Abstract

The population is ageing, but while average life expectancy continues to increase, healthy life expectancy has not necessarily matched this and negative ageing stereotypes remain prevalent. Self-directed ageing stereotypes are hypothesised to play an important role in older adults’ health and well-being; however, a wide variety of terms and measures are used to explore this construct meaning there is a lack of clarity within the literature. A review was conducted to identify tools used to measure self-directed ageing stereotype in older adults and evaluate their quality. Searches identified 109 papers incorporating 40 different measures. Most common were the Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale Attitude Towards Own Ageing (ATOA) subscale, Ageing Perceptions Questionnaire (APQ) and Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire. Despite being most frequently used, the ATOA was developed to measure morale in older adults rather than self-directed ageing stereotypes. Over 25 terms were used to describe the concept, and it is suggested that for consistency the term “self-directed ageing stereotype” be adopted universally. Across measures, poor reporting of psychometric properties made it difficult to assess scale quality and more research is needed to fully assess measures before conclusions can be drawn as to the best tool; however, the Brief-APQ appears to hold most promise. Future research must address this issue before interventions to reduce negative self-directed ageing stereotypes can be developed and fully evaluated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10433-020-00574-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Older adults, Stereotype, Questionnaire, Psychology, Self-directed stereotype

Introduction

The population is ageing rapidly; the World Health Organisation forecasts an increase in those age 65 and over from 14% of the population in 2010 to 25% in 2050 within the European region, with Europe having the highest median age in the world (World Health Organization 2020). However, while average life expectancy has increased steadily, healthy life expectancy has not necessarily matched this (Cracknell 2010; Age UK 2019). WHO reports that whether or not individuals spend their older adulthood in good health and well-being varies greatly both within and between European countries. Despite no clear consensus on the definition of “healthy ageing” (Liotta et al. 2018; van den Heuval and Olaroiu 2019), it is recognised both within academic literature (e.g. Reed et al. 2004) and in the work of charities (e.g. Age UK 2013) that research is crucial to understanding the experiences of older adults in order to break down the barriers preventing them from active participation in society.

An important psychological factor contributing to health and well-being is the way in which older adults think, act and feel about old age. Age discrimination has been found to be prevalent across Europe (Van Den Heuvel and Van Santvoort 2011), which may contribute to the pervasiveness of negative ageing stereotypes. Experimental laboratory research has shown that the internalisation of such stereotypes can have a negative impact on older adults (e.g. Levy 2009; Molden and Maxfield 2017). Therefore, interventions are needed to challenge negative attitudes towards ageing and instead develop more positive views (Van Den Heuvel and Van Santvoort 2011; Burton et al. 2018). In order to assess the effectiveness of such interventions, a psychometrically sound measure of self-directed ageing stereotypes must be identified.

Stereotype embodiment theory proposes that age stereotypes can be internalised across the lifespan (Levy 2009) and holding negative self-directed stereotypes can cause reductions in cognitive functioning and physical health (Levy 2003). Attributing illness and functional decline to old age and holding the belief that “to be old is to be ill” is associated with negative health outcomes and reductions in health maintenance behaviours (Beyer et al. 2015; Stewart et al. 2012). In support of this, Burton et al.’s (2018) research, into barriers and facilitators to physical activity in older people with sight loss, highlighted the role of self-directed ageing stereotypes. During focus groups participants frequently used examples of negative self-directed stereotypes to justify reduced participation in physical activity, for example “Young adults, rather than 70 or 80 year olds […] they are the ones that really need all of the exercise and can actually do it” (p. 28, Burton et al. 2018). Findings such as these demonstrate the importance of measuring levels of self-directed ageing stereotypes in older adults because interventions that do not address these are unlikely to be effective in changing behaviour.

Priming and stereotype threat research has illustrated this concept in laboratory experiments (e.g. Barber and Lee 2016; Bock and Akpinar 2016); however, outside of the laboratory, researchers need appropriate measurement tools. Several tools exist but there are broad variations in the measures used (Rothermund and Brandtstadter 2003; Sánchez Palacios et al. 2009; e.g. Levy et al. 2014a). Additionally, scales claiming to assess this concept often measure participants’ views of other older people as a group rather than the extent to which individuals hold these views about themselves. This is an important distinction because it is possible that individual identification with negative stereotypes, rather than holding negative views about old age, has the biggest implications for health outcomes (Levy 2009). In addition, there appears to be ambiguity in the nomenclature used including terms such as stereotype embodiment or endorsement, self-perceptions of ageing, personal views of ageing and subjective age (Miche et al. 2014). This highlights a major issue with research in this area and a clear definition can only be achieved once assessment has been made of how authors have defined and measured this concept in the existing literature. To facilitate further research, a universal term for the concept and a reliable and valid measure are needed.

Systematic reviews of measures enable the selection of the best instrument for specific purposes (Mokkink et al. 2009). A recent review identified and evaluated tools to explore attitudes to ageing in those under age 60 (Faudzi et al. 2019) reporting widespread ambiguity and poor psychometric properties. However, it is also vital to explore the methods used to measure this concept when self-directed by older adults.

Given the present need for research to improve the health and well-being of older adults, the detrimental effect of negative stereotypes on the ageing process and the ambiguity surrounding the definition and measurement of self-directed ageing stereotypes, this review aimed to: (1) Identify and describe the tools proposed by authors as measuring self-directed ageing stereotype in older adults, (2) Evaluate the quality of these measures and (3) Propose a universal term and definition for the concept of internalised ageing self-stereotype.

Methods

Search strategy

Articles were retrieved from the databases MEDLINE, Embase, PsychINFO, EBSCO, AMED, PROQUEST and Web of Science from earliest records to March 2017. Searches were conducted using a combination of the following search terms: ageing, elderly, older people, ageism, stereotype, self-perception, self-view, self-belief, self-directed. Terms were included using all potential formats and spellings. Reference sections of articles included in the review were also screened.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) participants or a specific participant group within the study must fall into the category of “older people”, (2) to capture the complexity of the terms used for this concept the study must include a measure where the participant considers their own ageing experience in relation to the experience of older people in general. This could include measures claimed by the author to be measuring self-directed stereotype, self-perception of ageing or an associated construct. Papers were rejected if: (1) the whole sample was under 60 as this would not assess the self-perception of older adults (2) measures assessed participants’ perceptions of older people as a group but did not assess how these perceptions relate to their own personal ageing experience (e.g. “older people are…” rather than “as an older person I am…”). Measures of perceptions of older people as a group were only included if the author claimed that these are a measure of “self-directed stereotype”, (3) papers were not published in English or were unavailable as official published translations, (4) unpublished, non-peer reviewed papers or conference abstracts.

Study selection

All initial search results were screened for inclusion by WD with 50% reviewed by AB and 50% reviewed by SD and good levels of inter-rater reliability (Kappa 0.329, 95% CI 0.210–0.448; Kappa 0.394, 95% CI 0.302–0.487).

Data extraction

Data extraction of key study features was conducted for all studies by both WD and AB; disagreements were reviewed by SD to check for accuracy. Top up data extraction was conducted by JR and checked by AB for accuracy, with SD reviewing disagreements. In addition to key study features, data extraction included the recording of information on initial scale development and published quality indicators relating to internal consistency, test–retest reliability, content validity, factor analysis to confirm scale structures and context regarding initial scale development (see Tables 1, 2). Where the original scale development paper did not meet review inclusion criteria (e.g. it was developed with younger adults), this was sourced to provide contextual information regarding scale development.

Table 1.

Summary of scale quality information

| Instrument (number of papers) | Version | Subscale | Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha range) | Reliability (test–retest) | Content validity (item development) | Factor analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude to Own Ageing (ATOA) subscale of PGCMS (N = 32) | Original (N = 27) | Total score | .61–.75 (KR20 = .78/KR21 = .65) | NR | NR | Single-factor structure confirmed (N = 4) (Kim et al. 2012; Levy et al. 2002a, b; Miche et al. 2014) |

| Ageing perceptions scale (N = 1) |

General perceptions of ageing Self-perceptions of ageing |

.59 .75 |

NR | NR | NR | |

| Self-perceptions of ageing scale (N = 1) | N/A | .82 | NR | NR | NR | |

| Single Item from ATOA (N = 2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Ageing Perceptions Questionnaire (N = 17) | Original APQ (N = 8) |

Timeline chronic Timeline cyclical Consequences positive Consequences negative Emotional representations Control negative Control positive Identity |

.80–.85 .84–.89 .63–.74 .80–.83 .74–.86 .52–.76 .70–80 NR |

.78 .79 .70 .83 .83 .61 .76 .75 |

Focus groups with older adults | Mixed evidence: structure confirmed (N = 1) (Barker et al. 2007); not confirmed (N = 3) (Ingrand et al. 2012; Sexton et al. 2014; Slotman et al. 2015) |

| Brief version B-APQ (N = 9) |

Total Timeline Positive consequences Positive control Negative consequences and control Emotional representations |

.75–.79 .69–.81 .53–.78 .77–.85 .67–.81 .70–.75 |

.95 .99 .90 .98 .99 .95 |

Based on original | Acceptable factor structure (N = 3) (Moghadam et al. 2016; Sexton et al. 2014; Slotman et al. 2017) | |

| Short Version APQ-S (N = 2) |

Timeline chronic Timeline cyclical Consequences positive Consequences negative Emotional representations Control negative Control positive |

.75–.81 .56–.76 .74–.80 .79–.82 .79 .76–.81 .69–.80 |

NR | Based on original | Acceptable factor structure (N = 2) (Slotman et al. 2015, 2017) | |

| Chinese APQ C-APQ (N = 1) |

Total scale Timeline chronic Timeline cyclical Consequences positive Consequences negative Emotional representations Control negative Control positive |

.88 .86 .70 0.66 0.83 0.83 0.82 0.74 |

All items above .8 | Based on original and examined by 7 experts | Acceptable factor structure (N = 1) (Chen et al. 2016) | |

| Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire | Original (N = 11) |

Total Psychosocial loss Physical change Psychological growth |

.78–.86 .70–.84 .62–.81 .59–.75 |

> .7 for all subscales (N = 1) | Literature review + focus groups with older adults and ageing expert consultation |

Mixed evidence: 3-factor structure confirmed (N = 3) (Laidlaw et al. 2007; Lucas-Carrasco et al. 2013; Marquet et al. 2016) Poor fit (N = 1) (Kalfoss et al. 2010) |

| Expectations Regarding Ageing (N = 6) |

ERA-38 Original (N = 3) |

Total General health Cognitive function Mental health |

> .73 | .96 | Focus groups and interviews with older adults | 10-factor structure not confirmed: 7-factor structure proposed (N = 1) (Sarkisian et al. 2005) |

| Functional independence | .61–.73 | |||||

|

Sexual function Sleep Fatigue Urinary incontinence Appearance |

||||||

| Pain | .58–.60 | |||||

|

ERA-38 Alternative subscale structure (N = 1) |

General ageing expectations | > .77 | NR | Used original items | Exploratory factor analysis used to develop new subscales (Sparks et al. 2013) | |

|

Satisfaction/contentment Physical functioning Cognitive functioning Self-expectations Functional health Social health Sexual function |

> .83 | |||||

| ERA-12 (N = 2) |

Total Physical health Mental health Cognitive function |

.88–.89 .79–.80 .75–.76 .76–.81 |

NR | Used original items checked against focus group data | Acceptable 3-factor structure in two samples (N = 1) (Sarkisian et al. 2005) | |

| Personal experience/Age Cog (N = 5) | Original (N = 3) |

Physical decline Continuous growth Social losses |

.77–.78 .68–.72 .67–.76 |

NR | Items developed through qualitative work with older adults | NR |

| Age Cog (N = 2) |

Physical losses Social losses Ongoing development Self-knowledge |

.79 NR .67–.75 NR |

NR | NR | Footnote confirming 4 factor Age Cog (N = 1) (Wurm et al. 2007) | |

| Symptom management beliefs | Original (N = 5) |

Total score Ageing stereotypes Pessimistic expectations Good patients’ attitudes |

.79–.83 | .73 | Gerontology literature and interviews with specialist health professionals | Acceptable 3-factor structure (N = 1) (Yeom 2013a) |

| Image of Ageing Scale | Adapted to be self-directed (N = 3) |

Positive words Negative words |

.80, 0.86 .72,0.85 |

NR | Older people asked to list the first 5 words/phrases that come to mind when thinking about an older person | NR |

| Chinese version of the self-image of ageing scale (SIAS-C) (N = 1) |

General physical health Social virtues Life attitudes Psychosocial status Cognition |

.51–.65 (Guttman split-half 0.42–.57) | 0.87 | Original scale items plus interviews with 30 Chinese older adults | 5-factor structure confirmed (Bai et al. 2012) | |

| Ageing Stereotypes and Exercise Scale | Original (N = 3) |

Psychological barriers Self-Efficacy Psychological capacities Risks of exercise Benefits of exercise |

.84 .78 .80 .81–.83 .80–.87 |

NR | Based on self-efficacy theory and existing exercise scales | NR |

| RSQ-Age | Original (N = 2) | Total score | .88–.95 | .74 | Older adults reported situations in which they had experienced age-based stigma | Single-factor structure confirmed (N = 1) (Kang and Chasteen 2009) |

| Ages of Me (N = 2) | Original | Total score | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Future self-views (N = 2) | Original | Total score | .81–.84 | NR | Items generated in an interview study with older people (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011) | 8-factor structure confirmed (Kornadt and Rothermund 2012; Voss et al. 2017) |

| Family and partnership | .67 | |||||

| Friends and acquaintances | NR | |||||

| Religion and spirituality | NR | |||||

| Leisure activities and social or civic commitment | .86 | |||||

| Personality and way of living | NR | |||||

| Financial situation and dealing with money-related issues | .66–.72 | |||||

| Work and employment | .74 | |||||

| Physical and mental fitness, health and appearance | .85–.89 |

NR not reported

Table 2.

Quality and descriptive characteristics of measures used in a single study

| Instrument example item | Paper | No. of items | Response format | Subscales | Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) | Reliability (test–retest interclass coefficients) | Content validity (item development) | Factor analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Semantic Differentials Example item: NR |

Luszcz and Fitzgerald (1986) | 28 |

Likert 1–7 |

(1) Personal acceptability vs unacceptability (2) Instrumentality versus ineffectiveness (3) Autonomy versus dependency (4) Integrity versus nonintegrity |

(1).83 (2).82 (3).83 (4).74 |

NR | NR | NR |

|

Semantic Differentials Example item: Patient–impatient |

Rothermund and Brandtstadter (2003) | 32 |

Likert 1–11 |

N/A | .92 | NR | NR | 1-factor structure confirmed |

|

Age Attributions Vignettes Example item: If you lost your keys how much would it be due to an age attribution and how much would it be due to an extenuating circumstance? |

Levy et al. (2009) | 2 |

Likert 1–6 strongly disagree–strongly agree |

(1) Cognitive (2) Physical |

(1) .59 (2) .50 |

NR | NR | NR |

|

(1) Negative age stereotypes subscale of Attitudes towards older people scale (ATOP) (Tuckman and Lorge 1953). Example item: “old people are absent minded” (2) Plus 1 self-relevance item: “at what age does someone become old?” |

Levy et al. (2012b) | 16 |

(1) Total score 0–16 (unclear how each item is rated) (2) Below own age scored as 1, above own age scored as 0 |

N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Outer and inner selves Item examples: “when you think about yourself what are the first 5 words that come to mind?” and “when you think of an old person what are the first 5 words that come to mind?” |

Levy (1999a) | 2 | Independent raters score word positivity level as negative, neutral or positive | N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Two subscales of the Frankfort Self-Concept Scale; (1) Self-concept of general self-efficacy; (2) Social competence (Deusinger 1986) Item example: NR |

Pinquart (2002) | 16 | Likert 1–6 completely true for me–not at all true for me | N/A | .70 | NR | NR | NR |

|

Self-other discrepancy measured with Harris Survey questions. Problem statements that participant rates in relation to people over 65 and then to themselves. Item example: Loneliness |

Schulz and Fritz (1987) | 8 | True/false | N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Identity and Experiences Scale: Specific Ageing (IES-SA) (Three subscales: assimilation, accommodation, balance) | Whitbourne and Collins (1998) | 21 | NR |

(1) Assimilation (2) Accommodation (3) Balance |

(1).59 (2).86 (3).69 |

NR | NR | 3-factor structure confirmed |

|

Illness Attributions. Level of agreement that their specific illness was partly due to several factors Item examples: “old age” “unhealthy behaviours”, “bad advice from a doctor” “bad luck”, “genetics” |

Stewart et al. (2012) | 5 |

Likert 1–6 Strongly agree–strongly disagree |

N/A | NR | NR | Attributions chosen based on theory to represent internal/external and controllable/uncontrollable factors | NR |

|

Perceived difficulty of life events. participants asked to rate extent to which life events had made life more difficult, first for themselves, and then for other older women and men Item example: Failing eyesight |

Sijuwade (1991) | 16 |

Likert 1–7 Much easier–much more difficult |

N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

A modification of the LaForge and Suczek (1955) Interpersonal adjective check list. Rated items for self and then for “most people my age” Item example: often helped by others. |

Preston and Gudiksen (1966) | 110 | T/F | N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Personality Dimensions with scales taken from the Jackson Personality Research Form (Jackson 1967) and additional scale on physical–sexual activity created for the study Item example: Autonomy |

Ahammer and Bennett (1977) | 88 | True/false |

(1) Abasement (2) Autonomy (3) Change (4) Cognitive Structure (5) Defendence (6) Endurance (7) Harm avoidance (8) Play (9) Sentience (10) Infrequency (11) Physical–sexual activity |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Ageing Anxiety Scale :items taken from Ageing Anxiety Scale (Kafer et al. 1980) Item example: I always worried about the day I would look in the mirror and see grey hairs |

Lynch (2000) | 7 |

Likert 1–4 Strongly agree–strongly disagree |

(1) Physical appearance (2) Physical health (3) General anxiety about the future (4) Financial dependence (5) Physical disability/mobility (6) Loss of social contacts (7) Loss of cognitive ability or autonomy to make decisions |

NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Anxiety about own ageing (Lasher and Faulkender 1993) Item example: “The older I become the more I worry about my health” |

Chasteen (2000) | 20 |

Likert 1–5 Strongly disagree–strongly agree |

N/A | .84 | NR | NR | NR |

|

Self-perceived adverse age change (Smith et al. 1995) Item example: As I get older it is harder for me to get through the day. |

Minnes et al. (2007) | 6 |

Likert 1–5 Strongly agree–Strongly disagree |

N/A | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

Perceived age vs desired age. Item examples: “Please could you tell us at what age you consider old age to start?”; “We would also like you to tell us at what age you consider middle age to end?”;“How old do you feel you are?”; “How old would you like to be? |

Demakakos et al. (2007) | 4 | Perceived boundaries coded into 5-year intervals |

(1) Self-perceived age: feeling as old as their chronological age, feeling older than it, feeling younger than it. (2) Desired age: want to be as old as their chronological age; would like to be younger than it. |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

Subjective Age Item examples: “How old do you feel”; “How old do you feel when you look at yourself in a mirror” |

Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. (2008) | 2 | Scale 0–120 years |

(1) Felt age (2) Physical age |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

(1) Negative Ageing Stereotypes Assessment Questionnaire CENVE (Blanca et al. 2005) (2) Additional question: “Regardless of your age, how old do you feel” |

Sánchez Palacios et al. (2009) | 15 |

Likert 1–4 Strongly agree–strongly disagree |

(1) Health stereotypes (2) Motivation—social (3) Character—personality |

(1).67 (2).64 (3).67 |

NR | Items taken from other scales that did not perform any validity/reliability checking | 3-factor structure confirmed |

|

Present/future selves (Ryff 1991) Item example: NR |

Cheng et al. (2009) | 59 |

Likert 1–6 Extremely uncharacteristic of me–extremely characteristic of me |

(1) Physical self (2) Social self (3) Material self (4) Work self |

(1).79, .78 (2).84, .86 (3) NR (4) NR |

NR | Items based on content analysis of possible selves produced by 530 young, midlife and older adults | NR |

|

Subjective age Item: “how old do you feel” |

Kotter-Gruhn et al. (2009) | 1 | 0–120 rating scale | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

The RAME Questionnaire (Parnell et al. 2001) Item example: fear of the ageing process |

Law et al. (2010) | 23 |

Likert 0–3 |

N/A | “Good” (Parnell et al. 2001) | NR | NR | NR |

|

Age identity Item: “Many people feel older or younger than they actually are. What age do you feel most of the time?” |

Westerhof et al. (2012) | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

Subjective age Item examples: How old do you feel?”; “If you could choose your age, how old would you want to be?”; “How old would you say you look?” |

Kotter-Gruhn and Hess (2012) | 3 | Proportional discrepancy scores. |

(1) Felt age (2) Desired age (3) Perceived age |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

Subjective age Item: “What age do you feel most of the time?” |

Chalabaev et al. (2013) | 1 | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

Fear of Ageing Scale. Item example: “I fear that as I get older I will be unable to do everything I want to” |

Chasteen et al. (2015) | 25 |

Likert 1–9 Strongly disagree–strongly agree |

Fear of: (1) Dependence (2) Cognitive decline (3) Physical decline (4) Loneliness (5) Depression (6) Losing attractiveness. |

Total score: .92 | NR | Items from expectations regarding ageing scale (Sarkisian et al. 2005) and Anxiety about Ageing Scale (Lasher and Faulkender 1993) | NR |

|

Semantic differentials assessing retirement stereotypes Rating pairs of adjectives Item example: what “best describes what you think about your life in retirement—and how your life is or will be during your retirement: inactive-active” |

Ng et al. (2016) | 14 |

Likert 1–7 Extremely meaningless–extremely meaningful |

(1) Mental well-being stereotypes (2) Physical well-being stereotypes |

(1) .79 (2) .91 |

NR | NR | 2-factor structure confirmed. |

|

Age Identity Measurement Scale (Jose and Meena 2015) Item example: NR |

Jose et al. (2016) | 17 |

Likert 1–4 Strongly agree–strongly disagree |

(1) Personalised self-image (2) Personalised social image (3) Importance to age identity |

(1).59 (2).90 (3).72 Total: .85 |

(1).21a–.66 (2).66 (3).70–.71a Total: .70a |

NR | NR |

|

Images of life change. Ratings of how well adjectives and domains described people in their late 60’s. Item example: NR |

Kornadt (2016) | 13 |

Likert 1–10 Not at all/worst–very much/best |

(1) Family relationships (2) Fitness/energy (3) Work/life (4) Wisdom |

NR | NR | Based on theoretical domains of development as a frame for personality in old age. | 4-factor structure confirmed |

|

Self-perceptions of ageing Items assessing positive and negative evaluations of ageing Item example: NR |

O’Shea et al. (2016) | 8 |

Likert 1–6 Strongly disagree–strongly agree |

N/A | .80 | NR | NR | NR |

NR not reported, N/A not applicable

aTest–retest interclass correlations based on unpublished work cited by the authors

Results

Search results and study selection

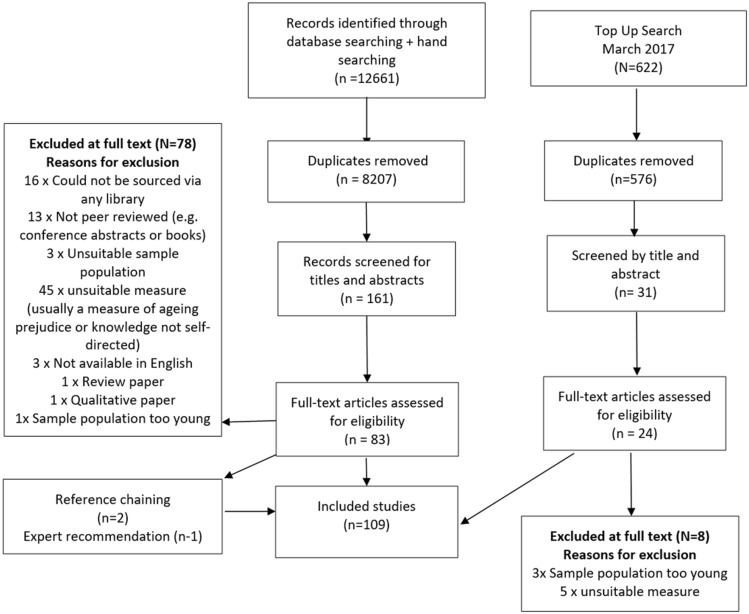

Results of the search and study selection procedure are displayed in Fig. 1. A total of 12,6661 papers were identified in the original search, a further 662 in the top up search, 2 from reference chaining and 1 from expert recommendations. Full text screening resulted in 109 studies for inclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of search process

Measure identification

A total of 40 measures were identified. Eleven were used in more than one study and four of these had been developed into more than one version: The Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale Attitude Towards Own Ageing (ATOA) subscale, Ageing Perceptions Questionnaire (APQ), Expectations Regarding Ageing (ERA) Survey and Personal Experience of Ageing Scale. Twenty-nine were used in single studies and have been categorised as “Measures used in a single study”. Quality indicators for each of these scales can be found in Tables 1 and 2. A summary of the sample characteristics and a reference list of the studies that used each measure is provided as a supplementary table (Online Resource 1).

Over 25 different terms were used to describe the concept of ageing self-stereotype. The most commonly used descriptor was “self-perceptions of ageing” (N = 33). Six descriptors included the term “stereotype”. Other common descriptors included: attitudes to ageing (N = 7), perceptions of ageing (N = 7) and expectations regarding ageing (N = 4). Terms including views, perceptions, cognitions, experiences, beliefs and stigma were also used.

Data synthesis

The 11 scales used in more than one study are discussed in turn, starting with the most commonly used. The measures that were used in a single study are discussed under the sub-heading “measures used in a single study”. For each, the construct that the scale was originally developed to measure and how it has been used in the ageing self-stereotype literature is detailed. Next a description of the scale and frequency of its use are given. This is followed by an evaluation of the quality of the scale based on the following criteria: (1) Was the scale originally developed to measure the construct of self-directed ageing stereotypes?; (2) How was the scale developed?, i.e. Is it theory based and did it involve consultation with relevant groups including the target age group, both of which are seen as indicators of quality (e.g. Newell and Burnard 2010); (3) Does the scale demonstrate internal consistency and test–retest reliability?; (4) Has the scale structure been confirmed with factor analysis?; (5) What is the overall evaluation of the measure?

The Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Moral Scale (PGCMS): attitude towards own ageing (ATOA) subscale

Construct

The PGCMS was developed by Lawton in 1972 (Lawton 1975) to measure morale in older adults and not to measure self-directed ageing stereotype. Despite this, the ATOA subscale was the most commonly used measure in the studies identified in the current review. It has predominantly been used to measure self-perceptions of ageing (19 studies), as well as ageing satisfaction (3 studies), attitudes towards own ageing (3 studies) and self-perceived uselessness (2 studies using a single item). Individual studies have also used it to measure negative ageing self-perceptions, attitudes to ageing, subjective well-being, personal views about ageing and ageing perceptions.

Description

The ATOA subscale of the PGCMS comprises five dichotomous questions, four with a yes/no format, e.g. “Things keep getting worse as I get older”, and one with a choice of better or worse “As I get older, things are better/worse than I thought they would be”. Responses representing “high-morale” are scored 1 and those representing “low-morale” 0, meaning total scores range from 0 to 5.

Thirty-two papers used the Attitude Towards Own Ageing (ATOA) subscale of the Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale (PGCMS) (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list). Two developed new measures of ageing perceptions based on the ATOA subscale (Sindi et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2017), and two used single questions from the ATOA assessing perceived uselessness (Gu et al. 2017; Zhao et al. 2017). The ATOA was developed in English and has been translated into five additional languages: German, French, Spanish, Korean and Arabic.

Quality

It is difficult to fully assess the quality of the ATOA due to the many modifications that have been made to it. None of the identified studies use the original formatting and scoring structure. There was variability in the scoring of the Yes/No responses for the first four items, some using 0–1 and others using 1–2 and in several papers the response “same” was added to the question “As I get older, things are better/worse than I thought they would be”. Two papers allocated a 1–3 score for the worse/same/better options (Levy et al. 2002a; Fernandez-Ballesteros et al. 2013), while several converted the final question to a dichotomous variable by combining same/better responses (Allen et al. 2015; Fernandez-Ballesteros et al. 2015; Levy and Myers 2004, 2005; Moser et al. 2011) or same/worse responses (Levy et al. 2002a). One paper adapted this question further specifying that the respondent should apply it to health concerns (Moser et al. 2011).

Another common modification has been to convert the wording to enable the response format to replicate that used for other scale questions, e.g. “as you/I get older things are better than you/I thought” (Beyer et al. 2015; Han and Richardson 2015; Jang et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2012; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Kotter-Gruhn et al. 2009; Miche et al. 2014; Park et al. 2015) or “as you/I get older things are worse than you/I thought” (Sargent-Cox et al. 2014; Wurm and Benyamini 2014). Some created a scale format where only yes/no or agree/disagree responses were possible for all questions, while others constructed Likert scales ranging from 1–4 to 1–7 and employing agree-disagree/applies to me-does not apply scales. The majority of papers combined responses to the questions to form a continuous scale however two used the scores to create a dichotomous satisfied/unsatisfied result though both used different cut-off levels for this (Macia et al. 2009; Moser et al. 2011).

The original ATOA was shown to have good internal consistency (α = .81) and a single-factor structure (Polisher Research Institute Abramson Center for Jewish Life; formerly the Philadelphia Geriatric Center). For the studies included in this review, the ATOA shows acceptable internal consistency (α = .61–.75); however, no studies have reported on test–retest reliability despite a number employing longitudinal designs. A single-factor structure has been confirmed for Korean (Kim et al. 2012), American (Levy et al. 2002a, 2012a) and German populations (Miche et al. 2014).

Overall evaluation

Overall, the key concern is that the ATOA scale was not developed to measure the construct of self-directed ageing stereotypes. While there is evidence to indicate the scale has acceptable internal consistency and the single-factor structure has been confirmed in certain groups, the test–retest reliability has not been reported on and the many modifications made to the scale make it difficult for the results of studies to be compared.

The Ageing Perceptions Questionnaire (APQ)

Construct

The APQ was developed by Barker et al. (2007) for assessing self-perceptions of ageing. Nine studies used it to measure this construct, seven to measure perceptions of ageing and one to measure negative perceptions of ageing.

Description

The APQ contains eight subscales. The first seven assess views about ageing and 32 items are rated on a 5-point Likert from strongly disagree to strongly agree with higher scores indicative of greater endorsement of a specific perception (Barker et al. 2007). The eighth subscale measures participants’ experiences of health-related changes. It consists of 17 possible health-related changes and participants must respond whether these have been experienced over the last 10 years (Yes/No) and if so whether they attribute these changes to getting older (Yes/No). Percentage of health-related changes attributed to ageing is calculated as the proportion of the number of health-related changes experienced with scores ranging from 0 to 100.

Seventeen papers used the original APQ or adapted versions of it (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list). The original Ageing Perceptions Questionnaire (APQ) was used in seven papers, the brief version (B-APQ) in eight and the short version (APQ-S) in two. The full APQ has been translated into three languages: French (Ingrand et al. 2012), Dutch (Slotman et al. 2015) and Brazilian-Portuguese (Ramos et al. 2012). In addition, a Chinese version of the scale has been produced (C-APQ) (Chen et al. 2016).

Quality

A strength of the APQ is that it is theory based, using Leventhal’s 1984 self-regulation model (SRM) (Barker et al. 2007). The relevance of the SRM dimensions to self-perceptions of ageing were explored in focus groups with older adults and judged to be a good explanatory model (Barker et al. 2007). However, the number of older adults consulted and the process for these focus groups and process for analysis and reaching consensus has not been reported. Following focus groups a pool of items was developed based on the SRM and reviewed by 16 expert clinicians and researchers considering: the extent the questions reflected how particular ageing dimensions were defined, the logic of each item considering meaning and readability, and the validity and content coverage of the items in respect to broader ageing literature (Barker et al. 2007). The original measure was piloted with community dwelling adults aged 65 + and reported to have good structural and psychometric properties, and test–retest validity over periods ranging from 7 to 42 days (Barker et al. 2007). Only limited details regarding the conduct of this pilot work is reported with readers directed to the corresponding author for further information. The corresponding author was contacted and did not provide any further information.

Internal consistency of the APQ subscales has been reported in four papers with good internal consistency for domains in most samples (α ranging from 0.52 to 0.89). For the original English version, a 7-factor structure has been reported (Barker et al. 2007). However, later studies have highlighted issues with the 7-factor structure in the English (Sexton et al. 2014), Dutch (Slotman et al. 2017) and French (Ingrand et al. 2012) versions. As a result of perceived issues with the APQ two additional versions of the measure have been created the Brief-APQ (B-APQ) and the Short APQ (APQ-S).

The B-APQ was developed by Sexton et al. (2014), with the aim of reducing respondent burden while continuing to capture ageing perceptions, and has been used in a further seven papers. The B-APQ comprises 17 items categorised into five domains and is reported to have improved model fit while retaining consistency with the SRM and covering key dimensions. Like the original APQ a 5-point Likert scale is used for each item representing responses of strongly disagree to strongly agree and an average score is calculated for each domain. The B-APQ has been translated into Dutch (Slotman et al. 2017) and Persian (Moghadam et al. 2016). The APQ-S was created by Slotman et al. (2017) who were critical of B-APQ for failing to retain the original 7-dimension structure. Alongside translating and validating a Dutch version of the APQ, they created a new shortened version. The 21 item APQ-S was reported to have good fit with the SRM model and while internal consistency and inter-factor correlations were weaker than the original APQ these were still within acceptable levels (Slotman et al. 2017). Test–retest reliability was not reported.

Overall evaluation

Overall, the APQ appears to show reasonable quality. A key strength of this measure is that it is grounded in theory and specifically developed to measure self-perceptions of ageing. The two shorter versions reduce participant burden and have improved model fit, with the B-APQ showing the strongest psychometric properties.

The Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire

Construct

The Attitudes to Ageing Questionnaire (AAQ) was developed by Laidlaw, Power, Schmidt and the WHOQOL-OLD group to measure cross-cultural attitudes to ageing (Laidlaw et al. 2007). Six further studies used it to measure attitudes to ageing, two self-perceptions of ageing, one attitudes towards own ageing and one negative attitudes towards own ageing.

Description

The AAQ comprises three eight item subscales measured on 5-point Likert scales: psychosocial loss, physical change and psychological growth, and/or as a total score. The scale has been used with a number of population groups across several languages including: English, Spanish, Czech, Norwegian, German, Danish, French, Hungarian, Hebrew/Arabic, Japanese, Swedish, Portuguese, Turkish, Lithuanian and Chinese.

The AAQ was reported in 11 papers including the original development paper (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list). All report the use of a one to five Likert scale and, where reported, scale point options are described as ranging from strongly disagree/not true at all to strongly agree/extremely true (Kalfoss et al. 2010; Low et al. 2014; Loi et al. 2015).

Quality

Initial AAQ items were developed though a literature review and focus groups with older adults. Items were then discussed in 15 focus groups with older adults at WHOQOL coordinating centres and a commentary and feedback Delphi exercise was completed with experts at 15 centres worldwide. Initial development resulted in a structure with some items in “general” form (e.g. “to be old is to be sick”) and others in “personal” form (e.g. “I have more energy now than I expected for my age”). Development was conducted across 15 WHOQOL-OLD centres and field testing across 20 WHOQOL-OLD centres worldwide.

Internal consistency for the overall scale score is rarely reported and, because all studies to date have been cross-sectional, no test–retest reliability data is available. When explored using factor analysis, a three-item structure has been confirmed for the Spanish version (Lucas-Carrasco et al. 2013) and was satisfactory for the Norwegian version but was not confirmed in a Canadian sample (Kalfoss et al. 2010).

Overall evaluation

Strengths of the AAQ are the high level of stakeholder involvement in the development and the range of languages the scale is available in. Research could further explore the psychometric properties of the scale. A limitation is that the scale was not originally designed to assess self-directed ageing stereotypes.

The expectations regarding ageing survey

Construct

The Expectations Regarding Ageing (ERA) survey was developed by Sarkisian et al. (2002) in order to measure older adults’ expectations regarding ageing. A further four studies have used it to measure expectations regarding ageing and one to measure positive perceptions about old age.

Description

The ERA is a 38-item instrument with 10 scales: general health, cognitive function, mental health, functional independence, sexual function, pain, sleep, fatigue, urinary incontinence and appearance (Sarkisian et al. 2002). Half of the questions focus on the participants’ own ageing and half assess expectations for older adults in general (Sarkisian et al. 2002). Items are rated on a one to four Likert scale (definitely true-somewhat false). Higher ERA scores suggest that participants expect to maintain physical and mental functioning as they get older whereas low scores suggest expected deterioration in these areas. The 12-item version of the ERA is reported to assess global expectations regarding ageing in addition to three subscales: expectations regarding physical health, expectations regarding mental health and expectations regarding cognitive function (Sarkisian et al. 2005).

The ERA has been used in six studies (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list). Four, including the original development paper, have used the 38-item version. A 12-item version has been developed and reported in two studies (Sarkisian et al. 2005; Yeom 2013a). The ERA has been used with a number of population groups and has been translated into both Spanish (Sarkisian et al. 2005) and Korean (Yeom 2013a).

Quality

The original ERA questions were based on focus groups from an earlier study with 38 community dwelling older adults in which participants were asked to discuss the extent to which a series of vignettes, focussed on ageing issues including forgetfulness, functional decline and wisdom, described changes expected with ageing (Sarkisian et al. 2001). Qualitative content analysis was used to identify domains and cognitive interviewing employed to assess pre-test questions and decide upon the rating scale. Content validity has been checked by asking respondents whether the scale questions addressed issues they felt were (1) important to them and (2) important to their physician, with 68% and 69% rating all or most items as important, respectively (Sarkisian et al. 2002).

Internal consistency for the ERA-38 subscales has ranged from α = .58–.94 with the majority reporting α < .75, while the ERA-12 has internal consistency reported as α= .89 (Sarkisian et al. 2005). Test retest reliability has only been reported for the ERA-38. Assessments were repeated after two weeks and the interclass correlation coefficient was .96 for the total scale score (Sarkisian et al. 2006). The 12-item version appears to have an acceptable 3-factor structure (Sarkisian et al. 2005). However, the original factor structure of the ERA-38 was not confirmed and an alternative ERA-38 structure has been proposed whereby items are split across 6 subscales with 3 measuring “general ageing expectations” and 3 “ageing self-expectations” (Sparks et al. 2013).

Overall evaluation

Strengths of the ERA are that the target group were included in its development and the scale has questions on both participants own ageing and expectations for older adults in general. However, further psychometric testing of the scale with the adapted factor structure is warranted.

The personal experience of ageing scale/age cog

Construct

The Personal Experience of Ageing Scale was developed to measure the construct of personal ageing experience. In research relating to self-directed ageing stereotypes versions of it have been used in two studies to measure negative ageing self-perceptions and in individual studies to measure positive and negative age related cognitions, experience of ageing and positive view on ageing.

Description

The Personal Experience of Ageing Scale uses 12 statements beginning with the phrase “Ageing means to me…” which are rated on a four-point scale (completely true, mostly true, mostly not true, completely not true). There are three subscales consisting of four items each: physical decline, continuous growth and social losses (Steverink et al. 2001).

The personal experience of ageing scale has been reported in five studies (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list). The full original scale has only been used in one paper, other papers have used subscales or modified subscales from the original. The scale was redeveloped by Wurm et al. (2007) creating the “AgeCog” measure.

The original scale items have been produced in English and Dutch (Westerhof et al. 2012), with the physical losses subscale also translated into German (Wurm et al. 2013; Wurm and Benyamini 2014). The later AgeCog subscales have been produced in German (Wurm et al. 2007, 2010).

Quality

Questions for the Personal Experience of Ageing Scale were originally developed by a research group and through qualitative work with older adults conducted by Kohli and Dittmann-Kohli in 1996 (Steverink et al. 2001). Statements referring to positive and negative ageing experiences across several domains including health, social contacts, activities and personality were developed. Item reduction techniques were applied and principal components analysis was used to explore factor solutions resulting in three subscales.

Good internal consistency of the full Personal Experience of Ageing Scale has been reported for the English and Dutch versions, and for the physical decline subscale in the German version. The factor structure of the AgeCog measure has been confirmed with four domains: physical losses, social losses, ongoing development and self-knowledge (Wurm et al. 2007); however, this information is provided as a study endnote and details are very limited.

Overall evaluation

The original scale was not intended to specifically measure self-directed ageing stereotype, information on test–retest reliability is not given and there is a lack of detail given on the AgeCog version of the scale. Therefore, despite evidence of stakeholder involvement in its development and some evidence of its psychometric properties, it may not be best suited to measuring self-directed ageing stereotypes.

The symptom management beliefs questionnaire

Construct

The SMBQ was designed to measure the extent to which older individuals hold negatively stigmatised beliefs about managing physical symptoms. The scale has been used relating to symptom experience/management in two studies to measure ageing stereotyped beliefs, and in single studies to measure ageing related perceptions, negative beliefs and negative/ageist stereotypes.

Description

The SMBQ was developed in an unpublished thesis by Yeom in 2010 (cited in Yeom 2013a). The original SMBQ contained 13 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale with options ranging from “do not agree” to “completely agree” (Yeom and Heidrich 2009). The measure does not contain subscales and a total mean score is created with higher scores representing more negative beliefs about symptom management. The SMBQ is available in Korean and English.

The SMBQ was used in five papers (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list) with one describing three pilot studies (Yeom and Heidrich 2009) and one using replicated data from the first stage of data collection for these three pilot studies (Heidrich et al. 2009).

Quality

The SMBQ items were based on the gerontology literature, interviews with health care professionals working with older adults (Yeom 2013a) and the Wards Barrier Questionnaire which assesses the extent to which patients have concerns about reporting pain and using analgesics (Ward et al. 1998).

Yeom and Heidrich (2009) report reliability and validity testing for the scale detailing content validity as assessed by three adult and geriatric nurse practitioners. Content validity for the Korean version was checked by an expert committee of nursing researchers and health care providers for older adults. Following expert review one item from the English SMBQ was removed due to replicated content (“Healthcare providers will think I am a complainer if I ask about my symptoms”). Clarity and comprehensibility of the 12 item version was checked in a pilot test with 20 older people (Yeom 2013a).

Good internal consistency of the English version has been reported for older adults (Yeom and Heidrich 2009) and for the Korean version (Yeom 2013a, b, 2014). No test–retest reliability checks have been reported for the English version; however, for the Korean version, test–retest was checked with 20 participants over two weeks supporting good test–retest reliability (Yeom 2013a). The factor structure of the scale has not been explored for the English language version but has been completed for the Korean version with three factors confirmed: Ageing stereotypes, pessimistic expectations and good patients’ attitudes (Yeom 2013a).

Overall evaluation

Overall, the SMBQ focusses on a specific area of ageing stereotypes relating to managing physical symptoms and therefore would be unsuitable for use as a general measure of self-directed ageing stereotype. In addition, the psychometric properties of the English language version should be tested further.

The image of ageing scale

Construct

The original image of ageing scale was developed by Levy et al. (2004) to assess positive and negative perceptions people hold about older people. It was adapted to be self-directed and used in three studies to measure self-perceptions of ageing and in one study to measure self-image of ageing.

Description

The original scale consists of 18 items made up of 9 conceptual categories that each contain one positive and one negative item. For example, “appearance: wrinkled, well groomed”. Participants rate how well each word matches their image or picture of old people in general on a zero to 6-point Likert scale, with zero being furthest from what you think to six being closest to what you think. A total score ranging from 0 to 54 is then calculated for both the positive and negative subscales.

Modified versions of the image of ageing scale have been used in four studies to explore self-perceptions of ageing, two in Chinese (Cheng et al. 2012; Bai et al. 2012), one in Spanish (Ramirez and Palacios-Espinosa 2016) and the other in English (Levy et al. 2014a, b).

Quality

Initial item development for the image of ageing scale involved asking people aged over 70 to list the first five words or phrases that come to mind when thinking of an older person. More negative than positive words were generated so in order to create a balanced scale an additional ten older people were asked to list the first five positive words or phrases that come to mind when thinking of an older person. Words and phrases were grouped for similarity and the remaining 250 were rated by ten older people aged over 65 on two five-point scales asking: how characteristic is the word/phrase of older people, and how positive or negative in the word or phrase. The 96 most characteristic and most positive or negative words or phrases were then reviewed by five experts in gerontology and sorted into nine conceptual categories: activity, appearance, cognition, death, dependence, personality, physical health, relationships and will to live. One positive and one negative item from each category was selected to create the scale. These 18 words were used to pilot the scale. Test retest of the scale for older adults after one week was .92 for positive words and .79 for negative words. Internal consistency was a = .84 for positive words and a = .82 for negative words. The authors also report the scale showed good validity (Levy et al. 2004).

Three studies adapted the image of ageing items to direct them towards the self. Two studies did this by asking participant to rate the degree to which the image of ageing scale attributes were characteristic of themselves (Cheng et al. 2012; Levy et al. 2014a) and one asked participants to rate the extent to which the words described a 65-year-old person and drew on stereotype embodiment theory (Levy 2009) to justify how this was a measure of self-stereotyping and internalisation of ageism (Ramirez and Palacios-Espinosa 2016). One study used a zero to six Likert scale (not at all the way I think about myself as an old person–exactly the way I think about myself as an old person) (Levy et al. 2014a, b), one used a zero to six-point Likert scale (completely unlike me—completely like me) (Cheng et al. 2012), and one used a zero to seven Likert scale (not at all characteristic—very characteristic) (Ramirez and Palacios-Espinosa 2016). Two studies produced independent subscale scores for positive and negative words (Cheng et al. 2012; Ramirez and Palacios-Espinosa 2016). The other study produced an overall measure score by reverse-scoring negative items and summing all items in addition to a negative self-perception of ageing score by adding scores from all nine negative items (Levy et al. 2014a, b). Two studies reported good internal consistency scores for the positive and negative subscales.

Bai et al. (2012) adapted the original measure to create a Chinese Self-image of ageing scale (SAIS-C). They modified items of the image of ageing scale based on interviews with Chinese older adults. The final measure consisted of 14 statements, instead of single words, rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Factor analysis of this scale confirmed a five-factor model and the authors reported an acceptable level of internal consistency and test–retest reliability for Chinese older adults.

Overall evaluation

Pilot testing showed positive indicators of the psychometric properties of the original image of ageing scale and there is evidence of reliability in modified versions of the scale. A limitation is that all four studies using adapted versions of the images of ageing scale modified the scale in different ways. Changes to the items and scoring instructions mean that results of studies using these scales are not easily comparable and thorough testing of each version is not currently available.

The ageing stereotypes and exercise scale

Construct

The Ageing Stereotypes and Exercise Scale (ASES) was developed by Chalabaev et al. (2013) to measure endorsement of ageing stereotypes in the exercise domain. It has been used in two further studies to measure ageing stereotypes in the physical activity/exercise domain.

Description

The scale consists of 12 items to assess stereotypes linked to exercise which are rated on a one to seven Likert scale from do not agree at all to totally agree. The scale contains three subscales, which were originally labelled as “psychological barriers”, “benefits of exercise” and “risk of exercise”. All studies were conducted in France; therefore, only a French version of the scale has been used.

The ASES has been used in three studies including the original development study (see Online Resource 1 for full reference list).

Quality

The original ASES questions were developed based on self-efficacy theory and inspired by three existing scales measuring older adults attitudes towards exercise (Chalabaev et al. 2013). Chalabaev et al. (2013) report four studies on the scale development. Study one tested a 30-item scale across five components (positive outcomes, negative outcomes, older adults physical ability, self-efficacy and motivation). Questions were judged by ten students and ten older adults for clarity. Questions used a 7-point Likert scale (do not agree at all-totally agree). The factor structure was then examined and three final factors were labelled: psychological barriers, risks of exercise and benefits of exercise. In study two, the factor structure was examined in a sample of 167 participants aged 14–89 and confirmed the structure being consistent across age groups. Satisfactory internal consistency was reported in this sample. In study three, temporal stability was tested with a sample of 80 younger adults over a 6-week interval; moderate correlations suggested stability over time. In study four, the external validity of the scale was tested by examining the relationship with previously identified correlates of stereotype endorsement. A younger and older sample were recruited and regression analysis confirmed the relationship between the ASES (labelled by the authors as “stereotype endorsement”) and physical self-worth, self-rated health and subjective age in the older sample only. In this sample, acceptable internal consistency of the subscales was also reported for all subscales.

Modifications have been made to the scale in its two subsequent uses. The labels for the rating scale were changed to completely disagree–completely agree and the titles of the subscales differ slightly across studies. One study titled subscales: psychological capacities, benefits of exercise and risks of exercise (Emile et al. 2014), and the other: self-efficacy to participate in physical activity on a regular basis, positive outcomes (benefits) of physical activity for older adults and negative outcomes (risks) of physical activity for older adults (Emile et al. 2015). Internal consistency reported therefore reflects these differing subscale titles. Test–retest reliability and factor structure have not been checked in samples of older adults.

Overall evaluation

A strength of the scale is that it was specifically designed to measure the endorsement of ageing stereotypes. At the time of the search, this scale was only available in French and further testing of the psychometric properties of the scale are needed. The scale is specific to stereotypes relating to exercise, so while it has potential for this domain, it is not suitable as a general measure of self-directed ageing stereotype.

The age-based rejection sensitivity questionnaire (RSQ-Age)

Construct

The RSQ-Age was developed by Kang and Chasteen (2009) to measure individual levels of age-based rejection sensitivity/susceptibility to the negative consequences associated with age stereotypes. It has been used in one further study to measure feelings of age-based stigma.

Description

The RSQ-Age consists of 15 scenarios in which older adults might experience concerns about age-based stigma. For example, “Imagine that you are involved in a minor accident while driving. It is unclear who is at fault”. Participants are asked to rate (a) how concerned/anxious they would feel about rejection in the situation, and (b) how likely/unlikely they judge rejection to be in the situation. Each scenario is rated on a one to six scale (very concerned/likely–to very unlikely/unconcerned). Scores are combined for the ratings and an average product score for each item is produced with a possible score of 1–36 representing low to high rejection sensitivity. This scale has been used in two studies including the original development paper.

Quality

The RSQ-Age was developed based on rejection sensitivity and stigma consciousness theory and was modelled on existing race and personal rejection sensitivity measures. To develop the scenarios for the scale, 47 older adults responded to a request to report a situation that they, a friend or a family member had had a negative experience of related to being an older adult. A pilot test of the 58 scenarios that were generated led to eight domains: workplace/hiring decisions, social exclusions/isolation, obtaining goods or services, feeling like a burden, health, impatience, athletics and interactions with young adults. These items were developed into 30 items for the RSQ-Age and where possible wording was adapted from the existing RSQ-Race measure. Initial testing was conducted with older adults and internal reliability for the 30 items was good. The 30 items were reduced to 15; however, the process for this is not clearly reported. The 15-item version of the scale was tested with two samples showing good internal reliability and test retest reliability and a single-factor structure was confirmed. In a subsequent study, Chasteen et al. (2015) also report good internal consistency for the scale.

Overall evaluation

Overall strengths of the RSQ-Age are that it is theory based, involved older adults in its development and initial testing shows it to have good psychometric properties. The scale would benefit from further use and testing. The key limitation is some ambiguity as to what the scale measures, with the authors giving several slightly different descriptions.

Ages of Me

Construct

The Ages of Me scale was originally developed by Kastenbaum et al. (1972) to investigate the concept of personal age. It has been used in two studies to measure subjective age (Staats et al. 1993; Staats 1996).

Description

The Ages of Me scale consists of four items that ask participants to compare themselves to typical older and younger people in areas such as their appearance and their interests. Ratings are given on a five-point rating scale, with the mid-point indicating that they feel their functional age matches their chronological age and a lower score indicating a youthful bias. Having a “youthful bias” is considered to be positive because it implies that an individual has not internalised the negative stereotypes associated with ageing.

Overall evaluation

No studies reported tests for scale reliability or validity therefore no quality evaluation is available for this scale. Conceptually, the scale appears appropriate as a measure of self-directed ageing stereotype. Future research would need to conduct quality testing to assess the suitability of the scale further.

Future self-views

Construct

The future self-views scale was originally developed by Kornadt and Rothermund (2011) to measure domain-specific age stereotypes. It has been used in one study to measure ageing stereotypes/views of self in old age and in one study to measure future self-views.

Description

The future self-views scale consists of a series of bipolar statements, for example: “conflicts in the relationship with the family—harmonious relationship with the family”. The statements are divided into eight domains: (1) family and partnership (2) friends and acquaintances (3) religion and spirituality (4) leisure activities and social or civic commitment (5) personality and way of living (6) financial situation and dealing with money-related issues (7) work and employment and (8) physical and mental fitness, health and appearance. Participants are asked to rate themselves on each statement using an eight-point scale from positive to negative, with higher scores indicating more positive ratings of oneself as an older person.

The future self-views scale has been used in two studies both conducted in Germany (Kornadt and Rothermund 2012; Voss et al. 2017). One study asked participants to rate the bipolar statements in terms of themselves presently, themselves in the future, and older people generally (Kornadt and Rothermund 2012). The other asked participants to rate the statements considering themselves when they are older.

Quality

Items for the future self-views scale were generated in an interview study with older people (Kornadt and Rothermund 2011). The total and subscale scores are reported to have good internal consistency and an 8-factor structure has been confirmed (Kornadt and Rothermund 2012; Voss et al. 2017).

Overall evaluation

While the scale shows evidence of good psychometric properties, it is unclear if “future self-views” fully assess the internalisation of negative ageing stereotypes.

Measures used in a single study

Construct

Twenty-nine measures were only used in a single study. The scales were used to measure a range of constructs including age attributions, negative age stereotypes, self-other discrepancy and perceived difficulty of life events. As well as subjective age, perceived age versus desired age, age identity and fear of ageing.

Description

Across the 29 measures, the number of questionnaire items range from single questions to 110 items. Most employed a Likert format; however, total scores and true or false formats have also been used. Survey structure ranged from single structure formats up to 11 subscales.

Several studies assessed ageing self-stereotype with a measure of subjective age. The simplest measures involved comparing participants’ ratings of how old they feel with their chronological age (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al. 2008; Kotter-Gruhn et al. 2009; Kotter-Gruhn and Hess 2012; Westerhof et al. 2012; Chalabaev et al. 2013). For example, Westerhof et al. (2012) measured age identity with the following single item “Many people feel older or younger than they actually are. What age do you feel most of the time?”. The difference between chronological age and subjective age is then used as a measure of youthful age identity. Other studies used more in-depth approaches where participants rated their current and future selves on a range of life domains (Cheng et al. 2009; Kornadt and Rothermund 2012).

A large portion of the scales aimed to measure participants’ ageing stereotypes and the extent to which participants’ felt these applied to themselves (e.g. Preston and Gudiksen 1966; Ahammer and Bennett 1977; Schulz and Fritz 1987; Sijuwade 1991). For example, Levy et al. (2012b) measured participants’ endorsement of ageing stereotypes with a subscale of the Attitudes Towards Older People scale (ATOP) (Tuckman and Lorge 1953). They then assessed how self-relevant participants thought they were by asking the question “At what age does someone become old?” and then comparing this with participants’ actual age. Age stereotypes were classed as being self-relevant if their actual age was older than the age they stated someone becomes old. Levy (1999) measured “inner” and “outer” selves to asses ageing self-stereotype. “Inner” was assessed by asking participants “When you think about yourself, what are the first five words or phrases that come to mind? Who are you?” and “Outer” by asking “When you think of an old person, what are the first five words or phrases that come to mind?”. Responses were then rated on positivity and the outer positivity score subtracted from the inner one.

Quality

It is difficult to assess the quality of the measures because none of the studies provided a full quality assessment of the scale, although for some of the simpler scales this would not be applicable. Internal consistency assessments are reported for 14 scales; test–retest reliability is reported for one scale and factor structure has been reported for four scales. Only five papers detail how scale items were developed. Full details and quality indicators for the individual scales can be found in Table 2.

Of concern is the finding that several of the scales did not appear to be measuring ageing self-stereotype. Minnes et al. (2007) measured self-perceived adverse age changes with items including, “As I get older, it is harder for me to get through the day” to assess the extent to which older adults believed they had been affected adversely by their own ageing. Other studies used measures focussed on fear and anxiety about ageing (Chasteen 2000; Lynch 2000; Chasteen et al. 2015). While it can be argued that these concepts are related to self-directed ageing stereotype, they are not direct measures of it.

Overall evaluation

Measurement of subjective age or assessment of age stereotypes that are then compared to how older adults feel about themselves appear promising but further testing of the reliability and validity of such measures is needed.

Discussion

In order to meet the needs of the rapidly ageing population (Coates et al. 2019), research is needed to explore the experiences of older adults. It has been highlighted that internalisation of negative ageing stereotypes may have a detrimental effect on both the physical and mental health of adults (e.g. Molden and Maxfield 2017; Stewart et al. 2016) and that research is needed to further explore the impact of self-directed ageing stereotypes. In order to do this, assessment of how authors have defined and measured this concept in the existing literature was needed. Therefore, the current systematic review set out to identify and describe tools, proposed by authors, to measure self-directed ageing stereotype in older adults and to evaluate the quality of these measures in order to make recommendations on the best tools to use. It also set out to identify the broad range of terms used to refer to the concept of self-directed ageing stereotype and to suggest the use of a universal term and definition.

The first aim, to identify and describe the tools measuring self-directed ageing stereotype in older adults was met. Forty scales purporting to measure constructs relating to self-directed ageing stereotype were identified. However, the majority of these were developed and used in a single study. This wide variety of measures means that it is difficult to compare outcomes of studies assessing self-directed ageing stereotype, which hinders knowledge in this area from moving forwards.

The second aim was to evaluate the quality of these measures. The review indicated that quality for the majority of scales was not clearly reported and authors frequently modified and amended scales without explaining the processes and rationale. Internal consistency was the most commonly reported quality check for measures of this type. However, when reported, outcomes appear to be variable and frequently not consistent for scales used across different languages. Test–retest reliability and tests for factor structure were often poorly reported and rarely replicated in studies using measures after initial development. Furthermore, construct validity can only be judged for a small number of measures because approaches to the development of items for scales are under reported. Therefore, the majority of scales identified in this review have an insufficient level of quality assessment criteria for firm conclusions about their suitability for assessing self-directed stereotype to be drawn.

In particular, this review raises concerns about the frequent use of the ATOA. Despite being the most commonly cited measure of self-directed ageing stereotype in older adults, the ATOA subscale of the PGCMS was not originally designed to measure this construct and inspecting the five items it is not clear that all items are in fact measuring self-directed ageing stereotype. Furthermore, findings of studies using the ATOA are not easily comparable given the modifications to the scale that authors have made, which also makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the reliability and validity of the scale. Therefore, despite evidence for the internal consistency and single-factor structure, the ATOA is not recommended as a measure of self-directed ageing self-stereotype.

When considering the strengths of other scales, the WHO AAQ scale, while not widely used, is the most rigorously developed and available in the most languages. However, it was developed for the purpose of measuring cross cultural attitudes towards ageing and therefore may not be specific to measuring self-directed ageing stereotypes. It is likely that ageing stereotypes and perceptions are culturally specific (Moscovici 1988) and therefore measures should take this into account when comparing across cultural groups. The Ageing Perceptions Scale, which is based on the ATOA, appears promising. It was specifically developed to measure self-perceptions of ageing and demonstrates reasonable psychometric properties particularly for its shortened version (B-APQ). This scale would benefit from further use and testing but is at present the most suitable tool for assessment of self-directed ageing stereotype.

The Ages of Me and ERA scales, along with several of the measures used in a single study, assess ageing stereotypes held by older adults and how they feel about themselves. These types of scales are promising because theoretically this uncovers the extent to which an individual has “internalised” ageing stereotypes. Research could compare simple measures that ask “how old are you” and “how old do you feel” with multiple-item scales (e.g. Gardner et al. 1998). If comparable, short measures with reduced participant burden could be used where general measures of self-directed ageing stereotype are required, and multiple-item scales where more nuanced information is required. Similarly, scales such as the ASES could be psychometrically tested further and used for research into specific aspects of self-directed ageing stereotypes.

The third aim of the research was to propose a universal term and definition for the concept of internalised ageing self-stereotype. In order to do this, the terminology used to represent the construct being assess by each measure was explored. There is wide variability in the terminology used across studies, with at least 25 different terms used for the construct, meaning that study outcomes cannot be usefully compared. Furthermore, only a small number of the terms used included the word “stereotype”, which is surprising given the underlying construct they sought to measure. The use of a universal term in future research will facilitate development of knowledge in this area and the term “self-directed ageing stereotype” is recommended and should be defined as “the internalisation and self-direction of cultural beliefs and attitudes regarding ageing”. Such beliefs and attitudes can be positive or negative and relate to various aspects of the ageing process. This definition is in line with stereotype embodiment theory which proposes that exposure to cultural stereotypes throughout the lifespan can lead to self-definitions that, often unconsciously, influence functioning and health (Levy 2009).

The findings from the current review, along with Faudzi et al.’s (2019) review of self-report measures of attitudes towards ageing in younger adults, provide comprehensive information on the psychometric properties of a broad range of scales relevant to ageing research. They identify the best of the currently available measures, but both highlight the need for further high-quality research to fully test the psychometric properties of these scales. The current review also highlights the importance of researchers considering the context that scales are used in. Certain scales were not originally intended to measure self-directed ageing stereotypes but have been operationalised in ways to achieve this. Researchers should carefully consider whether scales are appropriate for their measurement needs and check the relevant psychometric properties of their chosen scale (Myers and Winters 2002).

Strengths and limitations of this review

This review was required to provide clarity on the assessment of self-directed ageing stereotype. A challenge when completing the review was the definition of the concept and a decision was made to select papers based on author assertion that self-directed ageing stereotype was being assessed. This could be viewed as a limitation as the authors assertion may not be a strong justification; however, by making this assertion, the authors’ work will be read as a contributor to the literature in this area. This review has illustrated that tools selected by authors are not always effective for this purpose, and therefore, it is important that readers critically assess the tools used before applying the findings of these studies.

This review has been limited to only studies published in the English language and available within peer reviewed journals. It is possible that further tools measuring this concept exist in papers published in languages other than English and within the grey literature.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there has been a lack of consistency regarding terms used to refer to self-directed ageing stereotype. Furthermore, participant ratings of ageing stereotypes applied to older adults in general are often claimed to measure self-directed ageing stereotype without consideration of whether these beliefs and attitudes are internalised by the individual. The use of a universal term in future research will facilitate development of knowledge in this area and the term “self-directed ageing stereotype” is recommended. There is no clear picture as to which is the best tool for assessing this construct; however, the B-APQ appears to hold most promise and warrants further testing. In order for the field of ageing research to move forwards, suitable psychometrically sound measures must be identified and used.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

This research was supported by an internal Staffordshire University research grant.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note