Abstract

Legal contexts frequently impose steep communication barriers, but because the law’s ontological framework of communication views it as an atomized, transaction phenomenon, the law lacks the ability to conceptualize and describe the way in which it itself imposes systemic communication burden. To overcome this shortcoming, this article presents a model for a systemic analysis of communication within the law. Part One operationalizes a set of cognitive-communication resources necessary to navigate communication in legal contexts. Part Two uses the operational model to illustrate how systemic elements of the law pressure the cognitive resources that underlie communication. Finally, Part Three uses the model to predict how possible systemic interventions might improve communication outcomes by alleviating or reducing systemic communication burdens. Not only does this article provide a conceptual tool to articulate the law’s systemic impacts on communication, the subsequent analysis offers a framework for exploring interventions that could ultimately lead to better outcomes for persons, particularly vulnerable or at-risk persons, who must navigate legal contexts. By changing how it conceptualizes communication and working to modify the communication dynamics that it itself perpetuates, the law can reduce the weight of the communication burdens that it imposes on the people within it.

Keywords: cognitive communication, law, neuroethics, neurolaw, neuropsychology

Few social contexts are as likely to tax the cognitive and mental resources that humans use to communicate as legal contexts. Ethnographic and linguistic reports have long described the unusual and onerous communication dynamics that typify communication between legal professionals and lay persons;1 experimental scientific studies have found that lay persons—especially those who are at greater risk of communication challenges—perform poorly on tasks that require them to comprehend and manipulate legal-communication stimuli;2 and surveys of incarcerated and adjudicated populations have consistently found an overrepresentation of communicatively vulnerable persons,3 a finding that draws a particularly stark connection between communication capability and legal trajectory. Viewed through this system-level lens, the law appears to be a construct of communication contexts in which receiving, interpreting, and producing communication can be prohibitively difficult, with severe punishment and consequences awaiting people with communication difficulties or limitations.4

Despite the challenges that lay persons who must communicate within legal contexts face, however, US law lacks an ontological framework to conceptualize its own systemic influence on communication outcomes. Driven in part by the common law’s reliance on human communication as a tool of ‘adversarial testing’,5 US law portrays communication as a phenomenon that arises from, and must be resolved by, individual actors. The individual lay person is tasked with mustering the communication resources sufficient to navigate a given legal task—notably, the resources necessary to communicate with their attorney—and is ultimately responsible for whatever ‘misfortune’ any communication shortcomings or deficits might cause;6 the individual attorney is tasked with managing the client’s involvement and with guaranteeing that the client is sufficiently able to participate;7 and the individual judge is tasked with determining whether or not a party has satisfied the appropriate legal standard for which communication might be required.8 As a result, communication within US law is an atomized, transactional property: it exists solely and independently within individual persons or individual dyads and solely for the purposes of fulfilling a procedural legal goal. Not only does this conceptualization overlook the role that context plays in dictating the parameters of communication9—the way in which the specialized vocabularies and testimonial approach that lay persons in small-court claims must adapt diverge from everyday narrative communication, for example10—it shifts the onus of overcoming communication challenges onto individual attorneys despite the fact that systemic limitations such as money and time resources11 make solutions at the level of individual actors impractical or impossible. Taken together with the United States’ negative-rights framework under which the system has no obligation (or incentive) to affirmatively guarantee rights that revolve around communication,12 the US legal system lacks ontological tools to either describe or combat the systemic risks that legal communication poses.

To help overcome these limitations, this article presents a model of communication for a systemic analysis of legal communication. Part One will operationalize a model describing a set of cognitive resources necessary to navigate communication in legal contexts. Part Two will use the model to illustrate how systemic elements within the law pressure and burden the cognitive resources that power communication. Finally, Part Three will conclude by using the model to predict how possible systemic interventions might improve communication outcomes by alleviating or reducing systemic communication burden. Not only will the model provide a conceptual tool to articulate the law’s systemic impacts on communication, the subsequent analysis will offer a framework for beginning to explore interventions that could ultimately lead to better outcomes for persons, particularly vulnerable or at-risk persons, who must navigate legal contexts. By changing how it conceptualizes communication and working to modify the communication dynamics that it itself perpetuates, the law can reduce the weight of the communication burdens that it imposes on the people within it and encourage more-equitable outcomes.

I. AN OPERATIONALIZED MODEL OF LEGAL COGNITIVE COMMUNICATION

Communication is an exceedingly complex human ability built from dozens of cognitive and neurological functions that range from ‘basic’ aspects of human cognition such as memory and attention to ‘sophisticated’ aspects of human cognition such as narrative production and language processing.13 Despite the underlying clinical and scientific complexity, however, this suite of cognitive functions—typically referred to using the umbrella term ‘cognitive communication’—serves the relatively straightforward role of regulating the content, organization, coherency, speed, and utility of both verbal and non-verbal communication. Cognitive communication’s ultimately utilitarian nature is a convenient starting point for understanding how cognitive communication interacts with legal communication; rather than focusing on discreet cognitive mechanisms and their neuropsychological and behavioral correlates, this article will operationalize cognitive communication as a set of qualitative resources that facilitate a person’s ability to perform the types of functional cognitive tasks required to navigate legal communication.

The model of legal cognitive communication (Figure 1) centers on three primary cognitive abilities: accessing communicated information, internalizing communicated information, and interacting with communicated information. These three abilities broadly underlie the cognitive-communication functions individuals in legal contexts need to perform: they need to be able to access information from writing and speech in order to participate in the communication’s exchange of ideas and content14 (ie to have the ‘sufficient present ability to consult’ and the ‘factual understanding of the proceedings’, to draw parallels to the framing of communicative competency under US law15); they need to be able to internalize information in order to construct comprehension of the communication’s meaning and significance16 (ie the ‘rational as well as factual’ understandings stipulated by US law17); and they need to be able to interact with the information in order to translate it into decisions and actions 18 (ie the law’s ‘sufficient present ability to consult with a reasonable degree of rational understanding’ and ‘factual understanding’ framings19). Under the model, then, communication ability is operationalized as the extent to which a person has or can access the cognitive resources that bolster these three broad functions.

Figure 1.

A model of cognitive communication operationalized for legal communication and legal contexts.

The model operationalizes the cognitive resources that support accessing information as those involved in extracting, holding, and manipulating information. The resources in this category set limits on the volume (eg working memory20), speed, (eg processing speed21), and type (eg word/grammar decoding22) of information available to a person during communication, effectively defining the limits of the cognitive ‘workspace’ in which communication can occur. These resources act as a sort of mental bandwidth: access to more ‘accessing information’ resources will lead to relatively faster and fuller communication than access to fewer resources.

The cognitive resources that facilitate internalizing information are those involved in conceptualizing, perceiving, and understanding information. The resources in this group allow a person to create internal representations of communication. These internal representations, also known as situation models or schema, form the basis of a person’s understanding or comprehension of communicated information; 23 put in more-colloquial terms, the internal representations are the pictures or perceptions that a person sees in their head as they understand communication. The ‘internalizing information’ resources directly construct these internal representations in order to derive meaning from information, typically by using background knowledge and knowledge from prior experiences (eg situation-model building24); resolve gaps in the information (eg making inferences and processing non-literal language25); and add emotional or sensory components to internal representations of the information (eg emotion recognition and embodied cognition26). By building and populating the internal representations through which a person perceives and understands communication, the ‘internalizing information’ resources define the appearance, coherence, and emotional color of a person’s comprehension of communicated information, acting as a sort of mental software program: access to more resources in this tier will allow for relatively more-detailed and more-accurate internal perceptions of the communication.

Finally, the cognitive resources that support interacting with information are those involved in refining, monitoring, and using information. The resources in this category direct focus and weight to information internal or external (eg attention and attentional control27), accommodate social features of communicated information (eg social cognition28), update and oversee internal representations (eg metacognition29), recognize different styles or goals of communication (eg language genre-parsing30), weigh risks and consider contrafactual or potential outcomes,31 help make decisions based on the internal representations,32 and help prepare internal representations for external communication (eg narrative formation33). These ‘interacting with information’ resources shape the configuration, malleability, and fluidity of internal and external information, acting as a sort of user interface through which a person is able to engage with communication: access to more of these resources will allow for relatively more-refined and more-competent communication.

Two additional aspects of the model are important to note. First, the three categories of cognitive function are not mutually exclusive:34 resources and function in one group are tied to resources and function in the others. For example, the informational volume and speed set by the ‘accessing information’ resources will dictate the volume and speed of the cognitive resources available for the other two categories, while the attention resources from the ‘interacting with information’ group can dictate the targets of other resources in the model’s other groups. Second, and more importantly, the cognitive-communication resources within the model are not static properties:35 The amount of resources, and the ability to utilize them, can vary considerably based on internal and external factors. For example, a sleep-deprived individual may have poorer-quality cognitive communication as a result of poorer-functioning resources (less-efficient memory, impaired concentration, eg) than they would have had if they were well-rested, whereas a person in a conversation that interests them may have better-quality cognitive communication as a result of increased utilization of resources (greater attention, more-detailed internal representations, eg) than they would have had in a less-engaging conversation. In this regard, it is important to remember that cognitive communication is not an ‘all-or-nothing’ phenomenon; the baseline levels of and utilization of the underlying cognitive resources vary not just from person to person but also from context to context.

As an example of how the model’s cognitive-communication functions relate to communication within legal contexts, consider a frequent scenario: a defendant and their attorney discussing constitutional rights during a guilty plea.36 One section of the plea questionnaire, a standardized form employed by the court to guide the plea process, 37 reads as follows:

Constitutional Rights

I understand that by entering this plea, I give up the following constitutional rights:

□ I give up my right to a trial.

□ I give up my right to remain silent and I understand that my silence could not be used against me at trial.

□ I give up my right to testify and present evidence at trial.

□ I give up my right to use subpoenas to require witnesses to come to court and testify for me.

□ I give up my right to a jury trial, where all 12 jurors would have to agree that I am either guilty or not guilty.

□ I give up my right to confront in court the people who testify against me and cross-examine them.

□ I give up my right to make the State prove me guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.38

In order to successfully navigate this context—‘successfully’ meaning meeting the level of understanding required by the controlling legal standard to competently and permissibly complete the plea39—the defendant will need to recruit cognitive-communication resources to access, internalize, and interact with the written information this section of the form contains and whatever spoken information the lawyer adds.

First, the defendant will recruit ‘accessing information’ resources to extract information from the text: to physically read the words and sentences (eg decoding the words ‘subpoena’ and ‘testify’) and to parse the grammar (eg to read the indirect speech that follows ‘I understand that’ in the first sentence). The ‘accessing information’ resources will also allow the defendant to store and hold information in their mental workspace (eg to remember that all the statements with boxes in front of them refer back to the rights that are given up). Similarly, the ‘accessing information’ resources will set the limits of this mental workspace. The amount of resources that the defendant has or can recruit will determine how fast they can read or listen, parse sentences, and decode words and how much information they can parse, decode, and store.

Next, the defendant will use the ‘internalizing information’ resources to build internal representations of the text; that is, they will use the resources to turn the information they read or hear into mental pictures of the information’s meaning. The ‘internalizing information’ resources will allow the defendant to use background knowledge and information to understand the meaning of the text (eg to understand that ‘to give up’ rights means to lose them and to understand the concepts contained within the phrase ‘a trial’), to use inferences to resolve implied meaning within the text (eg to understand that ‘the following constitutional rights’ means the list of boxes or to understand who ‘the State’ is), and to create visualizations of the text that incorporate visual or physical perceptions (eg to envision a jury or to picture themselves in a trial). Effectively, the ‘internalizing information’ resources are the ones that allow the defendant to understand the meaning conveyed through the text, with the composition of that understanding depending on the quality and the complexity of the verbal and non-verbal information (background or immediate) that the defendant can access to construct their comprehension—for example, how much they know about the law, whether or not they have physically observed a trial or a courtroom, and how easily they can visualize abstract concepts such as ‘rights’ and ‘evidence’.

Finally, the defendant will use the ‘interacting with information’ resources to interact with the information they have extracted and internalized. These resources will allow the defendant to focus their attention on the text (eg to focus on reading each statement in turn); to correct and update their internal representations (eg to expand their representation of ‘giving up rights’ to include each of the checkbox statements, or to revise their representations as the lawyer adds clarifying information [‘A “subpoena” is an order from a judge that people have to obey’, for example]); to consider the consequences of the text (eg to think about what ‘giving up rights’ means for them in the future); to make decisions about the information (eg to decide whether or not they want to give up those rights); and to prepare communication based on the text (eg using the information they gained from the text to ask questions or make statements about the plea). The amount of ‘interacting with information’ resources that the defendant has or can access will determine how quickly and how effectively they can use the information as the basis for communication behaviors: how quickly and effectively they can think about the information and its consequences, how quickly they can use the information to form internal narratives (eg the narrative of them proceeding through the guilty-plea process), and how quickly and effectively they can revise and update the information as they progress through the rest of the plea questionnaire.

As a brief aside, note that this article’s model of cognitive communication does not include the physical or motor aspects of communication (eg the cognitive functions that directly support speaking, writing, hearing, or seeing).40 Although these functions would be essential components of the hypothetical defendant’s ability to physically communicate with their attorney and to access and use legal information,41 this article focuses on mental components of cognitive communication in order to describe how these ‘invisible’ resources drive and influence the sorts of communication behaviors relevant to legal contexts and legal standards. As such, this article’s hypothetical defendant can be assumed to otherwise be able to physically read, speak, and listen during their communication. Nevertheless, keep in mind that while the cognitive-communication resources illustrated by the model are necessary parts of legal communication, they are not sufficient for legal communication.

To summarize, cognitive communication refers to a suite of cognitive functions that allow humans to access information from communication, internalize that information, and then interact with that information to direct their own communication. This article’s operationalized model emphasizes the functional roles that power communication to illustrate the fact that communication relies on a pool of interdependent cognitive resources, all of which can affect the quality of the resulting communication. Successful navigation of legal contexts, therefore, is less a question of whether or not a person possesses a specific cognitive trait and more a question of whether a person can, for any given context, utilize the cognitive resources they need at the levels they need to. If a person can, then their cognitive communication will be relatively better and relatively faster, and their resulting communication will be relatively better. If they cannot, then their cognitive communication will be relatively poorer and relatively slower, and their resulting communication will be relatively poorer. Put another way, the electronic circuitry that the ‘accessing information’, ‘internalizing information’, and ‘interacting with information’ functions power is on a dimmer switch, not an on/off switch: contexts and conditions that put additional burden on the model’s cognitive resources or demand increased amounts of resources risk frustrating or impeding the subsequent communication, and contexts and conditions that relieve burden from the model’s cognitive resources or require fewer of those resources may facilitate and support the subsequent communication. As a result, the analysis of systemic risk and interventions that follows in Parts Two and Three becomes a question of whether systemic features of legal communication make it more or less likely that a person will face burden on their ability to have or use cognitive-communication resources.

II. SYSTEMIC COMMUNICATION RISKS

Part Two begins the analysis by considering how predictable aspects of US legal systems increase the likelihood of cognitive-communication burden. It is unquestionably the case that legal systems make communication difficult,42 but with the cognitive-communication model having been established in Part One, Part Two’s analysis will illustrate how this difficulty may be linked to features of the law that place relatively greater pressure on the cognitive-communication resources people in the law need to navigate it. Such an illustration will underscore the important role that the law itself plays in shaping communication behavior, and it will demonstrate how legal procedures and safeguards that rely on communication must consider the deleterious effect that they themselves might have on the cognitive-communication resources that ultimately facilitate them.

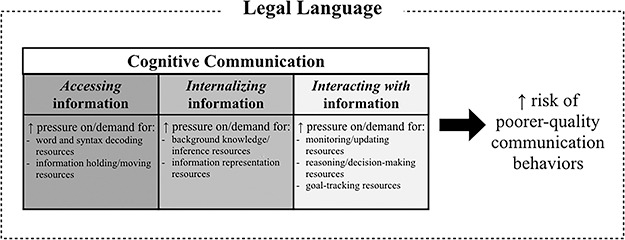

II.A. The language of the legal system

Somewhat paradoxically for a system that exists entirely through human language, the law’s ‘legalese’ dialect is notoriously inaccessible and inscrutable.43 Legalese’s challenging nature comes with increased demands on cognitive-communication resources,44 and because lay persons need to navigate such language as they progress through the system, the impact that legalese has on the cognitive-communication model will illuminate the systemic communication risks that the law imposes. Given legalese’s content, structure, and usage, it can be expected to place burden on cognitive-communication functions throughout the model, increasing both the need for cognitive-communication resources and the likelihood that a lay person will struggle to meet that need (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interactions between legalese language and cognitive communication. Up arrows (↑) represent an increase or elevation.

First, legalese can be expected to place burden on the cognitive-communication functions involved in extracting, holding, and manipulating legal information. The types of complicated grammar and vocabulary common in legalese—the features that are traditionally associated with its difficulty—require more resources to decode and manipulate than less difficult language.45 As a result, the lay person attempting to use the ‘accessing information’ group of cognitive-communication resources will need to either possess or recruit additional resources, putting additional strain on their cognitive communication. Legalese can also be expected to place burden on the cognitive-communication functions involved in conceptualizing, perceiving, and

understanding information from legal communication. Understanding complex, abstract language requires situation models (ie the internal representations) that accurately represent the complex, abstract ideas the language represents, and these types of situation models typically require relatively more cognitive-communication resources to develop and populate.46 Similarly, understanding symbolic and acontextual concepts (eg ‘being a felon’ or ‘losing one’s rights’) are more difficult to ground in internal perceptions of visual or physical details,47 so lay persons face additional cognitive demand when attempting to internalize legal communication. Compounding this difficulty, lay persons generally will not have first-hand experience with or considerable background knowledge of the concepts or ideas that legalese describes, so lay persons will have fewer overall resources to use within their internalization of legalese communication.48 With this increased conceptual difficulty, legalese can be expected to place increased demands on the ‘internalizing information’ group of cognitive-communication resources, further raising the level of resources that must be accessed or possessed. Finally, legalese can be expected to place additional demands on the cognitive-communication resources that help refine, monitor, and use communicated information. Complex internal representations are more difficult to update and monitor, particularly when those representations are incorrect,49 so legalese will require relatively more resources that support attending to and overseeing communicated information. Additionally, tracking the types of communication goals legalese typically facilitates (eg narrative, procedural, and expositional goals50) will require more cognitive-communication resources that help maintain coherence and salience,51 so legalese will force additional resources required to track and refine the communicated information (eg maintaining a consistent internal narrative when speaking to law enforcement). The complex, abstract language will also be more difficult to use in reasoning or decision-making, which means that greater abilities or resources within the ‘interacting with information’ group will be required to use legalese information as the basis for subsequent reasoning or action52 (eg attempting to weigh the pros and cons of a particular course of legal action). With this increased need for resources that can meaningfully interact with communicated information, legalese can be expected to increase contextual demands on the ‘interacting with information’ group of cognitive-communication resources, raising the level of resources that the lay person must be able to access even further. To summarize, the model predicts that the legal system’s language will demand more cognitive resources from each group of cognitive-communication functions. If a person does not have, or cannot access, the cognitive-communication resources they need to parse, internalize, or manipulate a given example of legalese, then their cognitive communication will be slower, poorer, or both, raising the risk of poorer communication and poorer outcomes as a result of the law’s systemic language.

It is important to remember that legalese’s systemic risks arise not just from its inherently difficult nature but also from its compulsoriness. The system simply does not offer alternative ways to conduct and resolve its own social interactions: not only does the law tautologically exist through its own language,53 but also the legal actors who populate the law will necessarily use the law’s language in order to function within and advance the system. Consequently, any individual in any legal context will need to navigate that context exclusively through legal language. This means that, for any given person in any given legal context, the person will be forced to muster whatever amount of cognitive-communication resources are needed to access, internalize, and interact with that context’s legalese information. By forcing individuals to use language that demands relatively more cognitive-communication resources, however, the law makes the communication process inherently more difficult, raising the risk that the person will demonstrate poorer quality cognitive communication and poorer quality subsequent communication.

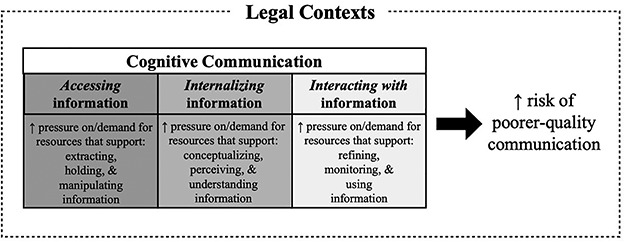

II.B. The interpersonal communication dynamics of the legal system

By nature of their shared human biology, both lay persons and legal actors will use the same underlying suite of cognitive-communication functions to power and drive their communication as they navigate legal contexts. However, legal actors’ role and position within the legal context afford them relative advantages and privileges that the lay person will not have, and this uneven social dynamic will create an uneven communication dynamic. The conceptual model will show how this skewed interpersonal communication dynamic affects the parties’ cognitive-communication resources and translates into additional burden on the lay person’s cognitive communication (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interaction between interpersonal communication dynamics within legal contexts and cognitive communication. Up arrows (↑) represent an increase or elevation.

Legal actors enjoy a number of benefits that tilt the balance of communication in their favor. Legal actors have first-hand experience navigating legal contexts, which grants them greater familiarity and fluency with legal communication.54 Legal actors have access to scripted, narrow communication strategies—for example, interrogatory yes–no questions such as those common in police interrogations or judicial colloquies—that more-easily comply with the law’s idiosyncratic and unusual communication expectations.55 Finally, legal actors enjoy positions of relative power and authority, which reduces the consequences of their own communication actions and which encourages lay persons toward acquiescent or compliant communication actions.56 These benefits all equate to a context skewed toward the legal actor: legal actors will have relatively easier, relatively faster communication, and the dynamics of the context in which they act will be reflective of that easier, faster communication.

This imbalanced communication dynamic will add additional burden to the lay person’s cognitive communication. Because the legal actor has disproportionate influence on the shape and structure of the context’s communication, the volume, speed, and content of the cognitive space in which that communication occurs will be increased; in order to communicate within those parameters, the lay person will need the ‘accessing information’ resources to decode the information, hold and store the information, and manipulate the information to the degree set by the legal actor (or reflected within the dynamic) or risk relatively sparser, relatively slower communication.57 Similarly, because the legal actor’s communication reflects a greater familiarity with the ideas and concepts conveyed through legal communication, the communication dynamic will reflect the relatively more-accurate internal representations that the legal actor is able to create. In order to communicate with parity about those representations, the lay person will need the ‘internalizing information’ resources to gain comparable understanding with comparable perceptions and comparable visualizations or risk less-accurate, less-complete communication58—for example, a lay person’s need to understand what it means that the lawyer is their ‘employee’ within the context of legal representation.59 Finally, because the legal actor’s privilege will color the consequences and goals of the context’s communication, the lay person will need the ‘interacting with information’ resources to manipulate their internal representations and understandings in order to follow the communication’s flow—for example, a lay person’s need to update their internal narrative of their testimony after a judge admonishes them to not give long-winded answers.60 The lay person will also need the ‘interacting with information’ resources to recognize the accuracy of their own internal representations and decoded information in light of the contextual pressure to acquiesce to the legal actor or to avoid undesirable outcomes.61 The sum-total of the uneven communication dynamic is a system that places additional demands on the lay person’s cognitive communication, which increases the risk of slower, poorer quality communication.

As was the case for systemic language, the uneven communication dynamics between legal actors and lay persons constitute a systemic communication risk because such dynamics are largely unavoidable. Because the law is a human-administered construct, a lay person’s encounter with it will always involve language-based interactions with other humans (eg with police officers, attorneys, and judges). Because there is no alternative system, the law forces lay people—who, incidentally, tend to have much less conventional education than the legal actors62—into contexts with uneven communication dynamics simply by being a system populated and administered by legal actors. Similarly, modern legal systems, particularly those with adversarial frameworks like the United States, are built upon the assumption that lay people will have legal representation as they navigate legal encounters, or at least legal contexts within a criminal proceeding.63 Unfortunately for lay persons, this systemic feature perpetuates uneven communication dynamics by (i) making lawyer–lay person dyads the standard communicative unit through which lay persons are expected to resolve their legal matters and (ii) allowing the legal system to adjust its own language and communication to account for the assistance and information that the lawyer is assumed to provide—as explained earlier, this atomized view of communication lacks the ability to conceptualize the effects the system itself has on communication.64 In effect, the law’s focus on the attorney–lay person dyads puts lay individuals in a cognitive-communication Catch-22: they are at a considerable communication disadvantage if they do not retain an attorney, but having an attorney puts them in a dyad in which the communication dynamic is inherently skewed against them and in which they have a relative cognitive-communication disadvantage. These realities contribute to a system in which interpersonal communication increases the demand for cognitive-communication resources and creates a risk of poorer, slower communication.

II.C. The environmental stressors of the legal system

Legal contexts are almost universally stressful,65 and lay persons in them will experience communication against a backdrop that is almost guaranteed to contain both physiological and psychological stressors.66 The high-stakes ways in which stress and communication interact under the law—for example, a traumatized victim giving testimony in an assault case or a person attending a crowded, rushed hearing67—illustrate the importance of understanding how systemic environmental conditions impact cognitive communication (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Interaction between legal contexts’ environmental stressors and cognitive communication. Up arrows (↑) represent an increase or elevation.

As was true for systemic language and systemic communication dynamics, the cognitive-communication model demonstrates how the environment in which legal contexts transpire adds burden to the cognitive functions that underlie communication. Stress drains cognitive resources that support tasks such as memory and speed-of-processing, thereby shrinking the available cognitive space to decode, hold, and manipulate information68 (eg a rushed courtroom context imposing limits on the amount of time a lay person has to think). Additionally, stress is closely associated with negative or disturbed emotional states,69 and because emotion is tightly integrated into internal representations and perceptions of communicated information—particularly of the abstract, acontextual communication that frequently occurs in legal contexts70—stress can be expected to alter the way in which a person internalizes and understands legal communication, including biasing a person toward internalizations that overrepresent the negative emotions associated with stress71 (eg bias toward perceiving legal contexts as hostile and unfair72). Finally, stress undercuts attention and attentional control, again by siphoning away the cognitive resources that would otherwise bolster these functions;73 not only will this attenuation limit the extent to which a lay person can monitor, update, and use their internal representations (eg in making decisions or weighing risks), but it will also limit the extent to which they can direct resources within the ‘accessing information’ and ‘internalizing information’ groups of functions (eg by making it more difficult to pay attention to what a legal actor is saying). In summary, stress can be expected to limit the availability of or skew the functioning of cognitive-communication resources, which can increase the risk of poorer quality communication.

As was also true for systemic language and systemic communication dynamics, the laws’ environmental stressors create systemic risk not simply because they exist but because they are unavoidable. Lay persons and legal professionals alike have little to no control over the contexts of their communicative encounters within the legal system. For example, a lawyer’s caseload and calendar are largely determined by the courts or the firm, and a lay person’s court appearance is largely determined by the judge’s scheduling; in neither case does the individual communicator have the opportunity to simply ignore the system’s timeline in favor of one that allows them to be less overworked, better rested, less hungry, or generally less stressed. Perhaps more importantly, lay individuals do not have the option to simply eschew the legal system. Being pulled over by the police or having to negotiate child custody might be tremendously stressful, highly emotional events, but once the system’s procedural wheels are set to grinding, the individual will be pinned within them even though the stress of being in that system might compromise their cognitive communication. This unavoidability is particularly damning in light of empirical findings that suggest that even slight situational stressors in the controlled, anodyne settings of scientific studies can drastically decrease reasoning and decision-making skills associated with manipulating legal information.74 That the legal system struggles to reduce the stress its own actors experience75—to say nothing of the individuals who face retraumatization as part of standard legal processes76—is indicative of a pervasive systemic risk, and it is likely that systemic stress contributes to undesirable legal outcomes for individuals who for whatever reason are not able to accommodate that stress’s impact on their own cognitive communication.

To summarize the model’s overall conceptualization of the law’s systemic communication risks, legal contexts create systemic risk by taxing or limiting resources needed to access, internalize, and interact with communication-based information, thereby burdening cognitive-communication function and risking poorer quality communication (Figure 5). Certain language burdens, communication-dynamic burdens, and environmental-stressor burdens will have greater impact than others, but because the burdens are inherent features of the way in which US law uses communication, the system will impose those burdens regardless of the specific details of the legal context and regardless of the specific capabilities of the individuals within them; in other words, the systemic features that the law has established make it more likely that a person within it will face relatively greater burden as they attempt to recruit and use the cognitive-communication resources they need to communicate. Imagine that the law’s systemic communication risks are a series of hurdles. The height and frequency of the hurdles will be different for each individual person and each specific context, and some people will be inherently better at clearing the hurdles than others, but successfully navigating legal contexts will require every individual to clear whatever hurdles they encounter. If the hurdles are too high, or if the individual cannot clear them quickly or effectively enough, then their cognitive communication, and the resulting communication, will suffer accordingly.

Figure 5.

Overall summary of the effects of legal contexts on cognitive communication. Up arrows (↑) represent an increase or elevation.

II.D. Systemic risks–illustrative example

Part Two concludes by revisiting the example legal scenario from Part One, the guilty-plea discussion, and exploring how these systemic risks might impede the defendant’s ability to successfully navigate the plea questionnaire’s language. Applying the analysis of systemic communication risks to this hypothetical context should more tangibly illustrate how legal contexts impose burdens on the cognitive-communication resources that support communication.

First, how might the law’s language affect this hypothetical defendant’s communication? The plea statements are informationally dense, containing at least seven different rights all embedded within the sentence ‘I give up the following constitutional rights’; to truly understand what rights will be given up, the defendant will need the ‘accessing information’ resources to hold and remember all the information, both as they read it and as they turn it into internalizations.77 The statements also contain a fair number of abstract, technical words and terms (‘subpoena’, ‘right to remain silent’, etc.) Not only may these words and terms be more difficult to parse, the defendant may need additional cognitive-communication resources to turn those words and phrases into internalized representation.78 Additionally, because the text offers no definitions or contextualization of the various legal concepts and ideas, the defendant will need to rely on their own mental representations (eg by remembering what they saw on a TV procedural)79 or on the explanations from their attorney to gain additional details for their comprehension of the text’s meaning. In either case, the defendant will need relatively greater amounts of ‘internalizing information’ resources to build a visualization of the abstract, acontextual concepts like ‘the right to remain silent’ and relatively greater amounts of ‘interacting with information’ resources to make sure that this visualization incorporates or matches the attorney’s explanation—given that most people appear to generally lack basic legal knowledge and to struggle with recognizing the limits of their understanding,80 this task might be particularly difficult for the hypothetical defendant. Finally, difficulty in creating internal representations likely translates into difficulty in interacting with those representations: if the defendant has an incomplete or bare-bones representation of the information, then it will be more difficult for them to think about the information’s consequences.81 For example, the defendant’s incorrect internalization of ‘the right to remain silent’ may cause them to misinterpret the extent to which they would be able to participate in their own defense.82 Even in this relatively simple example, the nature of legalese language can be expected to tax the defendant’s cognitive-communication resources. Consider too how this example analysis creates tension for the law’s ontological conceptualization of communication: the law expects the defendant to obtain various ‘rational’ and ‘factual’ competencies of the legal information in the plea questionnaire, but it creates and conveys that information using language that throws hurdles in the way of the cognitive-communication resources that ultimately support those competencies.

Next, how might the communication dynamic affect the hypothetical defendant’s communication? The somewhat paradoxical relationship between the attorney and the defendant—in which the defendant is technically ‘the boss’ but in which the attorney has the expertise, experience, and authority—likely means that the defendant will defer to the attorney’s explanations or questioning:83 in terms of the cognitive-communication model, this means that the defendant may need the resource wherewithal sufficient to monitor and process their internal representations and to reason through the consequences against the contextual pressure to simply nod their head and say yes when the lawyer asks, ‘Do you understand this?’84 Similarly, the defendant will need to recruit resources that will allow them to recognize that their own understanding and the underlying representations likely differ from those of the attorney, who can create representations that are better grounded in the visual and physical experiences of their legal work. For example, the attorney’s understanding of ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ will benefit from their first-hand knowledge of legal theory and their work on criminal cases, but because the attorney cannot simply forget or compartmentalize their knowledge or experience within their own cognitive communication, any attempts they make to explain or simplify the term ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ (by framing it as a percentage of evidence, for example) will necessarily be based on their own relatively more-accurate, relatively better-quality internal representations; put another way, the attorney may be able to simplify language and explain concepts, but they can never put themselves in the defendant’s cognitive workspace.85 Conversely, the defendant’s understanding of the term ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ will likely lack first-hand background knowledge, and because the attorney cannot simply transmit their first-hand knowledge directly into the defendant’s head, the defendant will always be at a relative disadvantage when it comes to the accuracy and quality of their internal representations of what ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ means (the defendant may view ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ as something closer to ‘100% guilty’, for example).86 If the defendant wants to reach the attorney’s level of understanding, they will need to recruit additional cognitive-communication resources that will allow them to recognize any objective errors in their internal representation, process the new information, create a new representation, and use that new representation to replace the old one; all of this demand will place additional burden on the cognitive-communication framework. Based on the attorney’s education and training, they can also expect to enjoy relatively more of the ‘accessing information’ resources that define the cognitive workspace; this means that their baseline level of communication speed and volume will likely be higher than the defendant’s, so the defendant may need to utilize additional resources in order to close the gap between them and their attorney87 (eg what may appear to the attorney to be a comfortable reading or speaking speed may be uncomfortable for the defendant). Finally, the defendant and the attorney may operate under different communication goals: the defendant will likely be less interested in the procedural aspects of the communication (ie in ensuring that their discussion with their attorney satisfies the underlying legal requirements), while the attorney will likely be more interested in those procedural aspects.88 This disparity may influence the way the attorney communicates such that it limits the defendant’s ability to optimally utilize cognitive-communication resources; for example, if the attorney asks a series of yes/no questions to gauge the defendant’s understanding, the defendant will need sufficient cognitive-communication resources to evaluate their internal representations against a binary yes/no scale and as a result may have fewer opportunities to articulate what their understanding actually looked like.89 Even in this hypothetical’s relatively benign interaction, the nature of the attorney-client dyad can be expected to raise cognitive-communication dynamics that put the defendant at a relative disadvantage. Again note how this example illustrates the limitations of the law’s ontology: by defining communication as a product of the attorney-client dyad, the law forces the onus of managing legal communication onto the attorney but overlooks the fact that such communication will ultimately stem from the relative advantages that the attorney’s own cognitive-communication resources offer.

Finally, how might environmental stressors of a plea questionnaire’s context affect the hypothetical defendant’s communication? The defendant and their attorney will almost certainly have limited time for their discussion of the plea-questionnaire language: the attorney can be expected to have a rigorous caseload and schedule that permits only the bare minimum amount of time per client, and the discussion may occur just minutes before the courtroom hearing.90 The accelerated timeframe for the communication means that all the resource-recruiting the defendant needs to do will happen under a time limit. They will need to read, parse, and decode the text under a time limit, which means that they will need sufficient ‘accessing information’ resources to ensure that their cognitive workspace has sufficient space and speed. They will need to internalize the information about constitutional rights under a time limit, which means that they will need sufficient and immediately available ‘internalizing information’ resources to build mental representations of the plea-questionnaire’s information about constitutional rights. Finally, they will need to reason through the implications of the text under a time limit, which means that they will need sufficient ‘interacting with information’ resources to focus on the text, use the text’s information to think through the implications of the plea, and make decisions based on their reasoning all within the time limits of the discussion. This external time pressure can be expected to negatively affect the defendant’s ability to access the cognitive-communication resources they need to perform each of these tasks;91 for example, the defendant may not have enough time to build a sufficiently detailed internal representation of ‘the right to remain silent’ and may instead have to rely on a rudimentary representation.92 In other words, environmental time pressure will amplify the cognitive-communication hurdles that the text of the plea-questionnaire form already imposes. The time pressure may also exaggerate the effects of the imbalanced communication dynamic between the defendant and the attorney. Because of the attorney’s experience and training, their ability to access, internalize, and interact with the plea-questionnaire information will be faster and less effortful, so they will be less affected by the time pressure (eg a defense attorney who has read and explained the plea-questionnaire form a hundred times will have their own internal representations of the information about constitutional rights and the consequences of entering a guilty plea available almost automatically93); as a result, the communication dynamic may be further skewed in favor of the attorney. To summarize the impact that time pressure might have, time constraints can be expected to amplify the hurdles imposed by legalese language and skewed communication dynamics by limiting the amount of time a defendant has to recruit cognitive-communication resources to clear those hurdles.

The other environmental stressor that the hypothetical defendant is likely to encounter is psychological stress.94 As a result of the cognitively limiting effects of stress, a stressed defendant may have limited ‘accessing information’ resources and a correspondingly smaller cognitive workspace, which could limit their ability to focus on the plea questionnaire, limit their ability to remember each subsequent right in the list of forfeited rights, and limit their ability to process the consequences of their guilty plea.95 Similarly, a stressed defendant may have negative or perturbed emotions as a result of their legal ordeal; as a result, the environmental stress may bias them toward incorporating negative emotions into their internal representations (eg they may be less able to appreciate the value of their constitutional rights or they may be more likely to have negative impressions of ‘a jury’ or ‘the State’) and bias them toward interacting with the communication in a way that minimizes the stress (eg they may be more willing to speed through the portion of the text in order to get the matter over with, or they may be less willing or less able to update their internal representations of the various legal concepts based on what the attorney tells them).96 In this way, psychological stress can be expected to have both a quantitative and a qualitative effect on cognitive communication: being anxious or worried can undercut the raw cognitive resources that the defendant has to begin with, and it can color the way in which the defendant thinks about and internalizes the information about their guilty plea. Again, note how this cursory analysis of how environmental stressors might impact communication exposes weak points within the law’s conceptualization of communication. Because the law does not identify a role of systemic pressures in communication outcomes, legal scholarship and interventions to improve those outcomes97 frame time pressure less as an active systemic risk that directly affects cognitive-communication resources and more as a passive systemic variable that dictates where and when the attorney might be able to pursue communication interventions.

Fortunately for the hypothetical defendant and their attorney, however, Part One’s model of cognitive communication can also analyze how systemic risks might be attenuated. Whereas the systemic factors considered in Part Two create risk by increasing the likelihood that a person will face cognitive-communication burden, systemic factors that reduce the likelihood of such burden can be expected to attenuate that risk. Consequently, understanding how the system might produce better communication outcomes is a relatively straightforward matter of considering how improvements or modifications might decrease the overall amount of cognitive-communication hurdles that persons must clear in order to navigate legal contexts.

III. SYSTEMIC COMMUNICATION INTERVENTIONS

Part Three briefly examines how interventions might be used to reduce the impact of the systemic risks discussed in Part Two. The analysis will use the cognitive-communication model to illustrate how the law can modify its structural characteristics in order to alleviate pressure on the functions that support communication. Not only would such interventions improve the chance of better-quality cognitive communication, but they would also help the system better align the people in it with the expectations of the various legal standards that define and govern communication.

III.A. Interventions to reduce systemic risk from legal language

Because the language that the law uses is ultimately arbitrary—that is, the language does not exist independently of the human actors that create and dictate it—legalese is a logical and relatively straightforward target for cognitive-communication interventions. One potential intervention is slower communication. Slower communication encompasses a range of possible adaptations: slower speaking rate, adding breaks or pauses, repeating key phrases or parts, and allowing additional time for responses or for reading. These accommodations alleviate demand on numerous resources within the ‘accessing information’ group of cognitive functions, giving laypersons additional opportunity to hold, manipulate, and decode information and reducing the amount of information that their cognitive workplace needs to accommodate;98 for the hypothetical defendant, slower communication (eg reviewing half the statements, taking a five-minute break, then reviewing the rest) would mean fewer words (and less information) from the plea-questionnaire form per given unit of time. Similarly, slower communication allows for greater opportunity to build mental representations that are of greater detail and complexity;99 for the hypothetical defendant, slower communication would give them a longer opportunity to build internal perceptions of concepts such as ‘the right to remain silent’ and ‘guilty beyond a reasonable doubt’, as well as a longer opportunity to revise or update those internal perceptions as their attorney adds additional information.100 Effectively, slower communication gives the lay person greater opportunity to recruit cognitive resources throughout the entire model, reducing the height or the frequency of the hurdles that the various cognitive-communication functions must clear.

A second potential intervention is the use of communication with visual aids. Visual aids such as infographics—which are increasingly common comprehension-assist tools in other social contexts, such as healthcare101—provide concrete information that the lay person can use to supplement the abstract information that typically occurs in legalese; in other words, the lay person can use the visual aids to fill in any details that might be missing from their understanding or their internal visualizations.102 Similarly, visual aids can provide a useful example of what the law considers to be an accurate portrayal of a particular concept, so visual aids let the lay person ‘see’ what their understanding of a given legal language or concept should look like.103 For example, the plea-questionnaire statement that reads ‘I give up my right to make the State prove me guilty beyond a reasonable doubt’ might have a little graphic to illustrate the concept of ‘beyond a reasonable doubt.’ The graphic might show a set of scales, one side of which reads ‘Information that says I am innocent’ and the other of which reads ‘Information that says I am guilty’, with the ‘I am guilty’ side weighed down with a large stack of weight and the ‘I am innocent’ side supporting a much smaller stack of weight. The hypothetical defendant could then use the visual information portrayed in the graphic to ‘see’ what ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ means in the context of a criminal adjudication. By offering concrete, tangible representations on which lay people can rely,104 visual aids can reduce the height of the hurdles that the cognitive-communication functions must overcome.

A third potential intervention is the use of low-constraint communication. Low-constraint communication is communication whose structure and form solicits a wider range of potential responses (eg ‘What did you do yesterday?’, as compared to ‘Did you go to the park yesterday?’).105 Legal communication is overwhelmingly high-constraint,106 with legal actors relying predominantly on yes/no questions to elicit information and advance legal procedures, but such an approach can bias responses and challenge the responder’s capability to provide accurate, appropriate answers.107 Adopting low-constraint communication such as open-ended questions can be expected to ameliorate these potential risks: low-constraint communication allows the lay person greater opportunity to convert their internal representations into internal and external narratives and reduces the risk of ‘defaulting’ to acquiescent affirmatives typically seen in high-constraint language.108 Relatedly, low-constraint communication reduces burden on the cognitive-communication resources that oversee and monitor internal representations of communicated information by providing the opportunity to articulate and ‘double-check’ understanding. In the hypothetical defendant’s example, low-constraint communication might involve removing the check boxes that indicate understanding of the statements and adding a blank space in which the defendant can write in their own words what they understand about each statement. This would give the defendant more opportunity to interact with their own understanding as they prepare it for written communication, which reduces the likelihood that they would need to rely on an incomplete or incorrect understanding and which gives the attorney greater opportunity to catch potential mistakes or misunderstandings. By encouraging the sort of narrative responses humans tend to provide during normal communication—and expect to provide during their encounters with the law109—low-constraint communication allows cognitive-communication resources more freedom and flexibility to interact with and resolve legal information.

III.B. Interventions to reduce systemic risk from uneven communication dynamics

Given that the attorney-client dyad is the law’s preferred unit of communication analysis, interventions to close the gap between the attorney and the lay person are especially appropriate ways to encourage less systemic communication risk. One potential approach is to borrow aspects of accompaniment models of social advocacy, under which the relationship shifts from a vertical orientation with the lawyer as the expert professional and the lay person as the dependent client to a horizontal orientation in which both the lay person and the lawyer orient themselves around a shared goal.110 Under this orientation, the lawyer would be encouraged to communicate not just to help the client meet the law’s procedural requirements but also to empower the client to be an autonomous agent within their own legal proceeding,111 a framework for participation that largely overlaps with the client-centered priorities of procedural justice movements.112 During this intervention, the hypothetical defendant would be encouraged to fully articulate their conceptualizations of, impressions of, and understanding of their involvement in their own legal proceeding; effectively, the defendant would be given greater leeway to develop and express their mental representations of their constitutional rights and their guilty plea and their mental representation of those representations’ consequences and significance, putting fewer external barriers on their opportunity to utilize the ‘internalizing information’ and ‘interacting with information’ groups of cognitive-communication resources. Importantly, this communication orientation would also reduce the likelihood that the lawyer’s experience and knowledge would bias the communication because the attorney-client interaction would focus less on transmitting information from the attorney to the defendant and more on developing mutual understanding.113 For example, the defendant and the attorney might brainstorm how the client views constitutional rights and explore what that view means in the context of a plea. These various benefits to the defendant’s cognitive communication would reduce the risks associated with the law’s transactional method of communication.

Another potential solution to uneven communication dynamics is to recruit conversation partners to join the lay person’s legal communication. As part of clinical or rehabilitative support, communication partners help persons with communication difficulties or limitations to better participate in social interactions by working to support the person’s competencies.114 Not only could legal communication partners serve similar roles for persons in legal contexts, but they could also expand the traditional lawyer-client dyad and shift the dynamics of the communication toward a less-transactional arrangement. For example, the hypothetical defendant could be discussing the constitutional rights in the plea questionnaire alongside a spouse or a friend. The partner, who would ostensibly have better insight into the defendant’s cognitive-communication strengths and weaknesses, might be able to provide information or explanations in a way that facilitates the defendant’s ability to access, internalize, and interact with information (eg by referring them back to a relevant shared experience or using shared speech patterns). Such support would bolster the defendant’s cognitive-communication functions in a way that the lawyer’s legal training and expertise may not permit.

Finally, note that the interventions to reduce the burden of legal language will also reduce the burden of skewed communication dyads. Slower communication will reduce the attorney’s relative advantage in terms of accessing, internalizing, and using legal information; visual aids will minimize the need for the attorney to use communication based on experience and first-hand knowledge that the lay person does not have; and low-constraint communication will improve the lay person’s ability to convey the content and nature of their understandings to the attorney.

III.C. Interventions to reduce systemic risk from environmental stressors

Although environmental stress risk is probably the most difficult risk factor to modify or adapt, it is also the risk with the most self-evident solutions: in order to reduce systemic communication risks that arise from stressful, hurried environments, the law needs to be less stressful and less hurried. Is the hypothetical defendant’s attorney overworked? The system should fund more public defenders so that each one has more time per client. Is the client stressed about having to take time off work to attend a court hearing? The system should fund longer hours in the courthouse so that meetings and hearings can happen in the evenings or on the weekend. These solutions might not be easy to enact, but until the system contains fewer incidental stressors, those stressors will continue to act as yet more hurdles that people trying to navigate legal contexts have to overcome. Because there is no essentialist reason why legal contexts have to be perpetuated in ways that impose environmental cognitive-communication burden, improving the system’s environments is simply a matter of finding the will to invest more time and money in the legal actors who need it.

To briefly summarize, successful systemic interventions are those that reduce the likelihood that the law’s systemic characteristics will affect or burden the cognitive-communication resources that support communication. In considering possible interventions, however, it is critically important to underscore what the analyses of Parts 2 and 3 show about the relationship between the law as a system of communication interactions and the cognitive-communication functions that allow humans to navigate those interactions. Legal systems create systemic cognitive-communication risks because they force individuals into contexts that pressure the cognitive functions that underlie communication. This pressure arises from features that are inherent characteristics of those contexts, and as a result, systemic cognitive-communication risks are not predicated on the specific actions of individual legal actors. A judge, lawyer, or police officer will contribute to systemic risks simply by acting out their roles in a legal interaction: their individual behaviors may facilitate or inhibit good cognitive communication within the interaction, but because those behaviors exist within the confines of the legal system and its burdensome structural characteristics, individual actions will not in and of themselves affect the presence of systemic risk. This is the weakness of the law’s ontological conception of communication writ large: the law expects individual actors (notably, attorneys) to resolve communication hurdles that are inherent to the system itself. Compare such a viewpoint to other social contexts. Individual healthcare workers can treat people who are sickened by air pollution, and individual social workers can help secure food for people who live in food deserts, but these actions do not directly challenge the systemic forces that ultimately caused the harm in the first place. In these examples, it should be logical and obvious that broader systemic efforts—eg closing the polluting factory or funding new grocery stores—are required to ultimately reduce harm at the systemic level, and indeed, those systemic harms are frequent targets of public-health and public-wellness efforts.115 The law’s systemic risks, and the systemic harms that those risks likely perpetuate, are no different, and if the system truly seeks to protect its own civil and constitutional safeguards, then it must recognize the extent to which its systemic communication risks—and its conceptualization of communication—thwart those safeguards.

IV. CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Understanding how the law affects the resources humans recruit to access, internalize, and interact with legal information is a crucial step in improving social-legal behavioral outcomes. As discussed in this article’s analyses, however, the way in which the law frames communication as an atomized, transactional property ignores the extent to which the law itself taxes the cognitive resources that support and underlie communication. Not only does this oversight limit the system’s ability to consider interventions that might ameliorate its own systemic burden, but it also creates a pipeline in which persons with communication limitations—and the attorneys who must represent them—face uphill battles that are, when viewed through population-level legal outcomes, difficult at best and doomed at worst.116 Adopting frameworks that can appropriately recognize the interplay between context and communication, such as the model presented in this article, will help the law begin to shift its ontological definition of communication toward viewpoints that more accurately represent the cognitive resources that humans use to communicate, more realistically identify the way in which those cognitive resources help people navigate legal contexts, and more accurately assess how features of legal contexts make those resources more or less effective. In other words, such frameworks would make the system better able to safeguard the ‘deep roots and fundamental character’ of the notions of justice and fairness that the law’s conceptualization of communication purports to protect.117

This article ends with two concluding thoughts to encourage further introspection about the broader relationships among communication, human cognition, and the law. First, it is worth considering whether the US legal system’s framework of communication actually cares about meaningful communicative ability in the first place. The bar that lay persons have to clear in order to be judged communicatively competent enough to withstand the full force of the legal system’s weight is so abysmally low and so detached from clinical and scientific determinations118 that the law’s ontological framework for communication seems less a tool for safeguarding fundamental notions of fairness and justice and more a tool for guaranteeing that the gears of the system grind as smoothly and efficiently as possible—the fact that communicatively vulnerable populations are overrepresented within the carceral state is a grim piece of evidence to support such a conclusion. The legal ‘meaning’ of communication within the law’s purview is ultimately tautologic, but the apparent contradictions that arise from systemic analyses and data—for example, the profound disconnect between the serious concerns lawyers raise about their ability to effectively communicate with their clients and the determinations that the system makes about the legal permissibility of such representation119—suggest that the law’s ontology perpetuates a system in which communication challenges are a feature and not a flaw.

Second, it is worth reiterating that the most logical way to reduce inherent systemic risks is to change the system itself. Interventions like the ones suggested in Part Three would certainly be steps in the right direction, but because systemic communication risks are unavoidable results of the US legal system’s current manifestation, the only way to truly minimize systemic communication risks is to fundamentally change the system in which those risks arise. The fact that other countries have legal systems with radically different ontological frameworks for communication competency120 should make it clear that the United States’ legal system is not some essentialist configuration of how the law should view communication, and there are alternative legal ontologies that the US could consider if it had the political and cultural will to do so. The merits of the United States’ current legal framework may be worth philosophic debate, but the human cost is undeniable and sobering, and as scientific scholarship continues to generate data about the nature of human social-legal communication and the outcomes of legal systems, the contradictions between the law’s ontology and empirical observations may become more and more apparent and the law’s justifications of its own status quo may become less and less tenable. Should society and the law ever muster the willingness to change, however, the science underlying cognitive communication is one tool that could help make the system more representative of the cognitive resources through which humans encounter it.

Footnotes

David Mellinkoff, The Language of the Law (1963); J. M. Conley & W. M. O’Barr, Rules versus relationships: The ethnography of legal discourse (1990); J. M. Conley & W. M. O’Barr, Just Words: Law, language, and power (1998); S. U. Philips, Ideology in the Language of Judges: How Judges Practice Law, Politics, and Courtroom Control (1998).

Joseph A. Wszalek & Lyn S. Turkstra, Comprehension of social-legal exchanges in adults with and without traumatic brain injury, 33 Neuropsychology 934–946 (2019); Joseph A. Wszalek & Lyn S. Turkstra, Comprehension of Legal Language by Adults With and Without Traumatic Brain Injury, 34 J Head Trauma Rehabil E55–E63 (2019); Virginia G. Cooper & Patricia A. Zapf, Psychiatric Patients’ Comprehension of Miranda Rights, 32 Law and Human Behavior 390–405 (2008); R. Rogers et al., Knowing and Intelligent: A Study of Miranda Warnings in Mentally Disordered Defendants, 31 Law and Human Behavior 401–418 (2007); M. J. O’Connell, W. Garmoe & N. E. Goldstein, Miranda comprehension in adults with mental retardation and the effects of feedback style on suggestibility, 29 Law Hum Behav 359–69 (2005).

A. Colantonio et al., Traumatic brain injury and early life experiences among men and women in a prison population, 20 J Correct Health Care 271–9 (2014); Seena Fazel & John Danesh, Serious mental disorder in 23 000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys, 359 The Lancet 545–550 (2002); Richard B. Felson, Eric Silver & Brianna Remster, Mental Disorder and Offending in Prison, 39 Criminal Justice and Behavior 125–143 (2012); J. Jensen et al., Dyslexia among Swedish prison inmates in relation to neuropsychology and personality, 5 Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 452–461 (1999).

Joseph A. Wszalek & Lyn S. Turkstra, Language Impairments in Youths with Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Participation in Criminal Proceedings, 30 J Head Trauma Rehabil 86–93 (2015); Michele LaVigne & Gregory J. Van Rybroek, “He got in my face so I shot him:” How defendants’ language impairments impair attorney-client relationships, 17 CUNY Law Review 69–121 (2014); Michele LaVigne & Gregory J. Van Rybroek, Breakdown in the Language Zone: The Prevalence of Language Impairments among Juvenile and Adult Offenders and Why It Matters, 15 UC Davis Journal of Juvenile Law & Policy 37–124 (2011).

See Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36, 43 (2004).

Cooper v. Oklahoma, 517 U.S. 348, 364 (1996)(noting the ‘dire consequences’ of an inability to communicate with counsel and the need ‘to make myriad small[ ] decisions concerning the course of [the] defense’); Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 469 (1966)(noting the need for awareness not just of legal privilege but also of ‘the consequences of forging it’ and the need to be ‘acutely aware…of the adversarial system’); Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., The Common Law (1881) (‘The law considers, in other words, what would be blameworthy in the average man, the man of ordinary intelligence and prudence, and determines liability by that. If we fall below the level in those gifts, it is our misfortune’).

Medina v. California, 505 U.S. 437, 450 (1992)(‘Defense counsel will often have the best-informed view of the defendant’s ability to participate in his defense’); see also Model Rules of Prof’l Conduct R. 1.4 cmt (2014) (‘The guiding principle is that the lawyer should fulfill reasonable client expectations for information consistent with the duty to act in the client’s best interest and the client’s overall requirements as to the character of representation’); see also id, R. 1.14 (mandating that lawyers have the duty to maintain a normal client-lawyer relationship ‘as far as reasonably possible’ with clients with diminished capacity).

Mae C. Quinn, Reconceptualizing Competence: An Appeal, 66 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 259, 265 (2009); Harvard Law Review Association, Note, Incompetency to Stand Trial, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 454, 470 (1967)

M.A.K. Halliday, An Introduction to Functional Grammar (3rd ed. 2013); M.A.K. Halliday & R. Hasan, Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective (1985); Elizabeth Armstrong & Alison Ferguson, Language, meaning, context, and functional communication, 24 Aphasiology 480–496 (2010).

Conley and O’Barr (1990), supra note 1; Conley and O’Barr (1998), supra note 1.

LaVigne and Van Rybroek, supra note 4.

Joseph A. Wszalek, Soziale Kompetenz: A Comparative Examination of the Social-Cognitive Processes that Underlie Legal Definitions of Mental Competency in the United States, German, and Japan, 29 Fordham International Law Journal 102–132 (2015).

Sheila MacDonald, Introducing the model of cognitive-communication competence: A model to guide evidence-based communication interventions after brain injury, 31 Brain Inj 1760–1780 (2017).

MacDonald, supra note 13.

Cooper, supra note 6, at 354.

MacDonald, supra note 13.

Cooper, supra note 6, at 354.

MacDonald, supra note 13.

Cooper, supra note 6, at 354.

M. D’Esposito & B. R. Postle, The cognitive neuroscience of working memory, 66 Annu Rev Psychol 115–42 (2015); G. A. Radvansky & D.E. Copeland, Working Memory Span and Situation Model Processing, 117 The American Journal of Psychology 191–213 (2004).

Gloria Waters & David Caplan, The relationship between age, processing speed, working memory capacity, and language comprehension, 13 Memory 403–413 (2005); Leah D. Sheppard & Philip A. Vernon, Intelligence and speed of information-processing: A review of 50 years of research, 44 Personality and Individual Differences 535–551 (2008).