Abstract

Background

Buprenorphine is an effective pharmacotherapy for the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD), but recent increases in the rate of OUD in the U.S. have outpaced the supply of clinicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. To increase the supply of buprenorphine prescribers, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act expanded buprenorphine prescribing waiver eligibility beyond physicians to nurse practitioners (NP) and physician assistants (PA) in 2017. Little is known about patterns of waiver uptake among NPs and PAs. This study examined associations between the existing supply of waivered prescribers and waiver uptake among NPs and PAs in U.S. states.

Methods

NP and PA waiver uptake was evaluated as the number of NPs or PAs obtaining an initial buprenorphine prescribing waiver per 10,000 state residents from January 2017 to December 2018 using data from the Buprenorphine Waiver Notification System. NP and PA waiver uptake was estimated as a function of existing waivered prescriber supply, OUD treatment capacity, and other state characteristics using generalized least squares (GLS) regression.

Results

28,010 NPs and PAs have become waivered to prescribe buprenorphine since January, 2017. GLS regressions indicated that waivered prescriber supply was significantly, positively associated with both NP (b = 0.101 p<0.001) and PA (b = 0.030, p<0.001) waiver uptake.

Results suggest an addition of ten waivered prescribers to existing supply was associated with an increase of one waivered NP, and an addition of thirty-three waivered prescribers to existing supply was associated with an increase of one waivered PA.

Conclusions

NP and PA waiver uptake is strongly associated with the existing supply of waivered prescribers in a state, suggesting NPs and PAs may be more likely to acquire waivers in states with a high existing supply of buprenorphine prescribers. Additional policy solutions are needed to scale up the supply of buprenorphine prescribers in underserved states.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, treatment capacity, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, opioid use disorder

1. Introduction

The consequences of the opioid epidemic have been profound in the United States. In 2018, an estimated two million people had opioid use disorder (OUD) and 10.3 million people misused opioids (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Moreover, from 2008 to 2018, the rate of fatal opioid overdose increased more than 130% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). The growing magnitude of the opioid epidemic has prompted efforts to expand treatment capacity for OUD (Kolodny et al., 2015). Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is the recommended treatment for OUD, and its use markedly decreases risk of incident opioid-related disease (Sullivan et al., 2008), overdose (Bell et al., 2009), and death (Connery, 2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

Historically, MOUD could only be accessed at licensed addiction treatment programs, making access difficult for many who sought treatment (Beetham et al., 2019; Kelsey & Gertner, 2019). Since 2002, physicians meeting certain requirements have also been able to prescribe buprenorphine in a primary care office-based setting (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2006). This expansion of prescribing authority led to an increase in the number of physician prescribers and a concomitant increase in the availability of office-based OUD treatment (Kolodny et al., 2015). However, over the last decade increasing patient interest in office-based MOUD has continued to outpace growth in treatment capacity (Huhn & Dunn, 2016; Jones et al., 2015).

In 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) made a second attempt to scale-up treatment capacity by expanding buprenorphine prescribing authority beyond physicians to nurse practitioners (NP) and physician assistants (PA). NPs and PAs occupy critical roles in comprehensive OUD treatment and are able to perform similar tasks to primary care physicians (LaBelle et al., 2016). In this role, NPs and PAs can offer buprenorphine to OUD patients in areas where physicians are not offering care. NPs and PAs became eligible to acquire prescribing waivers in January 2017. To acquire prescribing waivers, NPs and PAs must complete 24 hours of training on buprenorphine prescribing and submit applications for prescribing privileges to the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (Fornili & Fogger, 2017). NPs and PAs have an automatic patient maximum of 30 patients in the first year of prescribing, but can apply for an increase to a 100-patient maximum after one year. As of 2020, NPs and PAs have been able to acquire waivers for over three years.

A growing body of research has examined characteristics of NPs’ and PAs’ buprenorphine waiver uptake. Research projected that waiver expansion to NPs and PAs would increase treatment capacity by 15% in rural areas (Andrilla et al., 2018). An assessment of the geographic distribution of newly waivered prescribers found that at the end of 2017, national waivered prescriber supply increased, but disparities persisted between rural and urban areas post-waiver expansion (Andrilla et al., 2019). Only 1.6% of newly waivered NPs and PAs were located in counties without an existing supply of waivered physicians (Andrilla et al., 2019). In a more recent evaluation of waiver uptake in rural counties from 2016 to 2019, Barnett et al. found that the supply of waivered prescribers increased by 111% (Barnett et al., 2019). Research found that NPs’ and PAs’ waiver uptake was responsible for more than 50% of this increase in rural counties (Barnett et al., 2019). Despite increases in waivered prescriber supply in rural areas, disparities in treatment capacity are still apparent.

The influence of state scope-of-practice regulations on waiver uptake has also received attention in recent research. Scope-of-practice regulations indicate the degree to which NPs and PAs can practice autonomously from physician supervision. A study examining the association between state scope-of-practice regulations and buprenorphine waiver uptake among NPs and PAs found regulations had no association with the proportion of waivered PAs, but restricted prescriptive authority was associated with a lower proportion of waivered NPs after adjustment for the proportion of waivered physicians (Spetz et al., 2019). Spetz et al. suggest this result may be due to the inherently restricted practice of PAs, who require physician oversight in all states, in comparison to NPs, who can work without physician oversight in many states. While the association between the proportion of waivered physicians and the proportion of waivered NPs and PAs is significant, the magnitude of the relationship is not reported. Barnett et al. found similar trends in NP and PA waiver uptake in rural counties, but evaluated NP scope-of-practice as either full (i.e., autonomous prescriptive and practice authority) or restricted (i.e., oversight required for either prescriptive or practice authority). However, Barnett et al. categorized state scope-of-practice regulations according to laws in 2016, which may not reflect changes to regulations in later years. In combination, these works suggest that state characteristics may influence waiver uptake, but the direction and magnitude of the relationship is unclear.

While no other research has assessed the influence of state characteristics on waiver uptake among NPs and PAs, a larger body of research has evaluated physician waiver uptake. Overdose rate, opioid prescribing rate, and Medicaid funding are consistently associated with a higher supply of waivered physicians at the state level (Knudsen et al., 2017; Stein et al., 2015; Wen et al., 2018). Additionally, growth in waivered physicians supply tends to be greatest in states with high OUD treatment capacity and high overdose rates (Knudsen, 2015; Knudsen et al., 2017). Physician waiver uptake appears to be reflective of both the perceived need for MOUD and existing capacity to treat OUD in a state, but we do not know if these patterns of uptake persist among NPs and PAs.

CARA intended to scale up OUD treatment capacity in underserved areas, but we do not know if the waiver expansion to NPs and PAs decreased treatment capacity disparities between states. Evaluating the influence of state characteristics on waiver uptake is critical to understanding the impact of policies that seek to expand treatment capacity. This study examined the association between state characteristics and waiver uptake among NPs and PAs from 2016 to 2018 using publicly available data. We hypothesized that while CARA intended to reduce MOUD treatment capacity disparities between states, states with an existing high supply of waivered prescribers would experience higher waiver uptake among NPs and PAs than states with a lower supply.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and data sources

This study used several publicly available data sources. We obtained data from the Centers for Disease Control ([dataset] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration ([dataset] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018a), the United States Census Bureau ([dataset] United States Census Bureau, 2019), the Department of Health Resources and Service Administration ([dataset] U.S. Department of Health Resources and Service Administration, 2019), the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services ([dataset] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018), and the Scope of Practice Policy ([dataset] Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, 2018). While survey data were collected and published at different points in time, all covariates preceeded measurement of the dependent variable. We merged datasets by state federal information processing codes and year.

2.2. Outcome and primary independent variables

Outcomes variables were per capita NP and PA initial waiver uptake in 2017 and 2018, which were evaluated as the proportion of newly waivered NPs and PAs to state population per 10,000 residents. Only NPs and PAs obtaining 30-patient maximum waivers were included in initial waiver uptake, as only previously waivered NPs and PAs are eligible for 100-patient maximum waivers. We obtained data on the number of waivered prescribers per state, per year from June 2002 to December 2018 by degree type (NP, PA, and MD) from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration Waiver Notification System using a Freedom of Information Act request ([dataset] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018a). State population estimates were obtained from the United States Census Bureau, and these estimates were used for all per capita measures ([dataset] United States Census Bureau, 2019).

The primary independent variable was waivered prescriber supply in 2016 and 2017, which was evaluated as the sum of waivered physicians, NPs, and PAs to state population per 10,000 residents. In 2017, waivered prescriber supply is defined as the sum of all waivered physicians from 2002 to 2016. In 2018, waivered prescriber supply is the sum of all waivered physicians, NPs, and PAs from 2002 to 2017. NP and PA waiver uptake and waivered prescriber supply are mutually exclusive; a prescriber is considered newly waivered for only the year the waiver is acquired, and is considered part of waivered prescriber supply in the following year.

2.3. Covariates

We obtained state-level physician counts, NP counts, PA counts, percent of uninsured adults, and rurality from the Area Health Resource File ([dataset] U.S. Department of Health Resources and Service Administration, 2019). We estimated supply of clinicians (NP, PA, and MD) as the proportion of clinicians by degree type to state population per 10,000 residents. Rurality was evaluated as the proportion of state residents who reside in a rural area. Data in the Area Health Resource File are collected at various intervals, and we used the most recent available data.

We measured state OUD treatment supply using data from the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services ([dataset] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018b). The National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services is conducted annually and assesses availability of substance abuse services at the state level. From this survey, we obtained data from 2016 to 2018 on the number of outpatient opioid treatment programs (OTP) offering only methadone, the number of outpatient OTPs offering both buprenorphine and methadone, and the number of non-OTP facilities offering buprenorphine. We also obtained data on the number of facilities offering any MOUD with inpatient, intensive outpatient, and outpatient care ([dataset] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018b). We evaluated supply of substance use disorder treatment facilities as the proportion of facilities to state population per 10,000 residents by facility type.

We obtained data on Medicaid enrollment and Medicaid expansion status from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services from 2016 to 2018 ([dataset] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018). We calculated the percent of adults enrolled in Medicaid as the proportion of adults enrolled in Medicaid to state population. Medicaid expansion status was evaluated as a binary variable, and states were categorized as either having expanded Medicaid or not.

Data on opioid overdose deaths were obtained from the Multiple Cause of Death data available from the Centers for Disease Control WONDER database from 2015 to 2017 ([dataset] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Opioid overdose deaths were identified using cause of death codes T40.1 (heroin), T40.2 (other opioids), T40.3 (methadone), T40.4 (other synthetic narcotics), and T40.6 (other and unspecified narcotics). Opioid overdose rates were calculated as the proportion of overdose deaths to state population per 100,000 residents. We negatively lagged rate of opioid overdose by one year as we believed it may have a delayed impact on waiver uptake due to reporting delays, which modeling supported (see appendix).

State-specific data on NP scope of practice were obtained from review of the annual Advanced Practice Nurse Practitioner Legislative Update (Phillips, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019) and confirmed through review of state legislation per the Scope of Practice Policy ([dataset] Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, 2018). The Scope of Practice Policy is generated by the National Conference of State Legislatures and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials to educate policymakers on state laws related to practice autonomy for a variety of healthcare professionals, including NPs and PAs. We evaluated NP practice autonomy as a binary variable, and defined as either permitting prescriptive authority of at least schedule III substances without physician oversight or not. States that permit NP prescriptive authority after a period of temporary oversight after licensure were considered to allow autonomous practice. State data on PA scope of practice were obtained from Barton Associates, who provide an annual review of state legislation regarding elements of PA practice, and confirmed through review of Scope of Practice Policy ([dataset] Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, 2018; [dataset] Barton Associates, 2019). We considered PA practice autonomous if scope of practice was defined at the practice level and had at least five of the six key elements of modern PA practice per prior research and recommendations by the American Association of Physician Assistants (American Association of Physician Assistants, 2016; Barnett et al., 2019; Spetz et al., 2019). We also evaluated PA practice autonomy as a binary variable.

2.2. Statistical analyses

We assessed differences in waivered prescriber supply, OUD treatment facilities, and other state characteristics pre- (2016) and post- (2018) waiver expansion using t-tests for continuous measures and Chi-square tests for nominal measures with a significance level of 0.05. To assess unadjusted changes in waivered prescriber supply, we categorized states into tertiles of waivered prescriber supply (i.e. low, medium, high) pre-waiver expansion. We then compared supply pre- to post-waiver expansion within each tertile using t-tests.

We performed generalized least squares (GLS) random-effect linear regressions to examine the association between state characteristics and waiver uptake. We conducted Hausman tests to determine if random- or fixed-effects were appropriate for modeling, which indicated that random-effects were efficient for both NP (p = 0.08) and PA (p = 0.09) modeling of waiver uptake. Random effect models leverage both within- and between-panel variation to estimate the effect of variables on outcomes. To account for correlation among errors, we used robust standard errors in all models. We performed unadjusted models, examining the associations between covariates and waiver uptake, followed by multivariable regression models to estimate NP and PA waiver uptake as a function of state characteristics.

In addition to waivered prescriber supply, the primary independent variable, we included several measures of state-level OUD treatment capacity as covariates. We included outpatient OTPs offering only methadone per capita, outpatient OTPs offering methadone and buprenorphine per capita, non-OTP outpatient facilities offering buprenorphine per capita, and inpatient facilities offering any MOUD per capita. We also included measures of state healthcare characteristics. These covariates include rate of opioid overdose per capita, physicians per capita, NPs or PAs per capita, NP or PA practice autonomy, percent of uninsured adults, percent of adults enrolled in Medicaid, Medicaid expansion status, and rurality. We additionally included an interaction term between waivered prescriber supply and practice autonomy, given that waiver uptake may be higher in states that allow NPs and PAs greater scope-of-practice. We evaluated all variables continuously except practice autonomy and Medicaid expansion status, which we treated as binary variables.

We performed sensitivity analyses with alternative measures of waiver uptake and waivered prescriber supply, where the denominator was clinicians in a state by degree type instead of state population. State-year was the unit of analysis in all models. We conducted all analyses in Stata/SE 15.1.

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate results

Table 1 shows results of bivariate analyses. From 2016 to 2018, the average state supply of buprenorphine waivered prescribers increased from 0.75 to 1.41 waivered prescribers per 10,000 residents (p < 0.001). Additionally, all tertiles of waivered provider supply experienced significant increases in supply pre- to post-waiver expansion. The supply of treatment facilities offering MOUD did not significantly change pre- to post-waiver expansion. The percentage of adults enrolled in Medicaid did not significantly change (21.4% vs. 20.1%; p = 0.147), and there were no changes to states’ Medicaid expansion status pre- to post-waiver expansion. As of December 2016, prior to the waiver expansion to NPs and PAs, there were 29,686 waivered physician prescribers. One year after the waiver expansion, there were 39,892 total waivered prescribers. Of the 10,206 newly waivered prescribers, 25.7% (n = 2,626) were NPs and 6.4% (n = 656) were PAs. While the annual rate of waiver uptake increased 34.4% from the year prior, rates of uptake varied substantially between states. Additionally, the annual rate of waiver uptake decreased 5.5% (n = 6,924) among physicians.

Table 1.

State OUD treatment capacity per 10,000 residents pre- and post-buprenorphine waiver expansion.

| 2016: Pre-Waiver Expansion M (SD) | 2018: Post-Waiver Expansion M (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Waivered prescriber supply | 0.75 (0.53) | 1.41 (0.98) | <0.001*** |

| Quartiles of waivered prescriber supply: | |||

| 1st quartile | 0.34 (0.07) | 0.64 (0.14) | <0.001*** |

| 2nd quartile | 0.64 (0.12) | 1.22 (0.35) | <0.001*** |

| 3rd quartile | 1.32 (0.56) | 2.64 (1.04) | <0.001*** |

| All facilities offering any MOUD by care type: | |||

| Outpatient | 0.21 (0.11) | 0.22 (0.11) | 0.678 |

| Intensive outpatient | 0.20 (0.12) | 0.21 (0.10) | 0.716 |

| Inpatient | 0.20 (0.11) | 0.21 (0.10) | 0.794 |

| OTPs1 offering: | |||

| Only methadone | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.363 |

| Methadone and buprenorphine2 | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.619 |

| Non-OTP facilities offering buprenorphine | 0.13 (0.08) | 0.17 (0.10) | 0.058 |

OTP – opioid treatment program

Buprenorphine includes buprenorphine with and without naloxone

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

As of December 2018, there were 57,696 waivered prescribers. Of the 17,804 prescribers newly waivered in 2018, 32.5% (n = 5,792) were NPs and 8.5% (n = 1,507) were PAs. Of the waivers that NPs and PAs obtained in 2018, 22.3% (n = 1,294) and 24.4% (n = 368) were for waivers with patient maximums of 100. Among physicians, annual waiver uptake increased by 51.7% (n = 10,505) from 2017 to 2018. From 2017 to 2018, the rate of waiver uptake per year among all clinicians increased 44.6%, but rates of uptake varied between states.

3.2. NP waiver uptake multivariable results

Table 2 shows results from a series of unadjusted and adjusted GLS models of NP waiver uptake. In the former, the relationship between waivered prescriber supply per capita, the primary independent variable, and NP waiver uptake per capita was significant (β = 0.120, SE = 0.011). Unadjusted models also found that states with more per capita OTPs offering buprenorphine and methadone (β = 1.959, SE = 0.325), OTPs offering only methadone (β = 3.738, SE = 0.881), non-OTP facilities offering buprenorphine (β = 0.102, SE =

Table 2.

GLS regression models of state level waiver uptake among nurse practitioners.

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted Multivariable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | SE | β | SE |

|

| ||||

| OUD Treatment Characteristics | ||||

| Waivered prescriber supply | 0.120*** | 0.011 | 0.101*** | 0.016 |

| Opioid overdose rate | 0.007*** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| OTPs with methadone and buprenorphine | 1.959*** | 0.325 | −0.171 | 0.284 |

| OTPs with methadone | 3.738*** | 0.881 | 0.348 | 0.571 |

| Non-OTPs with buprenorphine | 0.102*** | 0.010 | 0.732* | 0.287 |

| Inpatient facilities with any MOUD | 0.923*** | 0.108 | −0.323 | 0.244 |

| Healthcare Characteristics | ||||

| Waivered prescriber supply x practice autonomy | 0 114*** | 0.011 | −0.002 | 0.014 |

| NP practice autonomy | 0.138*** | 0.021 | 0.051** | 0.018 |

| Physicians per capita | 0.002*** | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 |

| Nurse practitioners per capita | 0.002** | 0.001 | 0.001* | 0.0001 |

| Medicaid expansion status | 0.091*** | 0.024 | 0.104*** | 0.023 |

| Percent of residents on Medicaid | 0.493* | 0.240 | −0.568** | 0.213 |

| Percent of residents uninsured | −1.347** | 0.397 | 1.101** | 0.294 |

| Proportion rural | 0.150 | 0.114 | −0.006 | 0.079 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

0.010), and inpatient facilities offering any MOUD (β = 0.923, SE = 0.108) were associated with significantly higher waiver uptake among NPs. Higher rate of opioid overdose (β = 0.007, SE = 0.001) was also associated with greater uptake in unadjusted models. Additionally, the interaction between waivered prescriber supply and NP practice autonomy was positively associated with waiver uptake (β = 0.114, SE = 0.011). Physicians per capita, NPs per capita, NP practice autonomy, Medicaid expansion, and percent of residents on Medicaid were also associated with higher waiver uptake. Conversely, percent of uninsured residents was associated with lower waiver uptake among NPs. Only rurality was not associated with NP waiver uptake in unadjusted models.

In multivariable regression, NP waiver uptake was significantly, positively associated with waivered prescriber supply (β = 0.101, SE = 0.016). NP waiver uptake was also positively associated with non-OTP facilities offering buprenorphine (β = 0.732, SE = 0.287), practice autonomy (β = 0.051, SE = 0.018), Medicaid expansion (β = 0.104, SE = 0.023), and percent of uninsured residents (β = 1.101, SE = 0.294). Percent of residents on Medicaid (β = −0.568, SE = 0.213) was negatively associated with NP waiver uptake. No other variables, including the interaction between prescriber supply and practice autonomy, were associated with NP waiver uptake after adjustment. These results suggest an addition of ten waivered prescribers to existing supply is associated with an increase of one waivered NP. The results of our sensitivity analyses were consistent with our main results.

3.3. PA waiver uptake multivariable results

Table 3 shows results from a series of unadjusted and adjusted GLS models of PA waiver uptake. In the former, the relationship between waivered prescriber supply per capita, the primary independent variable, and PA waiver uptake per capita was significant (β = 0.025, SE = 0.003). Unadjusted models also found that states with more per capita OTPs offering buprenorphine and methadone (β = 0.405, SE = 0.098), OTPs offering only methadone (β = 0.698, SE = 0.241), non-OTP facilities offering buprenorphine (β = 0.021, SE = 0.003), and inpatient facilities offering any MOUD (β = 0.201, SE = 0.031) were associated with significantly higher waiver uptake among PAs. Higher rate of opioid overdose (β = 0.002, SE = 0.001) was also associated with greater uptake in unadjusted models. Additionally, PAs per capita and Medicaid expansion were associated with higher waiver uptake, as was the interaction between waivered prescriber supply and PA practice autonomy (β = 0.029, SE = 0.005). Physicians per capita, PA practice autonomy, percent of residents on Medicaid, percent of residents uninsured, and rurality were not associated with PA waiver uptake in unadjusted models.

Table 3.

GLS regression models of state level waiver uptake among physician assistants.

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted Multivariable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β | SE | β | SE |

|

| ||||

| OUD Treatment Characteristics | ||||

| Waivered prescriber supply | 0.025*** | 0.003 | 0.030*** | 0.008 |

| Opioid overdose rate | 0.002* | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.0003 |

| OTPs with methadone and buprenorphine | 0.405*** | 0.098 | −0.086 | 0.113 |

| OTPs with methadone | 0.698** | 0.241 | −0.302 | 0.264 |

| Non-OTPs with buprenorphine | 0.021*** | 0.003 | 0.045 | 0.102 |

| Inpatient facilities with any MOUD | 0.201*** | 0.031 | 0.011 | 0.107 |

| Healthcare Characteristics | ||||

| Waivered prescriber supply x practice autonomy | 0.029*** | 0.005 | −0.003 | 0.008 |

| Practice autonomy | 0.013 | 0.008 | 0.0001 | 0.011 |

| Physicians per capita | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.001 |

| Physician assistants per capita | 0.013*** | 0.002 | 0.001*** | 0.0001 |

| Medicaid expansion status | 0.016* | 0.007 | 0.015 | 0.009 |

| Percent of residents on Medicaid | 0.092 | 0.063 | −0.033 | 0.063 |

| Percent of residents uninsured | −0.134 | 0.122 | 0.255 | 0.137 |

| Proportion rural | −0.007 | 0.027 | −0.034 | 0.023 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

In multivariable regression, PA waiver uptake was significantly, positively associated with waivered prescriber supply (β = 0.030, SE = 0.008). PAs per capita was also positively associated with waiver uptake (β = 0.001, SE = 0.0001). No other covariates were significantly associated with PA waiver uptake in multivariable regression, including the interaction between waivered prescriber supply and practice autonomy. These results suggest an addition of thirty-three waivered prescribers to existing supply is associated with an increase of one waivered PA. The results of our sensitivity analyses were consistent with our main results.

4. Discussion

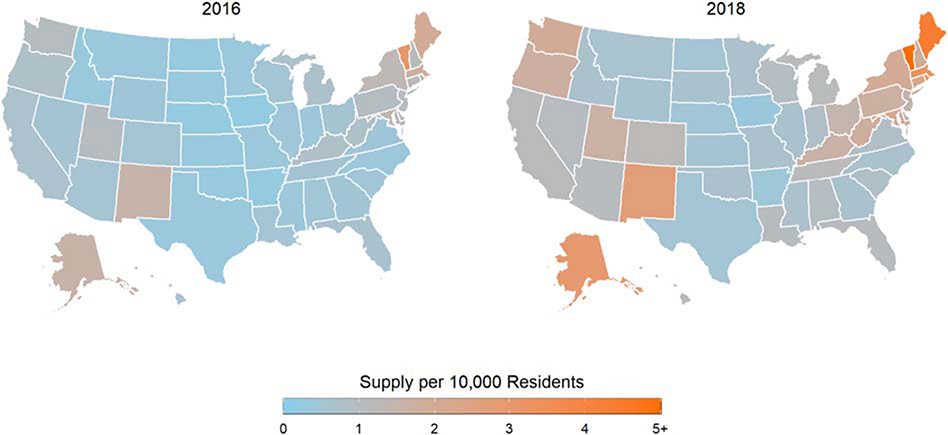

CARA attempted to scale up OUD treatment capacity by allowing NPs and PAs to obtain buprenorphine prescribing waivers. We found that existing waivered prescriber supply at the state level is strongly associated with waiver uptake among NPs and PAs during the first years after CARA. States with greater waivered prescriber supply experienced greater waiver uptake among NPs and PAs, after accounting for other healthcare and opioid-related characteristics. Although the national supply of waivered prescribers increased substantially due to the influx of waivered NPs and PAs, the waiver expansion may have increased treatment capacity disparities between states (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Waivered prescriber supply per 10,000 residents pre- to post-waiver expansion.

Historically, NPs and PAs tend to be more densely located in areas of high physician density, and work in collaborative practice environments with physicians (LaBelle et al., 2016; Lagisetty et al., 2017; Lin et al., 1997; Shaffer & Zolnik, 2014). As such, it is possible that NPs and PAs may be more likely to acquire waivers if they practice in states with a high supply of waivered physician prescribers. State-level characteristics that might contribute to both increased waivered physician prescriber supply and waiver uptake among NPs and PAs include decreased stigma surrounding OUD treatment or perceptions of increased need for MOUD. Negative perceptions of MOUD, such as concerns about diversion or disbelief in MOUD, are more common among physicians who have not obtained buprenorphine waivers in comparison to waivered physicians who are not prescribing to capacity (Huhn & Dunn, 2016). Negative perceptions of MOUD may be less common among clinicians in states where there is a high supply of physician prescribers, which may ease waiver acquisition among NPs and PAs.

Research assessing uptake of prescribing waivers among physicians has found that states with higher opioid overdose rates tend to have greater waiver uptake, but we did not observe these trends in our assessment of NP and PA waiver uptake (Knudsen et al., 2017; Stein et al., 2015). One potential explanation for this is workplace culture regarding OUD and MOUD. NPs and PAs may be more likely to acquire waivers if their workplace has waivered physician prescribers who treat patients with MOUD. Research examining nurses’ adoption of evidencedbased practices suggests that workplace culture, structure, and resources can either facilitate or impede adoption (Banning, 2004; Dalheim et al., 2012; Duncombe, 2018; Gerrish & Clayton, 2004; Kitson et al., 1998). In the context of waiver acquisition, nurses’ uptake may be more likely in workplaces with waivered physician prescribers who can provide peer support and clinical guidance on MOUD. Research has found that clinical guidance on MOUD from an experienced physician can increase the likelihood of obtaining a waiver among nonwaivered physicians, and given our results, it seems likely this dynamic may persist with NPs and PAs (Huhn & Dunn, 2016). Workplace characteristics likely influence waiver uptake, and future research should assess the role of practice-level facilitators and barriers to waiver uptake among NPs and PAs.

In accordance with Spetz et al. (2019)’s prior work on NP and PA waiver uptake, we found that practice autonomy was significantly associated with NP but not PA waiver uptake after adjustment. NP prescriptive authority has been associated with increased scope-of-care delivery, which may facilitate both waiver uptake and MOUD prescribing (Barnes et al., 2018; Park et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2015). NPs may be more likely to acquire waivers in states that allow them to prescribe MOUD without additional barriers to prescribing (i.e., mandatory relationships with physicians who provide oversight, additional training requirements postlicensure). Increased supply of NPs was also associated with NP waiver uptake, which aligns with prior research assessing NP scope-of-care and availability of NPs (Kandrack et al., 2019). However, we were unable to discern which waivered NPs or PAs prescribe MOUD. Thus, additional work is needed to assess NPs’ and PAs’ patterns of buprenorphine prescribing with respect to state characteristics such as practice autonomy.

Medicaid expansion was positively associated with waiver uptake among NPs but not PAs. Prior work has demonstrated that physician waiver uptake has been greater in states that have expanded Medicaid versus in those that have not (Knudsen et al., 2015). However, we found that percent of residents enrolled in Medicaid was negatively associated with waiver uptake among NPs. This may be reflective of Medicaid reimbursement of NPs, which varies from 75% to 100% of the physician rate for primary care services across states (Barnes et al., 2017). NPs are more likely to work in primary care and accept Medicaid patients in states that reimburse at 100% of the physician rate (Barnes et al., 2017). Percent of uninsured residents was also positively associated with NP, but not PA, waiver uptake. Reimbursement policies may influence the decision to acquire a buprenorphine waiver, and future research should assess if variations in Medicaid reimbursement are associated with NP waiver uptake.

The results of this work suggest that the waiver expansion to NPs and PAs scaled up treatment in areas of the country with a low supply of waivered prescribers, but states with a high existing supply of prescribers experienced more substantial gains. States in all tertiles experienced significant increases in waivered provider supply, but marked differences in supply persisted post-waiver expansion. While expanding buprenorphine prescribing eligibility to NPs and PAs is undoubtedly an important step to increase OUD treatment availability, our results suggest that additional solutions are needed to scale up MOUD in underserved states. One potential mechanism to increase waiver uptake among NPs and PAs is to decrease the duration of buprenorphine prescribing training, which is substantially longer for NPs and PAs than for physicians. While adequate training is important to ensure treatment fidelity, training should not be a substantial barrier for NPs or PAs interested in prescribing buprenorphine. Obtaining buprenorphine on the street is becoming increasingly common, and people are primarily using it to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms (Genberg et al., 2013; Monico et al., 2015). Given the rising prevalence of illicit buprenorphine use, it is critical that we expand the supply of waivered prescribers so that those with OUD can access treatment in a timely fashion. While 24-hours of buprenorphine prescribing training will undoubtedly prepare NPs and PAs, it likely deters some from obtaining a waiver at all. Some have called for the removal of the training requirements completely, or proposed a significant reduction in training length to mitigate the burden of acquiring a waiver (Frank et al., 2018). Reducing the length of training requirements for buprenorphine prescribing privileges may encourage waiver uptake among NPs and PAs.

4.1. Limitations

This work is not without limitations. While we used longitudinal data on waivered prescribers and state characteristics, all data are observational and from multiple sources. We attempted to characterize states healthcare and policy environments as they relate to waiver uptake, but we likely did not capture all state-level policies that influence uptake. Specifically, Medicaid reimbursement of NPs and PAs for MOUD patient visits likely affects the decision to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, but we were unable to characterize states’ Medicaid reimbursement structures. State and workplace culture regarding OUD treatment and the opioid epidemic likely influences whether NPs and PAs obtain buprenorphine prescribing waivers.

Future work should examine the role of workplace culture, structure, and resources on NPs’ and PAs’ waiver uptake. While this work characterizes state level waiver uptake, we were unable to link waivered prescribers with their prescribing of buprenorphine. Not all waivered prescribers prescribe buprenorphine, thus waivered prescriber supply is only a proxy for actual availability of MOUD treatment. Additionally, we were able to assess uptake of only 30-patient maximum waivers among NPs and PAs. Thus, these results may not be generalizable to correlates of NP and PA uptake of 100-patient maximum waivers. Finally, we cannot determine causality from this work due to observational methodology.

4.2. Conclusion

We found that state-level NP and PA waiver uptake is strongly associated with existing waivered prescriber supply. The waiver expansion appears to have increased the supply of waivered prescribers in all states, but most substantially in states with an already-high supply prior to the waiver expansion. Future research should examine the effect of the waiver expansion to NPs and PAs on buprenorphine prescribing. The new involvement of NPs and PAs appears to have increased OUD treatment capacity, but additional efforts are needed to encourage waiver uptake in underserved areas.

Highlights.

Waivered prescriber supply is associated with nurse practitioner waiver uptake

Waivered prescriber supply is associated with physician assistant waiver uptake

Increased scope-of-practice is associated with nurse practitioner but not physician assistant waiver uptake

Disparities in state prescriber supply persist despite overall increases in supply

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse [T32-DA041898–03, 2018].

Appendix 1

Table 4.

Lagged vs.

| Unadjusted | Multivariable† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β | SE | β | SE | |

|

| ||||

| Opioid Overdose Rate | 0.007*** | 0.001 | 0.012** | 0.004 |

| Lagged Opioid Overdose Rate | 0.009*** | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

includes both opioid overdose rate and lagged opioid overdose rate

Table 5.

OLS regression models of waiver uptake among physician assistants

| Unadjusted | Multivariable† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β | SE | β | SE | |

|

| ||||

| Opioid Overdose Rate | 0.001*** | 0.001 | 0.003** | 0.001 |

| Lagged Opioid Overdose Rate | 0.002*** | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

includes both opioid overdose rate and lagged opioid overdose rate

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Samantha Auty: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing - original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization

Michael Stein: Conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and supervision

Alexander Walley: Conceptualization, methodology, and writing – review and editing

Mari-Lynn Drainoni: Conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and supervision

References

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. (2018). Scope of Practice Policy. https://www.collegeofparamedics.co.uk/downloads/Paramedic_-_Scope_of_Practice_Policy.pdf

- Barton Associates. (2019). Physician Assistant Scope of Practice Laws. https://www.bartonassociates.com/locum-tenens-resources/pa-scope-of-practice-laws

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Wide-ranging data for epidemiological research (WONDER) https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2018). State Medicaid and CHIP Applications, Eligibility Determinations, and Enrollment Data. https://data.medicaid.gov/Enrollment/State-Medicaid-and-CHIP-Applications-EligibilityD/n5ce-jxme

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018a). Buprenorphine Waiver Notification System. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assistedtreatment/practitioner-program-data/certified-practitioners [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018b). National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/nationalsurvey-substance-abuse-treatment-services-n-ssats-2017-data-substance-abuse

- U.S. Department of Health Resources and Service Administration. (2019). Area Health Resource File. U.S. Department of Health Resources and Service Administration. http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov

- United States Census Bureau. (2019). State population totals and components of change: 2010–2018. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010sstate-total.html

- American Association of Physician Assistants. (2016). The Six Key Elements of a Modern PA Practice Act. http://www.aapa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/%0AIssue_Brief_Six_Key_Elements.pdf

- Andrilla CHA, Moore TE, Patterson DG, & Larson EH (2019). Geographic Distribution of Providers With a DEA Waiver to Prescribe Buprenorphine for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: A 5-Year Update. The Journal of Rural Health, 35(1), 108–112. 10.1111/jrh.12307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Moore TE, Coulthard C, & Larson EH (2018). Projected Contributions of Nurse Practitioners and Physicians Assistants to Buprenorphine Treatment Services for Opioid Use Disorder in Rural Areas. Medical Care Research and Review, 107755871879307. 10.1177/1077558718793070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banning M (2004). Nurse prescribing, nurse education and related research in the United Kingdom: a review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 24(6), 420–427. 10.1016/j.nedt.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Maier CB, Altares Sarik D, Germack HD, Aiken LH, & McHugh MD (2017). Effects of Regulation and Payment Policies on Nurse Practitioners’ Clinical Practices. Medical Care Research and Review, 74(4), 431–451. 10.1177/1077558716649109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, & Martsolf G (2018). Rural And Nonrural Primary Care Physician Practices Increasingly Rely On Nurse Practitioners. Health Affairs, 37(6), 908–914. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ML, Lee D, & Frank RG (2019). In Rural Areas, Buprenorphine Waiver Adoption Since 2017 Driven By Nurse Practitioners And Physician Assistants. Health Affairs, 38(12), 2048–2056. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetham T, Saloner B, Wakeman SE, Gaye M, & Barnett ML (2019). Access to OfficeBased Buprenorphine Treatment in Areas With High Rates of Opioid-Related Mortality. Annals of Internal Medicine. 10.7326/M18-3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JR, Butler B, Lawrance A, Batey R, & Salmelainen P (2009). Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 104(1–2), 73–77. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2006). The Determinations Report: A Report On the Physician Waiver Program Established by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (“DATA”). https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/medication_assisted/determinations-report-physician-waiver-program.pdf

- Connery HS (2015). Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 23(2), 63–75. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalheim A, Harthug S, Nilsen RM, & Nortvedt MW (2012). Factors influencing the development of evidence-based practice among nurses: a self-report survey. BMC Health Services Researc, 12, 367. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncombe DC (2018). A multi-institutional study of the perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(5–6), 1216–1226. 10.1111/jocn.14168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornili KS, & Fogger SA (2017). Nurse Practitioner Prescriptive Authority for Buprenorphine: From DATA 2000 to CARA 2016. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 28(1), 43–48. 10.1097/jan.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JW, Wakeman SE, & Gordon AJ (2018). No end to the crisis without an end to the waiver. Substance Abuse, 39(3), 263–265. 10.1080/08897077.2018.1543382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg BL, Gillespie M, Schuster CR, Johanson C-E, Astemborski J, Kirk GD, Vlahov D, & Mehta SH (2013). Prevalence and correlates of street-obtained buprenorphine use among current and former injectors in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 38(12), 2868–2873. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish K, & Clayton J (2004). Promoting evidence-based practice: an organizational approach. Journal of Nursing Management, 12(2), 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhn AS, & Dunn KE (2016). Why aren’t physicians prescribing more buprenorphine? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 78, 1–7. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, & McCance-Katz E (2015). National and State Treatment Need and Capacity for Opioid Agonist Medication-Assisted Treatment. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH, 105(8), E55–E63. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandrack R, Barnes H, Martsolf GR (2019). Nurse Practitioner Scope of Practice Regulations and Nurse Practitioner Supply. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 1077558719888424. 10.1177/1077558719888424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey CP &, & Gertner AK (2019). State Officials Shouldn’t Wait For Federal Action To Increase Opioid Addiction Treatment Access. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190517.911878/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A, Harvey G, & McCormack B (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care: QHC, 7(3), 149–158. 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK (2015). The Supply of Physicians Waivered to Prescribe Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorders in the United States: A State-Level Analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 76(4), 644–654. internal-pdf://62.232.39.87/Knudsen-2015-The Supply of Physicians Waivered.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Havens JR, Lofwall MR, Studts JL, & Walsh SL (2017). Buprenorphine physician supply: Relationship with state-level prescription opioid mortality. Drug Alcohol Depend, 173 Suppl, S55–S64. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Lofwall MR, Havens JR, & Walsh SL (2015). States’ implementation of the Affordable Care Act and the supply of physicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 157, 36–43. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, & Alexander GC (2015). The Prescription Opioid and Heroin Crisis: A Public Health Approach to an Epidemic of Addiction. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 559–574. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, & Samet JH (2016). Office-Based Opioid Treatment with Buprenorphine (OBOT-B): Statewide Implementation of the Massachusetts Collaborative Care Model in Community Health Centers. J Subst Abuse Treat, 60, 6–13. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagisetty P, Klasa K, Bush C, Heisler M, Chopra V, & Bohnert A (2017). Primary care models for treating opioid use disorders: What actually works? A systematic review. PLoS One, 12(10), e0186315. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Burns P, & Nochajski T (1997). The geographic distribution of nurse practitioners in the United States. In Applied Geographic Studies (Vol. 1). 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6319(199724)1:43.3.CO;2-# [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monico LB, Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE, Olsen YK, & Jaffe JH (2015). Prior Experience with Non-Prescribed Buprenorphine: Role in Treatment Entry and Retention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 57, 57–62. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and M. (2019). Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. National American Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Han X, & Pittman P (2019). Does expanded state scope of practice for nurse practitioners and physician assistants increase primary care utilization in community health centers? Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2013). 25th Annual legislative update: Evidence-based practice reforms improve access to APRN care. The Nurse Practitioner, 38(1). https://journals.lww.com/tnpj/Fulltext/2013/01000/25th_Annual_legislative_update__Evidence_based.7.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2014). 26th Annual Legislative Update: Progress for APRN authority to practice. The Nurse Practitioner, 39(1). https://journals.lww.com/tnpj/Fulltext/2014/01000/26th_Annual_Legislative_Update__Progress_for_APRN.7.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2015). 27th Annual APRN legislative update: advancements continue for APRN practice. The Nurse Practitioner, 40(1), 16–42. 10.1097/01.NPR.0000457433.04789.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2016). 28th Annual APRN Legislative Update: Advancements continue for APRN practice. The Nurse Practitioner, 41(1), 21–48. 10.1097/01.NPR.0000475369.78429.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2017). 29th Annual APRN Legislative Update. The Nurse Practitioner, 42(1), 18–46. 10.1097/01.NPR.0000511006.68348.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2018). 30th Annual APRN Legislative Update: Improving access to healthcare one state at a time. The Nurse Practitioner, 43(1). https://journals.lww.com/tnpj/Fulltext/2018/01000/30th_Annual_APRN_Legislative_Update__Improving.6.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2019). 31st Annual APRN Legislative Update: Improving state practice authority and access to care. The Nurse Practitioner, 44(1). https://journals.lww.com/tnpj/Fulltext/2019/01000/31st_Annual_APRN_Legislative_Update__Improving.5.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer R, & Zolnik E (2014). The geographic distribution of physician assistants in the US: Clustering analysis and changes from 2001 to 2008. In Applied Geography (Vol. 53). 10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.06.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spetz J, Toretsky C, Chapman S, Phoenix B, & Tierney M (2019). Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Waivers to Prescribe Buprenorphine and State Scope of Practice RestrictionsNurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Waivers to Prescribe BuprenorphineLetters. JAMA, 321(14), 1407–1408. 10.1001/jama.2019.0834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Gordon A, Dick A, Burns RM, Pacula R, Farmer CM, Leslie DL, & Sorbero M (2015). Supply of buprenorphine waivered physicians: The influence of state policies. Jounral of Substance Abuse Treatment 48(1), 104–111. 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2018-nsduh-annual-nationalreport [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LE, Moore BA, Chawarski MC, Pantalon MV, Barry D, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, & Fiellin DA (2008). Buprenorphine/naloxone treatment in primary care is associated with decreased human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35(1), 87–92. 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H, Hockenberry JM, & Pollack HA (2018). Association of Buprenorphine-Waivered Physician Supply With Buprenorphine Treatment Use and Prescription Opioid Use in Medicaid Enrollees. JAMA Netw Open, 1(5), e182943. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Ye Z, Brewer C, & Spetz J (2015). Impact of State Nurse Practitioner Scope-ofPractice Regulation on Healthcare Delivery: Systematic Review. In Nursing outlook (Vol. 64). 10.1016/j.outlook.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]