Abstract

Background

The adverse prognostic impact of poor pathologic nodal staging has stimulated efforts to heighten awareness of the problem through guidelines, without guidance on processes to overcome it. We compared ‘heightened awareness’ of nodal staging quality versus a lymph node collection kit.

Methods

We categorized curative-intent lung cancer resections from 2009-2020 in a population-based non-randomized stepped wedge implementation study of both interventions, into pre-intervention baseline, heightened awareness and kit sub-cohorts. We used differences in proportion and hazard ratios across the sub-cohorts, to estimate the effect of the interventions on poor quality (non-examination of nodes [pNX] or mediastinal nodes [pNXmed]) and attainment of quality recommendations of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the Commission on Cancer (CoC) and the proposed complete (R0) resection definition of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) across the three cohorts.

Results

Of 3734 resections: 39% were pre-intervention; 40% kit; and 21%, heightened awareness cases. Cohort proportions with: pNX were 11% (baseline) versus 0% (kit) versus 9% (heightened awareness); pNXmed, 27% versus 1% versus 22%; CoC benchmark attainment, 14% versus 77% versus 30%; IASLC-defined R0 resection, 11% versus 58% versus 24%; NCCN attainment, 23% versus 79% versus 35%; (p:<0.001 for all, except pNX rate baseline versus heightened awareness). Survival rate was significantly higher for both interventions compared to baseline.

Conclusion

Resections with heightened awareness or the kit significantly improved surgical quality and outcomes, but the kit was more effective. We propose to conduct a prospective, institutional cluster randomized clinical trial comparing both interventions.

Keywords: lymph node specimen collection kit, quality of care, surgical resection, heightened awareness, American College of Surgeons Operative Standard 5.8

Introduction.

Surgical resection is the main treatment modality for early stage lung cancer, but aggregate long-term survival rates are only approximately 50%;1 20 to 40% of patients have disease recurrence within 4 years after surgery.2 For patients who undergo curative-intent resection, the pathologic nodal stage, as well as the quality of nodal evaluation are important prognostic factors.3,4 Patients with nodal metastasis have worse survival than those who do not, but they benefit from adjuvant therapy.5–8 However, the quality of pathologic nodal staging is highly variable, but generally poor.9–15

Patients with suboptimal nodal evaluation have worse survival than expected for stage.4,9,12,14–16 The Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) has proposed to include the quality of nodal evaluation in the residual disease (‘R-factor’) classification.17,18 In this proposal, resections with uninvolved margins but suboptimal nodal evaluation will be denoted as ‘R-uncertain’ rather than ‘complete’ (R0) because of their poorer outcomes.17–20 Furthermore, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC), in its new Operative Standard 5.8, has redefined good quality lung cancer surgery to require ‘evaluation of at least one named or numbered hilar lymph node and at least three named or numbered mediastinal lymph node stations’.21 This benchmark will be used to evaluate the quality of lung cancer surgery at CoC-accredited hospitals in the United States (US).

These policy changes heighten lung cancer surgery team members’ awareness of the pathologic nodal staging quality gap, but do not explain how to overcome it. Although heightened awareness is important in overcoming any problem, it may not be sufficient.22 Interventions that address the complex and multi-level etiology of poor pathologic nodal staging might be more effective in achieving sustained quality improvement. A lymph node specimen collection kit improved the quality and outcomes of lung cancer surgery in non-randomized studies.23–25 As a prelude to an institution-level cluster randomized comparative effectiveness trial of heightened awareness versus the kit, we modeled the impact of both interventions in a population-based observational surgical resection dataset.

Materials and Methods

The Mid-South Quality of Surgical Resection (MS-QSR) cohort.

From 2009 onward, the MS-QSR database has collected detailed information on all lung cancer resections performed in all eligible hospitals within four contiguous Dartmouth Hospital Referral Regions in Northern Mississippi, Eastern Arkansas, and Western Tennessee, states with the 2nd, 3rd and 4th-highest US per-capita lung cancer incidence and mortality rates.26 Eligible hospitals have 5 or more annual curative-intent lung cancer resections, representing >95% of all lung cancer surgery in the region.4,27,28 Thus the MS-QSR database enables detailed evaluation of the patterns of surgical care in this diverse, high-risk US population.

Lymph node specimen collection kit.

This is a box with 12 containers pre-labeled with the anatomic names and numbers of the hilar and mediastinal lymph node stations, using the IASLC lymph node map.29 One kit for right-side resections identified stations 2R,4R,7, 8,9 and 10R as ‘mandatory’ for examination; a kit for left-side resections identified stations 5,6,7,8,9 and 10L as mandatory.23,27 The kit also includes a check-list to remind the surgery team of these mandatory stations, as well as a diagram and anatomic description of the boundaries of the different lymph node stations.

Study design.

Using a non-randomized stepped-wedge approach, we implemented routine use of the kit for curative-intent NSCLC resections in all 12 MS-QSR hospitals.27 First, we retrospectively abstracted data on all lung cancer resections from 2009 to approximately 2014; then we confidentially shared with each institution’s senior administrators, surgeons, pathologists and cardiothoracic surgery operating room nursing staff, their institution’s baseline performance. The key benchmarks included the proportion of resections: without any lymph nodes examined (pNX);14 without mediastinal lymph nodes examined pNXmed;12 achieving the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,30,31 and then-current CoC-guidelines for surgical quality.32 At these meetings, we shared background information on the survival impact of these quality benchmarks, showed data on the kit’s impact on surgical quality, and developed a consensus implementation plan for deploying the kit within the institution.

We sequentially introduced the kit in participating hospitals using a staggered implementation approach that included a prospective observation baseline phase typically lasting about three months, during which we did not provide the kit, enabling us to observe the effect of heightened awareness of the pathologic nodal staging quality gap and recommended surgical quality benchmarks. Surgeons and their operating room teams were encouraged to use the kit for all lung cancer operations after it was introduced into their operating room package. From the point of institution and surgeon recruitment to participate in the surgical quality improvement project involving use of the kit, all subsequent lung cancer operations performed without the kit were identified as ‘heightened awareness’ cases. Therefore, we categorized resections into three groups: pre-implementation baseline; post-implementation kit; and post-implementation non-kit (‘heightened awareness’) cases.

Cohort selection.

The analysis cohort includes all lung cancer patients with a curative-intent resection. Only the first resection was considered, we excluded re-resections.

End-points.

We sought to determine the relative effect sizes of heightened awareness and the lymph node specimen collection kit by comparing measures of quality, upstaging from clinical to pathologic nodal stage, adjuvant therapy use, perioperative morbidity and mortality, and survival between baseline and intervention cohorts as well as between the two intervention cohorts. Lacking a universally-accepted quality benchmark, we compared survival-impactful extremes of poor quality, including pNX,14 pNXmed;12 as well as the proportions attaining survival-impactful quality standards set by the NCCN, 30,31 the new CoC Operative Standard 5.8,21 and the proposed IASLC R0 redefinition.18

The NCCN recommends the combination of negative margins, anatomic resection, examination of at least 1 hilar or intrapulmonary (N1) lymph node and at least 3 mediastinal lymph node stations.30 CoC Operative Standard 5.8 requires examination of at least 1 named or numbered hilar lymph node and at least 3 named or numbered mediastinal lymph node stations.21 The IASLC proposes to redefine R0 resection to include negative resection margins, systematic or lobe-specific nodal dissection, non-involvement of the highest mediastinal lymph node, and the absence of extracapsular lymph node invasion.18 Suboptimal nodal evaluation is the overwhelming cause of failure to achieve R0 resection by this definition.18,20

Statistical analysis.

We summarized demographic and clinical characteristics as proportions, frequencies, medians, and interquartile ranges. We used Chi-squared (Fisher’s exact test for small sample size), Kruskall-Wallis, Kaplan-Meier, and Cox regression analyses to examine differences in these characteristics and the quality metrics across the three cohorts. We estimated effect sizes by differences in proportions and (for survival) hazard ratios, with 95% confidence intervals. We calculated pair-wise effect size estimates for: proportions with extremely poor quality (pNX, pNXmed); and proportions attaining good quality benchmarks (NCCN, CoC Standard 5.8 and IASLC R0 resection). Confidence intervals excluding 0, for difference in proportions, or 1, for hazard ratios, indicate a significant effect size, unadjusted for multiple comparisons.

To support a future cluster-randomized study design, we examined the overall intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and ICC within each sub-cohort. We examined potential effect modification by institutional and surgeon factors (heterogeneity of treatment effects) by using logistic regression (Cox regression for survival) to model the interaction between cohort quality metrics, and institutional or surgeon characteristics. A significant interaction, determined by the overall Type III test, indicates a difference in the association between cohorts and quality metrics (pNX, pNXmed, NCCN, CoC and IASLC R0) among the institution or surgeon characteristic. A significant interaction indicates different odds (hazards of death for survival) of quality among cohorts across the different levels of that institution or surgeon characteristic. All analyses were performed at the alpha=0.05 significance level using SAS 9.4 (2013, SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC).

Sensitivity analyses.

As wedge resections are not consistently curative intent, we recalculated effect sizes with wedge resections excluded. Similarly, to account for the uneven distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics across the phases, we applied a stabilized inverse probability weight (SIPW) and re-estimated effect sizes33. SIPW is a type of propensity-adjusted analysis appropriate for considering potential confounders while also handling the various sample sizes of the three phases. This approach attempts to “balance” the phases which produces less biased estimates. Variables included in the adjustment were age, sex, race, insurance, PET-CT, invasive staging, extent of surgery, surgical technique, clinical T category, and clinical M category.

Results

Cohort characteristics.

From January 1, 2009 to February 17, 2020, 3734 patients underwent curative-intent surgical resection in the MS-QSR cohort, of which 39% (n=1454) were pre-intervention baseline; 40% (n=1509) had resection with the kit; and 21% (n=771) were post-intervention resections performed without the kit (‘heightened awareness’ cases). In this non-randomly allocated ‘real world’ population, the distribution of various patient-level demographic and clinical characteristics were somewhat dissimilar across all three cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics across pre-intervention baseline (baseline), post-implementation resections with kit (kit), and post-implementation resections performed without the kit, heightened awareness (HA).

| Characteristics* N (%) | Baseline | Kit | HA |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1454 | 1509 | 771 |

| Sex (p-value:<0.001) | |||

| Male | 876 (60) | 765 (51) | 405 (53) |

| Female | 578 (40) | 744 (49) | 366 (47) |

| Age (mean (sd); p-value: 0.0102) | 67.0 (9.2) | 67.7 (9.1) | 66.4 (9.6) |

| Race (p-value: <0.001) | |||

| White | 1162 (80) | 1200 (80) | 552 (72) |

| Black | 278 (19) | 292 (19) | 209 (27) |

| Other | 14 (1) | 17 (1) | 10 (1) |

| Insurance (p-value: 0.0052) | |||

| Medicare | 719 (49) | 718 (48) | 344 (45) |

| Medicaid | 185 (13) | 250 (17) | 122 (16) |

| Commercial | 490 (34) | 500 (33) | 285 (37) |

| Self-Insured/None | 60 (4) | 41 (3) | 20 (3) |

| Histology (p-value:<0.001) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 732 (50) | 865 (57) | 395 (51) |

| Squamous | 528 (36) | 480 (32) | 248 (32) |

| Other | 194 (13) | 164 (11) | 128 (17) |

| Clinical Tumor Size (p-value: 0.2139) | |||

| 0- <=3 cm | 909 (67) | 990 (68) | 489 (68) |

| >3- <=5 cm | 324 (24) | 349 (24) | 152 (21) |

| > 5cm | 131 (10) | 120 (8) | 78 (11) |

| PET-CT Scan (p-value: <0.001) | |||

| No | 258 (18) | 181 (12) | 155 (20) |

| Yes | 1196 (82) | 1328 (88) | 616 (80) |

| Invasively Staged (p-value: <0.001) | |||

| No | 1262 (87) | 1146 (76) | 601 (78) |

| Yes | 192 (13) | 363 (24) | 170 (22) |

| Clinical T (p-value:0.0002) | |||

| cTX/T0/Tis/T1 | 753 (52) | 877 (58) | 439 (57) |

| cT2 | 361 (25) | 348 (23) | 156 (20) |

| cT3 | 159 (11) | 160 (11) | 83 (11) |

| cT4 | 112 (8) | 87 (6) | 50 (6) |

| Unknown | 69 (5) | 37 (2) | 43 (6) |

| Clinical N (p-value: 0.0002) | |||

| cN0 | 1241 (85) | 1375 (91) | 688 (89) |

| cN1 | 105 (7) | 73 (5) | 39 (5) |

| cN2 | 95 (7) | 52 (3) | 38 (5) |

| cN3 | 11 (1) | 5 (0) | 2 (<1) |

| Unknown | 2 (0) | 4 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Clinical M (p-value: 0.7307) | |||

| cM0/Unknown | 1418 (98) | 1474 (98) | 748 (97) |

| cM1a | 13 (1) | 12 (1) | 7 (1) |

| cM1b | 20 (1) | 22 (1) | 16 (2) |

| cM1c | 3 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Clinical Stage (p-value:<0.001) | |||

| Occult carcinoma/Stage 0/Stage I | 864 (59) | 1040 (69) | 497 (65) |

| Stage II | 268 (18) | 251 (17) | 119 (15) |

| Stage III | 216 (15) | 147 (10) | 88 (11) |

| Stage IV | 36 (2) | 35 (2) | 23 (3) |

| Stage unknown | 70 (5) | 36 (2) | 44 (6) |

| Pathologic T (p-value:0.0030) | |||

| pTX/T0/Tis | 14 (1) | 20 (1) | 14 (2) |

| pT1 | 597 (41) | 705 (47) | 367 (48) |

| pT2 | 522 (36) | 514 (34) | 236 (31) |

| pT3 | 211 (15) | 193 (13) | 109 (14) |

| pT4 | 110 (8) | 77 (5) | 45 (6) |

| Pathologic N (p-value:<0.001) | |||

| pNX | 161 (11) | 1 (0) | 72 (9) |

| pN0 | 994 (68) | 1197 (79) | 552(72) |

| pN1 | 185 (13) | 180 (12) | 85 (11) |

| pN2 | 113 (8) | 131 (9) | 62 (8) |

| pN3 | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pathologic M (p-value: 0.023) | |||

| pM0 | 1439 (99) | 1487 (99) | 754 (98) |

| pM1a | 6 (0) | 2 (0) | 5 (1) |

| pM1b | 8 (1) | 20 (1) | 11 (1) |

| pM1c | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Pathologic Stage (p-value:0.0057) | |||

| Occult carcinoma/Stage 0 | 25 (2) | 18 (1) | 25 (3) |

| Stage I | 844 (58) | 921 (61) | 464 (60) |

| Stage II | 328 (23) | 322 (21) | 152 (20) |

| Stage III | 242 (17) | 226 (15) | 113 (15) |

| Stage IV | 15 (1) | 22 (1) | 17 (2) |

| Change in nodal staging (clinical to pathologic) (p-value:<0.001) | |||

| down stage | 107 (7) | 63 (4) | 49 (6) |

| no change | 980 (67) | 1197 (79) | 533 (69) |

| up stage | 204 (14) | 244 (16) | 113 (15) |

| unknown | 163 (11) | 5 (0) | 76 (10) |

| Tumor size (p-value:0.0003) | |||

| 0- <=3 cm | 882 (61) | 1031 (68) | 503 (65) |

| >3- <=5 cm | 380 (26) | 315 (21) | 165 (21) |

| >5 cm | 192 (13) | 163 (11) | 103 (13) |

| Extent of resection (p-value: <0.001) | |||

| Pneumonectomy | 101 (7) | 48 (3) | 46 (6) |

| Bilobectomy | 89 (6) | 62 (4) | 21 (3) |

| Lobectomy | 1011 (70) | 1307 (87) | 560 (73) |

| Segmentectomy | 60 (4) | 45 (3) | 56 (7) |

| Wedge | 193 (13) | 47 (3) | 87 (11) |

| Surgical Technique (p-value: <0.001) | |||

| Open | 1117 (77) | 699 (46) | 344 (45) |

| RATS | 97 (7) | 637 (42) | 290 (38) |

| VATS | 240 (17) | 173 (11) | 137 (18) |

| Margins (p-value: 0.0018) | |||

| Positive | 85 (6) | 55 (4) | 36 (5) |

| Negative | 1345 (93) | 1446 (96) | 727 (94) |

| Not reported | 24 (2) | 8 (1) | 8 (1) |

sd- standard deviation.

Quality of surgical resection.

Cohort proportions with pNX were 11% (baseline) versus 0% (kit) versus 9% (heightened awareness); pNXmed were 27% versus 1% versus 22%; proportions attaining the NCCN benchmark were 23% versus 80% versus 36%; the CoC benchmark, 14% versus 77% versus 30%; and the IASLC-defined R0 resection, 11% versus 58% versus 24%; p<0.001 for all comparisons (Table 2).

Table 2.

Measures of quality across pre-intervention baseline (baseline), post-implementation resections with kit (kit), and post-implementation resections performed without the kit, heightened awareness (HA) and pairwise effect sizes measured as differences in proportions with 95% confidence intervals among the three cohorts.

| Measures of Quality* | Baseline† | Kit† | HA† | P-value‡ | Kit versus Baseline | Kit versus HA | HA versus Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1454 | 1509 | 771 | ||||

| pNX | 161 (11) | 1 (0) | 72 (9) | <0.001 | −0.11 (−0.13, −0.09) | −0.09 (−0.11, −0.07) | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.01) |

| pNXmed | 386 (27) | 16 (1) | 166 (22) | <0.001 | −0.25 (−0.28, −0.23) | −0.2 (−0.23, −0.18) | −0.05 (−0.09, −0.01) |

| NCCN Aggregate | 331 (23) | 1201 (80) | 275 (36) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.54, 0.6) | 0.44 (0.4, 0.48) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17) |

| Negative margins | 1369 (94) | 1454 (96) | 735 (95) | 0.0184 | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) |

| Anatomic resection | 1261 (87) | 1462 (97) | 683 (89) | <0.001 | 0.1 (0.08, 0.12) | 0.08 (0.06, 0.11) | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.05) |

| Hilar lymph node examined | 1175 (81) | 1461 (97) | 653 (85) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.14, 0.18) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.15) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07) |

| ≥3 mediastinal node stations | 385 (26) | 1304 (86) | 306 (40) | <0.001 | 0.6 (0.57, 0.63) | 0.47 (0.43, 0.51) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17) |

| CoC | 206 (14) | 1157 (77) | 232 (30) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.54, 0.6) | 0.44 (0.4, 0.48) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17) |

| IASLC R-factor | |||||||

| Complete | 161 (11) | 881 (58) | 185 (24) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.44, 0.5) | 0.34 (0.3, 0.38) | 0.13 (0.1, 0.16) |

| Incomplete | 85 (6) | 55 (4) | 36 (5) | 0.0184 | −0.02 (−0.04, −0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) |

| Uncertain | 1208 (83) | 573 (38) | 550 (71) | <0.001 | −0.45 (−0.48, −0.42) | −0.33 (−0.37, −0.29) | −0.12 (−0.15, −0.08) |

pNX - non-examination of lymph nodes; pNXmed - non-examination of mediastinal lymph nodes; NCCN - National Comprehensive Cancer Network; CoC - American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer; IASLC R-factor - International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer residual disease classification.

Numbers in parentheses are percentages.

P-value from Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test comparing quality metrics across the cohorts, bolded indicates significance at the α=0.05 level.

Nodal upstaging rates, eligibility and use of adjuvant therapy.

Rates of up-staging from clinical to pathological stage were 14% versus 16% versus 15% and proportions given adjuvant chemotherapy were 15% versus 22% and 15%, p<0.001 for both comparisons. Rates of chemotherapy among patients with pT2b or greater were 29% versus 25% versus 25%, p=0.0092. There were no significant differences in other eligibility criteria for adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rates of adjuvant therapy eligibility and utilization across pre-intervention baseline (baseline), post-implementation resections with kit (kit), and post-implementation resections performed without the kit, heightened awareness (HA).

| Eligibility and Utilization Metrics N(%) | Baseline | Kit | HA | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in nodal staging (clinical to pathologic) | <0.001 | |||

| down stage | 107 (7) | 63 (4) | 49 (6) | |

| no change | 980 (67) | 1197 (79) | 533 (69) | |

| up stage | 204 (l4) | 244 (16) | 113 (15) | |

| unknown | 163 (11) | 5 (0) | 76 (10) | |

| Eligible for chemotherapy | ||||

| Upstaged from cN0 to pN1, 2, or 3 | 187 (13) | 230 (15) | 110 (14) | 0.1754 |

| pT2b or greater | 427 (29) | 371 (25) | 196 (25) | 0.0092 |

| pN1-3 and/or pT2b or greater | 519 (36) | 518 (34) | 260 (34) | 0.5916 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 217 (15) | 311 (22) | 110 (15) | <0.001 |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy | 76 (5) | 70 (5) | 31 (4) | 0.4315 |

P-value from Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test comparing metrics across the cohorts, bolded values indicate significance at the α=0.05 level.

Perioperative morbidity, mortality, utilization of healthcare and survival.

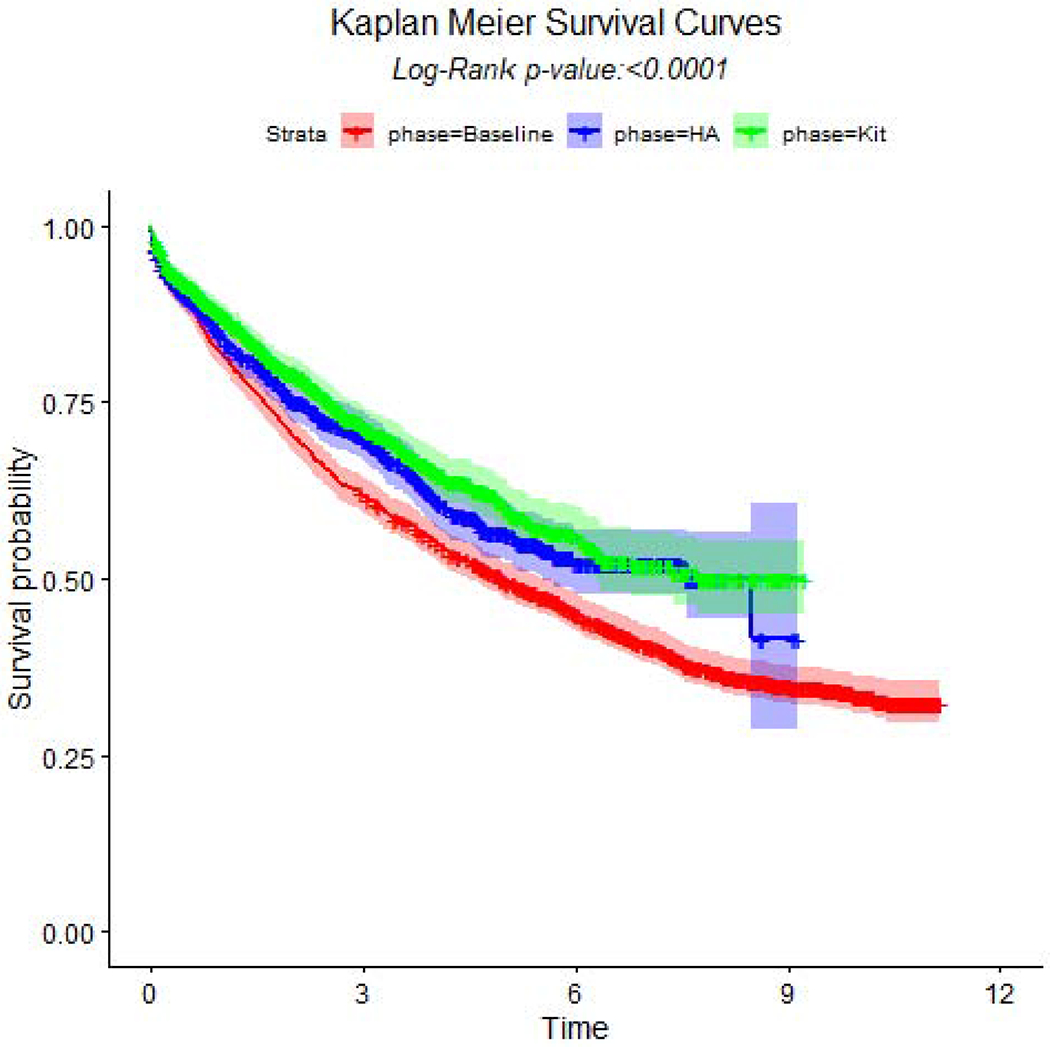

The duration of surgery was shortest for kit resections (medians: 138 versus 125 versus 144), which also had a lower number of post-operative complications (51% versus 47% versus 52%) such as atelectasis (22% versus 18% versus 22%) (Table 4). Additionally, rates of bronchopleural fistula, respiratory failure, and adult respiratory distress syndrome significantly differed across the groups. No other complications were statistically significant. Duration of chest tube drainage, duration of Intensive Care Unit and hospital admission were also all shorter among kit and heightened awareness resections (Table 4). Although 30-day mortality rate was lowest among kit resections, 60-, 90- and 120-day mortality rates were not significantly different (Table 4). The median duration of survival was 4.96 years (95% confidence interval: 4.48, 5.51) versus 7.7 (6.2, not reached) versus 7.6 (5.5, not reached) (p<0.0001, Figure 1).

Table 4.

Perioperative morbidity and mortality summary across pre-intervention baseline (baseline), post-implementation resections with kit (kit), and post-implementation resections performed without the kit, heightened awareness (HA).

| Perioperative complications | Baseline | Kit | HA | P-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1454 | 1509 | 771 | |

| Duration of surgery, minutes* | 138 (95-187), (19-615) | 125 (89-177), (3-641) | 144 (107-195), (16-727) | <0.001 |

| Number with any post-operative complications‡ | 740 (51) | 709 (47) | 399 (52) | 0.0385 |

| Number of post-operative complications* | 1 (0-1), (0-6) | 0 (0-1), (0-6) | 1 (0-1), (0-6) | 0.0296 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias‡ | 248 (17) | 229 (15) | 104 (13) | 0.0756 |

| Atelectasis‡ | 319 (22) | 277 (18) | 168 (22) | 0.0318 |

| Pneumonia‡ | 72 (5) | 53 (4) | 34 (4) | 0.1481 |

| Rate of reoperation‡ | 14 (1) | 9 (1) | 1 (0) | 0.0620 |

| Rate of intraoperative blood transfusion‡ | 107 (7) | 109 (7) | 42 (5) | 0.1969 |

| Empyema‡ | 5 (0) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 0.5307 |

| Chylothorax‡ | 1 (0) | 7 (0) | 2 (0) | 0.1079 |

| Bronchopleural fistula‡ | 11 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (0) | 0.0121 |

| Increased lymphatic bleeding‡ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Air leak > 7 days‡ | 105 (7) | 121 (8) | 69 (9) | 0.3471 |

| Respiratory failure‡ | 282 (19) | 331 (22) | 215 (28) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction‡ | 14 (1) | 6 (0) | 4 (1) | 0.1396 |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome‡ | 23 (2) | 11 (1) | 3 (0) | 0.0107 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury‡ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Increased lymphatic drainage‡ | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| ICU readmittance‡ | 77 (5) | 68 (5) | 39 (5) | 0.5585 |

| Hospital readmittance within 60 day‡ | 183 (13) | 230 (16) | 90 (12) | 0.0064 |

| Duration of chest tube drainage, days* | 5 (3-7), (1-370) | 3 (2-6), (0-101) | 4 (2-7), (0-734) | <0.001 |

| ICU length of stay, days* | 2 (1-3), (0-367) | 1 (1-2), (0-43) | 2 (1-3), (0-45) | <0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, days* | 7 (5-11), (0-171) | 5 (3-8), (0-385) | 5 (3-9), (0-82) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | ||||

| 30-day mortality | 66 (5) | 42 (3) | 37 (5) | 0.0158 |

| 60-day mortality | 86 (6) | 69 (5) | 53 (7) | 0.0586 |

| 90-day mortality | 115 (8) | 102 (7) | 64 (8) | 0.3253 |

| 120-day mortality | 131 (9) | 130 (9) | 76 (10) | 0.6188 |

median (interquartile range), (range)

frequency (percentage).

P-value from Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test comparing metrics across the cohorts, bolded values indicate significance at the α=0.05 level.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank test across pre-intervention baseline (baseline), post-implementation resections with kit (kit), and post-implementation resections performed without the kit, heightened awareness (HA).

Effect size estimates.

Compared to baseline, the kit was very effective in improving all five quality benchmarks and survival; heightened awareness improved most quality benchmarks, except pNX (Table 2). The kit was more effective than heightened awareness, with a strong trend towards comparative survival benefit (unadjusted hazard ratio 0.9 [0.8 – 1.0]). After removing wedge resections, effect sizes remained similar (Tables 2A–4A). Also, after applying the SIPWs, effect sizes varied minimally (Tables 5A–7A).

Heterogeneity of treatment effects.

Of 12 participating institutions, two were CoC-designated Academic Cancer Programs, three were Comprehensive Community Cancer Programs, and seven were non-accredited and non-teaching; three were located in rural areas. There were 54 surgeons (42 cardiothoracic, 8 general thoracic and 4 general), with a median of 28 years of post-training experience (interquartile range: 15-40 years). The overall ICC across all institutions was 0.0155 (interquartile range: 0.005-0.0256), the ICC for each sub-cohort was 0.0311 (0.0155-0.0358) versus 0.0288 (0.0029-0.055) versus 0.0395 (0.0159-0.081), respectively.

Institutional CoC designation status, rurality, teaching status, and bed size, as well as surgeon board certification or practice focus and years of post-training experience were significant but varied effect modifiers on the different quality metrics. Only institutional teaching status was an effect modifier for survival (Table 5 [summary]; Table A.1a and Table A.1b [stratified odds and hazard ratios]).

Table 5.

Summary of significant effect modifiers between institution/surgeon characteristics and cohort when predicting selected quality metrics.

| Quality metric* (outcome) | CoC Designations | Institutional Rurality | Institutional Teaching | Bed Size | Board Certification | Surgeon Service Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pNX | 0 | X | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pNXmed | X | X | X | 0 | X | X |

| NCCN | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| CoC | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Complete resections | X | 0 | 0 | X | 0 | X |

| Uncertain resections | X | X | 0 | X | 0 | X |

| Survival | 0 | 0 | X | 0 | 0 | 0 |

X indicates a significant Type III interaction between cohort and that specific institutional/surgeon characteristic, no other adjustment variables were included in the model; pNX - non-examination of lymph nodes; pNXmed - non-examination of mediastinal lymph nodes; NCCN - National Comprehensive Cancer Network; CoC - American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer; IASLC R-factor - International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer residual disease classification.

Discussion.

In this population-based observational cohort, non-randomized stepped-wedge implementation of ‘heightened awareness’ and a lymph node specimen collection kit significantly improved the quality of surgical resection and pathologic nodal staging of potentially curable lung cancer, without increasing the surgical complications or perioperative morbidity or mortality. However, the kit was comparatively more effective than heightened awareness: reducing the proportion of extremely poor quality- pNX and pNXmed- from 10 to 0% (effect size −0.1) and 22 to 1% (effect size −0.21), respectively; and increasing the proportions achieving recommended quality such as the NCCN, CoC and IASLC R0 redefinition, with effect sizes of 0.44, 0.44 and 0.34, respectively. Despite this striking improvement in quality between heightened awareness and kit resections, the lower hazard ratio was not statistically significant, although there was a strong trend towards a comparative survival benefit, with unadjusted hazard ratio of 0.9 (95% confidence interval 0.8 to 1.0).

The ‘chain of responsibility’ conceptual model presents pathologic nodal staging quality as a shared responsibility, requiring serial hand-offs from the operating room team (retrieval of lymph nodes from recommended stations and accurate specimen labeling), specimen transportation team (secure transfer from the operating room to the pathology laboratory), and pathology team (thorough examination and accurate reporting). This chain of responsibility, like any chain, is only as strong as its weakest link. We hypothesize that heightened awareness, without tangible tools to strengthen the chain, would be less effective than the kit which is designed to achieve this. We have previously reported on the efficacy of the kit in improving the lymph node and station counts in lung resection specimens, as well as the concordance between surgeons and pathologists in identifying the lymphadenectomy procedure performed.23–25

Heightened awareness of the lung cancer pathologic nodal staging quality gap is becoming prevalent worldwide.16,34,35 In the US, the CoC has already established new definitions for lung cancer quality, no longer the somewhat arbitrary requirement for 10 or more lymph nodes for pathologic stage I and II non-small cell lung cancer (without regard for anatomic source), to a specific requirement for examination of lymph nodes from anatomically identified hilar and a minimum of 3 mediastinal nodal stations.21 This new standard was approved for implementation at all CoC-accredited programs in 2020, with enforcement starting in January 2021. The expectation is for 70% compliance in 2021, and 80% compliance from 2022 onward.36 The European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) has defined acceptable quality standards for nodal dissection as systematic and lobe-specific nodal dissection.37 The ESTS nodal dissection standards are incorporated in the proposed IASLC R-factor re-categorization, the prognostic value of which has been independently validated in three different datasets.17–20 Failure to achieve nodal quality standards is the overwhelming reason for re-categorization of resections from R0 to ‘R-uncertain’ in the IASLC R-factor classification.18–20 These developments are likely to raise the worldwide profile of the pathologic nodal staging quality gap with attendant pressure for improvement.

The main limitations of this report are the non-randomized study design, which opens up the possibility of bias and confounding, and the regional nature of the MS-QSR, which raises legitimate questions about the generalizability of the baseline quality gap and the intervention effects. However, we sought to estimate the comparative effect size of each intervention in preparation for a proposed institutional cluster randomized trial. We plan to use these effect size estimates for sample size and statistical power projections for a prospective, institutional cluster randomized comparative effectiveness clinical trial of the kit versus heightened awareness. Such a randomized trial is needed to provide ‘category 1’ evidence to support lung cancer surgery teams and institutions as they strive to achieve the emerging standards that are likely to be enforced over the coming years. We found surgeon and institution-level effect modifiers on the surgical quality and outcomes impact of the interventions, suggesting the need to also evaluate the heterogeneity of treatment effects between different types of surgeons and institutions. Because the generalizability of our findings is questionable, we can be at equipoise in proposing such an institutional randomized clinical trial.

In summary, heightened awareness of recommended quality standards, without providing a tangible means of simplifying, securing and standardizing the processes involved from the intraoperative lymph node retrieval to publication of the final pathology report, may not be as effective as a surgical lymph node specimen collection kit. The survival impact of improved quality attainment with a lymph node collection kit needs further evaluation in a randomized controlled trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

The US National Institutes of Health for funding support for the MS-QSR (1 R01 CA172253, 2 R01 CA172253); members of Dr. Osarogiagbon’s Thoracic Oncology Research Group over the years, including medical students, residents and fellows; regional hospital administrators, surgeons and pathologists who have participated in the MS-QSR project over the years; lung cancer surgery patients, around whom this this is all centered.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R01 CA172253].

Conflicts of interest:

Dr. Osarogiagbon owns patents for the lymph node specimen collection kit; owns stocks in Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, and Pfizer; has worked as a paid research consultant for the American Cancer Society, the Association of Community Cancer Centers, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche and Triptych Healthcare Partners; and is founder of Oncobox Device, Inc. Dr. Smeltzer received a grant from the Association of Community Cancer Centers. No other authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pfannschmidt J, Muley T, Bulzebruck H, Hoffmann H, Dienemann H. Prognostic assessment after surgical resection for non-small cell lung cancer: experiences in 2083 patients. Lung Cancer 55:371–377, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lou F, Sima CS, Rusch VW, Jones DR, Huang J. Differences in patterns of recurrence in early-stage versus locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014. November;98(5):1755–60; discussion 1760-1. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.070. Epub 2014 Aug 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asamura H, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Lung Cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming 8th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 10:1675–1684, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smeltzer MP, Faris NR, Ray MA, Osarogiagbon RU. Association of pathologic nodal staging quality with survival among patients with non-small cell lung cancer after resection with curative intent. JAMA Oncol 4:80–87, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J; International Adjuvant Lung Cancer Trial Collaborative Group. Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004. January 22;350(4):351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, et al. ; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group; National Cancer Institute of the United States Intergroup JBR.10 Trial Investigators. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al. ; LACE Collaborative Group. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3552–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kris MG, Gaspar LE, Chaft JE, et al. Adjuvant systemic therapy and adjuvant radiation therapy for stage I to IIIA completely resected non-small-cell lung cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology/Cancer Care Ontario Clinical Practice Guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35:2960–2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig MS, Goodman M, Miller DL, Johnstone PA. Postoperative survival and the number of lymph nodes sampled during resection of node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005. September;128(3):1545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little AG, Rusch VW, Bonner JA, et al. Patterns of surgical care of lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg 80:2051–2056, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen JW, Farooq A, O’Brien TF, Osarogiagbon RU. Quality of surgical resection for nonsmall cell lung cancer in a US metropolitan area. Cancer 117:134–142, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osarogiagbon RU, Yu X. Mediastinal lymph node examination and survival in resected early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Thorac Oncol 7:1798–1806, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhagen AF, Schoenmakers MC, Barendregt W, et al. Completeness of lung cancer surgery: is mediastinal dissection common practice? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 41:834–838, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osarogiagbon RU, Yu X. Nonexamination of lymph nodes and survival after resection of non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 96:1178–1189, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osarogiagbon RU, Ogbata O, Yu X. Number of lymph nodes associated with maximal reduction of long-term mortality risk in pathologic node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 97:385–393, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang W, He J, Shen Y, et al. Impact of examined lymph node count on precise staging and long-term survival of resected non-small-cell lung cancer: a population study of the US SEER database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. J Clin Oncol 35:1162–1170, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rami-Porta R, Wittekind C, Goldstraw P; International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Staging Committee. Complete resection in lung cancer surgery: proposed definition. Lung Cancer. 2005. July;49(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards JG, Chansky K, Van Schil P, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: analysis of resection margin status and proposals for residual tumor descriptors for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 15:344–359, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagliasso M, Migliaretti G, Ardissone F. Assessing the prognostic impact of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer proposed definitions of complete, uncertain, and incomplete resection in non-small cell lung cancer surgery. Lung Cancer. 2017. September;111:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osarogiagbon RU, Faris NR, Stevens W, et al. Beyond Margin Status: Population-Based Validation of the Proposed International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Residual Tumor Classification Recategorization. J Thorac Oncol. 2020. March;15(3):371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.11.009. Epub 2019 Nov 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Commission on Cancer. Optimal Resources for Cancer Care. Patient care: Expectations and Protocols. 5.8 Pulmonary resection. Page 65. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/cancer/coc/optimal_resources_for_cancer_care_2020_standards.ashx. (accessed April 18, 2020).

- 22.Smeltzer MP, Faris NR, Ray MA, et al. Survival Before and After Direct Surgical Quality Feedback in a Population-Based Lung Cancer Cohort. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019. May;107(5):1487–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.11.058. Epub 2018 Dec 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osarogiagbon RU, Miller LE, Ramirez RA, et al. Use of a surgical specimen-collection kit to improve mediastinal lymph-node examination of resectable lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012. August;7(8):1276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osarogiagbon RU, Sareen S, Eke R, et al. Audit of lymphadenectomy in lung cancer resections using a specimen collection kit and checklist. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015. February;99(2):421–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray MA, Faris NR, Smeltzer MP, et al. Effectiveness of implemented interventions on pathologic nodal staging of non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018. March 10. pii: S0003-4975(18)30333-3. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.02.021. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020. January;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. Epub 2020 Jan 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osarogiagbon RU, Smeltzer MP, Faris NR, et al. Pragmatic Study of a Lymph Node (LN) Collection Kit for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Resection. J Clin Oncol 36, 2018. (suppl; abstr 8502). Oral session abstract selected as ‘Best of ASCO 2018.’ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray MA, Smeltzer MP, Faris NR, Osarogiagbon RU. Survival After Mediastinal Node Dissection, Systematic Sampling, or Neither for Early Stage NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2020. June 20:S1556-0864(20)30479-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.009. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 4:568–577, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Accessed on October 26, 2020, at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf

- 31.Osarogiagbon RU, Ray MA, Faris NR, et al. Prognostic Value of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Lung Cancer Resection Quality Criteria. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017. May;103(5):1557–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.01.098. Epub 2017 Mar 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Commission on Cancer. Cancer Programs Practice Profile Reports (CP3R). Lung measure specifications. Accessed on 02.08.16 at https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/lungmeasuredocumentation_05272015.ashx

- 33.Robins JM, Herman MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000; 550–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osarogiagbon RU, Smeltzer MP, Faris N, Rami-Porta R, Goldstraw P, Asamura H. Comment on the proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 11:1612–1614, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heineman DJ, Ten Berge MG, Daniels JM, et al. The quality of staging non-small cell lung cancer in the Netherlands: data from the Dutch lung surgery audit. Ann Thorac Surg 102:1622–1629, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Surgeons. What Registrars, Pathologists and Surgeons Need to Know about the CoC Operative Standards. Available at: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/news/css-120720 Accessed on December 18, 2020.

- 37.Lardinois D, De Leyn P, Van Schil P, et al. ESTS guidelines for intraoperative lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006. November;30(5):787–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.08.008. Epub 2006 Sep 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.