Abstract

3-fluoroamphetamine (also called PAL-353) is a synthetic amphetamine analog that has been investigated for cocaine-use disorder (CUD), yet no studies have characterized its pharmacokinetics (PK). In the present study, we determined the PK of PAL-353 in male Sprague Dawley rats following intravenous bolus injection (5 mg/kg). Plasma samples were analyzed using a novel bioanalytical method that coupled liquid-liquid extraction and LC-MS/MS. The primary PK parameters determined by WinNonlin were a C0 (ng/mL) of 1412.09 ± 196.12 and a plasma half-life of 2.27 ± 0.67 hours. As transdermal delivery may be an optimal approach to delivering PAL-353 for CUD, we assessed its PK profile following application of 50 mg of transdermal gel (10% w/w drug over 5 cm2). The 10% w/w gel resulted in a short lag time, sustained delivery, and a rapid clearance in plasma immediately after removal. The rodent PK data were verified by examining in vitro permeation through human epidermis mounted on Franz diffusion cells. An in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) analysis was performed using the Phoenix IVIVC toolkit to assess the predictive relationship between rodent and human skin absorption/permeation. The in vitro permeation study revealed a dose-proportional cumulative and steady-state flux with ~70% of drug permeated. The fraction absorbed in vivo and fraction permeated in vitro showed a linear relationship. In conclusion, we have characterized the PK profile of PAL-353, demonstrated that it has favorable PK properties for transdermal administration for CUD, and provided preliminary evidence of the capacity of rodent data to predict human skin flux.

Keywords: 3-fluoroamphetamine, cocaine use disorder, pharmacokinetics, intravenous, transdermal, in vitro-in vivo correlation

Introduction

Psychostimulant abuse is a significant public health problem. There are no FDA-approved pharmacotherapies to treat cocaine-use disorder (CUD)[1–4]. Medication development efforts have examined substitute agonist therapies. Such therapies mimic key aspects of the abused drug in the hopes of reducing craving and withdrawal symptoms to promote abstinence[5]. FDA-approved substitute-agonist therapies include methadone, buprenorphine, varenicline, and transdermal and buccal formulations of nicotine. Previously noted strengths of this approach include the clinical success of these agents, better compliance, reduced withdrawal and craving, and excellent efficacy profiles in preclinical models.

In the central nervous system, cocaine interacts with monoamine neurons, including dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine[6,7]. At their presynaptic terminals, these neurons express specialized plasma membrane proteins that transport these neurotransmitters from the extracellular space back into the cytoplasm, thus inactivating neurotransmitter signaling[8]. Drugs that interact with these transporters can be categorized as either reuptake inhibitors or substrate-type releasers, based on their mechanism of action. Cocaine is a nonselective inhibitor of all three monoamine transporters[9,10].

Previous research has shown that compounds that act as substrate-based releasers with selectivity for dopamine and norepinephrine over serotonin decrease cocaine vs. food choice in nonhuman primates[11–14]. One of the most efficacious compounds to decrease cocaine vs. food choice during 7-day continuous treatment experiments was 3-fluoroamphetamine (also called PAL-353). PAL-353 is a locomotor stimulant that acts as a substrate-based releaser, with selectivity for dopamine over serotonin[15]. PAL-353 was efficacious following acute administration as well as when administered continuously through an indwelling catheter. Other studies have corroborated these findings[16,17]. To build on this research, we have recently reported the potential of PAL-353 for transdermal delivery[18]. We have generated transdermal formulations of PAL-353 and related drugs and demonstrated effective drug permeation through skin[19,20]. Transdermal formulation of substitute agonists for CUD, such as PAL-353, may optimize the therapeutic strategy for this disorder as this pharmaceutics approach 1) provides slow and sustained drug delivery, 2) promotes patient adherence in a difficult to treat population, and 3) may allow for abuse-deterrent formulations. Moreover, drugs with similar chemistries and pharmacologic actions, such as amphetamine, have shown a strong PK and pharmacodynamics (PD) correlation, suggesting that a formulation approach to tightly control the PK profile of PAL-353 may result in an optimized PD outcomes and perhaps optimized therapy[21]. Indeed, this correlation was built between blood concentrations and therapeutic responses[22]. Compliance with currently marketed stimulants is often limited by their sleep disrupting effects and patients with CUD have difficulty with compliance. Likewise, rapid control of the symptoms of CUD, such as craving, is desirable following administration of a therapy. Therefore, a desirable pharmacokinetic profile for PAL-353 should allow for a short latency, a controlled and prolonged delivery, and a rapid clearance following drug removal.

To our knowledge, there is no literature report of a validated bioanalytical assay for determining PAL-353 levels in rat plasma, including any one that uses liquid-liquid extraction and LC-MS/MS. We have therefore developed a novel procedure to quantify the PK profile of PAL-353. Sample enrichment procedures before drug analysis are often needed, as the pretreatment can cause sample dilution and/or contain solvent unamenable to direct analysis. Methods for plasma sample preparation include protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, and solid phase extraction, among which the latter two have been reported to remove more endogenous materials and are preferable for minimizing a matrix effect[23]. LC-MS/MS is preferred for analyzing biological samples because of its excellent selectivity and sensitivity[24]. Therefore, we choose to use liquid-liquid extraction and LC-MS/MS to develop a novel bioanalytical method for plasma levels of PAL-353.

Despite the interest in studying PAL-353 for CUD, no studies have characterized its PK. Following the development of a novel bioanalytical method, we first determined its PK parameters following intravenous bolus injection (5 mg/kg). Given the potential for transdermal delivery of PAL-353, we then assessed its PK profile following application of a 50 mg transdermal gel. The rodent PK data were then verified by examining permeation across human epidermis. An in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) analyses was performed using the Phoenix IVIVC toolkit to assess the predictive relationship between rodent and human skin absorption/permeation. This study provides novel data that elucidate the PK profile of PAL-353 across two routes of administration and they support the continued development of PAL-353 for CUD and perhaps other indications.

Materials and Methods

Materials

PAL-353 free base and PAL-353 hydrochloride and phenmetrazine fumarate were provided by Dr. Blough of the Research Triangle Institute (Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). Tegaderm was a gift sample from 3M (St. Paul, MN). Benecel™ E4M PHARM Hypromellose was a gift sample from Ashland (Wilmington, DE, USA). Sodium lauryl ether sulfate (27%) was ordered from Chemistry Connection (Conway, Arkansas, USA). Propylene glycol was purchased from EK Industries (Joliet, IL, USA). Dermatomed human cadaver skin was procured from New York Firefighter skin bank (New York, NY, USA). Sodium phosphate monobasic and dibasic, phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) 10x concentrate (to be diluted tenfold with deionized water for use), orthophosphoric acid (85%), 0.1N sodium hydroxide solution, hydrochloric acid (37%) and formic acid (99.9%) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Bridgewater, NJ, USA). HPLC grade methanol, methanol (LC-MS grade), water (LC-MS grade), injectable normal saline, EDTA-K2 tubes and HPLC grade methyl tert-butyl ether were obtained from Medsupply Partners (Atlanta, GA, USA).

Methods

Dosing Vehicle Preparation

The solutions for intravenous bolus injections were prepared using PAL-353 hydrochloride at a concentration of 5 mg/mL of base equivalency in normal saline, and sterilized by 0.22-μm filter. PAL-353 transdermal gels for the in vitro permeation study and PK study were formulated with 2% w/w of gelling agent, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC, grade: E4M). The composition of the gels is listed in Table 1. A drug-free gel base was first prepared by dispersing the HPMC powder in a heated (85°C) deionized water and propylene glycol mixture at 1:1 ratio while stirring. The rate of agitation was then decreased, and heating was discontinued. A smooth, clear gel base formed while the mixture cooled. PAL-353 was mixed with the gel base successfully at 5% w/w and 10% w/w without phase separation or turbidity.

Table 1.

The composition of PAL-353 hydroxypropyl methylcellulose gels

| Composition (% w/w) | 5% w/w drug | 10% w/w drug |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose | 2 | 2 |

| Propylene Glycol | 46.5 | 44 |

| Deionized Water | 46.5 | 44 |

| PAL-353 | 5 | 10 |

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study

Male, Sprague Dawley rats weighing 234–302 g (6–8 weeks old) were randomly divided into intravenous and transdermal groups (n=3). All animals were allowed for one week of acclimation before the study. An in vivo PK evaluation was performed following procedures approved by the Mercer University Animal Care and Use Committee. A crossover design was utilized with a washout period of at least seven days between the two experiments. To eliminate the potential for feeding to create variability in drug bioavailability when comparing between different routes of administration that are differentially sensitive to the presence of variable amounts of food in the gastrointestinal system animals were fasted overnight prior to dosing but with free access to water. Intravenous bolus injections at a dose of 5 mg/kg (234–302 μL of PAL-353 hydrochloride in normal saline, equivalent to 5 mg/mL of free base) were given through the lateral tail vein. Animals in the transdermal group were administered a 10% w/w gel (50 mg of gel over 5 cm2) on the shaved dorsal area. The dorsal hair was shaved using an electric groomer (Norelco, Philips, Andover, MA) 24 h before the gel application, with the 24 h period chosen to allow time for stratum corneum recovery. A piece of double-stacked single sided medical tape with a total thickness of 0.254 mm (3M™1521, 3M, St. Paul, MN) was cut out with an area of 5 cm2 and attached to the skin to form a reservoir for gel application. After the gel was thoroughly spread over the 5 cm2 area of skin, a piece of Tegaderm was mounted over the reservoir to prevent the gel from rubbing off. Blood samples (0.15 mL) were collected under isoflurane (1–3% induction, maintenance to effect) from the lateral tail vein and placed in tubes with anti-coagulant EDTA-K2 at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24 h for the group that received PAL-353 by intravenous infusion, and 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 10.5, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24 h for the transdermal group, respectively. Plasma samples were harvested by centrifugation at 3824×g for 5 min at 4 °C, using an Eppendorf 5430R centrifuge (Hamburg, Germany) and stored at −80 °C until analysis. For the transdermal group, the gel was removed nine hours after the application by two dry cotton tips, and the skin was cleaned using cotton tips in the following order: two dipped in 5% lauryl ether sulfate solution, two dipped in deionized water, and then application of two dry tips. A wash-out period of 15 h was observed after the gel was removed.

In Vitro Permeation Study

Human epidermis preparation

Human epidermis was separated using a heat separation technique. Dermatomed human cadaver skin was thawed in PBS at 37 °C immediately after removal from the −80 °C freezer. The thawed skin was subsequently wrapped in aluminum foil and immersed in another beaker containing PBS at 60 °C for 2 min. After heat treatment, the epidermis was scraped off gently using a blunt spatula and extended evenly on a piece of Parafilm®. The separated epidermis was cut into pieces with an appropriate size for Franz cell mounting, and the thickness was verified by a thickness gauge (Cedarhurst, NY, USA).

Skin barrier integrity

The integrity of the human epidermis used in the study was ensured by selecting only skin samples with an electrical resistance of at least 10 kΩ [25]. Skin resistance measurements were conducted using silver-silver chloride electrodes attached to a digital multimeter: 34410A 6 ½ (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) coupled with an arbitrary waveform generator (Agilent 33220A, 20 MHz Function). The epidermis pieces were mounted on to Franz cells with PBS (5.0 mL) loaded as the receptor compartment solution. The donor compartment was placed onto the skin and both aligned and clamped together with the receptor compartment. Then, PBS (300 μL) was added in the donor compartment. Skin pieces were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min. Following equilibration, Ag and AgCl electrodes were placed in the receptor and donor compartment, respectively. A dummy load resistor (RL) was placed in series with the skin, and the voltage drop across the entire circuit and skin (VS) was recorded from the multimeter (VO). The following equation was used to calculate the skin resistance (RS):

Where, VO and RL were 100 mV and 100 kΩ, respectively.

In vitro permeation

Following the skin resistance measurement, the PBS in the donor compartment was removed using a Kimwipe. A dose of 10 mg/cm2 of 5% w/w and 10% w/w gel that contained 0.32 mg/0.64 cm2 and 0.64 mg/0.64 cm2 of PAL-353, respectively, was dispensed and gently spread over the exposure area of 0.64 cm2 using an electronic positive displacement pipette (Repeater® E3x, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Then, the receptor compartment samples (300 μL) were collected at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 22 and 24 h. Sink conditions in the receptor compartment were maintained using PBS (diluted from 10X concentrated solution, containing 11.9 mM of phosphates, 137 mM of sodium chloride and 2.7 mM potassium chloride) wherein the saturation solubility of PAL-353 free base was 16.70 ± 0.08 mg/mL. The water jacket was maintained at 37 °C so that the skin surface was 32 °C. The samples were then analyzed by using the validated HPLC-UV method as described below.

Analytical Methods

In vivo quantitative analysis

Plasma sample pretreatment was carried out by using liquid-liquid extraction. Five microliters of PAL-353 working standards were added to 50 μL of plasma to form calibrators at 0.5 ng/mL-500 ng/mL. Then, 5 μL of phenmetrazine (1 μg/mL) was spiked into each sample as the internal standard. Each sample was gently mixed for 5 s followed by the addition of 10 μL of 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution and gentle mixing. Methyl tert-butyl ether (180 μL) was added and mixed with the sample for 5 min on a vortex mixer. The organic supernatant was transferred to a new tube containing 20 μL of 1% hydrochloric acid methanolic solution after centrifugation at 20817 xg for 10 min at 4 °C. The samples were then dried in a SpeedVac at 30 °C. The dried samples were reconstituted with 100 μL of solution consisting of 95% of LC-MS grade water and 5% of LC-MS grade methanol. In vivo study plasma samples were treated in the same manner without the addition of PAL-353 working standards.

Sample analysis was performed using LC-MS/MS. The HPLC system (Agilent 1200 system, Agilent, USA) comprising of a system controller, quaternary gradient pump, autosampler, column oven, and online degasser, was coupled to an Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source (Agilent, USA). PAL-353 was separated on a Waters XSelect CSH C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 3.5 μm). The column oven temperature was maintained at 25°C. A flow rate at 0.4 mL/min was used. The mobile phase consisted of A: water with 0.1% (v/v) of formic acid, and B: methanol with 0.1% (v/v) of formic acid. Initial chromatography conditions consisted of 5% methanol/formic acid, which changed to 20% methanol/formic acid at 1.0 min and was held steady for 2.0 min. Then, the methanol/formic acid increased to a concentration of 95% between 3.0–4.0 min and was steady held for 2 min. The methanol/formic acid concentration returned to the initial condition of 5% at 7.0 min. Further, 5.0 min were allowed for equilibration. The first minute of flow was diverted to waste and the rest to the mass spectrometer. The autosampler temperature was maintained at 4°C, and the injection volume was 5.0 μL.

PAL-353 was monitored in positive electrospray mode with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions of 154.3 → 109.2 and 154.3 → 137.2, which served as the quantifier and the qualifier, respectively. The internal standard, phenmetrazine, was monitored in positive electrospray mode with MRM transitions of 178.2 → 115.2 (178.2 → 117.2 as qualifier). Mass spectrometer parameters were optimized using Agilent MassHunter Optimizer. The final parameters chosen were: Fragmentor = 95 (PAL-353) / 60 (phenmetrazine); Collision energy=17 (154.3 → 109.2), 5 (154.3 → 137.2), 30 (178.2 → 115.2) and 21 (178.2 → 117.2); Dwell= 200; Cell accelerator voltage = 7 V; Gas temperature = 300°C; Gas flow = 11 L/min; Nebulizer = 15 psi; Capillary voltage = 4000 V.

In vitro quantitative analysis

A validated method was used to quantify the in vitro permeation study samples. Waters Alliance 2695 separation module (Milford, MA, USA) coupled with a Waters 996 photodiode array detector was used. The separation was conducted on a Waters XTerra RP18 column (3.5 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm). The column temperature was set at 35°C. The mobile phase consisted of 25% of methanol and 75% of sodium phosphate buffer (12.5 mM, pH 6.0). Each sample run lasted 10 min with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The injection volume was set at 15 μL. The chromatogram peak area was recorded at 261 nm.

Data Analyses

In vivo absorption

Noncompartmental analysis of plasma concentration versus time profiles from intravenous and transdermal groups was performed by using Phoenix WinNonlin 8 (Certera USA, Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA). Pharmacokinetic parameters such as AUCinf, half-life (T1/2), mean residence time (MRT), and clearance (Cl) were calculated. The absolute bioavailability (Fabs) was calculated by the following equation[26]:

Assuming that the transdermal delivery of PAL-353 is following zero-order kinetics, the dose delivered by the transdermal route can be calculated by using the clearance data obtained from the intravenous group using the following equation[26]:

Fabs × dose delivered accounts for any pre-systemic drug loss, such as those in the skin and subdermal layers, and therefore was calculated as a single parameter from the above equation.

In vitro permeation

The steady-state flux and lag time were estimated from the equation that resulted from the linear regression of the linear portion of the cumulative amount permeated over time function, where the slope is steady-state flux, and the x-intercept is considered the lag time. The percentage delivery (0–100%) and fraction permeated (0–1) were both calculated based on the applied concentration. The analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation was performed using Phoenix IVIVC Toolkit (Certera USA, Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA). To enable the IVIVC analysis, the in vitro permeation study data were converted to fraction permeated, and the in vivo plasma data was numerically deconvoluted to obtain the fraction absorbed.

Statistical Analyses

All data are presented as the Mean ± SD. Two-tailed student’s t-test was performed using GraphPad Prism7 (San Diego, CA), and a p < 0.05 was used to arbitrate a significant difference.

Results

Bioanalysis of PAL-353 in Rat Plasma

To support the conduct of pharmacokinetic studies in rats, a bioanalytical method for the determination of PAL-353 in plasma using liquid-liquid extraction and LC-MS/MS was developed. The limit of quantification of the developed bioanalytical method was 0.5 ng/mL. An example chromatogram of PAL-353 at the transition of 154.3–109.2 m/z for spiked plasma extraction sample at 0.5 ng/mL (signal-to-noise ratio=10.5) is shown in Fig. 1. The intraday and inter-day precision and accuracy values (Table 2) for three levels of quality control samples were all within the acceptance criteria (not more than 15% of the coefficient of variance, and not more than 15% from nominal concentrations). The recovery was consistent at all levels, and no apparent matrix effect was observed (<15%). These parameters were in accordance with the FDA’s guidance of bioanalytical method validation for the industry.

Fig. 1.

A representative chromatogram of PAL-353 at the transition of 154.3–109.2 m/z for spiked plasma extraction sample at 0.5 ng/mL (signal-to-noise ratio=10.5).

Table 2.

Inter-day and intraday precision and accuracy, recovery and matrix effect of the bioanalytical method

| Nominal Concentration (ng/mL) | Intraday precision and accuracy (n=5) |

Inter-day precision and accuracy (n=3) |

Recovery (%, n=3) | Matrix Effect (%, n=3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | % CV | Accuracy (%) | Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | % CV | Accuracy (%) | |||

| 1.5 | 1.44±0.06 | 3.87 | 96.4±3.7 | 1.49±0.04 | 2.42 | 99.1±2.4 | 73.4±7.4 | 108.4±3.1 |

| 40 | 45.5±2.0 | 1.04 | 109.0±1.1 | 41.7±1.6 | 3.82 | 104.1±4.0 | 71.3±2.8 | 102.8±2.0 |

| 400 | 447.8±2.9 | 0.57 | 109.0±0.6 | 423.7±14.3 | 3.37 | 105.9±3.6 | 67.5±1.8 | 98.7±2.4 |

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Study

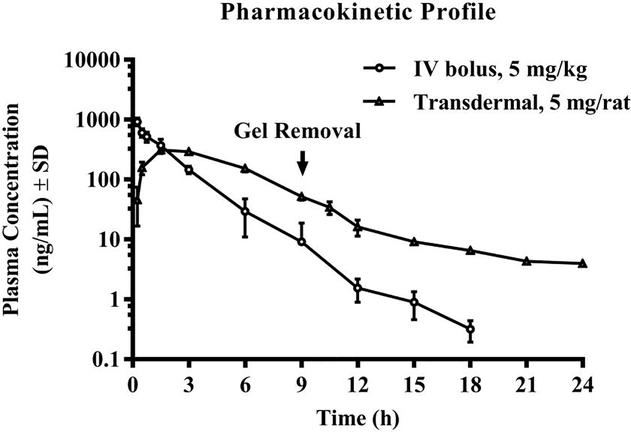

The pharmacokinetics of PAL-353 were investigated in Sprague Dawley rats (n=3) following intravenous and transdermal administrations. The plasma concentration-time profiles of PAL-353 following intravenous and transdermal gel administrations are shown in Fig. 2. Pharmacokinetic parameters obtained from the non-compartmental analysis by WinNonlin are listed in Table 3. In the intravenous group, the plasma concentrations after 18 h were all lower than the limit of quantification (LOQ), 0.5 ng/mL, and therefore not included in the profile.

Fig. 2.

Plasma profile of PAL-353 following intravenous bolus injection and transdermal administration of 10% w/w gel (n=3, mean ± SD).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of PAL-353 after intravenous bolus injection and transdermal administration of 10% w/w gel.

| Parameters | Intravenous (n=3, mean ± SD) | Transdermal (n=3, mean ± SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 924.39 | ± | 136.3 | 312.58 | ± | 31.16 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.25 | 1.5 | ||||

| C0 (ng/mL) | 1412.09 | ± | 196.12 | 0 | ||

| T1/2 (h) | 2.27 | ± | 0.67 | 7.13 | ± | 0.27 |

| AUCt (ng/mL*h) | 1592.61 | ± | 350.95 | 1834.91 | ± | 216.37 |

| AUCinf (ng/mL*h) | 1593.70 | ± | 351.01 | 1875.48 | ± | 215.27 |

| AUMCinf (ng/mL*h2) | 2796.17 | ± | 924.21 | 10011.58 | ± | 978.46 |

| MRTinf (h) | 1.73 | ± | 0.22 | 5.35 | ± | 0.15 |

| Vss (mL) | 1417.75 | ± | 199.33 | - | ||

| CL (mL/h) | 836.38 | ± | 205.52 | - | ||

| Fabs (%) | 100 | 31.8a | ||||

Transdermal dose equals to 18.5 mg/kg based on actual rat body weight (0.271 ± 0.008 kg)

Following the administration of 5 mg/kg of PAL-353 intravenously, the overall plasma PK profile plotted in a semi-logarithmic scale appeared to be linear, and the half-life, clearance and AUC of PAL-353 were found to be 2.27±0.67 h, 836.38±206.52 mL/h and 1593.70 ± 351.01 ng/mL*h, respectively. Following transdermal application of 5 mg of PAL-353 in 10% w/w gel to each rat, a rapid permeation in the early sampling time points and maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of 312.58 ± 31.36 ng/mL at 1.5 h (Tmax) were observed. The AUCinf was found to be 1875.48 ± 215.27 ng/mL*h for the transdermal group. After dose normalization, i.e., the transdermal dose as expressed with mg per rat was converted to mg/kg based on the average actual body weight of the experiment animals (See Table 3, footnote b), the absolute bioavailability was found to be 31.8%. Fabs × dose delivered was found to be 1.57 mg. Given a constant rate delivery, the rate of permeation over the 9 h-wear of gel corresponds to 34.9 μg/cm2/h. The MRTinf was prolonged to be 5.35 ± 0.15 h for the transdermal group, as compared to 1.73 ± 0.22 h for the intravenous group. It was also found in the transdermal PK study that no visible skin reaction was observed in the applied area during the study period.

In Vitro Permeation Study

The in vitro permeation of PAL-353 across human epidermis was evaluated in the in vitro permeation study using vertical Franz diffusion cells. Fig. 3 depicts the in vitro permeation profile of PAL-353 from gels with two strengths. After 24 h of permeation, the 5% and 10% w/w PAL-353 gels delivered a respective cumulative amount of 453.0 ± 36.1 and 761.3 ± 12.4 μg/cm2 across the human epidermis. PAL-353 permeated through the skin efficiently, with high percentage of applied dose delivered and minimal lag times. Approximately 60% and 75% of PAL-353 applied were delivered into the receptor solution after 9-h and 24-h permeation for both strengths of gels (exact values are shown in Fig. 3). Short lag times, 6.9 ± 2.1 min for 5% w/w gel and 4.7 ± 1.8 min for 10% w/w gel, were required to reach the steady-state flux. The steady-state flux of PAL-353 obtained between 0–6 h from the 5% w/w and 10% w/w PAL-353 gels across the human epidermis were found to be 43.6 ± 2.6 μg/cm2/h and 87.0 ± 4.4 μg/cm2/h, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The in vitro permeation profile of PAL-353 from 5 and 10% w/w gels. The percentage of delivery at 9 h and 24 h were labeled under the symbol corresponding to those sample points. (n=4, mean ± SD).

The Analysis of In Vitro-In Vivo Relationship

To investigate a potential Level A correlation between the in vitro permeation and in vivo absorption for the transdermal gel, we further performed IVIVC analysis. The fraction permeated in vitro was obtained and then fitted using a Weibull model. Pharmacokinetic parameters from intravenous injection were used to numerically deconvolute the plasma PK profile of transdermal administration to obtain the fraction absorbed in vivo. The fraction absorbed in vivo and fraction permeated in vitro showed a linear relationship (Fig. 4), but the slope was not close to 1. The in vitro permeation and in vivo absorption had a ratio of 1.76 (1/slope).

Fig. 4.

The analysis of the predictive relationship between in vitro permeation and in vivo absorption of PAL-353.

Discussion

The major findings of the present study are that 1) we successfully developed a novel bioanalytical method, 2) we used that method to characterize the PK profile of PAL-353, 3) we demonstrated that PAL-353 has favorable PK properties for transdermal administration for CUD, and 4) we provided preliminary evidence of the capacity of rodent data to predict human skin flux or vice versa.

Although transdermal delivery system is well-known for the advantage in providing prolonged or sustained drug delivery/therapeutic effect, the removal of which in turn also allows for control over the duration of drug effect and the ease or termination of adverse effects. Whether an around-the-clock therapeutic effect is desirable depends on both the nature of the disease and the properties of the pharmacotherapy. Because of the well-known sleep-disrupting effects of stimulants, patients with CUD may show poor compliance with the dosage regimen. It may be desirable for the drug effect to intermittently stop between two doses. In addition to that, achieving rapid control over symptoms such as craving, is desirable. Hence, we propose that a rapid absorption followed by a sustained duration of action of 8–12 h would be ideal for CUD, similar to the clinical treatment of ADHD with stimulants [27]. Owing to its amphetamine-like properties, we postulated that PAL-353 might show a PK/PD correlation like amphetamine. We further hypothesized that such a profile of delivery can be achieved using transdermal formulation, yet whether the therapeutic effect may subside rapidly after the desired duration of action is highly dependent on the half-life of PAL-353. To advance the design and development of viable PAL-353 delivery systems, the assessment of the PK of PAL-353 is necessary and critical. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the PK of PAL-353 in vivo.

Intravenous bolus injection was performed to establish the PK of PAL-353. The semilogarithmic plasma concentration versus time profile obtained from intravenous bolus injection of PAL-353 at 5 mg/kg exhibited only one phase, indicating that a one-compartment model would fit the profile. Compared with previous research on the pharmacokinetics of two related compounds, amphetamine and methylphenidate, the elimination half-life and MRT for PAL-353 obtained in the current experiments were found to be similar to those reported for amphetamine (91 min and 95 min, respectively) in female Sprague Dawley rats in early pregnancy[28], but the elimination half-life for PAL-353 was 5.5 times the reported half-life reported for methylphenidate (24.6 min) [29]. Researchers utilized a subcutaneous osmotic mini-pump to provide continuous drug delivery while studying the chronic administration of amphetamine or related monoamine releasers for the treatment of CUD [30–32]. This regimen was effective, and importantly, continuous delivery from a subcutaneous pump closely resembles the continuous input function of a transdermal delivery system. A transdermal delivery system can be advantageous since it may allow for an intermittent termination of drug effects, and possibly minimize the sleep disruptive effects associated with these stimulants. In addition, being potentially tamper-resistant and offering a sustained release profile [33], a transdermal patch with the drug-in-adhesive matrix design for PAL-353 may be ideal for CUD. Stratum corneum, the uppermost layer of skin, is a lipid-rich barrier that protects the body from exogenous substances and thereby a significant barrier to drug delivery[34,35], but allows for some permeation of small, uncharged, moderately lipophilic compounds. The physicochemical properties of PAL-353 indicate that it could be a good transdermal drug candidate, since it is a small-molecule (molecular weight=153.2 g/mol) weak base (pKa=9.97) with moderate lipophilicity (logP=1.95) and low melting point, with the base form existing in the liquid state at room temperature. Therefore, in addition to obtaining primary PK parameters from intravenous bolus injection, such as half-life, area under the curve (AUC) and clearance, PK following transdermal administration was also assessed using the transdermal gel formulation. The purpose of using a gel vehicle is to help the drug stay on the skin, unlike when using a less viscousformulation. It was observed that the gel was visibly smooth and homogenous in texture and color when the gel was applied onto the skin. HPMC was chosen as the gel matrix because the incorporated PAL-353 free base could stay unionized to represent the drug existing form in a drug-in-adhesive transdermal patch design, where usually a unionized molecule is used, and a pH modifier is not included. Unlike Carbopol polymers whose gelation requires neutralization by a base and in turn affects the ionization of PAL-353 depending upon the final pH of the formulation, the composition and the preparation of HPMC gel (heat-induced gelation) are unlikely to cause the ionization of PAL-353 free base. The drug loading of 10% w/w for gel was selected based on the target drug loading in the prospective patch design (assuming a patch to deliver 23 mg of drug with an application area of 50 cm2, coat weight of 100 g/m2, and percentage delivery of 50%). The first-line treatment for ADHD, amphetamine and methylphenidate have similar potencies [36]. PAL-353 was found to show similar in vitro potency to d-amphetamine for dopamine release, and the target dose delivered was therefore derived from extended-release amphetamine medications [37]. As the 10% w/w gel did not cause visible skin reactions after the rat wore the gel for 24 h in preliminary studies, it was used to characterize the PK of PAL-353 following the transdermal administration. The gel dose of 10 mg/cm2 matched the coat weight of 100 g/m2 in the prospective patch design. The Cmax was observed at 1.5 h, suggesting an efficient delivery and a fast onset of action. Sustained delivery of PAL-353 was achieved by the transdermal gel. The plasma concentration was observed to drop to a low level right after the removal of the gel. Elimination of the drug from plasma between 9 to 12 h happened at a similar rate as the observed elimination phase of the intravenous group, evidenced by the paralleled plasma versus time profiles. These results suggest that a desirable quick clearance of PAL-353 will occur following patch exhaustion or removal. The plasma concentration then decreased at a slower speed (3.14-fold longer apparent half-life as compared to intrinsic half-life), indicating that there was a continuous absorption of the drug from the skin or the underlying tissue. The drug retention in the skin was considered low, since it did not increase the plasma concentration remarkably. The absolute bioavailability was 31.8%, and this was obtained under a non-occlusive condition. Indeed, drug loss might have happened due to the drug’s volatility and drug’ migration into Tegaderm adhesive and membrane. Tegaderm was chosen to prevent the gel from being removed as well as to match the non-occluded in vitro permeation set-up. The drug permeation was also studied for in vitro permeation across human epidermis. The applied gel dose of 10 mg/cm2 (100 g/m2) was a finite dose, which accounts for the observation that the steady state was maintained only until 9 h. Nevertheless, the in vitro permeation profile obtained, well fits the 8–12 h steady therapeutic drug concentration profile suggested for CUD treatment. The transdermal gels delivered PAL-353 at a high enough rate and with almost no lag time in vitro, suggesting the possibility of a rapid onset of action in vivo. These findings were verified by the rat PK results.

To further explore if there exists a potential correlation between the in vitro and in vivo results, though from different species, we performed level A IVIVC analysis. As per FDA, an IVIVC is to establish a predictive mathematical model describing the relationship between an in vitro property and a relevant in vivo response. To our best knowledge, the development of IVIVC for marketed passive transdermal patches has been only reported for estradiol and nicotine patches [38,38,39]. Interestingly, Yang et al. built level A IVIVC for marketed estradiol patches using a polynomial regression [38], which is different from a typical Level A IVIVC that usually shows a 1:1 relationship between in vitro and in vivo input following time scaling. Level A point-to-point correlation and multiple-point level C correlation are most informative for the regulatory agency. However, such correlations for topical/transdermal products have not been able to serve as a surrogate for in vivo PK studies yet. The challenges to establishing an excellent IVIVC for transdermal formulations were well summarized by Ghosh et al. [40]. Our exploratory work on the IVIVC analysis of PAL-353 transdermal formulation showed that a good correlation (r2=1) existed between in vitro and in vivo absorption. The reason that the ratio was not 1 could be attributed to several factors. The skin samples used in vitro and in vivo were from different species. Ideally, human in vivo data is the most relevant but is not practical to obtain in the preclinical stage. Moreover, a clearance mechanism does not exist in the receptor compartment in vitro, whereas the rate for the permeant to reach systemic delivery in vivo may be limited not only by the stratum corneum, but also by viable epidermis diffusion, capillary permeability and local blood flow [40]. Hence, the thickness of skin (epidermal, dermatomed or full-thickness) used in the in vitro permeation studies may also play a role in causing the deviation. The employment of full-thickness skin rather than dermatomed skin for in vitro permeation study involving microneedle treatment was found to correlate the in vivo data the best, as the full thickness skin displayed the in vivo diffusional resistance in the dermis [41]. Although FDA uses an IVIVC is to establish a predictive relationship in vitro assays and in vivo responses, it is important to note that establishing a linear point-to-point correlation also demonstrates the converse, that an in vivo absorption predicts the in vitro permeation. Human skin grafts are considered a gold-standard model of living human skin permeation. However, intact human skin samples are limited and require collection from human subjects, including first responders. It is encouraging the rat in vivo PK data are predictive of in vitro human skin permeation parameters, such as flux, as that suggests that these data are also predictive of absorption in living humans. Therefore, rodent in vivo data can be beneficial in predicting human PK parameters including the target therapeutically relevant dose, and may allow for predictions of both PD and PK pharmacologic metrics.

To facilitate the rat PK study, a novel bioanalytical method was developed. To our knowledge, there is no literature report on a validated bioanalytical assay using liquid-liquid extraction and LC-MS/MS for determining PAL-353 in rat plasma. Liquid-liquid extraction of PAL-353 from plasma was selected since it is preferable for minimizing matrix effect than protein precipitation, and for a lower cost than solid phase extraction [23]. Following liquid-liquid extraction, sample enrichment procedures before drug analysis are often needed, as the pretreatment can cause sample dilution and/or contain solvent unamenable to direct analysis. PAL-353 (pKa=9.97) is fully ionized at a physiological pH. An alkalization step is involved in obtaining the free base form so that PAL-353 will largely partition into the water-immiscible organic extraction solvent. During our method development, the volatility of PAL-353 free base caused extensive drug loss during sample enrichment using a SpeedVac concentrator, which condenses the sample by applying vacuum and low heat (30 °C) while spinning. To tackle this issue, volatile acid (diluted hydrochloric acid) was added to fully ionize PAL-353 so that the drug could be maintained in the solid salt form during the enrichment. The excess acid evaporates along with other solvents. The validation results reported herein demonstrate that this sensitive LC-MS/MS method coupled with a simple liquid-liquid extraction method for quantifying PAL-353 in rat plasma has satisfactory accuracy, precision, recovery and matrix effects.

Conclusion

The PK of PAL-353 was characterized in rats, and a novel bioanalytical method was developed and applied to the current PK study. The PK profile of PAL-353 following transdermal administration supports its use for CUD and other indications, further supporting the rationale for using the transdermal route of delivery for PAL-353. We also have provided preliminary evidence of the capacity of rodent data to predict human skin flux.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by the Georgia Research Alliance based in Atlanta, Georgia by grant number GRA.VL17.11 (Murnane and Banga - Multiple Principal Investigators) as well as by the National Institute on Drug Abuse by grant number DA12970 (Blough - Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors has a financial relationship with the sponsor of the research, which was the Georgia Research Alliance. The Georgia Research Alliance is a state government funded agency.

Ajay Banga and Kevin Murnane are cofounders of DD Therapeutics, a for-profit startup company that aims to commercialize drug-delivery technology.

Ajay Banga, Kevin Murnane, and Ying Jiang are co-inventors on a patent pending for transdermal use of phenethylamine monoamine releasers that is owned by Mercer University.

Azizi Ray, Mohammad Shajid Ashraf Junaid, Sonalika Arup Bhattaccharjee, Kayla Kelley, and Bruce Blough have no conflicts of interest to declare.

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Vocci FJ, Acri J, Elkashef A. Medication development for addictive disorders: The state of the science. Vol. 162, American Journal of Psychiatry; 2005. p. 1432–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vocci FJ, Appel NM. Approaches to the development of medications for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Vol. 102, Addiction; 2007. p. 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkow ND, Li T-K. Science and Society: Drug addiction: the neurobiology of behaviour gone awry. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004. December;5(12):963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howell LL, Murnane KS. Nonhuman Primate Neuroimaging and the Neurobiology of Psychostimulant Addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008. October;1141(1):176–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen ML, Kessler E, Murnane KS, McClung JC, Tufik S, Howell LL. Dopamine transporter-related effects of modafinil in rhesus monkesy. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010. June 13;210(3):439–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murnane KS, Howell LL. Neuroimaging and drug taking in primates. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011. July 1;216(2):153–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell LL, Murnane KS. Nonhuman Primate Positron Emission Tomography Neuroimaging in Drug Abuse Research. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011. May;337(2):324–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell LL, Kimmel HL. Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant addiction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(1):196–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reith MEA, Meisler BE, Sershen H, Lajtha A. Structural requirements for cocaine congeners to interact with dopamine and serotonin uptake sites in mouse brain and to induce stereotyped behavior. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35(7):1123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergman J, Madras BK, Johnson SE, Spealman RD. Effects of cocaine and related drugs in nonhuman primates. III. Self-administration by squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banks ML, Blough BE, Negus SS. Effects of monoamine releasers with varying selectivity for releasing dopamine/norepinephrine versus serotonin on choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 2011. December;22(8):824–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negus SS, Baumann MH, Rothman RB, Mello NK, Blough BE . Selective suppression of cocaine-versus food-maintained responding by monoamine releasers in rhesus monkeys: benzylpiperazine, (+)phenmetrazine, and 4-benzylpiperidine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009. April;329(1):272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Negus SS, Mello NK. Effects of chronic d-amphetamine treatment on cocaine- and food-maintained responding under a second-order schedule in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(1):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks ML, Blough BE, Fennell TR, Snyder RW, Negus SS. Effects of phendimetrazine treatment on cocaine vs food choice and extended-access cocaine consumption in rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(13):2698–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimmel HL, Manvich DF, Blough BE, Negus SS, Howell LL. Behavioral and neurochemical effects of amphetamine analogs that release monoamines in the squirrel monkey. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;94(2):278–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski J, Shearer J, Merrill J, Negus SS. Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. In: Addictive Behaviors. 2004. p. 1439–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Negus SS, Henningfield J. Agonist medications for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. Vol. 40, Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015. p. 1815–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puri A, Murnane KS, Blough BE, Banga AK. Effects of chemical and physical enhancement techniques on transdermal delivery of 3-fluoroamphetamine hydrochloride. Int J Pharm. 2017;528(1–2):452–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y, Murnane KS, Bhattaccharjee SA, Blough BE, Banga AK. Skin delivery and irritation potential of phenmetrazine as a candidate transdermal formulation for repurposed indications. AAPS J 2019. July 31;21(4):70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganti SS, Bhattaccharjee SA, Murnane KS, Blough BE, Banga AK. Formulation and evaluation of 4-benzylpiperidine drug-in-adhesive matrix type transdermal patch. Int J Pharm. 2018. October 25;550(1–2):71–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volkow ND, Swanson JM. Variables that affect the clinical use and abuse of methylphenidate in the treatment of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2003. November;160(11):1909–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Wit H, Bodker B, Ambre J. Rate of increase of plasma drug level influences subjective response in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1992;107(2–3):352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers E, Wagrowski-Diehl DM, Lu Z, Mazzeo JR. Systematic and comprehensive strategy for reducing matrix effects in LC/MS/MS analyses. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;852(1–2):22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Jiang Y, Jing G, Tang Y, Chen X, Yang D, et al. A novel UPLC–ESI-MS/MS method for the quantitation of disulfiram, its role in stabilized plasma and its application. J Chromatogr B. 2013. October 15;937:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakshi P, Jiang Y, Nakata T, Akaki J, Matsuoka N, Banga AK. Formulation Development and Characterization of Nanoemulsion-Based Formulation for Topical Delivery of Heparinoid. J Pharm Sci. 2018. November;107(11):2883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badkar AV, Smith AM, Eppstein JA, Banga AK. Transdermal delivery of interferon alpha-2b using microporation and iontophoresis in hairless rats. Pharm Res. 2007;24(7):1389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volkow ND, Swanson JM. Reviews and Overviews Variables That Affect the Clinical Use and Abuse of Methylphenidate in the Treatment of ADHD. Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process. 2003;160(November):1909–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White S, Laurenzana E, Hendrickson H, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Gestation time-dependent pharmacokinetics of intravenous (+)-methamphetamine in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011. September 1;39(9):1718–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gal J, Hodshon BJ, Pintauro C, Flamm BL, Cho AK. Pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate in the rat using single-ion monitoring GLC-mass spectrometry. J Pharm Sci. 1977;66(6):866–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negus SS, Henningfield J. Agonist medications for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015. July;40(8):1815–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Czoty PW, Tran P, Thomas LN, Martin TJ, Grigg A, Blough BE, et al. Effects of the dopamine/norepinephrine releaser phenmetrazine on cocaine self-administration and cocaine-primed reinstatement in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2015. July 13;232(13):2405–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmer BA, Chiodo KA, Roberts DCS. Reduction of the reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine by continuous d-amphetamine treatment in rats: Importance of active self-administration during treatment period. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014. March;231(5):949–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saroha K, Yadav B, Sharma B. Transdermal patch: A discrete dosage form. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2011;3(3):98–108. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banga AK. Transdermal and Intradermal Delivery of Therapeutic Agents Application of Physical Technologies. 2012;38(4):513–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elias PM. Epidermal lipids, barrier function, and desquamation. J Invest Dermatol. 1983. June;80(s6):44s–49s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexoff DL, Volkow ND, Schiffer WK, Logan J, Dewey SL, Fowler JS. Therapeutic doses of amphetamine or methylphenidate differentially increase synaptic and extracellular dopamine. Synapse. 2005;59(4):243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wee S Relationship between the Serotonergic Activity and Reinforcing Effects of a Series of Amphetamine Analogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;313(2):848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pavurala N, Khan MA, Krishnaiah YSR, Yang Y, Manda P. Development and validation of in vitro–in vivo correlation ( IVIVC ) for estradiol transdermal drug delivery systems. J Control Release. 2015. July 28;210:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin SH, Thomas S, Raney SG, Ghosh P, Hammell DC, El-Kamary SS, et al. In vitro–in vivo correlations for nicotine transdermal delivery systems evaluated by both in vitro skin permeation (IVPT) and in vivo serum pharmacokinetics under the influence of transient heat application. J Control Release. 2018. January 28;270:76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghosh P, Milewski M, Paudel K. In vitro/in vivo correlations in transdermal product development. Vol. 6, Therapeutic Delivery; 2015. p. 1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Milewski M, Paudel KS, Brogden NK, Ghosh P, Banks SL, Hammell DC, et al. Microneedle-assisted percutaneous delivery of naltrexone hydrochloride in yucatan minipig: In vitro-in vivo correlation. Mol Pharm. 2013. October 7;10(10):3745–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]