Abstract

Fulminant myocarditis is a life-threatening fast progressive condition. We present a 7-year-old female patient admitted with a diagnosis of acute myocarditis with a rapidly progressive cardiac dysfunction despite conventional vasoactive and inotropic treatment. The patient presented with ventricular fibrillation and subsequent cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was performed during 105 minutes before extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) cannulation was performed. Effective hemodynamic function was obtained, and ECMO was weaned after 7 days, without neurological complications. There are not established extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) treatment criteria, and some international guidelines consider up to 100 minutes of “low flow” phase as a time limit to start the support. Some mortality risk factors for ECMO treatment mortality are female gender, renal failure, and arrhythmias. Pre-ECMO good prognostic factors are high levels of pH and blood lactate.

Keywords: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, myocarditis, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, risk factor, prognostic factors

Introduction

New technologies in medicine have given new opportunities of survival to patients suffering from severe hemodynamic imbalance, cardiac failure, or cardiorespiratory stroke, as well as patients with rapidly progressive or fulminant myocarditis. Acute myocarditis in pediatric patients is a medical condition. It is characterized for being refractory to medical treatment even in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, consequently having a high mortality. 1 2

Nowadays, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has demonstrated to be an effective support for pediatric patients suffering from fulminant myocarditis. 3 The American Heart Association (AHA) considers infants and children with acquired or congenital cardiopathy as high-risk population prone to cardiac arrest. Therefore, extracorporeal life support (ECLS) is accepted when cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) fails as a bridge therapy for other medical treatments. 4 5 Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) is defined by Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) as a type of reanimation where extracorporeal life support is used as initial part of the treatment for patients with cardiorespiratory stroke. 6

This case report presents a 7-year-old female patient with a fulminant myocarditis who was cannulated during prolonged cardiorespiratory stroke, with successful outcomes in the absence of neurological sequelae.

Materials and Methods

A 7-year-old female patient who had two previous admissions in pediatric ICU due to heart failure secondary to a nonspecified myocarditis was admitted. Seventy-two hours before the admission, refractory fever, asthenia, adynamia, and generalized paleness were present. The patient was admitted to her local hospital to study her condition where she presented five events of generalized seizures. She was taken to a private hospital (Hospital Muguerza Alta Especialidad ) in Monterrey, Nuevo León, for further treatment.

At her admission, the patient presented hypotension, paleness, hypokinetic pulse, delayed peripheral capillary filling, tachycardia, and grade IV/VI heart murmur. The patient was then transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit, where tracheal intubation was performed, and inotropic therapy initiated. Hemodynamic monitorization was performed using invasive blood pressure measurements, as well as cerebral and renal near-infrared spectroscopy. Echocardiography confirmed severe mitral insufficiency and severe biventricular dysfunction with evidence of 25% of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Results

Twelve hours after the admission to the ICU, an event of ventricular fibrillation and asystole occurred. Advanced CPR was performed for 1 hour and 45 minutes. During this prolonged resuscitation maneuvers, ventricular fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia, pulseless ventricular tachycardia, and pulseless electrical activity were observed in the electrocardiograph. Then, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) was performed through peripheral cannulation of the right internal carotid artery using 14 Fr arterial cannulae and 19 Fr right internal jugular vein cannula. Heparin (100 U/kg/hour) was previously administered. Maquet (Rastatt; Baden-Württemberg, Germany) PLS Membrane and Rotaflow Centrifugal Pump were utilized. Monitorization was done measuring venous oxygen saturation, hematocrit, and post membrane oxygen saturation using the Medtronic (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) Biotrend System. Support was initiated using 100 mL/kg/hour pump flow, 1615 revolutions per minute (RPM) 1,000 mL/min sweep, and 100% fraction of inspired oxygen. Heparin was started 3 hours after initiating support at a dose of 10 U/kg/h ( Table 1 ). Twenty-four hours after cannulation, a metallic tip cannulae is placed into left atrium due to severe left ventricle dysfunction (< 10% LVEF), pulselessness, stenotic aortic valve, and severe mitral regurgitation. A right atrium cannulae is placed to improve outflow. During VA-ECMO, inotropic support and continuous hemofiltration were performed to treat acute kidney injury. During this period, hemodynamic stability was achieved with normal BSG, stable cardiac function (43% LVEF), and arterial pulses.

Table 1. Main parameters during extracorporeal life support.

| ECMO days | Flow (mL/min) | RPM | ECMO FIO 2 (%) | ECMO sweep (L/min) | Heparin (U/kg/h) | ACT (s) | VENOUS SAT (%) | MAP (mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,130–2,000 (m = 1,591) | 2,399–3,416 (m = 2,914) | 55–100 (m = 76) | 80–1,800 (m = 1,130) | 10–20 (m = 12.5) | 175–339 (m = 221) | 64–91 (m = 79 | 30–90 (m = 64) |

| 2 | 1,400–2,100 (m = 1,675) | 2,380–3,071 (m = 2762) | 60–100 (m = 74.7) | 500–1,000 (m = 760) | 11–12.5 (m = 12) | 145–206 (m = 167) | 88–91 (m = 89) | 50–69 (m = 58) |

| 3 | 1,640–1,880 (m = 1,728) | 2,755–2,945 (m = 2,775) | 60 (m = 60) | 900 (m = 900) | 12.5–16.5 (m = 15.7) | 142–164 (m = 153) | 79–91 (m = 85) | 55–70 (m = 58) |

| 4 | 1,190–1,760 (m = 1,549) | 2,300–2,800 (m = 2,647) | 50–60 (m = 52) | 900 (m = 900) | 15–16 (m = 15.1) | 128–190 (m = 145) | 89–97 (m = 93) | 55–90 (m = 70) |

| 5 | 1,210–1,320 (m = 1,275) | 2,365–2,385 (m = 2,382) | 40–50 (m = 45) | 900 (m = 900) | 15–20 (m = 17.1) | 118–150 (m =137) | 83–98 (m = 88) | 60–78 (m = 67) |

| 6 | 1,000–1,340 (m = 1,095) | 2,225–2,285 (m = 2,294) | 40 (m = 40) | 900 (m = 900) | 19–20.5 (m = 19.5) | 121–191 (m = 143) | 82–92 (m = 89) | 54–84 (m = 73) |

| 7 | 990–1,280 (m = 1,148) | 2,285–2,470 (m = 2,315) | 40 (m = 40) | 900 (m = 900) | 20–21 (m = 20.6) | 140–146 (m = 143) | 84–89 (m = 85) | 66–79 (m = 71) |

Abbreviations: ACT, anticoagulation therapy; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FIO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; m, mean; MAP, mean arterial pressure; RPM, revolutions per minute; VENOUS SAT, venous saturation.

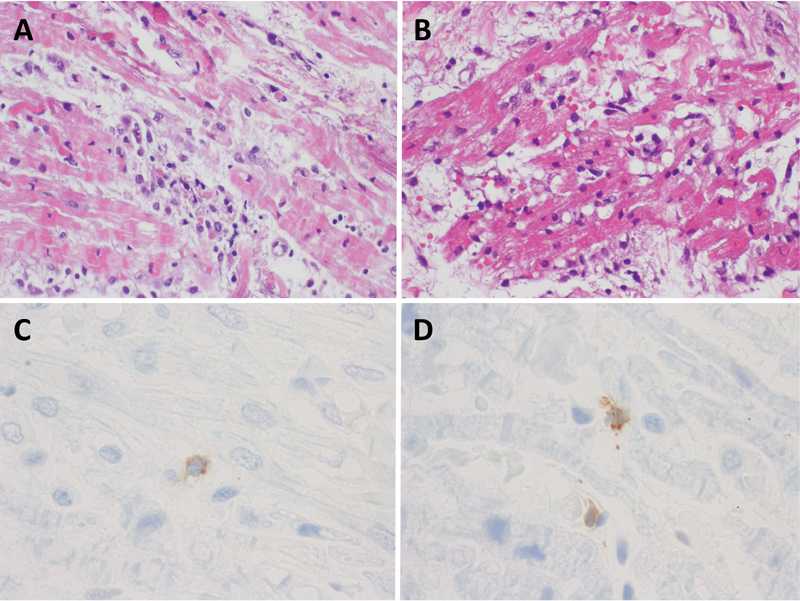

A cardiac biopsy was performed, and the results were consistent with myocarditis. Specifically, the histological examination demonstrated a mild interstitial fibrosis with a small focus of lymphocytes affecting the myocardial fibers ( Fig. 1A ) and diffuse areas of edema, recent hemorrhage, and scattered lymphocytes surrounding isolated myocardial fibers with hypertrophy ( Fig. 1B ). Immunoperoxidase staining for CD3 highlights T lymphocytes in different sections of the myocardium ( Fig. 1C and 1D ). Viral panel was ordered and resulted negative.

Fig. 1.

Myocardial biopsy demonstrating the following features: ( A ) Mild interstitial fibrosis and small foci of lymphocytes affecting myocardial fibers (hematoxylin-eosin; original magnification ×200). ( B ) Diffuse areas of edema, recent hemorrhage, and scattered lymphocytes surrounding myocardial fibers with hypertrophy (hematoxylin–eosin; original magnification ×200). ( C and D ) Immunoperoxidase staining for CD3, highlighting T lymphocytes in different sections of the myocardium (VENTANA Anti-CD3 [clone, 2GV6] original magnification ×1000).

Weaning was started according to protocols 7 days after initiating ECMO support. Once decannulated, the patient continued under Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) therapy during 9 days until renal function normalized. Right diaphragmatic palsy was observed and treated surgically with a diaphragmatic plication. After 50 days, the patient was discharged from hospital without neurological sequalae. Patient went home on diuretics with furosemide and spironolactone, and afterload reduction with enalapril.

Discussion

Our case is another example that ECMO may be safely utilized in patients with hemodynamic instability due to fulminant myocarditis. This finding was also recently reported in the international ELSO records. They reported the use of ECMO in 88 neonates and 443 children due to myocarditis with a survival rate of 50% for neonates and 71% for children 7 Rajagopal et al studied the use of extracorporeal life support (ECLS) fulminant myocarditis, reporting that 50% of patients needed ECMO. The principal cause was cardiac arrest refractory to conventional CPR and malignant arrhythmias, obtaining a survival of 42%. No guidelines have been established that mention the indications for eCPR due to refractory cardiac arrest. Most of the ECLS initiation depends on personal medical criteria. French Health Department Guidelines suggest that eCPR may be considered if patients have a low-flow time for 100 minutes. Survival rates increased if cardiac arrest was shorter than 28.7 ± 4.1 minutes, had increased pH levels and increased lactate levels. Risk factors that increased mortality rates were female gender, renal failure, and arrhythmias. It is important to have a left atrium drainage to have an adequate recovery of the affected myocardium. 8 9 10

Blood lactate has been considered as a risk factor for poor neurologic outcomes and mortality in patients who had CPR. 10 11 Wang et al made a retrospective study that included 340 patients undergoing conventional CPR and found that blood lactate levels < 9 mmol/L were related to survival. 12

According to recent studies, our patient had some of the risk factors related to bad prognosis and mortality such as gender, renal replacement therapy use, and arrhythmias. However, biochemical values such as normal pH and blood lactate less than 7 mmol/L before cannulation are associated with favorable outcomes. An important aspect of this case was to maintain invasive mean arterial blood pressure over 60 mm Hg during CPR, to preserve adequate cerebral and renal perfusion.

Fulminant myocarditis is also differentiated from the acute (nonfulminant) subtype in that there is a clear onset of symptoms of no more than 2 weeks prior to presentation, has severe signs of heart failure, and requires vasoactive support or mechanical support shortly after presentation. 13 Endomyocardial biopsy continues to be the gold standard in the diagnosis of myocarditis. 14 The Dallas criteria define myocarditis as the identification of inflammatory cell infiltrates (> 5 lymphocytes per high-power field) into de myocardium causing necrosis of the surrounding cardiomyocytes. 15 Low sensitivity and large variation in the interpretation of the biopsies led to an increase in the use of immunohistochemistry. 16 This case report illustrates an example of a case of fulminant myocarditis diagnosed by immunohistochemistry.

Histological classification of myocarditis helps identify the etiology and possible prognosis of the disease. 13 17 Lymphocytic myocarditis, as in this case, is the most common subtype that is characterized by inflammation with histological identification of lymphocytes, necrosis of myocytes, and fibrosis. 17 The myocardial lymphocytic infiltration may be secondary to a viral infection, an autoimmune process against connective tissue or idiopathic. Other types of myocarditis occur with less frequency in children: (1) Giant cell myocarditis is caused by an autoimmune mechanism and it is characterized by the presence of giant multinucleated cells associated with diffuse and multifocal inflammatory cell infiltrate composted of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils. 18 Giant cell myocarditis has a death or transplantation rate of 89% with a median survival of 5.5 months. 19 (2) Eosinophil myocarditis is characterized with degranulation of eosinophilic infiltrates often due to hypersensitivity to medications, parasites, or hypereosinophilic syndrome. 13 (3) Other less frequent subtypes of myocarditis have been described, such as neutrophilic or granulomatous. 20 All subtype may have overlapping signs on presentation, and may require different degrees of support or duration of illness. In the case of the lymphocytic subtype, full recovery is expected but with different support requirements. 20 In our case, the time between cardiac arrest and ECLS was 105 minutes. Although we had a rapid response of the ECMO team, a filled ECMO system was not available due to high costs. We lack as well an interdepartmental protocol for emergency response in this group of patients when eCPR is needed. Nevertheless, an important point for success in this situation was placing the cannulae for left atrium drainage, obtaining a good myocardium recovery corroborated by daily transthoracic cardiac ultrasound.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ECMO has recently been included for acute fulminant myocarditis treatment obtaining a good survival according to recent ELSO reports. eCPR may be an alternative treatment for patients with cardiac arrest refractory to conventional CPR. Prognosis factors at the beginning of the support have been established including pH and blood lactate levels, “low flow” phase time, malignant arrhythmias occurrence, and renal failure. Finally, a cannulae placement into left atrium for drainage in case of severe global ventricular cardiac failure is an important procedure for myocardial function recovery.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Canter C E, Simpson K E. Diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis in children in the current era. Circulation. 2014;129(01):115–128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghelani S J, Spaeder M C, Pastor W, Spurney C F, Klugman D. Demographics, trends, and outcomes in pediatric acute myocarditis in the United States, 2006 to 2011. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(05):622–627. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chew S P, Tham L P. Extracorporeal life support for cardiac arrest in a paediatric emergency department. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(03):e37–e38. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2014040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Caen A R, Berg M D, Chameides L. Part 12: pediatric advanced life support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18) 02:S526–S542. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young ; Council on Clinical Cardiology ; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing ; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia ; and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee . Marino B S, Tabbutt S, MacLaren G. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in infants and children with cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(22):e691–e782. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas N L, Coute R A, Hsu C H, Cranford J A, Neumar R W. Descriptive analysis of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest—an ELSO registry study. Resuscitation. 2017;119:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ELSO member centers . Barbaro R P, Paden M L, Guner Y S. Pediatric Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry International Report 2016. ASAIO J. 2017;63(04):456–463. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conseil français de réanimation cardiopulmonaire; Société française d'anesthésie et de réanimation; Société française de cardiologie; Société française de chirurgie thoracique et cardiovasculaire; Société française de médecine d'urgence; Société française de pédiatrie; Groupe francophone de réanimation et d'urgence pédiatriques; Société française de perfusion; Société de réanimation de langue française; French Ministry of Health.Guidelines for indications for the use of extracorporeal life support in refractory cardiac arrest Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 20092802182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Arrigo S, Cacciola S, Dennis M. Predictors of favourable outcome after in-hospital cardiac arrest treated with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2017;121:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Post-Arrest Research Consortium . Donnino M W, Andersen L W, Giberson T. Initial lactate and lactate change in post-cardiac arrest: a multicenter validation study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(08):1804–1811. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sydney ECMO Research Interest Group . Dennis M, McCanny P, D'Souza M. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for refractory cardiac arrest: a multicentre experience. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Q, Pan W, Shen L. Clinical features and prognosis in Chinese patients with acute fulminant myocarditis. Acta Cardiol. 2012;67(05):571–576. doi: 10.1080/ac.67.5.2174132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginsberg F, Parrillo J E. Fulminant myocarditis. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(03):465–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kindermann I, Barth C, Mahfoud F. Update on myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(09):779–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aretz H T. Myocarditis: the Dallas criteria. Hum Pathol. 1987;18(06):619–624. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schultheiss H P. [Dilated cardiomyopathy--a chronic myocarditis? New aspects on diagnosis and therapy] Z Kardiol. 1993;82 04:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganji M, Ruiz-Morales J, Ibrahim S. Acute lymphocytic myocarditis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15(07):517–518. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Brooks E G. Giant cell myocarditis: a brief review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(12):1429–1434. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0068-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators . Cooper L T, Jr, Berry G J, Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant-cell myocarditis--natural history and treatment. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(26):1860–1866. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper L T., Jr Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1526–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]