Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) is a critical component of the innate immune response, in part due to its transactivation of beta interferon (IFN-β) expression. Similar to that observed in all acute virus infections examined to date, IRF-3 suppresses lytic viral replication during acute gammaherpesvirus infection.

KEYWORDS: B cell responses, IRF-3, chronic infection, gammaherpesvirus, interferon

ABSTRACT

Gammaherpesviruses are ubiquitous pathogens that establish lifelong infections and are associated with several malignancies, including B cell lymphomas. Uniquely, these viruses manipulate B cell differentiation to establish long-term latency in memory B cells. This study focuses on the interaction between gammaherpesviruses and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor with multiple direct target genes, including beta interferon (IFN-β), a type I IFN. IRF-3 attenuates acute replication of a plethora of viruses, including gammaherpesvirus. Furthermore, IRF-3-driven IFN-β expression is antagonized by the conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinase during lytic virus replication in vitro. In this study, we have uncovered an unexpected proviral role of IRF-3 during chronic gammaherpesvirus infection. In contrast to the antiviral activity of IRF-3 during acute infection, IRF-3 facilitated establishment of latent gammaherpesvirus infection in B cells, particularly, germinal center and activated B cells, the cell types critical for both natural infection and viral lymphomagenesis. This proviral role of IRF-3 was further modified by the route of infection and viral dose. Furthermore, using a combination of viral and host genetics, we show that IRF-3 deficiency does not rescue attenuated chronic infection of a protein kinase null gammaherpesvirus mutant, highlighting the multifunctional nature of the conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinases in vivo. In summary, this study unveils an unexpected proviral nature of the classical innate immune factor, IRF-3, during chronic virus infection.

IMPORTANCE Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) is a critical component of the innate immune response, in part due to its transactivation of beta interferon (IFN-β) expression. Similar to that observed in all acute virus infections examined to date, IRF-3 suppresses lytic viral replication during acute gammaherpesvirus infection. Because gammaherpesviruses establish lifelong infection, this study aimed to define the antiviral activity of IRF-3 during chronic infection. Surprisingly, we found that, in contrast to acute infection, IRF-3 supported the establishment of gammaherpesvirus latency in splenic B cells, revealing an unexpected proviral nature of this classical innate immune host factor.

INTRODUCTION

Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) is a constitutively and ubiquitously expressed transcription factor that is classically perceived as a critical component of host innate immunity (1). Specifically, IRF-3, along with several other IRF family members, plays an important role in driving expression of type I interferons (IFNs) in response to viral infection (2, 3). Not surprisingly, IRF-3 antagonizes replication of diverse viruses, including West Nile virus (WNV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV), and murine norovirus (MNV) (2, 4, 5). Multiple IRF-3 target genes have been identified in addition to IFN-β (6–8); however, the role of these target genes in IRF-3 biology is still poorly understood. The role of IRF-3 during chronic virus infections also remains unclear.

Gammaherpesviruses are highly prevalent pathogens that establish lifelong infections and are associated with diverse malignancies, including lymphomas (9). Similar to that for other viruses, type I IFN signaling attenuates lytic replication of human (Epstein Barr virus [EBV], Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus [KSHV]), and rodent (murine gammaherpesvirus 68 [MHV68], also referred to as murid herpesvirus-4 and γHV68) gammaherpesviruses (10–13). Furthermore, type I IFN inhibits persistent MHV68 replication and attenuates MHV68 reactivation from latency during chronic infection (14), indicating that the antiviral role of type I IFN is maintained throughout all stages of gammaherpesvirus infection.

Coevolution of gammaherpesviruses with their hosts has generated multiple viral mechanisms to attenuate type I IFN induction, including targeting IRF-3 expression and activation. EBV-encoded immediate early lytic protein BRLF1 decreases mRNA levels of IRF-3 (15). KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) competes with IRF-3 for binding to the IFN-β promoter (16), and overexpression of KSHV viral IRF-2 outside the context of infection accelerates caspase 3-mediated cleavage of IRF-3 (17). Finally, conserved protein kinases encoded by EBV, KSHV, and MHV68 directly interact with IRF-3 to attenuate IRF-3-mediated transcription of IFN-β (18, 19). However, antagonism of IRF-3 by the viral protein kinase is insufficient to ablate IRF-3 antiviral functions, as IRF-3 attenuates lytic replication of MHV68 in vitro and in vivo (12, 20).

The extent to which IRF-3 suppresses chronic gammaherpesvirus infection has not been defined due to the exquisite species specificity of human gammaherpesviruses that limits in vivo studies. Interestingly, a rare, autosomal dominant loss-of-function mutation in IRF-3 led to herpes simplex encephalitis in an adolescent patient (21); however, the status of other herpesvirus infections was not examined. To define the extent to which antiviral activity of IRF-3 manifests during chronic gammaherpesvirus infection of a natural intact host, we utilized MHV68, a rodent gammaherpesvirus that is genetically and biologically similar to human gammaherpesviruses, including its ability to induce B cell lymphomas (22–25). Unexpectedly and in contrast to the antiviral role of IRF-3 during acute MHV68 replication, the establishment of latent MHV68 reservoir was significantly attenuated in IRF-3−/− mice following low dose intranasal inoculation. In contrast to the antagonism between IRF-3 and the conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinases observed during lytic replication in vitro, IRF-3 deficiency did not rescue attenuated chronic infection of a protein kinase null gammaherpesvirus mutant, further demonstrating the multifunctional nature of the conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinase. In summary, this study reveals a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde role of IRF-3, wherein the innate immune factor critical for suppression of acute MHV68 replication also promotes the establishment of a latent viral reservoir during chronic infection.

RESULTS

IRF-3 promotes the establishment of latent gammaherpesvirus infection.

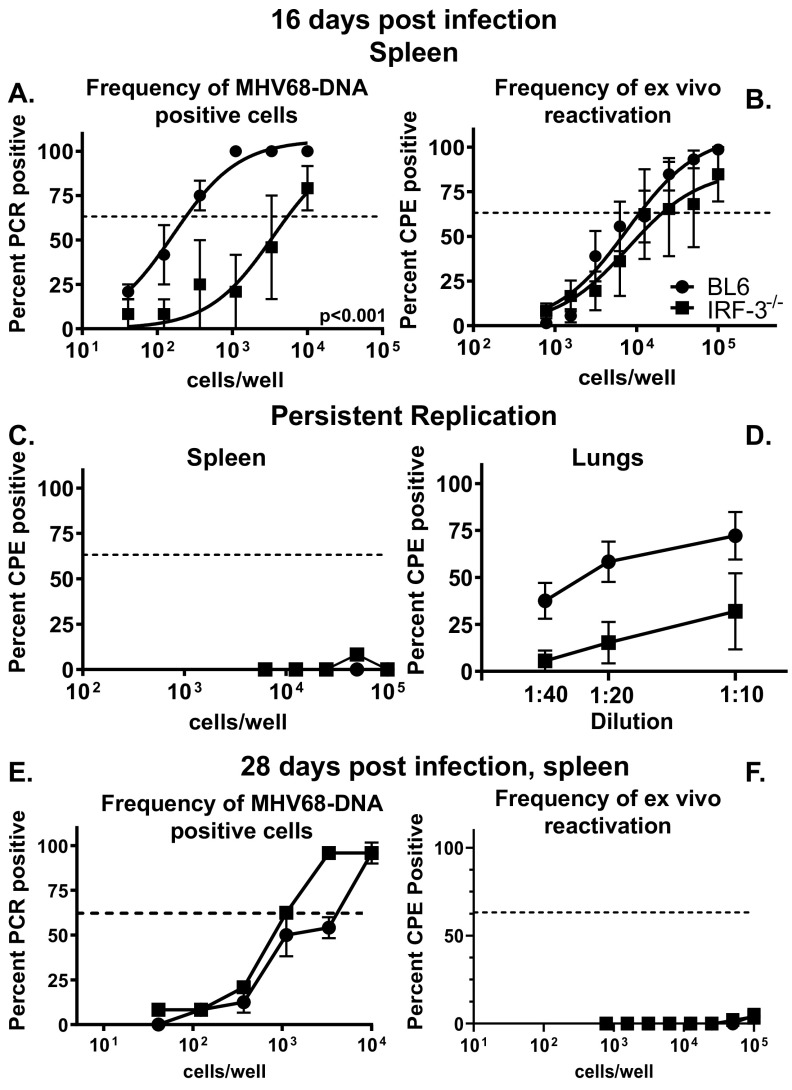

In an immunocompetent host, lytic MHV68 replication is controlled by 10 to 12 days postinfection, concurrent with the rise in a latent viral reservoir which peaks at 16 days postinfection. We showed that IRF-3 attenuates acute MHV68 infection, with increased MHV68 titers observed in IRF-3−/− lungs (20). To define the extent to which IRF-3 suppresses the establishment of a peak latent splenic reservoir, parameters of MHV68 infection were compared in C57BL/6J (BL6) and IRF-3−/− mice at 16 days post-intranasal infection. Unexpectedly, the frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive cells was significantly reduced in IRF-3−/− splenocytes (25-fold) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the frequencies of ex vivo MHV68 reactivation were similar in BL6 and IRF-3−/− splenocytes (Fig. 1B), indicating a greater efficiency of viral reactivation in the absence of IRF-3. Unlike IFNAR1−/− mice that show increased levels of persistent MHV68 replication in multiple organs (26), there was no increase in the persistent MHV68 replication in the spleens of IRF-3−/− mice (Fig. 1C), and levels of persistently replicating MHV68 were actually decreased in IRF-3−/− lungs (Fig. 1D). Thus, IRF-3 supported the establishment of peak MHV68 latency while attenuating the efficiency of viral reactivation.

FIG 1.

IRF-3 promotes the establishment of latent gammaherpesvirus infection. C57BL/6J (BL6) and IRF-3−/− mice were intranasally infected with 1,000 PFU of MHV68. At 16 or 28 days postinfection, limiting dilution assays were used to define frequencies of MHV68 DNA-positive cells (A and E) and MHV68 reactivation (B and F) in splenocytes pooled from 3 to 5 mice/experimental group. In the limiting dilution assays presented in the manuscript, the dotted line is drawn at 62.5% and the x coordinate of intersection of this line with the sigmoid graph represents and inverse of the frequency of positive events. Levels of preformed lytic virus in splenocytes (C) and lungs (D) at 16 days postinfection. Data were pooled from 2 to 4 independent experiments.

Following the peak of latency observed at 16 days postinfection, the MHV68 splenic latent reservoir contracts and stabilizes, with a subsequent decrease in viral reactivation as infection transitions to the long-term stage. Having observed the proviral role of IRF-3 during the peak of MHV68 latency, the IRF-3 effect on long-term infection was examined next. The frequencies of MHV68 DNA-positive splenocytes were similar in BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice at 28 days postinfection (Fig. 1E) along with the minimal viral reactivation detected in both groups (Fig. 1F), indicating that IRF-3 expression did not alter MHV68 splenic latency parameters during long-term infection.

IRF-3 expression does not affect gammaherpesvirus-driven B cell differentiation.

The establishment of chronic gammaherpesvirus infection is intimately tied to B cell differentiation (reviewed in reference 27). While infection of developing B cells in the bone marrow contributes to the maintenance of a long-term MHV68 reservoir (28, 29), latent infection of differentiating B cells in secondary lymphoid organs supports peak MHV68 latency (30). Specifically, MHV68 and EBV infect naive B cells and subsequently drive activation of both infected and bystander B cells. Upon entry of latently infected B cells into the germinal centers, B cells undergo multiple rounds of proliferation, resulting in an exponential increase in the cellular latent viral reservoir (30–33). Further differentiation of infected germinal center B cells either supports lifelong latency in memory B cells or induces viral reactivation from plasma cells (34). Importantly, germinal center B cells host the majority of the latent virus reservoir at the peak of latent infection (31, 35).

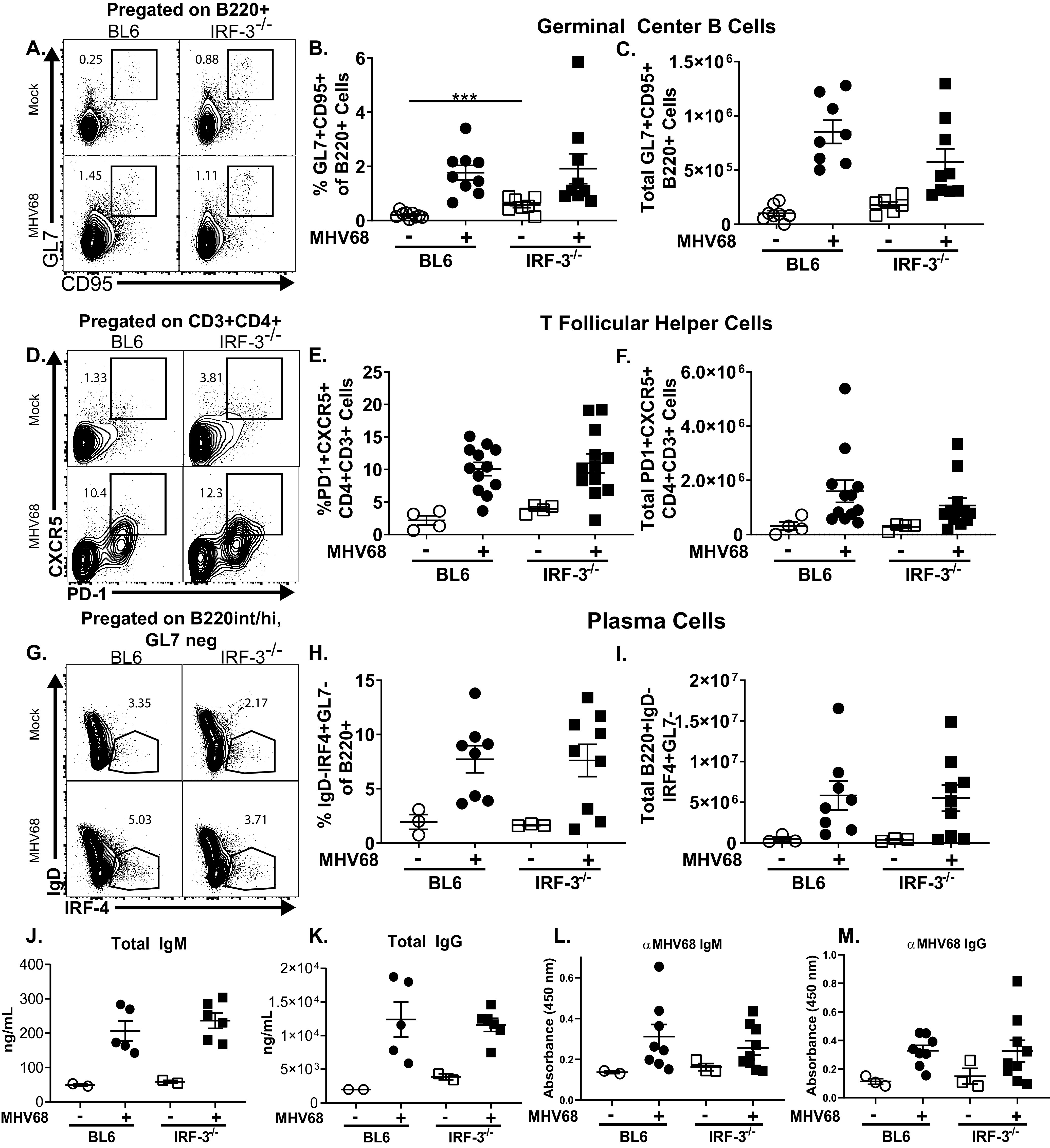

Having observed a reduced frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive splenocytes in the absence of IRF-3 at 16 days postinfection, the germinal center response was examined next. Surprisingly, MHV68 infection induced similar frequencies and absolute numbers of germinal center B cells in BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice (Fig. 2A to C). Of note, the baseline frequency of germinal center B cells was elevated in IRF-3−/− mice compared to that in BL6 mice (Fig. 2B). CD4 T follicular helper cells are critical for MHV68-driven germinal center response and the establishment of peak viral latency (30, 36). Consistent with similar levels of germinal center B cells in MHV68-infected BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice, the frequency and absolute number of CD4 T follicular helper cells in MHV68-infected animals were also not affected by IRF-3 genotype (Fig. 2D to F). Differentiation of infected germinal center B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells triggers a switch from latency to lytic replication, which ultimately contributes to the expansion of the viral reservoir (34, 37–39). Consistent with IRF-3-independent expansion of the germinal center response, the frequencies and total numbers of class-switched plasma cells were also similar in BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice (Fig. 2G to I). A functional outcome of MHV68-driven B cell differentiation is the production of antibodies, including antibodies directed against MHV68. Consistent with the similar germinal center responses and abundance of class-switched plasma cells in BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice, serum levels of total (Fig. 2J and K) and MHV68-specific (Fig. 2L and M) IgM and IgG were equivalently induced in BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice at 16 days postinfection. Thus, IRF-3 expression had no effect on the cellular or humoral parameters of B cell differentiation at the peak of MHV68 latency.

FIG 2.

IRF-3 expression does not affect gammaherpesvirus-driven B cell differentiation. Mice of indicated genotypes were mock infected or infected as for Fig. 1. At 16 days postinfection, splenocytes were analyzed via flow cytometry. Germinal center B cells were identified as GL7+ CD95+ cells pregated on B220+ cells (representative shown in A) and expressed as frequency (B) and total cell number (C). T follicular helper cells were identified as PD1+ CXCR5+ cells pregated on CD3+ CD4+ cells (representative shown in D) and expressed as frequency (E) and total cell number (F). Plasma cells were identified as IgD-IRF4+ cells pregated on B220int/+ GL7− cells (representative shown in G) and further identified as GL7−, expressed as frequency (H) and total cell number (I). (J to M) Sera collected from mice at 16 days postinfection or after mock treatment were subjected to ELISA to determine levels of indicated circulating antibodies. Each symbol represents result for an individual mouse, and data from 2 to 4 independent experiments were pooled. ***, P < 0.001.

IRF-3 facilitates MHV68 infection of germinal center/activated B cells.

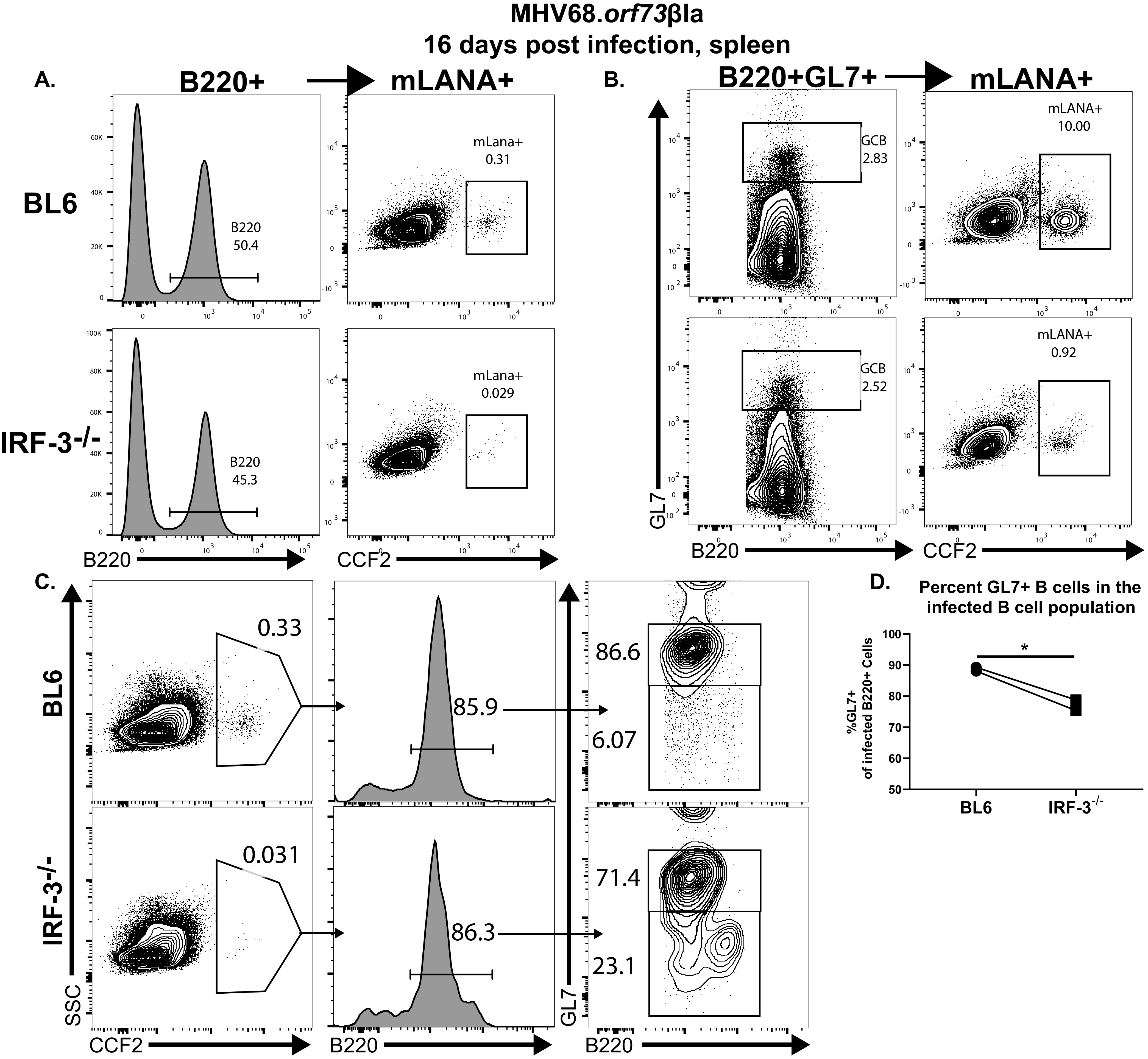

To resolve the discrepancy between the attenuated MHV68 latent splenic reservoir and equal abundance of BL6 and IRF-3−/− germinal center B cells that host a majority of latent MHV68 in wild-type mice (31, 35), the efficiency of germinal center B cell infection was examined next. BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were infected with an MHV68 mutant (MHV68.ORF73βla) (40) that expresses modified β-lactamase fused to mLANA (encoded by orf73), a viral latent protein that is critical for the maintenance of the gammaherpesvirus episome (41, 42). Cell-permeable β-lactamase substrate (CCF2) was used in flow cytometry studies to detect MHV68-infected splenocytes positive for β-lactamase activity, offering a robust approach to quantify latently infected splenocytes with minimal levels of viral gene expression. Consistent with limiting dilution PCR analyses (Fig. 1A), the proportion of β-lactamase-positive splenic B cells was significantly decreased in IRF-3−/− mice (Fig. 3A). Similarly, despite comparable abundances, fewer GL7+ IRF-3−/− B cells were positive for β-lactamase activity (Fig. 3B). Thus, IRF-3, while having no effect on the overall germinal center response, promoted MHV68 infection of germinal center/activated B cells.

FIG 3.

IRF-3 facilitates MHV68 infection of germinal center/activated B cells. BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were intranasally infected with 1,000 PFU of MHV68.ORF73βla. At 16 days postinfection, splenocytes were pooled from 3 to 5 mice/genotype, and β-lactamase activity in B220+ (A) and B220+ GL7+ (B) splenocytes was assessed by flow cytometry using fluorescence of the cleaved CCF2 β-lactamase substrate. Images representative of two independent experiments are shown. (C and D) At 16 days postinfection, β-lactamase (cleaved CCF2)-positive splenocytes pooled from 3 to 5 spleens/group were further gated based on B220 expression and subsequently separated into GL7-positive and -negative populations. Data in panel D were pooled from two independent experiments.

Having observed an increased efficiency of MHV68 reactivation from IRF-3−/− splenocytes (Fig. 1) and considering a reported shift of MHV68 tropism toward myeloid cells in the absence of type I IFN signaling, at least during acute infection (43), the distributions of latent MHV68 were compared in BL6 and IRF-3−/− spleens. Similar to that observed for B220+ B cells (Fig. 3A), the frequency of β-lactamase-positive splenocytes was reduced in IRF-3−/− mice (Fig. 3C). However, the majority of β-lactamase-positive infected splenocytes was represented by B220+ B cells regardless of the IRF-3 genotype, indicating that IRF-3 deficiency does not shift MHV68 tropism toward non-B cells in the spleen. Interestingly, significantly fewer β-lactamase-positive IRF-3−/− B cells also expressed GL7 than infected BL6 B cells (Fig. 3C and D), further supporting the conclusion that IRF-3 promotes MHV68 infection of germinal center/activated B cells.

IRF-3 supports expression of select interferon-stimulated genes but not the generation of MHV68-specific CD8 T cells during the peak of MHV68 latent infection.

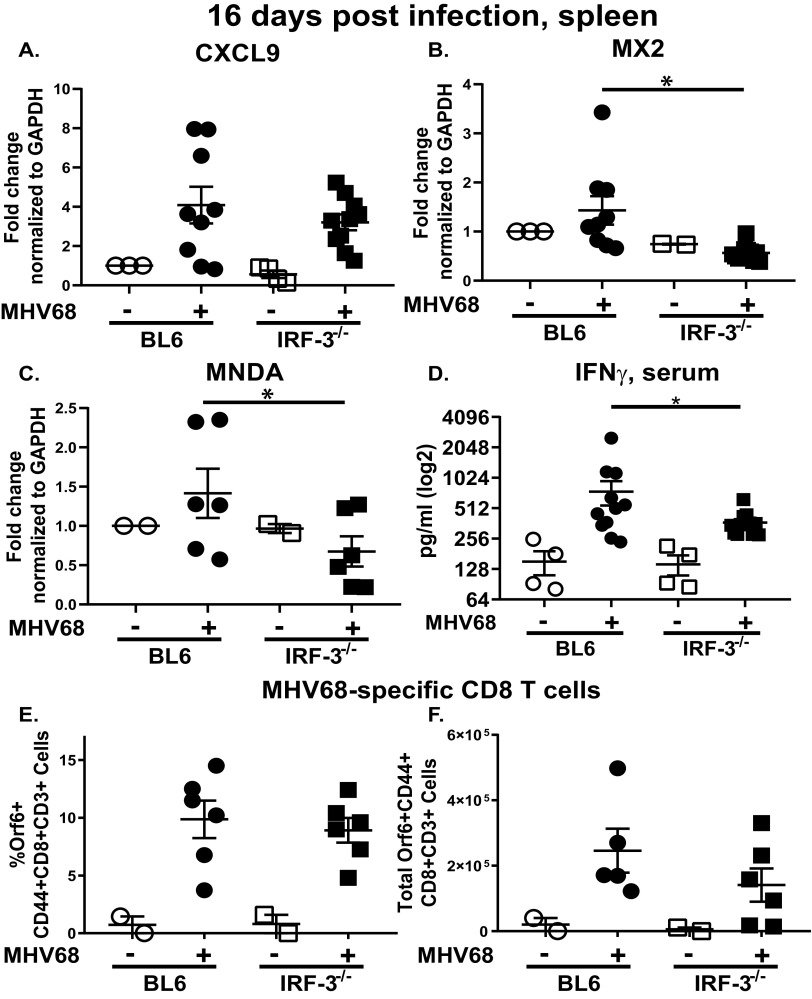

Having observed increased efficiency of the MHV68 reactivation in IRF-3−/− splenocytes (Fig. 1B), we considered two nonexclusive scenarios that might be responsible for this observation. First, because type I IFN signaling attenuates MHV68 reactivation during chronic infection (14) and given the role of IRF-3 in driving type I IFN expression, IFN signaling was assessed in BL6 and IRF-3−/− spleens at 16 days postinfection. The type I IFN family consists of more than a dozen different cytokines that all engage a single type I IFN receptor complex, with subsequent signaling culminating in expression of hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). Given the multitude of type I IFN cytokines, expression of select ISGs was measured instead, as these reflect the extent of IFN signaling and serve as the effectors of antiviral activity. While mRNA levels of CXCL9, an ISG that is primarily driven by IFN-γ (44), were similar in BL6 and IRF-3−/− spleens (Fig. 4A), expression of MX2 and MNDA, ISGs that can be induced by type I or type II IFN and attenuate lytic MHV68 replication in vitro (45), was IRF-3 dependent at 16 days postinfection (Fig. 4B and C).

FIG 4.

IRF-3 supports expression of select interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) but not the generation of MHV68-specific CD8 T cells during the peak of MHV68 latent infection. Mice were infected as for Fig. 1. At 16 days postinfection, total RNA was isolated from individual spleens and subjected to qRT-PCR using CXCL9 (A), MX2 (B), and MNDA (C) primers, with relative expression further normalized against corresponding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels and relative to expression observed in mock-infected BL6 mice. (D) Sera from mock- or MHV68-infected mice were subjected to IFN-γ ELISA. Frequency (E) and absolute number (F) of MHV68-positive CD8 T cells (defined as CD3+ CD8+ CD44+ orf6 tetramer+) were quantified in the spleens harvested at 16 days postinfection. Each symbol represents an individual mouse; data were pooled from 2 to 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05.

Splenic ISG expression during chronic MHV68 infection is likely to be driven by a combination of type I and type II IFN signaling, especially given the significant overlap of ISGs that are induced by type I or type II IFNs (45). To determine the extent to which type II IFN expression was affected by IRF-3, levels of IFN-γ, a single member of the type II IFN family, were assessed. A modest, 2-fold decrease in serum IFN-γ levels was observed in IRF-3−/− MHV68-infected mice (Fig. 4D). Thus, concurrent with the attenuation of MHV68 reactivation, IRF-3 expression was necessary for optimal expression of select ISGs in the spleen and optimal induction of serum IFN-γ at 16 days post-MHV68 infection.

In a second scenario, attenuated IFN signaling could result in suboptimal T cell responses, as CD8 T cell-intrinsic type I IFN signaling supports survival of proliferating lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-specific CD8 T cells (46). Having observed decreased expression of select ISGs in IRF-3−/− MHV68-infected spleens, MHV68-specific CD8 T cells were assessed next. Abundance of MHV68-specific, tetramer-positive CD8 T cells was similar in BL6 and IRF-3−/− spleens (Fig. 4E and F), indicating that IRF-3 expression was dispensable for the generation of MHV68-specific CD8 T cells.

IRF-3 expression is dispensable for the establishment of MHV68 splenic latency following intraperitoneal infection.

Viral and host requirements for the establishment of MHV68 latency are frequently dependent on the inoculation route. While gammaherpesvirus entry via the mucosal surface represents the natural route of infection, bypassing mucosal entry via direct inoculation into the body cavities or circulation has offered insights into the biology of latency-defining factors that guide the course of natural infection. Having observed a significant attenuation of MHV68 latency following intranasal infection of IRF-3−/− mice, viral and host parameters were next examined following intraperitoneal inoculation.

Similar to phenotypes of other host and MHV68 mutants (47, 48), intraperitoneal inoculation of BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice produced similar frequencies of MHV68 DNA-positive splenocytes and ex vivo reactivation at 16 days postinfection (Fig. 5A and B). Furthermore, MHV68 infection induced an increase in the frequency, but not absolute number, of germinal center B cells in IRF-3−/− mice compared to that in BL6 mice (Fig. 5C and D). Consistent with the role of CD4 T follicular helper cells in MHV68-driven germinal center response, both the frequency and absolute number of these cells were also elevated in IRF-3−/− mice following intraperitoneal inoculation (Fig. 5E and F). Thus, while IRF-3 supported the establishment of MHV68 latency following the mucosal route of infection, direct introduction of the virus into the peritoneal cavity abolished the requirement for IRF-3 in the establishment of MHV68 latency.

FIG 5.

IRF-3 expression is dispensable for the establishment of MHV68 splenic latency following intraperitoneal infection. Mice of indicated genotypes were intraperitoneally infected with 1,000 PFU of wild-type MHV68 and analyzed at 16 days postinfection. Splenocytes were pooled from mice within each group and subjected to limiting dilution analyses to define the frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive cells (A) and ex vivo reactivation (B). Germinal center B cells (C and D) and T follicular helper cells (E and F) were defined as for Fig. 2 and measured in splenocytes from individual mice (each symbol represents individual animal). Data were pooled from 2 individual experiments. *, P < 0.05.

IRF-3 deficiency does not rescue attenuated acute replication of the gammaherpesvirus protein kinase null mutant.

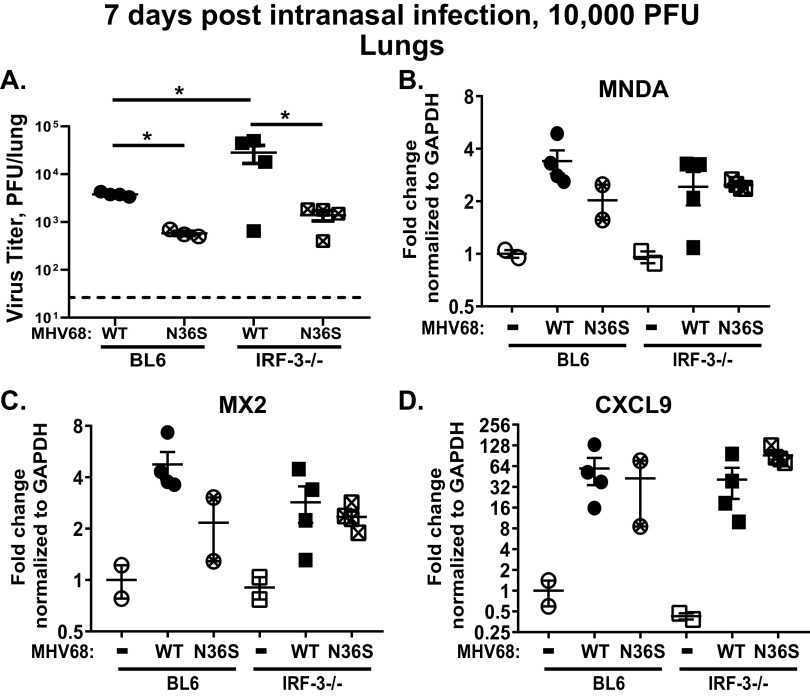

IRF-3-driven IFN-β expression is antagonized by conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinases to promote lytic viral replication in vitro (18, 19). To define the extent to which this antagonism occurs during lytic replication in vivo (and, subsequently, during establishment of the viral latent reservoir), BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were infected with the N36S MHV68 mutant that lacks viral protein kinase expression or a control wild-type virus (49). An infectious dose of 10,000 PFU was used for both viruses, as the N36S mutant fails to colonize the spleen at 16 days postinfection when using a lower 1,000-PFU dose (50), making direct comparisons of host and viral phenotypes problematic under low-infection-dose conditions. Similar to that observed following a lower inoculum dose of 1,000 PFU (20), inoculation of IRF-3−/− mice with 10,000 PFU of wild-type MHV68 generated a significant 5-fold increase in the lung viral titers at 7 days postinfection (Fig. 6A). As expected, acute lung titers of the N36S MHV68 mutant were 7-fold lower than those of wild-type MHV68 in BL6 lungs. This difference between wild-type (WT) MHV68 and N36S mutant lung titers was further increased to 12-fold in IRF-3−/− mice. In contrast, only a 2.7-fold difference in acute N36S titers was observed between BL6 and IRF-3−/− lungs, and this difference was not statistically significant. Furthermore, lung expression of MNDA, MX2, and CXCL9 was not affected by the IRF-3 deficiency in wild-type MHV68-infected or N36S-infected groups (Fig. 6B to D). Thus, IRF-3 deficiency did not rescue acute replication of the N36S mutant and did not have a significant effect on the ISG expression under the tested experimental conditions.

FIG 6.

IRF-3 deficiency does not rescue attenuated acute replication of the gammaherpesvirus protein kinase null mutant. BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were intranasally infected with 10,000 PFU of N36S MHV68 mutant that lacks expression of viral protein kinase or a corresponding control MHV68. (A) Viral titers in the lungs were determined at 7 days postinfection. Dotted line represents the limit of infectious virus detection. (B to D) Levels of mRNA of indicated ISGs were measured in total RNA isolated from lungs using qRT-PCR. Relative expression was normalized to corresponding GAPDH levels and to the relative expression observed in mock-infected BL6 mice. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. *, P < 0.05.

IRF-3 deficiency does not rescue attenuated establishment of splenic latency of the gammaherpesvirus protein kinase null mutant.

Expression of MHV68 protein kinase (orf36) also promotes the establishment of peak latent infection and MHV68-driven germinal center response (50). The extent to which the antagonism between viral protein kinase and IRF-3 affects chronic MHV68 infection has not been defined. To probe for potential interaction between MHV68 orf36 and IRF-3 during chronic infection, BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were infected as described above, and parameters of peak MHV68 latency in the spleen were assessed at 16 days postinfection. Increasing the infection dose to 10,000 PFU rescued the frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive splenocytes in IRF-3−/− mice infected with wild-type MHV68 (Fig. 7A) and rescued infection by MHV68.ORF73βla virus of IRF-3−/− total and germinal center/activated B cells (data not shown). In contrast to that observed with the 1,000-PFU infectious dose, the efficiency of reactivation of wild-type MHV68 was no longer affected by IRF-3 expression following infection with 10,000 PFU (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, similar levels of MHV68-specific splenic CD8 T cells were generated in BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice (data not shown).

FIG 7.

IRF-3 deficiency does not rescue attenuated latency of the gammaherpesvirus protein kinase null mutant. BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were intranasally infected with 10,000 PFU of N36S MHV68 mutant that lacks expression of viral protein kinase or a corresponding control MHV68. At 16 days postinfection, frequencies of MHV68 DNA-positive cells (A) and viral reactivation (B) were assessed in splenocytes pooled from 3 to 4 mice/group as for Fig. 1A and B. Data were pooled from 4 to 5 independent experiments. (C to E) Levels of indicated mRNAs were determined by qRT-PCR in spleens and were further normalized to corresponding GAPDH mRNA levels, with fold changes defined on the basis of the relative expression in spleens of mock-infected BL6 mice. Each symbol represents an individual spleen. *, P < 0.05.

As expected, infection of BL6 mice with the protein kinase-deficient N36S mutant resulted in a decreased frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive splenocytes compared to that in BL6 mice infected with wild-type MHV68 (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, IRF-3−/− mice infected with the N36S viral mutant demonstrated a similar frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive splenocytes compared to that in the N36S-infected BL6 mice (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the frequency of ex vivo reactivation from splenocytes was similarly attenuated in N36S-infected mice, regardless of the IRF-3 genotype (Fig. 7B). Thus, while increasing the inoculum dose rescued the latency parameters of wild-type MHV68 in IRF-3−/− mice, IRF-3 deficiency failed to rescue the attenuated latency of an MHV68 protein kinase null mutant, highlighting the multifunctional nature of the conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinases.

Antagonism between gammaherpesvirus protein kinases and IRF-3 is expressed as increased expression of ISGs in the absence of viral protein kinase in vitro, including during MHV68 infection (12). Having observed no rescue of establishment of N36S latency in IRF-3−/− mice, ISG expression in the spleens was assessed next. Unlike that observed following 1,000-PFU infection, a higher inoculation dose of wild-type MHV68 abolished differential expression of MNDA in BL6 and IRF-3−/− spleens (Fig. 7C and 4C). Similarly, the protein kinase status of the infecting virus did not affect MNDA mRNA levels. Unlike that observed for MNDA, MX2 mRNA levels were decreased in wild-type MHV68-infected IRF-3−/− spleens (Fig. 7D), consistent with that observed following a lower-dose inoculation (Fig. 4B). Similarly, induction of CXCL9 mRNA, while higher under the 10,000-PFU inoculum conditions, remained IRF-3 independent in wild-type MHV68-infected spleens (Fig. 7E). Interestingly, infection with the N36S mutant produced opposite CXCL9 expression phenotypes in BL6 and IRF-3−/− spleens. While mRNA levels of CXCL9 were significantly elevated in spleens of N36S-infected mice compared to that in wild-type MHV68-infected BL6 spleens, mRNA levels of CXCL9 remained at the corresponding baseline level in IRF-3−/− mice infected with the N36S mutant, suggesting that the exaggerated induction of CXCL9 expression in the spleens of N36S-infected mice was IRF-3 driven.

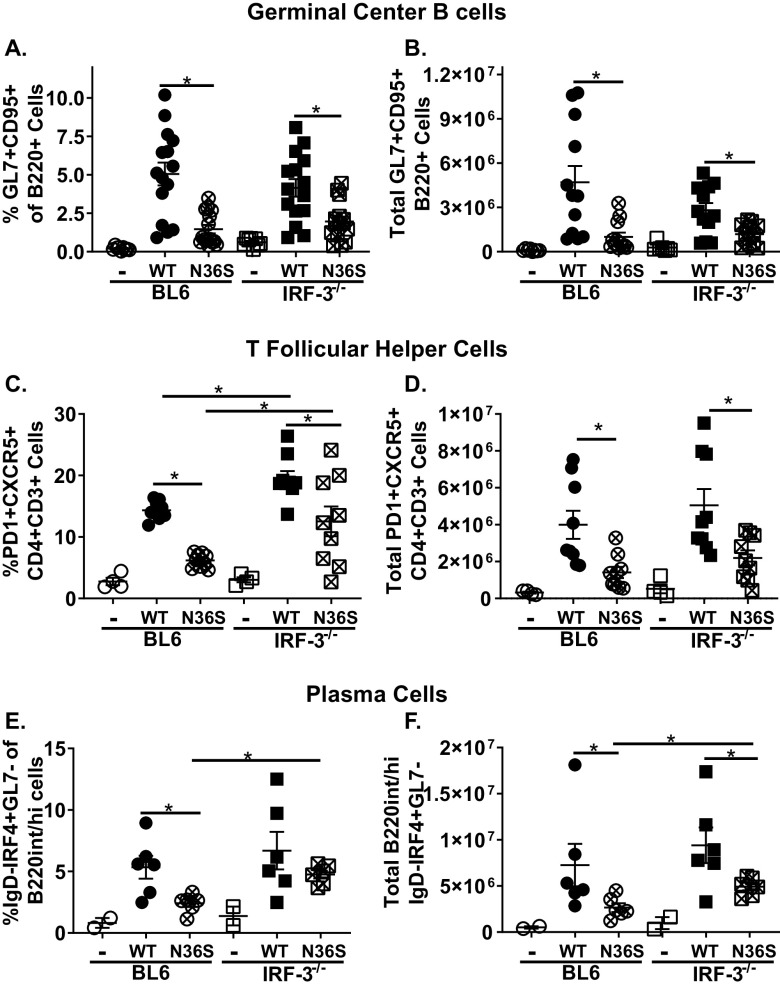

IRF-3 deficiency partially rescues induction of CD4 T follicular helper cells and class-switched plasma cells but not germinal center B cells in N36S-infected mice.

We showed that expression and enzymatic activity of MHV68 protein kinase is required for optimal induction of MHV68-driven germinal center B cells and CD4 T follicular helper cells, regardless of the dose of inoculation (50). In contrast, IRF-3 is required for neither the humoral responses to nonreplicating immunogen (51) nor germinal center response induced by wild-type MHV68 (Fig. 2). Having observed no IRF-3-dependent changes in the latency parameters of the N36S mutant (Fig. 7A and B), MHV68-driven B cell differentiation was examined next. The abundance of germinal center B cells was decreased in BL6 mice infected with the N36S mutant, and this decrease was not further modified by the lack of IRF-3 (Fig. 8A and B). The proportion, but not absolute number, of CD4 T follicular helper cells was increased in wild-type MHV68-infected IRF-3−/− mice compared to that in BL6 mice (Fig. 8C and D), reminiscent of the phenotype seen following intraperitoneal infection (Fig. 5E) but without a concomitant increase in germinal center B cells. Interestingly, IRF-3 deficiency partially rescued the attenuation of the frequency of CD4 T follicular helper population in N36S mutant-infected mice, although CD4 T follicular helper cells remained decreased in N36S-infected mice compared to that in wild-type MHV68-infected mice (Fig. 8C and D). Finally, IRF-3 deficiency also increased both the frequency and absolute number of class-switched plasma cells in N36S-infected mice (Fig. 8E and F). Thus, IRF-3 deficiency partially rescued the induction of CD4 T follicular helper and class-switched plasma cells but not germinal center B cells following infection with the viral protein kinase null mutant; however, these effects were not sufficient to rescue attenuated viral latency.

FIG 8.

IRF-3 deficiency partially rescues induction of CD4 T follicular helper cells and class-switched plasma cells but not germinal center B cells in N36S-infected mice. BL6 and IRF-3−/− mice were infected with 10,000 PFU of wild-type (WT) or N36S MHV68, as for Fig. 6, with splenocytes analyzed at 16 days postinfection using the gating strategy shown in Fig. 2. Germinal center B cells were identified as GL7+ CD95+ cells pregated on B220+ cells and expressed as frequency (A) and total cell number (B). T follicular helper cells were identified as PD1+ CXCR5+ cells pregated on CD3+ CD4+ cells and expressed as frequency (C) and total cell number (D). Plasma cells were identified as IgD-IRF4+ GL7− cells pregated on B220int/+ GL7− cells expressed as frequency (E) and total cell number (F). Each symbol represents the result for an individual spleen, and data from 2 to 4 independent experiments were pooled. *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals an unexpected proviral role of IRF-3 during chronic gammaherpesvirus infection. IRF-3 is a classical innate immune transcription factor with well-established antiviral phenotypes in the context of lytic replication of diverse viruses, including MHV68. Thus, it is particularly surprising that the established antiviral role of IRF-3 during acute MHV68 infection is warped into one that supports the MHV68 latent reservoir once the infection becomes chronic. Furthermore, using classic host-pathogen genetic approaches, our study demonstrates that the antagonism between the gammaherpesvirus protein kinase and host IRF-3 previously demonstrated during lytic virus replication in vitro is no longer evident during the acute replication or the establishment of latent gammaherpesvirus infection, at least under the conditions tested, highlighting the multifunctional nature of the gammaherpesvirus protein kinases during infection of an intact host.

IRF-3 and herpesvirus infection.

The importance of IRF-3 in restricting herpesvirus replication in vivo is illustrated by an autosomal dominant loss-of-function mutation in IRF-3 that resulted in increased susceptibility to herpes simplex encephalitis in a 15-year-old patient, although the penetrance of the mutation phenotype was not complete in the patient’s family (21). Importantly, it is also not clear whether the herpes simplex encephalitis observed in the index case was associated with a primary or recurrent infection, and the status of other prevalent herpesvirus infections was not examined in the published report. Observations in the patient phenocopied those in animal studies that used the mouse model of IRF-3 deficiency. In these studies, IRF-3 expression was not required for the control of HSV-1 replication in the cornea but was instead critical to limit HSV-1 spread through the central nervous system (CNS), with increased mortality, HSV-1 titers, and a significant drop in type I IFN expression within the CNS of IRF-3−/− mice (4, 52, 53). In contrast to HSV, the role of IRF-3 in controlling chronic beta- and gammaherpesvirus infection of the intact host remains poorly defined. Our study is the first to define such a role and demonstrate a switch from the antiviral to proviral function of IRF-3 as MHV68 infection progresses from the acute to chronic stage, highlighting the fact that the interaction of herpesviruses with the innate immune system may be more nuanced than previously anticipated.

This virus-innate immune factor interaction may be further modified by the gammaherpesvirus life cycle and experimental conditions. While conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinases are well-defined antagonists of IRF-3-driven IFN-β expression during lytic replication in vitro, we did not observe any rescue of attenuated acute replication of the N36S MHV68 mutant in IRF-3−/− lungs or during the establishment of latent N36S infection in IRF-3−/− spleen. Consistent with multiple reports using wild-type or mutant MHV68 viruses or host mutations, we also observed that IRF-3-dependent changes in acute replication of wild-type MHV68 did not translate to identical IRF-3-dependent changes in the peak latent viral reservoir in the spleen, providing further evidence of distinct host and viral mechanisms that regulate acute versus latent infection.

How does IRF-3 promote the establishment of MHV68 latency?

IRF-3 is a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor that directly targets many cellular genes. In a majority of published reports, the role of IRF-3 in driving expression of type I IFN is overemphasized compared to IRF-3’s ability to regulate other cellular genes, with the physiological significance of the latter regulation remaining mostly undefined. Our study also demonstrates decreased induction of select ISGs in latently MHV68-infected IRF-3−/− spleens; however, circulating levels of IFN-γ, a type II IFN, were also decreased 2-fold in IRF-3−/− mice, suggesting multiple reasons for the observed attenuation in IFN signaling. Importantly, the unexpected proviral role of IRF-3 observed in this study is not likely to be solely mediated by the IRF-3-driven induction of type I IFN due to the difference in the chronic MHV68 infection phenotypes in IFNAR1−/− and IRF-3−/− mice. Specifically, IFNAR1−/− mice fail to control persistent MHV68 replication in multiple organs for at least 21 days postinfection, and there is no attenuation of the viral reservoir at any time postinfection (14, 26). The increased efficiency of MHV68 reactivation observed in IRF-3−/− splenocytes (Fig. 1) may be the only shared phenotype between the two mouse models.

However, it is intriguing to speculate that the autocrine type I IFN expression and subsequent signaling may contribute to the proviral effects of IRF-3 observed in this study. Neuronal specific STAT1 deficiency resulted in attenuated HSV reactivation from latency, in spite of greatly exaggerated acute replication in the CNS, with this attenuation ascribed to the prosurvival functions of STAT1 in neurons (54). Furthermore, elegant genetic approaches employed by the Stevenson group revealed that the MHV68 genome within the infected splenic B cells demonstrates the highest exposure to the type I IFN signaling compared to that of other infected cell types (43). An important future direction is to define the cell-type-specific roles of type I and type II IFN signaling during chronic MHV68 infection, using approaches that overcome the dysregulated pathogenesis of gammaherpesvirus infection observed in mice with global deficiency of these signaling networks. The intriguing role of non-IFN IRF-3 target genes in regulating gammaherpesvirus latency should also be probed in the future approaches, including IRF-3 target genes that may be regulated in a cell-type-specific manner.

Our study has demonstrated that the proviral role of IRF-3 during the establishment of MHV68 latency is both route-of-infection and dose dependent, a phenotype shared with other virus and host mutants. For example, M2 is an MHV68-encoded latent protein that promotes manipulation of B cell differentiation during chronic MHV68 infection. A low dose of infection renders the M2 null MHV68 mutant incapable of establishing a peak latent reservoir in the spleen, whereas an increase in the inoculation dose or switching the route of inoculation from intranasal to intraperitoneal mostly rescues the peak viral latent reservoir but not attenuated reactivation (47, 55, 56). Similar phenotypes were observed upon wild-type MHV68 infection of mice with B-cell-specific STAT3 deficiency (48). Finally, we have shown that enzymatic activity of MHV68 orf36 is required to support the establishment of the peak latent reservoir in the spleen following intranasal but not intraperitoneal infection (57).

Given that the natural gammaherpesvirus infection proceeds via mucosal surfaces, it is not at all surprising that the virus has evolved multiple mechanisms to ensure successful establishment of chronic infection following mucosal inoculation, particularly under conditions of a low infectious dose. Such mechanisms remain poorly defined but are likely to involve critical differences in innate immune responses at mucosal versus body cavity sites, including differences in antigen presentation and subsequent priming of the adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, distinct cell types are exposed to MHV68 following intranasal versus intraperitoneal infection. As demonstrated by the Stevenson group, intranasal infection leads to the “hand-off” of MHV68 from epithelial cells to macrophages to B-2 splenic B cells (58). In contrast, epithelial cells are not likely to be a major infected cell type following direct inoculation into the peritoneal cavity, with cavity-resident macrophages and B-1 B cells representing more likely immediate targets of infection (59–61).

IRF-3 expression was also not required for the germinal center response and B cell differentiation in mice infected with 1,000 PFU of wild-type MHV68 (Fig. 2), similar to the reported lack of IRF-3-dependent phenotypes following immunization (51). In contrast, Plasmodium infection induced an exaggerated IRF-3−/− germinal center response compared to that in wild-type mice (62). Of note, during malarial infection, T-cell-extrinsic IRF-3 deficiency was sufficient to skew the differentiation of wild-type CD4 T cells toward the T follicular helper phenotype (62). Consistent with the observation in the Plasmodium infection, we also observed increased abundance of T follicular helper CD4 T cells in IRF-3−/− mice following intraperitoneal 1,000 PFU infection or a higher-dose intranasal infection. Interestingly, intranasal infection with 10,000 PFU of wild-type or N36S mutant MHV68, while increasing CD4 follicular helper T cells in IRF-3−/− infected mice, did not result in a concomitant increase in germinal center B cells, a phenotype that is unexpected given the well-defined positive feedback loop between follicular helper T cells and germinal center B cells observed in multiple experimental systems, including with MHV68 infection (30). Similarly, attenuated levels of germinal center B cells observed following infection with the N36S mutant remained decreased in the absence of IRF-3, despite an impressive expansion of the proportion of CD4 T follicular helper cells in the N36S-infected IRF-3−/− mice (Fig. 8C), highlighting the role of the conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinases in manipulating B cell differentiation (50, 63).

In summary, the results of the present study emphasize an important but underappreciated concept that the function of traditional innate immune factors of the host is by no means limited to the acute phase of viral infection but instead continues into the chronic phase of infection, with potentially unanticipated novel phenotypes to be defined in other chronic virus infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6J (BL6) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). IRF-3−/− deficient mice (on the C57BL/6J genetic background) were obtained from Michael Diamond (53). Mice were bred and housed in a specific-pathogen-free barrier facility in accordance with institutional and federal guidelines. All experimental manipulations of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Viruses and infections.

Virus stocks were prepared and the titers determined on NIH 3T12 cells. Wild-type MHV68 (WUMS) was used in studies with a single infectious entity, unless otherwise specified. Studies of the N36S MHV68 mutant were controlled by the parental virus retaining a single LoxP site (referred to as wild-type in the figures and text) (18). The virus expressing β-lactamase (MHV68.ORF73βla) (40) was a kind gift of Scott Tibbetts. Infections were performed by intranasal inoculation of 3 to 5 mice per group at 6 to 7 weeks of age under light anesthesia. Mice were inoculated with 103 or 104 PFU of virus or sterile carrier (mock) in an inoculum volume of 15 μl per mouse. For intraperitoneal infections, 103 PFU of wild-type virus were delivered in 300 μl/mouse. Virus was diluted in sterile serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Corning, Tewksbury, MA).

Viral assays.

The frequency of MHV68 DNA-positive cells and frequency of ex vivo reactivation of MHV68 were determined as previously described (64). Briefly, to determine the frequency of cells harboring viral DNA, splenocytes were pooled from all mice within each experimental group (3 to 5 mice/group), and 6 serial 3-fold dilutions were subjected to a nested PCR (12 replicates/dilution) using primers against the viral genome. To determine the frequency of cells reactivating virus ex vivo, splenocytes were pooled from all mice within each experimental group (3 to 5 mice/group), and 8 to 12 serial 2-fold dilutions of splenocyte suspensions from each group were plated onto monolayers of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) at 24 replicates per dilution. In order to control for preformed virus, 2-fold serial dilutions of mechanically disrupted splenocytes were plated as described above. Cytopathic clearing of MEFs was scored at 21 days postplating. The use of primary MEFs to amplify virus lowers the sensitivity of lytic MHV68 detection to a single PFU. Assays of persistent virus replication in the lungs were performed as previously described (65). To define acute MHV68 titers, lungs were harvested in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and disrupted by bead beating using 1-mm zirconia/silica beads (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Homogenates were cleared by brief centrifugation and the titers of supernatants were determined by plaque assay using NIH 3T12 fibroblasts.

Flow cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were prepared in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 2% fetal bovine serum, 0.05% sodium azide) at 1 × 107 nucleated cells/ml. A total of 1.5 × 106 cells were prestained with Fc block (24G2) and then incubated with an optimal dilution of antibody on ice. When necessary, cells were then fixed and permeabilized with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) for the detection of intracellular antigens. The following antibodies and reagents were used in this study and purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA): B220-phycoerythrin (PE)-Cy7, CD95-PE, GL7-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD3-allophycocyanin (APC) A700, CD4-Pacific Blue (PB), CXCR5 (triple amplification used: CXCR5-rat anti-mouse IgG, biotin-goat anti-rat IgG, and streptavidin-APC), PD-1-PE, IRF-4-PE, IgD-PB, CD3 (17A2), CD8a (53-7.3), and CD44 (IM7). In some cases, after extracellular staining, splenocytes from mice infected with the β-lactamase reporter virus were incubated with cell-permeable CCF-2 substrate for 1 h. Allophycocyanin-conjugated major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I tetramer specific for MHV68 epitope Db/ORF6487–495 (AGPHNDMEI) was obtained from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (Emory University, Atlanta, GA). Data acquisition was performed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Sane Jose, CA), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

qRT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was harvested, DNase treated, reverse transcribed, and analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using previously described primers (66, 67). cDNA was assessed in triplicates along with corresponding negative RT reactions by real-time PCR using a CFX Connect System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

ELISA.

IFN-γ concentrations were determined using an IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) MAX Deluxe set (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using Nunc MaxiSorp flat-bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Serum was diluted 1:2 in assay diluent prior to analysis. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzymatic activity was stopped by the addition of 1 N HCl, and absorbance was read at 450 nm on a model 1420 Victor 3V multilabel plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Total and MHV68-specific serum IgM and IgG were assessed as previously described (50).

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t tests (Prism, GraphPad Software, Inc.).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Cui laboratory for their technical assistance in this study.

This study was supported by F31 CA243364-01 (K.E.J.), 20PRE35200108 (P.A.S.), 134165-PF-19-176-01-MPC (C.N.J.), F30 CA247000 (C.A.A), and CA203923 (V.L.T.).

K.E.J., P.A.S., and V.L.T. led the conceptual design of the study, and K.E.J. and V.L.T. wrote the manuscript. K.E.J. and P.A.S. designed, performed, and analyzed experiments. C.N.J. and C.A.A. performed and analyzed experiments.

We declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Au WC, Moore PA, Lowther W, Juang YT, Pitha PM. 1995. Identification of a member of the interferon regulatory factor family that binds to the interferon-stimulated response element and activates expression of interferon-induced genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:11657–11661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, Asagiri M, Ogasawara K, Nakao K, Nakaya T, Katsuki M, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. 2000. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity 13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honda K, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. 2006. Type I interferon gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity 25:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menachery VD, Leib DA. 2009. Control of herpes simplex virus replication is mediated through an interferon regulatory factor 3-dependent pathway. J Virol 83:12399–12406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00888-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thackray LB, Duan E, Lazear HM, Kambal A, Schreiber RD, Diamond MS, Virgin HW. 2012. Critical role for interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) and IRF-7 in type I interferon-mediated control of murine norovirus replication. J Virol 86:13515–13523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01824-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freaney JE, Kim R, Mandhana R, Horvath CM. 2013. Extensive cooperation of immune master regulators IRF3 and NFkappaB in RNA Pol II recruitment and pause release in human innate antiviral transcription. Cell Rep 4:959–973. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ourthiague DR, Birnbaum H, Ortenlof N, Vargas JD, Wollman R, Hoffmann A. 2015. Limited specificity of IRF3 and ISGF3 in the transcriptional innate-immune response to double-stranded RNA. J Leukoc Biol 98:119–128. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A1014-483RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashley CL, Abendroth A, McSharry BP, Slobedman B. 2019. Interferon-independent upregulation of interferon-stimulated genes during human cytomegalovirus infection is dependent on IRF3 expression. Viruses 11:246. doi: 10.3390/v11030246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesarman E. 2014. Gammaherpesviruses and lymphoproliferative disorders. Annu Rev Pathol 9:349–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutia BM, Allen DJ, Dyson H, Nash AA. 1999. Type I interferons and IRF-1 play a critical role in the control of a gammaherpesvirus infection. Virology 261:173–179. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krug LT, Pozharskaya VP, Yu Y, Inoue N, Offermann MK. 2004. Inhibition of infection and replication of human herpesvirus 8 in microvascular endothelial cells by alpha interferon and phosphonoformic acid. J Virol 78:8359–8371. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8359-8371.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood BM, Mboko WP, Mounce BC, Tarakanova VL. 2013. Mouse gammaherpesvirus-68 infection acts as a rheostat to set the level of type I interferon signaling in primary macrophages. Virology 443:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharp NA, Arrand JR, Clemens MJ. 1989. Epstein-Barr virus replication in interferon-treated cells. J Gen Virol 70:2521–2526. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-9-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton ES, Lutzke ML, Rochford R, Virgin HW. 2005. Alpha/beta interferons regulate murine gammaherpesvirus latent gene expression and reactivation from latency. J Virol 79:14149–14160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14149-14160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentz GL, Liu R, Hahn AM, Shackelford J, Pagano JS. 2010. Epstein-Barr virus BRLF1 inhibits transcription of IRF3 and IRF7 and suppresses induction of interferon-beta. Virology 402:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cloutier N, Flamand L. 2010. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen inhibits interferon (IFN) β expression by competing with IFN regulatory factor-3 for binding to IFNB promoter. J Biol Chem 285:7208–7221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Areste C, Mutocheluh M, Blackbourn DJ. 2009. Identification of caspase-mediated decay of interferon regulatory factor-3, exploited by a Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus immunoregulatory protein. J Biol Chem 284:23272–23285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang S, Kim KS, Flano E, Wu TT, Tong LM, Park AN, Song MJ, Sanchez DJ, O'Connell RM, Cheng G, Sun R. 2009. Conserved herpesviral kinase promotes viral persistence by inhibiting the IRF-3-mediated type I interferon response. Cell Host Microbe 5:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JT, Doong SL, Teng SC, Lee CP, Tsai CH, Chen MR. 2009. Epstein-Barr virus BGLF4 kinase suppresses the interferon regulatory factor 3 signaling pathway. J Virol 83:1856–1869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01099-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mboko WP, Rekow MM, Ledwith MP, Lange PT, Schmitz KE, Anderson S, Tarakanova VL. 2017. Interferon regulatory factor 1 and type I interferon cooperate to control acute gammaherpesvirus infection. J Virol 91:e01444-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01444-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen LL, Mork N, Reinert LS, Kofod-Olsen E, Narita R, Jorgensen SE, Skipper KA, Honing K, Gad HH, Ostergaard L, Orntoft TF, Hornung V, Paludan SR, Mikkelsen JG, Fujita T, Christiansen M, Hartmann R, Mogensen TH. 2015. Functional IRF3 deficiency in a patient with herpes simplex encephalitis. J Exp Med 212:1371–1379. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efstathiou S, Ho YM, Hall S, Styles CJ, Scott SD, Gompels UA. 1990. Murine herpesvirus 68 is genetically related to the gammaherpesviruses Epstein-Barr virus and herpesvirus saimiri. J Gen Virol 71:1365–1372. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-6-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Efstathiou S, Ho YM, Minson AC. 1990. Cloning and molecular characterization of the murine herpesvirus 68 genome. J Gen Virol 71:1355–1364. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-6-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virgin HW, Latreille P, Wamsley P, Hallsworth K, Weck KE, Dal Canto AJ, Speck SH. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 71:5894–5904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.8.5894-5904.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarakanova VL, Suarez FS, Tibbetts SA, Jacoby M, Weck KE, Hess JH, Speck SH, Virgin HW. 2005. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection induces lymphoproliferative disease and lymphoma in BALB b2 microglobulin deficient mice. J Virol 79:14668–14679. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14668-14679.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandal P, Krueger BE, Oldenburg D, Andry KA, Beard RS, White DW, Barton ES. 2011. A gammaherpesvirus cooperates with interferon-alpha/beta-induced IRF2 to halt viral replication, control reactivation, and minimize host lethality. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002371. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson KE, Tarakanova VL. 2020. Gammaherpesviruses and B cells: a relationship that lasts a lifetime. Viral Immunol 33:316–326. doi: 10.1089/vim.2019.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coleman CB, McGraw JE, Feldman ER, Roth AN, Keyes LR, Grau KR, Cochran SL, Waldschmidt TJ, Liang C, Forrest JC, Tibbetts SA. 2014. A gammaherpesvirus Bcl-2 ortholog blocks B cell receptor-mediated apoptosis and promotes the survival of developing B cells in vivo. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003916. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman CB, Nealy MS, Tibbetts SA. 2010. Immature and transitional B cells are latency reservoirs for a gammaherpesvirus. J Virol 84:13045–13052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01455-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins CM, Speck SH. 2014. Expansion of murine gammaherpesvirus latently infected B cells requires T follicular help. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins CM, Speck SH. 2012. Tracking murine gammaherpesvirus 68 infection of germinal center B cells in vivo. PLoS One 7:e33230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorley-Lawson DA. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus: exploiting the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 1:75–82. doi: 10.1038/35095584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roughan JE, Thorley-Lawson DA. 2009. The intersection of Epstein-Barr virus with the germinal center. J Virol 83:3968–3976. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02609-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang X, Collins CM, Mendel JB, Iwakoshi NN, Speck SH. 2009. Gammaherpesvirus-driven plasma cell differentiation regulates virus reactivation from latently infected B lymphocytes. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000677. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flaño E, Kim I-J, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. 2002. Gamma-herpesvirus latency is preferentially maintained in splenic germinal center and memory B cells. J Exp Med 196:1363–1372. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins CM, Speck SH. 2015. Interleukin 21 signaling in B cells is required for efficient establishment of murine gammaherpesvirus latency. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004831. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson SJ, Tsao EH, Webb BL, Ye H, Dalton-Griffin L, Tsantoulas C, Gale CV, Du MQ, Whitehouse A, Kellam P. 2007. X box binding protein XBP-1s transactivates the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) ORF50 promoter, linking plasma cell differentiation to KSHV reactivation from latency. J Virol 81:13578–13586. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01663-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun CC, Thorley-Lawson DA. 2007. Plasma cell-specific transcription factor XBP-1s binds to and transactivates the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J Virol 81:13566–13577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01055-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhende PM, Dickerson SJ, Sun X, Feng WH, Kenney SC. 2007. X-box-binding protein 1 activates lytic Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in combination with protein kinase D. J Virol 81:7363–7370. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00154-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nealy MS, Coleman CB, Li H, Tibbetts SA. 2010. Use of a virus-encoded enzymatic marker reveals that a stable fraction of memory B cells expresses latency-associated nuclear antigen throughout chronic gammaherpesvirus infection. J Virol 84:7523–7534. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02572-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fowler P, Marques S, Simas JP, Efstathiou S. 2003. ORF73 of murine herpesvirus-68 is critical for the establishment and maintenance of latency. J Gen Virol 84:3405–3416. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moorman NJ, Willer DO, Speck SH. 2003. The gammaherpesvirus 68 latency-associated nuclear antigen homolog is critical for the establishment of splenic latency. J Virol 77:10295–10303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.19.10295-10303.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan CS, Lawler C, May JS, Belz GT, Stevenson PG. 2016. Type I interferons direct gammaherpesvirus host colonization. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005654. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rauch I, Muller M, Decker T. 2013. The regulation of inflammation by interferons and their STATs. JAKSTAT 2:e23820. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu SY, Sanchez DJ, Aliyari R, Lu S, Cheng G. 2012. Systematic identification of type I and type II interferon-induced antiviral factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:4239–4244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114981109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. 2005. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp Med 202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacoby MA, Virgin HW, Speck SH. 2002. Disruption of the M2 gene of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 alters splenic latency following intranasal, but not intraperitoneal, inoculation. J Virol 76:1790–1801. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.4.1790-1801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reddy SS, Foreman HC, Sioux TO, Park GH, Poli V, Reich NC, Krug LT. 2016. Ablation of STAT3 in the B cell compartment restricts gammaherpesvirus latency in vivo. mBio 7:e00723-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00723-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarakanova VL, Leung-Pineda V, Hwang S, Yang C-W, Matatall K, Basson M, Sun R, Piwnica-Worms H, Sleckman BP, Virgin HW. 2007. Gamma-herpesvirus kinase actively initiates a DNA damage response by inducing phosphorylation of H2AX to foster viral replication. Cell Host Microbe 1:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darrah EJ, Jondle CN, Johnson KE, Xin G, Lange PT, Cui W, Olteanu H, Tarakanova VL. 2019. Conserved gammaherpesvirus protein kinase selectively promotes irrelevant B cell responses. J Virol 93:e01760-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01760-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanai H, Chiba S, Hangai S, Kometani K, Inoue A, Kimura Y, Abe T, Kiyonari H, Nishio J, Taguchi-Atarashi N, Mizushima Y, Negishi H, Grosschedl R, Taniguchi T. 2018. Revisiting the role of IRF3 in inflammation and immunity by conditional and specifically targeted gene ablation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:5253–5258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803936115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy AA, Rosato PC, Parker ZM, Khalenkov A, Leib DA. 2013. Synergistic control of herpes simplex virus pathogenesis by IRF-3, and IRF-7 revealed through non-invasive bioluminescence imaging. Virology 444:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N, Taniguchi T. 2005. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature 434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosato PC, Katzenell S, Pesola JM, North B, Coen DM, Leib DA. 2016. Neuronal IFN signaling is dispensable for the establishment of HSV-1 latency. Virology 497:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herskowitz JH, Herskowitz J, Jacoby MA, Speck SH. 2005. The murine gammaherpesvirus 68 M2 gene is required for efficient reactivation from latently infected B cells. J Virol 79:2261–2273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2261-2273.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Macrae AI, Usherwood EJ, Husain SM, Flano E, Kim IJ, Woodland DL, Nash AA, Blackman MA, Sample JT, Stewart JP. 2003. Murid herpesvirus 4 strain 68 M2 protein is a B-cell-associated antigen important for latency but not lymphocytosis. J Virol 77:9700–9709. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.17.9700-9709.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarakanova VL, Stanitsa E, Leonardo SM, Bigley TM, Gauld SB. 2010. Conserved gammaherpesvirus kinase and histone variant H2AX facilitate gammaherpesvirus latency in vivo. Virology 405:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frederico B, Milho R, May JS, Gillet L, Stevenson PG. 2012. Myeloid infection links epithelial and B cell tropisms of murid herpesvirus-4. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002935. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weck KE, Kim SS, Virgin Hw IV, Speck SH. 1999. Macrophages are the major reservoir of latent murine gammaherpesvirus 68 in peritoneal cells. J Virol 73:3273–3283. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.4.3273-3283.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tibbetts SA, Suarez F, Steed AL, Simmons JA, Virgin HW. 2006. A gamma-herpesvirus deficient in replication establishes chronic infection in vivo and is impervious to restriction by adaptive immune cells. Virology 353:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rekow MM, Darrah EJ, Mboko WP, Lange PT, Tarakanova VL. 2016. Gammaherpesvirus targets peritoneal B-1 B cells for long-term latency. Virology 492:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.James KR, Soon MSF, Sebina I, Fernandez-Ruiz D, Davey G, Liligeto UN, Nair AS, Fogg LG, Edwards CL, Best SE, Lansink LIM, Schroder K, Wilson JAC, Austin R, Suhrbier A, Lane SW, Hill GR, Engwerda CR, Heath WR, Haque A. 2018. IFN regulatory factor 3 balances Th1 and T follicular helper immunity during nonlethal blood-stage Plasmodium infection. J Immunol 200:1443–1456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anders PM, Montgomery ND, Montgomery SA, Bhatt AP, Dittmer DP, Damania B. 2018. Human herpesvirus-encoded kinase induces B cell lymphomas in vivo. J Clin Invest 128:2519–2534. doi: 10.1172/JCI97053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weck KE, Barkon ML, Yoo LI, Speck SH, Virgin Hw IV. 1996. Mature B cells are required for acute splenic infection, but not for establishment of latency, by murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 70:6775–6780. doi: 10.1128/JVI.70.10.6775-6780.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kulinski JM, Leonardo SM, Mounce BC, Malherbe LP, Gauld SB, Tarakanova VL. 2012. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase controls chronic gammaherpesvirus infection. J Virol 86:12826–12837. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00917-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mboko WP, Mounce BC, Emmer J, Darrah E, Patel SB, Tarakanova VL. 2014. Interferon regulatory factor-1 restricts gammaherpesvirus replication in primary immune cells. J Virol 88:6993–7004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00638-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lange P, Jondle C, Darrah E, Johnson K, Tarakanova VJ. 2019. LXR alpha restricts gammaherpesvirus reactivation from latently-infected peritoneal cells. J Virol 93:e02071-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02071-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]