Abstract

Objective

Syphilis rates among women in the USA more than doubled between 2014 and 2018. We sought to identify correlates of syphilis among women enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) to inform targeted interventions.

Methods

The retrospective cross-sectional analysis of secondary data included women with HIV or at-risk of HIV who enrolled in the multisite US WIHS cohort between 1994 and 2015. Syphilis screening was performed at baseline. Infection was defined serologically by a positive rapid plasma reagin test with confirmatory treponemal antibodies. Sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics stratified by baseline syphilis status were compared for women enrolled during early (1994–2002) and recent (2011–2015) years. Multivariable binomial modelling with backward selection (p>0.2 for removal) was used to model correlates of syphilis.

Results

The study included 3692 women in the early cohort and 1182 women in the recent cohort. Syphilis prevalence at enrolment was 7.5% and 3.7% in each cohort, respectively (p<0.01). In adjusted models for the early cohort, factors associated with syphilis included age, black race, low income, hepatitis C seropositivity, drug use, HIV infection and >100 lifetime sex partners (all p<0.05). In the recent cohort, age (adjusted prevalence OR (aPOR) 0.2, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.6 for 30–39 years; aPOR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2 to 1.0 for 40–49 years vs ≥50 years), hepatitis C seropositivity (aPOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.0 to 4.1) and problem alcohol use (aPOR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.4) were associated with infection.

Conclusions

Syphilis screening is critical for women with HIV and at-risk of HIV. Targeted prevention efforts should focus on women with hepatitis C and problem alcohol use.

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is an easily detectable and treatable STI; however, rates of syphilis continue to increase among select populations in high-income countries and remains pervasive in low-income and middle-income countries.1 In 2016, the WHO released a new strategy to combat STIs with goals focused on the elimination of congenital syphilis by implementing comprehensive syphilis screening and treatment among pregnant women and a target of 90% reduction in syphilis incidence globally by 2030.2 Syphilis screening recommendations for non-pregnant women in the USA are based largely on determination of risk.3 4 Acquisition risk is variably defined as a history of syphilis, reporting a sex partner with syphilis, living with HIV or having multiple (>3) sex partners in the past year.5 6 Emerging evidence suggests that risk factors for syphilis in the current epidemic may vary for women (drug use) and men (sex with men)7 8; and these factors vary by race as well since there is still an enduring high level of racial disparity between syphilis rates among blacks and whites in the USA.9 10 Current guidelines recommend more frequent syphilis testing (every 3–6 months) for men who have sex with men with persistent risk behaviours and does not address specific needs for women.3 4

More than 35 000 cases of primary and secondary syphilis were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2018.11 Early syphilis rates in women increased 170% from 2014 at 1873 (1.3 cases per 100 000 population) to 5047 (3 cases per 100 000 population) in 2018.11 The estimated prevalence of early syphilis among US women living with HIV in 2018 was 4%.11 Syphilis increases the likelihood of HIV acquisition and transmission, and co-infection is common.12

STI surveillance reports stratify syphilis rates according to the basic demographic information available (age, sex, race and region).11 13 The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is a prospective, multicentre, longitudinal cohort study that has enrolled nearly 5000 women living with HIV and at-risk of HIV infection in the USA since 1994. Additional data collected in research studies such as the WIHS provide information about sensitive behaviours such as drug use and sexual practices using validated questionnaires. These details can offer critical insights about factors associated with syphilis infection.

A nuanced understanding of the risk of syphilis acquisition can be used to define populations of women who are disproportionally impacted by infection. In this analysis, we sought to identify specific risks for syphilis in the early and recent cohorts of WIHS.

METHODS

Study design

This is a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of data collected as part of the prospective WIHS cohort study. It focuses on information collected at enrolment.

Study population

WIHS recruitment and protocol procedures have been published previously.14 15 Briefly, enrolment in WIHS occurred during four waves 1994–1995 (2054 HIV+; 569 HIV−), 2001–2002 (737 HIV+, 406 HIV−), 2011–2012 (276 HIV+; 95 HIV−) and 2013–2015 (610 HIV+; 235 HIV−). Women were enrolled by trained staff at 11 sites (Atlanta, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; Bronx, New York; Brooklyn, New York; Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Chicago, Illinois; Jackson, Mississippi; Los Angeles, California; Miami, Florida; San Francisco, California; and Washington, DC). HIV-positive or HIV-negative women at risk of HIV acquisition (based on STI history and/or sociobehavioural characteristics) were recruited from facilities, clinics and community venues to include women irrespective of engagement in care. Positive HIV status required a positive ELISA test and a confirmatory western blot. Standardised interviews with structured questionnaires and physical examinations were conducted by study staff at the baseline visit to obtain detailed information from women about demographic, socioeconomic, behavioural and clinical characteristics. Routine syphilis testing was only performed at baseline per study protocol. Women identified as positive for syphilis were either treated by the respective study site or referred for treatment. Clinical staging of syphilis and treatment history was not available for most women in the parent study. For this study, the cohort was divided into two time periods: early enrolment (1994–2002) and recent enrolment (2011–2015).14 Participants provided written informed consent for screening and enrolment with protocols approved by institutional review boards at each site.14 16

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Among WIHS participants, the age and racial/ethnic distributions of HIV-negative women are similar to those of HIV-positive women in the cohort (black 72%, white 11%, Hispanic 14% and other 3%), which are generally representative of women living with HIV in the USA. Of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in WIHS, most were poor (more than half reported an annual household income of US$≤18 000) and over one-third have attained less than a high school education. Self-reported HIV exposure risk at study entry was similar in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, including IDU, hetero-sexual contact and transfusion risk.14 15 All cisgender women who enrolled in WIHS between 1994 and 2015 with syphilis screening performed at enrolment were included in this analysis. Syphilis infection was defined as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test at enrolment with a positive confirmatory treponemal antibody test.

Variables

Independent variables included: age (categorised as 16–29, 30–39, 40–49 and ≥50 years), race (black vs white/other), year of WIHS enrolment (early (1994–1995 and 2001–2002) versus recent (2011–2012 and 2013–2015)), low income (defined as an annual income US$<12000), marital status (defined as married/living with partner vs single/widowed/divorced/separated/other) and hepatitis C (HCV) infection (defined as a HCV antibody positivity). Self-reported information was collected for the following variables: number of lifetime sex partners, transactional sex (defined as ever having sex in exchange for drugs, money or shelter), problem alcohol use (defined as consumption of >7 drinks per week per the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism,17 non-injection drug use (IDU) (active or prior use of cocaine/crack, heroin, methamphetamines or other drugs) and IDU (active or prior use of injectable drugs).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics according to syphilis serostatus were compared for early and recent cohort enrollees with HIV infection as an independent variable in the primary analysis, while baseline characteristics according to syphilis serostatus were compared for women living with and without HIV in the secondary analysis. χ2 testing was used for comparisons of categorical variables and analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables. Data were missing for <5% for all of the independent variables in this analysis. Some independent variables were correlated: (1) IDU and HCV in primary and secondary analyses, (2) transactional sex and number of lifetime sex partners in the primary analysis and (3) enrolment site and cohort wave in the secondary analysis. We selected HCV and number of lifetime sex partners for the adjusted models in both sets of analyses since these variables had fewer missing data, with the addition of cohort wave in the secondary analyses. In the secondary analysis, correlates of syphilis were analysed according to HIV status.

Univariate logistic regression was performed to identify risk factors for syphilis. HIV status was included in all models due to the cohort characteristics and its relationship with syphilis. Crude prevalence odds ratios (PORs), 95% CIs and p values were calculated. Variables of interest and univariate variables with p<0.2 in early and recent cohorts were also included in the full multivariable log-binomial regression. Backward selection was used to develop a model with all independent variables statistically significantly associated with the outcome at a p value less than or equal to 0.20. One variable, with the highest p value, was removed from the multivariable model at a time until all remaining variables were significantly associated (p<0.2) with syphilis.18 Adjusted POR (aPOR), 95% CI and p values were calculated.

RESULTS

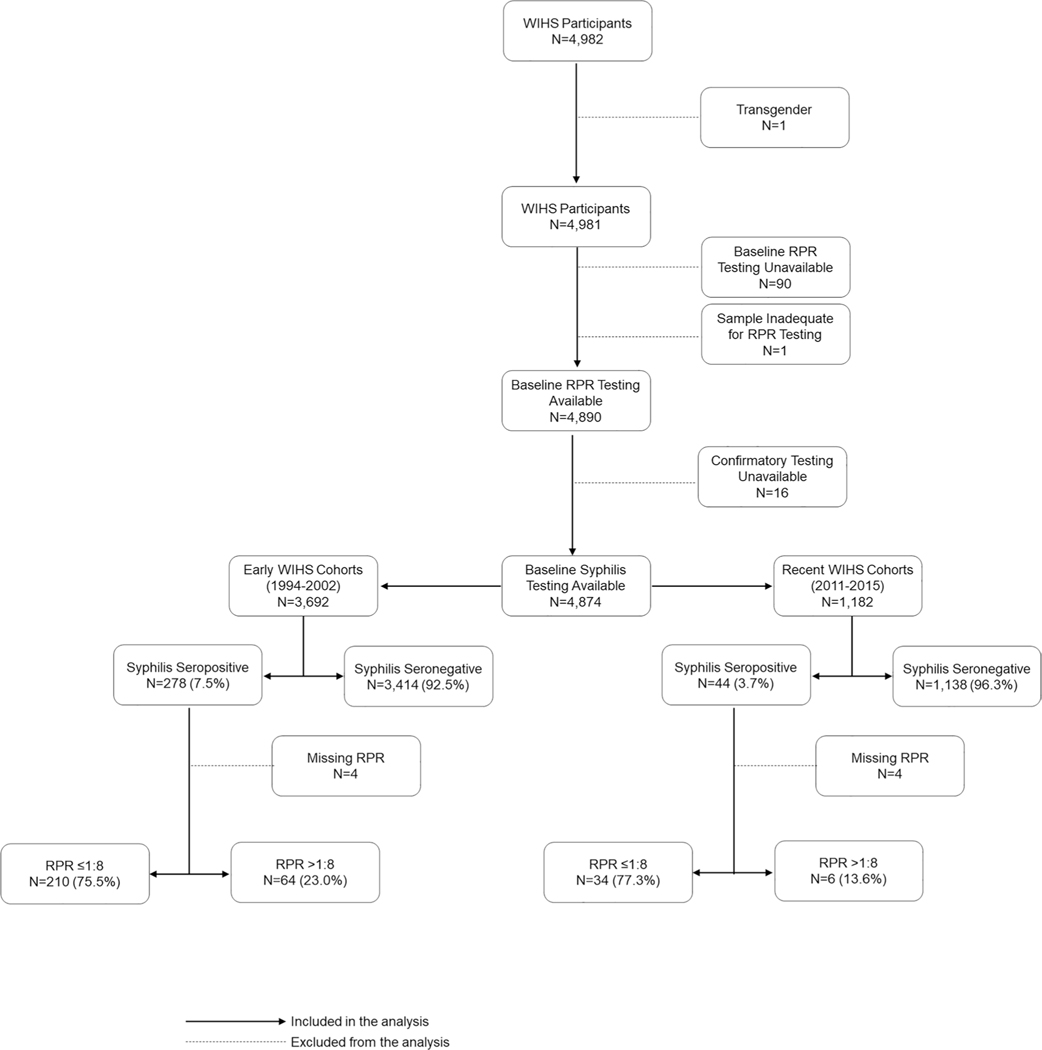

A total of 4982 women age 16–73 years old were enrolled in the multicentre WIHS cohort between 1994 and 2015. Nearly all (98%) were tested for syphilis. There were 3692 women enrolled between 1994 and 2002 (the early cohort) and 1182 women enrolled between 2011 and 2015 (the recent cohort) (figure 1). Treponemal confirmatory testing varied by site and included fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (55%), microhaemagglutination assay for Treponema pallidum antibodies (32%), Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (7%), Treponema pallidum haemagglutination (1%) and enzyme immunoassay (5%). The seroprevalence of syphilis at enrolment was 7.5% in the early cohort and 3.7% in the recent cohort (p<0.001) (figure 1). Of women with syphilis with an RPR titre available, RPR titres were >1:8 in 64/274 women (23%) in the early cohort and 6/40 women (15%) in the recent cohort (figure 1). The seroprevalence of syphilis at enrolment was 7.4% and 4.4% among women with and without HIV infection, respectively (p<0.001) (online supplemental figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for study participants according to baseline syphilis testing and cohort. RPR, rapid plasma reagin; WIHS, Women’s Interagency HIV Study.

Baseline characteristics for women enrolled in the early cohorts are shown in table 1. Women with syphilis in the early cohort were more likely to be black (73% vs 56%), HIV-positive (84% vs 73%) and low income (77% vs 59%) compared with women without syphilis (all p<0.05). Unadjusted and adjusted models for syphilis in the early cohort are shown in table 1. In the crude model for the early cohort, syphilis was associated with age category, black race, low income, self-reported history of syphilis, HIV infection, HCV antibody positivity, drug use, problem alcohol use, >10 lifetime sex partners and transactional sex (all p<0.05). Ethnicity and current pregnancy were not associated with syphilis seroprevalence in the crude model for the early cohort. In the adjusted model (n=3562), black race (aPOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.6), low income (aPOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 2.7), HCV Ab+ (aPOR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.0), HIV (aPOR 1.8, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.6), drug use (aPOR 3.3, 95% CI 1.9 to 5.4) and >100 lifetime sex partners (aPOR 2.9, 95% CI 2.0 to 4.2) were associated with an increased risk of prevalent syphilis. Factors not associated with syphilis seroprevalence include age category 16–29 years (aPOR 1.2, 95% CI 0.6 to 2.6), 30–39 years (aPOR 1.3, 95% CI 0.7 to 2.6) and 40–49 years (aPOR 0.6, 95% CI 0.3 to 1.3) when compared with women 50 years of age or older and having 11–100 lifetime sexual partners (aPOR 1.2, 95% CI 0.9 to 1.6) compared with ≤10 lifetime sexual partners (table 1).

Table 1.

Association between participant characteristics and syphilis status in women in the early cohort (n=3692)

| Variable | Syphilis negative n=3414 (92.5%) | Syphilis positive n=278 (7.5%) | Syphilis seroprevalence crude POR (95% CI) | P value | Syphilis seroprevalence adjusted POR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age category (years) | 0.007 | 0.001 | ||||

| 16–29 | 962 (28.2) | 64 (23.0) | 0.90 (0.45 to 1.80) | 0.776 | 1.22 (0.59 to 2.56) | 0.591 |

| 30–39 | 1521 (44.6) | 154 (55.4) | 1.38 (0.71 to 2.67) | 0.344 | 1.31 (0.66 to 2.62) | 0.443 |

| 40–49 | 795 (23.3) | 50 (18.0) | 0.86 (0.42 to 1.73) | 0.663 | 0.64 (0.31 to 1.32) | 0.228 |

| ≥50 | 136 (4.0) | 10 (3.6) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black race | 1925 (56.4) | 203 (73.0) | 2.09 (1.59 to 2.75) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.46 to 2.60) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 914 (26.8) | 61 (21.9) | 0.77 (0.57 to 1.03) | 0.080 | ||

| Single relationship status | 2155 (63.2) | 183 (66.1) | 1.13 (0.87 to 1.47) | 0.347 | ||

| Low Income (<$12 000/year) | 1934 (58.5) | 202 (76.8) | 2.35 (1.75 to 3.15) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.48 to 2.73) | <0.001 |

| Self-reported history of syphilis | 29 (0.85) | 48 (17.3) | 24.6 (15.2 to 39.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Currently pregnant | 69 (2.0) | 10 (3.6) | 1.82 (0.93 to 3.58) | 0.082 | ||

| Medical comorbidities | ||||||

| HIV infection | 2501 (73.3) | 232 (83.5) | 1.84 (1.33 to 2.55) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.30 to 2.60) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis C (antibody positive) | 1072 (31.4) | 131 (47.3) | 1.96 (1.53 to 2.51) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.08 to 1.96) | 0.013 |

| Drug and alcohol use | ||||||

| Problem alcohol use (>7 drinks/week) | 384 (11.3) | 50 (18.0) | 1.69 (1.22 to 2.34) | 0.001 | ||

| Active or prior drug use | 2548 (74.8) | 259 (93.2) | 4.60 (2.87 to 7.38) | <0.001 | 3.25 (1.94 to 5.44) | <0.001 |

| Active or prior IDU | 1021 (29.9) | 109 (39.2) | 1.51 (1.18 to 1.94) | 0.001 | ||

| Sexual history | ||||||

| Number of lifetime sex partners | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| >100 | 215 (6.3) | 50 (18.0) | 3.71 (2.62 to 5.27) | <0.001 | 2.88 (1.98 to 4.19) | <0.001 |

| 11–100 | 866 (25.4) | 82 (29.5) | 1.51 (1.14 to 2.00) | 0.004 | 1.18 (0.87 to 1.60) | 0.296 |

| 0–10 | 2332 (68.3) | 146 (52.5) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Transactional sex (ever) | 1065 (31.3) | 179 (64.6) | 4.00 (3.10 to 5.18) | <0.001 | ||

Values expressed as n (% of non-missing results); reference levels for variables: age (≥50 years old), race (white, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander and other), ethnicity (non-Hispanic), relationship status (married/living with a partner), income (US$≥12 000), self-reported history of syphilis (no self-reported history of syphilis), currently pregnant (not pregnant), HIV status (HIV negative); hepatitis C (negative), problem alcohol use (≤7 drinks a week), active or historical use of cocaine/crack, heroin, methamphetamines or other non-IDU drugs (no active or historical drug use); number of lifetime sex partners (0–10 lifetime partners) and history of transactional sex (reporting never having sex for drugs, money or shelter); missing data: income (n=123, 3.3%), self-reported history of syphilis (n=3, 0.1%), currently pregnant (n=32, 0.9%), marital status (n=7, 0.2%), HCV antibody (n=3, 0.1%), alcohol use (n=83, 2.3%), transactional sex (n=16, 0.4%), active or historical use of cocaine/crack, heroin, methamphetamines or other non-IDU drugs (n=6, 0.2%) and number of lifetime sex partners (n=1, <0.1%). In the multivariable model for women enrolled in the early WIHS cohorts (1994–2002), there were 3692 women of which data for 3562 were used. Backward selection with an alpha level of removal of 0.2 was used, and problem alcohol use was removed from the model.

IDU, injection drug use; POR, prevalence OR; WIHS, Women’s Interagency HIV Study.

Baseline characteristics for women enrolled in the recent cohort are shown in table 2. Among women in the recent cohort, women with syphilis were older and more likely to be low income, have HCV antibody, to report problem alcohol use, drug use and transactional sex compared with those without syphilis (all p<0.05) (table 2). In the crude model for the recent cohort, syphilis was associated with age, low income, self-reported history of syphilis, HCV antibody positivity, problem alcohol use, drug use and transactional sex history (all p<0.05) (table 2). Ethnicity and current pregnancy were not associated with syphilis seroprevalence in the crude model for the recent cohort. In the adjusted model (n=1134), age categories of 30–39 years (aPOR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.6) and 40–49 years (aPOR 0.5, 95% CI 0.2 to 1.0) were associated with reduced risk of syphilis versus the ≥50-year-old referent category, while hepatitis C antibody positivity (aPOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.0 to 4.1) and problem alcohol use (aPOR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.4) were associated with syphilis (table 2). Factors not associated with syphilis seroprevalence include age category 16–29 years compared with ≥50 years of age (aPOR 0.2, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.6), low income (aPOR 2.1, 95% CI 0.97 to 4.5) and HIV infection (aPOR 1.4, 95% CI 0.7 to 2.9).

Table 2.

Association between participant characteristics and syphilis status in women in the recent cohort (n=1182)

| Variable | Syphilis negative, n=1138 (96.3%) | Syphilis positive, n=44 (3.7%) | Syphilis seroprevalence crude POR (95% CI) | P value | Syphilis seroprevalence adjusted POR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age category (years) | <0.001 | 0.011 | ||||

| 16–29 | 84 (7.4) | 1 (2.3) | 0.14 (0.02 to 1.08) | 0.059 | 0.21 (0.03 to 1.63) | 0.136 |

| 30–39 | 325 (28.6) | 3 (6.8) | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.37) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.05 to 0.56) | 0.004 |

| 40–49 | 414 (36.4) | 14 (31.8) | 0.41 (0.21 to 0.80) | 0.009 | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.97) | 0.042 |

| ≥50 | 315 (27.7) | 26 (59.1) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black race | 935 (82.2) | 40 (90.9) | 2.17 (0.77 to 6.14) | 0.144 | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 96 (8.4) | 1 (2.3) | 0.25 (0.03 to 1.85) | 0.176 | ||

| Single relationship status | 778 (69.2) | 30 (68.2) | 0.96 (0.50 to 1.83) | 0.891 | ||

| Low income (<$12 000/year) | 631 (57.6) | 33 (78.6) | 2.70 (1.28 to 5.69) | 0.009 | 2.09 (0.97 to 4.49) | 0.059 |

| Self-reported history of syphilis | 5 (0.4) | 2 (4.6) | 10.8 (2.03 to 57.2) | 0.005 | ||

| Currently pregnant | 11 (1.0) | 0 (0) | * | * | ||

| Medical comorbidities | ||||||

| HIV infection | 825 (72.5) | 34 (77.3) | 1.29 (0.63 to 2.64) | 0.487 | 1.39 (0.66 to 2.93) | 0.390 |

| Hepatitis C (antibody positive) | 146 (12.9) | 17 (38.6) | 4.27 (2.27 to 8.03) | <0.001 | 2.05 (1.01 to 4.14) | 0.046 |

| Drug and alcohol use | ||||||

| Problem alcohol use (>7 drinks/week) | 203 (17.8) | 16 (36.4) | 2.63 (1.40 to 4.95) | 0.003 | 2.21 (1.12 to 4.37) | 0.023 |

| Active or prior drug use | 786 (69.1) | 38 (86.4) | 2.84 (1.19 to 6.77) | 0.019 | ||

| Active or prior injection drug use | 105 (9.2) | 6 (13.6) | 1.55 (0.64 to 3.76) | 0.329 | ||

| Sexual history | ||||||

| Number of lifetime sex partners | 0.687 | |||||

| >100 | 83 (7.3) | 2 (4.6) | 0.65 (0.15 to 2.84) | 0.569 | ||

| 11–100 | 483 (42.6) | 21 (47.7) | 1.18 (0.64 to 2.18) | 0.603 | ||

| 0–10 | 569 (50.1) | 21 (47.7) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Transactional sex (ever) | 410 (36.0) | 24 (54.6) | 2.13 (1.16 to 3.90) | 0.014 | ||

Values expressed as n (% of non-missing results); reference levels for variables: age (≥50 years old), race (white, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander and other), ethnicity (non-Hispanic), relationship status (married/living with a partner), income (US$≥12 000), self-reported history of syphilis (no self-reported history of syphilis), currently pregnant (not pregnant), relationship status (married/living with a partner), income (US$≥12 000); HIV status (HIV negative); hepatitis C (negative), problem alcohol use (≤7 drinks a week); active or historical use of cocaine/crack, heroin, methamphetamines or other non-IDU drugs (no active or historical drug use); number of lifetime sex partners (0–10 lifetime partners); and history of transactional sex (reporting never having sex for drugs, money or shelter); missing data: income (n=45, 3.8%), self-reported history of syphilis (n=1, 0.1%), marital status (n=13, 1.1%), HCV antibody (n=2, 0.2%), alcohol use (n=1, 0.1%) and number of lifetime sex partners (n=3, 0.3%). In the multivariable model for women in the recent WIHS cohorts (2011–2015), there were 1182 women of which data for 1134 were used. Backward selection with an alpha level of removal of 0.2 was used; and the following variables were removed from the model: race, active or historical use of cocaine/crack, heroin, methamphetamines or other non-IDU drugs and lifetime number of sex partners.

No outcomes for crude model.

IDU, injection drug use; POR, prevalence OR; WIHS, Women’s Interagency HIV Study.

A secondary analyses of syphilis prevalence stratified by HIV status was performed (online supplemental tables 1, 2). There were 3592 women (74%) with HIV and 1282 women (26%) without HIV infection. Multivariable models adjusted for age, race, income, cohort, HCV infection, alcohol use, drug use and lifetime sex partners. Among women with HIV (n=3405), women age 40–49 years had a lower risk of syphilis (aPOR 0.4, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.7) compared with women≥50 years old. Also, among women with HIV, those in the recent cohort (aPOR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.7) had a lower risk of syphilis compared with women in the early cohort. Black race (aPOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.2), low income (aPOR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4 to 2.7), HCV antibody (aPOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.2), active or prior drug use (aPOR 3.7, 95% CI 2.2 to 6.3) and >100 sexual partners versus 0–10 partners (aPOR 2.6, 95% CI 1.8 to 3.8) were associated with syphilis seroprevalence among women with HIV (online supplemental table 1). Among women without HIV (n=1213), women in the younger age category of 16–29 years (aPOR 0.1, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.5) compared with age ≥50 and those in the recent cohort (aPOR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.7) had a reduced risk of syphilis, while black race (aPOR 3.8, 95% CI 1.7 to 8.7) and lower income (aPOR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1 to 4.1) were associated with infection (online supplemental table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of 4874 women enrolled in a multisite US cohort study between 1994 and 2015, the prevalence of syphilis at enrolment was 6.6%. This is ninefold higher than population-level estimates of 0.7% among US women according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 2001 to 2004.19 Our study findings support CDC guidelines for universal syphilis screening among women living with HIV and at-risk for HIV infection due to their elevated risk.20 21 Risks for syphilis acquisition in women during the 1990s epidemic included black race, drug use, transactional sex and barriers to care.7 22 23 In this study, we found that age, hepatitis C infection and problem alcohol use were associated with prevalent syphilis in women in the recent cohort.

Younger age in the early cohort and older age in the recent cohorts were relevant, but the significance of specific age categories in this cross-sectional analysis is imprecise since age at acquisition is unspecified. Elevated RPR titres (>1:8) were more common in the early WIHS cohort compared with the recent cohort. Specifically, there is evidence of fewer early syphilis infections among the recent cohort as there were five (1.6%) women with titers ≥1:32, while, there were 43 (13.4%) women with titres ≥1:32 in the early cohort. Without additional information about staging, both the age association and RPR titre categories are suggestive of a potential cohort effect. Our interpretation is that some women in the recent cohort (mean age 43 years) may have had persistently reactive low-titre RPR and treponemal antibodies due to prior infection24; however, data regarding prior treatment is not available for individual women in our analysis. Thus, we cannot assume that there was a proportion of serological non-responders or serofast patients, although it is a common outcome of syphilis infection. In a systematic review, the proportion of adults with serological non-response (<4-fold decline in RPR 12 months after syphilis treatment) averaged 11% and the proportion with serofast (persistent low-titre RPR) ranged from 35% to 44%.24

Problem alcohol use17 was more commonly reported among women with syphilis, and it was more commonly reported in the recent cohort than in the early cohort (36% vs 18%). This is consistent with other studies suggesting a link between alcohol use, risk behaviours and STI/HIV acquisition risk in women.25 26 In one study, women who consumed alcohol in the past 30 days were more likely to have multiple sexual partners, higher risk sex partners and STI positivity.25 Among 1857 US women with HIV, problem drinking (>7 drinks/week) was associated with having more sex partners.26

Consistent with other studies, the presence of HCV antibody was associated with syphilis in the early and recent cohort of WIHS.7 A retrospective analysis of incident syphilis among women enrolled in the US Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems cohort found that independent predictors of incident syphilis included hepatitis C infection, IDU, black race and more recent entry to care.

Low income and a high number of sexual partners were also associated with syphilis in the early cohort, as seen in previous studies.27 28 Marked racial inequities were noted among women in the early cohort but not the recent cohort. Differential STI prevalence by region, structural racism and sexual networks may explain some of the disproportionate impact of syphilis on black women.29 30 We were unable to comment on geographic region of residence or regional syphilis rates among partners in this study due to collinearity with enrolment timing. The intersectionality between gender-based inequity, racism and low income likely results in an increased vulnerability to STIs among women.31 These are critical data to collect to inform future studies.

Syphilis screening rates in HIV clinics are often insufficient: only 49% of sexually active women living with HIV were tested at least once for syphilis in the past 12 months. In a study of women living with HIV in California, 51% of Medicare enrollees and 68% of Medicaid enrollees were tested for syphilis in 2010.33 Our study findings imply that all women living with HIV and at-risk for HIV may need syphilis screening since: (1) infection is often asymptomatic with a painless primary lesion at the site of exposure and (2) rates among women and infants in the USA continue to rise.32

The current study has important limitations. Since routine syphilis testing for WIHS participants was only performed at baseline, we were not able to determine incident infection or recent acquisition of syphilis among participants. Also, WIHS participants may not be representative of younger women living with HIV or at-risk for HIV infection. Syphilis seropositivity at enrolment cannot distinguish between active infection, recently treated infection or the serofast state (ie, persistent reactivity) in the absence of follow-up serologic testing. However, enrolment of US participants over multiple waves during the >20 year span of the study is useful.14 The diversity of WIHS cohort enrollees from women who were engaged and not engaged in medical care mirrors the HIV epidemic. We were unable to analyse geographic differences since the southern sites were only added to the WIHS cohort in 2013.14

In conclusion, this study provides useful estimates of syphilis seropositivity and correlates of infection in women living with HIV and at-risk for HIV infection in the USA. Factors associated with syphilis in the current era were similar among women regardless of HIV status. In the midst of a worsening epidemic in the USA, new interventions to increase syphilis screening and treatment in women of all ages are needed. Women with hepatitis C antibody positivity and problem alcohol use may benefit from novel interventions designed to improve syphilis screening and prevention.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

Syphilis prevalence was elevated among women living with HIV and at-risk of HIV in a multisite US cohort study.

Hepatitis C seropositivity was consistently associated with infection in women in both early and recent cohorts.

Among women with and without HIV, black race and low income were associated with increased risk of syphilis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ashutosh Tamhane, MD, PhD, MSPH, for his careful review and suggestions on the content of this manuscript. Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, now the MACS/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Van Der Pol receives research support, consulting fees and/or honorarium from the following: Abbott Molecular, BD Diagnostics, Binx Health, BioFire Diagnostics, Hologic, Rheonix, Roche and SpeeDx; Dr. Marrazzo receives research support and/or consulting fees from BD Diagnostics, Gilead, and BioFire Diagnostics. Dr. Adimora has received research funding from Gilead and consulting fees from Merck, Viiv, and Gilead. Dr. Sheth has received research grants from Gilead sciences unrelated to the published work.

Funding

MWCCS (principal investigators): Atlanta CRS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth and Gina Wingood), U01-HL146241; Baltimore CRS (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), U01-HL146201; Bronx CRS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-HL146204; Brooklyn CRS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-HL146202; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D’Souza, Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-HL146193; Chicago-Cook County CRS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-HL146245; Chicago-Northwestern CRS (Steven Wolinsky), U01-HL146240; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California CRS (Bradley Aouizerat, Phyllis Tien and Jennifer Price), U01-HL146242; Los Angeles CRS (Roger Detels), U01-HL146333; Metropolitan Washington CRS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-HL146205; Miami CRS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl and Deborah Jones), U01-HL146203; Pittsburgh CRS (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), U01-HL146208; UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Jodie Dionne-Odom and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-HL146192; UNC CRS (Adaora Adimora), U01-HL146194. The MWCCS is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional cofunding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development, National Institute On Aging, National Institute Of Dental & Craniofacial Research, National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases, National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke, National Institute Of Mental Health, National Institute On Drug Abuse, National Institute Of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and in coordination and alignment with the research priorities of the National Institutes of Health, Office of AIDS Research. MWCCS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), P30-AI-050409 (Atlanta CFAR), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR) and P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR). Project support was also provided by 1K23HD090993 (Jodie Dionne-Odom).

Footnotes

Competing interests As a group, we have no other conflicts of interest to report.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval This study received institutional review board approval from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (IRB-300001349).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Handling editor Claudia S Estcourt

Data availability statement

There are no additional unpublished data available. Readers should contact KJA with any inquiries.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kojima N, Klausner JD. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2018;5:24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seale A, Broutet N, Narasimhan M. Assessing process, content, and politics in developing the global health sector strategy on sexually transmitted infections 2016–2021: implementation opportunities for policymakers. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Centers for disease C, prevention. sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: US preventive services Task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;315:2321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hook EW. Syphilis. The Lancet 2017;389:1550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterman TA, Heffelfinger JD, Swint EB, et al. The changing epidemiology of syphilis. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:S4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dionne-Odom J, Westfall AO, Dombrowski JC, et al. Intersecting epidemics: incident syphilis and drug use in women living with HIV in the United States (2005–2016). Clin Infect Dis 2019:ciz1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice CE, Maierhofer C, Fields KS, et al. Beyond anal sex: sexual practices of men who have sex with men and associations with HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. J Sex Med 2016;13:374–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesson HW, Patel CG, Gift TL, et al. Trends in selected measures of racial and ethnic disparities in gonorrhea and syphilis in the United States, 1981–2013. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:661–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owusu-Edusei K, Chesson HW, Leichliter JS, et al. The association between racial disparity in income and reported sexually transmitted infections. Am J Public Health 2013;103:910–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2019: 24–31. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/79370 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:456–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018: 94–110. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/59237 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, et al. Cohort profile: the women’s Interagency HIV study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:393–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The women’s Interagency HIV study. WIHS collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology 1998;9:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The women’s Interagency HIV study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005;12:1013–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NIAAA: National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. Rockville, MD: NIAAA Publications Distribution Center, 2005. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/guide.pdf. (Accessed 3/2/2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Nickleach DC, Zhang C, et al. Carrying out streamlined routine data analyses with reports for observational studies: introduction to a series of generic SAS ® macros. F1000Res 2018;7:1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gottlieb SL, Pope V, Sternberg MR, et al. Prevalence of syphilis seroreactivity in the United States: data from the National health and nutrition examination surveys (NHANES) 2001–2004. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:507–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chesson HW, Heffelfinger JD, Voigt RF, et al. Estimates of primary and secondary syphilis rates in persons with HIV in the United States, 2002. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koblin BA, Grant S, Frye V, et al. HIV sexual risk and Syndemics among women in three urban areas in the United States: analysis from HVTN 906. J Urban Health 2015;92:572–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolfs RT, Goldberg M, Sharrar RG. Risk factors for syphilis: cocaine use and prostitution. Am J Public Health 1990;80:853–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunn RA, Montes JM, Toomey KE, et al. Syphilis in San Diego County 1983–1992: crack cocaine, prostitution, and the limitations of partner notification. Sex Transm Dis 1995;22:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seña AC, Zhang X-H, Li T, et al. A systematic review of syphilis serological treatment outcomes in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected persons: rethinking the significance of serological non-responsiveness and the serofast state after therapy. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seth P, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, et al. Alcohol use as a marker for risky sexual behaviors and biologically confirmed sexually transmitted infections among young adult African-American women. Womens Health Issues 2011;21:130–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutton HE, Lesko CR, Li X, et al. Alcohol use patterns and subsequent sexual behaviors among women, men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women engaged in routine HIV care in the United States. AIDS Behav 2019;23:1634–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Wagoner NJ, Harbison HS, Drewry J, et al. Characteristics of women reporting multiple recent sex partners presenting to a sexually transmitted disease clinic for care. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:210–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smock L, Caten E, Hsu K, et al. Economic disparities and syphilis incidence in Massachusetts, 2001–2013. Public Health Rep 2017;132:309–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutfi K, Trepka MJ, Fennie KP, et al. Racial residential segregation and risky sexual behavior among non-Hispanic blacks, 2006–2010. Soc Sci Med 2015;140:95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/Ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis 1999;26:250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harling G, Subramanian S, Bärnighausen T, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in sexually transmitted infections among young adults in the United States: examining the interaction between income and race/ethnicity. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:575–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flagg EW, Weinstock HS, Frazier EL, et al. Bacterial sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected patients in the United States: estimates from the medical monitoring project. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42:171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landovitz RJ, Gildner JL, Leibowitz AA. Sexually transmitted infection testing of HIV-positive Medicare and Medicaid enrollees falls short of guidelines. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

There are no additional unpublished data available. Readers should contact KJA with any inquiries.