Abstract

Introduction

Delayed reduction of the hip in femoral head fracture dislocation increases the risk of osteonecrosis and adversely affects the functional outcome.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was designed to evaluate the outcome and complications of 138 patients with femoral head fracture dislocation treated by a single surgeon over a period of 22 years. Only seven patients presented within 24 h of injury and remaining all presented late. The hip joints could be reduced by closed manoeuvre in 105 patients, and 33 patients needed open reduction. The patients were managed conservatively or surgically. The mean follow-up period was 3.57 years (1–18 years).

Results

There were 119 males and 19 females. The mean age was 35.71 years (range, 18–70 years). Forty-two patients were managed conservatively, and 96 patients needed surgical treatment. The Kocher-Langenbeck approach was used in 40 patients, the trochanteric flip osteotomy in 14 patients, the Smith-Peterson approach in 31 patients, and the Watson-Jones approach in one patient. The femoral head fragment was fixed in 47.82% patients and excised in 11.59% patients. Primary total hip replacement (THR) was performed in 7.24% of patients through the posterior approach. 24.63% of patients developed complications with 14.49% of hip osteonecrosis, 2.89% posttraumatic osteoarthritis and 2.17% femoral head resorption. 55% of patients who developed osteonecrosis were operated through the posterior approach. Secondary procedures were needed in 14.48% of patients. The clinical outcome, as evaluated using the modified Harris Hip Score, was good to excellent in 52.89% of patients and poor to fair in 47.11% of patients.

Conclusion

The incidences of osteonecrosis and secondary procedures are increased in delayed and neglected femoral head fracture dislocation. Osteonecrosis is commonly seen in Brumback 2A injuries and posterior-based approaches. All Brumback 3B fractures in such delayed cases should be treated with THR. Osteosynthesis or conservative treatment should be reserved for other types of injuries. A careful selection of treatment plan in such delayed cases can result in a comparable functional outcome as reported in the literature.

Keywords: Pipkin fracture dislocation, Brumback classification, Hip fracture, Hip dislocation, AVN, Osteonecrosis, Harris hip score

Introduction

Femoral head fracture dislocation is an uncommon injury. It is often seen after a high-velocity road traffic accident or after a fall from height. Posterior hip dislocation is usually associated and hence is the eponym ‘femoral head fracture-dislocation’. It has been observed that 4–17% of posterior hip dislocations are associated with femoral head fracture [13, 17, 22].

There have been numerous classification systems proposed for such type of injury, but none of these classifications provides recommendations for treatment, and neither have prognostic values [2, 6, 18]. Pipkin proposed a classification for such injury in 1957 where any femoral head fracture distal to the fovea capitis was labelled as type I and any fracture proximal to the fovea capitis involving the eight-bearing dome was categorized as type II. The fracture with associated femoral neck fracture was labelled as type III, and when it was associated with acetabular wall fracture, it was classified as type IV [18]. However, this classification system did not mention about the cartilaginous or osteochondral injuries of the femoral head. Brumback in 1987 included the indentation and transchondral injuries of the femoral head in his classification system [2].

The management of such injury depends on the reducibility of the hip, fracture location, size of the fragment, displacement, hip stability and associated acetabular fracture [6, 10, 22, 26]. The surgical management of this fracture is still controversial because there is no consensus on the surgical approaches [6, 7, 19] Regarding the surgical treatment, whether to fix or excise the fragment is debatable. Similarly, the fracture fixation techniques are also not defined [6, 7, 19, 22].

Despite controversies in surgical management, the principle of treatment is clearly defined. An emergent closed reduction of the hip followed by definite treatment either by closed manoeuvre or open reduction with the aim of anatomic restoration of joint and anatomical fracture reduction is the principle of management in such fractures [6, 7, 19]. The common complications such as osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), posttraumatic osteoarthritis and heterotopic ossifications (HO) make the outcome worse in these young trauma victims. The delay in presentation to the hospital or delay in diagnosis because of associated severe life-threatening injuries has an adverse impact on the outcome [6, 7, 19]. Most of the patients with such injuries present after 24 h of injury in developing countries. The functional outcome and complications in such delayed presenters have been evaluated in this retrospective study.

Materials and Methodology

All patients with femoral head fracture dislocation treated by a single surgeon between 1st January 1997 and 31st January 2019 were retrospectively evaluated. The details of the patients as entered into the trauma proforma of the operating surgeon were assessed for their injury pattern and treatment. Patients of more than 18 years of age with at least 1-year follow-up and having all radiological and clinical details were included. Patients with pathological fracture, open injuries and inadequate data were excluded. There were 168 femoral head fracture dislocations that were operated during this period. However, 30 patients were excluded because of inadequate data and follow-up; the remaining 138 patients were included in this study.

All patients received primary emergency care. After that, they were evaluated clinically for their femur head fracture dislocation. The radiological evaluation included the anteroposterior radiograph of pelvis with bilateral hip joints. The injury was classified as per Brumback and Pipkin classification. The hip dislocation was reduced immediately under sedation/general anesthesia using Alli’s manoeuvre [7]. If it could not be reduced after two to three attempts, immediate open reduction and internal fixation was planned. Patients with combined femoral head and neck fractures or isolated neck fracture with hip dislocation were planned for open reduction without any attempt of closed reduction. The patients were treated conservatively or surgically using the Kocher-Langenbeck approach, Smith-Peterson Approach, trochanteric flip osteotomy or Watson-Jones approach. If there was an anatomic reduction of the hip and femoral head fracture along with the absence of intraarticular fragment and stable joint, nonoperative treatment was adopted (Fig. 1). In the conservatively managed group, postoperative traction was applied in abduction for 6 weeks with regular radiographic follow-up. The surgical treatments adopted were fixation using Herbert screw or small fragment screws/mini-screws (2, 2.5 or 3.5 mm) for large fracture fragments and excision in case of a small fragment, not amenable for fixation. Postoperative traction was used in these patients, but no prophylactic medication was provided to prevent HO. The patients treated until 2006 did not receive any chemoprophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis. However, all patients treated after 2006 received chemoprophylaxis (Low molecular weight heparin, Enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneous). The hip joint congruity and fracture reduction were assessed with a postoperative/post-reduction radiograph. The computed tomographic scan was performed in 92 patients. These patients were followed-up after 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and yearly afterwards. The clinical outcome, complications and functional outcome were evaluated using the modified Harris Hip Score (HHS) [9, 15]. While the outcome of primary THR was evaluated using modified HHS after the arthroplasty, the outcome in patients needing secondary THR was considered as a poor outcome as THR was the endpoint of treatment. The mean follow-up period in our study was 3.57 years (1–18 years).

Fig. 1.

a 47-year female presented with left-sided femoral head fracture (infrafoveal, Pipkin type I, Brumback type 1A) with posterior hip dislocation, (b) Closed reduction was performed, and the postoperative radiograph showed congruent joint with well-aligned fracture fragment, (c) 10-years after surgery, radiograph showed completely healed fracture with no degeneration in the joint (d) Her functional outcome was excellent and she was able to perform the daily activities

Results

There were 119 males and 19 females. The mean age was 35.71 years (range 18–70 years). Only four patients were above 60 years of age. The mode of injury was a road traffic accident in 121 patients, and fall from height in the remaining 17 patients. There were 81 associated injuries in 66 patients. There were 15 head injuries, five pelvic fractures, 51 associated acetabulum fractures, three sciatic nerve injuries, and 7 miscellaneous injuries. None of the patients had a severe head injury. There were 128 posterior hip dislocations, eight anterior hip dislocations and two central fracture dislocations. One hundred twenty-eight patients presented within 6 weeks (mean duration of presentation 4.5 days, range 15 h to 18 days) of injury and ten patients presented after 6 weeks. These ten patients were considered as a “late” presenter, and the injury was labelled as ‘neglected injury’. None of the patients presented within 6 h of injury, and the dislocated hip could not be reduced within the golden hours; hence, these patients were labelled as “delayed presentation”. Of seven patients (0.05%) who arrived at our service within 24 h of injury, the hip joint could be reduced by the closed manoeuvre. In total, the hip dislocation could be reduced by closed manipulation in 105 patients, and the remaining patients needed open reduction.

As per Brumback classification, there were 60 Brumback type 1 injuries (35 type 1A and 25 type 1B, Fig. 1), 54 Brumback type 2 injuries (47 type 2A and 7 type 2B, Figs. 2, 3), 14 type 3 injuries (3 type 3A and 11 type 3B, Fig. 4), 8 type 4 injuries (4 type 4A and 4 type 4B, Fig. 5) and 2 type 5 injuries.

Fig. 2.

a, b An interesting case of Brumback type 2A/ Pipkin type II fracture-dislocation in a 34-year male where the femoral head fragment was reversed after hip reduction, (c) Open reduction and internal fixation was performed with small fragment partially threaded screws through Smith-Peterson approach, (d, e) 11-years after the surgery, the radiographs do not show any evidence of arthritis, (f, g) he could perform all daily activities

Fig. 3.

a 29-year male with Brumback type 2A/ Pipkin type III fracture-dislocation, (b); Closed reduction was done, and internal fixation was performed through Ganz’s safe surgical hip dislocation. Radiograph after 7 years shows no evidence of osteonecrosis or arthritis. c; the patient had excellent functional activities

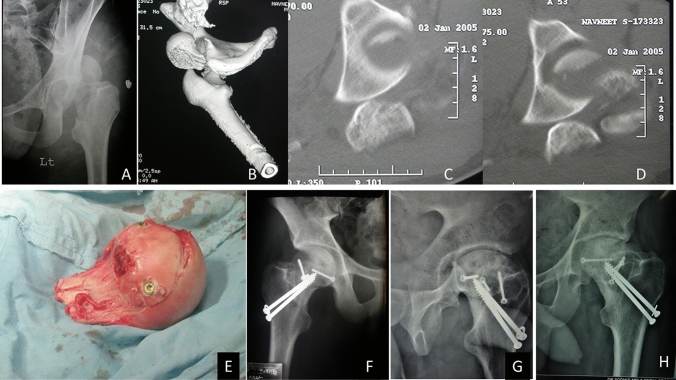

Fig. 4.

a–d Radiograph and CT scan of Brumback type 3B/ Pipkin type III fracture-dislocation in a 19-year male, (e) The femoral head was reconstructed on the table and then fixed with neck using large fragment partially threaded screws, (f) postoperative radiograph shows the anatomical reconstruction of the femoral head and neck, (g) 5 years after fixation, there was osteonecrosis with femoral head collapse and healing, (h) 8 years after the fixation, the healed osteonecrosis has progressed to femoro-acetabular impingement with mild osteoarthritis changes in the hip, but the functional outcome of the patient is fair as evaluated using modified HHS

Fig. 5.

a 24-year male with Right-sided Brumback type 4B injury after closed reduction, (b) Intraoperative picture shows transchondral injury, (c) fixation with multiple mini-screws, (d) 2-years follow up X-ray shows no degeneration in the joint

42 (30%) patients were managed conservatively, and 96 (70%) patients needed surgical treatment. The anterior approach (Smith-Peterson approach) was used in 31 patients (Fig. 2), and the anterolateral (Watson-Jones) approach was used in one patient. The posterior surgical approach (Kocher-Langenbeck approach) was used in 40 patients for fixation or excision. The trochanteric flip osteotomy was performed in 14 patients (Fig. 3). The femoral head fragment was fixed in 47.82% (66/138) patients and excised in 11.59% (16/138) patients. In 4 (2.89%) patients with Brumback 1B/Pipkin IV fracture dislocation, the reduction of the femoral head fracture fragment was acceptable; so, it was not fixed, but the associated acetabular fracture was stabilized (Fig. 6). Primary total hip replacement (THR) was performed in 10 (7.24%) patients through the posterior approach. Secondary procedures were needed in 14.48% of patients.

Fig. 6.

a 59-year old male with Brumback type 1B/Pipkin type IV fracture-dislocation, (b) Axial cut section of CT scan shows femoral head fracture and posterior wall acetabulum fracture, (c) The femoral head fragment was excised, and acetabulum fracture was fixed with 3.5 mm reconstruction plate and lag screw, (d, e) 11-years after surgery, the X-ray showed the hip joint degeneration, but the patient had fair outcome

Complications and outcome based on Brumback classification (Tables 1, 2)

Table 1.

Complication and clinical outcome of femoral head fracture dislocation with minimal acetabular rim fracture/without acetabular fracture (n = 104)

| Brumback | Conservative | FH fixation | FH excision | THR | Complications | Secondary procedure | Outcome (Harris Hip Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 24 | 7 | 4 |

1 nonunion 3 osteonecrosis 1 malunion causing FAI |

1 sciatic nerve decompression 2 CD/stem cell 1 THR |

4 poor 9 fair 12 good 10 excellent |

|

| 2A | 6 | 41 (1 allograft) | 14 osteonecrosis, 1 HO, 3 OA, 1 posttraumatic femoral neck fracture |

1 neck fixation 4 CD/stem cell 5 THR |

11 poor 14 fair 12 good 10 excellent |

||

| 3A | 1 | 2 |

1 excellent 2 good |

||||

| 3B | 5 | 6 |

2 infection 2 osteonecrosis 1 OA |

2 Girdlestone arthroplasty 2 THR |

4 poor 1 fair 2 good 4 excellent |

||

| 4A | 3 | 1 |

1 poor 2 fair 1 good |

||||

| 4B | 2 | 1 | 1 |

1 poor 1 fair 2 good |

|||

| Total | 35 (25.36%) | 56 (40.57%) | 5 (3.62%) | 8 (5.79%) | 29 (21.01%) | 18 (13.04%) |

21 poor 27 fair 31 good 25 excellent |

FH femoral head, FAI Femoro-acetabular impingement, HO heterotopic ossification; OA osteoarthritis, CD Core decompression, THR total hip replacement

Table 2.

Complication and clinical outcome of femoral head fracture dislocation with major acetabular fracture (n = 34)

| Brumback | Conservative (both FH and Ac) | FH fixation, Ac fixation | FH excision, Ac fixation | FH Closed reduction, Ac fixation | THR | Complications | Sec procedures | Outcome (Harris Hip Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 4 | 4 | 11 | 4 | 2 |

2 femoral head resorption 1 osteonecrosis 1 hip instability |

1 THR |

4 poor 8 fair 8 good 5 excellent |

| 2B | 3 | 4 | 1 femoral head resorption | 1 THR |

2 poor 3 fair 1 good 1 excellent |

|||

| 5 | 2 | – | – |

1 good 1 excellent |

||||

| Total | 7 (5.07%) | 10 (7.24%%) | 11(7.97%) | 4 (2.89%) | 2 (1.44%) | 5 (3.62%) complications | 2 (1.44%) |

6 poor 11 fair 10 good 7 excellent |

FH femoral head, Ac acetabulum, THR total hip replacement

34 (24.63%) patients had major complications until the latest follow up, and the most common complication was ONFH (14.49%, Fig. 4). Among patients developing ONFH, the posterior approach was used in 11 patients (55%), trochanteric flip osteotomy in four patients, the Smith-Peterson approach in two patients and non-surgical management in remaining three patients. The ONFH was the most frequent complication in patients with femoral head fracture dislocation without major acetabulum fracture (19/104, 18%) and the femoral head osteolysis or resorption was commonly seen in associated acetabular injuries (3/34, 9%). Only four patients had posttraumatic OA, and one patient developed HO. Secondary procedures were commonly needed in Brumback type 2A and type 3B injuries. The sciatic nerve injury recovered completely in two patients, and only one patient (Brumback 1A) needed sciatic nerve decompression. Overall, the clinical outcome was good to excellent in 52.89% and poor to fair in 47.11%. There was good–excellent outcome in 53.84% of patients with minimal or no acetabular rim fracture and 50% of patients with a major acetabular fracture.

Complications and outcome based on Pipkin’s classification (Table 3)

Table 3.

Outcome evaluation as per Pipkin’s fracture dislocation (n = 127)

| Pipkin | Conservative | FH fixation | FH excision | FH Closed reduction, Ac fixation | THR | Complications | Secondary procedures | Outcome (Harris hip Score) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | 19 | 5 | 2 |

1 nonunion 2 osteonecrosis 1 malunion causing FAI |

1 CD/stem cell 1 THR |

2 poor 4 fair 10 good 10 excellent |

||||||

| Type II | 3 | 36 (1 allograft) | 10 osteonecrosis, 1 HO, 2 OA, 1 posttraumatic femoral neck fracture |

1 neck fixation 3 CD/stem cell 3 THR |

9 poor 10 fair 11 good 9 excellent |

|||||||

| Type III | 5 | 6 |

2 infection 2 osteonecrosis 1 OA |

2 Girdlestone arthroplasty 2 THR |

4 poor 1 fair 2 good 4 excellent |

|||||||

| Type IV | 15 | 17 (10 Ac fixation) | 13 (11 Ac fixation) | 4 | 2 |

3 femoral head resorption 6 osteonecrosis 1 OA 1 hip instability |

1 sciatic nerve decompression 4 THR 2 CD/stem cell |

10 poor 20 fair 13 good 8 excellent |

||||

| Total | 37 (29.13%) | 63 (49.6%) | 15 (11.81%) | 4 (3.14%) | 8 (6.29%) | 34 (26.77%) | 20 (15.74%) |

25 poor 35 fair 36 good 31 excellent |

||||

FH femoral head, Ac acetabulum, FAI Femoro-acetabular impingement, HO heterotopic ossification; OA osteoarthritis, CD Core decompression, THR total hip replacement

There was 26 Pipkin’s type I fracture, 39 Pipkin’s type II, 11 Pipkin’s type III and 51 Pipkin’s type IV fracture dislocations. Only 15% of patients had a complication in Pipkin type I fracture dislocation, and 8% of patients needed secondary surgery. About 36% of patients developed complications in Pipkin type II injuries. The most common complication was the development of ONFH (25.64%). All except one patient with hip dislocation and femoral head–neck fractures (Brumback type 3B/Pipkin III) failed after fixation, and two of them were converted to Girdlestone arthroplasty because of deep infection. Another two needed THR after the development of osteonecrosis. Out of 11 patients of Pipkin III fracture, ultimately ten patients ended up with THR or Girdlestone arthroplasty. The clinical outcome, as evaluated using Harris hip score showed 52.75% good-to-excellent outcome and 47.25% poor-to-fair outcome. There was good-to-excellent outcome in 60.52% of patients without acetabular fracture and 41.17% of patients with acetabular fracture.

Outcome in late presenter (> 6 weeks)

There were 4 Brumback type 1 injuries (2 type 1A, 2 type 1B), 5 type two injuries (1 type 2A and 4 type 2B) and one type 3B injury. At the time of presentation, the hip joint was in reduced position in four patients, and the remaining six patients had a dislocated hip. Two patients with type 1A injuries were managed conservatively as the reduction was acceptable. The hip joint was reduced, and the fragment was excised in one patient. Femoral head allograft was used in one patient, and remaining all patients were advised THR. Three patients were treated with THR, and the remaining three refused for surgery. Overall, three patients had excellent outcome, two had good, two had fair, and three had a poor outcome.

Discussion

The surgical complexities, articular part involvement and high-velocity injury with peculiar anatomy of the femoral head (supplied by end artery) make the outcome worse in femoral head fracture dislocations [6, 7, 19]. Delayed presentation and hence, delayed reduction of the hip further worsen the outcome in these young trauma victims. Few patients end up with an unsatisfactory outcome because of the development of osteoarthritis, instability or osteolysis. Giannoudis et al. reported 62.6% good-to-excellent outcome in their review of 11 articles with 155 patients where Pipkin fracture classification was used. In the same review, they reported 54.8% good-to-excellent outcome in 55 patients from 4 articles where the injury was classified using Brumback classification [6]. Henle et al. reported that 56% of patients had good-to-excellent outcome [10]. Of 138 patients in our series, 53% had good-to-excellent outcome whereas 27.53% had fair, and 15.21% had poor outcomes. Despite a delay in presentation, the functional outcome in this series was comparable to that of reported in the literature; this was possible because of a careful selection of treatment plan based on the type of fracture, age of the patients, duration of the delay and hip arthritis status.

The acetabular fracture involvement in Brumback 1B, 2B and 5 include the major acetabular fractures (that make the hip joint unstable) and the central fracture dislocation of the hip. However, Pipkin IV fracture dislocation includes minor rim fractures to major acetabular fractures. Based on both the classifications, it was observed that the outcome was worse when there was associated acetabulum fracture. Another observation was that the rate of good–excellent outcome declined with the increasing severity of fractures. There was 77% of good-to-excellent outcome in Pipkin I injury and only 41% good–excellent outcome in Pipkin IV fracture.

Femoral head fracture dislocation needs urgent hip reduction [6, 7, 19]. Unfortunately, we could not reduce any patient within the golden period of 6 h because of late arrival or missed initial diagnosis. This late reduction had an adverse consequence on the outcome as a significant proportion of these patients ended up with ONFH (14.5%) [11, 12, 20, 30]. Again, the success of closed reduction in our series (76%) was also less than the average success rate of 84% as reported by Giannoudis et al. It is a norm that immediately after reduction, the joint congruity and fracture reduction should be assessed using Computed tomography (CT) [6, 16]. As the patients recruited in this series were since 1997, only 92 patients could be evaluated using CT after reduction.

While conservative treatment was the mainstay of treatment in Brumback 1A/ Pipkin type I injury, open reduction and internal fixation was needed in Brumback 1B, 2 and 5/Pipkin II and IV injuries. The Brumback 3B/Pipkin type III injuries failed after ORIF and invariably needed THR.

Nonoperative treatment was adopted in 30.43% of patients, and it was slightly more than that reported in the literature (22.9%). However, joint stability and restoration of the joint congruity along with the reduction of the fracture fragment was confirmed before embarking on the non-surgical treatment [6, 7, 19]. It has been well documented that Pipkin type I fracture can be managed conservatively, but it is difficult to maintain the reduction and delay the rehabilitation in patients with fracture fragment extending above fovea or in associated significant acetabular fractures [3]. Thirteen patients in this series (Brumback 2A, IB and 2B) were maintained in a strict bed rest protocol with traction along with frequent serial radiographs for confirmation of maintained reduction.

Regarding surgical approaches, the trochanteric flip osteotomy and anterior Smith Peterson approach have shown better outcome and minimal morbidity [4, 8, 14, 19, 22, 23, 25, 28]. The anterior approach provides excellent exposure with minimal blood loss and shorter operative time, but there is increased risk of HO. Contrary to it, the posterior approach does not allow access to the anterior fracture fragment because of the interposition of the femoral head [5, 8, 14, 23, 25]. With the trochanteric flip osteotomy and anterior hip dislocation, there is adequate exposure and access to all the parts of the femoral head and acetabular rim for fixation [4, 5, 14, 28]. It is considered as a safe approach having all the advantages of anterior approach with minimal risk of HO because of less retraction or damage to the abductor muscles [4, 5, 14, 28]. We used the posterior approach in 40 patients during our initial period as we did not have sufficient training on trochanteric flip osteotomy. Of 86 patients who went for surgical fixation or excision, we adopted the anterior approach or trochanteric flip osteotomy in 54 patients (63%). Among patients who developed ONFH (20 patients), the posterior approach was used in 11 patients (55%).

Although fragment excision provides a better outcome than fixation in Pipkin I injury [6, 7, 19], it is difficult to draw any conclusion from this series as very few patients have been treated surgically. However, the complication rate and secondary intervention were minimal in this group. The complication rate and secondary interventions in Pipkin II fracture were more than Pipkin IV injuries in our patients. Because of delayed reduction of the hip, a majority of the Pipkin type II fractures in our series developed ONFH and hence there was increase in complication rate and secondary procedures. Pipkin type III fracture was least common with an incidence of 8.7%. Although ORIF has been the standard of care in young trauma victims and THR is reserved for elderly individuals [13], our observation is not in support of this perception. Four of five patients in this series failed after fixation and ultimately ended up with THR or girdlestone arthroplasty. A recent article by Scolaro and his team reported a 100% failure rate after internal fixation of Pipkin III injuries, and that was the largest study in the world till date [28]. With the availability of good implant having better survivorship, probably THR is a better option even in young individuals [6, 21, 27]. However, if the artificial prosthesis cannot fulfil the functional demands of the patient, open reduction and internal fixation is justified but with a risk of failure [27]. We observed good outcome in the indentation and transchondral injuries of the femoral head. However, with a small number of patients, the treatment outcome is difficult to judge.

The incidence of ONFH was relatively high in this series (14.5%) compared to the literature. There were 8.7% and 11.8% of ONFH in femoral head fracture dislocation as reported by Scolaro et al. and Giannoudis et al., respectively [6, 21]. Even Tonetti and his associates reported only 8% of ONFH in their series [26]. The relatively high incidence of ONFH in our series was probably because of delayed hip reduction and posterior based approaches. Previous studies have shown that the posterior surgical approach is associated with 3.2 times increased risk of osteonecrosis [8, 23, 25]. Another frequent complication, as reported in the western literature, is HO. In the systematic review, Ginnadious et al. reported 35.6% HO [6]. Scolaro et al. also reported a 40% incidence of HO in their series [21]. Only one patient of Brumback type 2A or Pipkin type II developed HO in our series, and that was of Brooker type I severity without functional limitation. Unlike western literature, HO is not a major problem in the Indian subcontinent. None of the patients in our series received prophylaxis to prevent HO. However, none of these patients had a severe head injury that warranted a prolonged immobilization/ intensive care management. A typical complication that we observed in our series was the development of femoral head osteolysis or resorption. We noted four patients with femoral head resorption mainly with the associated acetabular fracture; probably, significant trauma to the osteoarticular cartilage induces the osteolysis process.

There is no consensus on the outcome evaluation in patients treated with THR for femoral head fracture dislocation. While evaluating the outcome using Thompson and Epstein score or Merle d’Aubigne and Postel score, the previous studies reported the outcome of primary THR patients either as poor or good [6, 13]. Few authors believed that THR below 60 years of age is not justifiable and hip joint preservation should be the aim. Hence, they considered the outcome as poor [13]. With the current treatment protocol, THR is a well-accepted treatment for Pipkin type III injuries, elderly individuals and in neglected cases where reconstruction is not feasible or joint is arthritic [6, 21, 27]. We evaluated the outcome using HHS in such primary THR after the arthroplasty procedure. However, patients needing secondary THR for arthritis after initial conservative or surgical treatment in Pipkin fracture dislocation denote the “complication” or “treatment failure”; hence, the clinical outcome (HHS) in such patients were evaluated before the arthroplasty procedure (invariably it was poor). We chose the Harris hip score for outcome evaluation in our study, because it is used extensively worldwide, it is more familiar, and there is no validated clinical score available for treatment evaluation of femoral head fracture dislocation [14]. Many recent studies have evaluated the functional outcome of Pipkin fracture dislocation using HHS as it has been validated to evaluate multiple hip pathologies [14, 24, 29]. If we consider THR as the endpoint of treatment, 20 (14.49%) patients ultimately needed this procedure, including 10 primary and 10 secondary procedures. The need for THR as primary and secondary intentions were more in our study compared to the available literature [6, 14].

There are a few limitations in this study. Being retrospective study few data might have lost. As the patients were recruited since 1997, some patients might not have received the current standard treatment regime. Despite the development of arthritis, few patients did not opt for arthroplasty, and hence a relatively poor outcome was inevitable. The strength of this study is that this is the largest series of femoral head fracture dislocation with more than one-year follow up having detailed information of the complications and clinical outcome.

To conclude, the incidence of hip osteonecrosis and the need for total hip replacement is increased when the reduction of femoral head fracture dislocations is delayed. Osteonecrosis in these patients is usually seen in Brumback 2A injuries and posterior based approaches. However, heterotopic ossification is not a common problem in the Indian subcontinent. A primary osteosynthesis of fracture must be attempted in Brumback 1B, 2 and 5 injuries and few type 1A injuries. However, total hip replacement should be the primary treatment for all Brumback 3B fracture dislocations in such delayed/ neglected cases. Femoral head fracture with infrafoveal involvement has good prognosis even with nonoperative treatment. The fractures involving suprafoveal femoral head and associated acetabular fracture have a worse prognosis. A careful selection of treatment plan in such delayed or neglected cases may provide a comparable outcome as that reported in the literature.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standard

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

References

- 1.Brav EA. Traumatic dislocation of the hip. Army experience and results over a twelve-year period. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1962;44:1115–1134. doi: 10.2106/00004623-196244060-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brumback RJ, Kenzora JE, Levitt LE, et al. Fractures of the femoral head. Hip. 1987;7:181–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler JE. Pipkin type-II fractures of the femoral head. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1981;63:1292–1296. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163080-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, Ganz K, Krügel N, Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2001;83(8):1119–1124. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B8.0831119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gavaskar AS, Tummala NC. Ganz surgical dislocation of the hip is a safe technique for operative treatment of pipkin fractures. Results of a prospective trial. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2015;29(12):544–548. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannoudis PV, Kontakis G, Christoforakis Z, Akula M, Tosounidis T, Koutras C. Management, complications and clinical results of femoral head fractures. Injury. 2009;40(12):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giordano V, Giordano M, Glória RC, et al. General principles for treatment of femoral head fractures. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(1):155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo JJ, Tang N, Yang HL, Qin L, Leung KS. Impact of surgical approach on postoperative heterotopic ossification and avascular necrosis in femoral head fractures: a systematic review. Internat Orthop. 2010;34(3):319–322. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 1969;51:737–755. doi: 10.2106/00004623-196951040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henle P, Kloen P, Siebenrock KA. Femoral head injuries: which treatment strategy can be recommended? Injury. 2007;38(4):478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hougaard K, Thomsen PB. Traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip-prognostic factors influencing the incidence of avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 1986;106:32–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00435649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellam P, Ostrum RF. Systematic review and meta-analysis of avascular necrosis and posttraumatic arthritis after traumatic hip dislocation. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2016;30(1):10–16. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kloen P, Siebenrock KA, Raaymakers ELFB, Marti RK, Ganz R. Femoral head fractures revisited. Eur J Trauma. 2002;28:221–233. doi: 10.1007/s00068-002-1173-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massè A, Aprato A, Alluto C, Favuto M, Ganz R. Surgical hip dislocation is a reliable approach for treatment of femoral head fractures. Clin Orthop Related Res. 2015;473(12):3744–3751. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4352-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ovre S, Sandvik L, Madsen JE, Roise O. Modification of the Harris hip score in acetabular fracture treatment. Injury. 2007;38:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park KH, Kim JW, Oh CW, Kim JW, Oh JK, Kyung HS. A treatment strategy to avoid iatrogenic Pipkin type III femoral head fracture-dislocations. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2016;136(8):1107–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips AM, Konchwalla A. The pathologic features and mechanism of traumatic dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Related Res. 2000;377:7–10. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pipkin G. Treatment of grade IV fracture-dislocation of the hip. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1957;39:1027–1042. doi: 10.2106/00004623-195739050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross JR, Gardner MJ. Femoral head fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5(3):199–205. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sahin V, Karakas ES, Aksu S, Atlihan D, Turk CY, Halici M. Traumatic dislocation and fracture dislocation of the hip: a long-term follow-up study. Journal of Trauma. 2003;54:520–529. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000020394.32496.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scolaro JA, Marecek G, Firoozabadi R, Krieg JC, Routt MLC. Management and radiographic outcomes of femoral head fractures. J Orthop Traumatol. 2017;18(3):235–241. doi: 10.1007/s10195-017-0445-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sen RK, Tripathy SK. Femoral head fracture. In: Goel SC, editor. ECAB Difficult hip fracture. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stannard JP, Harris HW, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Functional outcome of patients with femoral head fractures associated with hip dislocations. Clin Orthop Related Res. 2000;377:44–56. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200008000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stirma GA, Uliana CS, Valenza WR, Abagge M. Surgical treatment of femoral head fractures through previously controlled hip luxation: four case series and literature review. Rev Bras Ortop. 2018;53(3):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.rbo.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swiontkowski MF, Thorpe M, Seiler JG, Hansen ST. Operative management of displaced femoral head fractures: case-matched comparison of anterior versus posterior approaches for Pipkin I and Pipkin II fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 1992;6(4):437–442. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonetti J, Ruatti S, Lafontan V, Loubignac F, Chiron P, Sari-Ali H, Bonnevialle P. Is femoral head fracture-dislocation management improvable: a retrospective study in 110 cases? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(6):623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tosounidis T, Aderinto J, Giannoudis PV. Pipkin type-III fractures of the femoral head: fix it or replace it? Injury. 2017;48(11):2375–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tripathy SK, Das SS, Rana R, Jain M. Trochanteric osteotomy for safe surgical approach to bilateral hip dislocations with femoral head fractures. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(Suppl 4):S530–S533. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu X, Pang QJ, Chen XJ. Clinical results of femoral head fracture-dislocation treated according to the Pipkin classification. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33(3):650–653. doi: 10.12669/pjms.333.12633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue JJ, Wilber JH, Lipuma JP, Murthi A, Carter JR, Marcus RE, Valentz R. Posterior hip dislocations: a cadaveric angiographic study. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 1996;10:447–454. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]