Abstract

Context.

Slow codes, which occur when clinicians symbolically appear to conduct advanced cardiac life support but do not provide full resuscitation efforts, are ethically controversial.

Objectives.

To describe the use of slow codes in practice and their association with clinicians’ attitudes and moral distress.

Methods.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey at Rush University and University of Chicago in January 2020. Participants included physician trainees, attending physicians, nurses, and advanced practice providers who care for critically ill patients.

Results.

Of the 237 respondents to the survey (31% response rate, n = 237/753), almost half (48%) were internal medicine residents (46% response rate, n = 114/246). Over two-thirds of all respondents (69%) reported caring for a patient where a slow code was performed, with a mean of 1.3 slow codes (SD 1.7) occurring in the past year per participant. A narrow majority of respondents (52%) reported slow codes are ethical if the code is medically futile. Other respondents (46%) reported slow codes are not ethical, with 19% believing no code should be performed and 28% believing a full guideline consistent code should be performed. Most respondents reported moral distress when being required to run (75%), do chest compressions for (80%), or witness (78%) a cardiac resuscitation attempt they believe to be medically futile.

Conclusion.

Slow codes occur in practice, even though many clinicians ethically disagree with their use. The use of cardiac resuscitation attempts in medically futile situations can cause significant moral distress to medical professionals who agree or are forced to participate in them.

Keywords: Slow code, futility, intensive care unit, critical care, clinical medical ethics

Introduction

Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) is an urgent, algorithmic treatment for cardiac arrest designed to restore spontaneous circulation and restore as high a level of functioning as possible.1 In contrast, a “slow code” occurs when medical professionals symbolically appear to conduct ACLS but do not provide full resuscitation efforts, often because of the belief that ACLS is medically futile for the patient.2,3 This can take on many forms such as shortening the length of the attempt at cardiac resuscitation, moving in a slower fashion, or failing to provide all the mechanical and pharmacological interventions available.2,4 The goal of the slow code is not to restore circulation, but rather aims to function as a symbolic gesture to pretend some intervention is being done.5

While there are medical ethicists who take the stance performing slow codes are unethical, serve to break the trust between medical professionals and patient families, and cause needless suffering and pain to the patient,5,6 other argue that it can serve to support patient families when the family wants “to do everything” for their loved one.7 While this has not been confirmed, some believe slow codes are infrequent and used only when physicians feel they are legally or morally obligated to perform cardiac resuscitation on a patient whom they believe will be unlikely to benefit from it.3

Despite this vigorous ethical debate, there is no observational study involving physicians who care for critically ill patients documenting the frequency of slow codes in practice and evaluating how slow codes affect the medical professionals performing them. We aimed to describe the use of slow codes in practice, why slow codes are conducted, and how slow codes and medically futile attempts at cardiac resuscitation are associated with medical professionals’ attitudes and moral distress.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey at Rush University Medical Center and the University of Chicago Medicine in January 2020. Our primary aim was to describe the use of slow codes in practice. Our secondary aims were to describe both the association of slow codes and medically futile attempts at cardiac resuscitation with attitudes and moral distress of medical professionals and evaluate why slow codes occur. Slow codes were defined as a practice where physicians and nurses pretend to conduct ACLS but do not provide full resuscitation efforts with energy or enthusiasm because of the belief that the code is medically futile.2 Moral distress was defined as knowing the correct action to take but being constrained from executing that action.8

Participants and Recruitment

We sent this survey by email to participants using REDCap hosted at Rush University in January 2020.9,10 The survey was sent to all internal medicine residents, as well as to cardiology and pulmonology critical care fellows, attendings, nurses, and nurse practitioners. The sample size was determined by calculating all potential participants who were sent the survey as described above. We selected this population as they all care for patients in the medical or cardiac intensive care unit (ICU). We sent three emails requesting participants to complete the survey, and participants were entered into a raffle for a gift if they completed the survey. Slow codes occur when the resuscitation attempt is believed to be medically futile, which in practice is most likely to occur while a patient is in the ICU on maximum life support and the cause of the cardiac arrest is known and cannot be reversed.2 Other patient care locations, such as the emergency room where there may not be a chance to determine if an attempt at cardiac resuscitation is medically futile before the cardiac arrest occurs or the surgical ICU where recent surgery may play a factor in the cause and treatment of the cardiac arrest, were not included in this study. Both Rush University and the University of Chicago institutional review boards granted study exemption for this project.

Survey Design

The 28-item survey included multiple choice responses, five-point Likert scales, and free-response questions (Appendix I). We created the survey following a literature review and using survey design best practices as no previously validated survey existed for this study.11 A palliative medicine physician (G.M.P.) primarily developed the survey with essential contributions from a pulmonary critical care physician (W.F.P.) and two internal medicine residents (E.M.K. and A.K.). The survey provided a formal definition of slow codes to limit subjectivity regarding how a slow code is defined.2 It aimed to quantify the number of slow codes a participant has experienced, explore attitudes toward slow codes, and assess if moral distress occurs. We assessed participant demographics including age, years in practice, race and ethnicity, and religion and spirituality. Survey participants had the option to comment on why they believe slow codes occur via free text.

Statistical Analysis

We described continuous variables by mean and standard deviation and categorical variables by frequency of occurrence. We dichotomized Likert-type questions which were required to have high enough quantities per category to complete the statistical analysis; responses of “agree” or “strongly agree” and “sometimes,” “often,” or “always” were defined as in “agreement.” The χ2 statistic, Fisher’s exact test, one-way analysis of variance, and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were used to analyze Rush University and University of Chicago data to determine statistical significance using GraphPad Prism, version 8.0, and SAS software, version 9.4. All tests were two-sided and we used a P-value threshold for significance of <0.05. We used the framework approach for content analysis to assess qualitative responses.12

Results

The survey had an overall response rate of 31% (n = 237/753), with a 29% response rate at Rush University (n = 99/347) and a 34% response rate at the University of Chicago (n = 128/406). Internal medicine residents were the highest total proportion of survey respondents (48%), with total response rate of 46% (n = 114/246). Nurses were the next highest proportion of respondents (28%), followed by attending physicians (11%) and fellow physicians (10%). Most respondents were in practice less than 10 years (84%) and were younger than 30 (43%) or between 30 and 39 (45%) years of age. The majority of respondents were white (62%) and female (58%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics

| Study Population (N = 237) |

Rush University Medical Center (n = 99) |

University of Chicago Medicine (n = 138) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession | 0.004 | |||

| Advanced practice provider | 6 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (4%) | |

| Attending physician | 26 (11%) | 8 (8%) | 18 (13%) | |

| Fellow physician | 24 (10%) | 4 (4%) | 20 (14%) | |

| Nurse | 67 (28%) | 35 (35%) | 32 (23%) | |

| Resident physician | 114 (48.1%) | 52 (53%) | 62 (45%) | |

| Field of medicine | 0.252 | |||

| Cardiology | 30 (13%) | 8 (8%) | 22 (16%) | |

| Critical care | 73 (31%) | 35 (35%) | 38 (28%) | |

| Internal medicine | 129 (54%) | 54 (55%) | 75 (54%) | |

| Years in practice | 0.439 | |||

| 0–9 | 191 (84%) | 83 (85%) | 108 (83%) | |

| 10–19 | 22 (10%) | 10 (10%) | 12 (9%) | |

| 20–29 | 11 (5%) | 5 (5%) | 6 (5%) | |

| 30+ | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3%) | |

| Age | 0.085 | |||

| <30 | 100 (43%) | 51 (52%) | 49 (36%) | |

| 30–39 | 106 (45%) | 38 (39%) | 68 (50%) | |

| 40–49 | 19 (8%) | 7 (7%) | 12 (9%) | |

| 50+ | 9 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 7 (5%) | |

| Sex | 0.008 | |||

| Female | 138 (58%) | 68 (69%) | 70 (51%) | |

| Male | 96 (41%) | 31 (31%) | 65 (47%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.384 | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 46 (19%) | 18 (18%) | 28 (20%) | |

| Black/African-American | 10 (4%) | 5 (5%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 8 (6%) | |

| White | 148 (62%) | 65 (66%) | 83 (60%) | |

| Spiritual/religious preference | 0.258 | |||

| Buddhism | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Christian (Protestant) | 20 (8%) | 9 (9%) | 11 (8%) | |

| Christian (Roman Catholic) | 58 (24%) | 25 (25%) | 33 (24%) | |

| Christian (other denomination) | 25 (11%) | 13 (13%) | 12 (9%) | |

| Islam | 6 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Hinduism | 9 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Judaism | 18 (8%) | 6 (6%) | 12 (9%) | |

| Spiritual, but not religious | 25 (11%) | 12 (12%) | 13 (9%) | |

| None | 60 (25%) | 22 (22%) | 38 (28%) |

Slow Codes in Practice

In total, 69% of survey participants reported a slow code has been conducted on a patient they have cared for with a reported mean of 1.3 codes occurring over the past year per respondent (SD 1.7) (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1). Slow codes were reported with higher prevalence at University of Chicago (74%) when compared to Rush University (62%) (P = 0.044) (Supplementary Table 2). There was no statistical difference among profession, age, field of medicine, or years in practice in those who reported involvement with slow codes. Using the definition of slow code defined in the Methods section, the most common origin of a request for a slow code to be performed was the attending physician (84%), rather than a resident or fellow (43%), patient (11%), alternate decision maker (23%), or the survey respondent’s own decision (22%) (Supplementary Table 3). Slow codes were reported to most likely occur in the medical ICU (49%) versus the cardiac ICU (20%) (P = 0.030) (Supplementary Table 2).

Recommended length of cardiac resuscitation attempts for patients who do not obtain return of spontaneous circulation varied based upon whether the resuscitation attempt was presumed to be medically futile or not by the respondent. For resuscitation attempts in nonmedically futile situations, the recommended length was 36 minutes (SD 13) while for medically futile situations the recommended length was 21 minutes (SD 14) (P = <0.0001) (Supplementary Figures 2–4).

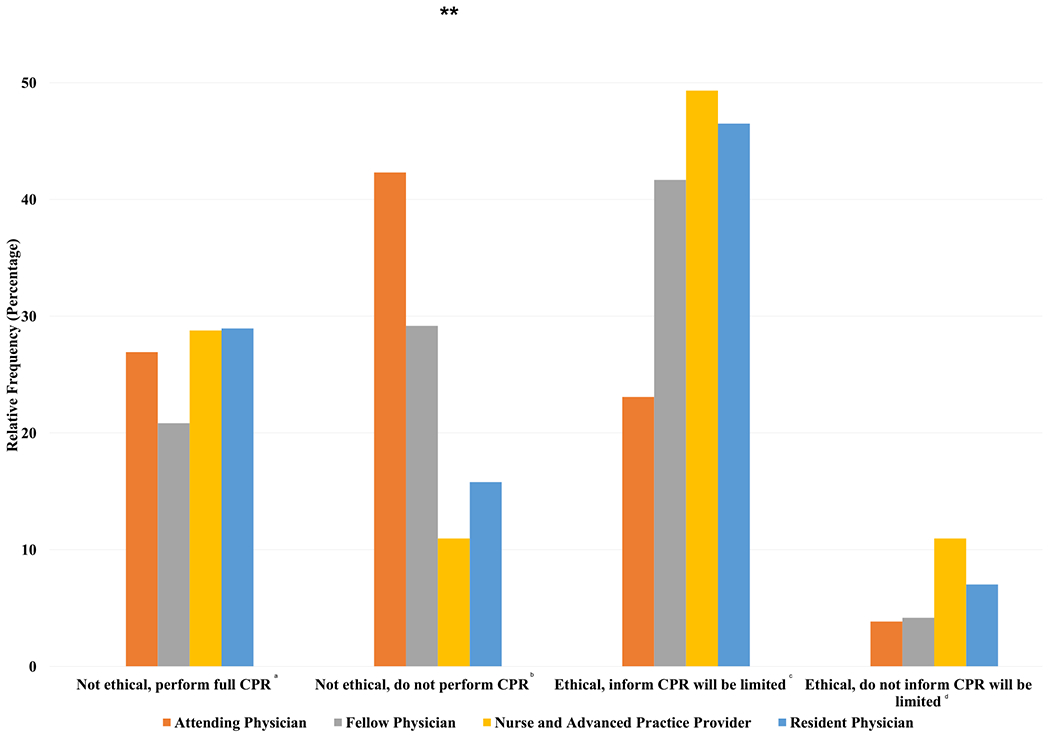

Ethics of Slow Codes

The majority of all respondents (52%) reported slow codes can be ethical if the code is considered to be medically futile. Of respondents reporting slow codes are ethical, 85% believe the patient or alternate decision maker must be informed a slow code will be conducted, and 15% believe they do not need to be informed. Less than half (46%) of respondents believe slow codes are not ethical. Of respondents reporting slow codes are not ethical, 40% believe no attempt at cardiac resuscitation should be performed, and 60% believe a full guideline consistent attempt at cardiac resuscitation should be performed. Attending physicians were more likely than other groups to believe slow codes are unethical and that ACLS should not be performed if the resuscitation attempt is considered medically futile (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Are slow codes ethical to conduct? Survey question: Imagine you are caring for a patient who is deteriorating rapidly in the intensive care unit in whom you believe CPR would be medically futile. Here medical futility is defined by 1) the inability of CPR to correct the underlying known cause and 2) the fact that CPR will most likely be unsuccessful, and even if ROSC is obtained, it will be short-lived. In this context do you believe that (choose one): Full survey responses: aA full, guidelines consistent code should be performed if the patient or alternate decision maker requests CPR. Performing a slow code for this patient is wrong. bPerforming a slow code in this scenario is wrong. No CPR should be performed for the patient, regardless of the wishes of the patient or alternate decision maker. cPerforming a slow code is ethically acceptable if the patient or alternate decision maker requests CPR. The alternate decision maker should be notified that the CPR duration will be limited. dPerforming a slow code is ethically acceptable if the patient or alternate decision maker requests CPR. The patient or alternate decision maker should NOT be notified that the CPR will be limited and allowed to believe the patient underwent full, guidelines consistent CPR. **P ≤ 0.01 among groups.

Attitudes Toward Slow Codes

Most respondents reported that attempting ACLS can be medically futile for some patients (95%) and that physicians should have the option not to offer cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (76%). The majority agree slow codes can be beneficial for families because it shows them everything was done to save the patient (52%), and that watching a resuscitation attempt can be beneficial for families (69%). About half (53%) believe that medical teams are obliged to code a patient if a family asks the team to “do everything” (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Attitudes toward slow codes and medically futile codes. Full survey questions: aI believe slow codes can be beneficial for patient families because it shows them everything was done to save the patient. bI believe watching a code can be beneficial for patient families as it allows them to witness the efforts of the medical team to help the patient. cIf a family asks that you “do everything” to save a patient, I believe we are obliged to code the patient. dI believe for some patients coding them is medically futile. eI believe physicians should have the option to not offer CPR for patients who it is not medically indicated or the harms outweigh the benefits. Survey responses of “agree” or “strongly agree” were defined as “agreement.” *P = ≤0.5 among groups. ***P ≤ 0.001 among groups.

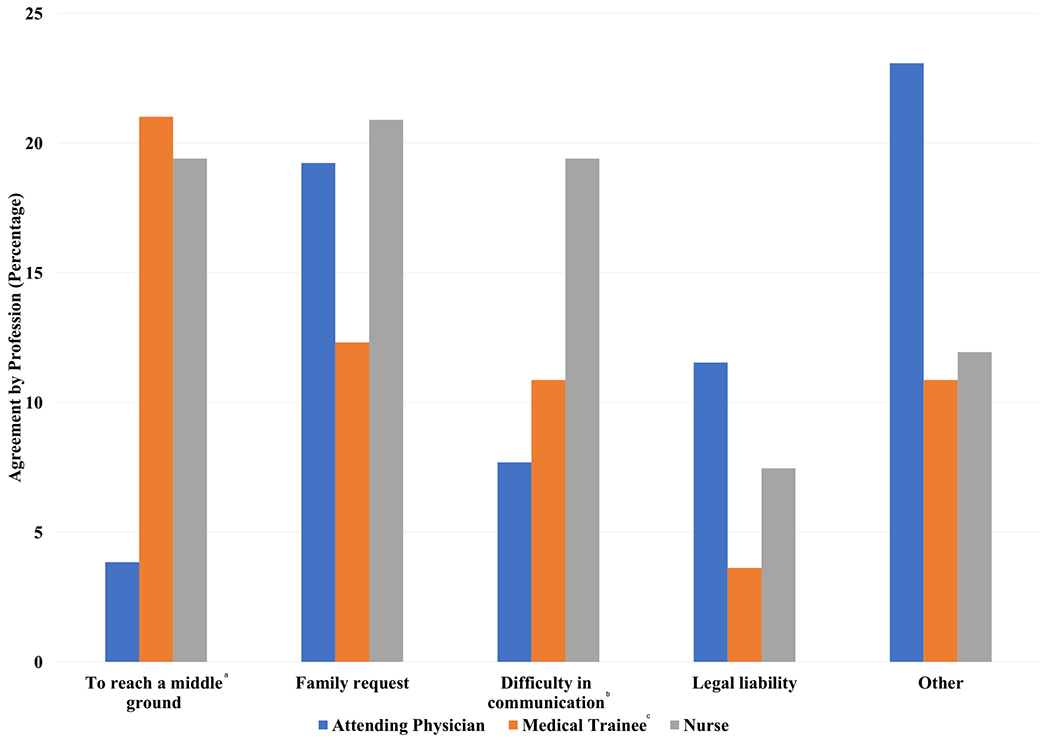

A total of 154 free text comments were submitted describing why slow codes occur in practice (65% of respondents, 154 responses/237 respondents). The most common reason identified was that slow codes serve as a middle ground between what providers and families think is best for the patient (28%). One participant wrote slow codes are performed when the “patient/POA wants everything done (full code) but health-care providers feel coding is futile, aggressive, pain-inducing, and cruel to the patient. It is a way for the providers to follow patient/POA wishes without being cruel to the patient.” Family request (25%), poor communication (20%), legal liability (9%), and preserving trust (1%) were other responses given (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Why do slow codes occur? aTo reach a middle group among physician, patient and family preferences. bDifficulty in communication between medical professionals, patients and families. cMedical trainees includes fellow physicians and resident physicians.

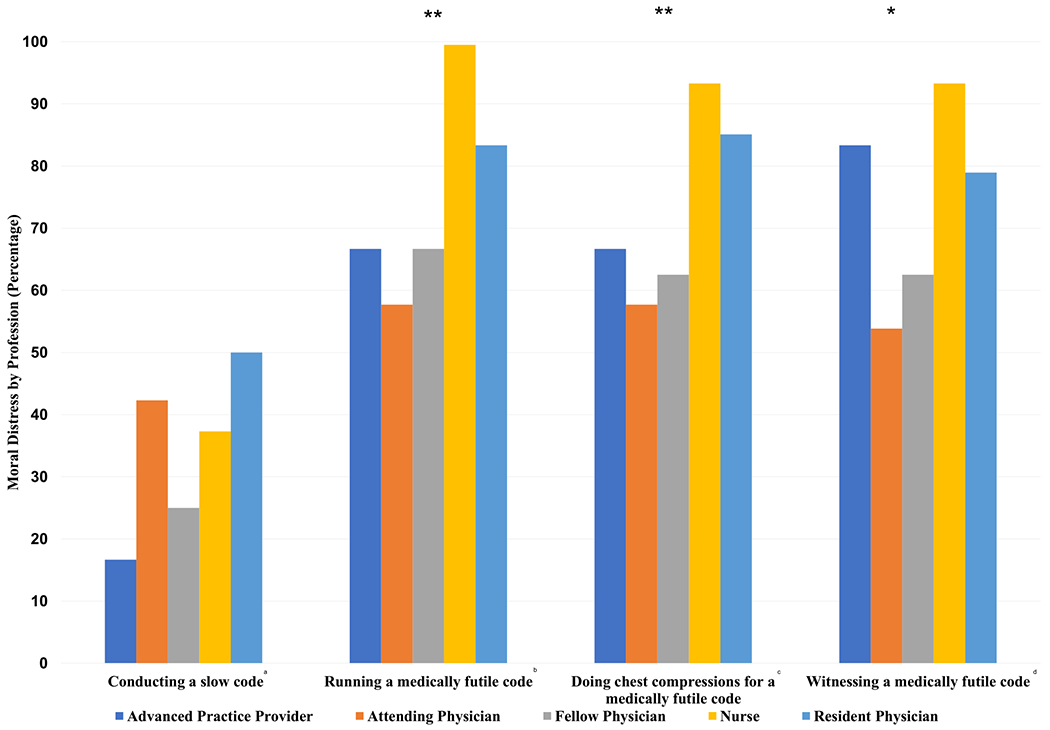

Moral Distress

Respondents reported moral distress associated with cardiac resuscitation attempts that are believed to be medically futile. Many respondents reported moral distress when required to run a cardiac resuscitation attempt (75%), do chest compressions (80%), or witness a resuscitation attempt (78%) when they believe the attempt is medically futile. Attending physicians (58%) were much less likely than nurses (87%) and medical residents (83%) to express symptoms of moral distress when required to run a cardiac resuscitation attempt for a patient when it is believed to be medically futile (P = 0.009). Attending physicians (54%) were also less likely than nurses (93%) and medical residents (79%) to express symptoms of moral distress when witnessing a resuscitation attempt when it is believed to be medically futile (P = 0.023) (Figure 4). Moral distress when required to run a resuscitation attempt that is believed to be medically futile was higher in participants with less than 10 years of experience (83%) versus those with 10-19 years of experience (55%) (P = 0.016). Higher percentages of Black/African-American (70%) and Hispanic/Latino (78%) respondents expressed moral distress at watching a resuscitation attempt when it is believed to be medically futile when compared to White (39%) respondents (P = 0.005).

Fig. 4.

Moral distress, slow codes, and medically futile codes. Survey question: How often do you experience moral distress from the following situations? Full survey questions: aBeing told to conduct a slow code. bBeing required to run a code when you believe it is medically futile. cBeing required to do chest compressions on a patient when you believe it is medically futile. dBeing required to witness a code when you believe it is medically futile. Survey responses of “sometimes,” “often,” or “always” were defined as in “agreement.” *P = ≤0.5 among groups. **P ≤ 0.01 among groups.

Discussion

Slow codes occur in medical practice with over two-thirds of respondents reporting a patient they have cared for has undergone a slow code. Although a narrow majority of respondents agree slow codes can be ethical to perform, there is a significant minority that disagree with their use. Most respondents report significant moral distress when having to participate in cardiac resuscitation attempts that are believed to be medically futile. The reasons given for why slow codes occur varied, with the most common response that they are a compromise between what the medical team and family believe is best for the patient.

Although there was previous belief that slow codes are infrequent in practice,3 this study found at two large academic medical centers in Chicago, 69% of participants have had at least one patient they have cared for receive a slow code with a reported average of 1.3 slow codes per year per survey participant. This finding is consistent with a previous study in which more than two-thirds of surveyed nurses reported a slow code was conducted on their unit,4 These results suggest slow codes are not rare and may weigh heavily on the minds of many medical professionals working in United States ICUs.

Proponents of slow codes argue that the procedure is ethical to perform as it helps the family cope with the patient’s death and allows them to believe everything was done to save the patient.7 This is supported by our findings that the most frequent response for why slow codes occur are that it serves as a middle ground between what clinicians and families believe is best for the patient. Although benefit for families may be true in some cases, the primary duty of clinicians and nurses should be to care for the patient and alleviate suffering.13 It is possible some patients prior to their death may consent to having a slow code performed after their death as a way to help their families cope; however, even in this situation the ethics of slow codes are still questionable as this medical procedure is done to the patient without the intent to improve the patient’s health.

Paradoxically, the majority of providers that believe slow codes are ethical also think that the family must be informed that ACLS will be limited. This would undermine the central justification for running a slow code, shattering the illusion that the performance represents the ultimate heroic gesture. It appears that few providers are willing to actively deceive the patient’s family in order to achieve the theoretical benefits of a slow code.

Opponents of slow codes argue that the procedure is unethical because it does not honor core principles of clinical medical ethics including providing benefit for the patient and preventing patient harm.2,14 During slow codes, the patient undergoes an aggressive procedure with lack of intent to improve the patient’s overall condition. Participants in slow codes do not provide full resuscitation efforts with energy or enthusiasm consistent with ACLS guidelines and the length of these codes may be shorter in duration than normal cardiac resuscitation attempts.2 Shortened length of cardiac resuscitation attempts is supported by our results in which respondents reported recommended length of resuscitation attempt to be 15 minutes less on average if the attempt is considered medically futile. This is concerning given that predicted survival outcomes are increased with longer duration of CPR.15,16

There is no current consensus regarding whether slow codes are ethical in medical practice.2,6,7,17–19 Our data show survey participants vary widely regarding whether they believe slow codes are ethical to conduct. When evaluating the participants who believed slow codes to be ethical to perform, a minority believed it is permissible to perform the slow code and not inform family that a slow code is being done. This is concerning as transparency and honesty, which are essential in patient care, are not honored.2 Our study found that of those who believe slow codes are unethical, the alternative to a slow code varied with some believing a full guideline consistent cardiac resuscitation attempt should be performed while others believed no resuscitation attempt should be performed.

One alternative to use of slow codes is not offering ACLS when it will not medically benefit the patient by using a unilateral DNR order.20,21 Over three-fourths of survey participants believe physicians should have the option to not offer CPR if a patient will not benefit from it; however half believe physicians are obliged to perform it if a family asks them to “do everything,” possibly related to concern for legal liability if they do not perform a code.22 Although unilateral DNR orders are used at some hospitals in the United States, there is no current consensus regarding whether these orders are appropriate to use when the patient or family requests CPR, which is supported by our results.23–25

While medical professionals may have good intentions for performing slow codes, this survey found slow codes are not without harm. A slow code, while less aggressive and invasive than a full cardiac resuscitation attempt, is still highly invasive and traumatic to the patient and medical professionals participating in the resuscitation attempt except without the justification that its intention is to bring the patient back to life.6 Our results suggest slow codes contribute to the harm of medical professionals with high levels of moral distress reported by medical professionals who perform slow codes. Moral distress often occurs when medical professionals are forced to execute and witness an act that is believed to be unethical.26 Our findings indicate even respondents who believe slow codes are ethical experience moral distress when a resuscitation attempt is thought to be medically futile. This suggests other factors, such as the aggressive and traumatic nature of ACLS, may also contribute to moral distress.

Moral distress is known to contribute to both physician and nurse burnout and job loss, and can negatively impact the quality of care provided to patients.27–33 In our survey, reported moral distress varied with professionals younger in age and those with less experience having the highest levels of moral distress. It is possible lower levels of moral distress in more experienced professionals may be related to emotional blunting due to repeated exposures to slow codes.34 It may also be explained by medical professionals with higher levels of distress choosing to leave the critical care setting as their career progresses. Higher levels of moral distress were reported by participants who are more likely to participate in a slow code, such as nurses and medical trainees, when compared to attending physicians who most often make the decision for a slow code that others are required to execute. In addition, differences in physician and nurse professional obligations regarding care in medically futile situations are likely associated with lower moral distress rates seen in attending physicians. The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics states physicians are not obligated to provide care that they determine is medically inappropriate, while nurses need to act within standards of practice and execute a physician order otherwise are at risk of losing their license to work as a nurse.13,35,36

Limitations

This study is limited by the low overall survey completion rate; however, a high total number of 237 participants were able to complete the study. There may be responder bias as participants who completed the survey may be more likely to have experienced a slow code, increasing their interest in completing the survey. It is also possible some potential survey participants were less likely to complete this survey due to not wanting to address this potentially distressing topic. This cross-sectional survey may not be generalizable to medical professionals in other US states or internationally as it evaluated two urban academic medical centers in Chicago. Hospitals in other states or internationally may have different policies regarding CPR in medially futile situations that may significantly alter their rate of performance of slow codes in practice. The findings between these two independent medical centers were quite similar, however, providing some support that these data may be similar at other institutions. Another limitation is recall bias as we asked survey participants to report experiences with slow codes and moral distress that had occurred in the past. It is possible survey participants had different viewpoints on the definition of a slow code or moral distress which may have impacted their responses to the survey questions. This limitation on different viewpoints on slow codes is minimized; however, as we provided all participants with a formal definition of a slow code at the beginning of the survey. Although this survey was assessed by multiple clinicians for readability and content prior to sending to survey participants, no official pilot study was done which is another limitation. Finally, we did not correct for multiple comparisons when testing among provider group differences in responses to survey questions, so significant differences should be considered exploratory.

Conclusions

Slow codes occur in practice, even though many medical professionals ethically disagree with their use. The use of cardiac resuscitation attempts in medically futile situations can cause significant moral distress to medical professionals who agree or are forced to participate in them.

Supplementary Material

Key Message.

This two-center cross-sectional study shows slow codes occur in practice, even though many clinicians ethically disagree with their use. The use of cardiac resuscitation attempts in medically futile situations can cause significant moral distress to medical professionals who agree or are forced to participate in them.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

William Parker is supported by K08 HL150291. All other coauthors have no disclosures to report. The authors are grateful for the support of internal medicine residents, and critical care and cardiology fellows, attendings, nurses, and advanced practice providers at Rush University and the University of Chicago for their participation in this project. They are also thankful for the assistance of Pankaja Desai, PhD, for assistance reviewing the survey structure and Yanyu Zhang, MS, MBA, and Todd Beck, MS, for helping with sections of the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2015;132:S315–S367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. Rush University (RSH) —Chicago, IL: [Internet]. Available from https://i-share-rsh.primo.exlibrisgroup.com. Accessed September 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DePalma JA, Ozanich E, Miller S, Yancich LM. “Slow” code: perspectives of a physician and critical care nurse. Crit Care Nurs Q 1999;22:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz FD, Sharfi R, Kaufman N, Einav S. Perceptions of slow codes by nurses working on internal medicine wards. Nurs Ethics 2019;26:1734–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zucker A Law and ethics. Death Stud 2004;28:181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazelle G The slow code–should anyone rush to its defense? N Engl J Med 1998;338:467–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lantos JD, Meadow WL. Should the “slow code” be resuscitated? Am J Bioeth 2011;11:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jameton A Nursing practice: the ethical Issues [Internet]. Available from https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/800986. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- 9.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artino AR, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE Guide No. 87. Med Teach 2014;36:463–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf [Internet]. Available from https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2020.

- 14.Beauchamp TL. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013:459. xvi+. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley SM, Liu W, Chan PS, et al. Duration of resuscitation efforts for in-hospital cardiac arrest by predicted outcomes: Insights from Get with the Guidelines - Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2017;113:128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberger ZD, Chan PS, Berg RA, et al. Duration of resuscitation efforts and survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study. Lancet 2012;380:1473–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladd RE, Forman EN. Why not a transparent slow code? Am J Bioeth 2011;11:29–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forman EN, Ladd RE. Why not a slow code? AMA J Ethics 2012;14:759–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meadow W, Lantos J. Re-animating the ‘slow code’. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:1077–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casarett D, Siegler M. Unilateral do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders and ethics consultation: a case series. Crit Care Med 1999;27:1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson EM, Cadge W, Zollfrank AA, Cremens MC, Courtwright AM. After the DNR: Surrogates who Persist in requesting cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Hastings Cent Rep 2017;47:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georgiou L, Georgiou A. A critical review of the factors leading to cardiopulmonary resuscitation as the default position of hospitalized patients in the USA regardless of severity of illness. Int J Emerg Med 2019;12:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putman MS, D’Alessandro A, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. Unilateral do not resuscitate orders: physician attitudes and practices. Chest 2017;152:224–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The cardiopulmonary resuscitation-not-indicated order: futility Revisited | Annals of internal medicine [Internet]. Available from . Accessed September 27, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Helft PR, Siegler M, Lantos J. The Rise and Fall of the futility Movement. New Engl J Med 2000;343:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral Injury not burnout. Fed Pract 2019;36:400–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sajjadi S, Norena M, Wong H, Dodek P. Moral distress and burnout in internal medicine residents. Can Med Educ J 2017;8:e36–e43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fumis RRL, Junqueira Amarante GA, de Fátima Nascimento A, Vieira JM Jr. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care 2017;7:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh Y, Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: a quantitative literature review. Nurs Ethics 2015;22:15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin CL, Saylor R, Finley PJ. Moral distress in physicians and nurses: impact on professional quality of life and turnover. Psychol Trauma 2017;9:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dzeng E, Wachter RM. Ethics in Conflict: moral distress as a Root cause of burnout. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35: 409–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and Self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colville GA, Smith JG, Brierley J, et al. Coping with staff burnout and work-related Posttraumatic stress in intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:e267–e273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Austen L Increasing emotional support for healthcare workers can rebalance clinical detachment and empathy. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:376–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joint Committee on Administrative Rules. Administrative code [Internet]. Gen Assembly’s Ill Administrative Code; 2015. Available from https://www.ilga.gov/commission/jcar/admincode/068/068013000A00900R.html. Accessed October 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buppert C Is a nurse obligated to perform CPR? Medscape [Internet]. Available from https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/781098. Accessed October 8, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.