Abstract

Cardiac myxofibrosarcoma (MFS) is an uncommon entity. It is among the most challenging conditions to diagnose due to its rarity, high variability, and non-specific findings. These tumors often simulate left atrial myxoma or mitral stenosis at clinical presentation. Although, the definitive diagnosis of cardiac tumors depends on histopathological examination, various imaging techniques are also useful to study tumor characteristics to plan an appropriate treatment strategy. Here we highlight a case of primary cardiac MFS of left atrium (LA) showing areas of transition to undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) with bone or osteoid formation, which is extremely rare and not well described.

<Learning objective: Primary cardiac myxofibrosarcoma (MFS) is a rare and aggressive cardiac tumor. It is often confused with benign myxoma, leading to a delay in initiation of treatment. This delay can often lead to poor clinical outcomes. Our study will guide clinicians in early diagnosis, treatment, and counseling of patients with this rare entity. Echocardiography, together with magnetic resonance imaging, histology, and immunohistochemistry are essential in the diagnosis of MFS.>

Keywords: Myxofibrosarcoma, Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, Left atrial myxoma

Introduction

Primary cardiac tumors are rare and their incidence varies from 0.3% to 0.7% [1]. They are usually benign and only 25% are malignant. Primary cardiac sarcomas are even rarer with an incidence of 0.0001% in various autopsy series [2]. Angiosarcomas are the commonest accounting for about 33%–40%. Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS), pleomorphic sarcoma, and osteosarcoma are exceptionally rare primary cardiac tumors.

MFS is an aggressive soft tissue neoplasm. It is often asymptomatic with extensive local invasion or distant metastases at detection. Although, a total of 31 cases have been reported, one with bone/osteoid differentiation has not been described [3]. To the best of our knowledge this is one of few reported cases of high grade primary cardiac MFS with areas of woven bone or osteoid matrix formation in the medical literature. Here, we share our case experience and problems encountered during diagnosis and management of this extremely rare histological subtype of MFS.

Case report

A 62-year-old woman presented with the complaint of dyspnea on exertion (New York Heart Association class II) for the previous month. No significant past history was elicited. On examination, pulse was regular and blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg. On auscultation of chest, S1 was soft and S2 was normally split. There was an early diastolic plop sound after the S2 with a low pitched, mid-diastolic rumbling murmur (Grade II) over apex (mimicking mitral stenosis) without presystolic accentuation. The intensity of murmur changed in relation to patient's body position.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) was normal. X-ray of chest showed cardiomegaly. N-terminal (NT)-proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level was 120 pg/mL. Two-dimensional echocardiography (2D-ECHO) and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed a large mass measuring 4.8 × 3.5 cm almost filling the entire left atrium (LA). This mass was lobulated, sessile, having heterogenous echogenicity with areas of dense calcification and cystic degeneration, originating from posterior wall, and prolapsing into the left ventricular (LV) cavity during diastole (Fig. 1a, b). The mitral valve leaflets were thickened and mildly calcified. Mitral valve area was 3.5 cm2 by planimetry. Mean and peak gradient across mitral valve was 6 and 9 mmHg, respectively. LV ejection fraction was 55% with mild mitral regurgitation. No pulmonary hypertension was seen. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the above findings. It was reported as calcified LA myxoma. Coronary angiography (CAG) was normal. Open heart surgery was planned for the excision of LA mass.

Fig. 1.

(a) Transthoracic echocardiography. Parasternal long-axis view showing a large tumor in the left atrium (LA) (arrow) with calcification and prolapse. (b) Transesophageal echocardiography showing multi-lobulated mass (white arrows) arising from posterior wall of LA with areas of cystic degeneration (black arrow).

Surgical technique

After mid-line sternotomy and establishment of routine cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), right atrium (RA) was opened. LA was approached through the interatrial septum (IAS). A large pearly white, hard mass was seen arising from the posterior wall of LA. There was no involvement of mitral valve, pulmonary veins, atrial wall, or any extra cardiac structures (Fig. 2a). Surgical resection of the mass was achieved by blunt dissection. Mitral valve was inspected and found to be competent. IAS and RA were then closed. CPB was terminated, hemostasis achieved, and the sternotomy wound closed.

Fig. 2.

(a) Intraoperative image showing a large pearly white, hard mass arising from the posterior wall of left atrium (black arrow). (b) On excision, firm to hard, grayish white, nodular masses with cut surfaces having myxoid appearance interspersed with areas of dense calcification.

Due to presence of unusual findings such as appearance, size, and abnormal location, malignant or metastatic disease was also suspected. The tumor was sent for histopathological examination to confirm the diagnosis of LA myxoma. Meanwhile, the patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged on the 7th day post-surgery.

Histopathological examination

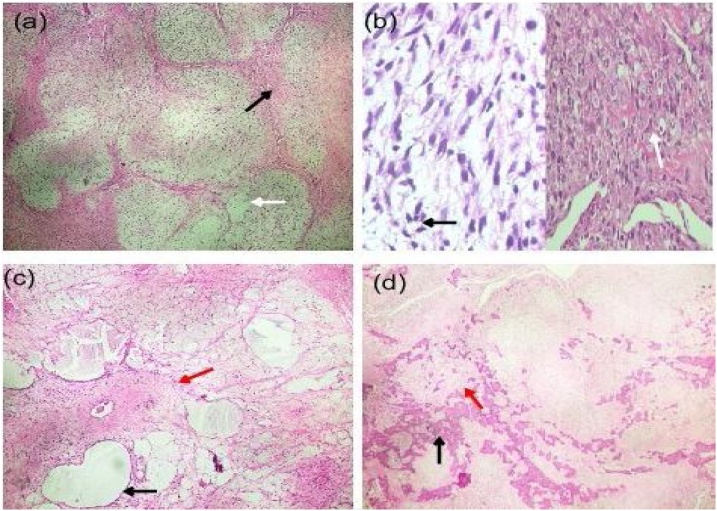

Gross examination of the tumor showed firm grayish white nodular soft tissue masses (47 g in total), with cut surface having myxoid appearance interspersed with areas of dense calcification, cystic degeneration, and necrosis. Microscopic examination of the tumor revealed hypocellular and hypercellular areas with nodular growth pattern and arborizing curvilinear blood vessels. Hypocellular areas were composed of few spindles to stellate-shaped cells and pseudolipoblasts. Hypercellular areas were composed of many pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei arranged in sheets and fascicles admixed with cells exhibiting epithelioid morphology. The stroma showed extensive myxoid changes (Fig. 3a–c) with islands of woven bone and osteoid intercepted by areas of hyalinization and dystrophic calcification. The tumor had brisk mitotic activity (2–3 cells/high power field) with atypical mitotic figures (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Histopathology of tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of tumor showing: (a) Nodular pattern with arborizing blood vessels (black arrow) and myxoid stroma (white arrow). (b) Hypercellular areas with pleomorphic spindle cells (black arrow) and epithelioid cells (white arrow). (c) Hypocellular areas with few scattered spindle cells within a predominant myxoid (black arrow) and fibrous stroma (red arrow). (d) Scattered areas of woven bone (black arrows) and osteoid deposition (red arrow).

Immunohistochemisty (IHC) was negative for calretinin, a marker expressed by most cardiac myxomas. IHC markers for vascular tumors such as cluster of differentiation 34 & 31 (CD34, CD31), smooth muscle actin (SMA), neurogenic tumors (S100), and sarcomatoid carcinoma (AE1/AE3) were also negative. IHC marker for vimentin was positive, which indicated that the tumor was of mesenchymal origin. The cellular proliferation marker (Ki-67) expression was high. It was reported as MFS of LA with areas of transition showing undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) and woven bone or osteoid deposition.

In view of the above diagnosis, 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan was done to assess the extent of the disease. It did not demonstrate any metastatic foci in the body confirming it as a primary cardiac tumor. Adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and radiation therapy was started. She is currently doing well.

Discussion

MFS is a rare soft tissue tumor, typically seen in adults in their sixth to eighth decade of life [4]. They are usually found in extremities (>77%), trunk (>12%), retroperitoneum or mediastinum (8%), and head (3%) [5]. About 80% of patients already have evidence of metastases at the time of the initial presentation, with lungs being the most common site. Indicators of poor prognosis include age ≥40 years, female sex, and tumor size ≥4 cm, high grade on histology, incomplete tumor excision, and patients not on any post-surgical treatment [3].

MFS may also arise in the heart with few reported cases in the medical literature. A study by Sun et al. [3] revealed that in a total of 31 cases, LA was found to be the most common location in 18 patients (58.1%). The second most common location was posterior wall of LA with pulmonary vein involvement in 5 patients (16.1%). Other locations included right side of the heart (ventricle, atrium, and pulmonary artery) in 5 (16.1%) and left ventricle in 3 patients (9.7%). None of these cases had osteoid or bony differentiation on histology, which truly makes our case a novel one. The symptoms of MFS are often confused with mitral stenosis or benign myxoma, since all of them can present with exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, easy fatigue, and pre-syncope, most likely due to the obstruction of the mitral valve orifice by the tumor mass, leading to reduced ventricular filling and cardiac output.

2D-ECHO and histopathological confirmation are mandatory for diagnosis. TEE and cardiac MRI can be helpful to study the location, dimension, and extension of the tumor. Primary cardiac MFS are usually large without a pedicle, calcified, multicentric, may attach to or invade the posterior atrial wall or less commonly, interatrial septum, pulmonary veins, or mitral valve apparatus. These features differentiate it from benign myxomas which are mainly attached to interatrial septum (∼83% of cases) [6], [7], [8].

MFS demonstrates a wide spectrum of cellularity and nuclear pleomorphism, but possess a characteristic pattern of curvilinear vascular arborization. Tumor may also have cells exhibiting differentiation along various lineages namely, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and histiocytes, but having neoplastic bone or osteoid elements is unusual. UPS is a diagnosis of exclusion. IHC study is important to rule out myogenic, melanocytic, neurogenic tumors, and sarcomatoid carcinomas.

Cardiac MFS is associated with average survival of ∼11 months. It is likely to present with local recurrences after surgery or distant metastasis. In a study by Sun et al. [3], the rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis after surgery were 42.9% and 19.0%, respectively. Complete resection of the tumor is ideal. Life expectancy is nearly twice as long in patients with complete tumor resection compared to incomplete excision [9].

Although surgery is still the first-line treatment for MFS, other treatment modalities such as adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or combination of both are also helpful. The role of heart transplantation as a treatment option is still controversial.

Conclusion

Primary cardiac MFS is a very rare tumor of the heart. It is often confused with benign myxoma, leading to delay in treatment and poor clinical outcomes. Early diagnosis will help in planning an effective treatment strategy. Various imaging techniques such as echocardiography and cardiac MRI, coupled with histology and immunohistochemistry play important roles in differentiating benign from malignant tumors. Due to the aggressive nature of this tumor, early detection and complete surgical resection may result in a longer survival. Adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy and radiation may delay local recurrences. Regular long-term follow-up with imaging is important to detect tumor recurrences.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to the patient for consenting to publish this case report. We are also grateful to Dr. Vidya Suratkal and her team and Dr. Namrata Kothari, Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai for their support during this study.

References

- 1.Leja M.J., Shah D.J., Reardon M.J. Primary cardiac tumors. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38:261–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kodali D., Seetharaman K. Primary cardiac angiosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2006;2006:39130. doi: 10.1155/SRCM/2006/39130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun D., Wu Y., Liu Y., Yang J. Primary cardiac myxofibrosarcoma: case report, literature review and pooled analysis. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:512. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angervall L., Kindblom L.G., Merck C. Myxofibrosarcoma: a study of 30 cases. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1977;85A:127–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansoor A., White C.R., Jr. Myxofibrosarcoma presenting in the skin: clinico-pathological features and differential diagnosis with cutaneous myxoid neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:281–286. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200308000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiga Y., Miura S., Nishikawa H., Sugihara H., Nakashima Y., Takamatsu Y. Very rare case of large obstructive myxofibrosarcoma of the right ventricle assessed with multi-diagnostic imaging techniques. Intern Med. 2014;53:739–742. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park H., Jo S., Cho Y.K., Kim J., Cho S., Kim J.H. Differential diagnosis of a left atrial mass after surgical excision of Myxoma: a remnant or a thrombus? Korean Circ J. 2016;46:875–878. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bortolotti U., Maraglino G., Rubino M., Santini F., Mazzucco A., Milano A. Surgical excision of intra cardiac myxomas: a 20-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;49:449–453. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(90)90253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pathak R., Nepal S., Giri S., Ghimire S., Aryal M.R. Primary cardiac sarcoma presenting as acute left-sided heart failure. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4:23057. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v4.23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]