Abstract

The present study investigated the prevalence of CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2, using PCR–RFLP, in normal and oral cancer (OC) patients that were stratified by OC subtype and gender. The risk of cancer, 5-year cumulative survival and hazard’s ratio (HR) with respect to risk factors and clinical factors were estimated using Fisher’s exact test, Kaplan–Meier analysis, and Cox proportional hazards models. CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ lowered the risk of buccal mucosa cancer (BMC) in males (OR = 0.37), whereas, ‘G’ allele of CYP3A5*3 increased risk of tongue cancer (TC) (OR = 1.67). SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ increased the risk of TC (OR = 2.36) and BMC (OR = 3.25) in females. The 5-year survival of the patients depended on factors like age, lymphovascular spread (LVS), perinodal spread (PNS), recurrence, tobacco, and alcohol. CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ and ‘GG’ had decreased the hazard ratio (HR) for BMC females when inflammatory infiltrate alone or along with other covariates, LVS, PNI, PNS, metastasis, recurrence, and relapse was adjusted. Similarly, CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ decreased the risk of death (HR = 0.05) when the grade was adjusted. SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ had decreased HR for TC males (HR = 0.08) after adjusting for inflammatory infiltrate, LVS, perineural invasion (PNI), PNS, metastasis, recurrence, and relapse. Further, our bioinformatics study revealed the presence of a CpG island within the CYP2D6 and a CTCF binding site upstream of CYP2D6. Interestingly, three CpG islands and two CTCF binding sites were also identified near the SULT1A1. In conclusion, the SNPs altered risk and survival of BMC and TC differentially in a gender specified manner, that varied with clinical and risk factors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02526-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3, SULT1A1*2, Tongue cancer, Buccal mucosa cancer, 5-Year cumulative survival

Introduction

Cytochrome P450 enzymes, CYP3A4/5, and CYP2D6 play a predominant role in the metabolism of drugs. The CYP3A4/5 and CYP2D6 metabolize 50% (Depaz et al. 2013) and 25% (Gaedigk et al. 2016) of drugs, respectively, that are used both for common ailments and specific diseases like cancer (Zanger and Schwab 2013). Interestingly, these CYPs also activate pro-carcinogens to carcinogens present in tobacco which is a known risk factor for oral cancer (OC) (Johnson 2001). OC is leading cancer in Indian men and its related mortality. CYPs also metabolize anti-cancer drugs such as docetaxel, paclitaxel, and tamoxifen used for treating OC and drugs used in palliative care (Washio et al. 2011). Non-CYP enzyme, Sulfotransferase 1A1 (SULT1A1), a phase II drug-metabolizing enzyme, facilitates the elimination of tamoxifen and other drugs by adding sulfate moiety (Daniels and Kadlubar 2014). Additionally, SULT1A1 is involved in the metabolism/bio-activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and aromatic amines present in tobacco smoke (Hung et al. 2004).

Loss of enzyme activity of CYP2D6, CYP3A5, and SULT1A1, present in hepatic and non-hepatic tissues, occurs due to functional SNPs of the encoding genes (Zhou et al. 2009). The most prevalent variants are CYP2D6 (CYP2D6*4, rs3892097), CYP3A5 (CYP3A5*3, rs776746) and SULT1A1 (SULT1A1*2; rs9282861). CYP2D6*4 causes G > A transition at the first nucleotide of exon 4 which leads to complete loss of enzyme activity (Wegman et al. 2007). CYP3A5*3 causes A > G transition in intron 3 that causes lowered enzyme expression (Kuehl et al. 2001). SULT1A1*2 causes G > A transition in exon 7 that results in substitution of arginine to histidine at position 213 on the protein which decreases thermal stability and activity of the enzyme (Daniels and Kadlubar 2014). These SNPs not only affect the efficacy of various drugs (Ingelman-Sundberg 2005; Rendic 2002) but also alter susceptibility to cancers (Bhat et al. 2015; Lopes et al. 2015). As these enzymes can: impact the pharmacokinetics of drugs; convert pro-carcinogens to carcinogens; and were linked to cancer, understanding the prevalence of these SNPs may help in devising alternate strategies for the people with defective enzymes. Hence, we designed our study to investigate these SNPs in a less heterogeneous population (geographically matched normal and OC subjects). We stratified the data by gender and tumor site (buccal mucosa cancer; BMC and tongue cancer; TC) and analysed the frequencies of the SNPs, their association with OC risk, and 5-year cumulative survival and hazards ratio (HR) of the patients, with respect to clinical and risk factors.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present case–control study is approved by the institute’s ethics committee. The study includes a total of 1448 consenting subjects aged 18–85 years, which are drawn from a relatively less heterogeneous population of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh states of India. Among the study subjects, 909 were normals (505 males; 404 females) and 539 were patients. Among patients, 238 had BMC (124 males; 114 females) and 301 had TC (202 males; 99 females). CYP2D6*4 was genotyped in 910 subjects (353 patients; 557 normals), CYP3A5*3 was genotyped in 687 subjects (318 patients; 369 normals), SULT1A1*2 was genotyped in 609 subjects (248 patients; 361 normals). Patients were from our institute and normals were drawn from various outside sources. Normals were drawn randomly and were unrelated, apparently healthy, non-symptomatic, with no known family history of cancer, and to our knowledge, were not habitual tobacco chewers or smokers and alcohol drinkers. The patients, visiting our institute, were confirmed cases of TC and BMC. Cancer was detected and diagnosed by oncologists from our institute by visual inspection, symptoms, and biopsy. The cancer was also confirmed by histopathology of the excised tissue, following surgery. Stage and grade of the tumors were determined using the TNM staging system and by the differentiation state of the cells, respectively. The demographic and clinical data of the patients were obtained over the phone and medical records.

Detection of polymorphic variants

Genomic DNA was isolated by salting out a protocol with few modifications, as described earlier (Daripally et al. 2015). The samples were genotyped by PCR–RFLP, under optimal conditions, using reported primers (Arslan 2010; Nida et al. 2017; Tsuchiya et al. 2008). The size of the amplicons was determined by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE). The amplicons of CYP2D6*4 (354 bp), CYP3A5*3 (130 bp), and SULT1A1*2 (281 bp) were, treated with BstNI, SspI and HhaI, respectively and the products were identified by 3% AGE. Genotypes were validated by sequencing 10% of randomly chosen samples from each study group.

Statistical analysis

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was assessed for normals and cancer cases using an online tool (Rodriguez et al. 2009). Our data were stratified by gender and OC sub-types, BMC, and TC for further analysis. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed using GraphPad Instat3.1 and SPSS23.0, respectively. The differences between groups were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05. In an analysis, if the value has not reached due to lack of events, it is denoted as NR$ and if the value is null due to lack of samples, it is denoted as NR#.

Univariate analysis

Unpaired t-test for comparison of means was performed for age and BMI between normal and cancer subjects. Odds ratios (OR) at 95%CI and P value were calculated using two-tailed Fisher’s Exact Test. OR of 1 as a reference, > 1.0 and < 1.0, were considered as increased or decreased disease risk, respectively. For SNPs and their combinations, wild type genotype was the reference. Disease risk with the SNPs was estimated for users of alcohol and tobacco chewing, with their respective non-users as a reference group, among males and females with BMC and TC. 5-year cumulative survival of patients after diagnosis, in months, was calculated by Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival analysis. Comparisons were done for BMC vs TC, females vs males, and wild type vs mutants. The variables tested were age, gender, SNPs, tobacco chewing, smoking, tobacco use, alcohol use and tobacco plus alcohol use, clinical parameters such as stage, grade, inflammatory infiltrate, lymphovascular spread (LVS), perinodal spread (PNS), perineural invasion (PNI), metastasis, recurrence, and relapse. Patients were stratified into two age groups; ≤ 50 years and > 50 years. For the analyses, ≤ 50 years of age, ‘GG’ (CYP2D6*4), ‘AA’ (CYP3A5*3), ‘GG’ (SULT1A1*2), GG + GG (CYP2D6*4 and SULT1A1*2), AA + GG (CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2) genotypes, non-chewers, non-smokers, tobacco non-users, alcohol non-users, and tobacco plus alcohol non-users, stage I, grade 1, mild inflammatory infiltrate, absence of LVS, PNI, PNS, metastasis, recurrence, and relapse were taken as reference.

Multivariate analysis

Logistic regression analysis was done to assess the association of the SNPs with BMC and TC, stratified by gender after adjusting for age. ORs were computed by comparing the frequencies between normals and patients. Cox-proportional hazards models have generated alternatively for variables (covariates) that exhibited co-linearity (P < 0.05) to have the best fit for unbiased estimates of hazards ratio (HR). The models were tested by adjusting various combinations of variables. The outcome of each covariate on HR or risk of death, over a period of 5 years after diagnosis, was estimated by computing adjusted HR at 95%CI. HR value of 1 was taken as reference whereas HR < 1 and HR > 1 was considered as a lower and higher risk of death, respectively. The variables and references used were as mentioned in the univariate analysis.

Bioinformatics analysis

Using SNPnexus (Dayem Ullah et al. 2013), the functional consequences of CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2 were predicted. Human Splicing Finder, HSF 3.0, (Desmet et al. 2009) was used to predict the impact of variants on the splice sites (donor and acceptor), exonic splicing enhances (ESE), exonic splicing silencer (ESS), intronic splicing enhancer (ISE), intronic slicing silencer (ISS) and branch point sequence (BPS). ENCODE (Kent et al. 2002) was used for investigating the plausible presence of regulatory sites within and near CYP2D6, CYP3A5 & SULT1A1.

Results

Characteristics of patients

TC and BMC cases showed significantly higher average age than their respective normals. The average BMI of TC (P = 0.0001) and BMC males were significantly lower than normal males (Table 1). A family history of cancer was not a major risk factor, as only 4.3% of patients had a family history of cancer. Tobacco usage was found in 80.6% (TC) and 92.4% (BMC) of males, and 43.7% (TC) and 76.4% (BMC) of females. Tobacco usage in females was mostly through chewing while the males were exposed through smoking and/or chewing. Alcohol usage was found to be nearly in one-third of TC (30.6%) and BMC (31.4%) males. In contrast, only 3.4% of BMC females and none of the TC females used alcohol. Almost all male patients who used alcohol also used tobacco. The majority of BMC females had a tumour on the left side (61.4%). Nearly half of BMC male and female patients who visited the institute were in stage IVA, while such distinction was not observed either in TC males or females. Most of the OC patients were of grade 1 and 2 at the time of diagnosis, and the majority of the cases presented were of squamous cell origin (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic data of subjects

| Variables | Normal males (%) | TC male (%) | BMC male (%) | Normal females (%) | TC female (%) | BMC female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Available/total] | 505/505 | 202/202 | 124/124 | 396/404 | 99/99 | 114/114 |

| Average age (years) ± SE; P < | 33.7 ± 0.4 | 47.1 ± 0.9; 0.0001* | 45.5 ± 1.1; 0.0001* | 42.5 ± 1.0 | 51.4 ± 1.3; 0.0001* | 51.1 ± 0.9; 0.0001* |

| Average BMI ± SE; P < | 26.6 ± 0.4 | 22.9 ± 0.4; 0.0001* | 22.1 ± 0.4; 0.0001* | 23.9 ± 0.6 | 23.5 ± 0.6; 0.747 | 21.8 ± 0.6; 0.072 |

| Geographical distribution: [available/total] | 505/505 | 202/202 | 124/124 | 396/404 | 99/99 | 114/114 |

| Andhra Pradesh + Telangana | 500 (99.0) | 199 (98.5) | 117 (94.3) | 392 (99.0) | 98 (99.0) | 109 (95.6) |

| Other statesa | 5 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 7 (5.7) | 4 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (4.4) |

Available no. of subjects from whom data could be collected, Total total no of subjects, SE standard error, TC tongue cancer, BMC = buccal mucosa cancer

aAssam, Odisha, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Meghalaya

The statistically significant P values were kept in bold

*Statistically significant, if P < 0.05

Table 2.

Risk factors and clinical data of subjects

| Risk factors: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | TC male (%) | TC female (%) | BMC male (%) | BMC female (%) |

| Family history: [available/total] | 97/202 | 54/99 | 71/124 | 59/114 |

| Oral cancer | 5 (5.1) | 3 (5.5) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (3.4) |

| Other cancersa | 15 (15.5) | 5 (9.3) | 7 (9.9) | 5 (8.5) |

| No known family history | 77 (79.4) | 46 (85.2) | 62 (87.3) | 52 (88.1) |

| Tobacco: [available/total] | 160/202 | 80/99 | 105/124 | 89/114 |

| Chewersb | 69 (43.1) | 32 (40.0) | 55 (52.4) | 64 (71.9) |

| Smokers | 35 (21.9) | 2 (2.5) | 13 (12.4) | 3 (3.4) |

| Chewer + smoker | 25 (15.6) | 1 (1.2) | 29 (27.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| Non-users | 31 (19.4) | 45 (56.3) | 8 (7.6) | 21 (23.6) |

| Alcohol: [available/total] | 160/202 | 80/99 | 105/124 | 89/114 |

| Users | 49 (30.6) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (31.4) | 3 (3.4) |

| Non-users | 111 (69.4) | 80 (100.0) | 73 (69.5) | 86 (96.6) |

| Tobacco + alcohol: [available/total] | 160/202 | 80/99 | 105/124 | 89/114 |

| Tobacco + alcohol users | 47 (29.4) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (31.4) | 3 (3.4) |

| Clinical features: | ||||

| Tumor location: [available/total] | 202/202 | 99/99 | 124/124 | 114/114 |

| Left | 99 (49.0) | 52 (52.5) | 66 (53.2) | 70 (61.4) |

| Right | 99 (49.0) | 42 (42.4) | 56 (45.2) | 44 (38.6) |

| Otherc | 4 (2.0) | 5 (5.1) | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage: [available/total] | 104/202 | 63/99 | 71/124 | 82/114 |

| I | 22 (21.2) | 20 (31.8) | 11 (15.5) | 9 (11.0) |

| II | 29 (27.9) | 14 (22.2) | 14 (19.7) | 19 (23.1) |

| III | 17 (16.3) | 14 (22.2) | 9 (12.7) | 9 (11.0) |

| IVA | 36 (34.6) | 15 (23.8) | 36 (50.7) | 45 (54.9) |

| IVB | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade: [available/total] | 176/202 | 89/99 | 109/124 | 100/114 |

| 1 | 94 (53.4) | 49 (55.1) | 53 (48.6) | 54 (54.0) |

| 2 | 77 (43.8) | 39 (43.8) | 52 (47.7) | 44 (44.0) |

| 3 | 5 (2.8) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (3.7) | 2 (2.0) |

| Histology: [available/total] | 199/202 | 99/99 | 121/124 | 112/114 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 191 (96.0) | 96 (97.0) | 115 (95.0) | 101 (90.2) |

| Otherd | 8 (4.0) | 3 (3.0) | 6 (5.0) | 11 (9.8) |

| Metastasis: [no/available] | 15/202 | 15/99 | 14/124 | 9/114 |

| Recurrence: [no/available] | 32/202 | 11/99 | 21/124 | 20/114 |

| Relapse: [no/available] | 5/202 | 3/99 | 4/124 | 4/114 |

Available no. of subjects from whom data could be collected, Total total no of subjects. TC tongue cancer, BMC buccal mucosa cancer

aBreast, ovarian, stomach, thyroid cancers

bBetel leaf with areca nut, lime and tobacco or plain tobacco

cBilateral, tip of tongue, base of tongue, midline

dVerrucous carcinoma, Adenocarcinoma, Spindle cell sarcoma, Chondrosarcoma, Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Univariate analysis

OC risk in association with SNPs

Frequencies of the variants in normals and cases were within the HWE in all groups, except for BMC males, which showed deviation from HWE for CYP2D6*4 (χ2 = 5.37). CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ significantly lowered the risk of BMC in males (Table 3). Though CYP2D6*4 ‘AA’ was not associated with the cancers, the ‘A’ allele (OR = 1.89, CI = 1.05–3.43, P = 0.04) increased BMC risk in females (data not shown). Likewise, only the ‘G’ allele of CYP3A5*3 was found to be associated with increased risk of TC (OR = 1.67, CI = 1.04–2.69, P = 0.04) and BMC (OR = 1.62, CI = 1.03–2.54, P = 0.04) in females. SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ significantly increased the risk of TC and BMC in females, with or without adjusting age (Table 3). In males, though the genotypes did not influence the risk of either BMC or TC, the ‘A’ allele increased risk of BMC (OR = 2.03, CI = 1.06–3.87, P = 0.03).

Table 3.

Prevalence of CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2 polymorphisms in controls and oral cancer

| Subjects/gender/sample size | Variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6*4 | GG (%) | GA (%) | AA (%) | ||

| Control (M, N = 333) | 282 (84.7) | 49 (14.7) | 2 (0.6) | ||

|

TC (M, N = 124) OR (95% CI); P < |

108 (87.1) |

15 (12.1) 0.80 (0.43–1.48); 0.550 |

1 (0.8) 1.31 (0.12–14.55); 1.000 |

||

|

BMC (M, N = 83) OR (95% CI); P < |

77 (92.8) |

5 (6.0) 0.37 (0.14–0.97); 0.040* |

1 (1.2) 1.83 (0.16–20.47); 0.520 |

||

| Control (F, N = 224) | 194 (86.7) | 29 (12.9) | 1 (0.4) | ||

|

TC (F, N = 65) OR (95% CI); P < |

59 (90.8) |

6 (9.2) 0.68 (0.27–1.72); 0.520 |

0 (0.0) 1.09 (0.04–27.13); 1.000 |

||

|

BMC (F, N = 81) OR (95% CI); P < |

63 (77.7) |

16 (19.8) 1.69 (0.86–3.33); 0.140a |

2 (2.5) 6.16 (0.55–69.11); 0.150 |

||

| CYP3A5*3 | AA (%) | AG (%) | GG (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (M, N = 105) | 6 (5.7) | 48 (45.7) | 51 (48.6) | ||

|

TC (M, N = 133) OR (95% CI); P < |

8 (6.0) |

57 (42.9) 0.89 (0.28–2.75); 1.000 |

68 (51.1) 1.00 (0.33–3.06); 1.000 |

||

|

BMC (M, N = 57) OR (95% CI); P < |

3 (5.3) |

24 (42.1) 1.00 (0.23–4.35); 1.000 |

30 (52.6) 1.17 (0.27–5.05); 1.000 |

||

| Control (F, N = 264) | 23 (8.7) | 115 (43.6) | 126 (47.7) | ||

|

TC (F, N = 60) OR (95% CI); P < |

3 (5.0) |

19 (31.7) 1.27 (0.35–4.64); 1.000 |

38 (63.3) 2.32 (0.66–8.13); 0.210 |

||

|

BMC (F, N = 68) OR (95% CI); P < |

3 (4.4) |

23 (33.8) 1.53 (0.43–5.54); 0.770 |

42 (61.8) 2.56 (0.73–8.95); 0.210 |

||

| SULT1A1*2 | GG (%) | GA (%) | AA (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (M, N = 89) | 72 (80.9) | 15 (16.9) | 2 (2.2) | ||

|

TC (M, N = 87) OR (95% CI); P < |

64 (73.6) |

19 (21.8) 1.43 (0.67–3.04); 0.440 |

4 (4.6) 2.25 (0.39–12.71); 0.430 |

||

|

BMC (M, N = 64) OR (95% CI); P < |

43 (67.2) |

17 (26.5) 1.49 (0.86–4.18); 0.150b |

4 (6.3) 3.35 (0.58–19.07); 0.210 |

||

| Control (F, N = 272) | 218 (80.1) | 49 (18.1) | 5 (1.8) | ||

|

TC (F, N = 50) OR (95% CI); P < |

32 (64.0) |

17 (34.0) 2.36 (1.22–4.59); 0.020*c |

1 (2.0) 1.36 (0.15–12.05); 0.570 |

||

|

BMC (F, N = 47) OR (95% CI); P < |

26 (55.3) |

19 (40.4) 3.25 (1.67–6.34); 0.0008*d |

2 (4.3) 3.35 (0.62–18.17); 0.170 |

||

| CYP2D6*4 and SULT1A1*2 | GG + GG (%) | GG + GA (%) | GA + GG (%) | GA + GA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (F, N = 117) | 81 (69.2) | 21 (18.0) | 9 (7.7) | 4 (3.4) | |

|

TC (F, N = 31) OR (95% CI); P < |

20 (64.5) |

8 (25.8) 1.54 (0.6–3.99); 0.44 |

1 (3.2) 0.45 (0.05–3.76); 0.68 |

1 (3.2) 1.01 (1.11–9.56); 1.00 |

|

|

BMC (F, N = 40) OR (95% CI); P < |

14 (35.0) |

12 (30.0) 3.31 (1.33–8.20); 0.012* |

6 (15.0) 3.86 (1.19–12.54); 0.03* |

4 (10.0) 5.78 (1.29–25.87); 0.03* |

|

| CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2 | AA + GG (%) | AA + GA (%) | AG + GA (%) | GG + GA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (F, N = 211) | 15 (17.1) | 3 (1.4) | 15 (7.1) | 18 (8.5) | |

|

TC (F, N = 32) OR (95% CI); P < |

0 (0.0) |

2 (6.3) 22.14 (0.86–571.7); 0.05* |

6 (18.8) 13.00 (0.67–251.4); 0.03* |

7 (21.9) 12.56 (0.66–238.18); 0.03* |

|

|

BMC (F, N = 20) OR (95% CI); P < |

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

5 (25.0) 11.0 (0.56–216.6); 0.06 |

5 (25.0) 9.22 (0.47–180.26); 0.14 |

|

N number of samples, TC tongue cancer, BMC buccal mucosa cancer, M males, F females. GG + GG [CYP2D6*4 and SULT1A1*2] and AA + GG [CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2] were taken as reference genotypes for calculating OR for the remaining combinations

a2.29 (1.09–4.81); 0.029*, b2.4 (1.03–5.61); 0.043*, c2.38 (1.22–4.65); 0.011* and d3.23 (1.65–6.31); 0.001* were significant when adjusted for age

The statistically significant P values were kept in bold

*Statistically significant, if P < 0.05

Co-occurrence of CYP2D6*4 and SULT1A1*2

3–5Folds increased risk of BMC in females was found with genotype combinations GG + GA, GA + GG, and GA + GA (Table 3).

Co-occurrence of CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2

AA + GA, AG + GA and GG + GA significantly increased TC risk in females (Table 3), although no such association was observed in males (data not shown). The combination of genotypes at all three SNPs did not influence risk of TC and BMC, in males or females (data not shown).

OC risk association of SNPs among tobacco and alcohol users vs non-users

Males with CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ and exposed to alcohol had 9.4-folds risk of BMC when compared to non-users of alcohol. Increased risk (OR = 15.4) of BMC was found in males with CYP3A5*3 ‘AA’ genotype and tobacco chewing habit when compared to the non-chewers (Table 4). On the other hand, SULT1A1*2 variants had no impact on the cancer risk with tobacco and alcohol use (data not shown).

Table 4.

Disease risk association with CYP2D6*4 and CYP3A5*3 in alcohol users and tobacco chewers amongst TC and BMC cases

| Cancer/gender | Variants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6*4 | GG (%) | GA (%) | AA (%) |

| Alcohol | |||

| Non-users (TC, M, N = 66) | 59 (89.4) | 7 (10.6) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Users (TC, M, N = 37) OR (95% CI); P < |

31 (83.8) |

5 (13.5) 1.36 (0.4–4.64); 0.750 |

1 (2.7) 5.67 (0.22–143.31); 0.350 |

| Non-users (BMC, M, N = 49) | 47 (96.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) |

|

Users (BMC, M, N = 24) OR (95% CI); P < |

20 (83.3) |

4 (16.7) 9.4 (1.0–89.44); 0.039* |

0 (0.0) 0.77 (0.03–19.78); 1.000 |

| Non-users (TC, F, N = 52) | 48 (92.3) | 4 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) |

|

Users (TC, F, N = 0) OR (95% CI); P < |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) - |

0 (0.0) - |

| Non-users (BMC, F, N = 64) | 49 (76.6) | 13 (20.3) | 2 (3.1) |

|

Users (BMC, F, N = 1) OR (95% CI); P < |

1 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) 1.22 (0.05–31.76); 1.000 |

0 (0.0) 6.6 (0.21–206.74); 1.000 |

| Tobacco chewing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-users (TC, M, N = 58) | 3 (5.2) | 25 (43.1) | 30 (51.7) |

|

Users (TC, M, N = 40) OR (95% CI); P < |

3 (7.5) |

19 (47.5) 0.76 (0.14–4.19); 1.000 |

18 (45.0) 0.6 (0.11–3.30); 0.670 |

| Non-users (BMC, M, N = 20) | 3 (15.0) | 10 (50.0) | 7 (35.0) |

|

Users (BMC, M, N = 25) OR (95% CI); P < |

0 (0.0) |

9 (36.0) 6.33 (0.29–139.35); 0.240 |

16 (64.0) 15.4 (0.7–337.5); 0.046* |

| Non-users (TC, F, N = 32) | 2 (6.3) | 13 (40.6) | 17 (53.1) |

|

Users (TC, F, N = 15) OR (95% CI); P < |

1 (6.7) |

3 (20.0) 0.46 (0.03–6.93); 0.530 |

11 (73.3) 1.29 (0.10–16.04); 1.000 |

| Non-users (BMC, F, N = 14) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (28.6) | 10 (71.4) |

|

Users (BMC, F, N = 37) OR (95% CI); P < |

3 (8.1) |

13 (35.1) 0.43 (0.02–10.00); 1.000 |

21 (56.8) 0.29 (0.01–6.20); 0.540 |

N number of samples, TC Tongue cancer, BMC Buccal mucosa cancer, M Males, F Females

The statistically significant P values were kept in bold

*Statistically significant, if P < 0.05

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis

BMC vs TC

BMC females with CYP2D6*4 ‘GG’ aged > 50 years or with PNS survived significantly shorter than TC females (Table 5). Similarly, BMC females aged > 50years or with high inflammatory infiltrate or PNS or tobacco chewing survived for a significantly shorter time with CYP3A5*3 ‘GG’, compared to TC females. In contrast, TC males with ‘GG’ and mild inflammatory infiltrate had significantly shorter survival than BMC males. TC males with LVS and BMC males with alcohol use, and carriers of ‘AG’ survived shorter than BMC males and TC males, respectively. BMC males, carriers of SULT1A1*2 ‘GG’ exhibited worse survival than TC males aged > 50 years or with tobacco chewing. The ‘GA’ variant exhibited worse survival for BMC females than TC females with age > 50 years, grade 1 tumour, tobacco chewing.

Table 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for BMC and TC patients

| Variables/genotype | Mean ± SE (months) | Log rank | P value | Mean ± SE (months) | Log rank | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6*4 | F | M | ||||||

| > 50 years | GG | BMC | 27.53 ± 3.21 | 7.105 | 0.008* | 32.06 ± 4.34 | 0.702 | 0.402 |

| TC | 40.45 ± 3.07 | 30.46 ± 2.33 | ||||||

| PNS | GG | BMC | 16.61 ± 4.86 | 4.034 | 0.045* | 19.06 ± 3.70 | 1.216 | 0.270 |

| TC | 39.53 ± 7.87 | 24.88 ± 3.59 | ||||||

| CYP3A5*3 | F | M | ||||||

| > 50 yrs | GG | BMC | 28.01 ± 3.47 | 7.159 | 0.007* | 29.19 ± 2.93 | 0.24 | 0.624 |

| TC | 42.82 ± 2.80 | 44.43 ± 4.49 | ||||||

| Mild Inflammatory Infiltrate | GG | BMC | 21.6 ± 6.62 | 2.597 | 0.107 | 42.54 ± 7.43 | 4.062 | 0.044* |

| TC | 44.71 ± 4.06 | 18.2 ± 8.74 | ||||||

| High Inflammatory Infiltrate | BMC | 17.82 ± 6.98 | 4.046 | 0.044* | NR$ | 0.667 | 0.414 | |

| TC | 40.26 ± 0.18 | 34.5 ± 11.19 | ||||||

| LVS | AG | BMC | NR$ | 2.000 | 0.157 | 27.08 ± 7.21 | 3.925 | 0.048* |

| TC | 18.53 ± 0.00 | 3.96 ± 3.11 | ||||||

| PNS | GG | BMC | 15.71 ± 3.16 | 5.846 | 0.016* | 8.4 ± 0.00 | 0.108 | 0.742 |

| TC | 34.94 ± 2.18 | 26.02 ± 7.35 | ||||||

| Tobacco chewing | GG | BMC | 33.18 ± 3.66 | 4.176 | 0.041* | 44.72 ± 4.97 | 1.156 | 0.282 |

| TC | 45.15 ± 2.13 | 32.88 ± 4.47 | ||||||

| Alcohol use | AG | BMC | NR# | NR# | 13.53 ± 3.57 | 5.374 | 0.020* | |

| TC | NR# | 39.08 ± 4.80 | ||||||

| SULT1A1*2 | F | M | ||||||

| > 50 yrs | GG | BMC | 20.52 ± 4.39 | 2.435 | 0.119 | 21.25 ± 3.02 | 4.733 | 0.030* |

| TC | 36.82 ± 3.83 | 42.64 ± 4.74 | ||||||

| GA | BMC | 22.62 ± 3.32 | 9.095 | 0.003* | 20.56 ± 7.19 | 0.563 | 0.453 | |

| TC | NR$ | 44.52 ± 5.09 | ||||||

| Grade 1 | GA | BMC | 23.79 ± 3.26 | 8.204 | 0.004* | 35.43 ± 5.13 | 0.207 | 0.649 |

| TC | 48.69 ± 3.37 | 35.61 ± 5.26 | ||||||

| Tobacco chewing | GG | BMC | 23.11 ± 4.49 | 2.079 | 0.149 | 20.9 ± 4.60 | 5.295 | 0.021* |

| TC | 33.72 ± 3.82 | 38.22 ± 4.63 | ||||||

| GA | BMC | 21.87 ± 2.84 | 5.425 | 0.020* | 31.37 ± 4.77 | 0.000 | 0.983 | |

| TC | 57.7 ± 0.00 | 36.76 ± 6.87 | ||||||

| CYP2D6*4 | BMC | TC | ||||||

| Recurrence | GG | F | 32.43 ± 6.42 | 2.427 | 0.119 | 35.78 ± 4.34 | 6.541 | 0.011* |

| M | 20.86 ± 4.64 | 21.86 ± 3.48 | ||||||

| CYP3A5*3 | BMC | TC | ||||||

| Grade 2 | GG | F | 23.28 ± 7.70 | 3.985 | 0.046* | 33.82 ± 4.24 | 1.044 | 0.307 |

| M | 46.55 ± 6.14 | 21.81 ± 5.39 | ||||||

| Stage II | AG | F | NR# | NR# | 18.53 ± 0.00 | 4.784 | 0.029* | |

| M | NR# | 42.81 ± 3.86 | ||||||

| Mild inflammatory infiltrate | GG | F | 21.6 ± 6.62 | 0.499 | 0.480 | 44.71 ± 4.06 | 6.846 | 0.009* |

| M | 42.54 ± 7.43 | 18.2 ± 8.74 | ||||||

| Recurrence | GG | F | 23.55 ± 5.36 | 0.751 | 0.386 | NR$ | 7.722 | 0.005* |

| M | 27.21 ± 6.46 | 19.33 ± 4.57 | ||||||

| Tobacco chewing | AG | F | 42.09 ± 2.68 | 5.814 | 0.016* | NR$ | 0.931 | 0.335 |

| M | 22.23 ± 6.39 | 39.99 ± 4.07 | ||||||

| SULT1A1*2 | BMC | TC | ||||||

| Stage II | GG | F | NR# | NR# | 29.68 ± 11.50 | 4.951 | 0.026* | |

| M | NR# | 51.73 ± 2.38 | ||||||

TC Tongue cancer, BMC Buccal mucosa cancer, M Males, F Females, SE Standard error, NR$ Not reached due to lack of events, NR# Not reported due to lack of samples

The statistically significant P values were kept in bold

*Statistically significant, if P < 0.05

Females vs males

TC males with recurrence and CYP2D6*4 ‘GG’ had worse survival than females. Tobacco chewing male carriers of CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ survived worse than females. CYP3A5*3 ‘GG’ was associated with worse survival among males with mild inflammatory infiltrate and recurrence than females. TC females with stage II cancer and CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ or SULT1A1*2 ‘GG’s had lower survival than males (Table 5).

Wild type vs variants

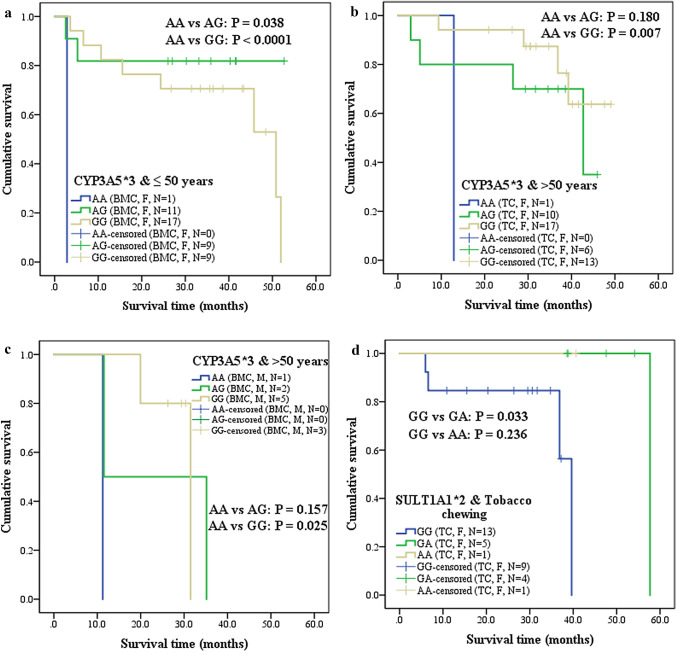

CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ and ‘GG’ significantly increased survival of BMC females aged ≤ 50 years, compared to ‘AA’ (Fig. 1a). TC females and BMC males above 50 years and with ‘AA’ survived shorter than ‘GG’ (Fig. 1b, c). Tobacco chewing TC females with SULT1A1*2 ‘GG’ exhibited worse survival than ‘GA’ (Fig. 1d). TC females with CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ and high inflammatory infiltrate showed lower survival when compared to ‘GG’ (Fig. 2a). Grade 1 BMC females (Fig. 2b) with CYP3A5*3 ‘AA’ showed worse survival than ‘AG’. BMC males with mild inflammatory infiltrate, BMC females with moderate inflammatory infiltrate and TC females with high inflammatory infiltrate, who were carriers of ‘AA’ survived shorter than ‘GG’ (Fig. 2c-e). On contrary, TC males with SULT1A1*2 ‘GG’ and PNS survived shorter than ‘GA’ (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier 5 year cumulative survival analysis of Wild type vs Mutant genotypes in oral cancer patients, stratified into tongue cancer (TC) and buccal mucosa cancer (BMC), gender, age groups of ≤ 50 years and > 50 years, tobacco chewing habit and CYP3A5*3 or SULT1A1*2. a BMC females aged ≤ 50 years and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs AG, AA vs GG); b TC females aged > 50 years and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs GG); c BMC males aged > 50 years and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs GG); d TC females who were tobacco chewers and carriers of SULT1A1*2 (GG vs GA)

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier 5 year cumulative survival analysis of Wild type vs Mutant genotypes in oral cancer patients, stratified into tongue cancer (TC) and buccal mucosa cancer (BMC), gender and CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3 or SULT1A1*2 with clinical factors. a TC females with high inflammatory infiltrate and carriers of CYP2D6*4 (GG vs GA); b BMC females with grade 1 tumour and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs AG); c BMC males with mild inflammatory infiltrate and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs GG); d BMC females with moderate inflammatory infiltrate and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs GG); e TC females with high inflammatory infiltrate and carriers of CYP3A5*3 (AA vs GG); f TC males with PNS and carriers of SULT1A1*2 (GG vs GA)

Multivariate analysis

Logistic regression analysis

CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ had 2.29-folds increased risk (P = 0.029) for BMC females (P = 0.029) but not males, when adjusted for age. SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ had 2.4-folds increased risk for BMC males. Similarly, SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ significantly increased risk for both TC (OR = 2.38) and BMC (OR = 3.23), among females (Table 3).

Cox regression analysis

CYP2D6*4 had no impact on HRs of the patients, while CYP3A5*3 did not impact HRs of BMC or TC males. CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ and ‘GG’ had decreased HRs for BMC females when inflammatory infiltrate alone or along with other covariates, LVS, PNI, PNS, metastasis, recurrence, and relapse was adjusted, while ‘AG’ was associated with lower HR when the grade was adjusted (Table 6). On the other hand, the ‘AG’ and ‘GG’ variants exhibited lower HRs for TC females when recurrence was adjusted, while ‘GG’ was associated with decreased HRs when a grade or inflammatory infiltrate or LVS was adjusted. With age, grade, stage, tobacco, and alcohol use as covariates, ‘GG’ conferred lowered HRs for TC females (Model 6). Interestingly, the decreased HRs for TC females was also noted for SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ when tobacco use and alcohol use were covariates. However, SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ had decreased hazards for TC males after adjusting for inflammatory infiltrate, LVS, PNI, PNS, metastasis, recurrence, and relapse, as shown in model 7.

Table 6.

Cox regression analysis for BMC and TC patients stratified by gender

| Covariate in the model | Genotype | Cancer [HR (95% CI); P <] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMC M | BMC F | TC M | TC F | ||

| Model 1: adjusted for grade | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 1.64 (0.18–14.84); 0.662 | 0.05 (0.003–0.89); 0.041* | 0.69 (0.20–2.42); 0.563 | 0.21 (0.04–1.12); 0.067 |

| GG | 0.92 (0.10–8.21); 0.943 | 0.39 (0.05–3.19); 0.383 | 0.89 (0.25–3.2); 0.856 | 0.16 (0.03–0.76); 0.022* | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 1.00 (0.35–2.87); 1.000 | 1.93 (0.59–6.28); 0.277 | 0.86 (0.31–2.41); 0.780 | 0.52 (0.13–2.07); 0.351 |

| AA | 1.00 (0.23–4.37); 1.000 | 1.09 × 10–6 (0.00-NR$); 0.990 | 1.26 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.984 | NR# | |

| Model 2: Adjusted for inflammatory infiltrate | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 2.26 (0.25–20.21); 0.466 | 0.01 (0.001–0.24); 0.003* | 0.41 (0.09–1.95); 0.261 | 0.29 (0.05–1.65); 0.163 |

| GG | 0.86 (0.09–8.59); 0.900 | 0.05 (0.004–0.62); 0.02* | 0.70 (0.16–3.11); 0.634 | 0.16 (0.03–0.88); 0.035* | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 0.48 (0.10–2.4); 0.371 | 2.82 (0.51–15.48); 0.234 | 0.91 (0.29–2.85); 0.876 | 0.44 (0.08–2.35); 0.340 |

| AA | 0.73 (0.14–3.79); 0.704 | 1.20 (0.00- NR$); 1.000 | 1.82 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.987 | 1.54 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.989 | |

| Model 3: Adjusted for LVS | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 2.95 (0.36–24.44); 0.315 | 0.10 (0.01–1.15); 0.064 | 1.57 (0.39–6.33); 0.526 | 0.24 (0.05–1.3); 0.098 |

| GG | 1.07 (0.13–8.95); 0.948 | 0.48 (0.06–3.76); 0.488 | 1.24 (0.34–4.57); 0.744 | 0.16 (0.03–0.78); 0.023* | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 0.46 (0.15–1.4); 0.172 | 1.77 (0.58–5.43); 0.315 | 1.00 (0.38–2.63); 0.997 | 0.49 (0.14–1.77); 0.275 |

| AA | 0.52 (0.12–2.26); 0.380 | 5.96 × 10–7 (0.00- NR$); 0.989 | 4.45 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.981 | 1.36 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.988 | |

| Model 4: adjusted for recurrence | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 0.86 (0.09–8); 0.898 | 0.46 (0.04–4.83); 0.515 | 0.62 (0.18–2.18); 0.460 | 0.09 (0.01–0.63); 0.015* |

| GG | 0.49 (0.05–4.45); 0.528 | 1.22 (0.15–9.76); 0.853 | 0.88 (0.25–3.07); 0.844 | 0.06 (0.01–0.41); 0.004* | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 0.45 (0.15–1.35); 0.152 | 1.50 (0.51–4.4); 0.464 | 0.79 (0.31–2.03); 0.628 | 0.35 (0.09–1.46); 0.150 |

| AA | 0.49 (0.11–2.19); 0.348 | 9.80 × 10–7 (0.00- NR$); 0.984 | 5.88 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.982 | 1.19 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.988 | |

| Model 5: adjusted for tobacco use, alcohol | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 4.22 (0.45–39.97); 0.210 | 0.18 (0.02–1.89); 0.154 | 0.68 (0.19–2.42); 0.548 | 0.54 (0.10–2.83); 0.470 |

| GG | 2.54 (0.24–26.97); 0.439 | 0.51 (0.06–4.06); 0.528 | 0.83 (0.24–2.88); 0.766 | 0.27 (0.05–1.37); 0.115 | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 0.45 (0.15–1.35); 0.155 | 1.25 (0.43–3.66); 0.686 | 1.11 (0.40–3.05); 0.839 | 0.10 (0.01–0.87); 0.037* |

| AA | 0.52 (0.12–2.29); 0.387 | 5.73 × 10–7 (0.00- NR$); 0.989 | 2.72 × 10–6 (0.00- NR$); 0.987 | 9.05 × 10–7 (0.00- NR$); 0.989 | |

| Model 6: adjusted for age, stage, grade, tobacco use, alcohol | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 8.66 × 104 (7.28 × 10–125-1.03 × 10134); 0.940 | 0.12 (0.01–2.35); 0.164 | 1.26 (0.15–10.3); 0.829 | 0.12 (0.00–3.82); 0.228 |

| GG | 5.31 × 104 (4.45 × 10–125-6.32 × 10133); 0.943 | 0.95 (0.10–8.78); 0.965 | 1.75 (0.20–15.58); 0.616 | 0.02 (0.00–0.86); 0.042* | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 1.00 (0.19–5.27); 1.000 | 1.79 (0.38–8.41); 0.462 | 0.63 (0.17–2.38); 0.497 | 0.14 (0.01–1.4); 0.094 |

| AA | 1.00 (0.14–7.01); 1.000 | 9.45 × 10–9 (0.00- NR$); 0.988 | 0.04 × 10–3 (3.56 × 10–213-1.94 × 10273); 0.967 | NR# | |

| Model 7: adjusted for inflammatory infiltrate, LVS, PNI, PNS, metastasis, recurrence, relapse | |||||

| CYP3A5*3 | AG | 1 × 10–5 (6.62 × 10–59-2.00 × 1048); 0.856 | 3 × 10–4 (9.73 × 10–7-0.07); 0.004* | 0.10 (0.001–20.86); 0.402 | 3 × 10–4 (3.87 × 10–87-2.95 × 1079); 0.935 |

| GG | NR# | 0.02 (0.001–0.62); 0.026* | 0.90 (0.02–52.67); 0.961 | NR# | |

| SULT1A1*2 | GA | 23.76 (0.18–3060.68); 0.201 | 0.51 (3.89 × 10–43-6.70 × 1041); 0.989 | 0.08 (0.01–0.65); 0.018* | 7 × 107 (2.52 × 10–31-2.43 × 1046); 0.688 |

| AA | 8.76 (0.17–456.26); 0.282 | NR# | NR# | NR# | |

TC tongue cancer, BMC buccal mucosa cancer, M males, F females. NR$ not reached, NR# not reported due to lack of samples

The statistically significant P values were kept in bold

*Statistically significant, if P < 0.05

Data was analysed for CYP2D6*4 also, but is not shown in the table, as it did not show any significant difference in any of the model generated

Bioinformatics

Our preliminary bioinformatic approach using SNPnexus predicted that CYP2D6*4 is in the splice site whereas CYP3A5*3 was 237 bases away from the splice junction. SULT1A1*2 was shown to be damaging by SIFT score; however, the Polyphen score indicated that it is benign. Analysis using HSF3.0 predicted that CYP2D6*4 potentially alters splicing due to the activation of an intronic cryptic acceptor site. CYP3A5*3 and SULT1A1*2 had no effect on splicing. We also found, using ENCODE, the presence of a CTCF binding site upstream of CYP2D6 only in H1-hESC cell line and a CpG island with CpG count of 95 within the gene. Neither CTCF binding sites nor CpG islands were present within or nearby CYP3A5. A CTCF binding site within SULT1A1 was noted in all the 9 cell lines whereas another CTCF binding site was found downstream of the gene but only in 3 cell lines. SULT1A1 also showed the presence of three CpG islands, the longer one in the promoter region (CpG count: 76) and shorter ones within the gene (CpG count: 43) and downstream of the gene (CpG count: 43) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Discussion

Oral cancer (OC) is 17th common cancer worldwide. Contrastingly, it is the most common cancer among Indian men (16.1% of all cancers), the fourth most common cancer amongst Indian women (4.8% of all cancers) (Globocan 2018). OC is the leading cause of death in men, in India. 5 year survival rate of OC is 84% in early stages and 39% in advanced stages, in USA (NCI-SEER program 2020) and 82% in early stages and 27% for advanced stages, in India (Iype et al. 2001). Low survival rates of OC patients in India is mainly attributed to the late diagnosis of cancer in advanced stages.

CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3, and SULT1A1*2 are generally studied in breast cancer patients as tamoxifen given to breast cancer patients is metabolized by these enzymes. However, these enzymes also metabolize other anticancer drugs, including OC drugs. There is a severe paucity of information regarding the association of these SNPs i.e., CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3, and SULT1A1*2, with OC in a site and gender-specific manner, especially in Indians. Hence, we studied the differential risk association of the CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3, and SULT1A1*2 with BMC and TC, and altered survival of the patients, in a gender and age-dependent manner. Frequencies of all the three variants in our normal population agree with other studies from India but differed from other populations (Supplementary Table 1).

Only 4.3% of patients, in our study, had a family history of cancer, tobacco, and alcohol being major risk factors. This is in line with a study of oral and pharyngeal cancers (Garavello et al. 2008). 80.6% (TC) and 92.4% (BMC) of males and 43.7% (TC) and 76.4% (BMC) of females were tobacco users (Table 2). Tobacco usage in females is mainly attributed to tobacco chewing whereas in males it is through smoking and/or chewing. 61.4% of BMC females had tumour on the left side. Another study from Tamil Nadu, India (Padma et al. 2017), also reported that 65.2% BMC patients had left-sided disease, though the reason is unknown. Nearly half of BMC patients were in stage IVA at the time of diagnosis. Late presentation to the hospital and subsequent high mortality rates for OC, due to poverty and lack of awareness, is a major problem in India.

Our study reported that CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ decreased risk in BMC males (OR = 0.37) but not females. This finding differed from a study on North Indian males (Shukla et al. 2012) that showed an increased risk of HNSCC with CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’. The homozygous variant ‘AA’ did not show any significant association in our study (Table 3), but it was reported to increase the risk of HNSCC by 2.32 folds in a study (Ruwali and Parmar 2010). Our study did not report the association of CYP3A5*3 with any subtype of OC. This is in agreement with a report (Azarpira et al. 2011) which did not show any association with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. In contrast to CYP2D6*4, we found that SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ increased the risk of TC and BMC in females, with or without adjusting age. Similarly, ‘GA’ variant after adjusting for age also increased the risk in BMC males. In a study by Santos et al. (2012), SULT1A1*2 did not show any association with OC. But another study (Chung et al. 2009) reported a decreased risk of OC in betel quid chewers and smokers with SULT1A1*2. This indicated the complexity of underlying molecular mechanisms associated with OC. We also noted the effect of co-occurrence of these SNPs which differed with that of individual SNPs.

According to our study, alcohol consumption increased the risk of BMC by 9.4 folds in males who also carried CYP2D6*4 ‘GA’ (Table 4), suggesting possible interaction of variants with alcohol to increase cancer risk. Alcohol consumption and the presence of variants (GA/AA) of CYP2D6*4 increased the risk of HNSCC by 3.33-folds, in a study (Shukla et al. 2012). Our findings also indicated the effect of tobacco on OC risk with SNPs varied with the mode of tobacco usage, cancer subsite, and gender; tobacco chewers with CYP3A5*3 ‘AA’, had 15-folds increased BMC risk in males when compared to non-users. This may be caused due to relatively lesser detoxification of the carcinogens in tobacco due to lowered enzyme expression. The increased risk of HNSCC, among tobacco chewers and variants (GA/AA) of CYP2D6*4, by 5.06-folds (P = 0.0038) was reported (Shukla et al. 2012). However, the mechanism of interaction between the SNPs, nature of risk factors, cancer subsite, and gender is unknown.

We found that risk factors and clinical factors, in association with the SNPs, differentially impacted the survival of BMC and TC patients in males and females. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports that studied the association of the SNPs with OC patients’ survival. Few sporadic reports studied the association of these SNPs with breast cancer (Abreu et al. 2015; Bray et al. 2010; Goetz et al. 2005; Wegman et al. 2007) and hepatocellular cancer (Jiang et al. 2015). In our study, BMC females aged > 50yrs or with PNS and genotype CYP2D6*4 ‘GG’ or CYP3A5*3 ‘GG’, survived significantly shorter than TC females. But TC males with mild inflammatory infiltrate and CYP3A5*3 ‘GG’ had significantly shorter survival than BMC males. TC females with SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ exhibited worse survival than BMC females with age > 50 years, grade 1 tumour, tobacco chewing. Stage II TC females with CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ or SULT1A1*2 ‘GG’ had lower survival than males (Table 5). CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ and ‘GG’ genotypes significantly increased survival of BMC females aged ≤ 50 years, compared to ‘AA’ (Fig. 1). BMC males with mild inflammatory infiltrate, BMC females with moderate inflammatory infiltrate, and TC females with high inflammatory infiltrate, who were carriers of ‘AA’ had lower survival time than ‘GG’ (Fig. 2). Our data suggested that polymorphic variants in association with clinical and risk factors influenced survival in a site and gender-specific manner.

Gender and site-specific variations were observed for the HRs when clinical and risk factors were covariates. CYP3A5*3 ‘AG’ and ‘GG’ had decreased HRs for BMC females when inflammatory infiltrate alone or along with LVS, PNI, PNS, metastasis, recurrence, and relapse were adjusted. However, a GWAS analysis in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients (Kiyotani et al. 2012) showed that CYP2D6 along with C10orf11 and ABCC2 had cumulative effects on recurrence-free survival (RFS) (P = 2.28 × 10–12), and adjusted HR for risk of recurrence for patients carrying three or more risk alleles increased from 6.51-fold (three risk alleles) to 119.51-fold (five risk alleles) compared with those carrying one risk allele. We also noted that with age, grade, stage, tobacco, and alcohol use as adjusted covariates, ‘GG’ conferred lowered HRs for TC in females. In a study on cancer patients (Leskela et al. 2011), CYP3A5*3 showed significantly decreased HR of 0.51 (P < 0.012) when adjusted for treatment schedule and age. Interestingly, the decreased HRs for TC in females was also noted for SULT1A1*2 ‘GA’ when tobacco use and alcohol use were covariates (Table 6).

Bioinformatic analyses using SNPnexus and HSF 3.0 predicted that CYP2D6*4 alters splicing due to the activation of an intronic cryptic acceptor site. The analysis also found that CYP3A5*3 is located 237 bases away from the splice junction and SULT1A1*2 mutation is damaging. Using ENCODE, we identified the presence of a CTCF binding site upstream of CYP2D6. A CTCF binding site within the gene and another downstream of the gene were identified in SULT1A1. In CYP2D6, we noted an intragenic CpG island that spans through exonic regions 2, 3, 4, and intronic regions 2, 3. Three CpG islands located in the promoter region, within the gene and downstream of the gene were identified in SULT1A1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The presence of a CpG island in the promoter regions of CYP2D6 (Zhang et al. 2016) and SULT1A1 (Voisin et al. 2015) were reported, but intragenic and downstream islands were not yet reported. It is well established that CpG islands regulate transcription whereas CTCF binding sites regulate transcription, 3D structure of the chromatin, insulation, and RNA splicing. Though the presence of these epigenetic markers has been identified using bioinformatic tools, their in vivo presence and implication on gene expression needs to be evaluated experimentally.

The limitations of the study include: (a) relatively smaller sample size due to classification of samples by tumor site and gender; (b) cases and normals were mostly from the two telugu states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, thus the results cannot be generalized to other racial and ethnic groups; (c) cancer recurrence or metastasis information collected might be incomplete due to lack of strictly defined screening or follow up regimen by patients.

In conclusion, our hospital-based study is the first report that studies the association of CYP2D6*4, CYP3A5*3, and SULT1A1*2 with OC in site and gender-dependent manner, in the same set of less heterogeneous samples. The rationale for this study is that anti-cancer drug tamoxifen being explored to be given to HNSCC patients (Elkin et al. 2008). The three enzymes studied also impact the efficacy of various anti-cancer drugs (Cronin-Fenton et al. 2014; Egbelakin et al. 2011; Leskela et al. 2011; Calinski et al. 2015; Frederiks et al. 2015; Tsuchiya et al. 2008) and palliative care medicines of OC (Washio et al. 2011). In addition, genetic abnormalities also have been shown to increase disease susceptibility. Hence, as these enzymes are crucial for pharmacokinetics, efficacy and adverse effects of life saving drugs, and also alter cancer susceptibility, understanding the prevalence of polymorphisms of these enzymes helps in devising alternate strategies for the people with defective enzymes, where the activity of these enzyme(s) is compromised due to genetic aberrations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by Basavatarakam Indo-American Cancer Hospital & Research Institute (BIACH & RI). Mrs. Sarika is thankful to Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India for the award of Junior Research Fellow and to Acharya Nagarjuna University, Nagarjuna Nagar, AP, India for registering Mrs. Sarika for her doctoral degree. We also express our deep gratitude to Dr. V.V.T.S. Prasad for the invaluable help provided during the study. The authors would like to thank the Institute’s administration and the medical team for help during the study. The authors also acknowledge the help provided by N. Sateesh and N.L.S.S. Srivani for their assistance in collecting the data.

Author contributions

KP conceptualized and reviewed the manuscript. SD designed the analysis, conducted the experiments, collected the data, performed the statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the publication.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional (Basavatarakam Indo-American Cancer Hospital & Research Institute, Hyderabad—500034) and/or national research committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Abreu MH, Gomes M, Menezes F, Afonso N, Abreu PH, Medeiros R, et al. CYP2D6*4 polymorphism: a new marker of response to hormonotherapy in male breast cancer? Breast. 2015;24(4):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan S. Genetic polymorphisms of sulfotransferases (SULT1A1 and SULT1A2) in a Turkish population. Biochem Genet. 2010;48(11–12):987–994. doi: 10.1007/s10528-010-9387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarpira N, Ashraf MJ, Khademi B, Darai M, Hakimzadeh A, Abedi E. Study the polymorphism of CYP3A5 and CYP3A4 loci in Iranian population with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38(8):5443–5448. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat GA, Shah IA, Rafiq R, Nabi S, Iqbal B, Lone MM, et al. Family history of cancer and the risk of squamous cell carcinoma of oesophagus: a case-control study in Kashmir, India. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(3):524–532. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth Depaz IM, Toselli F, Wilce PA, Gillam EM. Differential expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes from the CYP2C subfamily in the human brain. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;43(3):353–357. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.061242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray J, Sludden J, Griffin MJ, Cole M, Verrill M, Jamieson D, et al. Influence of pharmacogenetics on response and toxicity in breast cancer patients treated with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(6):1003–1009. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calinski DM, Zhang H, Ludeman S, Dolan ME, Hollenberg PF. Hydroxylation and N-dechloroethylation of Ifosfamide and deuterated Ifosfamide by the human cytochrome p450s and their commonly occurring polymorphisms. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43(7):1084–1090. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.063628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YT, Hsieh LL, Chen IH, Liao CT, Liou SH, Chi CW, et al. Sulfotransferase 1A1 haplotypes associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma susceptibility in male Taiwanese. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(2):286–294. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin-Fenton DP, Damkier P, Lash TL. Metabolism and transport of tamoxifen in relation to its effectiveness: new perspectives on an ongoing controversy. Future Oncol. 2014;10(1):107–122. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels J, Kadlubar S. Pharmacogenetics of SULT1A1. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15(14):1823–1838. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daripally S, Nallapalle SR, Katta S, Prasad VV. Susceptibility to oral cancers with CD95 and CD95L promoter SNPs may vary with the site and gender. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(10):7817–7830. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayem Ullah AZ, Lemoine NR, Chelala C. A practical guide for the functional annotation of genetic variations using SNPnexus. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14(4):437–447. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Beroud G, Claustres M, Beroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(9):e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbelakin A, Ferguson MJ, MacGill EA, Lehmann AS, Topletz AR, Quinney SK, et al. Increased risk of vincristine neurotoxicity associated with low CYP3A5 expression genotype in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(3):361–367. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkin AD, Jacobs CD. Tamoxifen for salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma: report of two cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(10):1151–1153. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiks CN, Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E. Genetic polymorphisms and paclitaxel- or docetaxel-induced toxicities: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(10):935–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedigk A, Sangkuhl K, Whirl-Carrillo M, Klein T, Leeder JS. Prediction of CYP2D6 phenotype from genotype across world populations. Genet Med. 2016;19(1):69–76. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavello W, Foschi R, Talamini R, La Vecchia C, Rossi M, Dal Maso L, et al. Family history and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(8):1827–1831. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Globocan (2018) Estimated cancer incidence mortality and incidence worldwide in 2018. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/fact-sheets-populations. Αccessed 7 May 2019

- Goetz MP, Rae JM, Suman VJ, Safgren SL, Ames MM, Visscher DW, et al. Pharmacogenetics of tamoxifen biotransformation is associated with clinical outcomes of efficacy and hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9312–9318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung RJ, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Malaveille C, Hautefeuille A, Donato F, et al. GST, NAT, SULT1A1, CYP1B1 genetic polymorphisms, interactions with environmental exposures and bladder cancer risk in a high-risk population. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(4):598–604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J. 2005;5(1):6–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iype EM, Pandey M, Mathew A, Thomas G, Sebastian P, Nair MK. Oral cancer among patients under the age of 35 years. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47(3):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Chen L, Yang YC, Wang XM, Wang RY, Li L, et al. CYP3A5 Functions as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating mTORC2/Akt signaling. Cancer Res. 2015;75(7):1470–1481. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. Tobacco use and oral cancer: a global perspective. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(4):328–339. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2001.65.4.tb03403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyotani K, Mushiroda T, Tsunoda T, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies locus at 10q22 associated with clinical outcomes of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer patients in Japanese. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(7):1665–1672. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lamba J, Assem M, Schuetz J, et al. Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet. 2001;27(4):383–391. doi: 10.1038/86882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskela S, Jara C, Leandro-Garcia LJ, Martínez A, Garcia-Donas J, Hernando S, et al. Polymorphisms in cytochromes P450 2C8 and 3A5 are associated with paclitaxel neurotoxicity. Pharmacogenomics J. 2011;11(2):121–129. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes BA, Emerenciano M, Goncalves BA, Vieira TM, Rossini A, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS. Polymorphisms in CYP1B1, CYP3A5, GSTT1, and SULT1A1 are associated with early age acute leukemia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0127308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI-SEER program (2020) https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html. Accessed 21 Mar 2020

- Nida S, Javid B, Akbar M, Idrees S, Adil W, Ahmad GB. Gene variants of CYP1A1 and CYP2D6 and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; outcome of a case-control study from Kashmir. India Mol Biol Res Commun. 2017;6(2):77–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padma R, Paulraj S, Sundaresan S. Squamous cell carcinoma of buccal mucosa: Prevalence of clinicopathological pattern and its implications for treatment. SRM J Res Dent Sci. 2017;8:9–13. doi: 10.4103/srmjrds.srmjrds_73_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rendic S. Summary of information on human CYP enzymes: human P450 metabolism data. Drug Metab Rev. 2002;34(1–2):83–448. doi: 10.1081/DMR-120001392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day IN. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for Mendelian randomization studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(4):505–514. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruwali M, Parmar D. Association of functionally important polymorphisms in cytochrome P450s with squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48(7):651–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SS, Koifman RJ, Ferreira RM, Diniz LF, Brennan P, Boffetta P, et al. SULT1A1 genetic polymorphisms and the association between smoking and oral cancer in a case-control study in Brazil. Front Oncol. 2012;2:183. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla P, Gupta D, Pant MC, Parmar D. CYP 2D6 polymorphism: a predictor of susceptibility and response to chemoradiotherapy in head and neck cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8(1):40–45. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.95172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya N, Inoue T, Narita S, Kumazawa T, Saito M, Obara T, et al. Drug-related genetic polymorphisms affecting adverse reactions to methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin in patients with urothelial cancer. J Urol. 2008;180(6):2389–2395. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin S, Almen MS, Zheleznyakova GY, Lundberg L, Zarei S, Castillo S, et al. Many obesity-associated SNPs strongly associate with DNA methylation changes at proximal promoters and enhancers. Genome Med. 2015;7:103. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0225-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio T, Arisawa H, Kohsaka K, Yasuda H. Identification of human drug-metabolizing enzymes involved in the metabolism of SNI-2011. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;24(11):1263–1266. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegman P, Elingarami S, Carstensen J, Stal O, Nordenskjold B, Wingren S. Genetic variants of CYP3A5, CYP2D6, SULT1A1, UGT2B15 and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/bcr1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138(1):103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhu X, Li Y, Zhu L, Li S, Zheng G, et al. Correlation of CpG island methylation of the cytochrome P450 2E1/2D6 genes with liver injury induced by anti-tuberculosis drugs: a nested case-control study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8):pii: E776. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13080776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SF, Liu JP, Chowbay B. Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 enzymes and its clinical impact. Drug Metab Rev. 2009;41(2):89–295. doi: 10.1080/03602530902843483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.