Abstract

Pirfenidone and nintedanib are oral antifibrotic agents approved for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Real-world data on factors that influence IPF treatment decisions are limited. Physician characteristics associated with antifibrotic therapy initiation following an IPF diagnosis were examined in a sample of US pulmonologists. An online, self-administered survey was fielded to pulmonologists between April 10, 2017, and May 17, 2017. Pulmonologists were included if they spent >20% of their time in direct patient care and had ≥5 patients with IPF receiving antifibrotics. Participants answered questions regarding timing and reasons for considering the initiation of antifibrotic therapy after an IPF diagnosis. A total of 169 pulmonologists participated. The majority (81.7%) considered initiating antifibrotic therapy immediately after IPF diagnosis all or most of the time (immediate group), while 18.3% considered it only some of the time or not at all (delayed group). Pulmonologists in the immediate group were more likely to work in private practice (26.1%), have a greater mean percentage of patients receiving antifibrotic therapy (60.8%), and decide to initiate treatment themselves (31.2%) versus those in the delayed group (16.1%, 30.5%, and 16.1%, respectively). Most pulmonologists consider initiating antifibrotic treatment immediately after establishing an IPF diagnosis all or most of the time versus using a “watch-and-wait” approach. Distinguishing characteristics between pulmonologists in the immediate group versus the delayed group included practice setting, percentage of patients receiving antifibrotic therapy, and the decision-making dynamics between the patient and the pulmonologist.

Keywords: Antifibrotic therapy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, irreversible, and fatal fibrotic lung disease with a highly variable, unpredictable disease course, and a median survival of 3–5 years.1,2 Pirfenidone and nintedanib are oral antifibrotic therapies approved for the treatment of patients with IPF and have received conditional recommendation in international treatment guidelines.3–5 Antifibrotic therapies slow disease progression as measured by changes in the rate of absolute decline in percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC), and pirfenidone is associated with a statistically significant reduction in all-cause mortality.6–9 Currently, no fully reliable mechanisms predict either prognosis or treatment response in individuals for whom antifibrotic therapies are being considered.

Clinical trial data suggest that early treatment with antifibrotic therapy on average may confer several benefits. First, antifibrotic therapies reduce the loss in lung function decline and slow disease progression.6–9 Second, baseline % predicted FVC does not predict disease progression, and patients with less advanced disease (i.e. baseline % predicted FVC ≥50%) derive a benefit from antifibrotic therapy similar to that of patients with more advanced disease.10–13 Finally, an increased risk of IPF exacerbations and mortality is associated with disease progression.14–18 In practice, the use of antifibrotic treatment has been reported to be in the range of 2–60%.19,20

Factors that influence the selection of and treatment with antifibrotic therapy include patient preferences, potential adverse events (AEs), disease progression, and individual burden of comorbidities.21,22 A patient’s lifestyle and clinical conditions may influence the selection between pirfenidone and nintedanib. Gastrointestinal-related AEs are the most frequently reported AEs associated with both antifibrotic therapies.6–9 Significant comorbidities associated with IPF that require appropriate consideration and management include pulmonary hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, gastroesophageal reflux, and ischemic heart disease.23

Physician-specific reasons may also impact the antifibrotic decision-making process. In a recent survey of patients and pulmonologists from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, pulmonologists who waited longer than 4 months between IPF diagnosis and treatment initiation in a majority of their patients (i.e. a “watch-and-wait” approach) saw fewer patients in their practices, were less comfortable discussing IPF prognosis, and had less belief in the effectiveness of antifibrotic therapy compared with physicians who initiated treatment in ≤4 months.24 Real-world data describing physician characteristics that may impact treatment approaches in patients with IPF in the United States are limited. This real-world study used a survey to describe practice patterns and characteristics of US pulmonologists regarding treatment initiation with antifibrotic therapy (pirfenidone and/or nintedanib) in patients with IPF.

Methods

Survey design

An online, self-administered, 30-minute survey (Supplemental File 1) was developed by experts in the fields of medicine, epidemiology, health economics, and psychometrics—which was described previously.25 More than 400 interstitial lung disease (ILD) experts were contacted based on their participation in the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation (PFF) Care Center Network.26 These experts were identified based on the PFF’s experience in collaborating with leading medical centers in the United States to fund IPF research and improve patient care.26 Additionally, over 1200 community pulmonologists were contacted via identification from an external database of physicians. For the purposes of this survey, a “community pulmonologist” was delineated as a pulmonologist who did not report evaluating patients in an ILD center that participated in the PFF Care Center Network.

The survey was fielded in the United States between April 10, 2017, and May 17, 2017, and managed by a third party, MedPanel, Inc. (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). Respondents were blinded to the identity of the company sponsoring the survey, Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, California, USA). The identities of the respondents were kept confidential, and informed consent was obtained from all survey participants. Respondents answered questions regarding timing and reasons for considering initiation of antifibrotic therapy after an IPF diagnosis, attitudes toward adopting a watch-and-wait approach, and the decision-making process between the patient and the physician regarding the initiation of antifibrotic therapy. For questions regarding pirfenidone, the survey reflected clinical experience prior to the commercial availability of the 267-mg or 801-mg pirfenidone tablets, which were launched in the United States in mid-May 2017. Therefore, results reflect the use of the 267-mg pirfenidone capsule only.

Pulmonologist screening criteria

Pulmonologists were eligible to participate in the survey if they were licensed to practice medicine in the United States, were board eligible or board certified in pulmonary disease, completed training (residency/fellowship) >1 year prior to participation, spent >20% of their time in direct patient care, treated patients with IPF with antifibrotic therapy (pirfenidone and/or nintedanib), and had ≥5 patients with IPF receiving antifibrotic therapy.

Statistical analyses

Pulmonologists were categorized into two groups according to responses to the question “Do you typically consider initiating treatment with either pirfenidone or nintedanib immediately after establishing the diagnosis of IPF?” The first group comprised respondents who selected “yes, all of the time” or “most of the time” (immediate group), and the second group comprised those who selected “only some of the time” or “no, usually not” (delayed group). For these two groups, survey responses were described using summary statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical data and means (standard deviation (SD)) for continuous data.

Results

Respondent characteristics

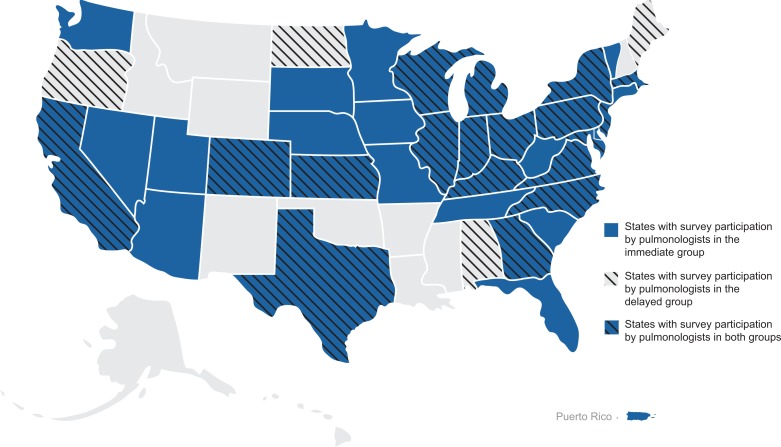

A total of 169 pulmonologists participated in the survey (Table 1). When asked about considering the initiation of antifibrotic therapy immediately after establishing an IPF diagnosis, the majority of pulmonologists (81.7%; n = 138) considered initiating treatment immediately all (n = 59) or most (n = 79) of the time (immediate group). The minority (18.3%; n = 31) considered initiating treatment only some of the time (n = 30) or usually not at all (n = 1) (delayed group). Across the United States, pulmonologists in the immediate group represented practices in 32 states and Puerto Rico, and pulmonologists in the delayed group represented practices in 22 states (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics by willingness to consider treatment immediately after an IPF diagnosis is established.

| Characteristics | Consider initiation of treatment on IPF diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate group (N = 138) | Delayed group (N = 31) | Total (N= 169) | |

| Years practicing pulmonary medicine, N (%) | |||

| 1–5 | 17 (12.3) | 5 (16.1) | 22 (13.0) |

| 6–10 | 30 (21.7) | 5 (16.1) | 35 (20.7) |

| 11–20 | 48 (34.8) | 12 (38.7) | 60 (35.5) |

| 21–30 | 39 (28.3) | 8 (25.8) | 47 (27.8) |

| 31–40 | 4 (2.9) | 1 (3.2) | 5 (3.0) |

| Time managing patients with IPF (years), mean (SD) | 14.9 (8.0) | 15.5 (7.9) | 15.0 (7.9) |

| Professional time spent in direct patient care, N (%) | |||

| 21–40% | 1 (0.7) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (1.8) |

| 41–60% | 12 (8.7) | 2 (6.5) | 14 (8.3) |

| 61–80% | 29 (21.0) | 7 (22.6) | 36 (21.3) |

| 81–100% | 96 (69.6) | 20 (64.5) | 116 (68.6) |

IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of survey respondents by willingness to consider treatment immediately after an IPF diagnosis is established. Shading and hash marks represent states with survey participation by pulmonologists in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

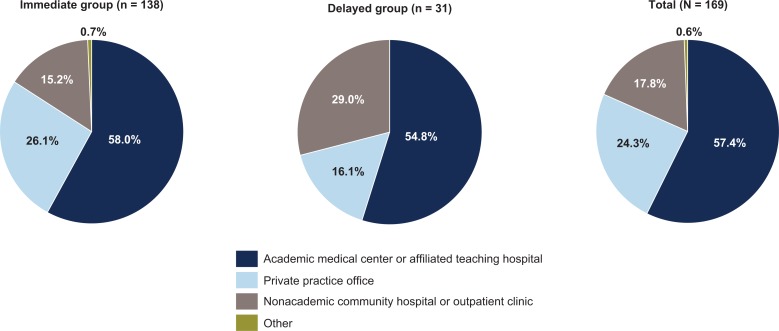

Similar percentages of pulmonologists in both groups had been in practice for 11–20 years (34.8% and 38.7% of the immediate and delayed groups, respectively). Nearly two-thirds of pulmonologists in both groups participating in the survey spent 81–100% of their time in direct patient care (69.6% and 64.5% in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively). Pulmonologists in the immediate group were more likely to work in private practice than were pulmonologists in the delayed group (26.1% vs. 16.1%) (Figure 2). The mean (SD) number of years managing patients with IPF was 14.9 (8.0) years in the immediate group and 15.5 (7.9) years in the delayed group.

Figure 2.

Main practice setting of pulmonologists by willingness to consider treatment immediately after an IPF diagnosis is established. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Characteristics of the IPF clinical practices

The mean (SD) numbers of patients with IPF in a practice reported by the immediate and delayed groups were 65.7 (112.5) and 69.7 (96.2), respectively (Table 2). On average, pulmonologists in the delayed group reported using a watch-and-wait approach for a higher percentage of patients with newly diagnosed IPF compared with pulmonologists in the immediate group (56.8% and 27.3%). The pulmonologists in the delayed group cited absence of symptoms (93.3%), minimal abnormalities determined with pulmonary function tests (93.3%), and patient preference (80.0%) most frequently as considerations for this decision. The mean (SD) percentages of patients receiving any antifibrotic therapy per pulmonologist were 60.8% (26.7%) and 30.5% (24.6%) in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively. Similar percentages of patients who may have required discontinuation due to potential AEs were reported in both groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the IPF clinical practices of pulmonologists by willingness to consider treatment immediately after establishing an IPF diagnosis.

| Characteristics | Consider initiation of treatment on IPF diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate group (N = 138) | Delayed group (N = 31) | Total (N = 169) | |

| Number of patients with IPF | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.7 (112.5) | 69.7 (96.2) | 66.4 (109.4) |

| (Minimum, maximum) | (10, 1000) | (10, 500) | (10, 1000) |

| Patients receiving antifibrotic therapy per pulmonologist (%), mean (SD)a | |||

| Pirfenidone | 57.5 (21.3) | 63.2 (28.2) | 58.6 (22.7) |

| Nintedanib | 42.5 (21.3) | 36.8 (28.2) | 41.4 (22.7) |

| Total (any antifibrotic) | 60.8 (26.7) | 30.5 (24.6) | 55.2 (28.8) |

| Patients with newly diagnosed IPF treated with a “watch-and-wait” approach per pulmonologist (%), mean (SD) | 27.3 (22.3) | 56.8 (26.8) | 32.7 (25.8) |

| Factors cited for consideration when deciding to use a “watch-and-wait” approach per pulmonologist, N (%)b | N = 123 | N = 30 | N = 153 |

| Patient preference | 108 (87.8) | 24 (80.0) | 132 (86.3) |

| Absence of symptoms | 94 (76.4) | 28 (93.3) | 122 (79.7) |

| Minimal abnormalities determined with pulmonary function tests | 83 (67.5) | 28 (93.3) | 111 (72.5) |

| Functional status | 62 (50.4) | 21 (70.0) | 83 (54.2) |

| Comorbidities | 64 (52.0) | 13 (43.3) | 77 (50.3) |

| Advanced-stage disease | 47 (38.2) | 14 (46.7) | 61 (39.9) |

| Other | 5 (4.0) | 1 (3.3) | 6 (3.9) |

| Patients who may require discontinuation of treatment due to potential AEs per pulmonologist, N (%) | |||

| Pirfenidonec | N = 137 | N = 30 | N = 167 |

| 0–20% | 91 (66.4) | 19 (63.3) | 110 (65.9) |

| 21–50% | 39 (28.5) | 10 (33.3) | 49 (29.3) |

| 51–100% | 7 (5.1) | 1 (3.3) | 8 (4.8) |

| Nintedanibc | n = 134 | n = 24 | n = 158 |

| 0–20% | 83 (61.9) | 14 (58.3) | 97 (61.4) |

| 21–50% | 44 (32.8) | 9 (37.5) | 53 (33.5) |

| 51–100% | 7 (5.2) | 1 (4.2) | 8 (5.1) |

AE: adverse event; IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; SD: standard deviation.

aFor pirfenidone and nintedanib, reported percentages are for the total number of patients receiving antifibrotic therapy per pulmonologist, while the total percentage represents the proportion of all patients with IPF in the practice who are receiving any antifibrotic therapy per pulmonologist.

bThe question was not posed to anyone who reported a “watch-and-wait” approach for 0% of patients.

cQuestions were not asked if pulmonologists had no patients receiving pirfenidone or nintedanib.

Selection and initiation of antifibrotic therapy

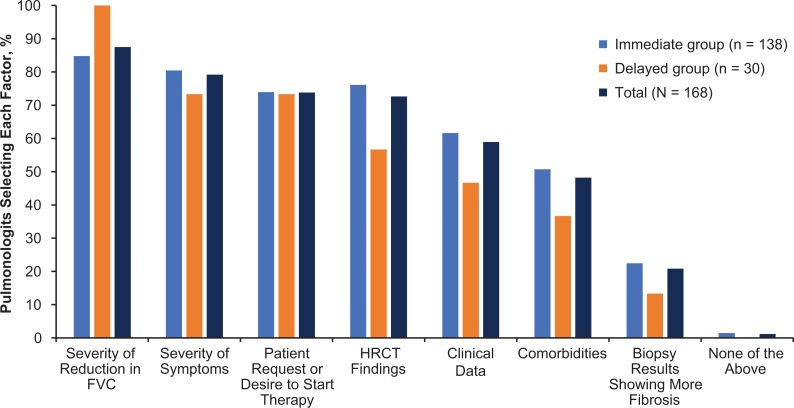

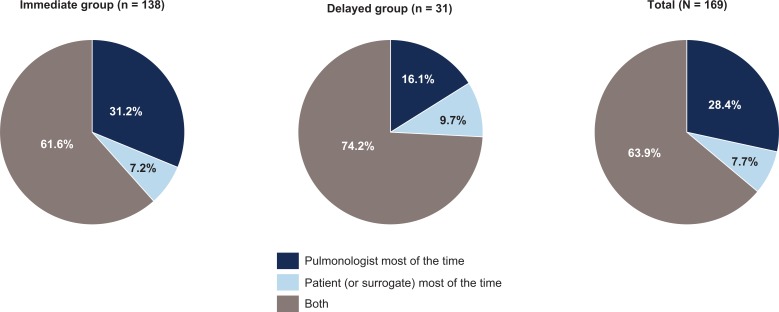

Pulmonologists in both groups noted several reasons for considering antifibrotic therapy immediately after IPF diagnosis, including severity of the reduction in FVC (87.5%), severity of symptoms (79.2%), patient request or desire to start therapy (73.8%), and high-resolution computed tomography findings (72.6%) (Figure 3). Of note, all pulmonologists in the delayed group cited severity of the reduction in FVC as a reason for considering antifibrotic therapy immediately after IPF diagnosis. When determining which antifibrotic therapy should be used, the majority of pulmonologists (63.9%) shared the decision with their patient (Figure 4). However, pulmonologists in the immediate group were more likely to decide to initiate treatment themselves versus sharing the decision with the patient than were pulmonologists in the delayed group (31.2% vs. 16.1%).

Figure 3.

Factors considered in treatment decision-making by pulmonologists (N = 168) by willingness to consider treatment immediately after an IPF diagnosis is established. The question was not posed to anyone who responded “no, usually not” to the question “Do you typically consider initiating treatment with either pirfenidone or nintedanib immediately after establishing the diagnosis of IPF?” IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; FVC: forced vital capacity; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography.

Figure 4.

Decisions regarding initiation of antifibrotic therapy of pulmonologists by willingness to consider treatment immediately after an IPF diagnosis is established. IPF: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Most pulmonologists in both groups commonly recommended a standard titration scheme to initiate treatment with pirfenidone: 99 of 138 (71.7%) versus 20 of 31 (64.5%) in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively. A nonstandard titration scheme was reported in 19.6% and 32.3% of pulmonologists in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively. Of the 37 pulmonologists in both groups who used a nonstandard titration scheme, a 3- or 4-week titration schedule was the most commonly reported nonstandard titration scheme: 17 of 27 (63.0%) versus 7 of 10 (70.0%) in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively. A titration scheme could not be determined in 8.7% (12 of 138) and 3.2% (1 of 31) of cases in the immediate and delayed groups, respectively.

Discussion

This study provides real-world data from a geographically varied sample of pulmonologists in the United States on the distinguishing characteristics between pulmonologists who consider treatment immediately versus those who adopt a watch-and-wait approach after IPF diagnosis. Most pulmonologists consider initiating treatment immediately after an IPF diagnosis all or most of the time. The practice setting, percentage of patients receiving antifibrotic therapy, and decision-making dynamics between the patient and the physician were distinguishing characteristics for those who consider treatment immediately versus those who watch and wait.

Most pulmonologists (81.7%) in this study consider initiating antifibrotic treatment immediately after establishing an IPF diagnosis all or most of the time. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that this survey of US pulmonologists did not specify a defined time frame for “immediate” initiation of antifibrotic therapy. In comparison, real-world data from a survey of physicians from Canada and Europe showed that most physicians initiated antifibrotic therapy >4 months after diagnosis.24 It should be noted that regional access to antifibrotic therapies varies and may impact prescribing patterns. For instance, in some countries, antifibrotic therapies are only available to those with % predicted FVC ≤80%, which may explain some of the regional differences in prescribing practices.

The majority of pulmonologists who consider treatment immediately versus those who adopt a watch-and-wait approach implemented a standard titration scheme when initiating treatment with pirfenidone; however, approximately 30% and 35% in each group, respectively, used nonstandard titration schemes. When queried regarding the most important factors when deciding to implement an alternative titration schedule for pirfenidone, respondents indicated that gastrointestinal intolerance was the most important factor, followed by liver enzyme elevations and patient comorbidities.25

In this study, pulmonologists in the immediate and delayed groups reported using a watch-and-wait approach for 27.3% and 56.8% of patients with newly diagnosed IPF, respectively. These data reflect varying approaches used by pulmonologists, as reports have indicated that 40–98% of patients are not treated with antifibrotic therapy after IPF diagnosis.19,20 While there are clinical trial data to suggest that early treatment with antifibrotic therapy may be warranted due to the unpredictable nature of the disease,1,2 these data must be considered in the context of the individual patient. These decisions and variability in the antifibrotic treatment rate may reflect the pulmonologist’s desire to adhere to the patient’s preferences as well as their own experience and comfort with antifibrotic therapy and monitoring disease progression. Post hoc analyses of the pirfenidone CAPACITY (Studies 004 and 006; NCT00287716 and NCT00287729) trials and the extension study RECAP (Study 012; NCT00662038), which compared the annual rates of FVC decline in patients randomized to pirfenidone or placebo in CAPACITY, showed that those who had delayed pirfenidone treatment (i.e. the placebo group) had lung function loss that was not recovered when pirfenidone was later initiated in RECAP.27 In addition, clinical studies support the reduction in loss of lung function with antifibrotic therapies, regardless of baseline lung function.10,12,28

Pulmonologists in the immediate group were more likely to work in private practice, have more patients currently receiving antifibrotic therapy, and decide to initiate treatment with antifibrotic therapy themselves. These results suggest that pulmonologist-specific factors may influence the decision to initiate treatment earlier, which is consistent with the data presented from other surveys.24 Other factors, such as unspecified characteristics of the pulmonologist’s practice setting, may play a role in the prescribing behavior and could influence the study results.

Both groups of pulmonologists recognized the importance of sharing the decision with the patient, which highlights the importance of appropriate patient education. If pulmonologists have a thorough understanding of the problems that patients with IPF encounter during their disease, communication can be greatly improved.29 Providing patients with relevant information about their disease, treatment, and symptoms can foster a collaborative patient–pulmonologist relationship and ensure that patients remain active and engaged in their care.

Limitations of these real-world survey data include the potential for response bias and the subjective nature of the responses based on individual experiences. The pulmonologists who were contacted and ultimately participated in the survey may be different from those who did not, indicating that the collected data may not fully represent common pulmonology practices. Further, the survey was sponsored by Genentech, Inc., introducing the potential for bias in design. It is possible that patient factors, such as extent of symptom burden and tolerability of antifibrotic therapy, were not given adequate attention in making decisions about the timing of initiation of antifibrotic therapy. Some regions of the United States were not well represented in this survey (e.g. North Central, South Central (except Texas), Alaska, and Hawaii). The survey also focused on patients with newly diagnosed IPF and treatment-naive patients with IPF. Whether these observations are relevant to patients who have a longer-standing diagnosis or who change physicians is uncertain. Despite these limitations, this online preprogrammed survey evaluated real-world IPF practices using a broad range of questions with minimal opportunities for error in administration. The data collected provide insight into the current treatment practices of physicians, in a variety of practice settings, who manage a broad population of patients with IPF receiving antifibrotics.

Conclusions

These real-world data from US pulmonologists provide insight into physician decision-making concerning the initial use of antifibrotic therapy in patients with newly diagnosed IPF. Significant variability remains in the approach to starting treatment in the United States and physicians are challenged by the need to balance clinical trial evidence with patient factors that always impinge on the decision, such as concern about toxicity or lack of symptoms. The importance of providing adequate education resources was revealed in this survey, because these decisions are most commonly shared between patients and physicians. While one approach is not suitable for all patients, treatment decisions should ideally be tailored to the patient rather than to the characteristics of the pulmonologist. Current IPF treatment guidelines have yet to reduce variability and promote a more consistent approach to patient management.

Supplemental material

Supplemental Material, WatchWait_LaCamera_Survey for Physician characteristics associated with treatment initiation patterns in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by Peter P LaCamera, Susan L Limb, Tmirah Haselkorn, Elizabeth A Morgenthien, John L Stauffer and Mark L Wencel in Chronic Respiratory Disease

Footnotes

Authors’ note: Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd/Genentech, Inc. All named authors meet the criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. Third-party writing assistance was provided by Christine Gould, PhD, CMPP, of Health Interactions, Inc. Support for this assistance was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd/Genentech, Inc.

Data availability: The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, because they were generated by a third-party company sponsored by Genentech, Inc., but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: PPL has received personal fees for consulting and advisory boards from Genentech, Inc. TH is a consultant to Genentech, Inc. SLL, JLS, and EAM are employees of Genentech, Inc. MLW has been a speaker for and received compensation from Genentech, Inc.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Genentech, Inc. and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

ORCID iD: Elizabeth A Morgenthien  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1733-6403

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1733-6403

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Ley B, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 788–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Genentech I. Esbriet (pirfenidone) capsules and film-coated tablets, for oral use [package insert]. South San Francisco, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boehringer I. Ofev (nintedanib) capsules, for oral use [package insert]. Ridgefield, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: e3–e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2083–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 377: 1760–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M, et al. Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1079–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2071–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Albera C, Costabel U, Fagan EA, et al. Efficacy of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with more preserved lung function. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Costabel U, Albera C, Kirchgaessler KU, et al. Analysis of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) with more severe lung function impairment treated with pirfenidone in RECAP (Abstract). Chest 2016; 150: 537A. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kolb M, Richeldi L, Behr J, et al. Nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and preserved lung volume. Thorax 2017; 72: 340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wuyts WA, Kolb M, Stowasser S, et al. First data on efficacy and safety of nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and forced vital capacity of ≤50% of predicted value. Lung 2016; 194: 739–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collard HR, King TE, Jr, Bartelson BB, et al. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168: 538–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flaherty KR, Mumford JA, Murray S, et al. Prognostic implications of physiologic and radiographic changes in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 168: 543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paterniti MO, Bi Y, Rekic D, et al. Acute exacerbation and decline in forced vital capacity are associated with increased mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017; 14: 1395–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kondoh Y, Taniguchi H, Katsuta T, et al. Risk factors of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis, Vascu, Diffuse Lung Dis 2010; 27: 103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Song JW, Hong SB, Lim CM, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maher TM, Molina-Molina M, Russell AM, et al. Unmet needs in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-insights from patient chart review in five European countries. BMC Pulm Med 2017; 17: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raimundo K, Kong A, Gray S, et al. Adherence and persistence to antifibrotic treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2017; 152: A441. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hayton C, Morris H, Marshall T, et al. Antifibrotic choice in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: PA2953. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trawinska MA, Rupesinghe RD, Hart SP. Patient considerations and drug selection in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016; 12: 563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raghu G, Amatto VC, Behr J, et al. Comorbidities in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients: a systematic literature review. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 1113–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maher TM, Swigris JJ, Kreuter M, et al. Identifying barriers to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treatment: a survey of patient and physician views. Respiration 2018; 96(6): 514–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wencel ML, Haselkorn T, Limb SL, et al. Real-world practice patterns for prevention and management of potential adverse events with pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Ther 2018; 4: 103–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. Find Medical Care, https://www.pulmonaryfibrosis.org/

- 27. Maher TM, Jouneau S, Morrison L, et al. Deferring treatment with pirfenidone results in loss of lung function that is not recovered by later treatment initiation (poster M28). Thorax 2017; 72: A251–A252. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Noble PW, Albera C, Kirchgaessler KU, et al. Benefit of treatment with pirfenidone (PFD) persists over time in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) with limited lung function impairment (Abstract). Eur Respir J 2016; 48: OA1809. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wuyts WA, Peccatori FA, Russell AM. Patient-centred management in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: similar themes in three communication models. Eur Respir Rev 2014; 23: 231–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, WatchWait_LaCamera_Survey for Physician characteristics associated with treatment initiation patterns in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by Peter P LaCamera, Susan L Limb, Tmirah Haselkorn, Elizabeth A Morgenthien, John L Stauffer and Mark L Wencel in Chronic Respiratory Disease