Abstract

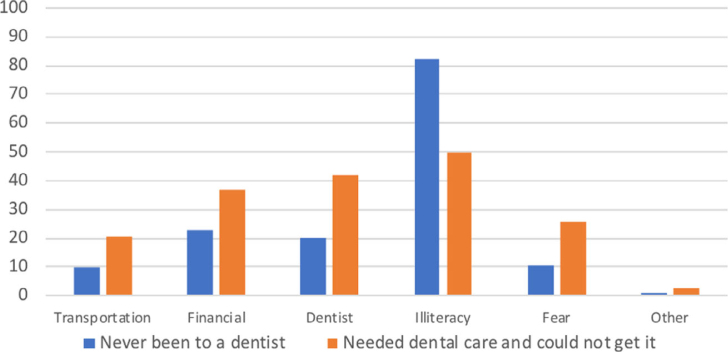

Objectives: This study used Andersen’s predisposing, enabling and need behavioural model to predict factors that influence utilisation of oral health services for children in Saudi Arabia. Methods: The model was tested in a random sample of parents of third- and eighth-grade children in Jeddah (n = 1,668) using the access to care questionnaire adapted from the Basic Screening Survey. Predisposing (sex, parent education, nationality); enabling (school type, family income, government financial support, health insurance); and need for dental care (examined or perceived) were modelled to assess children’s use of dental services. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were conducted. Significant findings were reported at P ≤ 0.05. Results: About 84% of parents responded to our questionnaire (n = 1,397). One in four children have never visited a dentist. Our findings indicate that need and predisposing factors explained oral health services’ use among younger children, whereas need, predisposing and enabling factors predicted use of services among older children. Perceived barriers to dental care for children who never went to a dentist and for those who needed dental care and could not get it included oral health illiteracy (82.3%, 49.7%), dentist-related (19.9%, 42.1%), financial (22.8%, 37.1%) and transportation (9.8%, 20.8%), respectively. Conclusions: The need for dental care, predominantly for illness-related dental care, drives utilisation of dental health services among children in Saudi Arabia. Enhancing oral health literacy and mitigating organisational and financial barriers to dental care for families will increase children’s access to quality oral healthcare, and promote better oral health practices and outcomes.

Key words: Utilisation, oral health services, oral health literacy, children, Basic Screening Survey, Saudi Arabia

INTRODUCTION

Poor oral health can adversely impact the childrens’ quality of life, school performance, self-esteem, and their success later in life1. Considerable missed school days, lost parental working days, and costly treatment are associated with children’s poor oral health and lack of access to dental care2. Globally, between 60% and 90% of children have experienced dental caries, with most disease remaining untreated3. In low- and middle-income countries and in a number of high-income countries, oral healthcare services remain unaffordable or inaccessible for large segments of the population3. Dental care has been recognised as the most prevalent unmet health need of US children4.

The burden of oral diseases in Saudi Arabia is high. An analysis of the Saudi Health Information Survey (SHIS) found daily brushing and flossing uncommon, and only 12% of individuals ≥15 years reported a visit to a dental clinic in the previous year for routine dental care, and nearly half (49%) went for urgent care5. A systematic review of dental caries in Saudi children and youth reported a caries prevalence of 80% in the primary and 70% in the permanent dentition6. Furthermore, 38%, 30% and 14% of school children in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia have never visited a dentist, visited a dentist for dental pain, and visited for regular dental checkups, respectively7.

Access to healthcare is defined as the ‘timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes’8. Access to oral healthcare underscores both the availability and use of care. All children should be able to access and utilise safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable and patient-centred oral health services1. Improving access of children to quality oral healthcare is critical for their overall health and well-being9. It enables timely receipt of oral health education, necessary preventive dental care, and early detection and treatment of oral disease8. Numerous and complex factors including social, cultural, economic, structural and geographic contribute to poor oral health and lack of access to oral healthcare8.

Andersen proposed using the predisposing, enabling and need (PEN) behavioural model of health services use to predict or explain use of health services10. According to the PEN model, utilisation of healthcare services is an interplay of three categories of factors: (i) Predisposing – demographic and social attributes that affect a person’s attitudes and valuation of health, which sequentially predispose a person to use care; (ii) Enabling – availability of health personnel and facilities in the community as well as personal resources such as income and health insurance that enable a person to access care; and (iii) Need – a person’s perception of own oral health need or professional judgement for needed care. In Saudi Arabia, the current system for the delivery of health services, including dental care, is governed and is largely (60%) provided, free of charge, by the Ministry of Health11. It is interesting to test the PEN model in a nation where access to and utilisation of health services are available free of charge to its people.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the association between childrens’ access to dental healthcare, and PEN factors.

METHODS

Study design and sample selection

The schools in Saudi Arabia are segregated by sex and are organised according to their geographic location in the city. In this study, 24 elementary and middle schools were randomly selected from Jeddah city schools list to represent a cross-section of male and female elementary and middle school students in different geographic locations in Jeddah. All third- and eighth-grade students in these schools were recruited (n = 1,668). The assessment of these children who have had their permanent first and second molars for some time allows for a more meaningful assessment of access to preventive dental care.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (protocol no. 429/014-9). Written permissions from the Director of the Department of Education and from the principals of the selected schools were obtained.

Access to dental care questionnaire

A parent questionnaire and a cover letter explaining the study purpose and protocol were sent home with the students to their parents on the first school visit. Returning the questionnaire was considered as a consent from the parents to have their child participate in the study. This process was approved by the ethics committee. The questionnaire was adapted from the ‘Basic Screening Survey’ (BSS) manual questions12, with some additional questions. It was translated from English to Arabic and then back-translated into English to ensure that the meaning was retained13. Information on sociodemographic characteristics, parents’ perception of their child’s oral health, medical insurance coverage and access to dental care was collected from the parents. Information on school financial aid was acquired from school counselors. Following the initial visit, the schools were visited several times to examine the participating students and collect returned questionnaires. Reminder letters and mobile phone messages were sent to parents who did not return the questionnaires, and phone calls were made to obtain missing information on important questions.

Oral examination

The students who returned their questionnaires underwent a dental examination. The dental examination was performed following the BSS approach, which is planned to monitor the prevalence of caries, use of fissure sealants, treatment urgency and access to dental care among children and adults in community-based settings12.

Four clinical examiners were trained according to the BSS criteria12. They attended a 2-hour presentation and a 3-hour clinical training session administered by the principal investigator (DA). Before the commencement of the study, the trainer and all the examiners independently screened 20 children attending KAU dental clinics at two time-points, 1 week apart, to determine intra- and inter-examiner reliability. The percentage of agreement for inter- and intra-examination reliability for detecting caries was high (90%).

During the study, the oral examinations were performed in the children’s classrooms to minimise disruption in the school routine. An examination station was set up in the corner of the participating classroom, and the students were invited one by one to undergo a dental examination. The child was seated on a regular chair, and a team of an examiner and a recorder completed the oral examination. Headlamps were used by the examiners, along with disposable mouth mirrors and toothpicks. An oral health examination form was completed by the recorder for each student. The oral examinations were conducted between April and June 2009.

Study variables

The dependent variable, access to dental care, was assessed by collecting information on whether the child had ever visited a dentist (yes/no). The predictors were categorised based on the PEN factors suggested by Andersen10.

The main independent variable of interest was the need factor, which refers to illness level. Caries experience (examined need) and parents’ self-perceptions about their child’s oral health that reflect future need for care (perceived need) were both used to measure need for dental care. Caries experience was assessed clinically by the dental examiners, and recorded as present if at least one tooth had untreated caries, a filling or was missing due to caries. The parents’ self-perception was measured by asking parents to rate their perception of their child’s oral health on a 3-point scale: 3, excellent; 2, good; and 1, poor. For analytical purposes, responses 3 and 2 were merged as good.

The predisposing factors were sex, nationality (Saudi or non-Saudi) and parental educational level (primary school diploma, middle school diploma, some high school, HS diploma, college, post-graduate and other). For analytical purposes, the responses were re-categorised as < high school diploma, high school diploma and > high school diploma; the highest level of education of either parent was considered the ‘parental educational level’.

The enabling factors were school type of funding (public or private), family monthly income in Saudi Riyals (SAR) (≤ 3,000, > 3,000 to < 10,000, or ≥ 10,000; 1 US Dollar = 3.75 SAR), government financial support (yes/no) and medical insurance (yes/no). In Saudi Arabia, dental insurance falls under medical insurance; therefore, information on medical insurance was used in all analyses. As very few children received financial aid from the school (2%), we were unable to assess this factor.

To identify existing barriers of access to dental care for children, the parents of children who have ‘never visited a dentist’ and those who ‘needed to visit a dentist and could not go’ were asked to check several listed reasons that apply for not obtaining dental care. For analytical purposes, these reasons were re-grouped into six categories: (i) transportation barriers: no one would take my child to the dentist, and no transportation; (ii) financial barriers: no money, and no dental insurance; (iii) dentist-related barriers: the dentist is too far away, the dentist is hard to reach, the appointment times were unsuitable, long wait times to schedule appointments, a long wait time in the office, no paediatric dentist is available, and I do not know where to go; (iv) health literacy-related barriers: my child is too young, my child has baby teeth, my child has no dental problems, I treat my child myself, no time, and I don’t trust the dentist; (v) fear; and (vi) others.

Statistical analyses

The questionnaire and oral examination data were entered into a Microsoft Office Access 2009 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed using Stata 12.1 (Stata Corp. LP, College Station, TX, USA). Categorical variables are presented as percentages and frequencies. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated from univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Each of the need variables was assessed in a separate model, and separate models were generated for the two different grade levels (grade 3 and grade 8). The frequencies and percentages for each barrier domain were calculated.A P-value of 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

RESULTS

All of the participating students (n = 1,668) received a dental examination; however, only 92% (n = 1,535) of their parents returned the questionnaire. In addition, 138 of the returned questionnaires were missing information regarding variables of interest yielding a final response rate of 83.75%. The final sample size was 1,397. Non-respondents were slightly older, more likely non-Saudi, more likely to attend private schools, and were less likely to have caries experience compared with included participants. Nonetheless, there was no difference with regard to sex, parental educational level or income (data not shown).

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of the study participants. Of the participants, 59% were male children and 68% were Saudi. The majority (85%) of the children were enrolled in public schools. Only 44% of the children’s parents had > HS diploma, and 22% had a monthly income ≥ 10,000 SAR. The majority (84%) of the children had caries experience, 40% had a toothache more than once in the past 6 months, and most (71%) need some type of dental care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Variable | N (%)(n = 1,397) |

|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | |

| Age | |

| < 9 years | 695 (49.8) |

| 9–14 years | 550 (39.4) |

| > 14 years | 152 (10.9) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 829 (59.3) |

| Female | 568 (40.7) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 946 (67.7) |

| Non-Saudi | 451 (32.3) |

| Parent education | |

| < HS | 414 (29.6) |

| HS | 372 (26.6) |

| > HS | 611 (43.7) |

| Enabling factors | |

| Family monthly income (SAR) | |

| ≤ 3,000 | 539 (38.6) |

| > 3,000 to < 10,000 | 557 (39.9) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 301 (21.6) |

| Government financial support | 51 (3.7) |

| School type | |

| Public | 1,193 (85.4) |

| Private | 204 (14.6) |

| School financial support | 32 (2.29) |

| Medical insurance | 349 (25.0) |

| Need factors | |

| Caries experience | 1,177 (84.3) |

| Toothache > 1 in past 6 months | |

| Yes | 559 (40.07) |

| No | 763 (54.70) |

| Don’t know | 73 (5.23) |

| Treatment urgency | |

| No obvious problem | 403 (28.9) |

| Early dental care | 799 (57.2) |

| Urgent care | 195 (14.0) |

| Perception of child’s oral health | |

| Excellent | 334 (23.9) |

| Average | 939 (67.2) |

| Poor | 124 (8.9) |

Characteristics of children’s utilisation of dental care

Approximately a quarter (26%) of all children have not been to a dentist before, and a third (31%) needed dental care in the previous year and could not get it. Among those who reported ever visiting a dentist (n = 1,041, 74.5%), 62% reported a visit in the past year. Dental caries (38.4%) and toothache (43.8%) were the most commonly reported reasons for having a past dental visit (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of children’s utilisation of dental care

| Variable | Grade 3 N (%) (n = 820) | Grade 8 N (%) (n = 577) | Total N (%) (n = 1,397) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last dental visit | |||

| Never | 237 (28.90) | 119 (20.62) | 356 (25.48) |

| < 6 months | 263 (32.07) | 181 (31.37) | 444 (31.78) |

| 6 months to 1 year | 125 (15.24) | 80 (13.86) | 205 (14.67) |

| > 1 year but < 3 years | 118 (14.39) | 82 (14.21) | 200 (14.32) |

| > 3 years | 37 (4.51) | 63 (10.92) | 100 (7.16) |

| DK | 40 (4.88) | 52 (9.01) | 92 (6.59) |

| Reason last dental visit* | |||

| Check-up | 119 (20.41) | 139 (30.35) | 258 (24.78) |

| Cleaning | 38 (6.52) | 63 (13.76) | 101 (9.70) |

| Toothache | 250 (42.88) | 150 (32.75) | 400 (38.42) |

| Caries | 299 (51.29) | 157 (34.28) | 456 (43.80) |

| Treatment | 40 (6.86) | 48 (10.48) | 88 (8.45) |

| Other | 63 (10.81) | 59 (12.88) | 122 (11.72) |

| Place last dental visit | |||

| Private dental clinic | 237 (40.65) | 172 (37.55) | 409 (39.44) |

| Private hospital | 170 (29.16) | 139 (30.35) | 309 (29.80) |

| Primary health centre | 67 (11.49) | 40 (8.73) | 107 (10.32) |

| Public hospital | 44 (7.55) | 67 (14.63) | 111 (10.70) |

| School clinic | 12 (2.06) | 16 (3.49) | 28 (2.70) |

| University dental clinic | 21 (3.60) | 11 (2.40) | 32 (3.09) |

| Other | 29 (4.97) | 12 (2.62) | 41 (3.95) |

| Needed a visit in previous year and could not go | |||

| Yes | 201 (34.60) | 117 (25.38) | 318 (30.52) |

| No | 353 (60.76) | 315 (68.33) | 668 (64.11) |

| DK | 27 (4.65) | 29 (6.29) | 56 (5.37) |

| Ever visited a dentist (child’s response) | |||

| Yes | 520 (63.41) | 399 (69.15) | 919 (65.78) |

| No | 300 (36.59) | 178 (30.85) | 478 (34.22) |

| Ever visited a dentist (parent’s response) | |||

| Yes | 583 (71.10) | 458 (79.38) | 1,041 (74.52) |

| No | 237 (28.90) | 119 (20.62) | 356 (25.48) |

DK, do not know.

Some numbers do not add up to the total because of missing values.

Participants checked more than one answer.

Examined dental care need and utilisation of dental care

Third-grade children

The results from the logistic regression analysis of caries experience (examined need) and having ever visited a dentist among third-grade children are presented in Table 3. Parents of children with caries experience were three times more likely to report having ever visited a dentist compared with those whose children have never visited a dentist (OR = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.7–4.7) after adjusting for other variables. Of the predisposing factors, parents who had > HS diploma were twice as likely to report having ever visited a dentist compared with those with lower educational levels, after adjusting for other factors (OR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.3–3.1). The enabling factors did not seem to affect dental visits.

Table 3.

Regression model of the relationship between examined need (caries experience) and having ever visited a dentist among third-grade children

| Variable | Dentist never visited |

Dentist ever visited |

Univariate logistic regression |

Multivariate logistic regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 237 | N = 583 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (I) Need factor | ||||

| Caries experience | ||||

| Yes | 203 | 548 | 2.6 (1.6–4.3)* | 2.8 (1.7–4.7)* |

| No | 34 | 35 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (II) Predisposing factors | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 106 | 246 | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| Male | 131 | 337 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Saudi | 138 | 356 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) |

| Non-Saudi | 99 | 227 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Parent education | ||||

| > HS | 76 | 282 | 1.9 (1.3–2.8)* | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)* |

| HS | 92 | 165 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) |

| < HS | 69 | 136 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (III) Enabling factors | ||||

| School type | ||||

| Private | 32 | 75 | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

| Public | 205 | 508 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family monthly income (SAR) | ||||

| > 3,000 to < 10,000 | 86 | 247 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 38 | 102 | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) |

| ≤ 3,000 | 113 | 234 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Government financial support | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 12 | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.6) |

| No | 228 | 571 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 129 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) |

| No | 194 | 454 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Logistic regression: # observations = 820, LR χ2(10) = 39.86, Prob > χ2 = 0.0000,

Log likelihood = −473.1166, Pseudo R2 = 0.0404.

Significant findings.

Eighth-grade children

As illustrated in Table 4, caries experience was also significantly related to having ever visited a dentist (OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.4–3.8) among eighth graders adjusted for all other variables. Among the predisposing variables, parents of female students were twice as likely to report having ever visited a dentist compared with parents of male students after adjusting for other factors (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.4–4.0).

Table 4.

Regression model of the relationship between examined need (caries experience) and having ever visited a dentist among eighth-grade children

| Variable | Dentist never visited |

Dentist ever visited |

Univariate logistic regression |

Multivariate logistic regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 119 | N = 458 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (I) Need factor | ||||

| Caries experience | ||||

| Yes | 79 | 347 | 1.6 (1.0–2.4) | 2.3 (1.4–3.8)* |

| No | 40 | 111 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (II) Predisposing factors | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 25 | 191 | 2.7 (1.7–4.3)* | 2.4 (1.4–4.0)* |

| Male | 94 | 267 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Saudi | 81 | 371 | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)* | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) |

| Non-Saudi | 38 | 87 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Parental education | ||||

| > HS | 32 | 221 | 3.2 (2.0–5.1)* | 1.6 (0.9–3.1) |

| HS | 21 | 94 | 2.1 (1.2–3.6)* | 1.5 (0.8–2.8) |

| < HS | 66 | 143 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (III) Enabling factors | ||||

| School type | ||||

| Private | 6 | 91 | 4.7 (2.0–11.0)* | 2.2 (0.8–6.1) |

| Public | 113 | 367 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family monthly income (SAR) | ||||

| > 3,000 to < 10,000 | 41 | 183 | 2.1 (1.4–3.4)* | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 16 | 145 | 4.3 (2.4–7.9)* | 1.8 (0.8–4.0) |

| ≤ 3,000 | 62 | 130 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Government financial support | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 22 | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 1.2 (0.5–3.1) |

| No | 111 | 436 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medical insurance | 1 | |||

| Yes | 23 | 54 | 2.11 (1.3–3.5)* | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) |

| No | 96 | 304 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Logistic regression: # observations = 577, LR χ2(10) = 61.92, Prob > χ2 = 0.0000, Log likelihood = −262.69071, Pseudo R2 = 0.1054.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Significant findings.

Perceived dental care need and utilisation of dental care

Third-grade children

The results from the logistic regression analysis of parents’ self-perception of their child’s oral health and having ever visited a dentist among third-grade children are shown in Table 5. Children of parents who perceived that their child had poor oral health were almost three times more likely to report having ever visited a dentist compared with children of parents who perceived that their child had good oral health, adjusted for all variables (OR = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.7–3.8). Children of parents with > HS diploma were twice as likely to report having ever visited a dentist than children of parents with < HS diploma after adjusting for other variables (OR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.2–3.1). Enabling factors did not seem to be associated with having ever visited a dentist.

Table 5.

Regression model of the relationship between parents’ self-perception of their child’s oral health and having ever visited a dentist among third-grade children

| Variable | Dentist never visited |

Dentist ever visited |

Univariate logistic regression |

Multivariate logistic regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 237 | N = 583 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (I) Need factor | ||||

| Perception of child’s oral health | ||||

| Poor | 173 | 506 | 2.4 (1.7–3.5)* | 2.6 (1.7–3.8)* |

| Good | 64 | 77 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (II) Predisposing factors | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 106 | 246 | 2.7 (1.7–4.3)* | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) |

| Male | 131 | 337 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Saudi | 138 | 356 | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)* | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) |

| Non-Saudi | 99 | 227 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Parent education | ||||

| > HS | 76 | 282 | 3.2 (2.0–5.1)* | 2.0 (1.2–3.1)* |

| HS | 92 | 165 | 2.1 (1.2–3.6)* | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

| < HS | 69 | 136 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (III) Enabling factors | ||||

| School type | ||||

| Private | 32 | 75 | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

| Public | 205 | 508 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family monthly income (SAR) | ||||

| > 3,000 to < 10,000 | 86 | 247 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 38 | 102 | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) |

| ≤ 3,000 | 113 | 234 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Government financial support | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 12 | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.6) |

| No | 228 | 571 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 129 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| No | 194 | 454 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Logistic regression: # observations = 820, LR χ2(10) = 47.10, Prob > χ2 = 0.0000, Log likelihood = −469.49629, Pseudo R2 = 0.0478.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Significant findings.

Eighth-grade children

The results presented in Table 6 show that children of parents who perceived that their child had poor oral health were almost four times more likely to report having ever visited a dentist compared with children of parents who perceived that their child had good oral health, adjusted for all other variables (OR = 3.7, 95% CI: 2.3–6.0). Among the predisposing factors, females were twice as likely as male students to have ever visited a dentist, adjusted for all other variables (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.4–4.0). Among the enabling factors, children attending private schools were three times more likely to have ever visited a dentist compared with public school children after adjusting for other factors (OR = 3.3, 95% CI: 1.1–9.4).

Table 6.

Regression model of the relationship between parents’ self-perception of their child’s oral health and having ever visited a dentist among eighth-grade children

| Variable | Dentist never visited |

Dentist ever visited |

Univariate logistic regression |

Multivariate logistic regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 119 | N = 458 | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| (I) Need factor | ||||

| Perception of child’s oral health | ||||

| Poor | 63 | 321 | 2.1 (1.4–3.1)* | 3.7 (2.3–6.0)* |

| Good | 56 | 137 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (II) Predisposing factors | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 25 | 191 | 2.7 (1.7–4.3)* | 2.4 (1.4–4.0)* |

| Male | 94 | 267 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Saudi | 81 | 371 | 2.0 (1.3–3.1)* | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

| Non-Saudi | 38 | 87 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Parent education | ||||

| > HS | 32 | 221 | 3.2 (2.0–5.1)* | 1.7 (0.9–3.3) |

| HS | 21 | 94 | 2.1 (1.2–3.6)* | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) |

| < HS | 66 | 143 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| (III) Enabling factors | ||||

| School type | ||||

| Private | 6 | 91 | 4.7 (2.0–11.0)* | 3.3 (1.1–9.4)* |

| Public | 113 | 367 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family monthly income (SAR) | ||||

| > 3,000 to < 10,000 | 41 | 183 | 2.1 (1.4–3.4)* | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) |

| ≥ 10,000 | 16 | 145 | 4.3 (2.4–7.9)* | 1.7 (0.7–4.1) |

| ≤ 3,000 | 62 | 130 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Government financial support | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 22 | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 1.0 (0.4–2.4) |

| No | 111 | 436 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 154 | 2.11 (1.3–3.5)* | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) |

| No | 96 | 304 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Logistic regression: # observations = 577, LR χ2(10) = 80.38, Prob> χ2 = 0.0000, Log likelihood = −253.46251, Pseudo R2 = 0.1369.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Significant findings.

Perceived barriers to dental care for children

Figure 1 presents the six categories of barriers reported by the parents who never took their child to see a dentist, and those who needed to go in the past year and could not go. Among those who have never been to a dentist, oral health illiteracy represented the main group of barriers (82.3%), followed by financial (22.8%), dentist-related (19.9%) and transportation (9.8%) barriers. The perception of a child having no dental problems emerged as the main oral health belief in the oral health illiteracy group (61.2%) for never ever taking a child to a dentist. Not having enough money (15.7%) was the most common reason reported in the financial barrier group; unsuitable appointment times (8.1%) and long wait times in the office (7.6%) were the most common reasons reported in the dentist-related barriers.

Figure 1.

Parents’ perceived barriers to access to dental care for children.

Among children who needed to see a dentist in the previous year and could not go, oral health illiteracy was still ranked the highest (49.7%) compared with the other groups of barriers for not getting dental care when needed. Long wait time at the dental office and unsuitable appointment times were the most common reasons stated in the dentist-related barriers for needing dental care and not getting it (18.2%, 17.6%, respectively).

The enabling conditions for access to and utilisation of dental care, such as dentist-related, financial and transportation barriers, were more prevalent among parents who needed dental care in the previous year and could not go, compared with those who never took their children to see a dentist (42.1% vs. 19.9%, 37.1% vs. 22.8%, 20.8% vs. 9.8%, respectively). Fear of dentist was reported by 26% of the children who needed to go to a dentist in the past year and did not go compared with to only 10.7% of those who never went. Finally, oral health illiteracy was less prevalent in the group who needed dental care and could not go compared with the group who never visited a dentist (49.7% vs. 82.3%, respectively; see Table S1 for online review).

DISCUSSION

This study used the Andersen PEN behavioural model of health services’ utilisation to examine whether the need of children for dental care predicted the use of dental services controlling for other predisposing and enabling variables. Andersen’s model has been revised and expanded beyond the initial model, but we used the original model because of data availability and its relevance to our research question. Andersen argues that need is the most immediate cause of use of health services particularly in the presence of serious conditions, and that the purpose for care, whether preventive or illness-oriented, impacts patterns of seeking care. Because dental care is considered mostly voluntary, it is more likely explained by social structure, oral health beliefs and enabling factors10.

Our study found that one out of four children have never visited a dentist, and one in five could not get dental care when they needed it in the past 12 months. Our results showed that the greater the need for dental care, whether examined or perceived, the higher the use of dental services for children controlling for other variables. Our findings agree with the Andersen framework for access to dental care10. This is likely true because almost two-thirds (61%) of the study children who reported a visit to a dentist went for illness-related rather than prevention care. Our results disagreed with findings from a similar study of young children in the Eastern part of the country, where examined dental need or parents’ reports of toothache in their children in the past 6 months was not associated with dental services use after controlling for other variables7.

Our findings indicate that need and predisposing factors explained more of the variation in oral health services’ use among the younger children, whereas need, predisposing and enabling factors predicted more of the utilisation of services among the older children. It is not surprising that need on its own is a necessary and sufficient factor for predicting use of dental services as the majority of parents reported taking their children to a dentist when there is a problem. However, our ultimate goal is to increase utilisation of preventive dental services and to promote preventive care-seeking behaviour among children and their families to prevent the onset of dental disease and intervene early when needed.

Globally, the proportion of children who visit a dentist for regular or preventive dental care increases with age14. In the young age group, parents’ education and the level of their awareness play a major role in the decision-making process to take a child to a dentist whether for illness-related or preventive care8. Young children and those who are not able to communicate effectively are among the most vulnerable and underserved populations8. These children have higher prevalence of dental caries and higher unmet need for dental care8. Therefore, given that dental care is universally available in the country, parents’ education stands out as a major predisposing factor for dental services use for the very young. As a child grows older, their potential for visiting a dentist becomes better as they are able to clearly verbalise their needs, have more autonomy, and their needs for dental care are more unique and broader, beyond those of caries management and prevention15. Therefore, to be able to utilise dental care effectively, they have to be predisposed and must have the means (enabling factors) to do so.

While dental services are available to citizens at no cost, access to and utilisation of dental preventive services and management of oral disease are still a significant problem11. This finding is universal across countries, and remarkably is more common in higher-income compared with middle- or low-income countries16. The poor and disadvantaged population groups consistently have higher burden of oral disease and lower access to oral healthcare compared with better-off people17. Low level of education attainment, low income, and lack of or limited health insurance are cited as the main reasons for inequality in utilisation of dental services in the North Africa and Middle East region16.

Although we were unable to assess the effects of other components of the PEN model such as community enabling factors and health beliefs because of data unavailability, nearly 40% of the parents whose children needed dental care in the past year and could not get it reported problems with the oral health delivery system. These included lack of a dentist or a specialised dentist in the community, problems getting a dental appointment, and long wait times at the clinic. Long wait lists, availability of basic dental treatment only, and a perception of low quality of dental care in the government’s dental clinics compared with private dental offices were barriers reported in another study of access to dental services in Saudi Arabia11. Additionally, our study found that parental oral health illiteracy was the most commonly reported barrier for not seeking dental care for children, more so among those who have never been to a dentist. Our results support findings of a previous study that reported a sevenfold increase in the odds of attending regular dental visits among patients who received oral health instructions during a previous dental visit18. Therefore, utilisation of oral health services improves oral health literacy which, in turn, enhances utilisation of dental care.

Our study has limitations. Our analysis used cross-sectional data, hence the relationships found between dental services use and PEN factors do not imply a causal effect. In addition, data on some of the predisposing and enabling factors were self-reported, although most were easy to recall or cross-check with the student’s dental screening record. Finally, this study was conducted in children in Saudi Arabia and, therefore, the findings may not represent the structure and delivery of oral health services for populations in other countries.

Our findings suggest that children of parents with low education attainment are predisposed to lower use of dental services. Education attainment, a predisposing factor with low mutability, is correlated with health literacy, which if enhanced, will result in improved use of dental services and better oral health outcomes18, 19. Therefore, oral health literacy campaigns may alter a parent’s predisposition toward use of dental services and promote early preventive dental visits for their children. Promoting oral health and preventing oral disease among children especially those who are at risk for disease and underserved require effective integration of oral health into primary healthcare and public health intervention17. School-based health centres (SBHCs) are effective in mitigating the effects of personal factors, such as social, behavioural and financial, and organisational factors, on dental services’ use by bringing the needed dental services to children in schools20. This will reduce many of the reported barriers to dental care such as transportation issues, parent availability, and wait time at the dental clinics20. SBHCs are endorsed by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Community Preventive Services Task Force based on sufficient evidence of effectiveness in improving learning and health outcomes21, 22.

The ongoing reforms in the delivery of healthcare in Saudi Arabia with the renewed focus on primary healthcare and health promotion and primary prevention23, and the recent collaboration between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education in operating school health programmes24 will eventually enable more children to obtain timely preventive and treatment dental services, enhance oral health literacy of families, reduce disparities in oral health, and improve oral health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by a grant from King Abdulaziz University Deanship of Scientific Research (Grant No. 429/014-9).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Data accessibility

Data accessibility is available and can be uploaded as needed.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Parents’ perceived barriers to dental care for children who have never been to a dentist, and for those who needed to go in the previous year and could not go.

REFERENCES

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services . Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 2010. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General – Executive Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings C, Gander S, Grueger B, et al. Oral health care for children – a call for action. Paediatr Child Heal. 2013;18:37–43. doi: 10.1093/pch/18.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century–the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–23. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newacheck PW, McManus M, Fox HB, et al. Access to health care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2004;105(4 Pt 1):760–766. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, et al. Use of dental clinics and oral hygiene practices in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Int Dent J. 2016;66:99–104. doi: 10.1111/idj.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Agili DE. A systematic review of population-based dental caries studies among children in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2013;25:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AlHumaid J, El Tantawi M, AlAgl A, et al. Dental visit patterns and oral health outcomes in Saudi children. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2018;6:89–94. doi: 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_103_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen PE. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2003. The World Oral Health Report 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alshahrani AM, Ahmed RS. Health-care system and accessibility of dental services in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an update. J Int Oral Heal. 2016;8:883–887. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors. ASTDD Basic Screening Surveys [Internet]. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjri__BiLThAhWJsRQKHf_GD9AQFjACegQIBhAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.astdd.org%2Fbasic-screening-survey-tool%2F&usg=AOvVaw0Vl78yhjCaLhWC7AiBN_w. Accessed 3 April 2019

- 13.Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reda SM, Krois J, Reda SF, et al. The impact of demographic, health-related and social factors on dental services utilization: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2018;75:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silk H, Kwok A. Addressing adolescent oral health: a review. Pediatr Rev. 2017;38:61–68. doi: 10.1542/pir.2016-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reda SF, Reda SM, Murray Thomson W, et al. Inequality in utilization of dental services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:e1–e7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen PE. Strengthening of oral health systems: oral health through primary health care. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23(Suppl 1):3–9. doi: 10.1159/000356937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quadri FA, Jafari FA, Albeshri AT, et al. Factors influencing patients’ utilization of dental health services in Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2018;11:29–33. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewitt M, Health P, Practice PH. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013. Oral Health Literacy: Workshop Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arenson M, Hudson P, Lee NH, et al. The evidence on school-based health centers. A review. Glob Pediatr Heal. 2019;6:1–10. doi: 10.1177/2333794X19828745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Council on School Health School-based health center and pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2012;129:387–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knopf JA, Finnie RKC, Peng Y, et al. School-based health centers to advance health equity: A community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. Vision Realization Office. Healthcare Transformation Strategy [Internet]. Vision Realization Office; 2018. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/vro/Documents/Healthcare-Transformation-Strategy.pdf. Accessed 1 April 2019

- 24.Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. MOH: Healthy Schools Program Launched to Improve Student Health [Internet]; 2019. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Ads/Pages/Ads-2019-02-28-002.aspx. Accessed 1 April 2019

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data accessibility is available and can be uploaded as needed.