Abstract

Background

There has been an exponential increase in knee arthroplasty over the past 20 years. This has led to a quest for improvement in outcomes and patient satisfaction. While the last decade of last century proved to be the decade for Computer-Assisted Surgery (CAS) or Computer Navigation wherein the technology demonstrated a clear benefit in terms of improving mechanical axis alignment and component positioning, this decade is likely to belong to Robotics. Robotics adds an independent dimension to the benefits that CAS offers. The article deals with the generation of robots, technical steps in robotics, advantages and downsides of robotics and way forward in the field of knee arthroplasty.

Materials and Methods

The review article was designed and edited by six different authors reviewing 32 relevant pubmed-based articles related to robotics in arthroplasty and orthopaedics. The concept, design and the definition of the intellectual content were based on the internationally published literature and insightful articles. The review is also based on the clinical experimental studies published in the literature.

Discussion

The robotic arm is actively involved with surgeon to achieve the precision and outcomes that the surgeon aims for. With the concept of haptic boundaries and augmented reality being incorporated in most systems, Robotic Assisted Arthroplasty (RAA) is likely to offer several advantages. The potential advantages of these systems may include accuracy in gap balancing, component positioning, minimal bone resection, reduced soft tissue handling and trauma, patient anatomy specific resection, and real time feedback. They, however, come with their own downsides in terms of capital cost, learning curve, time consumption and unclear advantages in term of long-term clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

To conclude, this review article offers a balanced view on how the technology is impacting current arthroplasty practice and what can be expected in coming years. The commitment of almost all major implant manufacturers in investing in robotics likely means that the evolution of Robotic technology and this decade will be exciting with rapid strides revealing paradigm shift and evolution of technology with significant reductions of cost enabling it to be available universally. For technology to populate in operating room, I think it will be result of exposure of young surgeons to these computers and robotics, as they grow in with confidence with technology from residency days to offer better precision in future.

Keywords: Robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty (RAKA), Robotic surgery, Computer assisted surgery (CAS), Component positioning, Alignment, UKR, Robotic arthroplasty, Knee arthroplasty

Robotic-Assisted Arthroplasty (RAA): New Frontiers, New Dimension

Over 15% of all unicompartmental knee arthroplasties in the USA are performed today using a robotic platform. This figure is expected to rise to up to 35% in the next 5 years and a similar expansion is expected with total knee replacement according to numerous sources [1, 2]. This growth will likely be fueled by increasing surgeon awareness and comfort, increased availability of training, data demonstrating improved outcomes, additional platforms entering the market, patient demand, and reduction in the cost of technology. The surrogate markers of this exponential growth are already visible in the form of an increase in the number of patents filed and peer-reviewed publications [3, 4].

To achieve the so-called “the forgotten knee”, the surgery needs to be perosnalized for every patient. However, it may be an unrealisitic expectation to achieve it in 100% of the patients; we should aim for it in at least 90% of the patients, and this demands following the basic principles of the surgery with precision [5]. This was dwelled on by Prof Lawrence Dorr in his recent insightful article on robotics where he sought to weigh the outcome scores and long-term survivorship difference with robotics [5].

Robotic technology gives a programmable dimension to the automated machines designed to do labor-intensive and repetitive work. Enabling a machine to sense its environment and empowering that same machine to function using decision making and learning algorithms demonstrate the interplay of AI and robotics, and is likely to be a revolutionary technology in the years to come. There has been no industry in the history of humankind that has been untouched by computers and automation. The common themes that automation brought to industry was increased efficiency, decrease in recurring cost, and standardization of outcomes. Arthroplasty surgery shares many of these same goals, including–reduction of surgical time, reduction of inventory and instrumentation, as well as generating reproducible outcomes in terms of accuracy of alignment and improved soft tissue balancing. If achieved, these outcomes are likely to impact patient satisfaction and durability of the procedure in a positive manner [6–9].

History of Robotic Technology in Arthroplasty

IBM’s Thomas Watson research laboratories in New York and University of California—Davis are credited in jointly developing the first active robotic system used in Joint Arthroplasty—the ROBODOC. This original robotic arm was the brain child of the late veterinarian Howard “Hap” A Paul and engineer turned orthopedic surgeon William Bargar. Matsen and his team were one of the first to publish its application in knee arthroplasty. The system described was based on a robotic platform that enabled saw and drill guide positioning with respect to patient’s anatomy and boney geometry. Around the same time, Keinzle’s team [10] developed a similar passive system that used a preoperative CT scan and pin-based registration technique. The semiactive era started with Van Hamn [11], robotic platform ensured that the cutting tools had constrained motion in a boundary demarcated by the surgeon. Later it was Golzman, La Palombara and Fadda [12, 13] who popularized the surface matching technique to register bone without the fiducial maker. Once registered, the active or semiactive robot will execute the bone preparation with milling techniques. In the following decade, several robots were developed and prototypes tested, but today only a handful is available for actual clinical use. A series of acquisitions of robotic surgery start-ups has set the stage for the availability of numerous platforms for orthopedic surgery in the coming decade. Prominent among them are the ROBODOC System (THINK Surgical, Invc., Fremont CA), the CASPAR (computer assisted planning and robotics) system (URS Ortho, Rstatt, Germany), the Robotic Arm Interactive Orthopedic System (RIO; Stryker Orthopedics Mahwah, NJ), the Navio PFS (Blue Belt Technologies, Plymouth, MN), APEX Robotic Technology (OMNILife science inv., East Taunton, MA) and the Stanmore Sculptor Robotic Guidance Arm system (Stanmore Implants, Elstree, UK), earlier known as the Acrobot system.

Various Technology Platform Differentiators in Robotics

-

A.

Autonomy: There are three main categories of robots based on the autonomy to the machine and surgeon—active, semiactive and passive. The passive system works under the constant and direct supervision of the orthopedic surgeon. At the other end of the spectrum is the active system which takes charge and performs the task independently without any surgeon input. The most prevalent system currently is the semiactive system which requires the surgeon’s active involvement and synergizes it with its own activity by providing audible, tactile and visual feedbacks. This approach also provides haptic restraints for the margins of surgical resection with either a speed or depth control mode for the working instruments like burr and saw.

-

B.

Active robots: CASPAR and ROBODOC.

Semiactive robots: MAKO’s RIO, Blue Belt’s NAVIO, Stanmore Sculptor RGA system, ZIMMER Rosa.

Passive robots: APEX ROBOTIC technology (OmniLife Science).

-

C.

Image vs imageless: An integral part of any robotic surgery is the creation of a plan which is ‘pre-approved’ by the surgeon before the actual execution. This is in contrast to other specialties such as urology, gynecology and abdominal surgery where systems such as Da Vinci are primarily focused on execution of the surgery. As will be discussed later in this manuscript, the anatomy of the patient needs to be registered so that the robotic arm knows how to align and position itself in space for appropriate execution—burring or resection. In image-based platform, a part of this happens before the actual surgery through the inputs from patient’s CT or MRI that has been done preoperatively. Intraoperatively, the robotic arm is used to validate a few dedicated landmarks and then the preferred data are used to generate optimal patient’s anatomical model using software. The advantage of the system is that it reduces surgical time and surgeons have a chance to look at the data and surgical plan before the actual start of the surgery. The disadvantages of such an approach are additional cost and radiation exposure. There has been a move toward using plain X-rays using a defined protocol for 3-D model generation and planning in platforms such as the ROSA. On the other hand, imageless systems rely on creation of patient’s anatomical model by registering specific landmarks and surfaces after the incision has been made. Open vs closed systems: This differentiation describes individual developer and companies’ monetization plan of their patented technology. The closed systems allow only one implant manufacturer’s product to be used with the system and are usually sold as a bundled product. Open platforms are usually third party, independent developments and allow various implant options giving surgeons the freedom to choose preferred implants.

-

D.

Clinically, it is argued that open systems often lack the specificities of various implant designs, and the developer being oblivious of possible biomechanical rationale of all the possible implant designs may not be able to incorporate finer adjustments that each implant design warrants. At the moment, however, this is debatable and the only thing that determines the decision to choose one over the other is cost and surgeon preferences.

Currently Available Robotic Platforms and their Parent/Acquiring Company

Stryker: Mako

Medtronics: Mazor X Stealth

Zimmer Biomet: ROSA

Smith and Nephew: Navio

Globus Medical: ExcelsiusGPS

Nuvasive: Pulse

On the Horizon:

-

7.

Johnson and Johnson (DepuySynthes): Orthotaxy

Technical Note on Conventional and Robotic Technology

Achieving neutral alignment of the lower limb with appropriate soft tissue balance is the primary aim of the TKA. The accurate tibial and femoral bone resections and appropriate soft tissue release is crucial to achieve this aim. In conventional surgery, one uses a combination of specially designed saw guides and alignment aids to ensure the bone resections are adequate for the implant and reproducing the correct alignment for the limb; spacers are used to check and fine-tune soft tissue balance.

The robotics as well as the navigation systems describes more precise instrumentation specifically for the bone cuts in coronal plane [5]. The rotational mating of the implants and the soft tissue balancing of the knee remain dependent on the surgeon’s decision irrespective of the instrumentation [5]. Computer navigation adds a measurable dimension to the steps of conventional surgery by providing optical reflector arrays attached to the instruments. Surgical steps can then be navigated with the help of an image on the navigation screen which allows the surgeon to see and correct every placement of a cut guide and every step of the alignment achieved.

Basics Steps in Computer-Aided Surgery and Robotics

The key steps common to all CAS and robotic platform are (Fig. 1):

registration/mapping,

plan verification,

guided cuts,

validation,

adjustment,

component positioning,

revalidation,

balance through simulated ROM.

Fig. 1.

Key steps in robotic arthroplasty

Registration/Mapping

Registration or surface mapping is also known as bone morphing and this process involves acquiring data of the key anatomical landmarks and surfaces. It is the process of recreating the patient’s individual 3D-dimensional bony anatomy in the system. Systems like NAVIO utilize image-free registration process that relies on standard principles to construct a virtual representation of the patient’s anatomy and kinematics. On the other hand, systems like MAKO rely on the preoperative CT scan evaluation and probe registration of the checkpoints to link it to a 3D virtual bone model. Other systems such as ROSA use a preoperative X-ray to create the 3D model. The first step in the registration is to identify the key landmarks with a probe. The key landmarks on the tibia are the prominent most points on the medial and lateral malleoli to find out the center of the ankle. The next landmark is the hip center of rotation identified by the rotation of the femur around its axis, with optical arrays in place. Then the patient’s coronal plane (varus/valgus) alignment is registered with leg in extension and ankle dorsiflexed with pressure. The next step is to register the preoperative knee range of motion and laxity of the collateral ligaments. After registration of the kinematics, the registration of anatomy is started. The key landmarks for registration of the femoral condylar surfaces are the knee center, most posterior medial point, most posterior lateral point, and the anterior notch point. The rotational alignment of the femur is registered with transepicondylar axis, femoral AP axis, or posterior condylar axis. The femoral condylar surface registration is done by “painting” over the femoral articular surface with the probe.

The successful registration of the femur is followed by the tibial anatomy registration. There are three landmarks to collect on tibia: the knee center, medial tibial plateau, and the lateral plateau points. Then, the rotational configuration of the tibia is defined by the tibial rotational axis: tibia AP axis, mediolateral axis, transverse femoral mechanical axis, and medial third of the tibial tubercle. The tibial articular surface is mapped by painting the condylar surfaces with the optical array probe until the virtual model is formed. To enhance the accuracy, the painting is performed over the edges after removal of the osteophytes which also helps in sizing of the surface.

Key Landmarks for Registration

On the tibial side (Fig. 2):

Proximal tibia: proximal mechanical axis point.

Ankle: distal mechanical axis point.

Medial compartment: medial compartment and its geomathematical center.

Lateral compartment: lateral compartment and its geomathematical center.

Fig. 2.

Registration of tibial side

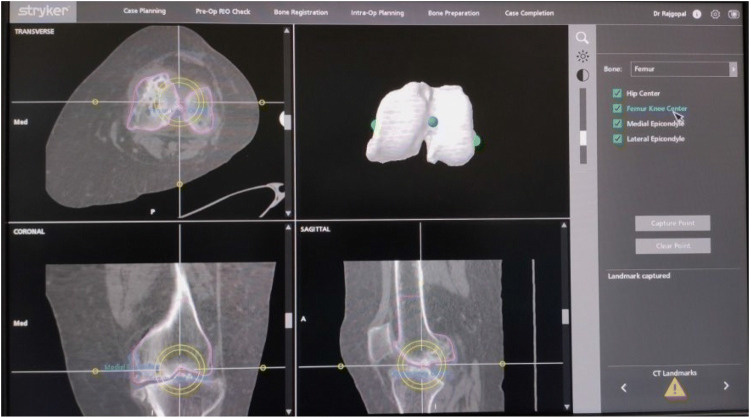

On the femoral side (Fig. 3):

Femoral head center: proximal mechanical axis point.

Medullary entry point: distal mechanical axis point.

Medial epicondyle: medial transepicondylar axis point.

Lateral epicondyle: lateral transepicondylar axis point.

Morphing the femoral condyles: distal most and posterior most points.

Proximal and distal anatomic axis points.

Fig. 3.

Registration of femoral side

Creation of a virtual model (Fig. 4): In the systems like MAKO, a computed tomography of the patient is uploaded in the system prior to the surgery, acquired using specified imaging protocols. The preoperative implant sizing, releases and difficulties can be anticipated in these types of systems. The intraoperative registration is based on the system-guided landmarks. The collaborative virtual model is created by the system based on the patient’s imaging as well as the intraoperative registration. The imaging adds to further accuracy in the creation of the virtual model of the patient`s anatomy and thus aligning the system for the cuts.

Fig. 4.

Creation of virtual femoral model

Once bony registration is complete, a 3-D model of the knee is recreated that closely matches the patient’s native anatomy.

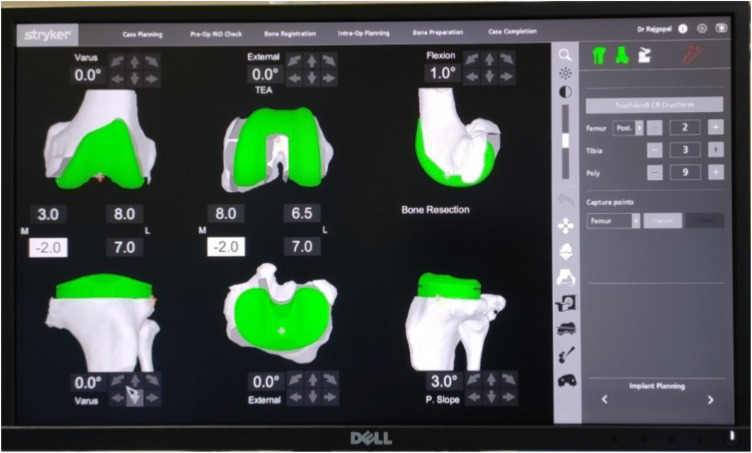

Plan verification by the surgeon (Fig. 5): After registration the system provides the surgeon with a virtual view of the patient’s bony anatomy, as well as an overview of the ligament tension and the joint balance. The next step is to plan the initial sizes of the implants and their placement which is automatically determined by the system based on the landmarks acquired during registration. The newer upgraded version of the software allows the surgeon to adjust the sizes and position. Moreover, the level of resection and joint line position can be adjusted according to the mechanical alignment of the limb. The system provides the guide to expected ligament balancing throughout the range of flexion and extension, the ultimate goal being to orient the implant such that the laxity is roughly balanced between 1 and 2 mm through the range of motion while avoiding overcorrection. To achieve adequate balancing, adjustments are made in the implant flexion, rotation, sizes, translation, varus/valgus, and the depth of resection. After satisfactory positioning and balancing is set in the interface, the surgeon has a clear idea of the bony resections to be performed and the expected implant sizes as well as the projected alignment, and the next step is the preparation of the bone surfaces using the robotic tools.

Fig. 5.

Plan verification by the surgeon

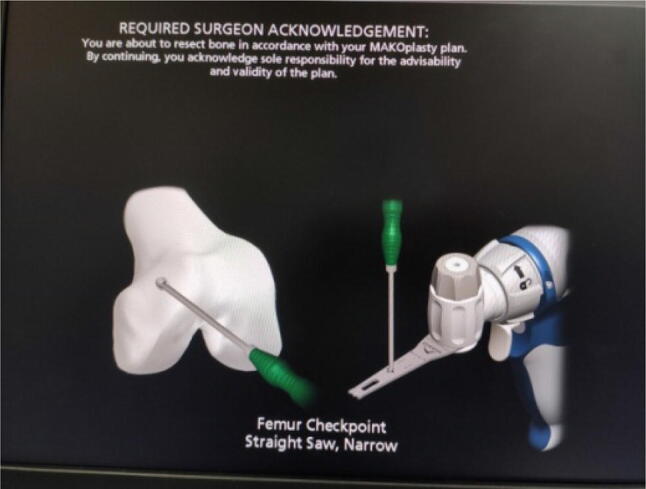

Guided cut (Fig. 6): The robotic handpiece is either semiautonomous or autonomous. In semiautonomous systems like NAVIO, the surgeon has free control over the handpiece. The term haptic refers to the technology that uses proprioceptive touch to control and interact with autonomous device and computers. The haptic controls in systems such as Navio and MAKO, disable the cutting action outside the planned zones. Haptic controls can be of two types: (a) “exposure control”—in which the robot retracts the cutting device in the protective guard when the unplanned zone is assessed; (b) “speed control”—the speed of the device is slowed and eventually stopped on entering the unplanned zone. The robotic arm can either (a) hold a cut guide in the desired position to achieve the planned resection or (b) hold a motorized burr, which is used to mill the bone surfaces to the desired depth and shapes. While each innovator has its own guided cutting arm tool, it is generally believed that we are moving to a burr technique given its advantage in terms of more precision and surgeon-enabled control mechanisms (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Guided cuts, component positioning and gap balancing in extension

Fig. 7.

Guided cuts, component position and gap balancing in flexion

Validation of the cuts and adjustments: The postoperative gap balance can be measured throughout the range of motion in both compartments at any stage for the validation of the cuts. At any stage if the surgeon wants to make subtle adjustments in planned resections, it can be done with ease by simply returning to plan verification and bone removal stages. The parameters like the slope, level of resections in both compartments, and balancing can be revisited and altered. These adjustments can be done with precision in robotic systems with minimal bone removal speed-controlled burr. After the satisfactory alignment, the manual implantation of the implants is done using the surgeon`s standard protocols.

Checking the knee balance through simulated range of movement: The knee balancing can be rechecked through a simulated range of motion with trial implants in situ. The balancing can be rechecked and revalidated even with the final positioning of the implants. The alignment of the limb axes in relation to the knee can also be checked; this feature is usually helpful in less deformed knee in which the surgeon aims for kinematic alignments of the knee with respect to the limb axes.

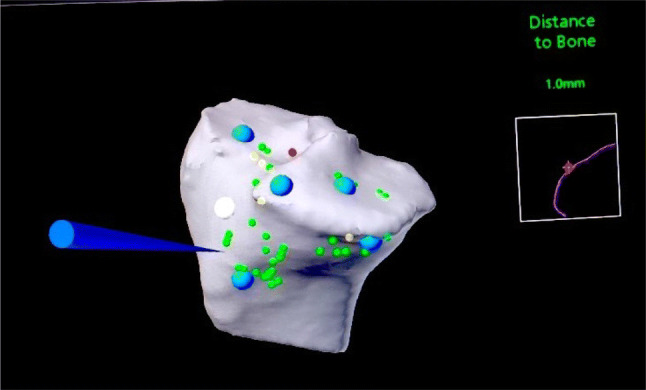

Difference between ROBOTICS and CAS: Three key parameters that differentiate the robotics from CAS is the ability of robotics to create haptic boundary, provide real-time feedbacks, and the ability to leverage augmented reality for more real-time experience (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Registration of the bone and cutting tool

Haptic boundary creation: Once the system is ready with the final plan built according to the surgeon, the system aligns the instruments (burr/saw) in the desired plane. The bone to be cut (Femur/Tibia) is first registered with the optical markers, which is followed by the registration of the cutting tool. The haptic boundaries are created when the cutting tool is brought in the vicinity of the bone selected. The haptic boundary created is based on the accuracy of registration and provides the protection to the vital soft tissues surrounding the knee. The encroachment of these haptic boundaries comes with the various feedbacks from the system, which can be audible (beep), visual (color change on the screen) or tactile (vibratory) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Haptic boundary creation

Augmented reality: The newer platforms use augmented reality as a key differentiating factor to improvise the surgeon experience intraoperatively. Integrating virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) enable live and virtual imaging featured on the robot-assisted user interface, facilitating the surgeon’s ability to position and manipulate the robotic instruments. Live surgical imaging is enhanced by superimposition and image injection of location-specific objects. The digital information is overlaid on the physical world that is in sync with both spatial and temporal registrations obtained intraoperatively and is interactive in the real time during the surgical interventions.

Key Technology Assessment Parameters for TKR and UKA’s

Tibial cut—coronal and sagittal plane alignment.

Tibial cut—depth.

Tibial implant positioning.

Femoral–coronal alignment.

Femoral rotation.

Femoral resection depth.

Femoral component positioning.

Balancing through the range of movements.

Decisive Data on Improved Outcomes

Three critical parameters used as proxy of success in UKR and TKR have been accuracy of implant position in coronal (varus–valgus) and sagittal plane (slope); depth of bone resection (reflected in thickness of poly) and soft tissue balance [14].

Alignment in UKR: Lonner et al. [15] did an alignment study in which he found that average root mean squared error was significantly improved with robotics (RMSE1.9 Robotic; 3.1 Conventional) and that the robotic cohort had 2.6 times decreased variance. The study also showed that in the group where surgeons used conventional jigs, the tibial component was placed in greater degree of varus (mean 2.7°) as compared to the robotic group (mean 0.2°). The same results were replicated by Bell and Dunbar in their studies [16–19]. Bell is credited with performing the first prospective randomized controlled trial between the conventional instrumentation vs robotic unicompartmental knees over 120 patients. The image-based robotics was used in 62 patients and 58 were performed with conventional jigs and positioning of the implants was assessed postoperatively. Employing postoperative CT scans to check coronal sagittal and axial positioning, he demonstrated the superiority of the robotic-assisted UKA over those done using the conventional jigs for all the parameters (p < 0.02).

However, not all studies consistently demonstrated the benefits of robotics-assisted UKA’s. In a CT-based study of 64 patients (32 robotics vs 32 conventional), Hansen et al. [20] categorically pointed out that there was no difference in tibial component positioning, some improvement in femoral component positioning, and a noteworthy aspect was the addition of 20 min to surgical time. Surprisingly and without any specific reason attributable, the study found that the patients in the robotic group achieved physical therapy milestone 10.3 h sooner and had 8 h shorter length of stay compared to those cohorts that underwent UKA using conventional techniques.

With regard to the depth of the tibial cut, a large study by Ponzio et al. [21] in which he compared 8421 robot-assisted UKA to 27,989 conventional UKA showed that bone-conserving tibial resections were much higher (93.6%) in the robotic group compared to the conventional group (84.5%). It is an established fact that it is advantageous to minimize the bone resection, as the proximal tibial bone is weaker and undersized with the more distal tibial resection [14]. Also, in event of a future revision to a TKR, reconstructions may become challenging and one requiring using of tibial augments and stems.

Soft tissue balancing in UKR: Another important issue for arthroplasty surgeons is balancing of the knee—not only the look, but also the feel of the knee. Robotic offers an additional advantage in terms of the ability to accurately quantify the extent of uniformity of the soft tissue balance throughout the arc of the motion. In a study of 52 patients who underwent a knee replacement using a robotic platform, Plate et al. [22] assessed the balancing and soft tissue tension at 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, and 110° of the knee movement. They noted that use of the robotic platform enabled an accuracy of up to 0.53 mm of the preoperative plan and 83% of cases were within 1 mm of the preoperative plan. A well-balanced knee has a significant impact on the knee kinematics, functionality, patient satisfaction, and durability. The newer versions of the software from the majority of the companies are increasingly incorporating this feature to ensure that the maximum benefit of technology is reflected in the outcomes.

PROM and longevity of the implant: From a patient’s and regulator’s perspective, two key parameters that influence the decision making are whether all the purported benefits of improved alignments, positioning, and balancing result in better clinical outcomes and improve the life of the implants [23]. The data on both of these are scant, although as experience and number of years pass by we are seeing some clear trends [24–26]. In a prospective study, median pain scores were observed from day 1 postoperatively to week 8. It was found that the scores were 55.4% lower in the robotic group than in the conventional jig group. The robotic group also had a better Knee Society Score (KSS) at 8 weeks. Another important measure—Forgotten Knee score achieved in > 80% of patient was statistically higher in the robotic group than the conventional group (15% vs 8% P ¼ 0.265). On a subgroup multivariate analysis, it was noted that those with higher level of preoperative activity had statistically better outcomes. This also corresponded to reduced incidence of stiffness and continued on till 2 years postoperatively.

In the same study when analyzing the durability and longevity of well-functioning implant, it was found that there were two revisions in the conventional group and none in the robotic group [23]. While robust midterm and long-term survivorship data on the impact of technology is lacking, short-term data when extrapolated offer an insight into the purported benefits in a manner similar to computer-assisted surgeries (CAS) [25]. Pearle et al. did a multi-center review of 1135 UKA done with robotic assistance, and on a mean follow-up of 2.5 years (range − 22 to 52 months) reported a 98.8% survivorship with 11 revisions. These data on survivorship are marginally better than the ones described in the national registry for conventional UKA. The same study also reported a better patient-reported outcome with 92% patient reporting satisfaction and operation outcomes on the expected lines. While these small studies with smaller follow-ups demonstrate a promising outcome, more robust midterm and long-term outcome and survivorship study are required to evaluate the impact of robotic technology.

Impact of robotic technology in alignment, functional outcomes and survivorship in TKA: Despite the controversy on the ideal alignment for the knee and the role of constitutional varus [27, 28], it is well established that both CAS and robotics aid in achieving a particular surgeon’s targeted alignment that ‘he has chosen’ as his preferred technique. While the effect of robotics on UKA has been more extensively studied, the data on use in TKA are limited primarily because many of the commonly used platforms have upgraded them only recently to have software and platforms enabling surgeons to perform TKAs. The earliest observational studies [29–32] have by and large been favorable and Belleman showed that the robotic platform helped achieve an alignment within 1° error in all the measured planes. In an interesting study by Song et al. [30], the authors did a randomized clinical trial with 30 patients of bilateral total knees randomized, wherein one side was done using conventional methods and the other side using a robotic system. A more precise outcome with restoration of neutral axis to a mean of 0.2 in contrast to 1.2 for conventional was noted. They also noted a reduced number of outliers and lesser flexion extension gap mismatch.

Downside of current RAKA

While any technology promises to make an average surgeon a good surgeon and a good surgeon a better surgeon, it comes with a cost often incremental in nature. Some of the obvious downsides of the RAKA are:

Capital expenditure: The national health-care expenditure accounts (NHEA) that are the official estimate of the total health-care spending in the USA predict that by the end of this decade, the health expenditure will be 19.2% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [33]. It is imperative that we be critical of the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of the new technology. Robotics comes with a significant financial investment, which is usually prohibitive to small surgical volume centers. The newer versions of robots are less expensive than earlier generations. Most surgeons believe and if the phrase can be borrowed from other industries—eventually the robots will become cost neutral, as the initial CapEx will be recovered from the improved patient outcome, reduced surgical time, improved OR efficiency and decreased inventory.

Recurring cost of disposables and imaging: The higher costs are further added with the maintenance costs that include the servicing and software as well as the disposables and the consumables that are used with each case. The image-based systems that require preoperative CT scan have added costs making its implementation cumbersome. [23, 24]

Soft tissue and bone complication: The placement of pins to mount the optical arrays and markers for registration of bony landmarks act as stress risers, which may lead to pin-related peri-prosthetic fractures, if placed in the diaphyseal bone. If the bone tracts made for arrays are not properly sealed and they connect the medullary cavity, cement leakage may occur and lead to faulty cementing. Hence, they must be strategically placed in the metaphyseal bone. Inadvertent pin placement theoretically may be a potential independent risk factor for neurovascular complications and post surgery pin tract infection.

Radiation exposure: The robotic systems that need preoperative CT scans for surgical mapping of the patient`s anatomy and planning expose the patient to significant radiation exposure. A study by Ponzio et al. states that the average effective dose of radiation for preoperative CT scan conducted for robot-assisted knee TKA was 4.8 ± 3.0 mSv (millisieverts), approximately equal to 48 chest radiographs. 25% of the patients in that study of 211 patients had one or more additional CT scans, with a maximum effective dose of 103 mSv. According to US FDA, the CT radiation dose of 10 mSv can cause a fatal cancer in 1 in 2000 patients compared to its natural incidence. Hence, the radiation risks and its exposure related complications should not be neglected, and preventive measures need to be taken to avoid the preventable. However, it is necessary to learn that the radiation-related events are not inherent in all robotic technologies. The image-free systems do not carry the need of CT scans and hence not associated with their potential hazards [26].

Operative time and learning curve: The use of robots in knee arthroplasty has been shown to increase the operative time. With the advent of novel advanced technologies, there are concerns of increased surgical time, leading to increased tourniquet time and related complications, infection rates, blood loss, and OT turnover time.

Communication between the optical arrays and system array is necessary all the time, for which the optical arrays need to be held in a certain position. This can be cumbersome in initially steep learning curves. The position of the arrays in the bone needs to be maintained throughout the procedure, which pertains to the operative steps, and with osteoporotic bone may be cumbersome. In imageless systems, the tracing of selected areas to create a 3D image of the patient`s anatomy is necessary which further increases the surgical time [34]. The blood loss and surgical incisional pain may be reduced with modern day local injection techniques for hemostasis and pain control.

Comparison Between Various Technologies

| Technology | Accuracy | Surgical time | Inventory | Capital expenditure | Recurring costs (disposables) | Learning curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Jigs | Standard | Standard | Standard | None | None | Standard |

| CAS | Improved | Increase | Increase | Significant | High | High |

| PSI | Standard | Standard | Decrease | None | High | Standard |

| Pin less (handheld) navigation | Standard | Marginal increase | Marginal increase | None | High | Standard |

| Robotics | Possibly improved | Increase | Increase | Significant | High | High |

Real-life comparison to driving: There is an interesting parallel between the use of technology to driving experience. While CAS and pinless navigation is akin to using a GPS in the car, PSI is like hiring a taxi service (Uber or Lyft) and robotic is like having a chauffeur. The era of true driverless car and surgeonless robotic surgery is yet to arrive. Irrespective of what the future holds, the key point in using all these is to understand two things—one, you must know where you have to go; and secondly, you must remember that you are the one deciding where to go!

Comparing Various Robotic Platforms

| ROBOTIC system | Company | Surgery | Pre-op plan | Control | Implant platform | Bone resection | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAKO | Stryker | UKA, TKA, THA, PFA | CT scan | Semiautonomous, haptic | Closed | Burr, saw | Prevents excess bone resection outside desired plan |

| Navio PFS | Smith and Nephew (FDA approved in 2012) | UKA, TKA, PFA | None |

Semiautonomous Handheld end cutting burr that extends and retracts |

Open | Burr, saw |

Freehand crafting for UKA, PFA and TKA Only planned bone is removed Optical-based navigation with imageless system |

| ROSA knee | Zimmer Biomet | TKA | None | Semiautonomous, haptic | Closed | Saw | It has a haptically positioned resection guide, but no cutting saw |

|

ROBODOC TSolution One |

Think Surgical Inc | TKA, THA (femur) |

CT scan CAS |

Autonomous | Open | Mill | |

| iBlock | OMNIlife Science | TKA | None | Autonomous | Closed | Saw |

Imageless motorized bone mounted cutting guide Follows surgeon’s plan Adjustable cutting block No haptic feedback |

Other Systems

Other systems being explored are miniature bone-mounted robots [26], for example, PiGalileo (Smith and Nephew)—a passive system having a hybrid navigated robotic device for the distal femoral shaft. The MBARS (mini-bone attached robotic system) is developed for patellofemoral joint arthroplasty [27]. The Praxiteles was a predecessor of modern day iBlock [28] The Hybrid bone attached robot for joint arthroplasty was developed by Song et al. that uses the hinged prismatic joints which provide structurally rigid robots for minimal access surgery in TKA [29].

Is it Necessary?

This is the most often debated point in arthroplasty conferences these days. A balanced view on the subject is the need of the hour. All the stakeholders, both advocate and sceptics, have to come together before a decision on acquiring an equipment with high Capex is taken. These critical stakeholders include not only surgeons/physicians, but also hospital administrators, patients, regulators and payers. The data from short-term studies have shown that the technology has a positive impact on alignment and in reducing the number of outliers. To truly make a mark, this has to be corroborated with evidence of improvement in the implant durability and patient satisfaction in the long term. If it does, we will see that robots becoming ubiquitous and a rapid advancement in the technology. If it, however, shows equivalence, it will stay for only one reason and that is its ability to play a role in economy of scale and as a marketing role. While a true picture is yet to emerge, one thing is clear at the moment—surgeon indulgence is likely to grow not out of necessity, but out of human curiosity to explore and improvise.

When Is the Right Time to Buy a Robotic Platform?

The practice of arthroplasty today faces a unique dilemma. High volume surgeons and centers that have proven track record and ability to deliver good outcomes in terms of the accuracy of alignment feel that investing in the technology may not necessarily improve their results and thus does not justify the expense. The answer to the question is of course a cliché—the time to do the right thing is now! This, comes with a rider—While early buyers may benefit it by leveraging it to market their infrastructure, the technology is still not mature and rapid progress and newer generations of devices are expected to roll out in quick succession in the coming years. Thus, while it is important to be abreast about the development and indulge in this technology, the optimal time to really buy is perhaps a few years from now. If one is too late—one will miss the bus; if too early, one will regret buying something that will soon become outdated. Stewart Brand, the tech guru and futurist, while discussing technology, very aptly summarizes the debate: “Once a new technology rolls over you, if you’re not part of the steamroller, you’re part of the road.” The decision will, in effect, be one which requires the active inputs of the surgeon, the hospital system, the insurer/payer and to some extent, the demand for the technology from the end consumer, the patient himself.

The road ahead—onwards and upwards

The thirst for the innovation is the thrust for progress of mankind. No industry has been untouched by this and it remains a fact that once the process of automation and robotics starts, it is irreversible. Although today there is a limited data demonstrating the superiority of robotic platforms, there is clear evidence that these platforms enable surgeons to position a component with greater precision in a position that he desires. While each surgeon may have his own ‘ideal positioning and concept of alignment’ and they may keep changing with time, the ability to achieve the desired position is enhanced. In both CAS and robotics, a good data acquisition either through image or imageless is perhaps the most crucial step. Robotics differs from CAS by introducing haptic feedback and boundary limitations and providing real-time feedback. The availability of augmented reality in newer platform is a significant with real-time fine-tuning of alignment and balance. The translation of these into newer insights on patient requirements, outcomes and even new generation implant design, is yet to be seen and is something we must keenly look forward to in the future. Almost all major implant companies have placed their bids on the evolution of the robotic technology and the next decade is going to be exciting with rapid strides in the improvement of technology and hopefully reduction in costs of the technology will make it all pervasive and a game changer. The future of the technology is truly onwards and upwards.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vaibhav Bagaria, Email: drbagaria@gmail.com.

Omkar S. Sadigale, Email: dromkarss@gmail.com

Prashant P. Pawar, Email: dr.ppp195@gmail.com

Ravi K. Bashyal, Email: ravi.bashyal@gmail.com

Ajinkya Achalare, Email: ajinkya1401@gmail.com.

Murali Poduval, Email: murali.poduval@tcs.com.

References

- 1.Orthopedic Network News. (2013). Hip and knee implant review. Available at: http://www.OrthopedicNetworkNews.com.

- 2.MDDI Online. MDDI Online. (2020). Available from: https://www.mddionline.com/. Cited Feb 21, 2020

- 3.Boylan M, Suchman K, Vigdorchik J, Slover J, Bosco J. Technology-assisted hip and knee arthroplasties: an analysis of utilization trends. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33(4):1019–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalton DM, Burke TP, Kelly EG, Curtin PD. Quantitative analysis of technological innovation in knee arthroplasty: using patent and publication metric to identify developments and trends. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1366e72. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorr LD. CORR Insights®: Does robotic-assisted TKA result in better outcome scores or long-term survivorship than conventional TKA a randomized, controlled trial. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2020;478(2):276–278. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalton DM, Burke TP, Kelly EG, Curtin PD. Quantitative analysis of technological innovation in knee arthroplasty: using patent and publication metrics to identify developments and trends. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1366–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacofsky DJ, Allen M. Robotics in arthroplasty: a comprehensive review. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2016;31(10):2353–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonner, J. H. (2009) Robotic arm–assisted unicompartmental arthroplasty. In Seminars in Arthroplasty 2009 Mar 1 (Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 15–22). WB Saunders.

- 9.Lonner JH, Moretti VM. The evolution of image-free robotic assistance in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. American Journal of Orthopedics. 2016;45(4):249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kienzle III TC, Stulberg SD, Peshkin M, Quaid A, Ambarish JL, Lea J, Goswami A, Wu CH. A computer-assisted total knee replacement surgical system using a calibrated robot.

- 11.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. JBJS. 2014;96(8):624–630. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. JBJS. 2007;89(4):780–785. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200704000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Palombara PF, Fadda M, Martelli S, Marcacci M. Minimally invasive 3D data registration in computer and robot assisted total knee arthroplasty. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 1997;35(6):600–610. doi: 10.1007/BF02510967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarzkopf R, Mikhael B, Li L, Josephs L, Scott RD. Effect of initial tibial resection thickness on outcomes of revision UKA. Orthopedics. 2013;36(4):e409–e414. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130327-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonner JH, John TK, Conditt MA. Robotic arm-assisted UKA improves tibial component alignment: a pilot study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2010;468(1):141. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0977-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell SW, Anthony I, Jones B, MacLean A, Rowe P, Blyth M. Improved accuracy of component positioning with robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Data from a prospective, randomized controlled study. JBJS. 2016;98(8):627–635. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blyth MJ, Anthony I, Rowe P, Banger MS, MacLean A, Jones B. Robotic arm-assisted versus conventional unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Exploratory secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Bone & Joint Research. 2017;6(11):631–639. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.611.BJR-2017-0060.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunbar NJ, Roche MW, Park BH, Branch SH, Conditt MA, Banks SA. Accuracy of dynamic tactile-guided unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonner JH, Smith JR, Picard F, Hamlin B, Rowe PJ. Riches PE (2015) High degree of accuracy of a novel image-free handheld robot for unicondylar knee arthroplasty in a cadaveric study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2015;473(1):206–212. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3764-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen DC, Kusuma SK, Palmer RM, Harris KB. Robotic guidance does not improve component position or short-term outcome in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1784–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponzio DY, Lonner JH. Robotic technology produces more conservative tibial resection than conventional techniques in UKA. American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead, NJ). 2016;45(7):E465–E468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plate, J. F., Mofidi, A., Mannava, S., Smith, B. P., Lang, J. E., Poehling, G. G., Conditt, M. A., Jinnah, R. H. (2013). Achieving accurate ligament balancing using robotic-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Advances in Orthopedics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Sharkey PF, Lichstein PM, Shen C, Tokarski AT, Parvizi J. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today—has anything changed after 10 years? The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1774–1778. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blyth M, Jones B, MacLean A, Rowe P. Two-year results of a randomized trial of robotic surgical assistance vs manual unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Annual Meeting of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. November 2017; Dallas, TX.

- 25.Chowdhry M, Khakha RS, Norris M, Kheiran A, Chauhan SK. Improved survival of computer-assisted unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: 252 cases with a minimum follow-up of 5 years. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017;32(4):1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearle AD, Van Der List JP, Lee L, Coon TM, Borus TA, Roche MW. Survivorship and patient satisfaction of robotic-assisted medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a minimum two-year follow-up. The Knee. 2017;24(2):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2002;404:7–13. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. JBJS. 2010;92(12):2143–2149. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H, Vanlauwe J. Robot-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2007;464:1116. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318126c0c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Decking J, Theis C, Achenbach T, Roth E, Nafe B, Eckardt A. Robotic total knee arthroplasty the accuracy of CT-based component placement. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 2004;75(5):573–579. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SE, Lee CT. Comparison of robotic-assisted and conventional manual implantation of a primary total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of arthroplasty. 2007;22(7):1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song EK, Seon JK, Park SJ, Jung WB, Park HW, Lee GW. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty with robotic and conventional techniques: a prospective, randomized study. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2011;19(7):1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cms.gov. (2020). National Health Expenditure Data | CMS. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData. Cited Feb 21, 2020.

- 34.Liu Z, Gao Y, Cai L. Imageless navigation versus traditional method in total hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery. 2015;1(21):122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]