Abstract

Objectives

To describe the percentile distribution of multimorbidity across age by sex, race and ethnicity, and to demonstrate the utility of multimorbidity percentiles to predict mortality.

Design

Population-based descriptive study and cohort study.

Setting

Olmsted County, Minnesota (USA).

Participants

We used the medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP; http://www.rochesterproject.org) to identify all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota who reached one or more birthdays between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014 (10 years).

Methods

For each person, we obtained the count of chronic conditions (out of 20 conditions) present on each birthday by extracting all of the diagnostic codes received in the 5 years before the index birthday from the electronic indexes of the REP. To compare each person’s count to peers of same age, the counts were transformed into percentiles of the total population and displayed graphically across age by sex, race and ethnicity. In addition, quintiles 1, 2, 4 and 5 were compared with quintile 3 (reference) to predict the risk of death at 1 year, 5 years and through end of follow-up using time-to-event analyses. Follow-up was passive using the REP.

Results

We identified 238 010 persons who experienced a total of 1 458 094 birthdays during the study period (median of 6 birthdays per person; IQR 3–10). The percentiles of multimorbidity across age did not vary noticeably by sex, race or ethnicity. In general, there was an increased risk of mortality at 1 and 5 years for quintiles 4 and 5 of multimorbidity. The risk of mortality for quintile 5 was greater for younger age groups and for women.

Conclusions

The assignment of multimorbidity percentiles to persons in a population may be a simple and intuitive tool to assess relative health status, and to predict short-term mortality, especially in younger persons and in women.

Keywords: epidemiology, geriatric medicine, statistics & research methods, general medicine (see internal medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our descriptive study of percentiles of multimorbidity across age, and our cohort study of the association between quintiles of multimorbidity and mortality are population based and use data from a comprehensive medical records-linkage system.

Almost all persons in the population gave general authorisation to use their medical records for research and were included in the study (approximately 95%). Persons were included regardless of socioeconomic status, insurance status and healthcare delivery setting.

The persons were included at multiple birthday points (at different ages) to develop the percentile scores, and we made the assumption that there were no systematic changes in the patterns of multimorbidity across calendar year (no calendar-year time trends over the 10-year window of birthdays).

When detecting chronic conditions using diagnostic codes from medical records, we may have undercounted or misclassified certain conditions that did not receive adequate coding as part of routine medical care.

We did not consider the effect of severity or medical treatment of specific conditions in our prediction of mortality at 1 year and 5 years of follow-up.

Introduction

The degree of accumulation of multimorbidity (number of chronic conditions as compared with peers of the same age and sex) has been proposed as a clinical marker of acceleration of the ageing processes.1–4 We and others have previously shown that the number of chronic conditions increases dramatically with older age, and may be influenced by factors such as sex, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status.2 5–8 Thus, persons who have accumulated more chronic conditions than their peers may be experiencing accelerated ageing. Indeed, multimorbidity mirrors a global susceptibility and loss of resilience, which are both hallmarks of ageing.4

For example, in a study of women who underwent bilateral oophorectomy before the age of natural menopause, we previously used the rate of accumulation of multimorbidity as a clinical measure of the rate of ageing at the cellular, tissue, organ and system levels.9–11 The correspondence between the clinical measure of multimorbidity and the biological changes related to ageing (biomarkers of ageing) has not been tested directly, but was confirmed indirectly by the finding that women who underwent bilateral oophorectomy before the age of natural menopause also experienced accelerated ageing, measured using a defined set of DNA methylation levels across multiple genomic regions.12 13 Because DNA methylation is one of the best known epigenetic mechanisms and is strongly correlated with chronologic age, this ageing biomarker has been named an ‘epigenetic clock’.13

If rapid accumulation of chronic conditions is a marker of accelerated ageing, it is necessary to first understand the normal accumulation of chronic conditions across the lifespan. Unfortunately, there is no consensus about how many conditions or clusters of conditions, or what severity of conditions, are needed to define accelerated ageing and to separate it from slower ageing (successful ageing) or from typical ageing.9 Variation in the types of conditions included in studies of multimorbidity makes it difficult to compare study results from different research groups. In addition, there is a lack of age-specific, sex-specific, race-specific and ethnicity-specific data regarding the typical accumulation of chronic conditions in the general population (normative data). Barnett et al have previously reported such data for persons in the Scottish population, but similar data are rare in the USA because there are no comprehensive, clinical records-based data sets across all ages and for all regions of the country.5 8 14 15 The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) comprehensive medical records-linkage system provides a unique research infrastructure to fill this gap. Normative data in a general US population would be useful for identifying persons who are accumulating chronic conditions at a faster or slower rate than their peers. Such measures may then be used to identify persons at high risk for adverse outcomes related to ageing (eg, hospital admission, nursing home placement or early mortality).

To address these research gaps, we first calculated normative values for multimorbidity across age, sex, race and ethnicity in the population of Olmsted County, Minnesota (USA) using a set of 20 chronic conditions. Second, we determined whether a person’s percentile rank was significantly associated with short-term mortality. We use the term normative to indicate what is usual in the general population; however, we are not suggesting that what happens in the population represents ideal circumstances.16 17

Methods

Study population

We used the medical records-linkage system of the REP to identify all persons who lived in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA at any time between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014 (10 years). To be included, persons were required to have reached at least one birthday while a resident of the county within the study time frame. Therefore, we excluded persons who died or moved out of Olmsted County before reaching a birthday. We included all birthdays from 0 (birth) to 110 years. Persons were included in the analyses multiple times if they resided in the county at several birthdates. However, we excluded persons who did not have at least one medical record with authorisation to be included in research, as per Minnesota legal requirements.18

Persons in the sample were stratified into birthday cohorts at the single year level (eg, age 41, 42 and 43), and regardless of the calendar year in which the birthday occurred. Each birthday cohort was followed from the date of the birthday to 31 December 2017, through death, or through the last medical contact captured by the REP. Mortality was assessed using the electronic information from the REP indexes, which include death information from state and national sources.18

Definition of 20 chronic conditions

We studied the 20 chronic conditions recommended by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to define multimorbidity (see online supplemental table 1). These conditions were selected by the DHHS because they are chronic, prevalent and ‘potentially amenable to public health or clinical interventions or both’.19 However, we modified the set of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes used to define cancer by excluding non-melanoma skin cancer because it is relatively common in the general population but has a benign prognosis. The REP links and archives all of the billing codes generated by the participating healthcare institutions at every healthcare visit (inpatient, outpatient, emergency room or other). To qualify as having a condition at the birthdate, a person was required to have received two or more codes separated by more than 30 days from among the list of codes defining a condition. Each birthday was treated as an index date, and prevalent conditions at a given age were derived from the diagnostic codes for each person in the 5 years before the index date (moving 5-year window). Each person was assigned a count for the number of conditions present on the index date (multimorbidity score), and the score was modelled and transformed into a percentile rank of the distribution of scores in the overall geographically defined population.

bmjopen-2020-042633supp001.pdf (224.6KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient involvement in the study.

Statistical analyses

Quantile regression was used to model the multimorbidity scores across age. Because the multimorbidity score is an integer count with values between 0 and 20, we used methods for calculating quantiles for counts as described elsewhere.20 This modelling involves a step of adding a random amount of jitter from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 to each observed multimorbidity score. We performed 20 replicates of this jitter process, and averaged across the modelled quantiles. Quantile regression was modelled using the gcrq function (growth charts regression quantiles) available as part of the quantregGrowth package in R. Because our study focuses on modelling quantiles through age 85 years, quantile regression models included birthdays through age 95 to stabilise the older age estimation.

Using these methods, the multimorbidity score of each person on a given birthday was effectively transformed into a percentile (quantile) rank of the distribution of scores in the overall geographically defined population. We studied the percentile distribution of the number of conditions across age in men and women separately and combined. We also studied differences by race (Whites, Blacks, Asians and other) and by ethnic group (Hispanics vs non-Hispanics), as defined by the US Census Bureau.

To investigate the clinical utility of the percentile ranks to predict outcomes in specific age cohorts, we studied the risk of death at 1 year, 5 years and through last follow-up (31 December 2017) across quintiles of the score. Quintile 3 was considered the reference. For quintiles 1, 2, 4 and 5, we computed an HR and a 95% CI using Cox proportional hazards models. All models were adjusted for sex, race, ethnicity and calendar year of birthday (when applicable). The mortality at 1 year and 5 years after the index birthdates were determined from the Kaplan-Meier curves associated with the Cox proportional hazards models. We conducted analyses for men and women separately and combined. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute) and R V.3.6.1, and tests of statistical significance were conducted at the two-tailed alpha level of 0.05.

Results

Study population

From a total population of 262 064 persons who ever resided in Olmsted County between 2005 and 2014, we excluded 12 624 (4.8%) persons because they did not reach at least one birthday during the 10-year period. Of the remaining 249 440 persons, we excluded 11 430 (4.6%) persons because they did not have any medical record with research authorisation, resulting in 238 010 persons included in the analyses. Persons were included more than once if they reached multiple birthdays during the 10-year period. Indeed, the total number of birthdays was 1 458 094, and the median number of birthdays was 6 per person (IQR 3–10). For quantile regression models, we included the 1 456 052 birthdays at ages ≤95 years (among 237 791 unique persons). This age restriction ensured that quantile regression models were firmly anchored at older ages for the estimation of quantiles through age 85 years. Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics in eight birthday cohorts corresponding to 8 decades of age. Table 1 also shows the depth of medical record information available in the records-linkage system of the REP before the index birthday. The median depth of information was 5 years for each of the eight birthday cohorts.

Table 1.

Descriptive information for decade birthday cohorts from ages 10 years to 80 years

| Characteristic | Birthday age cohort, N (%) | |||||||

| Age 10 years N=18 589 |

Age 20 years N=20 468 |

Age 30 years N=22 769 |

Age 40 years N=17 733 |

Age 50 years N=21 151 |

Age 60 years N=15 218 |

Age 70 years N=9420 |

Age 80 years N=5876 |

|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Women | 9036 (48.6) | 10 711 (52.3) | 12 097 (53.1) | 9076 (51.2) | 11 034 (52.2) | 7943 (52.2) | 4981 (52.9) | 3298 (56.1) |

| Men | 9553 (51.4) | 9757 (47.7) | 10 672 (46.9) | 8657 (48.8) | 10 117 (47.8) | 7275 (47.8) | 4439 (47.1) | 2578 (43.9) |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 13 787 (74.2) | 16 133 (78.8) | 17 593 (77.3) | 14 143 (79.8) | 18 818 (89.0) | 13 778 (90.5) | 8668 (92.0) | 5555 (94.5) |

| Black | 1764 (9.5) | 1707 (8.3) | 1436 (6.3) | 994 (5.6) | 667 (3.2) | 323 (2.1) | 190 (2.0) | 79 (1.3) |

| Asian | 1187 (6.4) | 985 (4.8) | 1488 (6.5) | 1188 (6.7) | 715 (3.4) | 543 (3.6) | 270 (2.9) | 123 (2.1) |

| Other/mixed | 1526 (8.2) | 1196 (5.8) | 1451 (6.4) | 1032 (5.8) | 697 (3.3) | 413 (2.7) | 223 (2.4) | 99 (1.7) |

| Unknown/refused | 325 (1.7) | 447 (2.2) | 801 (3.5) | 376 (2.1) | 254 (1.2) | 161 (1.1) | 69 (0.7) | 20 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 17 051 (91.7) | 19 097 (93.3) | 21 082 (92.6) | 16 605 (93.6) | 20 236 (95.7) | 14 656 (96.3) | 9172 (97.4) | 5781 (98.4) |

| Hispanic | 1538 (8.3) | 1371 (6.7) | 1687 (7.4) | 1128 (6.4) | 915 (4.3) | 562 (3.7) | 248 (2.6) | 95 (1.6) |

| Calendar year period | ||||||||

| 2005–2009 | 8905 (47.9) | 10 596 (51.8) | 10 874 (47.8) | 8956 (50.5) | 10 647 (50.3) | 6702 (44.0) | 4261 (45.2) | 2813 (47.9) |

| 2010–2014 | 9684 (52.1) | 9872 (48.2) | 11 895 (52.2) | 8777 (49.5) | 10 504 (49.7) | 8516 (56.0) | 5159 (54.8) | 3063 (52.1) |

| Depth of medical record information | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (3, 5) | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (5, 5) | 5 (5, 5) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.55 (1.12) | 4.36 (1.36) | 3.99 (1.50) | 4.45 (1.21) | 4.64 (1.00) | 4.72 (0.90) | 4.76 (0.84) | 4.82 (0.73) |

| Chronic conditions | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 14 (0.1) | 82 (0.4) | 428 (1.9) | 1176 (6.6) | 3456 (16.3) | 5062 (33.3) | 4955 (52.6) | 4011 (68.3) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1 (<0.1) | 4 (<0.1) | 9 (<0.1) | 21 (0.1) | 73 (0.3) | 168 (1.1) | 276 (2.9) | 448 (7.6) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 (<0.1) | 3 (<0.1) | 16 (0.1) | 78 (0.4) | 426 (2.0) | 1071 (7.0) | 1595 (16.9) | 1632 (27.8) |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 58 (0.3) | 289 (1.4) | 450 (2.0) | 554 (3.1) | 890 (4.2) | 1120 (7.4) | 1496 (15.9) | 1814 (30.9) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 16 (0.1) | 99 (0.5) | 570 (2.5) | 1792 (10.1) | 4714 (22.3) | 6485 (42.6) | 5553 (58.9) | 3740 (63.6) |

| Stroke | 6 (<0.1) | 12 (0.1) | 24 (0.1) | 41 (0.2) | 119 (0.6) | 207 (1.4) | 392 (4.2) | 535 (9.1) |

| Arthritis | 16 (0.1) | 83 (0.4) | 189 (0.8) | 557 (3.1) | 1845 (8.7) | 2905 (19.1) | 2700 (28.7) | 2226 (37.9) |

| Asthma | 1561 (8.4) | 1656 (8.1) | 989 (4.3) | 854 (4.8) | 1024 (4.8) | 747 (4.9) | 458 (4.9) | 300 (5.1) |

| Autism | 82 (0.4) | 34 (0.2) | 2 (<0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (<0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cancer | 26 (0.1) | 59 (0.3) | 282 (1.2) | 329 (1.9) | 782 (3.7) | 1142 (7.5) | 1487 (15.8) | 1275 (21.7) |

| CKD | 60 (0.3) | 48 (0.2) | 96 (0.4) | 162 (0.9) | 258 (1.2) | 393 (2.6) | 522 (5.5) | 619 (10.5) |

| COPD | 186 (1.0) | 169 (0.8) | 170 (0.7) | 248 (1.4) | 465 (2.2) | 551 (3.6) | 670 (7.1) | 679 (11.6) |

| Dementia | 30 (0.2) | 73 (0.4) | 46 (0.2) | 46 (0.3) | 124 (0.6) | 103 (0.7) | 145 (1.5) | 376 (6.4) |

| Depressive disorders | 91 (0.5) | 2575 (12.6) | 2782 (12.2) | 2637 (14.9) | 3163 (15.0) | 2149 (14.1) | 935 (9.9) | 730 (12.4) |

| Diabetes | 51 (0.3) | 137 (0.7) | 442 (1.9) | 855 (4.8) | 2070 (9.8) | 3110 (20.4) | 2926 (31.1) | 2030 (34.5) |

| Hepatitis | 8 (<0.1) | 36 (0.2) | 88 (0.4) | 137 (0.8) | 178 (0.8) | 142 (0.9) | 57 (0.6) | 32 (0.5) |

| HIV infection | 3 (<0.1) | 4 (<0.1) | 15 (0.1) | 24 (0.1) | 25 (0.1) | 5 (<0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Osteoporosis | 0 (0.0) | 5 (<0.1) | 15 (0.1) | 49 (0.3) | 132 (0.6) | 458 (3.0) | 755 (8.0) | 907 (15.4) |

| Schizophrenia and psychoses | 2 (<0.1) | 61 (0.3) | 134 (0.6) | 136 (0.8) | 166 (0.8) | 118 (0.8) | 81 (0.9) | 80 (1.4) |

| Substance abuse disorders | 6 (<0.1) | 797 (3.9) | 777 (3.4) | 605 (3.4) | 812 (3.8) | 384 (2.5) | 164 (1.7) | 75 (1.3) |

| No of chronic conditions | ||||||||

| None | 16 512 (88.8) | 15 549 (76.0) | 17 424 (76.5) | 11 321 (63.8) | 10 490 (49.6) | 4414 (29.0) | 1498 (15.9) | 541 (9.2) |

| 1 | 1951 (10.5) | 3857 (18.8) | 3844 (16.9) | 4037 (22.8) | 5298 (25.0) | 3671 (24.1) | 1382 (14.7) | 529 (9.0) |

| 2 | 115 (0.6) | 862 (4.2) | 1044 (4.6) | 1457 (8.2) | 2809 (13.3) | 2859 (18.8) | 1810 (19.2) | 763 (13.0) |

| 3 | 9 (<0.1) | 163 (0.8) | 313 (1.4) | 550 (3.1) | 1371 (6.5) | 2091 (13.7) | 1792 (19.0) | 1028 (17.5) |

| 4 | 1 (<0.1) | 31 (0.2) | 95 (0.4) | 220 (1.2) | 656 (3.1) | 1144 (7.5) | 1377 (14.6) | 1023 (17.4) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (<0.1) | 30 (0.1) | 97 (0.5) | 298 (1.4) | 571 (3.8) | 778 (8.3) | 836 (14.2) |

| ≥6 | 1 (<0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 19 (0.1) | 51 (0.3) | 229 (1.1) | 468 (3.1) | 783 (8.3) | 1156 (19.7) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles); SD, standard deviation.

Validity of the multimorbidity score

We investigated whether the use of the 20 chronic conditions recommended by the DHHS to define the percentile ranking of multimorbidity was valid as compared with the use of a broader list. In particular, we compared the percentile ranking based on the 20 DHHS conditions to the percentile ranking based on a more extensive list of 190 conditions defined in the Clinical Classification Software (CCS) and with at least one diagnosis code flagged by the CCS as chronic.21 22 Of the 283 CCS categories that include all of the 15 072 ICD-9 codes, we identified 190 categories with at least 1 code flagged as chronic. For both the DHHS and the CCS definitions, we required two or more codes for the same condition separated by more than 30 days. For the CCS categories, both codes within a category had to be flagged as chronic to meet the inclusion criteria. Both definitions were based on the diagnostic codes archived in the electronic indexes of the REP within the 5-year window before the index birthday. For this validation study, we included the subset of birthdays at ages ≤95 years to model the percentile distributions of both the DHHS score and the CCS score. The modelling included 237 791 persons who contributed a total of 1 456 052 birthdays. Although the crude multimorbidity scores (simple condition count) were highly dependent on the number of conditions included, the percentile scales had substantial intraclass correlation at ages 40 years and older, and almost perfect intraclass correlation at age 60 years and older (see online supplemental table 2).23 24

Percentile ranks of multimorbidity

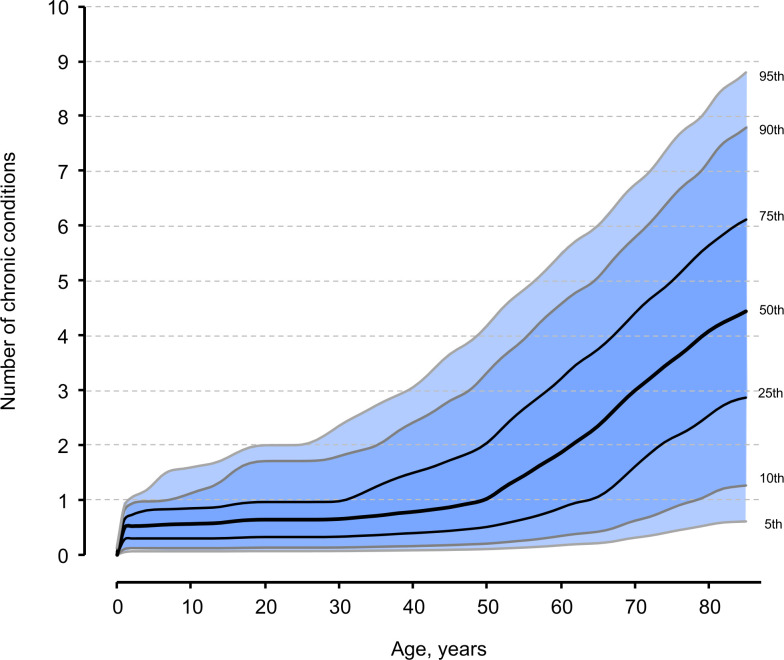

Table 2 shows the distribution of the number of conditions by age and sex in four racial groups and by ethnicity. Online supplemental figures 1–4 show the 50th, 75th, 90th and 95th percentiles of multimorbidity by sex (online supplemental figure 1), by race (online supplemental figure 2), by ethnicity (online supplemental figure 3), and by calendar year quinquennium (online supplemental figure 4). The accumulation of multimorbidity was similar in men and women through approximately age 70, but was somewhat greater in men thereafter. Blacks had a somewhat higher accumulation of multimorbidity compared with other races between the ages of 40 and 60, in particular, as compared with Asians (see online supplemental figure 2, panels C and D). Similarly, non-Hispanics had a somewhat higher accumulation of multimorbidity than Hispanics. Finally, the most recent quinquennium (2010–2014) had a somewhat higher accumulation of multimorbidity than the earlier quinquennium (2005–2009) but only at ages 75 years and older. Because the differences by sex, race, ethnicity and calendar year were relatively small (ie, less than the accumulation of one additional condition), we present the percentile distribution of multimorbidity in the entire population as a single figure (figure 1).

Table 2.

Age and sex distribution of the number of chronic conditions in racial and ethnic groups in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA (2005–2014)

| Birthday cohort, years |

Men, N (%) | Women, N (%) | ||||||||||

| Total | No of chronic conditions | Total | No of chronic conditions | |||||||||

| 0 | ≥1 | ≥2 | ≥3 | ≥4 | 0 | ≥1 | ≥2 | ≥3 | ≥4 | |||

| All races | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 9553 | 8311 (87.0) | 1242 (13.0) | 77 (0.8) | 6 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 9036 | 8201 (90.8) | 835 (9.2) | 49 (0.5) | 5 (0.1) | 2 (<0.1) |

| 20 | 9757 | 7582 (77.7) | 2175 (22.3) | 434 (4.4) | 70 (0.7) | 14 (0.1) | 10 711 | 7967 (74.4) | 2744 (25.6) | 628 (5.9) | 130 (1.2) | 23 (0.2) |

| 30 | 10 672 | 8774 (82.2) | 1898 (17.8) | 546 (5.1) | 181 (1.7) | 63 (0.6) | 12 097 | 8650 (71.5) | 3447 (28.5) | 955 (7.9) | 276 (2.3) | 81 (0.7) |

| 40 | 8657 | 5777 (66.7) | 2880 (33.3) | 1077 (12.4) | 448 (5.2) | 192 (2.2) | 9076 | 5544 (61.1) | 3532 (38.9) | 1298 (14.3) | 470 (5.2) | 176 (1.9) |

| 50 | 10 117 | 5078 (50.2) | 5039 (49.8) | 2646 (26.2) | 1280 (12.7) | 569 (5.6) | 11 034 | 5412 (49.0) | 5622 (51.0) | 2717 (24.6) | 1274 (11.5) | 614 (5.6) |

| 60 | 7275 | 2131 (29.3) | 5144 (70.7) | 3498 (48.1) | 2139 (29.4) | 1061 (14.6) | 7943 | 2283 (28.7) | 5660 (71.3) | 3635 (45.8) | 2135 (26.9) | 1122 (14.1) |

| 70 | 4439 | 744 (16.8) | 3695 (83.2) | 3079 (69.4) | 2295 (51.7) | 1472 (33.2) | 4981 | 754 (15.1) | 4227 (84.9) | 3461 (69.5) | 2435 (48.9) | 1466 (29.4) |

| 80 | 2578 | 222 (8.6) | 2356 (91.4) | 2145 (83.2) | 1859 (72.1) | 1428 (55.4) | 3298 | 319 (9.7) | 2979 (90.3) | 2661 (80.7) | 2184 (66.2) | 1587 (48.1) |

| White race | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 7092 | 6171 (87.0) | 921 (13.0) | 62 (0.9) | 4 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6695 | 6091 (91.0) | 604 (9.0) | 34 (0.5) | 4 (0.1) | 2 (<0.1) |

| 20 | 7636 | 5750 (75.3) | 1886 (24.7) | 377 (4.9) | 57 (0.7) | 11 (0.1) | 8497 | 6135 (72.2) | 2362 (27.8) | 542 (6.4) | 112 (1.3) | 19 (0.2) |

| 30 | 8162 | 6585 (80.7) | 1577 (19.3) | 449 (5.5) | 146 (1.8) | 48 (0.6) | 9431 | 6494 (68.9) | 2937 (31.1) | 813 (8.6) | 239 (2.5) | 67 (0.7) |

| 40 | 6792 | 4418 (65.0) | 2374 (35.0) | 889 (13.1) | 367 (5.4) | 160 (2.4) | 7351 | 4333 (58.9) | 3018 (41.1) | 1098 (14.9) | 395 (5.4) | 147 (2.0) |

| 50 | 8939 | 4400 (49.2) | 4539 (50.8) | 2361 (26.4) | 1141 (12.8) | 495 (5.5) | 9879 | 4794 (48.5) | 5085 (51.5) | 2440 (24.7) | 1116 (11.3) | 525 (5.3) |

| 60 | 6604 | 1877 (28.4) | 4727 (71.6) | 3203 (48.5) | 1956 (29.6) | 968 (14.7) | 7174 | 1988 (27.7) | 5186 (72.3) | 3308 (46.1) | 1929 (26.9) | 1006 (14.0) |

| 70 | 4088 | 631 (15.4) | 3457 (84.6) | 2890 (70.7) | 2167 (53.0) | 1394 (34.1) | 4580 | 652 (14.2) | 3928 (85.8) | 3228 (70.5) | 2274 (49.7) | 1358 (29.7) |

| 80 | 2439 | 199 (8.2) | 2240 (91.8) | 2044 (83.8) | 1776 (72.8) | 1366 (56.0) | 3116 | 281 (9.0) | 2835 (91.0) | 2537 (81.4) | 2078 (66.7) | 1515 (48.6) |

| Black race | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 899 | 760 (84.5) | 139 (15.5) | 7 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 865 | 751 (86.8) | 114 (13.2) | 8 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 20 | 857 | 743 (86.7) | 114 (13.3) | 23 (2.7) | 7 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 850 | 714 (84.0) | 136 (16.0) | 31 (3.6) | 8 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) |

| 30 | 715 | 585 (81.8) | 130 (18.2) | 44 (6.2) | 18 (2.5) | 9 (1.3) | 721 | 562 (77.9) | 159 (22.1) | 50 (6.9) | 13 (1.8) | 3 (0.4) |

| 40 | 518 | 361 (69.7) | 157 (30.3) | 68 (13.1) | 30 (5.8) | 15 (2.9) | 476 | 302 (63.4) | 174 (36.6) | 76 (16.0) | 28 (5.9) | 13 (2.7) |

| 50 | 351 | 191 (54.4) | 160 (45.6) | 101 (28.8) | 57 (16.2) | 33 (9.4) | 316 | 131 (41.5) | 185 (58.5) | 102 (32.3) | 62 (19.6) | 43 (13.6) |

| 60 | 157 | 49 (31.2) | 108 (68.8) | 87 (55.4) | 56 (35.7) | 29 (18.5) | 166 | 51 (30.7) | 115 (69.3) | 86 (51.8) | 59 (35.5) | 37 (22.3) |

| 70 | 91 | 24 (26.4) | 67 (73.6) | 58 (63.7) | 41 (45.1) | 26 (28.6) | 99 | 25 (25.3) | 74 (74.7) | 54 (54.5) | 36 (36.4) | 25 (25.3) |

| 80 | 34 | 7 (20.6) | 27 (79.4) | 24 (70.6) | 20 (58.8) | 15 (44.1) | 45 | 10 (22.2) | 35 (77.8) | 29 (64.4) | 25 (55.6) | 8 (17.8) |

| Asian race | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 597 | 520 (87.1) | 77 (12.9) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 590 | 552 (93.6) | 38 (6.4) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 20 | 460 | 396 (86.1) | 64 (13.9) | 8 (1.7) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 525 | 446 (85.0) | 79 (15.0) | 21 (4.0) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) |

| 30 | 632 | 559 (88.4) | 73 (11.6) | 20 (3.2) | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 856 | 729 (85.2) | 127 (14.8) | 28 (3.3) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) |

| 40 | 574 | 422 (73.5) | 152 (26.5) | 45 (7.8) | 19 (3.3) | 4 (0.7) | 614 | 471 (76.7) | 143 (23.3) | 37 (6.0) | 10 (1.6) | 4 (0.7) |

| 50 | 340 | 188 (55.3) | 152 (44.7) | 85 (25.0) | 36 (10.6) | 18 (5.3) | 375 | 219 (58.4) | 156 (41.6) | 73 (19.5) | 34 (9.1) | 15 (4.0) |

| 60 | 228 | 78 (34.2) | 150 (65.8) | 100 (43.9) | 65 (28.5) | 33 (14.5) | 315 | 110 (34.9) | 205 (65.1) | 134 (42.5) | 83 (26.3) | 39 (12.4) |

| 70 | 114 | 40 (35.1) | 74 (64.9) | 58 (50.9) | 37 (32.5) | 20 (17.5) | 156 | 34 (21.8) | 122 (78.2) | 96 (61.5) | 66 (42.3) | 40 (25.6) |

| 80 | 51 | 6 (11.8) | 45 (88.2) | 38 (74.5) | 32 (62.7) | 23 (45.1) | 72 | 7 (9.7) | 65 (90.3) | 60 (83.3) | 51 (70.8) | 41 (56.9) |

| Other race | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 804 | 706 (87.8) | 98 (12.2) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 722 | 646 (89.5) | 76 (10.5) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 20 | 564 | 473 (83.9) | 91 (16.1) | 24 (4.3) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | 632 | 486 (76.9) | 146 (23.1) | 30 (4.7) | 7 (1.1) | 2 (0.3) |

| 30 | 676 | 586 (86.7) | 90 (13.3) | 29 (4.3) | 11 (1.6) | 5 (0.7) | 775 | 583 (75.2) | 192 (24.8) | 60 (7.7) | 19 (2.5) | 9 (1.2) |

| 40 | 540 | 384 (71.1) | 156 (28.9) | 65 (12.0) | 30 (5.6) | 13 (2.4) | 492 | 315 (64.0) | 177 (36.0) | 79 (16.1) | 34 (6.9) | 11 (2.2) |

| 50 | 339 | 182 (53.7) | 157 (46.3) | 86 (25.4) | 43 (12.7) | 22 (6.5) | 358 | 193 (53.9) | 165 (46.1) | 89 (24.9) | 59 (16.5) | 30 (8.4) |

| 60 | 204 | 78 (38.2) | 126 (61.8) | 89 (43.6) | 52 (25.5) | 29 (14.2) | 209 | 84 (40.2) | 125 (59.8) | 89 (42.6) | 54 (25.8) | 35 (16.7) |

| 70 | 109 | 27 (24.8) | 82 (75.2) | 62 (56.9) | 45 (41.3) | 30 (27.5) | 114 | 26 (22.8) | 88 (77.2) | 73 (64.0) | 55 (48.2) | 40 (35.1) |

| 80 | 42 | 6 (14.3) | 36 (85.7) | 32 (76.2) | 26 (61.9) | 19 (45.2) | 57 | 14 (24.6) | 43 (75.4) | 35 (61.4) | 30 (52.6) | 23 (40.4) |

| Non-Hispanic | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 8773 | 7627 (86.9) | 1146 (13.1) | 75 (0.9) | 6 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 8278 | 7505 (90.7) | 773 (9.3) | 44 (0.5) | 4 (<0.1) | 2 (<0.1) |

| 20 | 9098 | 7033 (77.3) | 2065 (22.7) | 411 (4.5) | 65 (0.7) | 13 (0.1) | 9999 | 7410 (74.1) | 2589 (25.9) | 593 (5.9) | 120 (1.2) | 22 (0.2) |

| 30 | 9799 | 8027 (81.9) | 1772 (18.1) | 513 (5.2) | 172 (1.8) | 59 (0.6) | 11 283 | 8032 (71.2) | 3251 (28.8) | 898 (8.0) | 257 (2.3) | 71 (0.6) |

| 40 | 8059 | 5352 (66.4) | 2707 (33.6) | 1011 (12.5) | 420 (5.2) | 184 (2.3) | 8546 | 5200 (60.8) | 3346 (39.2) | 1237 (14.5) | 444 (5.2) | 170 (2.0) |

| 50 | 9620 | 4811 (50.0) | 4809 (50.0) | 2537 (26.4) | 1230 (12.8) | 550 (5.7) | 10 616 | 5175 (48.7) | 5441 (51.3) | 2616 (24.6) | 1215 (11.4) | 584 (5.5) |

| 60 | 6962 | 2014 (28.9) | 4948 (71.1) | 3366 (48.3) | 2063 (29.6) | 1027 (14.8) | 7694 | 2189 (28.5) | 5505 (71.5) | 3532 (45.9) | 2075 (27.0) | 1090 (14.2) |

| 70 | 4314 | 716 (16.6) | 3598 (83.4) | 3004 (69.6) | 2238 (51.9) | 1437 (33.3) | 4858 | 721 (14.8) | 4137 (85.2) | 3392 (69.8) | 2386 (49.1) | 1439 (29.6) |

| 80 | 2535 | 211 (8.3) | 2324 (91.7) | 2117 (83.5) | 1834 (72.3) | 1413 (55.7) | 3246 | 309 (9.5) | 2937 (90.5) | 2627 (80.9) | 2154 (66.4) | 1567 (48.3) |

| Hispanic | ||||||||||||

| 10 | 780 | 684 (87.7) | 96 (12.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 758 | 696 (91.8) | 62 (8.2) | 5 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 20 | 659 | 549 (83.3) | 110 (16.7) | 23 (3.5) | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 712 | 557 (78.2) | 155 (21.8) | 35 (4.9) | 10 (1.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| 30 | 873 | 747 (85.6) | 126 (14.4) | 33 (3.8) | 9 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) | 814 | 618 (75.9) | 196 (24.1) | 57 (7.0) | 19 (2.3) | 10 (1.2) |

| 40 | 598 | 425 (71.1) | 173 (28.9) | 66 (11.0) | 28 (4.7) | 8 (1.3) | 530 | 344 (64.9) | 186 (35.1) | 61 (11.5) | 26 (4.9) | 6 (1.1) |

| 50 | 497 | 267 (53.7) | 230 (46.3) | 109 (21.9) | 50 (10.1) | 19 (3.8) | 418 | 237 (56.7) | 181 (43.3) | 101 (24.2) | 59 (14.1) | 30 (7.2) |

| 60 | 313 | 117 (37.4) | 196 (62.6) | 132 (42.2) | 76 (24.3) | 34 (10.9) | 249 | 94 (37.8) | 155 (62.2) | 103 (41.4) | 60 (24.1) | 32 (12.9) |

| 70 | 125 | 28 (22.4) | 97 (77.6) | 75 (60.0) | 57 (45.6) | 35 (28.0) | 123 | 33 (26.8) | 90 (73.2) | 69 (56.1) | 49 (39.8) | 27 (22.0) |

| 80 | 43 | 11 (25.6) | 32 (74.4) | 28 (65.1) | 25 (58.1) | 15 (34.9) | 52 | 10 (19.2) | 42 (80.8) | 34 (65.4) | 30 (57.7) | 20 (38.5) |

Figure 1.

Accumulation of chronic conditions over age in the overall population (both sexes and all race and ethnicity groups combined).

bmjopen-2020-042633supp002.pdf (243.8KB, pdf)

Table 3 shows the look-up values for percentile ranks of multimorbidity by age in the overall population (both sexes and all race and ethnicity groups combined). Even though our study included all ages, we restricted the display to single years of age between 50 and 85 years because in this age range there were sizeable differences across persons, allowing the separation of percentiles across the number of conditions. This table can be used to assign a percentile rank to persons given their age and number of chronic conditions. For example, a person of age 63 with 3 conditions is in the 66th percentile, whereas, a person of age 83 with three conditions is in the 27th percentile. Online supplemental table 3 shows the percentile distribution of multimorbidity for all ages from 1 to 85 years in men and women combined and separately.

Table 3.

Look-up table for the percentile rank of persons in the general population using age and number of chronic conditions

| Age, years* | No of DHHS-defined chronic conditions† | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ≥11‡ | |

| 50 | 49 | 74 | 87 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 99 | ---§ | --- | --- | --- |

| 51 | 46 | 72 | 86 | 93 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 52 | 44 | 70 | 85 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 53 | 42 | 68 | 83 | 92 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 54 | 40 | 66 | 81 | 91 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 55 | 38 | 64 | 80 | 90 | 95 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 56 | 36 | 61 | 78 | 89 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 57 | 34 | 59 | 76 | 88 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 58 | 32 | 57 | 75 | 87 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 59 | 30 | 55 | 73 | 86 | 93 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 60 | 29 | 53 | 71 | 85 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 61 | 27 | 50 | 69 | 84 | 92 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 62 | 26 | 48 | 67 | 83 | 91 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 63 | 25 | 46 | 66 | 81 | 91 | 95 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- | --- |

| 64 | 24 | 45 | 64 | 80 | 90 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 65 | 23 | 43 | 62 | 79 | 89 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 66 | 22 | 41 | 59 | 77 | 88 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 67 | 20 | 38 | 57 | 75 | 87 | 93 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 68 | 19 | 35 | 54 | 73 | 86 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 69 | 17 | 33 | 52 | 71 | 84 | 92 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 70 | 16 | 30 | 49 | 68 | 83 | 91 | 95 | 98 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 71 | 15 | 28 | 47 | 66 | 81 | 90 | 95 | 97 | 99 | --- | --- |

| 72 | 14 | 27 | 45 | 64 | 80 | 89 | 95 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- |

| 73 | 13 | 25 | 43 | 62 | 78 | 88 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- |

| 74 | 12 | 24 | 41 | 60 | 76 | 87 | 93 | 97 | 98 | 99 | --- |

| 75 | 11 | 23 | 39 | 58 | 75 | 86 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- |

| 76 | 11 | 22 | 37 | 56 | 73 | 84 | 92 | 96 | 98 | 99 | --- |

| 77 | 10 | 21 | 35 | 54 | 71 | 83 | 91 | 95 | 98 | 99 | --- |

| 78 | 10 | 20 | 34 | 52 | 69 | 82 | 90 | 95 | 97 | 99 | --- |

| 79 | 9 | 19 | 32 | 50 | 67 | 81 | 89 | 95 | 97 | 99 | --- |

| 80 | 9 | 18 | 31 | 48 | 65 | 79 | 88 | 94 | 97 | 98 | 99 |

| 81 | 8 | 16 | 29 | 46 | 64 | 78 | 87 | 93 | 97 | 98 | 99 |

| 82 | 8 | 16 | 28 | 45 | 63 | 76 | 86 | 93 | 96 | 98 | 99 |

| 83 | 8 | 15 | 27 | 44 | 62 | 75 | 85 | 92 | 96 | 98 | 99 |

| 84 | 8 | 15 | 26 | 43 | 60 | 74 | 84 | 92 | 96 | 98 | 99 |

| 85 | 8 | 14 | 26 | 42 | 59 | 73 | 83 | 91 | 95 | 98 | 99 |

*To shorten the table, age look-up values are only given for ages 50 through 85. The percentiles for younger ages are reported in online supplemental table 3.

†The number of chronic conditions from among the 20 conditions defined by DHHS.

‡The presence of ≥11 chronic conditions maps to the 99th percentile at all ages.

§To reduce the density of numbers reported in the table, we use ‘---’ to denote that the 99th percentile has been reached.

DHHS, Department of Health and Human Services.

Association of the percentile ranks with mortality

The median length of follow-up for the birth cohorts varied depending on the anchoring birthday age. In particular, the median was 7.4 (IQR 4.8–9.9) for 50 years, 6.8 (IQR 4.5–9.6) for 55 years, 6.7 (IQR 4.5–9.5) for 60 years, 6.6 (IQR 4.4–9.5) for 65 years, 6.6 (IQR 4.4–9.4) for 70 years, 6.3 (IQR 4.3–9.0) for 75 years, 5.8 (IQR 3.8–8.3) for 80 years and 4.7 (IQR 3.1–7.0) for 85 years. Table 4 shows the HR of death through last follow-up in quintiles 1, 2, 4 and 5 compared with quintile 3, used as the reference, and separately for eight age cohorts (from 50 to 85 years, in 5-year increments) for men and women combined. In general, the HRs were larger for quintiles 4 and 5 compared with quintile 3 within each age cohort. The HR of death for quintile 5 compared with quintile 3 was higher in younger age cohorts (50, 55, 60 and 65) than in older age cohorts (70, 75, 80 and 85). Table 4 also shows the percent of persons who died at 1 year and 5 years in the five quintiles, for men and women separately. As expected, men experienced a higher mortality than women across all quintiles and all age cohorts.

Table 4.

Risk of death by quintile of number of chronic conditions, men and women combined for ages 50–85 (in 5-year increments), and percent of men and women who died at 1-year and 5-year follow-up

| Birthday cohort, years |

Quintile | No of DHHS-defined conditions* | Total Persons N |

Deaths N (%) |

Person-years | Risk of death† | Percent who died (95% CI)‡ | ||||

| Men | Women | ||||||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | 1 year | 5 years | 1 year | 5 years | ||||||

| 50 | 1 | 0 | 10 490 | 208 (2.0) | 77 609 | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.08) | 0.19 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) |

| 2/3 § | 1 | 5298 | 118 (2.2) | 39 261 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.5) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.6) | |

| 4 | 2 | 2809 | 103 (3.7) | 20 700 | 1.62 (1.25 to 2.11) | 0.0003 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.8) | 2.4 (1.7 to 3.4) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.7) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | |

| 5 | ≥3 (max=11) | 2554 | 195 (7.6) | 17 591 | 3.64 (2.89 to 4.57) | <0.0001 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) | 5.7 (4.5 to 7.2) | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 5.0 (3.8 to 6.4) | |

| 55 | 1 | 0 | 7454 | 185 (2.5) | 52 332 | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.31) | 0.74 | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.3) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.2) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.3) |

| 2/3 § | 1 | 4900 | 118 (2.4) | 35 288 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 2.4 (1.8 to 3.1) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.3) | |

| 4 | 2 | 3122 | 103 (3.3) | 22 600 | 1.33 (1.02 to 1.73) | 0.04 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 1.9 (1.3 to 2.8) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.8) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) | |

| 5 | ≥3 (max=12) | 3796 | 290 (7.6) | 25 875 | 3.27 (2.64 to 4.06) | <0.0001 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.6) | 6.3 (5.2 to 7.5) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.9) | 3.7 (2.9 to 4.7) | |

| 60 | 1 | 0 | 4414 | 201 (4.6) | 30 588 | 1.02 (0.82 to 1.28) | 0.83 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 3.5 (2.8 to 4.5) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.4) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) |

| 2 | 1 | 3671 | 125 (3.4) | 26 042 | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.98) | 0.03 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 2.9 (2.1 to 3.8) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.5) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) | |

| 3 | 2 | 2859 | 130 (4.5) | 20 458 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.9) | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.5) | 2.1 (1.4 to 2.9) | |

| 4 | 3 | 2091 | 104 (5.0) | 14 676 | 1.10 (0.85 to 1.42) | 0.47 | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) | 3.8 (2.8 to 5.2) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.6) | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.8) | |

| 5 | ≥4 (max=13) | 2183 | 249 (11.4) | 14 259 | 2.82 (2.28 to 3.49) | <0.0001 | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.3) | 9.7 (8.0 to 11.8) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | 5.7 (4.5 to 7.4) | |

| 65 | 1 | 0 | 2889 | 186 (6.4) | 19 605 | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.35) | 0.48 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.3) | 5.0 (3.9 to 6.3) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.8) | 2.4 (1.7 to 3.4) |

| 2 | 1 | 2312 | 134 (5.8) | 16 534 | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.17) | 0.54 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) | 4.9 (3.7 to 6.5) | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.8) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.1) | |

| 3 | 2 | 2237 | 143 (6.4) | 16 302 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.1) | 4.0 (2.9 to 5.5) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) | 2.1 (1.5 to 3.2) | |

| 4 | 3, 4 | 3238 | 290 (9.0) | 22 631 | 1.47 (1.21 to 1.80) | 0.0001 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.5) | 5.7 (4.6 to 7.0) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 3.6 (2.8 to 4.6) | |

| 5 | ≥5 (max=12) | 1194 | 263 (22.0) | 7342 | 4.23 (3.45 to 5.19) | <0.0001 | 3.7 (2.5 to 5.6) | 14.7 (12.0 to 18.0) | 4.0 (2.7 to 6.0) | 14.0 (11.4 to 17.2) | |

| 70 | 1 | 0, 1 | 2880 | 290 (10.1) | 19 887 | 0.86 (0.72 to 1.02) | 0.09 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.5) | 6.9 (5.6 to 8.5) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.1) | 4.3 (3.4 to 5.6) |

| 2 | 2 | 1810 | 172 (9.5) | 13 412 | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.91) | 0.004 | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.7) | 6.2 (4.7 to 8.2) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) | 4.4 (3.3 to 5.9) | |

| 3 | 3 | 1792 | 215 (12.0) | 12 714 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.7 (1.0 to 2.9) | 8.2 (6.4 to 10.4) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.7) | 4.9 (3.7 to 6.5) | |

| 4 | 4 | 1377 | 198 (14.4) | 9404 | 1.25 (1.03 to 1.52) | 0.02 | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.2) | 9.7 (7.6 to 12.3) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.4) | 6.0 (4.5 to 8.2) | |

| 5 | ≥5 (max=13) | 1561 | 410 (26.3) | 9386 | 2.68 (2.27 to 3.17) | <0.0001 | 4.2 (3.0 to 5.8) | 20.1 (17.4 to 23.1) | 3.9 (2.7 to 5.5) | 13.6 (11.3 to 16.4) | |

| 75 | 1 | 0, 1 | 1695 | 320 (18.9) | 11 529 | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | 0.29 | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.4) | 11.1 (8.9 to 13.7) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | 7.7 (6.1 to 9.8) |

| 2 | 2, 3 | 2669 | 463 (17.3) | 18 777 | 0.81 (0.69 to 0.95) | 0.008 | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | 10.8 (9.0 to 12.8) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.6) | 6.1 (5.0 to 7.5) | |

| 3 | 4 | 1187 | 237 (20.0) | 8037 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.4) | 11.9 (9.3 to 15.1) | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.1) | 7.4 (5.5 to 9.8) | |

| 4 | 5 | 806 | 228 (28.3) | 4948 | 1.58 (1.32 to 1.90) | <0.0001 | 3.6 (2.2 to 5.9) | 17.5 (14.1 to 21.7) | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.4) | 16.6 (13.0 to 20.9) | |

| 5 | ≥6 (max=15) | 999 | 414 (41.4) | 5539 | 2.71 (2.31 to 3.18) | <0.0001 | 5.7 (4.0 to 8.1) | 30.7 (26.7 to 35.2) | 5.9 (4.1 to 8.4) | 26.3 (22.5 to 30.6) | |

| 80 | 1 | 0, 1, 2 | 1833 | 620 (33.8) | 11 897 | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.92) | 0.001 | 3.8 (2.6 to 5.5) | 20.0 (17.1 to 23.3) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.2) | 13.9 (11.9 to 16.2) |

| 2 | 3 | 1028 | 337 (32.8) | 6724 | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.91) | 0.001 | 3.0 (1.8 to 5.1) | 19.7 (16.2 to 24.0) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.1) | 14.9 (12.1 to 18.2) | |

| 3 | 4 | 1023 | 392 (38.3) | 6347 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 3.4 (2.1 to 5.5) | 21.3 (17.7 to 25.5) | 2.2 (1.2 to 3.8) | 17.6 (14.6 to 21.2) | |

| 4 | 5, 6 | 1354 | 599 (44.2) | 7791 | 1.30 (1.14 to 1.47) | <0.0001 | 4.0 (2.8 to 5.8) | 28.5 (25.1 to 32.3) | 4.4 (3.1 to 6.2) | 26.2 (23.0 to 29.7) | |

| 5 | ≥7 (max=13) | 638 | 383 (60.0) | 2743 | 2.76 (2.39 to 3.18) | <0.0001 | 10.0 (7.1 to 13.9) | 53.8 (48.1 to 59.8) | 8.9 (6.3 to 12.5) | 41.9 (36.5 to 47.8) | |

| 85 | 1 | 0, 1, 2 | 1146 | 616 (53.8) | 6485 | 0.82 (0.74 to 0.91) | 0.0002 | 5.0 (3.2 to 7.6) | 31.2 (26.7 to 36.2) | 4.8 (3.5 to 6.6) | 28.7 (25.4 to 32.3) |

| 2 | 3 | 688 | 352 (51.2) | 3855 | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.91) | 0.0008 | 4.2 (2.3 to 7.6) | 32.5 (26.6 to 39.2) | 3.8 (2.4 to 6.0) | 28.0 (24.0 to 32.6) | |

| 3 | 4, 5 | 1343 | 760 (56.6) | 6955 | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 5.9 (4.2 to 8.2) | 38.4 (34.3 to 42.9) | 4.8 (3.5 to 6.5) | 35.1 (31.8 to 38.6) | |

| 4 | 6 | 414 | 270 (65.2) | 1888 | 1.39 (1.21 to 1.60) | <0.0001 | 9.1 (5.7 to 14.5) | 57.3 (49.5 to 65.3) | 5.5 (3.2 to 9.2) | 43.1 (37.0 to 49.9) | |

| 5 | ≥7 (max=15) | 690 | 505 (73.2) | 2608 | 1.97 (1.76 to 2.21) | <0.0001 | 15.9 (12.3 to 20.5) | 63.6 (58.1 to 69.2) | 14.6 (11.4 to 18.6) | 59.8 (54.6 to 65.2) | |

*The number of chronic conditions from among the 20 conditions defined by DHHS.

†The risk of death from Cox proportional-hazards models was adjusted for sex (male vs female), race (non-White vs White), ethnicity (Hispanic vs non-Hispanic) and calendar year at birthday (2005–2009 vs 2010–2014). However, the results changed minimally before and after the adjustments. Follow-up was assessed for persons through 31 December 2017. The median follow-up in years was 7.4 (IQR 4.8–9.9) for the age 50 years birthday cohort, 6.8 (IQR 4.5–9.6) for 55 years, 6.7 (IQR 4.5–9.5) for 60 years, 6.6 (IQR 4.4–9.5) for 65 years, 6.6 (IQR 4.4–9.4) for 70 years, 6.3 (IQR 4.3–9.0) for 75 years, 5.8 (IQR 3.8–8.3) for 80 years and 4.7 (IQR 3.1–7.0) for 85 years. In a set of alternative analyses, we measured the increase in HR when adding one more chronic condition at different levels of morbidity, across different ages. For a comparison, we report the HRs for age 60 and 85 years. At age 60 years, the HR was 1.2 for >0 vs 0; 2.0 for >1 vs 1; 1.9 for >2 vs 2; 2.5 for >3 vs 3 and 3.1 for >4 vs 4. At age 85 years, the HR was 1.0 for >0 vs 0; 1.6 for >1 vs 1; 1.4 for >2 vs 2; 1.6 for >3 vs 3 and 1.5 for >4 vs 4.

‡The per cent who died at 1 year and 5 years after respective birthdays as calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimator.

§For the cohorts at ages 50 and 55, the second and third quintiles were pooled and used as reference to avoid a quintile stratum being undefined (ie, empty). This pooling was necessary at younger ages because an increment of a single additional chronic condition can lead to a large jump in the modelled percentiles.

DHHS, Department of Health and Human Services.

Online supplemental table 4 shows the same cohort analyses separately for men and women. In stratum-specific comparisons, the HR of death was significantly higher in women than in men for quintile 5 compared with quintile 3 in the age cohorts 65 and 70 years. A global test of difference between men and women across all five quintiles was statistically significant for the age cohorts 65, 70 and 75 years.

Discussion

Principal findings

We provide tabular and graphical displays of the prevalence and percentile distribution of multimorbidity across age in a geographically defined population, and demonstrate that higher percentiles are associated with higher risk of death. Although multimorbidity accumulated more rapidly in men than women at older ages, in blacks compared with Asians, and in non-Hispanics compared with Hispanics, the differences were small. Therefore, if these demographic patterns are confirmed in other populations, we propose that a single overall set of percentile ranks may be used in clinical predictions. Higher quintiles of multimorbidity were associated with increased mortality both at 1 year and at 5 years. For several age groups, the risk of death through the last follow-up was higher in women than men in the same quintile of multimorbidity.

Our findings suggest that the percentile rank of a person compared with the peers of same age is associated with short-term mortality. The association is particularly strong for younger age cohorts (50–65 years) compared with older age cohorts (70–85 years). For older age cohorts, age itself is the major predictor of death, regardless of the percentile rank for multimorbidity. We also noted that the association between percentile rank and short-term mortality was greater for women than for men, especially in the younger age cohorts (50–75 years). The explanation for this sex or gender effect remains unclear. Even though the objective of this study was to consider the number of conditions rather than the individual conditions, we explored the modifying effect of age on the association of individual conditions with mortality (online supplemental table 5 and figure 5). For most chronic conditions, the association with mortality attenuated with increasing age.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strengths of this study include access to medical record data (specifically, billing codes) on all conditions for an entire geographically defined population across age, sex, race and ethnic groups, regardless of insurance status, socioeconomic status and care delivery setting. Nevertheless, we may have been unable to capture some unique populations such as homeless persons and immigrants who did not receive care from any of the care providers participating in the REP. Because data were generated historically as part of routine medical care, patients were not involved in remembering or reporting medical events or diagnoses. Medical record data are often difficult to obtain in the USA because there is no centralised healthcare surveillance system. In 2013, Wallace and Salive recognised that in the USA, there are no comprehensive, clinical records-based data sets for all ages and for all regions.14 Therefore, the REP offered a unique setting to study multimorbidity across all ages within a local context.5 15

A limitation of this study, which is shared with many other similar studies, is the limited validity of ICD-9 codes. Previous REP studies have shown that codes may be assigned in error, and manual review of the medical records is often needed to ascertain whether a person truly has the disease or condition of interest.5 25–29 We limited false positive diagnoses by requiring at least two diagnostic codes separated by more than 30 days for each condition. However, we may have excluded some persons who were actually affected by the condition (reduced sensitivity). Because the underdiagnosis of medical conditions may differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, some of our findings may reflect a diagnostic bias.

Second, there is not agreement on the optimal number and type of conditions needed to define multimorbidity, or on the advantages and disadvantages of using weights for the conditions included. There is no universally recommended list of conditions, and the optimal way to measure multimorbidity likely depends on the purpose of the study. We used the unweighted DHHS list of 20 conditions to improve reproducibility, at least within the USA. This list includes conditions that frequently co-occur (eg, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia) and conditions with low frequency in the ageing population (eg, autism). In addition, the DHHS list does not include conditions such as obesity or severe sensory limitations that may be both common and important for prognosis. Nevertheless, in our validation study, the multimorbidity percentile ranking of persons obtained using the 20 DHHS conditions was comparable to the ranking obtained using the more extensive list of 190 CCS chronic conditions, especially at ages 40 and older. These findings suggest that the 20 DHHS conditions may be adequate in number and type to rank persons in the population relative to peers of same age. The use of percentile ranks reduces the differences observed when using crude multimorbidity counts (or scores) based on lists with different numbers and types of conditions.

A third limitation was the cross-sectional nature of the analyses used to develop the percentile profiles.17 The persons residing in the county over a 10 calendar-year period were sampled based on having reached a certain birthday age. Therefore, the percentile distributions were based on the assumptions that all persons in a given age, sex, race or ethnic group had the same multimorbidity score regardless of the calendar year of the measure or of the calendar year of birth. We assumed that there were no systematic shifts in the distribution of multimorbidity over the 10 calendar-year study period and no birth cohort effects. In support of this assumption, a comparison of the modelled percentile distributions in the two calendar-year quinquennia of the study (2005–2009 and 2010–2014) showed only small calendar year differences (see online supplemental figure 4).

Finally, our study focused on a single geographically defined US population, and the percentile distribution of multimorbidity may differ in other populations. However, we have shown that the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of our population are similar to those of the upper Midwest.30 Nevertheless, the ability of quintiles of multimorbidity to predict mortality must be replicated in other populations with similar and with different sociodemographic characteristics to assess the generalisability of our findings.

Comparison with other studies

Although there is a large and growing body of literature describing the patterns of multimorbidity in populations from the USA and worldwide, we are not aware of studies that used our approach to assign percentile ranks of multimorbidity to persons throughout their life in a geographically defined population. The use of percentile ranks may reduce the lack of comparability of results from studies using different numbers or types of chronic conditions to define multimorbidity. If they are confirmed in other populations, our look-up tables may prove to be a simple and useful clinical tool to make short-term predictions.

Possible interpretation of our findings

Unfortunately, there is no consensus about how many conditions or clusters of conditions, or what severity of conditions, are needed to define accelerated ageing.9 If we accept the use of multimorbidity as a clinical measure of accelerated ageing at the cellular, tissue, organ or system level, our suggested use of percentile ranks may be of clinical use. The percentile rank provides a simple and intuitive measure of the health of a person as compared with peers of the same age. Our analyses for short-term mortality confirm the predictive value of percentile ranks. Percentile ranks of multimorbidity may also be useful in research studies to stratify the population for case–control studies, cohort studies and clinical trials. However, our findings need to be replicated in independent studies before they can be considered for clinical or research uses.

Conclusions

The assignment of a percentile rank of multi-morbidity to persons in a population may be a simple and intuitive way to describe the health status of persons relative to their peers of the same age. In addition, the percentile ranks may be useful predictors of future adverse outcomes, such as short-term mortality. Finally, the use of percentile ranks in research projects may reduce the lack of comparability across studies using different numbers or types of chronic conditions to define multi-morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Kristi Klinger for her assistance in typing and formatting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: WAR, BRG and JLS were involved in the conception and design of the study. BRG and WAR conducted the data analyses. WAR drafted the manuscript. All authors (WAR, BRG, CMB, AMC, WVB and JLS) contributed to the interpretation of the data and provided critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors (WAR, BRG, CMB, AMC, WVB and JLS) also approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This study used the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (grants R01 AG034676 and R01 AG052425). WAR was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21 AG058738, U54 AG044170, U01 AG006786 and P01 AG004875).

Disclaimer: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All study procedures and ethical aspects were approved by the institutional review boards of both Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center. Because the data collection was historical, persons did not need to provide a study-specific informed consent but rather a general consent to use their medical records for research (Minnesota legal requirements).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Investigators interested in using the normative data for multimorbidity from the Rochester Epidemiology Project to test specific hypotheses can contact WAR via email (rocca@mayo.edu). The correspondence should include a brief outline of the intended project (not longer than a page).

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Fabbri E, Zoli M, Gonzalez-Freire M, et al. Aging and multimorbidity: new tasks, priorities, and frontiers for integrated gerontological and clinical research. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:640–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.St Sauver JL, Boyd CM, Grossardt BR, et al. Risk of developing multimorbidity across all ages in an historical cohort study: differences by sex and ethnicity. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006413. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabbri E, An Y, Zoli M, et al. Association between accelerated multimorbidity and age-related cognitive decline in older Baltimore longitudinal study of aging participants without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:965–72. 10.1111/jgs.14092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vetrano DL, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Marengoni A, et al. An international perspective on chronic multimorbidity: approaching the elephant in the room. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:1350–6. 10.1093/gerona/glx178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocca WA, Boyd CM, Grossardt BR, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in a geographically defined American population: patterns by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:1336–49. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobo WV, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, et al. Prevalence of combined somatic and mental health multimorbidity: patterns by age, sex, and Race/Ethnicity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:1483–91. 10.1093/gerona/glw032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Violán C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Roso-Llorach A, et al. Burden of multimorbidity, socioeconomic status and use of health services across stages of life in urban areas: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014;14:530. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocca WA, Gazzuola-Rocca L, Smith CY, et al. Accelerated accumulation of multimorbidity after bilateral oophorectomy: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:1577–89. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocca WA, Gazzuola Rocca L, Smith CY, et al. Bilateral oophorectomy and accelerated aging: cause or effect? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;72:1213–7. 10.1093/gerona/glx026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocca WA, Gazzuola Rocca L, Smith CY, et al. Loss of ovarian hormones and accelerated somatic and mental aging. Physiology 2018;33:374–83. 10.1152/physiol.00024.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine ME, Lu AT, Chen BH, et al. Menopause accelerates biological aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:9327–32. 10.1073/pnas.1604558113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horvath S. Dna methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol 2013;14:R115. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace RB, Salive ME. The dimensions of multiple chronic conditions: where do we go from here? A commentary on the special issue of preventing chronic disease. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E59. 10.5888/pcd10.130104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posner SF, Goodman RA. Multimorbidity at the local level: implications and research directions. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:1321–3. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porta M. A dictionary of epidemiology. 6th edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Connor PJ. Normative data: their definition, interpretation, and importance for primary care physicians. Fam Med 1990;22:307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data resource profile: the Rochester epidemiology project (Rep) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1614–24. 10.1093/ije/dys195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, et al. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E66. 10.5888/pcd10.120239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machado JAF, Silva JMCS. Quantiles for counts. J Am Stat Assoc 2005;100:1226–37. 10.1198/016214505000000330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quality AfHRa . Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP) website, 2012. Available: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp [Accessed Nov 2019].

- 22.Quality AfHRa . Medical expenditure panel survey HC-120, appendix 3: clinical classification code to ICD-9-CM code Crosswalk. Available: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h120/h120app3.html [Accessed Nov 2019].

- 23.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420–8. 10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leibson CL, Brown AW, Ransom JE, et al. Incidence of traumatic brain injury across the full disease spectrum: a population-based medical record review study. Epidemiology 2011;22:836–44. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318231d535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leibson CL, Naessens JM, Brown RD, et al. Accuracy of hospital discharge Abstracts for identifying stroke. Stroke 1994;25:2348–55. 10.1161/01.STR.25.12.2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leibson CL, Needleman J, Buerhaus P, et al. Identifying in-hospital venous thromboembolism (VTe): a comparison of claims-based approaches with the Rochester epidemiology project VTe cohort. Med Care 2008;46:127–32. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589b92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roger VL, Killian J, Henkel M, et al. Coronary disease surveillance in Olmsted County objectives and methodology. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:593–601. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00390-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yawn BP, Wollan P, St Sauver J. Comparing shingles incidence and complication rates from medical record review and administrative database estimates: how close are they? Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:1054–61. 10.1093/aje/kwr206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, et al. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:151–60. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-042633supp001.pdf (224.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-042633supp002.pdf (243.8KB, pdf)