Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit the world hardly as of the beginning of 2020 and quickly spread worldwide from its first-reported point in early Dec. 2019. By mid-March 2021, the COVID-19 almost hit all countries worldwide, with about 122 and 2.7 million confirmed cases and deaths, respectively. As a strong measure to stop the infection spread and deaths, many countries have enforced quarantine and lockdown of many activities. The shutdown of these activities has resulted in large economic losses. However, it has been widely reported that these measures have resulted in improved air quality, more specifically in highly polluted areas characterized by massive population and industrial activities. The reduced levels of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and particulate matter emissions have been reported and confirmed worldwide in association with lockdown periods. On the other hand, ozone levels in ambient air have been found to increase, mainly in response to the reduced nitrogen emissions. In addition, improved water quality in natural water resources has been reported as well. Wastewater facilities have reported a higher level of organic load with persistent chemicals due to the increased use of sanitizers, disinfectants, and antibiotics. The solid waste generated due to the COVID-19 pandemic was found to increase both qualitatively and quantitatively. This work presents and summarizes the observed environmental effects of COVID-19 as reported in the literature for different countries worldwide. The work provides a distinct overview considering the effects imposed by COVID-19 on the air, water, wastewater, and solid waste as critical elements of the environment.

Keywords: COVID-19, Environment, Pollution, Carbon emissions, Air quality, Water resources, Wastewater, Solid waste

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The world health organization had set up an incident management support team (IMST) in Jan. 2020 to respond to the recently reported cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). The new diseases caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been given the name COVID-19 for Coronavirus diseases in 2019 as a contagious and vascular disease (Johns Hopkins University, 2020). Since then, the COVID-19 has spread across the world and gets people infected in almost all countries worldwide, with some countries with a high level of cases and deaths. As of mid-March 2020, the number of COVID-19 global confirmed cases is about 122 million, with about 2.7 million deaths (Johns Hopkins University, 2020; World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). The fast spread and high infection and death rate associated with COVID-19 have resulted in a severe countermeasure of locking-down many cities and countries with transportation and travel bans to reduce and control the COVID-19 spread.

The lockdown measures applied in many countries worldwide due to the COVID-19 have resulted in the shutdown of many industrial and commercial activities, in addition to the quarantine measures. Careful attention has been given to preserving the natural environment with a detailed study of the different environmental impacts posed by different industrial processes (Abdelkareem et al., 2020; Elsaid et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2020b; Rabaia et al., 2020; Sayed et al., 2021). Many reports have shown that although of the catastrophic situation due to the COVID-19, the natural environment has been benefited by reducing or shutting down many pollution sources, especially industrial and commercial activities, as well as cease in transportation operation. A wide range of reports has shown an improved air quality and reduction in key pollutants such as carbon oxides (COx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), and particulate matter (PM) emissions, hence their concentration in the atmosphere have been lowered (L. W. A. Chen et al., 2020; M. Wang et al., 2020; Wang and Su, 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020).

Air quality improvement has been related to the quarantine and lockdown measures by comparing the air quality in pre-lockdown, lockdown, relaxed lockdown, and post-lockdown periods. This has been observed in China (Y. Chen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Pei et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020a; Zhao et al., 2020), Brazil (Dantas et al., 2020; Júnior et al., 2019; Nakada and Urban, 2020), Egypt (Mostafa et al., 2021), India (Mahato et al., 2020; Mahato and Ghosh, 2020; Mor et al., 2021; Sarfraz et al., 2020), Italy (Bontempi, 2020; Fattorini and Regoli, 2020), Spain (Baldasano, 2020; Briz-Redón et al., 2021; Martorell-Marugán et al., 2021), the United States of America USA (L. W. A. Chen et al., 2020; Q. Liu et al., 2021; Zangari et al., 2020), and many other countries worldwide (Adams, 2020; Ghahremanloo et al., 2021; Griffith et al., 2020; Kanniah et al., 2020; Stratoulias and Nuthammachot, 2020).

Air quality improvement was the most benefited environmental aspect due to the COVID-19, mainly due to reduced fuel consumption in the shutdown transportation and industrial sectors. Fewer reports have discussed the improved water quality, mainly due to the shutdown of many industrial activities releasing wastewater in such water bodies (Barcelo, 2020; Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020; Selvam et al., 2020b). On the other hand, some reports have indicated that wastewater has been loaded with additional and some persistent organic load due to the excessive use of sanitizers, disinfectants, medication, and antibiotics (Barcelo, 2020; Espejo et al., 2020; Selvam et al., 2020a; Usman et al., 2020; Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020).

This work provides an overview of the different environmental effects of COVID-19 in a distinct approach, considering the different elements of the environment, i.e., air, water resources, wastewater, and solid waste. The work summarizes the literature results for the environmental effects worldwide regarding improved air quality, water resources quality, deteriorated wastewater quality, and massively increased solid waste. The work focusses on the changes due to the lockdown and quarantine measures enforced worldwide. Although several reports have addressed some of the observed effects, it was considering a single aspect such as air quality, wastewater, or solid waste in a single approach. However, in the current work, we aimed to provide an overview of all the effects imposed by the COVID-19 on the different elements of the environment.

2. Methods and materials

The methodology followed in this work is mainly to constructively summarize, discuss, and relate the different reports published on the impacts of the COVID-19, and its sequences of lockdown and or reduction in different human activities such as commercial, industrial, and transportation. The work mainly is looking into how such measures impacted the environment both positively and negatively as reported in the research articles which reported the different observations. The collected and summarized reports have been chosen to represent different countries around the world, to assess the global impact of COVID-19 on the environment. A wide range of works has been published reporting impacts of the COVID-19 on the environment due to the observed improvements in some environment elements, more specifically air and water. In this regard, the reports followed certain approaches to asses such improvements, which are to be discussed in this section.

2.1. Air quality and gaseous emissions

Air is very essential for life as it provides us with the oxygen required for the respiration process and mainly consists of about 79% nitrogen and 21% oxygen, in addition to some other minor constituents such as carbon dioxide at about 400 ppm (part per million) (US EPA, 2021). However, due to the different human industrial, commercial, and domestic activities, the natural cycles of many elements are not in balance (Abdelkareem et al., 2020; Elsaid et al., 2021). The high consumption of fossil fuels for energy and industrial activities has led to increased concentrations of COx, NOx, SOx, PM, and ununiform concentrations of ozone O3, hence unbalancing the natural cycle of these elements (Lenz and Cozzarini, 1999). Fig. 1 (a) below shows the global historical emissions of gases, which has been increasing from 35 to 49.4 GtCO2-equivalent over 1990–2016. Carbon emissions represent almost 92% of the global emissions with 71–75% for CO2 from 1990 to 2010, and dropping to 74% in 2016, while that of CH4 dropped from 21 to 17% over 1990–2016, leaving about 6–7 and 2–3% for N2O and other gases, respectively (International Energy Agency, 2020). According to the center for climate and energy solutions (C2ES), about 72, 11, and 6% of the global greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions are due to energy, agriculture, and industrial process with an equal percentage for land-use change and forestry (“Center for climate and energy solutions (C2ES),” 2020).

Fig. 1.

(a) Global greenhouse gaseous emissions, (b) CO2 emissions for different sectors.

2.1.1. Carbon emissions

Carbon emissions are considered the main air pollutants being emitted in huge amounts since the start of wide utilization of fossil fuel such as coal, which is mainly composed of carbon, and then oil and gas composed of a wide range of hydrocarbons. The major product of combustion for such fossil fuels is carbon dioxide CO2, and water H2O (for hydrocarbons of oil and gas), in addition to some carbon monoxide CO and volatile organic carbons (VOCs) such as methane due to incomplete combustion (Gaete-Morales et al., 2019; Zhou and Feng, 2017). Fig. 1(b) shows the CO2 emissions for different sectors, indicating that the significant contributions to these emissions are from power and heat generation at about 38–42%, transportation at 23–25%, industrial processes at 17–20%, and residential activities at 6–9% (International Energy Agency, 2020). Accordingly, substantial efforts have been given to capture such carbon emissions or to reduce them to mitigate the associated climate change impact (Abdelkareem et al., 2020; Wilberforce et al., 2021). Alternatively, some attention is given to developing high energy efficiency processes or utilizing waste energy such as waste heat as an energy source that has lower environmental impacts (Agathokleous et al., 2019; Elsaid et al, 2020c, 2020d, 2020c; Jouhara and Olabi, 2018).

2.1.2. Nitrogen oxides NOx emissions

Nitrogen oxides (N2O, NO, and NO2, described as NOx) emissions have been widely described as one of the most harmful GHGs emissions due to their high toxicity level and impacts on human health. The main source for NOx is from fuel combustion in transportation and power generation, which is then getting into the natural nitrogen cycle (Shcheklein and Dubinin, 2020; Stüeken et al., 2016). The NOx concentrations specifically have been widely studied due to their environmental impacts, such as acidic rains and the greenhouse effect, and their health effect, causing respiratory system and irritation problems (Pacheco et al., 2020). As shown in Fig. 1(a) , nitrogen oxides represent the third GHGs emission with about 6–7% of the global GHGs emissions.

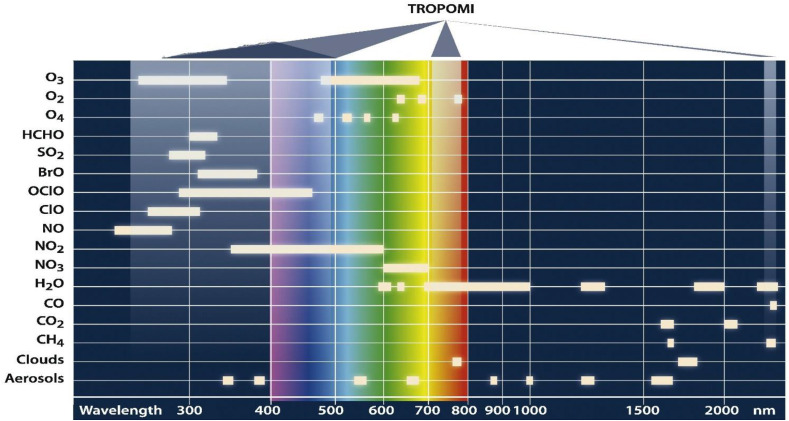

Fig. 2.

The components measure by the TROPOMI at the respective wavelengths (Veefkind et al., 2012).

2.1.3. Sulfur oxides SOx emissions

Sulfur oxides SOx is another important air pollutant associated with the burning of sulfur-containing fuels, which end up in the flue gas or exhaust into the atmosphere, and mainly in the form of sulfur dioxide SO2 at an average concentration of 10 mg/m3 as well as sulfur trioxide SO3 (Xu et al., 2017). Sulfur emissions have a very harmful effect on the environment causing severe corrosion to assets and several health and respiratory system problems. Accordingly, some efforts have been devoted to producing ultra low-sulfur or sulfur-free fuels, with strict environmental regulations for sulfur content in fuels (Antturi et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018).

2.1.4. Particulate matter PM emissions

Particulate matter (PM) is one of the main air pollutants and represent suspended particles of a certain size that are suspended in air, with fuel combustions, especially solid fuels such as coal and coke, as the main source for PM. Two types of PM are usually reported as air quality criteria or as air pollution indicators, PM2.5 and PM10 representing fine particles of diameter less than or equal to 2.5 and 10 μm, respectively (Yao et al., 2020b; Zoran et al., 2020). PM has a significant health impact due to the sensitivity of the human respiratory system to such fine, which can result in severe health problems.

2.1.5. Monitoring of air quality

Due to the emissions of such a wide range of pollutants into the atmosphere, it became very essential to monitor and measure the concentration of such pollutants and relating their evolution to different activities to help reducing their effects. Two major approaches are usually followed to monitor the air quality and different pollutants in the air. The first is to measure the concentration of different constituents in the air by sampling the air and analyze it in the lab according to the different analytical techniques (Higson, 2004; Trimm, 2011). Alternatively, online measurement techniques have evolved recently to provide continuous monitoring features, where the air is sampled and analyzed instantly in onsite air quality monitoring station (Cui et al., 2019; Marć et al., 2015; Whitehill et al., 2020). The results obtained from these techniques are very local and correspond to the sampling site, hence site location, time of sampling, and weather conditions play a significant role and have a substantial effect on the results obtained. The environmental authorities in many countries worldwide have worked to spread a large number of air quality monitoring stations in many urban and rural areas, industrial areas, to assess the air quality at the location of interest, and to make sure that the concentration of different pollutants does not exceed the permissible limits set by such entities (US EPA, 2021).

The second approach has evolved recently with the developments in the satellite industry, hence being able to put satellites in the Earth's orbit that can monitor the air quality across the globe, with a measurement that covers a wide area, up to covering whole countries (Ingmann et al., 2012). One of the very known and widely used satellites is the Sentinel-5 Precursor (Sentinel-5P), which is an Earth observation satellite developed by the European Space Agency ESA, which has the TROPOspehiric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) which is simply an ultraviolet UV, visible VIS, and infrared IR spectrometer, as shown in Fig. 2 (Butz et al., 2012; Veefkind et al., 2012). The wavelength is used for quantifying the different air quality parameters. The data obtained from the TROPOMI has been validated over a wide range of field air quality measurements from air quality stations worldwide proving its orbital and on-board measurement (Ludewig et al., 2020; Tilstra et al., 2020; Veefkind et al., 2012). The TROPOMI has been used effectively to monitor a wide range of air quality parameters including the different oxides of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, as well as particulate matter and ozone (Adame et al., 2020; Shikwambana et al., 2020; S. Wu et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). Usually, particulate matter is reflected by the Aerosol Optical Density AOD or tropospheric column density as an indirect measure of PM concentration. The main advantage of using the TROPOMI is that the data presented is over a wide area, and not that very local as in the case of the air quality stations. However, it worth noting that the TROPOMI is reporting the concentration of different constituents as molecules per unit area, i.e., as molecules intensity, in comparison to the traditional measurement techniques as those in the first approach, which report it in concentration units, mass or moles per unit volume.

2.2. Water and wastewater quality

The quality of water and wastewater is usually monitored by collecting samples from specific locations along the water stream or at the wastewater discharge point and different locations from the discharge point. Some quality parameters can be monitored online over the hour such as pH, electrical conductivity as a measure of the total dissolved solids as well as turbidity. However to provide more accurate results, samples have to be analyzed in certified labs and according to specific standard methods for the quantification of different parameters such as the “Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater” developed by the American Public Health Association APHA, the American Water Works Association AWWA; and the Water Environment Federation WEF (APHA, 2018).

3. Results and discussion

In this section, we discuss and analyze the different studies that have reported the impacts of COVID-19 on the environment. Most of the reports that have been published and studied were related to improved air quality due to the cease of many commercial and industrial activities. In addition, the lockdown along with movement and travel pans has resulted in a substantial reduction in fuel consumption in the transportation sector, hence reduced many pollution sources. The detailed improvements in air and water quality, as well as the impacts on wastewater and solid waste due to the COVID-19 pandemic, are discussed in detail in the following sections.

3.1. Improved air quality

One of the significant environmental effects of COVID-19 is the clearly observed improvement of air quality in regions undergoing quarantine and lockdown measures (Lal et al., 2020; F. Liu et al., 2021; Menut et al., 2020). The improved air quality was a direct result of the elimination or reduction of substantial pollution sources such as industrial activities and transportation means (Mahato and Ghosh, 2020; Menut et al., 2020; Rojas et al., 2020). In large cities with a multi-million population such as Madrid and Barcelona, Spain, traffic has been identified as the primary source of air pollution contributing 59–65, 67, 87-87% of the NOx, CO, and PM emissions, respectively, seconded by the airport with 18, 14, and 6.2–7.5% of the NOx, CO, and PM emissions (Guevara et al., 2013). The major categories that have been affected by the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic are carbon emissions of CO2, CO, and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrogen emissions of different nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur emissions of sulfur oxides (SOx), particulate matter (PM), ozone O3, and some other minor pollutants of heavy metals such as mercury. The results obtained from different air pollution monitoring station have been reported for many countries worldwide, which all shows the significant improvement in air quality. In addition, extensive modeling and simulation efforts have been made to describe the improvement in air quality in response to the quarantine and lockdown measures associated with the COVID-19 at different restriction levels (Meng et al., 2020; Tadano et al., 2021). Meanwhile, a reverse effect of the air quality on the evaluation of the number of COVID-19 cases was observed as well. Zhang et al. have correlated the air pollution to the confirmed COVID-19 daily new cases over 235 Chinese cities, which showed a strong association with PM2.5 (lag0-15), PM10 (lag0-15), and NO2 (lag0-20) at 7%, 6%, and 19%, respectively (Zhang et al., 2021). Similar results were observed for the UK as well, with PM2.5 was associated with a 12% increase in the daily new COVID-19 confirmed cases (Travaglio et al., 2021). The association of confirmed COVID-19 cases has been confirmed as well for indoor air quality, which is also associated with outdoor air quality (Saha and Chouhan, 2020). In this section, a qualitative and quantitative change of these different categories is thoroughly discussed.

3.1.1. Reduced carbon emissions

The emission of carbon compounds such as CO2, CO, and other VOCs are the most substantial emissions to ambient air from natural and anthropogenic activities. Natural activities such as volcanic eruptions and wildfire result in significant, but erratic, amounts of carbon emissions. While different anthropogenic activities result in a massive and steady amount of carbon emissions. Due to the COVID-19, many of the above-mentioned sources for gaseous emissions have been shut down, more specifically in transportation and industrial sections due to the quarantine measures. This, in return, has resulted in a significant reduction in the amount of gases emitted. Fig. 3 shows the tropospheric column density of CO and HCHO for the East Asia region from the TROPOMI of the Sentinel-5P satellite (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021). The image shows a distinct reduction in the intensity of these air pollutants in Feb. 2020 relative to Feb. 2019, which can be attributed to the COVID-19 lockdown. The figure shows a clear decrease in the color intensity and the absence of fade of the hot spots where the concentration of such pollutants is very high over East Asia, and more specifically over East and Southeast China.

Fig. 3.

Map of East Asia, showing the tropospheric column density of carbon monoxide (CO) and formaldehyde (HCHO) averaged in February 2019 and February 2020 (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021).

Table 1 below demonstrates some of the reported observations for the reduced carbon emissions in many countries due to COVID-19 lockdown, which has resulted in a significant reduction in the concentration of different carbon compounds. In most of the studies, CO was considered as a measure of total carbon emissions rather than CO2 due to its high toxicity and strong association with total carbon emissions. CO concentration have shown a decrease of about 3.8–7.8% in China (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021; Wang and Su, 2020), 17.2% in India (Mor et al., 2021), and 6.4% in Seoul, South Korea (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021). CO2 has shown a decrease in the concentration of about 25 and 30% in rural and urban areas of Spain, respectively (Martorell-Marugán et al., 2021), 51% in California, USA (Q. Liu et al., 2021). Formaldehyde, as one of the major VOCs, has shown a reduction of about 10–13, 22.1, and 8.4 in China, Seoul S. Korea, and Tokyo-Japan, respectively (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021). Similarly, other VOCs such as benzene, toluene, and ethylbenzene have shown a reduction in concentrations up to 50.3%, 69.8, and 24.2%, respectively, while xylene has shown an increase up to 233% (Mor et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Summary for the observed reduction in carbon oxides and other organic matter due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

| COUNTRY | STUDY SCOPE (AREA AND PERIOD IN, 2020) | KEY FINDINGS | REF. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAZIL | São Paulo Feb. 25 – Mar. 23 |

CO: A reduction of about 36.1–64.8% relative to the 5-years average, and 15.8–29.8% relative to pre-lockdown. | Nakada and Urban (2020) |

| Rio de Janeiro Mar. 2 – April 16 |

CO: reduction ranges from 15.2% in 1st week tup to 48.5%. | Dantas et al. (2020) | |

| Nonmethane hydrocarbons (NMHC): A reduction of about 25 ppmC during the partial lockdown, and 12.5 ppmC during relaxed lockdown relative to pre-lockdown | Siciliano et al. (2020) | ||

| CHINA | Countrywide Jan. 1 - Feb. 25. |

CO: average concentration is 1.5 mg CO/m3 (−6.2% year-on-year) | Wang and Su (2020) |

| INDIA | Countrywide Feb. 15 – May 3 Lockdown: Mr. 25 –May 3 |

CO: Central India: -43.7% to 489.0 ± 206.3 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 868.5 ± 396.20 μg/m3 (2017–2019), Indo Gangetic Plain: -36.3% to 543.7 ± 237.8 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 854.0 ± 296.1 μg/m3 (2017–2019) North-west: -10.6% to 581.5 ± 173.5 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 650.5 ± 179.4 μg/m3 (2017–2019) South: -18.8% to 565.2 ± 198.8 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 695.7 ± 183.0 μg/m3 (2017–2019) |

(V. Singh et al., 2020) |

| Chandigarh Mar. 25 –May 17. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 – Apr. 16. 2nd Phase: Apr. 17 –May 3. 3rd Phase: 4th – 17th May. |

CO: Pre-lockdown 0.55 mg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 0.46 mg/m3 (−17.4%), 2nd phase 0.52 mg/m3 (−6.1%), 3rd phase 0.57 mg/m3 (+2.8%). Benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, and xylene (BTEX): Benzene: Pre-lockdown 4.4 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 3.2 μg/m3 (−26.8%), 2nd phase 3.0 μg/m3 (−31.2%), 3rd phase 2.2 μg/m3 (−50.3%). Toluene: Pre-lockdown 1.4 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 0.4 μg/m3 (−69.8%), 2nd phase 0.7 μg/m3 (−51.1%), 3rd phase 1.0 μg/m3 (−24.6%). Ethyl benzene: Pre-lockdown 3.2 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 3.1 μg/m3 (−3.5%), 2nd phase 2.9 μg/m3 (−11.0%), 3rd phase 2.4 μg/m3 (−24.2%). o-Xylene: Pre-lockdown 1.0 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 1.1 μg/m3 (+10.0%), 2nd phase 1.1 μg/m3 (+10.1%), 3rd phase 0.9 μg/m3 (−10.0%). m, p-Xylene: Pre-lockdown 0.6 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 0.8 μg/m3 (+33.3%), 2nd phase 0.9 μg/m3 (+50%), 3rd phase 2.0 μg/m3 (+233.3%). |

Mor et al. (2021) | |

| Darjeeling 1st - 30th April |

Total carbonous aerosol (TCA) 8.6–41 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 7.4–22.2 μg/m3 in April 2019. Organic carbon (OC) 4.8–22.4 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 3.8–12.1 μg/m3 in April 2019. Elemental carbon (EC) 0.9–4.9 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 0.9–3.7 μg/m3 in April 2019. OC/EC ratio 4.2 ± 1.1 (2.8–7.5) in 2020 relative to 5.7 ± 0.9 (3.6–7.2) in April 2019 (−35%). Secondary organic carbon (SOC) 7.6 ± 3.5 (2.6–13.3) μg/m3 relative to 3.8 ± 1.4 (1.7–7.5) μg/m3 in April 2019 (−50%). |

Chatterjee et al. (2021) | |

| SPAIN | Countrywide Jan. 1 – Jun. 20 Strict lockdown: Mar. 14 –May 3. Relaxed lockdown: May 5 – Jun. 20. |

Urban areas Carbon monoxide CO: ➢Prior to lockdown 0.33 ± 0.04 mg/m3 ➢Strict lockdown 0.26 ± 0.02 mg/m3 (−22.9%) ➢Relaxed lockdown 0.23 ± 0.01 mg/m3 (−30%) Rural areas Carbon monoxide CO: ➢Prior to lockdown 0.31 ± 0.02 mg/m3 ➢Strict lockdown 0.28 ± 0.04 mg/m3 (−9.8%) ➢Relaxed lockdown 0.23 ± 0.01 mg/m3 (−25.2%) |

Martorell-Marugán et al. (2021) |

| Barcelona March 14–30 |

Black carbon: Average concentration of 0.6 μg/m3 relative to 1.1 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (−45.4%) | Tobías et al. (2020) | |

| USA | California, Mar. 19 –May 7. | -49% relative to pre-lockdown 2020, and -51% relative to the normalized 2015–2019 concentrations. | (Q. Liu et al., 2021) |

| EAST ASIA | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) & Wuhan, China; Seoul metropolitan area (SMA), S. Korea; Tokyo metropolitan area (TMA), Japan. 1st – 29th Feb. |

Formaldehyde HCHO BTH: 6.5E15 ± 2.4E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 7.4E15 ± 3.7E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−13%). Wuhan: 6.5E15 ± 1.5E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 7.3E16 ± 3.7E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−10.4%) SMA: 4.5E15 ± 1.4E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 5.8E16 ± 1.3E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−22.1%). TMA: 3.5E15 ± 9.7E14 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 3.9E15 ± 1.2E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−8.4%) Carbon monoxide CO: BTH: 2.98E18 ± 6.43E17 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 3.23E18 ± 8.10E17 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−7.8%). Wuhan: 3.38E18 ± 1.87E17 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 3.51E18 ± 3.74E17 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−3.8%) SMA: 2.77E18 ± 9.1E16 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 2.95E18 ± 9.1E165 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−6.4%). TMA: 2.48E18 ± 3.35E16 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 2.51E18 ± 7.54E16 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−1.2%) |

Ghahremanloo et al. (2021) |

3.1.2. Reduced nitrogen emissions

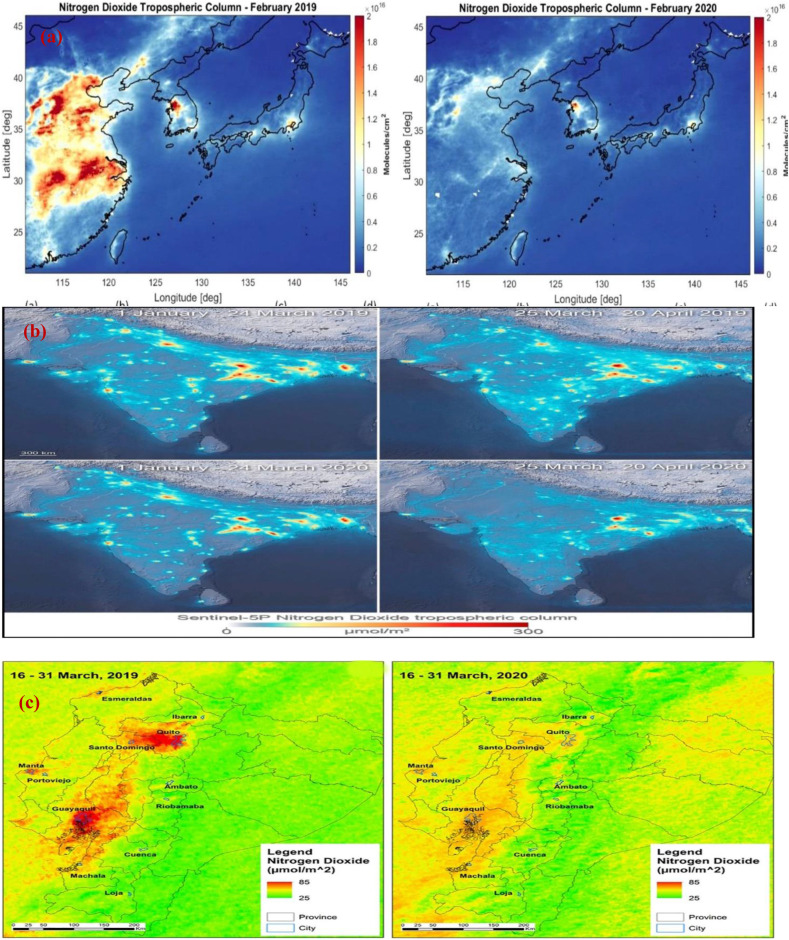

Nitrogen emissions being mainly associated with the combustion of fossil fuels are expected to drop significantly due to the cease in transportation and travel activities due to lockdown and quarantine measures. Table 2 presents demonstrative results for the improved air quality in terms of reduced NOx concentration from different countries around the world. The reported results have shown a substantial concentration reduction of about 25% in China (Wang and Su, 2020), while in Ghaziabad, India, a reduction of 48.7% in NO2 concentration (Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020). A more detailed study for Chandigarh, India, has shown a reduction of up to 73.6, 23, 46.2, and 52.8% for NO, NO2, NOx, and NH3, respectively (Mor et al., 2021), while in Darjeeling, India, a reduction up to −84 and −58% for NO and NO2 respectively (Chatterjee et al., 2021). Fig. 4 shows the satellite images obtained by TROPOMI for East Asia, India, and Ecuador (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021; Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020; Pacheco et al., 2020). The results obtained confirm the significant reduction in atmospheric NO2 intensity due to the COVID-19 lockdown. The intensity of NO2 over East and Southeast China has been significantly reduced as indicated by a color change to approach that of background, with similar results for East India and Ecuador as well. In addition, the areas with very high color intensity have completely faded.

Table 2.

Summary of the observed reduction in nitrogen oxides NOx due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

| COUNTRY | STUDY SCOPE (AREA AND PERIOD IN, 2020) | KEY FINDINGS | REF. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAZIL | São Paulo Feb. 25 - Mar. 23 |

NO: A reduction of about 48.6–77.3% relative to 5-years average, and 18.8–40.4% relative to pre-lockdown. NO2: A reduction of about 30.1–54.3% relative to 5-years average and 13.6–40.4% relative to pre-lockdown. NOx: A reduction of about 40.7–65.4% relative to 5-years average and 16.1–31.7% relative to pre-lockdown. |

Nakada and Urban (2020) |

| Rio de Janeiro Mar. 2 - Apr. 16 |

NO2: reduction ranges from 1.8% in 1st week to up to 53.9%. | Dantas et al. (2020) | |

| NOx: A reduction of about 24.4–46.1 μg/m3 during the partial lockdown and 9.2–13.8 μg/m3 during relaxed lockdown relative to pre-lockdown | Siciliano et al. (2020) | ||

| CHINA | Countrywide, Jan. 1 - Feb. 25 | NO2: Average concentration is 24 μg/m3(-25% year-on-year) | Wang and Su (2020) |

| ECUADOR | Countrywide (12 cities) Mar. 16–31 |

NO2: Average concentration of 37.72 ± 1.63 μmol/m2 (range of 31.26 ± 0.79 to 50.97 ± 6.41 μmol/m2) in 2020, relative to 43.37 ± 2.06 μmol/m2 ((range of 33.81 ± 0.56 to 66.51 ± 7.64 μmol/m2) with an average reduction of 13.03% (range of 5.49–23.36%) | Pacheco et al. (2020) |

| INDIA | Countrywide Feb. 15 – May 3 Lockdown: Mr. 25 –May 3 |

NO2: Central India: 39.2% reduction to 13.1 ± 4.2 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 21.5 ± 11.1 μg/m3 (2017–2019), Indo Gangetic Plain: 55% reduction to 14.9 ± 5.0 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 33.2 ± 16.1 μg/m3 (2017–2019) North-west: 57.4% reduction to 13.5 ± 5.8 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 31.6 ± 14.6 μg/m3 (2017–2019) South: 50.4% reduction to 13.5 ± 9.9 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 27.3 ± 15.3 μg/m3 (2017–2019) |

(V. Singh et al., 2020) |

| Ghaziabad, Jan. 10 - Apr. 19. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 - Apr. 14 2nd Phase: Apr. 15 - May 3. |

NO2: −48.7% as compared to pre-lockdown (to January 14, 2020), and −34.4% as compared to 2019 (i.e., April 14, 2019). | Lokhandwala and Gautam (2020) | |

| Chandigarh, Mar. 25 - May 17. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 - Apr. 14 2nd Phase: Apr. 15 -May 3. 3rd Phase: 4–17 May. |

NO: Pre-lockdown 7.2 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 1.9 μg/m3, 2nd phase 2.4 μg/m3, 3rd phase 2.3 μg/m3. NO2: Pre-lockdown 13.9 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase10.7 μg/m3, 2nd phase 11.6 μg/m3, 3rd phase 13.0 μg/m3. NOX: Pre-lockdown 13.0 ppb, Lockdown: 1st phase 7.0 ppb, 2nd phase 8.0 ppb, 3rd phase 8.6 ppb. NH3: Pre-lockdown 68.0 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 38.3 μg/m3, 2nd phase 32.1 μg/m3, 3rd phase 32.5 μg/m3. |

Mor et al. (2021) | |

| Darjeeling, Apr. 1 - 30 | Average concentration during lockdown is 0.8 ± 0.15 ppb NO (−84%), and 3.9 ± 0.4 ppb NO2 (−58%) relative to 4.9 ± 0.6 ppb NO, and 9.2 ± 0.8 ppb NO2 in April 2019. | Chatterjee et al. (2021) | |

| IRAQ | Baghdad, Jan. 2 -Jul. 24. 1st Partial and total lockdown Mar. 1 - Jun. 13. 2nd Partial lockdown Jun. 14 - Jul. 24 |

NO2: Pre-lockdown 91 μg/m3, 1st partial and total lockdown: 84 μg/m3 (−7.7%), 2nd partial lockdown 73 μg/m3 (−19.8%). | Hashim et al. (2021) |

| ITALY | Milan metropolitan area Jan. 1 - Apr. 30 |

NO2: Average concentration of 28.97 ± 9.66 μg/m3 (range of 6–57 μg/m3), a reduction of about 64.7% based on a year-to-year average. | Zoran et al. (2020) |

| SPAIN | Barcelona metropolitan and Madrid Mar. 14–29. |

NO2: A reduction of about 59 and 56% for Barcelona and Madrid, respectively, as compared to 2019. | Baldasano (2020) |

| Countrywide, Jan. 1 - Jun. 20 Strict lockdown: Mar. 14 -May 3. Relaxed lockdown: May 5 - Jun. 20. |

|

Martorell-Marugán et al. (2021) | |

| Barcelona Mar. 14 - 30 |

NO2: Average concentration of 15.9 μg/m3 relative to 30.0 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (−47%) in Urban background. Average concentration of 20.6 μg/m3 relative to 42.4 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (−51.4%) in Traffic area. |

Tobías et al. (2020) | |

| UK | Country wide, Jan. 1 - June 30 Locking-down: Mar. 10 - Apr. 10. Locked-down: Apr. 11 - Jun. 30. |

NO: change in concentration of −9.7 μg/m3 (−50%), NO2 -7.6 μg/m3 (−32%), NOx −17.1 μg/m3 (−38%) This suggests that by the end of the studied period (Jun. 30, 2020), a significant proportion, provisionally estimated at ca. 50–70%, of the air quality benefits, observed while locking down had already been offset by the return of vehicles to the roads. |

Ropkins and Tate (2021) |

| Countrywide Mar. 30 – May 3 |

NO2: 14.1 μg/m (range of 5.7–17.5 μg/m), an average reduction of about 38.3% (range of 14.8–50.5%) relative to the 2017–2019 average of the same period. NOx: 21.5 μg/m (range of 10.1–30.0 μg/m), an average reduction of about 38.0% (range of 18.6–57.3%) relative to the 2017–2019 average of the same period. |

Jephcote et al. (2020) | |

| USA | California, Lockdown: Mar. 19 - May 7. | NO2: −38% relative to pre-lockdown 2020, and -46% relative to the normalized 2015–2019 concentrations. | (Q. Liu et al., 2021) |

| EAST ASIA | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) & Wuhan, China; Seoul metropolitan area (SMA), S. Korea; Tokyo metropolitan area (TMA), Japan. Feb. 1 - 29 |

NO2: BTH: 4.3E15 ± 2.2E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 9.3E15 ± 6E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−53.7%). Wuhan: 2.5E15 ± 7.2E14 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 1.5E16 ± 3.4E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−82.5%) SMA: 1E16 ± 3.7E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 1.6E16 ±5E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−33.1%). TMA: 7.9E15 ± 2.4E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 9.8E15 ± 2.1E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−19.2%) |

Ghahremanloo et al. (2021) |

| EUROPE | 10 European countries Mar. 15 - April 30 |

NO2: A reduction relative to the same period in 2019 of Austria: Urban 34.4 ± 5.9%, Rural 27.6 ± 9.2%. Belgium: Urban 36.3 ± 7.2%, Rural 35.7 ± 10.3%. Czech Republic: Urban 8.8 ± 6.0%, Rural 22.8 ± 17.9%. Germany: Urban 25.9 ± 7.6%, Rural 26.0 ± 13.0%. Spain: Urban 50.0 ± 11.9%, Rural 39.4 ± 26.6%. France: Urban 46.9 ± 9.8%, Rural 42.3 ± 17.0%. United Kingdom: Urban 35.0 ± 11.9%, Rural 31.7 ± 11.0%. Italy: Urban 48.4 ± 13.7%, Rural 32.2 ± 26.3%. Netherlands: Urban 27.0 ± 4.5%, Rural 22.3 ± 11.1%. Poland: Urban 23.7 ± 12.9%, Rural 18.7 ± 18.2%. |

Ordóñez et al. (2020) |

| 27 European countries Mar. 1–31. |

NO2: A reduction relative to the same period in 2019 of Austria: Urban 37.1%, Rural 37.8%. Belgium: Urban 34.8%, Rural 33.6%. Bosnia Hzgv: Urban 43.2%, Rural 16.2%. Bulgaria: Urban 38.5%, Rural 33.4%. Croatia: Urban 37.5%, Rural 23.1%. Czech Republic: Urban 18.1%, Rural 21.6%. Denmark: Urban 19.8%, Rural 13.6%. France: Urban 43.2%, Rural 43.8%. Germany: Urban 29.5%, Rural 25.4%. Greece: Urban 44.6%, Rural 27.2%. Hungary: Urban 22.6%, Rural 24.8%. Italy: Urban 44.0%, Rural 27.2%. Ireland: Urban 37.3%, Rural 29.5%. Lithuania: Urban 26.5%, Rural 24.5%. Netherlands: Urban 22.6%, Rural 16.3%. Norway: Urban 24.0%, Rural 20.4%. Poland: Urban 27.0%, Rural 25.6%. Portugal: Urban 57.8%, Rural 53.6%. Romania: Urban 28.6%, Rural 29.4%. Russia: Urban 25.4%, Rural 17.6%. Serbia: Urban 26.7%, Rural 19.3%. Slovakia: Urban 23.8%, Rural 23.8%. Slovenia: Urban 40.7%, Rural 29.1%. Spain: Urban 48.8%, Rural 46.8%. Sweden: Urban 13.0%, Rural 9.7%. Switzerland: Urban 31.4%, Rural 33.0%. United Kingdom: Urban 38.1%, Rural 29.8%. |

Menut et al. (2020) |

Fig. 4.

Map of (a) East Asia (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021), (b) India (Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020), and (c) Ecuador (Pacheco et al., 2020) showing the tropospheric column density of NO2.

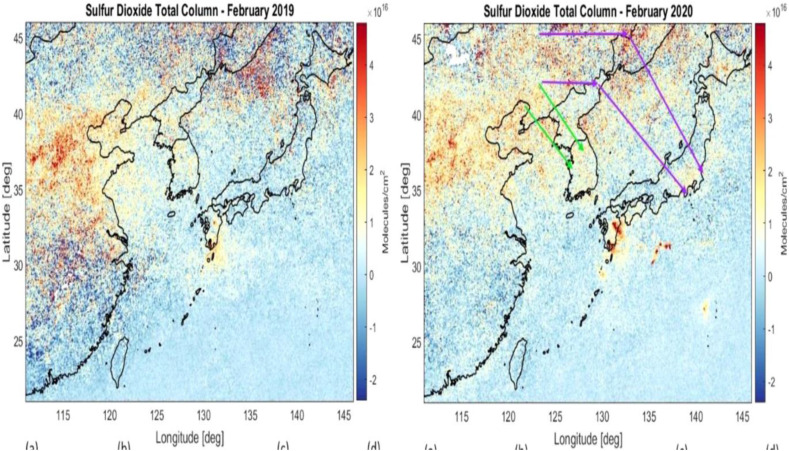

3.1.3. Reduced sulfur emissions

Similar to carbon and NOx, SOx emissions are expected to be reduced as well, resulting in significant air quality improvement due to the shutdown of several industrial activities and the cease of transportation due to the quarantine and lockdown of COVID-19 (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021; Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020; Martorell-Marugán et al., 2021). Table 3 below demonstrates some of the reported results for the reduction in SOx in different countries due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Only an increase for SOx concentration was reported for Seoul, South Korea, and Tokyo, Japan of about 38 and 243%, respectively (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021). While reductions of about 21.4% for China countrywide, 71.5% for Wuhan, China, 14.3–16.3% for India, and 7.3–20% for Spain. Fig. 5 shows the satellite images obtained by TROPOM for East Asia, indicating the significant reduction in atmospheric SO2 concentration due to the COVID-19 lockdown as indicated by the reduction in color intensity and absence of extreme color spots.

Table 3.

Summary of the observed reduction in sulfur oxides SOx due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

| COUNTRY | STUDY SCOPE (AREA AND PERIOD IN, 2020) | KEY FINDINGS | REF. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAZIL | São Paulo Feb. 25 – Mar. 23 |

SO2: A reduction of about 18.1–32.7% relative to 5-years average, and an increase of 8–16.2% relative to pre-lockdown. | Nakada and Urban (2020) |

| CHINA | Country wide, Jan. 1st – Feb. 25th | SO2: Average concentration is 11 μg/m3(-21.4% year-on-year) | Wang and Su (2020) |

| INDIA | Countrywide Feb. 15 – May 3 Lockdown: Mr. 25 –May 3 |

SO2: Central India: 4.1% increase to 11.5 ± 8.0 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 11.1 ± 6.6 μg/m3 (2017–2019), Indo Gangetic Plain: 19.6% reduction to 11.0 ± 5.2 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 13.6 ± 7.4 μg/m3 (2017–2019) North-west: 6.8% reduction to 10.1 ± 5.5 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 10.9 ± 3.9 μg/m3 (2017–2019) South: 16.5% reduction to 4.9 ± 1.9 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 5.9 ± 2.7 μg/m3 (2017–2019) |

(V. Singh et al., 2020) |

| Ghaziabad, Jan. 10 – Apr. 19. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 – Apr. 14 2nd Phase: Apr. 15 –May 3. |

SO2: −14.3% as compared to pre-lockdown (to January 14, 2020), and −16.3% as compared to 2019 (i.e., April 14, 2019). | Lokhandwala and Gautam (2020) | |

| Chandigarh, Mar. 25 – May 17. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 – Apr. 16 2nd Phase: Apr. 17 –May 3. 3rd Phase: 4th – 17th May. |

SO2: Pre-lockdown 9.9 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 10.0 μg/m3, 2nd phase 11.4 μg/m3, 3rd phase 11.8 μg/m3. | Mor et al. (2021) | |

| SPAIN | Countrywide, Jan. 1 – Jun. 20 Strict lockdown: Mar. 14 –May 3. Relaxed lockdown: May 5 – Jun. 20. |

Urban areas:

|

Martorell-Marugán et al. (2021) |

| Barcelona March 14–30 |

SO2: Avarage concentration of 1.0 μg/m3 relative to 1.2 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (−19.4%) in Urban background. | Tobías et al. (2020) | |

| EAST ASIA | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) & Wuhan, China; Seoul metropolitan area (SMA), S. Korea; Tokyo metropolitan area (TMA), Japan. 1st – 29th Feb. |

SO2: BTH: 1.3E16 ± 1.1E16 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 1.3E16 ± 1.4E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−0.01%). Wuhan: 1.1E15 ± 8.1E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 3.9E15 ± 2.3E16 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (−71.5%) SMA: 1.1E16 ± 8.4E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 8.2E15 ± 9.8E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (+38.1%). TMA: 9.4E15 ±8E15 molecule/cm2 in 2020 relative to 2.7E15 ± 8.1E15 molecule/cm2 in 2019 (+243.4%) |

Ghahremanloo et al. (2021) |

Fig. 5.

Map of East Asia showing the tropospheric column density of SO2 averaged in February 2019 and February 2020 (Ghahremanloo et al., 2021).

3.1.4. High ozone levels in ambient air

Ozone O3 is an essential component of the atmospheric air at an approximate concentration of about 8 ppm (Tobías et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine period, it was noticed that O3 concentration had increased relatively. The increased O3 concentration can be related to the reduced NOx concentrations according to the below set of reactions (1)–(3), which represent the equilibrium reactions network for nitrogen oxides NO, NO2, and oxygen species O, O2, and O3 (Hashim et al., 2021; Martorell-Marugán et al., 2021). The reactions show that O3 concentration is in an equilibrium network with O2, NO, and NO2 in which any change in concentration of one species will result in a change in all other species in the network.

| NO2 + hʋ (<420 nm) ↔ NO + O | (1) |

| O + O2 ↔ O3 | (2) |

| NO + O3 ↔ NO2 + O2 | (3) |

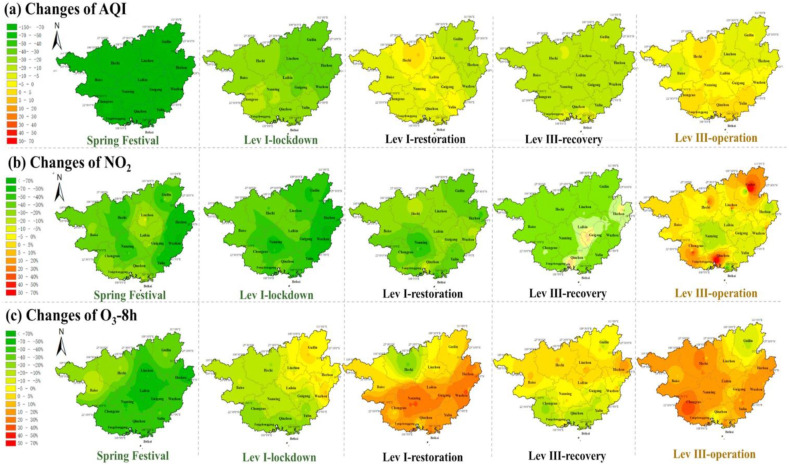

Table 4 below demonstrates the observed increase in O3 concentrations in many countries during the COVID-19 lockdown (Fu et al., 2020). An increase of up to 183% in Chandigarh, India, 525% in Baghdad, Iraq, 56.3% in Spain, 14% in California, USA, and 49.8% in Wuhan, China. Fig. 6 below shows the relative changes in overall air quality index (AQI) in relation to changes in NO2 and O3 concentration as demonstrated in Guangxi region, China in 2020 compared to the relative average over the same time period in 2016–2019 (Fu et al., 2020). The figure shows the interaction between NO2 and O3 concentration as expressed by the above reversible reactions in complex interaction. The figure shows the increase of O3 concentration during the lockdown period as compared to the pre-lockdown time.

Table 4.

Summary of the observed increase in ozone O3 due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

| COUNTRY | STUDY SCOPE (AREA AND PERIOD IN, 2020) | KEY FINDINGS | REF. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAZIL | São Paulo Feb. 25 – Mar. 23 |

An increase of about 30.3–31.5% relative to 5-years average, and an increase of 10.8–13.4% relative to pre-lockdown. | Nakada and Urban (2020) |

| Rio de Janeiro Mar. 2 – April 16 |

An increase ranges from 33.5% in 1st week to up to 67.1%. | Dantas et al. (2020) | |

| Increase of about 6.3–12.9 μg/m3 during the partial lockdown and 0.1–1.8 μg/m3 during relaxed lockdown relative to pre-lockdown | Siciliano et al. (2020) | ||

| CHINA | Countrywide, Jan. 1 – Feb. 25 | The average concentration is 105 μg O3/m3 (No change). | Wang and Su (2020) |

| INDIA | Countrywide Feb. 15 – May 3 Lockdown: Mr. 25 –May 3 |

Central India: 18.3% reduction to 44.0 ± 22.7 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 53.9 ± 25.2 μg/m3 (2017–2019), Indo Gangetic Plain: 1.8% increase to 41.3 ± 20.4 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 40.6 ± 17.8 μg/m3 (2017–2019) North-west: 7.5% reduction to 39.9 ± 15.8 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 43.1 ± 18.2 μg/m3 (2017–2019) South: 28.2% reduction to 31.0 ± 12.0 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 43.1 ± 16.6 μg/m3 (2017–2019) |

(V. Singh et al., 2020) |

| Chandigarh, Mar. 25 –May 17. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 – Apr. 16 2nd Phase: Apr. 17 –May 3. 3rd Phase: 4th – 17th May. |

Pre-lockdown 13.8 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 19.2 μg/m3 (+39.1%), 2nd phase 26.5 μg/m3 (+92%), 3rd phase 31.7 μg/m3 (+183.3%). | Mor et al. (2021) | |

| Darjeeling, 1st −30th April | The average concentration during lockdown is 41 ppb (+32%) relative to 31 ppb in April 2019. | Chatterjee et al. (2021) | |

| IRAQ | Baghdad, Jan. 2 -Jul. 24. 1st Partial and total lockdown Mar. 1 – Jun. 13. 2nd Partial lockdown Jun. 14 – Jul. 24 |

Pre-lockdown 8 μg/m3, 1st partial and total lockdown: up to 26 μg/m3 (+225%), 2nd partial lockdown 50 μg/m3 (+525%). | Hashim et al. (2021) |

| ITALY | Milan metropolitan area Jan. 1 – April 30 |

Average concentration of 25.27 ± 15.27 μg/m3 (range of 2–56 μg/m3) increased about 225% based on year-to-year avarage. | Zoran et al. (2020) |

| SPAIN | Countrywide, Jan. 1 – Jun. 20 Strict lockdown: Mar. 14 –May 3. Relaxed lockdown: May 5 – Jun. 20. |

Urban areas: ➢Prior to lockdown 40.22 ± 10.97 μg O3/m3 ➢Strict lockdown 60.37 ± 6.87 μg O3/m3 (+50.1%) ➢Relaxed lockdown 62.88 ± 5.73 μg O3/m3 (+56.3%) Rural areas: ➢Prior to lockdown 58.86 ± 9.47 μg O3/m3 ➢Strict lockdown 68.02 ± 7.01 μg O3/m3 (+15.6%) ➢Relaxed lockdown 70.15 ± 7.55 μg O3/m3 (19.2%) |

Martorell-Marugán et al. (2021) |

| Barcelona March 14–30 |

NO2: Avarage concentration of 67.3 μg/m3 relative to 52.4 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (+28.5%) in Urban background. Avarage concentration of 65.9 μg/m3 relative to 41.8 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (+57.7%) in Traffic area. |

Tobías et al. (2020) | |

| UK | Countrywide, Jan. 1 – Jun. 30 Locking-down: Mar. 10 – Apr. 10. Locked-down: Apr. 11 – Jun. 30. |

7–7.4 μg/m3 (+17%), | Ropkins and Tate (2021) |

| Countrywide Mar. 30 – May 3 |

65.7 μg/m3 (range of 49.7–73.7 μg/m3), an average increase of about 9.3% (range of −13.5 – 22.4%) relative to the 2017–2019 average of the same time period. | Jephcote et al. (2020) | |

| USA | California, USA Mar. 19 –May 7. |

14% relative to pre-lockdown 2020, and -10% relative to the normalized 2015–2019 concentrations. | (Q. Liu et al., 2021) |

| EAST ASIA | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) & Wuhan, China; Seoul metropolitan area (SMA), S. Korea; Tokyo metropolitan area (TMA), Japan. 1st – 29th Feb. |

BTH: 55.3 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 47.3 μg/m3 in 2019 (+16.9%). Wuhan: 55.6 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 37.1 μg/m3 in 2019 (+49.8%). |

Ghahremanloo et al. (2021) |

| EUROPE | 10 countries (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Spain, France, United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, and Poland) Mar. 15 – April 30 |

A change relative to the same period in 2019 of: Austria: Urban 0.5 ± 5.6%, Rural −3.3 ± 4.3%. Belgium: Urban 8.7 ± 6.7%, Rural 3.2 ± 3.4%. Czech Republic: Urban −2.0 ± 5.3%, Rural −2.5 ± 2.7%. Germany: Urban 2.5 ± 4.1%, Rural −0.3 ± 3.6%. Spain: Urban −1.7 ± 11.6%, Rural −7.8 ± 7.3%. France: Urban 1.7 ± 6.8%, Rural −2.1 ± 5.0%. United Kingdom: Urban 4.7 ± 11.4%, Rural −1.2 ± 5.5%. Italy: Urban 1.9 ± 12.2%, Rural −2.2 ± 14.7%. Netherlands: Urban 3.8 ± 4.6%, Rural 3.4 ± 5.0%. Poland: Urban −3.5 ± 8.8%, Rural 1–7.2 ± 9.3%. |

Ordóñez et al. (2020) |

| 27 European countries Mar. 1–31. |

A change relative to the same period in 2019 of Austria: Urban +6.4%, Rural +0.64%. Belgium: Urban +17.6%, Rural +6.60%. Bosnia Hzgv: Urban −1.5%, Rural −2.17%. Bulgaria: Urban −2.1%, Rural −2.45%. Croatia: Urban −1.5%, Rural −1.65%. Czech Republic: Urban +1.2%, Rural +0.63%. Denmark: Urban +1.5%, Rural +0.27%. France: Urban +6.7%, Rural +0.72%. Germany: Urban +4.5%, Rural +0.73%. Greece: Urban +5.2%, Rural −2.37%. Hungary: Urban −0.7%, Rural −1.60%. Italy: Urban +5.8%, Rural −0.08%. Ireland: Urban −2.7%, Rural −2.34%. Lithuania: Urban +0.8%, Rural +0.04%. Netherlands: Urban +8.2%, Rural +5.41%. Norway: Urban +1.3%, Rural +0.07%. Poland: Urban +3.7%, Rural +0.65%. Portugal: Urban +8.1%, Rural −2.39%. Romania: Urban −1.6%, Rural −1.82%. Russia: Urban +1.6%, Rural +0.04%. Serbia: Urban −1.7%, Rural −2.37%. Slovakia: Urban −0.9%, Rural −1.38%. Slovenia: Urban +2.1%, Rural −1.52%. Spain: Urban +4.4%, Rural −2.04%. Sweden: Urban +0.7%, Rural +0.01%. Switzerland: Urban +1.8%, Rural +0.50%. United Kingdom: Urban +5.1%, Rural +1.06%. |

Menut et al. (2020) |

Fig. 6.

The relative changes in a) air quality index, b) NO2, c) O3 in Guangxi region, China over different lockdown and quarantine periods relative to the average of 2016–2019 of the same period (Fu et al., 2020).

3.1.5. Reduced particulate matter emissions

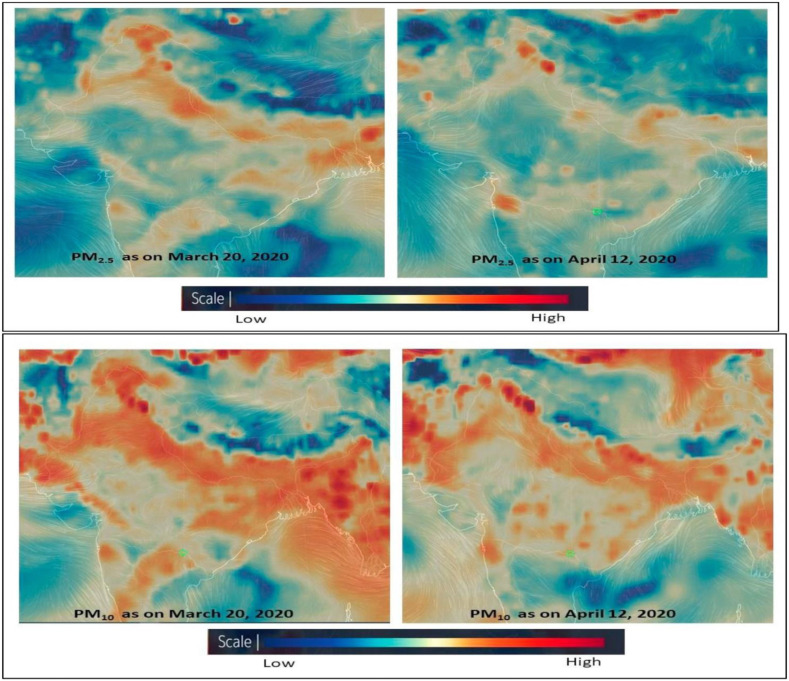

Particulate matter PM emissions are expected to follow the same pattern as other air pollutants of carbon, NOx and SOx being all produced by the same source of fossil fuel combustion. Fig. 7 confirms the drop in PM concentrations in air due to the COVID-19 lockdown in India, showing a significant reduction in different PM concentrations. The figure indicates as well a much reduction in PM2.5 relative to reductions in PM10. Table 5 below demonstrates some of the observed reductions in PM due to the COVID-19 lockdown. The report has shown a decrease in PM concentration up to 20.5% in China, up to 85.1% in Ghaziabad, India, 39.2% in Spain, and 31% in California, USA (for PM2.5). On the other hand, fewer reports have shown an increase in PM concentrations up to 17% in the United Kingdom UK and 21% in California, USA (for PM10). Similarly, reports for Baghdad, Iraq, have shown no significant change in PM concentrations.

Fig. 7.

Map of India showing the tropospheric column density of particulate matter PM 2.5 (Top), and PM10 (bottom) (Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020).

Table 5.

Summary of the observed increase in particulate matter PM due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

| COUNTRY | STUDY SCOPE (AREA AND PERIOD IN, 2020) | KEY FINDINGS | REF. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAZIL | São Paulo Feb. 25 – Mar. 23 |

PM2.5: A reduction of about 29.8% relative to the 5-years average and of 0.3% relative to pre-lockdown. PM10: A reduction of about 12.7-36.1% relative to 5-years average, and an increase of 6.2–7.7% relative to pre-lockdown. |

Nakada and Urban (2020) |

| Rio de Janeiro Mar. 2 – April 16 |

PM10: reduction ranges from 15.0% in 1st week to up to 33.3%. | Dantas et al. (2020) | |

| CHINA | Countrywide Jan. 1 – Feb. 25 |

Average concentration is 46 μg PM2.5/m3 (−14.8% year-on-year), 466 μg PM10/m3 (−20.5% year-on-year), | Wang and Su (2020) |

| INDIA | Countrywide Feb. 15 – May 3 Lockdown: Mr. 25 –May 3 |

PM2.5: Central India: 40.2% reduction to 25.8 ± 6.1 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 43.2 ± 6.7 μg/m3 (2017–2019), Indo Gangetic Plain: 47.4% reduction to 37.0 ± 10.5 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 70.3 ± 19.9 μg/m3 (2017–2019) North-west: 50.3% reduction to 30.5 ± 7.3 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 61.4 ± 22.6 μg/m3 (2017–2019) South: 43.6% reduction to 21.3 ± 6.6 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 37.7 ± 9.9 μg/m3 (2017–2019) PM10: Central India: 32.1% reduction to 74.0 ± 27.3 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 109.0 ± 31.0 μg/m3 (2017–2019), Indo Gangetic Plain: 55.7% reduction to 82.3 ± 26.3 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 185.8 ± 65.8 μg/m3 (2017–2019) North-west: 46.4% reduction to 68.4 ± 13.1 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 127.7 ± 37.4 μg/m3 (2017–2019) South: 48% reduction to 47.2 ± 9.2 μg/m3 in 2020 relative to 90.7 ± 15.2 μg/m3 (2017–2019) |

(V. Singh et al., 2020) |

| Ghaziabad Jan. 10 – Apr. 19. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 – Apr. 14 2nd Phase: Apr. 15 –May 3. |

PM2.5: 85.1% reduction as compared to pre-lockdown and 46.1% as compared to 2019. PM10: 50.8% reduction as compared to pre-lockdown, and 40.2% as compared to 2019. |

Lokhandwala and Gautam (2020) | |

| Chandigarh Mar. 25 –May 17. 1st Phase: Mar. 25 – Apr. 16 2nd Phase: Apr. 17 –May 3. 3rd Phase: 4th – 17th May. |

PM2.5: Pre-lockdown 20.1 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 14.3 μg/m3 (−28.9%), 2nd phase 15.4 μg/m3 (−23.4%), 3rd phase 19.8 μg/m3 (−1.5%). PM10: Pre-lockdown 56.9 μg/m3, Lockdown: 1st phase 35.9 μg/m3 (−36.9%), 2nd phase 43.9 μg/m3 (−22.8%), 3rd phase 55.5 μg/m3 (−2.5%). |

Mor et al. (2021) | |

| Five cities (Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kolkata, and Mumbai). Mar. 25 –May 11 |

Chennai: Average concentration is 13 ± 10 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2020 (−32% year-on-year), 19 ± 13, 16 ± 12, 23 ± 10 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2019, 2018, and 2017 respectively. Delhi: Average concentration is 40 ± 24 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2020 (−52% year-on-year), 84 ± 54, 71 ± 43, 84 ± 57 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2019, 2018, and 2017 respectively. Hyderabad: Average concentration is 31 ± 11 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2020 (−26% year-on-year), 42 ± 17, 54 ± 19, 68 ± 26 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2019, 2018, and 2017 respectively. Kolkata: Average concentration is 29 ± 17 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2020 (−24% year-on-year), 38 ± 16, 43 ± 16, 45 ± 13 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2019, 2018, and 2017 respectively. Mumbai: Average concentration is 28 ± 11 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2020 (−10% year-on-year), 31 ± 16, 44 ± 22, 46 ± 25 μg PM2.5/m3 in 2019, 2018, and 2017 respectively. |

(P. Kumar et al., 2020) | |

| IRAQ | Baghdad Jan. 2 -Jul. 24. 1st Partial and total lockdown Mar. 1 – Jun. 13. 2nd Partial lockdown Jun. 14 – Jul. 24 |

PM2.5: Pre-lockdown 40 μg/m3, 1st partial and total lockdown: 37 μg/m3, 2nd partial lockdown 39 μg/m3. PM10: Pre-lockdown 119 μg/m3, 1st partial and total lockdown: 101–185 μg/m3, 2nd partial lockdown 186 μg/m3. |

Hashim et al. (2021) |

| SPAIN | Countrywide Jan. 1 – Jun. 20 Strict lockdown: Mar. 14 –May 3. Relaxed lockdown: May 5 – Jun. 20. |

Urban areas:

|

Martorell-Marugán et al. (2021) |

| Barcelona March 14–30 |

PM10: Avarage concentration of 16.2 μg/m3 relative to 22.4 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (−27.8%) in Urban background. Avarage concentration of 20.2 μg/m3 relative to 29.2 μg/m3 pre-lockdown (−31.0%) in Traffic area. |

Tobías et al. (2020) | |

| UK | Countrywide January 1 – June 30 Locking-down: March 10 – April 10. Locked-down: April 11 – June 30. |

PM10 : 5.9–6.3 μg/m3 (+17%), PM2.5 3.9–5.0 μg/m3 (+17%) | Ropkins and Tate (2021) |

| Countrywide Mar. 30 – May 3 |

PM2.5: 22.6 μg/m3 (range of 21.1–34.4 μg/m3), an average reduction of about 42.9% (range of 40.7–57.8%) relative to the 2017–2019 average of the same time period. | Jephcote et al. (2020) | |

| USA | California Mar. 19 –May 7. |

PM2.5: −31% relative pre-lockdown 2020, and -25% relative to the normalized 2015–2019 concentrations. PM10: +21% relative pre-lockdown 2020, and -11% relative to the normalized 2015–2019 concentrations. |

Liu et al. (Q. Liu et al., 2021) |

| EUROPE | 27 European countries Mar. 1–31. |

PM2.5: Change relative to the same period in 2019 of Austria: Urban −10.3%, Rural −11.2%. Belgium: Urban −13.4%, Rural −15.7%. Bosnia Hzgv: Urban −5.8%, Rural −4.1%. Bulgaria: Urban −5.3%, Rural −4.8%. Croatia: Urban −11.6%, Rural −6.6%. Czech Republic: Urban −5.7%, Rural −8.5%. Denmark: Urban −6.3%, Rural −6.7%. France: Urban −18.0%, Rural −17.0%. Germany: Urban −11.7%, Rural −12.7%. Greece: Urban −11.0%, Rural −4.6%. Hungary: Urban −4.7%, Rural −7.1%. Italy: Urban −20.5%, Rural −17.8%. Ireland: Urban −11.1%, Rural −11.7%. Lithuania: Urban −4.9%, Rural −4.9%. Netherlands: Urban −10.4%, Rural −10.3%. Norway: Urban −6.7%, Rural −6.5%. Poland: Urban +4.0%, Rural −4.6%. Portugal: Urban −23.5%, Rural −13.0%. Romania: Urban −4.8%, Rural −4.8%. Russia: Urban −10.0%, Rural −2.5%. Serbia: Urban −5.9%, Rural −2.4%. Slovakia: Urban −8.3%, Rural −7.6%. Slovenia: Urban −18.4%, Rural −16.3%. Spain: Urban −13.8%, Rural −14.5%. Sweden: Urban −5.4%, Rural −5.5%. Switzerland: Urban −18.0%, Rural −22.0%. United Kingdom: Urban −15.0%, Rural −14.0%. |

Menut et al. (2020) |

3.1.6. Overall air quality improvements

From the previous discussions, the improvement in air quality and the reduced concentration of different air pollutants are clear. There has been a significant reduction in carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and particulate matter emissions due to the COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine measures. Additionally (Q. Wu et al., 2021), have reported a decrease in mercury concentration of 10–15% due to the lockdown measures in the China Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (BTH) region due to reducing mercury emissions by about 12.5 kg/d, i.e., 0.07 ng/m3. Fig. 8 below demonstrates the relative change in key air pollutants over Western Europe as compared to per-lockdown measures due to the COVID-19, which confirms the previously discussed results (Menut et al., 2020). The figure shows a decrease in NO2, NO3, and PM over most of Europe, along with an increase in O3 concentrations.

Fig. 8.

Map of Western Europe showing the tropospheric column density of major air pollutants (Menut et al., 2020).

3.2. Water resources quality

Water resources are expected to be affected by the COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine measures as well, but to less extent as compared to air. The quality of different natural water resources is expected to be improved due to the reduction or shutdown of many industrial activities at which wastewater streams are originated; hence less pollutants are to be discharged (Sivakumar, 2020). However, domestic wastewater is expected to be at the same level, as it is directly related to the population size. Many reports have indicated an improvement of different water resources such as river's surface water (F. Liu et al., 2021; Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020; Patel et al., 2020), lake (Yunus et al., 2020), and subsurface water (Selvam et al., 2020a).

Lokhandwala & Gautam have reported an increase in the dissolved oxygen (DO) in the Ganga river, India of about 23% from 6.5 ppm to 8 ppm in 2019 and 2020, respectively, during the same period of lockdown, along with a decrease of about 25% in biological oxygen demand (BOD) from 4 to 3 ppm, during the same periods, respectively (Lokhandwala and Gautam, 2020). While (Patel et al., 2020) have reported improved quality of the Yamuna's stretch within the megacity of Delhi, India of about 37% in the Water Quality Index, associated with a decrease of about 42.8 and 39.3% in BOD and chemical oxygen demand (COD), respectively due to the COVID-19 lockdown along with about 40% reduction in Faecal Coliform. Similarly (Yunus et al., 2020), have reported a decrease of about 15.9% in suspended particulate matter (SPM) in Vembanad Lake, India, due to the COVID-19 lockdown. The improved water quality at Bokhalef River, Morocco discharge mouth into the Atlantic ocean to be significantly improved mainly due to the COVID-19 lockdown, and hence cease of industrial activities, increasing the quality class from class D onward up to class A (Cherif et al., 2020). Fig. 9 demonstrates the improved water quality along the Vembanad Lake and Bokhalef River, with seven sampling points along the coast (S1–S7), and one sampling point, i.e. S5 at the Bokhalaef River discharge into the Atlantic Ocean.

Fig. 9.

Map of (a) Vembanad Lake, India (Yunus et al., 2020), and (b) Bokhalef River, Morocco discharge mouth (Cherif et al., 2020) demonstrating the increased water quality.

The improvement of water quality due to the COVID-19 lockdown has been shown to expand to subsurface water as well. The subsurface water quality has been improved in Tuticorin, India, due to the lockdown, showing a substantial decrease in heavy metals concentration and other water quality parameters (Selvam et al., 2020a). Reduction in heavy metals concentration of 51, 50, 42, 60, and 50% for Arsenic As, Cadmium Cd, Selenium Se, Iron Fe, and Lead Pb, along with reductions of 49% in nitrate concentration. For the biological parameters such as E. coli and fecal streptococci, no significant change was observed, however, a reduction of about 52 and 48% in total coliform and fecal coliform, respectively, was observed, which was attributed to the lockdown of nearby food and fish processing facilities.

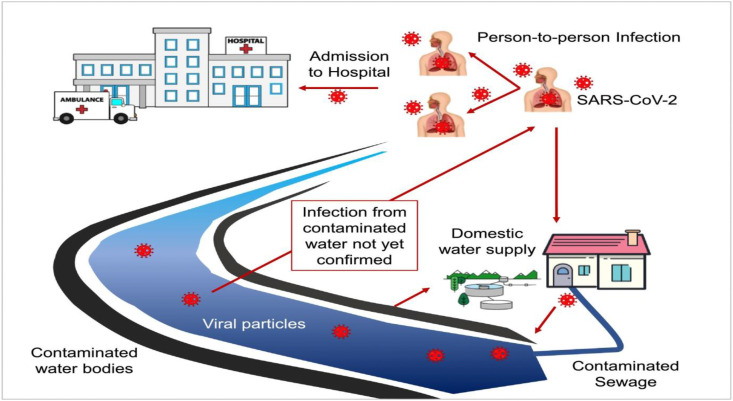

3.3. Wastewater quality

Wastewater is another environmental element that has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Contrary to atmospheric air and water resources that have shown an improved quality due to the COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine measures, which ceased many anthropogenic activities, a deterioration of wastewater quality was observed. The SARS-CoV-2 has been widely found in wastewater and wastewater solids in infected areas and even have been widely used as a tool for early detection and surveillance of the COVID-19 pandemic (D'Aoust et al., 2021; Gallardo-Escárate et al., 2020; M. Kumar et al., 2020; Larsen and Wigginton, 2020; Saguti et al., 2021). This, in return, has raised the concern of having the wastewater, if not properly treated, as a tool to transmit and hence increase the SARS-CoV-2 spread and infection (Gonzalez et al., 2020). Baldovin et al. have analyzed samples from different wastewater points such as pumping station, wastewater treatment plant inlet, and outlet and found that SARS-CoV-2 RNA was present in both untreated and treated wastewater, with persistence up to 24 h in samples kept at 4 °C (Baldovin et al., 2020). The relatively long half-life span of the SARS-CoV-2 of about 3 days in sewage systems and 3–4 days in solid feces have been the main concern, as it can result in the increased spread and infection rate (Nghiem et al., 2020). The potential SARS-CoV-2 spread through wastewater as demonstrated in Fig. 10 below has been carefully assessed (Adelodun et al., 2020). The most probable route is the exposure to the virus through the use of untreated water, in which sewage water has been disposed or seeped to, which is common in underdeveloped countries with poor water and wastewater treatment facilities.

Fig. 10.

Potential route for the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through wastewater (Adelodun et al., 2020).

The proper wastewater treatment in a well-designed and functioning wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) up to tertiary treatment with nutrients removal and efficient on-site sanitation, along with proper and reliable sludge treatment and discharge, should limit hazardous associated with biological matter, including bacteria and viruses including SARS-CoV-2 (Lahrich et al., 2021). Membrane bioreactor and advanced oxidation process with advanced biosensors have been proposed as an efficient tool for the biological treatment of wastewater for the control of SARS-CoV-2 spread upon integration in WWTP (Bedoui et al., 2011; Sayed et al., 2020; Tetteh et al., 2020; Wilberforce et al., 2020). Another approach is to have the wastewater generated by hospitals and highly infected areas treated according to a specific disinfection process before being discharged to municipality wastewater (J. Wang et al., 2020). The process involves primary disinfection, sedimentation, de-chlorination, moving bed reactor, and re-disinfection. In addition to the biological contamination of wastewater streams by SARS-CoV-2, the wastewater will be loaded with additional organic load due to the excessive hand wash, use of sanitizers, and disinfectants (Lahrich et al., 2021; Shakil et al., 2020). Furthermore, the wastewater is expected to be loaded with antibiotics and similar medication due to the increased use of these prescriptions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4. Solid waste

Since the hit of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a massive increase in the consumption of single-use medical supplies and personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face masks, gloves, aprons, coverall, and many others either for the use of medical and health staff or by normal people (Bhakta et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021; Raja et al., 2021). This, in return, has put pressure on the manufacturing facilities and the overall supply chain. However, one of the most persistent problems will be the proper waste management of such infected waste, which has to be performed properly in order to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Naughton, 2020; Sarkodie and Owusu, 2020; Zand and Heir, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has been found to affect the solid waste pattern both qualitatively and quantitatively, and hence change in solid waste management and treatment is needed (Fan et al., 2021; N. Singh et al., 2020). Incineration, chemical disinfection, and physical disinfection have been proposed as effective tools for medical waste, with priority to incineration whenever possible (J. Wang et al., 2020). Surprisingly, the disposal and incineration of such an increased rate of medical waste can result in some additional gaseous emissions, which can reduce the gained environmental benefits due to the COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine, but this is expected to be an insignificant reduction.

4. Conclusions

The world has witnessed by the start of 2020 the unprecedented pandemic of COVID-19 in the modern days. Since the inception of COVID-19 in mid-Dec. 2019, and the number of confirmed cases and deaths has reached 122 and 2.7 million, respectively all over the world by mid-March 2021. The quarantine measures and lockdown of social, commercial, and industrial activities have been taken in many countries to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The taken quarantine and lockdown measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in many environmental effects, which were desirable in most cases as it results in improved air and water resource quality. The work presented here compiles and provides a distinct overview of the different effects of the COVID-19 considering all the significantly affected elements of the environment, i.e., air, water resources, wastewater, and solid waste, in one report. The significant reduction in many air pollutants such as carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and particulate matter emissions have been globally reported, in addition to many other pollutants. This was also associated with increased ozone concentration due to the reduced nitrogen oxides concentration in atmospheric air. Similarly, water resources have shown an improved water quality of lower suspended matter and turbidity, along with reduced biological and chemical oxygen demand due to the reduced wastewater streams discharged to such water bodies.

Wastewater, on the other hand, has experienced a deteriorated quality due to the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which requires proper wastewater treatment to control COVID-19 infection spread. In addition, the increased use of hand sanitizers and disinfectants, as well as some medications, has been shown to increase the organic load in wastewater. Solid waste is another area in which the COVID-19 pandemic has affected negatively both qualitatively and quantitatively due to the increased consumption of single-use medical supplies and personal protective equipment. Hence proper solid waste management is a must.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abdelkareem M.A., Elsaid K., Wilberforce T., Kamil M., Sayed E.T., Olabi A.G. Environmental aspects of fuel cells: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;752:141803. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adame J.A., Gutierrez-Alvarez I., Bolivar J.P., Yela M. Ground-based and OMI-TROPOMI NO2 measurements at El Arenosillo observatory: unexpected upward trends. Environ. Pollut. 2020;264:114771. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams M.D. Air pollution in ontario, Canada during the COVID-19 state of emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140516. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelodun B., Ajibade F.O., Ibrahim R.G., Bakare H.O., Choi K.S. Snowballing transmission of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) through wastewater: any sustainable preventive measures to curtail the scourge in low-income countries? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140680. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agathokleous R., Bianchi G., Panayiotou G., Arestia L., Argyrou M.C., Georgiou G.S., Tassou S.A., Jouhara H., Kalogirou S.A., Florides G.A., Christodoulides P. Waste heat recovery in the EU industry and proposed new technologies. Energy Procedia. 2019;161:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.02.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antturi J., Hänninen O., Jalkanen J.P., Johansson L., Prank M., Sofiev M., Ollikainen M. Costs and benefits of low-sulphur fuel standard for Baltic Sea shipping. J. Environ. Manag. 2016;184:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APHA . twentieth ed. The American Public Health Association; 2018. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. twentieth ed. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldasano J.M. COVID-19 lockdown effects on air quality by NO 2 in the cities of Barcelona and Madrid ( Spain ) Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741:140353. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldovin T., Amoruso I., Fonzo M., Buja A., Baldo V., Cocchio S., Bertoncello C. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and persistence in wastewater samples: an experimental network for COVID-19 environmental surveillance in Padua, Veneto Region (NE Italy) Sci. Total Environ. 2020;143329 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo D. An environmental and health perspective for COVID-19 outbreak: meteorology and air quality influence, sewage epidemiology indicator, hospitals disinfection, drug therapies and recommendations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8:104006. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoui A., Elsaid K., Bensalah N., Abdel-Wahab A. Treatment of pharmaceutical-manufacturing wastewaters by UV irradiation/hydrogen peroxide process. J. Adv. Oxid. Technol. 2011;14:226. doi: 10.1515/jaots-2011-0207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta H., Raja K., Shankar V.R., Prakash V. Resources , Conservation & Recycling Challenges , opportunities , and innovations for effective solid waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;162:105052. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E. First data analysis about possible COVID-19 virus airborne diffusion due to air particulate matter (PM): the case of Lombardy (Italy) Environ. Res. 2020;186:109639. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briz-Redón Á., Belenguer-Sapiña C., Serrano-Aroca Á. Changes in air pollution during COVID-19 lockdown in Spain: a multi-city study. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2021;101:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2020.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz A., Galli A., Hasekamp O., Landgraf J., Tol P., Aben I. TROPOMI aboard Sentinel-5 Precursor: prospective performance of CH 4 retrievals for aerosol and cirrus loaded atmospheres. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012;120:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2011.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) WWW Document]; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Mukherjee S., Dutta M., Ghosh A., Ghosh S.K., Roy A. High rise in carbonaceous aerosols under very low anthropogenic emissions over eastern Himalaya, India: impact of lockdown for COVID-19 outbreak. Atmos. Environ. 2021;244:117947. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.W.A., Chien L.C., Li Y., Lin G. Nonuniform impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on air quality over the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;745:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhang S., Peng C., Shi G., Tian M., Huang R.J., Guo D., Wang H., Yao X., Yang F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and control measures on air quality and aerosol light absorption in Southwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;749:141419. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherif E.K., Vodopivec M., Mejjad N., da Silva J.C.G.E., Simonovič S., Boulaassal H. vol. 12. Water (Switzerland); 2020. (COVID-19 Pandemic Consequences on Coastal Water Quality Using WST Sentinel-3 Data: Case of Tangier, Morocco). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Lang J., Chen T., Mao S., Cheng S., Wang Z., Cheng N. A framework for investigating the air quality variation characteristics based on the monitoring data: case study for Beijing during 2013–2016. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2019;81:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas G., Siciliano B., Boscaro B., Cleyton M., Arbilla G. Science of the Total Environment the impact of COVID-19 partial lockdown on the air quality of the city of Rio de Janeiro , Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:139085. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aoust P.M., Mercier E., Montpetit D., Jia J.J., Alexandrov I., Neault N., Baig A.T., Mayne J., Zhang X., Alain T., Langlois M.A., Servos M.R., MacKenzie M., Figeys D., MacKenzie A.E., Graber T.E., Delatolla R. Quantitative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from wastewater solids in communities with low COVID-19 incidence and prevalence. Water Res. 2021;188:116560. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid K., Kamil M., Sayed E.T., Abdelkareem M.A., Wilberforce T., Olabi A. Environmental impact of desalination technologies: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;748:141528. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid K., Sayed E.T., Abdelkareem M.A., Baroutaji A., Olabi A.G. Environmental impact of desalination processes: mitigation and control strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;740:140125. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid K., Sayed E.T., Abdelkareem M.A., Mahmoud M.S., Ramadan M., Olabi A.G. Environmental impact of emerging desalination technologies: a preliminary evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8:104099. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.104099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid K., Taha Sayed E., Yousef B.A.A., Kamal Hussien Rabaia M., Ali Abdelkareem M., Olabi A.G. Recent progress on the utilization of waste heat for desalination: a review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020;221:113105. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid K., Olabi A., Wilberforce T., Abdelkareem M.A., Sayed E.T. Environmental impacts of nanofluids: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;763:144202. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo W., Celis J.E., Chiang G., Bahamonde P. Environment and COVID-19: pollutants, impacts, dissemination, management and recommendations for facing future epidemic threats. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;747:141314. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. Van, Jiang P., Hemzal M., Klemeš J.J. An update of COVID-19 influence on waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020;264:114732. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Guo M., Fan L., Deng Q., Han D., Wei Y., Luo J., Qin G., Cheng J. Ozone pollution mitigation in guangxi (south China) driven by meteorology and anthropogenic emissions during the COVID-19 lockdown. Environ. Pollut. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115927. 115927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaete-Morales C., Gallego-Schmid A., Stamford L., Azapagic A. Life cycle environmental impacts of electricity from fossil fuels in Chile over a ten-year period. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;232:1499–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Escárate C., Valenzuela-Muñoz V., Núñez-Acuña G., Valenzuela-Miranda D., Benaventel B.P., Sáez-Vera C., Urrutia H., Novoa B., Figueras A., Roberts S., Assmann P., Bravo M. The wastewater microbiome: a novel insight for COVID-19 surveillance. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;142867 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremanloo M., Lops Y., Choi Y., Mousavinezhad S. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on air pollution levels in East Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754:142226. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R., Curtis K., Bivins A., Bibby K., Weir M.H., Yetka K., Thompson H., Keeling D., Mitchell J., Gonzalez D. COVID-19 surveillance in Southeastern Virginia using wastewater-based epidemiology. Water Res. 2020;186:116296. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith S.M., Huang W.S., Lin C.C., Chen Y.C., Chang K.E., Lin T.H., Wang S.H., Lin N.H. Long-range air pollution transport in East Asia during the first week of the COVID-19 lockdown in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara M., Martínez F., Arévalo G., Gassó S., Baldasano J.M. An improved system for modelling Spanish emissions : HERMESv2 . 0. Atmos. Environ. 2013;81:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.08.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashim B.M., Al-Naseri S.K., Al-Maliki A., Al-Ansari N. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations and assessing air quality changes in Baghdad. Iraq. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754:141978. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higson S. Oxford University; 2004. Analytical Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins University Johns. 2020. Coronavirus resources center. [WWW document] [Google Scholar]

- Ingmann P., Veihelmann B., Langen J., Lamarre D., Stark H., Courrèges-Lacoste G.B. Requirements for the GMES atmosphere service and ESA's implementation concept: sentinels-4/-5 and -5p. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012;120:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2012.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency . 2020. The 2019 Global Energy & CO2 Status Report. ([WWW Document]) [Google Scholar]

- Jephcote C., Hansell A.L., Adams K., Gulliver J. Changes in air quality during COVID-19 ‘lockdown’ in the United Kingdom. Environ. Pollut. 2020;116011 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouhara H., Olabi A.G. Editorial: industrial waste heat recovery. Energy. 2018;160:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2018.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Júnior E.P.B., Arrieta M.D.P., Arrieta F.R.P., Silva C.H.F. Assessment of a Kalina cycle for waste heat recovery in the cement industry. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019;147:421–437. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2018.10.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanniah K.D., Kamarul Zaman N.A.F., Kaskaoutis D.G., Latif M.T. COVID-19's impact on the atmospheric environment in the Southeast Asia region. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736:139658. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Patel A.K., Shah A.V., Raval J., Rajpara N., Joshi M., Joshi C.G. First proof of the capability of wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 in India through detection of genetic material of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;746:141326. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]