Abstract

Proliferating trichilemmal tumours (PTTs) are rare cutaneous adnexal tumours derived from the hair shaft outer root sheath. We are reporting the first case of PTT in a young child. In this case, a 7-year-old girl presented with trichilemmal keratinisation consistent with PTT. The patient was monitored with no signs of recurrence. PTT is a rare tumour occurring primarily in adults and we present this case so that young patients with PTT can be diagnosed and treated appropriately with a painless, mobile, rapidly growing mass on the right upper eyelid. CT imaging showed well-circumscribed, heterogenous mass measuring 1.6 cm with fluid-filled appearance and no tissue invasion. Surgical excision was performed and pathology revealed an unencapsulated, well-demarcated tumour.

Keywords: pathology, head and neck surgery, otolaryngology / ENT, plastic and reconstructive surgery, dermatology

Background

Proliferating trichilemmal tumours (PTTs) are rare cutaneous adnexal tumours derived from the outer root sheath of hair shafts otherwise known as trichilemmal.1 2 PTT predominantly occurs in women and is found most commonly on the scalp during the fourth to eight decades of life. The youngest reported patient diagnosed with PTT was previously reported as 16 years old.3 4 In this report, we discuss the first case of PTT in a 7-year-old girl and the presentation, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this disease.

Case presentation

A 7-year-old Caucasian girl with no significant medical history presented with a mass above her right eyebrow for 4 months. Mother reported rapid growth of the lesion starting 6 weeks prior to outpatient visit.

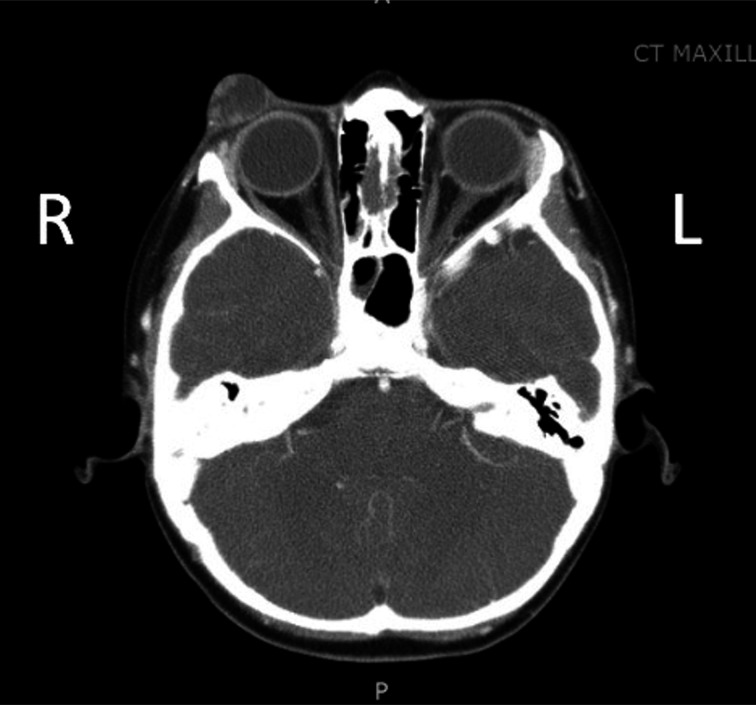

Physical examination revealed a 2 cm exophytic, soft, mobile subcutaneous vascularised mass of the right upper eyelid (figure 1A, B). No sensory or motor deficits were present and there was no cervical lymphadenopathy. Maxillofacial CT imaging demonstrated a right preorbital mass measuring 1.6 cm with predominant fluid density and internal heterogeneous contrast enhancement. A clear fat plane was observed at deep aspect with no tissue invasion of surrounding structures (figure 2). Since the lesion was on the eyelid, we elected to proceed with 0.5 mm of additional tissue circumferentially along the tumour edge in order to achieve both clear margins and a desired cosmetic result (figure 3).

Figure 1.

(A, B) Proliferating trichilemmal tumour.

Figure 2.

CT image of showing right preorbital mass measuring 1.6 cm demonstrating predominant fluid density and internal heterogeneous contrast enhancement with no invasion of surrounding structures.

Figure 3.

Postoperative photograph.

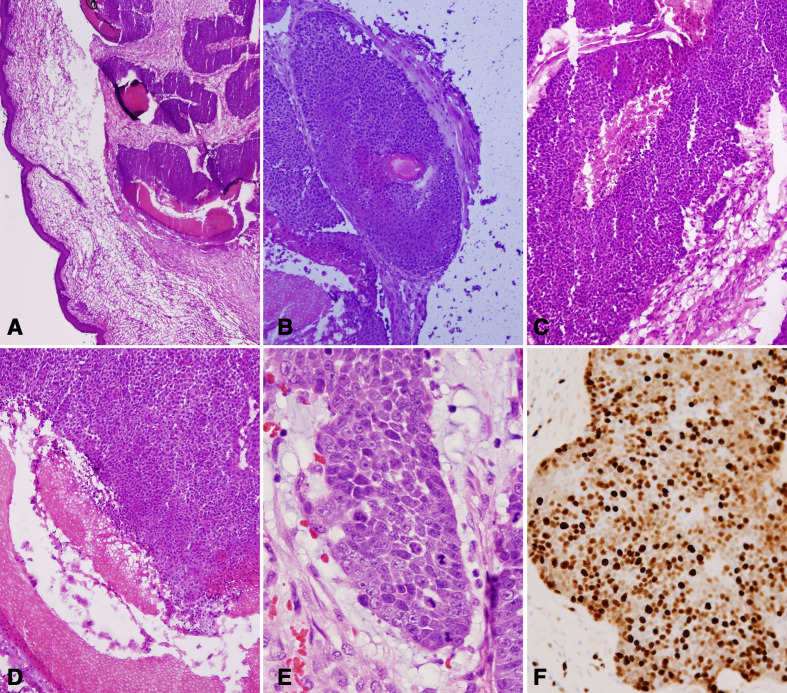

Pathology of the excised mass showed an unencapsulated but well-demarcated tumour with expansile growth of basaloid cells undergoing an abrupt change into keratinised epithelial cells. The tumour had brisk mitosis (5–10 mitoses/high power field) with moderate nuclear pleomorphism but no atypical mitotic figures. There was no infiltrating growth or extension into surrounding tissue (figure 4A, B). There was marked trichilemmal keratinisation, and basaloid cells that enlarged and became squamoid cells toward the centre of the tumour (figure 4A–F), favouring PTT.

Figure 4.

(A, B) Lower power views of the tumour: the tumour is well demarcated and composed of basaloid cell nests that form multiple irregular lobules. Central spaces and rare hair follicles are noted. (C, D) In the centres of the tumour nests, the basaloid tumour cells are undergoing an abrupt change into keratinised epithelial cells and further transform into amorphous keratin materials. (E, F) Brisk mitosis (white arrows) and moderate nuclear pleomorphism are present (E), and Ki-67 immunostain shows its high proliferative index.

After discussion by a multidisciplinary tumour board, a collaborative plan was made for close clinical surveillance. The patient showed no signs of recurrence.

Investigations

Clinically, PTT typically presents as a solitary, firm nodule with intradermal swelling3 5 that can undergo ulceration.3 PTTs usually range from less than 1–10 cm in size.3 Although a majority of cases occur on the scalp, PTT has been reported to occur in other anatomic areas, such as the face, ear, upper extremities, trunk, anogenital area, buttock and thigh.3 6–9 PTT has a clinical resemblance to keratinous or sebaceous cyst.10 The diagnosis of PTT is made histologically, but there can be difficulty in differentiating between trichilemmal cyst (TC), PTT and malignant PTT (MPTT).

Imaging

A homogeneous, isointense signal on T1-weighted MRI is characteristic of most trichilemmal tumours, including TC, PTT and MPTT.11 A homogeneous, hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and non-enhancement by contrast material is characteristic of TC. PTT can manifest as either a cystic or solid mass on CT and MRI.11 Both PTT and MPTT show the same imaging features, such as heterogeneous, mixed signals on T2-weighted images, significant enhancement of the wall and mural nodules by contrast medium, and pathological components of solid lobules and cystic cavities.11 Findings such as large size (>5 cm), rapid enlargement, poorly defined margins and invasion into the tissue planes of surrounding structures suggest MPTT.11 12

Pathology

The hallmark histopathological feature of TC and PTT is the presence of trichilemmal keratinisation, described as an abrupt keratinisation in the absence of a granular layer.2 PTT exhibits broad bands of epithelial cells that contain smaller basaloid cells, which enlarge and become squamoid cells as they progress toward the lumen of the tumour, forming both solid and cystic areas often in continuity with the epidermis.13 14 Features favouring the diagnosis of PTT include the presence of multiple circumscribed nodules with a palisaded border, abundant trichilemmal rather than epidermoid keratinisation; and a lack of surrounding actinic keratosis and solar elastosis.6

Treatment

The most widespread therapeutic approach in managing PTT is surgical excision with histological margin of 1 cm; however, there are no uniformly recommended margins or depth of incision.4 14 Sau et al report simple excision of PTT is curative, but the tumours have the ability to recur and become malignant if not completely excised.3 Failure to examine the entire margin and identify microscopic focal extensions may lead to local recurrence.14 Since the lesion was on the eyelid, we elected to proceed with 0.5 mm of additional tissue circumferentially along the tumour edge in order to achieve both clear margins and a desired cosmetic result. Clinical follow-up has been recommended to monitor for recurrence,15 but there is no specific timeline for surveillance found in the literature. We are following our patient every 6 months for signs of recurrence. She is 7 months removed from excision and showing no signs of recurrence.

Outcome and follow-up

Ye et al performed meta-analysis of 185 cases, reporting rates of local recurrence and regional lymph node metastasis for PTT were 3.7% and 1.2%, respectively.10 The time period between excision and local recurrence has varied from months to 9 years.7 16 Interestingly, the aggressiveness of PTT cannot be predicted based on the clinical picture, and further studies are needed to identify immunohistochemical markers for better subclassification in regards to treatment.14

Discussion

Epidemiology

PTTs were first reported by Wilson-Jones in 1966, and are rare cutaneous adnexal tumours.1 2 A variety of diagnostic terms have been appended during the past 50 years, including proliferating epidermoid cyst, pilar tumour of the scalp, proliferating TC, proliferating epidermoid cyst, giant hair matrix tumour, hydatidiform keratinous cyst, trichochlamydocarcinoma and invasive hair matrix tumour.1 2 6 17–21 A meta-analysis of 185 cases showed that 79.5% of the patients were women, 85.4% of tumours occurred on the scalp, and patient ages ranged from 21 to 88 years, with a mean of 62.4 years.10 The tumours measured up to 25 cm in maximum dimension with a mean of 3.3 cm in size.10 Previously, the youngest reported age of PTT in the literature was 16 years old.4

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of PTT is poorly understood. Many postulate trauma and inflammation of pre-existing TCs induce PTT5 6 15 22 23; however, Baptista et al reported a case of PTT that occurred de novo without a pre-existing TC.24 It has been proposed that the longer isthmus of anagen terminal hair follicles may explain the predilection on the scalp of trichilemmal tumours.24 Saida et al described three stages in the oncologic development of PTT including the adenomatous stage of a TC, the epitheliomatous stage of PTT, and the carcinomatous stage of MPTT.23

PTT and malignancy

PTT can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), contributing to confusion in diagnosis. This occurs when isolated histologic fields with cellular atypia are studied independently from the overall pattern of the lesion.14 The clinical presentation of a slow growing subepidermal cystic tumour is important in differentiating PPT from SCC. Additional microscopic features suggesting PTT include sharp demarcation, tendency to keratinise centrally, areas suggesting origin from a preexisting cyst, and lack of evidence of origin from a premalignant epidermal lesion such as actinic keratosis.15

There has been controversy over whether PPT itself should be considered benign or malignant. Folpe et al describe PTT in its classic form as a well-circumscribed mass without cytologic atypia and is entirely benign.25 Other literature suggests that ‘‘benign’’ PTT is not a true entity because cases of PTT with little cytologic atypia have displayed aggressive behaviour, and any proliferating component should be regarded as a sign of malignancy.14 In a recent comprehensive meta-analysis, Ye et al proposed a pathological stratification of PPT into three groups. Group 1 (benign) encompasses any well circumscribed lesion with pushing margins, mild nuclear atypia, and absence of mitoses, necrosis, or neurovascular invasion. Group 2 (malignant low grade) is similar to group 1 but manifests as irregular, locally invasive silhouettes with involvement of the deep dermis and subcutis. Group 3 (malignant high grade) includes tumours with invasive growth patterns, marked nuclear atypia, pathological mitotic forms, and necrosis, and with or without neurovascular invasion.10 26 27

Alternatively, Mehregan and Lee posit that MPTT exhibits invasion into adjacent structures and severe cellular atypia, both of which are not defining characteristics of classic PTT.16 Satyaprakash et al report that the suggested histological criteria for diagnosis of MPTT should include the presence of abnormal mitoses and high mitotic rate, marked cellular pleomorphism, cytologic and architectural atypia, infiltrating margins, necrosis and aneuploidy.13

Learning points.

Proliferating trichilemmal tumour (PTT) is rare in young children, which commonly results in misdiagnosis.

A diagnosis of PTT should be considered in a patient of any age with a clinical presentation of a rapidly enlarging subepidermal cystic mass, and radiographic imaging should be obtained to determine evidence of tissue invasion to aid in diagnosis and treatment.

Clinical presentation of the tumour in conjunction with the hallmark pathological feature of trichilemmal keratinisation and absence of tissue invasion on imaging suggests PTT.

Surgical excision with clear margins is the standard of care to prevent recurrence.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Xin Gu for interpreting the pathology and Dr Gregory Tobin for interpreting the CT imaging.

Footnotes

Contributors: AB and SK reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. AB obtained patient consent and was responsible for radiological images. YL was responsible for pathological images and interpretation. SK and PB were clinically responsible for the patient’s care, patient images and revised the manuscript. PB completed the final revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Jones EW Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol 1966;94:11–19. 10.1001/archderm.1966.01600250017002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinkus H "Sebaceous cysts" are trichilemmal cysts. Arch Dermatol 1969;99:544–55. 10.1001/archderm.1969.01610230036008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sau P, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Proliferating epithelial cysts. clinicopathological analysis of 96 cases. J Cutan Pathol 1995;22:394–406. 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1995.tb00754.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonseca TC, Bandeira CL, Sousa BA, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumor: case report. J Bras Patol e Med Lab 2016;52:120–3. 10.5935/1676-2444.20160014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leppard BJ, Sanderson KV. The natural history of trichilemmal cysts. Br J Dermatol 1976;94:379–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb06115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownstein MH, Arluk DJ. Pro life RA ting TRiC H ilem M A1 cyst, 1981: 1207–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.López-Ríos F, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Aguilar A, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with focal invasion: report of a case and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol 2000;22:183–7. 10.1097/00000372-200004000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sethi S, Singh UR. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: report of two cases, one benign and the other malignant. J Dermatol 2002;29:214–20. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00252.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KS, Chang JH, Choi N, et al. Radiation-Induced sarcoma: a 15-year experience in a single large tertiary referral center. Cancer Res Treat 2016;48:650–7. 10.4143/crt.2015.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;122:566–74. 10.1309/21DK-LY2R-94H1-92NK [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitajima K, Imanaka K, Hashimoto K, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of proliferating trichilemmal tumor. Neuroradiology 2005;47:406–10. 10.1007/s00234-004-1328-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park BS, Yang SG, Cho KH. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor showing distant metastases. Am J Dermatopathol 1997;19:536–9. 10.1097/00000372-199710000-00109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satyaprakash AK, Sheehan DJ, Sangüeza OP. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:1102–8. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tierney E, Ochoa M-T, Rudkin G, et al. Mohs' micrographic surgery of a proliferating trichilemmal tumor in a young black man. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:359–63. 10.1097/00042728-200503000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evrenos MK, Kerem H, Temiz P, et al. Malignant tumor of outer root sheath epithelium, trichilemmal carcinoma. clinical presentations, treatments and outcomes. Saudi Med J 2018;39:213–6. 10.15537/smj.2018.2.21085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehregan AH, Lee KC. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors--report of three cases. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1987;13:1339–42. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1987.tb03579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elder DE Lever’s histopathology of the skin. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelley WB, Beerman H. Hydatidiform keratinous cyst: clinical recognition of a bengin proliferating epidermoid cyst, 1970: 279–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dabska M Giant hair matrix tumor, 1966: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes EJ Tumors of lower hair sheath. Common histogenesis of certain so-called "sebaceous cysts," acanthomas and "sebaceous carcinomas". Cancer 1968;21:234–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed RJ, Lamar LM. Invasive hair matrix tumors of the scalp. invasive pilomatrixoma. Arch Dermatol 1966;94:310–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendricks DL, Liang MD, Borochovitz D, et al. A case of multiple Pilar tumors and Pilar cysts involving the scalp and back. Plast Reconstr Surg 1991;87:763–7. 10.1097/00006534-199104000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saida T, Oohard K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatology 1983;166:203–8. 10.1159/000249868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poiares Baptista A, Garcia E Silva L, Born MC, Baptista AP, Siliva LGE. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst. J Cutan Pathol 1983;10:178–87. 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1983.tb00324.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folpe AL, Reisenauer AK, Mentzel T, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: clinicopathologic evaluation is a guide to biologic behavior. J Cutan Pathol 2003;30:492–8. 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trabelsi A, Stita W, Gharbi O, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor of the scalp: a case report. Dermatol Online J 2008;14:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shetty PK, Jagirdar S, Balaiah K, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor in young male. Indian J Surg Oncol 2014;5:43–5. 10.1007/s13193-013-0259-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]