Abstract

N-Heterocyclic carbene and phosphine can be labeled as solid σ-donor ligands and can contribute to stable complexes. In addition, the constructed complex can accommodate a wide variety of applications, such as pharmaceutical products. In the light of this, a theoretical analysis was carried out on the existence of metal–drug interactions of group 11 metal ions in coordination with symmetrical unsaturated N-heterocyclic carbenes [NHC(R)(R′)] and monodentate phosphine (PR3). The R substitutes on N atoms in NHC and phosphines are identical, and R′ substitutes are located on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle complexes. All complexes are in general formula, [Tgt → ML] {where M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I), Tgt = 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranoside, L= [NHC(R)(R′)], and PR3; R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph} at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory. Findings show greater tolerance for the release of drugs in the presence of Ag(I) metal ions than the other metal ions studied here. Applying natural bond orbital (NBO), atoms in molecules (AIMs), energy decomposition analysis (EDA), and extended transition-state natural orbital for chemical valence (ETS-NOCV) analysis have been researched in order to ascertain the nature of M ← S and M ← C (M ← P) bonds in the complexes. Results have shown that σ donation from S to M atoms in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes is better and the π acceptor is weaker than the corresponding [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes.

1. Introduction

N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), which can be considered as ligands featuring a singlet carbon donor, possess a single lone-pair orbital at the carbon atom described as carbon (II). Furthermore, they are also known as potent σ-donor ligands in metal transition complexes.1−3 Taking this into account, the strong NHC σ-donor properties will contribute to the development of metal–NHC complexes with high chemical and thermal stability.4,5

Such complexes were initially synthesized by Öfele6 and Wanzlick7 nearly at the same time in 1968. In addition, in 1991,8 the first free carbene has been isolated by Arduengo. Nowadays, metal–NHC complexes have already been known to be a major area of research for the development of new metallodrugs because of their high stability and ease of derivatives. It is worth noting that the biological potential of metal–NHC complexes has been considered to be one of the most important areas in bio-organometallic chemistry.9−19

Regarding this subject, over the last few years, a lot of research has been done, a substantial number of papers have been published, and plenty of metal-transition complexes containing NHC ligands have been identified as possible antitumor products.9−16,18,21−24

Cisplatin and other platinum species have also been used in clinics considered effective anticancer medicines. The side effects, however, prompted scientists to look for new anticancer medicines. Recently, nonplatinum medications have gained a great deal of coverage as cancer chemotherapy to discover novel therapies of efficacy and clinical profiles.20

By virtue of the fact that the NHCs have potent σ-donating potential to be bound to metal ions like phosphine, N-heterocyclic carbene complexes have been considered as good alternatives to phosphine.21 In addition, imidazolium salt precursors are also more easily synthesized compared to phosphines. In addition, when NHC ligands and other metal ions are combined, the consequence is an interesting biological profile. In comparison, there seems to be a different process for metal–NHC complexes than platinum-based drugs that can hardly reach DNA.20,22−25

On the other hand, tertiary phosphines (PR3) are accessible ligands of numerous transition metals and nontransitional metal ions. By making modifications in R groups, the electronic and steric properties of phosphines can be modified systematically and consistently. In contrast to amines, phosphines are administered with unmatched features; that is, they act as π acids. Additionally, phosphine ligands can stabilize transition-metal ions in low oxidation states.26 A number of theoretical studies on the structure and function of metal ligand bonding in transition metals and nontransitional NHC complexes have recently been published.20−27

In this content, for first time, a comparative theoretical study on the effects of changing ligands {N-heterocyclic carbenes NHC(R)(R′) and monodentate phosphine PR3 and also metal ions [Cu(I), Ag(I), and Au(I)] on drug release and the nature of the metal–drug bond in some antitumor active complexes of coinage metal ions with N-heterocyclic carbenes [NHC(R)(R′)] and monodentate phosphine (PR3) with general formula [Tgt → ML], [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); Tgt = 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranoside; R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph] at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory is reported. In addition, R′ substitutes are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in NHC.

2. Computational Details

In this study, the [Tgt → Au(IPr)][IPr = bis-(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-imidazolin-2-ylidene] complex was applied using eight density functional methods, namely, B3LYP, BLYP, BP86, Cam-B3LYP, M06, M05-2X, M06-2X, and PBE in combination with D3 dispersion corrections is examined. Furthermore, the obtained structural results were compared with the equivalent experimental values gained by the X-ray structure.28

Results obtained using rms methodological findings suggest that PBE-D3, the most relevant function of the above-mentioned methods, has the largest association between quantitative and experimental structural data (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison between the Performances of Eight Density Functional Methods of Au–C and Au–S Bond Lengths (Å) of [Tgt → Au(NHC(2,6-Diisopropyl Phenyl)] Complex.

| method | Au–C (Å) | Au–S (Å) | rms |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3LYP-D3 | 2.027 | 2.328 | 0.040 |

| BLYP-D3 | 2.032 | 2.343 | 0.051 |

| BP86-D3 | 2.022 | 2.313 | 0.031 |

| CAM-B3LYP-D3 | 2.016 | 2.318 | 0.030 |

| M06-D3 | 2.026 | 2.333 | 0.043 |

| M05-2X-D3 | 2.004 | 2.309 | 0.020 |

| M06-2X-D3 | 2.047 | 2.341 | 0.057 |

| PBE-D3 | 2.008 | 2.314 | 0.025 |

| Expa | 1.986 | 2.287 |

Data derived from ref (29).

In this article, three types of complexes are reported with the formulas [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MP(R)3] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph]. Additionally, these substituents are given in the heterocycle (C4 and C5) on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Schematic Representation of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MP(R)3] Complexes [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-Diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph].

All calculations were carried out at the PBE-D3/def2TZVP level of theory using the GAUSSIAN 09 software.29 The vibrational frequency study reveals that the optimized structures at stationary points, determined at the same theoretical level, correspond to the local minima with no imaginary frequency.

In order to obtain bond properties, the AIM 2010 package was used. To perform AIM calculations, wave function files were generated from Gaussian output files at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.30

In this context, the objective was to conduct a natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis31 with the GAUSSIAN 09 internal module at the theoretical level32 described above. Energy decomposition analysis (EDA) measurements have been carried out to evaluate the nature of the bonding of S → M at the BP86-D3/TZ2P (ZORA)/PBE-D3/def2 TZVP level of theory using the ADF 2009.01 software package.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Studies

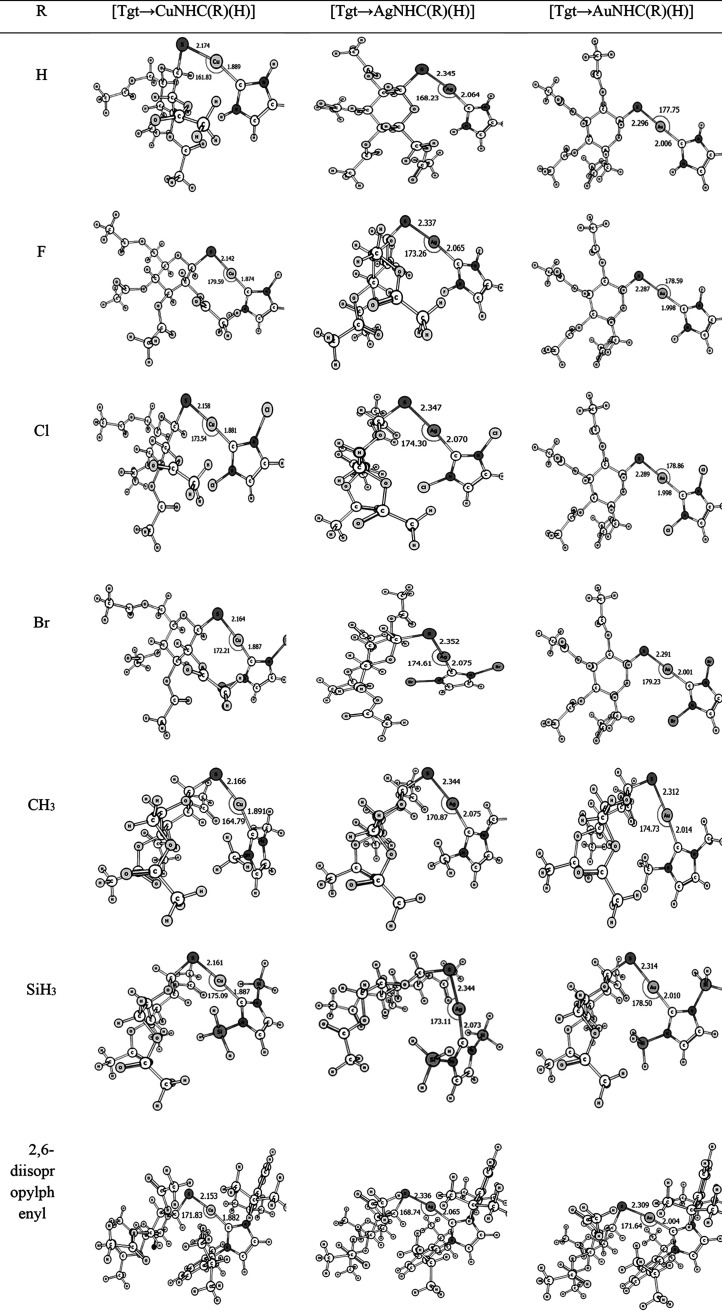

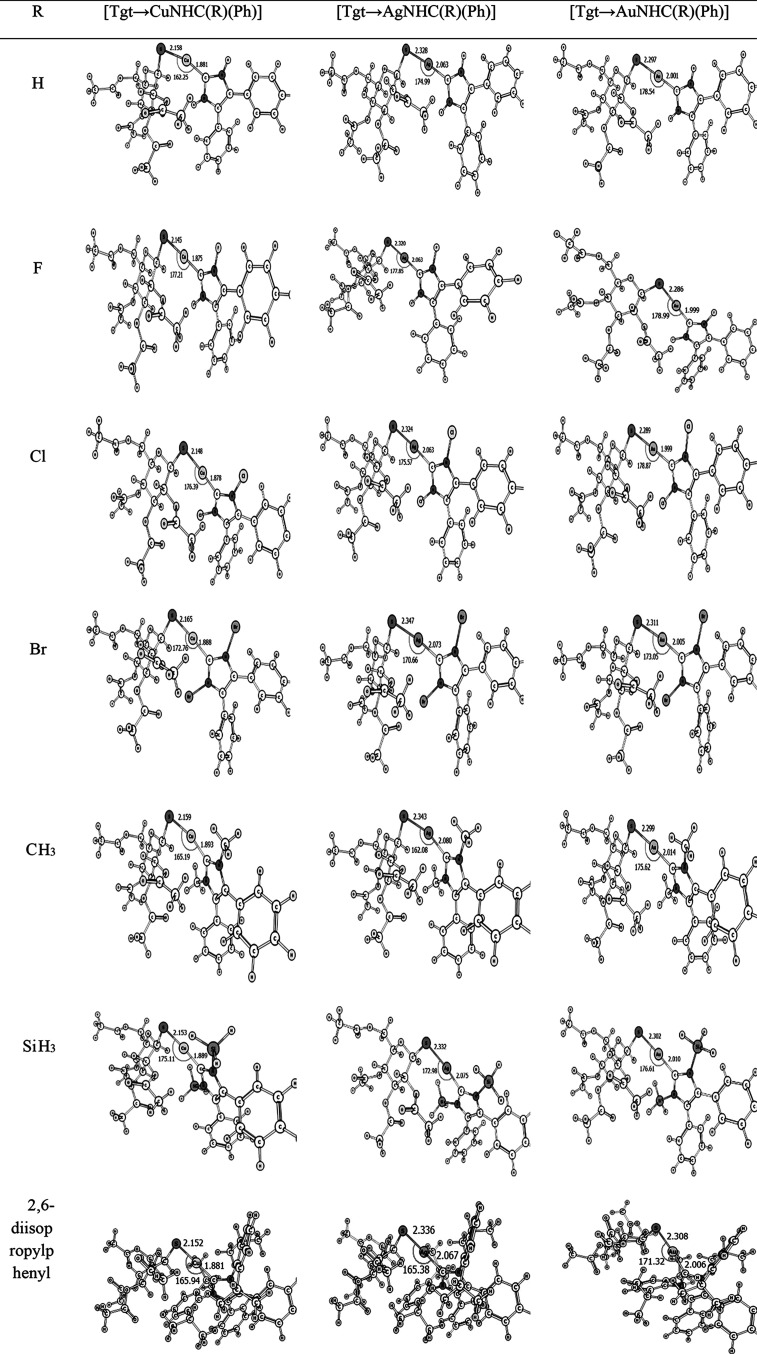

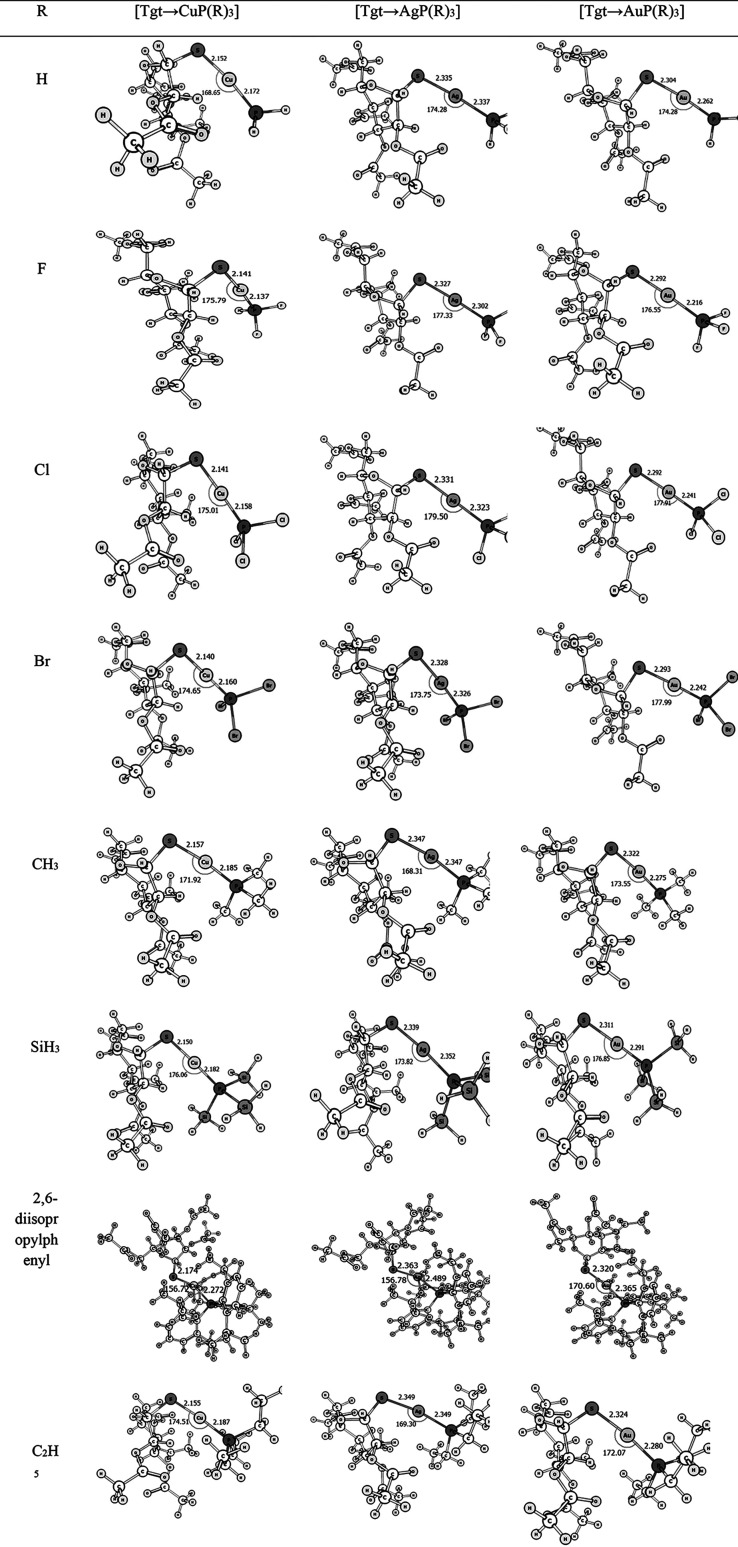

Figures 1–3 display the optimized configurations of [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph] [as these substitutes are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle complexes] at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory. As can be seen in Figures 1–3 and Table S1, the length of the M ← S bond is larger than the length of the M ← C bond in the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes, with different substituents. For example, in [Tgt → CuNHC(H)(H)] the value of M ← S and M ← C bonds is 2.17 Å and 1.89 Å, respectively. In addition, by changing the substituent R from F to Br, the bond lengths of M ← S and M ← C are slightly increased (see Figure 1–3 and Table S1).

Figure 1.

Optimized structures of [Tgt → MNHC(R)(H)][M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H] complexes of the investigated here at the mentioned level of theory.

Figure 3.

Optimized structures of[Tgt → MNHC(R)(Ph)][M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = Ph] complexes of the investigated here at the mentioned level of theory.

Figure 2.

Optimized structures of [Tgt → MP(R)3] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl] complexes of the investigated here at the mentioned level of theory.

On the other hand, by changing the R substituent from F to Br, in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes which are similar to M ← S and M ← C bond lengths in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes, the value of the M ← P bond length also increased marginally (see Figure 1–3 and Table S1).

Eventually, the minimum values of M ← C and M ← S bond lengths in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes are observed in [Tgt → CuNHC(F)(H)], which are approximately 1.87 and 2.14 Å, respectively.

In addition, we can see the smallest M ← P bond length in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes in the [Tgt → CuPF3] complex, which is approximately 2.14 Å.

Moreover, in [Tgt → CuP(X)3] (X = F, Cl, Br) complexes, the minimum value for M ← S bond length in the complexes is shown, which is approximately 2.14 Å (see Figures 1–3 and Table S1).

Results have shown that the modification of the R in [Tgt → MPR3] and R and R′ in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes has an insignificant effect on the M ← C, M ← P, and M ← S bond lengths values (see Figures 1–3 and Table S1).

3.2. Interaction Energy

Uncorrected interaction energies (ΔEint) between [MNHC(R)(R′)]+ and [MPR3]+ with [Tgt]−fragments in the optimized structure of [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] {M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph [as these substitutes are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle]} were calculated at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory. The interaction energy was measured according to the following equation

From this perspective, it should be said that EAB represents the electrical energy of [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes and EABA and EAB represent the electrical energies of the two interactive fragments in the optimized structure of the complexes. The uncorrected ΔEint for all complexes is shown in Table S5.

Furthermore, the objective was to gain correct results on the basis of the fixed superposition error (BSSE) and to use the counterpoise method, as proposed by Boys and Bernardi (see Tables S2–S4).33 In this sense, to minimize the BSSE, this procedure can determine a correction term using the same basis set for the molecule and its subunits. The theoretically corrected and uncorrected ΔEint for all of the complexes analyzed is given in Tables 2 and S5, respectively.

Table 2. Corrected ΔEint (kcal mol–1) Considering the BSSE Values for [Tgt → M-NHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → M{P(R)3}] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-Diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph] at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP Level of Theory.

| ΔEint | [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] | [Tgt→CuP(R)3] | [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(Ph)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | M | ΔEint (kcal mol–1) | ||

| H | Cu | –156.89 | –162.81 | –150.11 |

| Ag | –145.66 | –154.45 | –136.05 | |

| Au | –161.74 | –173.07 | –152.30 | |

| F | Cu | –157.34 | –179.49 | –150.27 |

| Ag | –149.05 | –170.88 | –136.05 | |

| Au | –166.37 | –192.99 | –158.97 | |

| Cl | Cu | –155.84 | –171.31 | –147.79 |

| Ag | –148.69 | –161.94 | –137.03 | |

| Au | –161.57 | –181.02 | –155.15 | |

| Br | Cu | –156.20 | –169.50 | –148.85 |

| Ag | –147.74 | –157.00 | –138.79 | |

| Au | –159.63 | –177.78 | –156.28 | |

| CH3 | Cu | –153.68 | –151.27 | –148.35 |

| Ag | –145.03 | –140.36 | –137.93 | |

| Au | –159.07 | –154.07 | –150.39 | |

| SiH3 | Cu | –155.92 | –153.35 | –145.74 |

| Ag | –144.89 | –142.61 | –135.08 | |

| Au | –161.70 | –158.65 | –151.16 | |

| 2,6-diisopropyl phenyl | Cu | –148.03 | –133.06 | –145.13 |

| Ag | –137.22 | –124.87 | –134.06 | |

| Au | –154.13 | –138.05 | –149.00 | |

| C2H5 | Cu | –148.55 | ||

| Ag | –136.38 | |||

| Au | –151.45 | |||

When we have the same M atom and R substituent (R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl) in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)]complexes and when the R′ from H is changed in to Ph for noncarbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle, we also observed a decrease in the value of ΔEint. In this sense, in the case of [Tgt → CuNHC(H)(R′)], ΔEint values in the presence of R′ = H and Ph are about 156.9 and 150.1 kcal mol–1, respectively.

In addition, the ΔEint values of metal–drug (M ← S) bond in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are significant and support the well-known V-shape pattern for the transition metals of the first, second, and third rows as described in the following order: Ag(I) < Cu(I) < Au(I) (see Table 2).

In addition, the same findings concerning the bond interaction of NHC(R) with Group 11 of the transition-metal ions are identified with our group and also with the Frenking group.34,35 Findings demonstrate that the Ag(I) complexes have the smallest and Au(I) complexes have the highest levels of metal–drug interaction strength. As a result, relative to other complexes studied here, drug releases tend to be best promoted in Ag(I) complexes.

Moreover, considering the same M atom and changing the L ligand from NHC(R)(R′) to PR3 for electron-withdrawing substituents, that is, F, Cl, Br, and H, the strength of M ← S bond in [Tgt → ML] was increased. In this respect, in the case of [Tgt → CuL], ΔEint values in the presence of NHC(H)(H/Ph) are approximately 156.9 and 150.1 kcal mol–1 and by changing the L ligand group to PH3, ΔEint is approximately 162.8 kcal mol–1 (see Table 2).

Drug releases appear to be more facilitated in the presence of NHC(R)(Ph) ligands than other PR3 ligands studied here. In addition, as mentioned above, the ΔEint value of metal–drug (M ← S) bond in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)], in the presence of R′ = H, is larger than that of R′ = Ph.

In various complexes, the effects of R substituted on NHC(R)(R′) and PR3 ligands are also regarded. Results demonstrate that ΔEint values of the metal–drug (M ← S) bond in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes, in the presence of electron-withdrawing substituents (R = F, Cl, Br) are more significant than those for the electron-donating substituents (R = H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2, 6-diisopropylphenyl) (see Table 2).

It is also noteworthy that, taking into account the same M atom and R substituent, the differences between ΔEint of the metal–drug (M ← S) bond in the presence of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are more substantial than those of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes. In this regard, it must be emphasized that the difference between ΔEint of the metal–drug (M ← S) bond in [Tgt → CuPR3] complexes with R = H and F is approximately 17 kcal mol–1 and that for [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H/Ph)] complexes is approximately 1 kcal mol–1 (see Table 2).

Finally, it can be inferred that among the [Tgt → AuMNHC(R)(R′)] complexes studied here, [Tgt → AgNHC(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)(Ph)] and [Tgt → AuNHC(F)(H)] have the smallest and largest amounts of interaction energies, respectively. On the other hand, in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes, the [Tgt → AgP(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)3] and [Tgt → AuPF3] have the smallest and largest values of ΔEint of the metal–drug (M ← S) bond, respectively.

The analysis of the associated findings shows that the highest quantity of ΔEint in the complexes corresponds to the electron-withdrawing substitutions F and Au ions of metal and that the smallest quantity corresponds to the electron-donating substituents 2,6-diisopropylphenyl and Ag ions of metal (see Table 2).

Consequently, it can be inferred that in the presence of the same M metal ion and R = F, Cl, Br, and H substituents, the group 11 metals can generate stronger bonds with [Tgt]− drug in the form [Tgt → MPR3] than [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes (see Table 2).

3.3. AIM Analysis

Bader’s theory of atoms in molecules (AIM theory) was used to investigate the bond critical points (BCPs). In the present paper, we attempt to analyze the BCPs at M ← C and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] as well as M ← P and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MPR3] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph] [as these substituents are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle] complexes using AIM theory.

As can be seen in Tables S6–S8, the topological properties of the interactions have been calculated at the BCPs. The ∇2ρ (laplacian of electron density) and −Gc/Vc (Gc is the kinetic energy and a positive quantity, Vc is the potential energy and a negative quantity) values have also been used to study the nature of the interaction.34 The effects of the substituents on the values of electron density (ρ) of M ← C and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] as well as M ← P and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MPR3] are also investigated.

According to the acquired findings, it can be argued that the changing in the R substituents may not have a significant impact on the electron density values (ρ) of on M ← C, M ← P and M ← S bonds studied here (see Tables S6–S8).

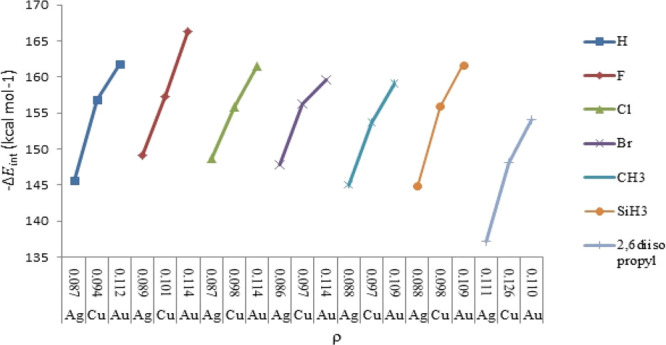

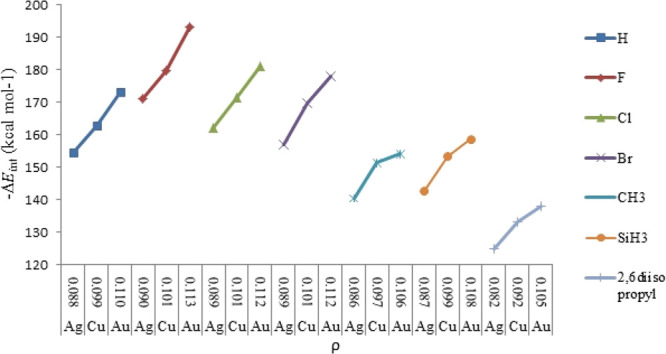

Figures 4 and 5 represent a satisfactory correlation between the calculated ΔEint and the corresponding electron density (ρ) for the M ← S bond in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes.

Figure 4.

Calculated ΔEint vs electron density (ρ) for the M–S bond of [Tgt → MNHC(R)(H)] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H].

Figure 5.

Calculated ΔEint vs electron density (ρ) for the M–S bond of [Tgt → MPR3][M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl].

The aforementioned results, which are strongly in agreement with ΔEint, confirm the well-known V-shaped trends of electron densities (ρ) of M ← C and M ← S bonds in the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complex and the same is for M ← P and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MPR3]{M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph [as these substituents are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle]} complexes (see Tables S6–S8).

Subsequently, it has been observed that the smallest and largest electron density (ρ) values in the presence of the same R substituent for M ← C and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] as well as M ← P and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MPR3] are associated with Ag and Au complexes, respectively (see Tables S6–S8).

The values of ∇2ρ and −Gc/Vc have also been used to analyze the nature of the interactions in the complexes.36,37 The results indicate that the M ← C and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] as well as M ← P and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are partly covalent (∇2ρ > 0 and −Gc/Vc < 1, see Tables S6–S8).

3.4. NBO Analysis

The natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis, which focuses on a technique for optimizing the transformation of a given wave function into a localized shape, corresponds to the Lewis structure of the chemist’s one-center “lone pair” and two-center “bond” elements.

Assuming that the Lewis structures are bonding templates, the NBO approach was commonly accepted as understanding the bonding state. It is worth noting that the results obtained are very robust to the alteration of the basis set, which is the most significant advantage of the NBO analysis.

Based on NBO calculations at the PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory, the nature of M ← C, M ← S, and M ← P bonds in the complexes studied here is analyzed. The values of the partial charge on S and M atoms and also the total charge of [Tgt]- fragment in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] as well as [Tgt → MPR3] {M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph [as these substituents are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle]} complexes are investigated (see Table 3).

Table 3. WBIs of M–C and M–S Bonds and Natural Charges of M and S Atoms and [Tgt]− Fragment in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MP(R)3] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-Diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph] Complexes at the PBE-D3/def2TZVP Level of Theory.

| [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] |

[Tgt → CuP(R)3] |

[Tgt → CuNHC(R)(Ph)] |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | M | WBI M–C | WBI M–S | M | [Tgt]− | S | WBI M–P | WBI M–S | M | [Tgt]− | S | WBI M–C | WBI M–S | M | [Tgt]– | S |

| H | Cu | 0.629 | 0.686 | 0.293 | –0.533 | –0.302 | 0.615 | 0.773 | 0.242 | –0.240 | –0.355 | 0.627 | 0.703 | 0.297 | –0.528 | –0.303 |

| Ag | 0.555 | 0.635 | 0.286 | –0.531 | –0.320 | 0.495 | 0.681 | 0.308 | –0.204 | –0.392 | 0.546 | 0.674 | 0.269 | –0.517 | –0.307 | |

| Au | 0.646 | 0.693 | 0.186 | –0.450 | –0.248 | 0.610 | 0.729 | 0.156 | –0.257 | –0.320 | 0.654 | 0.715 | 0.159 | –0.423 | –0.240 | |

| F | Cu | 0.606 | 0.749 | 0.329 | –0.489 | –0.293 | 0.783 | 0.819 | 0.099 | –0.329 | –0.339 | 0.600 | 0.739 | 0.330 | –0.499 | –0.297 |

| Ag | 0.493 | 0.663 | 0.318 | –0.511 | –0.305 | 0.658 | 0.714 | 0.169 | –0.297 | –0.373 | 0.505 | 0.702 | 0.302 | –0.497 | –0.301 | |

| Au | 0.631 | 0.730 | 0.221 | –0.413 | –0.228 | 0.773 | 0.732 | 0.051 | –0.325 | –0.315 | 0.632 | 0.754 | 0.184 | –0.390 | –0.220 | |

| Cl | Cu | 0.629 | 0.721 | 0.310 | –0.497 | –0.289 | 0.621 | 0.799 | 0.247 | –0.181 | –0.335 | 0.624 | 0.731 | 0.314 | –0.500 | –0.290 |

| Ag | 0.505 | 0.647 | 0.284 | –0.498 | –0.299 | 0.478 | 0.695 | 0.312 | –0.154 | –0.373 | 0.516 | 0.683 | 0.273 | –0.497 | –0.297 | |

| Au | 0.653 | 0.725 | 0.188 | –0.410 | –0.224 | 0.644 | 0.744 | 0.150 | –0.198 | –0.290 | 0.652 | 0.749 | 0.146 | –0.387 | –0.215 | |

| Br | Cu | 0.619 | 0.706 | 0.304 | –0.479 | –0.290 | 0.592 | 0.792 | 0.279 | –0.143 | –0.329 | 0.617 | 0.703 | 0.304 | –0.490 | –0.292 |

| Ag | 0.499 | 0.637 | 0.270 | –0.476 | –0.298 | 0.439 | 0.703 | 0.302 | –0.132 | –0.349 | 0.511 | 0.648 | 0.260 | 0.484 | –0.299 | |

| Au | 0.644 | 0.721 | 0.173 | –0.408 | –0.219 | 0.626 | 0.744 | 0.166 | –0.143 | –0.280 | 0.646 | 0.720 | 0.123 | –0.384 | –0.216 | |

| CH3 | Cu | 0.614 | 0.682 | 0.281 | –0.548 | –0.307 | 0.642 | 0.731 | 0.188 | –0.335 | –0.373 | 0.619 | 0.710 | 0.286 | –0.526 | –0.299 |

| Ag | 0.522 | 0.632 | 0.259 | –0.529 | –0.310 | 0.515 | 0.637 | 0.239 | –0.297 | –0.397 | 0.523 | 0.651 | 0.269 | –0.520 | –0.307 | |

| Au | 0.642 | 0.699 | 0.128 | –0.432 | –0.229 | 0.636 | 0.708 | 0.055 | –0.376 | –0.315 | 0.646 | 0.731 | 0.123 | –0.412 | –0.230 | |

| SiH3 | Cu | 0.604 | 0.694 | 0.309 | –0.521 | –0.304 | 0.499 | 0.757 | 0.302 | –0.192 | –0.368 | 0.617 | 0.731 | 0.304 | –0.501 | –0.290 |

| Ag | 0.490 | 0.627 | 0.274 | –0.510 | –0.314 | 0.385 | 0.678 | 0.341 | –0.165 | –0.388 | 0.507 | 0.672 | 0.272 | –0.496 | –0.299 | |

| Au | 0.637 | 0.713 | 0.145 | –0.406 | –0.219 | 0.537 | 0.775 | 0.127 | –0.247 | –0.284 | 0.646 | 0.743 | 0.131 | –0.389 | –0.217 | |

| Cu | 0.607 | 0.718 | 0.301 | –0.515 | –0.297 | 0.506 | 0.692 | 0.257 | –0.551 | –0.408 | 0.588 | 0.716 | 0.333 | –0.514 | –0.301 | |

| 2,6-diisopropyl phenyl | Ag | 0.469 | 0.640 | 0.254 | –0.512 | –0.316 | 0.339 | 0.624 | 0.234 | –0.540 | –0.427 | 0.451 | 0.643 | 0.279 | –0.500 | –0.317 |

| Au | 0.639 | 0.747 | 0.092 | –0.395 | –0.211 | 0.545 | 0.756 | –0.006 | –0.404 | –0.298 | 0.626 | 0.742 | 0.134 | –0.402 | –0.212 | |

| C2H5 | Cu | 0.641 | 0.730 | 0.177 | –0.345 | –0.376 | ||||||||||

| Ag | 0.507 | 0.613 | 0.225 | –0.319 | –0.411 | |||||||||||

| Au | 0.643 | 0.703 | 0.036 | –0.404 | –0.323 | |||||||||||

As can be seen in Table 3, acquired findings demonstrate that the M atoms carried positive charge {except for Au in [Tgt → AuP(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)3] complex} and S atom and [Tgt]- fragment carried the negative charges in the complexes.

Furthermore, in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes, changing the M atom from Cu to Au in the presence of the same R and R′ substituents leads to a reduction of the values of partial positive charge on the M atom; Cu(I) > Ag(I) > Au(I). Furthermore, there is no major impact on the amount of the partial charge on the M atom by adjusting the substituent R. In addition, in the presence of the same M metal center, changing the R substituent from F to Br leads to a slight decrease in the value of the partial positive charge on M atoms.

For example, the partial positive charge values for Cu atom in [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] complexes concerning R = F, Cl, and Br are approximately 0.329e, 0.310e, and 0.304e, respectively (see Table 3).

Changing the M metal center in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes in the presence of the same R substituent results in increasing the partial positive charge values from Cu to Ag and then decreasing the value from Ag to Au, respectively (except for R = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl).

Moreover, in the presence of the Cu and Au metal centers and changing the R substitutes from F to Br and also the partial natural charge value on M in [Tgt → MPR3], unlike those obtained for [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(R′)] complexes increased. For, for example, in the presence of F, Cl, and Br, the partial positive charge values for Cu atoms [Tgt → CuPR3] are approximately 0.099e, 0.247e, and 0.279e, respectively (see Table 3).

It is worth mentioning that in the presence of the same R substituent in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(H)], the partial natural charge value on the M metal center for M = Cu and Au is slightly larger than that in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes.

For example, the partial natural charge values on Cu atoms in [Tgt → CuNHC(H)(H)] and [Tgt → CuPH3] are about 0.293 and 0.242, respectively.

Notwithstanding, the largest charge values on the M metal center in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are found in [Tgt → CuNHC(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)(Ph)] and [Tgt → AgP(SiH3)3] complexes, whereas the smallest values can be found in [Tgt → AuNHC(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)(H)] and [Tgt → AuP (2,6-diisopropyl phenyl)3] complexes, respectively.

It is worthy of note that the partial negative natural charge value of S atoms in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes has also been addressed. The data confirm that the partial negative natural charge values of S atoms in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are larger than those in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes (See Table 3).

Charge-transfer (CT) values from [Tgt]− to [MNHC(R)(R′)]+ and [MPR3]+ fragments in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are also analyzed.

As can be seen in Table 3, the CT values in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes, in the presence of the same M metal center and R substitution, are greater than those in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes, except for the 2,6-diisopropylphenyl substituent.

Results also demonstrate that, by changing the R substituent from the electron-donating to the electron-withdrawing groups, the values of CT are almost reduced in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes (see Table 3). On the other hand, the maximum and minimum amounts of the CT in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] are found for [Tgt → CuNHC(CH3)(H)] and [Tgt → AuNHC(Br)(Ph)] complexes, respectively.

In [Tgt → MPR3] complexes, the maximum and minimum amounts of the CT are also found in the case of [Tgt → CuP(2,6-diisopropyl phenyl)3] and [Tgt → AgP(Br)3] complexes, respectively.

Finally, in the case of [Tgt → MPR3] complexes, the well-known v-shaped attitude is shown for the CT values by considering the same R substituent and by changing the M metal center from Cu to Au in most cases and in compliance with the interaction energies (ΔEint) in the following order: Ag < Cu ∼ Au.

Using the Wiberg bond index (WBI) method, the chemical bond orders of M ← P and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes and M ← C and M ← S bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] are also evaluated and as can be seen, the results are compared in the Table 3.

The obtained results have shown that by changing the M metal center in the presence of the same R and R′ substituents in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes, which are in good agreement with the interaction energies (ΔEint), the well-known v-shaped attitude is shown for the WBI values of the M ← C bond in the following order: Ag (I) < Cu (I) < Au (I). Moreover, it is found that changing the R′ substituent has no significant effect on the WBI values of M ← C bonds (see Table 3).

Afterward, by changing the R substituent from electron-donating to electron-withdrawing substituent, we can see an increase in the values of WBI’s M ← S in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(H)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes.

Generally, the values of WBI’s M ← S in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are slightly larger than those in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(H)] complexes; Nonetheless, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl complexes are some examples of their exceptions. The obtained data showed that the smallest values of WBIs for M ← C and M ← P bonds in the complexes are found in [Tgt → AgNHC(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)(Ph)] and [Tgt → AgP(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)3] complexes and those for M ← S bonds are found in [Tgt → AgNHC(SiH3)(H)] and [Tgt → AgP)C2H5)] complexes.

Based on the above findings, which are in good agreement with the metal–drug (M ← S) bond ΔEint, it can be concluded that in comparison with PR3 ligands and Cu and Au metal centers in the complexes examined here, drug releases are better facilitated in the presence of the majority of NHC(R)(R) ligands and Ag metal center. Conversely, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl complexes can be considered as exceptions.

The Fock matrix has been used in this sense to analyze donor–acceptor interactions based on an NBO analysis.

Tables S9–S20 demonstrate the values of the donor–acceptor interactions as well as natural hybrid orbital (NHO) analysis for the electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents on the complexes investigated, and also the results of natural hybrid orbital (NHO) analysis between the M metal center and S, P, and C atoms in M ← S, M ← P, and M ← C bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are represented. Apart from that, the occupancy of S, P, and C atoms in the latter bonds are ≃80% in the presence of Cu(I) and Ag(I), and ≃70% in the presence of Au(I) metal centers, respectively. The proof obtained confirmed the existence of σ bonding interactions between the lone pair of sulfur and the carbon atoms of [Tgt]− and carbene as the Lewis base to the empty orbitals of the M-metal center as the Lewis acid (see Tables S9–S17). The modification of the R substituent does not have a significant impact on the occupancy values of S, P, and C atoms in the latter bonds in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] [M = Cu(I), Ag(I), and Au(I)] complexes (see Tables S9–S17). It is also worth noting that the results of the second-order perturbation theory analysis showed that the σ* and Lp* orbitals of the M metal center in M ← S, M ← P, and M ← C bonds are filled with lone-pair electrons of S, P, and C atoms as the σ orbitals of M ← S, M ← P, and M ← C bonds [M = Cu(I)]. In this sense, Ag (I) and Au (I) in the complexes can be attributed to the π-back-donation (see Tables S18–S20).

3.5. EDA Analysis

Energy decomposition analysis (EDA) for obtaining information on driving forces contributing to the molecular structure and reactivity should be seen as an essential tool for the quantitative interpretation of chemical bonds. In this regard, the nature of metal–ligand bonds is analyzed by partitioning the bonds into ionic and covalent components.33

It should be noted that the energy decomposition analysis (EDA), developed by Morokuma38 and Ziegler,39,40 is in conjunction with the charging decomposition method; Natural Orbital for Chemical Valence (NOCV).41,42

In order to analyze the nature of the bond in organic and inorganic compounds, the EDA focuses on the instantaneous energy interaction (ΔEint) of two or more chemical bonds between the fragments in the specific electronic reference state and the frozen molecular geometry.43,44

The interaction energy can be divided into four main components eq 1.

| 1 |

where ΔEelstat is the electrostatic interaction, ΔEorb is the orbital interaction, ΔEpauli is Pauli repulsion, and ΔEdisp is the dispersion energy between the two investigated fragments.

In this research, the bonding analysis is defined as the interaction between [MNHC(R)(R)]+ and [MPR3]+ with [Tgt]- fragments in the related optimized structures.

According to this analysis, the optimized structure of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] {M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph [as these substituents are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle]} complexes (Scheme 1) are performed with BP86-D3/TZ2P(ZORA)//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP and the program package ADF2009.01. As can be seen in Tables 4–6, the results obtained indicate that ΔEint values of the studied complexes are identical to those obtained at PBE-D3/def2-TZVP.

Table 4. EDAa Analysis (BP86-D3/TZ2P(ZORA)//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP) of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MP(R)3] Complexes [M = Cu(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-Diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph].

| R | [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] | [Tgt → CuP(R)3] | [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(Ph)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | ΔEint | –161.86 | –168.07 | –155.73 |

| ΔEpauli | 105.91 | 104.27 | 106.93 | |

| ΔEelast | –188.69 (70.50%) | –190.64 (70.0%) | –180.96 (68.90%) | |

| ΔEorb | –69.5 (26.00%) | –73.47 (27.0%) | –69.76 (26.56%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –9.58 (3.60%) | –8.22 (3.1%) | –11.94 (2.51) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –34.52 | –43.14 | –35.00 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –23.40 | –15.72 | –22.12 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –10.43 | –10.50 | –11.50 | |

| F | ΔEint | –162.61 | –186.72 | –155.63 |

| ΔEpauli | 95.31 | 105.00 | 96.68 | |

| ΔEelast | –181.21 (70.30%) | –199.01 (68.3%) | –174.35 (69.10%) | |

| ΔEorb | –70.02 (27.20%) | –83.20 (28.6%) | –69.90 (27.70%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –6.69 (2.60%) | –9.51 (3.3%) | –8.07 (3.20%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –37.20 | –47.92 | –36.40 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –24.43 | –23.00 | –24.25 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –9.40 | –12.14 | –10.25 | |

| Cl | ΔEint | –160.32 | –177.17 | –153.55 |

| ΔEpauli | 99.46 | 106.68 | 98.61 | |

| ΔEelast | –181.87 (70.00%) | –192.37 (67.8%) | –173.02 (68.62%) | |

| ΔEorb | –69.10 (26.60%) | –81.46 (28.7%) | –69.19 (27.44%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –8.81 (3.40%) | –10.02 (3.6%) | –9.95 (3.95%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –35.61 | –47.09 | –34.65 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –22.55 | –21.15 | –23.18 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –9.92 | –11.35 | –8.16 | |

| Br | ΔEint | –161.51 | –175.32 | –155.55 |

| ΔEpauli | 104.57 | 107.81 | 103.22 | |

| ΔEelast | –184.49 (69.4%) | –190.63 (67.40%) | –175.86 (67.96%) | |

| ΔEorb | –71.85 (27.0%) | –81.55 (28.80%) | –71.34 (27.57%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –9.73 (3.70%) | –10.96 (3.90%) | –11.56 (4.47%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –34.50 | –47.17 | –30.80 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –26.16 | –17.59 | –25.19 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –11.91 | –11.57 | –10.47 | |

| CH3 | ΔEint | –157.72 | –154.84 | –154.42 |

| ΔEpauli | 103.39 | 107.08 | 107.41 | |

| ΔEelast | –185.41 (71.00%) | –182.54 (69.7%) | –177.48 (67.79%) | |

| ΔEorb | –64.87 (24.90%) | –69.66 (26.6%) | –69.38 (26.50%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –10.83 (4.20%) | –9.72 (3.8%) | –14.96 (5.71%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –32.76 | –41.04 | –34.94 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –19.71 | –13.73 | –22.12 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –11.74 | –10.61 | –12.74 | |

| SiH3 | ΔEint | –160.25 | –156.51 | –151.68 |

| ΔEpauli | 99.97 | 104.82 | 102.48 | |

| ΔEelast | –181.85 (69.90%) | –180.74 (69.0%) | –172.14 (67.73%) | |

| ΔEorb | –67.44 (26.00%) | –71.24 (27.20%) | –69.49 (27.34%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –10.92 (4.20%) | –9.36 (3.60%) | –12.53 (4.93%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –33.74, | –42.22 | –35.32 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –19.99 | –13.92 | –22.22 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –11.21 | –10.38 | –10.11 | |

| 2,6-diisopropyl phenyl | ΔEint | –151.41 | –139.97 | –152.27 |

| ΔEpauli | 107.77 | 116.02 | 111.43 | |

| ΔEelast | –174.03 (67.20%) | –165.89 (64.80%) | –172.85 (65.55%) | |

| ΔEorb | –67.70 (26.20%) | –69.20 (27.03%) | –68.80 (26.09%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –17.45 (6.80%) | –20.90 (8.16%) | –22.06 (8.37%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –33.55 | –40.49 | –33.04 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –21.62 | –12.48 | –22.31 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –13.63 | –14.17 | –14.16 | |

| ΔEint | –153.03 | |||

| ΔEpauli | 108.76 | |||

| ΔEelast | –179.56 (68.4%) | |||

| C2H5 | ΔEorb | –68.75 (26.2%) | ||

| ΔEdisper | –14.39 (5.5%) | |||

| ΔEorb,σ | –40.60 | |||

| ΔEorb,π | –13.34 | |||

| ΔEorb,rest | –10.52 |

All energy values are at kcal mol–1.

Table 6. EDAa Analysis (BP86-D3/TZ2P(ZORA)//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP) of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MP(R)3] Complexes [M = Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-Diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph].

| R | Tgt → AuNHC(R)(H) | Tgt → AuP(R)3 | Tgt → AuNHC(R)(Ph) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | ΔEint | –163.71 | –177.38 | –156.91 |

| ΔEpauli | 147.40 | 148.73 | 149.84 | |

| ΔEelast | –216.39 (69.55%) | –226.53 (72.80%) | –209.74 (68.37%) | |

| ΔEorb | –86.03 (27.65%) | –90.40 (24.70%) | –86.69 (26.69%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –8.69 (2.79%) | –9.17 (2.50%) | –10.32 (3.37%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –53.78 | –62.66 | –53.44 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –23.62 | –16.23 | –23.95 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –8.11 | –8.42 | –10.34 | |

| F | ΔEint | –163.03- | –198.73 | –161.07 |

| ΔEpauli | 143.84 | 150.58 | 151.01 | |

| ΔEelast | –217.93 (69.70%) | –238.17 (68.20%) | –214.05 (68.59%) | |

| ΔEorb | –89.31 (28.60%) | –101.38 (29.10%) | –90.19 (28.90%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –5.63 (1.80%) | –9.76 (2.80%) | –7.84 (2.51%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –55.30 | –67.37 | –54.80 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –25.75 | –20.32 | –26.03 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –8.92 | –10.35 | –10.40 | |

| Cl | ΔEint | –163.80 | –186.60 | –157.63 |

| ΔEpauli | 145.42 | 154.55 | 152.09 | |

| ΔEelast | –215.28 (69.70%) | –229.49 (67.30%) | –212.09 (68.84%) | |

| ΔEorb | –87.77 (28.40%) | –101.61 (29.80%) | –88.79 (28.67%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –6.17 (2.00%) | –10.05 (3.00%) | –8.83 (2.85%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –54.05 | –69.61 | –53.61 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –25.49 | –18.61 | –25.44 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –9.13 | –9.86 | –10.61 | |

| Br | ΔEint | –161.71 | –182.57 | –159.82 |

| ΔEpauli | 145.58 | 156.70 | 154.54 | |

| ΔEelast | –213.72 (69.50%) | –226.84 (66.90%) | –213.26 (67.84%) | |

| ΔEorb | –87.03 (28.32%) | –101.96 (30.10%) | –89.34 (28.42%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –6.55 (2.10%) | –10.46 (3.10%) | –11.76 (3.74%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –53.46 | –69.58 | –51.39 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –24.58 | –18.10 | –25.40 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –9.65 | –10.00 | –10.82 | |

| CH3 | ΔEint | –160.63 | –158.60 | –152.76 |

| ΔEpauli | 149.02 | 158.35 | 153.84 | |

| ΔEelast | –216.84 (69.60%) | –216.36 (68.30%) | –210.29 (68.59%) | |

| ΔEorb | –82.43 (26.50%) | –86.36 (27.30%) | –86.50 (28.21%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –10.39 (4.10%) | –14.24 (4.50%) | –9.82 (3.20%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –49.56 | –58.04 | –52.72 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –21.22 | –13.63 | –23.37 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –10.69 | –12.57 | –10.74 | |

| SiH3 | ΔEint | –165.90 | –162.85 | –153.89 |

| ΔEpauli | 150.06 | 159.45 | 153.09 | |

| ΔEelast | –217.41 (68.80%) | –217.55 (67.50%) | –208.54 (67.93%) | |

| ΔEorb | –85.08 (27.00%) | –89.98 (28.00%) | –87.52 (28.51%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –13.53 (4.30%) | –14.77 (4.60%) | –10.92 (3.56%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –50.73 | –61.52 | –52.85 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –21.66 | –13.86 | –23.32 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –12.04 | –10.57 | –11.65 | |

| 2,6-diisopropyl phenyl | ΔEint | –156.25 | –141.76 | –151.75 |

| ΔEpauli | 156.86 | 164.97 | 157.36 | |

| ΔEelast | –210.25 (67.20%) | –200.14 (65.25%) | –206.60 (66.84%) | |

| ΔEorb | –84.61 (27.10%) | –87.16 (28.42%) | –84.68 (27.39%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –18.25 (5.90%) | –19.43 (6.33%) | –17.83 (5.77%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –50.08 | –61.50 | –49.76 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –22.58 | –11.42 | –22.45 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –13.53 | –12.21 | –13.40 | |

| ΔEint | –153.07 | |||

| ΔEpauli | 158.47 | |||

| ΔEelast | –213.88 (68.65%) | |||

| ΔEorb | –85.54 (27.46%) | |||

| C2H5 | ΔEdisper | –12.13 (3.89%) | ||

| ΔEorb,σ | –57.01 | |||

| ΔEorb,π | –13.43 | |||

| ΔEorb,rest | –12.95 |

All energy values are at kcal mol–1.

Table 5. EDAa Analysis (BP86-D3/TZ2P(ZORA)//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP) of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MP(R)3] Complexes [M = Ag(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-Diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph].

| R | [Tgt → AgNHC(R)(H)] | [Tgt → AgP(R)3] | [Tgt → AgNHC(R)(Ph)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | ΔEint | –146.81 | –155.84 | –137.44 |

| ΔEpauli | 105.98 | 104.16 | 107.08 | |

| ΔEelast | –183.64 (72.7%) | –190.25 (73.18%) | –177.10 (72.43%) | |

| ΔEorb | –61.23 (24.3%) | –63.58 (24.45%) | –59.85 (24.48%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –7.92 (3.20%) | –6.16 (2.37%) | –7.56 (3.09%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –30.02 | –39.83 | –32.68 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –13.81 | –11.90 | –18.11 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –10.98 | –10.44 | –9.51 | |

| F | ΔEint | –150.28 | –173.46 | –140.64 |

| ΔEpauli | 104.33 | 107.93 | 107.88 | |

| ΔEelast | –187.23 (73.60%) | –202.06 (71.80%) | –179.26 (72.13%) | |

| ΔEorb | –59.54 (23.40%) | –72.43 (25.80%) | –61.78 (24.86%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –7.85 (3.10%) | –6.90 (2.50%) | –7.48 (3.01%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –31.72 | –43.14 | –33.23 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –18.83 | –18.30 | –19.55 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –9.25 | –10.53 | –9.46 | |

| Cl | ΔEint | –149.75 | –164.73 | –138.57 |

| ΔEpauli | 108.57 | 107.38 | 108.93 | |

| ΔEelast | –187.38 (72.60%) | –193.28 (71.10%) | –177.63 (71.77%) | |

| ΔEorb | –60.93 (23.60) | –71.61 (26.40%) | –60.92 (24.61%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –10.01 (3.90) | –7.22 (2.70%) | –8.95 (3.62%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –30.93 | –43.11 | –32.42 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –19.78 | –17.34 | –18.94 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –9.85 | –10.39 | –9.84 | |

| Br | ΔEint | –152.21 | –159.05 | –141.53 |

| ΔEpauli | 114.77 | 114.47 | 112.71 | |

| ΔEelast | –190.74 (71.50%) | –190.18 (69.60%) | –179.42 (70.57%) | |

| ΔEorb | –65.07 (24.40%) | –71.65 (26.20%) | –63.82 (25.10%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –11.17 (4.20%) | –11.69 (4.30%) | –10.99 (4.32%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –30.23 | –42.69 | –30.80 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –19.30 | –13.62 | –15.54 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –11.82 | –11.12 | –12.06 | |

| CH3 | ΔEint | –144.19 | –141.39 | –140.58 |

| ΔEpauli | 106.73 | 111.76 | 114.52 | |

| ΔEelast | –183.32 (73.10%) | –181.75 (71.80%) | –179.87 (70.51%) | |

| ΔEorb | –57.40 (22.90%) | –61.25 (24.20%) | –60.91 (23.88%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –10.20 (4.10%) | –10.15 (4.00%) | –14.32 (5.61%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –30.11 | –37.25 | –31.88 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –16.72 | –10.54 | –11.26 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –10.26 | –13.48 | –12.07 | |

| SiH3 | ΔEint | –146.24 | –142.86 | –137.40- |

| ΔEpauli | 108.28 | 110.40 | 111.03 | |

| ΔEelast | –185.12 (72.80%) | –180.77 (71.40%) | –176.04 (70.86%) | |

| ΔEorb | –59.13 (23.30%) | –61.25 (24.90%) | –61.07(24.58%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –10.27 (4.10%) | –9.49 (3.80%) | 11.32- (4.56%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –30.67 | –38.79 | –32.18 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –15.73 | –10.76 | –11.60 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –12.11 | –11.80 | –11.24 | |

| 2,6-diisopropyl phenyl | ΔEint | –137.94 | –127.74 | –137.33 |

| ΔEpauli | 115.84 | 115.99 | 118.18 | |

| ΔEelast | –176.57 (69.60%) | –163.91 (67.25%) | –174.91 (68.46%) | |

| ΔEorb | –59.98 (23.70%) | –60.66 (24.89%) | –60.45 (23.66%) | |

| ΔEdisper | –17.24 (6.80%) | –19.16 (7.86%) | –20.15 (7.89%) | |

| ΔEorb,σ | –30.72 | –35.75 | –30.32 | |

| ΔEorb,π | –14.60 | –9.86 | –11.58 | |

| ΔEorb,rest | –12.72 | –14.86 | –13.15 | |

| ΔEint | –138.91 | |||

| ΔEpauli | 111.77 | |||

| ΔEelast | –178.90 (71.37%) | |||

| C2H5 | ΔEorb | –60.78 (24.25%) | ||

| ΔEdisper | –10.99 (4.38%) | |||

| ΔEorb,σ | –36.64 | |||

| ΔEorb,π | –10.32 | |||

| ΔEorb,rest | –13.69 |

All energy values are at kcal mol–1.

Tables 4–6 represent the results of energy decomposition analysis (EDA) for [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes.

According to the EDA results for [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes with R′ = H and Ph (as these substituents are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle) complexes, it can be inferred that changing the R group from H to Ph has a relatively remarkable impact on the amount of interaction energy and also, in the plurality of cases for the same R substitution in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(Ph)] complexes, the amount of interaction energy is less than the corresponding value in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(H)] complexes (see Tables 4–6).

The results illustrate that the smallest values of ΔEint in the complexes correspond to electron-donating substitutions (often 2, 6-diisopropylphenyl) and the greatest values correspond to the electron-withdrawing changes (mostly F) (see Tables 4–6).

In addition, in accordance with what has been addressed in Section 3.2 in the presence of the electron-withdrawing substituents F, Cl, and Br and by considering the same M atom and changing the L ligand from NHC(R)(R′) to PR3, the strength of the M ← S bond in [Tgt → ML] complexes has increased. For example, as can be seen in Table 4, in the case of [Tgt → CuL] complex, the ΔEint values in the presence of NHC(F)(H/Ph) ligands are approximately 162.6 and 155.6 kcal mol–1 and by changing the L ligand group to PF3, the ΔEint value is approximately 186.7 kcal mol–1 (see Table 4). Therefore, the findings obtained suggested once again that drug releases are more facilitated in the presence of NHC(R)(R′) ligands than the PR3 ligands studied here.

The EDA analysis results reveal that among the three attractive terms of energy decomposition analysis, the electrostatic energy ΔEelstat is the most critical energy with about 64–74%. Subsequently, ΔEorb comes with a percentage in the range ∼22–30% and ΔEdisp, which arises from the instantaneous dipole–induced dipole forces between the two fragments having a little effect (about 2–9%) on ΔEint (see Tables 4–6).

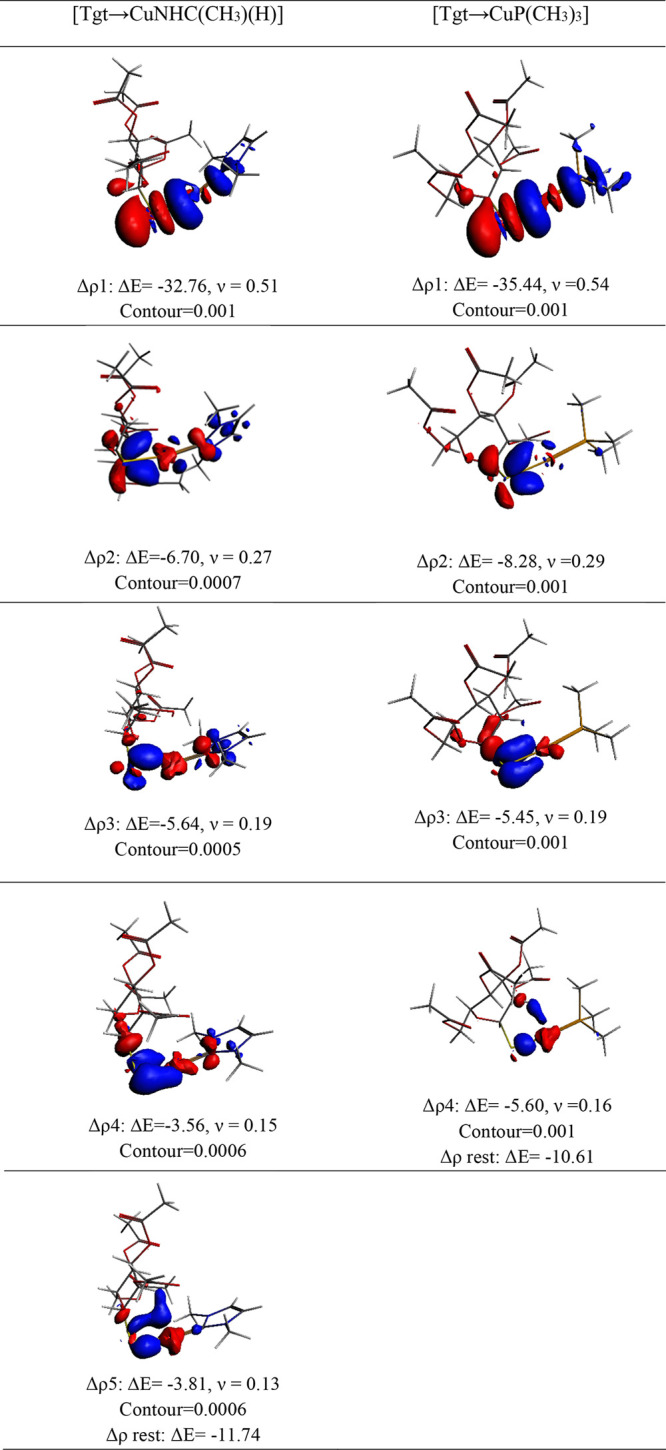

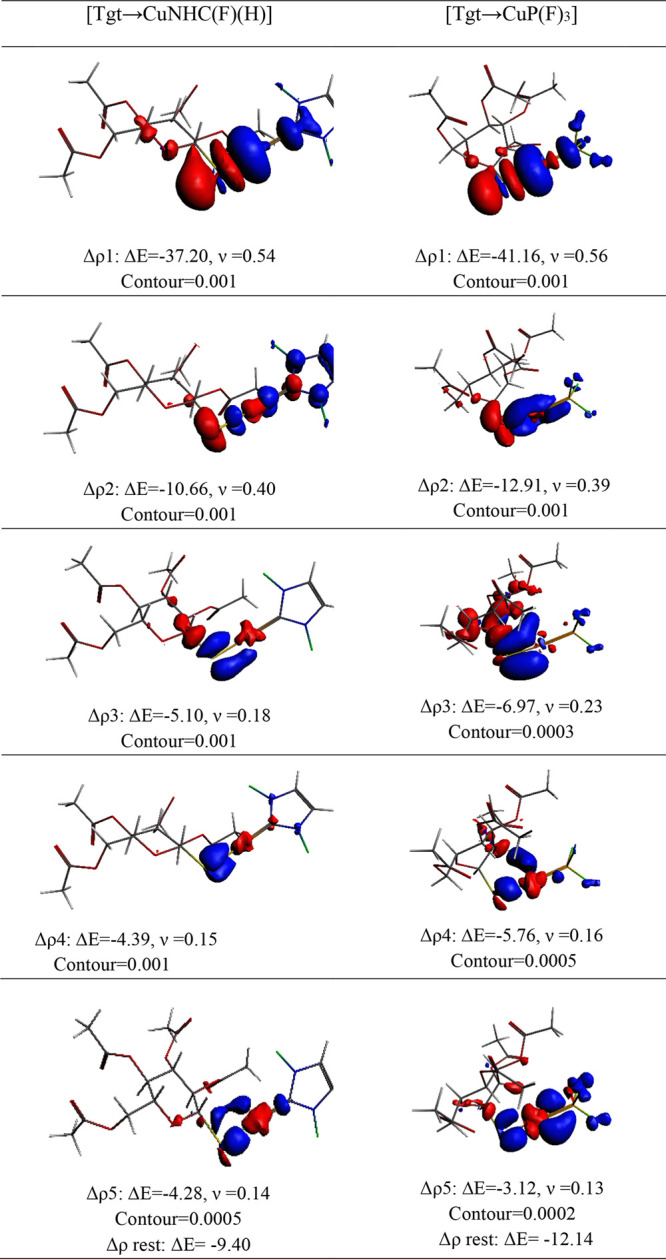

The covalent bond between the two interacted fragments of [MNHC(R)(R′)]+ with [Tgt]− and also [MPR3]+ with [Tgt]− fragments in the optimized structure of the [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] {M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I); R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph [as these substituents are given on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle]} complexes is rendered apparent by the measured deformation densities Δρ. This function can be associated with significant orbital interactions between the fragments described above.

Using the EDA–NOCV method, the individual portions of the pairwise interactions are determinable. It should be remembered that there are only a few numbers of pairwise encounters that make a major contribution to ΔEorb.

Regarding [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes, the NOCV pairs account for an average of 69.3–90.8% and 75.2–87.3% of ΔEorb, respectively. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the critical deformation densities and the associated energy values for [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] and [Tgt → CuPR3] (R = F and CH3) complexes. The Supporting Information gives the deformation densities for the other complexes (see Figures S1–S22). As seen in the figures as mentioned above, the dominant term of ΔEorb for [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] and [Tgt → CuPR3] complexes emerges from the σ-orbital interactions.

Figure 6.

Deformation densities associated with the most important orbital interactions for [Tgt → CuNHC(CH3)(H)] and [Tgt → CuP(CH3)3] complexes at the BP86-D3/TZ2P(ZORA)//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.

Figure 7.

Deformation densities associated with the most important orbital interactions for [Tgt → CuNHC(F)(H)] and [Tgt → CuP(F)3] complexes at the BP86-D3/TZ2P(ZORA)//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP level of theory.

According to Figures 6 and 7, in all complexes investigated here, the shapes of the orbital pair Δρ1 show the sigma orbital interaction between the lone pair of S atom of [Tgt]− fragment as the donor and the empty orbital of M atom in MNHC(R)(R′) and MPR3 fragments as the acceptor (see Figures 6 and 7).

On the other hand, the shapes of Δρ4 indicate the σ-back-donation (σbd) from the dz2 orbital at M atom to the [Tgt]− fragment in [Tgt → CuPR3] (R = F, and CH3) complexes. According to obtained results, the σ-orbital interactions which account for [Tgt → CuPR3] and [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] (R = F and CH3) complexes are approximately 50.5%–53.1% and 57.6%–58.9% of the ΔEorb term (see Figures 6 and 7). Likewise, in these complexes, the π and π-back-donation constitute approximately 19.7–27.6% of ΔEorb term. In this regard, Δρ2, Δρ3, and Δρ5 are attributed to the associated energy stabilization for the two π and π-back-donations, where Δρ2 is out of plan and Δρ3 and Δρ5 are in plan (see Tables 4–6 and Figures 6 and 7). It should be said that the shapes of Δρ2−Δρ5 in [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)](R = F, and CH3) complexes which indicate the π-back-donation constitute approximately 30.4–34.9% of ΔEorb term in [Tgt → CuNHC(R)(H)] (R = F, and CH3) complexes and they show that the Δρ2 and Δρ4 are out of plan and Δρ3 and Δρ5 are in plan (see Tables 4–6 and Figures 6 and 7). The obtained results confirm that in comparison to [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes, the interactions between the S atom of [Tgt]− fragment and M atoms of MPR3 fragments in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes can be regarded as better σ donors. Moreover, they can also be considered as weaker π acceptors than the corresponding values in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes.

4. Conclusions

The present study outlines a theoretical analysis on the complexes of the group 11 metals with general formula [Tgt → ML] in coordination with symmetrical unsaturated N-heterocyclic carbenes [NHC(R)(R′)] and monodentate phosphine (PR3) [where M = Cu(I), Ag(I), Au(I), Tgt = 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranoside, L = NHC(R)(R′) and PR3; R = F, Cl, Br, H, CH3, C2H5, SiH3, 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; R′ = H and Ph] at PBE-D3/def2-TZVP. The R′ substitutes are located on two noncarbenic carbon atoms (C4 and C5) in the heterocycle complexes. Data obtained from rms statistical results among eight density functional methods have shown that PBE-D3 is the most appropriate function among these methods.

The ΔEint values of the metal–drug (M ← S) bond in [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] and [Tgt → MPR3] complexes confirmed that the drug releases are more facilitated in the presence of NHC(R)(Ph) ligand than PR3 ligands studied here. In addition, it can be inferred that the group 11 metals form stronger bonds with the [Tgt]− drug in the [Tgt → MPR3] form than [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes in the presence of the same M metal ion and R = F, Cl, Br, and H substituents, The WBIs which were in good agreement with ΔEint of metal–drug (M ← S) bond confirmed that the drug releases were more facilitated in the presence of most of the NHC(R)(R′) ligands and Ag metal center than PR3 ligands and Cu and Au metal centers in the complexes.

The results of EDA, which were in agreement with NBO and ΔEint of metal–drug (M ← S) bond, not only confirmed that the drug releases were more facilitated in the presence of NHC(R)(R′) ligands than PR3 ligands for electron-withdrawing substituents but also confirmed that the electrostatic energy ΔEelstat was the most important energy among the three attractive terms of an energy decomposition analysis with about 64–74% in all the complexes. The EDA–NOCV confirmed that the interactions between the S atoms of the [Tgt]− fragment and M atoms of M-PR3 fragments in [Tgt → MPR3] complexes are better σ donors. Furthermore, they can be regarded as weaker π acceptors than the corresponding values in those of [Tgt → MNHC(R)(R′)] complexes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Bu-Ali Sina University Research Councils for the financial support of this work.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01471.

Cartesian coordinates, calculated M–C and M–S bond lengths, topological properties critical points of M–C and M-S bonds, and uncorrected ΔEint investigated here (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hahn F. E.; Jahnke M. C. Heterocyclic carbenes: Synthesis and coordination chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47, 3122–3172. 10.1002/anie.200703883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz W.; Frenking G.. Carbodiphosphoranes and Related Ligands. In Transition Metal Complexes of Neutral η1 -Carbon Ligands; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 2010; Vol. 30, pp 49–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. F.; Sun M. J.; Cao Z. X. Theoretical study on interactions of N-heterocyclic carbene with the bare first-row transition metals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2016, 135, 163–174. 10.1007/s00214-016-1922-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Heinemann C.; Müller T.; Apeloig Y.; Schwarz H. On the Question of Stability, Conjugation, and “Aromaticity” in imidazole-2-ylidenes and their Silicon analogs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 2023–2038. 10.1021/ja9523294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Boehme C.; Frenking G. Electronic structure of stable carbenes, silylenes, and germylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 2039–2046. 10.1021/ja9527075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Hillier A. C.; Sommer W. J.; Yong B. S.; Petersen J. L.; Cavallo L.; Nolan S. P. A Combined experimental and theoretical study examining the binding of N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) to the Cp*RuCl (Cp* = η5-C5Me5) moiety: Insight into stereoelectronic differences between unsaturated and saturated NHC ligands. Organometallics 2003, 22, 4322–4326. 10.1021/om034016k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Dröge T.; Glorius F. The measure of all rings-N–Heterocyclic carbenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6940–6952. 10.1002/anie.201001865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petz W.; Neumüller B.; Klein S.; Frenking G. Syntheses and crystal structures of [Hg{C(PPh3)2}2][Hg2I6] and [Cu{C(PPh3)2}2]I and comparative theoretical study of carbene complexes [M(NHC)2] with carbone complexes [M{C(PH3)2}2] (M = Cu+, Ag+, Au+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Hg2+). Organometallics 2011, 30, 3330–3339. 10.1021/om200145c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Öfele K. 1,3-Dimethyl-4-imidazolinyliden-(2)-pentacarbonylchrom ein neuer übergangsmetall-carben-komplex. J. Organomet. Chem. 1968, 12, P42–P43. 10.1016/s0022-328x(00)88691-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanzlick H.-W.; Schönherr H.-J. Direct synthesis of a Mercury salt-carbene complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1968, 7, 141–142. 10.1002/anie.196801412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo A. J. III; Harlow R. L.; Kline M. A stable crystalline carbene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 361–363. 10.1021/ja00001a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hindi K. M.; Panzner M. J.; Tessier C. A.; Cannon C. L.; Youngs W. J. The medicinal applications of imidazolium carbene-metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3859–3884. 10.1021/cr800500u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Gust R. Update on metal N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as potential anti-tumor metallodrugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 329, 191–213. 10.1016/j.ccr.2016.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oehninger L.; Rubbiani R.; Ott I. N-Heterocyclic carbene metal complexes in medicinal chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 3269–3284. 10.1039/c2dt32617e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C.; Li X.; Wang W.; Zhang R.; Deng L. Metal-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as anti-tumor agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1220–1230. 10.2174/0929867321666131217161849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisnetti F.; Gibard C.; Gautier A. Post-functionalization of metal-NHC complexes: A useful toolbox for bio-organometallic chemistry (and beyond)?. J. Organomet. Chem. 2015, 782, 22–30. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2014.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aher S. B.; Muskawar P. N.; Thenmozhi K.; Bhagat P. R. Recent developments of metal N-heterocyclic carbenes as anticancer agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 81, 408–419. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Gust R. Metal N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as potential antitumor metallodrugs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 755–773. 10.1039/c2cs35314h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisnetti F.; Gautier A. Metal/N–Heterocyclic carbene complexes: opportunities for the development of anticancer metallodrugs. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 11976–11978. 10.1002/anie.201306682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budagumpi S.; Haque R. A.; Endud S.; Rehman G. U.; Salman A. W. Biologically relevant silver(I)–N–Heterocyclic carbene complexes: synthesis, structure, intramolecular interactions, and applications. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2013, 4367–4388. 10.1002/ejic.201300483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S. A.; Patil S. A.; Patil R.; Keri R. S.; Budagumpi S.; Balakrishna G. R.; Tacke M. N-heterocyclic carbene metal complexes as bio-organometallic antimicrobial and anticancer drugs. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 1305–1333. 10.4155/fmc.15.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmert C.; Gornitzka H. Luminescent bioactive NHC–metal complexes to bring light into cells. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 440–447. 10.1039/c5dt03904e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Zhou L. A theoretical study on the anticancer drug Au(I) N-heterocyclic carbine complexes [(R2Im)2Au]+ (R = Me, Et, i-Pr, and n-Pr) binding to cysteine and selenocysteine residues. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2016, 135, 1–12. 10.1007/s00214-015-1776-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alex J.; Ghosh P. Fascinating frontiers of N/O-functionalized N-heterocyclic carbene chemistry: from chemical catalysis to biomedical application. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 7183–7206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier A.; Cisnetti F. Advances in metal–carbene complexes as potent anti-cancer agents. Metallomics 2012, 4, 23–32. 10.1039/c1mt00123j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Sadler P. J. Advances in the design of organometallic anticancer complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 839, 5–14. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2017.03.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey J. L.; Ruhayel R. A.; Barnard P. J.; Baker M. V.; Berners-Price S. J.; Filipovska A. Mitochondria-Targeted Chemotherapeutics: The rational design of Gold(I) N-Heterocyclic carbene complexes that are selectively toxic to cancer cells and target protein selenols in the preference to thiol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12570–12571. 10.1021/ja804027j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedlock L. E.; Berners-Price S. J. Recent advances in mapping the sub-cellular distribution of metal-based anticancer drugs. Aust. J. Chem. 2011, 64, 692–704. 10.1071/ch11132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer H. A.; Kaska W. C. Stereochemical control of transition metal complexes by polyphosphine ligands. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 1239–1272. 10.1021/cr00029a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann M.; Frenking G. Carbones as Ligands in Novel Main–Group Compounds E[C(NHC)2]2 (E=Be, B+, C2+, N3+, Mg, Al+, Si2+, P3+): A Theoretical Study. Chem.—Eur. J. 2017, 23, 3347–3356. 10.1002/chem.201604801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Fremont P.; Stevens E. D.; Eelman M. D.; Fogg D. E.; Nolan S. P. Synthesis and characterization of Gold(I) N-Heterocyclic carbene complexes bearing biologically compatible moieties. Organometallics 2006, 25, 5824–5828. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2010.

- Bader R. F. W.Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. A.; Reed A. E.; Carpenter J. E.; Weinhold F.. NBO, version 3.1; Gaussian Inc.: Pittsburgh, 2003.

- Bayat M.; Soltani E. Stabilization of group 14 tetrylene compounds by N-heterocyclic carbene: A theoretical study. Polyhedron 2017, 123, 39–46. 10.1016/j.poly.2016.10.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nemcsok D.; Wichmann K.; Frenking G. The Significance of π Interactions in Group 11 complexes with N-Heterocyclic carbenes. Organometallics 2004, 23, 3640–3646. 10.1021/om049802j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat M.; Sedghi A.; Ebrahimkhani L.; Sabounchei SJ N-Heterocyclic carbene or phosphorus ylide: which one forms a stronger bond with group 11 metals? A theoretical study. Dalton Trans. 2016, 46, 207–220. 10.1039/c6dt03814j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popelier P. L. A.Atoms in Molecules: An Introduction; Pearson Education, Prentice Hall: Harlow, England, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K. Recognition of stereochemical paths by orbital interaction. Acc. Chem. Res. 1971, 4, 57–64. 10.1021/ar50038a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boys S. F.; Bernardi F. The calculation of small molecular interactions by the differences of separate total energies. Some procedures with reduced errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. 10.1080/00268977000101561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morokuma K. Molecular orbital studies of hydrogen bonds. III. C=O···H–O Hydrogen bond in H2CO···H2O and H2CO···2H2O. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 55, 1236–1244. 10.1063/1.1676210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler T.; Rauk A. Carbon monoxide, carbon monosulfide, molecular nitrogen, phosphorus trifluoride, and methyl isocyanide as σ donors and π acceptors. A theoretical study by the Hartree-Fock-Slater transition-statemethod. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 1755–1759. 10.1021/ic50197a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler T.; Rauk A. A theoretical study of the ethylene-metal bond in complexes between copper(1+), silver(1+), gold(1+), platinum(0) or platinum(2+) and ethylene, based on the Hartree-Fock-Slater transition-state method. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 1558–1565. 10.1021/ic50196a034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoraj M.; Michalak A. Donor–Acceptor properties of ligands from the natural orbitals for chemical valence. Organometallics 2007, 26, 6576–6580. 10.1021/om700754n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitoraj M.; Michalak A. Applications of natural orbitals for chemical valence in a description of bonding in conjugated molecules. J. Mol. Model. 2008, 14, 681–687. 10.1007/s00894-008-0276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenking G.; Shaik S.. The Chemical Bond: Fundamental Aspects of Chemical Bonding; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bickelhaupt F. M.; Baerends E. J. Kohn-Sham density functional theory: Predicting and understanding chemistry. Rev. Comput. Chem. 2000, 15, 1–86. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.