Abstract

Canada admits more than 220 000 immigrants every year and this is reflected in the statistic that 18% of the population was born abroad (Beiser, 2005). However, government policy emphasises the admission of healthy immigrants rather than their subsequent health. Immigrants do not show a consistently elevated rate of psychiatric illness, and morbidity is related to an interaction between predisposition and socio-environmental factors, rather than immigration per se. These factors include forced migration and circumstances after arrival, such as poverty, limited recognition of qualifications, discrimination and isolation from the immigrant’s own community. For instance, in Canada more than 30% of immigrant families live below the official poverty line in the first 10 years of settlement (Beiser, 2005).

Some groups are at higher risk of psychiatric morbidity, such as asylum seekers. In this population, symptoms of depression and anxiety, panic attacks or agoraphobia are common and are often reactions to past experiences and current social circumstances (Kisely et al, 2002). More than 20% of asylum seekers in Australia reported previous torture, a third reported imprisonment for political reasons, and a similar proportion the murder of family or friends (Silove et al, 2000; Steel & Silove, 2001; Sultan & O’Sullivan, 2001). In one British study, 65% of Iraqi refugees had a history of systematic torture during detention (Gorst-Unsworth & Goldenburg, 1998). These experiences are compounded by the rigours of reaching safety, social isolation, poverty, hostility and racism (Kisely et al, 2002).

Acculturation

Although resettlement countries can do little to address presettlement experiences, governments can address issues of unemployment, discrimination and acculturation following arrival (Beiser, 2005). Acculturation refers to culture change that results from continuous, direct contact between two independent cultures. This process is known to influence, for example, biological, physical, social, cultural and psychological factors. Aspects include:

enculturation, which is defined as the degree to which an immigrant adopts the new culture or values relationships with the larger society (and which can be associated with ‘culture shock’)

biculturation, which is defined as the degree to which immigrants maintain their cultural identity but also adopt the new culture and larger society (usually in association with access to multiple resources).

Immigrants’ responses to acculturation include the following (Beiser, 2005):

assimilation, where the culture of origin is abandoned in favour of the new

integration, where there is a creative blending of the two

rejection, where the new culture is rejected

marginalisation, where neither the old nor the new are accepted.

Marginalisation is associated with the greatest risk of psychological morbidity, integration the least.

Government policy and immigrant health

Government policies can directly compromise health. Some Canadian provinces insist on a waiting period before newly arrived immigrants can have access to public health services. Concerns about uncontrolled migration have encouraged some destination countries to adopt policies of deterrence, in which increasingly restrictive measures are being imposed on asylum seekers (Kisely et al, 2002). In Australia these include confinement in detention centres, restriction of the right to appeal, and temporary rather than permanent asylum. These policies may be counter-productive, in that they can aggravate pre-existing medical problems and may actually compromise public health.

Some asylum seekers are held in detention facilities for considerable periods of time. An Australian report identified more than 80 detainees who had been held in detention for between 2 and 5 years (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1998). Housing refugees in crowded conditions can facilitate the spread of infectious disease. In America, 90 asylum seekers contracted tuberculosis from a fellow detainee. Detention may also harm the mental health of asylum seekers. Asylum seekers in detention have high rates of attempted suicides and hunger strikes. They also show significantly higher levels of depression, suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress, anxiety and panic attacks than asylum seekers, refugees and immigrants from the same country living in the community (Silove et al, 2000). In Australia, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (1998) has suggested that the boredom and frustration of prolonged detention together with social isolation may be responsible for outbreaks of violence, including domestic violence, among detainees and between detainees and officials. Single women and children may be at increased risk of abuse and exploitation when confined in mixed-gender detention facilities (Silove et al, 2000).

Where do immigrants settle in Canada?

Most immigrants settle in Toronto, Vancouver or Montreal, and they have lower suicide rates than those who go elsewhere in Canada. This is confirmed in studies that show reduced rates of mental illness where there is a like-ethnic critical mass. Immigrants prefer to settle in these urban centres for three reasons:

increased closeness to family or similar ethnic groups

enhanced employment opportunities

improved access to support services that help with integration into Canadian society.

The challenge for smaller provinces

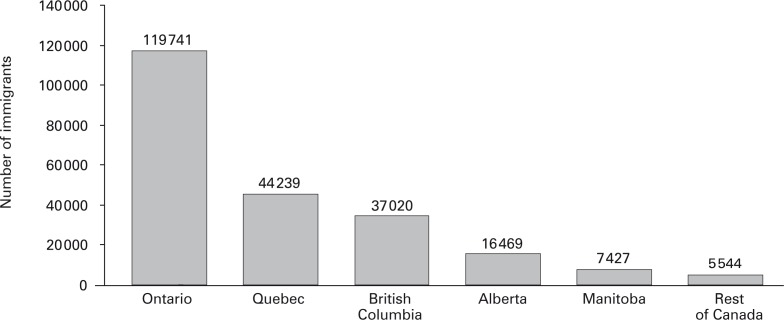

The dilemma for smaller provinces is evident in the statistics presented in Fig. 1. When immigration trends by province are examined, 90% of newcomers go to three provinces: Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. Smaller provinces must find a way to attract and retain immigrants in ways that maximise their physical and mental health. Policies that direct newly arrived entrants to low-density areas where there are few immigrants run counter to research evidence of the health benefits of like-ethnic communities (Beiser, 2005). Such policies also ignore the association between dispersion and compromised mental health (Beiser, 2005).

Fig. 1. Immigration by Canadian province or territory, 2004.

Manitoba’s approach has been of particular interest. In spite of its relatively small population (1 million), Manitoba has consistently ranked fifth among provinces in attracting immigrants and is seeing increasing success in retention (Fig. 1).

Manitoba’s government set an annual target of 10 000 arrivals, with strategies both to attract newcomers to the province and to keep them there (Manitoba Labour and Immigration, 2005). One component is the Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program (MPNP), which is an economic programme that nominates skilled workers for permanent resident status in Canada. It also assists with adult language training and the recognition of qualifications. Manitoba’s immigration programme is run by the Immigration and Multiculturalism Division, which comprises:

adult language training services

settlement and labour market services

immigration promotion and recruitment

a multiculturalism secretariat

a strategic planning and programme support

an executive administration.

Another component of the strategy is the creation of the Manitoba Immigration Council, an appointed 12-member body with representation from business, labour, multicultural organisations and educational institutions. The Council provides advice in three key areas: attracting immigrants; provision and development of settlement services; and complementing the development of crucial supports to retain immigrants in Manitoba.

Having arrived in Manitoba, provincial policy seeks to maximise retention by providing:

employment opportunities, through awareness of labour market needs and willingness on the part of employers to hire immigrants

affordable and available housing (including temporary accommodation)

settlement and integration support (information, orientation, referral, counselling, accessible programmes)

language training (full time, part time, community, workplace, specific purposes, accessible programmes)

access to health, education and social programmes (interpretation, cross-cultural awareness)

community support and appreciation of diversity

cultural and recreational opportunities.

Does it work?

One way of assessing efficacy is to compare Manitoba, which has a population of approximately 1 million, to a similar jurisdiction of roughly the same population, such as Nova Scotia. While Manitoba has its well-established MPNP and Immigration Council, to make it easier for highly skilled immigrants to find employment in occupations for which they have training and experience, such innovation has been absent until recently in Nova Scotia. In 1995, 3500 immigrants settled in each province. Ten years later this had increased to 7427 in Manitoba and fallen to 1770 in Nova Scotia. This difference was statistically significant. Retention rates also differed.

The Manitoban programme has informed the development of a similar strategy in Nova Scotia (Immigration Office, 2005). The province has now established an Immigration Office, consolidating all provincial immigration activities into one location, and set 5-year targets for both doubling the number of immigrants and increasing the retention rate from 40% to 70%.

Conclusions

Government policy can have direct effects on the attraction and retention of immigrants, as well as on their subsequent mental health. Ill-considered initiatives such as denying access to healthcare and not recognising qualifications, or encouraging dispersion, can worsen outcomes. Restrictive policies towards certain groups, such as asylum seekers, can be particularly harmful. On the other hand, policies that recognise the importance both of maximising employment opportunities and of the support of like-ethnic communities can benefit both immigrants and the host country.

Physicians can contribute constructively to the debate in several ways at an individual and collective level. We need to ensure sufficient medical support for detention centres, as well as continuity of treatment programmes on discharge to the community. There is a fine balance between ensuring that asylum seekers receive appropriate healthcare and collusion with a system of detention that is potentially harmful to health. As a profession, we should also be lobbying for migrants’ access to healthcare and other government services, to break the cycle of poverty, ill-health and limited access to health services. Lastly, doctors should set an example within their own profession by streamlining the recognition of qualifications for international medical graduates.

References

- Beiser, M. (2005) The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96, S30–S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorst-Unsworth, C. & Goldenburg, E. (1998) Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq: trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. British Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (1998) Those Who’ve Come Across the Seas: The Report of the Commission’s Inquiry Into the Detention of Unauthorised Arrivals. Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Immigration Office (2005) Nova Scotia’s Immigration Strategy Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia. Available at http://www.gov.ns.ca/immigration (accessed 9 May 2008).

- Kisely, S., Stevens, M., Hart, B., et al. (2002) Health issues of asylum seekers and refugees. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 26, 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Labour and Immigration (2005) Growing Through Immigration: An Overview of Immigration and Settlement in Manitoba. Immigration and Multiculturalism Division of Manitoba Labour & Immigration; Available at http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigrate/infocentre/pdf/mb_settle_present_june05.pdf (accessed 9 May 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Silove, D., Steel, Z. & Watters, C. (2000) Policies of deterrence and the mental health of asylum-seekers. JAMA, 284, 604–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Z. & Silove, D. (2001) The mental health implications of detaining asylum-seekers. Medical Journal of Australia, 175, 596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, A. & O’Sullivan, K. (2001) Psychological disturbance in asylumseekers held in long term detention: a participant-observer account. Medical Journal of Australia, 175, 593–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]