Abstract

Characterization of the subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) promoter of many plant viruses is important to understand the expression of downstream genes and also to configure their genome into a suitable virus gene-vector system. Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus (CGMMV, genus Tobamovirus) is one of the RNA viruses, which is extensively being exploited as the suitable gene silencing and protein expression vector. Even though, characters of the sgRNA promoters (SGPs) of CGMMV are yet to be addressed. In the present study, we predicted the SGP for the movement protein (MP) and coat protein (CP) of CGMMV. Further, we identified the key regulatory elements in the SGP regions of MP and CP, and their interactions with the core RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain of CGMMV was deciphered. The modeled structure of core RdRp contains two palm (1–41 aa, and 63–109 aa), one finger (42–62 aa) subdomains with three conserved RdRp motifs that played important role in binding to the SGP nucleic acids. RdRp strongly preferred the double helix form of the stem region in the stem and loop (SL) structures, and the internal bulge elements. In MP-SGP, a total of six elements was identified; of them, the affinity of binding to − 26 nt to − 17 nt site (CGCGGAAAAG) was higher through the formation of strong hydrogen bonds with LYS16, TYR17, LYS19, SER20, etc. of the motif A in the palm subdomain of RdRp. Similar strong interactions were noticed in the internal bulge (CAACUUU) located at + 33 to + 39 nt adjacent to the translation start site (TLSS) (+ 1). These could be proposed as the putative core promoter elements in MP-SGP. Likewise, total five elements were predicted within − 114 nt to + 144 nt region of CP-SGP with respect to CP-TLSS. Of them, RdRp preferred to bind at the small hairpin located at − 60 nt to − 43 nt (UUGGAGGUUUAGCCUCCA) in the upstream region, and at the complex duplex structure spanning between + 99 and + 114 nt in the downstream region, thus indicating the distribution of core promoter within − 60 nt to + 114 nt region of CP-SGP with respect to TLSS (+ 1) of the CP; whereas, the − 114 nt to + 144 nt region of CP-SGP might be necessary for the full activity of the CP-SGP. Our in silico prediction certifies the gravity of these nucleotide stretches as the RNA regulatory elements and identifies their potentiality for binding with of palm and finger sub-domain of RdRp. Identification of such elements will be helpful to anticipate the critical length of the SGPs. Our finding will not only be helpful to delineate the SGPs of CGMMV but also their subsequent application in the efficient construction of virus gene-vector for the expression of foreign protein in plant.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13337-020-00640-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: CGMMV, Tobamovirus, sgRNA promoters, Regulatory elements, RdRp, In-silico

Introduction

The plant RNA viruses are equipped with various unique translational strategies, viz., production of subgenomic RNAs (sgRNAs) and/or polycistronic RNA, a read-through of leaky termination codon, frameshifting in the genome, etc. for their efficient gene expression in the diverse host. Of them, the sgRNA production is common to almost all plant positive-stranded (+) RNA viruses possessing mono-/bi-/tri-partite genome(s). The sgRNAs are co-terminal at either 3′ or 5’ end of the genomic RNA (gRNA) and can be synthesized through internal initiation from the subgenomic promoter or premature termination of negative-strand synthesis at a specific regulatory (stop) signal [28, 39]. In construct, some sgRNAs having 5′ ladder with 3′ terminal sequences are synthesized by copying the 3′ end of the gRNA (-) strand RNA followed by a discontinuous transcription step and switching of 5′ leader sequence. This 5′ leader sequence becomes the anti-leader in its (-)-strand form and serves as the replicase binding site for sgRNA replication [14, 38]. Mostly, sgRNA contains only one open reading frame (ORF), but sometimes multiple with rare exception [6]. Typically, sgRNAs are messenger RNA types and translated into proteins for the differential expression of specific viral genes in different temporal scales. Sometimes, their quantitative expression is much higher in comparison to the other viral genes; thus, it could be exploited for the heterologous expression of foreign proteins in plant.

The translational efficiency of the sgRNAs is largely regulated by some cis-regulatory elements located within a specialized region within the genome, such as the subgenomic promoter (SGP). SGP comprises of proximal ‘core’ promoter and distal ‘full’ promoter. The core promoter sequence which is the site for strong binding of the basic transcriptional machinery including RNA polymerase is necessary for maintaining the basic level of expression. Whereas, the distal ‘full’ promoter sequence is essential for the binding of other specific trans-acting factors along with RNA polymerase to achieve higher level expression. Other than these promoter sequences, it also contains some enhancers, spacer elements [13]. The synergistic action of such elements is the key to maximize gene expression. In plant viruses, the subgenomic promoter (SGP) regions are located either upstream or downstream of the transcription start site (TSS) or maybe overlapping in both. The physical characterization of such regions is crucial for utilizing them in heterologous protein expression via virus-based vectors. So far, the physical map of the SGP region is identified in brome mosaic virus (BMV) [11, 48], cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) [3], tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) [9], turnip yellow mosaic virus [36], etc. In the case of BMV, the SGP for sgRNA4 (encoding CP) is primarily mapped within the sequence from − 95 nt to + 16 nt with respect to TSS (+ 1). The BMV CP-SGP region is composed of an enhancer element which localized between − 95 nt and − 20 nt and enriched in AU sequences; this enhancer sequence is followed by a poly (U) tract, and a core promoter region (located in between − 19 and − 1 nts) containing a stem-loop (SL) structure [47]. The binding of RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) either at this SL-structure or at the oligo (U) stretches is essential for the sgRNA synthesis [48]. Furthermore, a poly (A) track located at − 20 nt to − 37 nt, with a tri-repeats of UUA in between − 38 and − 48 nt in the upstream, is also identified to be crucial for enhancing the transcription level [26]. Similar to BMV, the full MP-SGP of TMV is mapped within − 95 nt to + 40 nt, with its core elements in between − 35 nt and + 10 nt in respect to TSS; whereas, fully active and core CP-SGP was localized in between − 157 nt to + 54 nt and − 69 nt to + 12 nt, respectively [9]. Later on, a potential enhancer element in TMV is identified in the + 25 to + 55 nt zone with respect to CP-TSS [24]. Even if, a core promoter of viral sgRNA is sufficient enough to keep up with basal levels of transcription, the identification of full active promoter along with one or more properly spaced enhancer(s) is highly necessary to boost the overall synthesis of sgRNAs. Therefore, the identification and characterization of the key regulatory elements in the upstream and downstream of the promoters is important, so that, SGPs can be reinforced for developing a better virus-based vector system.

Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus (CGMMV), a cucurbit infecting member of the genus Tobamovirus is one of the suitable choice for the construction of protein expression-vector system in cucurbits [15, 22, 31, 40, 42, 51]. Alike other tobamoviruses, it has a unique genome (~ 6.4 kb) with four overlapping ORFs. The first two ORFs, located at the 5′ end of genome directing the expression of two functional proteins, viz., 129 kDa and 186 kDa protein, respectively [43]. Of them, the smaller 129 kDa protein (P129) has the N-terminal methyl transferase and C-terminal helicase domain. Whereas, the larger 186 kDa protein (P186), which is expressed occasionally via the read-through of leaky termination codon (UAG) of P129, contains a RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) domain [21]. These two proteins (P186 & P129) oligomerize to form the complex replicase enzyme which is necessary for the replication of genome and synthesis of sgRNAs from the last two ORFs encoding movement protein (MP) and coat protein (CP). But, interestingly, the structural overview of this complex enzyme is still missing, especially for the RdRp domain of tobamoviruses, and how the same RdRP performs both replication and transcription is still a mystery. Significantly, the replication of genomic RNA and transcription of sgRNAs is regulated by virus itself in a spatiotemporal manner. The accelerated synthesis of sgRNAs and their efficient expression in the late stage of infection make them a better choice for substituting with foreign protein. Even though, their transcriptional expression is largely regulated by some key elements of the respective promoters. Identification and characterization of such regulators in SGPs of CGMMV is yet to be addressed. In this study, we have adopted in silico approach for dissecting the CGMMV SGP regions in comparison to the other cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses. The technological advances in computational sciences in combination with the basic knowledge of biological sciences help us elucidate the inherent nature of regulatory motifs within the promoter [18]. Thus, initially, the tentative regulatory elements in the SGP of MP and CP of CGMMV were identified based on the localization of motif sequences; thereafter, similarity and dissimilarity of their SGPs were predicted based on their secondary structures. Further, the molecular docking of RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) at the promoter region helped identify the critical sequences in core and full promoters. A comparative analysis was made to testify our findings with previously reported subgenomic promoters in CGMMV [22] and other tobamoviruses. This study will be helpful, not only to delineate the SGP elements of CGMMV but also to depict the existence of similar elements in other cucurbit-infecting tobamoviruses.

Materials and methods

Retrieval of virus sequences and selection of promoter region

The full annotated, complete genome sequence of different tobamovirus species, viz., Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus (CGMMV), Cucumber fruit mottle mosaic virus (CFMMV), Cucumber mottle virus (CMoV), Kyuri green mottle mosaic virus (KGMMV), Zucchini green mottle mosaic virus (ZGMMV), Watermelon green mottle mosaic virus (WGMMV), Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), and Tomato mosaic virus (ToMV) were retrieved from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Variation in their genome length was noted. Further, the translation start site/TLSS (AUG) of MP and CP was spotted and used as the reference point (+ 1 nt) for mapping SGPs, as the TSS of MP-sgRNA and CP-sgRNA was remain unidentified for all the six cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses. Approximately, 230 nts from both sides (i.e., upstream and downstream region) of TLSS were selected for promoter mapping in MP, and that of 200 nts were chosen for CP. The sequence of the genomic (+) strand was used for motif identification and for further structural analysis of the SGP. The selected sequences were also converted into a complementary form to explore the binding potentiality of RdRp to the negative (−) stand that is necessary to initiate the sgRNA synthesis.

Alignment and comparison of the promoter sequences

The MP-SGP and CP-SGP sequences of the selected tobamoviruses were checked and pair-wise sequence alignment was performed by using Clustal W [41] with 1000 bootstrap value in Bioedit7 sequence alignment editor [12]. The aligned sequences were used to identify the similarity and genomic conservation within the respective SGP region of different tobamoviruses. Further, their evolutionary relationship was drawn through the construction of the phylogenetic tree based on the Maximum Likelihood method using 1000 bootstrap iterations in MEGA 7.0 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0) tool [17].

Prediction of RNA secondary structures

To identify the potential elements like hairpins, pseudoknots, etc., the RNA secondary structures of the MP-SGP and CP- SGP region of different tobamoviruses were designed using the Mfold Web server (http://mfold.rna.albany.edu/) at 37 °C folding temperature keeping other default parameters constant [53]. The most stable structures with the lowest Gibbs free energy in the output file were selected. The structures were also visualized using VARNA [5].

Identification of conserved motifs

To identify the presence of various motif sequences within the SGP region, the sequences of selected tobamoviruses were submitted in Plant Care database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). The conserved motif sequences were identified from the output file [19]. Only the presence of cis-elements in the ‘+’ strand were considered for single-stranded RNA genome.

Homology modeling of the three-dimensional structure of the protein

Due to the absence of the crystal structure of the RdRp enzyme of CGMMV, we had gone for the homology modeling of core RdRp of CGMMV for its structural and functional analysis. To implement this, the amino acid sequence of the CGMMV core RdRp spanning between 1414–1522 aa of 186 kDa protein (Accession no: ABG26381) was retrieved from the NCBI reference sequence database. The protein BLAST of 109 amino acid (aa) long core RdRp against the PDB (Protein Data Bank) database (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do) [1] resulted in a maximum 27.5% sequence similarity with the various crystal structures of viral RdRp. Of them, few PDB models were selected based on sequence identity, alignment score, positives, and gaps present between the template and the target sequences, and used as the suitable templates for generating target proteins models in swiss-model web-server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive/05JjhN/). Among the constructed models, only one model was selected based on percent similarity and homology with QMENE score. The structure was further subjected to structural refinement through web tool and model verification was done by a series of tests for its internal consistency and reliability through various bioinformatics tools viz., RAMPAGE (http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~rapper/rampage.Php) and Molprobity (http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/) for the determination of the stereochemical quality of models [23, 49], ERRAT plot (http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/ERRATv2/) to assess the distribution of different types of atoms with respect to one another in the protein model for deciding model reliability [4], and ProSA (https://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at/prosa.php) to indicate the overall model quality based on Z-scores and energy plots [46]. To confirm the structural homology with its template, the sequence alignment, and structural superimposition was performed using the Matchmaker tool in the Chimera platform [33].

Modeling of the three-dimensional structure of RNA

The whole SGP region of MP and CP was divided into the upstream and downstream parts from the TLSS. Then, both the upstream and down-stream promoter sequences are segmented into various lengths, i.e., 200 nt, 150 nt, 100 nt, and 50 nt from TLSS, irrespective of the presence of internal motifs, predicted knots/pseudoknots, and hairpin structures. The secondary structure of these segmented RNA sequences was derived from the Mfold web server. Now, a template-independent approach was adopted for designing the complex three-dimensional (3D) structures of segmented parts of both promoter regions. RNA composure (http://rnacomposer.cs.put.poznan.pl/) was used to draw the respective models of large RNA sequences along with secondary structure details in dot-bracket format [2]. The quality of the 3D models was checked by retrieving their secondary structures from 3D models in RNApdbee web-server (http://rnapdbee.cs.put.poznan.pl/) and compared with the originally generated 2D-models [52]. The selected 3D-models were then used for molecular docking analysis.

Protein–RNA docking and their analysis

Initially, the RNA–protein docking was performed using the PatchDock server (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock/patchdock.html), which a molecular docking algorithm performing based on the shape complementarity principles [37]. The PDB models of the RdRp and RNA molecules were submitted in this web-tool with default parameters. The recommended RMSD cutoff was restricted to 4˚A for protein-RNA interaction. Total of 20 complex PDB models were sorted based on the highest geometric shape complementarity score. Further, these complex models were submitted in the FireDock (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/FireDock/php.php) for refinement and re-scoring of rigid-body protein-RNA docking results [27]. The best protein-RNA interacting models with the lowest docking energy scores were selected to analyze their interaction and to predict their interface of RdRp binding at the SGP region. The complex interaction between protein and RNA was visualized using Pymol (https://pymol.org/2/) and Discovery studio visualizer (https://discover.3ds.com/discovery-studio-visualizer), to identify the interacting amino acid residues of RdRp with the nucleotides of RNA.

Result

Virus isolates and their sequences

A total of 8 different tobamoviruses viz., CGMMV (DQ767631), CFMMV (AF321057), CMoV (NC_008614), KGMMV (NC_003610), TMV (FR878069), ToMV (AJ243571), WGMMV (MH837097), ZGMMV (AJ252189) (Supplementary file 1) were selected in this study. Of them, six are pathogenic to cucurbits (CGMMV, CFMMV, CMoV, KGMMV, WGMMV, ZGMMV), whereas the other two (TMV, & ToMV) are pathogenic to the solanaceous hosts. Based on previous studies of the MP-SGP and CP-SGP in other viruses, a stretch of 400 nts of CP-SGP that included 200 nt of 3′ terminal end sequences of MP and 200 nt of 5′terminal of CP ORF were sliced out with respect to TLSS(+ 1). Similarly, another stretch of 460 nts in the MP-SGP that included 230 nts of 3′ terminal end of replicase (ORF2) and 230nt of 5′terminal end sequence of MP ORF with respect to MP-TLSS (+ 1) was selected for the analysis (Supplementary file 1). Interestingly, CGMMV, CMoV, and WGMMV possess overlapping ORFs, i.e., replicase overlaps with MP and MP overlaps with CP. In contrast, these ORFs, viz., replicase and MP, as well as MP and CP are separated by a small spacer sequence in CFMMV, KGMMV, and ZGMMV. This variation in genome organization may have some role in the sgRNA production.

Relationships of CGMMV MP-SGP and CP-SGP regions with the other cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses

The nucleotide sequences analysis of the MP-SGP and CP-SGP of tobamoviruses showed significant difference among them. The MP-SGP of CGGMV shared the maximum identity of 66.2% with that of CFFMV and 66.0% with CMoV, followed by 65% with WGMMV; and only 45–46% with TMV and ToMV (Supplementary file 2). Thus, in phylogenetic tree, CGMMV MP-SGP formed a distinct cluster from clade 1 containing CFMMV, KGMMV, and ZGMMV, and clade 2 composing CMoV and WGMMV (supplementary file 3). Similarly, the CGMMV CP-SGP had a maximum 49.7% sequence identity with that of CMoV, and 49% with WGMMV, but shared only 32.8 and 35% identity with that of TMV and ToMV, respectively (Supplementary file 2). The phylogenetic tree based on CP-SGP also depicts three distinct clades similar to MP-SGP, where CGMMV positioned separately from clade 1 and clade 2 (Supplementary file 3). Notably, both phylogenetic trees represent the similar evolutionary pattern of CGMMV. The sequence comparison and subsequent phylogenetic analysis of the MP-SGP and CP-SGP region indicated the possible structural difference among the members of different clades.

Distribution of cis-elements within MP and CP SGP regions

The mining of cis-elements in the SGP sequence had shown their presence in varying numbers among the cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses. A total of 15 cis-elements were identified in the MP-SGP region (Fig. 1a), and that of 20 elements were distributed in the CP-SGP region (Fig. 1b). Of them, CAAT box and TATA box elements were the most common and present in the highest copy number. Additionally, the jasmonic acid (MeJA)-responsive CGTCA-motifs/TGACG-motifs, salicylic acid-responsive TCA-motifs (CCATCTTCTT), abscisic acid-responsive ABRE motifs (ACGTG) was also observed in these regions of some viruses. Further, auxin-responsive TGA-elements (AACGAC), Gibberellin-responsive GARE-motifs (TCTGTTG) were also evident in few cases. The existence of such regulatory elements in the promoter region pointed out the plausible interactions with various host trans-acting factors during sgRNA production.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of putative cis-elements within subgenomic promoter region (SGP) of movement protein (MP) and coat protein (CP) of different cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses identified using plant care database web-server. The colour indication is used to represent different elements. The coordinates of the elements in parenthesis are indicated with respect to the translation start site (green vertical arrow). a Showing the location of MP-SGP in the CGMMV genome and the distribution of cis-elements in MP-SGP. A total 15 different cis-elements were identified within MP-SGP regions of different tobamoviruses. The occurrence and distribution of similar regulatory elements within MP-SGP of CGMMV, CMoV, and WGMMV indicates the structural similarity among them, whereas CFMMV, ZGMMV and KGMMV have a distinct pattern. b Showing the location of CP-SGP in the CGMMV genome and the distribution of cis-elements in CP-SGP. A total 20 different cis-elements were identified in the CP-SGP region of six cucurbit-infecting tobamoviruses. CGMMV CP-SGP possesses only 7 cis elements; although they are common to others but their distribution pattern depicts significant variation (color figure online)

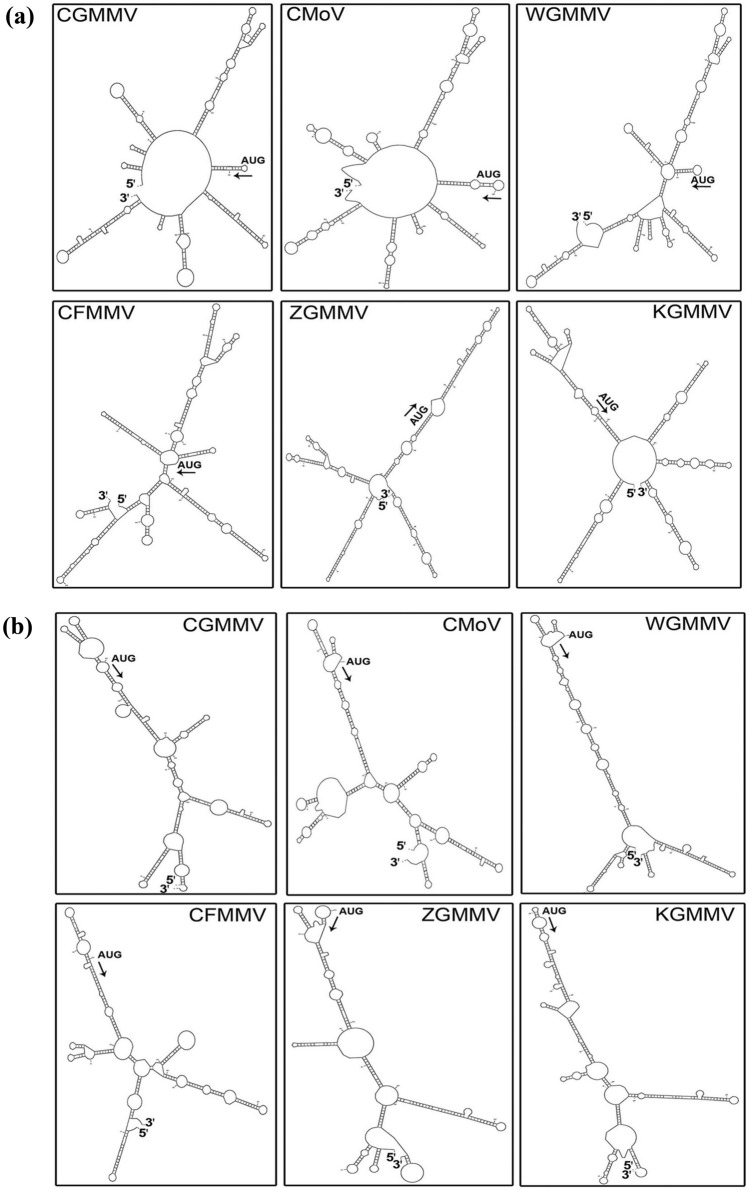

RNA secondary structures of MP and CP SGP

The predicted RNA secondary structures of MP-SGP and CP-SGP of various tobamoviruses were drawn to confer their structural similarity. The MP-SGP region of CGMMV spanning from 4764 to 5223 nt possessed many long SL structures, and showed extensive structural similarity with CMoV and WGMMV, but differs from other cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses. Usually, TLSS of MP in CGMMV along with CMoV and WGMMV was pitched in a terminal loop of an SL structure (SL-2) that was surrounded by many SL structures. Of them, SL-1 in the upstream region held small but structurally conserved/similar pseudoknots, observed within − 110 to − 60 nt in respect to the TLSS (Fig. 2a). Other than their structural similarity, they possessed some sequence similarity also. They might have a crucial role in enhancing the sgRNA transcription or may support the binding of RdRp enzyme. Likewise, in the downstream part, consecutive four large stem-loops (SL-3, SL-4, SL-5, SL-6) were identified in the case of CGMMV, which were identical to the counterpart of CMoV (Fig. 2a), but their functional significance is yet to establish in regulating the MP sgRNA production. Adversely, TLSS of MP in CFFMV, ZGMMV, and KGMMV was situated in the internal bulge or central loop of a long SL structure, and they were also structurally diverged from the group of cucurbit-infecting tobamovirus having overlapping ORFs (replicase and MP) in this SGP region.

Fig. 2.

RNA secondary structures of subgenomic promoter region (SGP) of movement protein (MP) and coat protein (CP) of different cucurbit-infecting tobamoviruses generated from M-fold web server using template RNA sequence. The arrow indicates the location of translation start site (TLSS) (+ 1) with AUG start codon (indicted with and arrow). a In MP-SGP of CGMMV, TLSS (+ 1) is located within a terminal loop of SL structure (SL-5) which is surrounded with other SL elements both in upstream (SL-1, SL-2, SL-3, SL-4) and downstream (SL-6, SL-7, SL-8, SL-9) regions that are indistinguishable from the secondary structures of CMoV, and WGMMV. The CFFMV, ZGMMV, and KGMMV shows different pattern of structural elements with localization of TLSS (+ 1) within internal buldge. b The secondary structure of CP-SGP of CGMMV has certain degree of similarity with that of CMoV and WGMMV. It contains two small hairpins emerged from a central loop located within 60 nt upstream with respect to TLSS (+ 1). These elements might have key regulatory function in sgRNA synthesis. ZGMMV also have similar pattern, but CFMMV and KGMMV have distinct features in this region. The start and end of the single stranded RNA are indicated with 5´ and 3´

Similarly, the CP-SGP region of CGMMV (5563–5962 nt) possessed SL structures with many internal bulges and loops. The TLSS (+ 1) was situated one such internal loop/bulge, and it was also evident in the case of other tobamviruses, viz., CMoV, CFFMV, WGMMV, KGMMV. Further, two short hair-pins might be the putative enhancers located just within − 60 nt upstream of TLSS, showed structural conservation among the tobamoviruses (Fig. 2b). Although the length distribution of the large SL structure possessing the TLSS (+ 1) along with putative enhance elements was varying, still its emergence from a large central loop that indicated the putative sites of RdRp binding for the sgRNA production. This length variation may correspond with the difference in the actual promoter length of these tobamoviruses.

Modeling of RNA and protein structures

The three-dimensional structures of RNA segments, representing various elements in the upstream as well as down-stream part of MP-SGP and CP-SGP regions were curated using a complementary strand of the viral SGP sequence in the RNA Composer web server based on a template-independent approach (Supplementary file 4). This webserver facilitated the automated 3D modeling of long RNA sequences based on their secondary structures [34]. The structural conservation of the 3D models was confirmed based on the retrieved secondary structures from the respective RNA PDB model using RNApdbee. The structural resemblance of RNA 3D models in 2D form with the previously predicted secondary structure of RNA ligands helped us to select for molecular docking study.

The homology modeling of core RdRp of replicase enzyme was performed based on template dependent approach. The core RdRp showed the maximum 27.45% sequence identity with RdRp of Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68); thus its crystal structure (5zit.1.A) was used for homology modeling of core RdRP of CGMMV. Model with lowest Q-MEAN score (− 4.14) was selected and submitted for further refinement. After structural refinement, 93.5% aa residues of core RdRp model were in the favoured region and 99.1% were in the allowed region as per the Ramachandan plot (Supplementary file 5). The distribution of > 90% residue in the favoured region ensured the overall acceptable quality of this model. Additionally, the global model quality estimate (GMQE) in ERRAT program for RdRp scored between 0 and 1(0.56 for RdRp core) indicating model stability (Supplementary file 5). Furthermore, the lower Z-score (− 0.73) generated in ProSA web-server was less than zero; thus, ensuring the reliability of this model for molecular interaction study.

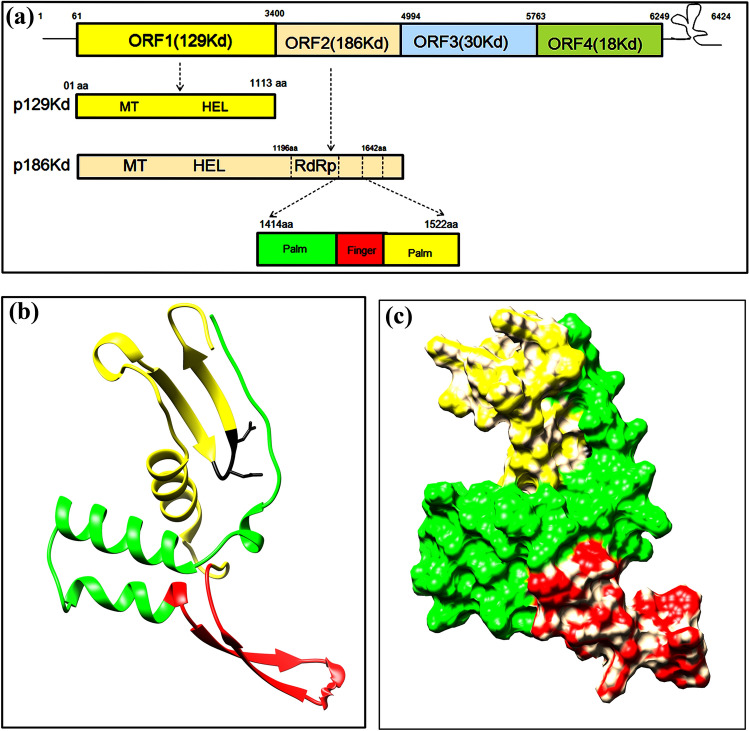

The overall homology of the core RdRp model matched with its template (5zit.1.A) with RMSD: 0.834, and Q-score: 0.202. Of 109 aa, 104 aa of core RdRp was fully superimposed on the 224 aa to 334 aa in the final alignment (Supplement file 5). The modeled structure of core RdRp (Fig. 3) overlapped with the part of palm (195–246, and 286–375) and finger (264–286 aa) subdomains of the template, and composed of 3 conserved structural motifs, viz., motif A (residues 02–14), motif B (residues 70–84), motif C (residues 92–102), out of seven motifs (A-G) in all RdRp, that expected to play a pivotal role in catalysis [20].

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional model of core RNA dependent RNA polymerase domain (RdRp) of CGMMV replicase enzyme complex. a Genome map of CGMMV depicts the expression of 129 kDa (from ORF1) and 186 kDa (from ORF2) protein that polymerizes to form the replicase complex. The RdRP is part of the 186 kDa protein with its core catalytic sites are located within 1414aa to 1522aa. b The tertiary structure of core RdRp domain consisting of palm sub-domain (1-41aa) represented in yellow colour, finger sub-domain (42-62aa) represented in red colour, followed by another palm sub-domain (63-109aa) represented in yellow colour. The conserved GDD motif was shown in black colour. c The surface expose model of core RdRp with different sub domains (represented with different colour) to active protein surface (color figure online)

Interactions of RdRp with MP SGP elements in the CGMMV genome

To identify key regulatory motifs in the MP-SGP region, the binding ability of RdRp to the counterpart in the negative strand was explored via molecular docking (Supplement file 6). In the upstream region, RdRp interacted with various sites spanning from − 1 to and − 136 nt (Table 1). Most of these sites were scattered and possessed small SL like structures and internal bulges. RdRp strongly preferred the double helix stem region of SL structures. Based on interaction analysis, four long nucleotide stretch (I, II, III, and IV) were identified within − 136 to − 114 nt (AAUUACCACGAAUAAAGGUAAA), − 64 nt to − 56 nt (AAAACAUUAA), − 53 nt to − 32 nt (AACAAACACAUUCAUAAACUCA), and − 26 nt to − 17 nt (CGCGGAAAAG) position (Fig. 4a) During scanning, RdRp showed strong binding affinity (with lowest binding energy) for − 26 nt to − 17 nt site through the formation of strong hydrogen bonds with LYS16, TYR17, LYS19, SER20 aa of the motif A in the palm subdomain of RdRp; thus could be predicted as the putative key elements in the core promoter. Similar strong interactions were noticed at the − 32 nt to − 53 nt and − 56 nt to − 65 nt position (Table 1).

Table 1.

Interactions of RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) with the regulatory elements of movement protein (MP) subgenomic promoter (SGP) region in the CGMMV genome

| Regulatory elements (Co-ordinates) |

Interacting nucleotides: amino acids (co-ordinates) in different interacting sites* |

|---|---|

|

I (− 136 to − 144) |

A(− 136):GLU11; A(− 135):ASP107, ASP13; A(− 134):ASP107; U(− 133):SER15; C(− 129): TYR67; A(− 128):LYS51, ALA90, MET92; G(− 126):HIS25, SER22; A(− 125):SER22, PHE24; A(− 124):SER22; U(− 123):TYR67; G(− 118):LYS63; U(− 117):GLN69; A(− 116):GLN56, ARG52, LYS19; A(− 115):LYS19; A(− 114):SER15, SER15, LYS16 |

|

II (− 64 to − 56) |

A(− 64):GLU11, ILE9, LEU10; A(− 62):PHE83; A(− 62):ASP96; C(− 61):SER91, ALA90; U(− 58):ALA31, LYS35; A(− 57):GLU34; A(− 56):ASP40 |

|

III (− 53 to − 32) |

A(− 53):TRP44; A(− 52):SER20, ILE41; A(− 50):MET45; A(− 49):CYS104; A(− 48):CYS104, ASP107, VAL75; C(− 47):LEU109, ASP107, ASP13; A(− 46):ASP13, LYS100; C(− 45):GLU11, ASP96; A(44):LEU116,ILE32; U(− 43):GLN56; U(− 42):ALA31; C(− 41):SER27; A(− 40):MET92, SER27; U(− 39):MET92, ASP23; A(− 38):LYS51; A(− 36):THR64, LEU65; C(− 35):THR64; C(− 33):LYS51; A(− 32):LE66,TYR67 |

|

IV (− 26 to − 17) |

C(− 26):TYR17, LYS16; G(− 25):SER20; C(− 24):ALA90; G(− 23):LEU116; A(− 21):LYS19, LYS16; A(− 20):LYS19; A(− 19):LYS19; A(− 18):SER72; G(− 17):LYS71 |

|

V (+ 33 to + 39) |

C(33):LEU116; A(34):LEU116; A(35):LEU12, ALA90; C(36):SER20; U(37):SER20; U(38):TYR68; U(39):SER22 |

|

VI (+ 99 to + 110) |

A(99): LEU116; G(100): LEU116; A(102): CYS88, ALA90, MET92; C(105): LYS114; A(106): LYS35; A(108): ASP96; A(110): LYS100 |

*Value in parenthesis indicating the coordinates of nucleotides in the RNA with respective to translation start site (TLSS). The nucleotides located upstream of TLSS (+ 1) have (−) markings; nucleotides located downstream of TLSS have (+) markings. The interacting partners were identified from the interaction analysis between core RdRp and RNA ligands derived from complementary sequences of MP-SGP region using Patch-dock web server

Fig. 4.

Interaction of RdRp with the different structural elements of subgenomic promoter region (SGP) of movement protein (MP) and coat protein (CP) of CGMMV. The RNA secondary structures of the SGPs in negative strand were generated from M-fold web server, and used to present the interaction between 3D model of RNA and core RdRp. The arrow mark indicates the location of translation start site (TLSS) (+ 1) with UAC as the start codon (green colour, indicated with an arrow), and the number in roman designate the putative interacting sites. a A total six RdRp binding sites are predicted within MP-SGP of CGMMV; four (I to IV) are located in the upstream, and two (V and VI) in the downstream region of SGP. b A total five locations are predicted for the RdRp binding within CP-SGP of CGMMV, of them two putative sites (I, II) are in the upstream region and three (III, IV, V) are in the downstream region. The detail of the interacting nucleotides of RNA and amino acids of RdRp are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The nucleotides in yellow represent the different cis-elements (identified based on plant care database) distributed within SGP regions (color figure online)

Similarly, in the downstream part (+ 1 to + 200 nt), very strong binding of SER20, SER22, TYR68, ALA90, LEU116 aa of the motif A and C of RdRp was visualized in the internal bulge (CAACUUU) located at + 33 to + 39 nt near to the TLSS (+ 1), This could be prognosticated as the putative core promoter. Besides this, different binding interfaces were scattered in different locations (Fig. 4a). Of them, a long stretch (AGAAUUCAUAAA) was identified at 99 nt to 110 nt that folded into the complex helix with SL structure, where strong interaction with the specific amino acids (CYS88, ALA90, MET92, ASP96, LYS100, LYS114, LEU116) of RdRp was evident (Table 1). Overall, our in silico analysis of the MP-SGP indicated that the SL structures distributed within − 136 nt of the upstream and + 110 nt of downstream are the important elements for the binding with the RdRp domains; thus proposed to be the putative full promoter for MP protein expression, whereas − 64 nt to + 39 nt region relative to TLSS (+ 1) could be the core promoter, that is sufficient enough for obtaining a basic level of expression.

Interaction of RdRp with CP-SGP elements in the CGMMV genome

The molecular docking of RdRp with the upstream of CP-SGP revealed five potential sites for RdRp binding (Supplement file 7). Interestingly, RdRp was found to interact strongly nearby region (within ± 20 nt) of the CP-TLSS (+ 1), mostly around the conserved pseudoknot where TLSS was located. Thereafter, some motif sequences were identified to be distributed in the upstream and downstream region of CP-SGP, where a strong affinity of RdRp binding was visualized. Of them, the nucleotide stretch (UUGGAGGUUUAGCCUCCA) is located at − 60 to − 43 nt zone, and another stretch (GGUCAA) located at − 114 nt to − 109 nt region, was pitched at the internal SL elements (Fig. 4b). The strong binding of RdRp with its palm and finger subdomains signified its functional importance, thus could be proposed as the boundary for the active promoter elements in the upstream region. Likewise, in the downstream region, binding of RdRp at three different sites (9–21 nt; 97–114 nt, and 136–144 nt) in CP-SGP was observed. The strongest binding of RdRp was evident at + 9 to + 21 nt, which was just adjacent to CP-TLSS. Further, strong binding was visualized with the double helix of SL structure, situated within + 110 to + 140 nt zone. The amino acids like LYS16, LYS19, GLN21, SER22, LYS51, PHE58, THR64, LEU65, CYS88, ALA90, ASP57, ALA60, GLY61, LYS63, and LEU65 of RdRp showed a potential strong affinity for this binding (Table 2). This analysis helped us to predict some of the RNA regulatory elements that were identified to be the potentiality site for binding with palm and finger sub-domain of RdRp. These could be proposed as the essential regulatory elements that were necessary for CP-sgRNA synthesis.

Table 2.

Interactions of RNA dependent RNA polymerase with the regulatory elements of coat protein (CP) subgenomic promoter (SGP) region in the CGMMV genome

| Regulatory elements (Co-ordinates) |

Interacting nucleotides: amino acids (co-ordinates) in different interacting sites* |

|---|---|

|

I (− 114 to − 109) |

G(− 114):ASP57; G(− 113):GLN56; U(− 112):LYS19, GLN69; C(− 111):LYS19; A(− 110):VAL14; A(− 109):SER20, LYS16 |

|

II (− 60 to − 43) |

U(− 60): ILE41; U(− 59): PHE24; G(− 58):CYS88; G(− 57):SER22; A(− 56): TYR68; G(− 55):VAL75; G(− 54):VAL75, ASP7, TYR67; U(− 53):LYS51; U(− 52):LYS51; U(− 51):ARG52; A(− 50):LYS51 G(− 49):MET30,SER27; C(− 48):ASP23, PHE24; C(− 47):VAL75, SER22, SER22; U(− 46):MET45, VAL75, ARG70, CYS88; C(− 45):TRP33,TRP46; C(− 44):TYR111; A(− 43):LEU116 |

|

III (+ 09 to + 21) |

G(9):LYS35; U(10):LYS35; U(11):ILE54; A(12):LYS35; G(13):SER72; G(14):ASP106; C(15):VAL14; U(16):ASP96, LYS100, SER15; A(17):ASP96, LYS97, LYS16; G(18):LYS16; U(19):GLN56, LYS16; G(20):THR64, GLN56;U(21):THR64 |

|

IV (+ 97 to 114) |

C(97):GLU11; C(98):GLU8, ILE9, GLU11, LEU10; A(99):GLU8, LEU116; G(101):GLY115; C(103):CYS104; A(105):TRP33; A(106):VAL75, THR76; A(107):MET45, VAL75, TRP46; G(108):MET45; G(109):ASP74; U(110):ASP74; C(111):PHE58, LYS71; U(112):GLN56; G(113):PHE58; A(114):PHE58 |

|

V (+ 136 to + 144) |

G(136):GLN59; G(138):LYS63; C(139):LEU65; U(140):TYR67,TYR68; C(141):GLN69, LYS19,GLN69,ARG52; G(143):SER72; G(144):SER72 |

*Value in parenthesis indicating the coordinates of nucleotides in the RNA with respective to translation start site (TLSS). The nucleotides located upstream of TLSS (+ 1) have (−) markings; nucleotides located downstream of TLSS have (+) markings. The interacting partners were identified from the interaction analysis between core RdRp and RNA ligands derived from complementary sequences of CP-SGP using Patch-dock web server

Discussion

The valorization of plant viruses as the suitable expression vector for the in planta production of foreign proteins is becoming popular with the aim of low-cost manufacturing of vaccines and therapeutics. This conversion of the virus from pathogenic entity to biological toolkit requires extensive genome modification that relies on the identification of cis-regulatory elements and their subsequent engineering for efficient expression; so that a higher amount of protein can be expressed within the limited time scale. Identification of viral promoters for replication and subgenomic RNA production is one such step, as these promoters possess some key regulatory elements like enhancers, spacer sequences that are indispensable for virus replication, and protein translation.

Hitherto, various in vivo and in vitro approaches were adopted for the identification and characterization of these elements; all of them are cost-intensive and time-consuming. Thus, an alternative strategy-based bioinformatics tools become a choice for the robust prediction of these regulatory elements. These tools can accurately identify the conserved/census elements within a genome; thus, holds a great promise to bridge the gap [29]. Previously, different scientists have used the computational approach for genome-wide prediction and characterization of promoter elements in various plants [16, 18] as well as in viruses [10, 25]. But they were restricted to the identification of DNA promoters and its associated elements. Here, we have adopted a similar approach to predict the RNA promoter elements for sgRNA production in CGMMV. Earlier, the borderline of CP-SGP was mapped for CGMMV [22], CFFMV [35], and TMV [9], where multiple deletions of upstream and downstream sequences in respect to either TSS or TLSS (UAC codon) was performed to delineate the SGP margins. The same strategy is also followed for internal SGP mapping in the case of other RNA viruses, viz., BMV [48], CMV [3], etc. Notably, the location of TSS is very non-specific, and it lies just few nucleotide upstream of TLSS. Although, TSS of CP-sgRNA of CGMMV was reported by Liu et al. [22], lots of ambiguity still persists, as reported in case of TMV [9]. Whereas, the location of TLSS is highly specific and it lodged at AUG start codon of the respective ORF. Thus, TLSS of MP-sgRNA, and CP-sgRNA is selected as the reference point for determining the length of SGP as evident in case of CFMMV [35]. All such site-specific deletions in the upstream and down stream with respect to TSS or TLSS are decided based on the presence of knots, pseudoknots, and stem-loops in the RNA secondary structures of these viruses. These structural elements and sequences in the promoter region are responsible for RdRp binding. Interestingly, viral RdRp of BMV and TMV have the overall structural similarity with other polymerases, viz., DNA- dependent DNA polymerase (DdDp), DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (DdRp) and reverse transcriptase/RNA dependent DNA polymerase (RdDp) [32] and composed of palm, thumb and finger sub-domains; the palm sub-domain contains the catalytic core which is embedded with five motifs(A-E) and the finger subdomain is housed with motif F and G [44] which are essential for binding to RNA and subsequent RNA polymerization. Like other polymerases, in the search for promoter, the RNA polymerase preliminary binds to some cis elements (structural shape and sequence), located in the template and non-template strand of the promoter, which helps them to unwind the strands to create open promoter, followed by subsequent specific recognition of the template strand for the synthesis of RNA [8]. But, the promoter recognition events of viral RNA polymerase (RdRp) are missing. Thus, it can be assumed that the viral RdRp, especially for positive stranded RNA viruses requires the double helix from (dsRNA) containing both positive and negative strand of the genome, for the recognition of promoter to start the replication of a new positive strand and the transcription of subgenomic RNA, rather than only on the newly synthesized negative strand. The in vivo colonization of TMV either in replicative form (RF) or in replicative intermediates’ (RI) during replication supports our hypothesis [50]. Actually, the negative strands never remain free; and always engaged in the synthesis of multiple copies of either gRNAs or sgRNAs, in time dependent manner. The existence of free progeny viral genome and sgRNAs in huge copy number [45] indicates the same. Practically; a single viral polymerase of tobamoviruses can recognize different types of promoters necessary for genomic RNA replication and sgRNA production. Despite their sequence dissimilarity, few common structural features still exist [11, 30], which acts as the signal for RdRp binding at 5′ promoter and SGP. The promoter recognizing the ability of RdRp is exploited here to delineate the SGP elements. Understanding about these regulatory elements/sequences is the key to portray the promoter for sgRNAs synthesis and their recognition by core RdRp domain of replicase enzyme is used as the yardstick for the SGP mapping.

Conventionally, tobamoviruses produce two sgRNAs, and the first MP-sgRNA promoter is overlapped in the 3′ terminal of ORF2 encoding RdRp protein and 5′ terminal of ORF4 encoding MP, whereas the second CP-sgRNA lies in between the 3′ terminal of MP coding sequences(MP-CDS) and 5′ terminal of CP-CDS [9, 45]. Sometimes, these ORFs are overlapping [7] or maybe separated by different size of intron/spacer [7]. This diversification in the genome organization of tobamoviruses leads to the variation in subgenomic promoter length. Thus, based on sequence information, it is quite difficult to map their actual length. As these SGPs are placed anywhere within the genome and enriched with various regulatory elements. Thus, mapping based on deletion mutagenesis of sequences around the transcription start site of sgRNA would not be enough for accurate prediction of promoter length. Thus, robust bioinformatics tools are used to support the deletion-based mapping process. In the present study, initially, the RNA secondary structure of the MP-SGP and CP-SGP region of six cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses was generated to analyze the identical stem-loops (SL) and other regulatory elements. The existence of trans-acting binding sites was also determined and various regulatory elements, viz., CAAT-box, TATA-box are identified which are distributed in a noncanonical manner. Nevertheless, some degree of similarities persists among the cucurbit infecting tobamovirus species; that is sufficient enough to decipher the key regulatory elements within SGP regions of CGMMV. Further, scanning of a strong binding affinity of RdRp throughout the SGP region helps to predict the actual promoter length.

According to our prediction, a zone spanning from − 64 nt to + 39 nt in respect to MP-TLSS (+ 1) is the core active promoter for the expression of MP protein; while fully active promoter probably distributed within − 136 nt to + 110 nt region with respect to MP-TLSS. Previously, the SGP region of MP was mapped in TMV and was identified at − 95 to + 40 nt of MP-TSS with the − 35 to + 10 nt as the core promoter [9]. Akin to TMV, the MP-SGP of CGMMV is composed of multiple SL and bulge like structures which are essential for the RdRp binding as evident from our finding too. The site-directed deletion and substitution mutagenesis assay revealed the structural significance of SL1 for MP sgRNA synthesis in TMV, rather than its sequence [9]. Unfortunately, such information is missing for the cucurbit infecting tobamoviruses. Despite significant sequence dissimilarity in sgRNA promoters, the considerable structural homology persists among CGMMV, CMoV, and WGMMV. Our finding will be helpful to stipulate the SGP length of members of this subgroup.

On the contrary, we have predicted certain key regulatory elements within − 114 nt to + 144 nt region of CP-SGP with respect to TLSS of CP-ORF. These critical regulatory elements are necessary for the binding of RdRp and transcription of CP sgRNA. Our finding is corroborated with the recent report of Liu et al. [22] showing − 110 to + 175 nt relative to CP-TSS as the putative full promoter for CP-sg RNA production in CGMMV, where CP-TSS was presumed to be 13 nt upstream to CP-TLSS (AUG start codon). In our in silico prediction, the critical length of CP-SGP (− 114 nt to + 144 nt with respect to TLSS) is positioned very close to their wet lab observation (− 123 nt to + 162 nt with respect to TLSS). We also visualized the strong binding affinity of RdRp at − 60 to + 21 nt zone, with respect to CP-TLSS (+ 1). Interestingly, a strong affinity of RdRp binding was also evident at the SL structures located at 97–114 nt downstream zone, which signifies our previous report which showed sufficient expression of eGFP carrying + 105 nt of CP-SGP [15]. It indicates that key regulatory elements are residing within + 114 nt zone with respect to CP-TLSS.

In conclusion, it is obvious that most of the viral RNA promoters consist of a core promoter region, along with one or more properly spaced enhancer(s) distributed within full promoter range which can support higher levels of transcription. Therefore, identification of a full active promoter is highly necessary to boost the overall synthesis of sgRNAs. These are usually extended long in the upstream or downstream of the promoter transcription start site as reported in CGMMV along with other tobamovirus viruses; thus very cumbersome to decipher through the site-directed deletion mutagenesis approach. Here, the computational approaches adopted to simplify the process, and the knowledge generated from this study will contribute significantly to further validation of subgenomic promoters. In this way, elucidation of the structure and function of viral promoters can speed up for other viruses also.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The financial support as PhD scholarship to A. Chottopadhyay from the PG School, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi is thankfully acknowledged.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anirban Roy, Email: anirbanroy75@yahoo.com.

Bikash Mandal, Email: leafcurl@rediffmail.com.

References

- 1.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biesiada M, Purzycka KJ, Szachniuk M, Blazewicz J, Adamiak RW. Automated RNA 3D structure prediction with RNAComposer. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1490:199–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6433-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen MH, Roossinck MJ, Kao CC. Efficient and specific initiation of subgenomic RNA synthesis by cucumber mosaic virus replicase in vitro requires an upstream RNA stem-loop1. J Virol. 2000;74(23):11201–11209. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.23.11201-11209.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993;2(9):1511–1519. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darty K, Denise A, Ponty Y. VARNA: interactive drawing and editing of the RNA secondary structure. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(15):1974–1975. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorokhov YL, Ivanov PA, Komarova TV, Skulachev MV, Atabekov JG. An internal ribosome entry site located upstream of the crucifer-infecting tobamovirus coat protein (CP) gene can be used for CP synthesis in vivo. J Gen Virol. 2006;87(9):2693–2697. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82095-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorokhov YL, Sheshukova EV, Komarova TV. Tobamovirus 3′-terminal gene overlap may be a mechanism for within-host fitness improvement. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:851. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feklistov A. RNA polymerase: in search of promoters. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1293:25–32. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grdzelishvili VZ, Chapman SN, Dawson WO, Lewandowski DJ. Mapping of the Tobacco mosaic virus movement protein and coat protein subgenomic RNA promoters in vivo. Virology. 2000;275(1):177–192. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta D, Ranjan R. In silico comparative analysis of promoters derived from plant para retroviruses. Virus Dis. 2017;28(4):416–421. doi: 10.1007/s13337-017-0410-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haasnoot PC, Olsthoorn RC, Bol JF. The Brome mosaic virus subgenomic promoter hairpin is structurally similar to the iron-responsive element and functionally equivalent to the minus-strand core promoter stem-loop C. RNA. 2002;8(1):110–122. doi: 10.1017/S1355838202012074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Sympos Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez-Garcia CM, Finer JJ. Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements. Plant Sci. 2014;217:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann MA, Sethna PB, Brian DA. Bovine coronavirus mRNA replication continues throughout persistent infection in cell culture. J Virol. 1990;64(9):4108–4114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.64.9.4108-4114.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jailani AA, Solanki V, Roy A, Sivasudha T, Mandal B. A CGMMV genome-replicon vector with partial sequences of coat protein gene efficiently expresses GFP in Nicotiana benthamiana. Virus Res. 2017;233:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koramutla MK, Bhatt D, Negi M, Venkatachalam P, Jain PK, Bhattacharya R. Strength, stability, and cis-motifs of in silico identified phloem-specific promoters in Brassica juncea (L.) Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:457. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 70 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumari S, Ware D. Genome-wide computational prediction and analysis of core promoter elements across plant monocots and dicots. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e79011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P, Rombauts S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Wang M, Chen Y, Hu T, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Bi G, Wang W, Liu E, Han J, Lu T, Su D. Structure of the enterovirus D68 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in complex with NADPH implicates an inhibitor binding site in the RNA template tunnel. J Struct Biol. 2020;211(1):107510. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li R, Zheng Y, Fei Z, Ling KS. First complete genome sequence of an emerging cucumber green mottle mosaic virus isolate in North America. Genome Announce. 2015;3(3):e00452–e00515. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00452-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M, Liu L, Wu H, Kang B, Gu Q. Mapping subgenomic promoter of coat protein gene of Cucumber green mottle mosaic virus. J Integr Agric. 2020;19(1):153–163. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62647-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, DeBakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure validation by Cα geometry: ϕ, ψ and Cβ deviation. Proteins: Struct, Funct, Bioinf. 2003;50(3):437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Man M, Epel BL. Characterization of regulatory elements within the coat protein (CP) coding region of Tobacco mosaic virus affecting subgenomic transcription and green fluorescent protein expression from the CP subgenomic RNA promoter. J Gen Virol. 2004;85(6):1727–1738. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marks H, Ren XY, Sandbrink H, van Hulten MC, Vlak JM. In silico identification of putative promoter motifs of white spot syndrome virus. BMC Bioinf. 2006;7(1):309. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsh LE, Dreher TW, Hall TC. Mutational analysis of the core and modulator sequences of the BMV RNA3 subgenomlc promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(3):981–995. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mashiach E, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Andrusier N, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. FireDock: a web server for fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W229–W232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller WA, Koev G. Synthesis of subgenomic RNAs by positive-strand RNA viruses. Virology. 2000;273(1):1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nain V, Sahi S, Kumar PA. In silico identification of regulatory elements in promoters. In: Lopes H, editor. Computational biology and applied bioinformatics. In Tech; 2011. pp. 47–66. 10.5772/22230.

- 30.Olsthoorn RC, Haasnoot PJ, Bol JF. Similarities and differences between the subgenomic and minus-strand promoters of an RNA plant virus. J Virol. 2004;78(8):4048–4053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4048-4053.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ooi A, Tan S, Mohamed R, Rahman NA, Othman RY. The full-length clone of cucumber green mottle mosaic virus and its application as an expression system for Hepatitis B surface antigen. J Biotechnol. 2006;121(4):471–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Reilly EK, Kao CC. Analysis of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase structure and function as guided by known polymerase structures and computer predictions of secondary structure. Virology. 1998;252(2):287–303. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popenda M, Szachniuk M, Antczak M, Purzycka KJ, Lukasiak P, Bartol N, Blazewicz J, Adamiak RW. Automated 3D structure composition for large RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(14):e112. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhee SJ, Jang YJ, Lee GP. Identification of the subgenomic promoter of the coat protein gene of cucumber fruit mottle mosaic virus and development of a heterologous expression vector. Arch Virol. 2016;161(6):1527–1538. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2808-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirawski J, Voyatzakis A, Zaccomer B, Bernardi F, Haenni AL. Identification and functional analysis of the turnip yellow mosaic tymovirus subgenomic promoter. J Virol. 2000;74(23):11073–11080. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11073-11080.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucl Acids Res. 2005;33:W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sethna PB, Hung SL, Brian DA. Coronavirus subgenomic minus-strand RNAs and the potential for mRNA replicons. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86(14):5626–5630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sztuba-Solińska J, Stollar V, Bujarski JJ. Subgenomic messenger RNAs: mastering regulation of (+)-strand RNA virus life cycle. Virology. 2011;412(2):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teoh PG, Ooi AS, AbuBakar S, Othman RY. Virus-specific read-through codon preference affects infectivity of chimeric cucumber green mottle mosaic viruses displaying a dengue virus epitope. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/781712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tran HH, Chen B, Chen H, Menassa R, Hao X, Bernards M, Hüner NP, Wang A. Development of a cucumber green mottle mosaic virus-based expression vector for the production in cucumber of neutralizing epitopes against a devastating animal virus. J Virol Methods. 2019;269:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ugaki M, Tomiyama M, Kakutani T, Hidaka S, Kiguchi T, Nagata R, Sato T, Motoyoshi F, Nishiguchi M. The complete nucleotide sequence of cucumber green mottle mosaic virus (SH strain) genomic RNA. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(7):1487–1495. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkataraman S, Prasad B, Selvarajan R. RNA dependent RNA polymerases: insights from structure, function and evolution. Viruses. 2018;10(2):76. doi: 10.3390/v10020076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe Y, Meshi T, Okada Y. Infection of tobacco protoplasts with in vitro transcribed tobacco mosaic virus RNA using an improved electroporation method. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:65–69. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81191-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl_2):W407-10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wierzchoslawski R, Dzianott A, Bujarski J. Dissecting the requirement for subgenomic promoter sequences by RNA recombination of brome mosaic virus in vivo: evidence for functional separation of transcription and recombination. J Virol. 2004;78(16):8552–8564. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8552-8564.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wierzchoslawski R, Urbanowicz A, Dzianott A, Figlerowicz M, Bujarski JJ. Characterization of a novel 5′ subgenomic RNA3a derived from RNA3 of Brome mosaic bromovirus. J Virol. 2006;80(24):12357–12366. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01207-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams CJ, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Prisant MG, Videau LL, Deis LN, Verma V, Keedy DA, Hintze BJ, Chen VB, Jain S. MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018;27(1):293–315. doi: 10.1002/pro.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young ND, Zaitlin M. An analysis of tobacco mosaic virus replicative structures synthesized in vitro. Plant Mol Biol. 1986;6:455–465. doi: 10.1007/BF00027137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zheng H, Xiao C, Han K, Peng J, Lin L, Lu Y, Xie L, Wu X, Xu P, Li G, Chen J. Development of an agroinoculation system for full-length and GFP-tagged cDNA clones of cucumber green mottle mosaic virus. Arch Virol. 2015;160(11):2867–2872. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2584-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zok T, Antczak M, Zurkowski M, Popenda M, Blazewicz J, Adamiak RW, Szachniuk M. RNApdbee 20: multifunctional tool for RNA structure annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W30–W35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.