Abstract

Introduction:

Customer data from direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC GT) are often used for secondary purposes beyond providing the customer with test results.

Objective:

The goals of this study were to determine customer knowledge of secondary uses of data, to understand their perception of risks associated with these uses, and to determine the extent of customer concerns about privacy.

Methods:

Twenty DTC GT customers were interviewed about their experiences. The semi-structured interviews were transcribed, coded, and analyzed for common themes.

Results:

Most participants were aware of some secondary uses of data. All participants felt that data usage for research was acceptable, but acceptability for non-research purposes varied across participants. The majority of participants were aware of the existence of a privacy policy, but few read the majority of the privacy statement. When previously unconsidered uses of data were discussed, some participants expressed concern over privacy protections for their data.

Conclusion:

When exposed to new information on secondary uses of data, customers express concerns and a desire to improve consent with transparency, more opt-out options, improved readability, and more information on future uses and potential risks from direct-to-consumer companies. Effective ways to improve readership about the secondary use, risk of use, and protection of customer data should be investigated and the findings implemented by DTC companies to protect public trust in these practices.

Keywords: Direct-to-consumer, Genetic testing, Privacy, Secondary uses, Ethical Legal and Social Implications

Introduction

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing (DTC GT) companies emerged in the mid-2000s, marketed as a way for people to understand their ancestral background or determine paternity. As the market evolved, companies began offering tests for disease carrier status, pharmacogenomic variants, health-related risks, and physical traits among other things [1]. Unlike traditional genetic tests, DTC GT allows individuals to order genetic tests without a prescription or guidance from a health-care professional. Companies advertise directly to consumers who can purchase a kit online, at a pharmacy, or in retail stores.

As the popularity of DTC GT increases, so do concerns within the genetics community. Opponents to DTC GT raise concerns about analytic validity, lack of pretest and posttest counseling, possible negative psychosocial impacts of results, and the difficulty of test interpretation [1]. Advocates contend that DTC GT allows consumers to raise their genetic awareness, empower their health decisions, and participate in research to help others [2]. This debate has only intensified since March 2018 when the FDA authorized 23andMe to report on select BRCA mutations [3].

A less studied aspect of this debate is the data usage and sharing practices of DTC GT companies and how these practices personally affect consumers. A common practice of DTC GT companies is to use consumer samples and data for other purposes after producing a report on consumer health and/or ancestry [4]. These secondary uses of data include internal research, quality control, marketing, and third-party sales [5]. For example, companies can use customer data to develop, validate, and improve their products. Companies may also conduct research in collaboration with pharmaceutical companies in which customer information, such as de-identified individual-level genetic information and self-reported information, may be used to support the development of new drugs.

Secondary data usage is by no means limited to DTC GT companies. Various public institutions, hospitals, and programs use clinically collected tissue, blood, and health information for quality improvement and research purposes [5, 6]. Key differences between secondary uses by DTC GT companies can include the marketing of a product directly to a consumer to obtain samples, limited availability of medical providers to describe and explain possible uses, and oversight such as Institutional Review Board approval. Additionally, the onus of being informed/consented in DTC GT is on the consumer, whereas the onus is often shared by the consumer, institution, and provider in medical research.

There are risks to using genomic data for secondary uses regardless of how samples are obtained. Risks associated with usage and reidentification of genomic data include, but are not limited to, paternity/civil lawsuits, criminal investigation, life insurance discrimination, impacts to family members due to shared DNA, and national security or immigration uses [7]. Recently, a DTC GT company was used to identify the “Golden State Killer,” raising questions about genetic databases being used for criminal investigations without the knowledge or consent of those in the database [8]. Another concern raised is DTC GT companies' offer to connect customers with other family members. This could allow for unexpected discoveries of misattributed parentage or other family secrets as well as breaching gamete donor anonymity [9, 10].

To address some of these risks, various professional societies have issued guidelines and position statements on DTC GT [11-13]. These guidelines generally recommend that DTC GT companies provide consumers with enough information about tests for them to make informed decisions. However, few companies were found to adequately meet such guidelines [14]. Previous studies have shown that DTC GT websites are a challenge to navigate, contain difficult language, and do not consistently or completely provide the recommended information about secondary data usage and its associated risks [4, 15].

Though these previous studies have analyzed how DTC GT companies communicate data privacy information, consumer understanding of secondary uses of data has not been fully assessed. This study was designed to assess consumer understanding of and concern about secondary uses of data and the associated risks.

Materials and Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Instrumentation

A detailed, semi-structured interview guide was developed by the research team. The interview guide was piloted with cognitive interviews to determine question clarity. After the pilot interviews, minor changes to the guide were made and approved by the University of Utah IRB. The guide consisted of questions in 4 domains:

Participant demographics: education level, age, gender, and ethnicity information were gathered, along with information about brands and types of tests ordered.

DTC GT experience: questions addressed information-seeking habits of participants as well as experience with the company’s privacy policy.

Secondary uses assessment: questions addressed knowledge of secondary uses of data at the time of testing and level of acceptability of hypothetical uses.

Provoked perspectives: reactions to the interview itself, new concerns, and suggestions for DTC GT companies were gathered.

Participants

Individuals aged 18 years and older who had undergone DTC GT and received their results between January 2016 and November 2018 were eligible to participate in the study. Four individuals were used to pilot the interview guide, and 20 individuals were interviewed for the study data. A target sample size of 20 was chosen to allow for code and meaning saturation [16].

Procedures

Participant Recruitment

Pilot interviews were conducted through a convenience sample of 4 individuals. Recruitment for study participants was done via ResearchMatch [17], a national health volunteer registry created by several academic institutions and supported by the US National Institutes of Health as part of the Clinical Translational Science Award program [18]. ResearchMatch has a large population of volunteers who have consented to be contacted by researchers about health studies for which they may be eligible.

E-mails describing the study were sent to individuals matching the qualifying age demographics until 20 individuals agreed to participate in the study. A total of 1,500 e-mails were sent to recruit 43 individuals who agreed to be contacted personally. Of these 43 individuals, 4 were ineligible to participate in the study, as they had not undergone DTC GT within the specified time period or had not yet received their results. Fourteen individuals did not respond after 2 attempts to contact them. Five individuals agreed to be contacted after the 20 study participant slots were filled.

Interviews

All interviews were conducted via telephone by author J.M. At the beginning of each interview, the participant read a consent script, was given an opportunity to ask questions, and verbally agreed to participate in the study. All interview participants, including pilot participants, received a $50 Amazon gift card to thank them for their participation. Each study interview was audio recorded and transcribed by a professional transcription service. Interviews averaged 34 min in length.

Data Analysis

An inductive content analysis approach [19] was used to allow ideas and themes to emerge directly from the interviews rather than fit evidence into a pre-existing theory or model. All interviews were conducted before coding commenced. Transcribed interviews were analyzed using Dedoose software [20]. Parent codes were initially developed from the interview guide as a way to categorize subcodes as they emerged. The subcodes were created to describe and summarize participants’ answers and comments. New codes were created only when previous codes were not sufficient to describe a comment.

All 20 transcripts were independently coded by 2 of the authors (J.M. and B.B.), followed by consensus coding of all interviews by the 2 coders. This coding strategy provided investigator triangulation [21]. Code application analysis across interviews determined the appearance and prevalence of themes. Periodic meetings were held with all authors to monitor methodological decisions, data collection, and data analysis.

Results

Participant Demographics

Characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. Sixteen of the 20 participants had done DTC testing only once, whereas 4 participants had done DTC testing twice. Of the 24 tests ordered by the participants, 13 were ordered from AncestryDNA [22] for ancestry purposes. Eleven of the tests were ordered from 23andMe [23], 3 for ancestry purposes and 8 for health and ancestry.

Table 1.

Participant (N = 20) demographic characteristics at the time of study

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (range), years | ||

| 30–39 | 2 | 10 |

| 40–49 | 3 | 15 |

| 50–59 | 4 | 20 |

| 60–69 | 7 | 35 |

| 70–79 | 3 | 15 |

| 80–89 | 1 | 5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 15 | 75 |

| Male | 5 | 25 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 19 | 95 |

| African-American | 1 | 5 |

| Education | ||

| Some college | 3 | 15 |

| Bachelor’s | 7 | 35 |

| Master’s | 9 | 45 |

| PhD | 1 | 5 |

DTC GT Experience

The majority of participants indicated their primary reason for ordering the DTC GT kit was for ancestry and/or health information. Secondary reasons participants stated for ordering the kit was for fun or a family project, it was marketed or recommended to them, and/or they wanted to confirm another test. Most participants expressed positive comments regarding genetic testing and considered the results useful, interesting, or fun.

Minimal Experience with Privacy Policy

The majority of participants stated they were either certain or believed a privacy policy existed. When those participants were asked how much of the policy they read, the majority recalled minimally reading the policy, if at all. The most frequent reason given for not reading the privacy policy was that it was not a statement the participants normally read. I’m just lazy about reading those things (Participant 13, 68-year-old woman). I don’t normally read that information (Participant 1, 47-year-old woman).

Other reasons stated for not reading the privacy policy were that the participants already considered themselves informed, they thought the information was irrelevant, or they did not think they would understand it.

Variety of Opinions about Genetic Privacy

Without being asked, many participants commented about genetic privacy. Some considered genetic privacy important to maintain, some expressed a belief that privacy is already compromised in multiple ways, and others considered privacy violations worth the risk in order to receive desired information. We have such a problem with privacy today. Everybody knows everything about me already. I don’t need them knowing any more than they already do (Participant 20, 75-year-old man). I don’t trust any company, but I wanted the information for myself, and I was willing to take the risk that, at some point or another, somebody may hack in (Participant 1, 47-year-old woman).

Secondary Uses Assessment

Some Knowledge about Information Use

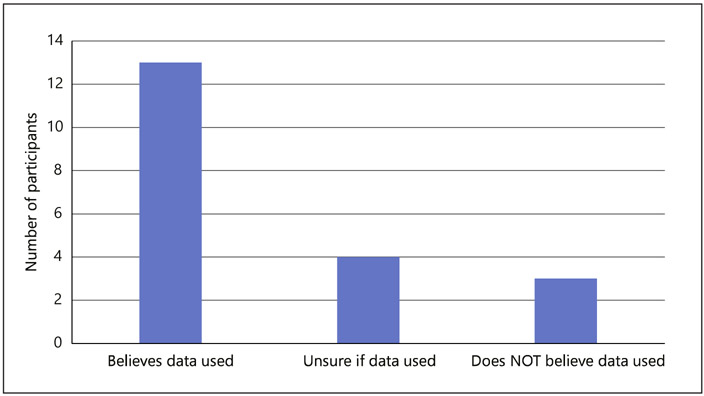

Participants were asked if they thought their genetic information or sample was used by the DTC GT company for any purpose outside of giving the participant their results. Participant awareness of secondary uses of data is summarized in Figure 1. The majority of participants stated they believed it was used for some other purpose. The most frequent use identified by participants was for internal purposes, such as improving products. I think they cross-reference it with other samples to update estimates (Participant 11, 47-year-old man). It increases their sample. … everybody’s looking for a larger database (Participant 2, 82-year-old woman).

Fig. 1.

Participant awareness of secondary uses of data.

A minority of participants identified other possible uses for data such as health/disease research, third-party sales, law enforcement, and insurance discrimination.

Spectrum of Acceptability of Secondary Uses

Participants were then asked about the acceptability of hypothetical secondary uses of data. These uses included research and non-research purposes. Participants were given examples of law enforcement, cloning, product development, and selling of information as non-research purposes. All participants stated that research was an acceptable use of their data. When asked about non-research secondary uses, a majority stated some level of non-research purposes were acceptable. This ranged from all the examples given being deemed acceptable, to some uses that were acceptable while others were not. I don’t have a problem with any of it (secondary uses); (Participant 9, 62-year-old woman). Medical research, no problem… fine tuning their product, no problem. If I was suddenly getting drug company commercials coming to me based on what I had said, that would be too invasive for me (Participant 10, 52-year-old woman).

The acceptability of data usage for law enforcement purposes varied across the participants. A majority of participants stated that this was to some degree acceptable, though this could include limits. I guess using it for law enforcement isn’t a severe crime, like I know… DNA things that helped them find that serial killer… that is understandable, but if they found a way to use the saliva and figured out who smoked marijuana and then sent that to all the police departments that would not be cool (Participant 8, 32-year-old woman).

However, some participants did not approve of data being used for law enforcement purposes. Those who did not approve of data usage for law enforcement stated concerns over privacy and that their intended purpose of giving data was for recreational uses, as reasons for lack of approval. That’s not what the purpose of this (DTC GT company name) is. If you wanna go to… CODIS… where the DNA’s all stored on criminals, that’s fine, but I did not put my DNA out there to be compared to a criminal. I put it out there to see where my ancestry came from (Participant 15, 63-year-old woman).

Opinions about acceptability of data used for third-party sales similarly varied across the participants. A majority of participants stated that they did not approve of selling data. The most common reason participants stated as a reason for disapproval was the dislike of company profit from personal data: I don’t think it’s appropriate for them to further profit off of what you’ve provided (Participant 11, 47-year-old man). I don’t see any good, useful reasons (why they would sell data). I guess I could see them selling it to pharmaceutical companies – you know a large population that uses our product has this gene that causes this disease or something – but even that, I’m not a huge fan of the big pharmaceutical companies, which is crazy because I take a ridiculous amount of medicine (Participant 8, 32-year-old woman).

Other participants stated that they could find some level of acceptability of data being sold to third parties. Some of these participants stated scenarios where selling data could be appropriate. I think it depends. Like, I have no problems with the GlaxoSmithKline deal, because here is a company that’s in it to develop new drugs… but it would have to be on a case-by-case basis, because there could be a time when they would sell it to somebody I don’t like (Participant 7, 34-year-old woman). I think it’s specific to the purpose. For me if it’s a research purpose, if it’s going to an academic institution? Yeah, you guys can have it. I’m not at all concerned about that. If it’s going to a pharmaceutical company for a product development of some variety, yeah I’m going to want to know about that. I’m not saying that I’m going to say “no, they can't have it,” but I definitely want to know what they’re doing with it (Participant 18, 50-year-old woman).

Participants were asked if they were aware of laws in existence that protect individuals from genetic discrimination in the workplace and for insurance. Most participants were not aware of the existence of such laws. A minority believed there was some form of protection for genetic information, but only some of these participants were able to give specifics like the name of the law or its protections.

When asked if they would be more or less concerned if their data were used for secondary purposes by the medical community versus a DTC GT company, the majority of participants stated they would trust the medical community more. A minority of participants specified there was no difference between the 2 entities, while no participants specified they would trust the DTC GT above the medical community. The 3 main themes for less trust in a DTC GT company were that the medical community has better research standards, companies are for profit, and the purpose of the medical community is for helping people. I know how carefully we’ll (people at institutions) protect information, and we have IRBs in place. And I know how carefully we think about those issues. So, I probably would trust the universities more, just because they’re not in it to make a profit, they’re in it to advance knowledge. Any of those direct-to-consumer companies are in it to make a profit, and I feel like their philosophy’s probably, like, if we can also advance human knowledge and help people, that’s great. So, they’re trying to kind of have it both ways (Participant 7, 34-year-old woman). The companies are for-profit, where, I think, the medical centers are for actual cures, and results. I kinda link pharmaceuticals to (DTC GT company name), because they are in it for the money, too. I don’t think I would willingly take part in pharmaceutical research (Participant 15, 63-year-old woman).

Provoked Perspectives

Reactions to the Interview

The majority of participants discussed how the interview brought up information they had not previously considered. I’m kind of shocked that I haven't actually thought deeply about what these companies were doin’ with my DNA or the security of it. I really hadn’t. I just – I’m trusting, even though I think I’m more informed than a lot of people on what’s goin’ on with that stuff. But now I’m gonna have to find out (Participant 5, 62-year-old woman). Well, I guess they could sell the information to an insurance company, as you mentioned life insurance company, or health insurance company. I can see that information being real useful to those types of companies. I never really gave it much thought until you asked me the question. That’s the first thing that comes to my mind, those insurance companies (Participant 14, 74-year-old man).

A minority of participants discussed the opposite that the interview did not bring up new points to consider: I mean, I’ve got no problem with it (data being used for secondary purposes) … I’ve thought about this before because I’ve been in studies. You know, there’s just no problem if it’s a contractor, a vendor, or if it’s a research group or if it’s only for my purpose. I’ve just got no problem with it (Participant 9, 62-year-old woman).

Some of participants expressed a feeling akin to guilt, shame, or embarrassment for not knowing more about companies’ policies. For example, when asked if they were aware if the DTC GT company could sell customer samples or data, some participants expressed such feelings. I’m embarrassed to say that I don’t know if they can, but I would imagine that they can (Participant 6, 47-year-old woman). You would think with my more exposure to… genetic testing that I would’ve been more diligent in checking those things out. But, I guess I’m a trusting soul and probably a lot of the population is and maybe shouldn’t be. So, you’re raising questions that I’m finding myself questing myself that I – maybe I should’ve been more diligent in checking those things out (Participant 2, 82-year-old woman).

New Question and Concerns

When asked to describe new concerns that arose due to the interview, half of the participants expressed questions or concerns over how their information could be used: I guess the concern is now I’m wanting to know about, was my stuff used or is my stuff being used for things other than what I thought it was? (Participant 12, 58-year-old woman). I wish I wouldn’t have did the Ancestry test. I paid to give them information about me that they're probably using for other stuff (Participant 16, 60-year-old woman).

Suggestions for Companies

The majority of participants had suggestions for DTC GT companies improving the information provided, so customers can give adequately informed consent. These included better transparency about data usage, more opt-out options, easier readability of privacy policy, and more information/resources on data usage and risks from DTC GT. Just keep everyone very aware of what you’re doing. I guess terms of service and stuff are so long and detailed. It would be nice if it was a little more user friendly in the reading and less legalese. That would be rather nice. Saying specifically what they’re going to use it for without getting too difficult to understand it (Participant 10, 52-year-old woman). If there is going to be use of DNA for purposes other than what they said, which is basically seeing where your family came from and possibly identifying other family members, that there’s going to be use of that for other things. That one, they make that clearer, and two, there is the ability for people to say yes or no, don’t wanna do that. If there is, I don’t think there should be financial gain by (company name) in that (Participant 12, 58-year-old woman).

Discussion/Conclusion

This qualitative study examines DTC GT customer understanding of secondary uses of data and the associated risks. Previous studies assessed the quality of information given about secondary data usage but not how this information is interpreted by customers. This study describes the participants’ experiences with DTC GT and genetic privacy, assesses their knowledge and opinions about secondary data usage, and identifies customer concerns and suggestions for DTC GT companies.

Consistent with studies that showed there is poor readership of “terms of service” agreements [24], the majority of our participants did not read the majority of the privacy policy. Reasons for not reading the privacy policy were that the participants considered themselves informed, thought the information was irrelevant, did not think they would understand it, or typically did not read privacy policies. There were 2 main divisions of participants’ opinions about genetic privacy. Some felt it was important and therefore should be protected, while others believed there in an inherent risk of loss of privacy but the information from the test results was worth that risk.

This study shows participants are aware of some secondary uses of data by DTC GT companies, but no participant was able to name all possible uses of data. When given examples of hypothetical secondary uses of data, participants had a variety of opinions on the acceptability of non-research secondary data usage. Some participants were approving of any possible non-research use, while others stated the contrasting opinion that all non-research uses would be unacceptable. Still other participants gave example of scenarios that would be acceptable while other scenarios remained unacceptable. Not one participant shared the exact same opinion or reason for that opinion as another, exemplifying the spectrum of diverse beliefs.

This study also explored participants’ level of trust in entities using data for secondary purposes. The majority of participants stated they would trust the medical community with their data more than a company. This was because participants felt the medical community has greater research oversight and a primary goal of helping people rather than making a profit.

These findings can be useful for those considering a DTC test. It was found that awareness of all possible secondary uses of data to be low. Participants who were initally unaware of possible secondary uses of data expressed concern over how their data may be used. Previous studies have shown that as people are exposed to risk information, they are less likely to pursue genetic testing [25]. Health-care providers and other individuals consulted for opinions about DTC GT can address possible risks and the common gaps in consumer awareness. There have been some efforts in the public health realm to provide consumer education about DTC GT [26, 27]. These efforts could expand to ensure consumers are aware that their data could be used for secondary uses including third-party sales and law enforcement, as this information could possibly influence their decision to pursue testing.

These findings can also be useful for DTC GT companies. The suggestions from participants can be used to help companies improve the information given to customers on data usage. Consistent with previous data showing that privacy policies contain difficult language [15], these participants desire easier readability of these policies. It has similarly been suggested that the current privacy statements provided by the companies are insufficient for providing information on testing risks and an informed consent process should be used instead [28, 29]. Supporting this idea, some of the participants stated a desire for a more formal consent process, such as those used for research studies.

Study limitations include a bias toward approval of research as interviewees previously consented to be contacted about research studies; therefore, their opinions may not be generalizable to the DTC GT customer population as a whole. Compared to the US population, our sample was disproportionally female, white, and college educated. However, these characteristics are typical of the DTC GT customer population as a whole [30]. This is supported by other research, suggesting that awareness of DTC GT is higher in these populations as well [31].

Although this study’s participant demographics matched those of the DTC GT customer population, further research should investigate the experiences of minority populations. As the DTC GT market continues to grow and become more accessible [32, 33], beliefs and opinions of underrepresented populations would be useful to inform DTC GT customers and companies of alternative privacy concerns and knowledge gaps on secondary uses of data.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The authors would like to thank the National Society of Genetic Counselors Public Policy Committee as well as the University of Utah’s Graduate Program in Genetic Counseling for their financial support for this research project.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB_00114603). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants at the beginning of the interview.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Niemiec E, Kalokairinou L, Howard HC. Current ethical and legal issues in health-related direct-to-consumer genetic testing. Per Med. 2017;14(5):433–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turrini M, Prainsack B. Beyond clinical utility: the multiple values of DTC genetics. Appl Transl Genom. 2016;8:4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commissioner Oot. Press Announcements: FDA authorizes, with special controls, direct-to-consumer test that reports three mutations in the BRCA breast cancer genes. 2018.

- 4.Niemiec E, Howard HC. Ethical issues in consumer genome sequencing: use of consumers’ samples and data. Appl Transl Genom. 2016; 8:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safran C, Bloomrosen M, Hammond WE, Labkoff S, Markel-Fox S, Tang PC, et al. Toward a national framework for the secondary use of health data: an American Medical Informatics Association White Paper. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis MH, Goldenberg A, Anderson R, Rothwell E, Botkin J. State laws regarding the retention and use of residual newborn screening blood samples. Pediatrics. 2011; 127(4): 703–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Doherty KC, Christofides E, Yen J, Bentzen HB, Burke W, Hallowell N, et al. If you build it, they will come: unintended future uses of organized health data collections. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrini CJ, Robinson JO, Petersen D, McGuire AL. Should police have access to genetic genealogy databases? Capturing the golden state killer and other criminals using a controversial new forensic technique. PLoS Biol. 2018; 16(10): e2006906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper JC, Kennett D, Reisel D. The end of donor anonymity: how genetic testing is likely to drive anonymous gamete donation out of business. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(6): 1135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moray N, Pink KE, Borry P, Larmuseau MH. Paternity testing under the cloak of recreational genetics. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017; 25(6):768–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACMG Board of Directors. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a revised position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med. 2016;18(2):207–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson K, Javitt G, Burke W, Byers P. ASHG statement* on direct-to-consumer genetic testing in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 110(6): 1392–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skirton H, Goldsmith L, Jackson L, O’Connor A. Direct to consumer genetic testing: a systematic review of position statements, policies and recommendations. Clin Genet. 2012; 82(3):210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laestadius LI, Rich JR, Auer PL. All your data (effectively) belong to us: data practices among direct-to-consumer genetic testing firms. Genet Med. 2017;19(5):513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner JK, Cooper JD, Sterling R, Royal CD. Tilting at windmills no longer: a data-driven discussion of DTC DNA ancestry tests. Genet Med. 2012;14(6):586–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ResearchMatch 2019. Available from: https://www.researchmatch.org/.

- 18.Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Program 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/.

- 19.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1): 107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dedoose: 8.2.14 2019. Available from: https://app.dedoose.com/App/?Version=8.2.14.

- 21.Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(5):545–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AncestryDNA®∣ DNA Tests for Ethnicity & Genealogy DNA Test 2019. Available from: https://www.ancestry.com/dna/.

- 23.23andMe Inc. Available from: https://www.23andme.com.

- 24.Maronick TJ. Do consumers read terms of service agreements when installing software? – A two-study empirical analysis. Int J Bus Soc Res. 2014;4:137–45. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray SW, Hornik RC, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K. The impact of risk information exposure on women’s beliefs about direct-to-consumer genetic testing for BRCA mutations. Clin Genet. 2012;81(1):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.What is At-Home Genetic Testing. Available from: http://www.aboutgeneticcounselors.com/Genetic-Testing/What-is-At-Home-Genetic-TestingAccessed 2019 Apr 13.

- 27.Direct to Consumer Genetic Testing: Think Before You Spit, 2017. Edition! ∣∣ Blogs ∣ CDC. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunnik EM, Janssens AC, Schermer MH. Informed consent in direct-to-consumer personal genome testing: the outline of a model between specific and generic consent. Bioethics. 2014;28(7):343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobin SL, Cho MK, Lee SSJ, Magnus DC, Allyse M, Ormond KE, et al. Customers or research participants?: guidance for research practices in commercialization of personal genomics. Genet Med. 2012;14(10):833–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carere DA, Couper MP, Crawford SD, Kalia SS, Duggan JR, Moreno TA, et al. Design, methods, and participant characteristics of the Impact of Personal Genomics (PGen) study, a prospective cohort study of direct-to-consumer personal genomic testing customers. Genome Med. 2014;6(12):96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salloum RG, George TJ, Silver N, Markham MJ, Hall JM, Guo Y, et al. Rural-urban and racial-ethnic differences in awareness of direct-to-consumer genetic testing. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apathy NC, Menser T, Keeran LM, Ford EW, Harle CA, Huerta TR. Trends and gaps in awareness of direct-to-consumer genetic tests from 2007 to 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2018; 54(6):806–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Check Hayden E The rise and fall and rise again of 23andMe. Nature. 2017;550(7675): 174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]