Sporotrichosis is an emerging mycosis caused by members of the genus Sporothrix. The disease affects humans and animals, particularly cats, which play an important role in zoonotic transmission.

KEYWORDS: acylhydrazone derivatives, Sporothrix brasiliensis, Sporothrix schenckii, cutaneous sporotrichosis, antifungals, mice

ABSTRACT

Sporotrichosis is an emerging mycosis caused by members of the genus Sporothrix. The disease affects humans and animals, particularly cats, which play an important role in zoonotic transmission. Feline sporotrichosis treatment options include itraconazole (ITC), potassium iodide, and amphotericin B, drugs usually associated with deleterious adverse reactions and refractoriness in cats, especially when using ITC. Thus, affordable, nontoxic, and clinically effective anti-Sporothrix agents are needed. Recently, acylhydrazones (AH), molecules targeting vesicular transport and cell cycle progression, exhibited a potent antifungal activity against several fungal species and displayed low toxicity compared to the current drugs. In this work, the AH derivatives D13 and SB-AF-1002 were tested against Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. MICs of 0.12 to 1 μg/ml were observed for both species in vitro. D13 and SB-AF-1002 showed an additive effect with itraconazole. Treatment with D13 promoted yeast disruption with the release of intracellular components, as confirmed by transmission electron microscopy of S. brasiliensis exposed to the AH derivatives. AH-treated cells displayed thickening of the cell wall, discontinuity of the cell membrane, and an intense cytoplasmic degeneration. In a murine model of sporotrichosis, treatment with AH derivatives was more efficient than ITC, the drug of choice for sporotrichosis. Our results expand the antifungal broadness of AH derivatives and suggest that these drugs can be exploited to combat sporotrichosis.

INTRODUCTION

Sporotrichosis is an implantation mycosis caused by the genus Sporothrix. The major species include S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, S. mexicana, S. chilensis, S. luriei, and S. pallida. Members of this genus are thermodimorphic, inhabiting soil and decomposing plant matter worldwide (1, 2). Usually, sporotrichosis infection results from traumatic inoculation of filamentous propagules from environmental sources. For this reason, sporotrichosis was traditionally associated with people who had direct contact with plants and soil. However, an increasing number of cases have been associated with zoonotic transmission, particularly from cats infected with S. brasiliensis. This species has important virulence attributes, such as higher expression of melanin and urease, being the most virulent species in murine models and frequently associated with more severe clinical presentations in humans, such as disseminated infection and hypersensitivity reactions (3, 4).

Brazil has a high prevalence of sporotrichosis caused by S. brasiliensis, which emerged as the principal etiological agent of sporotrichosis in the last 2 decades (5–7). In Rio de Janeiro, the main referral center for the treatment of sporotrichosis, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), recorded ≈5,000 human cases during 1998 to 2015 and 5,113 feline cases during 1998 to 2018 (8). In addition, the occurrence of zoonotic sporotrichosis due to S. brasiliensis was also reported in other states, such as Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Bahia, Rio Grande do Sul, Mato Grosso do Sul, and Pernambuco (8–10), indicating a propagation of this virulent species in almost all Brazilian regions, and it is expanding to the northeast states and even to other regions of Latin America, as it has recently been reported in Argentina (11, 12). Zoonotic sporotrichosis has also been reported in Panama, Mexico, the United States, India, and Malaysia (8). In Malaysia, isolates from cases caused by S. schenckii (13) involved clonal reproduction, which indicates the continued emergence of a genotype that is adapting to the feline host (14), comparable to that reported for S. brasiliensis in Brazil (15).

Itraconazole (ITC) is the first choice for treatment of human and feline cutaneous sporotrichosis (1, 16). However, reports of strains less sensitive to ITC are increasing (17, 18), as are refractory cases, especially in cats (19–21). Indeed, in feline sporotrichosis, the therapeutic options available are potassium iodide (KI) and amphotericin B (AmB), the last one mainly indicated for disseminated sporotrichosis (19, 22–24). In addition to the variable occurrence of acute or chronic adverse reactions, these drugs also have limitations in their use due to low effectiveness and/or high cost (21, 25). The treatment of feline sporotrichosis is a challenge in many cases (26), including a limited number of oral antifungal agents and reports of therapeutic failure and recrudescence, even when established therapeutic protocols are used (27).

It is imperative to find new alternatives with higher efficiency and lower toxicity for the treatment of sporotrichosis. The family of acylhydrazones (AH), molecules that target vesicular transport and the cell cycle progression of fungi and indirectly impact glucosylceramide (GlcCer) synthesis, are new alternatives to be exploited. Derivatives with very low toxicity to mammals include BHBM [2-methyl-N′-(2,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)-benzohydrazide], D13 [4-bromo-N′-(3,5-dibromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)-benzohydrazide], and SB-AF-1002 [2,4-dibromo-N′-(5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzylidene)-benzohydrazide], which also showed potent broad-spectrum antifungal activities with very high specificity (28–31). The bioactive acylhydrazone core is one of the most ubiquitous functional groups in medicinal chemistry, and it has been identified in numerous compounds that act on various types of molecular targets (29, 32). However, the activity of AH derivatives has not been tested against Sporothrix spp. In this study, we investigated the in vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of D13 and SB-AF-1002 against S. schenckii and S. brasiliensis, the major causative agents of sporotrichosis.

RESULTS

Antifungal activity.

D13 and SB-AF-1002 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) showed efficacy in inhibiting the growth of both S. brasiliensis and S. schenckii, with MICs ranging from 0.25 to 1 μg/ml and 0.12 to 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. These values were lower than those observed for BHBM (Fig. S1) and ITC (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inhibitory activity of AH derivatives against Sporothrix spp.

| Strain | MIC50 (μg/ml) |

MIC99 (μg/ml) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHBM | D13 | SB-AF-1002 | ITC | BHBM | D13 | SB-AF-1002 | ITC | |

| Sporothrix brasiliensis ATCC 5110 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Sporothrix schenckii ATCC 1099-18 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

In vitro combination of AH derivatives with itraconazole.

To investigate the use of AH derivatives combined with itraconazole as an alternative treatment against Sporothrix spp., the synergistic effect was tested using the checkerboard method. We observed a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) of >0.5 to 4 for all experiments, consisting of an indifferent or noninteractive effect (Table 2). However, considering that the AH derivatives have a mechanism of action that is distinct from that of azoles, we also used the Bliss method to investigate drug combinations. Additive interactions (scores between −0.28 and −0.99) were observed for all combinations (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

In vitro combination of AH derivatives and itraconazole against Sporothrix spp.

| Sporothrix spp.-drug combination | Checkerboard test |

Bliss method |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Σ FIC | Activity | Score | Activity | |

| S. brasiliensis ATCC 5110 | ||||

| D13-itraconazole | 1.37 ± 0.37 | Indifferent | −0.999 | Additive |

| SB-AF-1002-itraconazole | 1.36 ± 0.45 | Indifferent | −0.334 | Additive |

| S. schenckii ATCC 1099-18 | ||||

| D13-itraconazole | 1.63 ± 0.23 | Indifferent | −0.535 | Additive |

| SB-AF-1002-itraconazole | 1.12 ± 0.10 | Indifferent | −0.285 | Additive |

AH derivatives promote yeast disruption and ultrastructural changes in S. brasiliensis.

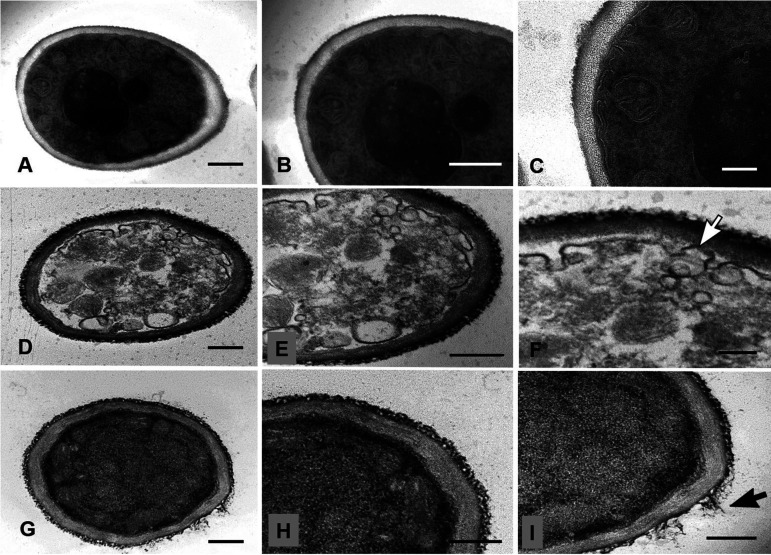

To investigate structural changes caused by AH exposure, we first evaluated the Golgi architecture using NBD C6-ceramide (NBD-Cer) and then the fungal ultrastructure by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). BHBM treatment was accompanied by an increase of NBD-Cer intensity of staining, suggesting vesicle accumulation, but without detectable morphological changes in the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 1). We observed the aggregation of yeasts and a diffuse labeling of the Golgi apparatus after D13 treatment. In addition, we also visualized a deposition of fluorescent material surrounding the yeast cells, suggesting that D13 promotes the extravasation of cytoplasmic components. The morphological analysis of yeasts of S. brasiliensis treated with D13 suggested the leakage of intracellular material through pores at the cell wall, indicating its discontinuity (Fig. 1, inset). Similar results were visualized by TEM. Fungal cells incubated in RPMI presented intact and well-defined organelles, showing uniform bilayered membranes and typical cell walls (Fig. 2A to C). In contrast, treatment with D13 (Fig. 2D to F) promoted damage to different organelles, vesicle accumulation, and discontinuity of the plasma membrane. Similar changes were observed after the treatment of S. brasiliensis with SB-AF-1002 (Fig. 2G to I). In addition to the intracellular damage, yeasts treated with this derivative showed a detachment of the outer layer of the cell wall.

FIG 1.

Effect of AH derivatives on Golgi apparatus and related morphology and distribution. Control or AH-treated yeasts of S. brasiliensis (A) and S. schenckii (B) were incubated with NBD-Cer. DIC, differential interference contrast; Uvitex, chitin layer (blue fluorescence); NBD-Cer, Golgi and Golgi-derived compartments (green fluorescence). (C) Cellular fluorescence intensity of each treatment. The inset in panel A shows a merged labeling of S. brasiliensis with a small hole in the chitin layer, depicting the point of extravasation of intracellular material (white arrow). Bars: black, 10 μm; white, 2 μm.

FIG 2.

Ultrastructural analysis of Sporothrix brasiliensis treated with AH derivatives. S. brasiliensis ATCC 5110 cells treated for 48 h with subinhibitory concentrations of AH derivatives were analyzed by TEM. (A to C) Untreated cells exhibited compact and homogeneous cell wall, intact plasma membrane, and organelles. (D to F) Yeast treated with D13 (0.25 μg/ml) showed intense intracellular damage, vesicle accumulation, and discontinuous plasma membrane (white arrow). (G to I) Cells treated with SB-AF-1002 (0.12 μg/ml) exhibited cytoplasm without well-defined organelles and cell wall detachment (black arrow). Bars, 500 nm (A, B, D, E, G, and H) and 200 nm (C, F, and I).

D13 and SB-AF-1002 are effective against murine sporotrichosis.

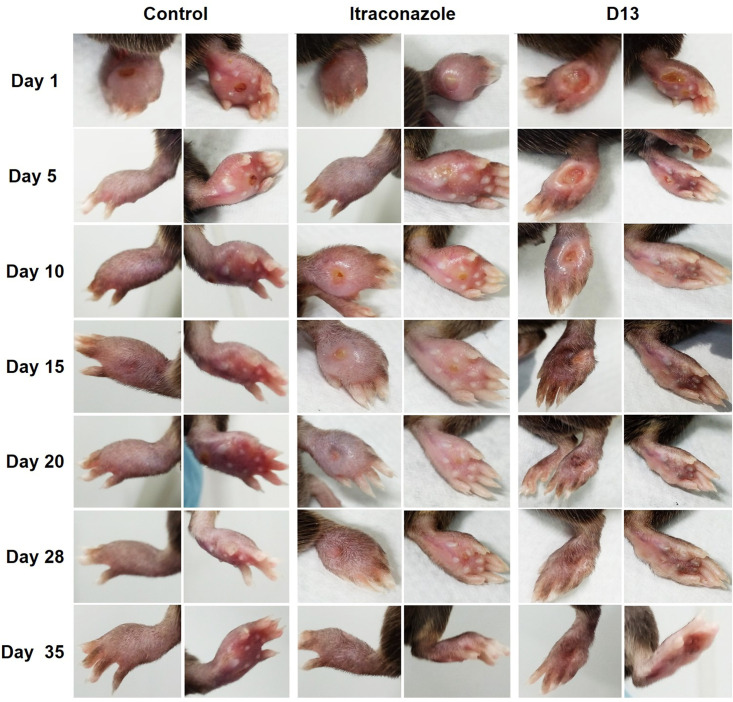

Our results showed that AH are potent inhibitors of Sporothrix species growth in vitro. Therefore, we investigated their efficiency in combatting murine subcutaneous sporotrichosis. The strategy used for the in vivo tests is represented in Fig. S2. In our first protocol (Fig. S2A), treatment was initiated after 25 days of infection, when the mice displayed paw swelling and cutaneous lesions (Fig. 3). Daily treatment with D13 intravenously (i.v.) promoted the recovery of the paw and hair growth reestablishment after 15 days. Treatment with ITC was less effective, and the lesions healed similarly to the control group. At the end of the experiment, the animals treated with D13 recovered completely from the infection. Mice were monitored for 3 weeks after the treatment was suspended. D13-treated mice had no signs of recurrence or development of new lesions. The control group and the mice treated with ITC showed chronic lesions but without changes in size and inflammation. However, about 20% of the control and ITC-treated mice died (data not shown).

FIG 3.

In vivo test 1. S. brasiliensis (5 × 106 cells/25 μl) was injected into the left hind paw of C57BL/6 mice. Treatments with D13 and itraconazole were performed intravenously (0.5 mg/kg/day/per tail). The images shown here correspond to days 1 to 35 of the treatment started after 25 days of infection. Mice treated with D13 showed the best recovery and did not show any lesions or signs of disease during the 3 weeks of observation after the end of treatment.

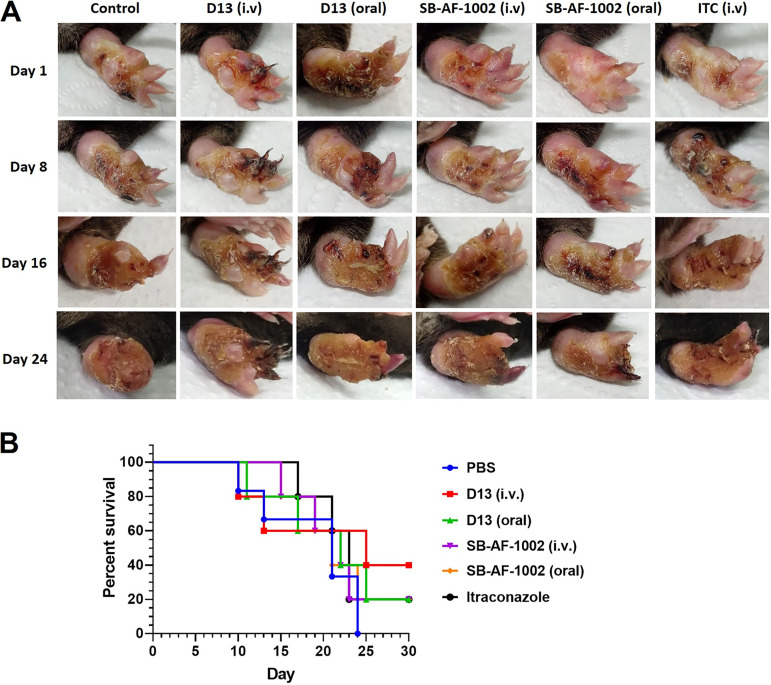

Since the strain showed a low-virulence profile, we decided to use a recent pick from the same S. brasiliensis strain (5110) with two passages in culture medium from frozen stock to confirm the protective activity of the AH derivatives. A higher severity of infection was observed, since the development of the lesion was visualized 15 days after the yeast’s inoculation, in contrast to the 25 days of the laboratory-adapted strain, with a faster and more severe outcome (Fig. 4). Daily treatment was started at day 15, as represented in the timeline scheme (Fig. S2B). For this experiment, we administered D13 and SB-AF-1002 derivatives orally and i.v. Body weight and paw swelling, usually associated with inflammation, were measured to monitor the progression of the lesion. In the absence of treatment (PBS), the paw was lost.

FIG 4.

In vivo test 2. (A) Mice infected with S. brasiliensis ATCC 5110 by subcutaneous injection in the hind paw were treated with AH derivatives and itraconazole. For D13 and SB-AF-1002, the treatment was performed intravenously (0.5 mg/kg/day/per tail) and by gavage (2 mg/kg/day). Itraconazole was administered intravenously as a control treatment. Mice were anesthetized with xylazine and ketamine before intravenous treatment. (B) Survival of mice subcutaneously infected with S. brasiliensis yeasts. Mice were treated daily after 15 days, when the lesions were developed, with the different drugs (orally or i.v.). ITC (i.v.) and PBS (i.v.) were used as controls.

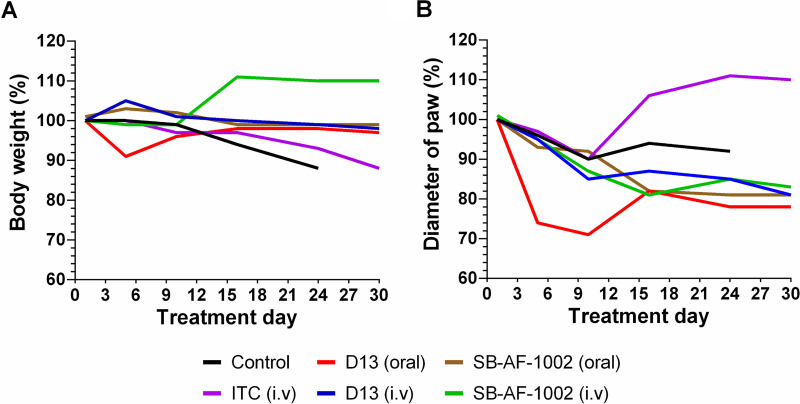

Different from the control and ITC-given groups, in which weight loss started at day 10 and 15, respectively, treatment with AH derivatives had no effect on mouse body weight (Fig. 5A). In fact, mice treated with SB-AF-1002 i.v. exhibited weight gain after the first 10 days of treatment (P = 001). Mice orally treated with D13 had decreased paw swelling (Fig. 5B), being significantly different from the group of mice treated with itraconazole (P < 0.001). In addition, treatment with SB-AF-1002 showed reduced paw inflammation compared to the ITC-treated group (P < 0.05). Mice belonging to the groups treated with D13 and SB-AF-1002 maintained body weight and displayed a decrease in inflammation compared to the control group and a better outcome compared with ITC treatment (Fig. 5A and B). After 39 days of infection, the last mouse from the control group died, and only the survivors of the other groups were monitored for 6 more days of treatment to complete a month of drug administration. Mice treated with D13 i.v. derivatives showed 40% survival, while in the other regimen only 20% were alive at the end of the experiment (Fig. 4B).

FIG 5.

Weight and paw diameter evaluation in mice infected with S. brasiliensis. Infection in C57BL/6 mice was performed subcutaneously (5 × 106 cells/25 μl). Lesions were visualized 15 days after infection, and the antifungal treatment was initiated by gavage or intravenously. Once the last mouse from the control group died, the survivors of the other groups were monitored for 6 more days of treatment. The weight of the mice (A) and the diameter of the inflamed paw (B) of each tested group were monitored.

DISCUSSION

The effectiveness of AH derivatives as a new class of compounds to combat fungal infections has been consistently tested in murine models against C. neoformans, C. albicans, P. murina, and A. fumigatus, with encouraging results (28–31). Here, we extended and confirmed the efficacy of the AH derivatives BHBM, D13, and SB-AF-1002 against the sporotrichosis agents S. schenckii and S. brasiliensis. Our results suggest that D13 and SB-AF-1002 exhibited higher activity in vitro and in vivo than itraconazole, the drug of choice for sporotrichosis (1). The concentration of the AH derivatives inhibiting these two species in vitro was in the range determined previously for other fungal pathogens, such as C. neoformans and H. capsulatum (28–31). However, the new derivatives D13 and SB-AF-1002 were more efficient than BHBM and considerably less toxic (29, 31).

Regardless of an additive or synergistic effect on drug combinations, the use of new compounds along with commercially available antifungals is an alternative strategy that helps to reduce the drug concentration and, consequently, their toxicity-related side effects (33). In our experiments, using the Bliss independence model, which assumes a stochastic process in which two drugs elicit their effects independently (34), an additive effect was observed when D13 and SB-AF-1002 were used in combination with ITC. These results are in agreement with the data published by Lazzarini and colleagues (29). They demonstrated a synergistic effect when D13 and ITC were combined against C. albicans clinical isolates resistant to fluconazole. Applying these findings to cats could be especially interesting, as they are frequently refractory to the current antifungal treatment against sporotrichosis (19).

Previous studies characterized that BHBM affects vesicular transport, cell budding, and cell cycle progression in fungal organisms (28). For instance, treatment of C. neoformans with BHBM promotes the accumulation of intracellular vesicles and increases NBD-Cer labeling, a fluorescent lipid that concentrates into the Golgi, endorsing the deficiency in the secretory pathway (28). S. schenckii and S. brasiliensis yeasts treated with BHBM displayed augmented NBD-Cer labeling, suggesting a similar mechanism of action. Treatment with D13 seems to be more effective than BHBM, culminating with yeast lysis. The reason by which D13 promotes the burst was not investigated but could involve an increase of intracellular pressure due to vesicle accumulation, an effect previously reported in C. neoformans (28). The presence of a gap in the chitin layer was visualized in a few yeasts, suggesting the discontinuity of the cell wall and reinforcing that cell integrity was damaged. TEM images of S. brasiliensis treated with AH derivatives also showed intracellular and cell surface damage and confirmed that yeast viability was compromised. Together, these data suggest that AH derivatives exert effects in S. brasiliensis similar to those observed in C. neoformans and C. albicans. Although the detachment of the cell outer layer appears to be the effect of exposure to AH and has not been observed in control cells, this has already been described in the literature (35).

The virulence of the strain and the administration route of the drug are pivotal factors that could directly interfere with the efficiency of the AH treatment (29, 36, 37). In our first in vivo experiment, we infected the mouse paw subcutaneously using a strain of S. brasiliensis with serial passages in the laboratory, a condition that reduces the virulence of the strain (38). Treatment was done intravenously, and the effects of itraconazole and D13 were compared. The full recovery of the paw was observed upon 15 days of D13 treatment, a result that was not observed for ITC. As mentioned previously, D13 has been successfully used in murine models of systemic infections; however, this is the first time that a subcutaneous infection has been efficiently treated with an AH derivative and suggests that D13 reaches the site of the infection even under an intense inflammatory response. Considering the broad spectrum of AH derivatives, our results indicate that these drugs can be exploited to combat subcutaneous mycosis. Recently, Lazzarini and colleagues (29) demonstrated that significant differences in the bioavailability of AH derivatives seem to be dependent on the administration route. The AH derivative SB-AF-1002 was tested orally and intravenously in a murine model of candidiasis (31). Remarkably, the plasma bioavailability of SB-AF-1002 after 8 h of administration was 10 times higher following oral administration than the intravenous regimen. However, the survival rate was only 20% in orally treated mice, whereas 100% of the mice treated intravenously survived (31). We then performed a second challenge using the same strain of S. brasiliensis with a few passages and two AH derivatives, D13 and SB-AF-1002, comparing intravenous and oral administration routes. The higher virulence of the strain was confirmed as the lesions emerged 15 days after inoculation. The disease was also more aggressive, causing paw destruction in 30 days for both untreated and ITC-treated mice. The control of weight loss and a slower progression of the lesion were observed when AH derivatives were administered, suggesting that the treatments were at least partially effective. There was no decrease in weight, but the paw diameter, with improvement in the lesion, was decreased. We may have used a suboptimal dose for treatment. Indeed, we chose the same drug concentration used in our first in vivo experiment, 0.5 mg/kg of body weight/day i.v. However, strains with higher virulence must require higher doses of D13, such as the 1.2 mg/kg/day used previously to control cryptococcosis (29).

Studies on new and low-cost drugs are necessary in a scenario of epizootic sporotrichosis, where investments for the development of new antifungal agents are scarce. It also becomes essential when azole derivatives are the principal drug of choice, since recent reports revealed the emergence of triazole-resistant isolates of human pathogens related to exposure to fungicides used in agroecosystems (39). In conclusion, our experiments indicate that AH treatment is a strategy to control subcutaneous sporotrichosis. Along with previous works, we confirmed that the acylhydrazones are a new class of antifungal drugs to be used against disseminated and subcutaneous mycosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, strains, and culture conditions.

RPMI 1640 (supplemented with l-glutamine, 0.2% [wt/vol] glucose and without sodium bicarbonate), bovine serum albumin (BSA), and itraconazole (≥98% thin layer chromatography) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) and brain heart infusion (BHI) were acquired from Oxoid, Brazil. All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade and were used without further purification. Solutions were prepared with deionized water. Pathogenic strains used in this study included Sporothrix brasiliensis ATCC 5110/MYA4823 and Sporothrix schenckii ATCC 1099-18/MYA4821. Both were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and kept on BHI agar. To obtain the inoculum for the in vivo test, S. brasiliensis was cultivated for 7 days at 25°C prior to use. Approximately 2 × 106 cells were used to inoculate 500-ml flasks containing 150 ml of BHI. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C in a rotary shaker with constant orbital agitation (150 rpm) for 4 days. Yeast cells were collected by centrifugation at 3,500 rpm for 10 min (4°C) and then washed three times in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (PBS). The yeast suspension was adjusted to 2 × 108 cells/ml, and cell viability was assessed by trypan blue staining. Samples with a minimum of 90% viability were employed for experimental assays (40).

Chemical synthesis. (i) BHBM.

To a solution of 2-methylbenzoic hydrazide (0.50 g, 3.3 mmol), 2-hydroxy-5-bromobenzaldehyde (0.73 g, 3.7 mmol) in methanol (13 ml) was added 9 drops of glacial acetic acid. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The addition of water (100 ml) to the reaction mixture resulted in the precipitation of the product, which was filtered, washed with water (200 ml) and dichloromethane (30 ml), and dried to give pure product as a white solid (1.05 g, 95% yield). 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (300 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 2.38 (s, 3H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 7.29 to 7.47 (m, 6H), 7.77 (s, 1H), 8.46 (s, 1H), 11.19 (s, 1H), 12.05 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 19.1, 19.4, 110.5, 118.5, 118.7, 121.4, 121.5, 125.5, 125.8, 126.9, 127.6, 129.3, 129.5, 130.0, 130.3, 130.5, 130.8, 133.3, 133.7, 134.2, 134.6, 135.7, 136.2, 141.5, 145.4, 155.7, 156.4, 165.2, 171.2; high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) (electrospray ionization) m/z calculated for C15H13BrN2O2H+, 333.0233; found, 333.0225 (Δ = 2.31 ppm). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) parameters were the following: Kinetex PFP, 2.6 μm, 100 by 2.1 mm, 100-Å column, acetonitrile and water, flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, t = 0 to 30 min, gradient of 30 to 95% acetonitrile, t = 6.04 min, purity of >95%.

(ii) D13.

To a solution of 4-bromobenzohydrazide (5.00 g, 23.4 mmol) and 2,5-diromosalicylaldehyde (7.14 g, 25.7 mmol) in methanol (40 ml), 5 drops of glacial acetic acid were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The addition of water to the reaction mixture resulted in the precipitation of the product, which was filtered, washed with water, and dried to give pure product as a yellow solid. The solid was then washed with a mixture of dichloromethane-acetone-hexanes (5:1:2) to give the pure product as a light yellow solid (87% yield); mp > 230°C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 7.76 (d, 2H, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.80 (s, 2H), 7.88 (d, 2H, J = 8.5 Hz), 8.51 (s, 1H), 12.58 (s, 1H), 12.64 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 110.4, 111.2, 120.9, 126.2, 129.8, 131.2, 131.7, 132.1, 135.6, 147.3, 153.6, 162. HPLC parameters were the following: Kinetex PFP, 2.6 μm, 100 by 2.1 mm, 100-Å column, acetonitrile and water, flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, t = 0 to 40 min, gradient of 30 to 95% acetonitrile, t = 11.07 min, purity of >99%.

(iii) SB-AF-1002.

2,4-Dibromobenzoic acid (5.00 g, 18.0 mmol) was converted to its methyl ester, followed by reaction with hydrazine monohydrate (18.0 g, 360.0 mmol), to give 2,4-dibromobenzohydrazide (3.40 g, 65% yield) by following the procedure previously published (30). To a solution of 2,4-dibromobenzohydrazide (3.00g, 10.3 mmol) and 5-bromosalicylaldehyde (2.1 g, 10.5 mmol) in methanol (20 ml), 5 drops of glacial acetic acid were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, which resulted in the precipitation of the product. The addition of water (50 ml) to the reaction mixture, followed by filtration and washing the precipitate with dichloromethane (100 ml) and acetone (30 ml), resulted in pure SB-AF-1002 as a beige solid (88% yield); mp > 220°C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 6.80 (d, 1H, 35%, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.90 (d, 1H, 65%, 8.7 Hz), 7.35 (m, 1H, 65%), 7.43 (m, 1H), 7.54 (d, 1H, 65%, J =8.2 Hz), 7.71 (dd, 1H, 35%, J = 8.2 Hz, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.73 (dd, 1H, 65%, J = 8.2 Hz, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.81 (d, 1H, 65%, J = 2.5 Hz), 8.26 (s, 1H, 35%), 8.46 (s, 1H, 65%), 10.22 (br s, 1H, 35%), 11.00 (br s, 1H, 65%), 12.18 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6), δ 110.51, 110.52, 118.5, 118.7, 119.8, 120.6, 121.3, 121.6, 122.7, 123.8, 129.0, 130.0, 130.2, 130.7, 130.8, 130.9, 133.5, 133.9, 134.1, 134.8, 136.1, 137.2, 141.5, 145.6, 155.7, 156.4, 162.5, 168.3; HRMS (time of flight) calculated for C14H9Br3N2O2H+, 474.8287; found, 474.8292 (Δ = −1.1 ppm). HPLC parameters were the following: Kinetex PFP, 2.6 μm, 100 by 2.1 mm, 100-Å column, acetonitrile and water, flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, t = 0 to 30 min, gradient of 40 to 95% acetonitrile, t = 7.8 min, purity of >99%.

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

Antifungal assays were carried out according to the method proposed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute in document M27-A3 (41), with adjustments in the cell suspension. Yeasts of Sporothrix spp. were cultivated in BHI broth at 37°C with orbital agitation (150 rpm) for 3 days. Cells were then washed in saline buffer and adjusted to a final concentration of 5 × 105 yeasts/ml in RPMI 1640. D13, SB-AF-1002, and BHBM were diluted in RPMI, and 100-μl volumes were added to 96-well plates at concentrations of 0.06, 0.12, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml. A volume of 100 μl of the yeast suspension was added to each well. Itraconazole and RPMI 1640 were used as a control. The culture optical density (OD) was measured spectrophotometrically (wavelength, 530 nm) on day 3 using a BioTeK ELx808 microplate reader from BioS X (Netherlands). The MIC50 and MIC99 values were defined as the lowest concentrations of drug that inhibited 50 and 99%, respectively, of control growth. All of the experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Drug interactions.

Checkerboard assay was used to determine the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICi) of AH derivatives in combination with itraconazole. Tests were performed on 96-well plates according to methods of previous studies (42, 43). Serial 2-fold dilutions of each drug were prepared. The first antifungal of the combination was serially diluted along the plate rows, while the second drug was diluted along its columns. The 96-well microplates were inoculated with 100 μl of 5 × 105 cells/ml and incubated at 35°C for 3 days, and the optical density was measured at 530 nm using a microplate reader (Biotek ELx808). The FICi was defined as (MIC combined/MIC drug A alone) + (MIC combined/MIC drug B alone). The drug interaction was considered synergistic when the FICi was <0.5, indifferent when the FICi was 0.5 to 4, and antagonistic when the FICi was >4 (42). The Bliss synergism scores were also calculated using the SynergyFinder tool (44). A score of less than −10 was considered an antagonistic interaction, from −10 to 10 was an additive interaction, and more than 10 was a synergistic interaction between two drugs.

Golgi staining.

To investigate the distribution and morphological changes in the Golgi apparatus, yeast cells were stained with NBD C6-ceramide (N-[7-(4-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole)]-6-aminocaproyl-d-erythro-sphingosine) (28). Yeasts were treated with PBS (control) or the AH derivatives BHBM (4 μg/ml) and D13 (4 μg/ml) for 4 h at room temperature. The cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and subsequently incubated with NBD C6-ceramide (20 mM) for 16 h at 4°C. Samples were then incubated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) (1%) at 4°C for 1 h to remove unbound NBD C6-ceramide. The cell wall was stained upon incubation with Uvitex 2B (Polysciences, Inc., PA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The yeasts were then washed with PBS, mounted over glass, and visualized using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Analysis of the antifungal effect of AH derivatives by transmission electron microscopy.

Yeasts of S. brasiliensis (ATCC 5110) were treated with the MIC50 of AH derivatives in RPMI 1640 medium for 48 h at 35°C. Cells were then collected by centrifugation and washed three times in PBS buffer. Subsequently, yeasts were fixed overnight with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% formaldehyde, and 10 mM calcium chloride in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, at 4°C. Postfixation was carried out in 1% osmium tetroxide in sodium cacodylate buffer containing 0.08% potassium ferrocyanide at room temperature for 2 h. This step was followed by dehydration in increasing acetone concentrations, and the yeasts were finally embedded in Spurr’s resin (Ted Pella Inc.). Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were obtained using an ultramicrotome (LEICA EM UC6). Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, placed onto 300-mesh copper grids, and observed in a transmission electron microscope (JEOL 1200 EX) operated to 80 kV and equipped with a megaview G2 camera (14 bits).

Mouse studies.

To investigate the efficacy of the AH derivatives in vivo, we used a murine model for subcutaneous sporotrichosis (40). Groups of five C57BL/6 females, 7 to 8 weeks old (16 to 18 g), were obtained from the Núcleo de Criação de Animais de Laboratório of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). Each mouse was previously anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and then received a subcutaneous injection of 25 μl (5 × 106 yeasts) into the left hind footpad. Daily treatment with AH derivatives intravenously (i.v.) (0.5 mg/kg/day/tail) or orally (2 mg/kg/day by gavage) were initiated after lesion development. Itraconazole (ITC) or PBS, used as a negative control, was administered i.v. Two independent experiments were carried out with the treatment and monitoring of lesions. For the second experimental protocol, the body weight, the diameter of the paw, and the survival pattern were obtained. For measuring the diameter of the paw, a digital Vernier caliper was used.

Ethics statement.

The mouse study was reviewed and approved by the Commission on Ethics in the Use of Animals (CEUA, UFRJ), protocol number 01200.001568/2013-87.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with ordinary one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s multiple-comparison test using GraphPad Prism 7 software. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Brazilian agency Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grants 311179/2017-7 and 408711/2017-7 to L.N.), FAPERJ (E-26/202.809/2018 to L.N. and E-26/202.737/2019 to S.A.P.), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Finance Code 001), Programa de Incentivo a Jovens Pesquisadores/INI/Fiocruz (PJP/INI grant INI-003-FIO-19-2-10 to I.D.F.G.), and the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI116420 to M.D.P.). J.J.A.B. was supported by the Organization of American States-Coimbra Group of Brazilian Universities (OAS-CGBU, 2015). L.H. was supported by CAPES (2019).

We thank Rachel Rachid from the National Center for Structural Biology and Bioimaging of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro for her help with TEM images.

M.D.P. is a cofounder and Chief Scientific Officer (CSO) of MicroRid Technologies, Inc. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

M.D.P. and L.N. contributed to the conception and design of the study. K.H. performed the synthesis and characterization of the AH derivatives. J.J.A.B. and P.D.M.T. performed the in vitro antifungal tests. P.D.M.T. and A.G. performed the fluorescence analysis. J.J.A.B. and L.H. performed the mouse studies and statistical analysis. J.J.A.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and approved the submitted version.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonifaz A, Tirado Sánchez A. 2017. Cutaneous disseminated and extracutaneous sporotrichosis: current status of a complex disease. J Fungi 3:6. 10.3390/jof3010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sizar O, Talati R. 2020. Sporotrichosis. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30335288/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brilhante RSN, Rodrigues AM, Sidrim JJC, Rocha MFG, Pereira SA, Gremiaõ IDF, Schubach TMP, de Camargo ZP. 2016. In vitro susceptibility of antifungal drugs against Sporothrix brasiliensis recovered from cats with sporotrichosis in Brazil. Med Mycol 54:275–279. 10.1093/mmy/myv039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, do Valle AC, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC. 2014. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e3094. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poester VR, Mattei AS, Madrid IM, Pereira JTB, Klafke GB, Sanchotene KO, Brandolt TM, Xavier MO. 2018. Sporotrichosis in southern Brazil, towards an epidemic? Zoonoses Public Health 65:815–821. 10.1111/zph.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DZP, Schwartz IS. 2019. Emerging fungal infections: new patients, new patterns, and new pathogens. J Fungi 5:67. 10.3390/jof5030067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues AM, Della Terra PP, Gremião ID, Pereira SA, Orofino-Costa R, de Camargo ZP. 2020. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia 185:813–842. 10.1007/s11046-020-00425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gremião IDF, Oliveira MME, Monteiro de Miranda LH, Saraiva Freitas DF, Pereira SA. 2020. Geographic expansion of Sporotrichosis, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 26:621–624. 10.3201/eid2603.190803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva GM, Howes JCF, Leal CAS, Mesquita EP, Pedrosa CM, Oliveira AAF, Silva LB, Mota RA. 2018. Surto de esporotricose felina na região metropolitana do Recife. Pesq Vet Bras 38:1767–1771. 10.1590/1678-5150-pvb-5027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. 2016. Sporothrix species causing outbreaks in animals and humans driven by animal-animal transmission. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005638. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etchecopaz AN, Lanza N, Toscanini MA, Devoto TB, Pola SJ, Daneri GL, Iovannitti CA, Cuestas ML. 2020. Sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis in Argentina: case report, molecular identification and in vitro susceptibility pattern to antifungal drugs. J Mycol Med 30:100908. 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.100908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etchecopaz A, Scarpa M, Mas J, Cuestas ML. 2020. Sporothrix brasiliensis: a growing hazard in the northern area of Buenos Aires Province? Rev Argent Microbiol S0325-7541:30022–30025. 10.1016/j.ram.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kano R, Okubo M, Siew HH, Kamata H, Hasegawa A. 2015. Molecular typing of Sporothrix schenckii isolates from cats in Malaysia. Mycoses 58:220–224. 10.1111/myc.12302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siew HH. 2017. The current status of feline sporotrichosis in Malaysia. Med Mycol J 58:E107–E113. 10.3314/mmj.17.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopes-Bezerra LM, Mora-Montes HM, Zhang Y, Nino-Vega G, Rodrigues AM, de Camargo ZP, de Hoog S. 2018. Sporotrichosis between 1898 and 2017: the evolution of knowledge on a changeable disease and on emerging etiological agents. Med Mycol 56:126–143. 10.1093/mmy/myx103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orofino-Costa R, Rodrigues AM, de Macedo PM, Bernardes-Engemann AR. 2017. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol 92:606–620. 10.1590/abd1806-4841.2017279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almeida-Paes R, Brito-Santos F, Figueiredo-Carvalho MHG, Machado ACS, Oliveira MME, Pereira SA, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. 2017. Minimal inhibitory concentration distributions and epidemiological cutoff values of five antifungal agents against Sporothrix brasiliensis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 112:376–381. 10.1590/0074-02760160527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borba-Santos LP, Rodrigues AM, Gagini TB, Fernandes GF, Castro R, de Camargo ZP, Nucci M, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Ishida K, Rozental S. 2015. Susceptibility of Sporothrix brasiliensis isolates to amphotericin B, azoles, and terbinafine. Med Mycol 53:178–188. 10.1093/mmy/myu056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gremião IDF, Menezes RC, Schubach TMP, Figueiredo ABF, Cavalcanti MCH, Pereira SA. 2015. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med Mycol 53:15–21. 10.1093/mmy/myu061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almeida-Paes R, Oliveira MME, Freitas DFS, Do Valle ACF, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. 2017. Refractory sporotrichosis due to Sporothrix brasiliensis in humans appears to be unrelated to in vivo resistance. Med Mycol 55:507–517. 10.1093/mmy/myw103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Rocha RFDB, Schubach TMP, Pereira SA, Dos Reis ÉG, Carvalho BW, Gremião IDF. 2018. Refractory feline sporotrichosis treated with itraconazole combined with potassium iodide. J Small Anim Pract 59:720–721. 10.1111/jsap.12852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reis ÉG, Schubach TMP, Pereira SA, Silva JN, Carvalho BW, Quintana MSB, Gremião IDF. 2016. Association of itraconazole and potassium iodide in the treatment of feline sporotrichosis: a prospective study. Med Mycol 54:684–690. 10.1093/mmy/myw027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batista-Duharte A, Lastre M, Romeu B, Portuondo DL, Téllez-Martínez D, Manente FA, Pérez O, Carlos IZ. 2016. Antifungal and immunomodulatory activity of a novel cochleate for amphotericin B delivery against Sporothrix schenckii. Int Immunopharmacol 40:277–287. 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishida K, de Castro RA, Borba dos Santos LP, Quintella LP, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Rozental S. 2015. Amphotericin B, alone or followed by itraconazole therapy, is effective in the control of experimental disseminated sporotrichosis by Sporothrix brasiliensis. Med Mycol 53:34–41. 10.1093/mmy/myu050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamill RJ. 2013. Amphotericin B formulations: a comparative review of efficacy and toxicity. Drugs 73:919–934. 10.1007/s40265-013-0069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira SA, Passos SRL, Silva JN, Gremião IDF, Figueiredo FB, Teixeira JL, Monteiro PCF, Schubach TMP. 2010. Response to azolic antifungal agents for treating feline sporotrichosis. Vet Rec 166:290–294. 10.1136/vr.166.10.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gremião IDF, Martins da Silva da Rocha E, Montenegro H, Carneiro AJB, Xavier MO, de Farias MR, Monti F, Mansho W, de Macedo Assunção Pereira RH, Pereira SA, Lopes-Bezerra LM. 29 September 2020. Guideline for the management of feline sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix brasiliensis and literature revision. Braz J Microbiol 10.1007/s42770-020-00365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mor V, Rella A, Farnou AM, Singh A, Munshi M, Bryan A, Naseem S, Konopka JB, Ojima I, Bullesbach E, Ashbaugh A, Linke MJ, Cushion M, Collins M, Ananthula HK, Sallans L, Desai PB, Wiederhold NP, Fothergill AW, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson T, Wong LH, Sinha S, Giaever G, Nislow C, Flaherty P, Pan X, Cesar GV, de Melo Tavares P, Frases S, Miranda K, Rodrigues ML, Luberto C, Nimrichter L, Del Poeta M. 2015. Identification of a new class of antifungals targeting the synthesis of fungal sphingolipids. mBio 6:e006476. 10.1128/mBio.00647-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazzarini C, Haranahalli K, Rieger R, Ananthula HK, Desai PB, Ashbaugh A, Linke MJ, Cushion MT, Ruzsicska B, Haley J, Ojima I, Del Poeta M. 2018. Acylhydrazones as antifungal agents targeting the synthesis of fungal sphingolipids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:1–14. 10.1128/AAC.00156-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haranahalli K, Lazzarini C, Sun Y, Zambito J, Pathiranage S, McCarthy JB, Mallamo J, Del Poeta M, Ojima I. 2019. SAR studies on aromatic acylhydrazone-based inhibitors of fungal sphingolipid synthesis as next-generation antifungal agents. J Med Chem 62:8249–8273. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazzarini C, Haranahalli K, McCarthy JB, Mallamo J, Ojima I, Del Poeta M. 2020. Preclinical evaluation of acylhydrazone SB-AF-1002 as a novel broad-spectrum antifungal agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00946-20. 10.1128/AAC.00946-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar P, Narasimhan B. 2013. Hydrazides/hydrazones as antimicrobial and anticancer agents in the new millennium. Mini Rev Med Chem 13:971–987. 10.2174/1389557511313070003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan H, Ma Q, Cui H, Liu G, Zhao X, Li W, Piao G. 2017. How can synergism of traditional medicines benefit from network pharmacology? Molecules 22:1135. 10.3390/molecules22071135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Q, Yin X, Languino LR, Altieri DC. 2018. Evaluation of drug combination effect using a bliss independence dose-response surface model. Stat Biopharm Res 10:112–122. 10.1080/19466315.2018.1437071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopes Bezerra LM, Walker LA, Niño Vega G, Mora Montes HM, Neves GWP, Villalobos Duno H, Barreto L, Garcia K, Franco B, Martínez-Álvarez JA, Munro CA, Gow NAR. 2018. Cell walls of the dimorphic fungal pathogens Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis exhibit bilaminate structures and sloughing of extensive and intact layers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12:e0006169. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gad SC, Cassidy CD, Aubert N, Spainhour B, Robbe H. 2006. Nonclinical vehicle use in studies by multiple routes in multiple species. Int J Toxicol 25:499–521. 10.1080/10915810600961531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lan H, Wu L, Sun R, Yang K, Liu Y, Wu J, Geng L, Huang C, Wang S. 2018. Investigation of Aspergillus flavus in animal virulence. Toxicon 145:40–47. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima RF, Schäffer GV, de Borba CM. 2003. Variants of Sporothrix schenckii with attenuated virulence for mice. Microbes Infect 5:933–938. 10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribas AD, Spolti P, Del Ponte EM, Donato KZ, Schrekker H, Fuentefria AM. 2016. Is the emergence of fungal resistance to medical triazoles related to their use in the agroecosystems? A mini review. Braz J Microbiol 47:793–799. 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Della Terra PP, Rodrigues AM, Fernandes GF, Nishikaku AS, Burger E, de Camargo ZP. 2017. Exploring virulence and immunogenicity in the emerging pathogen Sporothrix brasiliensis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0005903. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard, 4th ed. CLSI document M27-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m27/. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao YJ, Da Liu W, Shen YN, Li DM, Zhu KJ, Zhang H. 2019. The efflux pump inhibitor tetrandrine exhibits synergism with fluconazole or voriconazole against Candida parapsilosis. Mol Biol Rep 46:5867–5874. 10.1007/s11033-019-05020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brilhante RS, Pereira VS, Oliveira JS, Rodrigues AM, de Camargo ZP, Pereira-Neto WA, Nascimento NR, Castelo-Branco DS, Cordeiro RA, Sidrim JJ, Rocha MF. 2019. Terpinen-4-ol inhibits the growth of Sporothrix schenckii complex and exhibits synergism with antifungal agents. Future Microbiol 14:1221–1233. 10.2217/fmb-2019-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ianevski A, He L, Aittokallio T, Tang J. 2017. SynergyFinder: a web application for analyzing drug combination dose-response matrix data. Bioinformatics 33:2413–2415. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.