Abstract

Complex trauma (CT) is the experience, or witness, of prolonged abuse or neglect that negatively affects children’s emotional and psychological health. Youth in residential care experience higher incidences of complex trauma than youth in community-based care, with notable gender differences and presentation of psychological symptoms. This study examined the effects of trauma-informed residential care and the relation between CT and gender. A sample (n = 206) from an evaluation of a youth psychiatric residential facility in the Midwest that transitioned from a traditional care model to a trauma-informed care model was used. A hierarchical regression was used to model the main effects of model of care, gender, CT, length of stay, and crisis response on treatment outcomes; and the moderating effects of gender and CT. The results support the high prevalence of CT in residential care populations. The final model explained 30.2% of the variance with a statistically significant interaction between gender and length of stay in treatment, indicating that longer lengths of stay in treatment are associated with less change in functional impairment for girls than boys. Youth gender and prior trauma are important factors to consider when monitoring experiences and treatment outcomes in youth residential care.

Keywords: Complex trauma, Trauma-informed care, Psychiatric residential treatment, Therapeutic residential care, Child welfare, Trauma, Intervention, Treatment

Complex trauma (CT) in children and adolescents has received increasing attention within the academic and practice communities (Arvidson et al. 2011; Schore 2001; Spinazzola et al. 2005). In comparison to experiencing an acute traumatic event, CT is the experience, or witness, of multiple traumatic events and is often prolonged over time (Van der Kolk 2005). Complex trauma often results from unstable, stressful environments that negatively affect a child’s self-regulatory skills, emotional regulation, relationships, psychological well-being, substance use, and identity development (Cook et al. 2005; Lawson and Quinn 2013; Van der Kolk 2005). Maladaptive or developmentally incongruent ways of self-regulating or responding to environmental stressors may be used by youth who have experienced CT (Kinniburgh et al. 2005).

Complex trauma may occur at any phase of a youth’s development, however, an increasing number of children under the age of 3 years old experience early childhood trauma at a rate of 14.8 children per 1000 (Child Maltreatment 2016). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network found that 70.4% of youth in foster care (n = 2251) reported exposure to at least two traumas that constitute CT and 11.7% of the sample reported exposure to all five types of traumas measured (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and domestic violence; Greeson et al. 2011).

Youth who experience CT may have difficulty successfully navigating home, school, and community environments, possibly requiring behavioral or mental health supports. These supports include but are not limited to: Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), outpatient therapeutic services, psychotropic medication management, or, in more severe circumstances, residential treatment; the focus of this study. In a nation-wide study of youth in residential (n = 525) and non-residential care settings (n = 9942), Briggs et al. (2012) found statistically significant differences in the rates of youth experiencing CT in residential (92%) than in community-based care (77%).

Research findings also show that the type and symptoms of maltreatment differs between boys and girls. Compared to boys, girls are more likely to report sexual abuse (Collin-Vézina et al. 2011) and report internalized symptoms of trauma (Maschi et al. 2008). High rates of CT among youth in residential treatment and varying experiences of maltreatment and trauma may impact gender-specific coping responses (Eschenbeck et al. 2007). Trauma-focused services are increasingly viewed as an essential factor to effective services. The purpose of this current study was to examine the relation between youth gender, complex trauma, and treatment conditions on treatment outcomes in youth in therapeutic residential care.

Therapeutic Residential Care for Youth

Out-of-home placements are viable options for youth when community-based care or family preservation services are not appropriate (Briggs et al. 2012). According to the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System, 13% of youth (n = 53,910) involved in the child welfare system were living in some form of residential care in 2017 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2018). Therapeutic residential treatment centers (TRCs) are out-of-home placements that are more treatment-intensive than traditional group homes, yet less restrictive than psychiatric in-patient units (Larzelere et al. 2001); and include the youth’s family, school, culture and community as both formal and informal supports to meet the behavioral and mental health needs of the youth (Whittaker et al. 2014). Many TRCs employ specific treatment models such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT; Weiner et al. 2009) or The Sanctuary Model (Esaki et al. 2013), and demonstrate promising outcomes. Boys Town utilizes an adapted version of the Teaching Family Model (Phillips et al. 1974), which reinforces the daily use of self-regulatory skills while teaching positive social skills to replace maladaptive ways of coping with stress and anger (Larzelere et al. 2001). An evaluation of the Boys Town TRC showed statistically significant decreases in youth’s overall internalizing and externalizing symptoms from admission to discharge; with caregivers reporting that 76% of youth experienced improved quality of life after participating in TRC (Larzelere et al. 2001). Maintenance of treatment improvements was attributed to providing youth with specialized aftercare services (Larzelere et al. 2001).

Not all empirical evidence supports the long-term outcomes of TRCs. In a narrative review of 15 outcome studies on the effectiveness of TRCs, Frensch and Cameron (2002) found that despite the wide variability of the programming, participation in TRCs improves some, but not all, youths’ functioning during treatment. Likewise, a review of 27 pre- and quasi-experimental studies of youth outcomes following TRC showed that programs emphasizing behavioral-therapeutic modalities and family involvement showed the most promising results (Knorth et al. 2008). Neither study presented strong evidence supporting the long-term maintenance of treatment gains (Frensch and Cameron 2002; Knorth et al. 2008).

Evidence shows that CT is prevalent among youth in TRC (Brady and Caraway 2002; Briggs et al. 2012; Zelechoski et al. 2013) and that TRC is effective in addressing a range of symptoms, at least in the short-term (Brady and Caraway 2002; Briggs et al. 2012; Zelechoski et al. 2013). However, there is little evidence showing how CT and gender differences influence experiences and outcomes of youth in TRC (Frensch and Cameron 2002; Joiner and Buttell 2018; Knorth et al. 2008).

Trauma, Gender, and Residential Treatment Factors

Therapeutic residential treatment centers are more likely to encounter youth who have experienced CT than other treatment settings (Briggs et al. 2012). Results from a descriptive study of youth in residential care showed that 97.6% of the sample (n = 41) had experienced at least one traumatic experience, with most youths experiencing multiple traumas (Brady and Caraway 2002). Compared to youth served in non-residential care settings, those in residential care are more likely to have experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, domestic violence, traumatic loss, school violence, community violence, and have an impaired caregiver (Briggs et al. 2012; Zelechoski et al. 2013). Moreover, these youth exhibit more behavioral, academic, substance use and attachment problems with higher rates of delinquency, elopement, self-harm and suicidality (Briggs et al. 2012; Zelechoski et al. 2013). Results of an another study, using a smaller sample of youth in TRC (n = 53), showed high rates of abusive and neglectful experiences, with most youth having high rates of depression, anger, posttraumatic stress, and dissociation associated with experiencing multiple forms of trauma (Collin-Vézina et al. 2011). The improvement of trauma-screening tools coupled with the development of more individualized and empirically supported treatments for youth with CT receiving services in TRCs is necessary to support the specific treatment needs of this population.

Although the aforementioned evidence lends support for trauma-informed care models, treatment factors, such as crisis response and length of stay in TRC, impact treatment outcomes. Crisis response interventions, such as restraint or seclusion pose a risk to positive treatment outcomes (Sunseri 2001, 2004), yet, there is still a reliance on the use of such techniques within conventional and trauma-informed TRC programs (Azeem et al. 2011; Muskett 2014). There is concern that the use of restraints and seclusions, or witnessing restraints of others, may exacerbate youth behavior or re-traumatize youths with maltreatment histories (Fox 2004; Zelechoski et al. 2013). To minimize re-traumatizing youth, some TRCs use trauma-informed debriefing following any restraint or seclusion incidents (Brown et al. 2012).

Empirical evidence related to the impact of how long a youth stays in TRC on their treatment outcomes is ambiguous. Both longer (Chow et al. 2014; Farmer et al. 2017) and shorter (Hoagwood and Cunningham 1992; Pfeiffer and Strzelecki 1990) lengths of stay in TRC have been identified as supports for positive outcomes. However, other studies indicate that length of stay in TRC has no significant impact on treatment outcomes (Loughran et al. 2009; Winokur et al. 2008). Identifying factors that moderate length of stay in treatment is an important step in determining differential treatment modes for youth with CT.

In addition to trauma-informed care for youth in TRCs, there is a growing evidence supporting youth gender as an important treatment consideration. Evidence suggests that girls in TRC are at greater risk for experiencing negative outcomes compared to boys (Chow et al. 2014; Eisengart et al. 2008). Girls served in TRCs are likely to present with more severe internalizing symptoms (Maschi et al. 2008) and higher levels of psychopathology (Hussey and Guo 2002) than boys. They are also more likely to be diagnosed with affective or anxiety disorders (Connor et al. 2004); with three times the rate of depression and two times the rate of anxiety as compared to boys (Handwerk et al. 2006). Boys are more likely than girls to be diagnosed with behavioral disorders (Connor et al. 2004); while girls have been found to score higher than boys on both internalizing and externalizing behavior scales (Handwerk et al. 2006). Girls in TRCs are also more likely to self-report substance use (Connor et al. 2004; Handwerk et al. 2006; Zelechoski et al. 2013), exhibit higher levels of verbal aggression (Connor et al. 2004; Handwerk et al. 2006; Zelechoski et al. 2013), physical assault (Connor et al. 2004), sexual abuse (Handwerk et al. 2006), and self-injurious behaviors (Connor et al. 2004; Handwerk et al. 2006; Zelechoski et al. 2013) than boys. Handwerk et al. (2006) also found that girls’ length of stay in treatment was longer than boys by an average of 2 months. With the high prevalence of CT and evidence of gender differences among youth in residential care, there is an increased need to examine the relation between CT, gender, and treatment conditions on treatment outcomes.

Purpose and Study Hypotheses

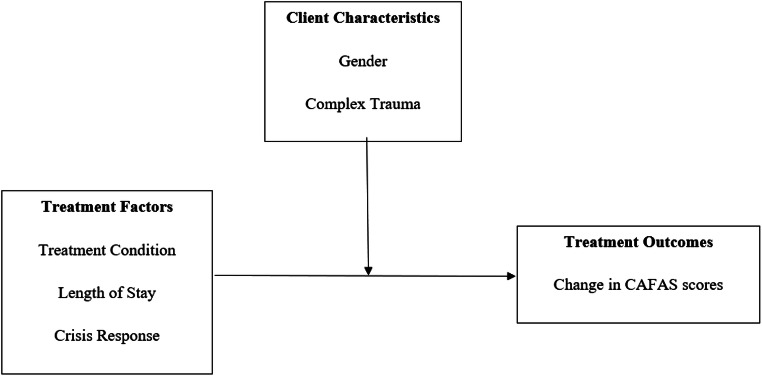

Evidence suggests that girls in residential treatment present with more intense symptoms and trauma histories than boys but residential care models lack evidence supporting gender-specific treatment components. Additionally, while typically discouraged within trauma-informed care models, crisis response interventions are employed and considered a risk for re-traumatization. Understanding how gender and CT affect treatment outcomes may lend evidence to inform gender-specific treatment services. The purpose of this study was to examine the relation among gender, complex trauma, and treatment conditions on treatment outcomes of youth in TRC. As depicted in Fig. 1, the following hypotheses were tested:

Hypothesis 1: Crisis response and length of stay will predict treatment outcomes of youths in TRC.

Hypothesis 2: Youth gender will moderate the relation between treatment conditions and treatment outcomes.

Hypothesis 3: Trauma complexity (no trauma exposure increasing to complex trauma) will moderate the relation between treatment conditions and treatment outcome.

Fig. 1.

Model of youth treatment experience

Methodology

Participants

Secondary data was used from a program evaluation of a Midwestern youth psychiatric residential facility that transitioned from a traditional psychiatric residential treatment model (PRT) to a trauma-informed psychiatric residential treatment model (TI-PRT; Boel-Studt 2017). Both treatment models met criteria for TRC (Whittaker et al. 2014), including 24-h provision of care, educational services, individual therapy, family therapy, and psychiatric services (Boel-Studt 2017). The TI-PRT treatment model included trauma-focused individual therapy, comprehensive staff training on trauma orientation, daily check-ins, family/caregiver training, and trauma recovery group-based curriculum (Boel-Studt 2017).

Information from youths’ records were extracted post-discharge with a total of 206 youth in either the PRT (n = 104) or TI-PRT (n = 102) represented in the sample. The sample was slightly more male (58.7%) and mostly white (70.9%), followed by multiracial (13.6%), and black (10.2%). The four types of documented or suspected abuse of were reported: physical (48.1%), sexual (33.5%), emotional (55.3%), and neglect (49.0%). More than half of the sample (56.8%) experienced complex trauma (two or more types of abuse). Fifty females (58.82%) and 67 males (55.40%) experienced complex trauma prior to admission to treatment. Thirty-two females (37.6%) and 36 males (29.8%) did not require any crisis response intervention while in treatment, 12 females (14.1%) and 35 males (28.9%) required minimal crisis response interventions (1–5 incidents) during treatment; while 41 females (48.2%) and 50 males (41.3%) required six or more incidents of crisis intervention while in treatment. Additional descriptive information is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for continuous variables

| Variable | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 206 | 10.62 | 2.71 |

| Complex Trauma | 206 | 1.86 | 1.46 |

| Length of Stay in Treatment (weeks) | 206 | 39.2 | 18.68 |

| Change in CAFAS from Admission to Discharge | 206 | −57.91 | 36.67 |

Measures

The independent variables were age, complex trauma, youth gender, treatment condition, length of stay in treatment and crisis response. Guided by the conceptual definition of CT being the experience, or witness, of multiple traumatic events and is often prolonged over time (Van der Kolk 2005); a proxy measure of CT was created as a continuous variable on a scale of zero to four, based on the sum of types of documented and suspected abuse a youth had experienced, as reported at intake. Types of documented or suspected abuse reported were physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. For example, a youth with documented physical and emotional abuse reported during their intake assessment would score a ‘2’ on the CT scale. The scale presented with acceptable reliability (ICC Cronbach’s α = .72). Youth gender was dichotomized as either male or female. Treatment condition was dichotomized as participating in traditional PRT or TI-PRT. The length of stay in treatment was measured continuously in weeks. Crisis response was measured categorically based on the number of crisis response incidents during the youth’s treatment episode (none, one to five, six or more).

The dependent variable was the overall functioning of adolescents; measured using the total scores of the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS; Bates et al. 2006). Adolescent behavior was ranked by a trained, Master’s level case manager in the life domains of role performance, behavior toward self/others, moods/self-harm, thinking, and substance use (Bates et al. 2006). Adolescent’s functioning within each domain is rated as severe, moderate, mild, or minimal/no impaired functioning with total scores ranging from 0 to 240 (Bates et al. 2006). For this study, the difference in CAFAS scores from admission to discharge were used to assess changes in functional impairment. Thus, a negative CAFAS change score indicated improvement in functioning during treatment while a positive CAFAS change score indicated a decrease in functioning during treatment.

Results

A three-step hierarchical regression model was used to test the main effects of treatment condition, length of stay, and crisis response on change in CAFAS scores from admit to discharge and the moderating effects of gender and complex trauma experiences of the participants. Assumptions of homogeneity of variance, normality, and independence were assessed and met. Histograms were assessed for normality and indicated a slightly skewed distribution; however, the analysis is robust to violations of this assumption given the larger sample size (Field 2013). The first regression model included youth characteristics: age, gender and complex trauma experiences (see Table 2). No statistically significant variance was explained by the first model (R2 = 0.001; F(3, 202) = 0.077, p = .972).

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression with interaction terms

| Model | B | S.E. | Beta | t scores | 95% CI | R2 | R2Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Constant) | −55.03*** | 10.73 | −5.13 | (−76.81, −33.88) | .001 | ||

| Age (yrs) | −.37 | .97 | −.03 | −.38 | (−2.28, 1.53) | |||

| Gender1 | .01 | 5.30 | .00 | .002 | (−10.44, 10.46) | |||

| Complex Trauma | .56 | 1.78 | .02 | .32 | (−2.94, 4.07) | |||

| 2 | (Constant) | −46.39*** | 11.82 | −3.93 | (−69.70, −23.08) | .22*** | .22*** | |

| Age (yrs) | .73 | .88 | .06 | .83 | (−1.00, 2.45) | |||

| Gender1 | .38 | 4.80 | .01 | .08 | (−9.07, 9.83) | |||

| Complex Trauma | 1.00 | 1.65 | .04 | .61 | (−2.30, 4.26) | |||

| Treatment Condition2 | −36.91*** | 5.60 | −.50 | −6.60 | (−47.94, −25.87) | |||

| Length of Stay in Tx | −.41** | .16 | −.21 | −2.64 | (−.72, −.11) | |||

| Crisis Response (Few)3 | 8.35 | 6.37 | .10 | 1.31 | (−4.21, 20.89) | |||

| Crisis Response (Many)3 | 25.63*** | 5.70 | .35 | 4.50 | (14.40, 36.85) | |||

| 3 | (Constant) | −28.71 | 14.63 | −1.96 | (−57.57, .14) | .30** | .08** | |

| Age (yrs) | .79 | .86 | .06 | .92 | (−.91, 2.48) | |||

| Gender1 | 5.72 | 8.82 | .08 | .65 | (−11.68, 23.13) | |||

| Complex Trauma (CT) | 2.46 | 3.27 | .10 | .75 | (−3.99, 8.90) | |||

| Treatment Condition2 | −41.42*** | 7.23 | −.57 | −5.73 | (−55.68, −27.16) | |||

| Length of Stay in Tx | −1.04*** | .23 | −.53 | −4.75 | (−1.47, −.61) | |||

| Crisis Response (Few)3 | 11.25 | 7.80 | .129 | 1.44 | (−4.13, 26.63) | |||

| Crisis Response (Many)3 | 35.26*** | 7.50 | .48 | 4.71 | (20.48, 50.04) | |||

| Gender1 X Tx Condition2 | 5.57 | 11.10 | .06 | .50 | (−16.33, 27.48) | |||

| Gender1 X Length of Stay | 1.17*** | .30 | .42 | 3.86 | (.58, 1.78) | |||

| Gender1 X Few CR3 | .57 | 13.58 | .00 | .04 | (−26.21, 27.35) | |||

| Gender1 X Many CR3 | −18.18 | 11.33 | −.20 | −1.60 | (−40.53, 4.20) | |||

| CT X Tx Condition2 | −1.60 | 3.91 | −.05 | −.41 | (−9.31, 6.13) | |||

| CT X Length of Stay | .04 | .11 | .03 | .35 | (−.18, .26) | |||

| CT X Few CR3 | −.85 | 4.45 | −.02 | −.20 | (−9.61, 7.92) | |||

| CT X Many CR3 | .50 | 3.83 | .01 | .13 | (−7.04, 8.05) | |||

* p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Reference groups: 1 males, 2 traditional care, 3no crisis response

The second model included treatment factors: treatment condition, length of stay in treatment, and crisis response. The second model explained 22.4% of the variance and was statistically significant (R2Δ = 0.223; F Δ (4, 198) = 14.19, p = .000). There were three statistically significant main effects within the second model: treatment condition (βTIC = −0.50, t = −6.80, p = 0.00, CI: −47.94, −25.87), length of stay in treatment (βweeks = −0.21, t = −2.64, p = 0.01, CI: −0.72, −.11), crisis response (βManyCR = 0.35, t = 4.50, p = 0.00, CI: 14.40, 36.85). These results indicated that youths who received trauma-informed PRT compared to traditional PRT experienced a 36.91-point greater decrease in their CAFAS scores from admission to discharge controlling for all other variables. Additionally, for each additional week a youth spent in treatment there was an associated 0.41-point additional decrease in the CAFAS scores from admission to discharge controlling for all other variables. Conversely, compared to youth with no crisis response incidents, youth scores with many incidents (6 or more) scored were 25.63 higher on average, indicating less change on their CAFAS scores between admission and discharge controlling for all other variables. That is, youths with no incidents experienced greater levels of improvement in functional impairment compared to youths with six or more incidents.

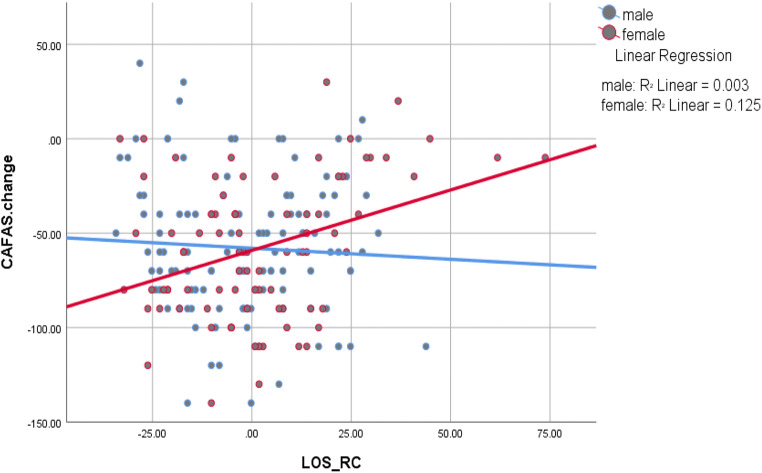

In the third model the interaction between youth gender and complex trauma and treatment factors on treatment outcomes (i.e., change in functional impairment) were examined. The final model explained an additional 7.8% of the variance for a total of 30.2% shared variance and was statistically significant (R2 = 0.302; R2Δ = 0.078; F Δ (8, 190) = 2.65, p = .01). The average length of stay in treatment for girls (M = 41.0, SD = 20.4) was higher than that for boys (M = 38.0, SD = 17.3). The interaction between gender and length of stay in treatment was statistically significant (βgender x weeks = 0.42, t = 3.86, p = 0.00, CI: 0.58, 1.77), indicating that for girls with an average length of stay (39.2 weeks) there was an expected change in CAFAS score from admission to discharge of 22.99 points. For boys with an average length of stay (39.2 weeks) there was an expected change in CAFAS scores from admission to discharge of 28.71 points. Meaning, girls experience less overall change than boys, but for each additional week spent in care, they experience greater change. Whereas for boys, the benefit of time in care plateaus (see Fig. 2 for graph of simple slopes). No other interactions were statistically significant.

Fig. 2.

Graph of simple slopes

Discussion

The results of this study were mixed. Although length of stay in treatment, treatment condition, and requiring many (six or more) crisis response interventions produced statistically significant main effects, only the interaction between gender and length of stay in treatment was statistically significant. Results indicated that youth receiving trauma-informed care (Individual TF-CBT, trauma-trained staff, and trauma-recovery group curriculum; Boel-Studt 2017) experienced greater gains in overall functioning than youth in the traditional care model. This lends support for the utilization of trauma-informed care models, which was consistent with the literature (Frensch and Cameron 2002; Knorth et al. 2008; Larzelere et al. 2001). Also consistent with the literature (Chow et al. 2014; Farmer et al. 2017) was the positive association of length of stay and improvement in functional impairment with longer participation in treatment resulting in more change, regardless of the treatment model controlling for gender.

Youth who required six or more crisis intervention responses during treatment experienced fewer gains in their overall functional impairment at discharge, demonstrating that restraint and seclusion may negatively impact a youth’s treatment outcomes (Fox 2004; Sunseri 2001, 2004) or that youth who require more crisis intervention experience fewer benefits. The continued reliance on physical restraints and seclusion within trauma-informed care models presents concerns for implementation fidelity and overall effectiveness (Brown et al. 2012; Fox 2004; Zelechoski et al. 2013). Youth age and gender were not significant predictors of treatment outcomes which countered current research indicating that younger residents (Chow et al. 2014; Conner et al., 2002) and girls were more at-risk than boys (Chow et al. 2014; Eisengart et al. 2008) for negative treatment outcomes.

The significant interaction between gender and length of stay in treatment indicated that there may be some added benefit of longer stay in TRC for girls but not boys. The results were consistent with other research (Handwerk et al. 2006) yet, it is difficult to determine the individual characteristics of the girls’ in this sample that would have supported a longer dosage of treatment.

Interestingly, using a CT measure created from youths’ abuse history did not have a significant main effect on treatment outcomes or a moderating effect on the relation between treatment conditions and treatment outcome. This indicated that experiencing one type or multiple types of abuse had no influence on the relation between treatment conditions and treatment outcome. The lack of a significant relation is intriguing, considering the prevalence of youth experiencing complex trauma in TRCs (Briggs et al. 2012; Collin-Vézina et al. 2011; Zelechoski et al. 2013) and the prevalence of CT in the current sample (57%). Per these results, the trauma-informed care model used in this sample was no more or less effective for youth considering their abuse histories, at least not when measured by the number of different types of abuse experienced. It may be that individual type, duration or frequency of abuse play a greater role in treatment response.

Empirical literature neither supports nor refutes the lack of moderating effects of gender on treatment conditions. At this time, research related to how males and females respond to TRC is inconclusive. Researchers have confirmed gender differences among youth upon admission (Collin-Vézina et al. 2011; Connor et al. 2004; Hussey and Guo 2002) and that behavior of girls and boys differ while in RTC (Hussey and Guo 2002; Maschi et al. 2008), however, there are mixed findings concerning the influence of gender on treatment outcomes. Few studies focus on examining gender influence on length of stay in treatment and crisis response interventions in RTC and the relation to treatment outcomes (Handwerk et al. 2006; Sunseri 2001, 2004)..

The interpretation of the results should be considered in light of the limitations of this study. While creation of a scale that quantified CT experiences resulted in strong reliability, it was not a comprehensive measure of CT for youth in TRC. Specifically, the scale tallied the types of abuse experienced by youth but could not capture the frequency, duration, or intensity of the abuse experience. Additionally, the use of case files meant the outcome variable was representative of only discharged youth. Youth in TRC are typically discharged when their functioning reaches a certain clinical threshold, therefore, use of both discharged and current youths may lend more robust evidence of effective treatment conditions.

Results support the participation of youth in trauma-informed models of TRC, experiencing minimal crisis response interventions, with monitored progress to insure appropriate treatment dosage. Findings yield four main implications for TRC. First, youth had greater gains in overall functioning when participating in the trauma-informed care model compared to a traditional treatment model. Future research considerations should include longitudinal or time series designs to examine the influence of treatment conditions while the youth is actively participating in treatment instead of post-discharge. Second, youths’ overall functioning improved with each additional week in treatment, indicating the need to improve the sensitivity of progress monitoring to insure youth are not prematurely discharged from treatment. Third, lack of empirical support for CT moderating a youth treatment experiences and outcomes may indicate a need for further research to that captures CT experiences considering type of abuse, frequency, timing or duration of exposure. Additionally, the lack of evidence that multiple abuse experiences impact treatment outcomes, residential care providers should consider any abuse experience as a significant treatment factor regardless of its frequency, duration, or intensity. Fourth, although the reason is unclear, girls showed fewer gains in treatment than boys during similar lengths of stay. TRC providers should consider gender as a factor impacting treatment experiences and outcomes. Further research is needed to identify specific factors underlying these observed differences.

Trauma-informed care models need further study to determine best-practice models to insure a youth’s efficient and progressive stay in treatment. Future research should explore the influence of additional interactions of treatment conditions on different treatment outcomes, such as level of care of the discharge placement. Advancing current knowledge of the impact of CT experiences on youth will inform how best to support youth who have experienced CT in residential care.

Acknowledgments

Lauren H. K. Stanley would like to thank Dr. Boel-Studt for her support and guidance during this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Authors Lauren H. K. Stanley and Shamra Boel-Studt declare they have no conflict of interests to report.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the Florida State University Institutional Review Board and followed the ethical standards applied to de-identified secondary data.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arvidson J, Kinniburgh K, Howard K, Spinazzola J, Strothers H, Evans M, Andres B, Cohen C, Blaustein ME. Treatment of complex trauma in young children: developmental and cultural considerations in application of the ARC intervention model. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2011;4(1):34–51. doi: 10.1080/19361521.2011.545046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azeem MW, Aujla A, Rammerth M, Binsfeld G, Jones RB. Effectiveness of six core strategies based on trauma informed care in reducing seclusions and restraints ata child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2011;24(1):11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates MP, Furlong MJ, Green JG. Are CAFAS subscales and item weights valid? A preliminary investigation of the child and adolescent functional assessment scale. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:682–695. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boel-Studt SM. A quasi-experimental study of trauma-informed psychiatric residential treatment for children and adolescents. Research on Social Work Practice. 2017;27:273–282. doi: 10.1177/1049731515614401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KL, Caraway SJ. Home away from home: factors associated with current functioning in children living in a residential treatment setting. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0145213402003897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs EC, Greeson JK, Layne CM, Fairbank JA, Knoverek AM, Pynoos RS. Trauma exposure, psychosocial functioning, and treatment needs of youth in residential care: preliminary findings from the NCTSN Core data set. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2012;5(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/19361521.2012.646413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Barrett K, Ireys HT, Allen K, Pires SA, Blau G, et al. Seclusion and restraint practices in residential treatment facilities for children and youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(1):87–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Maltreatment . Indicators of child and youth well-being. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chow WY, Mettrick JE, Stephan SH, Von Waldner CA. Youth in group home care: youth characteristics and predictors of later functioning. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2014;41:503–519. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vézina D, Coleman K, Milne L, Sell J, Daigneault I. Trauma experiences, maltreatment-related impairments, and resilience among child welfare youth in residential care. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2011;9:577–589. doi: 10.1007/s11469-011-9323-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor DF, Doerfler LA, Toscano PF, Volungis AM, Steingard RJ. Characteristics of children and adolescents admitted to a residential treatment center. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13:497–510. doi: 10.1023/B:JCFS.0000044730.66750.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, et al. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:390–398. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisengart J, Martinovich Z, Lyons JS. Discharge due to running away from residential treatment: youth and setting effects. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2008;24:327–343. doi: 10.1080/08865710802174418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esaki N, Benamati J, Yanosy S, Middleton J, Hopson L, Hummer V, Bloom S. The sanctuary model: theoretical framework. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services. 2013;94(2):87–95. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.4287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbeck H, Kohlmann CW, Lohaus A. Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. Journal of Individual Differences. 2007;28(1):18–26. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001.28.1.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Seifert H, Wagner HR, Burns BJ, Murray M. Does model matter? Examining change across time for youth in group homes. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2017;25(2):119–128. doi: 10.1177/1063426616630520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 4. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, L. (2004). The impact of restraint on sexually abused children and youth. Residential Group Care Quarterly, 4(3), 1–5.

- Frensch KM, Cameron G. Treatment of choice or a last resort? A review of residential mental health placements for children and youth. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2002;31:307–339. doi: 10.1023/A:1016826627406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JK, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, Layne CM, Ake GS, Ko SJ, et al. Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare. 2011;90(6):91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerk ML, Clopton K, Huefner JC, Smith GL, Hoff KE, Lucas CP. Gender differences in adolescents in residential treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76:312–324. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Cunningham M. Outcomes of children with emotional disturbance in residential treatment for educational purposes. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1992;1(2):129–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01321281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey DL, Guo S. Profile characteristics and behavioral change trajectories of young residential children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2002;11:401–410. doi: 10.1023/A:1020927223517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner, V. C., & Buttell, F. P. (2018). Investigating the usefulness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescent residential care. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 1–16. 10.1080/23761407.2018.1474155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kinniburgh KJ, Blaustein M, Spinazzola J, Van der Kolk BA. Attachment, self-regulation, and competency: a comprehensive intervention framework for children with complex trauma. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:424–430. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knorth EJ, Harder AT, Zandberg T, Kendrick AJ. Under one roof: a review and selective meta-analysis on the outcomes of residential child and youth care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:123–140. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larzelere RE, Dinges K, Schmidt MD, Spellman DF, Criste TR, Connell P. Outcomes of residential treatment: a study of the adolescent clients of Girls and Boys Town. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2001;30:175–185. doi: 10.1023/A:1012236824230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DM, Quinn J. Complex trauma in children and adolescents: evidence-based practice in clinical settings. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69:497–509. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran TA, Mulvey EP, Schubert CA, Fagan J, Piquero AR, Losoya SH. Estimating a dose-response relationship between length of stay and future recidivism in serious juvenile offenders. Criminology. 2009;47:699–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T, Morgen K, Bradley C, Hatcher SS. Exploring gender differences on internalizing and externalizing behavior among maltreated youth: implications for social work action. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2008;25:531–547. doi: 10.1007/s10560-008-0139-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muskett C. Trauma-informed care in inpatient mental health settings: a review of the literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2014;23(1):51–59. doi: 10.1111/inm.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SI, Strzelecki SC. Inpatient psychiatric treatment of children and adolescents: a review of outcome studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:847–853. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips EL, Phillips EA, Fixsen DL, Wolf MM. The teaching-family handbook. 2. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:201–269. doi: 10.1002/1097-0355(200101/04)22:1<201::AID-IMHJ8>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola J, Ford JD, Zucker M, van der Kolk BA, Silva S, Smith SF, Blaustein M. Survey evaluates: complex trauma exposure, outcome, and intervention among children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:433–439. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunseri, P. A. (2001). The prediction of unplanned discharge from residential treatment. In Child and youth care forum (Vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 283-303). Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers.

- Sunseri PA. Family functioning and residential treatment outcomes. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2004;22(1):33–53. doi: 10.1300/J007v22n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration of Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2018). The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2017 Estimates as of August 10, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport25.pdf.

- Van der Kolk BA. Developmental trauma disorder: toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:401–408. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner DA, Schneider A, Lyons JS. Evidence-based treatments for trauma among culturally diverse foster care youth: treatment retention and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JK, Del Valle JF, Holmes L, editors. Therapeutic residential care with children and youth: Developing evidence-based international practice. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Winokur MA, Crawford GA, Longobardi RC, Valentine DP. Matched comparison of children in kinship care and foster care on child welfare outcomes. Families in Society. 2008;89:338–346. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.3759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zelechoski AD, Sharma R, Beserra K, Miguel JL, DeMarco M, Spinazzola J. Traumatized youth in residential treatment settings: prevalence, clinical presentation, treatment, and policy implications. Journal of Family Violence. 2013;28:639–652. doi: 10.1007/s10896-013-9534-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]