Abstract

For implementation of an evidence-based program to be effective, efficient, and equitable across diverse populations, we propose that researchers adopt a systems approach that is often absent in efficacy studies. To this end, we describe how a computer-based monitoring system can support the delivery of New Beginnings Program (NBP) a parent-focused evidence-based prevention program for divorcing parents. We present NBP from a novel systems approach that incorporates social system informatics and engineering, both necessary when utilizing feedback loops, ubiquitous in implementation research and practice. Examples of two methodological challenges are presented: how to monitor implementation, and how to provide feedback by evaluating system-level changes due to implementation. We introduce and relate systems concepts to these two methodologic issues that are at the center of implementation methods. We explore how these system-level feedback loops address effectiveness, efficiency, and equity principles. These key principles are provided for designing an automated, low-burden, low-intrusive measurement system to aid fidelity monitoring and feedback that can be used in practice. As the COVID-19 pandemic now demands fewer face-to-face delivery systems, their replacement with more virtual systems for parent training interventions requires constructing new implementation measurement systems based on social system informatics approaches. These approaches include the automatic monitoring of quality and fidelity in parent training interventions. Finally, we present parallels of producing generalizable and local knowledge bridging systems science and engineering method. This comparison improves our understanding of system-level changes, facilitate a program’s implementation, and produce knowledge for the field.

Keywords: social systems informatics, implementation science, implementation practice, systems science, systems engineering, computational linguistics, fidelity, parenting programs

Introduction

To improve population’s health requires a directed, systematic, and expedited approach to ensure that evidence-based programs (EBPs) are delivered with a high fidelity at scale. Scientists have built most of our research methods around clinical and group-based trials [e.g., the CONSORT Statement (Begg et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2008; Gottfredson et al., 2015; Schulz et al., 2010)], but neither efficacy nor effectiveness trials have focused systematically on issues that are critical for implementation of EBPs in real-world settings. The methods of Implementation Science, which addresses issues concerning adaptation (Chambers & Norton, 2016), scaling up and scaling out (Aarons et al., 2017), and sustaining (Palinkas et al., 2020; Spear et al., 2018) efficacious/effective programs, differ dramatically by explicitly or implicitly addressing complex systems (Berkel et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2017; Czaja et al., 2016; Landsverk et al., 2018; Lich et al., 2013; Palinkas et al., 2011). However, Implementation Science as a field remains in its infancy, and theories and frameworks require further development (Damschroder et al., 2009; Gottfredson et al., 2015; Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2009; Nilsen, 2015; Sales, 2018; Skolarus et al., 2017; Smith, 2017; Spoth et al., 2013).

Our main premise is that “social systems informatics” (SSI) can help deliver, monitor, evaluate, and ultimately improve the large-scale implementation of EBPs in community-based organizations. Defining the components of social systems informatics (Brown et al., 2013), the word “social” places an emphasis on interactions with others (e.g., parents and children), “systems” comprise distinct, but interacting components or subsystems as well as loosely connected systems (e.g., service setting and researchers), and “informatics” refers to the science of gathering, storing, processing and using implementation data (e.g., fidelity, quality, attendance, homework). Thus, SSI pertains not only to measurement of interacting components, but also to feedback among them for decision making at several stages of implementation. SSI facilitates the collection of data through low burden, automated, or unobtrusive measures (Webb et al., 1999) involving machine coding of digitized information (Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015) and analyses from machine learning algorithms (Bickman, 2020; Brown, 2020). At a minimum, the system includes the program itself, its delivery system, and the broader environmental context, each of which affect one another (Chambers et al., 2013; Mabry & Kaplan, 2013). Studying each component separately produces an incomplete picture. By bringing a systems perspective of interacting components into implementation science, it becomes possible to identify how components can work together to achieve successful EBP implementation.

This paper calls for a redesign of how we implement, monitor, and evaluate EBPs as they are delivered at scale. Two SSI innovations are introduced in this paper; the first is a systems approach using feedback loops between Inputs, Processes, Outputs and Outcomes; the second is the use of automated and low burden measurement systems. These approaches are illustrated using the New Beginnings Program (NBP) (Sandler et al., 2016; Wolchik et al., 2007; Wolchik et al., 2002; Wolchik et al., 2013) as well as other prevention programs.

New Beginnings Program

NBP is a manualized, group-format program that targets parenting skills to improve child adjustment following parental divorce (Wolchik et al., 2007). Two efficacy trials conducted in the context of a university-based research center have establised the long-term efficacy of NBP in improving parenting and reducing rates of mental health and substance use diagnoses for children (Wolchik et al., 2013; Wolchik et al., 2000). NBP is cost-effective based on reductions in contact with the criminal justice system and mental health services fifteen years after exposure to the program (Herman et al., 2015).

Each of the 10 program sessions teaches new parenting skills in one of four domains: positive parent-child relationships, communication, positive discipline, and shielding children from interparental conflict. Facilitators coach parents on the use of skills in each session, and parents are given homework to practice the skills with their children between sessions. Previous studies have demonstrated support for NBP’s process theory that home practice is the primary active ingredient leading to change (Berkel, Sandler, et al., 2018), and that fidelity to the content of the program and the quality of facilitators’ process skills are important for ensuring competent home practice (Berkel, Mauricio, et al., 2018). We have also previously described the variability in implementation when NBP was delivered by community agencies as well as challenges involved in feasible and valid methods to monitor and support implementation in community settings (Berkel et al., 2019).

Based on positive results of the efficacy trials, we developed a partnership with four county-level family courts and community-based mental health service agencies to conduct an effectiveness trial of NBP (Sandler et al., 2016). From a public health perspective, the courts are an ideal collaborating agency because they have access to the full population of parents who were married and are divorcing. Because courts do not have the mission or infrastructure to deliver NBP, family-focused agencies represent a second organizational partner. The role of the researchers in this service system is to train providers to implement the program with a high degree of fidelity and quality. Significant challenges in achieving this goal involve developing an effective and efficient system of training and supervision that is feasible in real-world settings and developing measures of implementation that are feasible to collect and predictive of program impact.

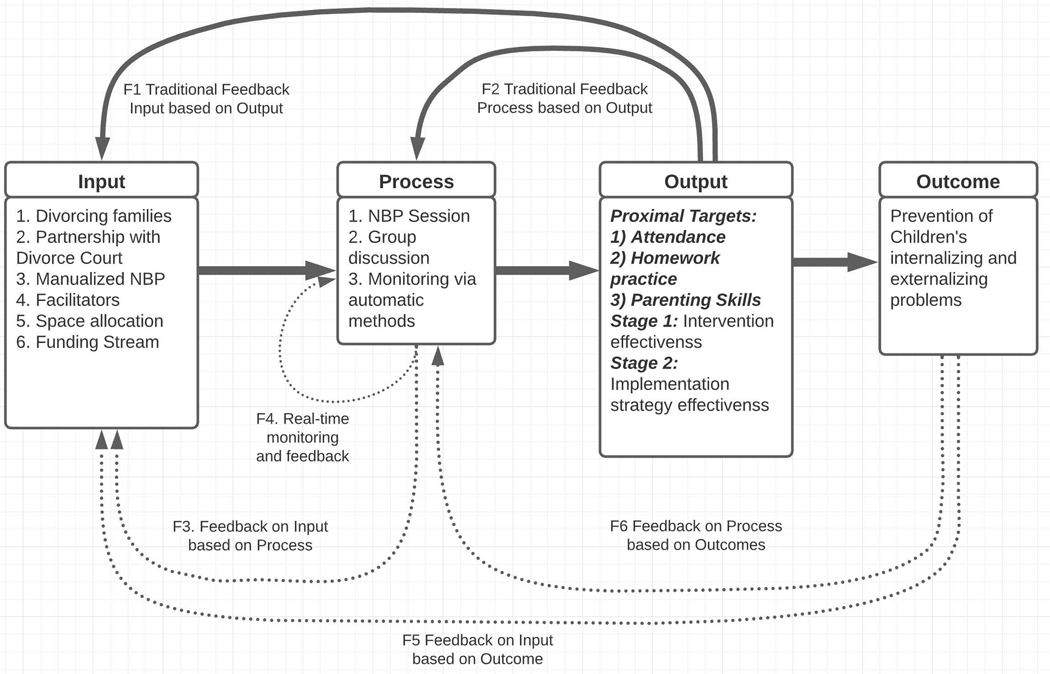

Inputs, Processes, Outputs, Outcomes and their Feedback Loops

A system’s view of implementation includes a focus on inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes that permits a complete start-to-finish perspective on how best to structure, sequence, and measure activities to reach outcomes (Davenport et al., 1996). Figure 1 displays these four elements and provides examples of each that are pertinent to NBP. Implementation inputs include resources available (e.g., Facilitators, Space Allocation, and Funding Stream). Processes include training and supervision as well as program delivery (e.g., NBP session, and NBP group discussion). Outputs include homework activities and parenting skills. Finally, Outcomes include long-term mental health of children (e.g., internalizing and externalizing problems). Feedback loops are used to monitor and direct where system change is needed. For example, if the outcome of participant absenteeism is high, one way to increase the number of clients receiving a full dose of NBP is to revise the process; e.g., expand make-up opportunities for missed NBP sessions. This change could invoke another feedback loop from process to input if make-up sessions require more staffing. Below we describe each feedback loop and provide examples from NBP and other prevention systems in use today.

Figure 1.

Four Feedback Mechanisms involving Inputs, Processes, Outputs, and Outcomes

Types of Feedback Loops and their Functioning

Here we present six types of feedback loops that vary in their focus on effectiveness, efficacy, and equity. The Traditional Feedback Loop in a system involves modifying the Input based on Output, as shown in the topmost loop in the Input-Process-Output diagram in Figure 1 (F1). An example of this feedback loop is using the number of participants reached as Output, and the number of people hired to deliver the EBP as Input. If this Output is too small, we may consider increasing reach by hiring more people to deliver the program. Similarly, equity in delivering health services may be increased by adding resources to recruit in underserved communities.

A second common feedback loop in systems ties the Outcomes back to Process, which we have labeled F2. For example, if attendance toward the end of an EBP is low, we can consider redesigning Processes for client engagement, tracking, reminders, and/or efficiency in the delivery of the intervention.

The feedback loop of F3 Process to Input would lead to immediate revision of resources when the Process is not functioning as expected. For example, delays in analyzing the fidelity of the NBP delivery may be corrected by providing more data system infrastructure. The feedback loop F4 involving self-feedback of Process involves a self-corrective system. This would include recoding of reports so that they are more informative. A Process can be monitored to become more efficient, e.g., faster or more economical in converting Input into Output. As an example, the Community Anti-Drug Coalition of America’s (CADCA) seven strategies for community change (Paine-Andrews et al., 2002) centers on coalition building as a key change process by monitoring and improving the coalition (Yang et al., 2012).

The bottom most loops connect Outcome (e.g., a population prevalence of a condition -- rather than a traditional Output measure) to both Input and Process (F5 and F6). Such feedback loops are inherent in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse Prevention’s (CSAP) five-stage, Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) (Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, 2009) which proposes that decision making about prevention is based on Outcomes, e.g., levels of youth substance abuse in local communities. In this approach, the ultimate test is whether substance abuse decreases in a community. If not, then the entire strategy is examined for improvement, including its Inputs and Processes. Such a system is designed to improve health effectiveness, and SAMHSA’s explicit focus on cultural competence throughout the SPF process emphasizes health equity as well.

These six feedback loops illustrate possible variations in evaluating implementation. Some feedback systems are designed primarily for efficiency, such as the self-monitoring and correcting loop, while others naturally emphasize effectiveness over efficiency such as feedback on low quality of NBP homework leading to increased supervision. It is quite possible to monitor any one or a combination of these feedback loops in practice with a non-randomized design, to test how efficient, effective, and equitable it performs within a specified context.

Innovative Measurement Systems for Implementation

This re-engineered approach to improving output depends on our ability to feasibly and accurately collect data on inputs, processes, and outputs. Standard approaches to collecting data in community settings have been limited to simple process or output measures (e.g., number of participants attending). We will discuss technology-based innovations (e.g., machine learning, computerized adaptive testing) that can support comprehensive data collection necessary to improve delivery and outcomes (Gibbons & deGruy, 2019).

Implementation measurement can be classified in terms of system inputs (e.g., financial and workforce resources provided), processes (e.g., the training sub-system), and output (e.g., quality of program delivery, how well parents completed homework), which are conceptually linked to outcomes. All are important to monitor, but only with feedback loops can the system provide opportunities for improvement. We focus on measuring two dimensions of fidelity to the program, the amount of program content covered and quality or skill with which the content is delivered (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). A provider who reads a manual word-for-word demonstrates high fidelity to content, but low skill (Berkel et al., 2019).

Declines in implementation fidelity are considered a major cause of the observed drop off in participant outcomes when programs go to scale (Chambers et al., 2013; Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015; Schoenwald et al., 2008). Thus, efficient monitoring and feedback of fidelity is critical for improving implementation. Currently, the fidelity feedback system used in nearly all EBPs has four important limitations: traditional feedback is costly, delayed, static, and based on a limited number of sessions. It is costly because it requires highly trained observers, there is a delay between when a session is delivered and when it is rated, and it is static since it cannot provide real-time feedback. These limitations often make providing fidelity feedback unfeasible for community agencies.

SSI provides methods for conducting implementation assessments, improving the reliability of assessments, and enabling rapid feedback to support sustained, high quality implementation. Recent work on machine learning demonstrates the ability to improve mental health services (Bickman, 2020) and to predict program sustainability with high levels of accuracy relative to human coding (Gallo et al., 2020). Other examples of innovative, automated methods include the recognition of stages of implementation through text mining (Wang et al., 2016), recognition of verbal discordance through image processing of gestures (Inoue et al., 2010; Inoue et al., 2012), measurement of therapeutic alliance through computational linguistics (Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015), and identification of motivational interviewing through topic modeling (Atkins et al., 2014). These computational methods will become even more essential as we move towards virtual delivery of programs due to COVID-19 pandemic. The recording of materials, dedicated and individualized camera and microphone recordings for each participant will create more digital data exploitable for computational methods.

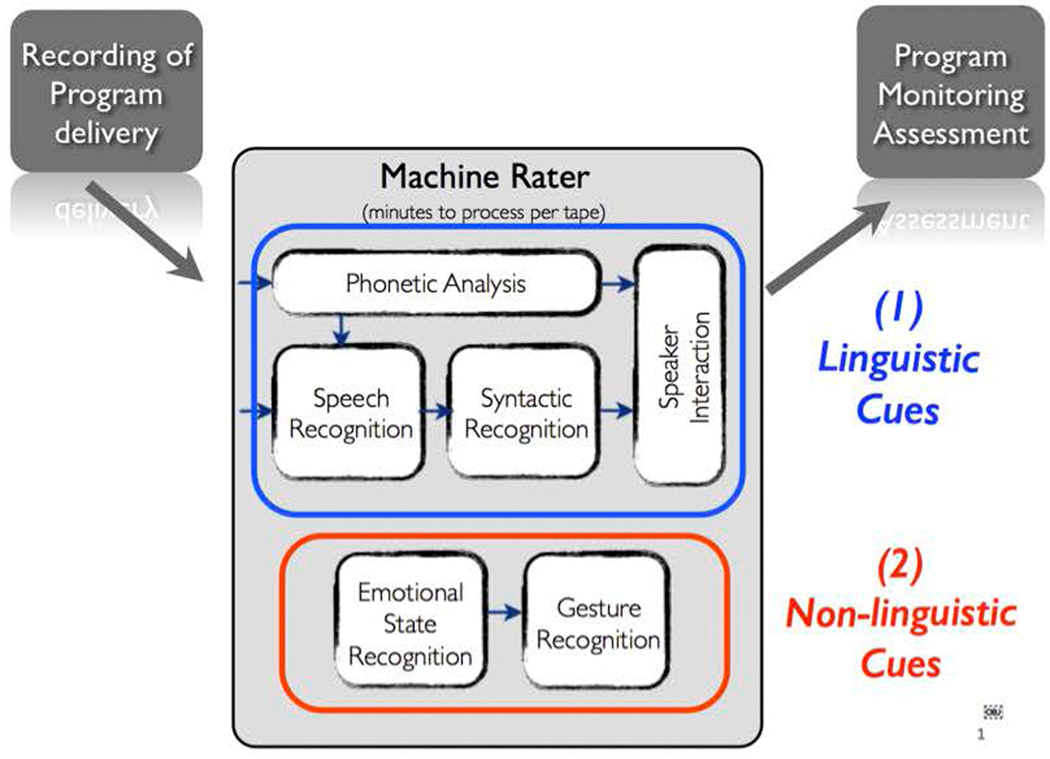

Moving from human rater to machine rater system to assess fidelity and quality of implementation.

The development of reliable and valid indices of implementation provides the foundation for developing a monitoring and feedback automated system. Methods from computational linguistics can be used for efficient monitoring. For instance, Educational Testing Services (ETS) use advanced computational linguistic methods to automatically score student essays for the GRE, GMAT, and SAT (Burstein et al., 2013; Kakkonen et al., 2005). Linguistic indicators of quality are mined from a database of essays previously scored by human experts. For monitoring implementation, a number of researchers have focused their attention on the assessment of fidelity and quality (Atkins et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2013; Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015). Our own research group has provided a proof of concept for automatic fidelity coding for a preventive parent training intervention in a bilingual context that targeted drug abuse and sexual risk behavior (Brown et al., 2013; Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015). Another research team (Atkins et al., 2014) focused on treatment of mental health problems using motivational interviewing. Both approaches extracted linguistic indicators of fidelity at the sentence level (Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015), and topic identification at the word level (Atkins et al., 2014). Figure 2 shows a conceptual model on how a machine rater can monitor program delivery. There are two types of cues that can be monitored through computational methods: linguistic and non-linguistic cues as shown in Figure 2. As an example of linguistic cues, in Familias Unidas -- another parent-focused intervention (Pantin et al., 2007)-- a computational linguistic method estimates the parent’s level of engagement by tracking the type and number of questions asked during the sessions (Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015). In that study, the machine learning algorithm achieved high Kappa scores (.83) when compared with human recognition. Non-linguistic cues include the recognition of tone of voice or gestures (Bozkurt et al., 2009; Gallo, Berkel, et al., 2015; Inoue et al., 2012). This less explored source of information offers the opportunity to expand the feedback and monitoring regardless of the language being used to deliver the program.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model on how a machine rater can monitor program delivery

To illustrate an element of the automated system for NBP proposed by Gallo et al. (2016), consider identifying linguistic patterns that are coded as “indicated belief,” -- one of the indicators of quality. Indicated Belief in the parent’s ability of learning the material includes such statements as, “You guys learned this material very well” or “I’m confident you will master this program.” We mined these relevant linguistic cues based on the qualitative coding of the transcripts to automatically assess normalizing in a session. Using positive and negative examples of “Indicated Belief” we trained two machine learning algorithms (Support Vector Machine (Tong & Koller, 2001) and K-nearest neighbor (Sebastiani, 2002)) and achieved a high accuracy of 94% compared to human raters (Gallo et al., 2016). This pilot data suggests that aspects of quality can be tracked by text mining and machine-based methods, in 100% of the sessions, cheaply, and faster than human observation.

Next Generation Implementation of the New Beginnings Program Viewed from a Systems Perspective

We now apply our SSI perspectives to the NBP in three specific areas, (Wolchik et al., 2007). NBP was designed based on a theory that the program will strengthen parenting, which in turn will lead to improved child outcomes. In delivering the program, providers can deliver the content true to the manual (i.e., program fidelity) or leave out manualized material. They may connect with and motivate participants and deliver the program in a clear and coherent way or in a less engaging way. Participants can attend the sessions, engage with providers and other parents, and incorporate what they learn in the program into their daily lives or not (i.e., participant responsiveness). Parents are taught “Home Practice is the Program” and provided parenting skills each week in a group setting. Thus, home practice is an element of responsiveness that is of primary theoretical importance (Wolchik et al., 2007). With fidelity, quality, and participant responsiveness being directly linked to targeted program outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008), this becomes our mediational model (Berkel et al., 2011).

The predictive validity of different measures of implementation was tested with the proximal outcomes. Measures of responsiveness, parent ratings of home practice efficacy and provider ratings of parents’ competence in completing the home practice assignments, predicted improvement in parenting above and beyond attendance (Berkel, Sandler, et al., 2018). Therefore, these two Output measures would be useful measures for monitoring implementation in real-world settings. In addition, independent observers’ ratings of provider’s quality of delivery at a given session predicted each of these responsiveness indicators at the following session, making these ratings important for Process monitoring (Berkel et al., 2015; Berkel et al., 2016; Berkel, Sandler, et al., 2018).

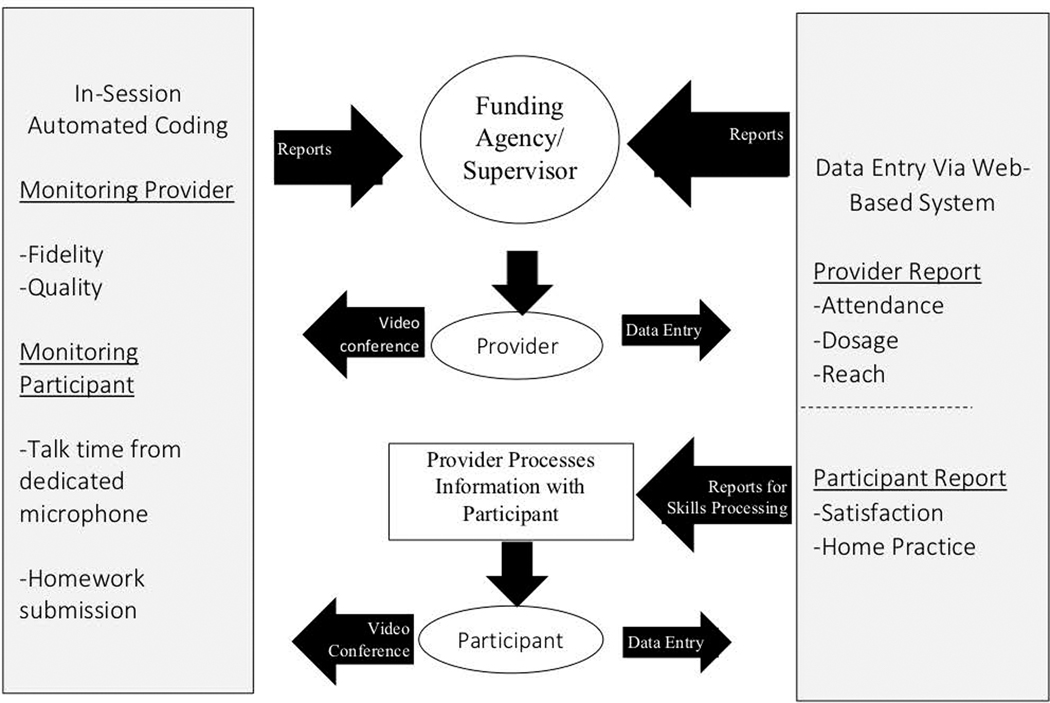

A full implementation monitoring and feedback system would have two types of inputs: in-session information collected during a session and web-based data entry for those that occur outside of program sessions or that are not audio-based (see Figure 3). Providers’ audio signals can be captured and scored for their fidelity to the manual and quality of delivery, then provided as feedback for supervision (Atkins et al., 2014; Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015). Participants’ audio signals would be captured from the session and scored for their active participation in the session. The data from these sources would provide feedback to both participants and providers to strengthen their effective use of the program.

Figure 3.

Dynamic Implementation Monitoring and Feedback System Using Empirically Supported Indicators of Implementation

Discussion

This paper presents the benefit of using a social system informatics perspective for monitoring and feedback at different stages of implementation, as applied to a parent-focused prevention program for divorced parents. An SSI perspective can improve the delivery of evidence-based programs in communities and service delivery organizations (Atkins et al., 2014; Gallo, Pantin, et al., 2015). At its core, this involves the development and integration of a low-burden measurement system that is actionable and sustainable by the service delivery organization or community.

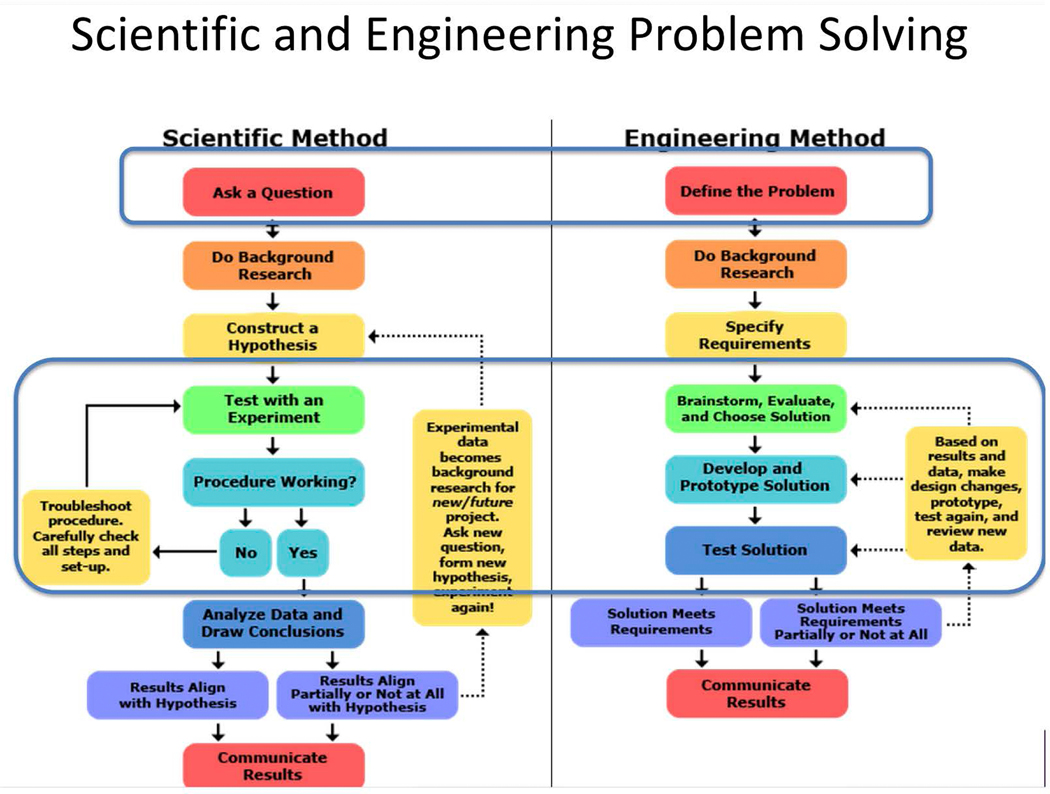

Social system informatics subsumes principles from systems engineering which aims to provide rapid feedback for problem solving (Figure 4). Systems engineering deviates from the rigid scientific method which currently guides typical effectiveness and efficacy trials. A single feedback loop in the scientific method uses the conclusions (output) to inform the hypothesis being testing (input) in subsequent trials. This delays the system response to new contexts that can make parts of the trial obsolete, say when COVID-19 necessitates virtual sessions. The engineering method, on the other hand, uses multiple feedback loops at several stages of an implementation trial which are used to create a solution, develop a prototype, and test it an interactive fashion.

Figure 4.

Comparison between the scientific and engineering problem solving

In this paper, we proposed a redesign of fundamental components of the NBP to illustrate how this social systems informatics approach would work. We suggested innovative methods for measuring fidelity, quality, and adaptation of an intervention’s delivery that are built on automatic, computer-based, low cost, strategies. For automated measures of responsiveness this included attendance and homework completion. Feedback offers rapid and efficient measurements around key implementation phases. We also noted distinct types of feedback systems involving short and long-term loops. Formal testing of full implementation strategies or smaller implementation components such as feedback subsystems may be accomplished by using randomized implementation trials or non-randomized evaluations.

An automatic computer-based fidelity assessment can potentially be a more reliable than human observers. Computer-based assessments avoid “halo” effects that may occur when a provider does well in quality but not so well on content delivery. Yet, more research is needed to assess the validity of computer-based fidelity methods when compared with human-based assessments. To assess fidelity and quality, we are currently extending computational linguistic methods developed for other parent-training intervention programs (Berkel et al., 2019; Gallo et al., 2016).

In general, the proposed system level and computational methods should be integrated with traditional methods. In this way, we utilize the best skills from human effort and the best skills from automated methods. For instance, a measuring method can be improved when a fast computer-based instrument is used at the first stage to assess the overall implementation fidelity, then followed by a high-quality human-based instrument for stages of implementation that are inherently unable to be operationalized by computer. This two-stage measuring method can lower the burden of local agencies when implementing EBPs. The implementation of parent training programs as well as other EBPs can benefit from these methods to enable efficient, effective and equitable delivery of these programs as they are rolled out and sustained over time.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out through the support of grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), DA033991-03 (Berkel & Mauricio MPI), and diversity supplement DA033991-03S1 (Gallo) and the Center for Prevention and Implementation Methodology for Drug Abuse and HIV (CePIM) (P30 DA027828 Brown PI )

References

- Aarons GA, Sklar M, Mustanski B, Benbow N, & Brown CH (2017, Sep 6). “Scaling-out” evidence-based interventions to new populations or new health care delivery systems [journal article]. Implementation Science, 12(1), 111. 10.1186/s13012-017-0640-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Steyvers M, Imel ZE, & Smyth P. (2014). Scaling up the evaluation of psychotherapy: evaluating motivational interviewing fidelity via statistical text classification. Implementation Science, 9, 49. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, Pitkin R, Rennie D, Schulz KF, Simel D, & Stroup DF (1996, Aug 28). Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. Jama, 276(8), 637–639. 10.1001/jama.1996.03540080059030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Gallo CG, Sandler IN, Brown CH, Wolchik S, & Mauricio AM (2015, December 15, 2015). Identifying indicators of implementation quality for computer-based ratings 8th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation, Washington, DC. https://academyhealth.confex.com/academyhealth/2015di/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/7432 [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Gallo CG, Sandler IN, Mauricio AM, Smith JD, & Brown CH (2019, Feb). Redesigning Implementation Measurement for Monitoring and Quality Improvement in Community Delivery Settings. Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(1), 111–127. 10.1007/s10935-018-00534-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Sandler IN, Wolchik S, Brown CH, Gallo CG, & Tein J-Y (2016, June). Dimensions of Implementation As Predictors of Effects of New Beginnings Program. In Sandler I, Mulit-court effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program for divorcing parents Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Gallo CG, & Brown CH (2018, Aug). The Cascading Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Implementation on Program Outcomes: a Test of a Theoretical Model. Prev Sci, 19(6), 782–794. 10.1007/s11121-017-0855-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, & Sandler IN (2011, Mar). Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science, 12(1), 23–33. 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Brown CH, Gallo CG, Chiapa A, Mauricio AM, & Jones S. (2018, Jul). “Home Practice Is the Program”: Parents’ practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the New Beginnings Program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 19(5), 663–673. 10.1007/s11121-016-0738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. (2020). Improving Mental Health Services: A 50‑Year Journey from Randomized Experiments to Artificial Intelligence and Precision Mental Health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47, 795–843. https://rdcu.be/b58rN [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt E, Erzin E, Erdem CE, & Erdem AT (2009, September 6–10, 2009). Improving automatic emotion recognition from speech signals INTERSPEECH, Brighton, UK. http://www.iscaspeech.org/archive/interspeech_2009/i09_0324.html [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH (2020). Three Flavorings for a Soup to Cure What Ails Mental Health Services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, Collins LM, Duan N, Mittman BS, Wallace A, Tabak RG, Ducharme L, Chambers DA, Neta G, Wiley T, Landsverk J, Cheung K, & Cruden G. (2017, Mar 20). An Overview of Research and Evaluation Designs for Dissemination and Implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 38(38), 1–22. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Mohr DC, Gallo CG, Mader C, Palinkas LA, Wingood G, Prado G, Kellam SG, Pantin H, Poduska J, Gibbons R, McManus J, Ogihara M, Valente T, Wulczyn F, Czaja S, Sutcliffe G, Villamar J, & Jacobs C. (2013, Jun 1, 2013). A computational future for preventing HIV in minority communities: How advanced technology can improve implementation of effective programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63(Suppl 1), S72–S84. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829372bd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Wang W, Kellam SG, Muthén BO, Petras H, Toyinbo P, Poduska J, Ialongo N, Wyman PA, Chamberlain P, Sloboda Z, MacKinnon DP, Windham A, & Prevention Science and Methodology Group. (2008, Jun 1). Methods for testing theory and evaluating impact in randomized field trials: Intent-to-treat analyses for integrating the perspectives of person, place, and time. Drug and alcohol dependence, 95(Suppl 1), S74–S104. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein J, Tetreault J, & Madnani N. (2013). The E-rater automated essay scoring system. In Shermis MD & Burstein J. (Eds.), Handbook of automated essay evaluation: Current applications and new directions (pp. 55–67). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. (2009). Identifying and Selecting Evidence-Based Interventions Revised Guidance Document for the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentive Grant Program (HHS Pub. No. (SMA)09–4205). http://store.samhsa.gov/product/SMA09-4205

- Chambers DA, Glasgow R, & Stange K. (2013, Oct 2). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8, 117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, & Norton WE (2016, Oct). The Adaptome: Advancing the science of intervention adaptation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4 Suppl 2), S124–131. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Valente TW, Nair SN, Villamar J, & Brown CH (2016). Characterizing implementation strategies using a systems engineering survey and interview tool: A comparison across 10 prevention programs for drug abuse and HIV sexual risk behaviors. Implementation Science, 11, 70. 10.1186/s13012-016-0433-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009, Aug 7). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport TH, Jarvenpaa SL, & Beers MC (1996). Improving knowledge work processes. MIT Sloan Management Review, 37(4), 53. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J, & DuPre E. (2008, Jun). Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Abram K, Hannah N, Canton L, McGovern M, & Brown CH (2020). Assessing Sustainability in States’ Response to the Opioid Crisis. Submitted for Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gallo CG, Berkel C, Sandler IN, & Brown CH (2015). Improving implementation of behavioral interventions by monitoring quality of delivery in speech. Conference on the Science of Dissemination & Implementation. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Berkel C, Sandler IN, & Brown CH (2016, June). Developing Computer-Based Methods for Assessing Quality of Implementation in Parent-Training Behavioral Interventions. Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo CG, Pantin H, Villamar J, Prado GJ, Tapia M, Ogihara M, Cruden G, & Brown CH (2015, Sep). Blending Qualitative and Computational Linguistics Methods for Fidelity Assessment: Experience with the Familias Unidas Preventive Intervention. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 574–585. 10.1007/s10488-014-0538-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, & deGruy FV (2019). Without Wasting a Word: Extreme Improvements in Efficiency and Accuracy Using Computerized Adaptive Testing for Mental Health Disorders (CAT-MH). Current psychiatry reports, 21(8), 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Cook TD, Gardner FEM, Gorman-Smith D, Howe GW, Sandler IN, & Zafft KM (2015, Oct). Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: Next generation. Prevention Science, 16(7), 893–926. 10.1007/s11121-015-0555-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman PM, Mahrer NE, Wolchik SA, Porter MM, Jones S, & Sandler IN (2015, May). Cost-benefit analysis of a preventive intervention for divorced families: reduction in mental health and justice system service use costs 15 years later. Prevention Science, 16(4), 586–596. 10.1007/s11121-014-0527-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Ogihara M, Hanada R, & Furuyama N. (2010). Utility of gestural cues in indexing semantic miscommunication. 2010 5th International Conference on Future Information Technology, [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Ogihara M, Hanada R, & Furuyama N. (2012, Nov 1). Gestural cue analysis in automated semantic miscommunication annotation. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 61(1), 7–20. 10.1007/s11042-010-0701-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, & National Research Council. (2009). Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkonen T, Myller N, Timonen J, & Sutinen E. (2005). Automatic essay grading with probabilistic latent semantic analysis Second Workshop on Building Educational Applications Using NLP, https://aclweb.org/anthology/W/W05/W05-0200.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk J, Brown CH, Smith JD, Chamberlain P, Curran GM, Palinkas L, Ogihara M, Czaja S, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Vermeer W, Saldana L, Rolls Reutz JA, & Horwitz SM (2018). Design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In Brownson RC, Colditz GA, & Proctor EK (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice, Second Edition (pp. 201–228). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lich KH, Ginexi EM, Osgood ND, & Mabry PL (2013). A call to address complexity in prevention science research. Prevention Science, 14(3), 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry PL, & Kaplan RM (2013). Systems Science: A Good Investment for the Public’s Health. Health Education & Behavior, 40(1_suppl), 9S–12S. 10.1177/1090198113503469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(53). 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine-Andrews A, Fisher JL, Patton JB, Fawcett SB, Williams EL, Lewis RK, & Harris KJ (2002, Apr). Analyzing the contribution of community change to population health outcomes in an adolescent pregnancy prevention initiative. Health Education & Behavior, 29(2), 183–193. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11942713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, Chamberlain P, Hurlburt M, & Landsverk J. (2011, Jan). Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 44–53. 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Spear SE, Mendon SJ, Villamar J, Reynolds C, Green CD, Olson C, Adade A, & Brown CH (2020). Conceptualizing and measuring sustainability of prevention programs, policies, and practices. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(1), 136–145. 10.1093/tbm/ibz170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Coatsworth JD, Sullivan S, Briones E, Szapocznik J, & Tolan P. (2007). Familias Unidas: A systemic, parentcentered approach to preventing problem behavior in Hispanic adolescents. In Tolan PH, Szapocznik J, & Sambrano S. (Eds.), Preventing youth substance abuse: Science-based programs for children and adolescents (Vol. xiii, pp. 211–238). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/11488-009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sales A. (2018, March). Frameworks to strategies: Designing implementation interventions. PSMG Virtual Grand Rounds, [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, Jones S, Mauricio AM, Tein JY, & Winslow E. (2016). Effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program for Divorcing Parents: Translation from and experimental prototype to an evidence-based community service. In Israelashvili M. & Roman J. (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of International Prevention Science. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Chapman JE, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Landsverk JA, Stevens J, Glisson C, Rolls-Reutz J, & The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2008, Mar). A survey of the infrastructure for children’s mental health services: Implications for the implementation of empirically supported treatments (ESTs). Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1–2), 84–97. 10.1007/s10488-007-0147-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, & Moher D. (2010). CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC medicine, 8, 18. 10.1186/17417015-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani F. (2002). Machine learning in automated text categorization. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 34(1), 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Skolarus TA, Lehmann T, Tabak RG, Harris J, Lecy J, & Sales AE (2017, Jul 28). Assessing citation networks for dissemination and implementation research frameworks [journal article]. Implementation Science, 12(1), 97. 10.1186/s13012-017-0628-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD (2017, November). Introduction to implementation science for obesity prevention: Frameworks, strategies, measures, and trial designs Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Spear S, Villamar JA, Brown CH, Mendon S, & Palinkas L. (2018). Sustainability of Prevention Programs and Initiatives: A Community Building Framework. Implementation Science.

- Spoth R, Rohrbach LA, Greenberg M, Leaf P, Brown CH, Fagan A, Catalano RF, Pentz MA, Sloboda Z, Hawkins JD, & Society for Prevention Research Type 2 Translational Task Force Members. (2013, Aug). Addressing core challenges for the next generation of type 2 translation research and systems: The translation science to population impact (TSci Impact) framework. Prevention Science, 14(4), 319–351. 10.1007/s11121-012-0362-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S, & Koller D. (2001). Support vector machine active learning with applications to text classification. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 45–66. 10.1162/153244302760185243 [DOI]

- Wang D, Ogihara M, Gallo CG, Villamar J, Smith JD, Vermeer W, Cruden G, Benbow N, & Brown CH (2016). Automatic classification of communication logs into implementation stages via text analysis. Implementation Science, 11(1), 119. 10.1186/s13012-016-04836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb EJ, Campbell DT, Schwartz RD, & Sechrest L. (1999). Unobtrusive Measures. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler I, Weiss L, & Winslow E. (2007). New Beginnings: An empirically-based intervention program for divorced mothers to help children adjust to divorce. In Briesmeister JM & Schaefer CE (Eds.), Handbook of parent training : helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors (Vol. 3rd, pp. 25–66). John Wiley & Sons. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0826/2006052496-b.html Materials specified: Contributor biographical information http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0826/2006052496-b.html Publisher description http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0826/2006052496-d.html [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Plummer BA, Greene SM, Anderson ER, DawsonMcClure SR, Hipke K, & Haine RA (2002). Six-year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorce: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 288(15), 1874–1881. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/data/Journals/JAMA/4852/JOC11877.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Mahrer NE, Millsap RE, Winslow E, Vélez C, Porter MM, Luecken LJ, & Reed A. (2013, Aug). Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families: effects on mental health and substance use outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 81(4), 660–673. 10.1037/a0033235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, West SG, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Coatsworth D, Lengua L, Weiss L, Anderson ER, Greene SM, & Griffin WA (2000, Oct). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother-child programs for children of divorce. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 68(5), 843–856. 10.1037/0022-006x.68.5.843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Foster-Fishman P, Collins C, & Ahn S. (2012, Aug). Testing a Comprehensive Community Problem-solving Framework for Community Coalitions. Journal of community psychology, 40(6), 681–698. 10.1002/jcop.20526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]