steps: (1) each patient was screened for distress (including depression, anxiety, pain, fatigue, and financial difficulties). The results were electronically computed, graphically visualized, and fed back to the clinician in charge. Each patient’s distress level was visualized with colors (green = no or little distress, red = severe distress); (2) consultation with a doctor to provide basic psychosocial care and to decide whether more support was needed; (3) consultation with psychosocial services if needed.

All doctors on the intervention wards were trained in how to interpret the results of the distress screening obtained in step 1. They learned about the relevance of patient support needs and how to address them in their consultations. They also received information about the psychosocial services at the hospital (phone numbers, patient pathways, etc.). After this initial training, they were regularly visited on the ward and could pose any question they might have related to psychosocial care. We also implemented a telephone hotline for their questions, and they could send emails whenever needed. The task of the doctors was to provide basic psychosocial support, i.e., to listen to the patients’ concerns, enabling them to release tension and to feel safe. Their task was also to triage for further support if needed, that is, to identify whether a social worker, psycho-oncologist, psychiatrist, or pain specialist was to be called.

The social workers were responsible if the patient had financial problems or needed help with bureaucratic issues such as applying for rehabilitation or social service support. Psycho-oncologists were called when the patient needed more time to talk about their emotional or social problems, when the problems were more complicated, or when the patient wanted to talk to a specialist with a psychotherapeutic qualification. The psycho-oncologists were all trained in either cognitive behavioral or psychodynamic psychotherapy as well as in psychosocial oncology. The task of the psychiatrists was to consult regarding medication for anxiety or depression, if needed. Pain specialists were called if consultation regarding pain medication was necessary. All of the specialists in step 3 of course also offered basic support in terms of talking and listening.

Psychosocial care both in stepped and in standard care was considered to be a task of the entire team on the ward (doctors of all specialties, nurses, social workers, psycho-oncologists, administrators, nutrition experts, etc.)

Instruments

Perceived quality of care was measured with the questionnaire “Quality of Care from the Patient’s Perspective (QPP)” (Larsson and Larsson 2002; Larsson et al. 1998; Wilde et al. 1994). The items cover Medical-Technical Competence (e.g., “I received examination and treatments within acceptable waiting times.”), Physical-Technical Conditions (e.g., “I had a comfortable bed”), Identity-Oriented Approach (e.g., “I had good opportunity to participate in the decisions that applied to my care.”), and Socio-Cultural Atmosphere (e.g., “There was a pleasant atmosphere on the ward”). One item that was added for a previous study (Singer et al. 2009a) was used here again; it addresses the issue of providing patients with opportunities to speak in private with a psycho-oncologist. Each item is evaluated in two ways by the patients: first, they assess the perceived reality and afterward the subjective importance of that specific issue on a Likert scale. The internal consistency of the perceived reality scales ranges from 0.65 (Physical-Technical Conditions) to 0.91 (Identity-Oriented Approach) (Larsson et al. 2005). The participants in our study completed the QPP at t2 and t4. We used the t2 data (discharge from hospital) as the primary endpoint. Moreover, we primarily focused on the perceived reality scales as our main aim was to improve patient-perceived quality of care and not patient satisfaction with care.

Emotional distress was ascertained with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith 1983). This instrument consists of 14 items. The patients were grouped into those with high versus low or moderate distress based on their baseline data (t1). We used a threshold of ≥ 13 of the total score to differentiate high versus moderate/low levels of distress (Singer et al. 2009b).

Socio-demographic characteristics were ascertained by standardized questions. The highest obtained education was documented and subsequently grouped into compulsory education or below, post-compulsory education, and high-school diploma.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics

Next to the description of the sample (on a cluster level and individual participant level), we calculated the mean for each QPP item at the time of discharge (t2) and half a year later (t4). We compared it with the data of another sample of cancer patients from the same hospital from 10 years earlier (Singer et al. 2009a). Further, we ranked the perceived reality and marked the two items with the highest and the two with the lowest perceived reality.

Testing the effects of stepped care on perceived quality of care

Because the QPP consists of 23 items, we decided a priori to select the items that we hypothesized the stepped care model would have the strongest effect on. The pre-selected items were possibility to converse in private with psychologists/social workers, possibility to converse in private with doctors, empathic and personal doctors, commitment of doctors, and patient orientation. The first two items were combined into one because the stepped care model used a team-based approach and we considered it equally helpful for patients to talk to a doctor or a psycho-oncologist. This combined variable was our primary endpoint in the regression analyses.

We compared perceived quality of care between the trial arms employing mixed-effects multivariate logistic regression. First, we dichotomized the QPP responses into “perceived low quality” (values 1 or 2) versus “perceived high quality” (values 3 or 4). Second, we tested potential effect modification by distress level and education using Mantel–Haenszel tests. If effect modification was found, the subsequent analysis was stratified by this variable. Third, we modeled logistic regressions using mixed models, adjusting for age and gender. The wards were entered as random effect, and we set the covariance structure to identity.

All analyses were performed using STATA 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

Sample characteristics

We contacted the directors of 14 wards and asked them to participate in the study. One of the wards was subsequently excluded from the trial because a liaison psycho-oncological service was established there and hence the standard care was different to the one described in our study protocol as a control condition. All directors of the remaining 13 wards agreed to participate.

Of the stepped care wards, 5 were surgical, and they treated an average of 123 cancer patients per ward during the study period (range 78–169), 812 patients in total. Of the standard care wards, 4 were surgical, and they treated 130 cancer patients on average (range 33–184), 591 patients in total. A detailed analysis of non-participation and attrition is published in a separate paper (Roick et al. 2018).

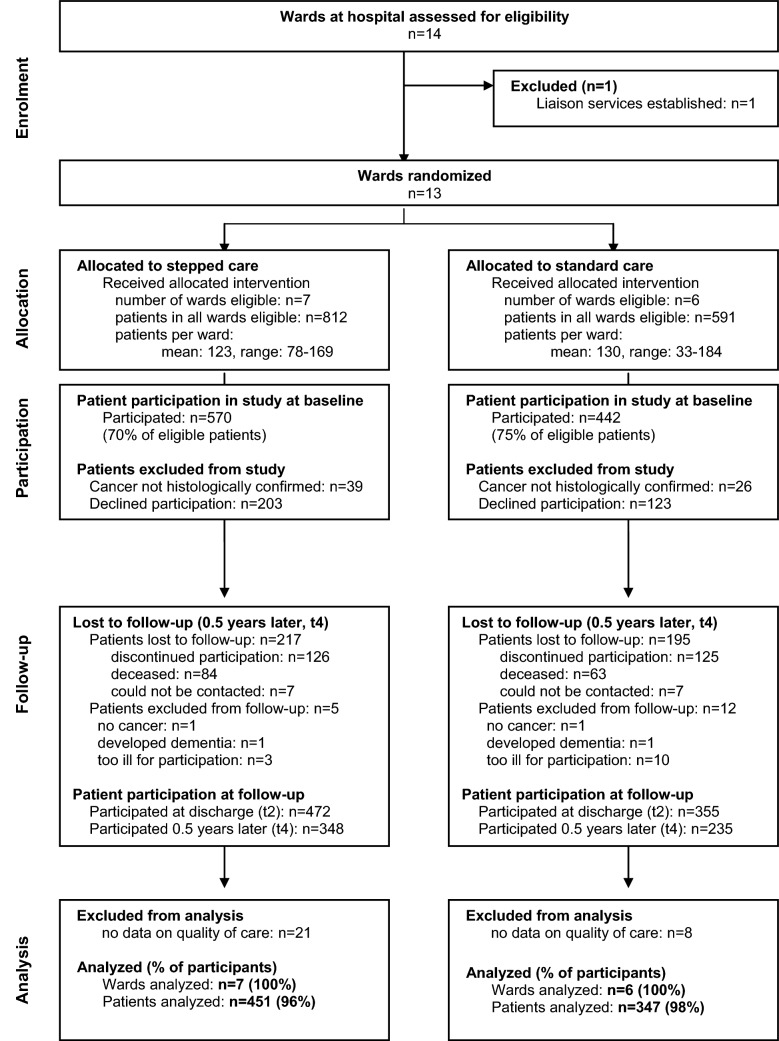

Altogether, 1012 patients were included (14–148 per ward), 570 in stepped care and 442 in standard care (see Fig. 1 for details). They were 63 years old on average (19–91 years) in the stepped care arm and 64 years (24–89 years) in the standard care arm. Respectively, 44% and 30% were female in the stepped care and standard care arms (Table 1). The patients stayed on average 13 days in the hospital [13.2 days in the stepped care arm (range 1–85 days) and 12.6 days in the standard care arm (range 1–71 days)].

Fig. 1.

Patient flow through the trial (CONSORT diagram)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n = 1012)

| Stepped care (n = 570) | Standard care (n = 442) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor site | ||

| Prostate | 43 (7.5%) | 81 (18.3%) |

| Urinary organs | 67 (11.8%) | 47 (10.6%) |

| Breast | 67 (11.8%) | 10 (2.3%) |

| Genital organs | 75 (13.2%) | 27 (6.1%) |

| Gastro-intestinal organs | 103 (18.1%) | 78 (17.7%) |

| Head and neck | 69 (12.1%) | 83 (18.8%) |

| Brain | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (8.6%) |

| Lungs | 51 (9.0%) | 36 (8.1%) |

| Hematologic cancer | 18 (3.2%) | 13 (2.9%) |

| Other | 77 (13.5%) | 29 (6.6%) |

| Stage of disease | ||

| 0/I | 142 (24.9%) | 50 (11.3%) |

| II | 111 (19.5%) | 90 (20.4%) |

| III | 98 (17.2%) | 92 (20.8%) |

| IV | 191 (33.5%) | 191 (43.2%) |

| Unknown | 28 (4.9%) | 19 (4.3%) |

| Type of disease | ||

| Primary | 409 (71.8%) | 329 (74.4%) |

| Recurrent | 58 (10.2%) | 37 (8.4%) |

| Metastatic | 52 (9.1%) | 51 (11.5%) |

| Secondary malignancy | 42 (7.4%) | 17 (3.9%) |

| Unknown | 9 (1.6%) | 8 (1.8%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 71 (12.5%) | 44 (10.0%) |

| Married | 337 (59.1%) | 285 (64.5%) |

| Divorced or separated | 70 (12.3%) | 45 (10.2%) |

| Widowed | 66 (11.6%) | 37 (8.4%) |

| Unknown | 26 (4.6%) | 31 (7.0%) |

| Education | ||

| Compulsory | 107 (18.8%) | 108 (24.4%) |

| Post-compulsory | 339 (59.5%) | 245 (55.4%) |

| College | 119 (20.9%) | 86 (19.5%) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.9%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time employment | 123 (21.6%) | 110 (24.9%) |

| Part-time employment | 30 (5.3%) | 13 (2.9%) |

| Less than part-time, homemaker | 73 (12.8%) | 49 (11.1%) |

| Disability pension | 53 (9.3%) | 28 (6.3%) |

| Age pension | 267 (46.8%) | 232 (52.5%) |

| Other | 16 (2.8%) | 7 (1.6%) |

| Unknown | 8 (1.4%) | 3 (0.7%) |

Values are numbers (percentages)

At baseline, 32% of all the patients were highly distressed, 37% on the stepped care wards and 30% on the standard care wards.

Perceived quality of care

A total of 451 patients responded to the QPP questions at t2 in stepped care wards, and 347 in standard care wards. This corresponds to 96% and 98% of the participants at t2, respectively (see Fig. 1). Six months later (t4), n = 329 and n = 218 provided QPP data.

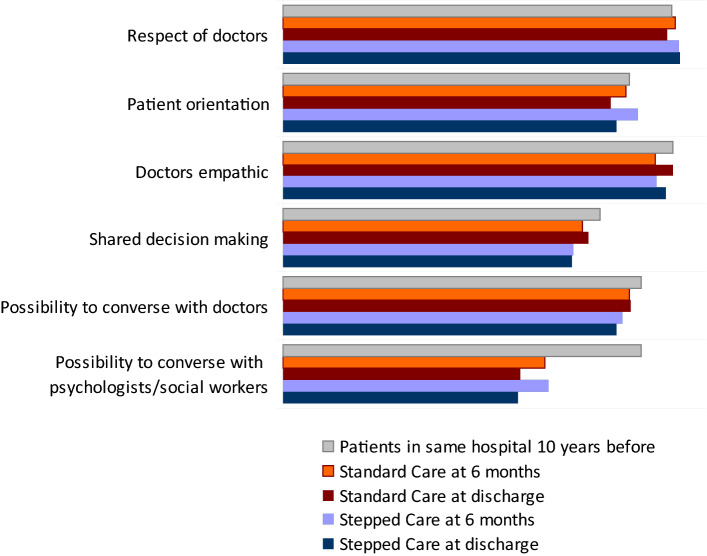

The raw mean scores of perceived quality of care were similar between stepped and standard care per QPP item with slightly higher scores in standard care (Fig. 2). Compared to 10 years before, the perceived quality of care was now lower in respect to the possibility to converse in private with a psychologist and/or social worker.

Fig. 2.

Perceived quality of care in stepped versus standard psychosocial care. For comparison, data from patients with cancer from the same hospital, 10 years before. Higher values indicate better perceived quality of care

The ranking of issues regarding perceived quality of care was also relatively similar between the arms and across time points (see Table 2 for details). Quality of care was perceived lowest in the following areas: nutrition, clarity about who is responsible for personal care, and possibility to converse in private with psychologist/social worker. It was highest for the following issues: care equipment, respect by doctors, and friendly treatment of family and friends.

Table 2.

Quality of care from the patient perspective, perceived reality

| Domains | Items | Before discharge from hospital (t2) | 6 months after admission to hospital (t4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stepped care | Standard care | Stepped care | Standard care | ||

| Medical-technical competence | Physical caring | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Medical care | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.6 | |

| Treatment waiting time | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.4 | |

| Physical-technical conditions | Nutrition | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| Care equipment | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Comfortable bed | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.4 | |

| Identity-oriented approach | Information before procedures | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Information after procedures | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | |

| Clarity about responsibilities (medical care) | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |

| Clarity about responsibilities (personal care) | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.2 | |

| Shared decision-making | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.1 | |

| Commitment (doctors) | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | |

| Commitment (nurses) | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.6 | |

| Empathic and personal (doctors) | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.5 | |

| Empathic and personal (nurses) | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.6 | |

| Respect (doctors) | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| Respect (nurses) | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.7 | |

| Socio-cultural atmosphere | Possibility to converse in private with doctors | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| Possibility to converse in private with nurses | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.2 | |

| Possibility to converse in private with psychologist/social worker | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | |

| Friendly atmosphere | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 | |

| Treatment of family and friends | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| Patient orientation | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.2 | |

Displayed are the raw mean scores per arm and time point at the patient level. Scores range from 1 (low quality) to 4 (high quality). Italics marks the lowest (worst) scores per time point and arm, bold marks the highest (best) scores

Effects of stepped care on perceived quality of care

We found evidence for effect modification on the perceived possibility to converse with doctors and/or psychologists by distress (test for homogeneity of odds ratios p = 0.04) but not by education (test for homogeneity of odds ratios p = 0.50). The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for stepped versus standard care was 2.6 in patients with high distress and 0.9 in patients with low or moderate distress. Consequently, we analyzed stratum-specific ORs for distress but not for education in the following regression models.

Patients who were highly distressed at t1 had 2.3 times the odds of saying they had had the possibility to converse in private with doctors or psycho-oncologists when they were in stepped care compared to patients in standard care, 1.3 times the odds of reporting having experienced shared decision-making, 1.1 times the odds of experiencing their doctors as empathic and personal, and 0.6 times the odds of experiencing the care at the ward to be patient oriented (Table 3). There was no evidence for an effect of stepped care on perceived quality of care in patients with moderate or low levels of distress. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the primary endpoint analysis was 0.083.

Table 3.

Effects of stepped care on perceived quality of care in patients with high and moderate/low levels of distress

| Patients with high distress level | Patients with moderate or low distress level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Possibility to converse with doctors and/or psychologists/social workers | 2.3 | (1.0, 5.3) | 0.05 | 0.7 | (0.3, 1.8) | 0.52 |

| Shared decision-making | 1.3 | (0.6, 3.0) | 0.49 | 0.5 | (0.2, 1.2) | 0.12 |

| Doctors: empathic | 1.1 | (0.3, 3.7) | 0.86 | 0.9 | (0.3, 2.8) | 0.88 |

| Patient orientation | 0.6 | (0.2, 1.5) | 0.27 | 0.8 | (0.3, 2.3) | 0.71 |

Distress was ascertained with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and a cut-off score of ≥ 13 to define high levels of distress

OR odds ratio of perceived quality of care in stepped care wards versus standard care wards, CI confidence interval

Discussion

This study examined whether quality of care from the perspective of patients can be improved by a structured, multi-disciplinary team-based approach to psychosocial care where we combined a routine screening for distress with standard patient pathways for those with increased distress (“stepped care”). We observed that perceived quality of care indeed can be improved but only in patients with high distress and only in respect to the possibility to talk with a doctor and/or psychologist in private. While this is certainly the aspect of care we addressed most clearly with our intervention, we had hoped and hypothesized that also more general aspects of care, such as perceived empathy by doctors or patient orientation, would improve.

How can we explain these results? It is often found that effects of an intervention are larger when the baseline well-being is lower. For example, psychological treatment for depression in cancer patients yields larger effects when it is applied only to cancer patients with depression compared to a general cancer patient population (Faller et al. 2013; Kissane 2009). This can be explained not only by statistical effects such as regression toward the mean, but also by floor effects (those with no depression cannot further decrease their depression). Despite knowing this, we had decided to target not only highly distressed patients but also a general cancer population for three reasons: (1) the intervention is designed to be conducted not only on an individual level but also on a ward level; it cannot be separated by individual patients; (2) one aspect of the intervention is to identify distressed patients. In other words, identifying them is already a part of the intervention; (3) we believe all patients with cancer should have the possibility to talk about their emotional concerns with a team member, not only those with high distress (Singer et al. 2009a).

The second finding that only one aspect of care could be improved is harder to explain. When we search the literature, we find only a few randomized controlled trials with quality of care as an endpoint. Samsson et al. investigated whether a physiotherapist-led orthopedic triage could improve quality of care in a primary healthcare care clinic, compared to standard practice (Samsson et al. 2016). They used two QPP dimensions, namely Medical-technical Competence and Identity-oriented Approach. They did not adjust for confounding and performed statistical tests for both aspects, perceived reality and subjective importance, separately, resulting in 16 hypothesis-testing p values. One could argue that this approach entails the potential danger of cumulating statistical error. However, the median perceived reality scores were consistently higher in their intervention arm compared to standard practice, a result which convincingly shows that they could indeed improve the patients’ quality of care. The authors do not report the data of the other two QPP dimensions, Physical-technical Conditions and Socio-cultural Atmosphere. As the latter contains the item “possibility to converse in private with doctors”, we cannot compare our primary endpoint with their results. However, this is possible for other items. Shared decision-making was 3.6 in their intervention arm and 3.2 in standard practice. In our trial, it was lower in the intervention and similar in the control arm, with 2.9 in the stepped care and 3.1 in standard care. Regarding the commitment of doctors, their scores were 3.9 and 3.0; in our trial, it was 3.7 and 3.8, respectively. Considering these scores together, we can conclude that the patients in our study perceived some aspects of care worse and some better than the patients in the Swedish study; there are obviously no general cultural differences.

We also had the opportunity to compare our current findings with data from patients from the same hospital but 10 years earlier. Surprisingly, we found that the perceived quality of care regarding the possibility to talk to a psychologist/social worker was now considerably lower. The most likely explanation is that the patients’ stay in the hospital is now much shorter, leaving little time for conversations with the medical team. Another interesting point when comparing the earlier results with the current data was that the ranking of quality of care in various areas is strikingly similar. Patients still complain about nutrition (which was not addressed in our current study) and they still judge the care equipment as being among the best areas of care. However, what has changed is that although the possibility to converse with psychologists was of concern 10 years ago, it was not among the two worst areas—but now it is despite our new care model where we tried to improve exactly that! Based on these results, we have to conclude that it will require more than routine distress screening combined with doctor–patient consultations and structured patient pathways to give patients a solid feeling of having the possibility to talk to their healthcare providers in the hospital. What could this “more than” be? It would be especially interesting to find predictors that are aspects of care (“external conditions”) because those can be changed by healthcare providers, in contrast to patient characteristics, which cannot be changed.

A recently published Australian study (Tzelepis et al. 2018) in patients with hematological diseases found that patients with depression reported lower perceived quality of treatment decision-making, coordinated and integrated care, emotional support, and respectful communication than patients without depression. The treatment center that was attended played only a minor role; it was associated only with the quality of information patients received. In contrast, Grøndahl et al. found differences in perceived quality of care between an old (conventional) and a new (high-tech) hospital (Grondahl et al. 2018). This comparison became possible due to a relocation of a hospital between 2015 and 2016. In the new building, there were exclusively single-bed rooms with a private bathroom, compared to multi-bed rooms in the old hospital. Another new feature was the implementation of technology to reduce interaction with staff. Interestingly, despite the reduced interaction with staff, the patient-perceived possibility to talk to doctors was 2.9 in the old and 3.6 in the new hospital. In our study, the mean scores were in between these two: it was 3.3 in stepped care and 3.4 in standard care. Other external care conditions that may affect the perceived quality of care are the competence of health care personnel (Aiken et al. 2002), the nurse–physician relationship (Shen et al. 2011), the atmosphere on the wards (Aiken et al. 2012), and the structure of care (Sjetne et al. 2009).

In addition to the limitations of our trial already mentioned, we would like to name a few more: first, our psychosocial care model did not explicitly include nurses. As a consequence, they delivered the same type and amount of psychosocial care in both arms. The reason for this was simply that we considered it unfeasible to change the behavior of both the doctors and the nurses during the limited time available for this study. However, as we know that nurses are an important source of psychosocial support to patients as well (Aiken et al. 2002; Arving et al. 2006; Singer et al. 2009a), we might have missed an opportunity to further improve perceived quality of care. Second, the trial was performed only in one university hospital. It would have been desirable to include at least one other hospital, which was, in fact, initially planned. However, this other hospital withdrew its consent later because they did not want their psychosocial care to be provided on a randomly allocated basis. Another limitation is that we do not know to what extent the doctors did indeed discuss the screening results with the patients, how much time they spent with the patients discussing their distress, and how much concern they showed, as we could not monitor the consultations in person. Because the time required for documentation is already extremely high for the doctors, we felt we could not ask them to document all this just for our trial. Hence, our analyses are not as fine-grained as we would like. Finally, we would like to mention that the term “stepped care” which we chose for our care model might have different meanings. This term usually implies a sequence of ever more intensive interventions as needed based on initial responses to less intensive interventions, i.e., only those needing more care, based on clear criteria, progress to the next step. In our model, a sequence of steps is combined with a hierarchy of steps: all patients are screened, those with increased distress receive basic psycho-oncological care from their doctor (i.e., a consultation with him or her) and only those patients where this second step is insufficient to improve their well-being are referred to specialized services which provide more support; in other words, their care level is “stepped up”.

Despite these limitations, we can conclude that a multi-disciplinary stepped psychosocial care that includes routine screening for distress, doctor–patient conversation about the screening results and information about psychosocial services, and referral to these services if needed is able to improve the perceived quality of care in highly distressed patients in regard to the possibility to converse in private with doctors and/or psychologists and/or social workers. In line with others (Halkett et al. 2018), we found that doctors are willing and able to provide extended psychosocial support to cancer patients and that this additional effort is effective.

Funding

This study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (#NKP-332-026).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH (2002) Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. J Am Med Assoc 288:1987–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, Sloane DM, Busse R, McKee M, Bruyneel L, Rafferty AM, Griffiths P, Moreno-Casbas MT, Tishelman C, Scott A, Brzostek T, Kinnunen J, Schwendimann R, Heinen M, Zikos D, Sjetne IS, Smith HL, Kutney-Lee A (2012) Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. Br Med J 344:e1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angerud KH, Boman K, Brannstrom M (2018) Areas for quality improvements in heart failure care: quality of care from the family members’ perspective. Scand J Caring Sci 32:346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arving C, Sjoden PO, Lindstrom AT, Wasteson E, Glimelius B, Brandberg Y (2006) Satisfaction, utilisation and perceived benefit of individual psychosocial support for breast cancer patients—a randomised study of nurse versus psychologist interventions. Patient Educ Couns 62:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brintzenhofe-Szoc KM, Levin TT, Li Y, Kissane DW, Zabora JR (2009) Mixed anxiety/depression symptoms in a large cancer cohort: prevalence by cancer type. Psychosomatics 50:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner M, König HH, Löbner M, Briest S, Konnopka A, Dietz A, Riedel-Heller SG, Singer S (2019) Out-of-pocket-payments and the financial burden of 502 cancer patients of working age in Germany: results from a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer 27:2221–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faller H, Schuler M, Richard M, Heckl U, Weis J, Küffner R (2013) Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 31:782–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondahl VA, Kirchhoff JW, Andersen KL, Sorby LA, Andreassen HM, Skaug EA, Roos AK, Tvete LS, Helgesen AK (2018) Health care quality from the patients’ perspective: a comparative study between an old and a new, high-tech hospital. J Multidiscip Healthc 11:591–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkett G, O’Connor M, Jefford M, Aranda S, Merchant S, Spry N, Kane R, Shaw T, Youens D, Moorin R, Schofield P (2018) RT prepare: a radiation therapist-delivered intervention reduces psychological distress in women with breast cancer referred for radiotherapy. Br J Cancer 118:1549–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisamura K, Matsushima E, Tsukayama S, Murakami S, Motoo Y (2018) An exploratory study of social problems experienced by ambulatory cancer patients in Japan: frequency and association with perceived need for help. Psychooncology 27:1704–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissane D (2009) Beyond the psychotherapy and survival debate: the challenge of social disparity, depression and treatment adherence in psychosocial cancer care. Psychooncology 18:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson BW, Larsson G (2002) Development of a short form of the Quality from the Patient’s Perspective (QPP) questionnaire. Clin Nurs 11:681–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson G, Larsson BW, Munck IME (1998) Refinement of the questionnaire ‘quality of care from the patient’s perspective’ using structural equation modelling. Scand J Caring Sci 12:111–118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson BW, Larsson G, Chantereau MW, Von Holstein KS (2005) International comparisons of patients’ views on quality of care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 18:62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N (2011) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol 12:160–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosleh SM, Alja’afreh M, Alnajar MK, Subih M (2018) The prevalence and predictors of emotional distress and social difficulties among surviving cancer patients in Jordan. Eur J Oncol Nurs 33:35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roick J, Danker H, Kersting A, Briest A, Dietrich A, Dietz A, Einenkel J, Papsdorf K, Lordick F, Meixensberger J, Mössner J, Niederwieser D, Prietzel T, Schiefke F, Stolzenburg J-U, Wirtz H, Singer S (2018) Factors associated with non-participation and dropout among cancer patients in a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care 27:12645. 10.1111/ecc.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsson KS, Bernhardsson S, Larsson MEH (2016) Perceived quality of physiotherapist-led orthopaedic triage compared with standard practice in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17:257. 10.1186/s12891-016-1112-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiel RO, Brechtel A, Hartmann M, Taubert A, Walther J, Wiskemann J, Rotzer I, Becker N, Jager D, Herzog W, Friederich HC (2014) Multidisciplinary health care needs of psychologically distressed cancer patients in a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 139:587–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HC, Chiu HT, Lee PH, Hu YC, Chang WY (2011) Hospital environment, nurse-physician relationships and quality of care: questionnaire survey. J Adv Nurs 67:349–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Götze H, Möbius C, Witzigmann H, Kortmann R-D, Lehmann A, Höckel M, Schwarz R, Hauss J (2009a) Quality of care and emotional support from the inpatient cancer patient’s perspective. Langenbecks Arch Surg 394:723–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Kuhnt S, Götze H, Hauss J, Hinz A, Liebmann A, Krauß O, Lehmann A, Schwarz R (2009b) Hospital anxiety and depression scale cut-off scores for cancer patients in acute care. Br J Cancer 100:908–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Das-Munshi J, Brähler E (2010) Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer patients in acute care—a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 21:925–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Hohlfeld S, Müller-Briel D, Dietz A, Brähler E, Schröter K, Lehmann-Laue A (2011) Psychosoziale Versorgung von Krebspatienten Versorgungsdichte und -bedarf. Psychotherapeut 56:386–393 [Google Scholar]

- Singer S, Danker H, Briest A, Dietrich A, Dietz A, Papsdorf K, Lordick F, Meixensberger J, Mössner J, Niederwieser D, Prietzel T, Schiefke F, Stolzenburg J-U, Wirtz H, Kersting A (2014) Effect of a structured psycho-oncological screening and treatment model on mental health in cancer patients (STEPPED CARE): study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials 15:482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjetne IS, Veenstra M, Ellefsen B, Stavem K (2009) Service quality in hospital wards with different nursing organization: nurses’ ratings. J Adv Nurs 65:325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzelepis F, Clinton-McHarg T, Paul CL, Sanson-Fisher RW, Joshua D, Carey ML (2018) Quality of patient-centered care provided to patients attending hematological cancer treatment centers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:E549. 10.3390/ijerph15030549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis J, Giesler JM (2017) Health care research in psycho-oncology. Onkologe 23:893–899 [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, Carey LA, Olshan AF, Reeder-Hayes KE (2018) Financial impact of breast cancer in black versus white women. J Clin Oncol 36:1695–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde B, Larsson G, Larsson M, Starrin B (1994) Quality of care. Development of a patient-centred questionnaire based on a grounded theory model. Scand J Caring Sci 8:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.