Abstract

Some patients with cancer use adjunctive Chinese medicine, which might improve the quality of life. This study aims to investigate the effects and relative factors of adjunctive Chinese medicine on survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients at different stages. The study population was 23 581 newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma patients and received surgery from 2004 to 2010 in Taiwan. After propensity score matching with a ratio of 1:10, this study included 1339 hepatocellular carcinoma patients who used adjunctive Chinese medicine and 13 390 hepatocellular carcinoma patients who used only Western medicine treatment. All patients were observed until the end of 2012. Kaplan-Meier method and Cox proportional hazards model was applied to find the relative risk of death between these 2 groups. The study results show that the relative risk of death was lower for patients with adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment than patients with only Western medicine treatment (hazard ratio = 0.68; 95% confidence interval = 0.62-0.74). The survival rates of patients with adjunctive Chinese medicine or Western medicine treatment were as follows: 1-year survival rate: 83% versus 72%; 3-year survival rate: 53% versus 44%; and 5-year survival rate: 40% versus 31%. The factors associated with survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients included treatment, demographic characteristics, cancer stage, health status, physician characteristics, and characteristics of primary medical institution. Moreover, stage I and stage II hepatocellular carcinoma patients had better survival outcome than stage III patients by using adjunctive Chinese medicine therapy. The effect of adjunctive Chinese medicine was better on early-stage disease.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, treatment of cancer, adjunctive Chinese medicine therapy, surgery, survival analysis

Introduction

With the incidence of cancer increasing annually, this disease has become one of the most prominent health issues affecting humans worldwide. According to the World Health Organization,1 approximately 780 000 new cases of liver cancer were reported worldwide in 2012. The incidence rate was 10.1 per 100 000 people, and the mortality rate was 5.1 per 100 000, the latter of which was ranked second among deaths caused by cancer. The incidence and mortality rates of liver cancer in Taiwan are higher than the global average; in 2011, the number of confirmed cases of liver cancer in Taiwan was approximately 11 292, and the incidence and mortality rates were 35.79 and 24.95 per 100 000 people, respectively. Liver cancer was ranked second among all deaths caused by cancer in Taiwan.2 Currently, 3 methods are available for cancer treatment: Western medicine treatment, Chinese medicine treatment, and combined Chinese-Western medicine treatment (ie, adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment). Many cancer patients who receive Western medicine treatment also seek and use Chinese medicine treatment as adjunctive therapy. The use of Chinese medicine treatment in Taiwan has increased among patients with liver cancer, and the ratio of Chinese medicine treatment users remains high (18.89%).3 A previous study showed that the use of Chinese medicine treatment by cancer patients significantly improved their overall quality of life and body functions.4 In addition, the use of adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment significantly elevated the survival rate of lung cancer patients as well as their prognostic results.5 The mortality rate from liver cancer is higher among men compared with their female counterparts,6 and the risk increases with age.7,8 Furthermore, low socioeconomic status or family income, severity of comorbidity, and liver cancer stage increase the risk of death.6,9-12 Other related factors influencing the survival rate of cancer patients include medical institution characteristics,13,14 physician service volume, and physician age.14,15

Previous studies5,16 have shown that adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment can significantly improve the survival rates of patients with cancer (eg, breast cancer patients and lung cancer patients). However, few studies have investigated the difference in the survival rates of liver cancer patients between Western medicine treatment and adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate the effect of adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment on the survival rate of patients with liver cancer.

Materials and Methods

Research Database

This retrospective cohort study examined the Taiwan Cancer Registry for the 2004 to 2010 period, the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) for the 2002 to 2012 period, and the Cause of Death Data for the 2004 to 2012 period. The cancer registry data were obtained from the Health Promotion Administration, and the other data were obtained from the Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Taiwan Cancer Registry contains information on numerous cancer cases as well as relevant information such as patients’ cancer stage. Diagnosis of cancer is confirmed according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3), which identifies cancer categories according to primary site, histology, behavioral code, and classification/differentiation. In determining the cancer stage according to diagnostic results, the Taiwan Cancer Registry assesses the severity of cancer clinically, surgically, and pathologically in accordance with the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).17 The NHIRD contains comprehensive health care–related information such as the characteristics of Taiwan’s health care providers and patients’ demographic information and all medical records including Western medicine and Chinese medicine. As of 2013, 23 462 863 people were enrolled in the National Health Insurance (NHI) program, accounting for approximately 99.6% of people living in Taiwan.18

Study Population

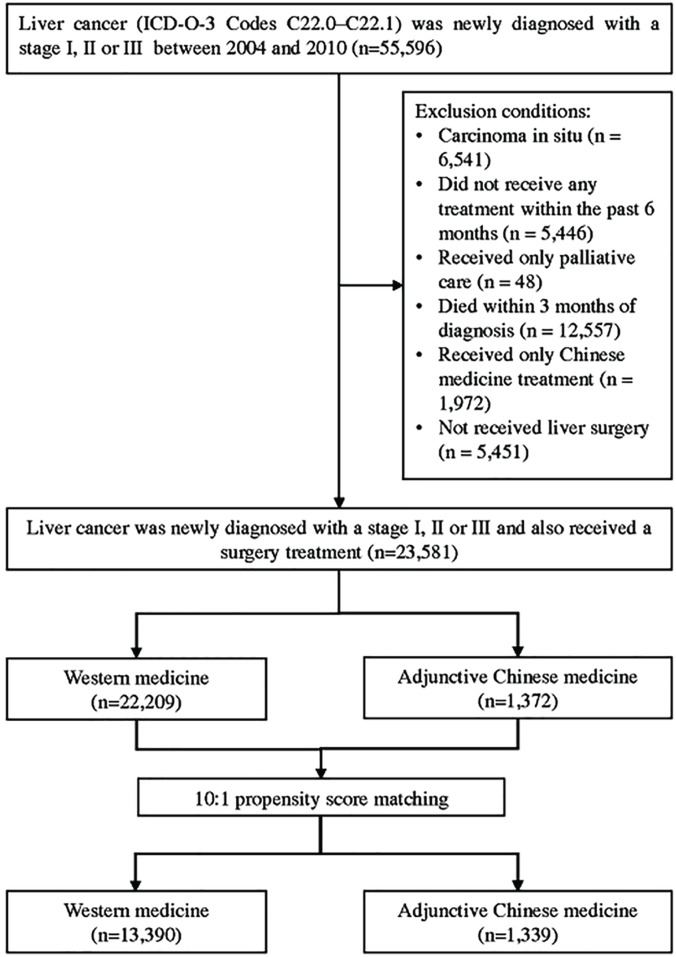

In this study, patients whose liver cancer (ICD-O-3 codes C22.0-C22.1) was newly diagnosed with a stage I, II, or III and also received a surgery treatment between 2004 and 2010 were selected as the study participants, and they were followed up until December 31, 2012. Patients were excluded if they had carcinoma in situ (n = 6541), did not receive any treatment within the past 6 months (n = 5446), received only palliative care (n = 48), died within 3 months of diagnosis (n = 12 557), received only Chinese medicine treatment (n = 1972), or did not receive liver surgery (n = 5451; Figure 1). In the present study, the 2 treatments were defined according to Lee et al,16 as follows:

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the selection of study participants.

Western medicine treatment: patients who received Western medicine treatment within 1 year of diagnosis and <30 days of Chinese medicine treatment.

Adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment: patients who received Western medicine treatment and ≥30 days of Chinese medicine treatment within 1 year of diagnosis.

All liver cancer patients were enrolled in the NHI program and had high accessibility to Western Medicine. All cancer patients were exempted from payments for cancer treatments under the NHI. Western Medicine was the primary treatment for all patients in our study. The exposure of Western Medicine was comparable in the 2 cohorts.

To facilitate a more accurate comparison of the survival rates between the patients who underwent Western medicine treatment and those who underwent adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment, this study adopted the propensity score matching (PSM) with the greedy matching by digit without replacement method to eliminate characteristic differences between the 2 groups with a ratio of 1:10.19 It was the conditional probability of the patients receiving adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment, and its calculation was based on the variables that are given in Table 1. Using the multivariate logistic regression model, the probability of the patients receiving adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment was estimated for matching between the 2 groups. The groups were matched by sex, age, monthly salary, urbanization level of residence location, other catastrophic illnesses or injuries, severity of comorbidity hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, cirrhosis, cancer stage, and treatment methods.

Table 1.

Differences Between the Variables Prior to and After Propensity Score Matching for Patients Who Received Western Medicine Treatment and Those Who Received Adjunctive Chinese Medicine Treatment (2004-2010).

| Variables | Before Propensity Score

Matching |

After Propensity Score

Matching |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Western Medicine | Adjunctive Chinese Medicine | P | Total | Western Medicine | Adjunctive Chinese Medicine | P | |||||||

| N | % | n1 | % | n2 | % | N | % | n1 | % | n2 | % | |||

| Total number | 23 581 | 100.00 | 22 209 | 94.18 | 1372 | 5.82 | 14 729 | 100.00 | 13 390 | 90.91 | 1339 | 9.09 | ||

| Gender | .068 | .998 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 16 709 | 70.86 | 15 707 | 94.00 | 1002 | 6.00 | 10 675 | 72.48 | 9704 | 90.90 | 971 | 9.10 | ||

| Female | 6872 | 29.14 | 6502 | 94.62 | 370 | 5.38 | 4054 | 27.52 | 3686 | 90.92 | 368 | 9.08 | ||

| Age | <.001 | .321 | ||||||||||||

| ≤40 | 1052 | 4.46 | 969 | 92.11 | 83 | 7.89 | 784 | 5.32 | 709 | 90.43 | 75 | 9.57 | ||

| 41-50 | 2791 | 11.84 | 2590 | 92.80 | 201 | 7.20 | 1948 | 13.23 | 1755 | 90.09 | 193 | 9.91 | ||

| 51-60 | 5807 | 24.63 | 5415 | 93.25 | 392 | 6.75 | 4009 | 27.22 | 3634 | 90.65 | 375 | 9.35 | ||

| ≥61 | 13 931 | 59.08 | 13 235 | 95.00 | 696 | 5.00 | 7988 | 54.23 | 7292 | 91.29 | 696 | 8.71 | ||

| Monthly salary (NTD) | <.001 | .901 | ||||||||||||

| Low-income household | 186 | 0.79 | 178 | 95.70 | 8 | 4.30 | 85 | 0.58 | 77 | 90.59 | 8 | 9.41 | ||

| ≤17 280 | 1059 | 4.49 | 996 | 94.05 | 63 | 5.95 | 644 | 4.37 | 581 | 90.22 | 63 | 9.78 | ||

| 17 280-22 800 | 13 259 | 56.23 | 12 573 | 94.83 | 686 | 5.17 | 7797 | 52.94 | 7111 | 91.20 | 686 | 8.80 | ||

| 22 801-28,800 | 3308 | 14.03 | 3130 | 94.62 | 178 | 5.38 | 1999 | 13.57 | 1821 | 91.10 | 178 | 8.90 | ||

| 28 801-36 300 | 1580 | 6.70 | 1469 | 92.97 | 111 | 7.03 | 1126 | 7.64 | 1017 | 90.32 | 109 | 9.68 | ||

| 36 301-45 800 | 2002 | 8.49 | 1857 | 92.76 | 145 | 7.24 | 1442 | 9.79 | 1307 | 90.64 | 135 | 9.36 | ||

| 45 801-57 800 | 854 | 3.62 | 792 | 92.74 | 62 | 7.26 | 604 | 4.10 | 545 | 90.23 | 59 | 9.77 | ||

| ≥57 801 | 1333 | 5.65 | 1214 | 91.07 | 119 | 8.93 | 1032 | 7.01 | 931 | 90.21 | 101 | 9.79 | ||

| Urbanization level of residence location | .004 | .999 | ||||||||||||

| Level 1 | 5901 | 25.02 | 5532 | 93.75 | 369 | 6.25 | 3898 | 26.46 | 3539 | 90.79 | 359 | 9.21 | ||

| Level 2 | 6807 | 28.87 | 6396 | 93.96 | 411 | 6.04 | 4393 | 29.83 | 3995 | 90.94 | 398 | 9.06 | ||

| Level 3 | 3431 | 14.55 | 3225 | 94.00 | 206 | 6.00 | 2151 | 14.60 | 1953 | 90.79 | 198 | 9.21 | ||

| Level 4 | 4010 | 17.01 | 3796 | 94.66 | 214 | 5.34 | 2405 | 16.33 | 2193 | 91.19 | 212 | 8.81 | ||

| Level 5 | 966 | 4.10 | 933 | 96.58 | 33 | 3.42 | 371 | 2.52 | 338 | 91.11 | 33 | 8.89 | ||

| Level 6 | 1364 | 5.78 | 1275 | 93.48 | 89 | 6.52 | 954 | 6.48 | 865 | 90.67 | 89 | 9.33 | ||

| Level 7 | 1102 | 4.67 | 1052 | 95.46 | 50 | 4.54 | 557 | 3.78 | 507 | 91.02 | 50 | 8.98 | ||

| Other catastrophic illnesses or injuries | <.001 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| No | 21 317 | 90.40 | 20 024 | 93.93 | 1293 | 6.07 | 13 855 | 94.07 | 12 595 | 90.91 | 1260 | 9.09 | ||

| Yes | 2264 | 9.60 | 2185 | 96.51 | 79 | 3.49 | 874 | 5.93 | 795 | 90.96 | 79 | 9.04 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | .010 | .961 | ||||||||||||

| ≤3 | 20 250 | 85.87 | 19 034 | 94.00 | 1216 | 6.00 | 13 050 | 88.60 | 11 866 | 90.93 | 1184 | 9.07 | ||

| 4-6 | 2634 | 11.17 | 2513 | 95.41 | 121 | 4.59 | 1290 | 8.76 | 1170 | 90.70 | 120 | 9.30 | ||

| ≥7 | 697 | 2.96 | 662 | 94.98 | 35 | 5.02 | 389 | 2.64 | 354 | 91.00 | 35 | 9.00 | ||

| Hepatitis B virus | <.001 | .792 | ||||||||||||

| No | 12 992 | 55.10 | 12 310 | 94.75 | 682 | 5.25 | 7525 | 51.09 | 6846 | 90.98 | 679 | 9.02 | ||

| Yes | 10 589 | 44.90 | 9899 | 93.48 | 690 | 6.52 | 7204 | 48.91 | 6544 | 90.84 | 660 | 9.16 | ||

| Hepatitis C virus | .012 | .660 | ||||||||||||

| No | 14 448 | 61.27 | 13 563 | 93.87 | 885 | 6.13 | 9296 | 63.11 | 8443 | 90.82 | 853 | 9.18 | ||

| Yes | 9133 | 38.73 | 8646 | 94.67 | 487 | 5.33 | 5433 | 36.89 | 4947 | 91.05 | 486 | 8.95 | ||

| Cirrhosis | <.001 | .317 | ||||||||||||

| No | 6272 | 26.60 | 5851 | 93.29 | 421 | 6.71 | 4199 | 28.51 | 3801 | 90.52 | 398 | 9.48 | ||

| Yes | 17 309 | 73.40 | 16 358 | 94.51 | 951 | 5.49 | 10 530 | 71.49 | 9589 | 91.06 | 941 | 8.94 | ||

| Cancer stage | <.001 | .424 | ||||||||||||

| Stage I | 9527 | 40.40 | 8899 | 93.41 | 628 | 6.59 | 6350 | 43.11 | 5751 | 90.57 | 599 | 9.43 | ||

| Stage II | 6384 | 27.07 | 6028 | 94.42 | 356 | 5.58 | 3931 | 26.69 | 3579 | 91.05 | 352 | 8.95 | ||

| Stage III | 7670 | 32.53 | 7282 | 94.94 | 388 | 5.06 | 4448 | 30.20 | 4060 | 91.28 | 388 | 8.72 | ||

| Treatment methods | <.001 | .330 | ||||||||||||

| OP + CH + TACE | 5517 | 23.40 | 5268 | 95.49 | 249 | 4.51 | 3032 | 20.59 | 2783 | 91.79 | 249 | 8.21 | ||

| OP | 4723 | 20.03 | 4296 | 90.96 | 427 | 9.04 | 3921 | 26.62 | 3527 | 89.95 | 394 | 10.05 | ||

| OP + CH + RT + TACE | 2787 | 11.82 | 2619 | 93.97 | 168 | 6.03 | 1926 | 13.08 | 1758 | 91.28 | 168 | 8.72 | ||

| OP + RT | 2531 | 10.73 | 2408 | 95.14 | 123 | 4.86 | 1413 | 9.59 | 1290 | 91.30 | 123 | 8.70 | ||

| OP + TACE | 2318 | 9.83 | 2215 | 95.56 | 103 | 4.44 | 1164 | 7.90 | 1061 | 91.15 | 103 | 8.85 | ||

| OP + CH | 1665 | 7.06 | 1553 | 93.27 | 112 | 6.73 | 1120 | 7.60 | 1008 | 90.00 | 112 | 10.00 | ||

| OP + RFA | 1730 | 7.34 | 1660 | 95.95 | 70 | 4.05 | 799 | 5.42 | 729 | 91.24 | 70 | 8.76 | ||

| OP + CH + RT | 1300 | 5.51 | 1228 | 94.46 | 72 | 5.54 | 814 | 5.53 | 742 | 91.15 | 72 | 8.85 | ||

Abbreviations: NTD, New Taiwan dollar; OP, surgery; CH, chemotherapy; TACE, embolization; RT, radiography; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Statistical Analysis

The data were processed and analyzed using SAS Version 9.4. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted with the level of significance set at α = .05.

Cancer stage was defined according to the TNM staging system of the AJCC (ie, stages I-III).20 Area of residence was divided into 7 categories according to the degree of urbanization, with a value of 1 indicating the highest degree of urbanization. To evaluate the severity of comorbidities, primary and secondary diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, were converted into weighted scores. The weighted scores were subsequently summed to obtain the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),21 which was then applied to calculate the comorbidity scores. These scores, which represented the severity of the comorbidities, were divided into 3 levels (≤3, 4-6, and ≥7). Patients were considered to have other catastrophic illnesses or injuries only if other catastrophic illnesses or injuries had been diagnosed prior to their liver cancer diagnosis. Primary medical institution was determined according to the type of health care facility that the patients frequented the most for treatment during the observation period. The service volume of hospitals or physicians was defined as the number of liver cancer patients who were treated in a given year by the hospital or physician. The service volume of hospitals or physicians was divided into 3 levels by interquartile range: low (≤25%), median (25% to 75%), and high (≥75%).

After the study population was divided into Western and adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment groups, the χ2 test was applied to identify any differences in the demographic information, liver cancer stage, and health status of the 2 groups before and after conducting the PSM with a 1:10 matching ratio by using greedy matching by digit without replacement. Cox proportional hazards models were employed to examine related factors influencing the survival rate of the patients with liver cancer, and the patients’ survival period was measured in years. The independent variables in the analysis were cancer treatment method, demographic characteristics, liver cancer stage, health status, physician characteristics, and characteristics of primary medical institution. The dependent variable was whether the patients survived. Last, patient survival was analyzed and calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method according to 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates. The results were employed to plot the survival curves for both of the treatment methods (for all patients and stratified by cancer stage). The log-rank test was then used to test the differences in the patient survival rates. This study has been approved by the research ethics committee in China Medical University (Institutional Review Board No. CMU-REC-101-012).

Results

Characteristics of Liver Cancer Patients Prior to and After PSM

Table 1 shows that prior to PSM, the sex, age, monthly salary, urbanization level of residence location, other catastrophic illnesses or injuries, severity of comorbidity, whether or not the liver cancer patients had hepatitis B virus, whether or not the liver cancer patients had hepatitis C virus, whether or not the liver cancer patients had cirrhosis, cancer stage, and treatment methods of liver cancer patients who underwent Western medicine treatment differed significantly from those who underwent adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment (P < .05). PSM was subsequently employed, and liver cancer patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment (n = 1339) were matched with those who received Western medicine treatment (n = 13 390). The patients who underwent adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment were mostly men (9.10%). The largest groups of patients who had received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment were patients ≥61 years of age (8.71%), monthly salary in 17 280 to 22 800 NTD (New Taiwan dollar; 8.80%), urbanization level of residence location with level 2 (9.06%), without other catastrophic illnesses or injuries (9.09%), a low severity of comorbidities (9.07%), without hepatitis B virus (9.02%), without hepatitis C virus (9.18%), with cirrhosis (8.94%), stage I liver cancer patients (9.43%), and those who received the treatment method of only operation (10.05%). Among the patients who underwent adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment, the mean, median, minimum, and maximum number of days of treatment in the first year after diagnosis was 110, 84, 30, and 365 days, respectively. Subsequently, the χ2 test was employed to analyze whether the characteristics of the liver cancer patients who received Western medicine treatment differed from those who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment. The results show that according to the sex, age, monthly salary, urbanization level of residence location, other catastrophic illnesses or injuries, severity of comorbidity, whether or not the liver cancer patients had hepatitis B virus, whether or not the liver cancer patients had hepatitis C virus, whether or not the liver cancer patients had cirrhosis, cancer stage, and treatment methods, the differences between the 2 groups were nonsignificant (P > .05).

The Effect of Adjunctive Chinese Medicine Treatment on the Survival Rate of Liver Cancer Patients and Related Factors

After performing the PSM for the patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment and those who received Western medicine treatment, Cox proportional hazards models were employed to conduct an analysis, the results of which showed that the liver cancer patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment exhibited a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.68 compared with those who received Western medicine treatment (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.62-0.74; Table 2). Subsequently, all of the related variables were controlled, and the survival curves for both patient groups were plotted (Figure 2). The curves show that compared with those who received Western medicine treatment, the patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment exhibited higher 1-year (83% vs 72%), 3-year (53% vs 44%), and 5-year (40% vs 31%) survival rates.

Table 2.

Effect of Adjunctive Chinese Medicine Treatment on the Survival Rate of Liver Cancer Patients and Related Factors.

| Variables | Survival |

Death |

P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||||

| Total number | 4930 | 33.47 | 9799 | 66.53 | ||||

| Treatment | <.001 | |||||||

| Western medicine (ref) | 4403 | 32.88 | 8987 | 67.12 | ||||

| Adjunctive Chinese medicine | 527 | 39.36 | 812 | 60.64 | 0.68 | 0.62-0.74 | <.001 | |

| Gender | <.001 | |||||||

| Male (ref) | 3523 | 33.00 | 7152 | 67.00 | ||||

| Female | 1407 | 34.71 | 2647 | 65.29 | 1.00 | 0.96-1.05 | .937 | |

| Age | <.001 | |||||||

| ≤40 (ref) | 287 | 36.61 | 497 | 63.39 | ||||

| 41-50 | 655 | 33.62 | 1293 | 66.38 | 1.08 | 0.97-1.20 | .142 | |

| 51-60 | 1481 | 36.94 | 2528 | 63.06 | 1.09 | 0.98-1.20 | .102 | |

| ≥61 | 2507 | 31.38 | 5481 | 68.62 | 1.25 | 1.13-1.37 | <.001 | |

| Average age (mean ± SD) | 60.51 ± 12.14 | 62.32 ± 12.79 | <.001 | |||||

| Monthly salary (NTD) | <.001 | |||||||

| Low-income household (ref) | 30 | 35.29 | 55 | 64.71 | ||||

| ≤17 280 | 208 | 32.30 | 436 | 67.70 | 0.94 | 0.71-1.25 | .677 | |

| 17 280-22 800 | 2311 | 29.64 | 5486 | 70.36 | 0.96 | 0.73-1.25 | .754 | |

| 22 801-28 800 | 735 | 36.77 | 1264 | 63.23 | 0.91 | 0.69-1.19 | .475 | |

| 28 801-36 300 | 426 | 37.83 | 700 | 62.17 | 0.87 | 0.66-1.14 | .301 | |

| 36 301-45 800 | 560 | 38.83 | 882 | 61.17 | 0.82 | 0.63-1.08 | .161 | |

| 45 801-57 800 | 237 | 39.24 | 367 | 60.76 | 0.83 | 0.62-1.10 | .188 | |

| ≥57 801 | 423 | 40.99 | 609 | 59.01 | 0.75 | 0.57-0.99 | .045 | |

| Urbanization level of residence location | <.001 | |||||||

| Level 1 (ref) | 1406 | 36.07 | 2492 | 63.93 | ||||

| Level 2 | 1548 | 35.24 | 2845 | 64.76 | 0.97 | 0.92-1.03 | .287 | |

| Level 3 | 669 | 31.10 | 1482 | 68.90 | 1.11 | 1.04-1.19 | .001 | |

| Level 4 | 751 | 31.23 | 1654 | 68.77 | 1.01 | 0.94-1.07 | .870 | |

| Level 5 | 120 | 32.35 | 251 | 67.65 | 1.02 | 0.89-1.16 | .801 | |

| Level 6 | 257 | 26.94 | 697 | 73.06 | 1.12 | 1.03-1.22 | .012 | |

| Level 7 | 179 | 32.14 | 378 | 67.86 | 1.02 | 0.92-1.14 | .685 | |

| Other catastrophic illnesses or injuries | <.001 | |||||||

| No (ref) | 4693 | 33.87 | 9162 | 66.13 | ||||

| Yes | 237 | 27.12 | 637 | 72.88 | 1.30 | 1.20-1.41 | <.001 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | <.001 | |||||||

| ≤3 (ref) | 4476 | 34.30 | 8574 | 65.70 | ||||

| 4-6 | 362 | 28.06 | 928 | 71.94 | 1.16 | 1.08-1.24 | <.001 | |

| ≥7 | 92 | 23.65 | 297 | 76.35 | 1.28 | 1.14-1.44 | <.001 | |

| Hepatitis B virus | .086 | |||||||

| No (ref) | 2500 | 33.22 | 5025 | 66.78 | ||||

| Yes | 2430 | 33.73 | 4774 | 66.27 | 0.95 | 0.91-1.00 | .033 | |

| Hepatitis C virus | <.001 | |||||||

| No (ref) | 3106 | 33.41 | 6190 | 66.59 | ||||

| Yes | 1824 | 33.57 | 3609 | 66.43 | 0.89 | 0.85-0.94 | <.001 | |

| Cirrhosis | <.001 | |||||||

| No (ref) | 1901 | 45.27 | 2298 | 54.73 | ||||

| Yes | 3029 | 28.77 | 7501 | 71.23 | 1.56 | 1.48-1.63 | <.001 | |

| Cancer stage | <.001 | |||||||

| Stage I (ref) | 3136 | 49.39 | 3214 | 50.61 | ||||

| Stage II | 1292 | 32.87 | 2639 | 67.13 | 1.40 | 1.32-1.47 | <.001 | |

| Stage III | 502 | 11.29 | 3946 | 88.71 | 3.42 | 3.25-3.59 | <.001 | |

| Treatment methods | <.001 | |||||||

| OP + CH + TACE (ref) | 886 | 29.22 | 2146 | 70.78 | ||||

| OP | 1809 | 46.14 | 2112 | 53.86 | 0.90 | 0.84-0.96 | .001 | |

| OP + CH + RT + TACE | 341 | 17.71 | 1585 | 82.29 | 1.30 | 1.22-1.39 | <.001 | |

| OP + RT | 549 | 38.85 | 864 | 61.15 | 1.08 | 0.99-1.17 | .082 | |

| OP + TACE | 339 | 29.12 | 825 | 70.88 | 0.94 | 0.86-1.02 | .109 | |

| OP + CH | 289 | 25.80 | 831 | 74.20 | 1.33 | 1.23-1.45 | <.001 | |

| OP + RFA | 479 | 59.95 | 320 | 40.05 | 0.61 | 0.54-0.69 | <.001 | |

| OP + CH + RT | 105 | 12.90 | 709 | 87.10 | 1.83 | 1.68-2.00 | <.001 | |

| OP + CH + TACE | 133 | 24.63 | 407 | 75.37 | 1.11 | 1.00-1.23 | .061 | |

| Level of hospital | <.001 | |||||||

| Medical center (ref) | 3289 | 34.70 | 6190 | 65.30 | ||||

| Regional hospital | 1091 | 31.05 | 2423 | 68.95 | 1.13 | 1.07-1.19 | <.001 | |

| District hospital | 368 | 29.39 | 884 | 70.61 | 1.18 | 1.10-1.28 | <.001 | |

| Physician Clinics | 182 | 37.60 | 302 | 62.40 | 1.17 | 0.99-1.38 | .074 | |

| Ownership of hospital | <.001 | |||||||

| Public (ref) | 1712 | 35.58 | 3100 | 64.42 | ||||

| Nonpublic | 3218 | 32.45 | 6699 | 67.55 | 1.00 | 0.96-1.05 | .856 | |

| Service volume of hospitals | .185 | |||||||

| Low (ref) | 28 | 31.82 | 60 | 68.18 | ||||

| Median | 63 | 37.50 | 105 | 62.50 | 1.09 | 0.78-1.52 | .624 | |

| High | 4839 | 33.43 | 9634 | 66.57 | 1.11 | 0.83-1.48 | .490 | |

| Service volume of physician | .185 | |||||||

| Low (ref) | 62 | 24.51 | 191 | 75.49 | ||||

| Median | 162 | 28.98 | 397 | 71.02 | 0.87 | 0.73-1.04 | .135 | |

| High | 4706 | 33.81 | 9211 | 66.19 | 0.70 | 0.59-0.81 | <.001 | |

| Age of physician | <.001 | |||||||

| ≤40 (ref) | 1365 | 28.86 | 3365 | 71.14 | ||||

| 41-50 | 2278 | 34.56 | 4313 | 65.44 | 0.90 | 0.86-0.95 | <.001 | |

| 51-60 | 1120 | 36.95 | 1911 | 63.05 | 0.83 | 0.78-0.88 | <.001 | |

| ≥61 | 167 | 44.30 | 210 | 55.70 | 0.82 | 0.71-0.94 | .005 | |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NTD, New Taiwan dollar; OP, surgery; CH, chemotherapy; TACE, embolization; RT, radiography; RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Figure 2.

Survival curves of liver cancer patients were performed by the Cox proportional hazard model, in which 1 group received Western medicine treatment (n1 = 13 390) and another group received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment (n2 = 1339).

When stratified by cancer stage (Figure 3), significant differences were observed between the 2 groups (P < .05). The 5-year survival rate of patients with stage I liver cancer who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment (56%) was higher than that of those who received Western medicine treatment (48%). Similarly, the 5-year survival rate of the patients with stage II liver cancer patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment (41%) was higher than that of those who received Western medicine treatment (30%).

Figure 3.

Survival curves of liver cancer patients performed by the Cox proportional hazard model are displayed by cancer stage, in which one group received Western medicine treatment (n1 = 13 390) and another group received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment (n2 = 1339).

Related Factors Influencing Liver Cancer Patients Survival

Table 2 shows that the risk of death was equal between women and men (HR = 1.00; 95% CI = 0.96-1.05). Furthermore, the risk increased with age: liver cancer patients ≥61 years exhibited a significantly higher risk of death compared with those aged ≤40 years (HR = 1.25; 95% CI = 1.13-1.37). The risk of death of the patients with the highest monthly salaries was 0.75 times that of low-income earners (95% CI = 0.57-0.99). Regarding urbanization level of residence location, the risk of death of the patients who lived in the areas with lowest degree of urbanization was 1.02 times that of those living in the areas with the highest degree of urbanization (95% CI = 0.92-1.14). The patients with other catastrophic illnesses or injuries exhibited a risk of death that was significantly higher than those without other catastrophic illnesses or injuries (HR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.20-1.41). Regarding the health status of the liver cancer patients, the more severe their comorbidities were, the higher the risk of death became; those with a CCI of ≥7 exhibited 1.28 times risk of death compared with those with a CCI of ≤3 (95% CI = 1.14-1.44). Moreover, the risk of death of the liver cancer patients with hepatitis C virus did not increase compared with those without hepatitis C virus (HR = 0.89; 95% CI = 0.85-0.94), but the risk of death of patients with cirrhosis was significantly higher than those without cirrhosis (HR = 1.56; 95% CI = 1.48-1.63). And the risk also increased with cancer stage, with that of stage III liver cancer patients (HR = 3.42; 95% CI = 3.25-3.59) significantly exceeding that of the stage I liver cancer patients. Regarding the primary medical institution characteristics, the lower the level of the medical institution was, the greater the risk of death became; the risk of death among the patients who received treatment at district hospitals were significantly higher than that of those who were treated at medical centers (HR = 1.18; 95% CI = 1.10-1.28). Concerning the ownership of the medical institutions, the risk of death for patients who received treatment at private medical institutions was similar with those who were treated at public medical institutions (HR = 1.00; 95% CI = 0.96-1.05), and the risk of death for patients who received treatments at hospitals with a different service volume was not significantly different. Finally, regarding physician age, the patients who received treatment primarily from physicians aged ≥61 years exhibited the lowest risk of death (HR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.71-0.94).

Table 3 shows that for the patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment, the most frequently used traditional Chinese medicine regimen comprised 6 single-herb medicine and 4 herbal formulas. For single-herb medicines, the most frequently used medicines were bai hua she she cao (24.9%), ban zhi lian (12.1%), dan shen (10.8%), yin chen hao (6.9%), bie jia (6.5%), and ye jiao teng (5.6%); for herbal formulas, the 4 most frequently used formulas were jia wei xiao yao san (11.3%), xiao chai hu tang (10.9%), xiang sha liu jun zi tang (8.3%), and yin chen wu ling san (6.2%).

Table 3.

Top 10 Traditional Chinese Medicine Used by Patients Who Received Adjunctive Chinese Medicine Treatment.

| Name of Traditional Chinese Medicine | Ingredient | % |

|---|---|---|

| Bai Hua She She Cao | Hedyotis diffusa | 24.9 |

| Ban Zhi Lian | Scutellaria barbata | 12.1 |

| Jia Wei Xiao Yao San | Angelica sinensis, Poria, Gardenia jasminoides, Menthae, Paeonia lactiflora, Bupleurum chinense DC, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Atractylodes macrocephala, Moutan Radicis Cortex, Ginger | 11.3 |

| Xiao Chai Hu Tang | Bupleurum chinense DC, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Talinum, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Pinellia ternata, Ginger, Ziziphus jujuba | 10.9 |

| Dan Shen | Salvia miltiorrhiza Bge | 10.8 |

| Xiang Sha Liu Jun Zi Tang | Rosa banksiae, Fructus amomi, Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae, Pinellia ternata, Codonopsis pilosula, Poria, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Ginger, Ziziphus jujuba | 8.3 |

| Yin Chen Hao | Artemisia capillaris | 6.9 |

| Bie Jia | Carapax trionycis | 6.5 |

| Yin Chen Wu Ling San | Artemisia capillaris, Alisma plantago-aquatica, Atractylodes macrocephala, Poria, Polyporus umbellatus, Ramulus cinnamomi | 6.2 |

| Ye Jiao Teng | Polygonum multiflorum Thunb | 5.6 |

Discussion

In this study, PSM was adopted to reduce selection bias, the results of which show that when all other related factors were controlled, the risk of death for the patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment was significantly lower than that of those who received Western medicine treatment (HR = 0.68). This indicates that adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment can improve the survival rate of patients with liver cancer, which supports the findings of previous studies investigating the effectiveness of adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment on improving the survival rate of patients with different types of cancer (ie, liver, lung, breast, and head and neck cancer)5,16,22-24; however, in these studies, the patients were not stratified according to their cancer stage. Some studies have shown that combining Chinese medicine treatment with chemotherapy can significantly extend the survival period of patients with late-stage lung or colon cancer.25,26 Meta-analyses have confirmed that compared with Western medicine treatment, adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment is more effective in elevating the survival period of patients with mid- to late-stage liver or lung cancer.27,28 Cancer patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment exhibited increased suppression of cancer cells, which lowers the risk of death. In addition, Chinese medicine treatment eases the adverse reactions that patients experience during chemotherapy and radiation therapy.5,26 Therefore, when patients with cancer elect to receive adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment, their clinical symptoms and quality of life can be improved and their survival can be extended.24,26 The 10 traditional Chinese medicines used by the liver cancer patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment in the present study are similar to those reported in previous studies, indicating that the most common traditional Chinese medicines used by patients with liver cancer are jia wei xiao yao san, xiao chai hu tang, and xiang sha liu jun zi tang.29 Other studies have indicated that jia wei xiao yao san, bai hua she she cao, ban zhi lian, and dan shen are traditional Chinese medicines that are commonly used to treat breast cancer.16 Because no study has explored the effectiveness of adjunctive Chinese medicine for treating stage I to III liver cancer,29,30 this study addressed this research gap and found that adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment exhibited more favorable treatment results on stage I and II liver cancer than on stage III liver cancer. This may be attributable to patients with stage I or II cancer having milder conditions that were easier to treat.

The results of this study support those reported by previous studies that have shown that the risk of death was lower for women than for men,6,7,31,32 higher for older age groups and patients with a lower socioeconomic status,6-8,10,11,33-35 higher with increasing severity of comorbidities,36,37 and higher at later cancer stages.12,35,38,39 In the present study, the risk of death increased with age; lower income; greater severity of comorbidities, catastrophic illnesses or injuries; and at later cancer stages. The results of previous studies have showed that the patients having hepatitis C virus may increase the risk of developing liver cancer.40,41 This study adopted the PSM that included the variable of hepatitis C; since all patients have developed a liver cancer, the mortality risk of patients with liver cancer having hepatitis C was not significant.

For the patients who were treated at hospitals, the outcome of their treatment might have differed because of differences in the treatment provided by the hospitals due to different hospital characteristics. The results of this study were supported by previous studies and indicated that the postsurgery mortality rate of patients with a liver cancer is significantly lower in medical centers than nonmedical centers (including regional, district hospitals, and physician clinics).42 Regarding ownership of hospitals, nonpublic hospitals (including private hospitals) showed a higher mortality rate than that of public hospitals,42 but this study did not indicate the same outcome. The present study shows that the risk of death for patients with liver cancer increased significantly when treatment was received through lower level medical institutions, nonpublic institutions, and physicians with low service volumes, which accords with the results of previous studies.43-45 Health behavior and lifestyle, which include smoking, drinking alcohol, exercise, and diet, may affect the survival of cancer patients. Previous studies have indicated that the risk of death was higher for cancer patients who have the habit of smoking and drinking alcohol.46,47 In contrast, cancer patients who perform regular exercise and take a nutritional diet may have improved survival.48,49 Although we could not include these health behaviors and lifestyle factors in the analysis model, we believe that these factors might have similar impacts on these 2 groups of patients.

Research Limitations

This study was not a randomized clinical trial and used medical claim data compiled by the NHI Administration for analysis. The survival curves (Figure 3) indicated that there was a significant association between the patients receiving adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment and the patients having better survival rate, but a cause and effect relationship could not be determined from these data. In addition, patients might have self-selected for medical treatment, leading to bias in the study. Although the NHI covers the most portion of the cost of both traditional Chinese and Western medical regimens, some patients may be required to pay for traditional Chinese medicines not covered by the NHI. Consequently, it remains unclear how such medical expenses incurred may have resulted in a possible underestimation of the number of patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment. In addition, the study was unable to determine whether the number of liver cancer patient deaths from the data reflects the actual number of deaths from liver cancer because the patients could have died from other causes. Finally, the external validity of this study results for other countries with different health care delivery systems is limited.

Conclusions

After PSM was applied to reduce selection bias, the study results revealed that compared with those who received only Western medicine treatment, patients who received adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment exhibited a lower risk of death and increased survival rates. Related factors influencing the survival rate of liver cancer patients included demographic characteristics (ie, sex, age), income, area of residence, cancer stage, health status (ie, severity of comorbidities), catastrophic illness or injury status, cirrhosis, treatment methods, primary medical institution characteristics (ie, hospital level and ownership structure), and primary physician characteristics (ie, age). In addition, the effects of adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment on liver cancer patients differed among the patients according to cancer stage, in which the survival rate of the patients with stage I or II cancer was higher than that of patients with stage III or IV cancer.

According to the results of this study, we recommend that government or physicians should further conduct focused preclinical studies as well as well-designed and controlled prospective clinical trials. Future studies should consider investigating the underlying mechanisms of the medicines used in adjunctive Chinese medicine treatment to determine which type of traditional Chinese medicine or treatment is the most effective for improving the survival rate of patients with liver cancer.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the use of the National Health Insurance Research Database and the Cancer Register Files provided by Statistic Center of Ministry of Health and Welfare. We are also grateful to Health Data Science Center, China Medical University Hospital, for providing administrative, technical and funding support.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Grant ASIA107-CMUH-15 from Asia University and China Medical University. We are also grateful to Health Data Science Center, China Medical University Hospital, for providing administrative, technical, and funding support.

ORCID iD: Wen-Chen Tsai  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9684-0789

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9684-0789

References

- 1. World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN 2012: estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx. Accessed June 6, 2015.

- 2. Health Promotion Administration ROC. Taiwan Cancer Registry Report in 2011. http://www.hpa.gov.tw/BHPNet/Web/Stat/StatisticsShow.aspx?No=201404160001. Accessed June 6, 2015.

- 3. Liao YH, Lin CC, Li TC, Lin JG. Utilization pattern of traditional Chinese medicine for liver cancer patients in Taiwan. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu W, Towers AD, Li P, Collet JP. Traditional Chinese medicine in cancer care: perspectives and experiences of patients and professionals in China. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2006;15:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin G, Li Y, Chen S, Jiang H. Integrated Chinese-western therapy versus western therapy alone on survival rate in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer at middle-late stage. J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;33:433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Artinyan A, Mailey B, Sanchez-Luege N, et al. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status influence the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:1367-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P, Johnson JA. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin: response to Farooki and Schneider. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1990-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jembere N, Campitelli MA, Sherman M, et al. Influence of socioeconomic status on survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Ontario population; a population-based study, 1990-2009. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Serag HB, Siegel AB, Davila JA, et al. Treatment and outcomes of treating of hepatocellular carcinoma among Medicare recipients in the United States: a population-based study. J Hepatol. 2006;44:158-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kemmer N, Neff G, Secic M, Zacharias V, Kaiser T, Buell J. Ethnic differences in hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:551-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwong SL, Stewart SL, Aoki CA, Chen MS., Jr. Disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma survival among Californians of Asian ancestry, 1988 to 2007. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2747-2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Minagawa M, Ikai I, Matsuyama Y, Yamaoka Y, Makuuchi M. Staging of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of the Japanese TNM and AJCC/UICC TNM systems in a cohort of 13,772 patients in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:909-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaudhry R, Goel V, Sawka C. Breast cancer survival by teaching status of the initial treating hospital. CMAJ. 2001;164:183-188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang YH, Kung PT, Tsai WC, Tai CJ, Liu SA, Tsai MH. Effects of multidisciplinary care on the survival of patients with oral cavity cancer in Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:803-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee YW, Chen TL, Shih YR, et al. Adjunctive traditional Chinese medicine therapy improves survival in patients with advanced breast cancer: a population-based study. Cancer. 2014;120:1338-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health Promotion Administration. Taiwan Cancer Registry Coding Manual. Long Form in 2011. http://tcr.cph.ntu.edu.tw/uploadimages/Longform%20Manual_Official%20version_20171204_W.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 18. Central Health Insurance Department of the Ministry of Health and Welfare. The National Health Insurance Statistics in 2013. http://www.nhi.gov.tw/Resource/webdata/28507_1_%E5%85%A8%E6%B0%91%E5%81%A5%E5%BA%B7%E4%BF%9D%E9%9A%AA%E7%B5%B1%E8%A8%88%E5%8B%95%E5%90%91-2013%E5%B9%B4.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2015.

- 19. Parsons LS. Performing a 1: N case-control match on propensity score. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 29th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference; 2004; Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Cancer Society. Liver cancer stages. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/livercancer/detailedguide/liver-cancer-staging. Published 2015. Accessed June 6, 2015.

- 21. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lin HC, Lin CL, Huang WY, et al. The use of adjunctive traditional Chinese medicine therapy and survival outcome in patients with head and neck cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study. QJM. 2015;108:959-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang Y, Wu Y, Yao C. Exploration on TCM clinical study on non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med. 2003;23:147-149. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen S, Flower A, Ritchie A, et al. Oral Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) as an adjuvant treatment during chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu ZY, Jin CJ, Zhou CC, et al. Treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with Chinese herbal medicine by stages combined with chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1117-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou LY, Shan ZZ, You JL. Clinical observation on treatment of colonic cancer with combined treatment of chemotherapy and Chinese herbal medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2009;15:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shu X, McCulloch M, Xiao H, Broffman M, Gao J. Chinese herbal medicine and chemotherapy in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:219-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang S, Cui M, Li HY, Zhao YK, Gao YH, Zhu HY. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of Chinese and Western integrative medicine on medium and advanced lung cancer. Chin J Integr Med. 2012;18:862-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liao YH, Lin CC, Lai HC, Chiang JH, Lin JG, Li TC. Adjunctive traditional Chinese medicine therapy improves survival of liver cancer patients. Liver Int. 2015;35:2595-2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsai FJ, Liu X, Chen CJ, et al. Chinese herbal medicine therapy and the risk of overall mortality for patients with liver cancer who underwent surgical resection in Taiwan. Complement Ther Med. 2019;47:102213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cook MB, McGlynn KA, Devesa SS, Freedman ND, Anderson WF. Sex disparities in cancer mortality and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1629-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang D, Hanna DL, Usher J, et al. Impact of sex on the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Cancer. 2014;120:3707-3716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, Louwman MW, Maas HA, Coebergh JW. Prognostic impact of increasing age and co-morbidity in cancer patients: a population-based approach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:231-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim WR, Gores GJ, Benson JT, Therneau TM, Melton LJ., 3rd Mortality and hospital utilization for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:486-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu LB, Wang J, Liu C, et al. Staging systems for predicting survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5257-5262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee SH, Choi HC, Jeong SH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in older adults: clinical features, treatments, and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:241-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shau WY, Shao YY, Yeh YC, et al. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality in patients receiving curative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2012;17:856-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gomaa AI, Hashim MS, Waked I. Comparing staging systems for predicting prognosis and survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Toyoda H, Kumada T, Kiriyama S, et al. Changes in the characteristics and survival rate of hepatocellular carcinoma from 1976 to 2000: analysis of 1365 patients in a single institution in Japan. Cancer. 2004;100:2415-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saito I, Miyamura T, Ohbayashi A, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6547-6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Hepatitis Viruses. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Siemerink EJ, Schaapveld M, Plukker JT, Mulder NH, Hospers GA. Effect of hospital characteristics on outcome of patients with gastric cancer: a population based study in north-east Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen TM, Chang TM, Huang PT, et al. Management and patient survival in hepatocellular carcinoma: does the physician’s level of experience matter? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(7 pt 2):e179-e188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuo RN, Chung KP, Lai MS. Re-examining the significance of surgical volume to breast cancer survival and recurrence versus process quality of care in Taiwan. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:26-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin HC, Lin CC. Surgeon volume is predictive of 5-year survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: a population-based study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2284-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shih WL, Chang HC, Liaw YF, et al. Influences of tobacco and alcohol use on hepatocellular carcinoma survival. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2612-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chiang CH, Lu CW, Han HC, et al. The relationship of diabetes and smoking status to hepatocellular carcinoma mortality. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, Yun YH. Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5017-5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Irwin ML, Mayne ST. Impact of nutrition and exercise on cancer survival. Cancer J. 2008;14:435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]