Abstract

Venous thromboembolisms and pulmonary embolisms are one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in pregnancy. The increased risk of thrombotic events caused by the physiological changes during pregnancy alone does not justify any medical antithrombotic prophylaxis. However, if there are also other risk factors such as a history of thromboses, hormonal stimulation as part of fertility treatment, thrombophilia, increased age of the pregnant woman, severe obesity or predisposing concomitant illnesses, the risk of thrombosis should be re-evaluated – if possible by a coagulation specialist – and drug prophylaxis should be initiated, where applicable. Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) are the standard medication for the prophylaxis and treatment of thrombotic events in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Medical thrombosis prophylaxis started during pregnancy is generally continued for about six weeks following delivery due to the risk of thrombosis which peaks during the postpartum period. The same applies to therapeutic anticoagulation after the occurrence of a thrombotic event in pregnancy; here, a minimum duration of the therapy of three months should also be adhered to. During breastfeeding, LMWH or the oral anticoagulant warfarin can be considered; neither active substance passes into breast milk.

Key words: thromboembolisms, pregnancy, anticoagulation, low-molecular-weight heparins, oral anticoagulants

Introduction

In comparison to non-pregnant women, pregnant women have a significantly increased risk of venous thrombotic events (VTE), that is, deep and superficial venous thromboses (“thrombophlebitis”) and consequent pulmonary artery embolisms. In the Western world, these events represent a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in pregnant women 1 . This means that VTEs are responsible for about 10 – 20% of all deaths within the scope of pregnancy 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 .

The incidence of pregnancy-associated VTEs is indicated at approx. 0.12% 11 , 12 ; in comparison to non-pregnant women of the same age, pregnant women thus have per se an approximately 4 – 5 times higher risk of VTE. This thrombotic risk which is alone elevated by the pregnancy increases further if additional predispositional and expositional risk factors for VTE are present in the pregnant woman. It should be pointed out in this regard that due to demographic changes with a significantly increasing maternal age at first pregnancy in recent decades – and thus a higher percentage of “older” pregnant women – the risk of thrombotic and thromboembolic events in the entire collective of pregnant women in industrial nations such as Germany is increasing further 4 , 9 .

The increased risk of thrombosis begins with the start of pregnancy, persists during pregnancy (or further increases throughout the course of the pregnancy) and reaches its maximum in the postpartum period; after delivery, the risk of thrombosis decreases over a period of approx. 6 weeks to the level prior to pregnancy. About 50% of pregnancy-associated VTEs occur during pregnancy itself and 50% in the “critical period” within six weeks after delivery 5 ; thus the risk of postpartum thrombosis is about 5 times higher than during pregnancy itself.

Prothrombotic Shifting of the Haemostatic Balance in Pregnancy

The physiological prothrombotic shift of the haemostatic balance in pregnancy is of major significance for the significantly increased risk of thrombosis in pregnant women in comparison to nonpregnant women. Procoagulatory factors increase (e.g. activities of the plasmatic coagulation factors), while coagulation components which control or curb the coagulation process significantly decrease; a good example of this is the physiological decrease in protein S activity in pregnancy. In addition, there is a modification of fibrinolysis, whereby the increase in plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1) in pregnancy has an antifibrinolytic effect and thus contributes to the prothrombotic shift of the haemostatic balance. The latter is also reflected in an increase in the activation markers of haemostasis (e.g. D-dimers, fibrin degradation products [FDP], thrombin-antithrombin complex [TAT] and prothrombin fragment) 9 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 .

In late pregnancy, the plasma volume increases by up to 1600 ml compared to the starting value 18 . This also contributes to venous stasis and an increased risk of coagulation in connection with a decreased venous return flow due to the increasing pressure of the gravid uterus on the vena cava.

Predispositional and Expositional Risk Factors

Predispositional and expositional risk factors favour the development of VTEs in pregnancy 19 ; here, predisposition means the individual predisposition of the pregnant woman to thrombotic events (intrinsic risk), while expositional risk factors are factors which act on the pregnant woman externally which situationally increase the risk of thrombosis (so-called “triggers”). Important risk factors for thrombotic events in pregnant women are listed in Table 1 . The most clinically relevant factors are discussed separately below.

Table 1 Important risk factors for VTEs in pregnancy.

| Category | Risk factor |

|---|---|

| General risk factors |

|

| Previous and concomitant illnesses |

|

| Complications of pregnancy and delivery |

|

| Iatrogenic risk factors |

|

| Thrombophilia | See Table 2 |

Previous history of thrombotic events

Previous deep venous thromboses and pulmonary artery embolisms, particularly spontaneous or hormonally triggered events – especially during administration of hormonal contraception – are associated with a significantly increased risk of recurrence during pregnancy. After spontaneous or hormonally triggered events, a risk of recurrence of approx. 10% during pregnancy can be assumed without adequate thrombosis prophylaxis and this can be even considerably higher if there are other predispositional and expositional risk factors 9 , 20 , 21 , 22 . Previous superficial venous thromboses (thrombophlebitis), depending on severity, are associated with a risk of VTE in pregnancy and the postpartum period which is about 10 times higher. This risk can be reduced to approx. 2 – 3% with adequate secondary prophylaxis.

Thrombophilia

Genetically determined thrombophilia

Genetically determined or acquired thrombophilia affects the VTE risk in pregnancy. The corresponding relative and absolute risks for carriers of genetically determined thrombophilic risk factors are compiled in Table 2 .

Table 2 Relative risk of VTE in pregnancy and absolute risk derived from this for women with significant hereditary thrombophilic risk factors, depending on the family history 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 .

| Risk factor | Relative thrombosis risk | Absolute thrombosis risk in pregnancy and postpartum period | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unremarkable family history | Positive family history | ||

| * Risk increase and absolute thrombosis risk in inhibitor deficiencies depending on the nature and degree of severity of the respective defect. | |||

| Factor V Leiden mutation | |||

|

8.32 | 0.8 – 1.2% | 3.1% |

|

34.4 | 3.4 – 4.8% | 14% |

| Prothrombin mutation (G20210A) | |||

|

6.8 | 0.6 – 1% | 2.6% |

|

26.4 | 2.6 – 3.7% | (?) |

| Factor V Leiden mutation and prothrombin mutation (G20210A) | |||

|

50 | 5% | (?) |

| Protein C deficiency* | 4.8 – 7.2 | 0.4 – 0.7% | 1.7% |

| Protein S deficiency* | 3.2 | 0.3 – 0.5% | 6.6% |

| Antithrombin deficiency* | 4.7 – 64 | 0.4 – 4.1% | 3.0% |

In addition to the established genetically determined risk factors for VTEs mentioned above, a number of other risk factors is described in the literature which may be associated with an increased risk of thrombosis in pregnancy or which, in the case of the simultaneous appearance with other thrombophilic risk factors, may modulate the risk of thrombosis caused by these factors. These include, for example, the homozygous variants (4G/4G) of the 4G/5G polymorphism of the plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1), the increase in the level of plasma coagulation factors, as well as the increase in lipoprotein (a) and homocysteine. The influence of these not generally accepted and subordinate risk factors on the risk of thrombosis in pregnancy is not precisely defined, nor is their interaction with other thrombophilic risk factors. Thus these factors should generally not be used to estimate the risk of thrombosis during pregnancy.

Acquired thrombophilia: Antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS)

Among the acquired coagulation disorders, APLS is considered to play a significant role in the development of thrombotic events during pregnancy 25 , 31 . In addition to venous and arterial thromboses, this clinical picture is characterised by a tendency for spontaneous miscarriages and other pregnancy complications. Antiphospholipid (APL) antibodies can be detected in affected persons, whereby APL antibodies active in coagulation (lupus anticoagulants) should be differentiated from those which have no effect on coagulation tests (in particular cardiolipin antibodies and β 2 glycoprotein-I antibodies). The diagnosis of an APLS can then only be made if at least one of the above clinical signs is present and one or more of the above APL antibodies can be verifiably detected in a chronological connection; by contrast, the findings of positive APL antibodies without a clinical correlation do not permit the diagnosis of an antiphospholipid syndrome, however allow an increased risk of complications to be suspected. Close management of asymptomatic pregnant women with increased APL antibodies is therefore recommended.

Older age during pregnancy

The influence of age of the pregnant woman on the risk of thrombosis has been investigated in numerous studies with results that have not been entirely consistent. Case-control studies revealed that the relative risk for pregnancy-associated VTEs at an age of > 35 years is approximately twice as high as at an age of ≤ 35 years 32 .

Obesity

Obesity is fundamentally associated with a slight increase in risk for VTEs. For pregnancy-associated VTEs, a relevant increase in risk has been demonstrated in the case of a body mass index (BMI) over 30 kg/m 2 9 , 33 , 34 . In a large population-based cohort study in the United States, pregnant women with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m 2 (measured before pregnancy) had an adjusted odds ratio for prenatal VTEs of 2.9 (95% confidence interval 2.2 – 3.8) and for postpartum VTEs of 3.6 (95% confidence interval 2.9 – 4.6), as compared to pregnant women of a normal weight 35 . In view of this finding, the authors of the study consider the significance of the risk factor of obesity in the current guidelines on VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy, for example from the ACCP (American College of Chest Physicians) 36 , RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) 32 and ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) 37 to be only inadequately represented. In the German S3 guideline on VTE prophylaxis as well, a BMI > 30 kg/m 2 is listed only as a risk factor for non-pregnant women and its relative significance is classified as “moderate” 38 .

Caesarean section

Compared to a spontaneous delivery, a Caesarean section is associated with a risk of postpartum thrombosis which is about twice as high 6 , however the absolute risk is still relatively low.

Infertility treatment

Nowadays, women with sterility or (recurrent) miscarriages frequently undergo “fertility treatments”. A component of these treatments is generally the application of sex hormones for hormone stimulation. As a result, depending on the nature and dosage of the hormone administered, an increase in the risk of thrombosis is induced, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy 39 , 40 , 41 ; this should therefore be taken into consideration clinically. Particularly after past thrombotic events and/or if clinically relevant thrombophilia is present, conducting hormone stimulation as part of infertility treatment may possibly be associated with an increased risk and there should therefore be a careful consideration of the risks and benefits, because hormone application is formally contraindicated if there is an existing tendency to develop a thrombosis. For patients at risk, interdisciplinary management by the infertility centre and a haemostaseological facility is recommended to precisely assess the risk of thrombosis and, where applicable, develop an optimal strategy for thrombosis prophylaxis during stimulation and in any subsequent pregnancy 9 , 42 .

Predisposing concomitant illnesses

Certain illnesses may be associated with an increase in the risk of thrombosis and thus also increase the VTE risk in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Cited examples of this include illnesses that are rheumatic in nature, chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) such as ulcerative colitis and Crohnʼs disease, as well as infections 43 , 44 , 45 . By contrast, uncomplicated varicosis of the lower extremities is associated with at most a slight increase in the risk of thrombosis in pregnancy.

Surgical procedures and immobilisation

Surgical interventions fundamentally significantly increase the risk of thrombosis 46 , whereby this may be increased even further by postoperative immobility or complications within the scope of the procedure (e.g. infection). Immobility during pregnancy and the postpartum period also represents a risk factor for VTEs, independent of an intervention. Where applicable, the risk of thrombosis during pregnancy must therefore be evaluated differently if there is immobilisation in addition to an existing predisposition to thrombotic events.

Estimation of the Thrombotic Risk in Pregnancy

To clarify the need for medical thrombosis prophylaxis during pregnancy, an estimation of the risk of thrombosis is necessary. For this purpose, all known predispositional and expositional risk factors of the pregnant woman must be taken into account 9 , 32 , 36 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 .

The rationale for conducting medical thrombosis prophylaxis in pregnancy is that the prothrombotic shift of the haemostatic balance, together with predispositional and expositional risk factors, can lead to an imaginary “critical threshold” being exceeded which then leads to the manifestation of thrombotic events ( Fig. 1 ). Special risk scores for pregnant women have been developed based on this concept 32 , 52 . For this purpose, a sum score is formed from the available individual factors weighted according to their prothrombotic relevance and this score provides information on the level of the overall risk of the pregnant woman for VTEs. Such scores can be very helpful for making a decision for or against medical thrombosis prophylaxis or for referring the patient to a haemostaseologist.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the individual risk of thrombosis during pregnancy. If the total risk exceeds an imaginary “critical threshold” (dashed line), there is a manifestation of the thrombotic event.

The significance of any hereditary and/or acquired thrombophilic risk factors for the risk of thrombosis in pregnancy should once again be stressed here. Diagnostic measures for thrombophilia should then be performed if there is already a particular predisposition of the pregnant woman for thrombotic events and if consequences with regard to medical thrombosis prophylaxis would arise from the additional detection of thrombophilia. It is important that diagnostic measures for thrombophilia be performed during the planning phase of a pregnancy, among others, if the woman has a positive family history with regard to thrombotic events. The positive family history in combination with thrombophilia may represent an indication for medical thrombosis prophylaxis in pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Drugs for the Treatment and Prophylaxis of Thrombotic Events in Pregnancy

Low-molecular-weight heparins

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) represent the standard medication for the prophylaxis and treatment of thrombotic events within the scope of pregnancy and the postpartum period 9 , 32 , 36 , 38 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 and have by now largely replaced the unfractionated heparins (UFH) formerly used. In comparison to UFH, LMWHs are characterised in particular by the more favourable adverse effect profile (better tolerability, low risk for heparin-induced thrombocytopaenia [HIT]) with at least comparable efficacy. An overview of the currently available heparins and the pentasaccharide fondaparinux is shown in Table 3 .

Table 3 Overview of parenteral anticoagulants for pregnancy.

| Anticoagulant | Mean molecular weight (Dalton) | Ratio of anti-Xa and anti-IIa effect | Method of production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unfractionated heparin (UFH) | 5 000 – 30 000 | 1 | – |

| Dalteparin | 6 000 | 2.5 | Hydrolysis with HNO 2 |

| Certoparin | 5 200 | 2.2 | Hydrolysis with isoamyl nitrite |

| Nadroparin | 4 500 | 2.5 – 4 | Hydrolysis with HNO 2 and fractionation |

| Enoxaparin | 4 500 | 3.6 | Benzylation and alkaline β-elimination |

| Reviparin | 4 150 | 3.6 – 6.1 | Hydrolysis with HNO 2 |

| Tinzaparin | 6 500 | 1.5 – 2.5 | Enzymatic β-elimination |

| Fondaparinux | 1 728 | Only anti-Xa effect | Artificial chemical synthesis |

For the primary and secondary prophylaxis of VTE, LMWHs are used during pregnancy generally at a dosage adapted to the high-risk prophylaxis. Various LMWHs which are available as a pre-filled syringe for self-application by the patients are available for this. Recently, tinzaparin received German approval for high-risk prophylaxis at a dosage of 4,500 IU/d and is now also available as a pre-filled syringe for VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy; according to the summary of product characteristics, there are data in more than 2,000 cases available on the use of tinzaparin in pregnancy.

LMWHs at a therapeutic dosage are used for the treatment of thrombotic events in pregnancy. In this connection, therapeutic anticoagulation with a once-daily heparin application is possible with tinzaparin, while other LMWHs must be applied twice daily in therapeutic use.

An overview of the standard dosages of LMWHs for the prophylaxis and treatment of pregnancy-associated VTE is presented in Table 4 ; it should be emphasised that in justified cases, there may have to be deviations from these standard dosages.

Table 4 Dosage of low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) and fondaparinux for the prophylaxis and treatment of thrombotic events in pregnancy.

| Substance group | Active substance | Preparation | Dosage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prophylaxis | Therapy | |||

| BW = Body weight | ||||

| Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) | Certoparin | Mono-Embolex ® (Aspen) | 1 × 3000 IU/d s. c. | 2 × daily 8,000 IU s. c. (Independent of BW) |

| Dalteparin | Fragmin ® (Pfizer) | 1 × 5000 IU/d s. c. | 2 × daily 100 IU/kgBW s. c. | |

| 1 × daily 200 IU/kgBW s. c. | ||||

| Enoxaparin | Clexane ® (Sanofi) | 1 × 40 mg/d s. c. | 2 × daily 1 mg/kgBW s. c. | |

| Nadroparin | Fraxiparin ® (Aspen) | 1 × 0.3 ml/d s. c. | 2 × daily 0.1 ml/10 kgBW s. c. | |

| Tinzaparin | Innohep ® (LEO Pharma) | 1 × 4500 IU/d s. c. | 1 × daily 175 IU/kgBW s. c. | |

| Pentasaccharide | Fondaparinux | Arixtra ® (Aspen) | 1 × 2.5 mg/d s. c. | < 50 kgBW: 1 × daily 5 mg s. c. 50 – 100 kgBW: 1 × daily 7.5 mg s. c. > 100 kgBW: 1 × daily 10 mg s. c. |

Fondaparinux

The pentasaccharide fondaparinux represents an alternative to the prophylaxis and treatment of VTEs in pregnancy 62 , 63 , 65 . The preparation is characterised by good tolerability and a low rate of allergic reactions. However, in contrast to LMWH, fondaparinux crosses the placental barrier. This crossing of the placental barrier is indeed generally considered to be nonproblematic; nonetheless, the use of fondaparinux in pregnancy should be limited to those cases in which LMWH cannot be used 32 , 36 , 55 , such as in the case of HIT and intolerance to (various) LMWHs, particularly cutaneous allergic reactions.

Danaparoid

The heparinoid danaparoid principally also represents an alternative for the prophylaxis and treatment of thrombotic events if LMWH cannot be used after previous HIT or allergic reactions to the application of LMWH. Nowadays, danaparoid is still used only very rarely during pregnancy 66 , 67 .

Oral anticoagulants

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA), in particular phenprocoumon and warfarin, cross the placental barrier; when they are used during pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester, embryotoxic effects have been described (so-called “warfarin embryopathy”) 68 . As a result, its use is prohibited, particularly in the phase which is crucial for embryonic development, the first trimester of pregnancy. In rare exceptional cases, particularly in women with a mechanical heart valve replacement, VKA are used after the first trimester for prophylaxis of thrombotic complications.

Experiences with non-vitamin-K-dependent oral anticoagulants (NOAK), the direct oral thrombin inhibitor (DTI) dabigatran etexilate and the oral Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban during pregnancy are limited. These anticoagulants are not formally approved during pregnancy and breastfeeding. However, the few reports available indicate that, if NOAKs are inadvertently used in the first trimester of pregnancy, there are apparently not more frequent maternal complications or damage to the embryo; the use of NOAKs in early pregnancy therefore does not represent a sufficient justification for discontinuation of a pregnancy, according to current circumstances.

If a pregnancy occurs during exposure to VKAs or NOAKs, the oral anticoagulation must be stopped and a rapid switch made to a parenteral anticoagulant, generally an LMWH 9 .

It is important to note that the VKA phenprocoumon as well as NOAKs should not be used during breastfeeding. If oral anticoagulation is necessary during breastfeeding, the VKA coumadin, which does not pass into breast milk, can be used for this purpose. Alternatively, parenteral anticoagulation can of course be performed with an LMWH or fondaparinux during breastfeeding 9 .

Laboratory Testing on Antithrombotic Medication in Pregnancy

Concomitant laboratory monitoring during medical prophylaxis or treatment of VTE during pregnancy is the subject of controversial discussion. From the authorʼs viewpoint, periodic laboratory checks are advisable for various reasons 9 .

A dreaded adverse effect of the application of heparins is HIT which is a serious thrombotic condition. In comparison to the use of UFH, the risk of HIT in the case of LMWH is extremely low; in addition, this complication occurs predominantly in at-risk surgical patient collectives (e.g. in vascular surgery) and is quite rare in the conservative specialty, particularly in pregnancy. Consequently, routine blood count testing during heparinisation in pregnancy and the postpartum period for early detection of HIT, where applicable, is no longer recommended nowadays. If thrombocytopaenia occurs in pregnancy during heparinisation, a causal HIT should be considered as a differential diagnosis; however, gestational thrombocytopaenia and immunothrombocytopaenia represent by far the most common causes of thrombocytopaenia during pregnancy.

Since the anticoagulatory heparin effect is not constant throughout pregnancy due to the physiological changes of haemostasis, an anticoagulation dose increase may be necessary. The effect of the parenteral anticoagulants used (LMWH, fondaparinux, danaparoid) can be observed by determining the anti-factor-Xa activity, whereby the method should be calibrated to the anticoagulant used. To document the crucial peak levels of the anticoagulants used for assessing the dosage, the blood samples should be taken, where applicable, about 3 – 4 hours after the last injection of the anticoagulant. Along with the anti-factor-Xa activity, other criteria for dose adjustment of the parenteral anticoagulants during pregnancy can be used: Unusually high activation markers (such as D-dimers) may indicate insufficient coagulation inhibition and require an increase in the dosage.

Finally, it should be noted that, for the parenteral anticoagulants used, in particular LMWH, there is indeed much experience on use during pregnancy and breastfeeding, but these are not formally approved for use in pregnancy. Thus they should be used following a careful benefit/risk consideration and suitable monitoring should be performed to detect any potential toxicity. There may be hepatotoxic adverse effects with an increase in liver values during parenteral anticoagulation and this may necessitate a switch in the anticoagulation. Since renal failure may result in a restriction regarding the use of parenteral anticoagulants or may necessitate a dose reduction, it is additionally recommended to check renal function – particularly in the case of therapeutic anticoagulation or patients at risk. The potential for accumulation of long-chain LMWHs, such as tinzaparin and dalteparin, is the lowest if there is renal dysfunction because of an alternative elimination pathway via the reticuloendothelial system (RES) 62 .

Medical Thrombosis Prophylaxis in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

As is also the case outside of pregnancy, the avoidance of immobility is the crucial basic measure for preventing pregnancy-associated VTEs. After delivery, early mobilisation should be ensured and this can also be supported through physical therapy, where applicable 9 . With regard to an indication for medical thrombosis prophylaxis, a distinction should be made between situational transient thrombosis prophylaxis, primary and secondary prophylaxis 9 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 .

Transient/situational prophylaxis

Thrombosis prophylaxis during pregnancy for a limited period of time is administered due to transient, situational risk factors or risk situations which are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis in the pregnant woman. These include surgical interventions, immobilisation, serious infections and long-distance (air) travel with travel lasting more than 3 – 4 hours. In such situations, there is already an increased risk of thrombosis, which is increased even further during pregnancy. Fundamentally, in all cases in which transient medical thrombosis prophylaxis is also administered outside of pregnancy, corresponding prophylaxis should be conducted during pregnancy; this can be implemented according to the corresponding guideline recommendations 38 .

Primary prophylaxis

To be able to adequately determine an indication for medical thrombosis prophylaxis in pregnancy, an individual consideration of the risk of thrombosis of the pregnant woman is necessary, taking into account all known predispositional and expositional risk factors. Here, the presence of hereditary thrombophilic risk factors is also of particular significance, especially factor V Leiden mutation (factor V G1691A), prothrombin mutation (factor II G20210A) as well as protein C, protein S and antithrombin deficiency.

Determining the absolute risk of thrombosis in pregnancy given the presence of genetically determined thrombophilia is not without problems, since the presence of other predispositional risk factors must be incorporated into the determination of overall risk. At the same time, various thrombophilic risk factors may be present which can then increase the thrombotic risk – possibly beyond multiplicatively. Thus, for example, the heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation in the case of a lack of predisposition otherwise is associated with a risk of thrombosis of approx. 0.3% in pregnancy 10 , 23 ; therefore this mutation alone is not an indication for primary medical prophylaxis during pregnancy. By contrast, the homozygous factor V Leiden mutation with a risk of thrombosis of approx. 1.5% and the combination of heterozygous factor V Leiden and heterozygous prothrombin mutation with a risk of approx. 5% in pregnancy 10 , 23 generally justifies medical prophylaxis during pregnancy, even if no other predisposing risk factors are present. The fact that the absolute risks indicated can still greatly increase if other predispositional risk factors for VTE are present must be taken into account. For example, the positive family history for VTE leads to an increase in risk which is about 2 – 4 times as high, the obesity doubles to triples the risk of thrombosis, and in the case of older age during pregnancy, the risk of thrombosis also increases.

While medical primary prophylaxis in pregnancy and the postpartum period per se is generally not necessary in the case of a minor predisposition for thrombotic events (such as a BMI of 25 – 30 kg/m 2 ), primary medical thrombosis prophylaxis is recommended during the postpartum period in the case of a moderate predisposition – generally in the case of a combination of mild thrombophilia with another predispositional risk factor. If additional risk factors which promote the risk of thrombosis occur during pregnancy, medical thrombosis prophylaxis is already initiated in pregnancy, where applicable. If there is a severe predisposition for thrombotic events, such as severe thrombophilia, medical thrombosis prophylaxis is given throughout the entire pregnancy. As a general principle, medical thrombosis prophylaxis started during pregnancy is generally continued for about six weeks following delivery due to the risk of thrombosis which peaks during the postpartum period. If epidural anaesthesia (EA) or a Caesarean section is performed during delivery, there should be a period of at least 12 hours between the last heparin administration and the implementation of the intervention or delivery 9 , 32 .

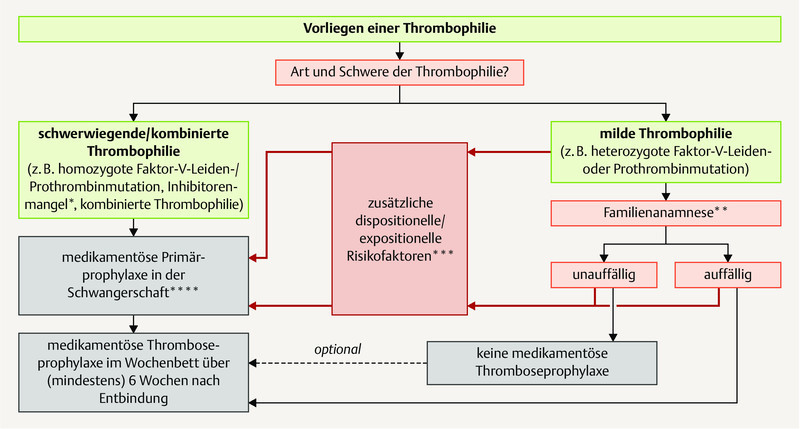

A general algorithm ( Fig. 2 ) as well as an algorithm if thrombophilia is present ( Fig. 3 ) for primary medical prophylaxis during pregnancy are represented graphically.

Fig. 2.

Primary prophylaxis of thrombotic events during pregnancy with the presence of predispositional risk factors.

Fig. 3.

Primary prophylaxis of thrombotic events during pregnancy with the presence of thrombophilia. * Depending on the nature and severity of the inhibitor deficiency. ** Deep venous thrombosis, particularly in first-degree relatives. *** Depending on the nature and severity of the risk factor; where applicable, repeated examination in pregnancy is necessary. **** In the case of medical thrombosis prophylaxis conducted during pregnancy, this is also generally continued over 6 weeks post partum.

Secondary prophylaxis

In patients with a history of VTE which occurred prior to pregnancy, there is an increased risk of recurrence during pregnancy which may be 10 – 20%, depending on the existing constellation. Therefore these women generally receive medical thrombosis prophylaxis, particularly after events occurring spontaneously or events with a hormonal trigger (on hormonal contraception, hormone [replacement] therapy [HRT] or in an earlier pregnancy). In the case of patients with a significant transient risk factor, such as after severe trauma or a major surgical procedure, waiting may be justified. Since the risk of thrombosis and also the risk of recurrence after a prior event are elevated from the start of the pregnancy, medical thrombosis prophylaxis is begun promptly when pregnancy occurs and generally continued for 6 weeks post partum; if situational risk factors last more than 6 weeks after delivery, the medical thrombosis prophylaxis may need to be prolonged further 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 . In the case of therapeutic heparinisation, there should be at least 24 hours between the last heparin administration and delivery – particularly if epidural anaesthesia is administered 32 . Failure to observe this interval can significantly increase the risk of bleeding complications, particularly within the scope of the epidural anaesthesia. If there is a high risk of thrombosis, UFH can be given intravenously up to 4 – 6 hours before the intervention; if the corresponding interval cannot be observed, performing epidural anaesthesia should be avoided, if applicable 9 , 69 .

An algorithm for medical secondary prophylaxis in pregnancy following prior thrombotic events is shown in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

Secondary prophylaxis following a prior VTE in pregnancy. * In particular hormonally triggered events (on hormonal contraception, hormone (replacement) therapy [HRT] or in earlier pregnancy). ** Where applicable, repeated review of acquired/expositional risk factors during pregnancy necessary.

Anticoagulation in the Case of Thrombotic Events in Pregnancy

If a deep venous thrombosis occurs during pregnancy with or without a concomitant pulmonary embolism, therapeutic anticoagulation is necessary; this is generally conducted using a LMWH at a therapeutic dosage and in exceptional cases using fondaparinux at a therapeutic dosage 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 . A dose reduction does not take place for the duration of the anticoagulation if no special circumstances – such as increased bleeding tendency – are present under anticoagulation 9 .

As a general principle, the anticoagulation is administered for at least 3 months and is always continued for a period of 6 weeks post partum since the thrombotic risk “peaks” during the postpartum period. In the postpartum period, the anticoagulation can be administered either parenterally or a switch to an oral form can be made. However, it should be borne in mind that all currently available NOAKs are contraindicated during breastfeeding and that the VKA phenprocoumon, which is predominantly used in Germany, passes into breast milk and can induce or worsen a vitamin K deficiency in the newborn. Therefore only warfarin – which does not pass into breast milk and which is therefore also approved for use during breastfeeding – is currently considered for oral anticoagulation during breastfeeding. The switch to warfarin must be started such that it overlaps the parenteral anticoagulation, where applicable; the latter can be stopped if the INR value on warfarin is in the desired target range after loading (generally 2.0 – 3.0). If permanent anticoagulation is required in women with repeat VTEs, this can be switched to an oral form before the end of breastfeeding or in the case of women who are not breastfeeding, whereby alternatively a NOAK (the Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban as well as the direct oral thrombin inhibitor [DTI] dabigatran etexilate are currently available) or a VKA, generally phenprocoumon, can then be used 9 .

An algorithm for anticoagulation in pregnancy-associated thrombotic events is shown in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

Anticoagulation in the appearance of thrombotic or thromboembolic events during pregnancy.

Following pregnancy-associated thrombotic events, no long-term or permanent anticoagulation is generally necessary, as in the case of other thrombotic events in a defined risk situation. However, there may be deviations from this if there is a marked predisposition for thrombotic events or a significantly increased future risk of recurrence is assumed; this may be the case, for example, if there is severe thrombophilia or in the case of recurrent thrombotic events. To clarify this question, it is recommended in corresponding cases that affected patients present to an outpatient coagulation unit.

Even if there is no permanent anticoagulation following pregnancy-associated VTEs, the following consequences result 9 :

Taking hormonal contraceptives should preferably be avoided following pregnancy-associated and other hormonally triggered events; where applicable, a pure gestagen preparation (“minipill”) can be used for contraception. However, in doing so, formal legal reasons should be observed since according to the summary of product characteristics, “minipills” are also contraindicated following VTEs.

In risk situations following pregnancy-associated events, medical thrombosis prophylaxis, generally with a LMWH, should be given, where applicable.

According to the guideline, medical thrombosis prophylaxis, generally with LMWH, is indicated in a subsequent pregnancy from the start of the pregnancy until (at least) 6 weeks post partum, following a previous pregnancy-associated event in a previous pregnancy.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt Dr. Sucker received payments from pharmaceutical companies that produce parenteral anticoagulants used in pregnancy (Aspen, LeoPharma, Sanofi) and of companies that offer devices and reagents for laboratory analyses on the field of haemostasis (Werfen, Stago). Payments were received for lectures and participation in advisory boards./Dr. Sucker hat von pharmazeutischen Unternehmen, die parenterale Antikoagulanzien zur Anwendung während der Schwangerschaft herstellen (Aspen, LeoPharma, Sanofi), sowie von Unternehmen, die Geräte und Reagenzien für Laboranalysen im Bereich der Hämostase anbieten (Werfen, Stago), Zahlungen für Vorträge und die Mitgliedschaft in Beiräten erhalten.

References/Literatur

- 1.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A. Global causes of maternal deaths: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e329–e338. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Stefano V, Martinelli I, Rossi E. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and puerperium without antithrombotic prophylaxis. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:386–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gherman R B, Goodwin T M, Leung B. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and timing of objectively diagnosed venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:730–734. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heit J A, Kobbervig C E, James A H. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:697–706. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsen A F, Skjeldestad F E, Sandset P M. Incidence and risk patterns of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and puerperium – a register-based case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:2330–2.33E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindqvist P, Dahlbäck B, Marsal K. Thrombotic risk during pregnancy: a population study. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:595–599. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma S, Monga D. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the post-partum period: Incidence and risk factors in a large Victorian health service. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson E L, Lawrenson R A, Nighingale A L. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and the puerperium: incidence and additional risk factors from a London perinatal database. BJOG. 2001;108:56–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sucker C. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2017. Klinische Hämostaseologie in der Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zotz R B, Sucker C, Gerhardt A. Thrombophile Hämostasestörung in der Schwangerschaft. Haemostaseologie. 2008;28:455–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kourlaba G, Relakis J, Kontodimas S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology and burden of venous thromboembolism among pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parunov L A, Soshitova N P, Ovanesov M V. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism (VTE) associated with pregnancy. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2015;105:167–184. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bremme K A. Haemostatic changes in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2003;16:153–168. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6926(03)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cadroy Y, Grandjean H, Pichon J. Evaluation of six markers of haemostatic system in normal pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by hypertension or pre-eclampsia. Br J Ostet Gynaecol. 1993;100:416–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichinger S. D-dimer testing in pregnancy. Semin Vasc Med. 2005;5:375–378. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-922483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoke M, Kyrle P A, Philipp K. Prospective evaluation of coagulation activation in pregnant women receiving low-molecular weight heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:935–940. doi: 10.1160/TH03-11-0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerneca F, Ricci G, Simeone R. Coagulation and fibrinolysis changes in normal pregnancy. Increased level of procoagulants and reduced levels of inhibitors during pregnancy induce a hypercoagulable state, combined with a reactive fibrinolysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;73:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(97)02734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costantine M M. Physiologic and pharmacokinetic changes in pregnancy. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:65. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danilenko-Dixon D R, Heit J A, Silverstein M D. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism during pregnancy or post partum: a population-based, case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:104–110. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.107919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Recurrence of a clot in This Pregnancy Study Group . Brill-Edwards P, Ginsberg J S, Gent M. Safety of withholding heparin in pregnant women with a history of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1439–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pabinger I, Grafenhofer H, Kyrle P A. Temporary increase in the risk for recurrence during pregnancy in women with a history of venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2002;100:1060–1062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pabinger I, Grafenhofer H, Kaider A. Risk of pregnancy-associated recurrent venous thromboembolism in women with a history of venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:949–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerhardt A, Scharf R E, Beckmann R E. Prothrombin and factor V mutations in women with a history of thrombosis during pregnancy and the puerperium. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:374–380. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerhardt A, Scharf R E, Zotz R B. Effect of hemostatic risk factors on the individual probability of thrombosis during pregnancy and the puerperium. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogunyemi D, Cuellar F, Ku W. Association between inherited thrombophilias, antiphospholipid antibodies, and lipoprotein A levels and venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2003;20:17–24. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pomp E R, Lenselink A M, Rosendaal F R. Pregnancy, the postpartum period and prothrombotic defects: risk of venous thrombosis in the MEGA study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson L, Wu O, Langhorne P. Thrombophilia in pregnancy: a systematic review. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:171–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosendaal F R, Koster T, Vandenbroucke J P. High risk of thrombosis in patients homozygous for factor V Leiden (activated protein C resistance) Blood. 1995;85:1504–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosendaal F R. Risk factors for venous thrombosis: Prevalence, risk, and interaction. Sem Hematol. 1997;34:171–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seligsohn U, Lubetsky A. Genetic susceptibility to venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1222–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyakis S, Lockshin M D, Atsumi T. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Green-Top Guideline No. 37a, 2015Online:https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37a.pdflast access: 01.06.2019

- 33.Larsen T B, Sørensen H T, Gislum M. Maternal smoking, obesity, and risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium: a population-based nested case-control study. Thromb Res. 2007;120:505–509. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liston F, Davies G A. Thromboembolism in the obese pregnant woman. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35:330–334. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butwick A J, Bentley J, Leonard S A. Prepregnancy maternal body mass index and venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2019;126:581–588. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates S M, Greer I A, Middeldorp S. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141 (2 Suppl.):e691S–e736S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics . James A. Practice bulletin no. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:718–729. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) S3-Leitlinie Prophylaxe der venösen Thromboembolie (VTE), 2. komplett überarbeitete Auflage, Stand 15.10.2015Online:https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/003-001.htmllast access: 01.07.2019

- 39.Rova K, Passmark H, Lindqvist P G. Venous thromboembolism in relation to in vitro fertilization: an approach to determining the incidence and increase in risk in successful cycles. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henriksson P, Westerlund E, Wallén H. Incidence of pulmonary and venous thromboembolism in pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2013;346:e8632. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.RIETE Investigators . Grandone E, Di Micco P P, Villani M. Venous Thromboembolism in Women Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Data from the RIETE Registry. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118:1962–1968. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan W S, Dixon M E. The “ART” of thromboembolism: a review of assisted reproductive technology and thromboembolic complications. Thromb Res. 2008;121:713–726. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen A T, Erichsen R, Horváth-Puhó E. Inflammatory bowel disease and venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the postpartum period. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:702–708. doi: 10.1111/jth.13638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fornaro R, Caristo G, Stratta E. Thrombotic complications in inflammatory bowel diseases. G Chir. 2019;40:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee J J, Pope J E. A meta-analysis of the risk of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. doi:10.1186/s13075-014-0435-y. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:435. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0435-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Million Women Study collaborators . Sweetland S, Green J, Liu B. Duration and magnitude of the postoperative risk of venous thromboembolism in middle aged women: prospective cohort study. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4583. BMJ. 2009;339:b4583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bates S M. Management of pregnant women with thrombophilia or a history of venous thromboembolism. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007;2007:143–150. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bates S M. Pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism: prevention and treatment. Semin Hematol. 2011;48:271–284. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James A H, Jamison M G, Brancazio L R. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the postpartum period: incidence, risk factors, and mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.James A H. Pregnancy-associated thrombosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:277–285. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James A H. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:326–331. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.184127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chauleur C, Gris J C, Laporte S. Use of the Delphi method to facilitate antithrombotics prescription during pregnancy. Thromb Res. 2010;126:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Thromboembolic disease in pregnancy and the puerperium: acute management. Green-top Guideline No. 37b, April 2015Online:https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37b.pdflast access: 01.06.2019

- 54.Working Group in Womenʼs Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis . Linnemann B, Scholz U, Rott H. Treatment of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism – position paper from the Working Group in Womenʼs Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH) Vasa. 2016;45:103–118. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kent NE; VTE in Pregnancy Guideline Working Group ; Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada . Chan W S, Rey E. Venous thromboembolism and antithrombotic therapy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:527–553. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DʼIppolito S, Ortiz A S, Veglia M. Low molecular weight heparin in obstetric care: a review of the literature. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:602–613. doi: 10.1177/1933719111404612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lepercq J, Conrad J, Borel-Derlon A. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy: a retrospective study of enoxaparin safety in 624 pregnancies. BJOG. 2001;108:1134–1140. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2003.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanson B J, Lensing A W, Prins M H. Safety of low-molecular weight heparin in pregnancy: a systematic review. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:668–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shapiro N L, Kominiarek M A, Nutescu E A. Dosing and monitoring of low-molecular-weight heparin in high-risk pregnancy: single-center experience. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:678–685. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.7.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansen K B, Balchen T. Tinzaparin and other low-molecular-weight heparins: what is the evidence for differential dependence on renal clearance? doi:10.1186/2162-3619-2-21. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2:21. doi: 10.1186/2162-3619-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le Templier G, Rodger M A. Heparin-induced osteoporosis and pregnancy. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14:403–407. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283061191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ciurzyński M, Jankowski K, Pietrzak B. Use of fondaparinux in a pregnant woman with pulmonary embolism and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:56–59. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dempfle C E. Minor transplacental passage of fondaparinux in vivo. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1914–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200404293501825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gerhardt A, Zotz R B, Stockschlaeder M. Fondaparinux is an effective alternative anticoagulant in pregnant women with high risk of venous thromboembolism and intolerance to low-molecular-weight heparins and heparinoids. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:496–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Knol H M, Schultinge L, Erwich J J. Fondaparinux as an alternative anticoagulant therapy during pregnancy. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1876–1879. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindhoff-Last E, Kreutzenbeck H J, Magnani H N. Treatment of 51 pregnancies with danaparoid because of heparin intolerance. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:63–69. doi: 10.1160/TH04-06-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magnani H N. An analysis of clinical outcomes of 91 pregnancies in 83 women treated with danaparoid (Orgaran) Thromb Res. 2010;125:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holzgreve W, Carey J C, Hall B D. Warfarin-induced fetal abnormalities. Lancet. 1976;2(7991):914–915. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) S2-Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie der Venenthrombose und der LungenembolieAktueller Stand:10October2015. Online:https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/065-002l_S2k_VTE_2016-01.pdflast access:01July2019