Abstract

Purpose

Overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms might be affected by weather, but only a few clinical studies have investigated this issue. We investigated seasonal variations in OAB-drug prescription rate (DPR) in men using nationwide claims data in Korea.

Methods

A total of 2,824,140 men aged over 18 years were included from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment service – National Patient Sample data between 2012 and 2016. Depending on the monthly average temperature, the seasons were divided into 3 groups, namely, hot (June, July, August, and September), intermediate (April, May, October, and November), and cold (January, February, March, and December) seasons. OAB-DPR was estimated using the claims data, and differences in its rate were examined among the 3 seasonal groups.

Results

The overall OAB-DPR was 1.97% (55,574 of 2,824,140). The OAB-DPR were 0.38%, 0.63%, 0.92%, 1.74%, 4.18%, 7.55%, and 9.69% in the age groups of under 30, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and over 80 years, respectively; thus, the prescription rate increased with age (P<0.001), with a steeper increase after 60 years of age. OAB-DPR was 1.02% in the hot season, 1.19% in the intermediate season, and 1.27% in the cold season, with significant differences among the 3 seasonal groups (P<0.001). These seasonal variations persisted in the subgroup analysis in each age decade (P<0.001).

Conclusions

OAB-DPR varied with seasons and was significantly higher in the cold season than in the hot season, suggesting that cold weather may affect development and aggravation of OAB symptoms in men.

Keywords: Men; Seasons; Urinary bladder, Overactive

INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a prevalent cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) defined as a syndrome of bladder storage function and characterized by a cluster of symptoms including urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia with or without urinary incontinence [1]. Symptoms of OAB may have a detrimental impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL) and could lead to emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances [2]. Multiple urological and nonurological risk factors are associated with the development of OAB, such as age, obesity, cognitive disorders, metabolic syndrome, neurologic disorders, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) [3].

There is also a widely held perception that LUTS vary in severity with seasonal changes, and, in particular, that they worsen in cold weather. According to the 5-year BPH patient-based dataset (2008–2012) of National Health Insurance in Korea, seasonal variations of visiting hospital patients are seen between summer and winter [4]. Several studies have addressed the associations between seasonal variations and LUTS. Yoshimura et al. [5] revealed that winter is an independent risk factor for urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. Choi et al. [6] also reported that seasonal variations are meaningfully associated with LUTS, particularly storage symptoms. Kobayashi et al. [7] demonstrated a significant seasonal difference in nocturia only, which showed a higher score in winter; however, no seasonal difference was seen in uroflowmetric parameters. However, Cartwright et al. [8] reported no significant variation in the urinary symptom scores or uroflowmetric parameters with changes in season. Watanabe et al. [9] also reported no seasonal differences in the urinary symptom scores, although maximum flow rate (Qmax) could be influenced by seasonal changes. On the other hand, Tae et al. [10] demonstrated that female OAB symptoms might be worse during cold season than in other seasons. As seen in the aforementioned studies, seasonal variation might be related to storage symptoms, but such a relationship remains controversial. To obtain robust evidence on this issue, we investigated seasonal variations in OAB-drug prescription rate (DPR) in men using nationwide claims data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Data sources and Study Sample

In South Korea, the National Health Insurance is a universal health coverage system that covers approximately 100% of Korean residents. The claims data of Health Insurance Review Agency (HIRA) is collected when healthcare service providers submit a claim to HIRA for reimbursement for a service that they provided to patients. The HIRA claims data represent 46 million patients each year, accounting for 90% of the total population in Korea. However, given the complexity and large volume of the dataset, its use is typically restricted to researchers. To resolve these limitations and increase the efficiency of data use, the HIRA developed patient sample data that passed validity tests performed by 5 different institutions [11]. Here, we used the national patient sample (NPS) of the HIRA claims data (HIRA-NPS) comprising randomized patients who used the National Health System at least once a year. This dataset passed validity tests performed by 5 different institutions and included 1.4 million patients overall per year (3%) [11]. In this study, we used HIRA-NPS, 2012–2016, from which all men aged over 18 years were included.

2. Climate Data and Seasonal Groups

South Korea’s location is 38°N, 127° 30' E; it is within a temperate climate region. Climate data were extracted from the Korea Meteorological Administration, and mean monthly temperatures were calculated (Table 1). According to the monthly average temperature, the seasons were divided into 3 groups: hot (June, July, August, and September), intermediate (April, May, October, and November), and cold (January, February, March, and December) seasons.

Table 1.

Monthly average temperature in South Korea from 2012 to 2016

| Year | Temperature (°C) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 2012 | -1.2 | -0.8 | 5.7 | 12.6 | 18.3 | 22.1 | 25.5 | 26.4 | 20.2 | 14.3 | 6.6 | -1.7 |

| 2012 | -1.2 | -0.8 | 5.7 | 12.6 | 18.3 | 22.1 | 25.5 | 26.4 | 20.2 | 14.3 | 6.6 | -1.7 |

| 2013 | -2.1 | 0.7 | 6.6 | 10.3 | 17.8 | 22.6 | 26.3 | 27.3 | 21.2 | 15.4 | 7.1 | 1.5 |

| 2014 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 7.7 | 13.4 | 18.4 | 21.9 | 25.1 | 23.8 | 20.9 | 14.8 | 8.8 | -0.5 |

| 2015 | 0.5 | 2 | 6.7 | 12.7 | 18.6 | 21.7 | 24.4 | 25.2 | 20.5 | 15 | 10.1 | 3.5 |

| 2016 | -0.9 | 1.7 | 7.2 | 13.8 | 18.6 | 22.3 | 25.4 | 26.7 | 21.6 | 15.8 | 7.8 | 3.1 |

| Totala) | -0.6 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 0.7 | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 18.3 ± 0.3 | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 25.3 ± 0.6 | 25.9 ± 1.2 | 20.9 ± 0.5 | 15.6 ± 0.5 | 8.1 ± 1.3 | 1.2 ± 2.0 |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

3. Definition of OAB

All available OAB drugs in Korea such as fesoterodine, imidafenacin, mirabegron, oxybutynin, propiverine, solifenacin, tolterodine, and trospium were included (Supplementary Table 1). OAB-DPR was calculated as the number of patients who were prescribed OAB drug among all patients during a certain period. The overall prescription rate was calculated, followed by the prescription rate according to the age and seasonal group.

4. Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used to investigate the association between OAB-DPR and seasonal variation. Logistic regression was used to assess the effect of each season on OAB-DPR, and odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 25.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

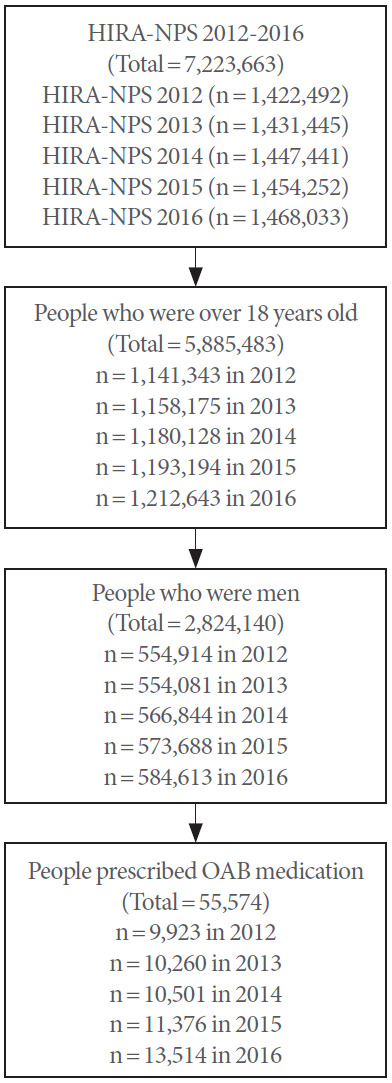

Of the total 7,223,663 people, 5,885,483 (81.48%) were aged over 18 years. Among them, 2,824,158 (47.99%) were men, and their mean age was 45.8±16.4. A total of 55,574 men (1.97%) were prescribed OAB drug once between 2012 and 2016, and their mean age was 62.4±15.3 (Fig. 1). OAB-DPR by age group was 0.38% in those under 30 years, 0.63% in those in their 30s, 0.92% in those in their 40s, 1.74% in those in their 50s, 4.18% in those in their 60s, 7.55% in those in their 70s, and 9.69% in those over 80 years (Table 2). Thus, the prescription rate increased with age, with a steeper increase after 60 years of age (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Case extraction diagram. HIRA, Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; NPS, National Patient Sample; OAB, overactive bladder.

Table 2.

Drug prescription rate for OAB according to age decades

| Age (yr) | Total patients | Patient with OAB (%) | Chi-square value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 30s | 40s | 50s | 60s | 70s | |||

| < 30 | 542,804 | 2,043 (0.38) | ||||||

| 30–39 | 529,636 | 3,332 (0.63) | 339.9*** | |||||

| 40–49 | 593,346 | 5,476 (0.92) | 1,271.3*** | 310.4*** | ||||

| 50–59 | 563,157 | 9,782 (1.74) | 4,837.4*** | 2,825.5*** | 1,470.8*** | |||

| 60–69 | 335,422 | 14,025 (4.18) | 16,710.3*** | 13,179.2*** | 11,067.9*** | 4,869.6*** | ||

| 70–79 | 199,064 | 15,036 (7.55) | 33,355.8*** | 28,231.9*** | 25,987.7*** | 15,795.5*** | 2,762.7*** | |

| ≥ 80 | 60,711 | 5,880 (9.69) | 36,521.8*** | 29,080.7*** | 24,785.4*** | 14,146.0*** | 3,263.1*** | 285.6*** |

OAB, overactive bladder.

P<0.001 by Pearson chi-square test.

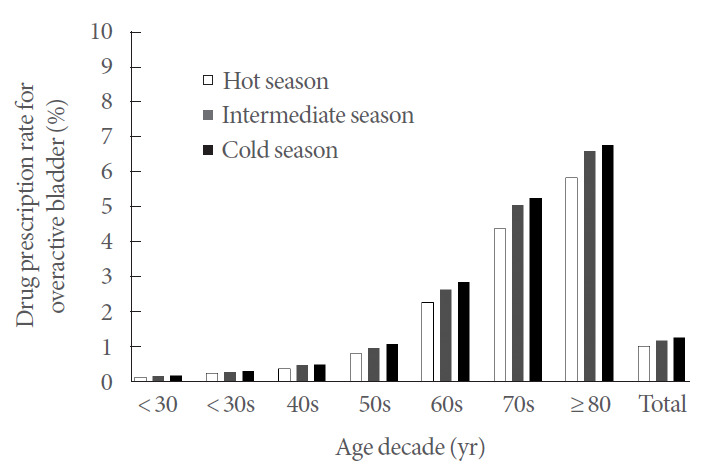

Fig. 2.

Drug prescription rate for overactive bladder in men according to seasons in each age decade.

In the present study, the seasons were divided into 3 groups as hot, intermediate, and cold seasons. The average temperatures were 23.6°C±2.3°C in the hot season, 13.5°C±4.0°C in the intermediate season, and 2.1°C±3.2°C in the cold season. There were significant differences in OAB-DPR among the seasonal groups, with the prescription rate being 1.02% (reference) in the hot season, 1.19% (OR, 1.170; 95% CI, 1.152–1.189) in the intermediate season, and 1.27% (OR, 1.244; 95% CI, 1.225–1.264) in the cold season (P<0.001) (Table 3). These seasonal variations persisted in the subgroup analysis of age decades (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Drug prescription rate for OAB according to the seasonal groups and age decades

| Age | Total patients | Season | Patients with OAB (%) | Logistic regression analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odd ratio | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

| Total | 2,824,141 | Hot | 28,849 (1.02) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 33,698 (1.19) | 1.170 | 1.152–1.189 | |||

| Cold | 35,802 (1.27) | 1.244 | 1.225–1.264 | |||

| < 30 | 542,804 | Hot | 754 (0.14) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 883 (0.16) | 1.171 | 1.063–1.291 | |||

| Cold | 975 (0.18) | 1.294 | 1.176–1.423 | |||

| 30s | 529,636 | Hot | 1,349 (0.25) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 1,549 (0.29) | 1.149 | 1.068–1.236 | |||

| Cold | 1,597 (0.30) | 1.184 | 1.101–1.274 | |||

| 40s | 593,346 | Hot | 2,258 (0.38) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 2,820 (0.48) | 1.250 | 1.183–1.321 | |||

| Cold | 2,944 (0.50) | 1.305 | 1.236–1.379 | |||

| 50s | 563,157 | Hot | 4,582 (0.81) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 5,494 (0.98) | 1.201 | 1.155–1.249 | |||

| Cold | 6,090 (1.08) | 1.333 | 1.282–1.385 | |||

| 60s | 335,422 | Hot | 7,628 (2.27) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 8,859 (2.64) | 1.166 | 1.130–1.202 | |||

| Cold | 9,588 (2.86) | 1.265 | 1.227–1.304 | |||

| 70s | 199,064 | Hot | 8,732 (4.39) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 10,082 (5.06) | 1.163 | 1.129–1.197 | |||

| Cold | 10,494 (5.27) | 1.213 | 1.178–1.249 | |||

| ≥ 80 | 60,711 | Hot | 3,546 (5.84) | Reference | < 0.001 | |

| Intermediate | 4,011 (6.61) | 1.140 | 1.088–1.195 | |||

| Cold | 4,114 (6.78) | 1.172 | 1.119–1.227 | |||

OAB, overactive bladder; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Seasons of the year exerts an influence on certain disease conditions, such as coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and respiratory disease [12-14]. Our study demonstrated that OAB-DPR also varies among seasons: Specifically, it was significantly higher in the cold season than in the hot season, suggesting that cold weather may develop and aggravate OAB symptoms in men. This seasonal variation was consistently observed in each age group. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first report to investigate the relationship between seasonal variation and OAB-DPR using a nationwide dataset. The presumptive explanation of this observation is as follows: the first is the response of the muscles to the cold stress. Cold stress increases sympathetic activity, which stimulates smooth muscle contraction in the prostate, and induces detrusor overactivity, which decreases voiding interval and volume [15,16]. The second is the change in diuresis with temperature. Diuresis is reduced by insensible fluid loss from sweating at high temperatures [17]. On the contrary, cold stress not only provokes peripheral vasoconstriction, which inhibits vasopressin secretion and leads to diuresis [18], but also stimulates the secretion of plasma atrial natriuretic peptide, which enhances diuresis [19]. The third is seasonal variation in vitamin D levels. Increasing evidence suggests that vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency is associated with LUTS [20]. Vitamin D status was found to be an independent significant predictor of OAB, with an increase of OAB risk by 44 times in patients with severe vitamin D deficiency [21]. The incidence of vitamin D deficiency was significantly higher during the winter than the summer [22,23]. These results suggest that seasonal changes in vitamin D influence seasonal OAB development.

In previous studies, seasonal variation was more pronounced in storage symptoms than in voiding symptoms (Table 4) [5-7]. The Japanese Urological Association recommends conservative treatment in which men with LUTS avoid exposing their lower body to cold temperatures [24]. A large retrospective study by Choi et al. [6] demonstrated that symptom severity as measured using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) was worse in the cold season group than in the hot season group. Storage symptom scores were significantly worse in the cold, and the QoL score showed a significant difference between the cold and hot seasons. In uroflowmetric parameters, voided volume and postvoid residue exhibited a significant seasonal change, but there was no significant difference in Qmax. Kobayashi et al. [7] announced that nocturia had seasonal variation in patients with BPH; however, there were no seasonal variation in the other IPSS categories and uroflowmetric parameters. Yoshimura et al. [5] performed a large community-based questionnaire study in Japan including 3 towns (Tobetsu at higher latitude [43°N], Kumiyama at middle latitude [35°N], and Sashiki at lower latitude [26°N]) and reported that 3 storage symptoms (frequency, urgency, and nocturia) demonstrated significant differences between summer and winter; such a difference was observed in relatively low latitude areas (Kumiyama and Sashiki) but not in higher latitude areas (Tobetsu). Likewise, a prospective study performed in Edinburgh, United Kingdom, showed no seasonal variation in urinary symptoms and uroflowmetric parameters [8]. Edinburgh is located at a relatively high latitude (55°N). These findings suggested that climate can influence seasonal variations in LUTS. Watanabe et al. [9] also explored changes in IPSS and uroflowmetric parameters associated with seasonal changes in 31 men with LUTS and found no significant seasonal change in IPSS or QoL but reported that Qmax exhibited a significant seasonal change, unlikely to expectation, being higher in the winter than in the summer. The authors mentioned that indoor temperatures in the winter were higher than outdoor temperatures due to central heating, whereas indoor temperatures in the summer were lower due to air-conditioning. However, the number of subjects was too small to draw concrete results.

Table 4.

Characteristics of previously published studies and the present study comparing urinary symptoms according to seasons

| Study | Study design | Subjects (n) | Age (yr) | Measures | Location | Season (mo) | Average temperature (°C) | Seasonal variation of urinary symptoms | Seasonal variation of uroflowmetric parameter | Seasonal variation of QoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watanabe, 2007 [9] | Prospective, hospital-based | Male patients with BPH/LUTS (31) | 74.5 ± 6.8 | IPSS | Hamamatsu, Japan (34° E, 137° N) | Hot (Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep) | >20 | No | Yes (Qmax) | No |

| QoL score | Comfortable (Apr, May, Oct, Nov) | 10–20 | ||||||||

| Uroflowmetry | Cold (Jan, Feb, May, Dec) | <10 | ||||||||

| Yoshimura et al. 2007 [5] | Prospective, community-based | Residents aged 41–70 yr | 56.7 ± 7.9 | IPSS | Tobetsu, Japan (141° E, 43° N) | Summer (Jun, Jul, Aug) | 20.4 | No | NA | NA |

| -Male (1,066) | ICIQSF | Winter (Jan, Feb) | 4.4 | |||||||

| -Female (1,214) | Kumiyama, Japan (136° E, 35° N) | Summer (Jun, Jul, Aug) | 27.5 | Yes (frequency, urgency) | NA | NA | ||||

| Winter (Jan, Feb) | 4.7 | |||||||||

| Sashiki, Japan (128° E, 26° N) | Summer (Jun, Jul, Aug) | 27.3 | Yes (frequency, urgency, nocturia) | NA | NA | |||||

| Winter (Jan, Feb) | 16.3 | |||||||||

| Cartwright et al. 2014 [8] | Prospective, hospital-based | Male patients with LUTS (296) | 62.3 | IPSS | Edinburgh, UK (3° E, 55° N) | Spring (Mar, Apr, May) | 8.1±2.2a) | No | No | No |

| QoL score | Summer (Jun, Jul, Aug) | 14.6±1.2a) | ||||||||

| Uroflowmetry | Autumn (Sep, Oct, Nov) | 9.9±2.7a) | ||||||||

| Winter (Jan, Feb, Dec) | 4.1±1.0a) | |||||||||

| Choi et al. 2015 [6] | Retrospective, hospital-based | Male patients with BPH/LUTS (1,185) | 62.1 ± 9.9 | IPSS | South Korea (124-130° E, 33-39° N) | Hot (Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep) | 24.0±2.6 | Yes (storage symptoms) | Yes (voided vol., residual vol.) | Yes |

| QoL score | Intermediate (Apr, May, Oct, Nov) | 12.8±4.3 | ||||||||

| Uroflowmetry | Cold (Jan, Feb, May, Dec) | 1.0 ±3.2 | ||||||||

| Kobayashi et al. 2017 [7] | Prospective, hospital-based | BPH patients with alpha blocker, over 50 years (146) | 70.9 ± 7.6 | IPSS | Utsunomiya, Japan (139° E, 36° N) | Summer (Jun, Jul, Aug) | 24.2±2.0 | Yes (nocturia) | NA | No |

| OABSS | Winter (Jan, Feb, Dec) | 3.9±1.5 | ||||||||

| QoL score | ||||||||||

| Present study, 2019 | Retrospective, papulation-based | Men over 18 years old (2,824,140) | 45.8 ± 16.4 | Drug prescription rate for OAB | South Korea (124-130° E, 33-39° N) | Hot (Jun, Jul, Aug, Sep) | 23.6±2.3 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Intermediate (Apr, May, Oct, Nov) | 13.5±4.0 | |||||||||

| Cold (Jan, Feb, May, Dec) | 2.1±3.2 |

BPH, benign prostate hyperplasia; ICIQS, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire short form; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; NA, not available; OAB, overactive bladder; QoL, quality of life; Qmax, maximum flow rate; UK, United Kingdom.

These data were calculated by extracting values from the graph of the paper.

Shim et al. [4] conducted a cross-sectional survey to investigate the association between daily temperature and LUTS in men and found that it was not affected by average daily temperature but was affected by diurnal temperature variations. Goriunov and Davidov [25] reported that the frequency of acute urinary retention (AUR) was affected by day-to-day temperature fluctuations (≥5°C) or a change in the atmospheric pressure (≥9 hPa) and humidity (≥20%). They studied the effect of daily temperature variations on LUTS or AUR and found that daily temperature variations did not reflect seasonal variations in weather because seasonal changes include not only changes in temperature but also those in other climatic factors such as humidity and total sunshine. Keller at al. [26] demonstrated that AUR was negatively correlated with ambient temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall and significantly correlated with hours of sunshine and atmospheric pressure.

In a large cross-sectional, population-based study in Korea, questionnaire-based OAB prevalence was 2.9% [27], but most studies reported 10%–20% OAB prevalence [2,28,29]. Such discrepancy can be explained by the differences in OAB definition, survey questionnaires for OAB, survey methods, and characteristics of the study populations. In our study, OAB-DPR was 1.97%. The prescription rate may differ from those prevalence rates surveyed, because our study was based on OAB-DPR, not on the diagnosis of OAB. This might be a limitation of our study, but it suggests that a significant number of patients with OAB symptoms require medical help. This study also had other limitations. First, since HIRA-NPS is not longitudinal database, it was impossible to obtain prior history of OAB diagnosis or OAB drug medication. This study did not include detailed clinical data on other comorbidities that could affect OAB. Second, the present study was based on OAB-DPR, not on the diagnosis of OAB. Third, the study year might be an important variable, but there was no difference in seasonal variation for each year (data not shown). Fourth, we performed the analysis using only the monthly average temperature of the country instead of using the temperatures corresponding to actual locations of the patients’ residences, although the range of latitude is relatively small in Korea. Despite these limitations, our study demonstrated that seasonal variation affects OAB-DPR, suggesting that seasonal changes can affect development of OAB symptoms that require medication.

In conclusions, OAB-DPR was affected by seasons, being significantly higher in the cold season than in the hot season. This suggests that cold weather may affect development and aggravation of OAB symptoms in men. Therefore, it may be helpful to consider seasonal changes when managing patients with OAB symptoms.

Footnotes

Research Ethics

The present study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Gangnam Severance Hospital (IRB No. 3-2019-0340). Informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Conflict of Interest

Mr. Jae Hwan Kim and Ms. So Jeong Park are researchers of the Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea, but they made no influence on this work in relation with the company or its products. Other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT

·Conceptualization: SKK

·Formal Analysis: JYB, HKP

·Investigation: JYB, HKP

·Methodology: JYB, HKP

·Project Administration: JYB

·Writing – Original Draft: SKK

·Writing – Review & Editing: SKK

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 1 can be found via https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2040030.015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trinh H, Irish V, Diaz M, Atiemo H. Outcomes of intradetrusor onabotulinum toxin A therapy in overactive bladder refractory to sacral neuromodulation. Int Neurourol J. 2019;23:226–33. doi: 10.5213/inj.1938030.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stensland KD, Sluis B, Vance J, Schober JP, MacLachlan LS, Mourtzinos AP. Predictors of nerve stimulator success in patients with overactive bladder. Int Neurourol J. 2018;22:206–11. doi: 10.5213/inj.1836094.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Son YJ, Kwon BE. Overactive bladder is a distress symptom in heart failure. Int Neurourol J. 2018;22:77–82. doi: 10.5213/inj.1836120.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shim SR, Kim JH, Won JH, Song ES, Song YS. Association between ambient temperature and lower urinary tract symptoms: a community-based survey. Int Braz J Urol. 2016;42:521–30. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshimura K, Kamoto T, Tsukamoto T, Oshiro K, Kinukawa N, Ogawa O. Seasonal alterations in nocturia and other storage symptoms in three Japanese communities. Urology. 2007;69:864–70. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi HC, Kwon JK, Lee JY, Han JH, Jung HD, Cho KS. Seasonal variation of urinary symptoms in Korean men with lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Mens Health. 2015;33:81–7. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2015.33.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi M, Nukui A, Kamai T. Seasonal changes in lower urinary tract symptoms in Japanese men with benign prostatic hyperplasia treated with alpha1-blockers. Int Neurourol J. 2017;21:197–203. doi: 10.5213/inj.1734830.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright R, Mariappan P, Turner KJ, Stewart LH, Rajan P. Is there seasonal variation in symptom severity, uroflowmetry and frequency-volume chart parameters in men with lower urinary tract symptoms? Scott Med J. 2014;59:162–6. doi: 10.1177/0036933014542393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe T, Maruyama S, Maruyama Y, Kageyama S, Shinbo H, Otsuka A, et al. Seasonal changes in symptom score and uroflowmetry in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2007;41:521–6. doi: 10.1080/00365590701485921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tae BS, Park TY, Jeon BJ, Chung H, Lee YH, Park JY, et al. Seasonal variation of overactive bladder symptoms in female patients. Int Neurourol J. 2019;23:334–40. doi: 10.5213/inj.1938078.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim L, Kim JA, Kim S. A guide for the utilization of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service National Patient Samples. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014008. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Becker RC, Gore JM. Seasonal distribution of acute myocardial infarction in the second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1226–33. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inagawa T, Shibukawa M, Inokuchi F, Tokuda Y, Okada Y, Okada K. Primary intracerebral and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in Izumo City, Japan. Part II: management and surgical outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:967–75. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakaji S, Parodi S, Fontana V, Umeda T, Suzuki K, Sakamoto J, et al. Seasonal changes in mortality rates from main causes of death in Japan (1970--1999) Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:905–13. doi: 10.1007/s10654-004-4695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roehrborn CG, Schwinn DA. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors and their inhibitors in lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;171:1029–35. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000097026.43866.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeBlanc J. Mechanisms of adaptation to cold. Int J Sports Med. 1992;13 Suppl 1:S169–72. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohn D, Flatau E. Points: why does cold weather cause frequency of micturition in some elderly people? Br Med J. 1980;281:875. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stocks JM, Taylor NA, Tipton MJ, Greenleaf JE. Human physiological responses to cold exposure. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2004;75:444–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassi J, Rintamaki H, Ruskoaho H, Leppaluoto J, Vuolteenaho O. Plasma levels of endothelin-1 and atrial natriuretic peptide in men during a 2-hour stay in a cold room. Acta Physiol Scand. 1991;142:481–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker-Autry CY, Burgio KL, Richter HE. Vitamin D status: a review with implications for the pelvic floor. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:1517–26. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1710-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdul-Razzak KK, Alshogran OY, Altawalbeh SM, Al-Ghalayini IF, Al-Ghazo MA, Alazab RS, et al. Overactive bladder and associated psychological symptoms: a possible link to vitamin D and calcium. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:1160–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.23975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sim MY, Kim SH, Kim KM. Seasonal variations and correlations between vitamin D and total testosterone levels. Korean J Fam Med. 2017;38:270–5. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2017.38.5.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eloi M, Horvath DV, Szejnfeld VL, Ortega JC, Rocha DA, Szejnfeld J, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and seasonal variation over the years in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:3449–56. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3670-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homma Y, Araki I, Igawa Y, Ozono S, Gotoh M, Yamanishi T, et al. Clinical guideline for male lower urinary tract symptoms. Int J Urol. 2009;16:775–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goriunov VG, Davidov MI. [The effect of meteorological factors on the incidence of acute urinary retention] Urol Nefrol (Mosk) 1996;(1):4–7. Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller JJ, Lin CC, Chen CS, Chen YK, Lin HC. Monthly variation in acute urinary retention incidence among patients with benign prostatic enlargement in Taiwan. J Androl. 2012;33:1239–44. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.112.016733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SY, Bang W, Choi HG. Analysis of the prevalence and associated factors of overactive bladder in adult Korean men. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, Roberts RG, Thuroff J, Wein AJ. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee YS, Lee KS, Jung JH, Han DH, Oh SJ, Seo JT, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, and lower urinary tract symptoms: results of Korean EPIC study. World J Urol. 2011;29:185–90. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.