Abstract

A 76-year-old Japanese man with a history of stomach cancer and chronic atrial fibrillation was referred to our department with left atrial thrombus. He had a history of gastric amyloidosis diagnosed by a pathological specimen of the stomach; however, further examination for amyloidosis was not performed. The patient displayed clinical signs and symptoms of heart failure and echocardiography showed a thick left ventricular wall. Since cardiac amyloidosis was suspected, the patient underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and 99mTc-pyrophosphate scintigraphy. These results are consistent with transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis). DNA analysis of transthyretin (TTR) was performed and a heterozygous Val122Ile mutation was identified. Notably, his only son requested the analysis; however, no mutations were noted. ATTR Val122Ile is one of the mutations in TTR that are associated with hereditary amyloidosis, causing severe cardiomyopathy. The prevalence of the ATTR Val122Ile mutation is 3.9% in the African-American population. However, the occurrence of this mutation in Asian populations is very rare. This is the second reported case of the ATTR Val122Ile variant in Japan and the first case tested including familial genes.

<Learning objective: Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR) Val122Ile variant is rare in Asian people. This is the second case of ATTR Val122Ile variant in Japan and the first case tested including familial genes. This case suggests this mutation is present even in Asian people. It is important to evaluate transthyretin gene mutations even in elderly ATTR cardiac amyloid without apparent family history of amyloidosis. If there is a gene mutation, it is necessary to search for transthyretin mutation within the family members.>

Keywords: Amyloid, Transthyretin, Val122Ile, Transthyretin amyloidosis, Heart failure

Introduction

Amyloidosis is caused by the deposition of misfolded proteins in various organs including the heart, leading to their dysfunction [1]. Transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR amyloidosis) is a heterogeneous disorder with various genotypes and heterogeneous phenotypes caused by transthyretin (TTR) gene mutations [2]. ATTR Val30Met is the most common amyloidogenic TTR variant, causing severe peripheral neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and cardiomyopathy [3]. Meanwhile, ATTR Val122Ile is one of more than 100 mutations in TTR that are associated with hereditary amyloidosis, causing severe cardiomyopathy. Retrospective studies have shown a prevalence of the ATTR Val122Ile mutation to be as high as 3.9% in African-Americans; however, the occurrence of this mutation in Asians is very rare [4].

Case Report

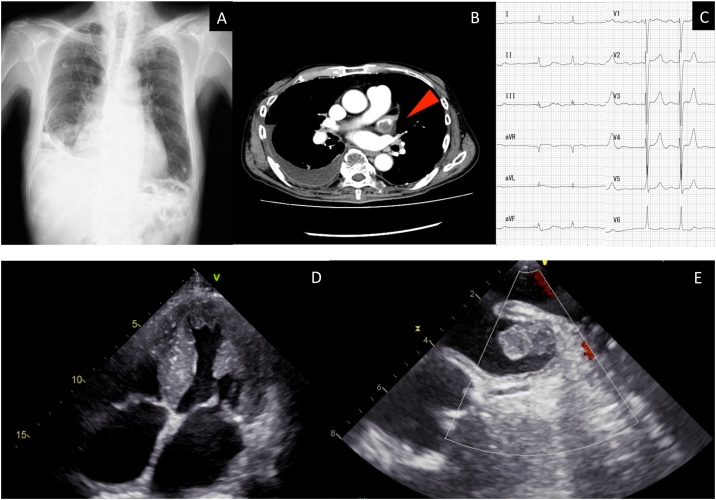

A 76-year-old Japanese man with a history of stomach cancer and chronic atrial fibrillation was referred to our department with left atrial thrombus. He had undergone partial gastrectomy for stage I stomach cancer three years previously. Notably, the pathological specimen of the stomach showed amyloidosis (Congo red stained biopsy showed amyloid deposits on lamina muscularis mucosae, with apple-green birefringence under polarized light); however, further examination had not been performed. Additionally, he had a 5-year history of chronic atrial fibrillation and was taking rivaroxaban. Nevertheless, the patient did not undergo echocardiography. A follow-up contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan for stomach cancer demonstrated a left atrial thrombus; thus, he visited our institution. The patient sometimes noticed dizziness when he stood up, and he displayed clinical signs and symptoms of heart failure (New York Heart Association grade III), presenting with dyspnea on exertion. He had never smoked cigarettes or consumed alcohol. He had no family history of cardiac disease or peripheral neuropathy. On presentation, his vital signs were stable (blood pressure = 100/74 mmHg, pulse = 80/min, body temperature = 35.8 °C, respiratory rate = 16/min, and oxygen saturation = 99%). However, the head up tilt test was positive with decreased blood pressure and an increased heart rate. The body mass index was 19.2 kg/m2 with no noticeable body weight changes. On physical examination, coarse crackles in the right lower lobe and peripheral pitting edema were observed; nevertheless, neurological deficits and the findings of peripheral neuropathy were not observed. Laboratory studies revealed findings of elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP; 551 pg/mL); however, gastric tumor markers including carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were within the normal range. Chest X-ray showed cardiac hypertrophy and right pleural effusion (Fig. 1A). A chest-abdominal contrast-enhanced CT showed a left atrial thrombus and right pleural effusion (Fig. 1B). Electrocardiography demonstrated atrial fibrillation with low voltage (Fig. 1C). He was admitted for further evaluation to achieve a definitive diagnosis and treatment for the thrombus.

Fig. 1.

(A) The chest radiograph taken upon admission. (B) The chest-abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography on admission. An arrow points to the left atrial thrombus. (C) The electrocardiogram on admission. (D) Transthoracic echocardiography showing left ventricular hypertrophy. (E) Transesophageal echocardiography revealed left atrial thrombus.

He denied withdrawing the anticoagulant medication and heparin was initiated. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a preserved left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction of 52%; however, significant LV wall thickening with an intraventricular septum at 16 mm and posterior wall at 15 mm (normal, <12 mm) were observed (Fig. 1D). Moreover, his left atrial dimension was dilated with 46.4 mm. Transesophageal echocardiography showed a 21.3 × 11.0 mm sized left atrium thrombus (Fig. 1E) The late diastolic emptying velocity of left atrial appendage (LAA) was 34 cm/s and the LAA filling velocity was 24 cm/s. Considering LV wall thickening and the history of amyloidosis, we suspected cardiac amyloidosis, which may lead to left atrial thrombus due to atrial dysfunction. Additional laboratory studies revealed findings of elevated serum amyloid A protein (49.8 μg/mL; normal range: < 8.0 μg/mL) and negative findings of Bence Jones Protein, free light chain, immunoelectrophoresis, protein C, protein S, and lupus anticoagulant.

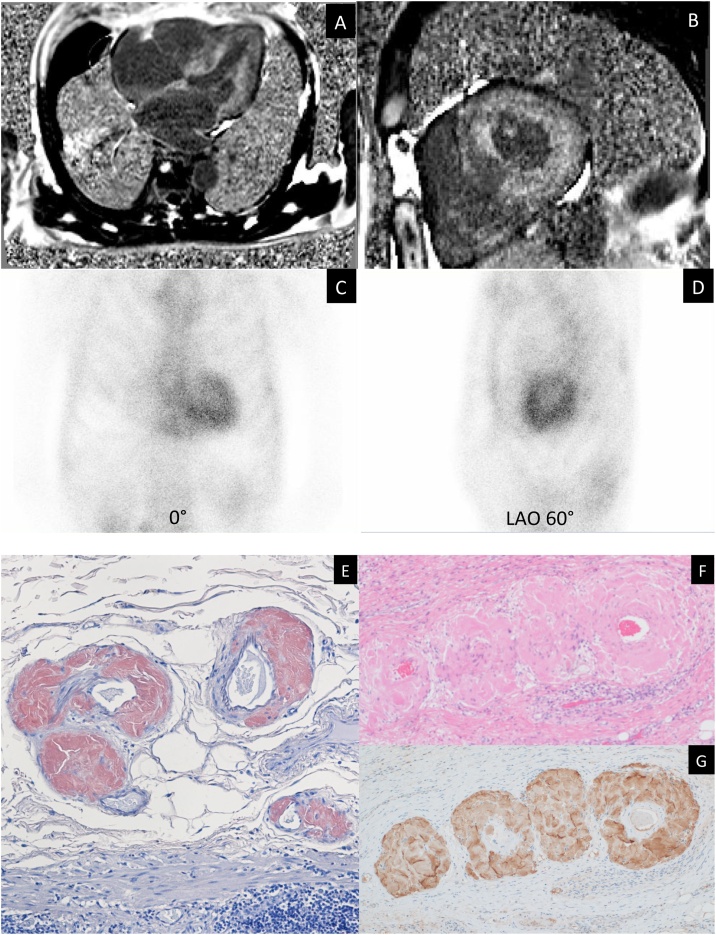

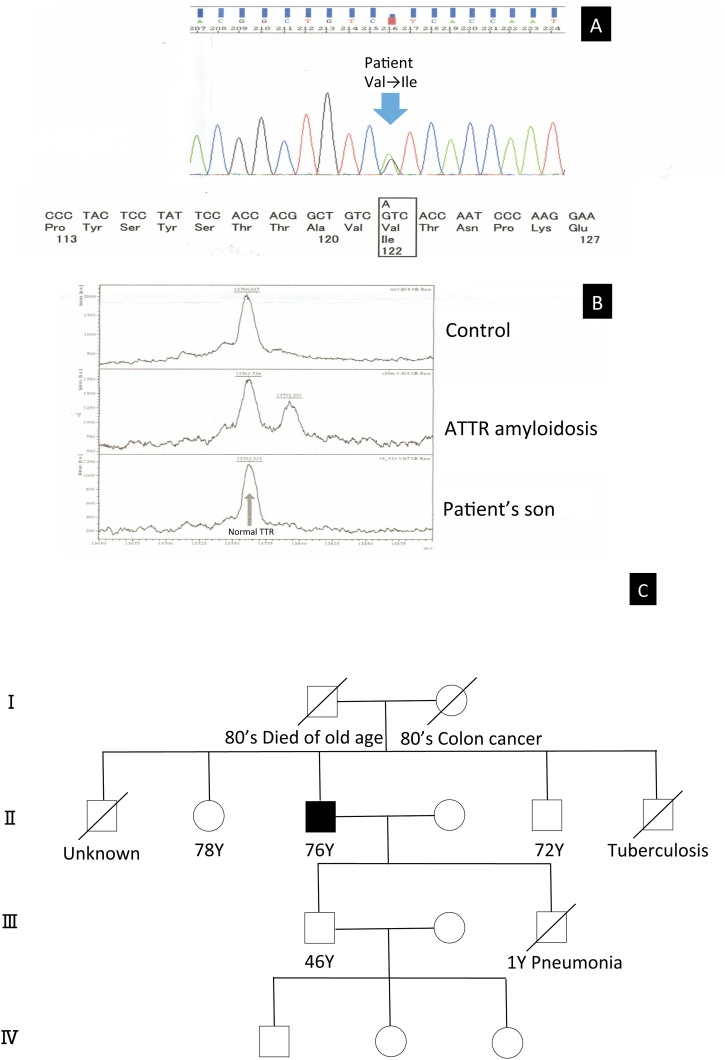

Coronary angiography revealed no significant coronary artery stenosis. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed diffuse sub-endocardial heterogeneous increased signal on delayed contrast-enhanced inversion recovery T1-weighted images (Fig. 2A and B). 99mTc-pyrophosphate (PYP) scintigraphy demonstrated diffuse intense 99mTc-PYP uptake in the myocardium of the left ventricle (Fig. 2C and D). Although he had no family history of amyloidosis, we suspected ATTR amyloidosis based on the findings of 99mTc-PYP scintigraphy. We performed immunohistochemistry for TTR by using residual tissue samples. On immunohistochemistry, the staining was positive for anti-TTR antiserum (Fig. 2E, F, and G). After obtaining informed consent, DNA analysis of TTR was performed and heterozygous Val122Ile mutation was identified (Fig. 3A). The patient had a 46-year-old son with no symptoms or medical history. Moreover, the analysis of the son’s DNA for TTR was performed after genetic counseling upon his request of the analysis; however, both mass spectrometry and genetic test showed normal TTR (Fig. 3B). The patient’s sister and brother denied undergoing the genetic test, however, they did not have any cardiac or neurological symptoms. In addition, his parents died from other than amyloidosis in their 80 s (Fig. 3C). Therefore, a definitive diagnosis of sporadic ATTR Val122Ile variant was made. Tafamidis was firstly not indicated for the patient when he was diagnosed with ATTR because he did not have any neurological deficits or peripheral neuropathy. However, the indication of tafamidis was extended to cardiomyopathy of wild-type or hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis in the course of treatment. Therefore, after the extension of indication, we explained tafamidis to the patient. However, the patient did not want to use tafamidis for the treatment because of financial problems, we continued general treatment for his heart failure using β-blockers and diuretics. Warfarin was initiated for the thrombus, but its control was difficult; thus, we changed the treatment to edoxaban and the size of thrombus was observed to shrink. He was admitted for deteriorated heart failure several times; he died one and half years after the initial diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis due to chronic heart failure.

Fig. 2.

(A, B) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse sub-endocardial heterogeneous increased signal on delayed contrast-enhanced inversion recovery T1-weighted images. (C, D) 99mTc-pyrophosphate scintigraphy showed increased isotope uptake in the left ventricle. (E) Congo red stained biopsy of stomach showed amyloid deposits on lamina muscularis mucosae (x40 magnification). (F) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (x100 magnification). (G) On immunohistochemistry, staining was positive for anti- transthyretin antiserum (x100 magnification).

Fig. 3.

(A) Substitution of Ile for Val at position 122 in TTR exon was noted in the DNA sequence analysis of transthyretin (TTR) in the patient. (B) The mass spectrometry showed normal TTR of the patient’s son. (C) The family tree of the patient.

ATTR, transthyretin amyloidosis.

Discussion

Yoshinaga et al. first described a Japanese case of the ATTR Val122Ile variant in 2017 [3]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second reported case of the ATTR Val122Ile variant in Japan and the first tested case including familial genes. This case was sporadic because his only son was negative for the TTR mutation. Although ATTR Val30Met is the most common amyloidogenic TTR variant, the ATTR Val122Ile variant is the most well-known cause of cardiac amyloidosis in African-American patients [5]. The clinical characteristics of Val122Ile are late-onset cardiomyopathy (generally occurring after 55 years of age) and are more common in men without neuropathy; additionally, this clinical phenotype is similar to that of senile systemic amyloidosis [2], [3]. Recently, the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey (THAOS) has reported that the genotypes and phenotypes of ATTR amyloids vary notably by country. It is also understood that four mutations including Val122Ile, Leu111Met, Thr60Ala, and Ile68Leu are associated with a mainly cardiac phenotype showing symmetric LV hypertrophy, normal diastolic LV dimensions and volume, and a mildly depressed LV ejection fraction [2]. THAOS also reported that the survival of patients with Val122Ile was not significantly different from that in wild-type ATTR cardiac amyloid patients from either registry enrollment or from the diagnosis, although patients with Val122Ile had worse New York Heart Association functional class, higher BNP levels, faster heart rates, and lower quality of life. In addition, the clinical differences between ATTR Val122Ile variant and wild-type ATTR cardiac amyloid among US subjects showed those with wild-type disease were older (76 years vs. 69 years at registry entry) and almost exclusively Caucasian (89.4%), whereas those with Val122Ile mutations were more often of African descent (86.8%). In both wild-type and Val122Ile, a higher percentage of subjects were male compared to female, but this was most marked in wild-type (97.4% vs. 75.8%). Cardiac symptoms such as palpitation, dizziness, heart failure, dyspnea and syncope, except for rhythm disturbances, did not differ between wild-type ATTR subjects and those with Val122Ile mutations. There was higher walking disability and more neurologic symptoms (neuropathic pain and tingling) in those with Val122Ile mutations than wild-type ATTR, although the absolute numbers were limited [6]. On the other hand, another study reported that the survival of Val122Ile patients (median survival: 47 months) was significantly shorter than that for wild-type ATTR patients (59 months, hazard ratio: 2.1; 95% confidence interval: 1.2 to 3.6) [7]. Our case was consistent with the clinical features of previously reported Val122Ile mutations in that the patient had late-onset cardiomyopathy without neuropathy and he had cardiac symptoms including dizziness, heart failure, dyspnea, and rhythm disturbance (atrial fibrillation). Although he died one and half years after the initial diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis, the total duration from the first diagnosis of amyloidosis was 54 months, which were not so different from the previously reported median survival time above.

In conclusion, although the ATTR Val122Ile variant is very rare in Asian people, this case suggests that this mutation is present even in Asian people. It is important to evaluate TTR gene mutations even in elderly ATTR cardiac amyloidosis without apparent family history of amyloidosis. Moreover, if there is a gene mutation, it is necessary to search for TTR mutations within the family members.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Taro Yamashita, MD of Kumamoto University Hospital, for contributing the genetic tests for diagnosing the TTR mutations. We are also grateful to Junichiro Ikeda, MD of Chiba University Hospital, and Masahiro Noro, MD of Matsudo City General Hospital, for their help for the pathological diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis.

References

- 1.Sridharan M., Highsmith We, Kurtin Pj, Zimmermann Mt, Theis Jd, Dasari S., Dingli D. A patient with hereditary ATTR and a novel AGel p.Ala578Pro amyloidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1678–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damy T., Kristen A.V., Suhr O.B., Maurer M.S., Plante-Bordeneuve V., Yu C.R., Ong M.-L., Coelho T., Rapezzi C., THAOS Investigators Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis in continental Western Europe: an insight through the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey (THAOS) Eur Heart J. 2019 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz173. ehz173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshinaga T., Yazaki M., Ohno M., Kodama S., Koyama J., Sekijima Y. Cardiac amyloidosis associated with amyloidogenic transthyretin V122I variant in an elderly Japanese woman. Circ J. 2017;81:893–894. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita T., Hamidi Asl K., Yazaki M., Benson M.D. A prospective evaluation of the transthyretin Ile122 allele frequency in an African-American population. Amyloid. 2005;12:127–130. doi: 10.1080/13506120500107162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson D.R., Pastore R.D., Yaghoubian R., Kane I., Gallo G., Buck F.S., Buxbaum J.N. Variant-sequence transthyretin (isoleucine 122) in late-onset cardiac amyloidosis in black Americans. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:466–473. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurer M.S., Hanna M., Grogan M., Dispenzieri A., Witteles R., Drachman B., Judge D.P., Lenihan D.J., Gottlieb S.S., Shah S.J., Steidley D.E., Ventura H., Murali S., Marc A Silver M.A., Jacoby D. Genotype and phenotype of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: THAOS (Transthyretin Amyloid Outcome Survey) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh A., Geller H.I., Falk R.H. Val122Ile mt-ATTR has a worse survival than wt-ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:757–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]