Abstract

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a progressive cystic lung disease which mostly affects premenopausal women and could be exacerbated by pregnancy. Therefore, it is thought that oestrogen plays an important role in LAM pathogenesis. Here, a case of LAM is described in which the first presentation of symptoms occurred during the third trimester of pregnancy. Symptoms included acute onset dyspnoea and chest pain at gestational age of 39 weeks and 2 days. A CT was performed which showed multiple thin-walled cysts and a small pneumothorax. Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-D (VEGF-D) was 1200 pg/mL. The typical cystic lung changes on chest CT in combination with elevated VEGF-D is diagnostic for LAM. Given the risk of respiratory complications, the decision was made to deliver the baby at a gestational age of 39 weeks and 6 days by a planned caesarean section. Both mother and child were discharged home in good condition.

Keywords: obstetrics, gynaecology and fertility, respiratory system, pregnancy, pneumothorax

Background

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a progressive cystic lung disease which mostly affects women of childbearing age. It is a rare multisystem disorder that can affect kidneys and other organs besides the lungs such as lymphatics. It is characterised by the proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the lungs with associated cyst formation.1 2

As mentioned above, patients with LAM are primarily premenopausal women (approximately two-third) but it could be present in postmenopausal women and sometimes in men as well. The average age at onset of symptoms in women is around 35 years.3 The disease can either be hereditary or sporadic. Hereditary LAM is associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) which is an autosomal-dominant genetic disorder. It is a syndrome marked by cerebral calcifications resulting in seizures and mental retardation. It also causes lesions in various organs.4 The term sporadic LAM is used for patients who do not have TSC. The exact incidence and prevalence is not known but is estimated to be approximately 1 in 400 000 adult women.5

The vast majority of patients with LAM typically present with pulmonary manifestations such as dyspnoea associated with spontaneous pneumothorax.6 It may also cause sudden chest pain, cough and haemoptysis.3 As dyspnoea is a non-specific symptom and LAM is rare women are sometimes labelled with a diagnosis of asthma or allergy.7 This could be problematic since pneumothorax is treated differently.

Although pulmonary manifestations are most common in patients with LAM, renal angiomyolipomas occur in up to 30% of patients with sporadic LAM.6 Renal angiomyolipomas are benign tumours which contain blood vessels, fat and muscle tissue. Since they can contain aneurysms, acute bleeding or haemorrhage might occur. However, most patients do not initially present themselves with these symptoms.

Other non-pulmonary manifestations of LAM include lymphadenopathy, chylothorax and uterine LAM lesions. Although only a few cases of uterine LAM lesions have been described.8

Though the exact underlying pathogenesis of LAM has yet to be determined, there are some evidence-based thoughts. For instance, several studies reported that TSC and LAM are linked to mutations in the TSC gene. There are two TSC genes: TSC1 and TSC2. Both function as tumour suppressor genes. TSC2 mutations were found in angiomyolipomas of patients with sporadic LAM. The same mutation was found in pulmonary LAM cells.9 Sporadic LAM is not inheritable.

Moreover, it is suggested that oestrogen plays an important role in the pathogenesis as pregnancy and use of oestrogen based oral contraceptives can worsen symptoms of already existing LAM.10 The hypothesis that oestrogen plays a role is also supported by other observations: it is known that LAM cells express both oestrogen and progesterone receptors and are thought to drive LAM cell proliferation;11 there is stabilisation of the disease progression in postmenopausal women,12 and lung function decrease is known to slow after menopause.13

Even though there is evidence that oestrogen plays an important role in pathogenesis, hormonal therapy should not be used as treatment. Oophorectomy and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues have been used in patients with LAM without evidence of effectiveness.5 There is also some contradiction about the role of oestrogen. A case control study by Wahedna et al14 did not support the hypothesis that use of oral contraceptives is causally associated with the development of LAM. Considering the small amount of participants included due to the rare prevalence of LAM more research is needed.

Although very little is known and reported about prevalence and incidence of LAM during pregnancy, a number of case reports have described LAM presenting or exacerbating during pregnancy.10 15 One retrospective study reported that up to two-thirds of women with LAM in this study (n=205) had been pregnant at some point in their lifetime.2

Since pregnancy is thought to exacerbate symptoms of LAM women are sometimes recommended to avoid pregnancy. Options for contraception include, for example, a copper or low-dose drug-eluting intrauterine device and sterilisation. Progesterone-based oral contraceptives are also recommended. Oestrogen containing oral contraceptives should be avoided.16

All patients with LAM, including those with few symptoms, should be educated about the greater risk of developing pneumothorax or chylous effusion during pregnancy and the risk of lung disease progression. There may also be a greater risk of bleeding from angiomyolipoma when present.5 Counselling should be on an individual base since it is likely that patients with poor baseline lung function are more likely to suffer badly from a pneumothorax or chylous effusion during pregnancy.5

In a retrospective study, investigators surveyed 328 women with LAM regarding pregnancy outcomes.

Women diagnosed with LAM during pregnancy had significant worse pregnancy outcomes in comparison to women who were diagnosed before or after pregnancy. Premature delivery and miscarriages were seen when LAM was diagnosed during pregnancy in 8 out of 15 patients (53%). However, it was not known whether delivery was initiated by the obstetrician because of concerns about health of the mother or fetus or whether the premature birth was spontaneous.2 For women who decide to become pregnant, pulmonary function tests are advised every 3 months during pregnancy along with monitoring for other complications of LAM.

No large trials have been conducted among pregnant women with LAM since it is a rare disease. Therefore, it is of great importance to get more knowledge about the effect of LAM on pregnancy and the effect of pregnancy on LAM progression for instance via case reports.

This case report describes the initial presentation of sporadic LAM in the third trimester of an uncomplicated pregnancy.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old primigravida presented with the main complaint of acute onset dyspnoea and a worsening stabbing pain on the chest and left shoulder at gestational age of 39 weeks and 2 days. The pain was provoked by coughing. Until this presentation, her pregnancy was uncomplicated.

Her medical history contained only an excisional procedure of the cervix. No medication was used at the time of presentation. She was a non-smoker with no previous history of lung diseases or allergies. Her family history did not include any lung diseases.

Before maternity leave, the patient worked as flight attendant. Hence, her hobby was scuba diving.

Physical examination showed some dyspnoea and chest pain on the left and the anterior side of the left shoulder. Saturation was 97%. The other vital parameters, the initial chest X-ray and the ECG were normal.

Investigations

Chest CT angiogram was performed to exclude presence of pulmonary embolism as D-dimer level was elevated: no pulmonary embolism was seen; however, it demonstrated numerous thin-walled, round cysts bilateral. Furthermore, it showed a small pneumothorax on the left apical side. Both findings were highly suspicious for LAM (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Axial chest CT image showing a small cyst in the left lung aligning a small pneumothorax.

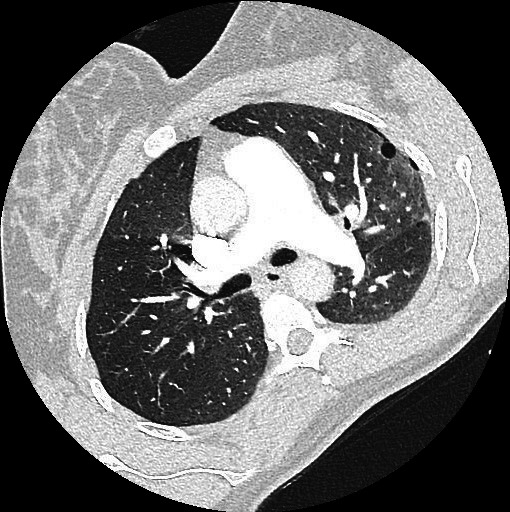

Figure 2.

Axial chest CT image showing numerous small cysts bilateral.

Ultrasound of the kidneys and liver showed no abnormalities, especially no angiomyolipomas.

To confirm the diagnosis serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor-D (VEGF-D) was measured. Serum level was 1200 pg/mL.

Typical cystic lung changes on chest CT in combination with elevated VEGF-D titres is diagnostic for LAM. Although there is no diagnostic laboratory finding for LAM, several studies have already shown that serum levels of VEGF-D are elevated in up to two-thirds of women with LAM and that levels greater than 800 pg/mL can differentiate LAM from other cystic lung diseases.17–19 Even though lung biopsy is the golden standard, confirmation of elevated VEGF-D is less invasive and therefore no lung biopsy was performed.

Differential diagnosis

Hyperventilation syndrome is a condition most commonly characterised by uncomfortable breathing as present in our patient and a general sense of distress. It can be associated with pain. As our patient experienced extreme chest and shoulder pain, the diagnosis hyperventilation syndrome could easily have been made when no additional research was done.

However, the patient presented with progressive dyspnoea too; therefore, pulmonary embolism was excluded since pregnancy is a risk factor for venous thromboembolism. D-dimer level was measured and elevated. This is a non-specific finding since D-dimer levels also increase during normal course of pregnancy. Consequently, confirmatory imaging was needed and despite of the pregnancy a CT scan was performed. The CT scan revealed multiple cysts and a small pneumothorax. It showed no signs of pulmonary embolism.

The differential diagnosis of the findings seen on the CT scan was lymphoid interstitial pneumonia or rare hereditary cystic lung disease (Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome). The increased VEGF-D level made the diagnosis LAM more probable.

Treatment

No therapy was needed for the pneumothorax since it was minimal; standard lifestyle advise was given to prevent early recurrence. According to MacDuff et al20 pneumothorax in pregnancy can be treated by observation if the woman is not dyspnoeic, when there is no fetal distress and the size of the pneumothorax is less than 2 cm.

Based on radiological and laboratory findings, the diagnosis was LAM. No consensus exists in literature in choosing between delivering by caesarean section or vaginally; therefore, an individualised choice should be made. As both vaginal delivery and planned caesarean section are safe options, these options including potential risks were discussed with the patient.

Pneumothorax as a respiratory complication due to the increasing intrathoracic pressure during labour was explained to our patient. Therefore, a safe option would be regional (epidural) anaesthesia with elective assisted delivery (with vacuum extraction) to reduce maternal effort.20 The alternative being a caesarean section was also explained; spinal anaesthesia would be preferred to avoid mechanical ventilation. During admission, the fetus showed no signs of distress. Ultrasound demonstrated no congenital anomalies and normal growth of the fetus.

After counselling, the patient decided to deliver by planned caesarean section. The decision was made to deliver the baby at 39 weeks and 6 days of gestation.

Awaiting the date of the caesarean section, the patient went home since the pain was under control with pain medication. The patient was advised to return to hospital if increasing dyspnoea or pain developed.

As planned, the caesarean section was performed under spinal anaesthesia, delivering a healthy infant weighing 3167 g. After 2 days, the patient and baby were discharged home.

Since the symptoms decreased after delivery, no medication was started. Supportive care and advices including maintaining a healthy weight, lifestyle and a non-smoking state would be sufficient for now. The European Lung Foundation advises to have vaccinations against influenza and pneumococcus in the future. When symptoms start to worsen, treatment with sirolimus should be kept in mind as inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin pathway seems to slow down the disease.21

Regarding her work as a flight attendant, a period of at least 2 months is advised to avoid air travel. Depending on the extent of disease severity, air travel could even be discouraged. A surgical approach with pleurectomy should be considered to reduce the change of pneumothorax recurrence.

The combination of a spontaneous pneumothorax and cystic lung lesions is a strong contraindication for scuba diving lifelong.

Outcome and follow-up

Eleven weeks after diagnosis, spirometry and diffusion testing were performed which were normal. Pulmonary function test was done with delay while recovering from the pneumothorax.

The European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines recommend to evaluate disease progression in non-pregnant women by repeating lung function tests at 3–6 monthly intervals in the first year after diagnosis and thereafter at 3–12 monthly intervals depending on the severity and progression of the disease.5

Clinical features of LAM vary per patient and therefore it is difficult to give patients information about prognosis. It is possible that a pneumothorax will reappear in a subsequent pregnancy. When our patient decides to become pregnant in the future, close cooperation between obstetricians, the thoracic surgeon, and pulmonologists in combination with close observation is required. In case of pneumothorax recurrence, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with pleurectomy should be considered. The patient was not referred to a thoracic surgeon for VATS after postpartum period since VATS only reduces the change of pneumothorax recurrence. The decision to abstain from referral to a thoracic surgeon was made together with the patient.

DISCUSSION

A 36-year-old pregnant woman presented with acute chest pain and dyspnoea. Based on the symptoms, laboratory results, CT scan and diagnostic criteria of the ERS, the diagnosis was ‘probable LAM’.5 The criteria for definite LAM were not met in this case.5

In retrospect, most of the guidelines and recommendations were followed in this specific case.

The ERS recommends to perform spirometry and transfer factor of the lung for carbon monoxide (TL, CO) in the initial evaluation of patients with LAM.5 We did not perform these tests in the first evaluation of the patient as a recent pneumothorax is a contraindication for this kind of testing.

The patient never had prepregnancy lung function tests, so no comparison could be made between before and after diagnosis.

The ERS also suggests that all patients with LAM should have an abdomino-pelvic CT at diagnosis or during work up to exclude abdominal lesions. No abdomino-pelvic CT scan was performed yet as the patients was pregnant at time of diagnosis. However, we did perform an ultrasound of the kidneys. In future workup, the abdomino-pelvic CT scan should be performed.

In the current case, there was no suspicion of the patient having TSC. If doubt exists, the ERS advices a referral to a clinical geneticist.

In line with recommendation of the Official American Thoracic Society/Japanese Respiratory Society guidelines, no lung biopsy was performed. These guidelines state that VEGF-D testing to establish the diagnosis of LAM is the first step for patients whose CT scan shows characteristics of LAM. The sensitivity of serum VEGF-D testing is 73% and the specificity is 99%.13

Management of LAM is based on supportive care, use of medication (sirolimus) and prevention or treatment of complications. It was already shown that treatment with sirolimus (also known as rapamycin) has beneficial effects in patients with moderate to severe LAM. Sirolimus is registered for prophylaxis of organ rejection in patients receiving renal transplants. It is the only Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) approved treatment for LAM. It stabilises lung function and improves quality of life. In patients with LAM, it suppresses the proliferation of LAM cells.22 Therefore, treatment with Sirolimus for patients with abnormal or declining lung function is recommended. Sirolimus was well tolerated and had only minor adverse effects such as mucositis, diarrhoea and nausea.13

If lung disease progression occurs during pregnancy, treatment with sirolimus should also be considered. One case report described a case in which a pregnant women received sirolimus during pregnancy successfully.23 Nonetheless, according to the FDA, no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women regarding development of the fetus have been performed. The patient in this case report was not given sirolimus. Although it is not yet known whether Sirolimus is excreted in human milk, breast-feeding should be discouraged.

Not much is known yet about prognosis. Prognosis is highly variable.

More research is needed to learn about prognosis, prevalence and incidence of LAM. Hence, future research and guidelines should focus on treatment of initial presentation of LAM during pregnancy. Very little is reported about management of symptoms during pregnancy. This article could be helpful in decision making in management of symptoms during pregnancy.

Learning points.

Consider lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) in young, premenopausal women with dyspnoea and chest pain.

Any pregnant woman with normal saturation and shortness of breath should be examined for underlying pathology such as LAM. Imaging should not be avoided because of radiation as recognition of an underlying disease is essential for an uncomplicated pregnancy and birth.

Vascular endothelial growth factor is a validated and less invasive measurement than biopsy for diagnosing LAM.

Footnotes

Contributors: LA wrote the article. BK provided the information about lung diseases as he is a pulmonologist. MATB and MGvP provided information about the obstetric part.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bearz A, Rupolo M, Canzonieri V, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori 2004;90:528–31. 10.1177/030089160409000519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MM, Freyer AM, Johnson SR. Pregnancy experiences among women with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Respir Med 2009;103:766–72. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Factsheets LAM. Available: https://www.europeanlung.org/en/

- 4.Harari S, Torre O, Cassandro R, et al. The changing face of a rare disease: lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J 2015;46:1471–85. 10.1183/13993003.00412-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, et al. European respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J 2010;35:14–26. 10.1183/09031936.00076209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryu JH, Moss J, Beck GJ, et al. The NHLBI lymphangioleiomyomatosis registry: characteristics of 230 patients at enrollment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:105–11. 10.1164/rccm.200409-1298OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pais F, Fayed M, Evans T. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: an explosive presentation of a rare disease. Oxf Med Case Reports 2017;2017:92–4. 10.1093/omcr/omx023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaiswal VR, Baird J, Fleming J, et al. Localized retroperitoneal lymphangioleiomyomatosis mimicking malignancy. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:879–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:6085–90. 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitra S, Ghosal AG, Bhattacharya P. Pregnancy unmasking lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Assoc Physicians India 2004;52:828–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao L, Yue MM, Davis J, et al. In pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis expression of progesterone receptor is frequently higher than that of estrogen receptor. Virchows Arch 2014;464:495–503. 10.1007/s00428-014-1559-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson SR, Tattersfield AE. Decline in lung function in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: relation to menopause and progesterone treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:628–33. 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.9901027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormack FX, Gupta N, Finlay GR, et al. Official American thoracic society/Japanese respiratory Society clinical practice guidelines: lymphangioleiomyomatosis diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:748–61. 10.1164/rccm.201607-1384ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wahedna I, Cooper S, Paterson IC, et al. Relation of pulmonary lymphangio- leiomyomatosis 1994:910–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Khaddour K, Shayuk M, Ludhwani D, et al. Pregnancy unmasking symptoms of undiagnosed lymphangioleiomyomatosis: case report and review of literature. Respir Med Case Rep 2019;26:63–7 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.rmcr.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson SR, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Clin Chest Med 2016;37:389–403. 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seyama K, Kumasaka T, Souma S, et al. Serum of patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Lymphat Res Biol 2006;4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young LR, Vandyke R, Gulleman PM, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor-D prospectively distinguishes lymphangioleiomyomatosis from other diseases. Chest 2010;138:674–81. 10.1378/chest.10-0573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang WYC, Cane JL, Blakey JD, et al. Clinical utility of diagnostic guidelines and putative biomarkers in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Respir Res 2012;13:1. 10.1186/1465-9921-13-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax 2010;65 Suppl 2:ii18–31. 10.1136/thx.2010.136986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strange C, Nakata K, Ph D, et al. New England Journal 2011:1595–606.

- 22.Raymond E, Pisano E, Gatsonis C, et al. New England Journal. SCD-Heft. Heart Fail 2011;364:225–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faehling M, Wienhausen-Wilke V, Fallscheer S, et al. Long-Term stable lung function and second uncomplicated pregnancy on sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffus Lung Dis 2015;32:259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]