Abstract

Introduction

Involvement of the large vessels is rarely reported and poorly understood in cases of Corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19). The aim of this study is to present a series of cases with large vessel thrombosis (LVT).

Methods

This is a multicenter prospective case series study. The participants were consecutive in order. All the patients were diagnosed as cases of COVID-19 with documented LVT were included in the study. Large vessels were defined as any vessel equal or larger than popliteal artery. The mean duration of follow up was 4 months.

Results

The study included 22 cases, 19 (86.4%) cases were male, 3 (13.6%) patients were females. The age ranged from 23 to 76 with a mean of 48.4 years. Four (18.2%) cases had pulmonary embolism confirmed by IV contrast enhanced chest CT scan. All of the cases showed pulmonary parenchymal ground glass opacities (GGO) and high D-Dimers (ranging from 1267 to 6038 ng/ml with a mean of 3601 ng/ml).

Conclusion

COVID-19 is a hidden risk factor of LVT that may endanger the patient's life and lead to major amputation. Despite therapeutic anticoagulants still all COVID-19 patients are at risk for LVT, a high index of suspicion should be created and with minimal symptoms surgical consultation should be obtained.

Keywords: Ischemia, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Thrombosis

Highlights

-

•

Involvement of the large vessels is rarely reported in COVID-19.

-

•

It may endanger both limb and life of the patients.

-

•

In the current report, vessel thrombosis discussed in 9 COVID-19 patients.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is an emerging and novel pathogen which is easy to spread with variable duration of asymptomatic period causing major quarantines including enormous cities, towns, villages and public quarters all around the world. Although it is primarily reported as an infection of the respiratory system, pooled data revealed that it is a systemic illness that involves several body parts, including neurological, hematopoietic, gastrointestinal, immune, and cardiovascular systems [1,2]. This wide range of presentations might be explained by the extensive and rich presence of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in various organs [3,4].

Involvement of the large vessels is rarely reported and poorly understood. The aim of this study to present a series of cases with LVT due to COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Registration

The study was registered in light of declaration of Helsinki – “Every research study involving human subjects must be registered in a publicly accessible database before recruitment of the first subject”. The research was recorded in Chinese Clinical Trial Registry. The registration number is ChiCTR2000038537, the link is http://www.chictr.org.cn/showprojen.aspx?proj=60821&fbclid=IwAR3WPzY9Y91ggJZn1H-O9Avq-7HmQs-IOhChG-B4F2jTtAeH0CdbRVL2zX8.

2.2. Study design

This is a multi center prospective case series study. The participants were consecutive in order. The paper has been written in line with the PROCESS criteria [8].

2.3. Setting

The cases were managed in the governmental and private settings. The research was carried out during 7 months (from January 1, 2020 to 1/8/2020. The data were collected from the patients, patient's family and the hospital records. The cases were followed up for a mean duration of 4 months ranging from 2 months to 8 months. Ethical and scientific approval has been taken from the ethical committee of university of Sulaimani.

Participants: All Patients diagnosed as cases of COVID-19 either by nasopharyngeal swab or chest CT scan with documented LVT were included in the study. Large vessel was defined as any vessel equal or larger than popliteal artery. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Any patient without documented COVID-19. (2) COVID patients without LVT. (3) Patient with less than 2 month follow up. A written, informed consent was taken from all of the patients.

Work up and Management: The COVID patients were managed according to the local protocol which was derived from WHO recommendations. After detailed history and careful clinical assessment, they were sent for nasopharyngeal swab, chest CT scan, hematological tests including arterial blood gas analysis. Vessel thrombosis was managed per case. The patients were given oxygen, multivitamins, azithromycin, chloroquine and steroid. The primary end point was ischemia outcome, the secondary end point was effectiveness of surgical intervention.

Statistical analysis: the data collection was performed using an excel sheet, they were transferred to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 22 after coding. Due to the small sample size, only descriptive analysis was calculated.

3. Results

The study included 22 cases, 19 (86.4%) cases were male, 3 (13.6%) patients were females. The age ranged from 23 to 76 with a mean of 48.4 years. Four (18.2%) cases had pulmonary embolism confirmed by IV contrast enhanced chest CT scan, (Fig. 1, Table 1). All of the cases showed pulmonary parenchymal ground glass opacities (GGO) and high D-Dimers (ranging from 1267 to 6038 ng/ml with a mean of 3601 ng/ml). Twelve (54%) patients gained full recovery without thrombosis sequelae, while 3 (13.6%) patients died from pneumonia. One patient (49 year-old male) presented with a severe bilateral lower limb pain for 2 hours followed by total loss of right lower limb motor and sensory function with grade III weakness of the left lower limb and loss of sensation until the level of the popliteal region. The coldness reached the level of the umbilicus. Chest and abdominal CT scan showed thrombosis of abdominal aorta extending to the both common femoral arteries with multiple bilateral GGOs diffusely involving lung parenchyma, typical of viral infection (Fig. 2). Under local anesthesia, in supine position, bilateral femoral artery thromboembolectomy was performed. Twenty cm on the right and 10 cm on the left red fresh thrombi were removed. Two hours after the intervention, the condition started to improve, and the patient gained full function 24 hours after the intervention. Two other patients (55 year-old male, 68 year old female) presented with acute abdomen, intraoperative findings showed total occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery with bowel ischemia, they underwent bowel resection with revascularization using greater saphenous vein (superior mesenteric-aorta and superior mesenteric-external iliac artery bypass).

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan (axial view) with IV contrast showing bilateral pulmonary embolism.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cases.

| Case # | Age (years)/sex | Presentation | Thrombosed vessels | COVID-19 pneumonia | Past History | Management | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 49/male | Signs and symptoms of bilateral lower limb ischemia | Lower abdominal aorta, common iliac, external iliac and common femoral arteries | Positive | Hypertension, Ischemic heart disease | Bilateral femoral artery embolectomy followed by Enoxaparin (6000 IU*2) and Aspirin (100 mg*1) | Full recovery |

| 2nd | 62/male | Dyspnea, fever followed by bilateral lower limb ischemia | Left common femoral and right popliteal arteries | Positive | Hypertention, diabetes mellitus | Enoxaparin (6000 IU*2) followed by aspirin (100*1) | Left above knee and right below knee amputation |

| 3rd | 65/female | fever, rigor, generalized body ache, cough followed by left lower limb ischemia | Left popliteal and anterior tibial artery thrombosis | Positive | Negative | Enoxaparin (6000 IU*2) followed by aspirin (100*1) | Full recovery |

| 4th | 66/male | Fever, rigor, generalized body ache, dyspnea | Left popliteal, anterior tibial, posterior tibial artery thrombosis | Positive | Hypertention, diabetes mellitus, Ischemic heart disease | Popliteal artery embolectomy, anticoagulation, antiplatelet. | Death |

| 5th | 49/male | Signs and symptoms of left upper limb ischemia | Axillobrachial thrombosis | Positive | Negative | Enoxaparin (6000 IU*2) followed by aspirin (100*1) | Full recovery |

| 6th | 61/male | Dyspnea, confusion | Left femoral artery thrombosis | Positive | Hypertension | Left femoral artery embolectomy followed by Enoxaparin (6000 IU*2) and Aspirin (100 mg*1) | Death |

| 7th | 83 years/Male | Dyspnea and cough, followed by Rt lower limb ischemia 10 days | Right common iliac, external iliac, common femoral, popliteal and pedal Arteries | Negative | Diabetes mellitus, ex smoker | Rt lower limb thrombo-embolectomy | Forefoot Amputation |

| 8th | 52 years/male | Cough and dyspnea, recovered then Left lower limb ischemia | Left femoro-popletial arteries | Negative | Nill | Lt lower limb Thrombo-embolectomy | Full recovery |

| 9th | 70 years/male | Cough and fever and SOB, 12 days Lt lower limb ischemia | Left External iliac, common femoral, superficial femoral, and popliteal arteries | Positive | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease | Conservative with Heparin unfractionated 5000*4 5 doses of illioprost infusion |

Full recovery |

| 10th | 62 years/male | Dyspnea cough anosmia, 10 days of left lower limb ischemia | Left femoral and popliteal arteries | Negative | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease | Lt lower limb thrombo-embolectomy | Full recovery |

| 11th | 43years/male | Dyspnea and cough Left lower limb ischemia |

Left femoropopletial Arteries |

Negative | Nill | Left lower limb embolectomy | Full recovery |

| 12th | 65 years/male | Recovered from COVID With bluish discoloration of Lt big toe |

Left femoro-popletial arteries | Positive | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease | Left lower limb embolectomy | Big toe amputation |

| 13th | 70 years/male | Dyspnea, Fever and cough Left lower limb ischemia 10 days |

Left femoropopletial arteries | Positive | Hypertension, ischemic heart disease | Left lower limb embolectomy | Above knee amputation |

| 14th | 76 years/Male | Dyspnea cough fever and bilateral lower limb ischemia On cpap |

Left common iliac, common femoral and popletial arteries | Positive | Chronic heavy smoker and Hypertension | Conservative on BMT Enoxaparin 6000 *2 |

Below knee amputation |

| 15th | 70 years/male | Dyspnea and cough Left lower limb ischemia |

Left common iliac, common femoral and popletial arteries | Positive | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension | Conservative on BMT Enoxaparin 6000*2 |

Below knee amputation |

| 16th | 68 Female | Acute abdomen | Superior mesenteric artery with signs of bowel ischemia | Positive | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease | Superior mesenteric artery Embolectomy with External iliac to Superior mesenteric artery greater saphenous vein bypass And 1 m bowel resection |

Full recovery |

| 17th | 55Male | Acute abdomen | Superior mesenteric artery | Positive | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, | Superior mesenteric artery Embolectomy with aortic to superior mesentric artery greater saphenous vein bypass And 1.5 m bowel resection |

Death |

| 18th | 43years/male | Dyspnea and cough Left lower limb ischemia |

Femoropopletial Arteries |

Negative | Nill | Left lower limb embolectomy | Full Recovery |

| 19th | 23/female | Dyspnea, chest pain, fever, anosmia, ageusia and sweating | Bilateral pulmonary artery thrombosis | Positive | Negative | Enoxaparin (6000 IU*2) followed by aspirin (100*1) | Full recovery |

| 20th | 31/male | Dyspnea, hemoptysis and flu-like illness | Bilateral pulmonary artery thrombosis with multiple areas of pulmonary infarction | Negative | Negative | Alteplase 50 mg *2 followed by rivaroxaban 20 mg *1 | Full recovery |

| 21st | 56/male | Cough, dyspnea, chest pain, hypotension and hemoptysis | Bilateral pulmonary artery thrombosis | Positive | Hypertension | Alteplase 50 mg *2 followed by rivaroxaban 20 mg *1 | Full recovery |

| 22nd | 35/male | Fever, cough and dyspnea | Right main pulmonary artery thrombosis | Positive | Negative | Alteplase 100 mg Followed by rivaroxaban 20 mg *1 |

Full recovery |

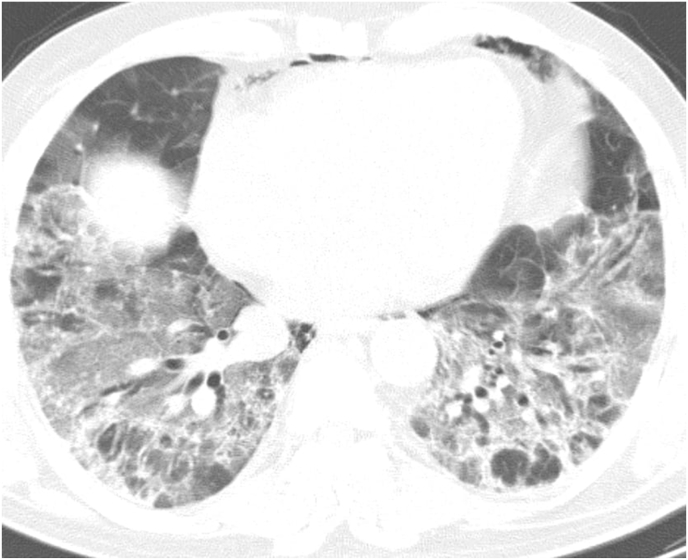

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scan (axial view) showing diffuse bilateral patches of ground glass opacities.

4. Discussion

Although thromboembolic complications associated with COVID-19 have rarely been defined in details in the literature. It is known that the incidence of both venous and arterial thromboembolism increases in COVID-19 patients [5]. One of the most constant biochemical changes is D-dimer elevation which, to some extent certainly mirrors intra-vascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 [6]. All of the current cases showed elevated D-dimer.

The association between hypercoagulability and COVID-19 infection has been just highlighted in few studies. Tang et al. revealed that abnormal coagulation findings, described as an evidently raised D-dimer level and fibrin degradation products (FDP), are prevalent in died cases of COVID19-related pneumonia [7]. Han and associates found that the coagulation process is considerably disturbed compared with uninfected control group and that observing coagulation parameters could lead to early recognition of the severe cases [9]. Intravascular thrombosis in COVID-19 is probably due to hypoxia, increased production of tissue factor, amplification of the coagulation cascade, diffuse intravascular coagulation (DIC), excessive inflammation and immobilization [5].

The high prevalence of pulmonary embolism could be explained by two processes in addition to the mentioned factors: first, changed blood flow in response to the parenchymal process in hypoxia, and second, transition from deep venous thrombosis to pulmonary embolism, which, in fact, is the minority of the cases [10].

Presentation of COVID-19 patients with acute limb ischemia without respiratory symptoms is rarely highlighted in the literature. Mietto and colleagues reported a 53-year-old male who presented with signs and symptoms of left lower limb ischemia associated with inability of walking. Scanning with duplex sonography revealed absence of flow in the femoral and popliteal arteries. CT angiography showed thrombosis extending to the iliac arteries. Native chest CT scan discovered diffuse bilateral pulmonary GGOs. The history was clear regarding respiratory symptoms, fever, or fatigue. The patient was managed by embolectomy, fasciotomy, thrombolytics and anticoagulation [11]. Fahad and associates published their experience with a 49-year-old woman who presented with left lower limb ischemia one day before appearance of classical COVID-19 symptoms. The ischemia was treated with anticoagulation [12]. The patient's condition deteriorated ending with sudden cardiac arrest and death. In the present series, one of the patients presented with bilateral lower limb ischemia without respiratory symptoms leading to diagnostic dilemma as the ischemia and coldness extending to the level of umbilicus. He was successfully managed with bilateral femoral thromboembolectomy under local anesthesia and anticoagulation.

The socio-demographic characteristics of the COVID-19 patients are not well defined. However, most of the patients with LVT are men. Bellosta and associates reported 20 cases of COVID-19 with LVT, 18 of them (90%) were male [13]. Escalard et al. published their experience with 10 COVID-19 patients, only two of them (20%) were female [14]. In the current study, one patient (10%) was woman. Higher rate of thromboembolism in male COVID-19 patients is not understood, further studies are mandatory.

According to the recommendations from American Society of Hematology, all admitted COVID-19 patients should have thromboprophylaxis with fondaparinux or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), and full therapeutic anticoagulation is required in patients with vessel thrombosis. LMWH seems to be linked with a better prognosis in severe COVID-19 patients with noticeably raised D-dimer levels [15].

In conclusion; COVID-19 is a hidden risk factor of LVT that may endanger the patient's life and lead to major amputation.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was given by Ethical and Scientific Committee of University of sulaimani. No. 45

Source of Funding

None to be declared.

Conflict of interest

None to be declared.

Research Registration Unique Identifying Number (UIN)

ChiCTR2000038537 from Chinese Clinical Trial Registry.

Author contribution

Aram Baram, Fahmi H. Kakamad, Hadi M. Abdullah, Dana H. Mohammed-Saeed Binar B. Abdulrahman, Aram J. Mirza: Surgeons and Physicians supervising the management, revising the manuscript. Final approval of the manuscript.

Dahat A. Hussein, Shvan H Mohammed Berwn A. Abdulla, Hawbash M. Rahim, Mohammed J. Rashid, Farhad F. Mohammed-Al, Abdulwahid M. Salih, Yad N. Othman: data collection, drafting the manuscript. Final approval of the manuscript.

Guarantor

Fahmi Hussein Kakamad

Data statement

The data that support the findings are available from the corresponding author, upon request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.11.030.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Terpos E., Ntanasis‐Stathopoulos I., Elalamy I., Kastritis E., Sergentanis T.N., Politou M. Hematological findings and complications of COVID‐19. Am. J. Hematol. 2020;95(7):834–847. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah H.M., Hama-Ali H.H., Ahmed S.N., Ali K.M., Karadakhy K.A., Mahmood S.O. Severe refractory COVID-19 patients responding to convalescent plasma; A case series. Annals of medicine and surgery. 2020;56:125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., Chuich T., Dreyfus I., Driggin E. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L., Cecconi M., Ferrazzi P., Sebastian T. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb. Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price L.C., McCabe C., Garfield B., Wort S.J. Thrombosis and COVID-19 pneumonia: the clot thickens! Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56(1):1–5. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01608-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonard-Lorant I., Delabranche X., Severac F., Helms J., Pauzet C., Collange O. Acute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients on CT angiography and relationship to D-dimer levels. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P. For the PROCESS group. The PROCESS 2018 statement: updating consensus preferred reporting of CasE series in Surgery (PROCESS) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han H., Yang L., Liu R., Liu F., Wu K.L., Li J. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020;58(7):1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J., Van der Meer N.J., Arbous M.S., Gommers D.A., Kant K.M. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mietto C., Salice V., Ferraris M., Zuccon G., Valdambrini F., Piazzalunga G. Acute lower limb ischemia as clinical presentation of COVID-19 infection. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahad A.M., Mohammad A.A., Al-Khalidi H.A., Lazim Q.J., Hussein F.I., Alshewered A.S. Case report: COVID-19 in a female patient who presented with acute lower limb ischemia. F1000Research. 2020;9(778):778. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellosta R., Luzzani L., Natalini G., Pegorer M.A., Attisani L., Cossu L.G. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escalard S., Maïer B., Redjem H., Delvoye F., Hébert S., Smajda S. Stroke; 2020. Treatment of acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion with COVID-19: experience from paris. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur P., Qaqa F., Ramahi A., Shamoon Y., Singhal M., Shamoon F. Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy. 2020. Acute upper limb ischemia in a patient with COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.