Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the association of physical activity and body image with psychological health outcomes and whether body image mediates the association of physical activity with psychological health among older female cancer survivors.

Materials and Methods:

Data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Life and Longevity after Cancer (LILAC) Study were used. Surveys assessed body image (appearance, attractiveness, scars), moderate-strenuous physical activity (min/week), and psychological health (depression, anxiety, distress). A mediation analysis was conducted to estimate the percentage of the total effect of physical activity on psychological health mediated by body image concerns.

Results:

Among 4,567 female cancer survivors aged 66–98 years, the average time since cancer diagnosis was 9.2 years. Approximately 50% reported no moderate-strenuous physical activity; 15% reported depressive symptoms, 6% reported anxiety, and 5% reported psychological distress; 3% had concerns with appearance, 20% had concerns with attractiveness, and 21% had concerns with scars. When unadjusted for body image concerns, every 30 min/week increase in physical activity was associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms (RR=0.93, 95%CI: 0.90–0.96), anxiety (RR=0.92, 95%CI: 0.87–0.97), and distress (RR=0.92, 95%CI: 0.87–0.98). Body image concerns with appearance mediated 7%, 8.8%, and 14.5% of the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms, anxiety, and distress, respectively.

Conclusion:

Older female cancer survivors reported body image concerns, which were associated with both physical activity and psychological health. Our findings suggest that interventions designed to address body image concerns in older female cancer survivors could serve to improve the benefit of physical activity on psychological health.

Keywords: body image concerns, physical activity, psychological health, cancer survivorship, mediation effect

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 25 years, cancer survival rates in the United States have increased significantly due to early detection, improved diagnosis, and treatment advances1. By 2026, it is projected that there will be more than 20 million cancer survivors in the United States2. Cancer survivors often experience psychological sequelae related to cancer and cancer-related treatment, such as anxiety, depression, and distress3, 4. Some cancer survivors also experience changes in appearance due to cancer treatment including surgical scars, changes in weight, hair loss, swelling, and skin discoloration from radiation, all of which may lead to body image concerns that negatively impact psychological health and quality of life5–8. Among breast cancer survivors, body image concerns have been associated with increased 10-year overall mortality9.

For cancer survivors, being physically active provides physical and psychological health benefits10. Physical activity after cancer diagnosis improves cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, physical function, and body image11–18. Physical activity also reduces cancer-related fatigue, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and alleviates emotional distress11, 16, 18–21. Additionally, physical activity may favorably impact psychological health through improved body image. However, the majority of studies that examined the relationship between body image and psychological health outcomes have been limited to younger survivors of cancer, or those with breast or head and neck diagnoses18, 22. Previous research has found that body image concerns were negatively associated with psychological health among older 23females23. Although older females have better appreciation of appearance and are more likely to ignore the social pressure about appearance, the changes in body image due to physical aging may lead to negative self-perception24–27. Thus, older female cancer survivors are a unique population that experience the combination of aging and cancer-related sequelae, and who potentially may benefit more from interventions to reduce body image concerns and improve psychological health. Although body image appears to stabilize two years post-cancer treatment, these concerns may persist over the long-term for some patients28–30. It is possible that associations between body image and psychological health among older, long-term female cancer survivors are different from those reported in younger cancer survivors.

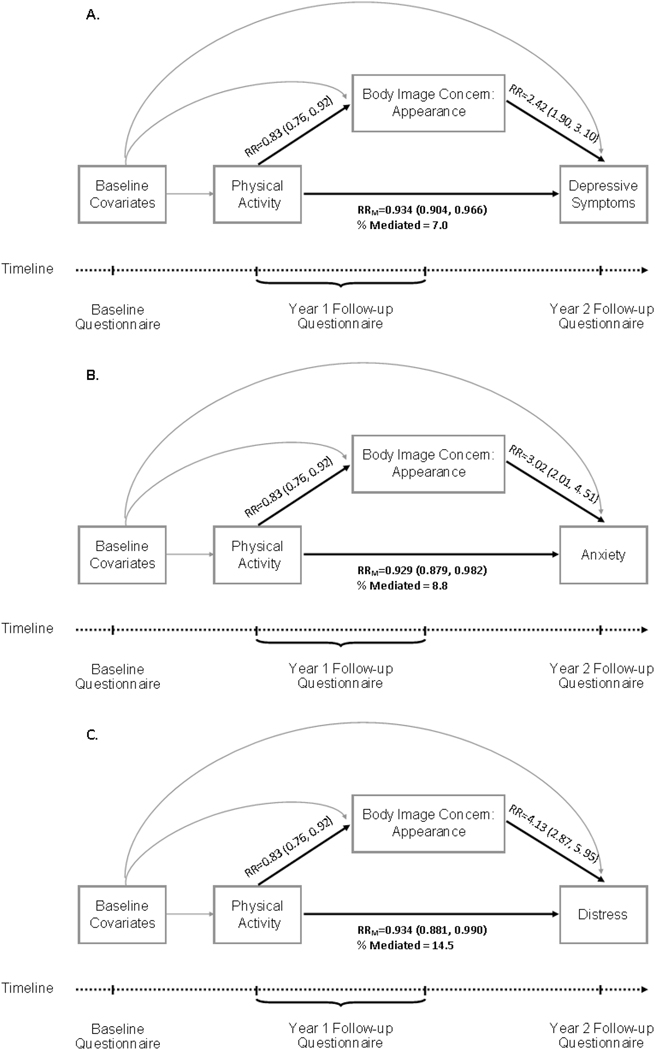

Several instruments and definitions have been used to evaluate body image among cancer survivors, including the Body Image Scale, Body Image and Relationship, and the Body Esteem Scale 31–33. To minimize participant burden, the current study used 3 questions to assess satisfaction of appearance, perception of physical attractiveness as a result of cancer or treatment, and dissatisfaction with appearance of any scars due to cancer treatment. We defined body image concerns as the affect and cognition of cancer survivors regarding their own physical appearance after cancer treatment 34, 35. The purpose of this study was: 1) to explore the associations between body image, physical activity, and psychological health outcomes; and 2) to explore whether body image mediates the association of physical activity with psychological health among older, long-term cancer survivors. We hypothesized that older female cancer survivors have body image concerns which may negatively affect their psychological health, and that body image mediates the association between physical activity and psychological health (Figure 1). The findings from our study could help health professionals and researchers identify strategies and design interventions to reduce body image concerns and improve psychological health among older female cancer survivors.

Figure 1.

Directed acyclic graph based on the hypothesis that the associations between physical activity and psychological outcomes (A: depressive symptoms, B: anxiety, C: distress) are (partly) mediated through body image concerns regarding overall appearance, adjusted for baseline covariates.

Arrow from physical activity to body image concern denotes the association between physical activity and body image concerns regarding overall appearance, with estimated relative risk (RR) adjusted for baseline covariates.

Arrow from body image concerns to psychological outcomes denotes the association between body image concerns regarding overall appearance and psychological outcomes, with estimated relative risk (RR) adjusted for baseline covariates.

Arrow from physical activity to psychological outcomes denotes the association between physical activity and psychological outcomes, with estimated relative risk (RRM) adjusted for mediator (body image concern) and baseline covariates.

% Mediated: percentage mediated by body image concern regarding overall appearance

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Data from the WHI and the WHI LILAC studies were used. The study design of the WHI and WHI LILAC have been described elsewhere36, 37. Briefly, between 1993 and 1998, the WHI recruited postmenopausal females age 50 and 79 years from 40 clinical centers into one or more randomized clinical trials (WHI-CT n=68,132) or an observational study (WHI-OS n=93,676). Participants were followed for up to 10 years within the WHI, and many continued follow-up in the WHI Extension Study.

In 2013, the WHI LILAC study enrolled WHI participants who had been diagnosed with select cancers (breast, endometrial, ovarian, lung, and colorectal cancers, melanoma, lymphoma, and leukemia). The goal of the WHI LILAC was to expand the existing WHI data to support studies of cancer outcomes, survivorship, and molecular epidemiology37. For the current study, participants were from the WHI LILAC study who had complete information on age, education, race, marital status, cancer site, cancer stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and self-reported cancer treatment, as well as physical activity and body image on the year-1 follow-up questionnaire, and psychological health on year-2 follow-up questionnaire. The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center’s Institutional Review Board approved the WHI and the WHI LILAC study. All participants in the WHI and the WHI LILAC provided written informed consent before any study activity.

Measurements

Physical activity was self-reported on LILAC year-1 follow-up questionnaire (Form 370), derived from the WHI Physical Activity Questionnaire, which was designed to measure weekly recreational physical activity among postmenopausal females and demonstrated adequate reliability38. Participants were asked “how often each week (7 days) do you usually do moderate or strenuous exercise? For example biking outdoors, using and exercise machine, aerobics, swimming, dancing, jogging, tennis”, and the duration of each session. The total minutes of moderate or strenuous exercise per week were calculated for each participant.

Body image was self-reported on LILAC year-1 follow-up questionnaire (Form 370) in three questions derived from the 10-item Body Image Scale39: concerns with overall appearance (“in general, how satisfied are you with your appearance?”), attractiveness due to cancer or treatment (“have you felt less physically attractive as a result of your cancer or treatment?”), and appearance of cancer scars (“have you been dissatisfied with the appearance of any scar(s) that resulted from your cancer treatments?”). Participants were asked to choose from “not at all”, “a little”, “quite a bit”, and “very much”. In this analysis, a binary variable was created for each subscale, as no concerns versus any concerns.

Psychological health, including depressive symptoms, anxiety, and distress were measured on LILAC year-2 follow-up questionnaire (Form 371). The Yale Depression Screener was used to determine depressive symptoms by asking participants if they often felt sad or depressed (yes/no). This one-item screener had 69% sensitivity and 90% specificity compared to the gold standard Geriatric Depression Scale (54% sensitivity and 93% specificity) 40–43. Anxiety and distress were determined by asking participants about their overall level of anxiety or distress during the past week, using a scale 0 (none) to 10 (worst). Participants were aware of the scale of classification as level of anxiety and distress were marked on the scale. These single-Item Linear Analog Self-Assessment has demonstrated high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability to assess anxiety and overall distress 40–42, 44. For the anxiety and distress variables, participants were classified as moderate or less (scale ≤5) versus more than moderate (scale >5), according to the validated single-item numerical linear analogue self-assessment scales45. All assessments can be accessed from the WHI study website (https://sp.whi.org/researchers/studydoc/SitePages/Forms.aspx).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics compared the differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between participants who reported no recreation moderate-strenuous physical activity (0 min/week) vs. any moderate-strenuous physical activity (≥ 1min/week). For continuous variables, means/standard deviations (SDs) were reported and t-tests were used to compare the average of covariates between groups; for categorical variables, frequencies were reported and the chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of level(s) of covariates between groups.

As psychological health was measured one year after self-reported physical activity and body image concerns, we were able to establish the temporal sequence of the exposures (physical activity), mediators (body image concerns), and outcomes (psychological health) (Figure 1.). Relative risk regression models with robust variance estimators were used to assess the association of physical activity with body image and psychological health and the association of body image with psychological health 46. The percentage of the total effect of physical activity on psychological health mediated by body image was estimated using the method described in Nevo et al47. When quantifying the associations of physical activity with body image and psychological health outcomes, the effect estimates correspond to 30 minute increase in physical activity per week (as continuous variable). The following covariates were adjusted for in all models: age, education, race, marital status, cancer site, cancer stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and self-reported cancer treatments (chemotherapy, radiation, and hormone therapy). Data on insurance status was summarized but not included in our analyses due to a high percentage of missingness (13%). Body mass index (BMI) on Form 370 was also summarized but not included in any of the analysis models since it may lie on the causal pathway between physical activity and psychological health. We were unable to conduct a priori subgroup analyses using cancer site and time since diagnosis stratification due to small sample sizes of each category. As a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of missing data on the results, the mediation analysis was repeated using 25 imputed data sets created by a fully conditional specification procedure48. Additional analyses using dichotomized physical activity (any moderate-strenuous physical activity vs. no moderate-strenuous activity) were conducted to determine whether the mediation effect of body image concerns changed. E-values were used to quantify the minimum strength that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both exposure and outcome to explain away observed associations49. Holm’s method was used to adjust for multiple of tests of mediation50.

All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC). Mediation analyses were conducted using the %mediate macro, publicly-available online at https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/donna-spiegelman/software/mediate/.

RESULTS

Out of 8,043 mailed baseline LILAC questionnaires, 6,349 (78.9%) were returned, and 4,567 had complete data on study variables, and thus, were included in the current analysis. There were some differences between those who were included and excluded from our analysis, most notably in age, race, and cancer diagnosis (Appendix A).

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Among the 4,567 participants in our analysis, the average age at the LILAC year-1 follow-up was 78.4±5.7 (range 66–98) years. The majority were White, married, with some college education. The average time between cancer diagnosis and LILAC year-1 follow-up was 9.2±4.9 (range 1.4–21.1) years. The most common cancer diagnosis was breast cancer (60.2%), followed by colorectal (10.2%), endometrial (9.3%), melanoma (6.7%), lymphoma (4.8%), lung (4.4%), ovarian (2.4%), and leukemia (2.0%).

At LILAC year-1 follow-up, 2,286 (50.1%) participants reported no moderate-strenuous physical activity, 1,829 (40.1%) were physically inactive (1–149 min/week), 417 (9.1%) were physically active (≥150 min/week), and 35 (0.8%) had some physical activity but could not be further classified due to missing data on exercise duration (Table 1). Participants with older age, high school or less education, not married, and with a greater BMI were more likely to report no moderate-strenuous physical activity (all P<0.001). Compared to breast cancer survivors, greater proportions of females with colorectal, ovarian, endometrial, or lung cancer reported no moderate-strenuous physical activity (54%, 56.4%, 51.5%, 57.3% vs. 49.4%, P=0.017).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics by Physical Activity Level

| Parameter | Level | Moderate/Strenuous Physical Activity | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None, n=2286 | Any, n=2281 | |||

| Age, years, mean ± sd | 79.0 ± 5.8 | 77.8 ± 5.6 | <0.001 | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| College or Associates Degree | 1862 (47.4) | 2063 (52.6) | <0.001 | |

| High school/Less than HS | 424 (66.0) | 218 (34.0) | ||

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Black or African American | 79 (48.5) | 84 (51.5) | 0.610 | |

| Other1 | 106 (53.3) | 93 (46.7) | ||

| White (not of Hispanic origin) | 2101 (50.0) | 2104 (50.0) | ||

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||

| Married or living as married | 1068 (46.6) | 1224 (53.4) | <0.001 | |

| Widowed | 811 (55.2) | 657 (44.8) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 300 (50.3) | 297 (49.7) | ||

| Never married | 107 (51.0) | 103 (49.0) | ||

| BMI2, kg/m2, mean ± sd | 27.3 ± 6.2 | 25.8 ± 5.1 | <0.001 | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Breast Cancer | 1357 (49.4) | 1391 (50.6) | 0.017 | |

| Colorectal Cancer | 252 (54.0) | 215 (46.0) | ||

| Ovarian Cancer | 62 (56.4) | 48 (43.6) | ||

| Endometrial Cancer | 220 (51.5) | 207 (48.5) | ||

| Leukemia | 40 (44.4) | 50 (55.6) | ||

| Lung Cancer | 114 (57.3) | 85 (42.7) | ||

| Lymphoma | 110 (50.0) | 110 (50.0) | ||

| Melanoma | 131 (42.8) | 175 (57.2) | ||

| Stage, n (%) | ||||

| In Situ/Localized | 1661 (49.8) | 1676 (50.2) | 0.824 | |

| Regional | 464 (50.8) | 449 (49.2) | ||

| Distant | 161 (50.8) | 156 (49.2) | ||

| Time Since Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| < 5 years | 627 (51.7) | 585 (48.3) | 0.147 | |

| 5–10 years | 694 (50.9) | 669 (49.1) | ||

| > 10 years | 965 (48.4) | 1027 (51.6) | ||

| Insurance, n (%) | ||||

| No Insurance | 18 (51.4) | 17 (48.6) | 0.059 | |

| Private | 196 (48.6) | 207 (51.4) | ||

| Public | 737 (47.5) | 814 (52.5) | ||

| Public+Private | 1031 (52.0) | 950 (48.0) | ||

| Radiation Therapy, n (%) | 1093 (48.9) | 1141 (51.1) | 0.135 | |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 688 (50.8) | 665 (49.2) | 0.486 | |

| Hormone Therapy, n (%) | 938 (48.5) | 998 (51.5) | 0.063 | |

Other race (n=199) include American Indian or Alaskan Native (n=8), Asian or Pacific Islander (n=85), Hispanic/Latino (n=67), and Other (n=39).

4110 women had BMI data: no moderate-strenuous physical activity (n=2043), any physical activity (n=2067)

A total of 1474 (32.3%) participants reported at least one of the three body image concerns. Specifically, 137 (3.0%) participants reported body image concerns related to overall appearance, 920 (20.1%) reported body image concerns related to attractiveness, and 968 (21.2%) reported concerns regarding cancer scars (Appendix B). Body image concerns regarding attractiveness and cancer scars differed across cancer sites (P<0.001), but there was no significant difference in body image concerns related to overall appearance across cancer sites (P=0.83) (Appendix B). Ovarian cancer survivors had the largest proportion with concerns related to attractiveness (26.4%), followed by breast cancer (23.8%), lymphoma (20.0%), leukemia (18.9%), and melanoma (16.0%). Breast cancer survivors had the largest proportion with concerns related to cancer scars (26.6%), followed by melanoma (25.8%), and ovarian cancer (16.4%). Body image concerns related to cancer scars differed by time since diagnosis (P=0.004) (Appendix C). Cancer survivors with a cancer diagnosis 10 or more years ago had the largest proportion regarding any concerns related to cancer scars (22.8%), followed by those with a cancer diagnosis between 5–10 years ago (21.8%), and lowest among those who had cancer diagnosed less than 5 years ago (17.9%). Body image concerns related to overall appearance and attractiveness did not differ by time since cancer diagnosis.

At LILAC year-2 follow-up, 687 (15.0%) participants reported depressive symptoms, 268 (5.9%) reported more than moderate anxiety, and 239 (5.2%) reported more than moderate psychological distress (Appendix B). There were no significant differences in depressive symptoms, anxiety, or psychological distress across cancer sites (Appendix B). Similarly, no difference was observed by time since cancer diagnosis in depressive symptoms, anxiety, or psychological distress (Appendix C).

The Association of Physical Activity with Body Image Concerns

After adjusting for age and other covariates, with every 30 min/week increase in moderate-strenuous physical activity, participants had 17% lower risk of body image concerns regarding overall appearance (RR=0.83, 95%CI: 0.76–0.92). However, the E-value was 1.39 which indicates that an unmeasured confounder could explain away this association if it is moderately associated with physical activity and concerns about appearance. No significant association was observed between physical activity and body image concerns related to attractiveness (RR=0.98, 95%CI: 0.96–1.00) or concerns about cancer scars (RR=1.01, 95%CI: 0.99–1.03) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Association between Physical Activity (min/week of moderate or strenuous activity) and Body Image Concerns

| Body Image Concerns | n (%) | PA, min/week media [IQR] | Crude | Adjusted2 | E-value 3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) 1 | P-value | RR (95% CI) 1 | P-value | |||||

| Appearance | Yes | 137 (3.0%) | 0 [0 – 28.5] | 0.83 (0.75, 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.76, 0.92) | <0.001 | 1.39 |

| No | 4430 (97.0%) | 9.5 [0 – 99] | ||||||

| Attractiveness | Yes | 920 (20.1%) | 9.5 [0 – 99] | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) 4 | 0.505 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.077 | 1 |

| No | 3647 (79.9%) | 0 [0 – 99] | ||||||

| Scar appearance | Yes | 968 (21.2%) | 19 [0 – 99] | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 0.026 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.426 | 1 |

| No | 3599 (78.8%) | 0 [0 – 99] | ||||||

Corresponds to 30 minute increase in PA per week;

Analysis performed on complete cases (N=4532), adjusted for age, education, race, marital status, cancer diagnosis, cancer stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and self-reported cancer treatment;

E-value for upper bound of CI for adjusted RR if RR < 1; E-value for lower bound if RR>1; E-value provides the association an unmeasured confounder must have with both the outcome and exposure, conditional on the covariates in the model, in order to explain away the exposure-outcome association

RR < 1 due to higher mean among those who are not concerned about attractiveness: 54.5 vs. 52.7

The Association of Body Image Concerns with Psychological Health Outcomes

Compared to participants who had no body image concerns about overall appearance, participants who had any concerns about appearance had a higher risk of reporting depressive symptoms (RR=2.42, 95%CI: 1.90–3.10), anxiety (RR=3.02, 95%CI: 2.01–4.51), and psychological distress (RR=4.13, 95%CI: 2.87–5.95) after adjustment for covariates (Table 3). Similarly, concerns about attractiveness were associated with increased risk of depressive symptoms (RR=1.90, 95%CI: 1.63–2.21), anxiety (RR=1.83, 95%CI: 1.41–2.38), and psychological distress (RR=1.92, 95%CI: 1.46–2.54). Concerns about cancer scars were also associated with increased risk of depressive symptoms (RR=1.44, 95%CI: 1.23–1.69), anxiety (RR=1.50, 95%CI: 1.16–1.96), and psychological distress (RR=1.99, 95%CI: 1.52–2.60). The E-values for these associations were relatively large which suggests that these associations are fairly robust.

Table 3.

The Association of Body Image Concerns with Psychological Health Outcomes

| No | Crude | Adjusted 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator | Psychological Outcome | Concern n (%) | Concer n n (%) | RR (95% CI) | P-value | RR (95% CI) | P-value | E-value 2 | |

| Body Image Concerns about Appearance | |||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | Yes | 47 (34.3) | 640 (14.4) | 2.37 (1.86, 3.03) | <0.001 | 2.42 (1.90, 3.10) | <0.001 | 3.20 | |

| No | 90 (65.7) | 3790 (85.6) | |||||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 22 (16.1) | 246 (5.6) | 2.89 (1.94, 4.32) | <0.001 | 3.02 (2.01, 4.51) | <0.001 | 3.44 | |

| No | 115 (83.9) | 4184 (94.4) | |||||||

| Distress | Yes | 27 (19.7) | 212 (4.8) | 4.12 (2.87, 5.92) | <0.001 | 4.13 (2.87, 5.95) | <0.001 | 5.18 | |

| No | 110 (80.3) | 4218 (95.2) | |||||||

| Body Image Concerns about Attractiveness | |||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | Yes | 211 (22.9) | 476 (13.1) | 1.76 (1.52, 2.03) | <0.001 | 1.90 (1.63, 2.21) | <0.001 | 2.65 | |

| No | 709 (77.1) | 3171 (86.9) | |||||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 81 (8.8) | 187 (5.1) | 1.72 (1.34, 2.21) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.41, 2.38) | <0.001 | 2.17 | |

| No | 839 (91.2) | 3460 (94.9) | |||||||

| Distress | Yes | 75 (8.2) | 164 (4.5) | 1.81 (1.39, 2.36) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.46, 2.54) | <0.001 | 2.28 | |

| No | 845 (91.8) | 3483 (95.5) | |||||||

| Body Image Concerns about Scar from Treatment | |||||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | Yes | 179 (18.5) | 508 (14.1) | 1.31 (1.12, 1.53) | 0.001 | 1.44 (1.23, 1.69) | <0.00 1 | 1.76 | |

| No | 789 (81.5) | 3091 (85.9) | |||||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 74 (7.6) | 194 (5.4) | 1.42 (1.10, 1.84) | 0.008 | 1.50 (1.16, 1.96) | 0.002 | 1.58 | |

| No | 894 (92.4) | 3405 (94.6) | |||||||

| Distress | Yes | 78 (8.1) | 161 (4.5) | 1.80 (1.39, 2.34) | <0.001 | 1.99 (1.52, 2.60) | <0.001 | 2.41 | |

| No | 890 (91.9) | 3438 (95.5) | |||||||

Adjusted model contains covariates including age, education, race, marital status, cancer diagnosis, cancer stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and self-reported cancer treatment

E-value for upper bound of CI for adjusted RR if RR < 1; E-value for lower bound if RR>1; E-value provides the association an unmeasured confounder must have with both the outcome and exposure, conditional on the covariates in the model, in order to explain away the exposure-outcome association

Mediation Effect of Body Image Concerns on the Association between Physical Activity and Psychological Outcomes

With every 30 min/week increase in physical activity, participants had 7.1% lower risk of depressive symptoms, adjusting for baseline covariates (RRU =0.93, 95%CI: 0.90–0.96). When accounting for the mediation effect of body image concerns about appearance, every 30 min/week increase in physical activity was associated with 6.6% lower risk of depressive symptoms (RRM=0.93, 95%CI: 0.90–0.97). The proportion of the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms mediated by body image concerns about appearance was 7% (Table 4, Figure 1A).

Table 4.

Percentage of the Association of Physical Activity (min/week of moderate or strenuous activity) with Psychological Health Mediated through Body Image Concerns

| Psychological Outcome | RRu (95% CI) 1 | p-value | E-value 2 | Mediator | RRm (95% CI) 3 | % Mediated 4 | Raw P 5 | Adj. P 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA→ Depressive Symptoms | ||||||||

| 0.929 (0.899, 0.961) | <0.001 | 1.25 | Appearance | 0.934 (0.904, 0.966) | 7.0 | 0.004 | 0.031 | |

| Attractiveness | 0.931 (0.900, 0.963) | 2.6 | 0.157 | 0.945 | ||||

| Scar | 0.928 (0.898, 0.960) | −1.8 | 0.879 | 1.000 | ||||

| PA→ Anxiety | ||||||||

| 0.922 (0.873, 0.975) | 1.19 | Appearance | 0.929 (0.879, 0.982) | 8.8 | 0.010 | 0.070 | ||

| 0.004 | Attractiveness | 0.924 (0.873, 0.978) | 2.3 | 0.175 | 0.945 | |||

| Scar | 0.921 (0.871, 0.974) | −2.1 | 0.877 | 1.000 | ||||

| PA→ Distress | ||||||||

| Appearance | 0.934 (0.881, 0.990) | 14.5 | 0.003 | 0.031 | ||||

| 0.923 (0.870, 0.979) | 0.008 | 1.17 | Attractiveness | 0.925 (0.871, 0.982) | 2.3 | 0.193 | 0.945 | |

| Scar | 0.921 (0.867, 0.978) | −3.0 | 0.851 | 1.000 | ||||

Analysis performed on complete cases (N=4567)

RRU: relative risk not adjusted for mediator (body image concern)

E-value for upper bound of CI for adjusted RR if RR < 1; E-value for lower bound if RR>1; E-value provides the association an unmeasured confounder must have with both the outcome and exposure, conditional on the covariates in the model, in order to explain away the exposure-outcome association

RRM: relative risk adjusted for mediator

% Mediated = 100(1- logRRM/log RRU)

Raw P: one-sided test of % Mediated≥0 (logRRu > logRRM)

Adj. P: adjusted for multiple testing using Holm’s method

All models adjusted covariates including age, education, race, marital status, cancer diagnosis, cancer stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and self-reported cancer treatment. RRs correspond to 30 minute increase in PA per week.

Similarly, body image concerns about appearance mediated the association of physical activity with anxiety and psychological distress. When accounting for the mediation effect of body image concerns about appearance, every 30 min/week increase in physical activity was associated with 7.1% lower the risk of anxiety (RRM=0.93, 95%CI: 0.88–0.98) and 6.6% lower the risk of psychological distress (RRM=0.93, 95%CI: 0.88–0.99). The proportion mediated by concerns about appearance was 8.8% for the association between physical activity and anxiety (Table 4, Figure 1B), and 14.5% for the association between physical activity and psychological distress (Table 4, Figure 1C). The E-values for the associations between physical activity and psychological outcomes were modest.

However, the body image concerns about attractiveness and scars did not mediate the association between physical activity and psychological outcomes (P% mediated>0.05). Sensitivity analyses showed no meaningful differences in the mediation analysis between imputation results and the complete case analysis (Appendix D). Additional analyses comparing any moderate-strenuous physical activity vs. no moderate-strenuous physical activity showed similar results, though the mediation effects of overall appearance on the association between physical activity and psychological outcomes were only marginally significant (p < 0.1) due to the loss in power in dichotomizing the exposure (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our study examined the association between physical activity, body image, and psychological health outcomes among older, long-term female cancer survivors. Our findings support the hypothesis that older female cancer survivors continue to experience body image concerns, which are associated with poor psychological health outcomes, years after the initial diagnosis of cancer. The associations of physical activity with psychological health outcomes, specifically depressive symptoms, anxiety, and distress, were partially mediated by body image concerns related to the overall appearance, although the mediator explained modest proportions of the associations (range from 7.0–14.5%). These findings suggest that reducing body image concerns could be one component of behavioral interventions that focus on increasing physical activity, and serve as an indirect path, to improve psychological health and quality of life among older, long-term female cancer survivors.

During the immediate postoperative and completion of cancer treatment periods, cancer survivors, especially younger survivors, experienced body image concerns51–53. Few studies have examined body image concerns further into survivorship. Using the WHI LILAC survivorship cohort, we were able to investigate body image concerns and the associated psychological health outcomes among older, long-term female cancer survivors. Unlike younger breast cancer survivors (average age 51 years old) where body image concerns were relatively stable 2-years after treatment completion30, in our study of older cancer survivors (average age 78 years old), participants who were >10 years since cancer diagnosis had the highest rate of body image concerns regarding cancer scars (22.8%), whereas participants who had been diagnosed more recently (<5 years since cancer diagnosis) reported the lowest rate (17.9%).

Our study compared results related to body image concerns across cancer sites (e.g., breast, colorectal, endometrial, leukemia, lung, lymphoma, melanoma, and ovarian cancer), whereas previous studies were predominantly conducted within one site22, 52. We observed differences in body image concerns regarding attractiveness (ranging from 10.1–26.4%) and cancer scars (ranging from 6.0–26.6%) across cancer sites, but no difference in concerns regarding appearance (ranging from 0.9–3.6%). Despite these variations, all body image concerns were associated with increased risks of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and psychological distress. These findings are consistent with previous studies in younger breast cancer survivors that reported body image concerns might be associated with increased risk of anxiety, depression, quality of life, and sexual difficulties6–8.

Our findings demonstrate the importance of managing body image concerns for psychological health, even for older, long-term female cancer survivors. Strategies to address these concerns among cancer survivors could be implemented in clinical settings. For example, standard assessment of body image concerns for cancer survivors should be developed and implemented in clinical settings. Body image concerns and psychological health could be evaluated from cancer survivors at each clinical visit. For those who report moderate or high levels of body image concerns or psychological issues, providers could discuss these concerns and connect patients to psychological resources (e.g., mental health counselors, psychologists), if warranted. Although patient-provider communication is critical for addressing body image concerns, studies have shown that few providers address these concerns with cancer survivors54, 55. These conversations may happen even less frequently between older cancer survivors and providers. As body image is a prevalent and persistent issue among older cancer survivors and is associated with poorer psychological health, it is crucial that providers recognize these concerns among older survivors. Providers who treat older cancer survivors, including oncologists, surgeons, and primary care providers, need to be trained to communicate with older cancer survivors about body image concerns and psychological health. Besides, providers should be encouraged to refer cancer survivors to behavioral interventions (e.g., exercise) during survivorship that combine psychological components, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, to address body image concerns, increase physical activity, and improve self-efficacy of body image and health behaviors. Such interventions may lead to increased physical activity, reduced body image concerns, and improved psychological outcomes.

Our study has notable strengths as well as limitations. First, we had a large sample size of older female cancer survivors, which allowed us to evaluate body image concerns across cancer sites and time since cancer diagnosis. We took advantage of the longitudinal data collection by examining the relationship between physical activity level and body image concerns assessed before the reported psychological outcomes, which strengthened the exploration of the association. In addition, LILAC includes eight cancer sites (breast, colorectal, endometrial, leukemia, lung, lymphoma, melanoma, and ovarian cancer), which advances the literature about body image and psychological outcomes beyond breast cancer.

However, the LILAC study relied on self-reported data, which may lead to recall and survivor bias. As most studies with an observational design, unmeasured confounding may introduce hidden bias in observed associations. We used the E-value to assess how strong an unmeasured confounder would have to be to explain away an observed association. Although the association between body image concerns and psychological health outcomes were fairly robust to unmeasured confounders (indicated by the large E-values), we found unmeasured confounders could explain away the associations between physical activity with body image and physical activity with psychological outcomes (indicated by modest to moderate E-values). Future studies with additional assessments of unmeasured factors, such as self-efficacy, perception of identity and self-image, and frailty, are necessary to understand the underlying mechanisms of body image concerns, physical activity, and psychological health in this population. In addition, our study did not use detailed surgical information. It is possible that cancer survivors who underwent aggressive surgical procedures had more body image concerns compared to those who underwent minimally invasive procedures. Similarly, changes in standard cancer treatment in the last two decades may also influence the perception of body image and psychological health among older cancer survivors. Although we controlled for years since cancer diagnosis as a covariate, we did not examine the effect of specific cancer treatment on body image and psychological health.

LILAC also utilized one-item questions about psychological health outcomes of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and distress, which impedes our ability to compare our results to previous studies. For example, common screening methods for depression include semi-structured diagnostic interviews, Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale – depression subscale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, and the PHQ 56–59. The Geriatric Anxiety Scale and Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale- anxiety subscale were used to evaluate anxiety among older cancer survivors 58, 60, and Cancer-Related Worries was used and considered as an alternative measure of general distress 61, 62. As most studies reported mean scores, we are not able to compare our results. Although Trevino used a similar scale to assess distress to our study, their study population was older patients with cancer who were undergoing surgery 63. It is likely that distress differs between long-term older cancer survivors and older patients with cancer who are undergoing surgery. Therefore, we were not able to compare our findings on psychological health with previous studies.

Although the LILAC study has multiple data collection points, the level of physical activity and body image concerns were only reported at the year-1 follow-up survey, whereas the psychological outcomes were reported at the baseline and the year-2 follow-up surveys. Thus, we were unable to establish the temporality between physical activity and body image concerns or to examine associations of changes in physical activity or body image on psychological outcomes. Future studies with repeated measures over time would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how changes in physical activity and body image are associated with psychological outcomes. Additionally, the majority of the participants were White, non-Hispanic, educated, older, breast cancer survivors, which limited our ability to generalize the findings to other populations. Future studies are needed to understand the differences of the effects of aging and cancer on body image concerns in older females, perhaps through measures of body image concerns related to aging and cancer or comparisons of those with and without cancer. This will help identify and design different strategies to address these concerns and improve psychological health outcomes for older female with and without cancer.

In conclusion, older, long-term female cancer survivors experienced body image concerns. Body image was associated with both physical activity and psychological health. Body image concerns about appearance mediated the association between physical activity and psychological health outcomes. Our findings highlight the need for clinicians and researchers to address body image concerns in older female cancer survivors, perhaps through physical activity interventions, to determine whether these interventions are associated with improvements in psychological health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, and HHSN268201600004C. This research was also funded in part by a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Funding: The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HSN268201600003C, and HHSN268201600004C. The WHI Life and Longevity after Cancer (LILAC) study is funded by UM1 CA173642 and a grant to EDP from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (F99CA253745-01 to XZ).

Conflict of Interest

Electra Paskett would like to disclose that she has grant funding from the Merck Foundation and Pfizer. All other authors report there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Robison LL. Cancer survivorship: unique opportunities for research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. July2004;13(7):1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States: AACR; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornblith AB, Powell M, Regan MM, et al. Long-term psychosocial adjustment of older vs younger survivors of breast and endometrial cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(10):895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JC, Winters-Stone K, Lee A, Schmitz KH. Cancer, physical activity, and exercise. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates G, Taub RN, West H. Intimacy, body image, and cancer. JAMA Oncology. 2016;2(12):1667–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begovic-Juhant A, Chmielewski A, Iwuagwu S, Chapman LA. Impact of body image on depression and quality of life among women with breast cancer. Journal of psychosocial oncology. 2012;30(4):446–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi EK, Kim IR, Chang O, et al. Impact of chemotherapy-induced alopecia distress on body image, psychosocial well-being, and depression in breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23(10):1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stan D, Loprinzi CL, Ruddy KJ. Breast cancer survivorship issues. Hematology/Oncology Clinics. 2013;27(4):805–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cousson-Gelie F, Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Dilhuydy JM, Jutand M-A. Do anxiety, body image, social support and coping strategies predict survival in breast cancer? A ten-year follow-up study. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(3):211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2019;51(11):2375–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehnert A, Veers S, Howaldt D, Braumann K-M, Koch U, Schulz K-H. Effects of a physical exercise rehabilitation group program on anxiety, depression, body image, and health-related quality of life among breast cancer patients. Oncology Research and Treatment. 2011;34(5):248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speck RM, Gross CR, Hormes JM, et al. Changes in the Body Image and Relationship Scale following a one-year strength training trial for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedema. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;121(2):421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Puymbroeck M, Schmid A, Shinew K, Hsieh P-C. Influence of Hatha yoga on physical activity constraints, physical fitness, and body image of breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. International journal of yoga therapy. 2011;21(1):49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown JC, Schmitz KH. Weight lifting and physical function among survivors of breast cancer: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(19):2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, et al. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;132(1):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandel SL, Judge JO, Landry N, Faria L, Ouellette R, Majczak M. Dance and movement program improves quality-of-life measures in breast cancer survivors. Cancer nursing. 2005;28(4):301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews CE, Wilcox S, Hanby CL, et al. Evaluation of a 12-week home-based walking intervention for breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2007;15(2):203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cormie P, Zopf EM, Zhang X, Schmitz KH. The impact of exercise on cancer mortality, recurrence, and treatment-related adverse effects. Epidemiologic reviews. 2017;39(1):71–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors—a meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(2):115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buffart LM, Van Uffelen JG, Riphagen II, et al. Physical and psychosocial benefits of yoga in cancer patients and survivors, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC cancer. 2012;12(1):559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra SI, Scherer R, Geigle P, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fingeret MC, Teo I, Epner DE. Managing body image difficulties of adult cancer patients: lessons from available research. Cancer. 2014;120(5):633–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabik NJ. Ageism and body esteem: Associations with psychological well-being among late middle-aged African American and European American women. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2015;70(2):189–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liechty T. “Yes, I worry about my weight… but for the most part I’m content with my body”: Older Women’s Body Dissatisfaction Alongside Contentment. Journal of Women & Aging. 2012;24(1):70–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liechty T, Yarnal CM. The role of body image in older women’s leisure. Journal of leisure research. 2010;42(3):443–467. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Runfola CD, Von Holle A, Trace SE, et al. Body dissatisfaction in women across the lifespan: Results of the UNC-SELF and gender and body image (GABI) studies. European Eating Disorders Review. 2013;21(1):52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiggemann M, Lynch JE. Body image across the life span in adult women: the role of selfobjectification. Developmental psychology. 2001;37(2):243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unukovych D, Sandelin K, Liljegren A, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients with a family history: a prospective 2-years follow-up study of health related quality of life, sexuality and body image. European Journal of Cancer. 2012;48(17):3150–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam WW, Li WW, Bonanno GA, et al. Trajectories of body image and sexuality during the first year following diagnosis of breast cancer and their relationship to 6 years psychosocial outcomes. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;131(3):957–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falk Dahl CA, Reinertsen KV, Nesvold IL, Fosså SD, Dahl AA. A study of body image in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2010;116(15):3549–3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hormes JM, Lytle LA, Gross CR, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, Schmitz KH. The body image and relationships scale: development and validation of a measure of body image in female breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. March102008;26(8):1269–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson A, Williams J. Factors affecting quality of life in patients experiencing facial disfigurement due to surgery for head and neck cancer. Br J Nurs. February142019;28(3):180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinto BM, Trunzo JJ. Body esteem and mood among sedentary and active breast cancer survivors. Mayo Clin Proc. February2004;79(2):181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cash TF. Body image: Past, present, and future: Elsevier; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banfield SS, McCabe M. An evaluation of the construct of body image. Adolescence. 2002;37(146):373–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Study TWsHI. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Controlled clinical trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paskett ED, Caan BJ, Johnson L, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Life and Longevity After Cancer (LILAC) study: description and baseline characteristics of participants. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2018;27(2):125–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer A-M, Evenson KR, Morimoto L, Siscovick D, White E. Test-retest reliability of the WHI Physical Activity Questionnaire. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2009;41(3):530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. European journal of cancer. 2001;37(2):189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sloan J. Asking the obvious questions regarding patient burden. J Clin Oncol. January12002;20(1):4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. July242000;160(14):2101–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorkin DH, Pham E, Ngo-Metzger Q. Racial and ethnic differences in the mental health needs and access to care of older adults in california. J Am Geriatr Soc. December2009;57(12):2311–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahoney J, Drinka TJ, Abler R, et al. Screening for depression: single question versus GDS. J Am Geriatr Soc. September1994;42(9):1006–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer. May151998;82(10):1904–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh JA, Satele D, Pattabasavaiah S, Buckner JC, Sloan JA. Normative data and clinically significant effect sizes for single-item numerical linear analogue self-assessment (LASA) scales. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2014;12(1):187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. April12004;159(7):702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nevo D, Liao X, Spiegelman D. Estimation and inference for the mediation proportion. The international journal of biostatistics. 2017;13(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Statistical methods in medical research. 2007;16(3):219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Annals of internal medicine. 2017;167(4):268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian journal of statistics. 1979:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D’onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(7):579–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis C, Tami P, Ramsay D, et al. Body image in older breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Psychooncology. May 2020;29(5):823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hawighorst-Knapstein S, Fusshoeller C, Franz C, et al. The impact of treatment for genital cancer on quality of life and body image—results of a prospective longitudinal 10-year study. Gynecologic oncology. 2004;94(2):398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roter D, Hall JA. Doctors talking with patients/patients talking with doctors: improving communication in medical visits: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Epstein R, Street R Jr. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bevilacqua LA, Dulak D, Schofield E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of depression, pain, and fatigue in older- versus younger-adult cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2018;27(3):900–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frazzetto P, Vacante M, Malaguarnera M, et al. Depression in older breast cancer survivors. BMC Surgery. 2012/11/15 2012;12(1):S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. Jul 2013;14(8):721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niedzwiedz CL, Knifton L, Robb KA, Katikireddi SV, Smith DJ. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer. 2019/10/11 2019;19(1):943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Segal DL, June A, Payne M, Coolidge FL, Yochim B. Development and initial validation of a self-report assessment tool for anxiety among older adults: The Geriatric Anxiety Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010/10/01/ 2010;24(7):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kypriotakis G, Deimling GT, Piccinin AM, Hofer SM. Correlated and Coupled Trajectories of Cancer-Related Worries and Depressive Symptoms among Long-Term Cancer Survivors. Behav Med. 2016;42(2):82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gotay CC, Pagano IS. Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC): a newly proposed brief questionnaire. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2007;5:15–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trevino KM, Nelson CJ, Saracino RM, Korc-Grodzicki B, Sarraf S, Shahrokni A. Is screening for psychosocial risk factors associated with mental health care in older adults with cancer undergoing surgery? Cancer. February12020;126(3):602–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.