Abstract

Background

Australian national mental health policy outlines the need for a nationally coordinated strategy to address stigma and discrimination, particularly towards people with complex mental illness that is poorly understood in the community. To inform implementation of this policy, this review aimed to identify and examine the effectiveness of existing Australian programs or initiatives that aim to reduce stigma and discrimination.

Method

Programs were identified via a search of academic databases and grey literature, and an online survey of key stakeholder organisations. Eligible programs aimed to reduce stigma towards people with complex mental illness, defined as schizophrenia, psychosis, personality disorder, or bipolar disorder; or they focused on nonspecific ‘mental illness’ but were conducted in settings relevant to individuals with the above diagnoses, or they included the above diagnoses in program content. Key relevant data from programs identified from the literature search and survey were extracted and synthesized descriptively.

Results

We identified 61 programs or initiatives currently available in Australia. These included face-to-face programs (n = 29), online resources (n = 19), awareness campaigns (n = 8), and advocacy work (n = 5). The primary target audiences for these initiatives were professionals (health or emergency), people with mental illness, family or carers of people with mental illness, and members of the general population. Most commonly, programs tended to focus on stigma towards people with non-specific mental illness rather than on particular diagnostic labels. Evidence for effectiveness was generally lacking. Face-to-face programs were the most well-evaluated, but only two used a randomised controlled trial design.

Conclusions

This study identified areas of strength and weakness in current Australian practice for the reduction of stigma towards people with complex mental illness. Most programs have significant input from people with lived experience, and programs involving education and contact with a person with mental illness are a particular strength. Nevertheless, best-practice programs are not widely implemented, and we identified few programs targeting stigma for people with mental illness and their families, or for culturally and linguistically diverse communities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and LGBTIQ people. These can inform stakeholder consultations on effective options for a national stigma and discrimination reduction strategy.

Keywords: Mental illness, Stigma, Discrimination, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, Psychosis, Personality disorder

Background

Stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental illness are prevalent in Australia [1]. While there have been some improvements in community understanding of common mental illnesses (particularly depression and anxiety), there is still widespread misunderstanding and ignorance [2, 3]. In particular, complex mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and personality disorders, tend to be poorly understood and attitudes are much less positive. The low prevalence of these mental illnesses means that most people do not personally know someone with these illnesses, so they are more likely to rely on stereotypical attitudes. Common stereotypes about people with complex or severe mental illness include are that they are dangerous, unpredictable, lack competence to look after themselves, and have little chance of recovery [4]. Negative attitudes lead to discriminatory behaviour, primarily avoidance and exclusion, as people seek to avoid the risks of associating with people with mental illness. This can affect a person with mental illness’ opportunities for finding and keeping a job and their relationships with friends, family, and romantic partners [5]. This discrimination can increase feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness about the future, and suicidality [6, 7]. Reducing stigma and discrimination is therefore critical to improving the wellbeing of people with mental illness and their carers.

Reducing stigma towards people with complex mental illness is a key priority area of Australian national mental health policy. The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan (the Fifth Plan), released in 2017, focuses on stigma reduction as one of eight priorities for mental health reform [8]. It outlines the need for a nationally coordinated strategy to address stigma and discrimination and requires that the Australian government build on existing initiatives, including the evidence base of what works in relation to reducing stigma and discrimination. A recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials evaluated the evidence of interventions to reduce stigma towards people with severe mental illness (schizophrenia, psychosis or bipolar disorder) [9]. This found that both contact- and education-based interventions showed small-to-medium immediate reductions in stigma, but there was limited evidence on longer-term effects. There was also little guidance on what components of interventions are needed for effective stigma reduction. Furthermore, only two interventions had been evaluated in Australia, one of which was only available as part of a university experiment. While the review focused on high-quality randomised trial evidence from an international perspective, there is a need to understand what programs and initiatives are currently available in Australia specifically, and whether they have any evidence of effectiveness, even if not from randomised trials. This information is critical to inform options for a national stigma and discrimination reduction strategy as part of implementation of the Fifth Plan in Australia.

The aim of this study was therefore to (1) identify existing programs or initiatives run by Australian lived experience groups and other key non-government organisations that aim to reduce stigma and discrimination and promote positive behaviours towards people with complex mental illness; and (2) examine the evidence of effectiveness for these programs.

Method

In order to review existing Australian stigma and discrimination reduction initiatives and their evidence of effectiveness, we conducted literature searches and surveyed lived experience groups and key non-government organisations (NGOs).

Program inclusion/exclusion criteria

Programs were eligible if they (1) aimed to reduce stigma towards people with complex mental illness, defined as schizophrenia, psychosis, personality disorder, or bipolar disorder; (2) they focused on nonspecific ‘mental illness’ but were conducted in settings relevant to individuals with the above diagnoses (e.g., public mental health services, with mental health nurses); (3) they included the above diagnoses in program content; (4) stigma reduction was explicitly mentioned as a focus, or was implied (e.g. by including a stigma measure as an outcome or by focusing on improving understanding or knowledge of severe mental illness). All kinds of stigma were eligible, including personal or public stigma, perceived stigma, desire for social distance, discrimination, self/internalised stigma, and beliefs about recovery or prognosis.

Programs were ineligible if they (1) focused on common mental disorders (depression or anxiety), suicide, eating disorders, dementia, intellectual disability, PTSD, OCD, substance misuse or dual diagnoses; (2) aimed to improve mental health literacy or promote help-seeking without a specific focus on reducing stigma and discrimination; (3) were not conducted in Australia.

Literature search

A systematic search of the ‘grey’ and academic literature was conducted to identify Australian programs that aim to reduce stigma and discrimination.

Academic databases

For the academic databases we searched PubMed and PsycINFO, limited to studies published since 2009 to ensure that they were relevant to current practice. Literature search strategies were developed using medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words related to stigma and discrimination (see Additional file 1: Table S1). All study designs were eligible including quantitative (e.g. uncontrolled trials) and qualitative (e.g. participant interviews). A total of 652 studies were screened for eligibility.

These searches were supplemented by screening our results from a previous literature review [9] to identify any reports that did not meet the inclusion criteria for that review (e.g. due to lack of a control group) but met the inclusion criteria for this review.

‘Grey’ literature

The ‘grey’ literature search was conducted using Google Australia. The purpose of the ‘grey’ literature search was to identify eligible programs and to identify organisations with potential programs to be invited to participate in the survey.

Separate searches were conducted using the following key search terms: bipolar, personality disorder, (schizophrenia OR psychosis), (mental illness OR mental health), (stigma OR discrimination), and Australia. For each search, the first 50 websites were retrieved, and duplicates were excluded. The remaining websites were reviewed for relevant information and any links from these websites were followed when they were thought to contain useful information.

We also systematically searched websites of lived experience advocacy and support groups and other key NGOs to identify programs and evaluation reports. Overall, a total of 267 websites were searched for eligible programs.

Survey of lived experience groups and key NGOs

We conducted an online survey of lived experience advocacy and support groups and key NGOs, inviting them to provide details of their programs and associated evaluation or evidence of effectiveness.

Survey participants

Survey participants comprised key informants in Australian organisations of any type that have programs that aim to reduce stigma and discrimination and promote positive behaviours. These were reached in 4 key ways: (1) An email sent to organisations identified in web searches (see above); (2) Information about the study with a link to the survey included in the following organisations’ newsletters: Mental Health Australia, Mental Health Victoria, and Mental Health Coordinating Council; (3) An email sent to all voting and non-voting members of Mental Health Australia. Mental Health Australia is the peak, national non-government organisation representing the interests of the Australian mental health sector. Its members include national organisations representing consumers, carers, special needs groups, clinical service providers, public and private mental health service providers, researchers and state/territory community mental health peak bodies; (4) Snowball sampling—survey respondents were encouraged to pass on details of the project to other organisations with programs that met the inclusion criteria. In total we invited 177 organisations to participate in the survey.

Survey content

Survey data were collected online using Qualtrics software with both multiple choice and open-ended questions. The survey included information such as location, target audience, type of program, program delivery mechanisms, program reach and source of funding. Organisations were able to provide information about multiple stigma-reduction programs, if relevant. Organisations were asked to provide any available evaluation or evidence of effectiveness. Participants provided informed consent before completing the survey. The survey opened 9th of December, 2019 and closed on 31st of January, 2020.

A concerted effort was made to obtain missing information about programs from those identified in our searches and from completed surveys. Authors of academic papers were emailed to enquire about whether programs were still operating and to obtain information not reported in the scientific literature. Organisations were also sent reminder emails to undertake or finish completing the survey before it was closed.

Data analysis

Key relevant data from programs identified from the literature search and survey were extracted and synthesized descriptively and thematically. Level of evidence for each program was classified on a scale from 1–5, with 1 = no evaluation evidence, 2 = post survey feedback or qualitative interviews, 3 = one or more uncontrolled trials or repeated cross-sectional surveys, 4 = one or more controlled trials, 5 = one or more randomised controlled trials.

Results

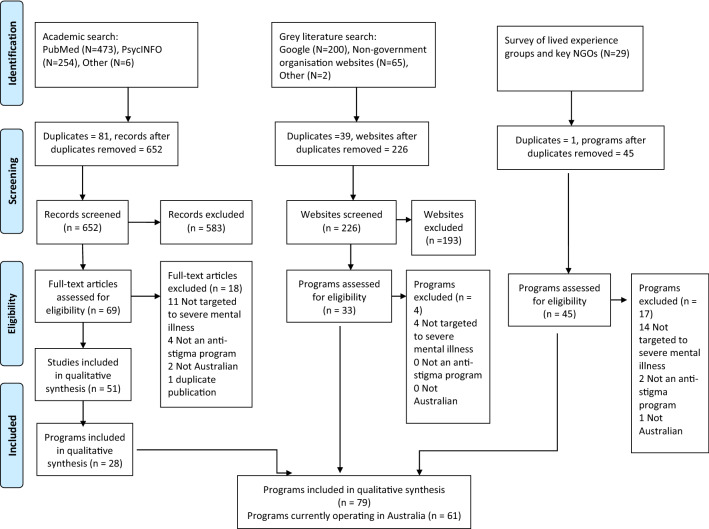

Results from our survey of organisations in the mental health sector, grey literature search, and search of academic literature, identified 79 Australian programs or initiatives. These 79 programs were described or evaluated in 108 resources (as some programs were included in multiple academic papers). However, some of the identified programs did not appear to be currently available, based on information from program authors or a web search for further information. Programs that were one-offs conducted in the past, had ceased operating, or were experimental research studies not designed to be ongoing, are included in supplementary material (Tables 2 and 3). Excluding these programs left 61 programs currently operating in Australia. See Fig. 1 for a flow chart of the process of identifying eligible programs. These were further broken down into face-to-face programs (n = 29), community awareness campaigns (n = 8), programs or organisations undertaking advocacy for the rights of people with mental illness (advocacy programs, n = 5), and publicly-available online resources (n = 19).

Table 2.

Programs targeted to people with mental illness

| Program name | Organisation | Type of mental illness | Description | Anti-stigma component | Lived experience involvement | Number of program attendees | Where provided | Duration and reach | Funding | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Station [31] | The Station | Mental illness (non-specific) | Consumer-driven mental health service provides a safe and supportive environment, social connections, and activities for its members (those with a lived experience of mental illness). Aims to increase knowledge and skills for living | Contact: People recovering from a mental illness, their carers, and community members meet and conduct activities. Targets public stigma and self-stigma (self-worth) | People with LE involved in all aspects of service delivery and are part of the management committee | 50 people |

SA, regional/ rural |

Since 1998, N/R | State gov, earned income from members, donations | 2 |

| TasRec | Richmond Fellowship Tasmania | Mental illness (non-specific) | Recreation program provides a broad range of creative, social and skills building activities to help support mental wellbeing, build confidence and self-esteem, reduce isolation | Contact: The recreation program uses community events and art shows to convey experiences of mental illness and their capacity to lead meaningful lives whilst living with illness. Consumers are also provided the opportunity to increase their community engagement through participation in a wide variety of recreation activities, including physical, health, art, and so on. Targets public stigma and self-stigma (self-worth) | Recreation program is a process of co-design and collaboration between people with LE and staff within the programs. LE provide suggestions for activities and tasks they would like to participate in | Depends, small groups generally |

TAS, metro, regional/ rural |

5–10 years, 140 people | Commonwealth gov | 1 |

| Residential Accommodation | Richmond Fellowship Tasmania | Mental illness (non-specific), Bipolar disorder, Personality disorders, Psychosis, Schizophrenia | Residential accommodation for consumers living with mental health issues. RFT provide supports to consumers enabling them to reach greater independence, combat stigma, increase their personal advocacy, and live meaningful lives |

Other: Consumers are encouraged to envision the lives they wish to lead, and are provided examples of others leading meaningful lives, in the presence of mental illness. They are supported to access services, build social networks and lead meaningful lives despite stigma associated with mental ill-health Protest/Advocacy: Consumers are supported to build resilience and learn to advocate for themselves, as individuals navigating complex systems and situations |

People with LE participate in consumer advisory council and co-design and collaboration of service building | 25 people | TAS, metro, regional/rural, remote | More than 10 years, hundreds of participants | State gov, earned income from residents | 2 |

| Compeer (The Friendship Program) [32] | St Vincent de Paul Society Canberra | Mental illness (severe) | Friendship between a volunteer and person with lived experience who are matched based on age, gender, interests, hobbies and availability | Contact: Matches meet weekly for one year in safe environments using natural supports, sharing decision-making around activities, place, and time | Volunteer members of the public meet people with LE to develop friendships | 20–25 participants in 2020 | NSW, ACT, metro, regional/rural | Since 2009, 253 participants (ACT branch) | State gov (ACT) | 2 |

| Hearing Voices group [33] | Uniting Prahran | Schizophrenia | Monthly/fortnightly peer support group provides a welcoming space for voice hearers to share what it’s like to hear voices, learn new coping strategies and explore ways to make sense of voices and to change the relationship with voices | Other: The focus of the group is on support. Individuals are provided with the chance to share their experience of hearing voices and ideas of living with the voices | Facilitators are a person with LE and a ‘worker’ | N/R | VIC, metro | N/R | N/R | 1 |

| Information Nights | Borderline Personality Disorder Community | Borderline Personality Disorder | Information Nights are held three times a year to the BPD Community to provide information, a forum for discussion, and a sense of community |

Contact: Some information nights feature people with LE sharing their stories to reinforce the core techniques that build relationships and recovery Education: Information nights aim to replace stigma and discrimination with the hope and optimism that recovery is a realistic goal. Speakers present on topics of interest to the BPD Community Protest/Advocacy: Aim to increase capacity for advocacy through information and relationships with individuals in the community |

Facilitators are a person with LE, carer | Average of 28 over the last 5 events | VIC, metro | Since 2014, at least 167 people | Volunteer | 1 |

| My Recovery | Northern Territory Mental Health Coalition | Mental illness (non-specific) | A peer-led recovery program delivered by peers to other people with experiences of mental health challenges |

Contact: Peer led Education: Sessions cover information on mental illness, stigma and discrimination, recovery and discrimination, as well as skills-based capacity building in communication, recovery, and goal setting to promote long-term mental health and wellbeing Protest/Advocacy: Types of advocacy and local advocacy services are covered in sessions |

Facilitators are a person with LE | 12 to 15 people | NT, metro | 6–12 months, 30 people | Commonwealth gov | 2 |

| Being Herd [34] | Batyr | Mental illness (non-specific) | A workshop where young people are trained to share their stories to help breakdown the stigma associated with mental health | Other: 2-day workshop aims to enable people with lived experiences to tell their story in a constructive and empowering way. Highlights steps the person took to get support, what has helped in their recovery and how they can share their story in a safe and effective way for themselves and other young people | Facilitators are not reported | N/R | N/R | 700 + young people | N/R | 1 |

1 = No evaluation evidence, 2 = Post survey feedback or qualitative interviews, 3 = One or more uncontrolled trials or repeated cross-sectional surveys, 4 = One or more controlled trials, 5 = One or more randomised controlled trials

LE Lived Experience, N/R Not Reported

Table 3.

Programs targeted to family of people with mental illness

| Program name | Organisation | Type of mental illness | Description | Anti-stigma component | Lived experience involvement | Session length, facilitated by | Where provided | Duration and reach | Funding | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family and friends group | BPD Community | Borderline Personality Disorder | A group for carers to provide support and psychoeducation. Groups aim to share and learn how to support each other; to actively seek education and training to improve our relationships with our loved ones; to help ourselves and others; to create a safe environment; to reduce our sense of isolation; to accept our individual and joint responsibility to this purpose |

Contact: Groups are spent sharing stories over the month Education: One hour of the meeting is devoted to learning about relevant topics Protest/advocacy: The group provides the opportunity for individuals to build their own advocacy. It also provides the organisation with the capacity to speak on the behalf of participants |

Program is designed and developed by carers with LE | 2.5 h once a month, facilitated two carers | VIC, metro | Since 2015, 167 | Volunteers | Unclear |

| Journey to Recovery [35–38] | St Vincent’s Mental Health Service | Psychosis | Psychoeducation group program in a public adult mental health service for the families and friends of people experiencing early psychosis | Education: Provide support and information to assist coping and reduce isolation. Topics include What is psychosis, Recovering from psychosis, Medications, Early warning signs (relapse prevention), Community resources | None reported | 5 × 2-h sessions. Inpatient version is a single session. Facilitated by early psychosis senior clinicians | VIC, metro | Since 2009, N/R | State gov | 3 |

| Kookaburra Kids Camps and Activity Days | Australian Kookaburra Kids Foundation | Mental illness (non-specific) | Therapeutic recreation camps and activities for children who are living with a family member affected by mental illness | Education: Psychoeducation and basic coping skill-building is embedded into programs in a supported peer-group format to promote mental health literacy (including addressing misconceptions and myths about mental illness) and appropriate help-seeking | Designed by person with LE, co-design committee initiated in 2019. Delivery includes volunteers with LE | 2 × 1-h groups at camps; 15 min psycho-ed and activity at Activity Day. Facilitated by trained staff | ACT, NSW, NT, QLD, SA, VIC. Metro, regional/rural | More than 10 years, 3,000 + | Govt, donations and corporate / other sponsorships | Unclear |

1 = No evaluation evidence, 2 = Post survey feedback or qualitative interviews, 3 = One or more uncontrolled trials or repeated cross-sectional surveys, 4 = One or more controlled trials, 5 = One or more randomised controlled trials

LELived Experience, N/R Not Reported

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for identifying eligible programs

Face-to-face programs

Face-to-face programs were primarily targeted to four types of audiences: (1) Health professionals and health professional students; (2) People with a mental illness; (3) Family of people with a mental illness; (4) Members of the general population (particularly at school, university, or workplaces). See Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 for characteristics of each included program.

Table 1.

Programs targeted to health professionals, health professional students, emergency workers

| Program name | Organisation | Type of mental illness | Target audience | Program description | Anti-stigma component | Lived experience involvement | Session length, facilitated by | Where provided | Duration and reach | Funding | Level of evidencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery Camp [14–17] | Recovery Camp | Mental illness (non-specific) | Nursing students | A non-traditional placement for nursing students. Health students and people with a lived experience of mental illness attend a recreation camp, participating in an adventure activities program in the Australian bush | Contact: Lived experience attendees are encouraged to share their stories related to mental health and recovery with students. Everyone at camp is of equal status and contact is outside an acute setting (recovery focused) | LE person was involved in program development and delivery. Previous attendees with LE are involved in designing future camps and choosing camp activities | 5 days, 4 nights. Facilitated by registered nurses. Camps of 40–130 people, including 40 students, 40 people with lived experience, 5 nurse facilitators, several other staff | NSW, metropolitan | Since 2013. 800 students, 690 lived experience | Earned income from universities | 4 |

| Recovery for mental health nursing practice [18–21] | School of Nursing and Midwifery, Central Queensland University | Mental illness (non-specific) | Nursing students | A nursing subject ‘Recovery for mental health nursing practice’ introduces students to a recovery approach to mental health care | Contact: Subject is taught by an academic with lived experience | LE person was responsible for all aspects of the subject (e.g. development of content and appropriate resources, writing and examining the assessment tasks) | N/R. Subject taught by nurse with lived experience | QLD, regional/ rural | N/R | N/R | 2 |

| Remind Training and Education [22–24] | Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Sydney | Schizophrenia, depression | Pharmacy students | Pharmacy students attend a tutorial with trained mental health consumer educators, receive a series of mental health lectures and undertake supervised weekly placements in the community pharmacy setting | Contact: Consumer educators discuss their history with mental illness, the medications they take, ways of coping with their illness, the important role that pharmacists need to play in supporting people with mental illnesses, and how they were real people who led normal lives despite their illness. Students given opportunity to interview the educators during the tutorial | Trained mental health consumer educators from the Schizophrenia Fellowship of NSW participate in each session | Contact session is 2 h. Facilitated by pharmacy tutors | NSW, metropolitan | Since 2010, approx. 2,500 students | N/R | 3 |

| Collaborative Recovery Training Program (CRTP) [25, 26] | Illawarra Institute for Mental Health, University of Wollongong | Severe and persistent mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia | Health professionals | Involves training in recovery concepts and skills supporting consumers’ abilities to set, pursue and attain personal goals | Education: Aims to improve mental health workers’ attitudes towards prospect of recovery | N/R | 2-day training, facilitator not reported |

NSW, regional/ rural |

N/R | N/R | 3 |

| Managing Mental Health Emergencies short course [27] | Australian Rural Nurses and Midwives | Range of disorders including psychosis, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder | Rural and remote health professionals | Management of mental health emergencies including differentiating between substance intoxication and psychosis | Education: To upskill generalists in rural and remote areas to respectfully and effectively manage mental health emergency care | N/R | 2-day training, facilitator not reported |

Australia-wide, regional/ rural, remote |

Since 2003. As of 2007, 745 | Commonwealth Department of Health | 3 |

| Mental Health Intervention Team training [28, 29] | NSW Police Force, Queensland Police Service | Mental illness (non-specific) | Police officers | Training to become accredited specialist Mental Health Intervention Officers. Provides a practical skillset to assist them with managing persons within the community who are experiencing a mental health crisis event or suicidal ideation |

Education: Training to identify signs and symptoms of mental illness, provide tools for communication strategies, risk assessment, de-escalation and crisis intervention techniques, and gain an understanding of the current Mental Health Act Contact: Lived experience component presented by panel of mental health consumers and a carer |

N/R | 4-day training (intensive), 1-day training, facilitator not reported | NSW, ACT, WA, QLD | In NSW since 2007 [4-dayprogram]. As of 2015, 2,600 officers trained. Since 2014 [1-dayprogram]. As of Dec 2015, 16,141 officers trained. In QLD since 2006 | State government | 4 |

| Mental Health Intervention Team training (brief) [30] | Oak Flats VKG Call Centre | Mental illness (non-specific) | Emergency service communication officers | A brief version of the MHIT training which teaches how to respond effectively during mental health emergencies with the aim of diversion from jail to mental health treatment | Education: Training to increase the likelihood of call takers identifying mental health calls in order to prepare the responding officers before arriving at the scene | N/R | 1.5–2 h, facilitator not reported |

NSW, metro, regional/ rural |

Since 2011, N/R | N/R | 4 |

1 = No evaluation evidence, 2 = Post survey feedback or qualitative interviews, 3 = One or more uncontrolled trials or repeated cross-sectional surveys, 4 = One or more controlled trials, 5 = One or more randomised controlled trials

LE Lived Experience, N/R Not Reported

Table 4.

Programs targeted to the general population

| Program name | Organisation | Type of mental illness | Target audience | Program description | Anti-stigma component | Lived experience involvement | Session length, facilitated by | Where provided | Duration and reach | Funding | Level of evidencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health 101 (Youth/Adult) [39–42] | Mental Illness Education ACT (MIEACT) | Mental illness (non-specific) | Youth program targets high school students (years 7–10). Adult program targets workplaces | Workshop providing an introduction to mental health. Stigma-based learning outcomes include an understanding of what stigma is, being able to identify negative consequences of stigma, and an ability to contribute to the collective impact to reduce stigma in relation to mental illness |

Contact: Two volunteer educators with lived experience share stories of living with a mental illness Education: an understanding of myths and facts about mental health and examples of help-seeking behaviours |

Programs are delivered by people with LE. Programs are co-designed with mental health professionals and people with LE | 1 60-min session, facilitated by person with lived experience | ACT, metro, regional/rural | Since 1993, 8,000 people per year | Commonwealth gov, state gov, and private funding | 4 |

| Mental Health First Aid [43–53] | Mental Health First Aid Australia | Mental illness (non-specific), Bipolar disorder, Psychosis, Schizophrenia, Depression, Anxiety, Substance Misuse, Non Suicidal Self Injury | General population | A program which teaches members of the public how to provide mental health first aid to others and enhances mental health literacy. A variety of courses exist: Standard MHFA (for adults), Youth MHFA (for adults assisting young people), Older Person MHFA, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander MHFA |

Contact: Two videos involve people with lived experience of mental illness talking about their experiences (one psychosis, one anxiety). Majority of instructors share their own experiences in their teaching Education: Provides accurate information about mental illness to bust myths (e.g. that people with psychotic illnesses are dangerous and unpredictable) Hallucination simulation: Optional activity where two volunteers have a discussion whilst the instructor reads from a scripted ‘voice’ |

Founder has lived experience of mental illness. Curriculum based on consensus studies involving people with lived experience (consumers and carers). Courses are delivered by instructors, most of whom have lived experience as consumers or carers | Standard MHFA is 12 h, Youth MHFA is 14 h. Training is facilitated by an instructor who is accredited by MHFA Australia. Instructors | Australia-wide, metro, regional/rural, remote | Since 2000, 800,000 people | Varies according to Instructor. MHFA Australia receives earned income, intermittent funding from government and philanthropic sources | 5 |

| Peer Ambassador Program | SANE Australia | Mental illness (non-specific), Bipolar disorder, Personality disorders, Psychosis, Schizophrenia, Eating Disorders, Suicide, other low prevalence disorders including complex trauma | General population | SANE Peer Ambassadors are a group of people who work with SANE Australia to raise awareness, reduce stigma and provide hope to Australians affected by complex mental illness. They also help develop, deliver and evaluate SANE’s programs and services. All Peer Ambassadors receive training and support, guiding them through the process of sharing their story in ways that align with their reason for becoming an ambassador |

Contact: Presentations in workplaces and community settings to share their personal experience of living with, or supporting someone with a complex mental illness. Online stories via SANE website Protest/Advocacy: Participants are regularly invited to contribute to advocacy and research projects, review resources and provide their insights through co-design or research projects |

People with LE are paid staff on the program. Program was relaunched in 2018 following extensive consultation with people with LE | 1 45-min session, facilitated by person with LE | Australia-wide, metro, regional/rural, remote | Since 1986 in various forms, 1,000 + (currently 110 Peer Ambassadors) | Corporate partnerships | 1 |

|

Batyr (@school, @uni, @work) |

Batyr | Mental illness (non-specific) | High schools, universities, workplaces | Programs delivered to schools (batyr@school), universities (batyr@uni), and workplaces (batyr@work) |

Contact: Two people with lived experience share their stories, focusing on help-seeking journey [10 mineach]. Video stories are in development and only used in rural communities Education: Signs of mental illness, how to support a peer, seek help, role of language in perpetrating stigmatising attitudes Protest/Advocacy: An addition to the School program, school chapters empower 20 passionate students to lead mental health events on their own school campus throughout the year |

Lived Experience speakers form part of the governance of batyr, and are instrumental in any decision made within the organisation | 1 session 60–90 min, facilitated by person with lived experience and other trained person | ACT,NSW,QLD,SA,VIC, metro, regional/rural, remote | 5–10 years, 229,934 people | Earned income | 5 |

| SPEAK UP! Stay ChaTY [56, 57] | SPEAK UP! Stay ChaTY | Mental illness (non-specific) | High schools, sports/arts organisations, workplaces | Education and awareness programs. Stay ChatTY Schools Program to grades 9–12, Stay ChatTY Sports Program to sporting clubs, Community Presentation to workplaces and community groups |

Contact: Founder Mitch McPherson shares his personal story of losing his brother to suicide through his lived experience story. Lived experience videos of community members sharing their stories of mental ill-health and suicide are used in the Sports Program, the Schools Program and online Education: Programs teach information on mental health vs mental illness, stigma, signs and symptoms of mental illness, resilience, where to access support, helping a friend/team mate/ Other: Delivers online anti-stigma and awareness campaigns via social media, engages with community partners for wellbeing and awareness events, attends community expos and events to promote anti-stigma messages |

Founder with LE supports program development. A Youth Reference Group includes a number of young people with lived experience informs the development of youth-focused program content | 1 45–90 min session. Facilitated by person with lived experience, nurse, exercise physiologist, lawyer, researcher | Australia-wide, metro, regional/rural, remote | Since 2013, ~ 25,000 | State gov, donations, community grants | 3 |

| LIVINWell [58] | LIVIN | Mental illness (non-specific) | Organisations (e.g. workplaces, universities, schools, sports/arts organisations) | Introductory mental health awareness program to educate people on a range of issues related to mental health, with an emphasis on breaking the stigma of mental health, enhancing self-efficacy and encouraging help-seeking behaviour |

Contact: In-person stories of facilitators’ lived experience with mental illness. Video stories of co-founders and how/why LIVIN originated and what their mission is Education: Accurate alarming statistics on mental illness and suicide in Australia |

Programs are co-delivered by people with LE | 1 45-min session, facilitated by mental health professionals and person with lived experience | Australia-wide, metro, regional/rural, remote | 5–10 years, N/R | N/R | 1 |

| Mental Health Awareness | Mental Health Partners | Mental illness (non-specific) | Organisations (e.g. workplaces, universities, sports/arts organisations) | Short courses delivered to private organisations to reduce stigma, give information, offer resources and improve mental health |

Contact: Courses include at least one person with LE who shares their story to inform participants. Most courses include video of people with LE explaining their journeys Education: Myths and facts sessions to improve knowledge |

Programs are designed and co-delivered by people with LE | 1 3-h session, facilitated by social worker, person with lived experience | Australia-wide, metro, regional/rural, remote | 2–5 years old, 1,200 participants | Earned income from private organisations | 2 |

| Staff Wellbeing Workshop [59, 60] | Chess Connect | Mental illness (non-specific) | Workplaces | A workshop that helps employers collaborate with their staff to educate and promote a positive mental wellness workplace culture | Education: Program covers understanding stress, active stress management, reducing stigma, understanding the link between life events, the brain and behaviour, building resilience practices, understanding the impact of workplace habits, and recognising when a person is unwell or struggling | N/R | 1 2-h session, facilitated by ‘Workplace Wellness specialist’ | NSW, regional/rural | N/R, Over 750 people | N/R | 1 |

| Exhibition Program [61, 62] | The Dax Centre | Mental illness (non-specific) | General population | Exhibition Program of art by people with lived experience open to the general public | Education: The exhibition may include bios written by the artists which allow the artist to share aspects of their lived experience that break down myths and provide accurate information about mental illness for visitors | All artists that exhibit have a lived experience and are involved in the process of exhibition development | People visit for between 10 and 20 min. Guided tours last between 30 and 60 min. Facilitated by staff at the Dax Centre | VIC, metro | More than 10 years, ~ 24,000 | Commonwealth gov, philanthropic, earned income | 2 |

| Education Program (Mindfields) [61, 63] | The Dax Centre | Mental illness (non-specific) | Universities, schools | A range of education programs specifically tailored to secondary and tertiary students who are studying mental health or arts-related subjects, encompassing presentations from advocates with LE and tour of current exhibitions |

Contact: Advocates present to the students sharing their lived experience of mental health issues, including a discussion of symptoms, their journey relating to diagnosis, treatment and other recovery factors. Some programs include video stories. Exhibition tours also include information on the artists’ personal stories Education: Myth-busting is woven into the guided tour of exhibitions. Information is given about the history of psychiatric care in Victoria and how stigma has impacted community understanding over time |

Programs delivered by people with LE. Advocates provide feedback on the program and how it can be designed to be more effective | 1 2-h session, facilitated by people with LE, neuroscientists | VIC, metro | More than 10 years, 22,000 people | Commonwealth gov, philanthropic, earned income | 1 |

| Mental health awareness forums | Australian Rotary Health | Mental illness (non-specific), Bipolar disorder, Personality disorders, Psychosis, Schizophrenia | General population | Community forums, organised by Australian Rotary Health and Rotary Clubs, to discuss all aspects of mental health. Speakers usually a mental health professional, a consumer and a carer. Members of the general public are invited to attend |

Contact: Members of the community who have a mental illness are invited to attend and speak Protest/Advocacy: Holding a public forum provides advocacy for mental health awareness and acceptance. No specific activity is undertaken except openness and general discussion on mental health |

People with LE are invited to speak when the program is arranged | 1 2-h session, facilitated by various people, e.g. health professional, Rotarian, MP | Australia-wide, metro, regional/rural, remote | Since 2000, ~ 5000 people | Commonwealth gov (now ceased), some private | 2 |

1 = No evaluation evidence, 2 = Post survey feedback or qualitative interviews, 3 = One or more uncontrolled trials or repeated cross-sectional surveys, 4 = One or more controlled trials, 5 = One or more randomised controlled trials

LE Lived Experience, N/R Not Reported

About half (55%) of the face-to-face programs focused on stigma towards people with a non-specific mental illness, six (21%) targeted a range of disorders including psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or personality disorders, three (10%) specifically focused on psychosis or schizophrenia, two (7%) on ‘severe’ mental illness, and two (7%) specifically on Borderline Personality Disorder.

Three-quarters (76%) of organisations providing anti-stigma programs were classified as not-for-profit or community sector, and the remainder were government (10%), university/tertiary education (10%), or private/for-profit (3%). A majority of organisations (66%) provided a range of services, including some anti-stigma programs, rather than only running anti-stigma programs (34%), and a majority reported running multiple anti-stigma programs (62%). A minority of programs were run in all Australian states and territories (24%), with the largest number run in NSW (31%), followed by Victoria (28%), the ACT (17%), Queensland (14%), South Australia (10%), Tasmania (10%), Northern Territory (10%) and Western Australia (3%)). Programs were also delivered across metropolitan (72%), regional and/or rural areas (62%) and remote communities (31%) with half delivered across multiple geographic areas.

Programs were delivered in a variety of settings, most commonly community settings (e.g. sports or arts organisations, 45%), followed by community health centres (41%). Also common were workplaces (38%), university or tertiary education settings (34%), primary healthcare (17%), and high school (14%). Only 2 were run in primary schools (7%). Programs tended to target adults (59%) or ‘all ages’ (14%). Adolescents were the target age group in four programs (14%) and young adults in two (7%). In addition, one program targeted children 8–18 years old (3%).

Most programs involved people with lived experience in their design (59%) or delivery (76%). Programs often included multiple types of components, but the most common was an education component (66%) followed by face to face contact (62%) or online/video contact (24%). Protest or advocacy was reported in 24% of programs. Only one program included an (optional) hallucination simulation component (3%).

Seven programs did not report a funding mechanism. Of the remainder, there was a variety of funding sources. Funding was sourced most frequently from the Commonwealth government (25% of reported) or from earned income (22%), followed by state government (19%), donations or volunteers (11%), philanthropic (8%), corporate sponsorship (6%), and other means (8%).

Most of the programs were well-established, with half running for more than 10 years (48%), 28% running for 5–10 years, one was 2–5 years old (3%), and one was 6–12 months old (3%). This information was not reported or available for nearly a fifth of programs, however. Information about program reach was not available for seven programs. Of the remainder, ten (45%) had reached up to 1000 people, five (23%) 1000–10,000, four (18%) reached 10,000–100,000, and three programs (14%) had reached over 100,000 people.

The level of evidence for most programs was low. Seven programs (24%) reported no evaluation evidence and a further eight (28%) were evaluated with post program surveys or qualitative interviews only. These surveys tended to focus on satisfaction outcomes rather than impact on stigma. Only two programs (7%) were evaluated with one or more randomised controlled trials, the highest level of evidence. Six programs (21%) had one or more controlled trials, four (14%) were evaluated with one or more uncontrolled trials or repeated cross-sectional surveys, and for two programs the type of evaluation was unclear. Information about program evaluations is available in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation data from face-to-face programs

| Program name | Experimental design | Study sample | Sample size | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batyr [55] | RCT | N/R | N/R | N/R |

In 2017, Macquarie University conducted a study into the effectiveness of the batyr@school program, looking at stigma reduction and help-seeking. The biggest two findings were 1. The program was successful in reducing stigma that young people had towards others experiencing mental health issues 2. The program lead to an increase in attitudes and intentions towards seeking help from professional sources for mental health issues and suicidal thoughts The findings were maintained for at least 3 months after the program |

| BPD Community Information Nights | Post feedback | N/R | N/R | N/R |

Usefulness of the event and information: 99% find them useful Personal confidence and understanding: 83% said its better Feeling more supported: 80% said yes Help personal ability to build relationships: 92% yes Do you expect to use knowledge gained: 97% said yes |

| BPD Community Family & Friends Group | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | From program authors: “A ‘formal’ evaluation occurred in 2017 which lead to the evolution of the program of today. Monthly evaluations of the program are conducted” |

| Collaborative Recovery Training Program (CRTP) [25] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post) | Mental health workers from government and NGO organisations in eastern Australia | 75 with data to analyse out of 103 | Staff Attitudes to Recovery Scale (STARS; Crowe et al., 2006) assesses hopeful attitudes regarding consumers’ recovery possibilities. Therapeutic Optimism Scale assesses treatment expectancies | There was an improvement in STARS pre-post (d = 0.87) and therapeutic optimism scores pre-post (d = 0.78). MANOVA p = .02 |

| Compeer (The Friendship Program) [32] | Survey only | Volunteers from the Compeer program | 72 analysed | Social Distance Scale, Affect Scale, Dangerousness Scale, Match Bond (measures friendship strength) | A stronger relationship between the Compeer volunteer and friend was associated with lower levels of stigma: social distance (p = .001), Affect (p = .015), Dangerousness (p = .028). No relationship between time spent in relationship and stigma, suggesting it is quality of contact rather than length of contact that reduces stigma |

| Journey to Recovery [37] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post) | Carers of person with psychosis | 15 | 6 questions on perceived knowledge: understanding of psychosis, understanding of recovery, knowledge of medication, relapse prevention, understanding of links between substance use and psychosis, plus qualitative feedback | Significant improvements in perceived knowledge of psychosis (p = .001) and recovery (p = .008) pre to post. Qualitative feedback was that participants valued support, felt a reduced sense of isolation, felt a sense of collective experience, and appreciated the opportunity to ventilate and feel heard by peers |

| Journey to Recovery [35] | Qualitative interviews | (1) carers who continually attended; (2) carers who attended once only; (3) carers who never attended; (4) case managers and (5) early psychosis clinicians | 10 carers, 8 clinicians | 7 qualitative questions designed to illicit positive and critical information and suggestions for the future direction of the group | Carers reported Reduced isolation, sense of Collective Experience, Opportunity to vent and feel heard, Reduced stigma and shame, Increased knowledge about mental illness, Enhanced skills in supporting the person experiencing mental illness. The group enabled “helping us to communicate as a family again,” “learning how to communicate and describe what mental illness is to our children,” and “passing it on into the community to help others” (reduced stigma and shame) |

| Journey to Recovery (inpatient version) [36] | Qualitative interviews 6 months later | Carers of person with psychosis | 27 | 14-item interview questionnaire on timeliness, correct people invited, sufficient time, useful information (written, oral, DVD, booklet, fact sheets), support offered, family use of information, follow-up in community, and improvement suggestions | The session and materials were perceived as helpful. Findings in the present study suggest that early psychosis carers are open to receiving psychoeducation at first contact with psychiatric services |

| Journey to Recovery [38] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post) | Families of people with early psychosis | 17 | 6 questions on perceived knowledge: understanding of psychosis, understanding of recovery, knowledge of medication, relapse prevention, understanding of links between substance use and psychosis, plus qualitative feedback | Significant improvements in perceived knowledge of psychosis and recovery pre to post (ps < .001). Qualitative feedback was that participants valued peer support and support from session facilitators, felt a reduction in a sense of isolation, felt a sense of collective or similar experiences and there was an appreciation of the opportunity to ventilate feelings and be heard by peers who understood the challenges faced |

| Kookaburra Kids camps and Activity Days | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | From program authors: “Evidence of impact; (changes in MHL and help seeking) currently continuing with published research to follow 2020” |

| Managing Mental Health Emergencies short course [27] | Repeated cross-sectional surveys (pre/post with some follow-up interviews 3-6mth) | Rural and remote healthcare providers (nurses, Aboriginal health workers, other allied health) | N = 456 at pre, N = 163 post workshop, N = 44 interviews | Survey: 7 questions ranking perceived skills. No information about interview guide | Perceived skills improved in differentiating between psychosis and substance intoxication (p < .001), assessing psychotic symptoms (p < .001), communicating effectively with people with mental health problem (p < .001), assessing suicide risk (p < .001). Almost all interview participants felt they had changed their attitude towards mental health clients as a result of the course, as many recognised that had been stereotyping and stigmatising clients. Participants talked about their increased patience when listening to acutely unwell clients |

| Mental Health 101 [42] | Controlled trial (pre/post). Comparison condition was non-participating schools | High school students | 457 | Two vignettes on stigma which were followed by four questions about their attitudes towards the person described in the vignette and four social distance questions. Multiple-choice questions and open-ended questions on knowledge of mental health and mental illness, and the General Intentions to Seek Help Questionnaire |

The intervention group had lower mean stigma scores (p = .000) and greater knowledge on each of the knowledge questions (all p < .001), and increased help-seeking intentions (p = .000) compared to the control group at post-test. Further analysis revealed a significant effect of the intervention on reducing stigma after the effect of knowledge was removed (p < .001) Qualitative responses revealed many students were deeply touched by the personal stories of presenters, that they were a powerful medium, and made the impact of mental illness tangible and encouraged the realisation that people with mental illness were just ‘ordinary people with extraordinary stories’ |

| Mental Health 101 [41] | Qualitative interviews | Volunteer consumer educators | 10 | Semi-structured interview focused on the benefits and costs related to being in an advocacy/educator role and its impact on recovery from the experience of mental illness and treatment | Reports on the benefits and costs of being a lived experience educator in the MIE-ACT program. Benefits identified were the value of peer support where educators felt a unique sense of acceptance and understanding from their peers, gaining a sense of purpose and personal meaning from the personal satisfaction of educating others, and the impact and therapeutic effect broadcasting had in reducing self-stigma and assisting in positive identify development. Costs reported were feeling ‘raw’ or vulnerable during or after presenting and a fear of being stigmatised as a result of presenting |

| Mental Health 101 [42] | Post surveys | High school students (93.3%) | N/R, 90.7% of learners are surveyed after the program | Satisfaction ratings, perceived knowledge |

89.7% of learners rated the program as either extremely of significantly informative 97.2% of learners state that the programs had increased their understanding of mental health |

| Mental Health Awareness | Post course evaluations of all programs | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R |

| Mental Health First Aid [43] | RCT. Comparison condition was waitlist | Nursing students | 181 (int = 92, control = 89) | Social Distance Scale, Personal Stigma Scale, Perceived Stigma Scale (all for depression vignette) | Outcomes are not relevant as not for schizophrenia/psychosis/bipolar disorder/personality disorder |

| Mental Health First Aid [44] | RCT. Comparison condition was waitlist | Adult members of community | 178 (int = 90, con = 88) | Social Distance Scale, Personal Stigma Scale (depression and schizophrenia) | For schizophrenia, improvements pre-post in personal stigma (p < .001) and social distance (p < .001). Sig improvements at 6-mth FU: personal stigma (p < .001) and social distance (p < .01) |

| Mental Health First Aid [45] | RCT. Comparison condition was waitlist | High school teachers | 423 (int = 283, con = 140) | Personal Stigma Scale for depression only | Outcomes are not relevant as not for schizophrenia/psychosis/bipolar disorder/personality disorder |

| Mental Health First Aid [46] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post/6mth FU) | Adult members of community | 246 | Personal Stigma Scale and Perceived Stigma Scale (for depression and schizophrenia) | Improvements in beliefs about dangerousness (p = .005), unpredictability (p < .001), and willingness to disclose (p = .005) pre to post for schizophrenia. Changes in stigmatising attitudes about schizophrenia from pre-test to follow-up were only significant for disagreement about dangerousness (from 33.1% to 48.5%, p = 0.008). No significant change in perceived stigma |

| Mental Health First Aid [47] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post) | Members of the Chinese community in Melbourne | 108 (84 analysed) | Social Distance Scale (towards depression and schizophrenia vignettes) | Social distance for schizophrenia sig improved pre-post (p = .005) |

| Mental Health First Aid [48] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post) | Members of the Vietnamese community in Melbourne | 114 | Personal Stigma Scale and Perceived Stigma Scale (for depression and schizophrenia) | Significant improvement in some personal stigma items for early schizophrenia (4 of 9) and chronic schizophrenia (3 of 9) |

| Mental Health First Aid [49] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post/6mth FU) | Workers and volunteers of organisations working in multicultural communities | 458 | Social Distance Scale, Personal Stigma Scale, Perceived Stigma Scale (towards depression and schizophrenia vignettes) | Pre-post sig improvements in social distance (p < .001), personal stigma (p < .001) and perceived stigma (p < .001) for schizophrenia. Stigma data not collected at follow-up |

| Mental Health First Aid [50] | RCT. Comparison condition was Red Cross First Aid training | Australian parents of teenagers | 384 (int = 201, con = 183) | Social Distance Scale, Personal Stigma Scale (Weak not sick, Dangerous/unpredictable) towards psychosis vignette | No significant changes in stigma outcomes in parents at 1-year and 2-year follow-up |

| Mental Health First Aid [53] | Controlled trial | Pharmacy students | 272 (int = 60, con = 212) | Social Distance Scale for schizophrenia | Reduced social distance over time compared to control, p < .001 |

| Mental Health First Aid [51] | RCT | Public servants | 608 (int elearning = 199, int blended = 199, con = 210) | Social Distance Scale and Personal Stigma Scale (both for depression and PTSD) | Outcomes are not relevant as not for schizophrenia/psychosis/bipolar disorder/personality disorder |

| Mental Health First Aid [52] | Controlled trial (pre/post/3mthFU) | Chinese international students studying in Melbourne | 202 (int = 102, con = 100) | Personal Attributes Scale, Social Distance Scale (both for depression and schizophrenia) | Significant improvements over time for social distance towards schizophrenia (p = .021). No sig change in perceived dangerousness or perceived dependency |

| Mental Health First Aid | Qualitative focus groups | Mental health first aid instructors, and members of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community | N/R | N/R | N/R |

| Mental Health Intervention Team (MHIT) training [28] | Controlled trial (pre/post/18 month FU). Comparison condition was officers who were not trained | NSW police officers, NSW health staff | 260 (trained = 186, not trained = 74). Presurvey = 112, post = 32, FU = 42) | Levels of confidence, self-reported behaviour change, | The MHIT training led to an increase in confidence in dealing with jobs involving individuals with a mental health problem, or a drug induced psychosis at post and follow-up (ps < .001). Qualitative data supports the notion that the MHIT training led to an increase use of de-escalation techniques, with officers reporting that an increased understanding of mental health meant they were better able to deal with the situation. Qualitative data from NSW Health staff working specifically in mental health were uniform in their perception of an improved understanding about mental health amongst the police officers they engaged with when a scheduled consumer was delivered to their care, and noted the flow-on effect that officers ‘ increased understanding of mental health had on their engagement with consumers |

| Mental Health Intervention Team (MHIT) training (brief version) [30] | Controlled trial (post only). Comparison condition was those who have not completed the training | Emergency call operators (communications officers) | 91 (trained = 18, not trained = 73) | Community Attitudes Towards Mental Illness (CAMI); Social Distance Scale | Findings showed no difference in stigma between those who had undergone CIT training and those who had not |

| My Recovery | Qualitative interviews | Lived experience adult members of the community |

30 (Presurvey = 14, post = 16) |

N/R | N/R |

| Recovery Camp [17] | Controlled trial (pre/post). Comparison condition was traditional nursing placements (inpatient and community mental health) | 3rd year nursing students | 50 (Recovery Camp = 23, comparison = 27) | Preplacement Survey, includes items on Negative stereotypes and Anxiety surrounding mental illness | Sig greater reduction in anxiety (p = .001) and negative stereotyping (.015) in intervention group compared to control. In particular, decreased endorsement of statements that describe mental illness sufferers as unpredictable, incapable and dangerous in the Recovery Camp group |

| Recovery Camp [15] | Controlled trial (pre/post). Comparison condition was traditional nursing placements (inpatient and community mental health) | 3rd year nursing students | 79 (Recovery Camp = 40, comparison = 39) | Social Distance Scale | Sig reductions in social distance in the Recovery Camp group pre to post, and pre to follow-up. No sig reduction in social distance in comparison group |

| Recovery Camp [16] | Qualitative analysis of written reflections | 3rd year nursing students | 20 | 4 critical reflections during their time at Recovery Camp | Students reported the placement was a unique, positive and educational mental health nursing placement. It allowed for the application of knowledge, consolidation of skills, experience of recovery-orientated care, development of therapeutic relationships and learning from people with a lived experience of mental illness about mental illness and related treatments. Recovery Camp was transformative in terms of learning the strengths of people with a lived experience of mental illness, acknowledging previously held fears and anxieties, and establishing future plans for practice |

| Recovery Camp [14] | Qualitative analysis of written reflections | 3rd year nursing students | 56 (28 students, 27 LE) | Content analysis of student reflective quotes | Reflective quotes of students’ experiences showed their understanding and empathy towards people with a mental illness increased, they developed practical skills, appreciated and learnt how to establish and maintain therapeutic relationships, and discovered the importance of lived experience |

| Recovery for mental health nursing practice [18] | Qualitative interviews | Nursing students | 12 | Asked to describe their views and experiences being taught by a person with LE, positives, negatives, and how their nursing practice would be influenced | Students were positive and reported an enhanced self-awareness and greater understanding of the person behind the diagnostic label and their experience. It encouraged them to question their attitudes and prejudices |

| Recovery for mental health nursing practice [19] | Controlled trial (pre/post). Comparison condition was traditional mental health nursing subject taught by nurse academic | Nursing students | 171 (intervention = 110, comparison = 61) | Mental Health Consumer Participation Questionnaire | Both courses improved some aspects of attitudes towards consumer participation in mental health care |

| Recovery for mental health nursing practice [21] | Controlled trial (pre/post). Comparison condition was traditional mental health nursing subject taught by nurse academic | Nursing students | 201 (intervention = 131, comparison = 70) | Scale measuring Anxiety surrounding mental illness and Negative stereotypes | The lived experience-led course showed sig decrease in negative stereotypes (p < .001). Reduction in anxiety was not sig (p = .04—p = .01 set as significance level). Reductions in comparison group were not significant (p = .02 for anxiety and p = .06 for stereotypes) |

| Recovery for mental health nursing practice [20] | Qualitative interviews | Lived experience educators | 12 | Not clear | Reports on the experience of being a lived experience educator in nursing programs. Themes identified were facing fear, demystifying mental illness and issues of power |

| Remind Training and Education [23] | Uncontrolled trial (pre/post/12 mth FU) | Pharmacy students | 178 | Questionnaire with 8 items on stigma towards schizophrenia, reported as individual items. Also focus groups with 11 participants | Significant decreases in stigma at 6-week post and follow-up for 5 out of 8 items relating to schizophrenia (p < .05) (unpredictable; have different feelings; are difficult to talk to; should pull themselves together; are not a danger to others; have themselves to blame). Focus groups showed that the intervention made mental illness more real to them and increased insight, enabled them to see consumers are able to lead a normal life despite their illness, removed some pre-conceived ideas they had about consumers, realised that pharmacists need to be non-judgemental in their interactions with consumers |

| Remind Training and Education [24] | Separate focus groups with students and consumers | Pharmacy students and consumer educators | 23 (11 students, 12 consumer educators) | Impact of the training on students and goals, challenges and benefits of mental health consumer educators providing education to health professional students | All consumers nominated reducing stigma as a primary reason for becoming an educator. The contact the students had with the MHCE provided them with a greater insight into what it is like to suffer from psychotic symptoms and the challenges people face in managing their mental illness. Students reported a change in how they interacted with patients (pharmacy practice) and that their confidence had improved. Consumer educators felt empowered by their participation, reported improved confidence and public speaking skills, and enjoyed the social contact with other consumers. Some reported that fear of social situations was a challenge to fulfil their role |

| Remind Training and Education [22] | Controlled trial (pre/post). Comparison condition was film-based contact | Pharmacy students | 244 (direct contact = 122, indirect contact = 122) were analysed | Social Distance Scale for mental illness [7items]; Attribution Questionnaire [6items]; 8 items on specific stigmatising beliefs towards schizophrenia | Both interventions showed similar reductions in Social Distance scores. The training had greater effect for 5 of 6 Attribution Questionnaire items and 5 of 8 stigma items. Both interventions showed reductions in stigma though |

| Richmond Fellowship Residential Accommodation | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | From program authors: “Ongoing evaluation including DREEM, feedback through the consumer advisory council, and ongoing feedback provided by consumers, families and friends” |

| Rotary mental health awareness forums [64] | Post program feedback forms | Attendees at the forums | 6548 | N/R | Perceptions of good understanding of mental illness increased from 63 to 76% following the forums 64% of attendees had a good to very good awareness of what can be done to reduce the stigma of mental illness following the forums |

| SPEAK UP! Stay ChatTY [56, 57] | Post-session feedback is collected from participants from the Schools Program, Sports Program, Community Presentation and Mitch’s lived experience story. Pre-post data (not linked) is also available for Schools Program | Athletes from sporting clubs in Tasmania (Sports program). Students, teachers, parents from participating schools (Schools Program) | 1239 (Sports program). Approx 1750 students (Schools Program) | Perceived knowledge and attitudes |

Sports Program: Before the session, 818 (66%) athletes reported they knew ‘a bit’ about mental health, whereas after the session, 896 (72%) athletes stated they now know ‘a lot’. Likewise, before the session 673 (54%) athletes reported they knew ‘a bit’ about stigmatising signs of mental illness, however, after the session 869 (70%) athletes knew ‘a lot’ about stigmatising signs of mental illness Schools Program: Following the session, a majority (91.5%) felt more comfortable talking about mental health. There were also increases in perceived knowledge about mental health pre to post (A bit or a lot 81.6% to 97.0%) and perceived recognition of the signs of mental illness (A bit or a lot 63.0% to 96.6%) |

| The Dax Centre—Exhibition Program [61] | Post-feedback only | Exhibition visitors (86.4% were 16—17 year-old school students) | 10,000 | Response card with three statements with Likert scale response (Agree to Disagree) and brief written comments on any aspect of the person’s visit | Over 90% of respondents agreed that the exhibition helped them [1] gain a better understanding of mental illness, [2] gain a more sympathetic understanding of the suffering of people with mental illness; and [3] appreciate the ability and creativity of people with mental illness. These results were supported by the written feedback |

| The Station [31] | Qualitative interviews | Staff and members of a consumer-driven community mental health service | 25 | Interviews focused on The Station’s role in assisting recovery from mental illness, the limitations and strengths of the program, and relationships with the mental health system | Consumers reported feeling accepted and nurtured which increased feelings of empowerment and led to a greater belief in oneself from participating in the Station’s activities. Carers, consumers and volunteers all reported similarly of the positive impact of The Station on their lives. People who volunteer at The Station gain a sense of community and family, ‘time out’ and an opportunity to learn new skills and meet new people |

N/R Not Reported

Programs targeted the following audiences:

Health professionals, health professional students, emergency workers

Our search identified seven programs that target health professionals, health professional students, or emergency workers. These varied in their approach but often included a focus on the potential for recovery, to counterbalance health professionals’ frequent contact with people when they are most unwell. Two programs target nursing students with contact interventions. One of these, Recovery Camp, is a nursing placement designed to facilitate contact between nursing students and people with lived experience outside an acute setting, where recovery is a focus. The program has run since 2013 and is funded by universities who pay for the placement by students. Two controlled trials found reduced anxiety about mental illness, negative stereotyping, and desire for social distance after the placement compared with traditional nursing placements. A second program, Recovery for Mental Health Nursing Practice, is taught by an academic with lived experience and also focuses on recovery concepts. Two controlled trials found improvements in some attitudes compared to a traditional mental health nursing subject. Pharmacy students are targeted by the Remind Training and Education program, which involves trained mental health consumers participating in pharmacy tutorials as educators. This program has run since 2010 and has reached 2,500 students at the University of Sydney. Evaluations in a controlled trial and an uncontrolled trial found reductions in stigma after the program and up to 12 months later. Of note, we identified one other program targeted to health students in a research study, but it is no longer running. This was a contact intervention for final year medical students to reduce stigma against people with schizophrenia as part of 6 week psychiatry rotation (see Additional file 1: Table S3).

Two programs target health professionals with education interventions. The Collaborative Recovery Training Program trains professionals in recovery concepts and is offered by the University of Wollongong. An uncontrolled trial found improved attitudes to consumers’ recovery possibilities after the training. The Managing Mental Health Emergencies short course trains rural and remote generalists how to respectfully and effectively manage mental health emergency care. An evaluation found better skills identifying psychosis and improved attitudes towards mental health clients. A third program, no longer running, focused on improving employment outcomes for consumers by funding Vocation, Education, Training and Employment Coordinators within mental health services (see Additional file 1: Table S2). An evaluation found an improvement in clinicians’ attitudes towards consumer capability of full-time, open employment.

Finally, Mental Health Intervention Team training is delivered to police officers and emergency service communication officers. The training is offered across an intensive 4-day program or 1-day training course. It teaches how to respond effectively during mental health emergencies with education and contact components. It has operated for more than 10 years in the NSW Police Force and Queensland Police Service. While an evaluation of a brief 2-h version for communications officers found no impact on stigma, a second controlled trial evaluating the full training package showed positive effects. Police officers reported increased confidence and understanding of how to deal with jobs involving individuals with a mental health problem or a drug induced psychosis.

People with mental illness

Eight programs target people with a mental illness (see Table 2). Most of these focus on reducing self-stigma, but some programs additionally aim to reduce public stigma through consumer participation in the community (i.e. contact). For example, The Station and TasRec both offer recreation programs where consumers engage with community members in a variety of activities. The Station aims to increase social connections and skills for living in people with a mental illness. It has operated since 1998 in South Australia and receives funding from a variety of sources. Interviews with participants found it increased feelings of empowerment and led to a greater belief in oneself. Similarly, TasRec provides recreation activities to help build skills, increase confidence, and reduce isolation. It has operated for more than 5 years in Tasmania by the Richmond Fellowship Tasmania and receives Commonwealth government funding. The Richmond Fellowship Tasmania also runs another program—Residential Accommodation, for people with mental illness. The service provides support to tackle stigma, access services, build social networks, and reach greater independence.

Two programs provide the opportunity for people with a mental illness to meet and support each other. The Hearing Voices group is a monthly/fortnightly peer support group for people with schizophrenia, who share stories and coping strategies on living with voices. It is offered in Victoria by Uniting Prahran. The BPD Community Information Nights are a forum for sharing information and support for people with Borderline Personality Disorder. They aim to address stigma and discrimination by focusing on hope and optimism about recovery. They are held three times a year in Victoria, supported by volunteers.

My Recovery is a peer-led education program for people living with mental illness offered in Darwin by Northern Territory Mental Health Coalition. The program aims to support recovery and provide a vocational pathway to people with lived experience. It is facilitated by peers and consists of nine weekly sessions that cover education topics such as stigma and discrimination, advocacy, recovery and skills training in communication, personalised recovery planning and goal setting.

A different sort of contact intervention is offered by Compeer (The Friendship Program). Community volunteers and people with a mental illness are matched and meet regularly to develop friendships. The ACT branch of this international program has operated since 2009 with 253 participants. An evaluation found lower levels of stigma in volunteers with stronger relationships with their matches and that stigma was not related to the length of the relationship/contact.

Finally, Being Herd by batyr is a workshop for young people with mental illness who are trained how to share their stories to reduce stigma. This 2-day workshop has trained more than 700 people but has not been evaluated for its impact on stigma.

Families of people with mental illness

Three programs target families of people with mental illness (see Table 3). These include psychoeducation elements to increase understanding of mental illness and how to cope, and as such, may reduce self-stigma and stigma towards their family member, even though this may not be an explicit aim. The BPD Community Family and Friends Group provides support and psychoeducation. The group meets monthly and has operated in Victoria since 2015 on a volunteer basis. The Journey to Recovery is offered by St Vincent’s Mental Health Service in Victoria and has run since 2009. It is a group psychoeducation program for families and friends of people experiencing early psychosis to assist coping and reduce isolation. An outpatient version runs for 5 × 2-h sessions and an inpatient version is a single session. Two uncontrolled trials found improved knowledge of psychosis and recovery and reduced feelings of isolation in participants. A third program, Kookaburra Kids Camps and Activity Days, targets children of people with a mental illness. The program offers therapeutic recreation camps and activities in most states of Australia. Operating for more than 10 years, it has reached more than 3,000 people. Funding is from government, donations and corporate sponsorships.

Members of the general population

The most frequent target of anti-stigma programs was the general population, as we identified 11 programs of this type (see Table 4). Eight of these were training programs delivered in organisations such as schools, universities or workplaces. All programs focus on non-specific mental illness or mental illness including schizophrenia, psychosis, personality disorder, or bipolar disorder, rather than these disorders specifically. These programs are typically quite short, such as around 60 min in length. The exception is Mental Health First Aid training, which is at least 12 h in length. Six programs include both contact and education elements, one includes only contact and one includes only education.