Abstract

Bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) are bacterial organelles involved in enzymatic processes, such as carbon fixation, choline, ethanolamine and propanediol degradation, and others. Formed of a semi‐permeable protein shell and an enzymatic core, they can enhance enzyme performance and protect the cell from harmful intermediates. With the ability to encapsulate non‐native enzymes, BMCs show high potential for applied use. For this goal, a detailed look into shell form variability is significant to predict shell adaptability. Here we present four novel 3D cryo‐EM maps of recombinant Klebsiella pneumoniae GRM2 BMC shell particles with the resolution in range of 9 to 22 Å and nine novel 2D classes corresponding to discrete BMC shell forms. These structures reveal icosahedral, elongated, oblate, multi‐layered and polyhedral traits of BMCs, indicating considerable variation in size and form as well as adaptability during shell formation processes.

Keywords: bacterial microcompartments, cryo‐EM, GRM2, Klebsiella pneumoniae

Abbreviations

- BDP

BMC shell‐derived particle

- BMC

bacterial microcompartment

- cryo‐EM

cryogenic electron microscopy

- CutC

choline trimethylamine lyase

- CutO

alcohol dehydrogenase

- GRM2

glycyl radical enzyme‐associated microcompartment group 2

- TMA

trimethylamine

1. INTRODUCTION

Bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) are structures with diverse functions and intricate organization involved in mediation of various enzymatic reactions. 1 , 2 BMCs are usually around 100–200 nm in diameter, generally consisting of a semi‐permeable protein shell and an enzyme core. 3 , 4 They can be compared to eukaryotic organelles, often giving bacteria an advantage to survive and thrive in specific conditions. 5 , 6 Recent efforts in determining prevalence of BMCs have found BMC loci to be present in around 25% of all sequenced bacterial genomes, dispersed over 23 phyla. 7 , 8

Compartmentalization of certain enzymatic processes in BMCs provide several advantages – sequestering reactions with toxic and/or volatile intermediates from cytosol can both protect the cell from damage and enhance productivity by preventing unwanted side reactions as well as increasing the local substrate concentrations. 9 BMCs most notably differ in the composition of their enzymatic core, which generally consists of one or multiple signature enzymes mediating the specific reaction and several ancillary enzymes responsible for maintaining the cofactor pool inside the compartment – usually alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase and phosphotransacylase. 10 The best described BMCs are carboxysomes. They are the only BMCs involved in anabolic reactions, enabling carbon fixation in cyanobacteria and some chemoautotrophic bacteria. 4 , 11 All other known BMCs form the subgroup of catabolic metabolosomes that enable or alleviate breakdown of various organic compounds, such as ethanolamine, 12 , 13 propanediol, 13 , 14 choline, 14 , 15 ethanol, 16 and fucose/rhamnose. 17 , 18 It has been suggested that use of metabolosomes can promote niche expansion of bacteria (especially pathogens) due to enabled use of alternative carbon substrates. 9 , 19 Despite the quasi‐icosahedral structural architecture resembling viral capsids, no similarity between BMC shell and viral coat proteins has been observed. Instead, BMC proteins most likely have evolved from conserved cellular proteins. 20 The conserved composition of BMCs and their high prevalence across bacterial phyla is presumably attributed to horizontal gene transfer, 21 resulting in similar BMCs in distantly related bacteria.

One of the most notable morphological characteristics of BMCs is the highly organized and geometric structure with semi‐icosahedral or polyhedral protein shell. 22 The protein shell has selective permeability properties and is in some ways analogical to phospholipid membranes, but differs in the opposite preference of allowing the passage of polar molecules. 23 , 24 In contrast to the vast diversity of potential core enzymes, composition of the BMC shell is relatively conserved, constituting several thousand copies of three types of shell proteins: BMC‐H, BMC‐T, and BMC‐P. 25 , 26

BMC‐H proteins are found in all BMC shells. They contain a single Pfam00936 or BMC domain, forming homohexamers with a constitutively open pore in the center. 5 In absence of other shell proteins, BMC‐H have shown ability to form flat sheets that can be used as building blocks for BMC facets. 27 , 28 BMC‐T proteins are somewhat similar to BMC‐H, but their monomers consist of two fused Pfam00936 domains, forming pseudo hexameric trimers that closely resemble BMC‐H hexamers. 29 , 30 These proteins also have a central pore up to 14 Å in diameter. BMC‐T trimers can also dimerize across their so‐called concave sides directed toward outside side of the shell layer, forming a double trimer BMC‐TD with an inner chamber in between the two layers. 9 , 31 These two formations are often described as two distinct subtypes: BMC‐TS and BMC‐TD in most cases due to their different roles in shell permeability. The pores of double‐stacked BMC‐TDs have been observed in open and closed, as well as partially open states. The corresponding conformational changes can be induced by various ligands, including metal ions 32 and enzymatic substrates, 33 indicating their significant role in regulating metabolite flow across the shell. 34 , 35 Nonetheless, the individual roles of BMC‐H and BMC‐T in metabolite flow regulation are still under debate.

Together, BMC‐H, BMC‐TS, and BMC‐TD form the facets of the shells and can be interchanged with each other in this regard. The last group of shell proteins, BMC‐Ps, form pentamers that cap the vertices of the BMC shell. 36 They contain a Pfam03319 domain and are sometimes also called BMVs to emphasize the difference from BMC protein family. 37 BMC‐P proteins also have a constitutively open central pore that is lined by positively charged side chains, but it varies in size among different types of BMCs. 38 These proteins in the shell are in much lower numbers than others, since only 12 BMC‐P pentamers are necessary to cap an icosahedral shell. However, the presence of BMC‐Ps is essential for obtaining a fully sealed microcompartment. 39

During assembly of functional BMCs, another crucial step is encapsulation of core enzymes. This is typically achieved by use of encapsulation peptides (EPs) 40 , 41 , 42 that are considered to be involved in both enzymatic core aggregation 2 , 43 and its interactions with microcompartment shell. 44 , 45 Exact mechanisms of BMC assembly are still under debate, with concomitant core and shell assembly 43 , 46 or core‐first assembly 4 , 44 , 47 as two possible scenarios.

Glycyl radical enzyme‐associated microcompartment group 2 (GRM2) is one of the six most widespread GRM groups of BMCs. 48 Members of GMR2 group include BMCs with choline trimethylamine lyase (CutC) as their signature enzyme, mediating the conversion of choline into trimethylamine (TMA) and acetaldehyde. 14 , 49 , 50 GRM2 BMC locus contains the genes encoding signature enzyme CutC, its activating enzyme CutD, as well as ancillary core enzymes, shell proteins, and transport and regulatory proteins. 51 The absence of BMC‐T protein genes is the most notable GRM2 trait shared by few other types of BMC loci 7 , 8 , 51 This brings the total number of shell GRM2 proteins to five, including four types of BMC‐H and one type of BMC‐P.

The ability of BMCs to enhance the productivity and speed of enzymatic reactions opens potential for biotechnological applications—they could serve as “internal factories” inside bacteria, producing desired compounds in a more effective manner. In multiple studies, whole BMC operon transfer has resulted in native and fully functional BMC production, 52 , 53 , 54 but it is also possible to repurpose the BMC shell for entirely new applications. 55 Detailed analysis of BMC characteristics, including their formation, shell properties, flexibility, and variability of size are important factors in potential downstream re‐purposing.

A previous investigation by our group 56 revealed the structure of pT = 4 particles via near‐atomic resolution cryo‐EM model. BMCs both extracted from native bacteria 15 , 17 , 57 and, using recombinant production, 58 , 59 , 60 have also been analyzed in previous studies. The recombinant particles have been largely conserved in their morphology, but have a large range in size, with recombinantly produced (and in many cases empty) BMC particles being much smaller than native BMCs. For example, previously reported structure of recombinantly produced Klebsiella pneumoniae GRM2 type BMCs revealed a particle around 250 Å in diameter, 56 tenfold smaller than the projected size for native BMCs. We also identified some larger particle types, but the characterization of these particular subspecies lacked depth. Our goal in this study was to analyze these larger particles closer in size to their native counterparts with cryo‐EM, while also observing their potential variations.

2. RESULTS

The sample selected for cryo‐EM analysis contained recombinantly expressed K. pneumoniae GRM2‐like particles encapsulating signature enzyme choline lyase (CutC) and one of ancillary core enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase (CutO). We called these produced particles BMC shell‐derived particles (BDPs) due to having only a partial core and an incomplete set of shell proteins. 4 of 5 shell proteins were used for shell production, expressing the BMC‐P protein cmcD and three BMC‐H proteins‐ cmcA, cmcB and a mutant cmcC (for distinction noted as cmcC'). Notably, cmcC' contains a C‐terminal elongation of eight residues that facilitates the production of recombinant BDPs. 56

Previous work with K. pneumoniae BDPs has shown that the recombinantly produced particles are not uniform in size forming a single peak but are instead spread between the 60 and 104 ml in gel filtration purification. The size distribution of these particles varied from 200 nm in the 66 ml fraction down to 25 nm large particles in the 96 ml fractions. 56 SDS‐PAGE analysis of purified BDPs confirmed successful encapsulation of CutC and CutO in BDPs of all sizes (Figure S1(a)), selecting 70–84 ml fractions as potential samples for cryo‐EM. Gel densitometry analysis of the fractions used for cryo‐EM analysis revealed only approximately one copy of each enzyme to be encapsulated in BDPs when particle size is averaged as the most abundant pT = 4 type (Figure S1(b), Dataset S1). When the presence of larger particles is also taken into account, this ratio drops even lower and the presence of considerable number of empty particles can be assumed. After negative staining transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of prospective samples (Figure S2), 76–79 ml fractions were selected for cryo‐EM analysis.

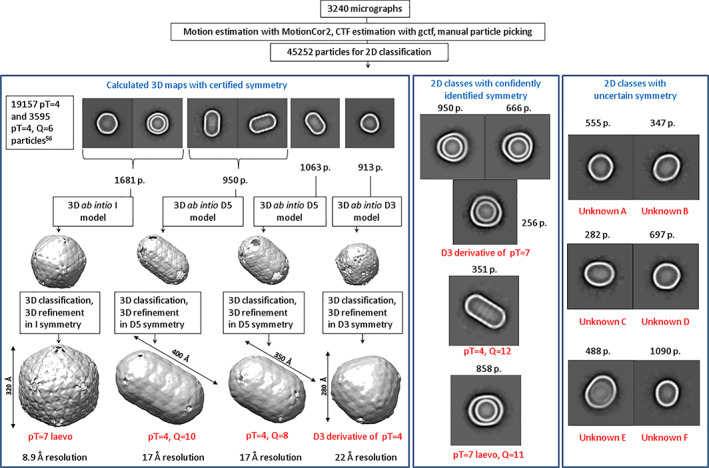

Cryo‐EM analysis revealed significant variation in particle form, and we could confidently identify nine distinct types of BDPs with known symmetry (Figure 1). Out of these nine structures, 3D maps with sufficiently high level of details for hexameric and pentameric subunit identification could be calculated for six of them, allowing to confidently identify particle symmetry. We used the particle naming according to accepted practice used for viral capsids, with T representing triangulation number and Q representing elongation number for prolate particles. 61 Since better 3D maps were already previously reported for pT = 4 and pT = 4, Q = 6 forms, 56 we will not discuss the features of these already known particles in much detail. We were able to calculate novel 3D maps and verify the symmetries by a visual inspection of pentameric and hexameric subunits for a larger, 320 Å pT = 7 laevo BDP form, two elongated pT = 4, Q = 8 and pT = 4, Q = 10 forms and triangular D3‐symmetric polyhedral particles presumably derived from pT = 4 particles. Judging from the size and the shape of several other 2D classes and comparing them with other 2D classes used for 3D map calculations, we could also identify with high confidence 2D classes matching elongated pT = 4, Q = 12 form, pT = 7 laevo, Q = 11 form and triangular D3‐symmetric polyhedral particle form derived from pT = 7. Because of their unusual form and origin, these triangular particles do not conform to rules of icosahedral particle connotation, so we named them referring to their point group symmetry.

FIGURE 1.

Cryo‐EM classification and identification of BDPs. Text box in the top left of the left panel refers to previously described pT = 4 and pT = 4, Q = 6 BDP forms present in our sample but not analyzed closer in this study

Curiously, we also identified several minor BDP 2D classes for whom we were not able to pinpoint the exact symmetry with high confidence (Figure 1) or calculate 3D maps with sufficiently high resolution to resolve the hexameric and pentameric subunits. Unknown A and Unknown B classes are reminiscent of T7 icosahedrons flattened along one or two five‐fold axes. Unknown C is reminiscent of pT = 4, Q = 6 particle with its surface asymmetrically extended and somewhat rounded with unclear underlying principles. Unknown D and Unknown E are reminiscent of larger, pT = 7 and pT = 7, Q = 11 particles similarly extended by the same unknown principle as 2C. Unknown F particles are the most unusual—they are egg‐shaped and may be a fusion of two BDPs with different quasi‐icosahedral symmetries. Such hybrid fusions appear to be more prevalent with the increase of BDP size, as visible in Figure 2—the largest particles, like native metabolosomes, are almost universally asymmetric.

FIGURE 2.

Exemplary micrographs of larger asymmetric BDPs formed by the higher order polyhedral fusions (marked with an arrow)

Another interesting trait observed for larger BDPs is the formation of multi‐layered particles, as can be judged from 2D classes of pT = 7 and pT = 7 derived particles (Figure 1). For example, more than 40% of pT = 7 laevo BDPs contain an encapsulated separate pT = 4 BDP. The case is similar for D3‐symmetric polyhedral particles derived from pT = 7, which also contain encapsulated separate pT = 4 BDP. It could be possible that the formation of such multi‐layered particles is a result of the different charges of outside and inside facets of hexameric units—the inside facet being charged more positively than the outside facet. 56

3. DISCUSSION

As the preliminary TEM analysis had suggested, BDPs in the analyzed cryo‐EM sample had large variety in form and revealed some features previously unseen among any BMC shells. One somewhat unexpected observed trait was the presence of multi‐layered BDPs, resembling stacking dolls. Observation of such particles raises questions about their formation. It could be possible that the overexpression of shell proteins, when recombinantly producing BDPs, could promote formation of double‐stacked BDPs. In conditions with large surplus of shell proteins, smaller particles may essentially serve the role of the enzymatic core, initiating the formation of another shell around it. Somewhat similarly, multi‐layered BMC shell formations have been observed in another case when expressing an incomplete Pdu BMC gene set pduA‐B‐J. 60 Still, despite their intriguing appearance, the formation of these particles is most likely due to the artificial expression conditions and has no biological relevance.

Even the largest BDPs observed in our sample—around 50–60 nm for the largest asymmetric particles—are still two to five times smaller than reported native sized GRM2 BMCs (100–200 nm). 15 , 61 As metabolosome formation is predicted to start with the assembly of enzymatic core, insufficient amounts of core enzymes or their complete absence could dramatically impact principles of formation for non‐native BMCs. In negative staining TEM analysis larger BDPs were observed in large aggregates, possibly indicating their collapse during sample preparation (Figure S2). With a smaller or non‐existent enzyme core, large size particles may be less stable and particularly prone to collapse. Furthermore, recent analysis of imaging technique effect to apparent BMC size may present additional aspects promoting the collapse of larger particles. 62 This was observed for larger empty GRM2 derived shell particles analyzed by our study as well.

Our data demonstrates that the likelihood to observe perfectly icosahedral particles beyond pT = 7 drops considerably. Although previously some recombinantly produced particles have showed larger pT = 9 symmetry, 58 the presence of BMC‐T proteins that are lacking in GRM2 BMCs may have an impact on shell formation mechanics to result in the formation of slightly larger and more uniform particle material. As the BDP size increases, our observed particles become more and more asymmetric polyhedral fusions. It could be possible that the formation of such particles is nucleated at several points simultaneously, and the complete shell is formed as a result of colliding particles of various types. In such conditions perfectly icosahedral particles with increasing size would be more and more unlikely to form. These conclusions are somewhat concurrent with data about native BMCs—while, for example native carboxysomes conform to quasi‐icosahedral symmetry well enough for T number determination, 63 this is not the case for much more asymmetric metabolosomes. 15 , 57 , 64

Our data illustrates that the smallest form of GRM2 type BDPs is pT = 4, and the shell generally can be enlarged in three modes: elongation along five‐fold axis, polyhedral fusion, and icosahedral enlargement (Figure 3). The elongated particles are formed by adding extra hexamer rings to pT = 4 particles, elongating the particles along five‐fold axis. The formation of these elongated particles could be caused by various local ratios of pentamers and hexamers—with too many hexamers and/or too few pentamers, elongated particles are formed to utilize the excess hexamers. That could explain the observed correlation between the number of hexamer rings in the particle and their population, with diminishing populations of longer particles, since less and less hexameric components are left available for further elongation.

FIGURE 3.

Variability and relations of the BDP subspecies

We can also speculate that, in addition to icosahedral particle elongation, the opposite process of icosahedral particle flattening is also possible—some 2D classes of unknown BDP types could be oblate icosahedral particles. Our data about these unknown classes also suggests that other shell formation types beyond icosahedral enlargement, particle elongation or polyhedral fusion of smaller particles into larger particles may be possible. However, analysis of much larger amounts of particles from the unknown 2D classes required for asymmetric 3D map calculations would be required for this.

Overall, this cryo‐EM particle analysis has indicated the possibility of fluid and adaptable particle formation from the K. pneumoniae GRM2 BMC shell and expanded the known diversity of GRM2 type BDP forms.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Protein expression and purification

BMC shell particles were produced using BL21‐DE3 chemically competent cells (Sigma‐Aldrich, cat. No CMC0014), transformed with a pETDuet‐1 plasmid for shell protein cmcABC'D expression and pRSFDuet‐1 plasmid for core enzyme CutC and CutO expression. Protein expression and purification was generally performed the same as in Kalnins et al. 56 Protein amount for densitometry analysis was determined with UV absorption for CutC and CutO samples and with Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Invitrogen) for BDP sample.

Cells were grown in 2xTY medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml kanamycin at +37°C and shaken at 200 rpm until OD540 0.7. Cell suspension was then cooled to +20°C and induced with 1 mM IPTG. Production continued overnight at +20°C while shaking at 200 rpm. After approx. 16 h the biomass was collected by centrifugation and stored at −20°C until purification.

Cells were lysed with buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM Tris‐NaCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X‐100, 2 mg/ml lysozyme and 0.1 mg/ml DNase. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (about 5 ml buffer to 1 g cells) and incubated for 1 h at +4°C while shaking, then centrifuged for 10 min at 8000 g. The supernatant was then collected and centrifuged at ~50,000 g for 3 h. Ultracentrifugation pellet was resuspended in 300 mM NaCl and 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) buffer (usually 3–5 ml per 5 g of cell mass) and suspension was then centrifuged for 10 min at 11,000 g. Supernatant was then collected and purified using 16/900 Superose 6 gel filtration column equilibrated with the same buffer solution. With 2 ml fractions collected, fractions 30–60 collected and analyzed with 15% SDS‐PAGE and TEM.

4.2. Negative staining TEM analysis

BDPs were visualized with TEM, using uranyl acetate negative staining. 5 μl of sample was placed on TEM 200 copper grids (Sigma‐Aldrich) and incubated for 3 min. Grids were then blotted, briefly washed in 1 mM EDTA solution, blotted again and stained with 5 μl of 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min. The grids were then dried and analyzed on a JEM‐1230 TEM electron microscope at 100 kV.

4.3. Cryo‐EM sample preparation and data collection

A 4 μl of BDP sample with concentration of 1 mg/ml was applied to an EM grid (Quantifoil, Cu grids, 200 mesh, R2/1). Grids were blotted for 4 s at +18°C and 100% humidity using Vitrobot (Mark IV, Thermo Fisher), plunge‐frozen in liquid ethane‐propane and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Data were collected with a 200 kV Talos Arctica microscope equipped with Falcon 3EC detector (both Thermo Scientific). A total of 3240 images were collected, using EPU software (Thermo Scientific), with magnification of 120,000× (pixel size 1.22 Åpx−1) and defocus ranging from −0.7 to −3.0 μm. The exposure time per movie stack was 1.0 s and the overall dose was 40 e/Å2. Each movie stack consisted of 40 frames.

4.4. Cryo‐EM data processing and model building

Movies collected were motion‐corrected and dose‐weighed using MotionCor2, 65 and CTF correction was performed using Gctf. 66 Single particle analysis was performed using RELION 3.0 pipeline. 67 Due to considerable heterogeneity, the analyzed particles were mostly selected with manual picking, resulting in a total number of 45,252 particles. 2D classification produced 22 classes that were analyzed further, amounting to 33,758 particles in total. Six types of 2D classes could be successfully used for de novo 3D model generation in either I1, D3 or D5 point group symmetry and subsequent 3D classification and 3D refinement steps (see Figure 1). The resolution of these maps was ranging from 8.9 to 22.18 Å. Resolution for all final 3D refinements was estimated using the 0.143 cut‐off criterion with gold‐standard Fourier shell correlation between two independently refined half‐maps. 3D map processing data are given in Table S1. A representative cryo‐EM micrograph is included as Figure S3.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Eva Cesle: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; validation; writing‐original draft; writing‐review & editing. Anatolij Filimonenko: Investigation. Kaspars Tars: Writing‐original draft; writing‐review & editing. Gints Kalnins: Data curation; investigation; methodology; resources; supervision; validation; visualization; writing‐original draft; writing‐review & editing.

Supporting information

Figure S1: Cryo‐EM sample analysis. CmcABC' + D + CutC + CutO BDP purification, sample selection and enzyme quantification. A. Gel filtration of BDPs using Superose 6 16/900 GL and fraction analysis in SDS‐PAGE. Fractions selected for cryo‐EM analysis higlighted in gel filtration graph. B. Gel densitometry analysis of selected BDP fractions. 1–76‐79 mL concentrated fractions, bands of CutC and CutO used in analysis highlighted, 2–7– CutC standard curve samples, 8–2– CutO standard curve samples. Analysis performed with ImageJ software.

Figure S2: Negative staining TEM analysis of Superose 6 gel filtration purification of fractions of CmcABC' + D + CutC + CutO BDPs. Fractions correspond to the previous figure.

Figure S3: A representative Cryo‐EM micrograph of BDPs.

Table S1: Cryo‐EM data collection, refinement and validation statistics.

Appendix S1: Supplementary Dataset 1 with calculations of gel densitometry analysis is included. All cryo‐EM 3D reconstruction maps are available in Electron Microscopy Data Bank repository as EMD‐12252, EMD‐12253, EMD‐12254 and EMD‐12255 entries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by ERDF post doc project 1.1.1.2/VIAA/4/20/705. Eva Emilija Cesle was supported by University of Latvia Foundation (Latvijas Universitātes Fonds) with the Doctoral scholarship in the field of exact and medical sciences. We acknowledge Cryo‐electron Microscopy and Tomography Core Facility of CIISB, Instruct‐CZ Centre supported by MEYS CR (LM2018127).

Cesle EE, Filimonenko A, Tars K, Kalnins G. Variety of size and form of GRM2 bacterial microcompartment particles. Protein Science. 2021;30:1035–1043. 10.1002/pro.4069

Funding information Czech Infrastructure for Integrative Structural Biology, MEYS CR, Grant/Award Number: LM2018127; European Regional Development Fund, Grant/Award Number: 1.1.1.2/VIAA/4/20/705; Latvijas Universitātes Fonds

REFERENCES

- 1. Cheng S, Liu Y, Crowley CS, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Bacterial microcompartments: Their properties and paradoxes. Bioessays. 2008;30:1084–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kerfeld CA, Erbilgin O. Bacterial microcompartments and the modular construction of microbial metabolism. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee MJ, Palmer DJ, Warren MJ. Biotechnological advances in bacterial microcompartment technology. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:325–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kerfeld CA, Melnicki MR. Assembly, function and evolution of cyanobacterial carboxysomes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;31:66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kerfeld CA. Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles. Science. 2005;309:936–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chowdhury C, Sinha S, Chun S, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Diverse bacterial microcompartment organelles. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78:438–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Axen SD, Erbilgin O, Kerfeld CA. A taxonomy of bacterial microcompartment loci constructed by a novel scoring method. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jorda J, Lopez D, Wheatley NM, Yeates TO. Using comparative genomics to uncover new kinds of protein‐based metabolic organelles in bacteria: Bacterial microcompartments. Protein Sci. 2013;22:179–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerfeld CA, Aussignargues C, Zarzycki J, Cai F, Sutter M. Bacterial microcompartments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:277–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Protein‐based organelles in bacteria: Carboxysomes and related microcompartments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Turmo A, Gonzalez‐Esquer CR, Kerfeld CA. Carboxysomes: Metabolic modules for CO2 fixation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2017;364:fnx176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kofoid E, Rappleye C, Stojiljkovic I, Roth J. The 17‐gene ethanolamine (eut) operon of salmonella typhimurium encodes five homologues of carboxysome shell proteins. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5317–5329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Held M, Quin MB, Schmidt‐Dannert C. Eut bacterial microcompartments: Insights into their function, structure, and bioengineering applications. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;23:308–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Craciun S, Balskus EP. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:21307–21312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herring TI, Harris TN, Chowdhury C, Mohanty SK, Bobik TA. A bacterial microcompartment is used for choline fermentation by Escherichia coli 536. J Bacteriol. 2018;200:4–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heldt D, Frank S, Seyedarabi A, et al. Structure of a trimeric bacterial microcompartment shell protein, EtuB, associated with ethanol utilization in Clostridium kluyveri . Biochem J. 2009;423:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Petit E, LaTouf WG, Coppi MV, et al. Involvement of a bacterial microcompartment in the metabolism of fucose and rhamnose by clostridium phytofermentans. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Erbilgin O, McDonald KL, Kerfeld CA. Characterization of a planctomycetal organelle: A novel bacterial microcompartment for the aerobic degradation of plant saccharides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:2193–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greening C, Lithgow T. Formation and function of bacterial organelles. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krupovic M, Koonin EV. Cellular origin of the viral capsid‐like bacterial microcompartments. Biol Direct. 2017;12:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. AbdulRahman F. The distribution of polyhedral bacterial microcompartments suggests frequent horizontal transfer and operon reassembly. J Phylogenet Evol Biol. 2013;1:4. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yeates TO, Crowley CS, Tanaka S. Bacterial microcompartment organelles: Protein shell structure and evolution. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:185–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. Bacterial microcompartments. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chowdhury C, Chun S, Pang A, et al. Selective molecular transport through the protein shell of a bacterial microcompartment organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:2990–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yeates TO, Jorda J, Bobik TA. The shells of BMC‐type microcompartment organelles in bacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;23:290–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bobik TA, Lehman BP, Yeates TO. Bacterial microcompartments: Widespread prokaryotic organelles for isolation and optimization of metabolic pathways. Mol Microbiol. 2015;98:193–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutter M, Faulkner M, Aussignargues C, et al. Visualization of bacterial microcompartment facet assembly using high‐speed atomic force microscopy. Nano Lett. 2016;16:1590–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lassila JK, Bernstein SL, Kinney JN, Axen SD, Kerfeld CA. Assembly of robust bacterial microcompartment shells using building blocks from an organelle of unknown function. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2217–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cai F, Sutter M, Cameron JC, Stanley DN, Kinney JN, Kerfeld CA. The structure of CcmP, a tandem bacterial microcompartment domain protein from the β‐carboxysome, forms a subcompartment within a microcompartment. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:16055–16063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mallette E, Kimber MS. A complete structural inventory of the mycobacterial microcompartment shell proteins constrains models of global architecture and transport. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:1197–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greber BJ, Sutter M, Kerfeld CA. The plasticity of molecular interactions governs bacterial microcompartment shell assembly. Structure. 2019;27:749–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takenoya M, Nikolakakis K, Sagermann M. Crystallographic insights into the pore structures and mechanisms of the EutL and EutM shell proteins of the ethanolamine‐utilizing microcompartment of Escherichia coli . J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6056–6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thompson MC, Cascio D, Leibly DJ, Yeates TO. An allosteric model for control of pore opening by substrate binding in the EutL microcompartment shell protein: Pore regulation by substrate binding. Protein Sci. 2015;24:956–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sagermann M, Ohtaki A, Nikolakakis K. Crystal structure of the EutL shell protein of the ethanolamine ammonia lyase microcompartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8883–8887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klein MG, Zwart P, Bagby SC, et al. Identification and structural analysis of a novel carboxysome shell protein with implications for metabolite transport. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:319–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanaka S, Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, et al. Atomic‐level models of the bacterial carboxysome shell. Science. 2008;319:1083–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wheatley NM, Gidaniyan SD, Liu Y, Cascio D, Yeates TO. Bacterial microcompartment shells of diverse functional types possess pentameric vertex proteins. Protein Sci. 2013;22:660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sutter M, Wilson SC, Deutsch S, Kerfeld CA. Two new high‐resolution crystal structures of carboxysome pentamer proteins reveal high structural conservation of CcmL orthologs among distantly related cyanobacterial species. Photosynth Res. 2013;118:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cai F, Menon BB, Cannon GC, Curry KJ, Shively JM, Heinhorst S. The pentameric vertex proteins are necessary for the icosahedral carboxysome shell to function as a CO2 leakage barrier. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fan C, Cheng S, Liu Y, et al. Short N‐terminal sequences package proteins into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7509–7514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kinney JN, Salmeen A, Cai F, Kerfeld CA. Elucidating essential role of conserved carboxysomal protein CcmN reveals common feature of bacterial microcompartment assembly. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17729–17736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aussignargues C, Paasch BC, Gonzalez‐Esquer R, Erbilgin O, Kerfeld CA. Bacterial microcompartment assembly: The key role of encapsulation peptides. Commun Integr Biol. 2015;8:e1039755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cai F, Dou Z, Bernstein S, et al. Advances in understanding carboxysome assembly in prochlorococcus and synechococcus implicate CsoS2 as a critical component. Life. 2015;5:1141–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cameron JC, Wilson SC, Bernstein SL, Kerfeld CA. Biogenesis of a bacterial organelle: The carboxysome assembly pathway. Cell. 2013;155:1131–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fan C, Cheng S, Sinha S, Bobik TA. Interactions between the termini of lumen enzymes and shell proteins mediate enzyme encapsulation into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14995–15000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iancu CV, Morris DM, Dou Z, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Jensen GJ. Organization, structure, and assembly of α‐carboxysomes determined by electron cryotomography of intact cells. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:105–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen AH, Robinson‐Mosher A, Savage DF, Silver PA, Polka JK. The bacterial carbon‐fixing organelle is formed by shell envelopment of preassembled cargo. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zarzycki J, Erbilgin O, Kerfeld CA. Bioinformatic characterization of glycyl radical enzyme‐associated bacterial microcompartments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:8315–8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Craciun S, Marks JA, Balskus EP. Characterization of choline trimethylamine‐lyase expands the chemistry of glycyl radical enzymes. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1408–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kalnins G, Kuka J, Grinberga S, et al. Structure and function of CutC choline lyase from human microbiota bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae . J Biol Chem. 2015;290:21732–21740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ferlez B, Sutter M, Kerfeld CA. Glycyl radical enzyme‐associated microcompartments: Redox‐replete bacterial organelles. MBio. 2019;10:7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Baumgart M, Huber I, Abdollahzadeh I, Gensch T, Frunzke J. Heterologous expression of the Halothiobacillus neapolitanus carboxysomal gene cluster in Corynebacterium glutamicum . J Biotechnol. 2017;258:126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parsons JB, Dinesh SD, Deery E, et al. Biochemical and structural insights into bacterial organelle form and biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14366–14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bonacci W, Teng PK, Afonso B, et al. Modularity of a carbon‐fixing protein organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:478–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kirst H, Kerfeld CA. Bacterial microcompartments: Catalysis‐enhancing metabolic modules for next generation metabolic and biomedical engineering. BMC Biol. 2019;17:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kalnins G, Cesle E‐E, Jansons J, Liepins J, Filimonenko A, Tars K. Encapsulation mechanisms and structural studies of GRM2 bacterial microcompartment particles. Nat Commun. 2020;11:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang M, Simpson DM, Wenner N, et al. Decoding the stoichiometric composition and organisation of bacterial metabolosomes. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sutter M, Greber B, Aussignargues C, Kerfeld CA. Assembly principles and structure of a 6.5‐MDa bacterial microcompartment shell. Science. 2017;356:1293–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hagen A, Sutter M, Sloan N, Kerfeld CA. Programmed loading and rapid purification of engineered bacterial microcompartment shells. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Parsons JB, Frank S, Bhella D, et al. Synthesis of empty bacterial microcompartments, directed organelle protein incorporation, and evidence of filament‐associated organelle movement. Mol Cell. 2010;38:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Luque A, Reguera D. The structure of elongated viral capsids. Biophys J. 2010;98:2993–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kennedy NW, Hershewe JM, Nichols TM, et al. Apparent size and morphology of bacterial microcompartments varies with technique. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0226395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Iancu CV, Ding HJ, Morris DM, et al. The structure of isolated synechococcus strain WH8102 carboxysomes as revealed by electron cryotomography. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:764–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Havemann GD, Bobik TA. Protein content of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B12‐dependent degradation of 1,2‐propanediol in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5086–5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache J‐P, Verba KA, Cheng Y, Agard DA. MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam‐induced motion for improved cryo‐electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2017;14:331–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang K. Gctf: Real‐time CTF determination and correction. J Struct Biol. 2016;193:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zivanov J, Nakane T, Forsberg BO, et al. New tools for automated high‐resolution cryo‐EM structure determination in RELION‐3. Elife. 2018;7:e42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Cryo‐EM sample analysis. CmcABC' + D + CutC + CutO BDP purification, sample selection and enzyme quantification. A. Gel filtration of BDPs using Superose 6 16/900 GL and fraction analysis in SDS‐PAGE. Fractions selected for cryo‐EM analysis higlighted in gel filtration graph. B. Gel densitometry analysis of selected BDP fractions. 1–76‐79 mL concentrated fractions, bands of CutC and CutO used in analysis highlighted, 2–7– CutC standard curve samples, 8–2– CutO standard curve samples. Analysis performed with ImageJ software.

Figure S2: Negative staining TEM analysis of Superose 6 gel filtration purification of fractions of CmcABC' + D + CutC + CutO BDPs. Fractions correspond to the previous figure.

Figure S3: A representative Cryo‐EM micrograph of BDPs.

Table S1: Cryo‐EM data collection, refinement and validation statistics.

Appendix S1: Supplementary Dataset 1 with calculations of gel densitometry analysis is included. All cryo‐EM 3D reconstruction maps are available in Electron Microscopy Data Bank repository as EMD‐12252, EMD‐12253, EMD‐12254 and EMD‐12255 entries.