To the Editor

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic poses the most significant modern-day public health challenge since the Spanish flu of 1918, causing substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 Coronavirus disease 2019 predominantly affects the respiratory system, causing severe pneumonia and respiratory distress syndrome. There is also involvement of multiple organs, and the cardiovascular system has been implicated. In a recent study to investigate characteristics and prognostic factors in 339 elderly patients with COVID-19, Wang and colleagues observed a high proportion of severe and critical cases as well as high fatality rates.2 The cardiovascular complications recorded were acute cardiac injury (21%), arrhythmia (10.4%) and cardiac insufficiency (17.4%). However, not all cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are clearly defined by published studies and it is also not clear if these conditions are directly caused by COVID-19 or are just unspecific complications.3 There is a need to understand the interplay between COVID-19 and its cardiovascular manifestations to assist in the optimum management of patients. In this context, we conducted a systematic meta-analysis to attempt to address the following questions: (i) what are the cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19?; (ii) what is the incidence of these complications?; and (iii) are patients with pre-existing cardiovascular morbidities more susceptible to these cardiovascular complications?

The protocol for this review was registered in the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42020184851). The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines4 , 5 (Supplementary Materials 1-2). We searched MEDLINE, Embase, and The Cochrane library from 2019 to 27 May 2020 for published studies reporting on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Details of the search strategy are reported in Supplementary Material 3. The prevalence of comorbidities (pre-existing hypertension and cardiovascular disease, CVD) and incidence of cardiovascular complications across studies with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled using Freeman-Tukey variance stabilising double arcsine transformation and random-effects models. STATA release MP 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Seventeen retrospective cohort studies comprising of 5,815 patients with COVID-19 were included (Table 1 ; Supplementary Materials 4-5). Eleven studies were based in China, four in the USA, one in South Korea and one in the Netherlands. The average age at baseline ranged from 47 to 71 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year of publication | Source of data | Country | Dates of data collection | Mean/median age (years) | Male % | Hospitalisation (days) | No. of patients | CVD complications | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guo, 2020 | Seventh Hospital of Wuhan City | China | Jan - Feb 2020 | 58.5 | 48.7 | 16.3 | 187 | Myocardial injury; ventricular arrhythmia | 5 |

| Wang, 2020 | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University | China | Jan, 2020 | 56.0 | 54.3 | 7.0 | 138 | Myocardial injury; cardiac arrhythmia | 4 |

| Huang, 2020 | Jin Yintan Hospital, Wuhan | China | Dec - Jan 2020 | 49.0 | 73.0 | 7.0 | 41 | Myocardial injury | 4 |

| Zhou, 2020 | Jinyintan Hospital & Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital | China | Dec - Jan 2020 | 56.0 | 62.0 | 11.0 | 191 | Myocardial injury; HF | 5 |

| Shi,2020 | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University | China | Jan - Feb 2020 | 64.0 | 49.3 | NR | 416 | Myocardial injury | 6 |

| Arentz, 2020 | Evergreen Hospital in Kirkland, Washington | USA | Feb - March 2020 | 70.0 | 52.0 | 5.2 | 21 | Cardiomyopathy | 4 |

| Chen, 2020 | Tongji Hospital in Wuhan | China | Jan - Feb 2020 | 62.0 | 62.0 | 13.0 | 274 | Myocardial injury; HF; DIC | 4 |

| Du, 2020 | Hannan Hospital and Wuhan Union Hospital | China | Jan - Feb 2020 | 65.8 | 72.9 | 10.1 | 85 | Cardiac arrest; ACS; arrhythmia; DIC | 4 |

| Wang, 2020b | Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University | China | Jan - Feb 2020 | 71.0 | 49.0 | 28.0 | 339 | Myocardial injury, arrhythmia HF | 4 |

| Cao, 2020 | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University | China | Jan - Feb 2020 | 54.0 | 52.0 | 11.0 | 102 | Myocardial injury; arrhythmia; cardiac arrest | 4 |

| Klok, 2020 | Dutch Univesity Hospitals | Netherlands | March - April 2020 | 64.0 | 76.0 | 7.0 | 184 | PE; VTE; stroke | 4 |

| Aggarwal, 2020 | UnityPoint Clinic | USA | March - April 2020 | 67.0 | 75.0 | 2.0 | 16 | ACS; cardiac arrhythmia; HF | 4 |

| Wang, 2020c | Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University and Xishui People's Hospital | China | Up to Feb, 2020 | 51.0 | 53.3 | 11.0 | 107 | Myocardial injury | 5 |

| Hong, 2020 | Yeungnam University Medical Center | South Korea | Up to March, 2020 | 55.4 | 38.8 | 7.7 | 98 | Myocardial injury | 4 |

| Wan, 2020 | Northeast Chongqing | China | Jan – Feb 2020 | 47.0 | 53.3 | 5.0 | 135 | Myocardial injury | 4 |

| Price-Haywood, 2020 | Ochsner Health in Louisiana | Asia | March – April, 2020 | 55.5 | 45.7 | 7.0 | 1,030 | Cardiomyopathy/HF | 6 |

| Price-Haywood, 2020 | Ochsner Health in Louisiana | Asia | March – April, 2020 | 53.6 | 37.7 | 6.0 | 2,451 | Cardiomyopathy/HF | 6 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; HF, heart failure; NOS, Newcastle Ottawa Scale; NR, not reported; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism

Across 15 studies, the pooled prevalence of pre-existing hypertension (95% CI) in COVID-19 patients was 29.3% (25.5-33.4; I 2 =87%; 95% CI 79, 91%; p for heterogeneity<0.01) (Supplementary Material 6). The prevalence (95% CI) of pre-existing CVD across 16 studies was 14.6% (11.0-18.4; I 2 =91%; 95% CI 87, 94%; p for heterogeneity<0.01) (Supplementary Material 7).

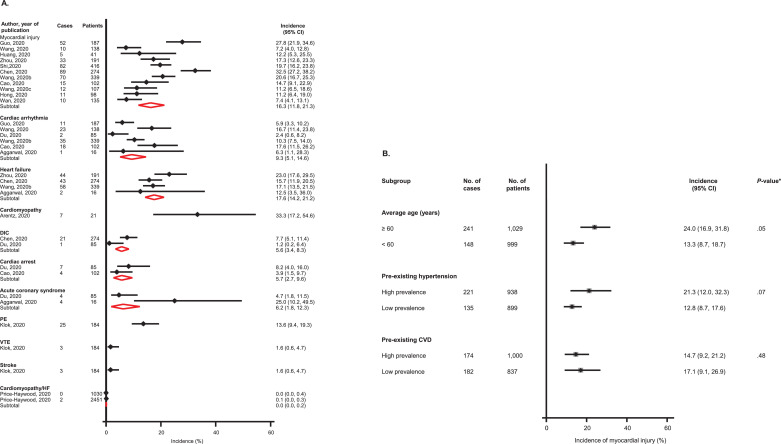

Over hospital stays ranging from 2 to 28 days, the pooled incidence was 17.6% (14.2-21.2; I 2 =32%; 95% CI 0, 76%; p for heterogeneity=0.20) for heart failure (HF) (n=4 studies); 16.3% (11.8-21.3; I 2 =87%; 95% CI 79, 92%; p for heterogeneity<0.01) for myocardial injury (n=11 studies); 9.3% (5.1-14.6; I 2 =78%; 95% CI 52, 90%; p for heterogeneity<0.01) for cardiac arrhythmia (n=6 studies); 6.2% (1.8-12.3) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (n=2 studies); 5.7% (2.7-9.6) for cardiac arrest (n=2 studies); and 5.6% (3.4-8.3) for disseminated intravascular dissemination (DIC) (n=2 studies) (Fig. 1 A). Subgroup analyses suggested that the incidence of myocardial injury was higher in older age groups and groups with a higher prevalence of pre-existing hypertension; however, the incidence of myocardial injury was similar in groups with high or low prevalence of pre-existing CVD (Fig. 1B). Over hospital stays ranging from 2 to 28 days following admission, mortality rate ranged from 0.7% to 52.4%, with a pooled rate of 15.3% (10.7-20.5).

Fig. 1.

(A) Incidence of cardiovascular complications in COVID-19 patients; (B) Incidence of myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients, by clinically relevant characteristics

CI, confidence interval (bars); CVD, cardiovascular disease; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism; *, p-value for meta-regression

The current data based on up-to-date evidence suggests that the most common cardiovascular complications of COVID-19 are HF, myocardial injury and cardiac arrhythmias. Though the mechanisms for cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 are still yet to be elucidated, the following multiple pathways have been proposed: (i) direct cardiotoxicity; (ii) systemic inflammation; (iii) myocardial demand-supply mismatch; (iv) plaque rupture and coronary thrombosis; (v) adverse effects of therapies during hospitalisation; (vi) sepsis leading to DIC; (vii) increased systemic thrombogenesis; and (viii) electrolyte imbalances.6 , 7 Myocardial injury is reported to mainly result from direct viral involvement of cardiomyocytes and the effects of systemic inflammation.6 Though venous thromboembolism incidence was based on a single report, patients with COVID-19 are at increased risk of hypercoagulable states due to prolonged immobilisation, systemic inflammation and risk for DIC.7

In addition to pre-existing comorbidities including CVD being associated with worse outcomes in patients with COVID-19,8 , 9 cardiovascular complications such as myocardial injury have also been shown to be associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19 and fatal outcomes.10 Myocardial injury is commonly defined as substantial elevation of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin levels and it has been reported that elevated troponin levels are associated with greater risk of severe disease and mortality.10 Monitoring of markers of cardiac damage such as troponin, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide and creatine kinase during hospitalisation for COVID-19 could help in the identification of patients with possible cardiac manifestations, to enable early and more aggressive intervention.

The inherent limitations of this review included the low sample sizes and methodological design of some of the studies, which was expected given the urgency to report and gain a better understanding of COVID-19; limited number of studies available, hence some of the findings were based on single reports; assays for cardiac injury and their time of assessment during hospitalisation may vary between studies, hence estimates may be biased; and the possibility of patient overlap given that the majority of studies were conducted from China and reports of duplicate publication of study participants in articles.9

Aggregate analysis of the literature suggests that the most frequent cardiovascular complications among patients hospitalised with COVID-19 are HF, myocardial injury, cardiac arrhythmias and ACS. Early identification and monitoring of cardiac complications could help in the prediction of more favourable outcomes. The causes of these cardiovascular manifestations warrant further investigation as more data becomes available.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

SKK acknowledges support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. These sources had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.068.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, He W, Yu X. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari R, Di Pasquale G, Rapezzi C. 2019 CORONAVIRUS: What are the implications for cardiology? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(8):793–796. doi: 10.1177/2047487320918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bansal M. Cardiovascular disease and COVID-19. Diabetes & metabolic syndrome. 2020;14(3):247–250. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang Y, Chen T, Mui D. Cardiovascular manifestations and treatment considerations in covid-19. Heart. 2020 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss P, Murdoch DR. Clinical course and mortality risk of severe COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1014–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30633-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunutsor SK, Laukkanen JA. Markers of liver injury and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.