Abstract

Metronidazole has been widely used topically and systemically for more than 50 years but data on its antioxidant properties are still incomplete, unclear and contradictory. Its antioxidant properties are primarily hypothesized based on in vivo results, therefore, studies have been performed to determine whether metronidazole has antioxidant activity in vitro. We used so-called global spectrophotometric and luminometric methods. Fe3+/Fe2+-reducing ability, hydrogen donor activity, hydroxyl radical scavenging property and lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity were investigated. Under the condition used, metronidazole has negligible iron-reducing ability and hydrogen donor activity. The hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity cannot be demonstrated. It acts as a pro-oxidant in the H2O2/.OH-microperoxidase-luminol system, but it can inhibit the induced lipid peroxidation. According to our results, metronidazole has not shown antioxidant activity in vitro but can affect redox homeostasis by a ROS-independent mechanism due to its non-direct antioxidant properties.

Keywords: Metronidazole, Lipid peroxidation inhibition, Hydrogen donor activity

Metronidazole; Lipid peroxidation inhibition; Hydrogen donor activity

1. Introduction

Metronidazole (MTZ, 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-methyl-5-nitroimidazole) is a bactericidal drug that is administered systemically and topically to various protozoa (Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Trichomonas vaginalis) against a wide variety of gram-negative (Bacteroides and Fusobacterium spp.) and gram-positive anaerobic bacteria (Peptostreptococcus and Clostridia spp.). It is effective in Helicobacter pylori infections, Crohn's disease (CD) [1], prevention of postoperative wound infections [2], and external application e.g. in rosacea, acne skin [3, 4]. Since its introduction in 1959 [5], clinical use has been steadily increasing and is now one of the most commonly used drugs and it is included in the World Health Organisation's core list of medicines [6].

Depending on its use, the absorption, utilization and metabolism of metronidazole vary [7]. In humans, it decomposes under aerobic conditions to two major metabolites, 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-hydroxymethyl-5-nitroimidazole and 1-acetic acid-2-methyl-5-nitroimidazole [8, 9].

Metronidazole is active against anaerobic organisms and converts to acetamide and N-(2-hydroxyethyl) oxamic acid [10]. Within the cell, its nitro group is reduced to hydroxylamine [11]. Several different enzymes participate in the reduction to form active metronidazole metabolites [12, 13, 14, 15] and several disorders can be observed in susceptible Giardia, e.g., protein disorder, DNA damage, and oxidative stress leading to cell death [16, 17]. Both metronidazole and its hydroxy metabolite are mutagenic to bacteria because they form base-pair substitutions [18, 19] and all effective against Trichomoniasis [20, 21].

To date, no reduced metabolites have been detected in human plasma and no DNA damage has been observed besides the application of metronidazole [22, 23]. Metronidazole is not considered carcinogenic, although some studies have found it may increase the risk of lung cancer [24, 25].

In vivo studies have suggested its antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties. Due to the putative antioxidant effect of MTZ, its effect is mediated by the inactivation of inflammatory mediators released by neutrophils (e.g., reactive oxygen species, IL-8) and reduction of oxidative stress [26, 27]. In the presence of neutrophils, it inhibits the formation of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals in a dose-dependent manner but it has no effects without neutrophils [28]. The reduction of oxidative stress has been observed in periodontitis when used as an antibiotic [29]. Metronidazole has beneficial effects in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) by reducing damaged proteins in the colon [30]. The use of metronidazole alone or in combination with ciprofloxacin in the treatment of Crohn's disease (CD) has a moderate beneficial effect [31]. Since recent data support that microbiota in the gut may participate in the pathogenesis of CD and colitis ulcerosa (CU), therefore, the application of metronidazole in perianal fistula can be favourable [31]. It significantly reduced the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) in the blood of burn victims [32].

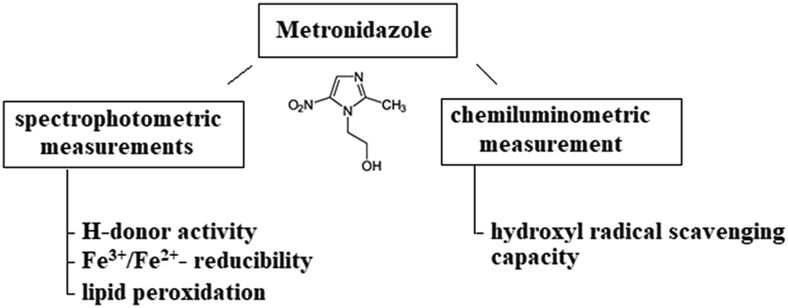

However, several in vivo studies have shown that metronidazole induces oxidative stress, at the same time other studies have shown that it does not cause oxidative damage in neurons and has no effect on reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, suggesting that metronidazole induces the neuronal cell death by a ROS-independent mechanism [33]. Metronidazole is a potent anti-inflammatory agent in vivo, but its mechanism of action has been mainly hypothesized in the literature [34]. There are only references to its antioxidant properties in vitro in the literature, and there is no evidence to date. Therefore, this work aimed to investigate the in vitro antioxidant, free radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation inhibitory properties of metronidazole by global methods. The experimental design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Protocol of global measurements of metronidazole antioxidant property.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Metronidazole of European Pharmacopoeia quality was provided by Aarti Drugs Limited (Mumbai, India). Ferrous sulphate heptahydrate, acetic acid, hydrochloric acid, sodium acetate and perchloric acid of analytical grade was purchased from Reanal (Budapest, Hungary). 2,4,6-tripyridyl-S-triazine (TPTZ), ascorbic acid, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazil (DPPH), hydrogen peroxide, luminol, microperoxidase and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd. We purchased malondialdehyde (MDA) in the form of diethyl acetate from Merck Ltd.

2.2. Measurement of ferric reducing ability

Fe3+/Fe2+-reducibility was determined spectrophotometrically at 593 nm by the modified FRAP (ferric reducing ability of plasma or plant) method of Benzie and Strain [35]. A calibration series was prepared from an aqueous solution of FeSO4∗7H2O for calibration. Composition of FRAP reagent: 25 ml acetate buffer (pH 3.6; 3.1 g sodium acetate∗3H2O and 16 ml acetic acid in 1000 ml buffer solution), 2.5 ml TPTZ solution (0.1559 g 4,6-tripyridyl-S -triazine (TPTZ) and 0.2 ml HCl in 50 ml water) and 2.5 ml FeCl3∗6H2O solution (0.2689 g FeCl3∗6H2O in 100 ml distilled water). The reaction mixture consists of 3 ml FRAP reagent and 10 μl sample solution [36].

2.3. Measurement of hydrogen donor activity

Hydrogen donor activity was determined according to the method of Blois modified by Hatano et al. [37, 38]. The DPPH compound binds hydrogen in the presence of hydrogen donor molecules, and thus its absorbance reduces. 4 ml sample solution was added to 1 ml DPPH solution (9 mg DPPH dissolved in 100 ml methanol). After thorough mixing, the reaction mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was read at 517 nm against methanol blanks. The degree of reduction (% inhibition) indicates hydrogen donor activity.

2.4. Determination of hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity

Hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity was determined in H2O2/.OH-microperoxidase-luminol system by the method of Blázovics et al. [39]. The resulting radicals excite the luminol present in the reaction mixture. Upon the excited molecule's return to the ground state, inactive aminophthalic acid is formed, while monochromatic light (λ = 425 nm) is emitted. The intensity of the light emitted is proportional to the amount of free radicals present in the system. In the presence of radical scavengers, the intensity of the measurable light decreases significantly depending on the molecule's radical scavenging capacity. The intensity of chemiluminescent light is expressed as RLU (relative light unit), which is the percentage of the total light emitted during the study period relative to the background intensity. The composition of the reaction mixture was as follows: 300 μl H2O2 (10−4 M), 300 μl microperoxidase (3 × 10−7 M), 50 μl luminol (7 × 10−7 M), 50 μl sample or bidistilled water. The total volume was 850 μl. A stock solution of 1 g/100 ml was prepared from metronidazole.

2.5. Measurement of lipid peroxidation inhibition

To determine the inhibition degree of lipid peroxidation, the method of Placer et al. was used with some modifications [40, 41]. In the acidic medium and heat-induced reaction MDA from the oxidative degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) form trimethine, which is a yellowish-red complex, which has an absorption maximum at 532–535 nm [42]. In choosing the temperature, we took into account that according to differential scanning calorimetric (DSC) and thermogravimetric (TG) studies, metronidazole melts at 160 °C and begins to decompose at 200 °C. Therefore, different amounts (0.25 ml, 0.5 ml and 1 ml) of a 1% metronidazole solution were heated in an oven at 150 °C for 10 min with 10 ml sunflower oil. Composition of TBA reagent: 20 ml perchloric acid of 70%, 120 ml deionized Millipore water, 0.75% supersaturated thiobarbituric acid solution. After centrifugation of the solution, 30 ml trichloroacetic acid (20%) was added to the supernatant TBA solution (10 ml). For the measurement, 0.5 ml sample was placed in 4.5 ml TBA reagent, covered and set in a 100 °C water bath for 30 min. After cooling, the clear solution was measured against the blank. Calibration was performed with malondialdehyde diethyl acetate. Lipid peroxidation inhibition is given by the percentage of mM MDA by the effect of metronidazole divided by mM MDA formed from sunflower oil.

2.6. Statistical calculations

Measurements were made in each case from three parallel samples, from which mean and standard deviation were calculated. One way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the significant differences using Statistica 12 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 in all cases.

3. Results

The Fe3+-reducibility of organic compounds can be determined in vitro by the FRAP method. For comparison and evaluation of the result, ascorbic acid was used as a standard since, at certain concentrations and conditions, it is an antioxidant with very good reducing ability [43]. Based on the results, ascorbic acid has good reducing power (37.59 μM at 105 μg/ml), while metronidazole did not reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+ in the concentration range of 100–500 μg MTZ/ml. By increasing the concentration of the active substance to 9 910 μg/ml, metronidazole showed a mild Fe3+-reducing ability (2.42 μM) in one hundred times the highest ascorbic acid concentration studied.

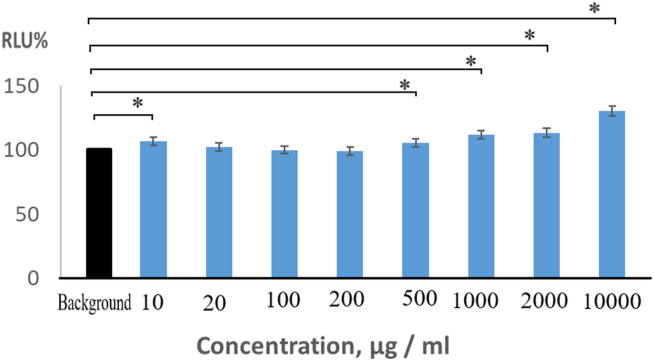

The results of hydrogen donor activity indicate that metronidazole has no significant hydrogen donor activity. DPPH stable free radical takes up H in the presence of H-donor molecules. But it seems metronidazole does not have an H-donor property. At the lowest concentration (10 μg MTZ/ml), the percentage inhibition is 4.99%, and the H-donor activity does not increase proportionally with the increasing concentrations. There was a small significant increase (p < 0.05) at 500 μg/ml (5.87%) and after this concentration, a significant decrease (p < 0.05) at 2000 μg/ml (3.99%) and 10000 mg/ml (3.76%) compared to the per cent inhibition at the lowest concentration (Figure 2). Despite the significant differences compared to the inhibitions value at the lowest concentration, the measured 4–6% inhibition is negligible from in hydrogen donor activity point of view since the significant hydrogen donor activity would be close to 100%. In our case, however, DPPH free radical appears to be stabilized in the presence of metronidazole and at higher concentrations.

Figure 2.

Hydrogen donor activity of metronidazole as a function of concentration. ∗Significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the inhibition % at the lowest concentration.

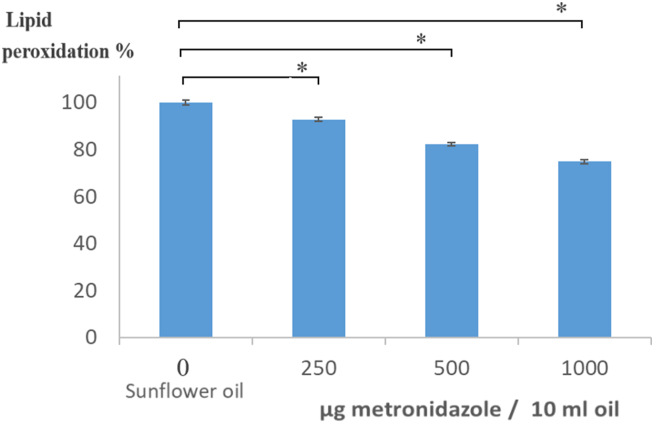

In the presence of a radical scavenger, in the H2O2/.OH-microperoxidase-luminol system, the intensity of the measurable light would be significantly reduced depending on the molecule's radical scavenging activity. However, metronidazole slightly increased the intensity of the emitted light. This shows that the metronidazole molecule does not have H2O2/.OH radical scavenging capacity, but excites the radicals slightly. We measured light intensities higher in the presence of metronidazole than the background intensity, which gave higher values than 100% in RLU (Figure 3), but significant differences (p < 0.05) were found only in the lowest (10 μg MTZ/ml with 106.7%) and the higher concentrations (>500 μg metronidazole/ml) because of the standard deviations. Above a concentration of 500 g MTZ/ml, the amount of induced free radicals increased continuously, the relative light unit reaches 105.5% at 500 g/ml, 111.9% at 1000 g/ml, 113.5% at 2000 μg/ml, and 130.5% at 10000 g/ml. Based on these measurements, metronidazole has a mild pro-oxidant property that increases above 500 g/ml.

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent hydroxyl radical generation of metronidazole in H2O2/□OH microperoxidase-luminol system (RLU: relative light unit). ∗Significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the background intensity.

The inhibition of lipid peroxidation was studied in the presence of sunflower oil. The metronidazole solution was able to reduce the concentration of malondialdehyde in the sunflower oil exposed to 150 °C for 10 min. Thus it was able to reduce the lipid peroxidation by 7.3%, 17.8% and 25.2% depending on the increasing concentration. The results obtained are values expressed as a percentage of the amount of MDA formed during the decomposition of sunflower oil, 92.7% at 250 g MTZ/ml, 92.25 at 500 g/ml and 74.8% at 1000 g/ml (Figure 4). The standard deviations were below one per cent in all cases, so the inhibition values of metronidazole compared to the sunflower oil were significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Lipid peroxidation inhibition of metronidazole. ∗Significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the lipid peroxidation value of sunflower oil.

4. Discussion

According to our results, metronidazole has only a weak ferric reducing ability and hydrogen donor activity, but it shows prooxidant behaviour in the H2O2/.OH-microperoxidase-luminol system. Similar in vitro studies have not been reported in the literature. Nevertheless, Trecy and Webster obtained hydroxyl radical scavenging ability when neutrophils were present in the system and without neutrophils, the compound showed no radical scavenging activity [44]. In vivo experiment without neutrophils, neither dose-dependence nor antioxidant effects were observed [28]. Andrioli et al. studied the toxicity of metronidazole on the roots of Allium cepa for 30 h. They found a significant increase in the antioxidant defence parameters attributed to metronidazole-induced oxidative stress [45]. Metronidazole applied against Trichomoniasis hydrogen peroxide, superoxide and nitrogen-free radicals were activated [20, 21]. These are consistent with our test results that metronidazole has prooxidant property. However, metabolites of metronidazole are also prooxidant in vivo, as metronidazole enters microorganisms to form toxic intermediates, free radicals (e.g. MTZ-NO2·-, MTZ- NO2·H, MTZ- NO, ONOO−, MTZ-NHOH), which cause DNA damage and trigger oxidative stress [12, 16, 22, 28, 29, 32, 33]. To the formation of active metronidazole metabolites, NADH oxidase, alcohol dehydrogenase, thioredoxin peroxidase, nitroreductase 1, nitroreductase 2, ferredoxin, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidoreductase are required [12, 13, 14, 15]. After activation, the formed MTZ-NO can react with superoxide to form more radical peroxynitrite (ONOO−), converted to nitrate [15]. In wastewater treatment, an H2O2-photocatalytic process is used to degrade metronidazole in the presence of zinc. Hydroxyl radicals formed in the aqueous medium decompose the organic molecules [46, 47, 48]. The process conditions are similar to those for measuring hydroxyl radical scavenging ability, except that iron microperoxidase is the catalyst in our method. Therefore, under these conditions used, metronidazole does not scavenge hydroxyl radicals but oxidizes itself to produce free radicals and then decomposes. During high-energy photocatalysis, metronidazole is degraded by NO2 release, while in vivo at low energy exposure it dissociates by NOOH release to form several intermediates [49]. These processes also support the prooxidant behaviour of metronidazole.

The result of inhibition of lipid peroxidation is consistent with the results obtained by Narayanan et al. [50] in a simple skin lipid model in which MDA concentrations were reduced by 25, 36, and 49% in the presence of 10, 100, and 500 μg metronidazole/ml, respectively. They concluded from previous experiments by themselves and others that the antioxidant effect of metronidazole can be mediated through two mechanisms: by reducing free radical production through neutrophil activity and by reducing free radical concentration due to its free radical scavenging property [21, 50]. Our studies did not confirm the free radical scavenging activity in vitro. However, we found moderate inhibition of lipid peroxidation. Therefore, questions arise as to why the results are so contradictory, why it inhibits lipid peroxidation, and why it does not have radical scavenging property. Rodrigez and Caseli recently reported that metronidazole interacts with phospholipids and depending on the chemical nature of lipid, the interaction is different [51], furthermore, metronidazole also interacts with the surface of DNA [17]. According to these, many side reactions are conceivable, in which metronidazole interacts with certain molecules to inhibit further lipid peroxidation.

5. Conclusion

The general antioxidant properties of metronidazole were not confirmed because even at high concentrations, it had only minimal iron-reducing ability and hydrogen-donor activity. Its hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity in the H2O2/.OH-microperoxidase-luminol system cannot be demonstrated either, as the compound behaved as a prooxidant. However, it was able to inhibit the induced lipid peroxidation based on in vitro studies.

We can say that depending on the use of metronidazole, in addition to its absorption, utilization and metabolism, its mechanism of action is also different. The compounds formed during metabolic degradation of MTZ may cause ambivalent behaviour in vivo. It can be stated that metronidazole does not reduce free radical processes as a direct antioxidant and has no radical scavenging nature in vitro. Rather, it reduces free radical reactions by killing the bacteria, reducing the inflammatory processes caused due to the bactericidal properties, and stopping the consequent "respiratory burst" defence mechanism in the body. Thus metronidazole can affect redox homeostasis by a ROS-independent mechanism due to its non-direct antioxidant properties.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Klára Szentmihályi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Krisztina Süle; Anna Egresi: Zoltán May: Performed the experiments.

Anna Blázovics: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Economic Development and Innovation Operation Program [grant number GINOP-2.2.1-15-2016-00023].

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Freeman C.D., Klutman N.E., Lamp K.C. Metronidazole. A therapeutic review and update. Drugs. 1997;4:679–708. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramasubbu D.A., Smith V., Hayden F., Cronin P. Systemic antibiotics for treating malignant wounds. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;24:CD011609. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011609.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson I.K., Rumsfield J.A., West D.P., Alexander J., Fischer J.H., Palouceket F.P. Evaluation of topical metronidazole gel in acne rosacea. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1987;21:346–351. doi: 10.1177/106002808702100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann C., Fock N., Franke G., Zsciesche M., Siegmund W. Comparative bioavailability of metronidazole formulations (Vagimid) after oral and vaginal administration. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;33:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosar C., Julou L. Activitiè de1’(hydroxy-2-ethyl)-1-methyl-2-nitro-5-imidazole (8.823R.P.) vis-a-vis des infections expérimentales à Trichomonas vaginalis. Ann. Inst. Pasteur. 1959;96:238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Essential drugs. WHO Drug Inf. 1999;13:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau A.H., Lam N.P., Piscitelli S.C., Wikes L., Danziger L.H. Clinical pharmakokinetics of metronidazole and other nitroimidazole anti-infectives. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1992;23:328–364. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199223050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amon I., Amon K., Hüller H. Pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy of metronidazole at different dosages. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1978;16:384–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loft S., Otton S.V., Lennard M.S., Tucker G.T., Poulsen H.E. Characterization of metronidazole metabolism by human liver microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1991;41:1127–1134. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90650-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch R.L., Beaulieu B.B., Chrystal E.J., Goldman P. A metronidazole metabolite in human urine and its risks. Science. 1981;211:398–400. doi: 10.1126/science.7221546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller M. Mode of action of metronidazole on anaerobic bacteria and protozoa. Surgery. 1983;93:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saghaug C.S., Klotz C., Kallio J.P., Brattbakk H.R., Stokowy T., Aebischer T., Kursula I., Langeland N., Hanevik K. Genetic variation in metronidazole metabolism and oxidative stress pathways in clinical Giardia lamblia assemblage A and B isolates. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019;12:1221–1235. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S177997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Löfmark S., Elund C., Nord C.E. Metronidazole is still the drug of choice for treatment of anaerobic infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50(Suppl.1):S16–S23. doi: 10.1086/647939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuelson J. Why metronidazole is active against both bacteria and parasites. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1533–1551. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upcroft P., Upcroft J.A. Drug targets and mechanisms of resistance in the anaerobic protozoa. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:150–164. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.1.150-164.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leitsch D., Schlosser S., Burgess A., Duchéne M. Nitroimidazole drugs vary in their mode of action in the human parasite Giardia lamblia. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs Drug Resist. 2012;2:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uzlikova M., Nohynkova E. The effect of metronidazole on the cell cycle and DNA in metronidazole-susceptible and -resistant Giardia cell lines. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2014;198:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Meo M., Vanelle P., Bernadini E., Laget M., Maldonado J., Jentzer O., Crozet M.P., Duménil G. Evaluation of the mutagenic and genotoxic activities of 48 nitroimidazoles and related imidazole derivatives by the Ames test and the SOS chromotest. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1992;19:167–181. doi: 10.1002/em.2850190212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raj D., Ghosh E., Mukherjee A.K., Nozaki O., Ganguly S. Differential gene expression in Giardia lamblia under oxidative stress: significance in eukaryotic evolution. Gene. 2014;535:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chacon M.O., Fonseca T.H.A., Oliveira S.B.V., Alacoque M.A., Franco L.L., Tagliati C.A., Cassali G.D., Campos-Mota G.P., Alves R.J., Capettini L.S.A., Gomes M.A. Chlorinated metronidazole as a promising alternative for treating trichomoniasis. Parasitol. Res. 2018;117:1333–1340. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-5813-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunne R.L., Dunne L.A., Upcroft P., O'Donoghue P.J., Upcroft J.A. Drug resistance in the sexually transmitted protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. Cell Res. 2003;13:239–249. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards D.I. Reduction of nitroimidazoles in vitro and DNA damage. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1986;35:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stambaugh J.E., Feo L.G., Manthei R.W. The isolation and identification of the urinary oxidative metabolites of metronidazole in man. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1968;161:373–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danielson D.A., Hannan M.T., Jick H. Metronidazole and cancer. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1982;247:2498–2499. doi: 10.1001/jama.1982.03320430022015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman G.D., Ury H.K. Initial screening for carcinogenicity of commonly used drugs. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1980;65:723–733. doi: 10.1093/jnci/65.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyachi Y., Imamura S., Niwa Y. Antioxidant action of metronidazole: a possible mechanism of action in rosacea. Br. J. Dermatol. 1986;114:231–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb02802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyachi Y. Potential antioxidant mechanism of action for metronidazole: implications for rosacea management. Adv. Ther. 2001;18:237–243. doi: 10.1007/BF02850193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akamatsu H., Oguchi M., Nishijima S., Takahashi M., Ushijima T., Niwa Y. The inhibition of free radical generation by human neutrophils through the synergistic effects of metronidazole with palmitoleic acid: a possible mechanism of action of metronidazole in rosacea and acne. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1990;282:449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00402621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boia S., Stratul S.T., Boariu M., Ursiniu S., Gotia S.L., Boia E.R., Borz C. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity and clinical assessment of patients with chronic periodontitis treated with nonsurgical periodontal therapy and adjunctive systemic antibiotherapy, Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018;59:1107–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pélissier M.A., Marteau P., Pochart P. Antioxidant effects of metronidazole in colonic tissue. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007;52:40–44. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nitzan O., Elias M., Peretz A., Saliba W. Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1078–1087. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao C.M., Ghosh A., Raghothama C., Bairy K.L. Does metronidazole reduce lipid peroxidation in burn injuries to promote healin? Burns. 2002;28:427–429. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao Y., Xiong T., Meng X., Yu D., Xiao Z., Song L. Different influences on mitochondrial function, oxidative stress and cytotoxicity of antibiotics on primary human neuron and cell lines. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2019;33 doi: 10.1002/jbt.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dingsdag S.A., Hunter N. Metronidazole: an update on metabolism, structure-cytotoxicity and resistance mechanisms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:265–279. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benzie I.E.F., Strain J.J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: direct measure of the total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Method Enzymol. 1999;299:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lado C., Then M., Varga I., Szőke É., Szentmihályi K. Antioxidant property of volatile oils determined by the ferric reducing ability. Z. Naturforsch. 2004;59c:354–358. doi: 10.1515/znc-2004-5-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blois M.S. Antioxidant determination by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;4617:1198–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatano T., Kagawa H., Yasuhara T., Okuda T. Two new flavonoids and other constituents in licore root: their relative astringency and radical scavenging effects. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988;36:2090–2097. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blázovics A., Sárdi É. Methodological repertoire development to study the effect of dietary supplementation in cancer therapy. Microchem. J. 2018;136:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma L., Liu G., Liu X. Amounts of malondialdehyde do not accurately represent the real oxidative level of all vegetable oils: a kinetic study of malondialdehyde formation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;54:412–423. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Placer Z.A., Cushman L.L., Johnson B.C. Estimation of product of lipid peroxidation (malonyl dialdehyde) in biochemical systems. Anal. Biochem. 1966;16:359–364. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(66)90167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeb A., Ullah F. A simple spectrophotometric method for the determination of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in fried fast foods. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/9412767. Article ID 9412767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Njus D., Kelley P.M., Tu Y.J., Schlegel H.B. Ascorbic acid: the chemistry underlying its antioxidant properties. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2020;159:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tracy J.W., Webster L.T., Jr. Drugs used in the chemotherapy of protozoal infections: trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, amebiasis, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, and other protozoal infections. In: Hardman J.G., Limbird L.E., Molinoff P.B., Gilman A., editors. Goodman and Gilman’s the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. ninth ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1996. pp. 987–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrioli N., Sabatini S.E., Mudry M.D., de Molina M.C.R. Oxidative damage and antioxidant response of Allium cepa meristematic and elongation cells exposed to metronidazole. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012;31:968–972. doi: 10.1002/etc.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dongshuo Z., Haon C., Kaiyin G. Preparation and visible-light photocatalytic degradation on metronidazole of Zn2SiO4-ZnO-biochar composites. J. Inorg. Mater. 2020;35:923–930. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang S., Wang P., Yang X., Wei G., Zhang W., Shan L. A novel advanced oxidation process to degrade organic pollutants in wastewater: microwave-activated persulfate oxidation. J. Environ. Sci. 2009;21:1175–1180. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(08)62399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ta N., Hong J., Liu T., Sun C. Degradation of atrazine by microwave-assisted electrodeless discharge mercury lamp in aqueous solution. J. Hazard Mater. 2006;138:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmadi S., Osagie C., Rahdar S., Khan N.A., Ahmed S., Hajini H. Efficacy of persulfate-based advanced oxidation process (US/PS/Fe3O4) for ciprofoxacin removal from aqueous solutions. App. Water Sci. 2020;10:187. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Narayanan S., Hünerbein A., Getie M., Jäckel A., Neubert R.H.H. Scavenging properties of metronidazole on free oxygen radicals in a skin lipid model system. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007;59:1125–1130. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.8.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Itälä E., Niskanen J., Pihlava L., Kukk E. Fragmentation patterns of radiosensitizers metronidazole and nimorazole upon valence ionization. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2020;124:5555–5562. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.0c03045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.