Abstract

Many protein architectures exhibit evidence of internal rotational symmetry postulated to be the result of gene duplication/fusion events involving a primordial polypeptide motif. A common feature of such structures is a domain‐swapped arrangement at the interface of the N‐ and C‐termini motifs and postulated to provide cooperative interactions that promote folding and stability. De novo designed symmetric protein architectures have demonstrated an ability to accommodate circular permutation of the N‐ and C‐termini in the overall architecture; however, the folding requirement of the primordial motif is poorly understood, and tolerance to circular permutation is essentially unknown. The β‐trefoil protein fold is a threefold‐symmetric architecture where the repeating ~42‐mer “trefoil‐fold” motif assembles via a domain‐swapped arrangement. The trefoil‐fold structure in isolation exposes considerable hydrophobic area that is otherwise buried in the intact β‐trefoil trimeric assembly. The trefoil‐fold sequence is not predicted to adopt the trefoil‐fold architecture in ab initio folding studies; rather, the predicted fold is closely related to a compact “blade” motif from the β‐propeller architecture. Expression of a trefoil‐fold sequence and circular permutants shows that only the wild‐type N‐terminal motif definition yields an intact β‐trefoil trimeric assembly, while permutants yield monomers. The results elucidate the folding requirements of the primordial trefoil‐fold motif, and also suggest that this motif may sample a compact conformation that limits hydrophobic residue exposure, contains key trefoil‐fold structural features, but is more structurally homologous to a β‐propeller blade motif.

Keywords: domain swapping, folding pathway, protein evolution, protein symmetry

1. INTRODUCTION

Several common protein architectures exhibit detectable internal rotational symmetry of a comparatively simple repeating structural motif. The triosphosphate isomerase (TIM)‐barrel (the most common protein architecture) exhibits eightfold rotational symmetry of a β‐strand/turn/α‐helix/turn motif.1, 2 The β‐propeller architecture comprises a diverse family of protein structures exhibiting variable (fourfold to eightfold) rotational symmetry of a motif comprising four antiparallel β‐strands.3, 4, 5 The β‐trefoil, another common protein architecture with diverse members, has threefold rotational symmetry of a motif comprising four antiparallel β‐strands.6, 7 Gene duplication/fusion/truncation events have long been viewed as the most parsimonious evolutionary processes resulting in the emergence of symmetric architectures built up from simple repeating structural motifs.8, 9, 10 Recent de novo design studies have successfully demonstrated cooperatively folded and stable symmetric protein architectures having exact primary structure symmetry, providing support for the gene duplication/fusion evolutionary hypothesis.2, 5, 11, 12, 13 In the case of the β‐trefoil, such “deconstruction” has identified a monomer motif that correctly oligomerizes into the intact threefold‐symmetric architecture.12, 14

The definition of the fundamental repeating motif in symmetric protein architectures can be subjective and is based either upon the native N‐terminus as the start (e.g., β‐trefoil, TIM‐barrel) or by defining the most compact arrangement of secondary structure elements (e.g., β‐propeller). In both cases, a common architectural feature is an apparent domain‐swapped interface between the N‐ (i.e., first) and C‐terminus (i.e., last) motifs (sometimes referred to as a “Velcro strap” arrangement3, 5, 15, 16). Domain swapping is commonly observed in protein oligomerization17, 18, 19 and is postulated to promote cooperative interactions between monomers, favoring oligomeric assembly.11, 16

Protein architectures with adjacent N‐ and C‐termini (including symmetric architectures) lend themselves to circular permutation and are commonly observed in the structural database.20 Such circular permutation alters the structural details of the domain‐swapped interface. Circularly permuted forms of designed symmetric proteins that are able to fold have been described.21, 22 However, circular permutation of symmetric proteins affects only the N‐ and C‐termini motifs, and not internal definitions of such motifs; thus, it is unclear whether the fundamental repeating motif itself can tolerate circular permutation and remain foldable. In the duplication/fusion evolutionary pathway, the isolated repeating motif represents the key primordial folding nucleus (FN) or hereditary element of foldability; however, almost nothing is known regarding the folding properties of such isolated motifs.

De novo design studies of the threefold‐symmetric β‐trefoil architecture have successfully identified a 42‐mer polypeptide (“Monofoil”) comprising the repeating “trefoil‐fold” motif that is able to oligomerize as a trimer and generate the intact β‐trefoil12, 14 (Figure 1). Only the trimer assembly is observed upon expression of the Monofoil peptide, and no monomer is detected. The definition for the trefoil‐fold motif starts from the N‐terminus; however, with this definition an extended conformation results that produces a domain‐swapped interaction with the subsequent motif. Thus, the individual trefoil‐fold in structural isolation exposes 707 Å2 of hydrophobic surface area that is subsequently buried upon oligomeric trimer assembly. Alternative circularly permuted definitions of the trefoil‐fold motif are possible that are much more compact and expose significantly less hydrophobic surface area. However, it is not known if such trefoil‐fold definitions are capable of oligomerization (or are even soluble). The folding and oligomerization of domain‐swapped motifs in symmetric protein architecture are key, yet poorly understood, processes in their evolution and de novo design.23

Figure 1.

The β‐trefoil and Monofoil trefoil‐fold structural features. (a) Ribbon diagram of the Symfoil‐4P de novo designed symmetric β‐trefoil protein (research collaboratory for structural bioinformatics (RCSB) accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=304D). The view is down the threefold axis of rotational symmetry (indicated by triangle), and the repeating motif is termed a “trefoil‐fold”. (b) A similar representation for the homotrimer assembly of the Monofoil trefoil‐fold polypeptide (RCSB accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=3OL0). The individual Monofoil polypeptides are indicated by different colors. (c) The Monofoil trimer as in panel b, but with a view normal to the axis of symmetry. (d) An isolated Monofoil polypeptide “outside face” (i.e., a side view as in panel c). (e) A space‐filling representation of d, and colored to indicate side chain properties (gray is hydrophobic, red is acidic, blue is basic, orange is polar). (f) A view of the Monofoil polypeptide “inside face” (i.e., panel d from the opposite direction). (g) Space‐filling representation of panel f (note the extensive hydrophobic character of the buried inside face)

To better understand such processes, an experimental and computational study of the biophysical properties and ab initio predicted structure of the Monofoil trefoil‐fold, and circular permutants thereof, was performed. Ab initio studies suggest that the predicted structural features of an isolated trefoil‐fold sequence are more homologous to a compact “blade” motif from the β‐propeller architecture than the β‐trefoil. Studies of expressed circular permutants indicate that they no longer oligomerize. Thus, while the intact β‐trefoil is tolerant of circular permutation, the fundamental trefoil‐fold is not. Together, the computational and experimental data suggest that prior to oligomerization the Monofoil motif may sample a compact conformation that limits hydrophobic residue exposure. This compact conformation contains the key structural features present within the trefoil‐fold, although it is more structurally homologous to a β‐propeller blade motif.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The expression yields of soluble purified protein varied by the particular construct. The Monofoil polypeptide expressed with excellent yield of approximately 10 mg purified protein per liter of culture (similar to a previously reported form that lacked the 10 amino acid fibroblast growth factor‐1 (FGF‐1) leader sequence12, 14). The P1 polypeptide was purified with a low yield of <0.2 mg per liter of culture; the P2 polypeptide did not yield any purified protein despite repeated efforts; the P3 polypeptide also expressed with an excellent yield of approximately 5 mg purified protein per liter.

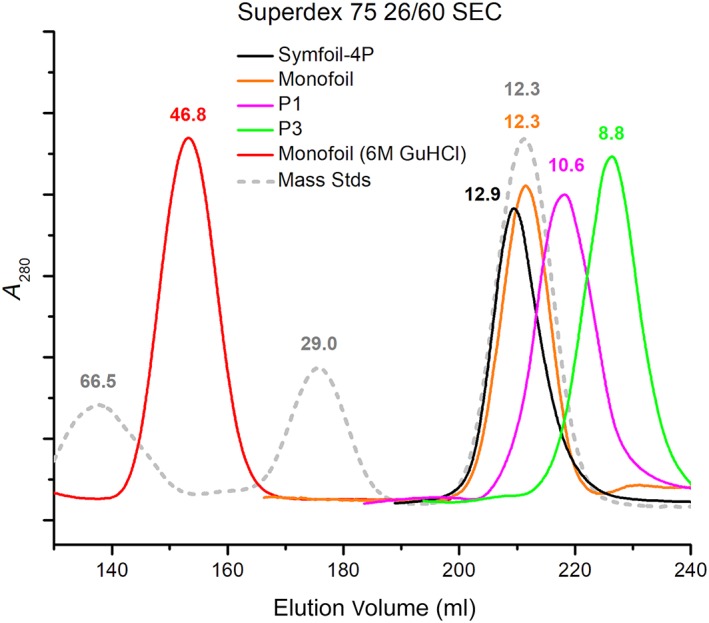

2.2. Analytical size‐exclusion chromatography

The Symfoil‐4P protein (142 amino acids; 15.8 kDa calculated mass) folds into a threefold‐symmetric β‐trefoil architecture with an unstructured His‐tag and FGF‐1 leader sequence (RCSB accession 3O4D).12, 14 On Superdex 75 size‐exclusion chromatography (SEC) under native buffer conditions Symfoil‐4P elutes with an apparent mass of 12.9 kDa (Figure 2). The Monofoil polypeptide comprises 58 amino acids (6 amino acid His tag, 10 amino acid FGF‐1 leader, and a single instance of a 42‐mer trefoil‐fold; 6.4 kDa calculated mass) and resolves on Superdex 75 SEC with an apparent mass of 12.3 kDa similar to the Symfoil‐4P single domain β‐trefoil protein. A version of Monofoil that has a 6xHis tag but lacks the 10 amino acid FGF‐1 leader sequence has previously been reported that oligomerizes as a trimer (forming an intact β‐trefoil fold) and exhibits a similar mass on SEC elution.12, 14 Monofoil permutants P1 and P3 both exhibit significantly smaller apparent masses (10.6 and 8.8 kDa, respectively) on SEC compared to the Monofoil homotrimer polypeptide. Based upon the calculated masses the P1 and P3 polypeptides are not assembling as a trimer (as observed for Monofoil) and are either dimer or expanded monomer structures. Based upon isothermal equilibrium denaturation (IED) results (below) expanded monomers appears most likely. Under fully denaturing conditions of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) the Monofoil polypeptide migrates with much larger apparent mass of 46.8 kDa consistent with extensive unfolding.

Figure 2.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of Symfoil‐4P, Monofoil and permutant P1 and P3 polypeptides. Analytical concentrations of proteins were loaded onto a Superdex 75 column and eluted with Pi buffer. Mass standards included bovine serum albumin (BSA) (66.5 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29.0 kDa) and cytochrome C (12.3 kDa). Monofoil was also resolved in Pi buffer with 6 M GuHCl denaturant. GuHCl, guanidine hydrochloride

2.3. Isothermal equilibrium denaturation

The Monofoil polypeptide exhibits a characteristic cooperative transition with increased fluorescence quenching with increasing denaturant and with fitted parameters in good agreement with prior published values for Monofoil lacking the unstructured 10 amino acid FGF‐1 leader sequence12 (Figure 3). In contrast, the Monofoil P3 polypeptide exhibits a non‐cooperative unfolding behavior and also exhibits a decrease in fluorescence quenching with increasing denaturant (Figure 3). The P1 polypeptide expressed in very low yields that permitted analytical SEC but not more extensive biophysical studies such as isothermal equilibrium denaturation (IED).

Figure 3.

Isothermal equilibrium denaturation (IED) of Monofoil and permutant P3 polypeptides. Upper panel: the IED data for Monofoil showing cooperative unfolding with indicated thermodynamic parameters. Lower panel: the IED data for permutant P3 showing non‐cooperative unfolding behavior, additionally, unlike Monofoil the permutant P3 polypeptide exhibits increased fluorescence signal with increasing denaturant concentration

2.4. Ab initio structure prediction

The ab initio structure predictions for the FGF‐1, Symfoil‐4P, FGF‐1 FN, and Symfoil‐4T FN control sequences exhibited excellent agreement with crystal structures. A detailed analysis is presented here for interested readers (with relevant figures and tables provided in Supporting Information).

2.4.1. FGF‐1 control

The β‐strand secondary structure classification for the ab initio model closely matches that of the crystal structure for all β‐strands except β1, β4, and β12 (Table S1). The top ab initio folding solution for the FGF‐1 sequence when overlaid onto the FGF‐1 crystal structure (RCSB accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1JQZ) yields a root‐mean‐square deviation (rmsd) of 1.29 Å for a total of 107 Cα positions (including residues 10–48, 51–70, 72–90, 95, 97–119, 121, 127, 132, 134, and 136 in the FGF‐1 numbering scheme) (Figure S2). These positions span the ordered region in the FGF‐1 crystal structure (i.e., residue positions 10–137, or 128 amino acid positions). Thus, the 107 Cα positions represent 84% of the ab initio FGF‐1 structure aligning within 1.29 Å of the X‐ray crystal structure. Omitted residue positions 49–50 are located in turn 4 (T4), position 71 is located in T6, positions 91–94 are located in T8, position 96 is located in β‐strand 9 (β9), residue positions 120, 122–126, and 128–130 are all located in T11 (i.e., the last turn), and residue positions 131, 133, and 135 are located in β12 (i.e., the last β‐strand). Thus, the majority of positions not included in the above set of homologous Cα positions are located within turn regions; in this regard, the greatest structural deviation is observed for turn T11 (which, at 12 amino acids, is the longest turn/loop region in the structure). β1 and β12 are the first and last β‐strands, respectively, in the β‐trefoil architecture, and are less‐well defined in the ab initio structure. In this regard, while the β12 region of the ab initio structure closely overlays the corresponding coordinates of the crystal structure, it is not identified as β‐strand by main chain ϕ‐ψ‐angles. The Cα positional error estimate for the ab initio solution is lower for regions of β‐strand and greater for turn regions and the N‐ and C‐termini, and reflects the observed rmsd in the overlay with the crystal structure (Figure S2). The overall confidence value reported for the FGF‐1 ab initio structure is 0.66.

2.4.2. Symfoil‐4P control

The β‐strand secondary structure classification for the ab initio predicted structure of Symfoil‐4P closely matches that of the crystal structure (RCSB accession 3O4D) for all β‐strands except β1 and β12 (Table S2). The top ab initio folding solution for the Symfoil‐4P sequence when overlaid onto the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure yields a rmsd of 1.36 Å for a total of 71 Cα positions (including residues 11–37, 39–49, 54–77, 86, 98, 110–111, 115–116, and 118–119 in the FGF‐1 numbering scheme) (Figure S3). The principle differences when comparing these two structures is that the C‐terminal β‐strand (β12) is disordered in the ab initio structure; consequently, the T8 β‐hairpin is shifted (i.e., collapses) toward the center of the structure (i.e., toward the location of the missing β12). The β8/β9 hairpin comprises positions 84–110 (i.e., largely omitted from the above set of overlaying Cα atoms due to its positional shift); however, the Cα positions of β8 and β9 (as a subset of 17 positions) overlay with an rmsd of 1.21 Å (indicating that these β‐strands are essentially correctly folded, but are shifted in position as a rigid body). The T11/β12 region comprises positions 123–137, which are absent from the above set of overlaying Cα atoms and adopt an entirely different conformation from the crystal structure. As observed for the FGF‐1 ab initio solution, the Cα positional error estimate for the ab initio solution of Symfoil‐4P is lower for regions of β‐strand and greater for turn regions and the N‐ and C‐termini (Figure S3). The greatest positional uncertainty is associated with the β12 region, and this reflects its unstructured conformation in the ab initio structure. The overall confidence value reported for the Symfoil‐4P ab initio structure is 0.50.

2.4.3. FGF‐1 FN control

ϕ‐Value analysis within FGF‐1 turn regions indicates the FN spans an essentially contiguous region of primary structure from T2‐T8.24 This region omits β1 (i.e., the N‐terminus β‐strand of the first trefoil‐fold), as well as all of the last (i.e., C‐terminal) trefoil‐fold. Due to the sparse sampling nature of the ϕ‐value analysis there is ambiguity regarding the precise termini definitions of the FN; therefore, two variants of the FGF‐1 FN primary structure were evaluated in ab initio structure prediction: (1) residue positions 21–90 (spanning β2‐β8; FGF‐1 FN1) and (2) residue positions 30–100 (spanning β3‐β9; FGF‐1 FN2).

The top ab initio folding solution for the FGF‐1 FN1 sequence when overlaid onto the FGF‐1 crystal structure yields a rmsd of 1.18 Å for a total of 56/70 Cα positions. These positions include 22–34, 39–67, 73–85, and 87 in the FGF‐1 numbering scheme and spans β2 through the N‐terminus of β8 (Figure S4). Turn T6 (residue positions 68–72) is excluded from this set; however, the Cα atoms within an isolated T6 region (defined by positions 65–75) overlays with FGF‐1 T6 with an rsmd of 0.7 Å (comprising a total of 11 Cα positions). Thus, T6 is correctly structured but shifted (i.e., collapsed) approximately 5.7 Å toward the core region. The β‐strand secondary structure classification for the FGF‐1 FN1 ab initio structure is identical to that of the FGF‐1 crystal structure with the exception of minor distortion of the N‐terminus of β2 and the C‐terminus of β8 (Table S3). The greatest positional uncertainty is associated with the C‐terminus (i.e., the C‐terminus of the β8 region), and this reflects the principle structural deviation overlay with the FGF‐1 crystal structure. The overall confidence value for the FGF‐1 FN1 ab initio structure is 0.73.

The top ab initio folding solution for the FGF‐1 FN2 sequence when overlaid onto the FGF‐1 crystal structure yields a rmsd of 1.35 Å for a total of 42 contiguous Cα positions spanning residue positions 45–86 in the FGF‐1 numbering scheme (Figure S5). This region encompasses the N‐terminus region of β4 through T7 and describes an integral unit of a 42‐mer trefoil‐fold, although circularly permuted (Figure 4). The β3 and T3 regions in the ab initio structure (i.e., the N‐terminus for this definition of the FGF‐1 FN) exhibit a major deviation from the corresponding FGF‐1 structure. The β8/T8/β9 hairpin (i.e., the C‐terminus for this definition of the FGF‐1 FN) is also not part of the conserved structural overlay; however, this β‐hairpin is formed in the ab initio structure although it folds over toward the interior and is therefore distorted in comparison to the equivalent β‐hairpin in FGF‐1 (Figure S5). The β‐strand secondary structure classification for the FGF‐1 FN2 ab initio model is identical to that of the FGF‐1 crystal structure for the centrally located β6 and β7 strands. While the remaining β‐strand assignments are generally correct, their definition tends to deviate proportionally with distance from this central β6/β7 region (Table S4). The greatest positional uncertainty is associated with the β3 region and the β8/T8/β9 region, and this reflects the deviation of these regions in the structural overlay with the equivalent regions from the FGF‐1 crystal structure. The overall confidence value reported for the FGF‐1 FN2 ab initio structure is 0.61.

Figure 4.

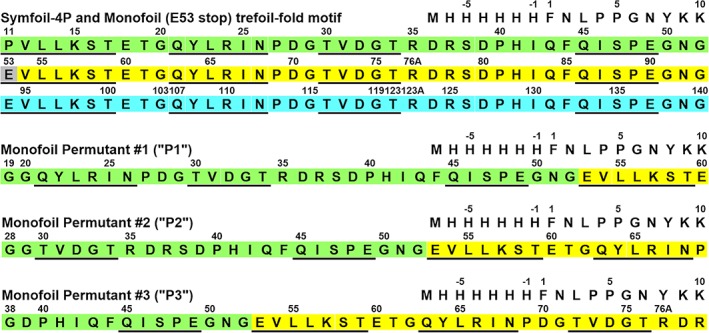

The primary structure of Symfoil‐4P, Monofoil and Monofoil P1, P2, and P3 circular permutants. The three repeating trefoil‐fold motifs in Symfoil‐4P are indicated by color shading (single letter amino acid code is used). Locations of β‐strand secondary structure are indicated with underline. The single Monofoil trefoil‐fold was constructed by introducing a stop codon at position 53 in Symfoil‐4P (indicated by gray shading). Circular permutants P1, P2, and P3 of the Monofoil sequence were constructed at positions within surface turn positions and outside the four β‐strand regions (following a previous convention 17). Their primary structure relationship to Monofoil is indicated by color shading

2.4.4. Symfoil‐4T FN control

ϕ‐Value analysis of Symfoil‐4T (RCSB accession 3O4B) turn regions indicates the FN spans an essentially contiguous region of primary structure from T4‐T10.25 This region omits essentially the first (i.e., N‐terminus) trefoil‐fold, as well as the last half of the C‐terminus trefoil‐fold. Due to the sparse sampling nature of the ϕ‐value analysis there is ambiguity as regards the precise termini definitions of the FN. Two variants of the Symfoil‐4T FN primary structure were therefore evaluated in ab initio structure prediction: (a) residue positions 43–112 (spanning β4‐β10; Symfoil‐4T FN1) and (b) residue positions 53–123 (spanning β5‐β11; Symfoil‐4T FN2).

The top ab initio folding solution for the Symfoil‐4T FN1 sequence when overlaid onto the Symfoil‐4T crystal structure (RCSB accession 3O4B) yields a rmsd of 1.29 Å for a total of 49 Cα positions spanning residues 43–46, 52–57, 62–78, 80–89, and 96–109 (in the FGF‐1 numbering scheme (Figure S6). Residue positions not included in this set primarily comprise locations within turn regions, that is, 47–51 (T4), 58–61 (T5), 79 (T7), 90–95 (T8), as well as residues 110–112 at the C‐terminus of β10. The β‐strand secondary structure classification for the Symfoil‐4T ab initio model matches closely the Symfoil‐4T crystal structure with the exception of the amino‐terminus β4 strand (Table S5). This region is not identified as β‐strand secondary structure (although residue positions 43–46 in this region are included in the Cα overlay). The greatest positional uncertainty is associated with the β4/T4 N‐terminus region and the β8/T8/β9 region (Figure S6). This reflects the lack of β‐strand definition in the N‐terminus of the ab initio structure, and the general omission of turn regions in the set of Cα overlay atoms. The overall confidence value reported for the Symfoil‐4T FN1 ab initio structure is 0.64.

The top ab initio folding solution for the Symfoil‐4T FN2 sequence when overlaid onto the Symfoil‐4T crystal structure (RCSB accession 3O4B) yields a rmsd of 1.20 Å for a total of 48 Cα positions spanning residues 53–67, 73–90, 93–109 (in the FGF‐1 numbering scheme (Figure S7). Residue positions not included in this set primarily comprise locations within turn regions, that is, 68–72 (T6), 91–92 (T8), and 110–123 (β10/T10/β11). However, the β10/T10/β11 region (comprising residues 109–119) of the ab initio structure overlay the same region in the 3O4B crystal structure with an rmsd of 0.59 Å (involving 11 Cα positions). This β‐hairpin structure is therefore correct; however, it is shifted in position (i.e., collapsed) toward the core of the structure. The β‐strand secondary structure classification for the Symfoil‐4T FN2 ab initio model is identical to the Symfoil‐4T crystal structure with the exception of the amino‐terminus β5 and carboxy‐terminus β11 strands which are shorter in length (Table S6). The positional uncertainty is minimal throughout the entire Symfoil‐4T FN2 sequence (Figure S7). The overall confidence value reported for the Symfoil‐4T FN2 ab initio structure is 0.83.

2.5. Monofoil

The top ab initio folding solution for the Monofoil trefoil‐fold sequence includes four β‐strands that are in good agreement with the β‐strand definitions from the same region in the Symfoil‐4P structure (Table S7). The individual β‐strand and turn secondary structure elements in the ab initio structure exhibit structural similarity with the equivalent elements in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure, with the exception of the T3 region. However, despite the generally good agreement for the predicted individual secondary structure elements, the overall ab initio structure does not arrange the β‐strands in a characteristic trefoil‐fold conformation, instead forming a compact four‐stranded antiparallel β‐sheet conformation (Figure 5). Thus, a global structural overlay of the Monofoil ab initio structure onto the equivalent region of the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure does not yield any meaningful solution; however, an overlay of subdomains does identify two general regions having significant structural similarity with the Symfoil‐4P (i.e., trefoil‐fold) structure. The first region involves residues 14–24 and 31–33 (comprising 14 Cα positions) that overlay with an rmsd of 1.38 Å (Figure 6). Positions 14–24 include the C‐terminus of β1, T1 and the N‐terminus of β2. Residue positions 31–33 include the central region of β3, and this region is correctly juxtaposed with β2 to form two H‐bonds in both the ab initio structure and the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure. The second region of structural similarity involves residues 23–33 (comprising 11 Cα positions) that overlay with an rmsd of 0.50 Å. These positions include the C‐terminus of β2, T2, and the N‐terminus of β3 (Figure 6). The positional uncertainty is minimal throughout the entire Monofoil sequence until the C‐terminus region (Figure 5). The overall confidence value reported for the Monofoil ab initio structure is 0.45.

Figure 5.

Monofoil, P1, P2, and P3 crystal structure, ab initio predicted structure, and ab initio Cα error estimates. Left column: Ribbon diagram (side view) of the Cα coordinates of residue positions 10–52 (Monofoil), 19–60 (P1), 28–69 (P2), and 38–78 (P3) from the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure (research collaboratory for structural bioinformatics (RCSB) accession 3O4D) (see Figure 4). Regions of β‐strand secondary structure are indicated by an arrow. Locations of the N‐ and C‐termini, β‐strands, and turns are also indicated. Central column: a similar ribbon diagram for the predicted ab initio structure for each polypeptide. Right column: Cα error estimate for the respective ab initio structure. The location of the individual β‐strands is indicated. Due to the primary structure symmetry β5 = β1, β6 = β2, and β7 = β3 in the circular permutations (see Figure 4)

Figure 6.

Regions of structural similarity between the ab initio and crystal structures of Monofoil and permutant sequences. The diagram shows the general secondary structure arrangement for the Monofoil and permutant sequences based upon the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure (left column) and the ab initio structure (right column). β‐Strands are indicated by arrows and interstrand H‐bonds by dashed lines. Due to the exact primary structure symmetry turns T1 and T5 are equivalent, turns T1 and T6 are equivalent, and so on. The shaded regions indicate subdomains that overlay with rmsd <1.5 Å for the set of Cα positions (see Section 2)

A structural similarity search of the ab initio Monofoil structure identifies a potential match within the human clathrin terminal domain protein (RCSB accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC). Human clathrin terminal domain is a seven‐bladed β‐propeller fold. Each repeating “blade” motif comprises four antiparallel β‐strands arranged in pseudo‐sevenfold rotational symmetry around a central axis. The homology match between the predicted ab initio Monofoil polypeptide and clathrin terminal domain crystal structure involves an integral blade motif. Individual overlays with the seven different blades in http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC identifies a best fit with blade #5 (residue positions 198–254 of 1 UTC), yielding an rmsd of 1.36 Å for a set of 23 amino acid Cα positions (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Monofoil and Monofoil P3 ab initio structures overlaid onto http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC β‐propeller subdomains. (a) A ribbon diagram of the Monofoil ab initio structure (blue) overlaid onto the fifth blade motif of clathrin terminal domain (research collaboratory for structural bioinformatics (RCSB) accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC). (b) A ribbon diagram of the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure (green) overlaid onto the second blade motif of clathrin terminal domain (RCSB accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC). (c) A ribbon diagram of http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC clathrin terminal domain (view down the pseudoaxis of rotational symmetry) with the locations of the overlays of Monfoil and Monofoil P3 ab initio structures (same color scheme as in panels a and b). RCSB, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics

2.6. Monofoil permutant P1

The top ab initio folding solution for the Monofoil P1 trefoil‐fold permutation sequence includes four β‐strands that are in generally good agreement with the β‐strand definitions from the same region in the Symfoil‐4P structure (Table S8). The individual β‐strand and turn secondary structure elements in the ab initio structure exhibit homology with the equivalent elements in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure, with the exception of the T3 region. However, the ab initio structure does not arrange the β‐strands in a conformation characteristic of a correspondingly circularly permuted β‐trefoil structure; instead, it forms a compact pair of antiparallel β‐hairpins (whose interface buries a total of eight hydrophobic amino acids) (Figures 5 and 6). Residue positions 22–34 of the ab initio structure overlay the same region in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure with an rmsd of 1.49 Å (for a total of 13 Cα positions). Thus, the first β‐hairpin in the Monofoil P1 ab initio structure comprises the majority of the Symfoil‐4P β2/T2/β3 hairpin structure. Positions 40–48 and 54–60 in the Monofoil P1 ab initio structure overlay residue positions 42–50 (β4) and 54–60 (β5/β1) in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure with a rmsd of 1.30 Å (involving 16 Cα positions). Thus, the second β‐hairpin in the ab initio structure has a structural relationship to the second β‐hairpin of the Symfoil‐4P structure albeit with a register shift of two amino acid positions in the β4 strand. The overall confidence value reported for the Monofoil P1 ab initio structure is 0.42. 3D Blast search does not identify any significant structural similarity of the Monofoil P1 ab initio structure with protein structures in the Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP) database.

2.7. Monofoil permutant P2

The top ab initio folding solution for the Monofoil P2 trefoil‐fold permutation sequence includes four β‐strands that are in good agreement with the β‐strand definitions from the same region in the Symfoil‐4P structure (Table S9). The individual β‐strand and turn secondary structure elements in the ab initio structure exhibit structural similarity with the equivalent elements in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure, with the exception of the T3 region. However, the ab initio structure does not arrange the β‐strands in a characteristic β‐trefoil conformation, instead forming a compact four‐stranded antiparallel β‐sheet conformation (Figure 5). An overlay of the ab initio structure onto the equivalent region of the Symfoil‐4P crystal structures shows that residue positions 42–49 and 54–65 as a set overlay with an rmsd of 1.08 Å (involving a total of 20 Cα positions). This region spans β4, β5(β1), T5(T1) and the N‐terminus of β6(β2) (omitting the T4 region of residues 50–53) (Figure 6). 3D Blast search identifies a region of structural similarity of the Monofoil P1 ab initio structure with a region in the Amaranthus caudatus agglutinin protein (RCSB accession 1JLY) which is another β‐trefoil protein. This region of homology includes a contiguous region between residues 36–65 (essentially the region identified above as having structural similarity with Symfoil‐4P). The positional uncertainty for the Monofoil P2 ab initio structure is greatest for the T3 region (Figure 5). The overall confidence value reported for the Monofoil P2 ab initio structure is 0.46.

2.8. Monofoil permutant P3

The top ab initio folding solution for the Monofoil P3 trefoil‐fold permutation sequence identifies four β‐strands that are in good agreement with the β‐strand definitions from the same region in the Symfoil‐4P structure (Table S10). The individual β‐strand and turn secondary structure elements in the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure exhibit structural similarity with the equivalent elements in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure, with the greatest deviation observed for the T4 region. However, the ab initio structure does not arrange the β‐strands in a characteristic β‐trefoil conformation, instead forming a compact four‐stranded antiparallel β‐sheet conformation (Figure 5). Residue positions 41–46 and 52–58 in the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure overlay residue positions 43–48 and 52–58 in the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure with a rmsd of 1.40 Å (for a total of 13 Cα positions). These regions describe the β4 and β5 (β1) strands which do not interact in the β‐trefoil motif; however, when trefoil‐folds exist as tandem repeats (as in the β‐trefoil fold) a novel β‐hairpin is generated (T4) and these β‐strands exhibit extensive antiparallel β‐sheet H‐bond interactions (in the β4/T4/β1 arrangement). While β4‐β5(β1) interstrand H‐bond interactions are observed in the ab initio structure, the register of strand positions in the β4 is offset by two amino acid positions in comparison to the equivalent strand interactions in the Symfoil‐4P structure. An overlay of residue positions 56–66 of the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure with the equivalent positions of the Symfoil‐4P crystal structure yields a rmsd of 0.85 Å (for a total of 11 Cα positions). This contiguous region spans the four C‐terminus amino acids of β5 (β1), T5(T1), and the four N‐terminus amino acids of β6 (β2). Thus, a wild‐type equivalent T5(T1) hairpin is correctly formed in the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure. An overlay of the ab initio structure onto the equivalent region of the Symfoil‐4P crystal structures shows that residue positions 63–76 as a set overlay with an rmsd of 1.12 Å (involving a total of 14 Cα positions). This region spans β6(β2), T6(T2), and β7(β3) which comprises the principle β‐hairpin at the bottom of the trefoil‐fold. A summary of the conserved structural subdomains in the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure is illustrated in Figure 6. The positional uncertainty for the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure is greatest for the T3 region (Figure 5). The overall confidence value reported for the E53stop ab initio structure is 0.47. A structural similarity search of the ab initio Monofoil P3 structure identifies a potential match with a region of the human clathrin terminal domain (RCSB accession http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC; described above for the Monofoil ab initio structure homology search). This structural similarity is for an integral blade definition, and an optimized structural overlay of the Monofoil P3 ab initio structure with the individual blades of the clathrin terminal domain yields an rmsd of 1.12 Å for a total of 29 Cα positions with blade #2 (residue positions 69–106 of http://firstglance.jmol.org/fg.htm?mol=1UTC; Figure 7).

3. DISCUSSION

Essentially correct ab initio structures were obtained for the FGF‐1 and Symfoil‐4P controls (comprising 12 β‐strands), suggesting that these all‐β proteins are amenable to ab initio structure prediction using New ROBETTA. Ab initio structure prediction with the FGF‐1 and Symfoil‐4P FN sequence controls (comprising seven β‐strands) were also in good agreement with the corresponding regions in the respective crystal structures, although these solutions exhibited aspects of structural collapse of specific β‐hairpins that limit solvent exposure of the hydrophobic core region. The ab initio predictions of the Monofoil and permutant sequences (comprising four β‐strands) were generally correct in identifying β‐strand secondary structure; however, the overall tertiary structure was dissimilar to the trefoil‐fold (or structural permutations thereof) in each case; however, for each polypeptide there were clear subregions of correct tertiary structure.

In the ab initio structure solutions for the set of Monofoil and permutant sequences the β‐hairpin structures involving turns T1 and T2 (if present in the permutation) were always correctly formed. In contrast, β‐hairpin structures involving turns T3 and T4 were not correctly formed in any sequence (Figure 6). Turn T3 is a long connecting turn/loop region (comprising 10 amino acids, whereas the other turns comprise three), and turn T4 is related by symmetry to the (discontinuous) N‐ and C‐termini (thus, T4 does not exist in the standard trefoil‐fold motif definition, but is created upon circular permutation). The Monofoil sequence has been shown to oligomerize as a trimer to generate an intact β‐trefoil protein.12, 14 Thus, Monofoil contains an effective FN; however, T4 does not exist in the Monofoil oligomeric architecture. Turns T1 and T2 contain the highest contact density and have been predicted to fold early in the β‐trefoil folding pathway; conversely, turn T3 (and T4 generated by tandem repeat) have been predicted to fold late in the folding pathway.25 The correct ab initio structures for the T1 and T2 β‐hairpins in Monofoil and permutants, and the lack of formation of T3 and T4 β‐hairpins, are therefore in agreement with previous data from ϕ‐value analysis and crystallography.

Formation of the adjacent T1 and T2 hairpins sets up the structural foundation of a three‐stranded antiparallel β‐strand arrangement. The Monofoil sequence has amino acid propensities favorable for the formation of four β‐strands, and this is consistently observed in all ab initio structures of Monofoil and permutants. However, the trefoil‐fold motif is not the most structurally compact arrangement for four antiparallel β‐strands; in fact, the C‐terminus strand is domain swapped into the following trefoil‐fold. Ab initio folding suggest the most compact arrangement (minimizing solvent exposure of the hydrophobic core region) exhibits greater structural similarity with the “blade” motif in the β‐propeller fold. Indeed, a structural similarity search for both the Monofoil and P3 ab initio structures identifies the same β‐propeller protein (clathrin terminal domain) (Figure 7). Such compact structures for the trefoil‐fold motif do not provide an extended β‐strand for insertion in domain swapping, and therefore, would be predicted to be monomeric. Expression of the permutant sequences yielded two (P1 and P3) that were soluble and monomeric by SEC analysis. Among these two peptides P3 provided sufficient material for IED and demonstrated non‐cooperative denaturation. Thus, the behavior of the available trefoil‐fold permutants suggests they are soluble, somewhat compact monomers, but with “molten globule” (i.e., structurally dynamic) properties.

The ab initio and experimental data indicate the potential for alternative secondary structure arrangements that provide for a soluble compact monomer while forming key elements of the trefoil‐fold structure. The yield of expressed circularly permuted Monofoil peptide followed the order of P3 > P1 > P2. This is not the order of thermostability observed for the similarly circularly permutated Symfoil‐4T β‐trefoil protein (P2 > P3 > P1). This result suggests that the circularly permuted monofoil structures adopt a conformation distinctly different from the native trefoil‐fold architecture, providing support for the ab initio structures. Thus, we hypothesize that early in the folding pathway of Monofoil (i.e., prior to intermolecular interactions), alternative conformations that are compact and soluble are potentially sampled. Structural dynamics afforded by a molten globule type conformation could readily promote domain swapping of the β4 strand during intermolecular interactions (facilitated by the highly flexible T3 region), thereby promoting oligomerization. Overall, the experimental and computational results in the present study suggest a U ↔ I ↔ N3 type folding pathway for Monofoil. The results also identify a likely possibility regarding the nature of the I state in this pathway. The ab initio structure predictions of the Monofoil and permutant sequences exhibit greater overall structural similarity to the blade motif of a β‐propeller fold than the trefoil‐fold. These two motifs share a number of basic structural features: both are approximately 40 amino acids in length and comprise four antiparallel β‐strands. This structural relationship suggests the possibility of a limited energetic difference between the two conformations; thus, the Monofoil I state is postulated to be a β‐propeller blade motif.

These results have implications for understanding the intersection of the evolutionary processes associated with conserved and emergent protein architecture models.12, 26, 27 In the emergent protein architecture model, a complex symmetric molecular architecture built up from several instances of repetitive motifs is achieved only after the final gene duplication/fusion event. Intermediate forms (i.e., those having fewer repeats) exhibit a simpler molecular architecture. In the conserved architecture model, complex molecular architecture is achieved even with a single motif via oligomerization of the requisite number of repeats. Both the β‐propeller and β‐trefoil architectures have experimental data supporting a conserved architecture model for their evolution.12, 13, 14, 28 The trefoil‐fold is the simplest motif definition in the β‐trefoil, and since it is asymmetric it cannot be further simplified using the conserved architecture model; however, this is not the case for the β‐propeller, where the blade motif exhibits twofold rotational symmetry of a β‐hairpin. Therefore, emergence of the trefoil‐fold from simpler structural motifs requires an emergent architecture model. One plausible pathway suggested by the current work would be to consider the blade motif as a structural ancestor of the trefoil‐fold, a structure that is potentially still adopted in the folding intermediate of the β‐trefoil. In other words, a single “metamorphic” blade motif could bridge these two distinct protein architectures.15, 29, 30 Sterner and coworkers have reported a striking structural and amino acid sequence similarity between subdomains of (βα)4 half‐barrels and members of the (βα)5 flavodoxin‐like fold—two different types of protein folds.31 This result prompted these investigators to propose that “a large fraction of the modern‐day enzymes evolved from a basic structural building block, which can be identified by a combination of sequence and structural analyses.” The present work supports and extends this hypothesis to include a possible relationship between the β‐trefoil and β‐propeller motifs.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Mutant design, protein expression, and purification

The “trefoil‐fold” motif polypeptides utilized in this study are based upon the de novo designed Symfoil‐4P β‐trefoil protein.12, 14 Symfoil‐4P contains an exact triplet repeat of a designed 42‐mer sequence and folds as a β‐trefoil protein with characteristic internal threefold rotational symmetry (RCSB accession 3O4D). The Symfoil‐4P protein was derived from FGF‐1 and maintains the FGF‐1 numbering scheme; furthermore, Symfoil‐4P is expressed with an N‐terminal 6xHis‐tag and 10 amino acid unstructured FGF‐1 leader sequence (Figure 4). Construction of a single instance of the trefoil‐fold was accomplished by introducing a stop codon at position E53 in Symfoil‐4P. This trefoil‐fold is therefore identical to the Monofoil polypeptide previously reported12, 14 with inclusion of the 10 amino acid FGF‐1 leader sequence.

Three circular permutants (“P1,” “P2,” and “P3”) of this Monofoil sequence were constructed by targeting surface‐exposed reverse turn regions that intersperse the four β‐strands in the secondary structure (Figure 4). This design follows the same convention as previously reported for circular permutants of the closely related Symfoil‐4T protein22 (although these permutants comprised intact β‐trefoil proteins and not individual trefoil‐fold polypeptides). Heterologous expression from Escherichia coli and purification of recombinant proteins followed previously published procedures32, 33 and utilized Ni‐nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) chelation with imidazole step elution, followed by Superdex 75 SEC (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Purified protein was exchanged into 50 mM sodium phosphate, 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, pH 7.5 (“Pi buffer”) or 20 mM N‐(2‐acetamido)iminodiacetic acid (ADA), 0.1 M NaCl, pH 6.6 (“ADA buffer”). An extinction coefficient of E 280 nm (0.1%, 1 cm) = 0.32 was used to determine protein concentration.12, 14, 22

4.2. Analytical SEC

Analytical SEC was performed using a Superdex 75 26 cm × 60 cm (26/60) SEC column (318 ml volume) controlled by an ÄKTAFPLC system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Chicago, IL). Sample volumes of 10 ml (~3% column volume) were loaded using a 10 ml Superloop and were resolved with 2.5 ml/min Pi buffer in each case. Chromatograms were quantified by absorbance at 280 nm and the loaded sample was adjusted to 10–100 mAU. The Monofoil protein sample was also resolved in Pi buffer containing 6 M GuHCl (i.e., fully denaturing buffer). A mass standard including bovine serum albumin (66.5 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29.0 kDa) and cytochrome C (12.3 kDa) in Pi buffer was used for column calibration. A standard curve was determined by linear fit to the elution volume and log of the mass standards; the apparent mass of experimental proteins was calculated using this standard curve (Figure S1).

4.3. Isothermal equilibrium denaturation

Monofoil and permutant P3 purified polypeptides provided yields sufficient for detailed biophysical study and were diluted to a final concentration of 2.0 μM in ADA buffer containing either 0.1 M (Monofoil) or 0.5 M (P3) increments of GuHCl denaturant. Samples were incubated 18 hr at 298 K to permit equilibrium. The fluorescence signal of these polypeptides is contributed principally by a single Tyr residue at position 22 (Figure 4). Fluorescence data were collected on a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a Pelletier controlled‐temperature regulator at 298 K and using a 1.0 cm path length quartz cuvette. An excitation wavelength (λ ex) of 280 nm was used, and the fluorescence emission (λ em) was measured between 290 and 400 nm with triplicate scans collected and averaged. The integrated fluorescence signal between 290 and 400 nm was plotted versus denaturant concentration. The Symfoil and Monofoil proteins are derived from FGF‐1 which is known to exhibit an atypically greater fluorescence quenching in the folded state,34 and this property carries over to the Monofoil P3 polypeptide. The IED data for Monofoil was fit to a two‐state trimer model of denaturation:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Co is the molar concentration of the trimer (F) state, and X U is the mole fraction of unfolded monomer (U). Nonlinear least squares fitting was performed using the DataFit software package (Oakdale Engineering, Oakdale, PA).

4.4. Ab initio structure prediction and analysis

Structure prediction from primary sequences utilized the New ROBETTA prediction server (http://new.robetta.org). All calculations utilized the ab initio option, in which the target starts as an extended chain and the ab initio ROSETTA fragment assembly method is used to fold the polypeptide.35, 36 The ab initio method samples around 1,000 models of the target, and these are clustered for model selection. The top five clusters are ranked by the model quality method ProQ2.37 The fragment sizes for all‐β proteins are 3–7 amino acids for short fragments and 4–10 amino acids for long fragments and all combinations are used.35 There is no sequence homolog exclusion when New ROBETTA picks fragments. If there are sequence homologs in the fragment PDB template database from which the fragment picker selects fragments, there may be a significant bias in modeling. All submitted primary sequences were shorter than the 150 amino acid limit recommended for the ab initio method.

4.5. Ab initio structure controls

Symfoil‐4P and FGF‐1 primary sequences were included in the ab initio calculations as controls since these proteins represent both naturally evolved and designed β‐trefoil architectures and crystal structures for both proteins have been reported.12, 14, 32, 38 Additionally, protein sequences for the FN regions of both FGF‐124 and the Symfoil‐4T variant of Symfoil‐4P25 were also included as controls. ϕ‐Value analyses indicate that these subregions of primary structure are natively structured in an on‐pathway folding transition state.

4.6. Ab initio structure analysis

The New ROBETTA output for the top solutions were queried for secondary and tertiary structure features (including predicted disordered regions), template modeling score (confidence) and Cα positional error estimates. Potential regions of structural similarity between the predicted ab initio structures and the FGF‐1, Symfoil‐4P or Symfoil‐4T reference structures were evaluated using the Swiss PDBViewer software39 with fragment searches using Cα atoms. Possible structural similarity between the top scoring ab initio structure and the SCOP 1.75 database was queried using the 3D‐Blast Protein Structure Search server (http://3d-blast.life.nctu.edu.tw/dbsas.php).40, 41 While the ab initio structure prediction utilized the complete primary structure in each case, the 3D homology search with 3D‐Blast omitted the N‐terminal His‐tag and 10 amino acid N‐terminal FGF‐1 leader sequence (which was typically flagged as an unstructured region in the ab initio calculation).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

M.B. is a cofounder and has equity ownership in Trefoil Therapeutics, Inc.

Supporting information

Data S1 Tables of secondary structure definitions from ab initio calculations of polypeptide sequences utilized in the study. Tables of rmsd values for comparison of ab initio and crystal structures for polypeptide sequences. Figure of SEC calibration standards. Figures of structural overlays (ribbon diagrams) of ab initio predicted structures and crystal structures for polypeptides utilized in the study. Figures of the error estimate of Cα positions for ab initio calculations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a research support agreement from Trefoil Therapeutics, Inc. C.A.T. was supported by a McKnight Fellowship. Support from the FSU department of Biomedical Sciences and Council on Research and Creativity is acknowledged.

Tenorio CA, Longo LM, Parker JB, Lee J, Blaber M. Ab initio folding of a trefoil‐fold motif reveals structural similarity with a β‐propeller blade motif. Protein Science. 2020;29:1172–1185. 10.1002/pro.3850

Funding information Trefoil Therapeutics Inc., Grant/Award Number: RF02551

REFERENCES

- 1. Lang D, Thoma R, Henn‐Sax M, Sterner R, Wilmanns M. Structural evidence for evolution of the beta/alpha barrel scaffold by gene duplication and fusion. Science. 2000;289:1546–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Richter M, Bosnali M, Carstensen L, et al. Computational and experimental evidence for the evolution of a (βα)8‐barrel protein from an ancestral quarter‐barrel stabilized by disulfide bonds. J Mol Biol. 2010;398:763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fülöp V, Jones DT. β propellers: Structural rigidity and functional diversity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chaudhuri I, Soding J, Lupas AN. Evolution of the β‐propeller fold. Proteins. 2008;71:795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Voet ARD, Noguchi H, Addy C, et al. Computational design of a self‐assembling symmetrical β‐propeller protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15102–15107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McLachlan AD. Three‐fold structural pattern in the soybean trypsin inhibitor (Kunitz). J Mol Biol. 1979;133:557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murzin AG, Lesk AM, Chothia C. β‐Trefoil fold. Patterns of structure and sequence in the kunitz inhibitors interleukins‐1β and 1α and fibroblast growth factors. J Mol Biol. 1992;223:531–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eck RV, Dayhoff MO. Evolution of the structure of ferredoxin based on living relics of primitive amino acid sequences. Science. 1966;152:363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ohno S. Evolution by gene duplication. New York: Allen and Unwin, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLachlan AD. Repeating sequences and gene duplication in proteins. J Mol Biol. 1972;64:417–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yadid I, Tawfik DS. Functional β‐propeller lectins by tandem duplications of repetitive units. Prot Eng Des Sel. 2011;24:185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee J, Blaber M. Experimental support for the evolution of symmetric protein architecture from a simple peptide motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:126–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Broom A, Doxey AC, Lobsanov YD, et al. Modular evolution and the origins of symmetry: Reconstruction of a three‐fold symmetric globular protein. Structure. 2012;20:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee J, Blaber SI, Dubey VK, Blaber M. A polypeptide "building block" for the β‐trefoil fold identified by "top‐down symmetric deconstruction". J Mol Biol. 2011;407:744–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yadid I, Kirshenbaum N, Sharon M, Dym O, Tawfik DS. Metamorphic proteins mediate evolutionary transitions of structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7287–7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yadid I, Tawfik DS. Reconstruction of functional β‐propeller lectins via homo‐oligomeric assembly of shorter fragments. J Mol Biol. 2007;365:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bennett MJ, Schlunegger MP, Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: A mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2455–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ogihara NL, Ghirlanda G, Bryson JW, Gingery M, DeGrado WF, Eisenberg D. Design of three‐dimensional domain‐swapped dimers and fibrous oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1404–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raaijmakers H, Vix O, Toro I, Golz S, Kemper B, Suck D. X‐ray structure of T4 endonuclease VII: A DNA junction resolvase with a novel fold and unusual domain‐swapped dimer architecture. EMBO J. 1999;18:1447–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jung J, Lee B. Circularly permuted proteins in the protein structure database. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1881–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luger K, Hommel U, Herold M, Hofsteenge J, Kirschner K. Correct folding of circularly permuted variants of a βα barrel enzyme in vivo. Science. 1989;243:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Longo LM, Lee J, Tenorio CA, Blaber M. Alternative folding nuclei definitions facilitate the evolution of a symmetric protein fold from a smaller peptide motif. Cell Struct. 2013;21:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rousseau F, Schymkowitz JWH, Wilkinson HR, Itzhaki LS. The structure of the transition state for folding of domain‐swapped dimeric p13suc1. Structure. 2002;10:649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Longo L, Lee J, Blaber M. Experimental support for the foldability‐function tradeoff hypothesis: Segregation of the folding nucleus and functional regions in FGF‐1. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1911–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xia X, Longo LM, Sutherland MA, Blaber M. Evolution of a protein folding nucleus. Protein Sci. 2015;25:1227–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balaji S. Internal symmetry in protein structures: Prevalence, functional relevance and evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;32:156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blaber M, Lee J, Longo L. Emergence of symmetric protein architecture from a simple peptide motif: Evolutionary models. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:3999–4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smock Robert G, Yadid I, Dym O, Clarke J, Tawfik Dan S. De novo evolutionary emergence of a symmetrical protein is shaped by folding constraints. Cell. 2016;164:476–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murzin AG. Metamorphic proteins. Science. 2008;320:1725–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lella M, Mahalakshmi R. Metamorphic proteins: Emergence of dual protein folds from one primary sequence. Biochemistry. 2017;56:2971–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hocker B, Schmidt S, Sterner R. A common evolutionary origin of two elementary enzyme folds. FEBS Lett. 2002;510:133–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brych SR, Blaber SI, Logan TM, Blaber M. Structure and stability effects of mutations designed to increase the primary sequence symmetry within the core region of a β‐trefoil. Protein Sci. 2001;10:2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brych SR, Dubey VK, Bienkiewicz E, Lee J, Logan TM, Blaber M. Symmetric primary and tertiary structure mutations within a symmetric superfold: A solution, not a constraint, to achieve a foldable polypeptide. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blaber SI, Culajay JF, Khurana A, Blaber M. Reversible thermal denaturation of human FGF‐1 induced by low concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride. Biophys J. 1999;77:470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raman S, Vernon R, Thompson J, et al. Structure prediction for CASP8 with all‐atom refinement using Rosetta. Proteins. 2009;77:89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song Y, DiMaio F, Wang Ray Y‐R, et al. High‐resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure. 2013;21:1735–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uziela K, Wallner B. ProQ2: Estimation of model accuracy implemented in Rosetta. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1411–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Blaber M, DiSalvo J, Thomas KA. X‐ray crystal structure of human acidic fibroblast growth factor. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2086–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS‐MODEL and the Swiss‐PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tung C‐H, Huang J‐W, Yang J‐M. Kappa‐alpha plot derived structural alphabet and BLOSUM‐like substitution matrix for rapid search of protein structure database. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R31–R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang J‐M, Tung C‐H. Protein structure database search and evolutionary classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3646–3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Tables of secondary structure definitions from ab initio calculations of polypeptide sequences utilized in the study. Tables of rmsd values for comparison of ab initio and crystal structures for polypeptide sequences. Figure of SEC calibration standards. Figures of structural overlays (ribbon diagrams) of ab initio predicted structures and crystal structures for polypeptides utilized in the study. Figures of the error estimate of Cα positions for ab initio calculations.