Abstract

Mechanical ventilation is a known risk factor for delirium, a cognitive impairment characterized by dysfunction of the frontal cortex and hippocampus. Although IL-6 is upregulated in mechanical ventilation–induced lung injury (VILI) and may contribute to delirium, it is not known whether the inhibition of systemic IL-6 mitigates delirium-relevant neuropathology. To histologically define neuropathological effects of IL-6 inhibition in an experimental VILI model, VILI was simulated in anesthetized adult mice using a 35 cc/kg tidal volume mechanical ventilation model. There were two control groups, as follow: 1) spontaneously breathing or 2) anesthetized and mechanically ventilated with 10 cc/kg tidal volume to distinguish effects of anesthesia from VILI. Two hours before inducing VILI, mice were treated with either anti–IL-6 antibody, anti–IL-6 receptor antibody, or saline. Neuronal injury, stress, and inflammation were assessed using immunohistochemistry. CC3 (cleaved caspase-3), a neuronal apoptosis marker, was significantly increased in the frontal (P < 0.001) and hippocampal (P < 0.0001) brain regions and accompanied by significant increases in c-Fos and heat shock protein-90 in the frontal cortices of VILI mice compared with control mice (P < 0.001). These findings were not related to cerebral hypoxia, and there was no evidence of irreversible neuronal death. Frontal and hippocampal neuronal CC3 were significantly reduced with anti–IL-6 antibody (P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001, respectively) and anti–IL-6 receptor antibody (P < 0.05 and P < 0.0001, respectively) compared with saline VILI mice. In summary, VILI induces potentially reversible neuronal injury and inflammation in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, which is mitigated with systemic IL-6 inhibition. These data suggest a potentially novel neuroprotective role of systemic IL-6 inhibition that justifies further investigation.

Keywords: VILI, delirium, IL-6, COVID-19, neuronal injury

Mechanical ventilation is a well-known risk factor for cognitive dysfunction in critical illness (1–4). The public health significance of mechanical ventilation–associated cognitive dysfunction has been amplified in recent times by the high reported prevalence of acute cognitive dysfunction in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19), many of whom receive mechanical ventilation (5, 6). Although the pathophysiology of mechanical ventilation–associated cognitive dysfunction is believed to be complex and multifactorial, immune-mediated lung–brain interactions are widely believed to play a central role; however, direct mechanistic evidence for this hypothesis remains incomplete (1, 7).

New cognitive dysfunction that occurs during the acute phase of critical illness is referred to as delirium and occurs in up to 80% of mechanically ventilated patients (8). The hallmark clinical feature of delirium is an acute onset of inattention, impaired executive function, and memory impairment—reflecting frontal cortical and hippocampal dysfunction (1). When mild, delirium may be self-limited; however, severe delirium is a known risk factor and harbinger of long-term cognitive decline (3, 9, 10). Although it is widely understood that delirium prevention or mitigation may reduce the risk of long-term cognitive decline, the exact mechanisms that underlie the pathogenesis of mechanical ventilation–associated delirium remain unclear (11, 12). Prior studies have identified a putative role for IL-6 in contributing to delirium, and clinical trials are currently underway to assess the efficacy of IL-6 inhibition on pulmonary and systemic outcomes in patients at risk for ventilation-induced lung injury (VILI); however, the neuropathological effects of IL-6 inhibition remain unknown (13–17).

Accordingly, in this study, we hypothesized that IL-6 inhibition of VILI would result in mitigation of neuronal injury to frontal and hippocampal brain structures.

Methods

Mice and Power Analysis

A total of 44 male or female C57BL/6 mice, aged 6–7 months old (Jackson Laboratory), were used in this study.

Hypothesis generation.

To establish the model of VILI-induced neuronal injury, we assigned male and female mice to one of the following groups: mice anesthetized and mechanically ventilated with 35 cc/kg tidal volume in supine position (VILI) (n = 8), mice anesthetized and mechanically ventilated with 10 cc/kg tidal volume (n = 6), or spontaneous breathing (SB) (n = 6).

Hypothesis validation.

To examine the effects of IL-6 inhibition on delirium-relevant neuropathology, mice were randomized to one of the following groups: VILI plus saline (n = 6), VILI plus anti–IL-6 antibody (n = 6), VILI plus anti–IL-6 receptor antibody (n = 6), or SB control (n = 6).

Based on preliminary immunohistochemical analysis using CC3 (cleaved caspase-3), the greatest group SD and mean difference were 0.12 and 0.3, respectively. Using these values, a power analysis with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test yielded >90% power at the 0.05 significance level with n = 5/group. Only female mice were used for hypothesis validation given that our preliminary analysis showed a trend toward lower CC3 expression in female compared with male VILI mice (Figure E1 in the data supplement). All experiments were conducted in accordance with Cedars-Sinai Medical Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines under an approved protocol and complied with current U.S. law.

VILI Model

We used a previously validated model of VILI achieved by subjecting mice to high tidal volume (35 cc/kg) mechanical ventilation (18–20). In this model, lung injury is achieved by inducing mechanical stretch of alveolar walls that leads to cell deformation, endothelial and epithelial breaks, interstitial edema, and production of inflammatory infiltrates that can be measured in the bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF) (19).

Mice subjected to VILI or those mechanically ventilated with 10 cc/kg tidal volume were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mix of ketamine (Vedco Inc.) and dexmedetomidine (Pfizer) (75 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively), orotracheally intubated, and then mechanically ventilated using an Inspira volume-controlled small animal ventilator (Harvard Apparatus) and ambient room air. All animals were mechanically ventilated in the supine position, and care was taken to ensure that the animals’ heads were positioned consistently in reference to the horizontal plane within each group. The mechanical ventilation parameters to induce VILI were as follows: a tidal volume of 35 cc/kg at a respiratory rate of 70 breaths/minute with 0 positive end-expiratory pressure for a duration of 2 hours. The mechanical ventilation parameters for the control 10 cc/kg group were as follows: a tidal volume of 10 cc/kg at a respiratory rate of 70 breaths/minute with 0 positive end-expiratory pressure for a duration of 2 hours. Subcutaneous saline (0.5 ml) was administered to maintain hydration, and the eyes of mice were protected with a thin coat of Paralube (Dechra) immediately before intubation. During mechanical ventilation, the body temperature of mice was maintained using a 38°C heating pad (Hallowell EMC). Anesthesia was reversed with atipamezole (1 mg/kg in 100 μl of sterile water), and the mice were allowed to recover in their cages on a heating pad for 4 hours before euthanasia followed by tissue collection. Control mice were killed together with the VILI mice.

IL-6 Inhibition

IL-6 signaling was inhibited by systemic administration of two different function-blocking monoclonal antibodies: one that binds IL-6 peptide (α-IL-6) and one that binds the IL-6 receptor (α-IL-6R). Both antibodies were purchased from Bio X Cell (α-IL-6, clone MP5–20F3; α-IL-6R, clone 15A7) and diluted and administered under sterile conditions. Each antibody-treated mouse received 200 μg of either antibody as a 500-μl intraperitoneal injection of a 0.4-μg/μl solution in saline. The dosing ranged from 7.4 mg/kg to 9.4 mg/kg, and the average dose was 8.4 mg/kg. VILI saline mice received 500 μl of saline only. After intraperitoneal injection with either of the IL-6 inhibitors, mice were placed back into cages for 2 hours (21), after which VILI was induced as outlined in the VILI Model section above. During mechanical ventilation, oxygen saturation was recorded every hour in each mouse using the MouseOx Plus (version 1.6; Starr Life Sciences Corp.) system with the thigh sensor.

Brain Isolation and Treatment

At experiment completion, mice were deeply anesthetized and perfused with room temperature PBS with 0.5 mM EDTA (10 ml). Right hemispheres were collected and fixed by submerging in ice-cold PBS-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 30 minutes and then cryo-protected in 2% paraformaldehyde and 30% sucrose at 4°C for 48 hours. Free-floating, 30-μm–thick coronal brain cryosections were prepared and stored at 4°C in PBS and 0.02% sodium azide until staining. As positive control for hypoxic neuronal death, we used mouse tissue obtained from an acute ischemic stroke model (22).

Immunohistochemistry and Microscopy

Sections were affixed to slides by air drying and subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval for 10 minutes in antigen-retrieval solution (pH 6.0; Invitrogen) before permeabilization/blocking in 5% BSA and 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA and 0.01% Triton X-100 in PBS (Ab Diluent). See Table E1 in the data supplement for antibody information. After washing, sections were incubated with a combination of the appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor Plus conjugated; Invitrogen) diluted to 4 μg/ml in Ab Diluent for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, sections were incubated in 0.05% Sudan black B in 70% ethanol for 10 minutes to reduce tissue autofluorescence. Sections were mounted using ProLong Glass with DAPI (Invitrogen). Negative control sections were processed using the same protocol, with the omission of the primary antibody to assess nonspecific labeling. A Carl Zeiss AxioImager Z.2 epi-fluorescence microscope—equipped with standard filter sets/mercury arch lamp, an Apotome 2.0, and an Axiocam HRm camera—controlled by Zen Blue Pro (version 2.3) software was used to acquire and process images. Images of damage marker (CC3, c-fos, and HSP90 [heat shock protein-90]) staining were acquired with a 10× objective (NA 0.3, Zeiss) as a 5 × 5 tiled image that encompassed both the neocortex and the hippocampus of each section. Images of cytokine (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) staining were acquired with the Apotome 2.0 and a 20× objective (NA 0.8, Zeiss) as single-field, 8-μm z-stacks (1-μm interval) and were analyzed and displayed as maximum intensity projections. All acquisition and display settings were the same between groups, and settings were optimized using the VILI group. All images within a figure are set to the same scale.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from frozen left-brain hemisphere samples using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA concentration was measured using nanodrop spectrophotometer, and the integrity of RNA was determined using denatured agarose gel electrophoresis. Using a high-capacity cDNA reverse-transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 μl of total RNA was reverse-transcribed. The cDNA was diluted in a 1:3 ratio for LDHA (lactate dehydrogenase A), SLC2A1 (solute carrier family 2 member-1), and VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A) (hypoxia-inducible genes) and in a 1:400 for internal control 18s gene. Cq values of each gene were obtained using 2 μl of diluted cDNA in 20-μl TaqMan Fast Advanced Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a QuantStudio 3 system. Each reaction was run in duplicate. Predesigned primers for LDHA (Mm01612132_g1), SLC2A1 (Mm00441480_m1), VEGFA (Mm00437306_m1), and 18S (Hs99999901_s1) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Data were analyzed using QuantStudio analysis software. The Ct value of target gene was normalized with internal control gene, and the fold-change expression was calculated with 2−ΔΔCq method.

Image and Statistical Analysis

Fiji (ImageJ version 1.53c) software was used for image analysis and semiquantitation, and Prism 8.3.0 (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis. Analysis was performed by assessors blinded to group allocation. Three coronal sections containing the hippocampus and adjacent cortex were analyzed (one ventral, one mid, and one dorsal) per animal. For damage marker analysis, the following two different regions of interests (ROIs) were drawn on tiled images of sections: an ROI around the frontal neocortex beginning at the midline or an ROI encompassing the entire hippocampus (both with an average area of 315 μm2). A threshold was set to exclude background pixels per ROI on the basis of the pixel intensity histogram, and the number of positive pixels was measured and then expressed as percentage area of the ROI. For cytokine analysis, a single-field z-stack projection from the frontal cortex was analyzed per section. Background pixels were excluded per field on the basis of the pixel intensity histogram, and the intensity of the remaining pixels was averaged to yield mean pixel intensity or used to calculate the percentage area. Values for each protein from the triplicate sections were averaged to yield one number per animal. Statistically significant outliers were determined (ROUT method with Q = 10%) and excluded, and either one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (Tukey’s) or unpaired Student’s t test was used to determine the statistical significance between groups.

Results

An overview of the experimental timeline and representative analyzed ROIs of our VILI-induced neuronal injury model are shown in Figure 1A. There was no significant difference in the age and weight of mice between groups. During the recovery period of mice subjected to mechanical ventilation and after reversal of anesthetics, all animals were active and ambulating and showed no clinical evidence of shock.

Figure 1.

Frontal and hippocampal CC3 (cleaved caspase-3) is significantly elevated in ventilation-induced lung injury (VILI) mice. (A) Schematic of experimental design and representative ROIs of measured brain regions. (B) Quantification of lung inflammation (percentage of PMNs in BALF) (n = 6 in the spontaneous breathing [SB] group, n = 6 in the 10 cc/kg group, and n = 8 in the VILI group). (C and D) Quantification of CC3 in the frontal cortex and the hippocampus, in which each dot represents one animal (n = 6 in the SB group, n = 6 in the 10 cc/kg group, and n = 8 in the VILI group). (E) Representative sections stained for CC3 (positive signal displayed in green) overlaid on DAPI nuclear stain (blue). Magnified regions of an area of frontal neocortex and hippocampus from the micrograph directly above. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001. BALF = BAL fluid; ns = not significant; PMN = polymorphonuclear cell; ROI = region of interest.

Figure 1B shows increased pulmonary inflammation as measured by increased percentage of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) in the BALF of mice subjected to VILI compared with SB mice or mice mechanically ventilated with 10 cc/kg tidal volume. Corresponding representative lung hematoxylin and eosin images demonstrate characteristic lung injury findings in the VILI group, including alveolar wall thickening and the presence of neutrophils, whereas quantification of albumin and IL-6 concentrations in the BALF reveals evidence of altered alveolar capillary barrier and inflammation (23) (Figure E2). During the induction of apoptosis, various signaling pathways converge on the activation, or cleavage, of caspase-3, which in turn activates other apoptotic pathways that lead to genome breakdown (TUNEL [terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase DUTP nick end labeling]-positive), ultimately causing cell death (24). CC3 expression was significantly elevated in frontal and hippocampal brain regions in mice subjected to VILI compared with SB mice or mice anesthetized and mechanically ventilated with 10 cc/kg tidal volume (ANOVA P = 0.0004 and P < 0.0001 for frontal and hippocampal regions, respectively; Figures 1C–E). Subgroup analyses for sex differences showed a nonstatistically significant trend toward increased frontal CC3 expression in male compared with female VILI mice (Figure E1). There was no evidence of cell death indicated by the absence of TUNEL staining in the VILI mice compared with a mouse brain section from an acute ischemic stroke model (Figure E3A). In addition, we studied the expression of HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor-1α) protein, a highly sensitive transcription factor that is upregulated in response to hypoxia, on our experimental groups as well as in a mouse brain section from an acute ischemic stroke model. We found no frontal or hippocampal expression of HIF-1α in VILI mice (Figure E3B).

To formally rule out brain hypoxia as a mediator of cerebral injury, we then assessed the expression of hypoxia-induced genes in brain tissue. We extracted total mRNA from brain tissue from VILI mice and control mice and performed quantitative real-time-PCR for the following three genes that are induced by hypoxia: SCL2A1 (GLUT1), LDHA, and VEGFA. Although increases in the levels of transcripts for these genes were detected in a hypoxic control animal, there were no increases and no significant difference between SB mice, mechanically ventilated control mice, and VILI mice (Figure E3C).

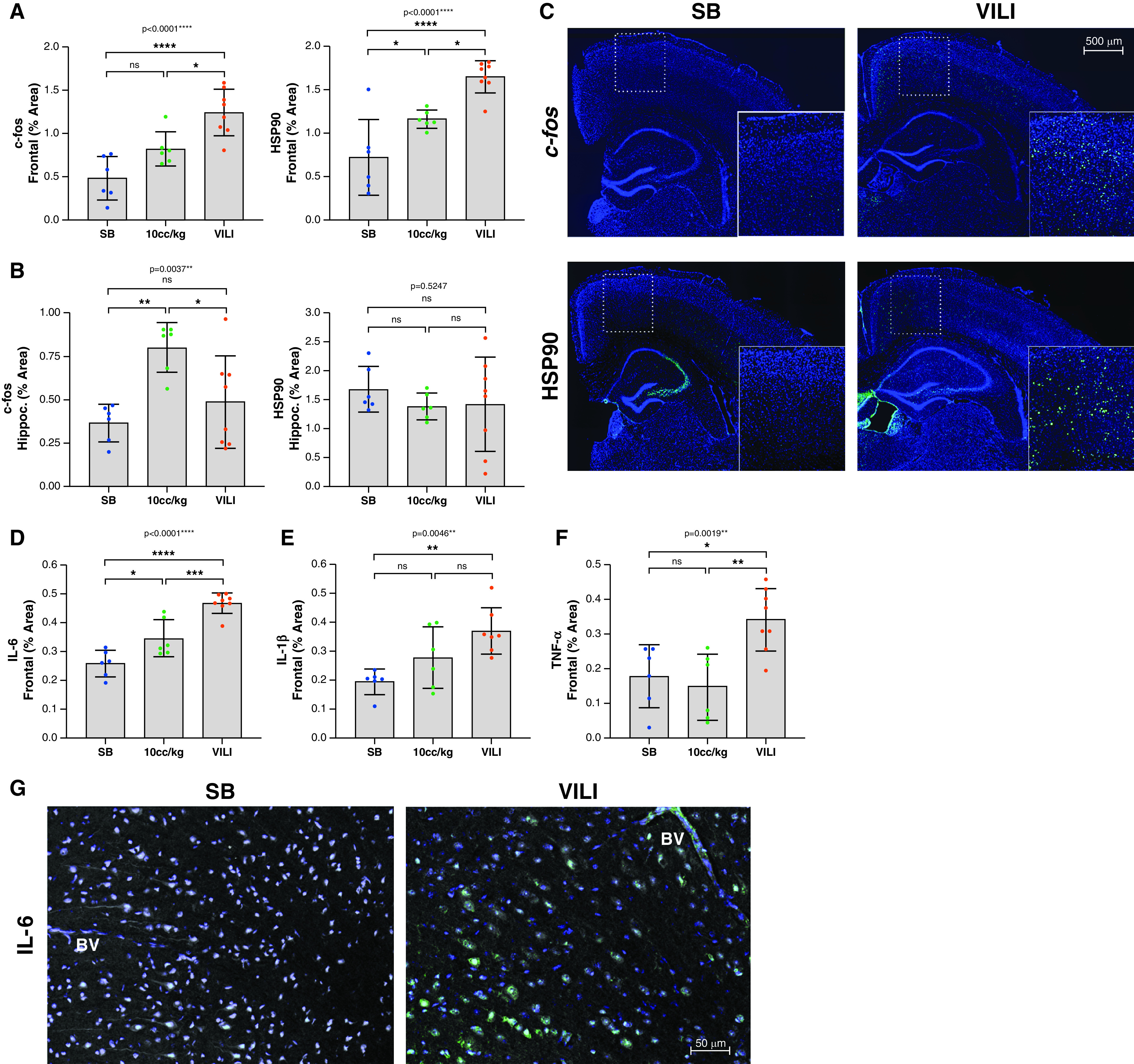

We used the expression of the transcription factor c-fos and the chaperone protein HSP90 to assess neuronal activity and stress, respectively. There was an approximately fourfold increase in c-fos and a twofold increase HSP90 in the frontal cortices of VILI mice compared with SB mice (P < 0.0001), with intermediate changes in the 10 cc/kg group (ANOVA P < 0.0001; Figure 2A). Hippocampal c-fos in the 10 cc/kg group was significantly increased compared with the SB and VILI groups (ANOVA P = 0.0037); however, there was no significant difference in hippocampal HSP90 expression across all three groups (ANOVA P = 0.6247; Figure 2B). Figure 2C shows representative sections stained for either c-fos or HSP90 (positive signal displayed in green) overlaid on DAPI nuclear stain (blue) for VILI and SB groups.

Figure 2.

VILI increases frontal cortical activity, neuronal stress response, and cortical inflammation. (A and B) Quantification of the levels of neuronal activity (c-fos) and of cellular stress response (HSP90 [heat shock protein-90]) within the frontal cortex (A) (n = 6 in the SB group, n = 6 in the 10 cc/kg group, and n = 8 in the VILI group) and hippocampus (B) (n = 6 in the SB group, n = 6 in 10 cc/kg group, and n = 8 in the VILI group). Each dot represents one animal. (C) Representative sections stained for either c-fos or HSP90 (positive signal displayed in green) overlaid on DAPI nuclear stain (blue) for the SB and VILI groups. Magnified regions of a section of the frontal neocortex are inset. (D) IL-6 is significantly increased in VILI brains compared with SB or 10 cc/kg control mice (n = 6 in the SB group, n = 6 in the 10 cc/kg group, and n = 8 in the VILI group). (E) IL-1β is significantly increased in VILI brains compared with SB brains, but there is no significant difference in IL-1β between the 10 cc/kg group and SB group or the 10 cc/kg group and VILI group. (F) TNF-α is significantly increased in VILI group compared with both the 10 cc/kg and SB groups, but there is no significant difference in TNF-α between the SB and 10 cc/kg groups. (G) Representative micrographs stained for IL-6 (green). Of note is the IL-6 staining within the cortical BV in the VILI group that is absent in the SB control group. Cellular morphology (tissue autofluorescence) is displayed in gray, and cell nuclei are revealed by DAPI staining (blue). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. BV = blood vessel.

To further characterize the molecular pathophysiology associated with VILI, we measured the amounts of three different inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) in the frontal cortex. Compared with SB animals, there was a significant 1.7-fold increase in IL-6 in VILI animals (P < 0.0001), with intermediate changes in the 10 cc/kg group (ANOVA P < 0.0001; Figure 2D). IL-1β was localized to the intercellular space of the brain parenchyma (not shown) and significantly increased by 1.7-fold in the VILI group compared with SB group, with no significant difference between the 10 cc/kg and the SB or VILI groups (ANOVA P = 0.0046; Figure 2E). There was no significant difference in TNF-α expression between the SB and 10 cc/kg groups; however, TNF-α was significantly increased in the VILI group compared with both the SB and 10 cc/kg groups (ANOVA P = 0.0019) (Figure 2F). Of note, while IL-6 expression was mostly localized to neurons, IL-6 positive staining was also seen in cortical blood vessels in the VILI mice, whereas none was seen in the cortical blood vessels of SB control mice (Figure 2G). All three cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) were significantly and positively correlated with CC3 (r2 = 0.5929/P = 0.0023, r2 = 0.2993/ P = 0.0429, and r2 = 0.3465/P = 0.0268, respectively) (Figure 3A). There was an apparent colocalization between IL-6– and CC3-positive frontal cortical neurons (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Cortical IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α positively correlate with neuron injury marker. (A) Pearson’s correlation analyses demonstrate significant positive relationships between cortical CC3 and IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α. Animals in the SB group are indicated in blue, and animals in the VILI group are indicated in red. Significance (P) and fitness (r2) values are indicated. (B) Micrographs of frontal cortical neurons stained for IL-6 displayed in green and CC3 displayed in red. Magnified areas of individual neurons and glial cells are inset. Note that CC3-positive neurons also costain for IL-6 in neocortex of VILI animals. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

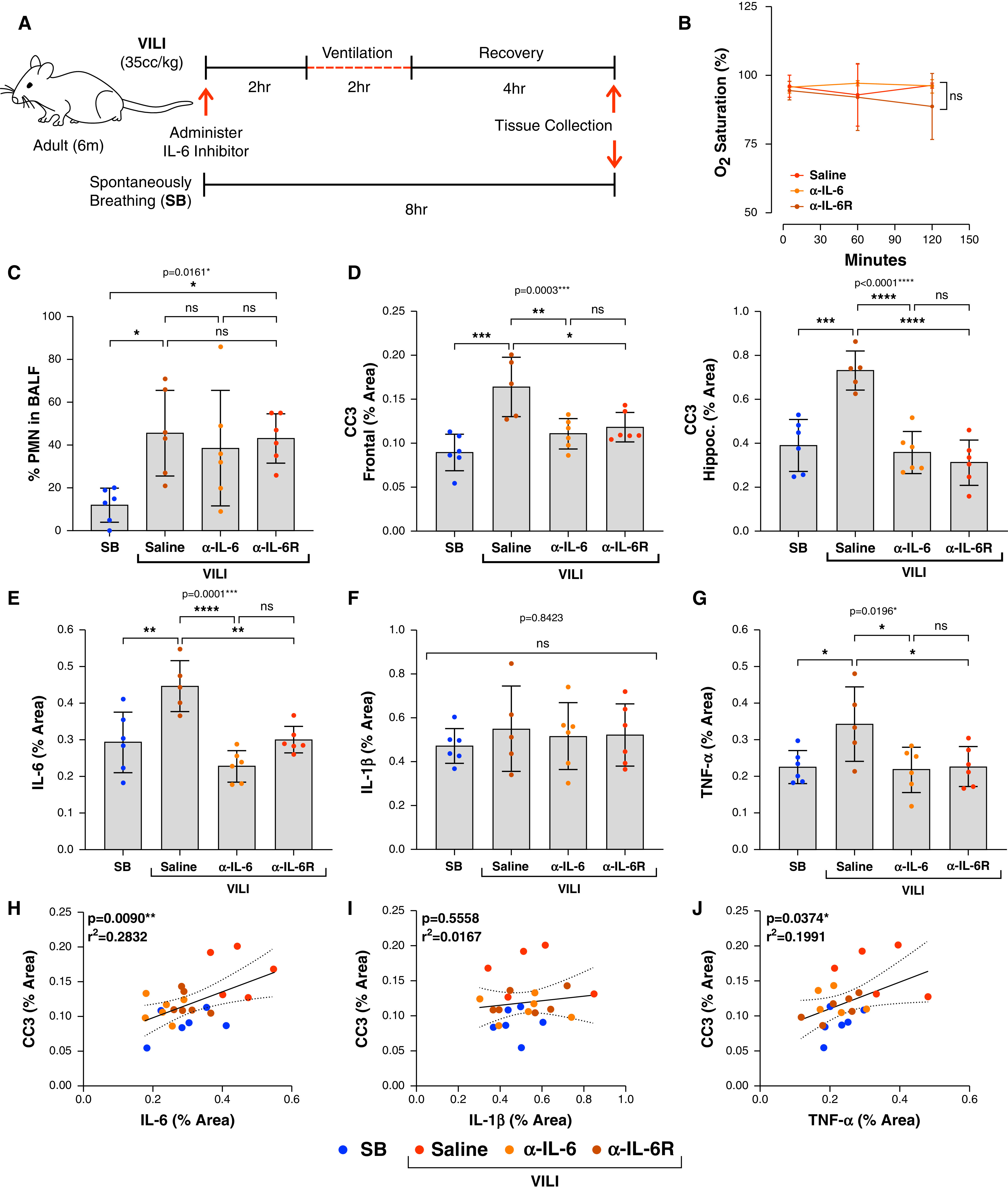

To study the pathogenic relevance of IL-6 on delirium-relevant neuropathology in VILI, we examined the effects of IL-6 inhibition in mice with VILI. A schematic illustration of the experimental design and timeline is shown in Figure 4A. There were no significant differences in oxygen saturation between the three VILI groups (Figure 4B). Although the percentage of PMNs significantly increased with VILI compared with SB (ANOVA P = 0.0161), there were no significant differences in the percentage of PMNs between the VILI saline and IL-6–inhibited VILI mice (Figure 4C). However, there were significant reductions in frontal and hippocampal CC3 expression in both the anti–IL-6 antibody (P < 0.01 and P < 0.0001, respectively) and anti–IL-6 receptor antibody (P < 0.05 and P < 0.0001, respectively) groups compared with saline-treated control mice (ANOVA P = 0.0003 for frontal cortex and P < 0.0001 for hippocampus), although there was no significant difference between the IL-6–inhibited groups (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

IL-6 inhibition significantly reduces frontal and hippocampal CC3 expression. (A) Schematic of experimental design and timeline. (B) There are no significant differences in oxygen saturations between the three VILI intervention groups (VILI saline, VILI anti–IL-6 antibody, and VILI anti–IL-6 receptor antibody) (n = 6/group). (C) PMNs in BALF are not significantly different between the three VILI groups (n = 6/group). (D) Frontal and hippocampal CC3 expressions are significantly increased in the VILI saline group compared with SB control, but significantly reduced in both VILI IL-6–inhibited groups (n = 5–6/group). One VILI saline animal was excluded because of poor perfusion, resulting in inaccurate analysis. (E) IL-6 is significantly increased in the VILI saline group compared with the SB control group but is significantly reduced in both VILI IL-6–inhibited groups (n = 5–6/group). (F) There is no significant difference in the percentage area of IL-1β between all groups (n = 5–6/group). (G) TNF-α is significantly increased in the VILI saline group compared with the SB control group and is significantly reduced in both VILI IL-6–inhibited groups (n = 5–6/group). (H–J) Pearson’s correlation analysis shows a direct and significant relationship between IL-6 and CC3 and TNF-α and CC3 but no significant relationship between IL-1β and CC3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

There was a significant increase in IL-6 in the frontal cortex of saline-treated VILI mice compared with SB control mice (P < 0.01) that was mitigated with both anti–IL-6 antibody (P < 0.0001) and anti–IL-6 receptor antibody (P < 0.01) (ANOVA P = 0.0001). Again, there was no significant difference between the two IL-6–inhibited groups (Figure 4E). There were no significant changes in IL-1β between all four groups (ANOVA P = 0.8423) (Figure 4F) while TNF-α was significantly reduced in both IL-6 inhibited groups (ANOVA P = 0.0196) (Figure 4G). There were significant positive correlations between CC3 expression and IL-6 (r2 = 0.2832/P = 0.0090) and TNF-α (r2 = 0.1991/P = 0.0374) and no significant correlation between CC3 and IL-1β (Figures 4H–J). Plasma IL-6 concentrations from each of the four groups are shown in Figure E4A. We performed CC3 quantification using Western blot, which shows findings that are consistent with the CC3 expression levels assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in all groups (Figures E4B and E4C).

Discussion

This study provides direct pathophysiological evidence of potentially reversible IL-6–mediated frontal and hippocampal neuronal injury and inflammation in an animal model of VILI. These findings correlate with the expected affected cortical areas that would manifest the syndrome of delirium, mainly inattention, executive dysfunction, and memory impairment, and suggest a potential novel therapeutic role for IL-6 inhibition in reducing the neuropathology of mechanical ventilation–associated cognitive dysfunction.

Mitigation of frontal and hippocampal neuronal injury with systemic IL-6 inhibition in VILI may have potentially far-reaching clinical implications given the high rates of cognitive dysfunction after mechanical ventilation (1). Although prior research has shown lung stretch–induced hippocampal apoptosis in a model of mechanical ventilation (25), our study provides the first evidence of a novel mechanistic role of the IL-6 signaling pathway in mediating frontal and hippocampal neuronal injury in VILI. Although the putative role of IL-6 in lung injury–related systemic stress (16, 26–34) has already prompted clinical trials of IL-6 inhibition to improve pulmonary and systemic outcomes among patients with COVID-19 (35–37), the neurological effects of these therapies remain unknown. The findings from this study provide preclinical justification to assess IL-6 inhibition as a potential therapy to prevent and/or treat mechanical ventilation–associated cognitive dysfunction.

Although our data show increased initiation of neuronal apoptosis, activation, and inflammatory stress as evidenced by increased activation of CC3, c-fos, and HSP90, it is encouraging that there was no TUNEL-positive staining to suggest apoptotic neuronal death. These findings suggest that the clinical onset of delirium may precede irreversible neuronal death and indicate a window of opportunity within which implementation of timely interventions may prevent the long-term neurocognitive impairment associated with mechanical ventilation. This phenomenon may be analogous to other conditions in which there are injury without cell death, (e.g., cerebral ischemia without infarction or stable angina) and is consistent with the clinical picture of delirium as a manifestation of cerebral stress that may be self-limited when mild or irreversible when severe.

To exclude possible effects of anesthesia and mechanical ventilation on neuronal injury and inflammation, we provided the same anesthesia regimen and mechanically ventilated mice with 10 cc/kg tidal volume (25, 38, 39). We found that both lung inflammation and the amount of CC3 expression in the investigated brain regions were not significantly different than the SB group (Figure 1B-D). These findings suggest that the neuronal injury observed in the VILI groups was not due to anesthetics and mechanical ventilation but rather attributable to the effects of pulmonary and systemic inflammation of VILI. Furthermore, although hypoxia is known to contribute to deleterious cerebral effects, we found no evidence of increased hypoxic cerebral injury as measured by HIF-1α staining or mRNA expression of three hypoxia-inducible genes in the VILI groups compared with the control groups. Overall, these findings indicate that hypoxic injury alone does not explain the significantly increased markers of neuronal injury and inflammation in the VILI groups.

There are notable limitations of this study to consider. Although 35 cc/kg tidal volume is a previously published model of VILI, the clinical relevance may be limited, as such a supraphysiological tidal volume that may induce physical disruption to the lung tissue is not typically administered to patients. Although the heterogeneity of the many potential etiologies that could lead to mechanical ventilation and VILI likely renders any one model insufficient to reflect the entire phenotypic spectrum of VILI-induced neuropathology, future studies using alternative models of lung injury are indicated. On the other hand, we measured frontal and hippocampal neuronal injury using a model in which there was no precipitating cause of lung injury or concurrent systemic illness and a short duration of mechanical ventilation followed by a recovery period, suggesting that even mild isolated VILI may precipitate delirium-relevant neuropathological changes. An additional strength of our data is that we used contemporaneous control animals for our therapeutic efficacy experiment and confirmed the primary CC3 IHC data with Western blot. Furthermore, although the high tidal volume VILI model may decrease carbon dioxide concentrations, these were not measured and reported in this study. However, because low carbon dioxide would be expected to induce hypoxic cerebral injury due to cerebral vasoconstriction (40–42), we consider any effects of hypocapnia-mediated brain injury in the VILI group to have been accounted for in our IHC analysis of hypoxic cerebral injury using HIF-1α and mRNA quantification of three early hypoxia-induced genes.

An additional important limitation is that these data were not correlated with biobehavioral assessments, in part because there is no validated battery of assessments to assess delirium in animals; future experiments are needed to establish and correlate these pathological findings with biobehavioral testing for delirium. Also, because it is possible that the pattern of neurological injury could vary at different time points and with more prolonged exposure to VILI, future studies are indicated to vary these parameters as well as to assess effects of mechanical ventilation on recovery and variations in carbon dioxide concentrations. In addition, future studies are indicated to trace the origins of cerebral IL-6 using RNA in situ hybridization of lung and brain tissue. Finally, although we did not use isotype-matched control antibodies, we obtained consistent results showing mitigation of frontal/hippocampal CC3 expression using two different IL-6 inhibitors with two different IgG subtypes—IgG1 for anti–IL-6 and IgG2b for anti–IL-6R—thus, it is not likely that nonspecific antibody-binding effects accounted for the measured differences in CC3 expression.

Conclusions

In an animal model of VILI, we found that systemic IL-6 inhibition significantly reduced neuronal injury in the frontal cortex and hippocampus. These findings correlate with the structures that are believed to contribute to the symptomatology of delirium and call for future studies to assess the neurocognitive and behavioral effects of IL-6 inhibition in VILI.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging grant R03AG064106 (S.L.) and an American Academy of Neurology Career Development Award (S.L.).

Author Contributions: N.A.S.: Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting of work and critical revisions. F.A., A.E.C., and M.H.R.: Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. P.S.R.: Analysis and interpretation of data. P.L.N.: Acquisition of data. M.M.G.: Drafting of work and critical revisions. S.T.: Drafting of work and critical revisions. M.O.A.: Drafting of work and critical revisions. S.A.K.: Analysis and interpretation of data and acquisition of data. E.W.E.: Drafting of work and critical revisions. S.L.: Conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of work, critical revisions, and final approval of the version to be published.

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript. The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of content online at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2021-0072OC on May 20, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Sasannejad C, Ely EW, Lahiri S. Long-term cognitive impairment after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a review of clinical impact and pathophysiological mechanisms. Crit Care. 2019;23:352. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Slutsky AS, Tremblay LN. Multiple system organ failure. Is mechanical ventilation a contributing factor? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1721–1725. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9709092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilcox ME, Brummel NE, Archer K, Ely EW, Jackson JC, Hopkins RO. Cognitive dysfunction in ICU patients: risk factors, predictors, and rehabilitation interventions. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9)(Suppl 1):S81–S98. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a16946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, et al. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pun BT, Badenes R, Heras La Calle G, Orun OM, Chen W, Raman R, et al. COVID-19 Intensive Care International Study Group. Prevalence and risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (COVID-D): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:239–250. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30552-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lahiri S, Regis GC, Koronyo Y, Fuchs DT, Sheyn J, Kim EH, et al. Acute neuropathological consequences of short-term mechanical ventilation in wild-type and Alzheimer’s disease mice. Crit Care. 2019;23:63. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286:2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vasunilashorn SM, Fong TG, Albuquerque A, Marcantonio ER, Schmitt EM, Tommet D, et al. Delirium Severity Post-Surgery and its Relationship with Long-Term Cognitive Decline in a Cohort of Patients without Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:347–358. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER, Kosar CM, Tommet D, Schmitt EM, Travison TG, et al. The short-term and long-term relationship between delirium and cognitive trajectory in older surgical patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis DH, Muniz-Terrera G, Keage HA, Stephan BC, Fleming J, Ince PG, et al. Association of Delirium With Cognitive Decline in Late Life: A Neuropathologic Study of 3 Population-Based Cohort Studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:244–251. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1513–1520. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Simone MJ, Tan ZS. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of delirium and dementia in older adults: a review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:506–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Capri M, Yani SL, Chattat R, Fortuna D, Bucci L, Lanzarini C, et al. Pre-Operative, High-IL-6 Blood Level is a Risk Factor of Post-Operative Delirium Onset in Old Patients. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:173. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: mechanisms and implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:222–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bickenbach J, Biener I, Czaplik M, Nolte K, Dembinski R, Marx G, et al. Neurological outcome after experimental lung injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;179:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramiro S, Mostard RLM, Magro-Checa C, van Dongen CMP, Dormans T, Buijs J, et al. Historically controlled comparison of glucocorticoids with or without tocilizumab versus supportive care only in patients with COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome: results of the CHIC study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1143–1151. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson MR, Choudhury S, Goddard ME, O’Dea KP, Nicholson AG, Takata M. High tidal volume upregulates intrapulmonary cytokines in an in vivo mouse model of ventilator-induced lung injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2003;95:1385–1393. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00213.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L379–L399. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bastarache JA, Blackwell TS. Development of animal models for the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:218–223. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prabhakara R, Harro JM, Leid JG, Keegan AD, Prior ML, Shirtliff ME. Suppression of the inflammatory immune response prevents the development of chronic biofilm infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:5010–5018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05571-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rajput PS, Lyden PD, Chen B, Lamb JA, Pereira B, Lamb A, et al. Protease activated receptor-1 mediates cytotoxicity during ischemia using in vivo and in vitro models. Neuroscience. 2014;281:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, Groshong SD, Matthay MA, Slutsky AS, et al. Acute Lung Injury in Animals Study Group. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:725–738. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zille M, Farr TD, Przesdzing I, Müller J, Sommer C, Dirnagl U, et al. Visualizing cell death in experimental focal cerebral ischemia: promises, problems, and perspectives. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:213–231. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. González-López A, López-Alonso I, Aguirre A, Amado-Rodríguez L, Batalla-Solís E, Astudillo A, et al. Mechanical ventilation triggers hippocampal apoptosis by vagal and dopaminergic pathways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:693–702. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0691OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meduri GU, Annane D, Chrousos GP, Marik PE, Sinclair SE. Activation and regulation of systemic inflammation in ARDS: rationale for prolonged glucocorticoid therapy. Chest. 2009;136:1631–1643. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meduri GU, Headley S, Kohler G, Stentz F, Tolley E, Umberger R, et al. Persistent elevation of inflammatory cytokines predicts a poor outcome in ARDS. Plasma IL-1 beta and IL-6 levels are consistent and efficient predictors of outcome over time. Chest. 1995;107:1062–1073. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.4.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goldman JL, Sammani S, Kempf C, Saadat L, Letsiou E, Wang T, et al. Pleiotropic effects of interleukin-6 in a “two-hit” murine model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pulm Circ. 2014;4:280–288. doi: 10.1086/675991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cross LJ, Matthay MA. Biomarkers in acute lung injury: insights into the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:355–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang SH, Gangidine M, Pritts TA, Goodman MD, Lentsch AB. Interleukin 6 mediates neuroinflammation and motor coordination deficits after mild traumatic brain injury and brief hypoxia in mice. Shock. 2013;40:471–475. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Antunes AA, Sotomaior VS, Sakamoto KS, de Camargo Neto CP, Martins C, Aguiar LR. Interleukin-6 plasmatic levels in patients with head trauma and intracerebral hemorrhage. Asian J Neurosurg. 2010;5:68–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erta M, Quintana A, Hidalgo J. Interleukin-6, a major cytokine in the central nervous system. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1254–1266. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hewett SJ, Jackman NA, Claycomb RJ. Interleukin-1β in Central Nervous System Injury and Repair. Eur J Neurodegener Dis. 2012;1:195–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinha P, Matthay MA, Calfee CS. Is a “Cytokine Storm” Relevant to COVID-19? JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1152–1154. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gubernatorova EO, Gorshkova EA, Polinova AI, Drutskaya MS. IL-6: Relevance for immunopathology of SARS-CoV-2. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105954. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen X, Zhao B, Qu Y, Chen Y, Xiong J, Feng Y, et al. Detectable Serum Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Viral Load (RNAemia) Is Closely Correlated With Drastically Elevated Interleukin 6 Level in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1937–1942. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Quilez ME, Fuster G, Villar J, Flores C, Martí-Sistac O, Blanch L, et al. Injurious mechanical ventilation affects neuronal activation in ventilated rats. Crit Care. 2011;15:R124. doi: 10.1186/cc10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen C, Zhang Z, Chen T, Peng M, Xu X, Wang Y. Prolonged mechanical ventilation-induced neuroinflammation affects postoperative memory dysfunction in surgical mice. Crit Care. 2015;19:159. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0882-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Curley G, Kavanagh BP, Laffey JG. Hypocapnia and the injured brain: more harm than benefit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1348–1359. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cf2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carrera E, Schmidt JM, Fernandez L, Kurtz P, Merkow M, Stuart M, et al. Spontaneous hyperventilation and brain tissue hypoxia in patients with severe brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:793–797. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.174425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schneider GH, Sarrafzadeh AS, Kiening KL, Bardt TF, Unterberg AW, Lanksch WR. Influence of hyperventilation on brain tissue-PO2, PCO2, and pH in patients with intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1998;71:62–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6475-4_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]