Highlights

-

•

The IGF1–PI3K pathway mediates exercise induced heart growth and protection.

-

•

Strategies to mimic the benefits of exercise on the heart are of substantial interest.

-

•

Characterizing animal models of altered cardiac PI3K activity can identify new drug targets for heart disease, and biomarkers which distinguish the healthy and diseased heart.

-

•

Therapies that increase PI3K activity may provide a promising approach to improve function in the failing heart.

-

•

Systemic therapies that reduce PI3K activity, such as some cancer agents, may lead to cardiotoxicity.

Keywords: Cardiac protection, Cardiotoxicity, Exercise, Heart failure, IGF1, PI3K, Therapies

Abstract

Heart failure represents the end point of a variety of cardiovascular diseases. It is a growing health burden and a leading cause of death worldwide. To date, limited treatment options exist for the treatment of heart failure, but exercise has been well-established as one of the few safe and effective interventions, leading to improved outcomes in patients. However, a lack of patient adherence remains a significant barrier in the implementation of exercise-based therapy for the treatment of heart failure. The insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1)–phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway has been recognized as perhaps the most critical pathway for mediating exercised-induced heart growth and protection. Here, we discuss how modulating activity of the IGF1–PI3K pathway may be a valuable approach for the development of therapies that mimic the protective effects of exercise on the heart. We outline some of the promising approaches being investigated that utilize PI3K-based therapy for the treatment of heart failure. We discuss the implications for cardiac pathology and cardiotoxicity that arise in a setting of reduced PI3K activity. Finally, we discuss the use of animal models of cardiac health and disease, and genetic mice with increased or decreased cardiac PI3K activity for the discovery of novel drug targets and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease.

1. Introduction and background

In this review, we have focused on a signaling cascade in the heart referred to as the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1)–phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, which plays an essential role in mediating the protective actions of regular physical activity or exercise on the heart. Regular exercise is a well-established and accessible intervention that has been demonstrated to provide benefit to multiple organ systems in settings of both health and disease.1 The benefits are well-established in a setting of cardiac health, in which exercise has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of future cardiac events or diseases and improve outcomes following a cardiac event or diagnosis.2,3 This is of particular interest given the rising prevalence of ischemic heart disease, which is currently the greatest burden of disease globally, both reducing quality of life and increasing overall mortality.4

Heart failure represents the end point of a variety of cardiovascular diseases and occurs when the heart is unable to supply adequate blood to the body. It is of particular relevance because of the high mortality rate (5-year mortality greater than 40% following initial diagnosis), high lifetime risk of acquisition (20%−45%),5 and the limited effectiveness of treatment options currently available. Aerobic exercise training has proven to be one of the few safe and effective interventions following a diagnosis of stable heart failure, with patients displaying improved cardiac function, aerobic capacity, and attenuation of abnormal cardiac remodeling following 3−6-month training programs.6,7 Both a lack of patient adherence and an inability to exercise due to loss of cardiac function from heart failure progression pose barriers for an individual to use exercise training as a method of treatment.

Understanding the key molecular pathways and mediators involved in exercise-induced heart protection is an exciting approach for treating heart failure. That being said, the development of an exercise-based therapy is far from a simple process. The cardioprotective effects of exercise reflect a complex and multifactorial web of neurohormonal, hemodynamic, molecular, and physiological changes that occur during and following physical activity, both in settings of acute and chronic exercise.1 Exercise in an acute setting activates the sympathetic nervous system and reduces parasympathetic activity. This, in conjunction with engagement of muscular and respiratory pumps, increases stroke volume and heart rate, which in turn leads to greater cardiac output to compensate for an increased demand for oxygen. Chronic or long-term exercise similarly leads to increased sympathetic activity, but additionally, the stimulation of various hormones and growth factors that facilitate the thickening and enlargement of the heart.1

2. Delineating key molecular pathways by understanding differences between the athlete's heart and the diseased heart

The athlete's heart is a term coined as far back as 1896 when Henschen8 observed cross-country skiers to have enlarged hearts. More recently, this phenomenon has been routinely observed in endurance athletes, who display an increase in heart mass while maintaining preserved or enhanced systolic and diastolic function.9, 10, 11 Exercise-induced heart growth, also known as physiological cardiac hypertrophy, is a compensatory mechanism that allows for the preservation or enhancement of cardiac function while facilitating the demand for greater cardiac output (increased workload).1 This type of growth is typically characterized by an increase in cardiomyocyte size, left ventricular chamber size, wall thickness, and mass. These adaptions function to normalize wall stress and tension in a coordinated manner.12,13

In contrast, pathological heart growth can occur in a setting of disease (pressure overload, myocardial infarction (MI), and cardiomyopathy) and can initially be characterized by thickening of ventricular walls and increased mass, but over time this can lead to cell death, fibrotic replacement, impaired cardiac function, and increased risk of heart failure.12,13 Of note, it has been documented that extreme amounts of high-intensity endurance exercise can lead to an increased risk of arrhythmia and/or sudden cardiac death.14 The risks from these extreme levels of exercise are distinct from the beneficial, normal levels of exercise that are discussed within this review. In a setting of moderate exercise, an increased risk of arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death is not apparent.

Our laboratory and others1 have investigated key mediators responsible for physiological hypertrophy by studying molecular changes in mouse models following chronic exercise (e.g., swim training) or genetic mouse models. Mice have proven to be a powerful tool to assess key mechanisms responsible for exercise-induced hypertrophy and protection because genes can be relatively easily manipulated to generate knock out and transgenic models, and mice develop significant physiological cardiac hypertrophy after as little as 3−4 weeks with swim training. Moreover, they breed rapidly, are inexpensive to house and functional changes can be assessed through a variety of exercise models (swim, treadmill, and voluntary running).15 Numerous molecular pathways have been shown to directly contribute or associate with aspects of physiological cardiac hypertrophy and protection. A comprehensive list is detailed in Bernardo et al.1 and includes IGF1–PI3K signaling, mediators downstream of vascular endothelial growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor, neuregulin 1, transcription factors and microRNAs (miRNAs). We have summarized work related to the IGF1–PI3K pathway and strategies for targeting this pathway in the failing heart.

3. The IGF1–PI3K signaling pathway: A key mediator of physiological hypertrophy and cardioprotection

Activation of the IGF1–PI3K pathway through physical activity has been well-established in playing an important and beneficial role in protecting the heart. However, exercise is an activity involving the whole body, and evidence has indicated that exercise also plays an important role in activation of the IGF1–PI3K pathway in both brain and skeletal muscle;14,16, 17, 18, 19, 20 the impact of exercise on this pathway in other tissue types is less clear.

In this review, we have focused on the IGF1–PI3K signaling pathway because, to date, this pathway is the most recognized and essential signaling pathway responsible for mediating physiological hypertrophy. Cardiac IGF1 formation has been demonstrated to be elevated in elite athletes (soccer players) with enlarged hearts following exercise training. It is postulated that, in response to increased stroke volume during exercise, cardiac myocytes undergo stretch, and IGF1 is released from cardiac myocytes in preference to other growth factors (angiotensin II and endothelin-1) which are released from myocytes in response to a chronic pathological stimuli.21 IGF1 binds to the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R), a plasma membrane receptor from the family of tyrosine kinases, and initiates the activation of 2 well-established, pro-hypertrophic canonical signaling pathways—the PI3K–protein kinase B (Akt) pathway and the extracellular signaling kinase pathway.22,23 Interestingly, in the adult mammalian heart, PI3K rather than extracellular signaling kinase, is the critical regulator of physiological heart growth.24 In this review, we primarily focus on the IGF1–PI3K pathway in the heart, with a particular emphasis on PI3K, providing an updated perspective on current knowledge, the development of therapeutic strategies for heart failure, biomarkers, and predictive tools for cardiotoxicity.

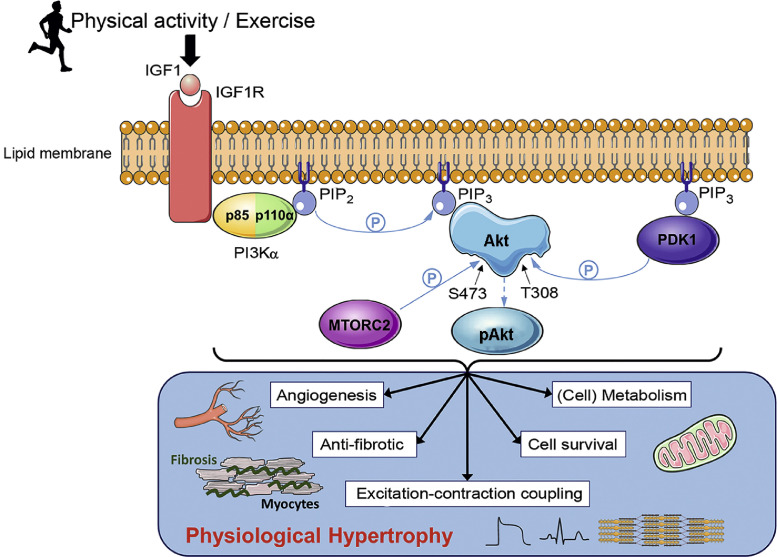

3.1. PI3K signaling

PI3Ks are a family of lipid and protein kinases expressed in all tissues and involved in a wide variety of processes such as cell survival, protein synthesis, cell motility, cell polarity, metabolism, and vesicle trafficking.25 Three classes of PI3Ks exist (I, II, and III) that function to catalyze the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositols to generate class dependent phosphoinositide forms with differing functions. Class I PI3Ks have been researched and understood in depth; there are 4 class I PI3Ks (p110α, β, δ, and γ) that can be further divided in subsets Class IA and IB. Class I PI3Ks function primarily to regulate cell growth, survival, proliferation, autophagy, and metabolism. Research into the function of Class II PI3Ks has been less studied, but 3 isoforms exist (PI3KC2α, PI3KC2β, and PI3KC2γ) with increasing evidence suggesting that they have distinct cellular roles, including cell proliferation, survival, and migration. A single Class III PI3K is conserved in eukaryotes, vacuolar protein sorting 34 acts to phosphorylate phosphatidylinositol to produce phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, which regulates autophagy and endocytic sorting.26, 27, 28 Class I PI3Ks are heterodimers consisting of a regulatory subunit and a catalytic subunit. Multiple isoforms or splice variants of each subunit exist which act to serve differing functions in different cell types.29 This review focuses on the p110α isoform of PI3K, a Class IA PI3K30 that is primarily activated by tyrosine kinase receptors, and expressed in cardiac myocytes to induce physiological myocyte growth. Activation of PI3K requires interaction of the p85 regulatory subunit with the p110α catalytic subunit, and this catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate. Following this conversion to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate, pleckstrin homology domain-containing proteins including Akt and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 are recruited to the plasma membrane. This recruitment leads to phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 phosphorylating Akt, which in turn allows for its activation and the triggering of subsequent downstream signaling pathways31 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram displaying the impact of physical activity or exercise on the IGF1–PI3K–Akt signaling pathway and the downstream physiological outcomes in the heart. Following exercise, IGF1 binds to the IGF1R embedded in the plasma membrane of cardiomyocytes, allowing for binding of p85, the regulatory subunit of PI3Kα. Once bound, p85 recruits p110α, the catalytic subunit of PI3Kα, forming the fully activated form of PI3Kα. Activated PI3Kα catalyzes the phosphorylation of PIP2 to PIP3, which recruits AKT and PDK1 to the plasma membrane. Binding of Akt to PIP3 causes a conformational change in Akt, exposing the phosphorylation sites S473 and T308. Phosphorylation of S473 by MTORC2 and T308 by PDK1 activates Akt allowing for numerous downstream protective physiological changes to the heart (via Akt dependent and Akt independent mechanisms). P within the blue circle signifies phosphorylation. Akt = protein kinase B; BTK = Bruton's tyrosine kinase; HER = human epidermal growth factor receptor; IGF1= insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R = insulin-like growth factor receptor; MTORC2 = mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2; NRG1= neuregulin 1; PDK1 = phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1; PIP2 = phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; PIP3 = phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; PI3K = phosphoinositide 3-kinase; S473 = serine 473; T308 = threonine 308.

3.2. Role of PI3K in the heart

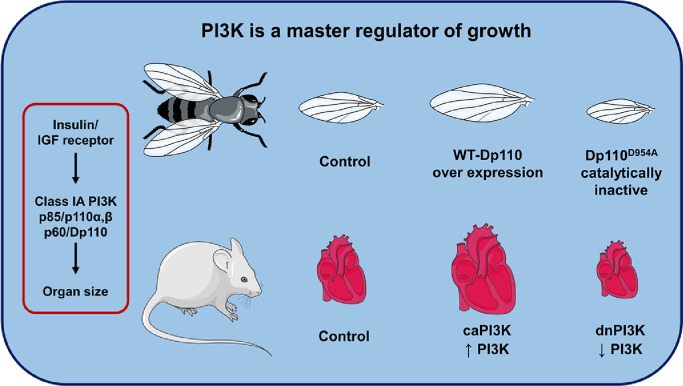

Initial interest in the role of PI3K in the heart arose from the previous observation that PI3K plays an essential role in regulating wing size in Drosophila. The insulin/IGF receptor/PI3K pathway is highly conserved across species. In Drosophila with overexpression of wildtype PI3K (Dp110), wing size was significantly larger than wing size from control flies. By contrast, expression of a catalytically inactive PI3K mutant (Dp110D954A) in Drosophila wing resulted in reduced wing size.32,33 The role of PI3K in the mammalian heart was first discovered through the characterization of transgenic mouse models with increased and decreased cardiac-specific PI3K(p110α) activity. This research demonstrated that PI3K is a critical mediator of physiological postnatal heart growth. Shioi et al.34 created a mouse model expressing a cardiac-specific constitutively activated mutant of PI3K (caPI3K), and a mouse model expressing a cardiac-specific dominant negative mutant of PI3K (dnPI3K). The caPI3K transgenic mice displayed increased cardiac PI3K activity, which corresponded to an increase in the size of all chambers and left ventricular (LV) wall thickness, and heart weight to body weight ratio. The dnPI3K transgenic mice had reduced PI3K activity and in turn a reduction in heart weight (Fig. 2). Neither of the models displayed any signs of heart failure following a year of observation.

Fig. 2.

PI3K is a master regulator of growth. Class IA PI3K(Dp110) overexpression in the wings of drosophila results in enlarged wings while over expression of a mutated inactive PI3K (Dp110D954A) results in smaller wings. Similarly, caPI3K in the hearts of mice results in enlarged hearts, while the presence of a truncated mutated dnPI3K with reduced PI3K activity results in smaller hearts. caPI3K = constitutive activation of PI3K; dnPI3K = dominant negative PI3K; IGF = insulin-like growth factor; PI3K = phosphoinositide 3-kinase; WT = wild type.

The role of PI3K(p110α) for the induction of exercise-induced physiological hypertrophy was later assessed by subjecting dnPI3K mice to chronic swim training. After 4 weeks of chronic swim training the hypertrophic response (heart weight to body weight ratio) of dnPI3K mice was significantly smaller than that of age- and weight-matched non-transgenic (Ntg) controls.35

In addition to its role in regulating heart growth, PI3K has also been demonstrated to mimic the cardioprotective properties of exercise. Exercise training in a genetic model of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) from 4 of weeks age, increased lifespan by ∼20% and ∼16% in male and female mice, respectively. By genetically crossing the DCM model with either dnPI3K or caPI3K mouse models, the impact of altered cardiac PI3K activity on lifespan was also assessed. DCM–caPI3K (increased PI3K) double transgenic mice (without exercise) showed an increase in longevity that was comparable to the increase in lifespan in the DCM model with exercise. In contrast, DCM–dnPI3K (reduced PI3K) mice displayed a drastic reduction in lifespan, highlighting the significance of both exercise and cardiac PI3K activity in the prevention of cardiac disease.36 These findings have been replicated in a variety of settings of cardiac stress, with the caPI3K transgenic mice displaying better cardiac function and less pathology following induction of pressure overload, MI, diabetic cardiomyopathy, and atrial fibrillation. Alternatively, the dnPI3K mice consistently display accelerated heart failure and other pathological complications in the above models of cardiac stress.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 These studies together highlight (1) the importance of PI3K in facilitating normal cardiac growth, (2) the role of PI3K in exercise-induced heart growth, and (3) the critical role of PI3K activity providing protection in a variety of settings of cardiac stress.

In keeping with its crucial role in exercise-induced cardiac growth, PI3K signaling and exercise both target and modulate many of the same cell types and cellular processes. These have been extensively described previously and include the regulation of cardiac myocyte growth, excitation and contraction coupling, vascular adaptions, cellular stress response, mitochondrial adaptations, and anti-fibrotic properties1 (Fig. 1).

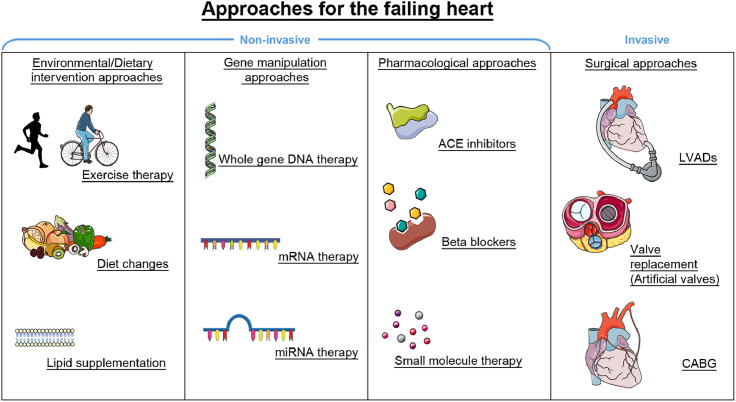

4. PI3K-based therapies as an approach for improving function of the failing heart—Overview

Heart transplantation availability is extremely limited, with as few as 4000−4500 heart transplantations occurring worldwide each year.42 Current approaches and strategies under investigation are broadly summarized in Fig. 3 and include (1) environmental and dietary approaches, (2) gene-based therapies (e.g., targeting DNA, mRNA, and miRNAs), (3) pharmacological approaches, and (4) surgical approaches (e.g., LV assist devices, valve replacement, and coronary artery bypass surgery). The majority of existing heart failure treatments primarily manage symptoms and delay disease progression, and exercise interventions are not always viable due to the progressive and debilitating nature of the disease.

Fig. 3.

A summary of current approaches for the failing heart and new promising approaches for improving function in the failing heart (e.g., gene therapy). Approaches are separated into 4 categories based on the type of intervention: environmental and dietary based interventions, approaches involving genetic manipulation, pharmacological interventions, and surgical interventions. Combining multiple approaches may be an optimal strategy to maximize therapeutic outcomes. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; LVAD = left ventricular assist device; miRNA = microRNA.

Given these cardioprotective benefits that PI3K has been demonstrated to provide a therapy that upregulates cardiac PI3K activity may provide a promising approach for improving heart function in individuals with heart failure. Our laboratory has a large interest in investigating the development of a PI3K based therapy as a non-surgical alternative for the treatment of the failing heart. Multiple approaches may be applicable in considering the use of a PI3K therapy, with differing tactics being tailored to particular pathological or clinical settings (Fig. 3). This is an important consideration given that a single approach is unlikely to be a one fix for all. Factors such as the method of administration (surgical vs. dietary), duration of therapeutic effect (short term vs. long term), and dosage of the PI3K therapy provided may differ depending on an individual's age, health status, prognosis, and particular cardiac disease being targeted. Moreover, combined therapeutic approaches to treat cardiovascular diseases are more frequently being utilized and are showing encouraging outcomes in recent times.43,44

Approaches our laboratory are investigating include PI3K therapies that utilize adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy, as well as the identification and utilization of mRNAs, miRNAs, small molecules, and lipids that differ between healthy and diseased hearts. Gene therapy is discussed in Section 5, and other approaches are discussed in Section 7.

5. Gene therapy as an approach for treating heart failure

Gene therapy involves the transfer of an isolated nucleic sequence from a foreign body to a host organism with the purpose of altering gene function and/or expression, and in turn, providing a therapeutic outcome.45 Numerous factors need to be taken into consideration to maximize clinical viability when developing a cardiac gene therapy. Namely, the choice of vector used to transfer the transgene, the method of delivering the vector to the heart, the vector's capacity to provide efficient transduction of the human heart, the therapeutic potential of the transgene of choice, and the cost/practicality of large-scale manufacturing.46

Modified viral vectors have been the primary choice of vectors used for the transfer of genetic material to date; more specifically, AAVs have been demonstrated to be a promising gene therapy vector for the treatment of heart failure with human clinical trials having been undertaken in recent times.47, 48, 49, 50, 51 AAVs are small, single stranded non-pathogenic viruses with the capacity to transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells. The interest in AAVs as a vector for the use in cardiac gene therapy arises from their high safety profile, non-pathogenicity (invoking a limited host immune response), and mediating long-term transgene expression that is reported to last several years in human trials.52 Moreover, multiple naturally occurring AAV serotypes such as AAV6 and AAV9 have been found to display cardiac-specific tropism, allowing for efficient transduction of cardiomyocytes while minimizing the delivery of transgenes to non-cardiac tissue or cells.46

Successful results from a multitude of AAV studies to treat heart failure in clinically relevant small and large animal models paved the way for the 1st AAV heart failure trial in human subjects: The Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID) trial. The CUPID trial attempted to increase expression of sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a) activity, which is reduced in the failing heart. Administration of AAV1–SERCA2a in a pilot study in 9 patients with heart failure displayed a positive safety profile and favorable outcomes including improved ejection fraction, end-systolic volume, and maximum rate of oxygen consumption (Table 1).49 This trial was replicated in a follow-up placebo controlled, Phase IIa CUPID trial of 39 patients, in which those that received a high dose of AAV1–SERCA2a (1 × 1013 DNase-resistant particles) demonstrated significantly improved LV end-systolic volume and maximum rate of oxygen consumption, as well as a decreased frequency of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular related hospitalizations (Table 1).50 Subsequently, a larger multinational, randomized, double-blinded placebo-controlled CUPID Phase IIb trial with 243 advanced heart failure patients was initiated. The Phase IIb trial did not demonstrate improvement in the primary or secondary end point of recurrent heart failure events or all-cause death, respectively (Table 1). The trial was prematurely terminated, but of importance, no signs of adverse safety outcomes were observed across all studies at any dose following administration of AAV1–SERCA2a.51 The outcome of the CUPID Phase IIb trial could not conclusively assess whether AAV1–SERCA2a was an appropriate gene target for the treatment of heart failure because efficiency of transduction was considered suboptimal. However, the results have been invaluable in informing future efforts of the use of AAV gene therapy for the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Table 1.

Outcomes from the AAV–SERCA2a CUPID trials.

| CUPID Trial 1/2 | CUPID Trial Phase IIa | CUPID Trial Phase IIb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (n) | 9 patients: Treated AAV1/SERCA2a (n = 9) |

39 patients: Placebo (n = 14) Treated AAV1/SERCA2a (n = 25) |

243 patients: Placebo (n = 122) AAV1/SERCA2a (n = 121) |

| Dose (vector genomes) | Low: 1.4 × 1011 Mid: 6 × 1011 High: 3 × 1012 |

Low: 6 × 1011 Middle: 3 × 1011 High: 1 × 1013 |

1 × 1013 |

| Positive safety profile | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Delay/reduction in clinical events | N/A | Yes | No |

| Improvement in NYHA functional class/quality of life | Yes | Yes | No |

| Improvement in 6-min walk test | Yes | Yes | No |

| Improvement in LV function/remodelling | Yes | Yes | No |

Abbreviations: AAV = adeno-associated virus; CUPID = The Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease; LV = left ventricular; NYHA = New York Heart Association; N/A = not applicable; SERCA2a = sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase.

The poor outcomes from the CUPID Phase IIb trial have not dampened efforts to utilize AAVs as a gene therapy vector, with over 200 clinical trials involving AAVs being registered at Clinicaltrials.gov as of June 2020, ten of which are categorized under the topic of heart disease. The aforementioned caPI3K transgene represents another gene target for the treatment of heart failure. Preliminary studies using an AAV6–caPI3K with a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in both healthy mice and models of cardiac pathology have demonstrated efficacy regarding its potential as a cardioprotective therapeutic agent.40 The AAV6 serotype in conjunction with use of a CMV promoter provided cardiac and skeletal muscle-specific transduction. Moreover, administration of AAV6–caPI3K-induced angiogenesis, physiological hypertrophy, and increased phosphorylation of Akt in the hearts of healthy mice. Similarly, promising results have been observed using AAV6–caPI3K in multiple models of established cardiac pathology. In a mouse model with established cardiac dysfunction due to pressure overload (transverse aortic constriction), AAV6–caPI3K was able to restore systolic function (fractional shortening) within 10 weeks of administration.40 AAV6–caPI3K administration also provided cardiac protection in mouse models with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. The type 1 diabetic model (low-dose streptozotocin) displayed diastolic dysfunction prior to AAV6–caPI3K, and this was attenuated within 6−8 weeks post-AAV. The type 2 model of diabetes (low-dose streptozotocin in combination with a high-fat diet) displayed systolic dysfunction prior to treatment, and AAV6–caPI3K increased systolic function within 8 weeks. Both type 1 and 2 diabetic models displayed cardiac fibrosis, and fibrosis was lower in AAV6–caPI3K treated mice compared to the corresponding diabetic control mice.41,53

Collectively, these findings have facilitated the continued optimization of AAV6–caPI3K as a gene therapy tool, and its transition into large animal models, a crucial steppingstone between the laboratory and the clinic.

In the process of the development and translation of a gene therapy such as AAV–caPI3K, from a laboratory to a clinical setting, 3 important considerations must be addressed: first, the cardiac specificity of the therapy (ensuring that the transgene is highly expressed in cardiac tissue while simultaneously not displaying expression in non-cardiac tissue); second, the feasibility of mass AAV production to ensure the therapy is financially viable as a treatment option for patients with heart failure; and third, demonstrating safety and efficacy in a large animal model of heart failure.

5.1. Cardiac specificity

Increased PI3K activity is protective and beneficial in cardiac tissue, but PI3K is well-known to be a regulator of tumor growth in other tissues in a variety of cancers.54,55 Cardiac myocytes within the adult heart have very little capacity to proliferate. Thus, changes in heart size and mass are typically a consequence of changes in cardiac myocyte size. In response to PI3K activation, cardiac myocytes enlarge and this results in physiological hypertrophy. However, in many forms of cancer, dysregulation and increased activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway in other cell types can lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation and growth, as seen in settings of tumorigenesis.56 Ensuring cardiac-specific gene transfer of a PI3K gene therapy is a crucial safety consideration for the prevention of undesirable side effects such as the development of cancer.

Another important consideration is efficient cardiac transduction. If a viral capsid is unable to efficiently transduce cardiac tissue, its capacity as a therapeutic agent is made redundant. One approach to address these concerns involves the selection of AAV serotypes that are naturally cardiotropic. Multiple studies have compared the effectiveness of the most well-established AAV serotypes (AAV1−9), and AAV6 and AAV9 have frequently demonstrated rapid and robust cardiotropic expression with substantial expression in the hearts relative to other organs.57, 58, 59, 60, 61 As described earlier, the AAV6–CMV–caPI3K vector displays transduction specific to cardiac and skeletal muscle.40 Further improvement to cardiac-specific transduction can be established using a cardiotropic AAV serotype in conjunction with a promoter that confers cardiomyocyte-specific gene expression such as a cardiac troponin T promoter. Prasad et al.62 compared transduction of AAV6 vectors harboring either a CMV or cardiac troponin T promoter with a luciferase reporter in a variety of tissue types in mice. Luciferase expression driven by the CMV promoter was comparable in the heart, skeletal muscle, and liver, whereas luciferase expression driven by the cardiac troponin T promoter was nearly 100-fold greater in the heart than all other tissue types assessed.62 In addition to promoter and serotype selection, further improvements to cardiac specificity may be made through the development of promoters that specifically target diseased tissue, development of chimeric AAV vectors through DNA shuffling, or the use of directed evolution to modify viral capsid sequences and select for cardiotropic variants.46

5.2. Feasibility of mass AAV production

The viability of mass scale production of AAV is another necessity to be considered in the process of clinical translation.63 The high global prevalence of heart failure together with the costs of mass producing larger yields of AAV for preclinical studies in large animals and for clinically relevant therapeutic interventions would come with a considerable price tag. The limited packaging capacity of AAV (∼5 kb), makes obtaining sufficient vector yields of larger genes (such as caPI3K) particularly challenging. Reducing the size of gene constructs is an approach to improving yield and in turn reducing cost. Furthermore, other promising approaches to improve large scale production of AAVs have involved modifications to the culture conditions for growing cells with plasmids used for chemical co-transfection of AAVs, as well the investigation of cell lines which display greater transfection efficiency and in turn improved AAV yields.64

5.3. Translation to large animal models

Assessment of efficacy and safety in large animal models is important for any new gene therapy approach. Sheep and pigs have typically been the model of choice after small animal studies. This primarily reflects the anatomical and physiological similarities shared between these large animals and humans, which differs in rodents. Moving from small animals to large animals invokes additional challenges, such as determining the optimal method to administer an AAV, identifying if either toxicity or efficacy vary in different animal models, and the optimal dose required to provide a therapeutic effect. This topic is covered in detail by Bass-Stringer et al.46

6. Cardiac pathology and cardiotoxicity in settings of reduced PI3K

The earlier part of this review has focused on enhancing PI3K activity in the heart to provide protection in settings of cardiac stress. However, a reduction in PI3K in the heart has the converse effect, that is, making the heart more susceptible to cardiac pathology and heart failure. Factors which can lead to reduced or defective PI3K signaling in the heart include physical inactivity, obesity, diabetes, aging, and drugs (e.g., anti-cancer drugs). The previously mentioned dnPI3K transgenic mouse model has been a valuable tool for understanding the impact of reduced cardiac PI3K activity in a variety of settings of cardiac pathologies. dnPI3K mice displayed cardiac dysfunction in response to pressure overload compared to Ntg controls. This was demonstrated through a significant reduction in fractional shortening, and a marked increase in systolic and diastolic LV dimensions following 1 week of ascending-aortic banding compared to Ntg-banded controls. The animals also displayed an increase in lung weight/body weight ratio, a marker of LV dysfunction.35,36 Similarly, in a setting of MI, dnPI3K mice also displayed reduced fractional shortening and increased chamber dimensions.38

PI3K activity has also been shown to affect the progression of heart failure in a setting of DCM. dnPI3K transgenic mice have been crossed with 2 different cardiac-specific transgenic mouse models of DCM to generate double transgenic mice (dnPI3K–DCM). In the first DCM model, due to very high expression of Cre-recombinase, the dnPI3K transgene drastically shortened life span (∼50%) in the dnPI3K–DCM compared to DCM transgenic mice. In a second model of DCM, due to over-expression of mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1), the dnPI3K–DCM transgenic mice displayed an accelerated heart failure phenotype including more cardiac dysfunction, greater atrial enlargement and cardiac fibrosis than DCM (Mst1) transgenic mice, and developed atrial fibrillation.36,37

In a setting of diabetes, dnPI3K mice have also been shown to develop an exaggerated cardiomyopathy phenotype compared to Ntg diabetic mice.39 Taken together, these studies demonstrate that a reduction in PI3K leads to accelerated cardiac pathology and heart failure in a variety of settings of pathological stress.

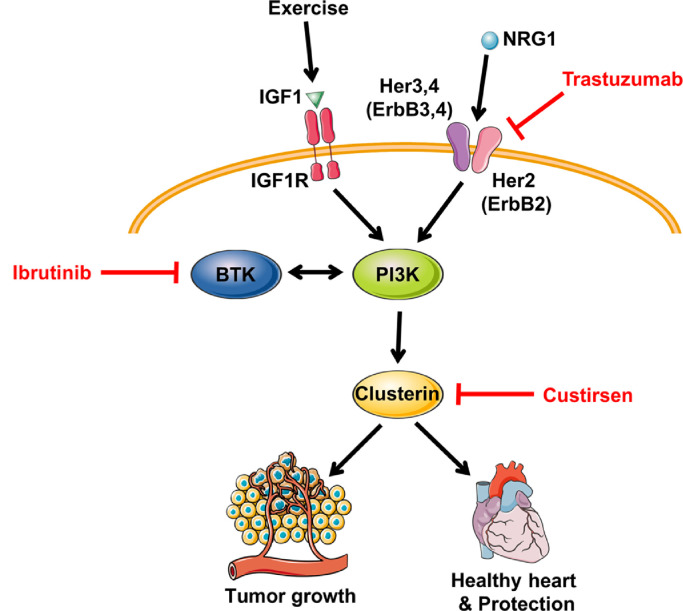

The IGF1–PI3K pathway is considered a master regulator of cancer in a variety of non-cardiac tissue types.56,65 Thus, extensive efforts have been devoted to developing agents that act to inhibit or modify components of the IGF1–PI3K pathway, and in turn improve survival rates for cancer patients. However, with improvements in survival from cancer, some patients are developing cardiac complications including heart failure and arrhythmias. Given the widespread pathological outcomes seen in mice with reduced PI3K activity, consideration should be taken for potential adverse effects due to cardiotoxicity that may arise when inhibiting this ubiquitously expressed pathway in an already compromised population. Kinase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer, such as trastuzumab,66 have been recognized to contribute to cardiac dysfunction.67 A Phase III randomized multicenter trial68 combined trastuzumab with anthracyclines and cyclophosphamide to treat human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer patients. Heart failure and cardiac dysfunction was reported in up to 27% of patients receiving the combined therapy. Comparatively, the group that received only anthracyclines and cyclophosphamide had an incident rate of 8%.68 A number of mechanisms have been implicated to explain trastuzumab cardiac toxicity but it is noteworthy that this drug also has the potential to inhibit PI3K signaling via HER2 (Fig 4).66,69

Fig. 4.

Anticancer therapeutics with the potential to inhibit the PI3Kα pathway. Trastuzumab binds to the extracellular domain of HER2 and triggers mechanisms to downregulate downstream activity. Ibrutinib inhibits BTK expression and is a known regulator of the PI3K–Akt pathway. Custirsen acts to silence clusterin, of which its expression has been correlated with PI3K activity, and may disrupt downstream processes. The mechanisms of anticancer therapies that suppress tumor growth by targeting the PI3K–Akt pathway may simultaneously contribute to an increased susceptibility for the development of cardiac pathologies. Red lines indicate interventions that act to silence, inhibit, or downregulate protein expression. Akt = protein kinase B; BTK = Bruton's tyrosine kinase; HER (ErbB) = human epidermal growth factor receptor; IGF1= insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R = insulin-like growth factor receptor; NRG1= neuregulin 1; PI3K = phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Modification of other proteins regulated by the IGF1–PI3K pathway are being targeted for the development of novel anticancer drugs. Clusterin has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various cancers, such as prostate cancers, breast cancers, and lung cancer,70,71 and has been a target of interest, with multiple recent clinical trials having focused on silencing clusterin with an antisense oligonucleotide (Custirsen) as a therapeutic intervention. We recently reported a potential role of clusterin in physiological cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac protection. Expression of clusterin was increased in hearts of caPI3K mice and decreased in hearts of dnPI3K mice. In addition, we identified increased secretion of clusterin in media from neonatal rat ventricular myocytes stimulated with IGF1.72 Given that a link exists between reduced PI3K activity and clusterin expression72 (Fig. 4), the possibility for the development of cardiac toxicity following its silencing should be considered.

Similarly, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor called ibrutinib is a targeted cancer therapy used for the treatment of many hematological cancers including chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Across multiple trials, 3.5%−6.5% of subjects receiving ibrutinib treatment developed atrial fibrillation.73 There is potential crosstalk between Bruton tyrosine kinase and the PI3K–Akt pathway,74 and thus, ibrutinib has the potential to interfere with cardioprotection (Fig. 4). Our laboratory has shown that mice with reduced PI3K activity display greater susceptibility to atrial fibrillation and that PI3K–Akt activity is reduced in human atrial appendages from patients with atrial fibrillation.37 Moreover, reduced PI3K–Akt expression has been observed following the exposure of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes to ibrutinib.73 These observations highlight the importance of taking caution when considering any intervention that may suppress the PI3K–Akt pathway in the heart. The impact of exercise on the IGF1–PI3K signaling pathway in non-cardiac tissue should also be considered when assessing potential toxicities of therapies that act to alter the expression or function of the IGF1–PI3K pathway, as exercise represents a systemic intervention, and has been demonstrated to play a role in activating the IGF1–PI3K pathway in brain and skeletal muscle tissue.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Crosstalk between skeletal muscle and other tissues with the heart has also emerged.1

7. Identifying molecular distinctions in the healthy and diseased heart—New drug targets and biomarkers

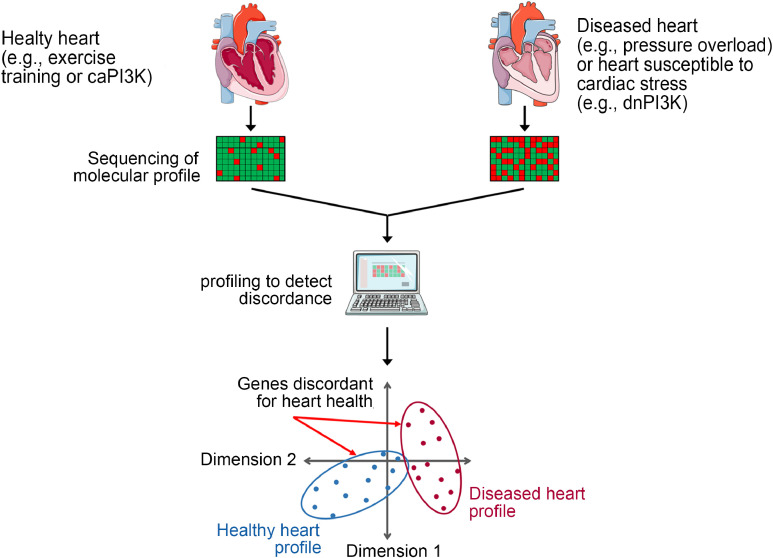

The physiological and pathological hypertrophic heart display distinct and differing functional, metabolic, structural, and molecular features. The use of surgical, genetic, and exercise models representing pathological or physiological cardiac remodeling, together with the profiling of genes, proteins, lipids, and metabolites, has become a valuable research tool to identify potential new drug targets and biomarkers which are distinct in the healthy and diseased heart (Fig. 5). A detailed overview of profiling studies has been summarized previously.1 This same approach can be used in genetic mouse models which are protected or more susceptible to cardiac stress (e.g., caPI3K and dnPI3K transgenic mice, respectively). Distinguishing a diseased or stress susceptible heart may provide opportunities to assess whether someone is more likely to develop more severe cardiac pathology in response to cardiac stress (e.g., hypertension) or a cancer therapy.

Fig. 5.

Identifying molecular distinctions between the healthy and diseased heart. A simplified pipeline demonstrating the process of using sequencing technologies to identify candidate therapeutics and biomarkers of cardiac health and disease. Tissue is collected, pooled, and processed from healthy and diseased hearts. A molecule of interest (e.g., DNA, RNA, protein, lipid) is sequenced and profiled. Expression is compared between groups to identify specific candidates that are discordant for cardiac health, or techniques such as principal component analysis can be used to identify global changes between groups. caPI3K = constitutive activation of PI3K; dnPI3K = dominant negative PI3K; PI3K = phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Our laboratory has undertaken gene-profiling studies to attempt to identify candidate therapeutic genes regulated by PI3K. Assessing the profiles of caPI3K, dnPI3K, and Ntg mice subjected to cardiac stress through MI was used to generate a list of genes that were differentially expressed based on PI3K activity.38 Correlating these differentially expressed genes with cardiac function (fractional shortening percentage) and in turn identifying those that are selectively expressed in the heart, provided a shortlist of candidate therapeutic targets. One of the top candidate genes was Acadm.

The protein product of Acadm is medium chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (MCAD), a protein that has not previously been linked with physiological hypertrophy and protection. The therapeutic potential of MCAD in the heart was examined by administering an AAV6 vector encoding MCAD to both healthy mice and mouse models of cardiac dysfunction.75 MCAD induced physiological hypertrophy in healthy mice and mitigated characteristics of cardiac remodeling in a setting of cardiac pathology due to pressure overload.75 This highlights the potential of how assessing differences in the healthy and diseased heart can identify candidates for novel therapies.

The same approach that led to the identification of Acadm was applied to identify miRNAs that are differentially regulated in caPI3K mice, dnPI3K mice, and Ntg mice. Numerous candidates were identified,38 and subsequently, silencing or inhibition of miR-34, miR-652, or miR-154 provided benefit when targeted in settings of cardiac pathology (MI and/or pressure overload).76, 77, 78

Our laboratory has also undertaken comprehensive profiling of the lipidome in models of physiological and pathological remodeling. As cardiac myocytes enlarge or change shape in response to a stimulus (e.g., cardiac stress such as hypertension or chronic exercise training), the plasma membrane which includes hundreds of lipid species, undergoes dramatic remodeling. Lipid profiling (>300 lipid species) demonstrated that lipid profiles differ substantially in models of physiological cardiac remodeling (swim training, caPI3K transgenic mice, and IGF1R transgenic mice), models of pathological remodeling (severe pressure overload due to transverse aortic constriction, a transgenic model of DCM, and mice with reduced cardiac PI3K activity and greater susceptibility to cardiac stress, i.e., dnPI3K transgenic).79,80 As an example, many sphingolipid species were decreased in the hearts of caPI3K mice and increased in the hearts of dnPI3K mice; by contrast, many phospholipids were increased in the hearts of caPI3K mice but decreased in dnPI3K mice.79 Dietary supplementation of lipid species that are depressed in the diseased heart and increased in the healthy heart may offer a non-invasive therapeutic approach for improving heart function (Fig. 3).

Microarray gene profiling and/or protein analyses in physiological models (IGF1R transgenic mice, PI3K transgenic mice, and exercise-trained mice) also led to the observation that heat shop protein 70 (Hsp70) expression is elevated in the heart with cardiac IGF1R–PI3K signaling and exercise training.24,40 Hsp70 plays a key role in the cellular stress response.1 Based on this work, we assessed the therapeutic potential of a small molecule which was a known co-inducer of Hsp70 in a mouse model with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. The small molecule (BGP-15) improved heart function, reduced arrhythmia and was associated with lower cardiac fibrosis. Unexpectedly, the small molecule appeared to provide benefit via phosphorylation of IGF1R, which was independent of Hsp70.81

8. Concluding remarks

The benefits of regular physical activity are well-known and represent an accessible intervention that can improve cardiac function and reverse cardiac remodeling in a setting of heart failure. However, patient adherence to exercise is a significant issue. Thus, alternative strategies for recapitulating some of the key benefits of exercise on the heart are of substantial interest. Characterizing mouse models with altered cardiac PI3K activity under basal and disease settings have provided an invaluable tool to identify molecular distinctions between the healthy and diseased heart because PI3K is a critical regulator of physiological cardiac hypertrophy but not pathological hypertrophy. This has allowed for the discovery of novel targets for the treatment of heart failure. Furthermore, the importance of PI3K activity for maintaining cardiac function should be taken into consideration when evaluating the viability of therapies that act to reduce activity of the IGF1–PI3K pathway, as these may cause cardiotoxicity in more vulnerable patients with other conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

Acknowledgments

All authors are supported by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. SBS is supported by a joint Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute–La Trobe University doctoral scholarship. JRM is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship (Grant No. 1078985).

Authors’ contributions

SBS and JRM drafted the manuscript; CMKT contributed to editing the paper. All authors contributed to the generation of figures. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Bernardo BC, Ooi JYY, Weeks KL, Patterson NL, McMullen JR. Understanding key mechanisms of exercise-induced cardiac protection to mitigate disease: Current knowledge and emerging concepts. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:419–475. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers J. Cardiology patient pages. Exercise and cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2003;107:e2–e5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048890.59383.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gielen S, Laughlin MH, O'Conner C, Duncker DJ. Exercise training in patients with heart disease: Review of beneficial effects and clinical recommendations. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy KS. Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 provides GPS for global health 2030. The Lancet. 2016;388:1448–1449. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31743-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannuzzi P, Temporelli PL, Corrà U, Tavazzi L, ELVD-CHF Study Group Antiremodeling effect of long-term exercise training in patients with stable chronic heart failure: Results of the Exercise in Left Ventricular Dysfunction and Chronic Heart Failure (ELVD-CHF) Trial. Circulation. 2003;108:554–559. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081780.38477.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisløff U, Støylen A, Loennechen JP, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: A randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115:3086–3094. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henschen S. Cross country skiing and ski racing: A medical sports study. (Skilanglauf und Skidwettlauf. Eine medzinische Sporstudie) Mit Med Klin Upsala. 1899;2:15–18. [in German] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pluim BM, Zwinderman AH, van der Laarse A, van der Wall EE. The athlete's heart. A meta-analysis of cardiac structure and function. Circulation. 2000;101:336–344. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whyte GP, George K, Nevill A, Shave R, Sharma S, McKenna WJ. Left ventricular morphology and function in female athletes: A meta-analysis. Int J Sports Med. 2004;25:380–383. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura T, Yamada Y, Kawai C. Echocardiographic evaluation of long-term effects of exercise on left ventricular hypertrophy and function in professional bicyclists. Circulation. 1980;61:832–840. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.4.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maillet M, van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD. Molecular basis of physiological heart growth: Fundamental concepts and new players. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernardo BC, Weeks KL, Pretorius L, McMullen JR. Molecular distinction between physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: Experimental findings and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;128:191–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eijsvogels TM, Fernandez AB, Thompson PD. Are there deleterious cardiac effects of acute and chronic endurance exercise. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:99–125. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole DC, Copp SW, Colburn TD, et al. Guidelines for animal exercise and training protocols for cardiovascular studies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318:H1100–H1138. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00697.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egerman MA, Glass DJ. Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:59–68. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.857291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferretti R, Moura EG, Dos Santos VC, et al. High-fat diet suppresses the positive effect of creatine supplementation on skeletal muscle function by reducing protein expression of IGF-PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barclay RD, Burd NA, Tyler C, Tillin NA, Mackenzie RW. The role of the IGF-1 signaling cascade in muscle protein synthesis and anabolic resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Front Nutr. 2019;6:146. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mysoet J, Canu MH, Cieniewski-Bernard C, Bastide B, Dupont E. Hypoactivity affects IGF-1 level and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in cerebral structures implied in motor control. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin JY, Kuo WW, Baskaran R, et al. Swimming exercise stimulates IGF1/PI3K/Akt and AMPK/SIRT1/PGC1alpha survival signaling to suppress apoptosis and inflammation in aging hippocampus. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:6852–6864. doi: 10.18632/aging.103046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neri Serneri GG, Boddi M, Modesti PA, et al. Increased cardiac sympathetic activity and insulin-like growth factor-I formation are associated with physiological hypertrophy in athletes. Circ Res. 2001;89:977–982. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troncoso R, Ibarra C, Vicencio JM, Jaimovich E, Lavandero S. New insights into IGF-1 signaling in the heart. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Wende AR, Sena S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor signaling is required for exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:2531–2543. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Huang WY, et al. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor induces physiological heart growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4782–4793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weeks KL, Bernardo BC, Ooi JYY, Patterson NL, McMullen JR. The IGF1-PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in mediating exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy and protection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1000:187–210. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4304-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:605–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulluni F, De Santis MC, Margaria JP, Martini M, Hirsch E. Class II PI3K functions in cell biology and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:339–359. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohashi Y, Tremel S, Williams RL. VPS34 complexes from a structural perspective. J Lipid Res. 2019;60:229–241. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R089490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jean S, Kiger AA. Classes of phosphoinositide 3-kinases at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:923–928. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawyer C, Sturge J, Bennett DC, et al. Regulation of breast cancer cell chemotaxis by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110δ. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1667–1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghigo A, Li M. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase: Friend and foe in cardiovascular disease. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:169. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leevers SJ, Weinkove D, MacDougall LK, Hafen E, Waterfield MD. The Drosophila phosphoinositide 3-kinase Dp110 promotes cell growth. EMBO J. 1996;15:6584–6594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinkove D, Neufeld TP, Twardzik T, Waterfield MD, Leevers SJ. Regulation of imaginal disc cell size, cell number and organ size by Drosophila class I(A) phosphoinositide 3-kinase and its adaptor. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shioi T, Kang PM, Douglas PS, et al. The conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway determines heart size in mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:2537–2548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Zhang L, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) plays a critical role for the induction of physiological, but not pathological, cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12355–12360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934654100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMullen JR, Amirahmadi F, Woodcock EA, et al. Protective effects of exercise and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) signaling in dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:612–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606663104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pretorius L, Du XJ, Woodcock EA, et al. Reduced phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) activation increases the susceptibility to atrial fibrillation. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:998–1009. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin RC, Weeks KL, Gao XM, et al. PI3K (p110 α) protects against myocardial infarction-induced heart failure: Identification of PI3K-regulated miRNA and mRNA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:724–732. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritchie RH, Love JE, Huynh K, et al. Enhanced phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110α) activity prevents diabetes-induced cardiomyopathy and superoxide generation in a mouse model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:3369–3381. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2720-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weeks KL, Gao X, Du XJ, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110α is a master regulator of exercise-induced cardioprotection and PI3K gene therapy rescues cardiac dysfunction. Circ Heart fail. 2012;5:523–534. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.966622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prakoso D, De Blasio MJ, Qin C, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) gene delivery limits diabetes-induced cardiac NADPH oxidase and cardiomyopathy in a mouse model with established diastolic dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017;131:1345–1360. doi: 10.1042/CS20170063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook JA, Shah KB, Quader MA, et al. The total artificial heart. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:2172–2180. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cuffe M. The patient with cardiovascular disease: Treatment strategies for preventing major events. Clin Cardiol. 2006;29 doi: 10.1002/clc.4960291403. II4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang D, Tai PWL, Gao G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:358–378. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bass-Stringer S, Bernardo BC, May CN, Thomas CJ, Weeks KL, McMullen JR. Adeno-associated virus gene therapy: Translational progress and future prospects in the treatment of heart failure. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27:1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clinical Trials US National Library of Medicine. Investigation of the Safety and Feasibility of AAV1/SERCA2a Gene Transfer in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure (SERCA-LVAD). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00534703. First posted: September 26, 2007.

- 48.Clinical Trials US National Library of Medicine. AAV1-CMV-Serca2a GENe Therapy Trial in Heart Failure (AGENTHF). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01966887. First posted: October 22, 2013.

- 49.Jaski BE, Jessup ML, Mancini DM, et al. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J Card Fail. 2009;15:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jessup M, Greenberg B, Mancini D, et al. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID): A phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:304–313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenberg B, Butler J, Felker GM, et al. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Patients with Cardiac Disease (CUPID 2): A randomised, multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1178–1186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wojno AP, Pierce EA, Bennett J. Seeing the light. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:175fs8. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prakoso D, De Blasio MJ, Tate M, et al. Gene therapy targeting cardiac phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) attenuates cardiac remodeling in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;318:H840–H852. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00632.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okkenhaug K, Graupera M, Vanhaesebroeck B. Targeting PI3K in cancer: impact on tumor cells, their protective stroma, angiogenesis, and immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1090–1105. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: Lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrd4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Nie J, Ma X, Wei Y, Peng Y, Wei X. Targeting PI3K in cancer: Mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:26. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0954-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Rengo G, Koch WJ, Rabinowitz JE. Comparative cardiac gene delivery of adeno-associated virus serotypes 1−9 reveals that AAV6 mediates the most efficient transduction in mouse heart. Clin Transl Sci. 2010;3:81–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palomeque J, Chemaly ER, Colosi P, et al. Efficiency of eight different AAV serotypes in transducing rat myocardium in vivo. Gene Ther. 2007;14:989–997. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Z, Zhu T, Qiao C, et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nbt1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao G, Bish LT, Sleeper MM, et al. Transendocardial delivery of AAV6 results in highly efficient and global cardiac gene transfer in rhesus macaques. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:979–984. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bish LT, Morine K, Sleeper MM, et al. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 9 provides global cardiac gene transfer superior to AAV1, AAV6, AAV7, and AAV8 in the mouse and rat. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:1359–1368. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prasad KM, Xu Y, Yang Z, Acton ST, French BA. Robust cardiomyocyte-specific gene expression following systemic injection of AAV: in vivo gene delivery follows a Poisson distribution. Gene Ther. 2011;18:43–52. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aucoin MG, Perrier M, Kamen AA. Critical assessment of current adeno-associated viral vector production and quantification methods. Biotechnol Adv. 2008;26:73–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kotin RM. Large-scale recombinant adeno-associated virus production. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:R2–R6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denduluri SK, Idowu O, Wang Z, et al. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling in tumorigenesis and the development of cancer drug resistance. Genes Dis. 2015;2:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dubská L, Andera L, Sheard MA. HER2 signaling downregulation by trastuzumab and suppression of the PI3K/Akt pathway: An unexpected effect on TRAIL-induced apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4149–4158. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeglinski M, Ludke A, Jassal DS, Singal PK. Trastuzumab-induced cardiac dysfunction: A “dual-hit”. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2011;16:70–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mohan N, Jiang J, Dokmanovic M, Wu WJ. Trastuzumab-mediated cardiotoxicity: Current understanding, challenges, and frontiers. Antib Ther. 2018;1:13–17. doi: 10.1093/abt/tby003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rizzi F, Bettuzzi S. The clusterin paradigm in prostate and breast carcinogenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R1–17. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Panico F, Rizzi F, Fabbri LM, Bettuzzi S, Luppi F. Clusterin (CLU) and lung cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2009;105:63–76. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)05004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bass-Stringer S, Ooi JYY, McMullen JR. Clusterin is regulated by IGF1-PI3K signaling in the heart: Implications for biomarker and drug target discovery, and cardiotoxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94:1763–1768. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McMullen JR, Boey EJ, Ooi JY, Seymour JF, Keating MJ, Tam CS. Ibrutinib increases the risk of atrial fibrillation, potentially through inhibition of cardiac PI3K-Akt signaling. Blood. 2014;124:3829–3830. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-604272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Efremov DG, Wiestner A, Laurenti L. Novel agents and emerging strategies for targeting the B-cell receptor pathway in CLL. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4 doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2012.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bernardo BC, Weeks KL, Pongsukwechkul T, et al. Gene delivery of medium chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase induces physiological cardiac hypertrophy and protects against pathological remodelling. Clin Sci (Lond) 2018;132:381–397. doi: 10.1042/CS20171269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bernardo BC, Gao XM, Winbanks CE, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of the miR-34 family attenuates pathological cardiac remodeling and improves heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17615–17620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206432109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bernardo BC, Nguyen SS, Gao XM, et al. Inhibition of miR-154 protects against cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis in a mouse model of pressure overload. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22442. doi: 10.1038/srep22442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bernardo BC, Nguyen SS, Winbanks CE, et al. Therapeutic silencing of miR-652 restores heart function and attenuates adverse remodeling in a setting of established pathological hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2014;28:5097–5110. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-253856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tham YK, Huynh K, Mellett NA, et al. Distinct lipidomic profiles in models of physiological and pathological cardiac remodeling, and potential therapeutic strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2018;1863:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tham YK, Bernardo BC, Huynh K, et al. Lipidomic profiles of the heart and circulation in response to exercise versus cardiac pathology: A resource of potential biomarkers and drug targets. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2757–2772. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sapra G, Tham YK, Cemerlang N, et al. The small-molecule BGP-15 protects against heart failure and atrial fibrillation in mice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5705. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.