Abstract

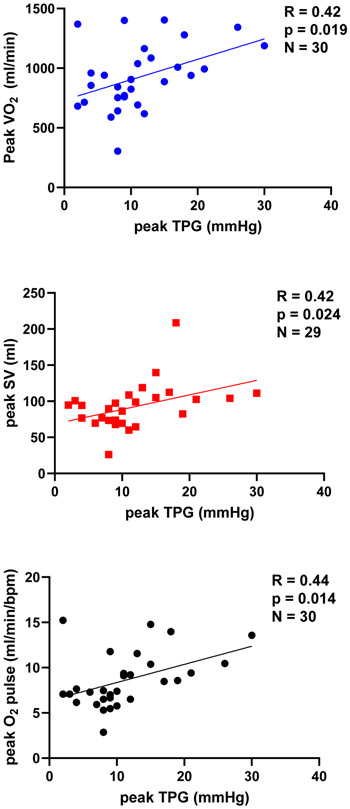

Elevated left ventricular filling pressure (measured as mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, PCWPm) at rest or with exercise is diagnostic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). However, the capacity of the right ventricle to compensate for a high PCWPm and thus maintain an appropriate transpulmonary gradient (TPG) and perfusion of the pulmonary capillaries is likely an important contributor to gas exchange efficiency and exercise capacity. Therefore, this study aimed to determine whether a higher TPG at peak exercise is associated with superior exercise capacity and gas exchange. Gas exchange data from dyspneic patients referred for exercise right heart catheterization were retrospectively analyzed and patients were split into two groups based on TPG. Patients with a higher TPG at peak exercise had a higher peak VO2 (1025±227 vs.823±276, p=0.038), end-tidal partial pressure of CO2 (PETCO2; 42.2±7.9 vs. 38.0±4.7, p=0.044), and gas exchange estimates of pulmonary vascular capacitance (GXCAP; 408±90 vs. 268±108, p=0.001). A higher TPG at peak exercise correlated with a higher peak VO2, O2 pulse, and stroke volume (R=0.42, 0.44 and 0.42, respectively, all p<0.05). These findings indicate that a greater TPG with exercise might be important for improving exercise capacity in HFpEF.

Keywords: transpulmonary gradient, cardiopulmonary exercise test, right heart catheterization, exercise intolerance

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) occurs when cardiac output is inadequate to meet the metabolic demands of the body. In HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), increased cardiomyocyte stiffness decreases myocardial compliance and impairs left ventricular (LV) filling1. Consequently, the LV is shifted on the Frank-Starling curve and a higher LV filling pressure is required to generate a given end-diastolic volume and stroke volume1. High LV filling pressure is characteristic of HFpEF, particularly during exercise when an increased cardiac output is needed to match oxygen delivery with augmented metabolic demands2. Despite compensatory increases in LV filling pressure, HFpEF patients experience symptoms of exertional dyspnea and have reduced cardiac reserve and exercise capacities1,2.

Increases in LV filling pressure are transmitted to the pulmonary circulation. Indeed, HFpEF is diagnosed by evidence of high pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) measured during right heart catheterization (≥15 mmHg at rest or ≥25 mmHg during exercise)2. Mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAPm) also increases in HFpEF, either proportionally with mean PCWP (PCWPm) or out-of-proportion due to the presence of underlying pulmonary vascular disease3; the difference between PAPm and PCWPm, termed transpulmonary gradient (TPG), is of diagnostic importance in HFpEF. Assuming a given pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), a decrease in TPG will correlate with a proportional drop in cardiac output4. While increases in PCWPm with exercise are characteristic of HFpEF, a greater increase in PCWPm relative to the increase in PAPm, such that TPG decreases, may impact perfusion across the pulmonary capillary bed, be indicative of more left atrial dysfunction, and lead to impairments in gas exchange and decrements in exercise capacity.

Increased pulmonary capillary hydrostatic pressure caused by elevated LV filling pressure and pulmonary congestion distends the pulmonary capillaries and may cause fluid to leak out of the capillary into the interstitial spaces of the lung5. Extravascular lung fluid impedes gas exchange, resulting in areas of ventilation-perfusion mismatch and ventilatory inefficiency, which may cause abnormal breathing patterns and reduced exercise capacity in HFpEF6. These changes may alter non-invasive indices of ventilatory control such as end-tidal partial pressure of CO2 (PETCO2) and ventilatory efficiency (VE/VCO2), or gas exchange derived estimates of pulmonary vascular capacitance (GXCAP). Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between TPG and pulmonary gas exchange metrics at rest and during exercise in a mixed population of patients with exertional dyspnea referred to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for hemodynamic assessment of suspected HFpEF. It was hypothesized that a lower peak exercise TPG would correlate with impaired gas exchange, specifically the ventilatory equivalent for CO2, and a lower exercise capacity.

Methods

Cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPETs) from patients with exertional dyspnea referred to the Mayo Clinic cardiac catheterization laboratory for suspected HFpEF between 2009 and 2012 were retrospectively analyzed. CPETs were included if 1) incremental cycling exercise was performed, 2) PAPm and PCWPm were recorded at rest and peak workload, and 3) at least 2 workloads were achieved. Data from 30 patients (21 females, age = 66 ± 13 y, BMI = 30.6 ± 5.4 kg/m2) who exercised to volitional exhaustion with simultaneous breath-by-breath gas exchange and invasive hemodynamic monitoring was used for this study. The diagnostic criteria for HFpEF was a PCWPm ≥15 mmHg at rest or ≥25 mmHg during exercise7,8. The cohort was ranked in order of lowest to highest TPG (range: 2-30 mmHg) in their final exercise stage and divided into two groups (Low TPG and High TPG).

Patients cycled in the supine position (Cath Ergometer, Medical Positioning Inc., Kansas City, MO, USA) for 5 min at 20W before the workload was incrementally increased in ~2 min stages until volitional exhaustion. Breath-by-breath pulmonary gas exchange (Ultima, Medgraphics, Saint Paul, MN, USA)9 was performed to quantify oxygen uptake (VO2), carbon dioxide production (VCO2), tidal volume (VT), breathing frequency (fb), inspiratory time (Ti), end-tidal partial pressure of CO2 (PETCO2). Minute ventilation (VE) was calculated as the product of VT and fb. The respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was calculated as the quotient of VCO2/VO2. Breath-by-breath data was averaged over the last 30 seconds of each workload using a custom script in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Oxygen pulse (O2 pulse = VO2/HR), ventilatory equivalent for CO2 (VE/VCO2), and gas exchange estimates of pulmonary vascular capacitance (GXCAP = O2 pulse x PETCO2) were derived10.

Catheters were placed in the pulmonary and radial arteries2. Systolic (PAPs) and diastolic pulmonary artery pressure (PAPd) were taken as the maximum and minimum of the pulmonary artery pressure waveform at end-expiration, respectively. Mean right atrial (RAPm) and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWPm) were taken at mid a-wave during end-expiration. The transpulmonary gradient (TPG) was calculated as PAPm-PCWPm. Systolic arterial blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were taken as the maximum and minimum of the arterial pressure waveform, respectively.

Arterial and mixed-venous oxygen saturation were measured from systemic and pulmonary blood samples, respectively, and arterial (CaO2) and mixed-venous (CvO2) oxygen content were calculated (saturation x hemoglobin x 1.34 x 10). Arteriovenous oxygen difference (AVO2diff) was calculated as CaO2-CvO2. Cardiac output was calculated using the Fick equation as the quotient of VO2 and AVO2diff. Stroke volume was calculated as cardiac output divided by heart rate. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated as TPG divided by cardiac output and pulmonary compliance was calculated as stroke volume divided by pulmonary pulse pressure (PAPs – PAPd). Assumptions of normality and homogeneity were assessed using a Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. If these assumptions were met, variables were evaluated using an unpaired t-test with a significance level of 0.05 and presented as mean ± standard deviation, otherwise variables were assessed using a Mann-Whitney U Test and reported as median and interquartile range. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to explore relationships between variables. Given the mechanistic basis for this study and small sample size, correction for multiple hypothesis testing was not performed.

Results

Patients were split into two groups above and below the median (9.5 mmHg) based on their peak exercise TPG (Mean ± SD, Low TPG = 6±3 mmHg; High TPG =16±6 mmHg). Table 1 depicts the subject characteristics of the cohort as a whole and divided into TPG groups. There were more females in the Low TPG group (p=0.050). There were no significant differences in age, height, weight, BMI, or BSA between the Low TPG and High TPG group.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and resting cardiovascular, ventilatory, and gas exchange variables

| All | Low TPG (≤9 mmHg) |

High TPG (>9 mmHg) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject characteristics | ||||

| Subjects, N | 30 | 15 | 15 | |

| % female | 70 | 87 | 53 | 0.050 |

| % HFpEF | 53 | 67 | 40 | 0.272 |

| Age, y | 69 (60-73) | 73 (62-77) | 68 (41-74) | 0.139 |

| Height, cm | 168 ± 5 | 166 ± 9 | 170 ± 9 | 0.220 |

| Weight, kg | 86 ± 19 | 81 ± 20 | 92 ± 17 | 0.103 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.6 ± 5.4 | 29.3 ± 5.2 | 32.0 ± 5.4 | 0.178 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.094 |

| Pulmonary gas exchange | ||||

| VO2, ml/min | 245 (193-279) | 239 (155-273) | 212 (137-248) | 0.901 |

| VCO2, ml/min | 198 (146-216) | 203 (149-216) | 186 (120-216) | 0.967 |

| VO2, ml/min/kg | 2.84 ± 0.73 | 3.02 ± 0.50 | 2.66 ± 0.88 | 0.178 |

| RER | 0.82 (0.76-0.89) | 0.85 (0.79-0.97) | 0.88 (0.80-0.90) | 0.034 |

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| HR, bpm | 68 ± 11 | 71 ± 11 | 65 ± 11 | 0.144 |

| Stroke volume, ml | 89 ± 42 | 92 ± 50 | 87 ± 35 | 0.765 |

| O2 pulse, ml/min/bpm | 3.73 ± 1.58 | 3.6 ± 1.7 | 3.8 ± 1.4 | 0.725 |

| MAP, mmHg | 93 (89-101) | 95 (91-103) | 91 (89-99) | 0.767 |

| PAPm, mmHg | 23 ± 5 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 6 | 0.883 |

| PCWPm, mmHg | 13 (11-16) | 14 (13-16) | 13 (10-16) | 0.306 |

| TPG, mmHg | 9.7 ± 9.7 | 9.2 ± 3.8 | 10.1 ± 2.7 | 0.444 |

| Cardiac output, l/min | 6.0 ± 2.7 | 6.4 ± 2.9 | 5.6 ± 2.5 | 0.471 |

| Cardiac index, l/min/m2 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 0.189 |

| PVR, WU | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 0.419 |

| PAC, ml/mmHg | 5.0 ± 3.2 | 5.2 ± 4.0 | 4.7 ± 2.1 | 0.666 |

| Ventilation and breathing pattern | ||||

| VE, l/min | 6.5 (5.6-8.4) | 6.2 (5.5-8.0) | 6.3 (3.9-8.1) | 0.678 |

| fb, break/min | 15.0 ± 4.6 | 15.6 ± 5.2 | 14.4 ± 4.0 | 0.480 |

| VT, l | 0.54 (0.41-0.66) | 0.57 (0.55-0.70) | 0.57 (0.43-1.1) | 0.406 |

| fb/VT | 33 ± 23 | 35 ± 21 | 32 ± 26 | 0.740 |

| VT/Ti | 0.45 (0.32-0.52) | 0.46 (0.41-0.53) | 0.54 (0.18-0.86) | 0.934 |

| Gas Exchange | ||||

| VE/VCO2 | 36 ± 5 | 37 ± 5 | 36 ± 6 | 0.793 |

| PETCO2, mmHg | 41 (35-44) | 39 (35-41) | 43 (33-45) | 0.318 |

| PECO2/PETCO2 | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 0.66 ± 0.05 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.218 |

| GXCAP | 147 ± 64 | 142 ± 67 | 153 ± 62 | 0.630 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. BMI: body mass index, BSA: body surface area, VO2: oxygen consumption, VCO2: carbon dioxide production, RER: respiratory exchange ratio, HR: heart rate, MAP: mean arterial pressure, PAPm: mean pulmonary artery pressure, PCWPm: mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, TPG: transpulmonary gradient, PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance, PAC: pulmonary arterial compliance, VE: minute ventilation, fb: breathing frequency, VT: tidal volume, VT/Ti,: tidal volume to inspiratory time ratio, PETCO2: end-tidal partial pressure of CO2, PECO2: partial pressure of expiratory CO2, GXCAP: gas exchange estimated pulmonary capacitance.

At rest, patients in the High TPG group had a higher RER compared to the Low TPG patients (Table 1). All systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics were similar at rest between TPG groups. At peak exercise VO2, VCO2 stroke volume, PETCO2, GXCAP and O2 pulse were higher in the High TPG group (Table 2). Patients in the High TPG group had a lower peak PCWPm and a higher peak PVR. There was a trend towards a higher cardiac output and a lower VEA/CO2 in the High TPG group at peak exercise. Peak VO2, stroke volume, and O2 pulse correlated with peak TPG (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular, ventilatory, and gas exchange variables at peak exercise

| All | Low TPG (≤9 mmHg) |

High TPG (>9 mmHg) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise capacity | ||||

| Workload, W | 40 (30-50) | 40 (33-40) | 40 (30-50) | 0.064 |

| VO2, ml/min | 924 ± 3 | 823 ± 276 | 1025 ± 227 | 0.038 |

| VCO2, ml/min | 966 ± 276 | 847 ± 280 | 1086 ± 221 | 0.015 |

| VO2, ml/min/kg | 10.6 (8.9-12.4) | 8.5 (6.4-9.0) | 10.8 (8.8-11.6) | 0.031 |

| RER | 1.07 ± 0.16 | 1.06 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.14 | 0.809 |

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| HR, bpm | 110 ± 21 | 114 ± 22 | 108 ± 21 | 0.4 67 |

| Stroke volume, ml | 92 ± 32 | 76 ± 19 | 104 ± 35 | 0.014 |

| O2 pulse, ml/min/bpm | 8.60 ± 3.01 | 6.97 ± 2.67 | 10.02 ± 2.59 | 0.004 |

| MAP, mmHg | 112 ± 19 | 112 ± 18 | 112 ± 21 | 0.966 |

| PAPm, mmHg | 35 ± 8 | 36 ± 9 | 35 ± 7 | 0.697 |

| PCWPm, mmHg | 24 ± 10 | 29 ± 10 | 19 ± 9 | 0.007 |

| TPG, mmHg | 10 (8-15) | 8 (4-8) | 14 (11-19) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac output, l/min | 10.0 ± 3.1 | 8.9 ± 2.5 | 11.0 ± 3.3 | 0.063 |

| Cardiac index, l/min/m2 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 0.222 |

| PVR, WU | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 0.019 |

| PAC, ml/mmHg | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 0.805 |

| Ventilation and breathing pattern | ||||

| VE, l/min | 31.4 ± 9.4 | 29.0 ± 9.0 | 33.9 ± 9.3 | 0.153 |

| fb, break/min | 30.0 (23.5-33.7) | 24.7 (17.3-25.7) | 31.3 (23.3-36.8) | 0.339 |

| VT, l | 1.10 ± 0.35 | 1.08 ± 0.31 | 1.12 ± 0.39 | 0.725 |

| fb/VT | 31 ± 16 | 29 ± 13 | 34 ± 19 | 0.421 |

| VT/Ti | 1.47 ± 0.41 | 1.37 ± 0.40 | 1.57 ± 0.40 | 0.182 |

| Gas Exchange | ||||

| VE/VCO2 | 32 (29-34) | 34 (31-55) | 29 (27-32) | 0.067 |

| PETCO2, mmHg | 40.1 ± 6.8 | 38.0 ± 4.7 | 42.2 ± 7.9 | 0.044 |

| PECO2/PETCO2 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.773 |

| GXCAP | 343 ± 120 | 268 ± 108 | 408 ± 90 | 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. VO2: oxygen consumption, VCO2: carbon dioxide production, RER: respiratory exchange ratio, HR: heart rate, MAP: mean arterial pressure, PAPm: mean pulmonary artery pressure, PCWPm: mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, TPG: transpulmonary gradient, PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance, PAC: pulmonary arterial compliance, VE: minute ventilation, fb: breathing frequency, VT: tidal volume, VT/Ti: tidal volume to inspiratory time ratio, PETCO2: end-tidal partial pressure of CO2, PECO2: partial pressure of expiratory CO2, GXCAP: gas exchange estimated pulmonary capacitance.

Figure 1.

Correlations between VO2, stroke volume, and O2 pulse with TPG in the final exercise stage.

Discussion

In a group of dyspneic patients referred for right heart catheterization with exercise, those with a higher peak exercise TPG had a higher oxygen uptake attained during the test and increased forward blood flow indicated by stroke volume and O2 pulse. Although ventilatory parameters such as tidal volume and breathing frequency were similar between groups, patients with a high TPG had higher GXCAP and PETCO2, suggesting better ventilation-perfusion matching in this group10. The increase in PCWPm relative to PAPm during exercise may be important for maintaining perfusion across the pulmonary capillary bed.

An elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure at rest or during exercise is independently used to diagnose HFpEF2. However, many HFpEF patients also show abnormal increases in PAPm11. Indeed, among the HFpEF patients included in this study, there was considerable variability in end-exercise PAPm (32-52 mmHg). The data presented here suggests that a higher TPG was related to a higher VO2, and thus may be important for augmenting blood flow through the pulmonary circulation and optimal ventilation-perfusion matching during exercise. While a limitation of TPG is its dependence on cardiac output4,12, it is a metric describing the relative increase in pressure on either side of the pulmonary capillary bed during exercise, and thus may provide insight into pulmonary vascular response to exercise-induced increases in cardiac output which impacts gas exchange. The cross sectional nature of the present data limits the ability to assess causality. The group with higher TPG displayed lower PCWP during exercise. This may reflect more preserved left atrial mechanics in this group as compared to those with lower TPG and high PCWP13,14, confounding interpretation of the group differences in TPG and gas exchange. Future studies matching patients with similar left atrial mechanics and exercise PCWP would be useful to explore this.

Pulmonary vascular remodeling occurs with advancing age and is a common comorbidity in HFpEF patients which impairs gas exchange and reduces exercise capacity11,15. However, a concomitant increase in pulmonary artery pressure during exercise proportional to the increase in pulmonary venous pressure may be a compensatory mechanism in HFpEF to maintain pulmonary capillary perfusion in these patients.

Acknowledgements

Glenn M. Stewart is supported by the American Heart Association (AHA#19POST34450022) and a Career Development Award in Cardiovascular Disease Research Honoring Dr. Earl H. Wood from Mayo Clinic. Barry A. Borlaug is supported by the National Institute of Heath (RO1 HL128526 and U10 HL110262). Caitlin C. Fermoyle is supported by the Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statements: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Perspective. CircRes. 2019;124:1598–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CSP, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Hear Fail. 2010;3:588–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolle JJ, Waxman AB, Van Horn TL, Pappagianopoulos PP, Systrom DM. Exercise-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2008;118:2183–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naeije R, Vachiery JL, Yerly P, Vanderpool R. The transpulmonary pressure gradient for the diagnosis of pulmonary vascular disease. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine OR, Mellins RB, Senior RM, Fishman AP. The application of Starling’s law of capillary exchange to the lungs. J Clin Invest. 1967;46:934–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reddy YN V, Obokata M, Wiley B, Koepp KE, Jorgenson CC, Egbe A, Melenovsky V, Carter RE, Borlaug BA. The haemodynamic basis of lung congestion during exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2019;73:674 Available from: https://academic.oup.eom/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz713/5586988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pieske B, Tschöpe C, De Boer RA, Fraser AG, Anker SD, Donal E, Edelmann F, Fu M, Guazzi M, Lam CSP, Lancellotti P, Melenovsky V, Morris DA, Nagel E, Pieske-Kraigher E, Ponikowski P, Solomon SD, Vasan RS, Rutten FH, Voors AA, Ruschitzka F, Paulus WJ, Seferovic P, Filippatos G. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: The HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: A consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3297–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlaug BA. Evaluation and management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol [Internet]. 2020;41:145–188. Available from: 10.1038/s41569-020-0363-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Melenovsky V, Olson TP. Abnormal right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling with exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3294–3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor BJ, Olson TP, Chul-Ho Kim, Maccarter D, Johnson BD. Use of noninvasive gas exchange to track pulmonary vascular responses to exercise in heart failure. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med [Internet]. 2013;7:53–60. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3785385&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorter TM, Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Borlaug BA. Exercise unmasks distinct pathophysiologic features in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and pulmonary vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2825–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handoko ML, De Man FS, Oosterveer FPT, Bogaard HJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Westerhof N. A critical appraisal of transpulmonary and diastolic pressure gradients. Physiol Rep. 2016;4:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Egbe A, Yang JH, Pislaru S, Lin G, Carter R, Borlaug BA. Left atrial strain and compliance in the diagnostic evaluation of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telles F, Nanayakkara S, Evans S, Patel HC, Mariani JA, Vizi D, William J, Marwick TH, Kaye DM. Impaired left atrial strain predicts abnormal exercise haemodynamics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayyaz AU, Edwards WD, Maleszewski J J, Konik EA, DuBrock HM, Borlaug BA, Frantz RP, Jenkins SM, Redfield MM. Global pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure and preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. 2018;137:1796–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]