Tuberculosis (TB) is an old disease with an impressive history of persistent human affliction throughout time. Previous approaches to harness the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb), the causative agent of TB, have been largely ineffective at reducing the global burden of TB. Among the new cellular players in bacterial immunity are mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells. In a recent study published in Mucosal Immunology1, Sakai et al. examined the MAIT cell response to M. tb and tested pre-infection (vaccination) or post-infection (therapeutic) MAIT cell boosting regimens to enhance M. tb clearance in a mouse model. Surprisingly, the authors observed that the timing of the boosted MAIT cell response resulted in profoundly different outcomes for M. tb immunity.

Historically, TB was commonly referred to as “consumption”, from the ancient Greek “Phthisis”, describing the nature of a characteristic “wasting disease”. Improvements in public health and later the emergence of effective antibiotics dramatically reduced the presence of “consumption” in the developed world. Despite these successes, M. tb infections remain the leading cause of mortality from an infectious agent. Moreover, M. tb is highly prevalent, infecting approximately one quarter of all humans, particularly in the developing world, where a further ten million diagnoses are made each year. The only vaccine approved for prevention of TB is Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), a live, attenuated preparation of Mycobacterium bovis which has variable efficacy in humans. Attempts to develop an alternative to the BCG vaccine have been met with criticism for lacking diversity and stagnant development pipelines2. It is clear that immunity to mycobacterial diseases, including TB, is still poorly understood. While drug therapy remains the gold standard treatment for TB, the emergence of drug-resistant M. tb has made it increasingly challenging to treat. Thus, renewed effort to resolve the remaining mysteries in our understanding of mycobacterial immunity, described in part for MAIT cells by Sakai et al., may lead us to more informed vaccine design and bring us a step closer to reducing the burden of M. tb infection globally.

MAIT cells are a subset of unconventional T cells that recognise small molecule antigens presented by the evolutionarily conserved and monomorphic major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I)-like molecule; MHC-I related protein 1 (MR1). In humans, MAIT cells are highly abundant, representing ~3% of blood T cells and can be found throughout the peripheral organs3. MAIT cells are also present, albeit at lower frequencies, in mice and other mammals. The prototypical antigen recognised by MAIT cells is 5-(2-oxopropylideneamino)-6-D-ribitylaminouracil (5-OP-RU), an intermediary metabolite produced during riboflavin biosynthesis of bacteria and fungi, including M. tb. MAIT cells are multi-faceted in their functional response to infections and in maintaining homeostasis, also contributing to tissue repair and wound healing3. In the context of M. tb, human blood MAIT cell frequencies are reportedly reduced during active infection4, suggestive of circulating MAIT cell migration into the tissues, although a recent large cohort study disputes this finding5. Human MAIT cells also secrete interferon gamma (IFNγ) when cultured with M. tb-infected antigen presenting cells4. Similarly, in mice, MAIT T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic cells secrete IFNγ in response to BCG and can inhibit its intracellular growth6. Moreover, MAIT cells have been shown to offer protective immunity against other respiratory pathogens such as Legionella longbeachae and Francisella tularensis3. These studies demonstrate that MAIT cells are active during M. tb infection and can be protective in mouse models of respiratory disease, supporting investigation of MAIT cells as a target for vaccination.

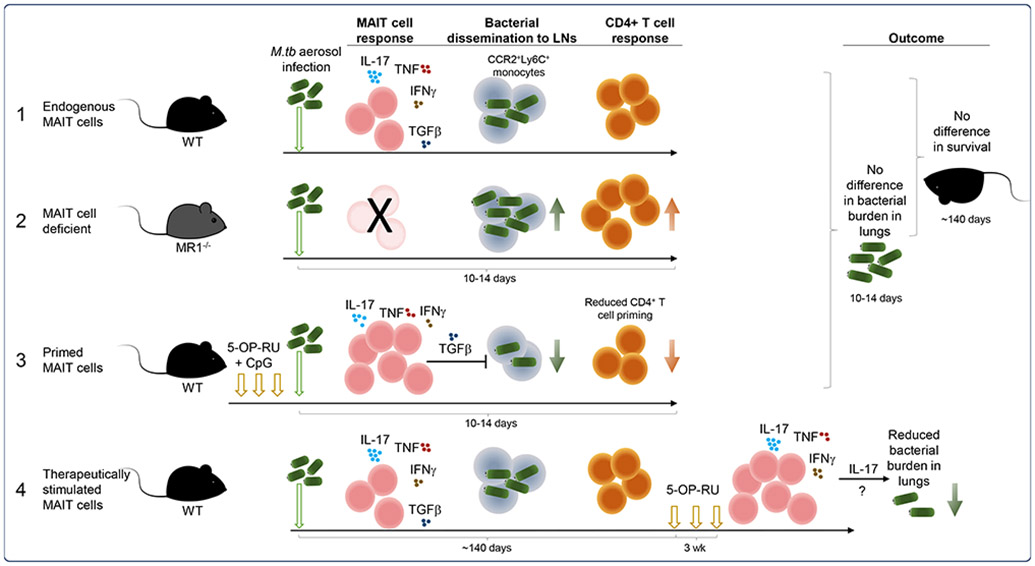

In the present study, Sakai et al. first examined the endogenous MAIT cell response to M. tb infection without intervention (Figure 1, panel 1). A modest increase in activated MAIT cells was observed in the lungs after infection, largely by recruitment from the circulation, and these MAIT cells expressed primarily a T helper (Th)17 dominant phenotype (also known as MAIT17). However, despite generating a MAIT cell response, there was no difference in survival between wild type mice and MAIT cell deficient, MR1 knockout (MR1−/−) mice (Figure 1, panel 2), suggesting the endogenous MAIT cell response did not contribute appreciably to M. tb resistance. Given what we have learnt in recent years about the role of MAIT cells in clearing other bacterial infections, this is perhaps not surprising; previous studies have shown only moderate contributions to the control of other bacterial pathogens in the presence of a complete fully-functioning immune system7.

Figure 1.

Summary of MAIT cell prophylactic and therapeutic vaccination schemes tested by Sakai et al. in mouse models of M. tb infection together with the outcomes and observations. 5-OP-RU; 5-(2-oxopropylideneamino)-6-D-ribitylaminouracil.

Previous work using a MAIT TCR (Vα19i-Tg) transgenic mouse model, in which a high proportion of T cells have a MAIT-like phenotype, showed that MAIT TCR+ T cells were recruited to the lungs after BCG or M. tb infection and provided some early protection from bacterial growth8. Thus, where MAIT cells constitute the majority of responding cells, they may play a more apparent role in clearing bacterial load. To test whether the endogenous MAIT cell response could be enhanced prior to infection, mice were vaccinated by administration of 5-OP-RU antigen combined with CpG adjuvant into the lungs (Figure 1, panel 3). This approach has been used previously to enhance MAIT cell responses to other respiratory pathogens and is likely driven by local expansion of MAIT cells at the site of vaccination7, 9. Unlike those studies, the M. tb bacterial burden in the lungs was not reduced by vaccination, even though the absolute number of MAIT cells increased significantly after vaccination. However, the authors found that the bacterial load in the lung-draining mediastinal lymph nodes (mLNs), the site of CD4+ T cell priming, was significantly reduced in vaccinated mice. This was also associated with reduced proliferation and a lower frequency of M. tb-specific CD4+ T cells in the mLNs. Thus, the presence of MAIT cells can exert negative effects on the generation of other arms of the immune response. This is consistent with the recent finding that MAIT cells were shown to express genetic signatures associated with immunoregulatory functions10.

To explore this further, the authors investigated whether an immunoregulatory function of MAIT cells was responsible for the delay in CD4+ T cell priming. Specifically, lung MAIT cells from both naïve and vaccine-primed mice expressed high levels of the regulatory cytokine transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and, using neutralising antibodies, the authors showed that TGF-β was partially responsible for the decrease in bacterial load and CD4+ T cell frequency observed in the mLN of vaccinated mice (Figure 1, panel 3).

Together, the authors showed that while vaccination primed MAIT cells did not directly provide resistance to M. tb infection, MAIT cell secretion of TGF-β was important for retaining CCR2+Ly6C+ monocytes in the lungs, likely preventing bacterial dissemination and subsequent conventional T cell priming. This is an intriguing result, which contrasts with previous findings in a murine model of F. tularensis infection where MAIT cells, through secretion of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, promoted CCR2+Ly6C+ monocyte differentiation into dendritic cells, assisting downstream CD4+ T cell priming and recruitment to the lungs11. Similarly, an increase in primed MAIT cells migrating to infected tissue in a model of chronic gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori was accompanied by faster recruitment of non-MAIT T cells and other immune cells, when compared to MR1−/− mice3.

Mycobacterium tb often occurs as a chronic or latent infection, which can then develop into active disease, particularly in immune-compromised individuals. Moreover, there is variable effectiveness of BCG vaccination in preventing TB disease in adults12. Thus, to assess their therapeutic potential, the authors examined the effect of stimulating MAIT cells during chronic M. tb infection (Figure 1, panel 4). As expected, the frequency of MAIT cells in the lungs increased significantly when 5-OP-RU was administered ~140 days post-infection. Most excitingly, after three weeks of 5-OP-RU therapy, the bacterial load in the lungs of infected mice decreased markedly.

Intriguingly, endogenous, vaccine-primed and therapeutically boosted MAIT cells all had a MAIT17 dominant response, but this profile only appeared to be beneficial in clearing bacteria during chronic infection. This was in contrast to a previous study whereby MAIT-like Vα19i-Tg cells expressed a different cytokine profile, secreting proportionally more IFNγ and granzyme B when activated in vitro8. Hence, the nature of the MAIT cell immune response might matter in controlling M. tb infection, and certain functional responses may be favourable or not, depending on the timing.

Previous work, using a different approach, has shown that in the absence of other arms of the immune system, MAIT cells can afford a level of protection against L. longbeachae infection, and this was dependent on IFNγ7. In contrast, this study showed that the MAIT cell contribution after therapeutic priming was IL-17 dependent, despite their IL-17 production having no evident benefit during acute infection. This apparent contradiction may be due to differently primed MAIT cells due to changes in the tissue microenvironment. MAIT cells can be activated directly by cytokines in a TCR-independent manner, and this mode of MAIT cell activation has been observed in both human and mouse responses to BCG infection8, 13. Additionally, cytokines are known to contribute to the quality of MAIT cell activation. Differences may also be explained by the experimental set-up. In the study by Wang et al., it was reasoned that bacterial pathogens cause more serious disease in immune compromised individuals, and an immune compromised mouse system was used. Indeed, 90% of persons infected with M. tb remain healthy, whereas in the context of coinfection with HIV and depletion of CD4+ T cells, infection is associated with rapid disease progression. Thus, MAIT cells may provide different contributions to the immune response depending on the context. The infecting pathogen, the broader immune response and the tissue microenvironment are all vital to the outcome when MAIT-priming is employed.

MAIT cells contribute to protective immunity against multiple bacterial pathogens3. They are highly conserved across evolution and target a metabolic process that is essential for many microbes; riboflavin biosynthesis. It is possible that these attributes will support vaccination regimens designed to prime MAIT cells for protective immunity. There is even the possibility that MAIT cell immunity might resist microbial immune evasion, analogous to the development of drug resistance that is inherent with current drug therapies. The data presented by Sakai et al. also highlight a current conundrum – how to boost MAIT cells for greater protection whilst avoiding unwanted side effects. It appears from this study that a precisely co-ordinated response of MAIT cells and other T cells may be vital to a beneficial effect. The study offers promise that by understanding the interactions with other cell types, precise MAIT cell targeted regimens may be developed in a new approach to combat an ancient pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are supported by research grants from The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1113293, 1125493) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01AI148407). AJC is supported by a Future Fellowship (FT160100083) from the Australian Research Council (ARC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NHMRC or ARC.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sakai S, Kauffman KD, Oh S, Nelson CE, Barry CE 3rd, Barber DL. MAIT cell-directed therapy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Mucosal Immunol 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-0332-4. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voss G, Casimiro D, Neyrolles O, et al. Progress and challenges in TB vaccine development. F1000Res 2018; 7: 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Provine NM, Klenerman P. MAIT Cells in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2020; 38: 203–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold MC, Cerri S, Smyk-Pearson S, et al. Human mucosal associated invariant T cells detect bacterially infected cells. PLoS Biol 2010; 8: e1000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suliman S, Gela A, Mendelsohn SC, et al. Peripheral Blood Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells in Tuberculosis Patients and Healthy Mycobacterium tuberculosis-Exposed Controls. J Infect Dis 2020; 222: 995–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua WJ, Truscott SM, Eickhoff CS, Blazevic A, Hoft DF, Hansen TH. Polyclonal mucosa-associated invariant T cells have unique innate functions in bacterial infection. Infect Immun 2012; 80: 3256–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, D’Souza C, Lim XY, et al. MAIT cells protect against pulmonary Legionella longbeachae infection. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakala IG, Kjer-Nielsen L, Eickhoff CS, Wang X, Blazevic A, Liu L et al. Functional Heterogeneity and Antimycobacterial Effects of Mouse Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells Specific for Riboflavin Metabolites. J Immunol 2015; 195: 587–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu H, Yang A, Derrick S, et al. Artificially induced MAIT cells inhibit M. bovis BCG but not M. tuberculosis during in vivo pulmonary infection. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 13579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Constantinides MG, Link VM, Tamoutounour S, et al. MAIT cells are imprinted by the microbiota in early life and promote tissue repair. Science 2019; 366 (6464): eaax6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meierovics AI, Cowley SC. MAIT cells promote inflammatory monocyte differentiation into dendritic cells during pulmonary intracellular infection. J Exp Med 2016; 213: 2793–2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katelaris AL, Jackson C, Southern J, et al. Effectiveness of BCG Vaccination Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in Adults: A Cross-sectional Analysis of a UK-Based Cohort. J Infect Dis 2020; 221: 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suliman S, Murphy M, Musvosvi M, et al. MR1-Independent Activation of Human Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells by Mycobacteria. J Immunol 2019; 203: 2917–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]