Abstract

A growing literature suggests robust associations between dimensions of emotion regulation and emotional disorder psychopathology. However, limited research has investigated associations of emotion regulation dimensions across several emotional disorders (transdiagnostic associations), or the incremental validity of emotion regulation versus the higher-order construct of neuroticism. The current study used exploratory structural equation modeling and a large clinical sample (N = 1,138) to: (a) develop a multidimensional emotion regulation measurement model, (b) evaluate the differential associations between latent emotion regulation dimensions and five latent emotional disorder symptom dimensions (social anxiety, depression, agoraphobia/panic, obsessions/compulsions, generalized worry), and (c) determine the incremental contribution of emotion regulation in predicting symptom dimensions beyond neuroticism. The best-fitting measurement model of emotion regulation included four dimensions: Problematic Responses, Poor Recognition/Clarity, Negative Thinking, and Emotional Inhibition/Suppression. Although many zero-order associations between the four latent emotion regulation dimensions and five latent symptom dimensions were significant, few associations remained significant in a structural regression model that included neuroticism. Specifically, Negative Thinking and Problematic Responses incrementally predicted depression symptoms, while Emotional Inhibition/Suppression predicted both social anxiety and depression symptoms. Associations between neuroticism and the emotional disorder dimensions were similar regardless of whether the emotion regulation dimensions were held constant. These results suggest that self-reported emotion regulation dimensions are associated with the severity and expression of a range of emotional disorder symptoms, but that some emotion regulation dimensions have limited incremental validity after accounting for general emotional reactivity. Studies of emotion regulation should assess neuroticism as a key covariate.

Keywords: emotion regulation, emotional disorders, internalizing disorders, neuroticism

emotion regulation (ER) is a multifaceted construct that has been the focus of a growing area of research since the mid-1990s due to its role in general well-being and the development and maintenance of psychopathology (Gross, 2015; Gross & Jazaieri, 2014). ER is the process that an individual utilizes to monitor, evaluate, and modify emotions in order to accomplish goals (Sheppes et al., 2015). This broad definition encompasses all facets of ER occurring both within an individual (e.g., recognizing emotions) and between the individual and their environment (e.g., avoidance). Prior research has demonstrated that ER includes a wide range of social, behavioral, and cognitive processes (Fernandez et al., 2016; Garnefski et al., 2001; Gross, 2015). For example, emotions can be regulated (or dysregulated) through overt behaviors such as expressing (vs. suppressing) emotional reactions alone or in front of others, or avoiding or escaping emotionally evocative situations and environments (Garnefski et al., 2001). Many cognitive ER processes such as denial, rumination, reappraisal, catastrophizing, and problem solving also have been operationalized (Garnefski et al., 2001; Sloan et al., 2017).

Several theoretical models of ER have been proposed, with leading models varying in emphasis on dispositional ER abilities (e.g., emotional awareness; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), use of adaptive versus maladaptive ER strategies (e.g., suppression, experiential avoidance; Aldao, 2013), and temporal dynamics/context (Gross, 2015). According to Gross’ (2015) extended process model, for adaptive ER to take place, individuals must be able to (a) be aware of their emotions and understand the emotional context, (b) have an ER goal to decrease or increase their emotional experience, and (c) select and use ER strategies to reach their goal. Failure to utilize adaptive ER strategies can prevent an individual from achieving an ER goal. Individuals who frequently use maladaptive ER strategies are at risk of being emotionally dysregulated, which is associated with increased negative affect and a higher probability of having an emotional (internalizing) disorder (Campbell-Sills et al., 2014; Garnefski et al., 2001; Gross & Jazaieri, 2014; Jazaieri et al., 2014). Research suggests that ER strategies such as cognitive reappraisal, emotional acceptance, and problem solving are more adaptive than suppression, rumination, and avoidance (Aldao, Nolen-Nocksema & Schweizer, 2010).

The literature has relied heavily on self-report questionnaires to assess ER abilities and strategies (Blalock et al., 2016; Fernandez et al., 2016; Goldin et al., 2014; Velasco et al., 2006). Existing ER questionnaires have subscales that assess facets of ER ranging from broad emotional awareness and acceptance (e.g., the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) to specific cognitive and behavioral ER strategies (e.g., Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; Gross & John, 2003). Other ER questionnaires assess both emotional awareness and specific ER strategies (e.g., Trait Meta-Mood Scale; Salovey et al., 1995). Research has established associations between self-reported dimensions of ER and emotional disorder psychopathology (e.g., anxiety and mood disorders; Sheppes et al., 2015). Studies have consistently found that use of maladaptive ER strategies is associated with increased severity of broadly defined anxiety and depression symptoms (e.g., Berking et al., 2014; Wirtz et al., 2014). For example, a meta-analysis by Aldao et al. (2010) investigated the strength of the associations between six ER dimensions (acceptance, avoidance, rumination, problem-solving, reappraisal, and suppression) and four mental disorder categories (anxiety, depression, eating disorder, and substance abuse). Maladaptive strategies were strongly associated with a broad range of psychopathology, with rumination, suppression, avoidance, and lack of reappraisal demonstrating the strongest associations with depression and anxiety disorders (and generally slightly stronger associations with depression than anxiety).

There is limited evidence for associations between facets of ER and more specific emotional disorders or symptom dimensions. For example, individuals with social anxiety disorder (SAD) tend to use more emotional suppression than cognitive reappraisal (Blalock et al., 2016; Goldin et al., 2014; Jazaieri et al., 2014). Rumination is a common maladaptive ER strategy in individuals with SAD, major depressive disorder (MDD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; D’Avanzato et al., 2013; Joormann & Quinn, 2014; Sloan et al., 2017). Likewise, emotional avoidance is common among patients with panic disorder (PD), SAD, GAD, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (Sloan et al., 2017; Tull & Roemer, 2007; Wirtz et al., 2014). Most of this literature has studied ER within a single emotional disorder, with few studies investigating differential associations of ER facets with multiple emotional disorders. One exception is D’Avanzato et al. (2013), who found that individuals with MDD reported more use of rumination and less use of reappraisal than those with SAD, while individuals with SAD reported more use of expressive suppression than individuals with MDD.

Questions also remain surrounding the incremental validity of ER facets versus the higher-order transdiagnostic dimension of neuroticism. Neuroticism is characterized as one’s tendency to experience negative affect in response to stress, and it is a well-established risk factor for the development and maintenance of emotional disorder psychopathology (Khan et al., 2005; Lahey, 2009; Saulsman & Page, 2004). Given that ER and neuroticism are strongly correlated (Stanton et al., 2016; Wiltgen et al., 2018), it is important to understand what associations, if any, ER has with emotional disorder symptoms after holding the (robust) higher-order construct of neuroticism constant. In other words, ER dimensions may not uniquely influence the severity or expression of emotional disorder symptoms (poor incremental validity) above and beyond the degree to which an individual is generally emotionally reactive and experiences negative affect. Although some studies have evaluated ER as a mediator of the relationship between neuroticism and emotional disorder symptoms (e.g., Mohammadkhani et al., 2016; Muris et al., 2005; Wang, Shi, & Li, 2009), unique associations (e.g., partial correlations or multivariate regression coefficients) between ER and emotional symptom dimensions holding neuroticism constant typically are not reported.

To address these limitations, Stanton et al. (2016) evaluated the associations between ER dimensions assessed by the DERS and the Big Five personality domains (i.e., neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness) and the degree to which the DERS dimensions incrementally predicted a range of different internalizing and externalizing disorder symptoms over Big Five traits. Using a community sample (N = 288), two latent ER dimensions were extracted via factor analysis from the six DERS subscales: Poor Recognition (defined by the Lack of Emotional Awareness and Lack of Emotional Clarity subscales) and Problematic Responses (defined by the other four DERS subscales). Neuroticism was strongly correlated with (but distinct from) both DERS factors (e.g., Problematic Responses r = .62). Problematic Reponses had moderately sized positive associations with virtually all (self-report) symptom subscales and composite scales of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II, e.g., Dysphoria, Lassitude, Social Anxiety, Panic, OCD, Agoraphobia; Watson et al., 2012), even when holding neuroticism constant. Poor Recognition also had moderately sized and significant zero-order associations with most IDAS-II scales, but associations were much smaller and often nonsignificant holding neuroticism constant.

These findings highlight the possible transdiagnostic importance the Problematic Responses ER dimension, and suggest that other ER dimensions (e.g., Poor Recognition) may be less relevant to the severity and expression of emotional disorders after accounting for general emotional reactivity. Nevertheless, research is needed to replicate and expand on Stanton et al. (2016) latent ER dimensions of Problematic Responses and Poor Recognition (e.g., in clinical samples), and their associations with emotional disorder symptom dimensions above and beyond neuroticism. For instance, research has not evaluated the distinctiveness or incremental validity of cognitive and behavioral ER strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) from Problematic Responses or Poor Recognition, or the transdiagnostic relevance of other ER dimensions across a range of different emotional disorders. Cognitive and behavioral ER strategies may be more strongly associated with symptom severity than general emotional awareness (i.e., ER abilities).

Accordingly, the goals of the study were to: (a) develop a unified multidimensional measurement model of ER abilities and strategies using several well-validated ER questionnaires and a large, diagnostically heterogeneous clinical sample, (b) evaluate the differential associations between facets of ER and several emotional disorder symptom dimensions, and (c) determine the incremental contribution of ER dimensions above and beyond neuroticism in predicting emotional disorder symptoms. Although we hoped to replicate and expand on the ER dimensions identified by Stanton et al. (2016), specific hypotheses about the nature of the ER measurement model (e.g., number or types of latent dimensions) and associations with symptom dimensions were not made because previous studies have not attempted to explicate latent dimensions derived from many different ER measures. Nevertheless, we had two broad hypotheses. First, we expected that each ER dimension would have significant zero-order associations with multiple emotional disorder symptom dimensions. Second, we hypothesized that these associations would shrink (and possibly be nonsignificant) when holding neuroticism constant. In contrast, we expected neuroticism to be significantly associated with all symptom dimensions regardless of holding the ER dimensions constant.

Method

SAMPLE

The sample consisted of 1,138 adults presenting for assessment and treatment at a large outpatient clinic specializing in cognitive-behavioral treatments for emotional disorders. The sample was predominantly female (60.6%), Caucasian (82.2%), and of non-Hispanic (91.2%) ethnicity, with smaller percentages identifying as African American (9.7%) and Asian (6.6%). The average age of the sample was 31.1 years (SD = 12.3, range = 18 to 76). Exclusionary criteria were current suicidal/homicidal intent and/or plan requiring crisis intervention, psychotic symptoms, or significant cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia, mental retardation). These criteria were assessed during an initial telephone screening and re-assessed during the diagnostic assessment (described below). Participants also completed a battery of self-report questionnaires that included measures of ER and emotional disorder symptoms. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All study procedures were approved by the governing Institutional Review Board.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

Doctoral students and doctoral-level clinical psychologists assessed patients for current diagnoses using the Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (ADIS-5; Brown & Barlow, 2014). The ADIS-5 is a semistructured interview designed to ascertain reliable diagnosis of DSM-5 anxiety, mood, somatoform, obsessive-compulsive, trauma, and substance use disorders, and to screen for the presence of other conditions (e.g., eating and psychotic disorders). For each DSM diagnosis, interviewers assign a 0–8 clinical severity rating (CSR) to indicate the degree of distress and functional impairment associated with the disorder (0 = none, 8 = very severely disturbing/disabling). Disorders that meet or exceed the threshold for a formal DSM diagnosis are assigned CSRs of ≥4 (definitely disturbing/disabling). The ADIS-5 also allows diagnosticians to make dimensional ratings using 0 to 8 scales for key disorder features (e.g., fear ratings for 16 social situations). Ratings were obtained in several diagnostic sections (e.g., agoraphobia, social anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, depression) regardless of presenting problems or if the disorder was assigned at a clinical level (i.e., dimensional ratings were administered without skip-outs). Although inter-rater reliability data were not available for the current sample, prior studies have found both ADIS dimensional ratings and ADIS diagnoses to have good-to-excellent inter-rater reliability when using the same interview training procedures as in the current study (see Brown et al., 2001).

The most common disorders were SAD (47.6%), GAD (46.7%), unipolar depression (34.2%; MDD = 18.1%, persistent depressive disorder = 16.1%), specific phobia (16.1%), panic disorder (15.9%), OCD (15.3%), and agoraphobia (14.4%). Each diagnosis was associated with moderately severe interference and distress on average (i.e., M CSRs = 4.9–5.3, SD = 0.9–1.0). Comorbidity was common, with 70.3% of the sample diagnosed with ≥2 disorders (M # diagnoses = 2.4, SD = 1.4). The most common patterns of comorbidity (disorder pairs) were: SAD and GAD (24.9% of the sample), GAD and depression (22.4%), SAD and depression (18.4%), and panic disorder and agoraphobia (10.5%).

EMOTION REGULATION MEASURES

A goal of the study was to establish a unified ER measurement model capturing a range of different ER constructs. Accordingly, several measures were selected in order to provide broad coverage of well-established ER abilities (e.g., emotional awareness) and cognitive and behavioral ER strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, expressive suppression, experiential avoidance). Subscales from four self-report measures were used to develop the measurement model of ER: the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004), the Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS; Salovey et al., 1995), the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Gross & John, 2003), and the Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (MEAQ; Gámez et al., 2011). Summed subscale scores were created based on how each subscale was operationalized in the original validation study for each measure (cited above). The DERS includes six subscales: Non-Acceptance of Emotional Responses (6-items, Cronbach’s a in current sample = .92), Difficulty with Goal-Directed Behavior (5-items, α =.70), Impulse Control Difficulties (6-items, α = .83),Lack of Emotional Awareness (6-items, α = .63), Limited ER Strategies (8-items, α = .87), and Lack of Emotional Clarity (5-items, α =.64). The TMMS has three subscales: TMMS-Clarity (11items, α = .89), TMMS-Attention (13-items, α = .81), and TMMS-Repair (6-items, α =.80), all reverse scored in the current study so all ER measures could be interpreted in the same directions (i.e., higher scores reflecting maladaptive ER). The ERQ is comprised of two subscales: ERQ-Suppression (4-items, α =.79) and ERQ-Reappraisal (6-items, α = .86). ERQ-Reappraisal also was reverse scored for uniform interpretation. The MEAQ has six subscales; however, only items from the Distress Aversion (MEAQ-DA) subscale (13-items, α = .89) were administered (a) due to the length of the full measure (62 items), and (b) because MEAQ-DA has the strongest associations with the higher-order construct of experiential avoidance (Gámez et al., 2011). See Supplemental Table 1 for the correlations, means, and standard deviations of the ER indicators.

EMOTIONAL DISORDER DIMENSIONS

Similar to our prior structural regression studies of the emotional disorders (e.g., Rosellini & Brown, 2010; Brown & Naragon-Gainey, 2013), a confirmatory measurement model was developed for five emotional disorder symptom dimensions and Neuroticism using a combination of self-report questionnaires and ADIS-5 clinical ratings. Measures were selected based on their (good) performance in previous confirmatory measurement models. See Supplemental Table 2 for the correlations, means, and standard deviations among the indicators of emotion disorder symptoms, and Supplemental Table 3 for the correlations with ER indicators.

Agoraphobia/Panic (AG/P)

Indicators of AG/P were the Interoceptive (8-items, α = .82) and Agoraphobia (9-items, α = .84) subscales of the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (APPQ; Rapee et al., 1994), along with a sum composite of ADIS-5 avoidance ratings for 25 agoraphobic situations (e.g., driving, crowds, theaters, leaving the house).

Social Anxiety (SOC)

The Social Anxiety subscale of the APPQ (10-items, α = .91; Rapee et al. 1994), the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (20-items, α = .95; Mattick & Clarke, 1998), and a sum composite of ADIS-5 fear ratings for 15 social situations (e.g., public speaking, talking on the phone, initiating conversations) were used to define the SOC latent variable.

Generalized Anxiety/Worry (GAW)

Indicators of GAW included sum composites of ADIS-5 excessiveness ratings for eight worry areas (e.g., minor matters, work/school, health), ADIS-5 severity ratings for the six associated symptoms of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder (e.g., restlessness, sleep difficulties, irritability, muscle tension), and an 8-item self-report scale developed for the current study to assess the frequency of worry (in the past 6 months) in the same eight domains as in the ADIS-5. Although internal consistency was acceptable (α = .74), the 8-item worry questionnaire is a new measure and thorough psychometric validation is forthcoming. This limitation was addressed in part by operationalizing the GAW construct using multiple indicators (i.e., a latent variable theoretically free of measurement error). In support of its convergent validity, the 8-item worry questionnaire was moderately correlated with the composite ADIS-5 ratings for GAD worries (r = .50) and associated symptom ratings (r = .48; see Supplemental Table 2).

Obsessions/Compulsions (OC)

The OC latent variable was defined using sum composites of ADIS-5 distress ratings for nine obsessions/intrusive thoughts (e.g., contamination, nonsensical thoughts, aggressive urges), ADIS-5 frequency ratings for five compulsions (e.g., checking, cleaning, counting), and the 3-item Neutralization subscale of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI, α = .82; Foa et al., 2002).

Depression (DEP)

Indicators of DEP were the Depression subscale (7-items, α = .91) of the 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), the 10-item cognitive/affective subscale of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (i.e., capturing features specific to unipolar mood disorders, items 1–9 and 13, α = .87; Beck et al., 1996), and a sum composite of ADIS-5 severity ratings for the nine DSM-5 criteria for a major depressive episode. As separate ADIS-5 severity ratings are made for appetite/weight increase versus decrease, insomnia versus hypersomnia, and psychomotor agitation versus retardation, only the higher rating of each pair were used to form the ADIS-Depression composite.

Neuroticism

A Neuroticism latent variable was constructed using the neuroticism subscales from the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (12-items, α = .84; Costa & MacCrae,1992) and Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (12-items,a =.76; Eysenck& Eysenck,1975).

DATA ANALYSIS

Data analysis occurred in three steps. First, exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) with geomin rotation was used to develop a measurement model for ER using the DERS, TMMS, ERQ, and MEAQ-DA subscales. We used an exploratory rather than confirmatory framework because we are unaware of prior attempts to develop an ER measurement model using several ER questionnaires. ESEM was used rather than traditional exploratory factor analysis (a) in order to inspect the models for localized area of strain (i.e., standardized residuals, modification indices), and (b) given our subsequent goal of evaluating the associations between ER and emotional disorder dimensions using structural equation modeling.

Second, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to develop a measurement model for Neuroticism and the five emotional disorder constructs (AG/P, SOC, GAW, OC, DEP). Neuroticism was included in the confirmatory measurement model with the emotional disorder constructs (rather than the ESEM measurement model for ER) because Mplus does not permit hierarchical structural regression modeling using subsets of ESEM factors; paths must be estimated for all exogenous ESEM factors included in a structural model. In other words, including Neuroticism in the ESEM measurement model would have precluded estimation of structural paths between the ER and emotional disorder dimensions without holding Neuroticism constant (i.e., evaluating R2 using only ER dimensions).

Third, the best fitting ESEM (Step 1) and CFA (Step 2) models were combined into a hybrid ESEM-CFA measurement model that included the ER dimensions, the five emotional disorder symptom dimensions, and Neuroticism. Incremental associations were evaluated by regressing the emotion disorder dimensions onto the dimensions of ER and Neuroticism (i.e., adding structural paths to the model). A hierarchical regression approach was used such that the emotional disorder dimensions were regressed onto (a) only the Neuroticism latent variable (with all correlations with the ER latent variables freely estimated; Model 1), (b) only the ER latent variables (with all correlations with Neuroticism freely estimated; Model 2), and (c) both Neuroticism and the ER dimensions (to evaluate the incremental associations; Model 3).

For all analysis steps, the raw data were analyzed using Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) with robust (full information) maximum likelihood minimization functions to account for missing and non-normal data (e.g., nonnormality of symptom severity indicators due to differential disorder prevalence). Model fit was examined using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its test of close fit (C-Fit), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Multiple goodness-of-fit indices were evaluated to examine various aspects of model fit (i.e., absolute fit, parsimonious fit, fit relative to the null model; Brown, 2015). Conventional guidelines for acceptable model fit include RMSEA near or below 0.06, TLI and CFI close to or above .95, and SRMR near or below .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

EMOTION REGULATION MEASUREMENT MODEL

One through six factor ESEM solutions were evaluated by inspecting the completely standardized factor loadings along with the item-level content of each ER subscale (see Supplemental Table 4 for representative items). Model fit was poor for the one-, two-, and three-factor solutions (see Supplemental Results and Supplemental Table 5). The five-factor solution was not interpretable, while the six-factor solution did not converge. In comparison, the four-factor solution fit the data well, χ2(24) = 98.67, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.06, TLI = 0.95, CFI = .98, SRMR = .02, and consisted of interpretable factors, including factors that closely resembled Stanton et al.’s (2016) Problematic Responses and Poor Recognition (described further below). There was a salient modification index (MI = 16.70) between DERS-Awareness and TMMS-Attention, likely due to both subscales including questions asking about “attention” to feelings (e.g., DERS-Awareness: “I pay attention to how I feel”, TMMS-Attention: “I pay a lot of attention to how I feel”). The four-factor model was re-estimated to freely estimate the error covariance between these indicators, which improved model fit, χ2(23) = 78.76, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.05, TLI = 0.96, CFI = .99, SRMR = .02. The four-factor model otherwise did not have interpretable localized areas of strain.

Completely standardized factor loadings from the final four-factor solution are presented in Table 1. Factor 1 was defined (loadings ≥.40) by the same four DERS subscales that loaded onto the Stanton et al. (2016) Problematic Responses factor (Limited Regulation Strategies, Non-Acceptance, Impulse Control Difficulties, Difficulty with Goal Directed Behavior), along with MEAQ-DA. We also labeled this factor Problematic Responses as these subscales each include items assessing negative beliefs, responses, and reactions surrounding emotional experiences (e.g., feeling bad/weak/out of control when experiencing emotion; avoiding stress/pain at all costs). DERS-Clarity and TMMS-Clarity loaded strongly onto Factor 2, along with a moderate loading for DERS-Awareness. This factor is consistent with Stanton and colleague’s Poor Recognition (DERS-Clarity and Awareness), although they found DERS-Awareness to have the strongest factor loading. Accordingly, Factor 2 was labeled Poor Emotional Recognition/Clarity (“Poor Recognition/Clarity”) as these subscales include questions assessing one’s ability to acknowledge, attend to, and understand emotions.

Table 1.

Completely Standardized Factor Loadings and Intercorrelations From the Four-Factor ESEM Solution

| Subscale | Problematic Responses | Poor Recognition/Clarity | Negative Thinking | Emotional Inhibition/Suppression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| MEAQ-Distress Aversion | .47 | .02 | −.02 | .13 |

| TMMS-Repair | .15 | −.02 | .74 | .04 |

| TMMS-Clarity | .02 | .78 | .05 | .10 |

| TMMS-Attention | .10 | .15 | .13 | .48 |

| DERS-Non-Acceptance | .70 | .01 | −.00 | .14 |

| DERS-Difficulty Goal Directed Behavior | .58 | .01 | .05 | −.07 |

| DERS-Impulse Control Difficulties | .64 | .16 | −.01 | −.15 |

| DERS-Lack of Emotional Awareness | .17 | .44 | .08 | .07 |

| DERS-Limited Regulation Strategies | .81 | −.01 | .22 | .02 |

| DERS-Lack of Emotional Clarity | .06 | .87 | −.07 | −.04 |

| ERQ-Reappraisal | .01 | .05 | .68 | −.13 |

| ERQ-Suppression | .08 | .01 | −.03 | .80 |

| Correlations | ||||

| Problematic Responses | − | |||

| Poor Recognition/Clarity | .47*** | − | ||

| Negative Thinking | .40*** | .39*** | − | |

| Emotional Inhibition/Suppression | .09* | .41*** | .26*** | − |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .001. The model fit the data well, χ2(23) = 78.76, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.05, TLI = 0.96, CFI = .99, SRMR = .02). Factor loadings >.30 are bolded (all were significant p < .001). ESEM = exploratory structural equation modeling; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; TMMS = Trait Meta Mood Scale; ERQ = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; MEAQ = Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire.

Factor 3 was defined primarily by TMMS-Repair and ERQ-Reappraisal and was labeled Negative and Inflexible Thinking (“Negative Thinking”) because these subscales assess the extent to which individuals use strategies to appraise and reappraise situations positively or negatively. Factor 4 consisted of a very strong loading for ERQ-Suppression and moderate loading for TMMS-Attention. Factor 4 was labeled Emotional Inhibition and Expressive Suppression (“Emotional Inhibition/Suppression”) because both subscales include items assessing how much one acts on, expresses (or suppresses), and values emotions. The four ER factors had significant positive intercorrelations (Table 1).

EMOTIONAL DISORDER AND NEUROTICISM MEASUREMENT MODEL

The initial confirmatory measure model for AG/P, SOC, GAW, OC, DEP, and Neuroticism provided marginally acceptable fit, χ2(104) = 814.45, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.08, TLI = 0.90, CFI = 0.92, SRMR = .06. Modification indices suggested fit would be improved if correlated residuals were freely estimated between subscales derived from a single measure but specified to load on different factors. For example, the highest MI among the self-report indicators was between the APPQ-Social and APPQ-Agoraphobia subscales (MI = 57.33). In addition, high MIs were estimated for ADIS-5 indicators specified to load on different factors, with the highest between the MDD symptom composite and GAD associated symptom composite ratings (MI = 65.36). The model thus was re-estimated to freely correlate all residuals derived from a single measure but specified to load on different factors. This model provided acceptable fit, χ2(83) = 428.72, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.06, TLI = 0.94, CFI = .96, SRMR = .06. All factor loadings were large (>.60) and statistically significant (ps < .001, see Supplemental Table 6). All latent symptom dimensions had significant positive intercorrelations (ϕs = .08 – .51, p < .05), except for SOC and OC (ϕ = .04, p = .235; Supplemental Table 6). Neuroticism had significant positive associations with all five emotional disorders (ps < .001), with the strongest associations with DEP (ϕ = .80), SOC (ϕ = .61), and GAW (ϕ = .60).

DIFFERENTIAL AND INCREMENTAL ASSOCIATIONS

The ER (ESEM) and emotional disorder (CFA) measurement models were combined into a hybrid ESEM-CFA model, which fit the data well, χ2(286) = 920.263, p < .001, RMSEA = 0.04, TLI = 0.94, CFI = .96, SRMR = .04 (factor loadings presented in Supplemental Table 7). The completely standardized zero-order correlations between the four ER dimensions, Neuroticism, and five emotional disorders are presented in Table 2. All four ER dimensions had moderate-to-strong significant positive associations with Neuroticism, with a particularly strong association between Problematic Responses and Neuroticism (ϕ = .77, p < .001; see also Supplemental Results). Problematic Responses and Poor Recognition/Clarity also had significant positive associations with all five emotional disorder dimensions (ϕs = .08-.69, ps < .05). In comparison, Negative Thinking had significant positive associations only with SOC, GAW, and DEP (ϕs = .32-.66, ps < .001), and Emotional Inhibition/Suppression only with SOC (ϕ = .46, p < .001) and DEP (ϕ = .30, p < .001).

Table 2.

Correlations Between Dimensions of Emotional Regulation and Dimensions of Emotional Disorders and Neuroticism

| Problematic Responses | Poor Recognition/Clarity | Negative Thinking | Emotional Inhibition/Suppression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Neuroticism | .77***a | .50***a | .63***b | .22***c |

| Agoraphobia/Panic | .23***e | .13**d | .06e | −.03e |

| Social Anxiety | .42***d | .37***c | .39***c | .46***a |

| Generalized Anxiety/Worry | .52***c | .32***c | .32***d | .07d |

| Obsessions/Compulsions | .13***f | .08*d | .04e | −.06e |

| Depression | .69***b | .45***b | .66***a | .30***b |

Note. Correlations in the same column but with different superscripts differ significantly in magnitude (p < .05).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Differential associations of the ER dimensions with the emotional disorder dimensions and Neuroticism were evaluated using a z-test procedure (Meng, Rosenthal, & Rubin, 1992). Problematic Responses and Poor Recognition/Clarity were more strongly associated with DEP than the other four emotional disorder dimensions (zs = 3.17–16.87, ps < .002), but had even stronger associations with Neuroticism than DEP (zs = 6.46 and 3.40, respectively, ps < .001). Negative Thinking was more strongly associated with DEP than Neuroticism (z = 2.23, p < .05), though the difference in associations was small (ϕ = .66 versus .63). Negative Thinking also was more strongly associated with DEP than the other four emotional disorder symptom dimensions (zs = 11.44 – 18.25, ps < .001). Emotional Inhibition/Suppression was more strongly associated with SOC than Neuroticism or the other emotional disorder dimensions (zs = 6.06–13.58, ps < .001).

Structural paths were added to the ESEM-CFA measurement model. In Model 1 (Neuroticism paths only), the paths from Neuroticism to the five emotional disorder dimensions were all positive and significant (γs = .13-.81, ps < .01, see Table 3). In Model 2 (ER paths only), the paths from Problematic Responses to all five emotional disorder dimensions were positive and significant (γs = .12-.50, ps < .01). Negative Thinking also had significant direct effects on SOC (γ = .16, p < .001), GAW (γ = .10, p < .05), and DEP (γ = .41, p < .001), as did Emotional Inhibition/ Suppression on SOC (γ = .40, p < .001) and DEP (γ = .16, p < .001). In comparison, Poor Recognition/Clarity did not explain significant variance in any of the emotional disorder dimensions beyond the other ER dimensions (γs = −.01-.09, ps = .06-.95). Although the zero-order relationship was nonsignificant, the partial regression path of Emotional Inhibition/Suppression on OC path was statistically significant but negatively signed (γ = −.09, p < .05), indicating that more emotional expression was associated with more severe OC symptoms.

Table 3.

Differential and Incremental Associations of Dimensions of Emotion Regulation and Neuroticism With Emotional Disorders

| Model/Structural Paths | Agoraphobia/Panic |

Social Anxiety |

Generalized Anxiety/Worry |

Obsessions/Compulsions |

Depression |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | γ | SE | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Model 1: Neuroticism → | ||||||||||

| Neuroticism | .22*** | .03 | .62*** | .02 | .62*** | .03 | .13** | .04 | .81*** | .01 |

| R 2 | .05** | .02 | .39*** | .03 | .38*** | .03 | .02 | .01 | .66*** | .02 |

| Model 2: Emotion Regulation → | ||||||||||

| Problematic Responses | .22*** | .05 | .32*** | .05 | .43*** | .04 | .12** | .05 | .50*** | .04 |

| Poor Recognition/Clarity | .07 | .05 | −.01 | .05 | .09 | .05 | .07 | .04 | −.01 | .04 |

| Negative Thinking | −.05 | .04 | .16*** | .04 | .10* | .04 | −.02 | .04 | .41*** | .04 |

| Emotional Inhibition/Suppression | −.07 | .05 | .40*** | .05 | −.03 | .05 | −.09* | .04 | .16*** | .03 |

| R2 | .06** | .02 | .38*** | .03 | .28*** | .03 | .03* | .01 | .66*** | .03 |

| Model 3: Neuroticism & Emotion Regulation → | ||||||||||

| Neuroticism | .19* | .08 | .67*** | .07 | .61*** | .08 | .12 | .08 | .46*** | .05 |

| Problematic Responses | .11 | .07 | −.07 | .06 | .08 | .07 | .05 | .06 | .23*** | .05 |

| Poor Recognition/Clarity | .06 | .05 | −.06 | .05 | .04 | .05 | .06 | .04 | −.04 | .04 |

| Negative Thinking | −.11* | .06 | −.07 | .05 | −.10* | .05 | −.06 | .06 | .25*** | .04 |

| Emotional Inhibition/Suppression | −.08 | .05 | .36*** | .04 | −.06 | .04 | −.10* | .04 | .13*** | .03 |

| R 2 | .07*** | .02 | .51*** | .03 | .39*** | .03 | .03* | .01 | .72*** | .02 |

| AR2 vs. Model 1 | .02 | .12 | .01 | .01 | .06 | |||||

| AR2 vs. Model 2 | .01 | .13 | .11 | .00 | .06 | |||||

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001. γ = completely standardized path coefficient. The models provided acceptable fit, χ2(286) = 920.26, p < .001, RMSEA = .04, TLI = 0.94, CFI = .96, SRMR = .04. In Model 1, the five emotional disorder dimensions were regressed onto neuroticism while the four emotion regulation dimensions were freely correlated with neuroticism and the emotional disorder dimensions. In Model 2, the emotional disorder dimensions were regressed onto the emotion regulation dimensions while neuroticism was freely correlated with the four emotional regulation dimensions. In Model 3, five emotional disorder dimensions were regressed onto neuroticism and the emotion regulation dimensions simultaneously.

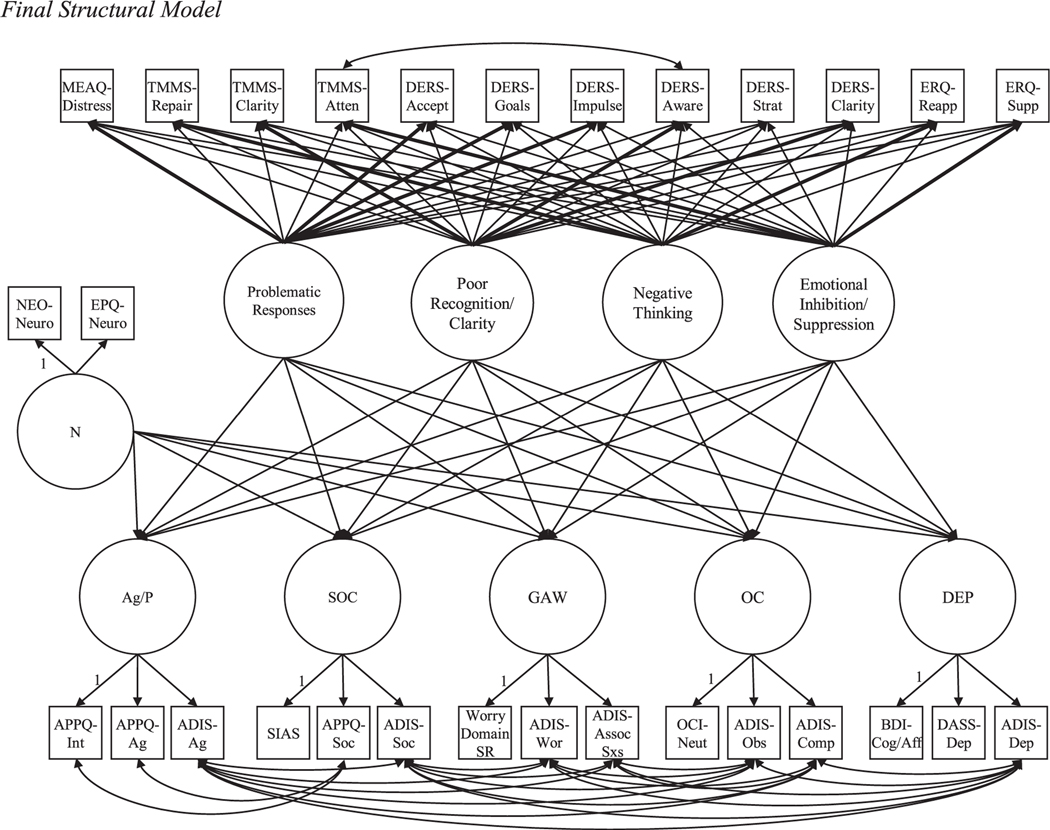

In Model 3, which included structural paths from both Neuroticism and the ER facets to the emotional disorder dimensions (see Figure 1), significant paths remained for (a) Problematic Responses → DEP (γ = .23, p < .001), (b) Negative Thinking → DEP (γ = .25, p < .001), and (c) Emotional Inhibition/Suppression → DEP (γ = .13, p < .001), → SOC (γ = .36, p < .001), and ? OC (γ = −.10, p < .05). Other paths that were significant in Model 2 either were no longer significant (e.g., Problematic Responses → AG/P, SOC, GAW, and OC, ps = .14-.42), or became significantly inversely associated with the emotional disorder dimensions (Negative Thinking → AG/ P, γ = −.11, p < .05; Negative Thinking → GAW, γ = −.10, p < .05), when holding Neuroticism constant. In comparison, the paths from Neuroticism to the emotional disorder dimensions remained (cf. Model 1) positive and significant, except for Neuroticism → OC, which approached significance in Model 3 (γ = .11, p = .15). Inclusion of the ER → emotional disorder paths in Model 3 resulted in an R2 change (versus the Neuroticism only/Model 1) of .01 (GAW, OC) to .12 (SOC), which were small to borderline medium effects (f2 = .01 to .14) per Cohen (1988).

FIGURE 1. Final Structural Model.

Note. The figure depicts the final structural model (Model 3). In the emotion regulation portion of the model, bolded paths indicate factor loadings >.30. N = neuroticism; AG/P = agoraphobia/panic; SOC = social anxiety; GAW = generalized anxiety/worry; OC = obsessions/compulsions; DEP = depression; NEO = NEO-Five Factor Inventory; EPQ = Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; APPQ = Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire; ADIS = Anxiety and Related Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-5; SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; OCI = Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; MEAQ Distress = MEAQ-Distress Aversion; TMMS-Atten = TMMS-Attention; DERS-Accept = DERS-Non-Acceptance; DERS-Goals = DERS-Difficulty Goal Directed Behavior; DERS-Impulse = DERS-Impulse Control Difficulties; DERS-Aware = DERS-Lack of Emotional Awareness; DERS-Strat = DERS-Limited Regulation Strategies; DERS-Clarity = DERS-Lack of Emotional Clarity; ERQ-Reapp = ERQ-Reappraisal; ERQ-Supp = ERQ-Suppression; NEO-Neuro = NEO-Neuroticism; EPQ-Neuro = EPQ-Neuroticism; APPQ-Int = APPQ-Interoceptive; APPQ-Ag = APPQ-Agoraphobia; ADIS-Ag = ADIS-Agoraphobia; APPQ-Soc = APPQ-Social; ADIS-Soc = ADIS-Social Fears; Worry Domain SR = Worry Domains Self-Report; ADIS-Wor = ADIS-Worry Excessiveness; ADIS-Assoc Sxs = ADIS-GAD Associated Symptoms; OCI-Neut = OCI-Neutralization; ADIS-Obs = ADIS-Obsessions; ADIS-Comp = ADIS-Compulsions; BDI-Cog/Aff = BDI-Cognitive/Affective; DASS-Dep = DASS-Depression; ADIS-Dep = ADIS-Depression.

Discussion

The best-fitting ESEM measurement model included latent variables representing distinct dimensions of general emotional awareness (Poor Recognition/Clarity) and problematic responses and reactions to emotions (Problematic Responses). These dimensions were similar to those identified by Stanton et al. (2016) using only DERS subscales (see also Wiltgen et al., 2018), but with the addition of MEAQ-DA loading onto Problematic Responses and TMMS-Clarity loading onto Poor Recognition/Clarity. Consistent with conceptual models empathizing dispositional ER abilities (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), the Problematic Responses dimension appears to reflect the broad tendency for co-occurring emotional nonacceptance and maladaptive cognitive-behavioral responses (e.g., negative beliefs about emotions). The Poor Recognition/Clarity dimension is in line with Gross’s (2015) extended process model of ER, which identifies emotional awareness (i.e., attention) as one of the basic steps necessary to engage in ER and specific ER strategies.

By developing a measurement model using several additional ER measures, we operationalized two additional latent variables reflecting circumscribed ER strategies: Negative Thinking (i.e., lack of reappraisal) and Emotional Inhibition/Suppression. These dimensions are in line with key ER strategies described in Gross’ (2015) extended process model and which are posited to occur subsequent to emotional awareness, (a) modifying cognitive appraisals (e.g., reappraising negative thoughts), and (b) response modulation via expressive suppression. Indeed, Negative Thinking and Emotional Inhibition/Suppression have been frequently studied as maladaptive transdiagnostic ER strategies used by individuals with emotional disorders (Aldao et al., 2010; D’Avanzato et al., 2013; Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Garnefski et al., 2001; Sloan et al., 2017).

Although significant zero-order (positive) associations were estimated between Neuroticism and the four ER dimensions, the magnitude of correlations (e.g., < .80) indicated that the dimensions were distinct (i.e., discriminant validity). Significant associations also were estimated between Neuroticism and all five emotional disorder symptom dimensions (Model 1). This is not surprising given the well-established literature documenting the transdiagnostic influence of Neuroticism on emotional disorder onset, severity, and course (Brown et al., 1998; Khan et al., 2005; Malouff et al., 2005; Naragon-Gainey et al., 2013). Attesting to the relevance of Neuroticism in the severity and expression of emotional disorders, standardized regression coefficients generally were of similar sizes and significance regardless of holding the ER dimensions constant.

Consistent with Stanton et al. (2016), although zero-order correlations between Poor Recognition/ Clarity and the emotional disorder constructs were significant, associations were not significant holding the other ER dimensions constant. These findings suggest that poor emotional awareness is associated with problematic ER responses and reactions and maladaptive cognitive and behavioral ER strategies (see moderate correlations with the three other ER factors) but may not directly influence emotional disorder symptom severity or expression. Along these lines, there is evidence that maladaptive ER strategies may mediate the association between poor emotional awareness and emotional disorder symptoms (e.g., Boden & Thompson, 2015).

Problematic Responses had significant associations with all five emotional disorder symptoms dimensions (both zero-order associations and Model 2 paths), but only incrementally predicted DEP when holding Neuroticism constant (Model 3). This indicates that emotional nonacceptance and other general maladaptive responses may exacerbate depression symptoms, but not anxiety symptoms, in ways that are distinct from general emotional reactivity. Research is needed to replicate the unique association between Problematic Responses and DEP and to identify underlying mechanisms. One plausible interpretation is that nonacceptance and maladaptive responses may lead to rumination or feelings of hopelessness (more so than neuroticism), which in turn may worsen depressed mood and anhedonia (but not social anxiety, worry, panic, or obsessions). Along these lines, research has found DERS-Limited ER Strategies (the strongest loading indicator of Problematic Responses) to predict rumination and hopelessness (Miranda et al., 2013).

Our results are somewhat at odds with Stanton et al. (2016), who found Problematic Responses (defined using the DERS) to incrementally predict a range of different self-reported internalizing disorder symptoms (not just DEP). However, it is noteworthy that their Problematic Responses dimension only was associated with clinician-made diagnoses of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, but not GAD, SAD, OCD, panic disorder, or agoraphobia, when holding neuroticism constant. Accordingly, the divergence in results could be due to differences in sampling (e.g., community versus clinical), measurement (e.g., relying on observed scales/diagnoses versus a measurement model developed from both self-reported and clinician-made ratings), or modeling (e.g., estimating a distinct regression model for each outcome versus a single structural model). Additionally, our use of a clinical sample with a higher degree of general distress may have contributed to the (strong) estimated association between Problematic Responses and Neuroticism (i.e., due to mood-state distortion; Clark et al., 2003).

The zero-order correlations and Model 2 structural paths suggested meaningful positive associations between Negative Thinking and SOC, GAW, and DEP, but negligible associations with AG/P and OC. Further, only the Negative Thinking → DEP path remained positive and significant when holding Neuroticism constant in Model 3. This underscores the relevance of Negative Thinking for DEP, consistent with meta-analytic findings that negative thinking (e.g., lack of reappraisal and rumination) is most pronounced among individuals with depression (cf. other forms of psychopathology; Aldao et al., 2010). In comparison, a suppressor effect occurred for SOC and GAW (see also AG/P); the paths from Negative Thinking became negative after accounting for the variance explained by Neuroticism. Other studies have found associations between negative thinking and anxiety symptoms but did not control for Neuroticism. (e.g., Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Wahl et al., 2019). Accordingly, Negative Thinking may be more strongly associated with some types of emotional disorder symptoms than others, but associated with some anxiety symptom dimensions primarily due to overlap with general emotional reactivity.

Emotional Inhibition/Suppression was the only ER facet with both significant zero-order and incremental associations with more than one emotional disorder symptom dimension (SOC, DEP). The significant Emotional Inhibition/Suppression → SOC and Emotional Inhibition/Suppression → DEP paths are consistent with research demonstrating that individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders (Aldao et al., 2010), especially those with social anxiety disorder (Blalock et al., 2016; D’Avanzato et al., 2013), tend to use emotional suppression strategies. Although the Emotional Inhibition/Suppression → OC paths were significant in Models 2 and 3 (i.e., suppression associated with less severe OC), the small magnitude of these paths and R2 suggest relatively weak associations (see also nonsignificant zero-order correlation).

IMPLICATIONS FOR ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT

Our findings have implications for emotional disorder assessment and treatment. All four ER dimensions had significant associations with multiple emotional disorder symptoms (i.e., zero-order associations or in Model 2 paths). These findings attest to the importance of ER in the expression of emotional disorder psychopathology and are consistent with arguments that ER should be assessed in clinical and research settings (e.g., integrating ER in the in the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework, see Fernandez et al., 2016). However, our Model 3 results also call into question the incremental importance of assessing (by self-report) dispositional ER abilities such as general Problematic Responses and Poor Recognition/Clarity (defined predominately by DERS subscales) after accounting for general emotional reactivity. Three of the four ER dimensions had considerable associations with Neuroticism (e.g., rs > .50 for Problematic Responses, Negative Thinking, and Poor Recognition/Clarity). In other words, some of the influence of ER dimensions on emotional disorder symptom severity and expression is likely due to the overlap between ER and neuroticism rather than mechanisms (variance) unique to ER. Depending on competing demands (e.g., time limitations), it may be more parsimonious to assess neuroticism than a range of ER dimensions.

Nevertheless, there may be value in assessing ER dimensions for the purposes of emotional disorder treatment planning, especially if neuroticism will not be assessed. For instance, acceptance-based interventions might be indicated for individuals with elevated Problematic Responses as this factor was defined predominately by emotional nonacceptance and negative beliefs about coping abilities (i.e., lack of ER strategies). Problematic Responses had transdiagnostic associations with all five emotional disorder symptom dimensions in Model 2, and treatment outcome research suggests that acceptance-based intervention are effective in reducing a range of different emotional disorder symptoms (Newby et al., 2015).

Our results also suggest that it may be helpful to assess specific cognitive and behavioral ER strategies (e.g., lack of reappraisal, suppression) that have incremental or differential associations with specific emotional disorder symptom dimensions. For instance, assessing Emotional Inhibition/Suppression could aid in determining SOC and DEP severity, or distinguishing SOC and DEP from other forms of emotional disorder psychopathology. Patients with high SOC or DEP may specifically benefit from cognitive flexibility and exposure exercises focused on beliefs and behaviors associated with Emotional Inhibition/Suppression (e.g., “emotion assertiveness” exposures). Likewise, our results indicate that it may be useful to assess Negative Thinking and implement associated cognitive flexibility interventions among patients with elevated SOC or GAW, but especially relevant for patients with elevated DEP.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Four limitations and associated future research directions are noteworthy. First, sample characteristics may limit the generalizability of the findings (e.g., predominately Caucasian sample). Information about socioeconomic status (e.g., income and education) was not recorded in study databases. Additionally, the sample consists of participants from a single outpatient mental health clinic that specializes in the treatment of anxiety and related disorders. Our results may not generalize to all outpatient samples (e.g., with different types of psychopathology). Replication in other clinical samples is needed.

Second, the study relied on self-report measures of ER. There are challenges in assessing ER, or any emotional disorder trait or mechanism, by self-report. For example, individuals may lack insight (e.g., alexithymia), or their responses may be influenced by mood-state distortion (i.e., ER measurement influenced by current symptoms/distress). Further, Gross’s (2015) extended process model indicates ER efficacy and strategy selection depends on numerous contextual factors, which was not assessed through these retrospective self-reports. Future research should aim to develop an expanded measurement model using a combination of self-reported, fine-grained behavioral (e.g., ecological momentary assessment or Emotion Regulation Interview; Werner et al., 2011), and neurophysiological measures of ER (e.g., late positive potential; Moran et al., 2013).

Third, we did not assess all ER strategies that may have transdiagnostic associations with the emotional disorders (e.g., behavioral avoidance, rumination, thought suppression; Aldao et al., 2010; Sloan et al., 2017). Efforts to develop an expanded ER measurement model should include measures of other ER strategies that may be distinct constructs from those studied here and thus incrementally predict emotional disorder symptom dimensions beyond Neuroticism. For instance, behavioral avoidance (e.g., MEAQ-Behavioral Avoidance; Gámez et al., 2011) may be particularly relevant in predicting severity of anxiety symptoms (e.g., behavioral avoidance is a criterion of several anxiety disorders). Further, additional measurement model development is needed to clarify if the maladaptive ER strategy of rumination (e.g., Ruminative Response Scale; Treynor et al., 2003) should be conceptualized as a construct that is distinct from the Negative Thinking construct operationalized here (see Hong & Cheung, 2015).

Fourth, the cross-sectional design precluded firm conclusions about directionality of the relationships between the ER and emotional disorder dimensions (e.g., if maladaptive ER strategies cause emotional disorder symptoms or vice versa). Given the possible influence of mood-state distortion on the measurement of ER, and the strong correlations between some ER dimensions and Neuroticism, it could be beneficial to conduct prospective studies within a trait-state-occasion (TSO) modeling framework (Cole, Martin, & Steiger, 2005). Specifically, TSO could be used to parse the variance of neuroticism and ER dimensions into stable (trait/time-invariant) and transient sources (time-variant/state), which could be evaluated as differential predictors of emotional disorder trajectory (e.g., symptom chronicity). TSO modeling permits more robust statistical tests and effect sizes estimates compared to single indicators or traditional longitudinal measurement model (Prenoveau, 2015) and could further elucidate the unique associations between ER and emotional disorder symptom dimensions.

Within the context of these limitations, this is the first study to (a) develop an ER measurement model using several leading ER questionnaires, (b) evaluate the multivariate structural associations among several ER and emotional disorder symptom dimensions, and (c) determine the contribution of ER in predicting emotional disorder symptom severity above and beyond neuroticism in a large clinical sample. Our results suggest that there are significant associations between several facets of ER and emotional disorder symptom dimensions, but that the incremental contribution of ER dimensions in predicting symptom severity may be circumscribed and limited after accounting for neuroticism. In some situations, it may be more parsimonious to assess general emotional reactivity than a range of different self-reported ER dimensions. At the same time, the development of expanded and more refined ER measurement models (e.g., using other methods to assess ER; adjusting for mood-state distortion) is needed to better understand the unique influences of various ER dimensions on the expression and severity of emotional disorder symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant MH039096 from the National Institute of Mental Health to T.A. Brown. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.11.003.

References

- Aldao A (2013). The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2010). Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48), 974–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Wirtz CM, Svaldi J, & Hofmann SG (2014). Emotion regulation predicts symptoms of depression over five years. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 57, 13–20. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock DV, Kashdan TB, & Farmer AS (2016). Trait and daily emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40, 416–425. 10.1007/s10608-015-9739-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, & Thompson RJ (2015). Facets of emotional awareness and associations with emotion regulation and depression. Emotion, 15, 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, & Barlow DH (2014). Anxiety and related disorders interview schedule for DSM–5 (ADIS-5L): Client interview schedule (Lifetime version). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, & Barlow DH (1998). Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 179–192. 10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, & Campbell LA (2001). Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, & Naragon-Gainey K (2013). Evaluation of the unique and specific contributions of dimensions of the triple vulnerability model to the prediction of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Behavior Therapy, 44, 277–292. 10.1016/j.beth.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Ellard KK, & Barlow DH (2014). Emotion regulation in anxiety disorders. In Gross JJ(Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 393–412). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Vittengl J, Kraft D, & Jarrett RB (2003). Separate personality traits from states to predict depression. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 152–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.) Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin NC, & Steiger JH (2005). Empirical and conceptual problems with longitudinal trait-state models: Introducing a trait-state-occasion model. Psychological Methods, 10, 3–20. 10.1037/1082989X.10.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & MacCrae RR (1992). Revised NEO personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- D’Avanzato C, Joormann J, Siemer M, & Gotlib IH (2013). Emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: Examining diagnostic specificity and stability of strategy use. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37, 968–980. 10.1007/s10608-013-9537-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, & Watkins ER (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1, 192–205. 10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, & Eysenck SBG (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Junior and Adult). Hodder and Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez KC, Jazaieri H, & Gross JJ (2016). Emotion regulation: A transdiagnostic perspective on a new RDoC domain. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40, 426–440. 10.1007/s10608-016-9772-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, & Salkovskis PM (2002). The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment, 14, 485–496. 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gámez W, Chmielewski M, Kotov R, Ruggero C, & Watson D (2011). Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The multidimensional experiential avoidance questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 23, 692–713. 10.1037/a0023242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, & Spinhoven P (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems.Personality and IndividualDifferences,30, 1311–1327. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Lee I, Ziv M, Jazaieri H, Heimberg RG, & Gross JJ (2014). Trajectories of change in emotion regulation and social anxiety during cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, 7–15. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 1–26. 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & Jazaieri H (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 387–401. 10.1177/2167702614536164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong RY, & Cheung M-W-L (2015). The structure of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression and anxiety: Evidence for a common core etiologic process based on a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychological Science, 3, 892–912. 10.1177/2167702614553789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jazaieri H, Morrison AS, Goldin PR, & Gross JJ (2014). The role of emotion and emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 531. 10.1007/s11920-014-0531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, & Quinn ME (2014). Cognitive processes and emotion regulation in depression. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 308–315. 10.1002/da.22264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Jacobson KC, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, & Kendler KS (2005). Personality and comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 190–196. 10.1192/bjp.186.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64, 241–256. 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, & Lovibond SH (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson EB, & Schutte NS (2005). The relationship between the five-factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 101–114. 10.1007/s10862-005-5384-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, & Clarke JC (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 455–470. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XL, Rosenthal R, & Rubin DB (1992). Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Tsypes A, Gallagher M, & Rajappa K (2013). Rumination and hopelessness as mediators of the relation between perceived emotion dysregulation and suicidal ideation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37, 786–795. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadkhani P, Abasi I, Pourshahbaz A, Mohammadi A, & Fatehi M (2016). The role of neuroticism and experiential avoidance in predicting anxiety and depression symptoms: Mediating effect of emotion regulation. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 10(3). 10.17795/ijpbs-5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran TP, Jendrusina AA, & Moser JS (2013). The psychometric properties of the late positive potential during emotion processing and regulation. Brain Research, 1516, 66–75. 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Roelofs J, Rassin E, Franken I, & Mayer B (2005). Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1105–1111. 10.1016/j.paid.2005.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998). Mplus 8 [Computer software]. Los Angeles: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K, Gallagher MW, & Brown TA (2013). Stable “trait” variance of temperament as a predictor of the temporal course of depression and social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 611–623. 10.1037/a0032997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby JM, McKinnon A, Kuyken W, Gilbody S, & Dalgleish T (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 91–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau JM (2015). Trait-state-occasion models. In Cautin RL & Lilienfeld SO (Eds.), The encyclopedia of clinical psychology Malden, MA (pp. 1–9). Malden, MA: John Wiley and Sons. 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Craske MG, & Barlow DH (1994) Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety, 1, 114–122. 10.1002/anxi.3070010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosellini AJ, & Brown TA (2010). The NEO Five-Factor Inventory: Latent structure and relationships with dimensions of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large clinical sample. Assessment, 18, 27–38. 10.1177/1073191110382848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, & Palfai TP (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Pennebaker JW (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, & health Washington, DC (pp. 125–154). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10182-006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saulsman LM, & Page AC (2004). The five-factor model and personality disorder empirical literature: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1055–1085. 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppes G, Suri G, & Gross JJ (2015). Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 379–405. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan E, Hall K, Moulding R, Bryce S, Mildred H, & Staiger PK (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 141–163. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton K, Rozek DC, Stasik-O’Brien SM, EllicksonLarew S, & Watson D (2016). A transdiagnostic approach to examining the incremental predictive power of emotion regulation and basic personality dimensions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(7), 960–975. 10.1037/abn0000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259. 10.1023/A:1023910315561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, & Roemer L (2007). Emotion regulation difficulties associated with the experience of uncued panic attacks: Evidence of experiential avoidance, emotional nonacceptance, and decreased emotional clarity. Behavior Therapy, 38, 378–391. 10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco C, Fernández I, Páez D, & Campos M (2006). Perceived emotional intelligence, alexithymia, coping and emotional regulation. Psicothema, 18(Suppl), 89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl K, Ehring T, Kley H, Lieb R, Meyer A, Kordon A, Heinzel CV, Mazanec M, & Schönfeld S (2019). Is repetitive negative thinking a transdiagnostic process? A comparison of key processes of RNT in depression, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and community controls. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 64, 45–53. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Shi Z, & Li H (2009). Neuroticism, extraversion, emotion regulation, negative affect and positive affect: The mediating roles of reappraisal and suppression. Social Behavior and Personality, 37, 193–194. 10.2224/sbp.2009.37.2.193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Naragon-Gainey K, Koffel E, Chmielewski M, Kotov R, Stasik SM, & Ruggero CJ (2012). Development and validation of new anxiety and bipolar symptom scales for an expanded version of the IDAS (the IDAS-II). Assessment, 19, 399–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner KH, Goldin PR, Ball TM, Heimberg RG, & Gross JJ (2011). Assessing emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder: The Emotion Regulation Interview. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33, 346–354. 10.1007/s10862-011-9225-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltgen A, Shepard C, Smith R, & Fowler JC (2018). Emotional rigidity negatively impacts remission from anxiety and recovery of well-being. Journal of Affective Disorders, 236, 69–74. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz CM, Hofmann SG, Riper H, & Berking M (2014). Emotion regulation predicts anxiety over a fiveyear interval: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 87–95. 10.1002/da.22198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.