Abstract

Tunisian pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) landraces are still growing in contrasting agro-ecological environments and are considered potentially useful for national and international breeders. Despite its genetic potential, the cropping areas of this species are still limited and scattered which increases the risk of genetic erosion. The chloroplast DNA polymorphism and maternal lineages classification of forty nine pearl millet landraces representing seven populations covering the main distribution area of this crop in Tunisia were undertaken based on informative cpSSR molecular markers. A total of 21 alleles combining to 9 haplotypes were detected with a mean value of 3.5 alleles per locus and a haplotype genetic diversity (Hd) of 0.82. The number of chloroplast haplotypes per population ranged from 1 to 4 with an average of 1.28. The haplotypes median-joining network and UPGMA analyses revealed two probable ancestral maternal lineages with a differential pearl millet seed-exchange rate between the investigated areas. Northern and Central populations presented unique genetic backgrounds while historical farmers’ practices in the South-East area resulted in the isolation of their own local landraces. The genetic evidences strongly support at least two introduction origins of pearl millet in Tunisia, one in the North and the other in the South followed by distinct local dispersal histories. Complementary in-situ and ex-situ conservation strategies taking into account the conservation of the maternal lineage cytoplasmic diversity are required. The investigated chloroplast SSRs provide useful molecular markers which could be used in further genetic studies and breeding surveys of pearl millet genetic resources.

Keywords: conservation, cpSSR, cytoplasmic DNA, maternal lineages, Pennisetum glaucum L

Introduction

Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br., 2n=2x=14, Poaceae), is a highly cross-pollinated crop with a relatively small genome (Martel et al. 1997). It is a major warm-season cereal crop cultivated both for its grain and stover used as food, forage, fuel and construction material especially in the dry lands of West and Central Africa and in South Asia (Sattler et al. 2018). Pearl millet is also cultivated in the Americas and other continents as summer pasture, cover crop and mulch component (Dias-Martins et al. 2018; Serba et al. 2017).

In Tunisia, pearl millet cultivation dates at least since the 8th century and is mainly located in the coastal areas of the North-East (Cap-Bon region), the Centre-East (Kairouan and the Sahel region) and the South-East (Medenine) of the country (Oumar et al. 2005). Despite the uniqueness of the Tunisian pearl millet gene pools in Africa as being the coastal northern continuity of the African germplasms, the cultivation areas of this species in Tunisia are decreasing significantly over the last decades and had become limited to scattered marginal farming systems. Further, there is a lack of any conservation programs in Tunisia though the local genetic resources of this species are facing looming threats of climatic changes and genetic erosion.

Due to their maternal mode of inheritance in angiosperm species, chloroplast DNA molecular markers are considered as complementary tools to nuclear molecular markers in genetic fingerprinting and analyses, with efficient contribution in the development of hybrids, genomic selection and conservation of plant genetic resources (Liu et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSR) have emerged as the markers of choice for the elucidation of chloroplast genetic diversity, maternal lineages, domestication events, historical processes of crop diffusion, the direction of hybrids crosses, molecular evolution patterns and taxonomic issues in plant species (Riahi et al. 2011; Saxena et al. 2019; Tomar et al. 2014).

Despite their previously cited interests, there is a complete lack of chloroplast SSR molecular markers for Pennisetum glaucum L. genome or the others closely related Pennisetum species and the development of cpSSRs has not been reported for this species. This limits the available molecular tools required for the genetic characterisation, conservation and improvement of this staple crop.

In the current study, the cytoplasmic DNA molecular polymorphism, chloroplast haplotypic diversity, maternal lineages characterisation and the genetic structure analyses of forty nine pearl millet landraces representing seven populations that originated from the main distribution areas of this species in Tunisia were elucidated based on six informative cpSSRs molecular markers. The obtained results will be useful for the development of efficient conservation strategies for these valuable genetic resources.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

The seeds of 49 pearl millet landraces representing seven populations were collected from various bioclimatic zones representing the main distribution areas of this species in Tunisia namely, the North-East (Cap Bon region), the Centre-East (Kairouan, Mahdia) and the South-East (Medenine) regions of the country. The geographical and bioclimatic characteristics of the studied populations are listed in the Supplementary Table S1. For each landrace accession, the leaves gathered from 10 two-week-old seedlings, germinated under controlled conditions, were pooled to serve as the source of genomic DNA using the CTAB extraction method following Zoghlami et al. (2011).

Molecular analysis

Six chloroplast microsatellites (cpSSRs) previously developed from barley (Poaceae family) genome (Provan et al. 1999) were applied to genotype the chloroplast genome of the 49 pearl millet landraces. The characteristics of the six tested cpSSR markers are listed in Table 1. The PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 10 µl consisting of 1 µl of DNA, 1 µl of PCR buffer, 0.2 µl of 25 mM dNTPs, 0.7 µl of 25 mM MgCl2, 1 µl of each primer (10 µM), 0.1 µl of Taq polymerase (0.5 U) and 5 µl of Milli-Q water. The PCR involved initial denaturation of the template DNA at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at the melting temperature of each primer for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min. PCR products were separated on 2.5% agarose gel. The alleles sizes were estimated using 100-bp DNA ladder.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studied cpSSR molecular markers and genetic diversity parameters across the 49 studied pearl millet landraces.

| Locus | Repeats | Primers (5′-3′) | Tm (°C) | Size (bp) | Na | Ne | I | h | uh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hvcppsbA | (T)8 | AATGGATAAGGTTTTTCTGCTGAATAGAAAGATTAAGAAGA | 50 | 140–170 | 3 | 2.21 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| hvcprpoA | (T)8(CTT)3 | CTCTCGTTTTAAATCCATTGCATGATCCATTTCGCGAAAATA | 60 | 120–129 | 6 | 3.21 | 1.43 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

| hvcprps12 | (T)8 | AAGAAAGGGCTCCGGTGTATCCACGATTTTTTATTCCACTCC | 60 | 150–160 | 4 | 1.68 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| hvcptrnS1 | (A)7CGC(T)13 | CTTTAGCGGGCATTTCCATAATGGTGGATTTGATAAGAACCC | 60 | 121–124 | 3 | 2.14 | 0.89 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| hvcptrnS2 | (T)10 | CAACTCCTTTGCGCTACACAACCCCTTTTTTCCCATTCC | 60 | 110–124 | 3 | 1.81 | 0.79 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| hvcptrnLF | (C)9 | GAGTATCGGCAAGAAATCTTGGTCAAAATTTGAAAGGGGGG | 60 | 150–151 | 2 | 1.90 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.48 |

| Mean | 3.50±0.56 | 2.16±0.22 | 0.92±0.11 | 0.52±0.04 | 0.53±0.04 |

Tm: primer melting temperature, Na: number of alleles per locus, Ne: number of effective alleles per locus, I: Shannon’s information index, h: genetic diversity, uh: unbiased diversity.

Data analysis

The number of alleles per locus (Na), the number of effective alleles per locus (Ne), Shannon’s information index (I), genetic diversity (h) and unbiased diversity (uh) were determined using the program GenAlEx 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse 2012). The detected haplotypes numbers (A), frequencies, distribution, the number of private haplotypes (P), the effective number of haplotypes (Ne), haplotypic richness (Rh), haplotypic diversity (Hd) and pair-wise Fst values were estimated using the Haplotype Analysis Software ver. 1.05 (Eliades and Eliades 2009). The analyses of molecular variation (AMOVA) and genetic differentiation (PhiPT) between the populations were determined using the program GenAlEx 6.5 (Peakall and Smouse 2012). A median-joining network of the detected haplotypes was constructed using Network 4.5.1.6 (Bandelt et al. 1999). A phylogenetic tree applying the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic average (UPGMA) was achieved based on the dissimilarities calculated from single data using the software DARwin v. 6.0.021 (Perrier and Jacquemoud-Collet 2006).

Results and discussion

Chloroplast SSRs transferability and polymorphism

All the tested cpSSRs led successfully to amplifications in all the analysed genotypes with a transferability rate of 100%. The tested chloroplast SSR molecular markers were shown to be polymorphic and exhibited size variation among the studied accessions. Genetic analyses achieved by pooling all the landraces into one group highlighted considerable molecular polymorphism for the studied cpSSR loci. Twenty-one alleles were generated by the studied loci with a mean value of 3.50 alleles per locus (Table 1). The number of alleles per locus (Na) varied from 2 (hvcptrnLF) to six (hvcprpoA) while the effective number of alleles (Ne) ranged from 1.68 (hvcprps12) to 3.21 (hvcprpoA). Shannon’s information indices (I) for the studied cpSSRs varied from 0.67 to 1.43. It is noted that the diversity indices (h) and uh ranged from 0.41 to 0.69 and from 0.41 to 0.70, respectively. The genetic diversity parameters calculated for the total pearl millet sample across all the loci were shown to be Na=3.50±0.56, Ne=2.16±0.22, I=0.92±0.11, h=0.52±0.04 and uh=0.53±0.04 (Table 1).

The transferability rate of the applied chloroplast microsatellites from barley to pearl millet genomes is in agreement with the high conservation level of angiosperm chloroplast genomes. Transferability across angiosperm species and genera was explained by the low molecular evolution rate of the microsatellites flanking regions which allows the high cross-species amplification of these molecular markers (Ginwal et al. 2011). These findings confirm that the choice of microsatellites molecular markers is advantageous in transferability testing across cereal taxa which generally reported to reveal high transferability efficiency (Singh et al. 2019). This molecular biotechnological approach offers the possibility of providing low-cost microsatellite markers for a species of interest. Cross-species transferability of microsatellite loci presents an alternative to the laborious and costly approaches of the development of novel SSR markers. The six tested informative cpSSR markers present useful molecular tools that could be further used for the characterisation of genetic diversity, molecular evolution, marker-assisted selection and genetic conservation of pearl millet and its related species.

Haplotype diversity and distribution

Due to the non-recombining nature of the chloroplast genome, a unique combination of size variants representing the alleles across the microsatellite loci was defined as a distinct haplotype. The twenty-one alleles identified at the six chloroplast microsatellites loci across the investigated sample combined into nine haplotypes (haplo-1, haplo-2, …….haplo-9) described for the first time in pearl millet genome. Haplotype frequencies across all the studied landraces varied from 0.02 (haplo-2) to 0.33 (haplo-5). A high haplotype genetic diversity (Hd=0.82) was recorded for the six cpSSR loci across the 49 studied landraces (Supplementary Table S2).

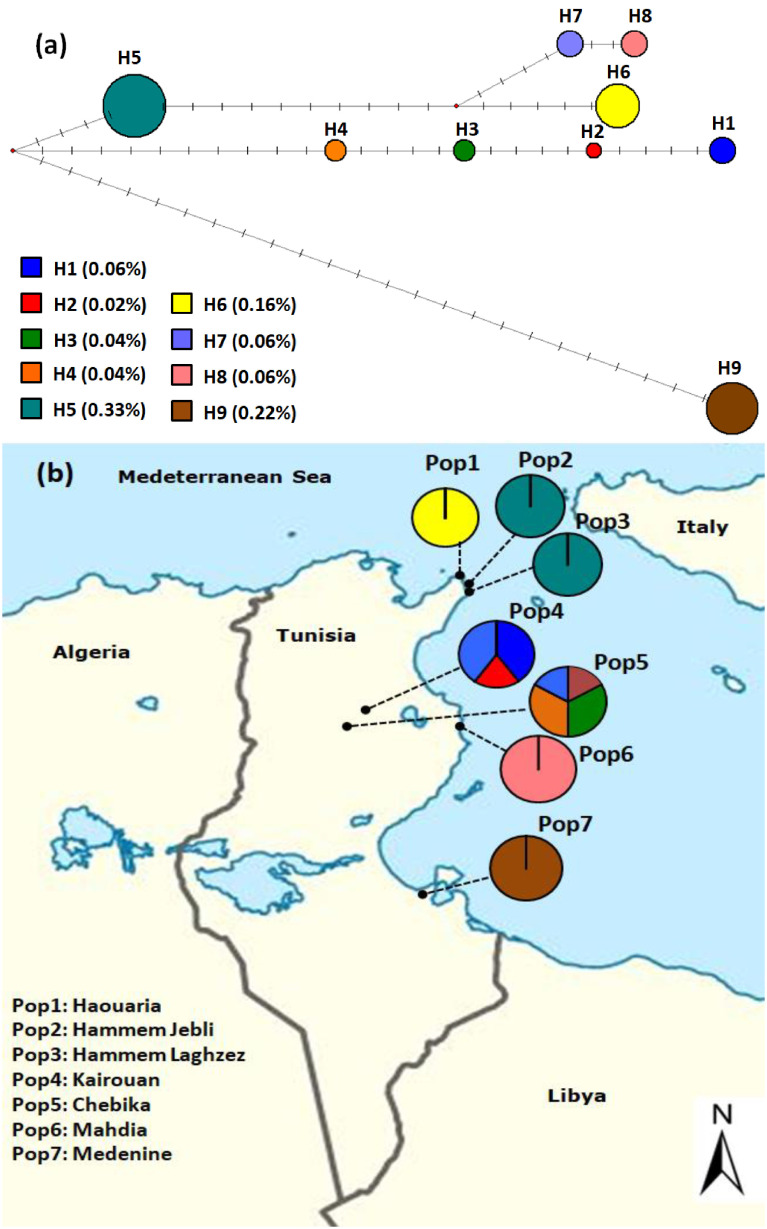

The number of chloroplast haplotypes per population ranged from 1 to 4 with a mean value of 1.28. The haplotype genetic diversity (Hd) for the studied populations ranged from 0 (Haouaria, Hammem Jebli, Hammem Laghzez, Mahdia and Medenine) to 0.87 (Chebika) with an average of 0.24 (Supplementary Table S2). Each one of the populations Haouaria, Mahdia and Medenine was characterized by one specific haplotype; haplo-6, haplo-8 and haplo-9, respectively. These population-specific haplotypes are considered potentially useful for the identification of provenances, seed-lots and autochthonous germplasms (Vendramin 2000). The populations of Hammem Jebli and Hammem Laghzez shared the haplo-5. Three haplotypes were recorded for the population of Kairouan (haplo-1: 0.40%, haplo-2: 0.20%, haplo-7: 0.40%) while the population of Chebika was characterised by four haplotypes (haplo-1: 0.17%, haplo-3: 0.33%, haplo-4: 0.33%, haplo-7: 0.17%). It is noted that Kairouan and Chebika populations shared the haplo-1 and haplo-7. The haplo-2 was shown to be specific to Kairouan landraces while haplo-3 and haplo-4 were found only in the population of Chebika. Notably, the observed results revealed the significant role of the local farmers in Haouaria, Kelibia and Medenine regions in preserving the identity of their pearl millet maternal lineages through the time.

To clarify the genetic relationships between the nine detected chloroplast haplotypes, a median-joining network was constructed (Figure 1). The chloroplast haplotypes classification outlined three main groups defined by their genetic relationships. Among the nine observed chloroplast haplotypes, H5 and H9 were the dominant ones. It is noted that the haplotypes 1–4, which presented close genetic relationships, are related to populations located in the same geographical area (Kairouan region). The position of the haplotype 5, which is the most frequent in the network and its relationships with the haplotypes 1–4, 6–8 suggest that it might be the ancestral chlorotype of this group. This first group may define the first maternal lineage of Tunisian pearl millet landraces. These haplotypes could have resulted from cumulative mutations in the studied loci. Interestingly, the haplotype 9 was revealed as a genetically distinct chlorotype. It could have resulted from the molecular evolution of a second maternal lineage of pearl millet which may have another introduction time in Tunisia.

Figure 1. (a) Median-joining network of the nine detected cpSSR haplotypes and their frequencies in the total studied landraces. Circle sizes are proportional to the haplotype frequencies. Transverse dashes represent 1-bp mutations between haplotypes. (b) Geographical distribution of the observed cpSSR haplotypes in Tunisia.

Genetic structure pattern and conservation implications

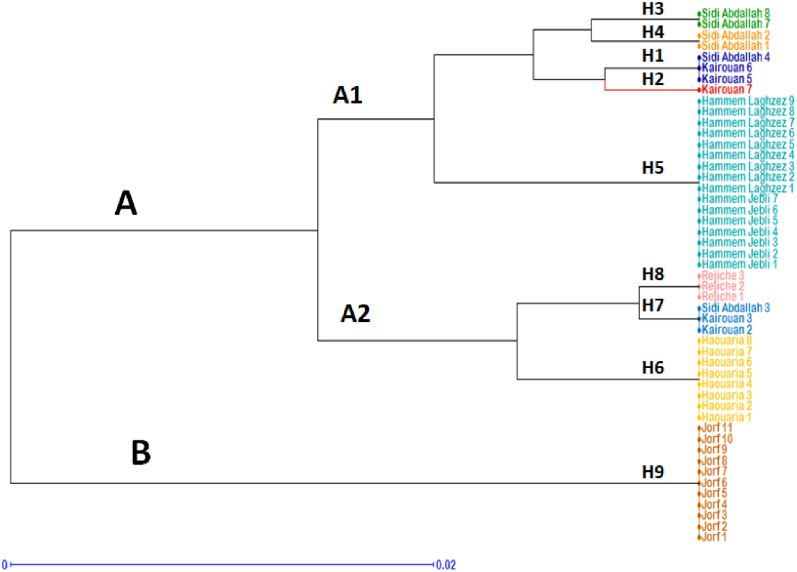

The investigated set of polymorphic chloroplast SSR markers were used to clarify the genetic relationships and population structure pattern of the seven studied populations. The clustering of the studied genotypes based on the UPGMA analysis highlighted an apparent genetic structure of the 49 studied landraces according to their geographical origin with considerable overlap between the North-East and the Centre-East landraces (Figure 2). Two clusters were revealed by this analysis. The first cluster (A), consisted of the North-East (Haouaria, Hammem Jebli and Hammem Laghzez) and the Centre-East (Kairouan, Chebika and Mahdia) landraces, was divided into two sub-clusters (A1 and A2). The sub-cluster A1 included Hammam Laghzez, Hammem Jebli and most of Kairouan and Chebika landraces. The landraces representing Haouaria and Mahdia populations along with Sidi Abdalla 3, Kairouan 2 and Kairouan 3 were classified in the sub-cluster A2. Interestingly, the second cluster B grouped all the South-East landraces representing the population of Medenine (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis applying the UPGMA method between the 49 pearl millet landraces based on chloroplast SSRs (H=Haplotype). The colours correspond to those shown in the Median-joining network.

Genetic structure analysis confirmed the median-joining network and highlighted the uniqueness of the South-East landraces represented by the haplotype 9. On the other hand, a higher genetic affinity was observed between the populations of the Cap-Bon and the Centre-East (Kairouan and Sahel regions) regions. The seed flow was considered as the major factor which defines the dynamics of pearl millet genetic diversity and has important implications in both genetic structure pattern and the evolution of this species (Naino Jika et al. 2017). The obtained results indicated the existence of a differential pearl millet seed-exchange rate between the investigated areas in Tunisia. The highest seed dispersal activities were observed between the Cap-Bon, Kairouan and the Sahel regions sharing a narrow geographical range. On the other hand, the chloroplast molecular data did not reveal a seed exchange between the North-Centre and the South areas of the country. Regional farmers’ practices in Medenine region in the South of Tunisia resulted in the isolation of their own local pearl millet landraces.

The geographical proximity between the Cap Bon and the Centre-East regions seems to be the main factor that could explain the detected genetic structure pattern and the considerable seed exchange between these areas. Moreover, pearl millet is considered as a secondary crop, with limited interest in Tunisia, and comes behind wheat and barley which occupy a prominent place in human diet and cropping lands. This marginalization of this multipurpose species has limited the seed selection interest and seed-exchange activities especially between the farmers belonging to distant geographical areas of Tunisia such as the Northern and Southern regions. Though the geographical area of Tunisia is limited, the country is characterised by five bioclimatic stages and exhibits contrasting bioclimatic and soil characteristics in the three main prospected areas. Notably, Southern pearl millet landraces have been cultivated for a long time in extremely severe arid conditions, in the least fertile soils and under unfavorable irrigation conditions. This resulted in the induction of differential adaptation potentials among the Southern and North-Centre germplasms of pearl millet in Tunisia.

Furthermore, the changes in consumer’s preferences and farmers cropping practices for pearl millet landraces between the North and the South of Tunisia may explain in a part the limited seed exchange rate between these areas. Pearl millet was cultivated in the North mainly for grain production while landraces with higher stover and tillers yields, used as fodder-complements and construction material of huts and parasols, are rather preferred by the farmers in the South of the country (Loumerem et al. 2008). In addition to the previously detailed bio-geographical factors, sociological and cultural data have been shown to define the seed-exchange practices and evolutionary dynamics of crop germplasms (Leclerc and Coppens d’Eeckenbrugge 2012).

The pattern of genetic structure and the spatial distribution of the detected haplotypes suggest at least two introduction origins for Tunisian pearl millet landraces. The first introduction event may have occurred in the North-East and the second in the South-East of the country. It seems that Centre-East landraces do not correspond to an independent introduction event of pearl millet but may mostly correspond to imported materials from the North-East region of Tunisia during various historical times. Notably, the production of this staple crop is mainly concentrated in the coastal regions which increases the probability that pearl millet was introduced in Tunisia through maritime trade. The hypothesis of both African and Asian origins was not excluded which goes well with Tunisian historical facts and geographical location. Tunisia has a long history and a rich tradition due to the settlement of many populations and civilizations (Zoghlami et al. 2009). The country is bordering the Mediterranean Sea from its Northern and Eastern sides and therefore had strategic connections with both West Africa and the Middle East.

To visualise the distribution of the detected genetic diversity among and within populations, the analysis of molecular variance AMOVA was performed. The results indicated that 82% of the total genetic diversity is among populations and only 18% is within populations (Table 2). This was confirmed by a highly significant level of genetic differentiation among these landrace populations (PhiPT=0.82, p value=0.001). A higher amount of genetic differentiation among-populations than within-populations is characteristic of maternally inherited DNA where the effective gene flow being limited to seed dispersal. It was reported that genetic drift is expected to be twice as strong for a haploid as for a diploid genome (Tang et al. 2014).

Table 2. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) between the seven pearl millet populations.

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % | PhiPT | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among populations | 6 | 124.57 | 20.76 | 2.93 | 82% | 0.82 | 0.001 |

| Within populations | 42 | 27.27 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 18% | ||

| Total | 48 | 151.84 | 3.58 | 100% |

Df: degrees of freedom, SS: sum of squares, MS: mean square, Est. Var.: estimated variance, PhiPT: genetic differentiation.

Understanding the genetic structure and differentiation pattern of cereal crops is essential for their efficient use and conservation (Ben Romdhane et al. 2017). The genetic resources of pearl millet in Tunisia are facing genetic erosion due to the marginalization of this species in favour of others major cereals (Ben Romdhane et al. 2018; Oumar et al. 2005). To date, there is a complete lack of any conservation measures for these valuable old-landraces neither in national nor in international gene banks. Furthermore, Tunisian local farmers are still cropping their own traditional landraces with the absence of varietal creation programs for these genetic resources in Tunisia.

The obtained results have important implications for the conservation and management of pearl millet gene pools in Tunisia. The detected genetic structure pattern characterised by a low intra-population genetic diversity with a high amount of genetic differentiation among the studied populations suggest that all the investigated populations exhibit high priority in further conservation strategies. Conservation programs should target the maximum amount of genetic polymorphism which will be useful in any further use and improvement strategies (Riahi et al. 2019). Thus, seeds from all the populations should be considered for ex-situ conservation in seed banks to preserve all the detected haplotypes and to maximize the genomic resources of the species. Especially, unique haplotypes should be included in the seed collection. Diversifying the cytoplasmic base is essential in conservation efforts. This requires the conservation of females representing all the detected cytoplasmic bases.

In addition to the ex-situ conservation of seeds in gene bank collections, which is a static conservation strategy that doesn’t allow the occurrence of a molecular evolution, complementary dynamic in-situ conservation measures are required. This allows maintaining a natural evolution rate to guarantee the local adaptation abilities of these germplasms in their respective domains of cultivation. In addition to the ex-situ and in-situ conservation strategies, the establishment of additional artificial populations by combining various pearl millet gene pools in diverse geo-bioclimatic experimental fields may be included in the conservation measures.

This study outlined the efficiency of the six applied cpSSR to characterize the genetic relationships among the studied pearl millet landraces and to give new insights into the maternal lineages of Tunisian germplasms. These findings corroborate results of Saito et al. (2017) who highlighted that a minimum set of six maternally inherited cpSSRs revealed an ability to elucidate the molecular polymorphism, genetic structure and gene flow pattern. The use of five cpSSR markers has been also shown useful in the analyses of genetic structure, phylogeography and to trace the origins of Prunus cultivars (Kato et al. 2018). Furthermore, the molecular polymorphism, classification and origin of Tunisian grapevines were undertaken based on three cpSSR (Riahi et al. 2011).

Conclusions

In this study, highly informative Hordeum-Pennisetum transferable chloroplast SSRs were applied to genotype seven populations of Tunisian pearl millet landraces considered under threat of genetic erosion. The obtained results highlighted a high cytoplasmic genetic diversity at the punctual and haplotypic levels and an untapped genetic potential of Tunisian germplasms of Pennisetum glaucum L. Two clusters were clearly distinguished for the seven studied populations based on the genetic structure analysis with a clear North-South genetic differentiation pattern. The Centre-East Tunisian pearl millet landraces exhibited common genetic background with the North-East samples, which reveals high historical seed exchange practices between these two pearl millet cropping areas. The obtained genetic evidences go well with the hypothesis of two introductions events; one in the North and the other in the South of the country. Both ex-situ and in-situ conservation measures should be considered for these remaining old landraces of Tunisian pearl millet which are threatened by genetic extinction. The used set of chloroplast molecular markers in pearl millet genome provides useful molecular tools in further genetic and genomic investigations into the genus Pennisetum.

Supplementary Data

References

- Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A (1999) Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 16: 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Romdhane M, Riahi L, Jardak R, Ghorbel A, Zoghlami N (2018) Fingerprinting and genetic purity assessment of F1 barley hybrids and their salt-tolerant parental lines using nSSR molecular markers. 3 Biotech 8: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Romdhane M, Riahi L, Selmi A, Jardak R, Bouajila A, Ghorbel A, Zoghlami N (2017) Low genetic differentiation and evidence of gene flow among barley landrace populations in Tunisia. Crop Sci 57: 1–9 [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Martins AM, Pessanha KLF, Pacheco S, Rodrigues JAS, Carvalho CWP (2018) Potential use of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) in Brazil: Food security, processing, health benefits and nutritional products. Food Res Int 109: 175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades NG, Eliades DG (2009) Haplotype Analysis: Software for Analysis of Haplotypes Data. Distributed by the Authors. Forest Genetics and Forest Tree Breeding, Georg-Augst University Goettingen, Germany

- Ginwal HS, Mittal N, Maurya SS, Barthwal S, Bhatt P (2011) Genomic DNA isolation and identification of chloroplast microsatellite markers in Asparagus racemosus Willd. through cross-amplification. Int J Biotechnol 10: 33–38 [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Matsumoto A, Mizusawa R, Tsuda Y, Tsumura Y, Yoshimaru H (2018) Development and characterization of chloroplast simple sequence repeat markers for Prunus taxa (eleven Japanese native taxa and two foreign taxa). Silvae Genet 67: 124–126 [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc C, Coppens d’Eeckenbrugge G (2012) Social organization of crop genetic diversity: The G×E×S interaction model. Diversity (Basel) 4: 1–32 [Google Scholar]

- Liu YC, Lin BY, Lin JY, Wu WL, Chang CC (2016) Evaluation of chloroplast DNA markers for intraspecific identification of Phalaenopsis equestris cultivars. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 203: 86–94 [Google Scholar]

- Loumerem M, Van Damme P, Reheul D, Behaeghe T (2008) Collection and evaluation of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) germplasm from the arid regions of Tunisia. Genet Resour Crop Evol 55: 1017–1028 [Google Scholar]

- Martel E, De Nay D, Siljak-Yakovlev S, Brown S, Sarr A (1997) Genome size variation and basic chromosome number in pearl millet and fourteen related Pennisetum species. J Hered 88: 139–143 [Google Scholar]

- Naino Jika AK, Dussert Y, Raimond C, Garine E, Luxereau A, Takvorian N, Djermakoye RS, Adam T, Robert T (2017) Unexpected pattern of pearl millet genetic diversity among ethno-linguistic groups in the Lake Chad Basin. Heredity 118: 491–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oumar I, Chibani F, Oran SA, Boussaid M, Karamanos Y, Raies A (2005) Allozyme variation among some pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) cultivars collected from Tunisia and West Africa. Genet Resour Crop Evol 52: 1087–1097 [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R, Smouse PE (2012) GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research: An update. Bioinformatics 28: 2537–2539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X, Jacquemoud-Collet JP (2006) DARwin Software. Dissimilarity Analysis and Represetaion for Windows, http://darwin.cirad.fr/

- Provan J, Russell JR, Booth A, Powell W (1999) Polymorphic chloroplast simple sequence repeat primers for systematic and population studies in the genus Hordeum. Mol Ecol 8: 505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riahi L, Chograni H, Masmoudi AS, Cherif A (2019) Genetic resources of Tunisian Artemisia arborescens L. (Asteraceae), pattern of volatile metabolites concentration and bioactivity and implication for conservation. Biochem Syst Ecol 87: 103952 [Google Scholar]

- Riahi L, Zoghlami N, Laucou V, Mliki A, This P (2011) Use of chloroplast microsatellite markers as a tool to elucidate polymorphism, classification and origin of Tunisian grapevines. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 130: 781–786 [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Tsuda Y, Uchiyama K, Fukuda T, Seto Y, Kim PG, Shen HL, Ide Y (2017) Genetic variation in Quercus acutissima Carruth, in traditional Japanese rural forests and agricultural landscapes, revealed by chloroplast microsatellite markers. Forests 8: 451 [Google Scholar]

- Sattler FT, Sanogo MD, Kassari IA, Angarawai II, Gwadi KW, Dodo H, Haussmann BIG (2018) Characterization of West and Central African accessions from a pearl millet reference collection for agromorphological traits and Striga resistance. Plant Genet Resour 16: 260–272 [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Kaila T, Chaduvula PK, Singh A, Singh NK, Gaikwad K (2019) Novel chloroplast microsatellite markers in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L. Millsp.) and their transferability to wild Cajanus species. Aust J Crop Sci 13: 185–191 [Google Scholar]

- Serba DD, Perumal R, Tesso TT, Min D (2017) Status of global pearl millet breeding programs and the way forward. Crop Sci 57: 2891–2905 [Google Scholar]

- Singh RB, Singh B, Singh RK (2019) Cross-taxon transferability of sugarcane expressed sequence tags derived microsatellite (EST-SSR) markers across the related cereal grasses. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol 28: 176–188 [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, Ye Q, Yao X (2014) Patterns of genetic variation in the Chinese endemic Psilopeganum sinense (Rutaceae) as revealed by nuclear microsatellites and chloroplast microsatellites. Biochem Syst Ecol 55: 190–197 [Google Scholar]

- Tomar RS, Deshmukh RK, Naik BK, Tomar SM (2014) Development of chloroplast-specific microsatellite markers for molecular characterization of alloplasmic lines and phylogenetic analysis in wheat. Plant Breed 133: 12–18 [Google Scholar]

- Vendramin GG, Anzidei M, Madaghiele A, Sperisen C, Bucci G (2000) Chloroplast microsatellite analysis reveals the presence of population subdivision in Norway spruce (Picea abies K.). Genome 43: 68–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Iaffaldano BJ, Zhuang X, Cardina J, Cornish K (2017) Chloroplast genome resources and molecular markers differentiate rubber dandelion species from weedy relatives. BMC Plant Biol 17: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghlami N, Bouagila A, Lamine M, Hajri H, Ghorbel A (2011) Population genetic structure analysis in endangered Hordeum vulgare landraces from Tunisia: Conservation strategies. Afr J Biotechnol 10: 10344–10351 [Google Scholar]

- Zoghlami N, Riahi L, Laucou V, Lacombe T, Mliki A, Ghorbel A, This P (2009) Origin and genetic diversity of Tunisian grapes as revealed by microsatellite markers. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 120: 479–486 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.